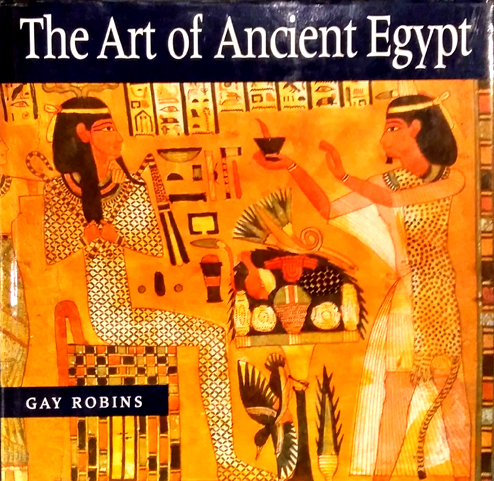

"The Art of Ancient Egypt" by Gay Robins.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Oversized hardcover with dustjacket. Publisher: Harvard University (1997). Pages: 272. Size: 10½ x 10¼ x 1 inch; 4 pounds. Summary: From the awesome grandeur of the great pyramids to the delicacy of a face etched on an amulet, the spellbinding power of the art of ancient Egypt persists to this day. This beautifully illustrated book conducts us through the splendors of this world, great and small, and into the mysteries of its fascination in its day as well as in our own. What did art, and the architecture that housed it, mean to the ancient Egyptians? Why did they invest such vast wealth and effort in its production? These are the puzzles Gay Robins explores as she examines the objects of Egyptian art--the tombs and wall paintings, the sculpture and stelae, the coffins, funerary papyri, and amulets--from its first flowering in the Early Dynastic period to its final resurgence in the time of the Ptolemies.

Spanning three thousand years, her book offers a thorough and delightfully readable introduction to the art of ancient Egypt even as it provides insight into questions that have long perplexed experts and amateurs alike. With remarkable sensitivity to the complex ways in which historical, religious, and social changes are related to changes in Egyptian art, she brings out the power and significance of the image in Egyptian belief and life. Her attention to the later period, including Ptolemaic art, shows for the first time how Egyptian art is a continuous phenomenon, changing to meet the needs of different times, right down to the eclipse of ancient Egyptian culture. In its scope, its detail, and its eloquent reproduction of over 250 objects from the British Museum and other collections in Europe, the United States, and Egypt, this volume is without parallel as a guide to the art of ancient Egypt.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. Lightly read hardcover w/dustjacket. Harvard University (1997) 272 pages. Looks as if it has has been read once or twice by someone with a very light hand. Inside the book is virtually pristine; pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, at worst, read once or twice very lightly. From the outside the dustjacket is clean, evidencing only very mild edge and corner shelfwear to dustjacket and covers. Shelfwear is principally in the form of very mild crinkling to the dustjacket spine head, and the top edges of both the front and back side of the dustjacket. Beneath the dustjacket the covers are clean and unblemished, likewise evidencing only very mild edge and corner shelfwear, though there is a very faint bump to the upper open corner of the front cover (as if it were bumped against a bookshelf edge). However the bump is not echoed by the pages beneath. Given the (albeit mild) shelf wear to the book together with the fact it has clearly been read, the book might lack the "sex appeal" of a "shelf trophy". Nonetheless for those not concerned with whether the book will or will not enhance their social status or intellectual reputation, it is an otherwise clean and only lightly read copy with "lots of miles left under the hood". Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #8766b.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: From the grandeur of the Great Pyramid to a face etched on an amulet, this book conducts the reader through the world of Egyptian art. It asks questions such as what did art and the architecture that housed it, mean to the ancient Egyptians and why did they invest so much wealth and effort into its production? To answer these questions, the book studies tomb and wall paintings, sculpture and stelae, coffins, funerary papyri and amulets from the early dynastic period to the time of the Ptolemies. Spanning 3000 years, historical, religious and social changes are related to changes in Egyptian art and the significance of the image in Egyptian belief and life is examined. The attention given to the later period, including Ptolemaic art, aims to show how Egyptian art is a continuous phenomenon, changing to meet the needs of different times.

REVIEW: From the awesome grandeur of the great pyramids to the delicacy of a face etched on an amulet, the spellbinding power of the art of ancient Egypt persists to this day. Spanning three thousand years, this beautifully illustrated history offers a thorough and delightfully readable introduction to the art of ancient Egypt even as it provides insight into questions that have long engaged experts and amateurs alike.

What did art, and the architecture that housed it, mean to the ancient Egyptians? Why did they invest such vast wealth and effort in its production? These are the puzzles that Gay Robins explores as she examines the objects of Egyptian art -- the tombs and wall paintings, the sculpture and stelae, the coffins, funerary papyri, and amulets -- from its first flowering in the Early Dynastic period to its final resurgence in the time of the Ptolemies. With remarkable sensitivity to the complex ways in which historical, religious, and social changes are related to changes in Egyptian art, she brings out the power and significance of the image in Egyptian belief and life.

REVIEW: From the awesome grandeur of the great pyramids to the delicacy of a face etched on an amulet, the power of the art of ancient Egypt persists to this day. This beautifully illustrated book conducts us through the splendors of this world, great and small, and into the mysteries of its fascination in its day as well as in our own. What did art, and the architecture that housed it, mean to the ancient Egyptians? Why did they invest such vast wealth and effort in its production? These are the puzzles Gay Robins explores as she examines the objects of Egyptian art - the tombs and wall paintings, the sculpture and stelae, the coffins, funerary papyri, and amulets - from its first flowering in the Early Dynastic period to its final resurgence in the time of the Ptolemies.

REVIEW: From the awesome grandeur of the Great Pyramids to the delicacy of a face etched on an amulet, the spellbinding power of ancient Egyptian art persists to this day. Spanning three thousand years, this beautifully illustrated history offers a thorough and delightfully readable introduction to the artwork even as it provides insight into questions that have long engaged experts and amateurs alike. In its scope, its detail, and its eloquent reproduction of over 250 objects, Gay Robins's classic book is without parallel as a guide to the art of ancient Egypt.

REVIEW: The art of ancient Egypt has never lost its power to inspire fascination and awe. Over some three thousand years the great civilization of the Nile Valley produced some of the finest works of art the world has ever known, whether exquisitely painted on tomb walls, carved in stone or wood, or cast in metal. Illustrated with over 250 remarkable objects from collections in Europe, the United States, and Egypt, this book traces the course of Egyptian art from its sudden initial flowering to its final resurgence during the rule of the Ptolemies.

