GENERAL NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST - SIGNED AND NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION ART PRINT by MICHAEL GNATEK. Measures 16" x 21" and in mint condition with certificate of authenticity. Never framed. Limited to only 750 in the edition and sold out many years ago. Originally published in 1994 by renown artist Michael Gnatek. Insured Priority mail delivery in the continental US. Will ship worldwide and will combine shipping when practical. Will be shipped in a extra heavy duty tube that has to be purchased and not the cheap post office type that crushes easily.

Michael Gnatek, Jr. was long recognized as the premier portrait painter, both of American military and western figures. Born in Hadley, Massachusetts, he began his artistic career at the age of eleven. He attended Yale University’s School of Design, where he studied with noted abstract artist, Joseph Albers. Sadly, Mr. Gnatek passed away in Fall 2006.

Michael’s work was featured in Southwest Art, The Artist’s Magazine, and in the book, Contemporary Western Artists, by Peggy and Harold Samuels.

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821 – October 29, 1877) was a Confederate Army general during the American Civil War. Although scholars admire Forrest as a military strategist, he has remained a highly controversial figure in Southern racial history, especially for his alleged role in the massacre of black soldiers at Fort Pillow, his 1867–1869

Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealth as a cotton plantation owner, horse and cattle trader, real estate broker, and slave trader. In June 1861, he enlisted in the Confederate Army, one of the few officers during the war to enlist as a private and be promoted to general without any prior military training. An expert cavalry leader, Forrest was given command of a corps and established new doctrines for mobile forces, earning the nickname "The Wizard of the Saddle". His methods influenced many future generations of military strategists, although the Confederate high command is seen to have underutilized his talents.[citation needed]

In April 1864, in what has been called "one of the bleakest, saddest events of American military history.",[3] troops under Forrest's command massacred Union troops who had surrendered, most of them black soldiers along with some white Southern Tennesseans fighting for the Union, at the Battle of Fort Pillow. Forrest was blamed for the massacre in the Union press and that news may have strengthened the North's resolve.

In the last years of his life, and made at least one public speech (to a black audience) in favor of racial harmony. He and his wife moved onto President's Island in late 1875, established a home and started a business venture that relied on the Convict Lease System enacted in 1866 by the state of Mississippi, to secure a labor force of 117 convicts whose sentence would be served in clearing and cultivating 800 acres of the 1300 that Forrest had leased. "Among those convicts in his employ were eighteen black and four white female prisoners along with thirty-five white and sixty black male convicts who worked the land on Forrest's island plantation."[4]

Early life and career[edit]

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born on July 13, 1821 to a poor settler family in a secluded frontier cabin near Chapel Hill hamlet, then part of Bedford County, Tennessee, but now encompassed in Marshall County.[5][6] Forrest was the first son of William and Mariam (Beck) Forrest.[6] His father William was of English descent and most of his biographers state that his mother Mariam was of Scotch-Irish descent, but the Memphis Genealogical Society says that she was of English descent as well.[7] He and his twin sister, Fanny, were the two eldest of blacksmith William Forrest's 12 children with wife Miriam Beck. Forrest's great-grandfather, Shadrach Forrest, possibly of English birth, moved from Virginia to North Carolina, between 1730–1740, and there his son and grandson were born; they moved to Tennessee in 1806.[6] Forrest's family lived in a log house (now preserved as the Nathan Bedford Forrest Boyhood Home) from 1830 to 1833.[8] John Allan Wyeth, who served in an Alabama regiment under Forrest, described it as a one-room building with a loft and no windows.[9] William Forrest worked as a blacksmith in Tennessee until 1834, when he moved to Mississippi.[6] William died in 1837 and Forrest became the primary caretaker of the family at the age of sixteen.[6]

In 1841 Forrest went into business with his uncle Jonathan Forrest in Hernando, Mississippi. His uncle was killed there in 1845 during an argument with the Matlock brothers. In retaliation, Forrest shot and killed two of them with his two-shot pistol and wounded two others with a knife which had been thrown to him. One of the wounded Matlock men survived and served under Forrest during the Civil War.[10]

Forrest became a successful businessman, planter and slaveholder. He also acquired several cotton plantations in the Delta region of West Tennessee.[6] He was also a slave trader, at a time when demand was booming in the Deep South; his trading business was based on Adams Street in Memphis.[11][6] [12] In 1858, Forrest was elected a Memphis city alderman as a Democrat and served two consecutive terms.[13][14] By the time the American Civil War started in 1861, he had become one of the richest men in the South, having amassed a "personal fortune that he claimed was worth $1.5 million".[15]

Forrest was well known as a Memphis speculator and Mississippi gambler.[16] In 1859, he bought two large cotton plantations in Coahoma County, Mississippi and a half-interest in another plantation in Arkansas;[17] by October 1860 he owned at least 3,345 acres in Mississippi.[18]

Marriage, family and personal characteristics[edit]

Forrest had 12 brothers and sisters; two of his eight brothers and three of his four sisters died of typhoid fever at an early age, all at about the same time.[19][20] He also contracted the disease, but survived; his father recovered but died from residual effects of the disease five years later, when Bedford was 16. His mother Miriam then married James Horatio Luxton, of Marshall, Texas, in 1843 and gave birth to four more children.[21]

In 1845, Forrest married Mary Ann Montgomery (1826–1893), the niece of a Presbyterian minister who was her legal guardian.[22] They had two children, William Montgomery Bedford Forrest (1846–1908), who enlisted at the age of 15 and served alongside his father in the war, and a daughter, Fanny (1849–1854), who died in childhood. His descendants continued the military tradition. A grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest II (1872–1931), became commander-in-chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans[23]] A great-grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest III (1905–1943), graduated from West Point and rose to the rank of brigadier general in the U.S. Army Air Corps; he was killed during a bombing raid over Nazi Germany in 1943, becoming the first American general to die in European combat in World War II.[25]

Nathan Bedford Forrest was a tall man and had a commanding presence. Out of habit, he was mild mannered, quiet in speech, exemplary in language, considerate and generally kindhearted. Forrest rarely drank and he abstained from tobacco usage. When he was provoked or angered, however, he would become savage, profane and terrifying in appearance. Although he was not formally educated, Forrest was able to read and write in clear and grammatical English.[26]

American Civil War (1861–1865)[edit]

Early cavalry command[edit]

After the Civil War broke out, Forrest returned to Tennessee from his Mississippi ventures and enlisted in the Confederate States Army (CSA) on June 14, 1861. He reported for training at Fort Wright near Randolph, Tennessee,[27] joining Captain Josiah White's cavalry company, the Tennessee Mounted Rifles (Seventh Tennessee Cavalry), as a private along with his youngest brother and 15-year-old son. Upon seeing how badly equipped the CSA was, Forrest offered to buy horses and equipment with his own money for a regiment of Tennessee volunteer soldiers.[12][28]

His superior officers and Governor of Tennessee Isham G. Harris were surprised that someone of Forrest's wealth and prominence had enlisted as a soldier, especially since major planters were exempted from service. They commissioned him as a lieutenant colonel and authorized him to recruit and train a battalion of Confederate mounted rangers.[29] In October 1861, Forrest was given command of a regiment, the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry. Though Forrest had no prior formal military training or experience, he had exhibited leadership and soon proved he had a gift for successful tactics.[30][31]

Public debate surrounded Tennessee's decision to join the Confederacy and both the Confederate and Union armies recruited soldiers from the state. More than 100,000 men from Tennessee served with the Confederacy and over 31,000 served with the Union.[32] Forrest posted advertisements to join his regiment, with the slogan, "Let's have some fun and kill some Yankees!".[33] Forrest's command included his Escort Company (his "Special Forces"), for which he selected the best soldiers available. This unit, which varied in size from 40 to 90 men, constituted the elite of his cavalry.[34]

At six feet two inches (1.88 m) in height and about 180 pounds (13 st; 82 kg),[35][36][37][30] Forrest was physically imposing, especially compared to the average height of men at the time.[38] He used his skills as a hard rider and fierce swordsman to great effect; he was known to sharpen both the top and bottom edges of his heavy saber.[39] Forrest killed thirty enemy soldiers in hand-to hand combat.[40]

Sacramento and Fort Donelson[edit]

