You are bidding on one BRAND NEW aluminum metal tin license plate .....

It is a brand new metal tin license plate that would be very much

enjoyed indeed by any car driver .

The license plate is unopened and still in the original shrink-wrap.

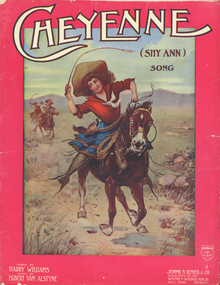

I image this plate on the car of a the BARBER SHOP / BIG BANG THEORY / Dr. Sheldon Cooper / X-Files / UFO / MUSTANG / Ford /

rodeo lover, or in the den of a Cowboy/ Cowgirl fan,

or better yet in your GARAGE.

It is a hoot. I was made here in the USA , and it measures

12 inches by 6 inches in size.

It has 4 holes for easy mounting.

I hope this finds a nice home. Thank you , Harry

Burma-Shave

Burma-Shave was an American brand of brushless shaving cream, famous for its advertising gimmick of posting humorous rhyming poems on small sequential highway roadside signs.

Contents

History

Burma-Shave was introduced in 1925 by the Burma-Vita company in Minneapolis owned by Clinton Odell. The company's original product was a liniment made of ingredients described as having come "from the Malay Peninsula and Burma" (hence its name).[1] Sales were sparse, and the company sought to expand sales by introducing a product with wider appeal.

The result was the Burma-Shave brand of brushless shaving cream and its supporting advertising program. Sales increased. At its peak, Burma-Shave was the second-highest-selling brushless shaving cream in the US. Sales declined in the 1950s, and in 1963 the company was sold to Philip Morris. The signs were removed at that time. The brand decreased in visibility and eventually became the property of the American Safety Razor Company.

In 1997, the American Safety Razor Company reintroduced the Burma-Shave brand with a nostalgic shaving soap and brush kit, though the original Burma-Shave was a brushless shaving cream, and Burma-Shave's own roadside signs frequently ridiculed "Grandpa's old-fashioned shaving brush."

Roadside billboards

Burma-Shave sign series first appeared on U.S. Highway 65 near Lakeville, Minnesota, in 1926, and remained a major advertising component until 1963 in most of the contiguous United States. The first series read: Cheer up, face - the war is over! Burma-Shave.[2] The exceptions were Nevada (deemed to have insufficient road traffic), and Massachusetts (eliminated due to that state's high land rentals and roadside foliage). Typically, six consecutive small signs would be posted along the edge of highways, spaced for sequential reading by passing motorists. The last sign was almost always the name of the product. The signs were originally produced in two color combinations: red-and-white and orange-and-black, though the latter was eliminated after a few years. A special white-on-blue set of signs was developed for South Dakota, which restricted the color red on roadside signs to official warning notices.

This use of a series of small signs, each of which bore part of a commercial message, was a successful approach to highway advertising during the early years of highway travel, drawing the attention of passing motorists who were curious to learn the punchline. As the Interstate system expanded in the late 1950s and vehicle speeds increased, it became more difficult to attract motorists' attention with small signs. When the company was acquired by Philip Morris, the signs were discontinued on advice of counsel.[3]

Some of the signs featured safety messages about speeding instead of advertisements.

Examples of Burma-Shave advertisements are at The House on the Rock in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Re-creations of Burma-Shave sign sets also appear on Arizona State Highway 66, part of the original U.S. Route 66, between Ash Fork, Arizona, and Kingman, Arizona, (though they were not installed there by Burma-Shave during its original campaigns) and on Old U.S. Highway 30 near Ogden, Iowa. Other examples are displayed at The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, the Interstate 44 in Missouri rest area between Rolla and Springfield (which has old Route 66 building picnic structures), the Forney Transportation Museum in Denver, Colorado and the Virginia Museum of Transportation in Roanoke, Virginia.

