WW2 JEWISH GHETTO CURRENCY FROM MISCOLCZ HUNGARY

Largest Jewish Community in Hungary before Nazi Deportations to Labor and Death Camps!

The vibrant Jewish Community of Miscolcz first began in the 1720's. Its fortunes ebbed and flowed with changing economic, government, social and racial policies and practices but it remained intact and largely prospered until the arrival of the Nazis.

In 1941, when there were 10,428 Jews in the town, 500 were deported to the German-occupied part of Poland for alleged irregularities in their nationality, and were murdered in Kamenets-Podolski. Large numbers of youths, as well as elderly people, were conscripted into labor battalions and taken to the Ukrainian front, where most of them were exterminated. After the German occupation of Hungary (March 19, 1944) due to Hungary's relatively lax persecution of Jews, the then remaining Jews of the town, about 10,000 in number, were deported to Auschwitz; only 400 of them survived.

Here you have an incredibly rare piece of currency in Hungarian Fillers issued by the Miskolczi Ortodox Izraelita Anyahitközség (The Miscolcz Orthodox Israelite Mother Community) during the very time of the referenced deportations and murders. Date may vary (guaranteed WW2!). Color may vary and design may vary slightly (see scan 2). Each piece is UNIQUE and DIFFERENT! Please email if you want multiples. The note is printed entirely in Hungarian on unique paper with a low serial number. It remains completely UNCIRCULATED without any tears, splits, holes, stains or grafitti.

An amazing piece of Judaica from the heart of Eastern Europe during the darkest period of the Holocaust. Retail Value $100 but truly priceless!! Buy Now for just $37.49. Shipping is $1.85. Insurance is $2.10.

Numerous articles, essays, photos and links follow below. Thanks for visiting Collect-a-thon, where history lives!

| Kazinczy Street Synagogue | |

|---|---|

| |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Miskolc, Hungary |

| District | Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Active Synagogue |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Ludwig Förster |

| Architectural style | Romanesque Revival |

| Completed | 1862 |

| Specifications | |

The Kazinczy Street Synagogue of Miskolc is the only surviving synagogue in the city of Miskolc, Hungary, and the only still functioning synagogue of Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén county.

The synagogue was designed by Ludwig Förster and built between 1856 and 1862 in neo-Romanesque style. Its Kazinczy Street facade has a rose window and narrow Gothic windows. The synagogue has three aisles. The women's balcony is supported by slim iron pillars decorated with Gothic Revival and Neo-Byzantine elements. The painting of the walls feature ornamental Eastern design.

When designing the synagogue, Förster made some innovations: he had an organ built and the Torah reader's platform was put before the Ark, not in the centre of the synagogue. These innovations were rejected by the Orthodox majority of the city's Jews, and in the year following the opening of the synagogue a rabbinical assembly in Sátoraljaújhely excommunicated the rabbi of Miskolc. The Jewish citizens of Miskolc decided to remove the organ from the synagogue and put the platform in the centre, in accord with tradition.

This event led to a split in the Jewish community, and the local Hasidim ("Sefardim") separated from the rest, building a small place of worship in Kölcsey street, which no longer survives.

Another synagogue built in 1817, in Pálóczy Street, was demolished in 1963.

According to the 1920 census, Miskolc had about 10,000 Jewish residents (16.5% of the total population) but the majority of them fell victim to The Holocaust. At the Déryné Street entrance to the synagogue are marble tablets commemorating that tragic event. Another commemorative plaque can be seen in János Arany Street, where the ghetto once was.

As of 2001, the city had about 500 Jewish residents.

MISKOLC

MISKOLC, town in N.E. Hungary. Jews attended the Miskolc fairs at the beginning of the 18th century, and the first Jewish settlers earned their livelihood from the sale of alcoholic beverages. In 1717 the municipal council sought to expel them but reconsidered its attitude in 1728 and granted them the right to sell at the market. The number of Jews gradually increased, supplanting the Greek merchants from Macedonia. In 1765 several Jews owned houses. They enjoyed judicial independence and were authorized to impose fines and corporal punishment. Early in the 19th century there were two rabbis in the community. Many Jews acquired houses and land, but the majority engaged in commerce and crafts. When the local guild excluded Jews from membership in the unions, the Jews organized their own guild. The cemetery, dating from 1759, was still in use in 1970. The first synagogue was erected in 1765. The Great Synagogue was built in 1861; it was here that a choir, which aroused violent reactions on the part of the Orthodox, appeared for the first time. In 1870 the community joined the Neologians (see *Neology), but in 1875 a single Orthodox community was formed.

The educational institutions were among the most developed and ramified throughout the country. There were three yeshivot, an elementary school, two sub-secondary schools, and the only seminary for female teachers in Hungary. The Ḥasidim established a separate elementary school. In the course of time the percentage of Jews of the general population became the highest in Hungary (around 20%), numbering 1,096 in 1840, 3,412 in 1857; 4,117 in 1880, 10,029 in 1910, and 11,300 in 1920.

Holocaust Period and After

In 1941, when there were 10,428 Jews in the town, 500 were deported to the German-occupied part of Poland for alleged irregularities in their nationality, and were murdered in *Kamenets-Podolski. Large numbers of youths, as well as elderly people, were conscripted into labor battalions and taken to the Ukrainian front, where most of them were exterminated. After the German occupation of Hungary (March 19, 1944) the Jews of the town, about 10,000 in number, were deported to *Auschwitz; only 400 of them survived.