Gay Robins, who brings to the subject many fresh insights based on firsthand study in Egypt, explains how the ancient artists developed an artistic system that was perfectly adapted to expressing the Egyptians’ world view, encapsulated in their religious and funerary beliefs. She explores the different functions of artistic products in temples, tombs, and everyday life, and stresses the importance of understanding them within the context for which they were originally designed. Finally, she demonstrates that, contrary to popular opinion, Egyptian art was not unvarying down the ages but was adapted, through changes in proportion, composition, style, and subject matter, to meet the needs of different periods..

REVIEW: Illustrated with over 250 remarkable objects from the British Museum and other collections in Europe, USA and Egypt, this text traces the course of Egyptian art from its sudden initial flowering to its final resurgence during the rule of the Ptolemies.

REVIEW: For some 3,000 years, the great civilization of the Nile Valley produced some of the finest works of art the world has ever known, whether exquisitely painted on tomb walls, carved in stone or wood, or cast in metal. Illustrated with over 250 remarkable objects from the British Museum and other collections in Egypt, the United States and Europe, this book traces the course of Egyptian art from its sudden initial flowering to its final resurgence during the rule of the Ptolemies. The author explains how the ancient artists developed a system that was perfectly adapted to expressing the Egyptians world view, encapsulated in their religious and funerary beliefs. She explores the different functions of artistic products in temples, tombs and everyday life, and stresses the importance of understanding them within the context for which they were originally designed

REVIEW: From the awesome grandeur of the Great Pyramids to the delicacy of a face etched on an amulet, the power of ancient Egyptian art persists to this day. Spanning three thousand years, this illustrated history offers a thorough and delightfully readable introduction to the artwork.

REVIEW: Gay Robins is Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Art History at Emory University.

REVIEW: Gay Robins is the Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of art history in the art history department at Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. She is a former Lady Wallis Budge Research Fellow in Egyptology at Christ’s College, Cambridge, and her numerous publications include Women in Ancient Egypt.

REVIEW: Gay Robins, PhD, is Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Art History at Emory University in Atlanta, GA and Michael C. Carlos Museum Faculty Consultant for Ancient Egyptian Art. Her areas of specialization include composition, style and proportion in Ancient Egyptian art, as well as issues of gender, sexuality, identity and memory. Dr. Robins earned her doctorate at the University Oxford in the UK and is a world renowned scholar specializing in ancient Egyptian art. She has published several books and numerous articles, including the popular titles "The Art of Ancient Egypt" and "Women in Ancient Egypt".

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Acknowledgements.

Foreword.

Chronology.

1. Understanding Ancient Egyptian Art.

2. Origins: The Early Dynastic Period.

3. The First Flowering: The Old Kingdom (I).

4. A Golden Age: The Old Kingdom (II).

5. Diversity in Disunity: The First Intermediate Period.

6. Return to the Heights: The Middle Kingdom (I).

7. Change and Collapse: The Middle Kingdom (II).

8. A New Momentum: The New Kingdom (I) - Ahmose To Amenhotep III.

9. The Great Heresy: The New Kingdom (II) - The Amarna Period And Its Aftermath.

10. The Glories of Empire: The New Kingdom (III).

11. Fragmentation and New Directions: The Third Intermediate Period.

12. Looking to the Past: The Late Period (I).

13. The Final Flowering: The Late Period (II) And Ptolemaic Period.

14. Epilogue.

Abbreviations and Bibliography.

Further Reading.

Illustration Acknowledgements.

Index.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: This beautifully illustrated volume presents an introduction to ancient Egyptian art for a broad audience. Ancient Egypt was a highly complex society, and by making Ancient Egyptian art accessible for the non-specialist, the author has provided an exceptional work. As the author stresses, ancient Egyptian art, whether utilized in a tomb or a temple, was meant to be functional rather than "for the sake of art." In other words, the various functions of Egyptian art are emphasized and the author gives an exciting, fresh perspective on form and function. This work is a case study on how to produce an introductory yet thorough overview on a particular subject for Robins has satisfied the need to be concise by choosing the most relevant and aesthetic material and illustrations. Furthermore, the plates and the explanations that accompany them are easily found on the same or adjacent pages, thus making them user-friendly. These things make the book useful for the general reader, especially one who is being exposed to Egyptian art for the first time.

The format utilized by the author is direct and logical: each chapter presents a topic that is then divided into sections. Additionally, the author deliberately traces objects of art and shows how styles evolved through time. Topics such as "The Egyptian World View," "Principles of Egyptian Art," and "Materials, Techniques and Artists" are clearly discussed, helping the reader understand and appreciate the role and function of ancient Egyptian art. Instead of a strictly thematic examination, the author adopts a chronological approach, showing how styles evolved through time by tracing the development of specific art objects. Well-known masterpieces are presented, but the book does not limit itself to these pieces since they are discussed at length in many works on Egyptian art. Therefore, the author includes lesser-known objects in her discussion, allowing the reader to have a more comprehensive view of ancient Egypt.

Chapter Two focuses on the formative years (Dynasties I and II, 2920-2649 B.C.) out of which emerged a unified state under a single king. It was during this period that basic rules of art were established. Chapters Three and Four are devoted to the Pyramid Age. In addition to pyramids, royal sculpture, sun-temples, non-royal tombs and statuary are treated at length and representations of servants are also discussed. The Third Dynasty (2649-2575 B.C.) was a time of consolidation, providing a transition between the Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom (2649-2134 B.C.), which is generally seen as the "golden age" of ancient Egypt. It was during this time that the power of the pharaoh was at its zenith. However, towards the end of the Sixth Dynasty, the size and decoration of the king's pyramid decreased, while at the same time, the tombs of members of the elite increased. The First Intermediate Period (Dynasties IV-VI 2134-2040 B.C.), which was characterized by the collapse of central authority, is discussed in Chapter Five. Here objects cause us to focus on the provinces and the author shows how the quality of art ranged from very crude to the well-developed pre-unification Theban style.

Chapters Six and Seven concentrate on the re-establishment of a unified government (Dynasties XI-XII 2040-1783 B.C.) and its gradual decline. The reemergence of pyramids, local temples and statues is well represented, but the work does not restrict itself to these items. Coffins, apotropaic objects and stelae are also included. Seventy-one pages (Chapters Eight to Ten) are devoted to the New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.C.). An excellent overview of the XVIIIth Dynasty (1550-1307 B.C.), a time of empire as well as one of international contact, is provided. Images of the king are now common in private tombs; moreover, there was also an emphasis on the divine king and the solar cult, something which had later consequences. Because much of what is known about this period comes from the area of Thebes, our information is extremely one-sided. While the author acknowledges this, she also tries to correct it by her careful selection of objects. She has done a good job of presenting a more balanced image of the XVIIIth Dynasty.