Examples

The complete list of the 600 or so known sets of signs is listed in Sunday Drives and in the last part of The Verse by the Side of the Road.[4] The content of the earliest signs is lost, but it is believed that the first recorded signs, for 1927 and soon after, are close to the originals. The first ones were prosaic advertisements. Generally the signs were printed with all capital letters. The style shown below is for readability:

- Shave the modern way / No brush / No lather / No rub-in / Big tube 35 cents - Drug stores / Burma-Shave

As early as 1928, the writers were displaying a puckish sense of humor:

- Takes the "H" out of shave / Makes it save / Saves complexion / Saves time and money / No brush - no lather / Burma-Shave

In 1929, the prosaic ads began to be replaced by actual verses on four signs, with the fifth sign merely a filler for the sixth:

- Every shaver / Now can snore / Six more minutes / Than before / By using / Burma-Shave

- Your shaving brush / Has had its day / So why not / Shave the modern way / With / Burma-Shave

Previously there were only two to four sets of signs per year. 1930 saw major growth in the company, and 19 sets of signs were produced. The writers recycled a previous joke. They continued to ridicule the "old" style of shaving. And they began to appeal to the wives as well:

- Cheer up face / The war is past / The "H" is out / Of shave / At last / Burma-Shave

- Shaving brushes / You'll soon see 'em / On the shelf / In some / Museum / Burma-Shave

- Does your husband / Misbehave / Grunt and grumble / Rant and rave / Shoot the brute some / Burma-Shave

In 1931, the writers began to reveal a "cringe factor" side to their creativity, which would increase over time:

- No matter / How you slice it / It's still your face / Be humane / Use / Burma-Shave

In 1932, the company recognized the popularity of the signs with a self-referencing gimmick:

- Free / Illustrated / Jingle book / In every / Package / Burma-Shave

- A shave / That's real / No cuts to heal / A soothing / Velvet after-feel / Burma-Shave

In 1935, the first known appearance of a road safety message appeared, combined with a punning sales pitch:

- Train approaching / Whistle squealing / Stop / Avoid that run-down feeling / Burma-Shave

- Keep well / To the right / Of the oncoming car / Get your close shaves / From the half pound jar / Burma-Shave

Safety messages began to increase in 1939, as these examples show. (The first of the four is a parody of "Paul Revere's Ride" by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.)

- Hardly a driver / Is now alive / Who passed / On hills / At 75 / Burma-Shave

- Past / Schoolhouses / Take it slow / Let the little / Shavers grow / Burma-Shave

- If you dislike / Big traffic fines / Slow down / Till you / Can read these signs / Burma-Shave

- Don't take / a curve / at 60 per. / We hate to lose / a customer / Burma-Shave[5]

In 1939 and subsequent years, demise of the signs was foreshadowed, as busy roadways approaching larger cities featured shortened versions of the slogans on one, two, or three signs — the exact count is not recorded. The puns include a play on the Maxwell House Coffee slogan, standard puns, and yet another reference to the "H" joke:

- Good to the last strop

- Covers a multitude of chins

- Takes the "H" out of shaving

The war years found the company recycling a lot of their old signs, with new ones mostly focusing on World War II propaganda:

- Let's make Hitler / And Hirohito / Feel as bad / as Old Benito / Buy War Bonds / Burma-Shave

- Slap / The Jap / With / Iron / Scrap / Burma-Shave

1963 was the last year for the signs, most of which were repeats, including the final slogan, which had first appeared in 1953:

- Our fortune / Is your / Shaven face / It's our best / Advertising space / Burma-Shave

Possibly the ultimate in self-referencing signs, leaving out the product name. This one also adorns the cover of the book:

- If you / Don't know / Whose signs / These are / You can't have / Driven very far

| The Big Bang Theory | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Sitcom[1] |

| Created by | Chuck Lorre Bill Prady |

| Directed by | Mark Cendrowski |

| Starring | |

| Theme music composer | Barenaked Ladies |

| Opening theme | "Big Bang Theory Theme"[3][4] |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Originallanguage(s) | English |

| No. of seasons | 8 |

| No. of episodes | 183 (list of episodes) |

The Big Bang Theory is an American sitcom created by Chuck Lorre and Bill Prady, both of whom serve as executive producers on the show along with Steven Molaro. All three also serve as head writers. The show premiered on CBS on September 24, 2007.[5] The eighth season premiered on September 22, 2014.

The show is primarily centered on five characters living in Pasadena, California: Leonard Hofstadter and Sheldon Cooper, both physicists at Caltech, who share an apartment; Penny, a waitress and aspiring actress who later becomes a pharmaceutical representative, and who lives across the hall; and Leonard and Sheldon's equally geeky and socially awkward friends and co-workers, aerospace engineer Howard Wolowitz andastrophysicist Raj Koothrappali. Geekiness and intellect of the four guys is contrasted for comic effect with Penny's social skills and common sense.[6][7]

Over time, supporting characters have been promoted to starring roles: Bernadette Rostenkowski, Howard's girlfriend (later his wife), a microbiologist and former part-time waitress alongside Penny; neuroscientist Amy Farrah Fowler, who joins the group after being matched to Sheldon on a dating website (and later becomes Sheldon's girlfriend); and Stuart Bloom, the cash-strapped owner of the comic book store the characters often visit, who, in season 8, moves in with Howard's mother.