After the liberation Miskolc became an important transit center for those who returned from the concentration camps. The elementary school was reopened and existed until the nationalization of elementary schools (1948). The reconstituted community had 2,353 members in 1946 but dropped to around 300 in the 1970s as most left for Israel.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

B. Halmay and A. Leszik, Miskolc (1929); Miskolci zsidó élet, 1 (1948); Uj Élet, 23 no. 7 (1968), 4; 24, no. 20 (1969), 1; E. László, in: R.L. Braham (ed.), Hungarian Jewish Studies, 2 (1969), 137–82.

[Laszlo Harsanyi]

Miskolc

Seat of Borsod county, Hungary. Founded by a steady stream of immigrants from Moravia from the 1720s on, the Jewish community of Miskolc grew slowly during the eighteenth century. Until the 1820s, its only functioning communal institutions were the burial society, founded in 1767, and a seven-man executive committee appointed in 1769 to collect the Toleration Tax on behalf of the royal crown. The community had no rabbi until the 1770s, and, until 1784, only a single school, which had been founded in 1734. A Josephinian Normalschule, established in 1784 and highly praised by Ferenc Kazinczy, superintendant of schools for the Habsburg government and a leading figure in the Magyar national revival, functioned for just three years.

The growing influence of nobles in Miskolc eliminated all restrictions on Jewish settlement by 1820. The Jewish population increased to 389 by 1828; to 1,096 by 1837; and to 2,937 by 1848. From 1848 to 1920 Jews constituted about 20 percent of the city’s total population. By 1869, there were 4,770 Jews in the town, and numbers rose to 5,117 by 1880; to 8,551 by 1900; and to 10,291 by 1910. The Jewish population remained at approximately 10,000 until 1944.

According to the census of 1848, the three most common occupations for Jews were in commerce, tavernkeeping, and artisanry. Jewish artisans first organized in 1813 and were recognized as an official guild by the royal crown and the county diet in 1836. Jews were among the city’s leading commercial and industrial entrepreneurs. Joseph Lichtenstein, for example, was a cofounder in 1845 of the first credit bank in Miskolc.

The first synagogue, built in 1786, was restored after being damaged in a fire in 1843. In 1861, construction began on a new, larger synagogue on Kazinczy Street, which was completed in 1863 and was followed by the Paloczy Street synagogue in 1901. By 1880, Miskolc had three yeshivas and three Talmud Torah schools. In 1895, some 800 Jewish students studied at these schools, and an additional 800 were enrolled in vocational programs.

Although religiously traditional, Miskolc Jews introduced certain innovations associated with Reform Judaism as early as the 1830s (notably, they allowed weddings to be performed in the synagogue as opposed to the traditional custom of outdoor ceremonies). The completion of the Kazinczy Street synagogue in 1863 precipitated a conflict between Ezekiel Mozes Fischman, chief rabbi of Miskolc, and Hillel Lichtenstein, the ultra-Orthodox rabbi of Szikszó. At the end of the 1860s, the community wavered over whether to affiliate as Orthodox or Neolog. After the leadership chose to affiliate with Orthodoxy in 1869, the members of the Kazinczy synagogue became Neolog in 1870. In 1875, the two communities were reunited as a single Orthodox community. A decade later, a small contingent organized a Status Quo congregation, and Hasidic Jews organized a separate congregation after rejecting innovations with respect to marriage ceremonies. The Miskolc rabbinate was consistently moderate in its traditional outlook. Fischman (1836–1875), Moritz Rosenfeld (1878–1908), and Salomon Spira (or Shapira; 1898–1944) brokered compromises between traditional and progressive positions.

Noted individuals from Miskolc included Pinḥas Heilprin, a maskil who immigrated from Galicia in 1843 and was among the most outspoken critics of Samuel Holdheim’s radical reform; his son Mihály Heilprin, who composed Hungarian poetry in 1848 and was active in the revolutions of 1848–1849; Abraham Hochmuth, whose statewide program of education reform during the 1850s was based on changes he had introduced in Miskolc during the 1840s; Mihaly Popper, a leading voice of moderation and compromise at the General Jewish Congress of Hungary of 1868–1869; Samuel Austerlitz, one of the first Hungarian rabbis to become an ardent Zionist; and Lajos Hatvany-Deutsch, who often alluded to Miskolc in his semiautobiographical novels.

Miskolc Jewry was known for its communal institutions and organizations. The Jewish Artisans Guild, founded in 1836, later became the Miskolc Israelite Artisans Association. Emperor Franz Joseph personally acknowledged the Jewish Women’s Association, founded in 1847, during his visit to Miskolc in 1880. The Teachers Training Institute, founded in 1846, and Erzsébet Gymnasium for girls, founded in 1901, were among the leading educational institutions of their kind in Central Europe.

During the interwar period, Jews in Miskolc faced rising antisemitism, spearheaded by Lörincz Sim, a local police officer. A period of economic decline began in 1923, but Jews remained prominent in commerce, medicine, and law. The numerus clausus of 1919 temporarily reduced the number of Jewish students in the local public schools. In 1925, there were 2,571 Jewish students in Miskolc schools, but by 1944 the number had fallen to 1,588. The protection of the Hungarian minister of education partially rectified the situation. The number of Jewish students in local gymnasia then increased from a low of 23 in 1923 to 283 by 1939. After 1928, the Teachers Training Institute taught Hebrew as a recognized language.

On 20 June 1942, all men age 60 and under were taken into forced labor, mostly at the Hatvan labor camp. Jewish war veterans, some of whom displayed national colors, became officers in the camp. The postwar Jewish population of Miskolc has never exceeded 400.

