|

|

Salonica and After

The Sideshow that Ended the

War

by

H. Collinson Owen

With a Foreword by General Sir George Milne

|

|

|

|

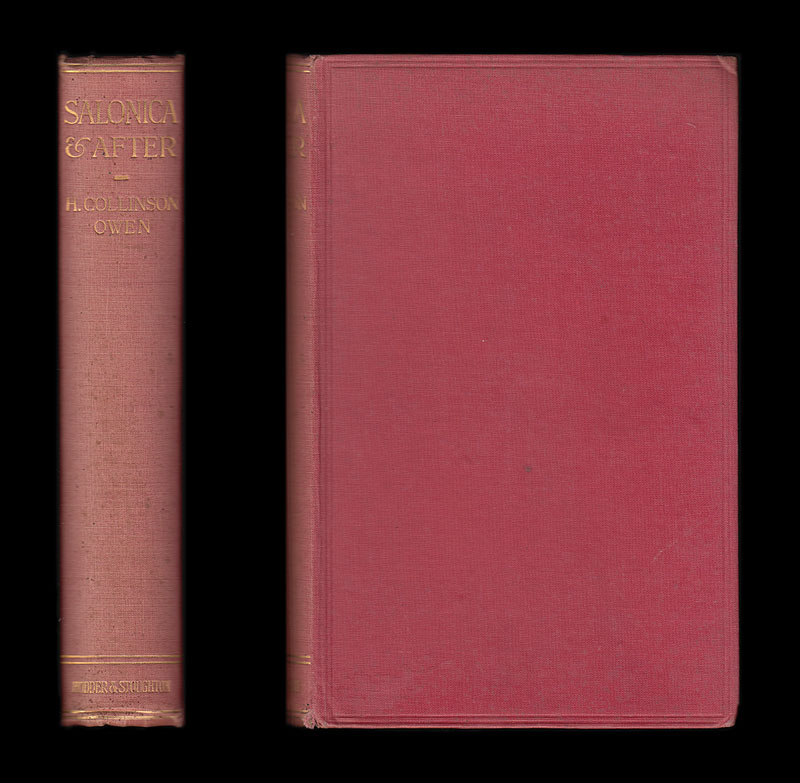

This is

the 1919 First Edition, though suffering from heavy and

unsightly foxing

“This book,

written by the only member of the British Press who has

devoted his whole time to the Macedonian Front, will be

welcomed by the friends and relatives of all ranks of the

British Salonica Army, and of those who have laid down their

lives for their country in a little known part of the

Balkans. It will help to lift the veil of mystery which hung

over the doings of the Army, due to the lack of publicity

given to those events in Macedonia which ultimately led to

the defeat in the field of the Bulgarian Army, worn out by

three years of constant and harassing warfare.” (Foreword)

Collinson Owen was editor of

“The Balkan Times”, official correspondent in the Near East,

and the only member of the British press who devoted his

whole time to the British Salonica Force. His account, with

much on Salonica itself (including a chapter on the Great

Fire of August 1917), includes everyday life and the

political and military events in Macedonia and Salonica and

ends with two Appendices dealing with the role of the RAF

and the problems of dealing with malaria on the Macedonian

Front. This is a valuable eyewitness account of the Salonika

Campaign published within a year of the end of World War

One.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher and place of

publication |

|

Dimensions in inches (to

the nearest quarter-inch) |

|

London: Hodder & Stoughton |

|

5½ inches wide x 8¾ inches tall |

| |

|

|

|

Edition |

|

Length |

|

1919 |

|

[viii] + 295 pages |

| |

|

|

|

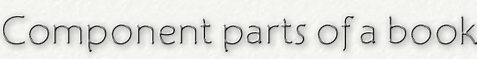

Condition of covers |

|

Internal condition |

|

Original red cloth gilt. The covers are

scuffed, rubbed

and faded, with some variation in colour and evidence of old staining. The fading is

quite pronounced on the spine, though the gilt blocking remains reasonably bright.

The spine ends and corners are bumped and there is some fraying to the ends

of the spine gutters, particularly the front bottom spine gutter, where the

cloth is split. |

|

There are two vertical creased down the front

free end-paper. The inner hinges are a little tender and there is some

separation between the inner gatherings. There are no internal markings but

there is, unfortunately, heavy and unsightly foxing throughout, and

particularly on those pages (including the Title-Page) adjacent to the

photographic illustrations (please see the images below). For much of the

text sections, the foxing is confined to the margins. The edge of the text

block is grubby, dust-stained and foxed. |

| |

|

|

|

Dust-jacket present? |

|

Other

comments |

|

No |

|

Collated and complete but in somewhat faded covers

and with particularly heavy foxing throughout. |

| |

|

|

|

Illustrations,

maps, etc |

|

Contents |

|

Please see below |

|

Please see below |

| |

|

|

|

Post & shipping

information |

|

Payment options |

|

The packed weight is approximately

700 grams.

Full shipping information is

provided in a panel

at the end of this listing.

|

|

Payment options

include-

UK buyers: cheque (in

GBP), money order, cash, debit card, credit card (Visa, MasterCard but

not Amex), PayPal

-

International buyers: credit card

(Visa, MasterCard but not Amex), PayPal

Full payment information is provided in a

panel at the end of this listing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Salonica and After

Contents

I.—Getting there

II.—When the B.S.F. was Young

III.—Salonica Nights

IV.—A Day in Town

V.—The "B.N."

VI.—Friends up Country

VII.—" The Coveted City "

VIII.—The Fire

IX.—Two Balkan Days—January July

X.—The Balkan Stage

XI.—Ourselves and our Allies

XII.—The Army from Without

XIII.—The Conversion of Greece

XIV.—Mud and Malaria

XV.—Home on Leave

XVI.—The Allied Operations

XVII.—Doiran

XVIII.—Victory

XIX.—The Pursuit

XX.—. . . . And After

Appendix I.—Work of the 16th

Wing R.A.F.