An entire chapter (nine) is devoted to the Amarna Period (1353-1335 B.C.) and its radical changes in art. In the aftermath of Amarna, art returned to more traditional renderings, although not all of Amarna's influences were completely abandoned. Chapter Ten covers "The Glories of Empire," with extensive data on funerary and state temples. Post-Amarna art is not presented as dull or stagnant, but as demonstrated by the author, must instead be seen as fresh and dynamic. Again, she shows the depth and range of subject matter--new Netherworld books were used in royal tombs, while the fate of the deceased was emphasized in non-royal tomb chapels.

Egypt's weakening in the Late Period (712-332 B.C.) is the subject of chapter eleven. During this time Egypt was ruled successively by kings of Kush and Assyria before her re-establishment as a major player in the Ancient Near East. Artistically, this period was marked by an archaizing trend, something that is well illustrated by the author. Chapter Twelve showcases the art of the Third Intermediate Period (1070-712 B.C.). Although this was a time of disunity and foreign rule, there was no radical diminishing in the quality of Egyptian art. A final blossoming of Egyptian Art under the Persians and Ptolemies is the subject of Chapter thirteen. The author concludes with an epilogue, extensive bibliography and suggestions for further reading.

The "Art of Ancient Egypt" is a wonderful work. It provides a fascinating glimpse of 3000 years of art in a pleasing, easy to read format. It enables the beginner to follow both the art and the history of ancient Egypt in a logical manner. However, the main strength of this work lies in its simplicity and elegance. It does exactly what it sets out to do and provides the reader a glimpse of an ancient civilization, which continues to intrigue and mesmerize students and scholars alike. [Bryn Mawr].

REVIEW: Although a handful of books surveying ancient Egyptian art are readily available and published with the general reader or classroom user in mind, Gay Robins's “The Art of Ancient Egypt” deserves to be singled out for its clearly presented and richly illustrated treatment of the subject. The informative text concentrates on "why art was so important to the ancient Egyptians and why they invested such a large amount of their resources in its production"( p. 7). Therefore in stead of being presented merely with a historical survey of the who, what, and where of Egyptian art, the reader is also introduced to the facets of Egyptian society-religion, status, gender, and so forth-that underpinned the production and deployment of art. This emphasis on the social context of the visual arts and architecture is a welcome advance from the subjective stylistic judgments that have too often characterized Egyptological art history.

Robins is not specifically engaged with setting Egypt in an African context, other than relaying the physical facts of the country's geography. The ancient Egyptians saw themselves and the agricultural land of the Nile Valley and Delta as the normative, privileged maintainers of a divine world order, mediated for them by the king. Other-ness was associated with chaos and had to be subjugated, a feat represented in art by monumental battle scenes and by the emblematic motif of bound foreign prisoners, whose names and physiognomies identified them as residents of Egypt's immediate neighbors: Libya, Nubia, and Syria-Palestine.

Following long-standing trade and military connections between Egypt and Nubia, a combination of conquest and cultural assimilation resulted in a succession of Nubian kings who ruled Egypt as part of the Napatan empire from about 770 to 712 B .C. In Egyptian chronology, these kings form the 25th Dynasty, and Robins presents their Egyptian monuments and their adaptation of Egyptian royal iconography. Art and architecture in the Sudan itself are beyond the scope of this volume, but the reader could pursue this area a bit further through references in the bibliography.

Robins's book follows a chronological sequence ranging from the period of early state formation in the Nile Valley (circa 3100-3000 B.C.) to the end of the Ptolemaic period (30 B.C.), a cut-off point which the author justifies because it marked the last time that Egypt was ruled by a resident monarch. The first chapter provides a concise, accurate, and engaging introduction to Egyptian artistic principles and their roots in Egyptian cosmology and social organization. Egyptians visualized a world in which chaotic, external forces threatened the ordered creation, and this duality, characterized by a need to maintain balance and control, was expressed in many ways, from myths of divine death and rebirth to the structured compositions of Egyptian art and texts. This first chapter also usefully surveys the working methods and materials of Egyptian artists, who were, by and large anonymous.

Archaeological and documentary evidence from a village of state-supported workmen (Deir el-Medina, circa. 1300-1100 B.C.), however, gives some insight into how artists were trained and organized. Each of the following twelve chapters, which comprise the chronological survey, is subdivided into sections considering, on the one hand, royal art and, on the other, the art of the elite, those prosperous non-royal individuals who held secular and sacred offices at a national or provincial level. These two spheres provided the patronage for the visual arts and affected or interacted with each other in different ways, depending on the political and economic climate of a given period. Unsurprisingly, many aspects of artistic expression were exclusive to the king, due both to his position and to the resources he commanded. Art forms commissioned by the elite are no less important for understanding Egyptian art, and Robins adequately treats non-royal sculpture, tombs, and funerary equipment in this regard.

At the beginning of each chapter, a brief overview covers historical developments during the time period to be considered, and chapter endnotes point the interested reader to scholarly support for the evidence presented. A short, final chapter summarizes the roles and functions of art in ancient Egyptian society, where "[t]he king and the elite were both the patrons and the audience in a self-sustaining system that reinforced and justified the established social order". It also challenges the common misconception that Egyptian art is, or was, monotonous and unchanging. More than 300 illustrations are spread throughout the text and include color and black-and-white photographs, line drawings, and architectural plans and reconstructions. All are generally well reproduced and suit the volume's length and purpose; since the book was initially published by British Museum Press in 1997, objects from the important Egyptian collection of the British Museum predominate.

The volume also includes a chronological table, a map of Egypt as far south as Lake Nasser, a bibliography of scholarly works cited in the text, and a list of suggestions for further reading. All of the suggested items are in English, and several cover subjects not fully treated in the text, but most of these will only be available through a good university library or specialist bookseller. Finally, the index contains as many references to figures as to the text, making it easy to locate an illustration of a specific subject or a certain site; nevertheless, the index, like the bibliography and further reading list, seems geared toward a reader already familiar with the topic or a student wishing to delve even further into it. Taken as a whole, the book is suitable for the general public, but its quality, level of detail, and scholarly approach make it especially appropriate for university courses. The “Art of Ancient Egypt” will be a valuable resource for anyone teaching or studying ancient Egypt as part of a syllabus on African art or the art of the ancient Near East and Mediterranean. [University of California at Berkeley).

REVIEW: The author brings her erudition, perception, and sensitivity to the daunting task of surveying 3,000 years of Egyptian art, and produces some of the most incisive and elegant prose ever written on the vast topic. [Egyptian Archaeology Magazine].