Suggested Reading

István Dobrossy, ed., Miskolc Története, vol. 3 (Miskolc, 1998–2003); Nathaniel Katzburg, Pinkas ha-Kehilot: Hungaryah (Jerusalem, 1976), pp. 359–365; Aron Moskovits, Jewish Education in Hungary, 1848–1948 (New York, 1964), pp. 4, 79, 235–238, 288; Shlomo Paszternák, Miskolc és környéke mártirkönyv (Bene Berak, 1970); Péter Ujvári, ed., Magyar Zsidó Lexikon (1929; rpt. Budapest, 2000), pp. 606–608.

Author

Translated by András Hirschler

Edited by Yocheved Klausner

Caption 1: Miskolc memorial columnCaption 2: Memorial plaque at Mount Zion, Jerusalem

Caption 3: Translation of the Hungarian inscription on the memorial column: My eyes run down with streams of water because of the destruction of my people. (Jeremiah, 8, 23)

Caption 4: Translation of the Hungarian inscription on the memorial column: This column is to commemorate the fourteen thousand martyrs, our Jewish brothers and sisters deported from Miskolc, killed by brutal anti-Semitism, with gas, fire, bullets, starvation in Auschwitz and in the other death camps, or that perished while performing forced labour or being marched along the roads of Europe.

It is widely believed that the formula of any single drop of seawater is identical to that of all the other seas of the world. This statement seems to apply generally to the history of each Hungarian Jewish community.

In Hungary, or, as it later became known, in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, Jews were not allowed to settle in towns for prolonged periods. There were only a few exceptions, such as Buda, Székesfehérvár, Pozsony, and Kismarton. Miskolc, as a town of the Crown, was also among the municipalities that forbade Jews from taking up residence in the town. In fact, Jews could settle only in those villages where local landlords gave them permission to do so. According to historical records, the following locations were accessible for Jews around Miskolc from the late 18th century:

| Abaúj-Torna county: | Szikszó –Perényi and Csáky estates Méra – Fáy and Vitéz estates Gönc – Csáky estate Szántó – Bettenheim estate |

| Borsod county: | Csaba – Episcopate estate Szentpéter – Szirmay estate Kazinc – Radványi estate Emőd – Erdődy estate |

| Zemplén county | Szerencs, Zombor, Monok – Andrássy estate Tállya, Sárospatak – Bettenheim estate Mád, Bodrogkeresztúr – Erdődy estates Tolcsva – Szirmay estate |

Most of the Jews who settled in these villages were tradesmen selling their own products and goods made by others at houses and markets.

Miskolc, situated at the border of the Great Plain of Hungary, is a major agricultural production area, and the mountains in Northern Hungary, a mining and industrial centre, was a market town from the earliest times. This bustling trading environment was doubtless an important attraction for Jews considering settling around Miskolc.

The Jews who lived in these villages did not form independent religious communities. Their various legal and administrative matters were handled by the offices of “communitas judaeorum” (originally the Latin name of a Jewish community occupying a separate street, later the collective designation of the rights and obligations the local landlord agreed with Jews living on his estates). In many cases even religious and cultural matters were discussed and settled at these forums. Their main task, however, was to handle issues related to the “tolerance tax”[1] and residence permits. With social modernisation and the general development of state administration, communitas judaeorum offices became obsolete and were gradually replaced by Jewish Faith Communities. Such communities were formed in Csaba (a village belonging to the Munkács Episcopate) and Diósgyőr. Aristocrats from nearby settlements may have given permission to their Jewish business partners and acquaintances to live in their properties in Miskolc. In the house of Pál Szepessy[2] a small pub serving pálinka (strong fruit brandy) opened as early as 1717. From this time on, Jews attending the weekly market in Miskolc could spend the nights before and after market day not only in guesthouses in Csaba or Diósgyőr, but also in this building. Their situation, however, did not improve at all, as is clearly shown in a petition made by the Minorite provost to the municipality in 1725. In this, the Minorites demand that the space in front of the Convent's building (the area in which the weekly markets were held – later the venue of the Catholic grammar school) should be banned for Jews because “it is intolerable that this area is desecrated by Jews”. There were several other attempts to expel Jews from Miskolc, these, however, failed as the stewardship of the Royal estate in Diósgyőr had successfully applied for protection at the Hofkammer, the organ of Hapsburg financial administration.

In 1735, Jewish lessees of taverns and shops formed a corporation, a guild-like body, to represent their common interest. In 1759, a Jewish cemetery, and in 1765 a pray-house opened. Soon a local rabbi was appointed who served simultaneously the entire community of the county. In those times the president and the vice-president were appointed by the council presiding at the assembly. The corporation, enjoying the protection of the Hofkammer, was entitled to exercise certain rights: it could impose taxes and fines, and even use corporal punishment. Jews wishing to settle down in Miskolc also needed the consent of the corporation.

During the reign of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor and the ruler of Hapsburg lands from 1780 to 1790 who introduced a liberal attitude towards the Jews, the Jewish community increased considerably in numbers. Unfortunately, this liberal-minded and generous ruler could not resist the intrigues of his court cliques and, thus, most of his religious reforms were abrogated before his death in 1790. Anti-Jewish sentiments were wide-spread over the whole country. As a consequence, most of the Jews of Miskolc also had to leave the town. Temporarily, they found refuge in the neighbouring villages of Zsolca, Csaba and Diósgyőr. In a couple of years, however, restrictive rules became less stringent and Miskolc's Jewish population started to grow again.