Forrest received praise for his skill and courage during an early victory in the Battle of Sacramento in Kentucky, the first in which he commanded troops in the field, where he routed a Union force by personally leading a cavalry charge that was later commended by his commander, Brigadier General Charles Clark.[41][42] Forrest distinguished himself further at the Battle of Fort Donelson in February 1862. After his cavalry captured a Union artillery battery, he broke out of a siege headed by Major General Ulysses S. Grant, rallying nearly 4,000 troops and leading them to escape across the Cumberland River.[43]

A few days after the Confederate surrender of Fort Donelson, with the fall of Nashville to Union forces imminent, Forrest took command of the city. All available carts and wagons were impressed into service to haul six hundred boxes of army clothing, 250,000 pounds of bacon and forty wagon-loads of ammunition to the railroad depots, to be sent off to Chattanooga and Decatur.[44][45] Forrest arranged for the heavy ordnance machinery, including a new cannon rifling machine and fourteen cannons built at Brennan's machine shop, as well as parts from the Nashville Armory, to be sent to Atlanta for use by the Confederate Army;[46] meanwhile the governor and legislature departed hastily for Memphis.[47][48]

Shiloh and Murfreesboro[edit]

A month later, Forrest was back in action at the Battle of Shiloh, fought April 6–7, 1862. He commanded a Confederate rear guard after the Union victory. In the battle of Fallen Timbers, he drove through the Union skirmish line. Not realizing that the rest of his men had halted their charge when reaching the full Union brigade, Forrest charged the brigade alone and soon found himself surrounded. He emptied his Colt Army revolvers into the swirling mass of Union soldiers and pulled out his saber, hacking and slashing. A Union infantryman on the ground beside Forrest fired a musket ball at him with a point-blank shot, nearly knocking him out of the saddle. The ball went through Forrest's pelvis and lodged near his spine. A surgeon removed the musket ball a week later, without anesthesia, which was unavailable.[19][49]

By early summer, Forrest commanded a new brigade of "green" cavalry regiments. In July, he led them into Middle Tennessee under orders to launch a cavalry raid, and on July 13, 1862, led them into the First Battle of Murfreesboro, as a result of which all of the Union units surrendered to Forrest, and the Confederates destroyed much of the Union's supplies and railroad track in the area.[50]

West Tennessee raids[edit]

Promoted on July 21, 1862 to brigadier general, Forrest was given command of a Confederate cavalry brigade.[51] In December 1862, Forrest's veteran troopers were reassigned by General Braxton Bragg to another officer, against his protest. Forrest had to recruit a new brigade, composed of about 2,000 inexperienced recruits, most of whom lacked weapons.[52] Again, Bragg ordered a series of raids, this time into west Tennessee, to disrupt the communications of the Union forces under Grant, which were threatening the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Forrest protested that to send such untrained men behind enemy lines was suicidal, but Bragg insisted, and Forrest obeyed his orders. In the ensuing raids he led thousands of Union soldiers in west Tennessee on a "wild goose chase" to try to locate his fast-moving forces. Never staying in one place long enough to be attacked, Forrest led his troops in raids as far north as the banks of the Ohio River in southwest Kentucky.[53] His destruction of railroads around Grant's headquarters at Holly Springs and his cutting down of telegraph lines slowed the implementation of Grant's notorious anti-semitic General Orders #11, which expelled Jewish cotton traders and their families from Grant's military district. Grant had blamed Jews for widespread cotton smuggling and speculation that affected his ability to fight the Confederate Army.[54]

Forrest returned to his base in Mississippi with more men than he had started with. By then, all were fully armed with captured Union weapons. As a result, Grant was forced to revise and delay the strategy of his Vicksburg campaign. Newspaper correspondent Sylvanus Cadwallader, who traveled with Grant for three years during his campaigns, wrote that Forrest "was the only Confederate cavalryman of whom Grant stood in much dread".[55][56]

Dover, Brentwood, and Chattanooga[edit]

The Union Army gained military control of Tennessee in 1862 and occupied it for the duration of the war, having taken control of strategic cities and railroads. Forrest continued to lead his men in small-scale operations, including the Battle of Dover and the Battle of Brentwood until April 1863. The Confederate army dispatched him with a small force into the backcountry of northern Alabama and western Georgia to defend against an attack of 3,000 Union cavalrymen commanded by Colonel Abel Streight. Streight had orders to cut the Confederate railroad south of Chattanooga, Tennessee to seal off Bragg's supply line and force him to retreat into Georgia.[57] Forrest chased Streight's men for 16 days, harassing them all the way. Streight's goal changed from dismantling the railroad to escaping the pursuit. On May 3, Forrest caught up with Streight's unit east of Cedar Bluff, Alabama. Forrest had fewer men than the Union side but feigned having a larger force by parading some repeatedly around a hilltop until Streight was convinced to surrender his 1,500 or so exhausted troops (historians Kevin Dougherty and Keith S. Hebert say he had about 1,700 men).[58][59][60]

Day's Gap, Chickamauga, and Paducah[edit]

Not all of Forrest's feats of individual combat involved enemy troops. Lieutenant Andrew Wills Gould, an artillery officer in Forrest's command, was being transferred, presumably because cannons under his command[61] were spiked (disabled) by the enemy[62] during the Battle of Day's Gap. On June 13, 1863, Gould confronted Forrest about his transfer, which escalated into a violent exchange.[63] Gould shot Forrest in the hip and Forrest mortally stabbed Gould.[4] Forrest was thought to have been fatally wounded by Gould but he recovered and was ready for the Chickamauga Campaign.[6]

Forrest served with the main army at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 18–20, 1863. He pursued the retreating Union army and took hundreds of prisoners.[64] Like several others under Bragg's command, he urged an immediate follow-up attack to recapture Chattanooga, which had fallen a few weeks before. Bragg failed to do so, upon which Forrest was quoted as saying, "What does he fight battles for?"[65][66] The story that Forrest confronted and threatened the life of Bragg in the fall of 1863, following the battle of Chickamauga, and that Bragg transferred Forrest to command in Mississippi as a direct result, is now considered to be apocryphal.[67][68][69]

On December 4, 1863, Forrest was promoted to the rank of major general.[70] On March 25, 1864, Forrest's cavalry raided the town of Paducah, Kentucky in the Battle of Paducah, during which Forrest demanded the surrender of U.S. Colonel Stephen G. Hicks: "... if I have to storm your works, you may expect no quarter." The bluff failed and Hicks refused.[71][72][73]

Fort Pillow massacre[edit]

Fort Pillow, located 40 miles up river from Memphis (Henning), was originally constructed by Confederate general Gideon Johnson Pillow, on the bluffs of the Mississippi River, later taken over by Union forces in 1862, after the Confederates had abandoned the fort.[74] The fort was manned by 557 Union troops, 295 white and 262 black, under Union commander Maj. L.F. Booth.[74]

On the early morning of April 12, 1864, Forrest's men, under Brig. Gen. James Chalmers, attacked and recaptured Fort Pillow.[74] Booth and his adjutant were killed in battle, leaving Fort Pillow under the command of Major William Bradford. [74] At 10:00 Forrest reached the fort after a hard ride from Mississippi. [74] Not shy of action, Forrest rode up to the battle, his horse was shot out from under him and he fell to the ground. Undaunted, Forrest mounted a second horse, which was shot out from under him as well, forcing him to mount a third horse.[74] By 3:30 pm, Forrest concluded the Fort could not be held anymore and ordered a flag of truce and that the fort be surrendered. [75] Bradford refused to surrender, believing his troops could escape to the Union gunboat, USS New Era, on the Mississippi River. [75] Forrest's men immediately took over the fort, while Union soldiers retreated to the lower bluffs of the river, but the USS New Era did not come to their rescue. [75] What happened next became known as the Fort Pillow Massacre[76] As the Union troops surrendered, Forrest's men opened fire, slaughtering both black and white soldiers. [76][77][78] White soldiers were killed at a rate of 31 percent, while black troops had a casualty rate of 64 percent.[79][80] The atrocities at Fort Pillow continued throughout the night. Conflicting accounts of what actually occurred were given later.[81][82][83]