Appendix II.—A Note on Malaria

Index

Illustrations

-

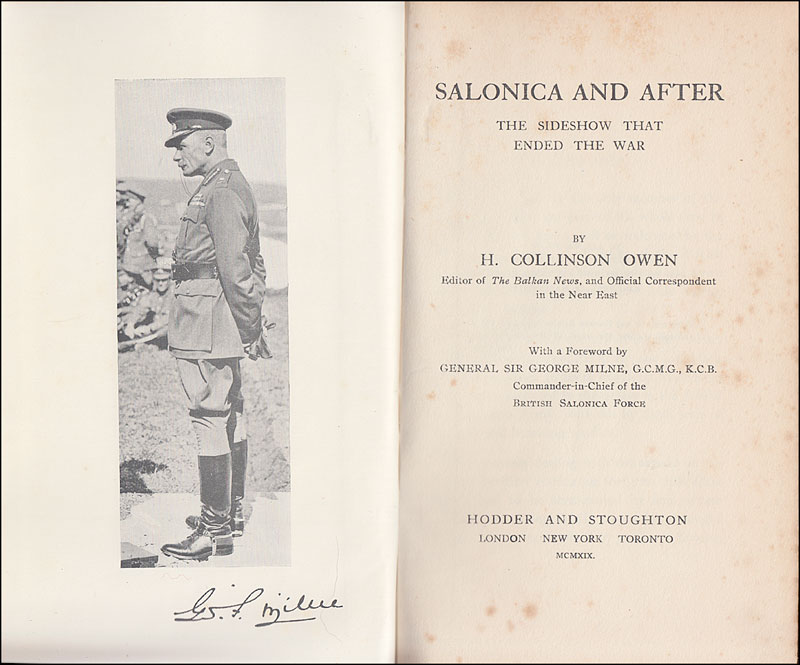

General Sir George Milne, G.C.M.G.,

K.C.B., at a Horse Show at Guvesne -

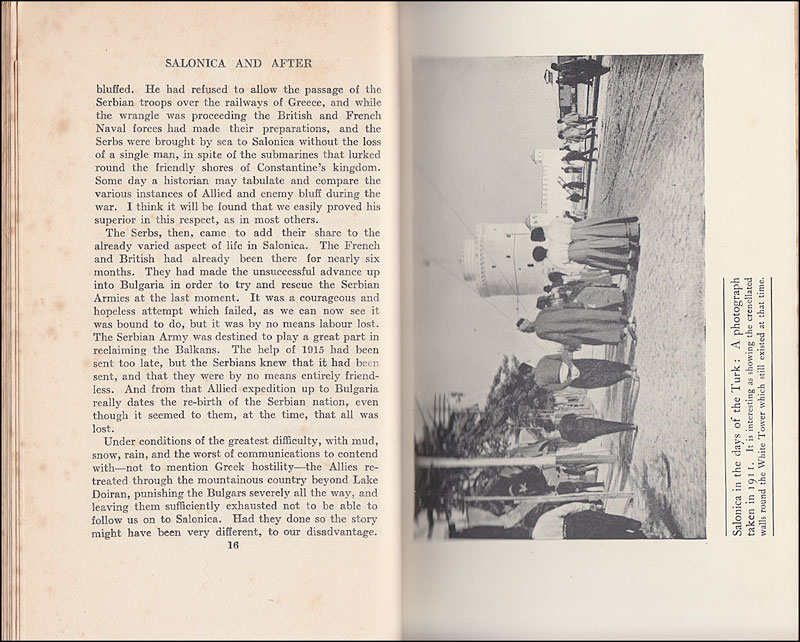

Salonica in the days of the Turk:

a photograph taken in 1911. It is interesting as showing the

crenellated walls round the White Tower which still existed at

that time -

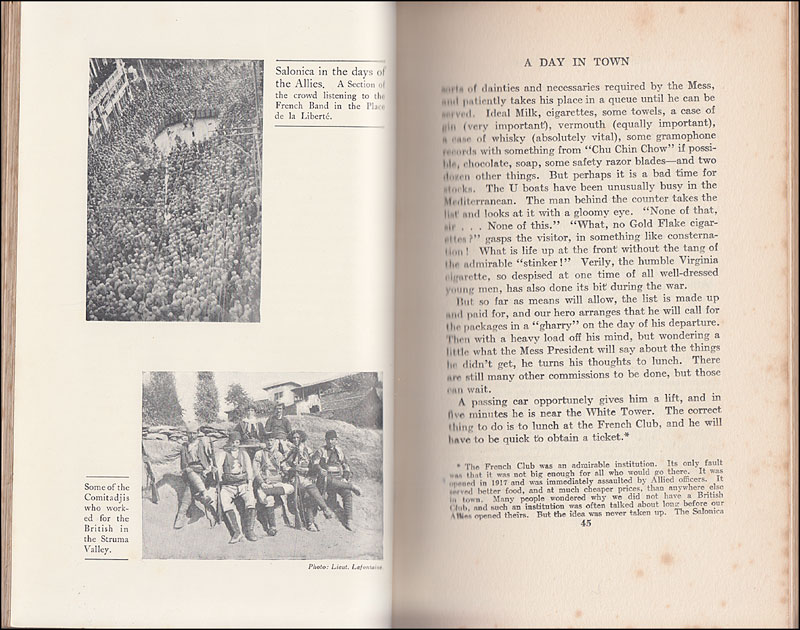

Salonica in the days of the

Allies. A section of the crowd listening to the French Band in

the Place de la Liberte . -

Some of the Comitadjis who worked

for the British in the Struma Valley -

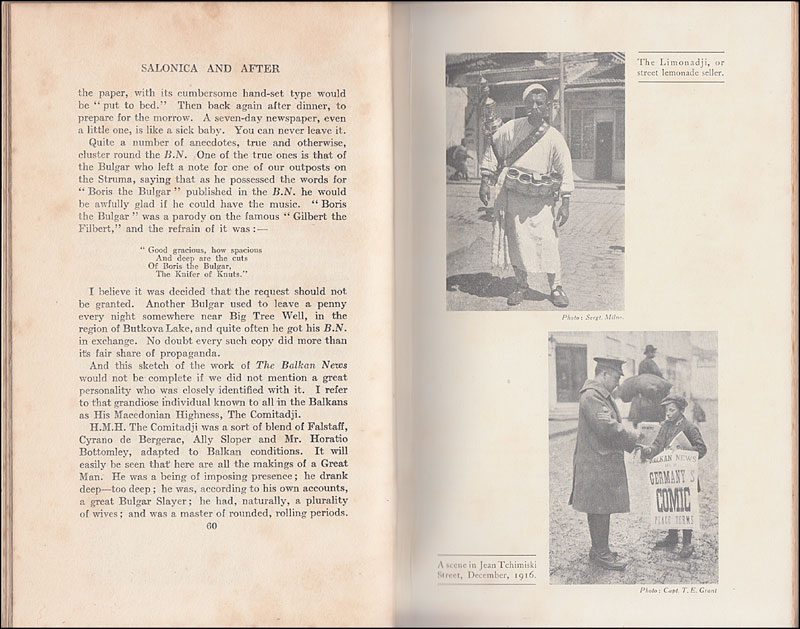

A scene in Jean, Tchimiski Street,

December, 1916 -

The Limonadji, or street lemonade

seller -

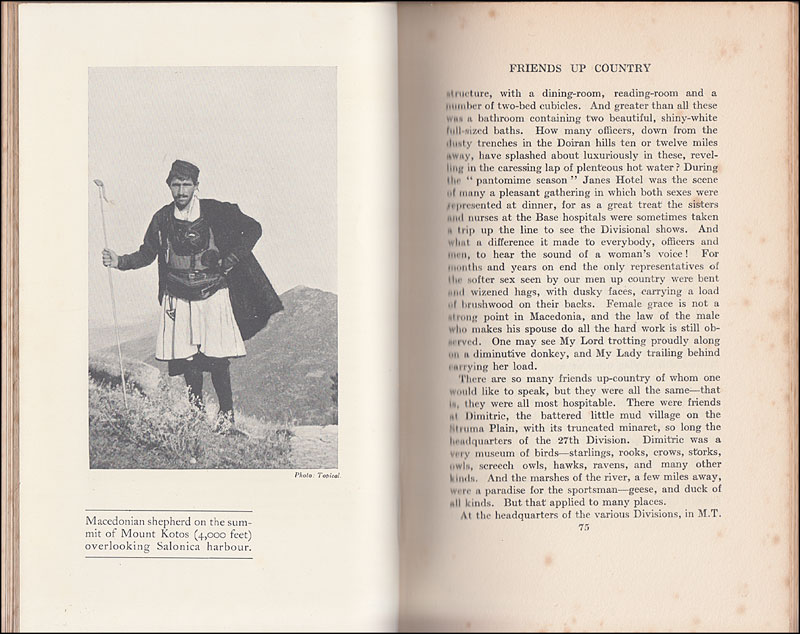

Macedonian shepherd on the summit

of Mount Kotos (4,000 feet) overlooking Salonica Harbour -

Salonica the day after the fire. -

British Transport in Macedonia: A

typical road on a summer day -

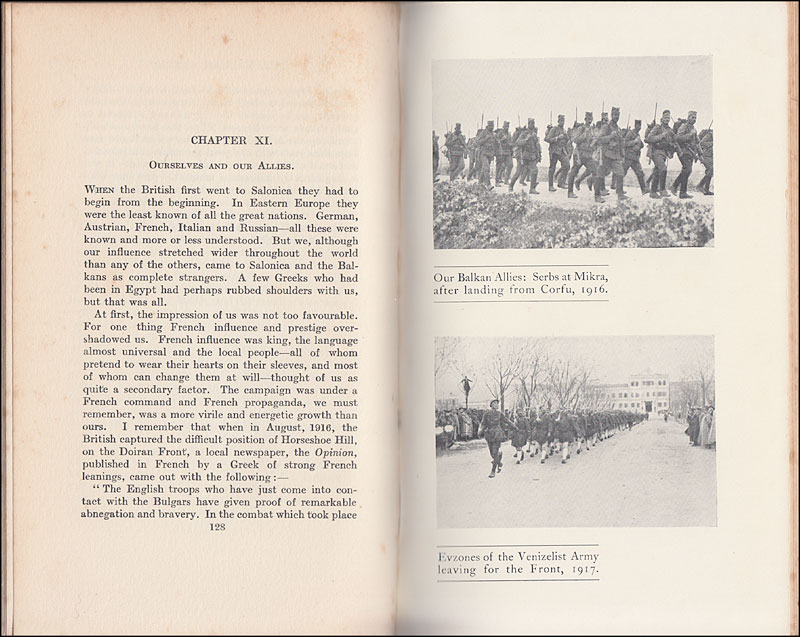

Our Balkan Allies: Serbs at Mikra,

after landing from Corfu, 1916 -

Evzones of the Venizelist Army

leaving for the Front, 1917 -

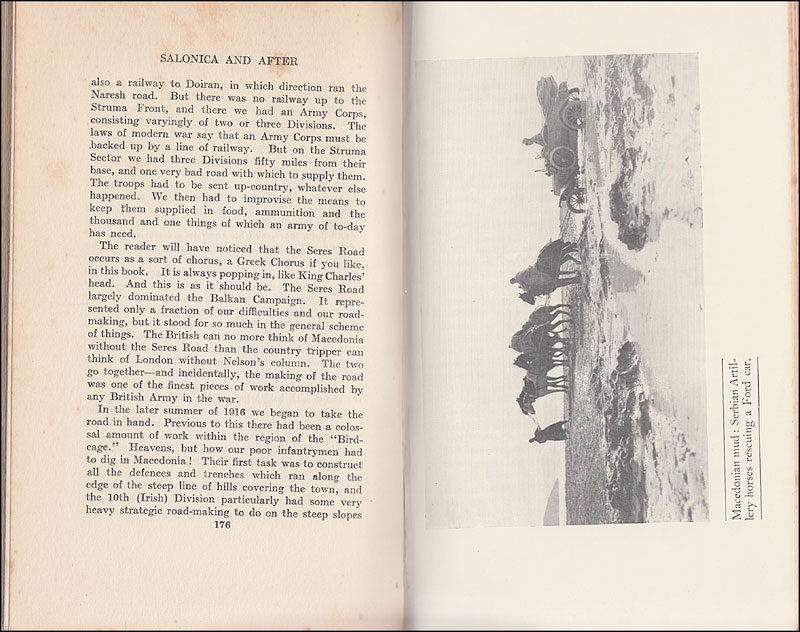

Macedonian mud : Serbian Artillery

horses rescuing a Ford car -

The Pass Road from Bralo down to

Itea -

Macedonian " Ladies " breaking