REVIEW: Robins (art history, Emory University.) has produced the first significant general survey of ancient Egyptian art in the English language since Cyril Aldred's Egyptian Art in the Days of the Pharaohs, 3100-320 BC (Oxford University, 1980) and W. Stevenson Smith's The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt (Penguin, 1981). The first chapter orients the reader in the cultural, technical, and iconographic contexts needed to explore the evolution of the Egyptian artistic tradition in subsequent chapters. Beginning with the pre-dynastic origins (5000 B.C.) and concluding in the Ptolemaic Period (304-30 B.C.), Robins traces the development of sculpture, painting, funerary and religious art, and architecture with over 300 illustrations, many in color. Unique to this survey is the inclusion of Ptolemaic art and the attention paid to the decoration of sarcophagi, coffins, and mummy cartonnages over three millennia. The text is authoritative and fully referenced with an excellent bibliography. This work will interest general readers as well as scholars and is recommended for all public and academic libraries. [Library Journal].

REVIEW: Covering three millennia of Egyptian art, this beautifully illustrated volume presents a chronological survey of the monuments and art works of the ruling elite of ancient Egypt. Opening with an introductory chapter on the function and aesthetic principles of Egyptian art that includes a section on material and techniques, this highly readable volume features 150 color and 150 b/w illustrations, accompanied by substantial informative captions. Each historical chapter concludes with a succinct summary of the detailed discussion covered on the preceding pages, and each supports the author's central thesis that the art of ancient Egypt served primarily to bolster the power of the ruling class and support the clearly delineated social hierarchy. The generous use of line drawings and architectural plans supplements the beautiful photographs of temples, wall paintings, sculptures, coffins, and tomb furnishings. An extensive bibliography is included along with a detailed chronology and map. An index makes it easy to find information on such well-known figures as Cleopatra, Nefertiti, and Tutankhamun as well as such topics as funerary practices, fertility figures, and artists' workshops. This book is sure to delight anyone interested in the art and archaeology of the ancient world. Recommended for senior high school students, advanced students, and adults. [KLIATT Magazine].

REVIEW: Written by a leading Egyptologist, this is an authoritative text on ancient Egyptian art from the Early Dynastic to the Ptolemaic period. [Blackwell's (UK)].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: "The Art of Ancient Egypt" is, in a word, magnificent. In the forward, Robins writes that her primary aim is to explore the reasons why art was so important to the ancient Egyptians. She succeeds brilliantly. There are over 300 images in the book - most of them color photographs - showing the stylistic changes in Egyptian art from the early dynastic period through the Ptolemies. While the vast majority of the art is for royalty, in each period of Egyptian history Robins includes a close consideration of "non-royal monuments." And while art is the primary focus of the book, a good third of her attention is directed towards architecture as well. I cannot think of anything more that I would want or expect on the topic.

With this ringing endorsement, a few details that Robins brought to my attention that I had never considered or realized. The first (and most significant) is that Egyptian art *does* change and evolve over time. Certainly there are consistent themes and forms in the art, the changes subtle and nuanced, but the joy (and interest) of studying this is finding and explaining these differences. For example, following the end of the Old Kingdom (2134 B.C.), provincial rulers in Upper Egypt didn't have access to the skilled artisans in Memphis (the cultural center of ancient Egypt), and therefore had to use whatever local talent they had. As a result, Upper Egyptian art from the First Intermediate Period (2134-2040 B.C.) has its own unique style: large eyes, a high, small back, and a lack of musculature in male figures. With the reunification of Egypt during the Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 B.C.), there is a deliberate return to Old Kingdom styles, a signal of political centralization and an underscoring of the connection between the 11th dynasty kings and the Old Kingdom 6th dynasty.

Another detail that I had seen (but had been wholly unaware of) was the proportions the Egyptians used, and how the relationship of these proportions changed over time. For example, in the 12th dynasty (1991-1793 B.C.), there were 18 "squares" between the sole of a figure's feet and the crown of the head. These proportions changed between the 13th and 17th dynasties (1793-1150 B.C.) and again with the 18th dynasty (1550-1307 B.C.) - most noticeably during the reign of the "heretic king" Amunhotep IV / Alhenaten (when not only the proportions changed, but so too the number of squares increased to accommodate for the longer neck and face.)

Robins' writing style is academic without being pretentious. The way in which she seamlessly synthesizes the broader themes of Egyptian society with the major historical events of ancient Egypt while connecting them to the trends and changes in art is another strength of the book. She does this so well, readers are likely not to notice; to pull this off seemingly so effortlessly is not easy, and is testament to her skill as a writer and her mastery of the subject. For those interested in art history, I imagine this would be a "must-have" text, as well as those with a strong interest (like me) in ancient Egypt. Highly recommended.

REVIEW: This book covers Egyptian art period by period, from the Predynastic Period into the Old Kingdom, the Intermediate periods, the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom. The text is easy to read, and the many pictures do a great job of showing you hundreds of examples of ancient Egyptian art. I was very, very impressed with the artistic achievements of this ancient land and found myself gazing at the pictures in downright amazement.

Robins explains each period's artistic conventions and styles and discusses changes in those styles over time and across media, going into enough detail to let you know what is going on without becoming tedious. She talks about statues, tomb paintings, wall carvings, jewelry, coffins, furniture, and many other art forms within these pages and discusses the gods of ancient Egypt and their roles along the way to enlightening you as to what you're seeing.

I am a beginner at ancient Egyptian art, and this book was geared toward me. It has simple, straightforward explanations and excellent captions for the images that tell you what you're looking at and its significance to the field of Egyptian art. I read the entire book but must admit I bought it for the pictures, which are full color and represent many types and styles of art objects. Nothing tells art history like pictures, which you can examine to your heart's content; the explanations can point out and explain relevant features, but you must take in these features with your own two eyes in order to absorb them properly. A must-have for the beginner in Egyptology who wants a firm foundation in the art history of one of the world's greatest civilizations!

REVIEW: This book is an excellent introduction for the general reader into the 3000 year history of ancient Egyptian art. Robins' writing style is clear and accessible, her illustrations well-chosen and exceptionally well-captioned. Presenting a chronological overview rather than a strict thematic examination, Robins carefully walks the reader through the centuries as Egyptian artistic expression began in various mediums and developed specific styles. She lifts for recognition the philosophical integration of Egyptian metaphysics and aesthetics that was always displayed in art work meant to be functional rather than decorative, whether used in a tomb or a temple. Woven throughout her text is an argument for an Egyptian style that was continuous for the length of the Egyptian civilization, a style that avoided foreign influences until the Roman rule that came following the death of Cleopatra VII. The colors plates are beautiful and provide the armchair Egyptologist with an opportunity to become familiar with wonderful monuments and delicate objects joined in their expression of an Egyptian cosmological understanding that remained intact across three millennium.