Forrest's Confederate forces were accused of subjecting Union captured soldiers to extreme brutality, with allegations of back-shooting soldiers who fled into the river, shooting wounded soldiers, burning men alive, nailing men to barrels and igniting them, crucifixion and hacking men to death with sabers.[84] Forrest's men were alleged to have set fire to a Union barracks with wounded Union soldiers inside[85][86] In defense of their actions, Forrest's men insisted that the Union soldiers, although fleeing, kept their weapons and frequently turned to shoot, forcing the Confederates to keep firing in self-defense.[87] The rebels said the Union flag was still flying over the fort, which indicated that the force had not formally surrendered. A contemporary newspaper account from Jackson, Tennessee stated that "General Forrest begged them to surrender" but "not the first sign of surrender was ever given". Similar accounts were reported in many Southern newspapers at the time.[88] These statements, however, were contradicted by Union survivors, as well as by the letter of a Confederate soldier who graphically recounted a massacre. Achilles Clark, a soldier with the 20th Tennessee cavalry, wrote to his sisters immediately after the battle:

The slaughter was awful. Words cannot describe the scene. The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down. The white men fared but little better. Their fort turned out to be a great slaughter pen. Blood, human blood stood about in pools and brains could have been gathered up in any quantity.[89][90][91]

Following the cessation of hostilities, Forrest transferred the 14 most seriously wounded United States Colored Troops (USCT) to the U.S. steamer Silver Cloud.[92] The 226 Union troops taken prisoner at Fort Pillow were marched under guard to Holly Springs, Mississippi and then convoyed to Demopolis, Alabama. On April 21, Capt. John Goodwin, of Forrest's cavalry command, forwarded a dispatch listing the prisoners captured. The list included the names of 7 officers and 219 white enlisted soldiers. According to Richard L. Fuchs, records concerning the black prisoners are "nonexistent or unreliable."[93] President Abraham Lincoln asked his cabinet for opinions as to how the Union should respond to the massacre.[94]

At the time of the massacre, General Grant was no longer in Tennessee but had transferred to the east to command all Union troops. He wrote in his memoirs that Forrest in his report of the battle had "left out the part which shocks humanity to read."[95]

The Northern public and press viewed Forrest as a butcher and a war criminal over Fort Pillow.[96] The Chicago Tribune said Forrest and his brothers were "slave drivers and woman whippers", while Forrest himself was described as a tall, snake-eyed man, who was "mean, vindictive, cruel, and unscrupulous."[96]The Southern press steadfastly defended Forrest's reputation.[97][98]

Brice's Crossroads and Tupelo[edit]

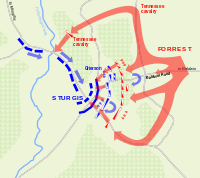

Forrest's greatest victory came on June 10, 1864, when his 3,500-man force clashed with 8,500 men commanded by Union Brig. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis at the Battle of Brice's Crossroads in northeastern Mississippi.[99] Here, the mobility of the troops under his command and his superior tactics led to victory,[100][101] allowing him to continue harassing Union forces in southwestern Tennessee and northern Mississippi throughout the war.[102] Forrest set up a position for an attack to repulse a pursuing force commanded by Sturgis, who had been sent to impede Forrest from destroying Union supply lines and fortifications.[103] When Sturgis's Federal army came upon the crossroads, they collided with Forrest's cavalry.[104] Sturgis ordered his infantry to advance to the front line to counteract the cavalry. The infantry, tired, weary and suffering under the heat, were quickly broken and sent into mass retreat. Forrest sent a full charge after the retreating army and captured 16 artillery pieces, 176 wagons and 1,500 stands of small arms. In all, the maneuver cost Forrest 96 men killed and 396 wounded. The day was worse for Union troops, which suffered 223 killed, 394 wounded and 1,623 missing. The losses were a deep blow to the black regiment under Sturgis's command. In the hasty retreat, they stripped off commemorative badges that read "Remember Fort Pillow" to avoid goading the Confederate force pursuing them.[105]

One month later, while serving under General Stephen D. Lee, Forrest experienced tactical defeat at the Battle of Tupelo in 1864.[106] Concerned about Union supply lines, Maj. Gen. Sherman sent a force under the command of Maj. Gen. Andrew J. Smith to deal with Forrest.[107] Union forces drove the Confederates from the field and Forrest was wounded in the foot, but his forces were not wholly destroyed.[108] He continued to oppose Union efforts in the West for the remainder of the war.

Tennessee Raids[edit]

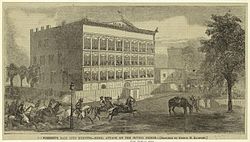

Forrest led other raids that summer and fall, including a famous one into Union-held downtown Memphis in August 1864 (the Second Battle of Memphis)[108] and another on a major Union supply depot at Johnsonville, Tennessee. On November 4, 1864, during the Battle of Johnsonville, the Confederates shelled the city, sinking three gunboats and nearly thirty other ships and destroying many tons of supplies.[109] During Hood's Tennessee Campaign, he fought alongside General John Bell Hood, the newest (and last) commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, in the Second Battle of Franklin on November 30.[110] Facing a disastrous defeat, Forrest argued bitterly with Hood (his superior officer) demanding permission to cross the Harpeth River and cut off the escape route of Union Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield's army.[111] He eventually made the attempt, but it was too late.

Murfreesboro, Nashville, and Selma[edit]

After his bloody defeat at Franklin, Hood continued on to Nashville. Hood ordered Forrest to conduct an independent raid against the Murfreesboro garrison. After success in achieving the objectives specified by Hood, Forrest engaged Union forces near Murfreesboro on December 5, 1864. In what would be known as the Third Battle of Murfreesboro, a portion of Forrest's command broke and ran.[112] When Hood's battle-hardened Army of Tennessee, consisting of 40,000 men deployed in three infantry corps plus 10,000 to 15,000 cavalry, was all but destroyed on December 15–16, at the Battle of Nashville,[113] Forrest distinguished himself by commanding the Confederate rear guard in a series of actions that allowed what was left of the army to escape. For this, he would later be promoted to the rank of lieutenant general on March 2, 1865.[114] A portion of his command, now dismounted, was surprised and captured in their camp at Verona, Mississippi on December 25, 1864, during a raid of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad by a brigade of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson's cavalry division.[115]

In the spring of 1865, Forrest led an unsuccessful defense of the state of Alabama against Wilson's Raid. His opponent, Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, defeated Forrest at the Battle of Selma on April 2, 1865.[116] A week later, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant in Virginia. When he received news of Lee's surrender, Forrest also chose to surrender. On May 9, 1865, at Gainesville, Forrest read his farewell address to the men under his command, enjoining them to "submit to the powers to be, and to aid in restoring peace and establishing law and order throughout the land."[117]

Postwar years and later life[edit]

Business ventures[edit]

With slavery abolished after the war, Forrest suffered a major financial setback as a former slave trader. He became interested in the area around Crowley's Ridge during the war and settled in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1866, Forrest and C.C. McCreanor contracted to finish the Memphis & Little Rock Railroad.[118] The commissary he built as a provisioning store for the 1,000 Irish laborers hired to lay the rails became the nucleus of a town, which most residents called "Forrest's Town" and which was incorporated as Forrest City, Arkansas in 1870.[119]

The historian Court Carney writes that Forrest was not universally popular in the white Memphis community: he alienated many of the city's businessmen in his commercial dealings and he was criticized for questionable business practices that caused him to default on debts.[120]

He later found employment at the Selma-based Marion & Memphis Railroad and eventually became the company president. He was not as successful in railroad promoting as in war and, under his direction, the company went bankrupt. Nearly ruined as the result of this failure, Forrest spent his final days running an eight-hundred acre farm on land he leased on President's Island in the Mississippi River, where he and his wife lived in a log cabin. There, with the labor of over a hundred prison convicts, he grew corn, potatoes, vegetables and cotton profitably, but his health was in steady decline.[121][122]

Offers services to Sherman[edit]

During the Virginius Affair of 1873, some of Forrest's old Southern friends were filibusters aboard the vessel so he wrote a letter to then General-in-Chief of the United States Army William T. Sherman and offered his services in case of war with Spain. Sherman, who in the Civil War had recognized what a deadly foe Forrest was, replied after the crisis settled down. He thanked Forrest for the offer and stated that had war broken out, he would have considered it an honor to have served side-by-side with him.[123][124][125][126][127][128][129][130]

The Republicans had nominated one of Forrest's battle adversaries, Union war hero Ulysses S. Grant, for the Presidency at their convention held in October. Grant defeated Horatio Seymour, the Democratic presidential candidate, by a comfortable electoral margin, 214 to 80.[167] The popular vote was much closer, as Grant received 3,013,365 (52.7%) votes, while Seymour received 2,708,744 (47.3%) votes.[167] Grant lost Georgia and Louisiana, where the violence and intimidation against blacks was most prominent.