stones for road-making -

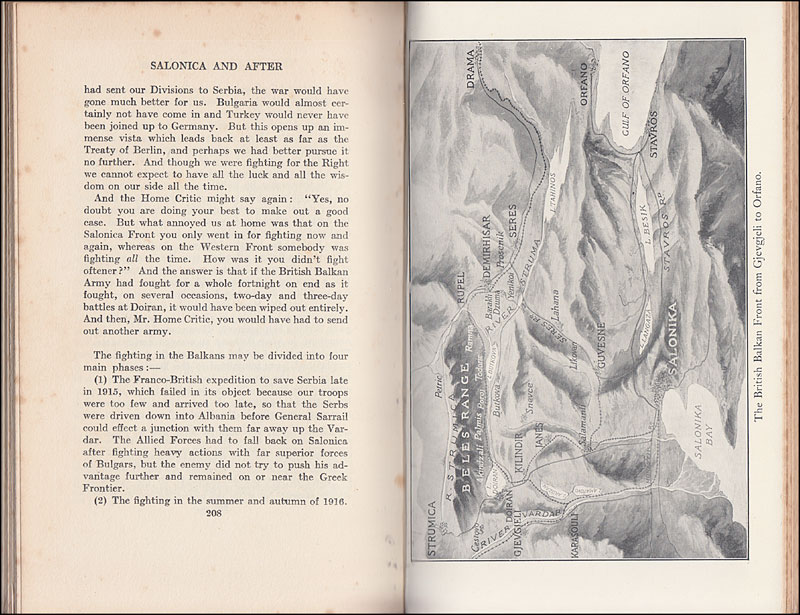

The British Balkan Front from

Gjevgjeli to Orfano -

Doiran, showing Tortoise Hill,

Jumeaux Ravine and Petit Couronne on the left just above the

lake. From here the hills rise upwards, over Doiran Town, to

Grand Couronne, with its scarred crest. Dominating Grand

Couronne is seen the undulating Pip Ridge, and beyond this again

the snow-clad mountains of Serbia -

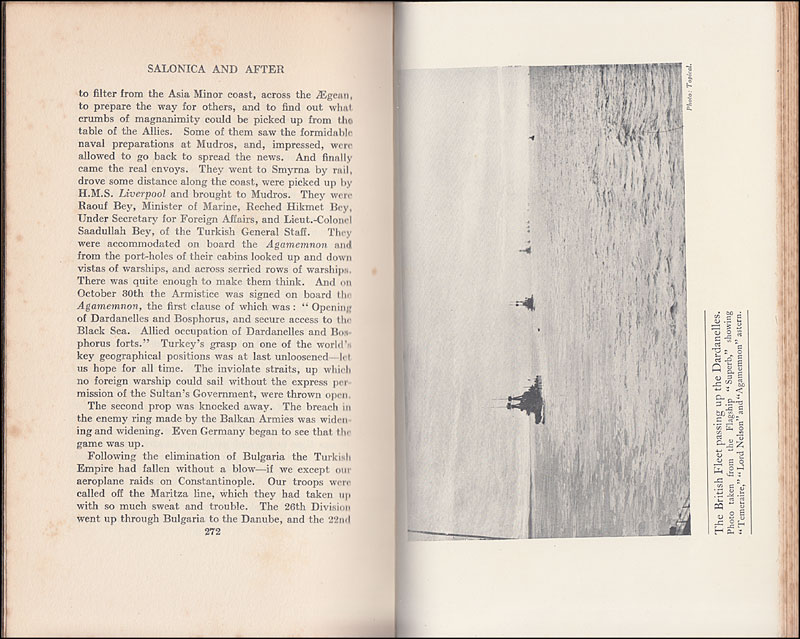

The British Fleet passing up the

Dardanelles. Photo taken from the Flagship Superb, showing

Temeraire, Lord Nelson and Agamemnon astern

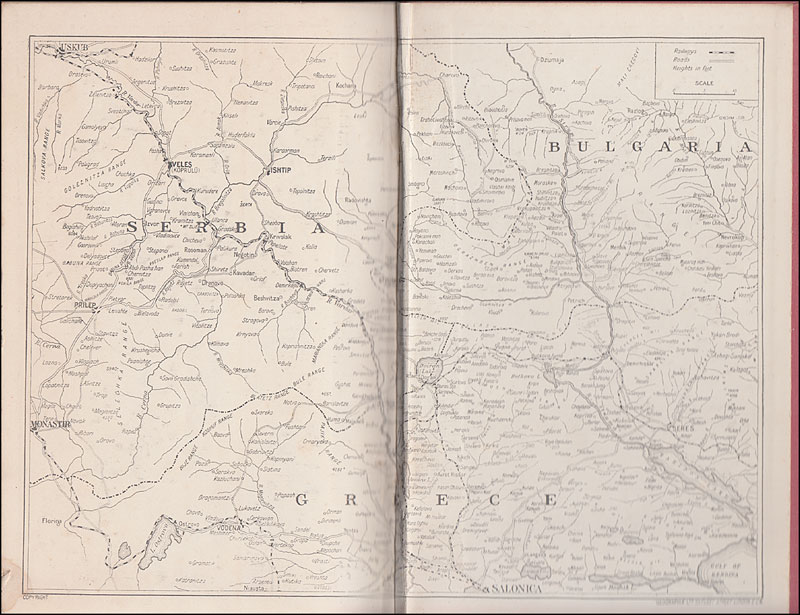

A map of the Balkan Front (rear

end-papers : please see the final image below)

|

|

|

|

|

Salonica and After

Foreword

This book, written by the only member of the British Press who has

devoted his whole time to the Macedonian Front, will be welcomed by

the friends and relatives of all ranks of the British Salonica Army,

and of those who have laid down their lives for their country in a

little known part of the Balkans.