Many Greek people, emigrating from Macedonia (then under Turkish rule) in the 17th century, settled down in Miskolc and its neighbourhood. These people were very clever traders and craftsmen and their community was strongly represented in the town council. For financial reasons they were fiercely against the Jews being allowed to settle down and gaining ground in Miskolc. A part of the Greek community returned to Macedonia, but many remained in the region, giving up trading, planting vine, building cellars and going into the business of professional wine making. Their wealth is clearly demonstrated by the rich interior ornamentation of the Greek Orthodox Church in Miskolc. Greek traders and craftsmen were replaced by Jews who soon developed Miskolc into North Hungary's industrial and commercial centre.

The number of Jews further increased. For tax assessment the Municipality ordered a conscription of all Jews living in the area in 1814. In 1835, “215 Jewish persons” were counted, who were obliged to pay 700 forint each as tolerance tax. Twelve years later, in 1847, there were already 361 persons conscripted each paying 1900 forint.

In 1848[3] and the following years of retribution – as in several other times during our history – Jews were made the scapegoats for all the troubles. The situation of Jews again became very difficult throughout the country – and Miskolc was no exception. The Council of Israelites was ordered “to stop immediately the corrupt practice of hiding Jews arriving from alien places with local Jews”. A precise Yiddish translation of the order can be found in the Minutes of the Council. Once the order had been given, the number of Jews visiting Miskolc decreased drastically. It is most likely that Jews attending the weekly markets and fairs in Miskolc stayed the night in Zsolca or Csaba, so that they did not fall under the duty of registration with the local authority.

As mentioned earlier, Jews in Miskolc were engaged not only in trade, but increasingly in industry. Guilds, however, did not accept manufacturers professing the Jewish faith as members. Therefore, Jewish manufacturers established their own trade association in 1833. As the guilds were strongly against the association, a Jewish guild of manufacturers was established three years later. However, all efforts failed to have its statutes approved. In 1848, Hungarian Jews supported the Revolution enthusiastically. In Miskolc, many Jews enlisted voluntarily to the National Guard, and several companies supplied the guard with uniforms, shoes, caps, etc. Perhaps as a reward, the statute of the manufacturers' guild was approved at last. Manufacturers were incorporated in the following subsections: cap makers, furriers, tanners, haberdashers, tinsmiths, tailors, boot makers and upholsterers. When the guild system was abolished, the Jewish guild was transformed into a Jewish Industrial Society. As a result, industrialists and industrial associations played an increasingly important role in the social life of the Miskolc Jewry. On the occasion of the society's 75th anniversary (by which time a bakeries section had also been formed), an alms-house was opened in the society building (Urak utcája 25). In 1936, a richly illustrated volume decorated with copies of original documents, was published to commemorate the Society's centennial anniversary. Unfortunately, a copy of this valuable book, like many other books owned by the author of this article, was lost during the Shoa.

The City of Miskolc, which had been so hostile to “infidel” Jews at the beginning of the 19th century, and had refused to accept Jewish presence in Miskolc, held a ceremonial assembly in 1861. The resolution issued after the assembly “warmly welcomed the Jewish Council” and concluded: “…the Committee of Miskolc Council Deputies is pleased to take this opportunity to express its sympathy for the Jewish people who shared all the joy and sorrow of our Homeland and our Town. The Honourable Jewish Council must be informed about this resolution which is mentioned in the Minutes.”

The Minutes of the Jewish community, recorded with due regularity since 1832, as well as the Registers of Birth, Death and Marriages, were taken to the Municipal Archives, which returned these in full to the Community after the Second World War. The minutes, containing plenty of instructive and valuable data, would prove a mine of information for historians. Unfortunately, your author did not have time to study these in detail.

There is hardly any doubt that the most interesting personality of our community's history was Binjamin Wolf Bródy (1770-1841), for forty years our community's President. Binjamin, born in Miskolc, was the grandfather of Ernő Bródy, a Member of Parliament. This great philanthropist wrote in his final will (written in Hebrew letters, but Yiddish language, signed and sealed by the former sub-prefect and chief administrative officer of Miskolc): “…hereby, I bequeath 5000 forints to His Royal Highness, my Sovereign and King, as a humble token of my allegiance…” He left various sums and valuable objects to members of his family, and bequeathed also 5000 forints to the Talmud-Torah school so that its interest should be used to cover the salaries of teachers. His houses in Csizmadia and Candia streets were also bequeathed to the school. The “yellow houses” on this property were the first home of Miskolc's Talmud-Torah. Later, the huge Elisabeth school was built on the same site, which later became a public girl's school and the imposing building of the teacher training college. As requested in the Will, a Bródy memorial ceremony was held, together with examinations of the bible classes of the Talmud-Torah boy's school, each year on the 12th day of Shevat.

For present-day readers it may seem quite unusual how often and at what length the Minutes dealt with matters of “leaseholders” and “leases”. The reason is that the Jewish community organised public auctions to lease most of its income-generating licenses. Thus, there were lessees for the butcher's shop, for poultry-slaughtering, the matzos bakery, even the use of prayer houses during the most important Jewish holidays. All this yielded endless debates, complaints and bickering.

But even leaving this out of consideration, harmony was far from perfect within the community. Older, more conservative individuals were in constant discord with younger, more reform-oriented members. In 1861, when construction of the new temple in Kazinczy utca began, a schism developed in the community. The original design of the temple required the organ to be placed above the Ark, and the almemor to be positioned level with the Ark. Because of these reform ideas, the conservatives left the community. Thirty orthodox rabbis, assembled in Sátoraljaújhely, declared a cherem against the Miskolc community. The conflict further escalated when, in 1870, the Miskolc community organised itself into a Reform Judaist congregation[4].