Sheldon is often described as the stereotypical "geek". He is usually characterized as extremely intelligent, socially inept, and rigidly logical. Despite his intellect, he sometimes displays a lack of common sense. He has a superiority complex, but also possesses childlike qualities, of which he seems unaware, such as extreme stubbornness. He is unknowingly nasty to the others, even his friends, not by choice. It is claimed by Bernadette that the reason Sheldon is sometimes nasty is because the part of his brain that tells him it is wrong to be nasty is "getting a wedgie off of the other parts of his brain". The first four episodes of The Big Bang Theoryportray Sheldon inconsistently with his later characterization. According to Prady, the character "began to evolve after episode five or so and became his own thing."[17]

Sheldon possesses an eidetic memory and an IQ of 187,[18] although he claims his IQ cannot be accurately measured by normal tests.[19] He originally claimed to have a master's degree and two doctoral degrees, but this list has increased.[20][21] Sheldon has an extensive general knowledge in many subjects including physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy, cosmology, algebra, calculus, differential equations, vector calculus, computers, electronics, engineering, history, geography, linguistics, football and various languages like Finnish, Spanish, French, Mandarin Chinese, Persian, Arabic, and Klingon from Star Trek.[22] He also shows great talent in music, knowing how to play the piano, recorderand theremin and having perfect pitch.[23] Although his friends have similar intellects to him, his eccentricities, stubbornness, and lack of empathy often frustrate them. Sheldon occasionally uses slang (in a very unnatural fashion), and follows jokes with hiscatchphrase "Bazinga!" which is now an officially registered trademark of Warner Bros.[24][25] He is uncomfortable with human physical contact and has germophobia, which makes his exceptionally rare hugs extremely awkward and painful-looking. He also has blood phobia, which causes him to faint at the sight of it.[26] Sheldon has difficulty coping when he is interrupted, when asked to keep a secret, or when he hears arguing.[27][28][29] He is also a notary public and uses his knowledge in law and contracts usually for his own advantage and is always distressed when challenged in a legal aspect that he cannot logically defend. In his mannerisms, Sheldon also shows symptoms associated with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Whenever approaching a person's home, he must knock three times, then say the person's name, and must repeat this at least three times. Upon entering a person's home, he must select the proper seat before sitting down. When it is suggested by Penny that he "Just sit anywhere", his response is "Oh, no, that's crazy!" This extends to his inability to accept change. His rigidity in maintaining homeostasis often causes him frustration. Because of his rigidity and stubbornness, only his mother and Bernadette – both possessing strong maternal instincts – are able to control him.

Like his friends, Sheldon is scientifically inclined and is fond of comic books (especially the DC Universe), costumes, roleplaying games, video games, tabletop games, collectible card games, action figures, fantasy, science fiction, and cartoons. Sheldon hasrestraining orders from his heroes Leonard Nimoy, Carl Sagan, and Stan Lee,[30][31][32] as well as television scientist Bill Nye.[33] Sheldon often wears vintage T-shirts adorned with superhero logos.

| Ford Mustang | |

|---|---|

2015 Ford Mustang | |

| |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Ford |

| Production | April 1964–present |

| Model years | 1965–present |

| Designer | John Najjar Ferzely, Philip T. Clark, Joe Oros |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Pony car |

| Body style |

|

| Layout | FR layout |

The Ford Mustang is an American automobile manufactured by the Ford Motor Company. It was originally based on the platform of the second generation North American Ford Falcon, a compact car.[1] The original Ford Mustang I four-seater concept car had evolved into the 1963 Mustang II two-seater prototype, which Ford used to pretest how the public would take interest in the first production Mustang which was released as the 1964 1/2, with a slight variation on the frontend and a top that was 2.7 inches shorter than the 1963 Mustang II.[2] Introduced early on April 17, 1964,[3] and thus dubbed as a "1964½" model by Mustang fans, the 1965 Mustang was the automaker's most successful launch since the Model A.[4] The Mustang has undergone several transformations to its current sixth generation.