Speech to black Southerners (1875)[edit]

On July 5, 1875, Forrest demonstrated that his personal sentiments on the issue of race now differed from those of the when he was invited to give a speech before the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers Association, a post-war organization of black Southerners advocating to improve the economic condition of blacks and to gain equal rights for all citizens. At this, his last public appearance, he made what The New York Times described as a "friendly speech"[171][172] during which, when offered a bouquet of flowers by a young black woman, he accepted them,[173] thanked her and kissed her on the cheek as a token of reconciliation between the races. Forrest ignored his critics and spoke in encouragement of black advancement and of endeavoring to be a proponent for espousing peace and harmony between black and white Americans.[174]

In response to the Pole-Bearers speech, the Cavalry Survivors Association of Augusta, the first Confederate organization formed after the war, called a meeting in which Captain F. Edgeworth Eve gave a speech expressing unmitigated disapproval of Forrest's remarks promoting inter-ethnic harmony, ridiculing his faculties and judgment and berating the woman who gave Forrest flowers as "a mulatto wench". The association voted unanimously to amend its constitution to expressly forbid publicly advocating for or hinting at any association of white women and girls as being in the same classes as "females of the negro race".[175][176] The Macon Weekly Telegraph newspaper also condemned Forrest for his speech, describing the event as "the recent disgusting exhibition of himself at the negro [sic] jamboree" and quoting part of a Charlotte Observer article, which read "We have infinitely more respect for Longstreet, who fraternizes with negro men on public occasions, with the pay for the treason to his race in his pocket, than with Forrest and [General] Pillow, who equalize with the negro women, with only 'futures' in payment".[177][178]

Death[edit]

Forrest reportedly died from acute complications of diabetes at the Memphis home of his brother Jesse on October 29, 1877.[179] His eulogy was delivered by his recent spiritual mentor, former Confederate chaplain George Tucker Stainback, who declared in his eulogy: "Lieutenant-General Nathan Bedford Forrest, though dead, yet speaketh. His acts have photographed themselves upon the hearts of thousands, and will speak there forever.[180]

Forrest was buried at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis.[181] In 1904, the remains of Forrest and his wife Mary were disinterred from Elmwood and moved to a Memphis city park that was originally named Forrest Park in his honor, but has since been renamed Health Sciences Park.[182]

On July 7, 2015, the Memphis City Council unanimously voted to remove the statue of Forrest from Health Sciences Park, and to return the remains of Forrest and his wife to Elmwood Cemetery.[183] However, on October 13, 2017, the Tennessee Historical Commission invoked the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act of 2013 and U.S. Public Law 85-425: Sec. 410 to overrule the city.[184] Consequently, Memphis sold the park land to a non-profit entity not subject to the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act (Memphis Greenspace), which immediately removed the monument as explained below.

Historical reputation and legacy[edit]

Many memorials have been erected to Forrest, especially in Tennessee and adjacent Southern states. Forrest County, Mississippi is named after him, as is Forrest City, Arkansas. Obelisks in his memory were placed at his birthplace in Chapel Hill, Tennessee and at Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park near Camden.[185]

Forrest was elevated in Memphis in particular—where he lived and died—to the status of folk hero. "Embarrassed by their city's early capitulation during the Civil War, white Memphians desperately needed a hero and therefore crafted a distorted depiction of Forrest's role in the war."[186] A memorial to him, the first Civil War memorial in Memphis, was erected in 1905 in a new Nathan Bedford Forrest Park. A bust sculpted by Jane Baxendale is on display at the Tennessee State Capitol building in Nashville.[187] The World War II Army base Camp Forrest in Tullahoma, Tennessee was named after him.[188] It is now the site of the Arnold Engineering Development Center.[189]

As of 2007[update], Tennessee had 32 dedicated historical markers linked to Nathan Bedford Forrest, more than are dedicated to all three former Presidents associated with the state combined: Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson (none of whom were born in Tennessee).[190] The Tennessee legislature established July 13 as "Nathan Bedford Forrest Day".[191] A Tennessee-based organization, the Sons of Confederate Veterans, posthumously awarded Forrest their Confederate Medal of Honor, created in 1977.[192]

A monument to Forrest in the Confederate Circle section of Old Live Oak Cemetery in Selma, Alabama reads "Defender of Selma, Wizard of the Saddle, Untutored Genius, The first with the most. This monument stands as testament of our perpetual devotion and respect for Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest. CSA 1821–1877, one of the South's finest heroes. In honor of Gen. Forrest's unwavering defense of Selma, the great state of Alabama, and the Confederacy, this memorial is dedicated. DEO VINDICE".[193] As an armory for the Confederacy, Selma provided a substantial part of the South's ammunition during the Civil War.[194] The bust of Forrest was stolen from the cemetery monument in March 2012 and replaced in May 2015.[195][196] A monument to Forrest at a corner of Veterans Plaza in Rome, Georgia was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1909 to honor his bravery for saving Rome from Union Army Colonel Abel Streight and his cavalry.[197]

High schools named for Forrest were built in Chapel Hill, Tennessee and Jacksonville, Florida. In 2008, the Duval County School Board voted 5–2 against a push to change the name of Nathan Bedford Forrest High School in Jacksonville.[198] In 2013, the board voted 7–0 to begin the process to rename the school.[198] The school was named for Forrest in 1959 at the urging of the Daughters of the Confederacy because they were upset about the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. At the time the school was all white, but now more than half the student body is black.[199] After several public forums and discussions, Westside High School was unanimously approved in January 2014 as the school's new name.

In August 2000, a road on Fort Bliss named for Forrest decades earlier was renamed for former post commander Richard T. Cassidy.[200][201][202] In 2005, Shelby County Commissioner Walter Bailey started an effort to move the statue over Forrest's grave and rename Forrest Park. Former Memphis Mayor Willie Herenton, who is black, blocked the move. Others have tried to get a bust of Forrest removed from the Tennessee House of Representatives chamber.[203] Leaders in other localities have also tried to remove or eliminate Forrest monuments, with mixed success.

In 1978, Middle Tennessee State University abandoned imagery it had formerly used (in 1951, the school's yearbook, The Midlander, featured the first appearance of Forrest's likeness as MTSU's official mascot) and MTSU president M.G Scarlett removed the General's image from the university's official seal. The Blue Raiders' athletic mascot was changed to an ambiguous swash-buckler character called the "Blue Raider", to avoid association with Forrest or the Confederacy. The school unveiled its latest mascot, a winged horse called "Lightning" inspired by the mythological Pegasus, during halftime of a basketball game against rival Tennessee State University on January 17, 1998.[204] The ROTC building at MTSU was named Forrest Hall to honor him in 1958. In 2006, the frieze depicting General Forrest on horseback that had adorned the side of this building was removed amid protests,[205] but a major push to change its name failed on February 16, 2018, when the governor-controlled Tennessee Historical Commission denied Middle Tennessee State University's petition to rename Forrest Hall.[206]

Great-grandson Nathan Bedford Forrest III first pursued a military career in cavalry, then in aviation attained the rank of brigadier general in the United States Army Air Forces where he became the first U.S. general to be killed in action in World War II, while participating in a June 13, 1943 bombing raid over Germany.[25] His family received the Distinguished Service Cross (second only to the Medal of Honor) he was awarded posthumously for staying with the controls of his B-17 bomber while his crew bailed out.[207]

Military doctrines[edit]

Forrest is considered one of the Civil War's most brilliant tacticians by the historian Spencer C. Tucker.[208] Forrest fought by simple rules: he maintained, "war means fighting and fighting means killing" and the way to win was "to get there first with the most men".[209] Union General William Tecumseh Sherman called him "that devil Forrest" in wartime communications with Ulysses S. Grant and considered him "the most remarkable man our civil war produced on either side".[210][211][212]

Forrest became well known for his early use of maneuver tactics as applied to a mobile horse cavalry deployment.[213] He grasped the doctrines of mobile warfare[214] that would eventually become prevalent in the 20th century. Paramount in his strategy was fast movement, even if it meant pushing his horses at a killing pace, to constantly harass his enemy during raids and disrupt supply trains and enemy communications by destroying railroad tracks and cutting telegraph lines, as he wheeled around his opponent's flank. Noted Civil War scholar Bruce Catton writes:

Forrest ... used his horsemen as a modern general would use motorized infantry. He liked horses because he liked fast movement, and his mounted men could get from here to there much faster than any infantry could; but when they reached the field they usually tied their horses to trees and fought on foot, and they were as good as the very best infantry.[215]

Forrest is often erroneously quoted as saying his strategy was to "git thar fustest with the mostest". Now often recast as "Getting there firstest with the mostest",[216] this misquote first appeared in a New York Tribune article written to provide colorful comments in reaction to European interest in Civil War generals. The aphorism was addressed and corrected as "Ma'am, I got there first with the most men" by a New York Times story in 1918.[217] Though it was a novel and succinct condensation of the military principles of mass and maneuver, Bruce Catton writes of the spurious quote:

Do not, under any circumstances whatever, quote Forrest as saying 'fustest' and 'mostest'. He did not say it that way, and nobody who knows anything about him imagines that he did.[218]

War record and promotions[edit]

- Enlisted as Private July 1861. (White's Company "E", Tennessee Mounted Rifles)

- Commissioned as lieutenant colonel, October 1861 (3rd Tennessee Cavalry)

- Promoted to colonel, February 1862

- Battle of Fort Donelson, February 12–16, 1862

- Wounded at Battle of Shiloh, April 6–8, 1862

- Promoted to brigadier general, July 21, 1862

- First Battle of Murfreesboro, July 1862

- Raids in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi, Early December 1862 – Early January 1863

- Battle of Day's Gap, April 30 – May 2, 1863

- Assigned to command Forrest's Cavalry Corps, May 1863

- Battle of Chickamauga, September 18–20, 1863

- Promoted to major general, December 4, 1863

- Battle of Paducah, March 25, 1864

- Battle of Fort Pillow, April 12, 1864

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads, June 10, 1864

- Battle of Tupelo, July 14–15, 1864

- Raids in Tennessee, August–October 1864

- Battle of Spring Hill, November 29, 1864

- Battle of Franklin, November 30, 1864

- Third Battle of Murfreesboro, December 5–7, 1864

- Battle of Nashville, December 15–16, 1864

- Promoted to lieutenant general, February 28, 1865[51]

- Battle of Selma, April 2, 1865

- Farewell address to his troops, May 9, 1865

Fort Pillow controversy[edit]

Modern historians generally believe that Forrest's attack on Fort Pillow was a massacre, noting high casualty rates, and the rebels targeting black soldiers.[219] It was the South's publicly stated position that slaves firing on whites would be killed on the spot, along with Southern whites that fought for the Union, whom the Confederacy considered traitors.[220] According to this analysis, Forrest's troops were carrying out Confederate policy. By his inaction Forrest showed that he felt no compunction to stop the slaughter. His repeated denials that he never knew a massacre was taking place, or even that a massacre had occurred at all, are not credible. Consequently his role at Fort Pillow was a stigmatizing one for him the rest of his life, both professionally and personally,[221][222] and contributed to his business problems after the war.

After Forrest's death, The New York Times reported that "General Bedford Forrest, the great Confederate cavalry officer, died at 7:30 o'clock this evening at the residence of his brother, Colonel Jesse Forrest," but also reported that it would not be for military victories that Forrest would pass into history, i.e., he would be most remembered for Fort Pillow.[223] Forrest's claim that the Fort Pillow massacre was an invention of Northern reporters is contradicted by letters written by Confederate soldiers to their own families, which described wanton brutality on the part of Confederate troops.[91] The New York newspaper obituary stated:

Since the war, Forrest has lived at Memphis, and his principal occupation seems to have been to try and explain away the Fort Pillow affair. He wrote several letters about it, which were published, and always had something to say about it in any public speech he delivered. He seemed as if he were trying always to rub away the blood stains which marked him.[223]

Historians have differed in their interpretations of the events at Fort Pillow. Richard L. Fuchs, author of An Unerring Fire, concluded:

The affair at Fort Pillow was simply an orgy of death, a mass lynching to satisfy the basest of conduct—intentional murder—for the vilest of reasons—racism and personal enmity.[224]

Andrew Ward downplays the controversy:

Whether the massacre was premeditated or spontaneous does not address the more fundamental question of whether a massacre took place ... it certainly did, in every dictionary sense of the word.[225]

John Cimprich states:

The new paradigm in social attitudes and the fuller use of available evidence has favored a massacre interpretation ... Debate over the memory of this incident formed a part of sectional and racial conflicts for many years after the war, but the reinterpretation of the event during the last thirty years offers some hope that society can move beyond past intolerance.[226]

The site is now a Tennessee State Historic Park.[227]

Grant himself described Forrest as "a brave and intrepid cavalry general" while noting that Forrest sent a dispatch on the Fort Pillow Massacre "in which he left out the part which shocks humanity to read."[228]

In popular culture[edit]

In the 1990 PBS documentary The Civil War by Ken Burns, historian Shelby Foote states in Episode 7 that the Civil War produced two "authentic geniuses": Abraham Lincoln and Nathan Bedford Forrest. When expressing this opinion to one of General Forrest's granddaughters, she replied after a pause, "You know, we never thought much of Mr. Lincoln in my family".[229] Foote also made Forrest a major character in his novel Shiloh, which used numerous first-person stories to illustrate a detailed timeline and account of the battle.[230][231]

The Battle of Fort Donelson was fought from February 11–16, 1862, in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. The Union capture of the Confederate fort near the Tennessee–Kentucky border opened the Cumberland River, an important avenue for the invasion of the South. The Union's success also elevated Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant from an obscure and largely unproven leader to the rank of major general, and earned him the nickname of "Unconditional Surrender" Grant.

Grant moved his army (later to become the Union's Army of the Tennessee[4]) 12 miles (19 km) overland to Fort Donelson, from February 11 to 13, and conducted several small probing attacks. On February 14, Union gunboats under Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote attempted to reduce the fort with gunfire, but were forced to withdraw after sustaining heavy damage from the fort's water batteries.

On February 15, with the fort surrounded, the Confederates, commanded by Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd, launched a surprise attack, led by his second-in-command, Brig. Gen. Gideon Johnson Pillow, against the right flank of Grant's army. The intention was to open an escape route for retreat to Nashville, Tennessee. Grant was away from the battlefield at the start of the attack, but arrived to rally his men and counterattack. Pillow's attack succeeded in opening the route, but Floyd lost his nerve and ordered his men back to the fort. The following morning, Floyd and Pillow escaped with a small detachment of troops, relinquishing command to Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, who accepted Grant's demand of unconditional surrender later that day. The battle resulted in virtually all of Kentucky as well as much of Tennessee, including Nashville, falling under Union control.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Military situation

2 Opposing forces

2.1 Union

2.2 Confederate

3 Battle

3.1 Preliminary movements and attacks (February 12–13)

3.2 Reinforcements and naval battle (February 14)

3.3 Breakout attempt (February 15)

4 Surrender (February 16)

5 Aftermath

6 Battlefield preservation

7 See also

8 Notes

9 Bibliography

9.1 Memoirs and primary sources

10 Further reading

11 External links

Background

Military situation

Main article: Battle of Fort Henry

Further information: Western Theater of the American Civil War and American Civil War

Kentucky-Tennessee, 1862

Battle of Fort Henry and the movements to Fort Donelson

Confederate

Union

The battle of Fort Donelson, which began on February 12, took place shortly after the surrender of Fort Henry, Tennessee, on February 6, 1862. Fort Henry had been a key position in the center of a line defending Tennessee, and the capture of the fort now opened the Tennessee River to Union troop and supply movements. About 2,500 of Fort Henry's Confederate defenders escaped before its surrender by marching the 12 miles (19 km) east to Fort Donelson.[5] In the days following the surrender at Fort Henry, Union troops cut the railroad lines south of the fort, restricting the Confederates' lateral mobility to move reinforcements into the area to defend against the larger Union forces.[6]