It will help to lift the veil of mystery which hung over the doings

of the Army, due to the lack of publicity given to those events in

Macedonia which ultimately led to the defeat in the field of the

Bulgarian Army, worn out by three years of constant and harassing

warfare.

The chapters dealing with the attacks on the Doiran position

summarise the great difficulties which had to be surmounted by men

whose strength was being slowly sapped by prolonged residence in the

most unhealthy portion of Europe, but whose esprit de corps was of

the highest and whose faith in ultimate victory never faltered.

This book may help some to see in proper perspective how the

crowning achievement of long and weary vigil in a secondary theatre

of operations struck at the Achilles heel of the Central Powers and

materially aided in their rapid collapse during the dramatic Autumn

of 1918.

(Signed G. Milne)

General.

Advanced General Headquarters, Guvesne, Macedonia.

Author’s Note

The publication of this book, which was written in the earlier part

of the present year, was delayed for some months owing to the Author

being abroach But this proves to have been a happy thing, as in the

meantime Ludendorff has given us his Memoirs, and these support in

signal fashion all that is here claimed for the Balkan Front, and

show that the sub-title, " The Sideshow that Ended the War," is in

no sense an exaggeration, but is a plain statement of military fact.

Had the book been published earlier in the year, no doubt many

people would have taken exception to this description, and said that

the Author was too easily carried away by his enthusiasm for his

subject. But if anybody knows exactly why our enemies crumbled up so

suddenly and dramatically Ludendorff should. We will examine very

briefly what he says on the subject of the break-through on the

Balkan Front in September, 1918.

Writing of the Allied 1918 offensive on the Western Front,

Ludendorff says (Times, August 22nd, 1918) :— " August 8 was the

black day of the German Army in the history of this war. This was

the worst experience that I had to go through except for the events

that, from September 15 onwards, took place on the Bulgarian Front

and sealed the fate of the Quadruple Alliance."

The comment of the Times on Ludendorff's own description of the

march of events on the Western Front is as follows :—

" The other fact that stands out was the defeat of the Bulgarian

Army, a fact which in Ludendorff's mind seems completely to have

overshadowed the sensational victory of the British Army at Cambrai

at the end of September." Another Press comment on the same point

was : " When Bulgaria, too, went, he threw up the sponge, and even

the tremendous British victory in forcing the Hindenburg Line is

dismissed in a few words as a mere incident in the general ruin."

Ludendorff himself continues :—" It very soon became clear that from

Bulgaria nothing more was to be expected. . . . . The position in

the field could only become decidedly worse. It was impossible to

tell whether this process would be slow or precipitate. I The

probability was that events would come to a head within a measurable

time, as indeed actually happened in the Balkan Peninsula and on the

Austro-Hungarian Front in Italy.

" In this situation I felt incumbent upon me the heavy

responsibility of hastening the end of the war and of promoting

decisive action on the part of the Government.'''

The British Salonica Force could not desire a more striking tribute

to its long devotion and ultimate triumphal success than these few

plain words from Ludendorff. Together with the famous letter from

Hindenburg in which, speaking of the Bulgarian collapse, he said, "

It is no longer possible for us to resist; we must ask for an

armistice," they demolish all that was ever said in criticism of the

value of the Salonica Army and at the same time lift that Force to

its rightful place in the history of the Great War.

H. C. O.

London, August, 1919.

|

|

|

|

|

Salonica and After

Chapter I.

Getting There.

" Whoever would have dreamed of coming

to Salonica?" sighed a melancholy and homesick young captain from up

the line. We were sitting in the famous cafe of Floca—famous not for

any startling merits on the part of Floca Freres, but just because

it was our premier cafe, and the rendezvous of everybody in

general—and the world must have a rendezvous, even in Salonica.

Outside, through the newly glazed windows, we looked upon the

charred skeletons of the buildings destroyed in the great fire—a

conflagration which should really be referred to as the Great Fire,

and will always so be thought of by those who saw it.

And inside the flies were buzzing merrily—or fiercely—for the heat

had come early, and they were in the first flush of their spring

ardour. They settled on our hands, heads and faces, tickling, biting

and enraging us. They buzzed round in clouds exploring milk jugs,

beer pots, sticky cakes on plates (gateaux mouches, as somebody

wittily called them) and generally behaving as all flies in the Near

East do, as if to make up by their extravagance of vigour for the

natural indolence of the inhabitants. And the flies were merely the

sauce piquante, so to speak, to the general boredom and weariness of

men who had been living for years without leave in a distressing

country which they heartily disliked. The captain from up the

line—like many others—had not seen home for over two and a half

years. He was weary of Macedonia, and his heart longed fiercely for

home—"Blighty" on a wet evening if you like, with the lights turned

low and all the theatres showing their "House Full" boards, but "Blighty"

under any conditions if the impossible could only happen. And the

sigh that welled up from him de Profundis, "Whoever would have

dreamed of coming to Salonica?" spoke volumes.