The Mustang created the "pony car" class of American automobiles—sports-car like coupes with long hoods and short rear decks[5]—and gave rise to competitors such as the Chevrolet Camaro,[6] Pontiac Firebird, AMC Javelin,[7] Chrysler's revamped Plymouth Barracuda and the first generation Dodge Challenger.[8] The Mustang is also credited for inspiring the designs of coupés such as the Toyota Celica and Ford Capri, which were imported to the United States.

Racing[edit]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2008) |

The Mustang made its first public appearance on a racetrack little more than a month after its April 17 introduction, as pace car for the 1964 Indianapolis 500.[13]

The same year, Mustangs achieved the first of many notable competition successes, winning first and second in class in the Tour de France international rally. The car's American competition debut, also in 1964, was in drag racing, where private individuals and dealer-sponsored teams campaigned Mustangs powered by 427 cu. in. V8s.

In late 1964, Ford contracted Holman & Moody to prepare ten 427-powered Mustangs to contest the National Hot Rod Association's (NHRA) A/Factory Experimental class in the 1965 drag racing season. Five of these special Mustangs made their competition debut at the 1965 NHRA Winternationals, where they qualified in the Factory Stock Eliminator class. The car driven by Bill Lawton won the class.[68]

A decade later Bob Glidden won the Mustang's first NHRA Pro Stock title.

Early Mustangs also proved successful in road racing. The GT 350 R, the race version of the Shelby GT 350, won five of the Sports Car Club of America's (SCCA) six divisions in 1965. Drivers were Jerry Titus, Bob Johnson and Mark Donohue, and Titus won the (SCCA) B-Production national championship. GT 350s won the B-Production title again in 1966 and 1967. They also won the 1966 manufacturers’ championship in the inaugural SCCA Trans-Am series, and repeated the win the following year.[13]

In 1969, modified versions of the 428 Mach 1, Boss 429 and Boss 302 took 295 United States Auto Club-certified records at Bonneville Salt Flats. The outing included a 24-hour run on a 10-mile (16 km) course at an average speed of 157 mph (253 km/h). Drivers were Mickey Thompson, Danny Ongais, Ray Brock, and Bob Ottum.[13]

In 1970, Mustang won the SCCA series manufacturers’ championship again, with Parnelli Jones and George Follmer driving for car owner/builder Bud Moore and crew chief Lanky Foushee. Jones won the "unofficial" drivers’ title.

Two years later Dick Trickle won 67 short-track oval feature races, a national record for wins in a single season.

In 1975 Ron Smaldone's Mustang became the first-ever American car to win the Showroom Stock national championship in SCCA road racing.

Mustangs also competed in the IMSA GTO class, with wins in 1984 and 1985. In 1985 John Jones also won the 1985 GTO drivers’ championship; Wally Dallenbach Jr., John Jones and Doc Bundy won the GTO class at the Daytona 24 Hours; and Ford won its first manufacturers’ championship in road racing since 1970. Three class wins went to Lynn St. James, the first woman to win in the series.

1986 brought eight more GTO wins and another manufacturers’ title. Scott Pruett won the drivers’ championship. The GT Endurance Championship also went to Ford.

In drag racing Rickie Smith's Motorcraft Mustang won the International Hot Rod Association Pro Stock world championship.

In 1987 Saleen Autosport Mustangs driven by Steve Saleen and Rick Titus won the SCCA Escort Endurance SSGT championship, and in International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) racing a Mustang again won the GTO class in the Daytona 24 Hours. In 1989, its silver anniversary year, the Mustang won Ford its first Trans-Am manufacturers’ title since 1970, with Dorsey Schroeder winning the drivers’ championship.[69]

In 1997, Tommy Kendall’s Roush-prepared Mustang won a record 11 consecutive races in Trans-Am to secure his third straight driver's championship.

In 2002 John Force broke his own NHRA drag racing record by winning his 12th national championship in his Ford Mustang Funny Car, Force beat that record again in 2006, becoming the first-ever 14-time champion, again, driving a Mustang.[13]

Currently, Mustangs compete in the Continental Tire Sports Car Challenge (formerly known as the KONI Challenge), where they have won the manufacturer's title in 2005 and 2008, and the Canada Drift, Formula Drift and D1 Grand Prix series. They are highly competitive in the SCCA World Challenge, with Brandon Davis winning the 2009 GT driver's championship. Mustangs competed in the now-defunct Grand-Am Road Racing Ford Racing Mustang Challenge for the Miller Cup series as well.