With the surrender of Fort Henry, the Confederates faced some difficult choices. Grant's army now divided Confederate Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston's two main forces: P.G.T. Beauregard at Columbus, Kentucky, with 12,000 men, and William J. Hardee at Bowling Green, Kentucky, with 22,000 men. Fort Donelson had only about 5,000 men. Union forces might attack Columbus; they might attack Fort Donelson and thereby threaten Nashville, Tennessee; or Grant and Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, who was quartered in Louisville with 45,000 men, might attack Johnston head-on, with Grant following behind Buell. Johnston was apprehensive about the ease with which Union gunboats defeated Fort Henry (not comprehending that the rising waters of the Tennessee River played a crucial role by inundating the fort). He was more concerned about the threat from Buell than he was from Grant, and suspected the river operations might simply be a diversion.[6]

Johnston decided upon a course of action that forfeited the initiative across most of his defensive line, tacitly admitting that the Confederate defensive strategy for Tennessee was a sham. On February 7, at a council of war held in the Covington Hotel at Bowling Green, he decided to abandon western Kentucky by withdrawing Beauregard from Columbus, evacuating Bowling Green, and moving his forces south of the Cumberland River at Nashville. Despite his misgivings about its defensibility, Johnston agreed to Beauregard's advice that he should reinforce Fort Donelson with another 12,000 men, knowing that a defeat there would mean the inevitable loss of Middle Tennessee and the vital manufacturing and arsenal city of Nashville.[7]

Johnston wanted to give command of Fort Donelson to Beauregard, who had performed ably at Bull Run, but the latter declined because of a throat ailment. Instead, the responsibility went to Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd, who had just arrived following an unsuccessful assignment under Robert E. Lee in western Virginia. Floyd was a wanted man in the North for alleged graft and secessionist activities when he was Secretary of War in the James Buchanan administration. Floyd's background was political, not military, but he was nevertheless the senior brigadier general on the Cumberland River.[8]

On the Union side, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, Grant's superior as commander of the Department of the Missouri, was also apprehensive. Halleck had authorized Grant to capture Fort Henry, but now he felt that continuing to Fort Donelson was risky. Despite Grant's success to date, Halleck had little confidence in him, considering Grant to be reckless. Halleck attempted to convince his own rival, Don Carlos Buell, to take command of the campaign to get his additional forces engaged. Despite Johnston's high regard for Buell, the Union general was as passive as Grant was aggressive. Grant never suspected his superiors were considering relieving him, but he was well aware that any delay or reversal might be an opportunity for Halleck to lose his nerve and cancel the operation.[9]

On February 6, Grant wired Halleck: "Fort Henry is ours. ... I shall take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th and return to Fort Henry."[10] This self-imposed deadline was overly optimistic due to three factors: miserable road conditions on the twelve-mile march to Donelson, the need for troops to carry supplies away from the rising flood waters (by February 8, Fort Henry was completely submerged),[11] and the damage that had been sustained by Foote's Western Gunboat Flotilla in the artillery duel at Fort Henry. If Grant had been able to move quickly, he might have taken Fort Donelson on February 8. Early in the morning of February 11, Grant held a council of war in which all of his generals supported his plans for an attack on Fort Donelson, with the exception of Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand, who had some reservations. This council in early 1862 was the last one that Grant held for the remainder of the Civil War.[12]

Opposing forces

Union

Further information: Union order of battle

Union commanders

Maj. Gen.

Henry W. Halleck

Brig. Gen.

Ulysses S. Grant

Flag Officer

Andrew H. Foote

Brig. Gen.

John A. McClernand

Brig. Gen.

Charles F. Smith

Brig. Gen.

Lew Wallace

Grant's Union Army of the Tennessee of the District of Cairo consisted of three divisions, commanded by Brig. Gens. McClernand, C.F. Smith, and Lew Wallace. (At the start of the attack on Fort Donelson, Wallace was a brigade commander in reserve at Fort Henry, but was summoned on February 14 and charged with assembling a new division that included reinforcements arriving by steamship, including Charles Cruft's brigade on loan from Buell.) Two regiments of cavalry and eight batteries of artillery supported the infantry divisions. Altogether, the Union forces numbered nearly 25,000 men, although at the start of the battle, only 15,000 were available.[13]

The Western Gunboat Flotilla under Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote consisted of four ironclad gunboats (flagship USS St. Louis, USS Carondelet, USS Louisville, and USS Pittsburg) and three timberclad (wooden) gunboats (USS Conestoga, USS Tyler, and USS Lexington). USS Essex and USS Cincinnati had been damaged at Fort Henry and were being repaired.[14]

Confederate

Further information: Confederate order of battle

Confederate commanders

Gen.

Albert Sidney Johnston

Brig. Gen.

John B. Floyd

Brig. Gen.

Gideon J. Pillow

Brig. Gen.

Simon Bolivar Buckner

Brig. Gen.

Bushrod Johnson

Lt. Col.

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Floyd's Confederate force of approximately 17,000 men consisted of three divisions (Army of Central Kentucky), garrison troops, and attached cavalry. The three divisions were commanded by Floyd (replaced by Colonel Gabriel C. Wharton when Floyd took command of the entire force) and Brig. Gens. Bushrod Johnson and Simon Bolivar Buckner. During the battle, Johnson, the engineering officer who briefly commanded Fort Donelson in late January, was effectively superseded by Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow (Grant's opponent at his first battle at Belmont). Pillow, who arrived at Fort Donelson on February 9, was displaced from overall command of the fort when the more-senior Floyd arrived.[15] The garrison troops were commanded by Col. John W. Head and the cavalry by Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest.[16]

Fort Donelson was named for Brig. Gen. Daniel S. Donelson, who selected its site and began construction in 1861. It was considerably more formidable than Fort Henry. Fort Donelson rose about 100 feet (30 m) on approximately 100 acres of dry ground above the Cumberland River, which allowed for plunging fire against attacking gunboats, an advantage Fort Henry did not enjoy.[17] The river batteries included twelve guns: ten 32-pounder smoothbore cannons, two 9-pounder smoothbore cannons, an 8-inch howitzer, a 6.5-inch rifle (128-pounder), and a 10-inch Columbiad. There were three miles (5 km) of trenches in a semicircle around the fort and the small town of Dover. The outer works were bounded by Hickman Creek to the west, Lick Creek to the east, and the Cumberland River to the north. These trenches, located on a commanding ridge and fronted by a dense abatis of cut trees and limbs stuck into the ground and pointing outward,[17] were backed up by artillery and manned by Buckner and his Bowling Green troops on the right (with his flank anchored on Hickman Creek), and Johnson/Pillow on the left (with his flank near the Cumberland River). Facing the Confederates, from left to right, were Smith, Lew Wallace (who arrived on February 14), and McClernand. McClernand's right flank, which faced Pillow, had insufficient men to reach overflowing Lick Creek, so it was left unanchored. Through the center of the Confederate line ran the marshy Indian Creek, this point defended primarily by artillery overlooking it on each side.[18]

Battle

Preliminary movements and attacks (February 12–13)

Positions on the evening of February 14, 1862

On February 12, most of the Union troops departed Fort Henry, where they were waiting for the return of Union gunboats and the arrival of additional troops that would increase the Union forces to about 25,000 men.[15] The Union forces proceeded about 5 miles (8 km) on the two main roads leading between the two forts. They were delayed most of the day by a cavalry screen commanded by Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest's troops, sent out by Buckner, spotted a detachment from McClernand's division and opened fire against them. A brief skirmish ensued until orders from Buckner arrived to fall back within the entrenchments. After this withdrawal of Forrest's cavalry, the Union troops moved closer to the Confederate defense line while trying to cover any possible Confederate escape routes. McClernand's division made up the right of Grant's army with C.F. Smith's division forming the left.[19] USS Carondelet was the first gunboat to arrive up the river, and she promptly fired numerous shells into the fort, testing its defenses before retiring. Grant arrived on February 12 and established his headquarters near the left side of the front of the line, at the Widow Crisp's house.[20]

On February 11, Buckner relayed orders to Pillow from Floyd to release Floyd's and Buckner's troops to operate south of the river, near Cumberland City, where they would be able to attack the Union supply lines while keeping a clear path back to Nashville. However, this would leave the Confederate forces at Fort Donelson heavily outnumbered. Pillow left early on the morning of February 12 to argue these orders with General Floyd himself leaving Buckner in charge of the fort. After hearing sounds of artillery fire, Pillow returned to Fort Donelson to resume command. After the events of the day, Buckner remained at Fort Donelson to command the Confederate right. With the arrival of Grant's army, General Johnston ordered Floyd to take any troops remaining in Clarksville to aid in the defense of Fort Donelson.[21]