But to pass from his melancholy, which was a very common symptom in

Macedonia, whoever would have dreamed of coming to Salonica ? True

it is now a household name, like " Plugstreet," Mesopotamia, and

many other blessed words. But before the war who could have taken

his atlas and, putting down his finger, said triumphantly, "There is

Salonica!" True, we knew it existed somewhere, like Syracuse or

Antananarivo. But very few people in our world knew anything more of

it than its bare existence. St. Paul, we might remember, once wrote

an epistle to the Thessalonians. But very few people, again, ever

dreamed of connecting, however distantly, " certain lewd fellows of

the baser sort" with the people of the modern city where Jew meets

Greek in a perpetual tug of war. England, in short, never had any

business with Salonica, and never expected to have any. It was as

far removed from our ken as any place on the map could be. Belgium

had been swallowed up; Paris had been menaced and saved; the battle

of Loos had been fought and lost; Gallipoli had flared up with

heroic glory and died down into a smoulder of forlorn hopes, and

some people were already talking of " war weariness "—and still we

had not heard of Salonica. And then there came a sudden and

unexpected turn in the wheel of war. A new name appeared in the

newspaper headlines—Salonica—and the convenient maps that

accompanied the news of our men landing there showed exactly where

it lay. The military critics told us exactly what the new expedition

meant, and all it was going to do. Torres Vedras was mentioned, and

what Wellington did. The public was much excited and waited eagerly

for the glad news that history had repeated itself. (It came indeed,

but after how many delays and doubts and grumblings ?) The amateur

strategist played joyfully with the latest idea, and trotted happily

up and down a new country which looked delightfully small and easy

on the map. The first exchange of shots was opened which developed

into the long-drawn battle between Easterners and Westerners. The

immediate doom of the Turk was announced. People said, "By the way,

is it Saloneeka or Salonika or Salonyker?" And so the new word—in

various disguises—passed into the language.

And there it will remain. The many thousands of men of the British

Armies who passed through it into Macedonia, and carried the Old

Flag into lands where it had never been seen before; or who trod its

uneven cobbles on very occasional leave; or lay weak with fever or

wounds in the great hospitals that ringed it round, will see to

that. They may have loathed Salonica as they loathed, in earlier

days, the six o'clock hooter on a Monday morning. But in their minds

it stands for Victory. And they will not let it be forgotten. When

to-morrow's children are listening to stories of Ypres and Cambrai

and Neuve Chapelle a great many others will be listening to what

happened in Salonica and beyond.

The new name had not yet lost its first flush of popularity at home

when the writer received an intimation that his humble services

might be useful to the British Army . . .

Chapter IV.

A Day in Town.

Everything in this life, or presumably

any other, is relative. The soldier whose lot it was, pleasant or

otherwise, to work in Salonica thought of leave only as a journey

home to England. But the soldier up the line had a different point

of view. Leave for Home was a thing hardly to be dreamed of. But for

the officer there was always the possibility of leave to Salonica,

although it was not until late in the campaign that it was possible

to bring parties of men down, and some of these saw their first town

for two and a half years.

The man who lived in Salonica might sometimes wonder why on earth

anybody should ever want to get leave to visit it. But the man

up-country had no doubts on the point. On a number of occasions,

after an absence of a week or ten days up-country, I have myself

been pleasantly excited to enter the town again, and see people once

more, and tramcars and shops. And it was therefore easy to imagine

the joy of officers up-country who, after four or six months in the

wilderness, with perhaps a squalid little village as the highest

mark of civilisation, came down to town with three days' leave.

They made the very most of it, like schoolboys in the first flush of

a holiday. And yet their trip to town always had its duties and

responsibilities. Each officer so favoured always came down with a

long list of commissions to be executed for his battalion, so that

the last two of his three days in town were generally filled up with

tramping up and down the uneven cobbles in quest of things for

others. And it was remarkable how faithfully and painstakingly this

sort of thing was always done.

For long the weekly journals at home, humorous and otherwise, were

filled with little articles describing the joys or trials of our

officers and men coming home to England for a few days' leave. The

story always began at Armentieres, or "The Salient," or some equally

famous spot, and finished up at Victoria. Exactly the same incidents

were common to the life of our men out in Macedonia, with only local

differences, but Bairnsfather has not limned them nor have

contributors to "Punch" let their fancy play on them. France

overshadowed all, and for the average reader at home "Leave" meant a

trip across the Channel in the Boulogne boat. They could not imagine

that large numbers of their countrymen sat on barren hills just

short of Doiran, or in the malarial plain of the Struma, and looked

with much longing towards a higgledy-piggledy city of the Aegean,

some fifty miles away. Victoria did not enter their thoughts. It was

out of the question— reserved only for those lucky people who

campaigned in France. Salonica represented all that there was to

hand of civilisation and, if you like, joie de vivre. It was a poor

enough substitute, but the very most was made of it on the rare

occasions when those of the frontline could visit it.

Out in Macedonia the first throb of excitement came, say, on Tortue

Hill, just below the sinister Grand Couronne, or at some outpost of

ours on the plain facing the Rupel Pass. In the one case it meant a

long ride to the railway, and then a tedious all-night journey in

the train; in the other, a ride to the 70th Kilometre . . .

Chapter VIII.

The Fire.

Saturday, August 18th, 1917, is a day

that will be long remembered by many thousands of members of the

Salonica Force. They may not always be able to recall the date

itself, but they will never forget the fire that occurred on it,

when nearly a square mile of the city was burned down in a few

hours.

In those days I lived in a very pleasant and roomy apartment above

one of the town's big shops. It was a very hot day, and the local

Sirocco—a hot wind from the direction of the Vardar — was blowing half

a gale, and had been doing so for two or three days. I was sitting

at tea, clad as lightly as the conveyances would allow, when

Christina, the Greek maid from Constantinople, came in with some

more hot water.

" You know there is a big fire," she said. " They say half the town

is burning."

One accepted this as mere exaggeration, and so it was at the moment.

But a little later I went up on to the flat roof to look. From here

one had a view of practically the whole of the city and its

surroundings. And sure enough, away up the hill in the north-western

corner of Turkish Town, there was a big blaze in progress. Through

glasses I could see a sailor standing on a roof semaphoring with his

arms. It looked as though a considerable area was alight, and the

hot wind was blowing strongly and steadily down towards our part of

the city. Then I became aware that dozens of the springless,

rattling carts that make life hideous, were dashing over the cobbles

and up the hill, presumably having been engaged for salvage work.

But big as the fire looked it seemed a very remote thing, having no

concern with one's own existence. Naturally a lot of these

half-wooden houses would be burnt' down, and Turks and Jews would be

homeless ! But life is sometimes hard and one must expect these

things ! I went down again and began to make preparations for a

journey up Monastir way.