Ford has been successful in the Grand-Am Road Racing Continental Tire Sports Car Challenge winning championships in 2005, 2008, and 2009 with the Mustang FR500C and GT models. In 2004, Ford Racing retained Multimatic to design, engineer, build and race the Mustang FR500C turn-key race car. Multimatic Motorsports won the championship in 2005 with Scott Maxwell and David Empringham taking the driver's title. In 2010, Ford Racing contracted Multimatic again to design, engineer, develop and race the next generation of Mustang race car, known as the Boss 302R. With any new race car, it had various kinks and bugs to work through. The new Mustang Boss 302R achieved numerous pole positions, however reliability hampered race results. The following season the Mustang Boss 302R took its maiden victory at Barber Motorsports Park in early 2011. Multimatic Motorsports drivers Scott Maxwell and Joe Foster brought home the win for Ford.

In 2010 the Ford Mustang became Ford's Car of Tomorrow for the NASCAR Nationwide Series with full-time racing of the Mustang beginning in 2011. This opened a new chapter in both the Mustang's history and Ford's history. NASCAR insiders expect to see Mustang racing in NASCAR Sprint Cup by 2014 (the model's 50th anniversary). Unlike other racing series, the NASCAR vehicles are not based on production Mustangs, but are a silhouette racing car with decals that give them a superficial resemblance to the production road cars. Carl Edwards won the first-ever race with a NASCAR-prepped Mustang on April 8, 2011 at the Texas Motor Speedway.

Ford Mustangs compete in the FIA GT3 European Championship, and compete in the GT4 European Cup and other sports car races such as the 24 Hours of Spa. The Marc VDS Racing Team has been developing the GT3 spec Mustang since 2010.[70] The car has most recently competed in the 2011 24 hours of Spa.

In 2012, Jack Roush won the Daytona International Speedway's opening race of the 50th Anniversary Rolex 24 At Daytona weekend in a Mustang Boss 302R. Leading the Continental Tire Sports Car Challenge's final 18 laps, Johnson held off a veritable conga line of six BMW M3's behind as he closed on the driving pair's first win of 2012 in the BMW Performance 200 at Daytona.[71]

Awards[edit]

The 1965 Mustang won the Tiffany Gold Medal for excellence in American design, the first automobile ever to do so.

The Mustang was on the Car and Driver Ten Best list in 1983, 1987, 1988, 2005, 2006, and 2011. It won the Motor Trend Car of the Year award in 1974 and 1994.

In 2005 it was runner-up to the Chrysler 300 for the North American Car of the Year award and was named Canadian Car of the Year.[72]

Cowgirl

| Look up cowgirl in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

A cowgirl is the female equivalent of a cowboy.

Cowgirl may also refer to:

In entertainment:

- "Cowgirl" (song), a 1994 single by Underworld

- "Legend of a Cowgirl", a 1997 single by Imani Coppola

- "Cowgirl", a 2001 song by Bambee from her album Fairytales

- Cowgirl (album), a 2006 album by Lynn Anderson

- Cowgirl (film), a German film starring Alexandra Maria Lara

- Cowgirl (short subject film), a short subject film featuring Sandra Oh

- Jillian "Cowgirl" Pearlman, a character in the Green Lantern comics featuring Hal Jordan

- Cowgirl, a character in the comic book mini-series Ultra

In sports:

- Oklahoma State Cowgirls, the women's athletic teams of Oklahoma State University–Stillwater

- Wyoming Cowgirls, the women's athletic teams of the University of Wyoming

In other uses:

- Cowgirl (sex position), another name for the "woman on top" position

- The Cowgirl, Jenn Sterger, model and television personality, known for a brief TV appearance in a cowboy hat and tight shirt while a student at Florida State University

- FSU Cowgirls, a group of FSU coeds of which Sterger was a member

- Cowgirl Creamery, an artisanal cheese company in California, US

Development of the modern cowboy image

The traditions of the working cowboy were further etched into the minds of the general public with the development of Wild West Shows in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which showcased and romanticized the life of both cowboys and Native Americans.[61] Beginning in the 1920s and continuing to the present day, Western movies popularized the cowboy lifestyle but also formed persistent stereotypes, both positive and negative. In some cases, the cowboy and the violent gunslinger are often associated with one another. On the other hand, some actors who portrayed cowboys promoted positive values, such as the "cowboy code" of Gene Autry, that encouraged honorable behavior, respect and patriotism.[62]