REVIEW: I have been to Egypt, the first time was in 1993, and I made my mind up that I'd like to study Egyptology. I'm now in my third year of studying Egyptology with Exeter University, and although this book is not one of my assigned study books, I still wanted to read it as it was highly recommended by a number of my professors. I have read other books by Gay Robins on different aspects of Egyptology besides this which is specifically on Egyptian Art through the different dynasties of Egyptians history, all have been in-depth, interesting, enjoyable and compelling to read.

This book concentrates on all Art that has survived the ravages of time. It's an authoritative and splendidly illustrated book with both black and white and colored photographs, (She examines all the art from that time; the tombs and wall paintings, sculptures, stelae, the coffins, funerary papyrus and amulets). She's very sensitive to the Ancient Egyptians complex ways in which historical, religious and social changes were reflected in their art. Whether you are studying Egyptology or Art its well worth the money and its one book I will read again. :-)

REVIEW: This book is excellent! I teach Ancient Art History and bought this book as a companion to the text used in my classroom. The textbook our district uses mentions topics briefly and gives a little information, but too little. This book provided much greater comprehension, without being pedantic. For instance, it allowed me to explain the weighing of the heart. The Art of Ancient Egypt is not an over complicated book. It is written so that everyone can enjoy Egyptian art, not just the scholarly few. I treasure this book and have recommended it to my students.

REVIEW: A knockout! I have nothing substantial to add to the laudatory reviews left by other reviewers. But I was so impressed and pleased with my purchase that I felt obliged to say so. The book is beautifully produced with superb color pictures, added to which the illustrations are not the same old/same old that have appeared over and over again. The text is intelligently written and interesting, steering a steady course well between the levels of pop introduction and scholarly tome. It would be among the best purchases for anyone with more than a passing interest in the subject.

REVIEW: Clearly and thoroughly explained, this book provides an accurate description of Egyptian art from the Early Dynastic Period to the Ptolemaic Period. The author demonstrates the importance and place of art in Ancient Egypt. Beautiful illustrations from tomb paintings, sculptures, coffins, and many objects accompany the text. A definite must for both students and professionals.

REVIEW: Best book written on the topic of ancient Egyptian art! Love, love this book! Such a great resource with so much information and beautiful pictures!

REVIEW: This turned out to be exactly what I was looking for which was a basic explanation of Egyptian art. It is extremely well organized and is not written in a dense fashion. The illustrations/photos of art have good, lengthy explanations next to them - telling you exactly what you are looking at, not just "wall painting from tomb". I really wish all art history books were this well written and lushly illustrated.

REVIEW: Great Book - for an Interior Architect/Designer. When I ordered this book I was a bit worried it won't be what I want. I was designing a project (Egyptian Style). I was so happy when it arrived. It has both the history facts and the brilliant photos. It is a real treasure! I love this book!

REVIEW: This book was well written interesting and had great full color illustrations. It was interesting to find out that the Ancient Egyptians didn't have a word for art, in the same way we do today, rather it was an integral part of religious traditions.

REVIEW: This book is a classic, plain and simple. Robins is the leading (living) expert on Egyptian art, and her introduction to it in this lavishly illustrated volume is the most up-to-date source out there. Other classics (for instance, William Stevenson Smith's volume) are perhaps more thorough, but they are also so old as to border on antiquated at this point.

REVIEW: The most comprehensive book on Egyptian art! I bought this book as a text book for a college class. Not only did I learn so much about the art of this amazing ancient society, I learned about their culture that spanned for thousands of years. This book will definitely give you a deep understanding of Egyptian art.

REVIEW: Wonderful book on Egyptian art. Outlines Egyptian art styles through the Ptolemaic. Lots of beautiful illustrations.

REVIEW: Fabulous book! Clear explanations, stunning photography. This is assigned reading for my class on Ancient Egyptian Art. This is a book I will enjoy referencing long after my course concludes.

REVIEW: This book is written for a laymen to understand and the imagery in this book is fabulous! I can't think of a page that doesn't show at least some images of Egyptian Art. Definitely worth the money.

REVIEW: The opening orientation guides the reader/student to the fundamentals of understanding ancient Egyptian "art." The photographs of paintings, statues, and walls stun with beauty and the descriptions are clarion.

REVIEW: I enjoy browsing through this book very much. It is beautifully illustrated and the text is informative and complements the illustrations very nicely.

REVIEW: Robins provides a wide range of information in an easy to read format. Book has extensive captions for each image that provides greater detail.

REVIEW: Lots of facts about various kinds of art in ancient Egypt. I liked the fact that it was arranged chronologically.

REVIEW: Great for college and teaching all art levels. Great book! Lots of fabulous information.

REVIEW: Full of great information and wonderful illustrations.

REVIEW: I love the full color pictures and detailed explanations of what the artifacts mean.

REVIEW: The art nut in my family really enjoyed this book.

REVIEW: Five stars! Very nice book.

REVIEW: Five stars! Amazing book!

REVIEW: Five stars! Excellent product.

REVIEW: Five stars! Worked great for college!

REVIEW: Five stars! Quite comprehensive.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

REVIEW: The artworks of ancient Egypt have fascinated people for thousands of years. The early Greek and later Roman artists were influenced by Egyptian techniques and their art would inspire those of other cultures up to the present day. Many artists are known from later periods but those of Egypt are completely anonymous and for a very interesting reason: their art was functional and created for a practical purpose whereas later art was intended for aesthetic pleasure. Functional art is work-made-for-hire, belonging to the individual who commissioned it, while art created for pleasure - even if commissioned - allows for greater expression of the artist's vision and so recognition of an individual artist.

A Greek artist like Phidias (circa 490-430 B.C.) certainly understood the practical purposes in creating a statue of Athena or Zeus but his primary aim would have been to make a visually pleasing piece, to make "art" as people understand that word today, not to create a practical and functional work. All Egyptian art served a practical purpose: a statue held the spirit of the god or the deceased; a tomb painting showed scenes from one's life on earth so one's spirit could remember it or scenes from the paradise one hoped to attain so one would know how to get there; charms and amulets protected one from harm; figurines warded off evil spirits and angry ghosts; hand mirrors, whip-handles, cosmetic cabinets all served practical purposes and ceramics were used for drinking, eating, and storage. Egyptologist Gay Robins notes:

"As far as we know, the ancient Egyptians had no word that corresponded exactly to our abstract use of the word `art'. They had words for individual types of monuments that we today regard as examples of Egyptian art - 'statue', 'stela', 'tomb' -but there is no reason to believe that these words necessarily included an aesthetic dimension in their meaning. 'Art for art's sake' was unknown and further, would have probably been incomprehensible to an ancient Egyptian who understood art as functional above all else."