Perhaps rather less than an hour later I went up to have another

look. Jove, but the fire had made progress ! In the foreground

people were standing on roofs, free from concern and enjoying the

spectacle. But it began to look ugly, with that dry, hot wind like a

forced draught blowing continuously. I went down to the street,

where the car was waiting.

" Mason," I said, " I don't think we shall go up-country to-day. It

looks to me as though there won't be any Salonica left to-night."

" Very good, sir," said Mason. " I heard there was a fire

somewhere."

Mason, who was a corn merchant in a comfortable way of business at

home, was always like that.

At the office I found that people were becoming slightly concerned,

although there was no sense of impending trouble. The natives of the

city were convinced that it would not spread far. They too felt,

although they did not say it in so many words, that although the

fire might destroy the native quarters, it would not have the bad

taste to come down into the more or less civilised parts of the

city.

I decided to go up and have a look at the scene of the

conflagration. Egnatia Street was jammed, and we met the first

refugees carrying bits of furniture, pushing through the press. A

little way up one of the side streets, that climbs the hill

northwards, we had to leave the car. Turks and Jews, with wild eyes,

were hurrying down, carrying all sort's of things. A little further

and we were on the edge of the burning quarter; and the tide of

distracted, homeless people was flowing all around us.

It was an extraordinary sight, and one which but for the sewing

machines and smashed wardrobe mirrors which littered the narrow

streets and alleys, might have been plucked straight from Biblical

times. This was the heart of the Salonica Ghetto, where a great

proportion of the population still preserved their ancient costumes.

Here were to be seen, in scores, white-bearded patriarchs wearing

fezzes and their old-time gaberdine costume known as the intari,

rushing about frenzied] y in spite of the skirts that clung round

their slippered feet. Their women-kind rushed about with them,

holding their children by the hand and sobbing, shouting and

imploring. It was an amazing and a sad scene; the wailing families,

the crash of falling houses as the flames tore along, swept by the

wind; and in the narrow streets a slow-moving mass of pack donkeys,

loaded carts, hamate carrying enormous loads; Greek boy scouts (who

were doing excellent work); soldiers of all nations, as yet

unorganised to do anything definite; ancient wooden fire-engines

that creaked pathetically as they spat out ineffectual trickles of

water; and people carrying beds (hundreds of flock and feather

beds), wardrobes, mirrors, pots and pans, sewing machines (every

family made a desperate endeavour to save its sewing machine) and a

general collection of ponderous rubbish. The evacuation of each

street came in a panic rush as its inhabitants realised that their

homes also were doomed. This attitude of only believing at the very

last moment that there was any danger for their own homes or

business establishments, marked the whole progress of the fire until

the moment when it had reached the edge of the sea and was blazing

along nearly a mile of front. The inhabitants of every separate line

or section of streets were convinced that the conflagration was

going to pass them by. A quarter of an hour later they were fleeing

for their lives, bearing all sorts of absurd household goods snapped

up in panic moments. As it was the Jewish Sabbath many of the big

shops were closed, and jewellers and others did not appear to try

and save their stocks until a late hour. At ten o'clock that night,

people in hotels on the water front did not think their sleeping

arrangements would be disturbed—and were bolting with their hand

luggage at eleven.

Amid the medley and the uproar of the fire up in the Ghetto I found

the P.M. It was a difficult situation for any administrative officer

to face. The local means for fighting a fire were nil, or next to

it. It was not easy to say in whose hands lay the material and moral

responsibility for tackling the fire, and here was a case in which a

mixed command presented difficulties. Moreover, the fire had

attained its alarming proportions with such a sudden rush that

everybody was taken off their guard. And the " native" quarter

seemed a place off everybody's beat. The Allies only visited it for

a stroll or from curiosity. It was, in a vague way, nobody's

business—until suddenly, like a thunder-clap, it became apparent

that it was everybody's business. At about this time a company of

the Dur-hams arrived from the garrison battalion down in Beshtchinar

Gardens, to form a cordon. But that did not help to put out the

fire, and there were still no fire-engines, and little water to go

through them . . .

Chapter XVI.

The Allied Operations.

Though during the long three-years

campaign in the Balkans there were many periods of enforced

comparative inactivity during which only the regular growling of the

artillery and the work of the patrols and the Allied aviators kept

up the offensive spirit, there was far more fighting in the

aggregate than most people in the outside world realised, and

amongst them the various Allies—Serbians, French, British, Italians,

even Russians, and, finally, the Greeks—laid down many thousands of

lives on the barren mountains that mark the frontiers of Serbia,

Greece and Bulgaria.

The Allied move out of the " Birdcage " in the spring and early

summer months of 1916 to take up positions along the Greek frontier

where the enemy—Bulgars, Germans, Austrians and Turks—had now

entrenched themselves on most formidable positions, was followed by

a long period during which change, re-arrangement, marching and

counter-marching seemed to go on interminably. This was due to

various causes; to " bluff " on both sides; to a proposed Allied

Offensive along the Vardar, which had to be abandoned because the

Bulgars got in first with their own attack on the left of the Allied

line, against the Serbs; and also because of the fact that at first,

owing to a number of reasons, British and French Divisions were

mixed up in rather higgledy-piggledy fashion. The troops, who knew

nothing of any of the reasons dictating these changes, found

themselves committed to a good deal of hard and exasperating

marching and counter-marching in exhausting heat, which seemed to

lead to nothing in particular. Then the Italians who in September

took up a twenty-five mile line on the Krusha-Balkan sector, between

Lake Doiran and the Struma Valley, came as another dividing wedge

between the two wings of the British front. It was not until towards

the end of 1916 that the British finally settled down on the line

running from the Vardar to Doiran, round the elbow made by the

Krusha-Balkan range and so down the long Struma Valley to the sea—a

distance of about ninety miles. This very extended front was held

for two and a half years. Along its whole length we were dominated

by enemy positions which were always markedly superior in

strength—and height—and as a rule immensely superior. It was a crazy

front, like the whole of the Balkan front, and zig-zagged up and

down steep hills, in and out of ravines, ran along the tops of high

ridges and finally brought us up on the Struma with its odd mixture

of open and position warfare. To hold this very long front, always

against superior forces, we had as a maximum four Divisions, much

weakened by sickness and casualties. The 10th Division, after its

gallantry and hardships in the retreat down from the Bulgarian

frontier in 1915, took part in some stiff and successful fighting in

the Struma Valley in 1916, and went to Palestine in September, 1917,

there to win fresh laurels. The 60th Division, which only arrived in

the Balkans in December, 1916, also went to Palestine in June, 1917,

and saw comparatively little service in the Balkans, although it was

to see plenty under General Allenby later on and to play a big part

in his victories. At about the same time the 7th and 8th Mounted

Brigades also went to Palestine . . .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please note: to avoid opening the book out, with the