Likewise, cowboys in movies were often shown fighting with American Indians. However, the reality was that, while cowboys were armed against both predators and human thieves, and often used their guns to run off people of any race who attempted to steal, or rustle cattle, nearly all actual armed conflicts occurred between Indian people and cavalry units of the U.S. Army.[citation needed]

In reality, working ranch hands past and present had very little time for anything other than the constant, hard work involved in maintaining a ranch.

Cowgirls

The history of women in the west, and women who worked on cattle ranches in particular, is not as well documented as that of men. However, institutions such as the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame have made significant efforts in recent years to gather and document the contributions of women.[2]

There are few records mentioning girls or women working to drive cattle up the cattle trails of the Old West. However women did considerable ranch work, and in some cases (especially when the men went to war or on long cattle drives) ran them. There is little doubt that women, particularly the wives and daughters of men who owned small ranches and could not afford to hire large numbers of outside laborers, worked side by side with men and thus needed to ride horses and be able to perform related tasks. The largely undocumented contributions of women to the west were acknowledged in law; the western states led the United States in granting women the right to vote, beginning with Wyoming in 1869.[63] Early photographers such as Evelyn Cameron documented the life of working ranch women and cowgirls during the late 19th and early 20th century.

While impractical for everyday work, the sidesaddle was a tool that gave women the ability to ride horses in "respectable" public settings instead of being left on foot or confined tohorse-drawn vehicles. Following the Civil War, Charles Goodnight modified the traditional English sidesaddle, creating a western-styled design. The traditional charras of Mexicopreserve a similar tradition and ride sidesaddles today in charreada exhibitions on both sides of the border.

It wasn't until the advent of Wild West Shows that "cowgirls" came into their own. These adult women were skilled performers, demonstrating riding, expert marksmanship, and trick roping that entertained audiences around the world. Women such as Annie Oakley became household names. By 1900, skirts split for riding astride became popular, and allowed women to compete with the men without scandalizing Victorian Era audiences by wearing men's clothing or, worse yet, bloomers. In the movies that followed from the early 20th century on, cowgirls expanded their roles in the popular culture and movie designers developed attractive clothing suitable for riding Western saddles.

Independently of the entertainment industry, the growth of rodeo brought about the rodeo cowgirl. In the early Wild West shows and rodeos, women competed in all events, sometimes against other women, sometimes with the men. Cowgirls such as Fannie Sperry Steele rode the same "rough stock" and took the same risks as the men (and all while wearing a heavy split skirt that was more encumbering than men's trousers) and competed at major rodeos such as the Calgary Stampede and Cheyenne Frontier Days.[64]

Rodeo competition for women changed in the 1920s due to several factors. After 1925, when Eastern promoters started staging indoor rodeos in places like Madison Square Garden, women were generally excluded from the men's events and many of the women's events were dropped. Also, the public had difficulties with seeing women seriously injured or killed, and in particular, the death of Bonnie McCarroll at the 1929 Pendleton Round-Up led to the elimination of women's bronc riding from rodeo competition.[65]

In today's rodeos, men and women compete equally together only in the event of team roping, though technically women now could enter other open events. There also are all-women rodeos where women compete in bronc riding, bull riding and all other traditional rodeo events. However, in open rodeos, cowgirls primarily compete in the timed riding events such as barrel racing, and most professional rodeos do not offer as many women's events as men's events.

Boys and girls are more apt to compete against one another in all events in high-school rodeos as well as O-Mok-See competition, where even boys can be seen in traditionally "women's" events such as barrel racing. Outside of the rodeo world, women compete equally with men in nearly all other equestrian events, including the Olympics, and western riding events such as cutting, reining, and endurance riding.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cowgirls. |

Today's working cowgirls generally use clothing, tools and equipment indistinguishable from that of men, other than in color and design, usually preferring a flashier look in competition. Sidesaddles are only seen in exhibitions and a limited number of specialty horse show classes. A modern working cowgirl wears jeans, close-fitting shirts, boots, hat, and when needed, chaps and gloves. If working on the ranch, they perform the same chores as cowboys and dress to suit the situation.