On February 13, several small probing attacks were carried out against the Confederate defenses, essentially ignoring orders from Grant that no general engagement be provoked. On the Union left, C. F. Smith sent two of his four brigades (under Cols. Jacob Lauman and John Cook) to test the defenses along his front. The attack suffered light casualties and made no gains, but Smith was able to keep up a harassing fire throughout the night. On the right, McClernand also ordered an unauthorized attack. Two regiments of Col. William R. Morrison's brigade, along with one regiment, the 48th Illinois, from Col. W.H.L. Wallace's brigade, were ordered to seize a battery ("Redan Number 2") that had been plaguing their position. Isham N. Haynie, colonel of the 48th Illinois, was senior in rank to Colonel Morrison. Although rightfully in command of two of the three regiments, Morrison volunteered to turn over command once the attack was under way; however, when the attack began, Morrison was wounded, eliminating any leadership ambiguity. For unknown reasons Haynie never fully took control and the attack was repulsed. Some wounded men caught between the lines burned to death in grass fires ignited by the artillery.[22]

The Carondelet attacks Fort Donelson

General Grant had Commander Henry Walke bring the Carondelet up the Cumberland River to create a diversion by opening fire on the fort. The Confederates responded with shots from their long-range guns and eventually hit the gunboat. Walke retreated several miles below the fort, but soon returned and continued shelling the water batteries. General McClernand, in the meantime, had been attempting to stretch his men toward the river but ran into difficulties with a Confederate battery of guns. McClernand ultimately decided that he did not have enough men to stretch all the way to the river, so Grant decided to call on more troops. He sent orders to General Wallace, who had been left behind at Fort Henry, to bring his men to Fort Donelson.[23]

With Floyd's arrival to take command of Fort Donelson, Pillow took over leading the Confederate left. Feeling overwhelmed, Floyd left most of the actual command to Pillow and Buckner. At the end of the day, there had been several skirmishes, but the positions of each side were essentially the same. The night progressed with both sides fighting the cold weather.[24]

Although the weather had been mostly rainy up to this point in the campaign, a snow storm arrived the night of February 13, with strong winds that brought temperatures down to 10–12 °F (−12 °C) and deposited 3 inches (8 cm) of snow by morning. Guns and wagons were frozen to the earth. Because of the proximity of the enemy lines and the active sharpshooters, the soldiers could not light campfires for warmth or cooking, and both sides were miserable that night, many having arrived without blankets or overcoats.[25]

Reinforcements and naval battle (February 14)

Part of the lower river battery at Fort Donelson, overlooking the Cumberland River

At 1:00 a.m. on February 14, Floyd held a council of war in his headquarters at the Dover Hotel. There was general agreement that Fort Donelson was probably untenable. General Pillow was designated to lead a breakout attempt, evacuate the fort, and march to Nashville. Troops were moved behind the lines and the assault readied, but at the last minute a Union sharpshooter killed one of Pillow's aides. Pillow, normally quite aggressive in battle, was unnerved and announced that since their movement had been detected, the breakout had to be postponed. Floyd was furious at this change of plans, but by then it was too late in the day to proceed.[26]

On February 14, General Lew Wallace's brigade arrived from Fort Henry around noon, and Foote's flotilla arrived on the Cumberland River in mid-afternoon, bringing six gunboats and another 10,000 Union reinforcements on twelve transport ships. Wallace assembled these new troops into a third division of two brigades, under Cols. John M. Thayer and Charles Cruft, and occupied the center of the line facing the Confederate trenches. This provided sufficient troops to extend McClernand's right flank to be anchored on Lick Creek, by moving Col. John McArthur's brigade of Smith's division from the reserve to a position from which they intended to plug the 400 yards (370 m) gap at dawn the next morning.[27]

The gunboat attack on 14 February

As soon as Foote arrived, Grant urged him to attack the fort's river batteries. Although Foote was reluctant to proceed before adequate reconnaissance, he moved his gunboats close to the shore by 3:00 p.m. and opened fire, just as he had done at Fort Henry. Confederate gunners waited until the gunboats were within 400 yards (370 m) to return fire. The Confederate artillery pummeled the fleet and the assault was over by 4:30 p.m. Foote was wounded (coincidentally in his foot). The wheelhouse of his flagship, USS St. Louis, was carried away, and she floated helplessly downriver. USS Louisville was also disabled and the Pittsburg began to take on water. The damage to the fleet was significant and it retreated downriver.[28] Of the 500 Confederate shots fired, St. Louis was hit 59 times, Carondelet 54, Louisville 36, and Pittsburg 20 times. Foote had miscalculated the assault. Historian Kendall Gott suggested that it would have been more prudent to stay as far downriver as possible, and use the fleet's longer-range guns to reduce the fort. An alternative might have been to overrun the batteries, probably at night as would be done successfully in the 1863 Vicksburg Campaign. Once past the fixed river batteries, Fort Donelson would have been defenseless.[29]

Eight Union sailors were killed and 44 were wounded while the Confederates lost none. (Captain Joseph Dixon of the river batteries had been killed the previous day during Carondelet's bombardment.) On land the well-armed Union soldiers surrounded the Confederates, while the Union boats, although damaged, still controlled the river. Grant realized that any success at Fort Donelson would have to be carried by the army without strong naval support, and he wired Halleck that he might have to resort to a siege.[30]

Breakout attempt (February 15)

Confederate breakout attempt, morning February 15, 1862

Despite their unexpected naval success, the Confederate generals were still skeptical about their chances in the fort and held another late-night council of war, where they decided to retry their aborted escape plan. At dawn on February 15, the Confederates launched an assault led by Pillow against McClernand's division on the unprotected right flank of the Union line. The Union troops, unable to sleep in the cold weather, were not caught entirely by surprise, but Grant was. Not expecting a land assault from the Confederates, he was up before dawn and had headed off to visit Flag Officer Foote on his flagship downriver. Grant left orders that none of his generals was to initiate an engagement and no one was designated as second-in-command during his absence.[31]

The Confederate plan was for Pillow to push McClernand away and take control of Wynn's Ferry and Forge Roads, the main routes to Nashville.[17] Buckner was to move his division across Wynn's Ferry Road and act as rear guard for the remainder of the army as it withdrew from Fort Donelson and moved east. A lone regiment from Buckner's division—the 30th Tennessee—was designated to stay in the trenches and prevent a Federal pursuit. The attack started well, and after two hours of heavy fighting, Pillow's men pushed McClernand's line back and opened the escape route. It was in this attack that Union troops in the West first heard the famous, unnerving rebel yell.[32]

The attack was initially successful because of the inexperience and poor positioning of McClernand's troops and a flanking attack from the Confederate cavalry under Forrest. The Union brigades of Cols. Richard Oglesby and John McArthur were hit hardest; they withdrew in a generally orderly manner to the rear for regrouping and resupply. Around 8:00 a.m. McClernand sent a message requesting assistance from Lew Wallace, but Wallace had no orders from Grant, who was still absent, to respond to an attack on a fellow officer and declined the initial request. Wallace, who was hesitant to disobey orders, sent an aide to Grant's headquarters for further instructions.[33] In the meantime, McClernand's ammunition was running out, but his withdrawal was not yet a rout. (The army of former quartermaster Ulysses S. Grant had not yet learned to organize reserve ammunition and supplies near the frontline brigades.) A second messenger arrived at Wallace's camp in tears, crying, "Our right flank is turned! ... The whole army is in danger!"[34] This time Wallace sent a brigade, under Col. Charles Cruft, to aid McClernand. Cruft's brigade was sent in to replace Oglesby's and McArthur's brigades, but when they realized they had run into Pillow's Confederates and were being flanked, they too began to fall back.[35]

Not everything was going well with the Confederate advance. By 9:30 a.m., as the lead Union brigades were falling back, Nathan Bedford Forrest urged Bushrod Johnson to launch an all-out attack on the disorganized troops. Johnson was too cautious to approve of a general assault, but he did agree to keep the infantry moving slowly forward. Two hours into the battle, Gen. Pillow realized that Buckner's wing was not attacking alongside his. After a confrontation between the two generals, Buckner's troops moved out and, combined with the right flank of Pillow's wing, hit W. H. L. Wallace's brigade. The Confederates took control of Forge Road and a key section of Wynn's Ferry Road, opening a route to Nashville,[36] but Buckner's delay provided time for Lew Wallace's men to reinforce McClernand's retreating forces before they were completely routed. Despite Grant's earlier orders, Wallace's units moved to the right with Thayer's brigade, giving McClernand's men time to regroup and gather ammunition from Wallace's supplies. The 68th Ohio was left behind to protect the rear.[37]