risk of damaging the spine, some of the pages were slightly raised on the

inner edge when being scanned, which has resulted in some blurring to the

text and a

shadow on the inside edge of the final images. Colour reproduction is shown

as accurately as possible but please be aware that some colours

are difficult to scan and may result in a slight variation from

the colour shown below to the actual colour.

In line with eBay guidelines on picture sizes, some of the illustrations may

be shown enlarged for greater detail and clarity.

|

|

|

|

IMPORTANT INFORMATION FOR PROSPECTIVE

BUYERS |

|

|

U.K. buyers:

|

To estimate the

“packed

weight” each book is first weighed and then

an additional amount of 150 grams is added to allow for the packaging

material (all

books are securely wrapped and posted in a cardboard book-mailer).

The weight of the book and packaging is then rounded up to the

nearest hundred grams to arrive at the postage figure. I make no charge for packaging materials and

do not seek to profit

from postage and packaging. Postage can be combined for multiple purchases. |

Packed weight of this item : approximately 700 grams

|

Postage and payment options to U.K. addresses: |

-

Details of the various postage options (for

example, First Class, First Class Recorded, Second Class and/or

Parcel Post if the item is heavy) can be obtained by selecting

the “Postage and payments” option at the head of this

listing (above). -

Payment can be made by: debit card, credit

card (Visa or MasterCard, but not Amex), cheque (payable to

"G Miller", please), or PayPal. -

Please contact me with name,

address and payment details within seven days of the end of the auction;

otherwise I reserve the right to cancel the auction and re-list the item. -

Finally, this should be an enjoyable

experience for both the buyer and seller and I hope you will

find me very easy to deal with. If you have a question or query

about any aspect (postage, payment, delivery options and so on),

please do not hesitate to contact me, using the contact details

provided at the end of this listing.

|

|

|

|

|

International

buyers:

|

To estimate the

“packed

weight” each book is first weighed and then

an additional amount of 150 grams is added to allow for the packaging

material (all

books are securely wrapped and posted in a cardboard book-mailer).

The weight of the book and packaging is then rounded up to the

nearest hundred grams to arrive at the shipping figure.

I make no charge for packaging materials and do not

seek to profit

from shipping and handling.

Shipping can

usually be combined for multiple purchases

(to a

maximum

of 5 kilograms in any one parcel with the exception of Canada, where

the limit is 2 kilograms). |

Packed weight of this item : approximately 700 grams

| International Shipping options: |

Details of the postage options

to various countries (via Air Mail) can be obtained by selecting

the “Postage and payments” option at the head of this listing

(above) and then selecting your country of residence from the drop-down

list. For destinations not shown or other requirements, please contact me before buying.

Tracked and "Signed For" services are also available if required,

but at an additional charge to that shown on the Postage and payments

page, which is for ordinary uninsured Air Mail delivery.

Due to the

extreme length of time now taken for deliveries, surface mail is no longer

a viable option and I am unable to offer it even in the case of heavy items.

I am afraid that I cannot make any exceptions to this rule.

|

Payment options for international buyers: |

-

Payment can be made by: credit card (Visa

or MasterCard, but not Amex) or PayPal. I can also accept a cheque in GBP [British

Pounds Sterling] but only if drawn on a major British bank. -

Regretfully, due to extremely

high conversion charges, I CANNOT accept foreign currency : all payments

must be made in GBP [British Pounds Sterling]. This can be accomplished easily

using a credit card, which I am able to accept as I have a separate,

well-established business, or PayPal. -

Please contact me with your name and address and payment details within

seven days of the end of the auction; otherwise I reserve the right to

cancel the auction and re-list the item. -

Finally, this should be an enjoyable experience for

both the buyer and seller and I hope you will find me very easy to deal

with. If you have a question or query about any aspect (shipping,

payment, delivery options and so on), please do not hesitate to contact

me, using the contact details provided at the end of this listing.

Prospective international

buyers should ensure that they are able to provide credit card details or

pay by PayPal within 7 days from the end of the auction (or inform me that

they will be sending a cheque in GBP drawn on a major British bank). Thank you.

|

|

|

|

|

(please note that the

book shown is for illustrative purposes only and forms no part of this

auction)

Book dimensions are given in

inches, to the nearest quarter-inch, in the format width x height.

Please

note that, to differentiate them from soft-covers and paperbacks, modern

hardbacks are still invariably described as being ‘cloth’ when they are, in

fact, predominantly bound in paper-covered boards pressed to resemble cloth. |

|

|

|

|

Fine Books for Fine Minds |

I value your custom (and my

feedback rating) but I am also a bibliophile : I want books to arrive in the

same condition in which they were dispatched. For this reason, all books are

securely wrapped in tissue and a protective covering and are

then posted in a cardboard container. If any book is

significantly not as

described, I will offer a full refund. Unless the

size of the book precludes this, hardback books with a dust-jacket are

usually provided with a clear film protective cover, while

hardback books without a dust-jacket are usually provided with a rigid clear cover.

The Royal Mail, in my experience, offers an excellent service, but things

can occasionally go wrong.

However, I believe it is my responsibility to guarantee delivery.

If any book is lost or damaged in transit, I will offer a full refund.

Thank you for looking.

|

|

|

|

|

Please also

view my other listings for

a range of interesting books

and feel free to contact me if you require any additional information

Design and content © Geoffrey Miller |

|

|

|

|

|