Five years later, the conflicting parties reached an agreement. In the temple a pew was placed between the Ark and the almemor. Peace did not last long, however. Soon, another dispute emerged, this time about marriage ceremonies. As a consequence of the bitter disagreement, a separate Sephardic faction was established under the leadership of a Mr. Strauss, a cloth-dyer, which demanded a separate rabbinate, a separate butcher, a separate school and separate registers of birth, death and marriage. They wanted full autonomy. This, however, was not in line with the intentions of the Central Office of Orthodox Judaism. The school was not established and a new regulation introducing obligatory registration of birth, death and marriages at state registers made the demand for independent registration obsolete, while a separate rabbinate and slaughterhouse had already been realised.

As mentioned earlier, the Jewish community was established in 1765. Wolf (Farkas) Bródy remained president for more than 30 years. The Minutes prove that the Community had a proper constitutional and democratic leadership.

1878 was one of the most distressing years in the history of Miskolc Jewry. As a result of incessant rains, the dikes along the Szinva stream gave way at Hámor. Simultaneously, the small and until then totally peaceful Pece stream also became uncontrollable. The deluge reached the houses on the embankment during the night of August 31st. People were sleeping and utterly unprepared. In the darkness, there was no escape and simple rescue operations also failed. Most of the people that drowned were washed away by the gushing water. Some of the bodies were found later, collected by the Chevra Kadisha and buried in a common grave, later surrounded by an iron fence.

A very nice tradition of the Miskolc Chevra Kadisha (founded in 1767) was the annual cemetery walk, held each year on the day before Erev Yom Kippur. The proceedings began with a commemorative oration held in the cemetery's ritual building. In my time, these speeches – always very heart-gripping and impressive – were held by Chief Rabbi Austerlitz (let his memory be blessed!).

Many members of our Congregation played an outstanding role in Miskolc's economic, social and cultural life, and some held prominent offices at the City Hall. These included Dr. Bertalan Silberger, attorney general, Dr. Ármin Szabó, chief medical officer, Géza Kardos, head of the Remuneration Office, Aladár Bársony, veterinary surgeon, slaughterhouse director, Béla Hegedûs, president of the Orphan's Court, Márk Tyrnauer, judge of the County Court, Árpád Schwartz, district commissioner, Dr. Jakab Venetiáner, director/principal doctor of the district worker's insurance company, Dr. Jakab Kürz, president of the Chamber of Lawyers, Károly Ferenczi, president of the Miskolc Chamber of Commerce, Dezső Fodor, president of the Miskolc Trading Association, and so forth. Several Jews held offices at banks in Miskolc, including Aladár Székely, government counsellor and director of the Hungarian-Italian Bank, Samu Munk, director of the Borsod County Savings Bank, and Adolf Neumann of Héthárs, director of the Trading and Economic Bank. Some actively helped Miskolc's industrial development. These major industrialists included Jenő Herczin machine building, Jenő Guttmann in textile manufacturing, Endre Neményi in silk weaving, the Fried brothers in machine building, the Kun brothers in ironmongery, Albert Schweitzer in wood processing, Andor Nagy in bakery, government commissioner Ödön Győri in distilling, etc. Ödön Győri also served the Community as president for several terms and donated marble sheets used when the Heroes of the First World War Memorial was erected in the courtyard of the Kazinczy street Temple.

The first Rabbi of the congregation, Izrael Mandel, who served also as the Rabbi of the county, was followed by Aser Ansel Wiener. After his death in 1800, his son, Avraham Wiener Posselburg, was elected Chief Rabbi. When he died in 1832, the county rabbinate ceased to exist, and from the 1850s, the communities around Miskolc elected their own rabbis independently. In 1836, the Miskolc congregation elected Mózes Fischmann chief rabbi. He filled this post until his death in 1875. During Fischmann's term, Mór Klein also served the Miskolc Community as Rabbi. He had studied in the Pressburg (Pozsony) and Prague Yeshivas and was widely acclaimed for his outstanding orations and scholastic works. Mór Klein (father of Dr. Arnold Kis, principal Chief Rabbi of Buda) was later elected Chief Rabbi of Pápa and Nagybecskerek, while Miskolc's community elected the former Rabbi of Nádudvar, Mayer Rosenfeld Chief Rabbi in 1879. During his thirty-year presidency (1879 – 1904) many of my contemporaries, members of the presidium and the council who were educated by him, all spoke with the highest esteem and deep emotion about their unforgettable Chief Rabbi. His sons József, later the Rabbi of Csernovitz, and Miksa (who changed his surname to Révai), became a religious teacher in Budapest. His sons-in-law were Lipót Marmorstein, Rabbi at Szenice, SándorJordán, Rabbi at Szatmár, and Artúr Marmorstein, religious teacher in London.

After Rosenfeld's death, Sámuel Spitzer, Rabbi of Kiskunhalas, was invited by the Community. Dr. Spitzer, a man of humble origin, was a most talented and knowledgeable person. He obtained his secular education from private tutors and took a doctorate. The new, secular-educated Chief Rabbi, however, was not popular among the Community's traditionalist members. He consented to weddings to be held within the Temple only after an opening roof apparatus was installed to allow weddings to be held “under the open sky”[5].