The Confederate offensive ended around 12:30 p.m., when Wallace's and Thayer's Union troops formed a defensive line on a ridge astride Wynn's Ferry Road. The Confederates assaulted them three times, but were unsuccessful and withdrew to a ridge 0.5 miles (0.80 km) away. Nevertheless, they had had a good morning. The Confederates had pushed the Union defenders back one to two miles (2–3 km) and had opened their escape route.[38]

Grant, who was apparently unaware of the battle, was notified by an aide and returned to his troops in the early afternoon. Grant first visited C. F. Smith on the Union left, where Grant ordered the 8th Missouri and the 11th Indiana to the Union right,[17] then rode 7 miles (11 km) over icy roads to find McClernand and Wallace. Grant was dismayed at the confusion and a lack of organized leadership. McClernand grumbled "This army wants a head." Grant replied, "It seems so. Gentlemen, the position on the right must be retaken."[39]

Union counterattack, afternoon February 15, 1862

True to his nature, Grant did not panic at the Confederate assault. As Grant rode back from the river, he heard the sounds of guns and sent word to Foote to begin a demonstration of naval gunfire, assuming that his troops would be demoralized and could use the encouragement. Grant observed that some of the Confederates (Buckner's) were fighting with knapsacks filled with three days of rations, which implied to him that they were attempting to escape, not pressing for a combat victory. He told an aide, "The one who attacks first now will be victorious. The enemy will have to be in a hurry if he gets ahead of me."[40]

Despite the successful morning attack, access to an open escape route, and to the amazement of Floyd and Buckner, Pillow ordered his men back to their trenches by 1:30 p.m. Buckner confronted Pillow, and Floyd intended to countermand the order, but Pillow argued that his men needed to regroup and resupply before evacuating the fort. Pillow won the argument. Floyd also believed that C. F. Smith's division was being heavily reinforced, so the entire Confederate force was ordered back inside the lines of Fort Donelson, giving up the ground they gained earlier that day.[41]

1897 drawing of Grant's attack, depicting C.F. Smith on horseback leading his troops

Grant moved quickly to exploit the opening and told Smith, "All has failed on our right—you must take Fort Donelson." Smith replied, "I will do it." Smith formed his two remaining brigades to make an attack. Lauman's brigade would be the main attack, spearheaded by Col. James Tuttle's 2nd Iowa Infantry. Cook's brigade would be in support to the right and rear and act as a feint to draw fire away from Lauman's brigade. Smith's two-brigade attack quickly seized the outer line of entrenchments on the Confederate right from the 30th Tennessee, commanded by Col. John W. Head, who had been left behind from Buckner's division. Despite two hours of repeated counterattacks, the Confederates could not repel Smith from the captured earthworks. The Union was now poised to seize Fort Donelson and its river batteries when light returned the next morning.[42] In the meantime, on the Union right, Lew Wallace formed an attacking column with three brigades—one from his own division, one from McClernand's, and one from Smith's—to try to regain control of ground lost in the battle that morning. Wallace's old brigade of Zouaves (11th Indiana and 8th Missouri), now commanded by Col. Morgan L. Smith, and others from McClernand's and Wallace's divisions were chosen to lead the attack. The brigades of Cruft (Wallace's Division) and Leonard F. Ross (McClernand's Division) were placed in support on the flanks. Wallace ordered the attack forward. Smith, the 8th Missouri, and the 11th Indiana advanced a short distance up the hill using Zouave tactics, where the men repeatedly rushed and then fell to the ground in a prone position.[43] By 5:30 p.m. Wallace's troops had succeeded in retaking the ground lost that morning,[44] and by nightfall, the Confederate troops had been driven back to their original positions. Grant began plans to resume his assault in the morning, although neglecting to close the escape route that Pillow had opened.[45]

John A. Logan was gravely injured on February 15. Soon after the victory at Donelson, he was promoted to brigadier general in the volunteers.[citation needed]

Surrender (February 16)

Nearly 1,000 soldiers on both sides had been killed, with about 3,000 wounded still on the field; some froze to death in the snowstorm, many Union soldiers having thrown away their blankets and coats.[46]

Inexplicably, generals Floyd and Pillow were upbeat about the day's performance and wired General Johnston at Nashville that they had won a great victory. The General Simon Bolivar Buckner, however, argued that they were in a desperate position that was getting worse with the arrival of Union reinforcements. At their final council of war in the Dover Hotel at 1:30 a.m. on February 16, Buckner stated that if C.F. Smith attacked again, he could only hold for thirty minutes, and he estimated that the cost of defending the fort would be as high as a seventy-five percent casualty rate. Buckner's position finally carried the meeting. Any large-scale escape would be difficult. Most of the river transports were currently transporting wounded men to Nashville and would not return in time to evacuate the command.[47]

Floyd, who believed if he was captured, he would be indicted for corruption during his service as Secretary of War in President James Buchanan's cabinet before the war, promptly turned over his command to Pillow, who also feared Northern reprisals. In turn, Pillow passed the command to Buckner, who agreed to remain behind and surrender the army. During the night, Pillow escaped by small boat across the Cumberland. Floyd left the next morning on the only steamer available, taking his two regiments of Virginia infantry. Disgusted at the show of cowardice, a furious Nathan Bedford Forrest announced, "I did not come here to surrender my command." He stormed out of the meeting and led about seven hundred of his cavalrymen on their escape from the fort. Forrest's horsemen rode toward Nashville through the shallow, icy waters of Lick Creek, encountering no enemy and confirming that many more could have escaped by the same route, if Buckner had not posted guards to prevent any such attempts.[48]

On the morning of February 16, Buckner sent a note to Grant requesting a truce and asking for terms of surrender. The note first reached General Smith, who exclaimed, "No terms to the damned Rebels!" When the note reached Grant, Smith urged him to offer no terms. Buckner had hoped that Grant would offer generous terms because of their earlier friendship. (In 1854 Grant was removed from command at a U.S. Army post in California, allegedly because of alcoholism. Buckner, a fellow U.S. Army officer at that time, loaned Grant money to return home to Illinois after Grant had been forced to resign his commission.) To Buckner's dismay, Grant showed no mercy towards men he considered to be rebelling against the federal government. Grant's brusque reply became one of the most famous quotes of the war, earning him the nickname of "Unconditional Surrender":[49]

Grant's reply

Sir: Yours of this date proposing Armistice, and appointment of Commissioners, to settle terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.

I propose to move immediately upon your works.

I am Sir: very respectfully

Your obt. sevt.

U.S. Grant

Brig. Gen.[50]

Grant was not bluffing. Smith was now in a good position to move on the fort, having captured the outer lines of its fortifications, and was under orders to launch an attack with the support of other divisions the following day. Grant believed his position allowed him to forego a planned siege and successfully storm the fort.[51] Buckner responded to Grant's demand:

SIR:—The distribution of the forces under my command, incident to an unexpected change of commanders, and the overwhelming force under your command, compel me, notwithstanding the brilliant success of the Confederate arms yesterday, to accept the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms which you propose.[52]

Grant, who was courteous to Buckner following the surrender, offered to loan him money to see him through his impending imprisonment, but Buckner declined. The surrender was a personal humiliation for Buckner and a strategic defeat for the Confederacy, which lost more than 12,000 men, 48 artillery pieces, much of their equipment, and control of the Cumberland River, which led to the evacuation of Nashville.[53] This was the first of three Confederate armies that Grant would capture during the war. (The second was John C. Pemberton's at the Siege of Vicksburg and the third Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox). Buckner also turned over considerable military equipment and provisions, which Grant's troops badly needed. More than 7,000 Confederate prisoners of war were eventually transported from Fort Donelson to Camp Douglas in Chicago, Camp Morton in Indianapolis,[54] and other prison camps elsewhere in the North. Buckner was held as a prisoner at Fort Warren in Boston until he was exchanged in August 1862.[55]

Aftermath

The casualties at Fort Donelson were heavy, primarily because of the large Confederate surrender. Union losses were 2,691 (507 killed, 1,976 wounded, 208 captured/missing), Confederate 13,846 (327 killed, 1,127 wounded, 12,392 captured/missing).[3]