Although Egyptian art is highly regarded today and continues to be a great draw for museums featuring exhibits, the ancient Egyptians themselves would never have thought of their work in this same way and certainly would find it strange to have these different types of works displayed out of context in a museum's hall. Statuary was created and placed for a specific reason and the same is true for any other kind of art. The concept of "art for art's sake" was unknown and, further, would have probably been incomprehensible to an ancient Egyptian who understood art as functional above all else.

This is not to say the Egyptians had no sense of aesthetic beauty. Even Egyptian hieroglyphics were written with aesthetics in mind. A hieroglyphic sentence could be written left to right or right to left, up to down or down to up, depending entirely on how one's choice affected the beauty of the finished work. Simply put, any work needed to be beautiful but the motivation to create was focused on a practical goal: function. Even so, Egyptian art is consistently admired for its beauty and this is because of the value ancient Egyptians placed on symmetry.

The perfect balance in Egyptian art reflects the cultural value of ma'at (harmony) which was central to the civilization. Ma'at was not only universal and social order but the very fabric of creation which came into being when the gods made the ordered universe out of undifferentiated chaos. The concept of unity, of oneness, was this "chaos" but the gods introduced duality - night and day, female and male, dark and light - and this duality was regulated by ma'at.

It is for this reason that Egyptian temples, palaces, homes and gardens, statuary and paintings, signet rings and amulets were all created with balance in mind and all reflect the value of symmetry. The Egyptians believed their land had been made in the image of the world of the gods and, when someone died, they went to a paradise they would find quite familiar. When an obelisk was made it was always created and raised with an identical twin and these two obelisks were thought to have divine reflections, made at the same time, in the land of the gods. Temple courtyards were purposefully laid out to reflect creation, ma'at, heka (magic), and the afterlife with the same perfect symmetry the gods had initiated at creation. Art reflected the perfection of the gods while, at the same time, serving a practical purpose on a daily basis.

The art of Egypt is the story of the elite, the ruling class. Throughout most of Egypt's historical periods those of more modest means could not afford the luxury of artworks to tell their story and it is largely through Egyptian art that the history of the civilization has come to be known. The tombs, tomb paintings, inscriptions, temples, even most of the literature, is concerned with the lives of the upper class and only by way of telling these stories are those of the lower classes revealed. This paradigm was already set prior to the written history of the culture. Egyptian art begins in the Pre-Dynastic Period (circa 6000-3150 B.C.) through rock drawings and ceramics but is fully realized by the Early Dynastic Period (circa 3150-2613 B.C.) in the famous Narmer Palette.

The Narmer Palette (circa 3150 B.C.) is a two-sided ceremonial plate of siltstone intricately carved with scenes of the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by King Narmer. The importance of symmetry is evident in the composition which features the heads of four bulls (a symbol of power) at the top of each side and balanced representation of the figures which tell the story. The work is considered a masterpiece of Early Dynastic Period art and shows how advanced Egyptian artists were at the time.

The later work of the architect Imhotep (circa 2667-2600 B.C.) on the pyramid of King Djoser (circa 2670 B.C.) reflects how far artworks had advanced since the Narmer Palette. Djoser's pyramid complex is intricately designed with lotus flowers, papyrus plants, and djed symbols in high and low relief and the pyramid itself, of course, is evidence of the Egyptian skill in working in stone on monumental artworks.

During the Old Kingdom (circa 2613-2181 B.C.) art became standardized by the elite and figures were produced uniformly to reflect the tastes of the capital at Memphis. Statuary of the late Early Dynastic and early Old Kingdom periods is remarkably similar although other art forms (painting and writing) show more sophistication in the Old Kingdom. The greatest artworks of the Old Kingdom are the Pyramids and Great Sphinx at Giza which still stand today but more modest monuments were created with the same precision and beauty. Old Kingdom art and architecture, in fact, was highly valued by Egyptians in later eras. Some rulers and nobles (such as Khaemweset, fourth son of Ramesses II) purposefully commissioned works in Old Kingdom style, even the eternal home of their tombs.

In the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 B.C.), following the collapse of the Old Kingdom, artists were able to express individual and regional visions more freely. The lack of a strong central government commissioning works meant that district governors could requisition pieces reflecting their home province. These different districts also found they had more disposable income since they were not sending as much to Memphis. More economic power locally inspired more artists to produce works in their own style. Mass production began during the First Intermediate Period also and this led to a uniformity in a given region's artwork which made it at once distinctive but of lesser quality than Old Kingdom work. This change can best be seen in the production of shabti dolls for grave goods which were formerly made by hand.

Art would flourish during the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 B.C.) which is generally considered the high point of Egyptian culture. Colossal statuary began during this period as well as the great temple of Karnak at Thebes. The idealism of Old Kingdom depictions in statuary and paintings was replaced by realistic representations and the lower classes are also found represented more often in art than previously. The Middle Kingdom gave way to the Second Intermediate Period (circa 1782-1570 B.C.) during which the Hyksos held large areas of the Delta region while the Nubians encroached from the south. Art from this period produced at Thebes retains the characteristics of the Middle Kingdom while that of the Nubians and Hyksos - both of whom admired and copied Egyptian art - differs in size, quality, and technique.

The New Kingdom (circa 1570-1069 B.C.), which followed, is the best known period from Egypt's history and produced some of the finest and most famous works of art. The bust of Nefertiti and the golden death mask of Tutankhamun both come from this era. New Kingdom art is defined by a high quality in vision and technique due largely to Egypt's interaction with neighboring cultures. This was the era of Egypt's empire and the metal-working techniques of the Hittites - who were now considered allies, if not equals - greatly influenced the production of funerary artifacts, weaponry, and other artwork.

Following the New Kingdom the Third Intermediate Period (circa 1069-525 B.C.) and Late Period (525-332 B.C.) attempted with more or less success to continue the high standard of New Kingdom art while also evoking Old Kingdom styles in an effort to recapture the declining stature of Egypt. Persian influence in the Late Period is replaced by Greek tastes in the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 B.C.) which also tries to suggest the Old Kingdom standards with New Kingdom technique and this paradigm persists into the Roman Period (30 B.C.-646 A.D.) and the end of Egyptian culture.

Throughout all these eras, the types of art were as numerous as human need, the resources to make them, and the ability to pay for them. The wealthy of Egypt had ornate hand mirrors, cosmetic cases and jars, jewelry, decorated scabbards for knives and swords, intricate bows, sandals, furniture, chariots, gardens, and tombs. Every aspect of any of these creations had symbolic meaning. In the same way the bull motif on the Narmer Palette symbolized the power of the king, so every image, design, ornamentation, or detail meant something relating to its owner.