Rabbi Spitzer was an austere and profoundly religious person whose vast Halachic knowledge earned high respect among members. In 1908, the third year of his service, he was invited to take the post of Chief Rabbi in Hamburg, which he readily accepted. During his activity in Germany, he was recognised as the second most influential German Orthodox rabbi behind Dr. Breuer, the Rabbi of Frankfurt. He published several important religious studies during these years. His demise in 1936 was mourned widely and in Miskolc, Chief Rabbi Austerlitz rendered homage to Dr. Spitzer's memory in his sermon on the 7th of Adar.

In 1898, Dr. Salomon Spira was elected Chief Rabbi. Dr.Spira was born in 1865 in Homonna and attended the Berlin Orthodox Seminars, later serving the Kula and Losonc communities as Chief Rabbi. In keeping with a new government regulation passed in 1896, his trial sermon was held in the Hungarian language. His excellent rhetorical talent and rich voice soon earned him great popularity. In 1923, on the 25th anniversary of his activity in Miskolc, Dr.Spira was widely celebrated not only by the Jewish Community, but also by the entire Miskolc society. He was already dying and unconscious, when, with other patients of the Ghetto hospital, he was added to an Auschwitz transport in 1944. From this transport, nobody has ever returned – so we cannot know what fate held for him.

In 1914, the year when the First World War began, the Miskolc community elected Samuel Austerlitz as Chief Rabbi. Born in Vienna, Austerlitz became a scholar of unchallengeable authority. He learnt in the Yeshiva of Zussman Sofer in Pacs, and as a young student interpreted the lectures of his master. He obtained his diploma in Pozsony (now Bratislava) and served as Chief Rabbi in Pápa and Somorja. In those times, your author was a student in Pozsony. I can testify that not only we, his students, but many “ordinary” inhabitants of Pozsony travelled to Somorja to listen to his brilliant orations. His Yeshiva in Miskolc earned nationwide acclaim. Austerlitz, the grand master of Temple orations, died of heart failure in 1939. His eulogy was published on his first Jahrzeit by Gyula Groszman, teacher of our public school, under the title Zichron Shmuel [The Memory of Shmuel].

I have compiled a list of Miskolc dayans[6] using sources like the Shem Hagdolim [The name of the greatest], Responsa[7] and haskamas[8]. The names, which follow below, are in chronological order.

First, I have to mention Rabbi Yosef Finkelstein, author of Tzafenat Pa'aneach [after Genesis 41:45], the son-in-law of Meir Avraham of Hejőcsaba, himself the author of Pri Tzadik [The Fruits of the Righteous]. His most active years were in the 1920s.

During the era of Wiener, Chief Rabbis in Miskolc were the noted Rabbi Yechezkel Moshe Lifschitz, who wrote a Foreword to Pri Tzadik in 1830. The next Dayan was David Wiener, the son of Rabbi Abraham Wiener Posselburg. He took his position in 1876.

In 1872, the Community elected the son of Rabbi Schück as Dayan, who later became the Rabbi of Nádudvar. Rabbi Schück was the head of a large dynasty of rabbis. One of his sons, Menachem Schück served in Szikszó, another, Meir Schück, served in Onód, while his son-in-law Prajer served in Poprád, Weisz served in Nagyfalu and Jungreisz in Fehérgyarmat. His successor was Avraham David Hoffmann, later invited to Yugoslavia as Chief Rabbi. After his departure, Yitzhak Aizik Stern, the grandson of the author of Sha'arei Tora, from Abaújszántó, and the brother-in-law of Gerson Rosenbaum, the Rabbi of Tállya, was elected Dayan of Miskolc. His son-in-law, Salamon Weiszmann, the Community's registrar, was a most popular individual in Miskolc.

After the departure of Rabbi Hoffmann, the next Dayan was David Eliyahu Herschkowitz, who later became the Rabbi of the Chevra SHAS [Society devoted to the learning of the Talmud].

From the early 1900s until his death in 1922 Yechiel Fürth, the eldest member of the popular Fürth family, served as Dayan. After his death, Moshe Nathan Blum, the son-in-law of Rosenbaum, the Rabbi of Kisvárda, was elected, but soon he was invited to serve as Rabbi in Nagyvárad. After he left, Shimon Neufeld and the son-in-law Tannenbaum, the Rabbi of Torna, the popular Rabbi of Diósgyőr, was elected Dayan of Miskolc. At that time, the Community established two dayan positions and elected Avraham Ahrenfeld, a most pleasant man, and the son-in-law of Renitz, a former Sephardic Rabbi, to the newly-established position.

The martyrs of Miskolc were escorted to their last journey by these two rabbis.

The first Rabbi of the Sephardic congregation was Mózes Vitriol. He was followed by József Reinitz of Mád. After Reinitz's death the great scholar, Chaim Yakov Gottlieb, the Rabbi of Borsa and Felsővisó and the author of Yagel Jákov was elected Chief Rabbi in 1926. This exceptional man died after ten years of arduous service at the age of 60. As no successor was elected after his death, his rabbinic duties were performed by his son, Gottlieb Juda.

And this is the point where I should like to commemorate the Shochets [ritual slaughterers] of Miskolc: Stein, Davidovics, Klein and Tetelbaum from the Community, and Berkovits and Birnbaum from the Sephardic congregation, none of whom returned from deportation.

In the decade preceding the Shoa, the Presidium of the Community consisted of the following members: Mór Feldmann engineer, President; Mór Mandula educational principal, Vice-President ; Dr. Márton Rosenberger, President of the school committee; Aladár Székely financial principal; temple caretakers: Jakab Edelstein, Salamon Spíró, Ferenc Dávidovics; steward: Miksa Róth, controller: Márton Klein. In addition to the members of the Presidium, the Community's Council also had 15 members elected by the body of representatives. The various affairs of the Community were handled by 13 functional committees (education, religion, etc.). The executive office of the Community was headed by director Jeromos Löw, accountant Jenő Neuländer, and purser Samu Morgenstern. The staff also included three clerks, two temple helpers, the money collectors of the prayer houses and some mashgiachs [supervisors].

Since its establishment in 1767, the Chevra Kadisha[9] played a most important role in the Community's religious life. It was not simply a funeral society but a real Gemilas Chesed[10] institution. In our time, Adolf Neumann of Héthárs was its president, followed by Klein from Csobád, with Ignác Strausz, an intelligent all-rounder serving as its agile clerk. Of the many different charity organisations, the first to begin operations was the Bikur Cholim[11] Society established in 1817, which maintained a hospital together with the Chevra Kadisha. The Israelite Women's Society was organised by the most arduous Mrs. J. Grosz, who also served as chairwoman of the Society for many years. After her death, her position was taken over first by Mrs. Á. Szabó and then by Mrs. P. Munk. This large women's society, incorporating more than 1,200 members, maintained a soup kitchen and offered free clothing to poor school children. The more conservative-minded Deborah Women's Society organised by Mrs. J. Princz was established in 1912. The Society under the leadership of a committee made up of Mrs. D. Reich, Mrs. L. Bónish and Mrs. H. Blitz, set up a home for the aged and offered fuel to the needy.

In Hungary, official Jewish organisations were strongly opposed to the Zionist movement. The fundamentalists were worried that their children, to whom they tried to give strict religious education, will be negatively affected by the liberal-minded Zionist youth groups. On the other hand, the reformed communities, in their nationalistic fervour, considered themselves as the bastion of patriotism. In their eyes Zionism was worse than the original sin.

The middle-of-the-road Miskolc community was one of the two Hungarian communities to support Zionism. The Chief Rabbi Austerlitz himself (blessed be his memory) was a follower of Mizrachi and the Council gave both moral and financial backing to the movement.

A separate Chapter in this book “Zionism in Miskolc” covers this subject in more details.

It is almost unbearably painful to accept that not a single member of the Presidium, the Council and other office bearers has returned from the hell of Nazi death camps. Moreover: none of the prominent people deported, listed above, who had all played such an important role in Miskolc's Jewish community, have survived. Their advice and guidance was ultimately missed when we tried to reorganise our town's religious life after the Shoa.

One of the few to re-emerge after the Holocaust was the late Alfréd Sussman z”l, who embarked on re-organising the Community with unremitting enthusiasm. He spared no effort to re-establish the soup-kitchen and the Community's administrative staff. He made arrangements about the exterior and interior restoration of the Great Temple in Kazinczyutca (with the almemor placed to the centre), the re-start of the elementary school, the building of a large community hall and the renovation of the Matzos factory. Rabbi Austerlitz organised the collection of religious books scattered around Miskolc and the burial of Torah remains found in various places. Finally, it was also Rabbi Austerlitz who arranged the installation of an imposing Holocaust Memorial, designed by engineers Feldmann and Fischer, in the Avas Hill Cemetary.

Unfortunately, his enormous work proved fruitless in many aspects. In burial-grounds nothing but burials can be arranged…

All credit should be given to our brothers and sisters who have remained in Miskolc and whose life we are watching with all our hearts. It is most pleasing to hear that these people are carrying on the torch of Miskolc Jewry with great enthusiasm - the torch that has always served as a guiding light for the Jews in Hungary.

Essay on Kati Marton's article "A Town's Hidden Memory"

published in The New York Times

Kati Marton's article "A Town's Hidden Memory" published in The New York Times on July 21, 2002 aroused the attention of the Miskolc population. Ms. Marton's Jewish-Hungarian grandparents were deported in 1944 from the city of Miskolc. She became angry when some young women working in the nearby pub did not know that there is a Synagogue across the street. Clearly, Marton had certain expectations, and when these were unfulfilled, she concluded that regular citizens in Miskolc were not dealing with their past Her conclusion was that all the citizens of Miskolc are collectively guilty in the deportation of Jews from Hungary to the Nazi death camps And, she felt, that they should acknowledge the terrible events of that period.

The New York Times received a number of letters from the supporters of the protesters, but instead of publishing any one of them, on July 26th the „Times published a letter from a Mr. Frank Shatz with the title "Hungary's Buried Past" in which he referred to Hungarians as Holocaust deniers.

„Indeed, Miskolc is proof that ignorance of past atrocities is endemic even in places where they were perpetrated.”

I must admit that I know very little about this period of my city’s history. (On this point, Kati Marton’s claims about the buried past are correc.). But, is this my fault or that of my history teachers or the leaders of Miskolc?

So I tried to find some sources of history of Miskolc in the WWII.

In 1941, the Jewish population was in excess of 10,000 (about 13.5% of the total population). By the middle of 1942 the fortunes of war were not favouring the Axis powers. This was instantly recognized by Horthy's new prime minister, Nicholas Kállay who was determined to save Hungary from both the Germans and the Russians. Kállay and Horthy refused all demands of the Nazis for the branding, confinement and deportation of the Jews in Hungary. They promised to expel them from Hungary but only after Hitler won the war. Hungarian Jews were protected abroad and negotiations started with the Allies

The road to Auschwitz was opened in March 1944. The German army occupied Hungary and Horthy was forced to appoint a pro-German government. There was no resistance. Horthy and the people looked on passively. A few cheered, even fewer protested.