Among the most obvious examples of this is the golden throne of Tutankhamun (circa 1336-1327 B.C.) which depicts the young king with his wife Ankhsenamun. The couple are represented in a quiet domestic moment as the queen is rubbing ointment onto her husband's arm as he sits in a chair. Their close relationship is established by the color of their skin, which is the same. Men are usually depicted with reddish skin because they spent more time outdoors while a lighter color was used for women's skin as they were more apt to stay out of the sun. This difference in the shade of skin tones did not represent equality or inequality but was simply an attempt at realism.

In the case of Tutankhamun's throne, however, the technique is used to express an important aspect of the couple's relationship. Other inscriptions and art work make clear that they spent most of their time together and the artist expresses this through their shared skin tones; Ankhesenamun is just as sun-tanned as Tutankhamun. The red used in this composition also represents vitality and the energy of their relationship. The couple's hair is blue, symbolizing fertility, life, and re-birth while their clothing is white, representing purity. The background is gold, the color of the gods, and all of the intricate details, including the crowns the figures wear and their colors, all have their own specific meaning and go to tell the story of the featured couple.

A sword or a cosmetic case was designed and created with this same goal in mind: story-telling. Even the garden of a house told a story: in the center was a pool surrounded by trees, plants, and flowers which, in turn, were surrounded by a wall and one entered the garden from the house through a portico of decorated columns. All of these would have been arranged carefully to tell a tale which was significant to the owner. Although Egyptian gardens are long gone, models made of them as grave goods have been found which show the great care which went into laying them out in narrative form.

In the case of the noble Meket-Ra of the 11th Dynasty, the garden was designed to tell the story of the journey of life to paradise. The columns of the portico were shaped like lotus blossoms, symbolizing his home in Upper Egypt, the pool in the center represented Lily Lake which the soul would have to cross to reach paradise, and the far garden wall was decorated with scenes from the afterlife. Every time Meket-Ra would sit in his garden he would be reminded of the nature of life as an eternal journey and this would most likely lend him perspective on whatever circumstances might be troubling at the moment.

The paintings on Meket-Ra's walls would have been done by artists mixing colors made from naturally occurring minerals. Black was made from carbon, red and yellow from iron oxides, blue and green from azurite and malachite, white from gypsum and so on. The minerals would be mixed with crushed organic material to different consistencies and then further mixed with an unknown substance (possibly egg whites) to make it sticky so it would adhere to a surface. Egyptian paint was so durable that many works, even those not protected in tombs, have remained vibrant after over 4,000 years.

Although home, garden, and palace walls were usually decorated with flat two-dimensional paintings, tomb, temple, and monument walls employed reliefs. There were high reliefs (in which the figures stand out from the wall) and low reliefs (where the images are carved into the wall). To create these, the surface of the wall would be smoothed with plaster which was then sanded. An artist would create a work in minature and then draw gridlines on it and this grid would then be drawn on the wall. Using the smaller work as a model, the artist would be able to replicate the image in the correct proportions on the wall. The scene would first be drawn and then outlined in red paint. Corrections to the work would be noted, possibly by another artist or supervisor, in black paint and once these were taken care of the scene was carved and painted.

Paint was also used on statues which were made of wood, stone, or metal. Stone work first developed in the Early Dynastic Period and became more and more refined over the centuries. A sculptor would work from a single block of stone with a copper chisel, wooden mallet, and finer tools for details. The statue would then be smoothed with a rubbing cloth. The stone for a statue was selected, as with everything else in Egyptian art, to tell its own story. A statue of Osiris, for example, would be made of black schist to symbolize fertility and re-birth, both associated with this particular god.

Metal statues were usually small and made of copper, bronze, silver, and gold. Gold was particularly popular for amulets and shrine figures of the gods since it was believed that the gods had golden skin. These figures were made by casting or sheet metal work over wood. Wooden statues were carved from different pieces of trees and then glued or pegged together. Statues of wood are rare but a number have been preserved and show tremendous skill.

Cosmetic chests, coffins, model boats, and toys were made in this same way. Jewelry was commonly fashioned using the technique known as cloisonne in which thin strips of metal are inlaid on the surface of the work and then fired in a kiln to forge them together and create compartments which are then detailed with jewels or painted scenes. Among the best examples of cloisonne jewelry is the Middle Kingdom pendant given by Senusret II (circa 1897-1878 B.C.) to his daughter. This work is fashioned of thin gold wires attached to a solid gold backing inlaid with 372 semi-precious stones. Cloisonne was also used in making pectorals for the king, crowns, headdresses, swords, ceremonial daggers, and sarcophagi among other items.

Although Egyptian art is famously admired it has come under criticism for being unrefined. Critics claim that the Egyptians never seem to have mastered perspective as there is no interplay of light and shadow in the compositions, they are always two dimensional, and the figures are emotionless. Statuary depicting couples, it is argued, show no emotion in the faces and the same holds true for battle scenes or statues of a king or queen.

These criticisms fail to recognize the functionality of Egyptian art. The Egyptians understood that emotional states are transitory; one is not consistently happy, sad, angry, content throughout a given day much less eternally. Art works present people and deities formally without expression because it was thought the person's spirit would need that representation in order to live on in the afterlife. A person's name and image had to survive in some form on earth in order for the soul to continue its journey. This was the reason for mummification and the elaborate funerary rituals: the spirit needed a 'beacon' of sorts to return to when visiting earth for sustenance in the tomb.

The spirit might not recognize a statue of an angry or jubilant version of themselves but would recognize their staid, complacent, features. The lack of emotion has to do with the eternal purpose of the work. Statues were made to be viewed from the front, usually with their backs against a wall, so that the soul would recognize their former selves easily and this was also true of gods and goddesses who were thought to live in their statues.