The British government forbade Palestinian Jewish commandoes to parachute into Hungary and arouse the Jews.(5) The Americans refused to bomb the railway lines leading to Auschwitz. The Canadian government declined to take in Hungarian Jewish children.

Shortly after the Nazi occupation of Hungary in March, 1944, most of the remaining men were sent to labor service camps, and the rest of the Jews were confined to a ghetto. This concentration was carried out in an extremely cruel manner. For example, the police made the following announcement in connection with this action:

"We warn the Hungarian Christian public that certain individuals have placed poisoned lump-sugar by house gates with which they want to endanger the life and health of Hungarian Christian children."1

By June 15, 1944, almost all the Jews had been deported. After the war, about 100 Jews returned from the death camp and some 300 others survived the labor camps. As of 1970, about 1,000 Jews lived in the city.

After the Nazi occupation of Hungary on March 19, 1944, Miskolc was assigned to the third anti - Jewish operation zone (for the purpose of deportation,Hungary had been divided into six zones). The following month most of the remaining men in the city were sent to labor service camps, and the rest of the Jews were put into a ghetto. Those taken to the labor service camps at this time were saved from deportation, and many survived. The concentration of the Jews was carried out with great cruelty under the auspices of the city Prefect, Emil Borbely – Maczky. The gentile population was warned by the police not to interfere with their work. Some three thousand Jews from the surrounding area were concentrated in brickyards outside Miskolc .

In 1970, a thousand Jews were living in Miskolc

. By most estimates, about half the Jewish population is over the age of 65.

Let’s see the Jewish supporter’s letters:

What about the Jewish protester’s letter?

The Hungarian supporter’s opinion:

Some thoughts from the Hungarian protesters:

Which group, the supporters or the protesters are right?

MISKOLC FACES:

1920 to Early 1940s

Return to Miskolc Home Page

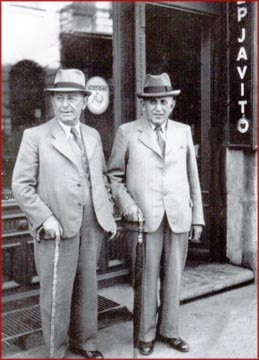

(1) Sandor Kohn (grandfather of Miskolc researcher John Kovacs),

with his brother Aladar, who had a typewriter repair business

in Budapest. (ca. 1942)

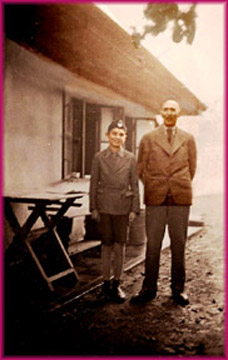

(2) Jeno Grosz with his son Bandi (aged 12), probably in

front of their house in Miskolc (1933). They are the

grandfather and uncle of Miskolc researcher Viviana Grosz-Gluckman.

For other photos of the Grosz family, click here.

|

|

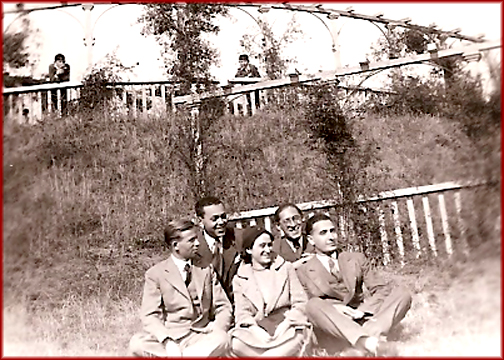

(3) and (4) Josef (Joe) Ungar Grosz (back row, left), in a photo

taken with friends in 1933. Joe, who is the first-cousin-once-removed

of Miskolc researcher Viviana Grosz-Gluckman, emigrated from Hungary to Wilkes

Barre, PA soon after these photographss were taken. If you recognize

anyone else in these photos, please contact the Webmaster.

FAMILY OF HENRIK MANDL AND PEPI GRUNFELD

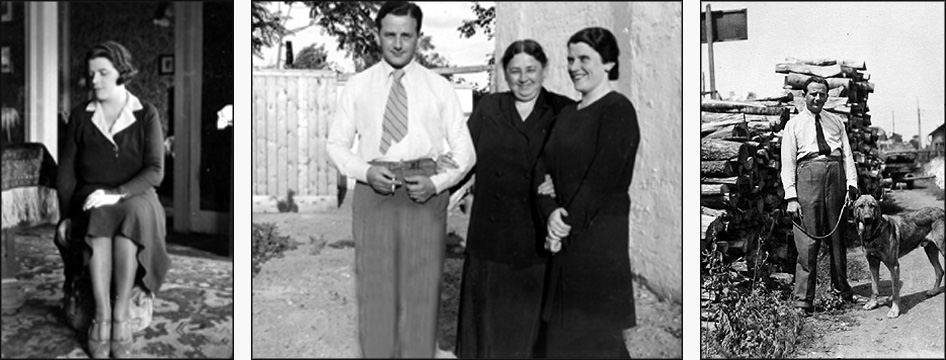

(5) Anna Mandl Rubner, daughter of Lajos Mandl and Szidi Langer (1932)

(6) Jozsef Rubner (husband of Anna), Linka Feldman (Jozsef's mother), Anna Mandl Rubner (ca. 1937)

(7) Forest engineer and lumber merchant Jozsef Rubner in his lumber yard.

Szidi is the grandmother, Anna and Jozsef the aunt and uncle of Miskolc researcher Alan Mandl.

For more information about the Mandl family, click here.