Life was only a small part of an eternal journey to the ancient Egyptians and their art reflects this belief. A statue or a cosmetics case, a wall painting or amulet, whatever form the artwork took, it was made to last far beyond its owner's life and, more importantly, tell that person's story as well as reflecting Egyptian values and beliefs as a whole. Egyptian art has served this purpose well as it has continued to tell its tale now for thousands of years. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

REVIEW: Ancient Egyptian culture flourished between circa 5500 B.C. with the rise of technology (as evidenced in the glass-work of faience) and 30 B.C. with the death of Cleopatra VII, the last Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt. It is famous today for the great monuments which celebrated the triumphs of the rulers and honored the gods of the land. The culture is often misunderstood as having been obsessed with death but, had this been so, it is unlikely it would have made the significant impression it did on other ancient cultures such as Greece and Rome. The Egyptian culture was, in fact, life affirming, as the scholar Salima Ikram writes:

"Judging by the numbers of tombs and mummies that the ancient Egyptians left behind, one can be forgiven for thinking that they were obsessed by death. However, this is not so. The Egyptians were obsessed by life and its continuation rather than by a morbid fascination with death. The tombs, mortuary temples and mummies that they produced were a celebration of life and a means of continuing it for eternity…For the Egyptians, as for other cultures, death was part of the journey of life, with death marking a transition or transformation after which life continued in another form, the spiritual rather than the corporeal." This passion for life imbued in the ancient Egyptians a great love for their land as it was thought that there could be no better place on earth in which to enjoy existence. While the lower classes in Egypt, as elsewhere, subsisted on much less than the more affluent, they still seem to have appreciated life in the same way as the wealthier citizens. This is exemplified in the concept of gratitude and the ritual known as The Five Gifts of Hathor in which the poor labourers were encouraged to regard the fingers of their left hand (the hand they reached with daily to harvest field crops) and to consider the five things they were most grateful for in their lives. Ingratitude was considered a `gateway sin’ as it led to all other types of negative thinking and resultant behaviour. Once one felt ungrateful, it was observed, one then was apt to indulge oneself further in bad behaviour. The Cult of Hathor was very popular in Egypt, among all classes, and epitomizes the prime importance of gratitude in Egyptian culture.

Religion was an integral part of the daily life of every Egyptian. As with the people of Mesopotamia, the Egyptians considered themselves co-labourers with the gods but with an important distinction: whereas the Mesopotamian peoples believed they needed to work with their gods to prevent the recurrence of the original state of chaos, the Egyptians understood their gods to have already completed that purpose and a human’s duty was to celebrate that fact and give thanks for it. So-called `Egyptian mythology’ was, in ancient times, as valid a belief structure as any accepted religion in the modern day.

Egyptian religion taught the people that, in the beginning, there was nothing but chaotic swirling waters out of which rose a small hill known as the Ben-Ben. Atop this hill stood the great god Atum who spoke creation into being by drawing on the power of Heka, the god of magic. Heka was thought to pre-date creation and was the energy which allowed the gods to perform their duties. Magic informed the entire civilization and Heka was the source of this creative, sustaining, eternal power. In another version of the myth, Atum creates the world by first fashioning Ptah, the creator god who then does the actual work. Another variant on this story is that Ptah first appeared and created Atum. Another, more elaborate, version of the creation story has Atum mating with his shadow to create Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture) who then go on to give birth to the world and the other gods.

From this original act of creative energy came all of the known world and the universe. It was understood that human beings were an important aspect of the creation of the gods and that each human soul was as eternal as that of the deities they revered. Death was not an end to life but a re-joining of the individual soul with the eternal realm from which it had come. The Egyptian concept of the soul regarded it as being comprised of nine parts: the Khat was the physical body; the Ka one’s double-form; the Ba a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens; Shuyet was the shadow self; Akh the immortal, transformed self, Sahu and Sechem aspects of the Akh; Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil; Ren was one’s secret name.

An individual’s name was considered of such importance that an Egyptian’s true name was kept secret throughout life and one was known by a nickname. Knowledge of a person’s true name gave one magical powers over that individual and this is among the reasons why the rulers of Egypt took another name upon ascending the throne; it was not only to link oneself symbolically to another successful pharaoh but also a form of protection to ensure one’s safety and help guarantee a trouble-free journey to eternity when one’s life on earth was completed. According to the historian Margaret Bunson:

"Eternity was an endless period of existence that was not to be feared by any Egyptian. The term `Going to One’s Ka’ (astral being) was used in each age to express dying. The hieroglyph for a corpse was translated as `participating in eternal life’. The tomb was the `Mansion of Eternity’ and the dead was an Akh, a transformed spirit.

The famous Egyptian mummy (whose name comes from the Persian and Arabic words for `wax’ and `bitumen’, muum and mumia) was created to preserve the individual’s physical body (Khat) without which the soul could not achieve immortality. As the Khat and the Ka were created at the same time, the Ka would be unable to journey to The Field of Reeds if it lacked the physical component on earth. The gods who had fashioned the soul and created the world consistently watched over the people of Egypt and heard and responded to, their petitions. A famous example of this is when Ramesses II was surrounded by his enemies at the Battle of Kadesh (1274 B.C.) and, calling upon the god Amun for aid, found the strength to fight his way through to safety. There are many far less dramatic examples, however, recorded on temple walls, stele, and on papyrus fragments.

Papyrus (from which comes the English word `paper’) was only one of the technological advances of the ancient Egyptian culture. The Egyptians were also responsible for developing the ramp and lever and geometry for purposes of construction, advances in mathematics and astronomy (also used in construction as exemplified in the positions and locations of the pyramids and certain temples, such as Abu Simbel), improvements in irrigation and agriculture (perhaps learned from the Mesopotamians), ship building and aerodynamics (possibly introduced by the Phoenicians) the wheel (brought to Egypt by the Hyksos) and medicine.

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (circa 1800 B.C.) is an early treatise on women’s health issues and contraception and the Edwin Smith Papyrus (circa 1600 B.C.) is the oldest work on surgical techniques. Dentistry was widely practised and the Egyptians are credited with inventing toothpaste, toothbrushes, the toothpick, and even breath mints. They created the sport of bowling and improved upon the brewing of beer as first practised in Mesopotamia. The Egyptians did not, however, invent beer. This popular fiction of Egyptians as the first brewers stems from the fact that Egyptian beer more closely resembled modern-day beer than that of the Mesopotamians.

Glass working, metallurgy in both bronze and gold, and furniture were other advancements of Egyptian culture and their art and architecture are famous world-wide for precision and beauty. Personal hygiene and appearance was valued highly and the Egyptians bathed regularly, scented themselves with perfume and incense, and created cosmetics used by both men and women. The practice of shaving was invented by the Egyptians as was the wig and the hairbrush. By 1600 B.C. the water clock was in use in Egypt, as was the calendar. Some have even suggested that they understood the principle of electricity as evidenced in the famous Dendera Light engraving on the wall of the Hathor Temple at Dendera. The images on the wall have been interpreted by some to represent a light bulb and figures attaching said bulb to an energy source. This interpretation, however, has been largely discredited by the academic community.

In daily life, the Egyptians seem little different from other ancient cultures. Like the people of Mesopotamia, India, China, and Greece, they lived, mostly, in modest homes, raised families, and enjoyed their leisure time. A significant difference between Egyptian culture and that of other lands, however, was that the Egyptians believed the land was intimately tied to their personal salvation and they had a deep fear of dying beyond the borders of Egypt. Those who served their country in the army, or those who travelled for their living, made provision for their bodies to be returned to Egypt should they be killed. It was thought that the fertile, dark earth of the Nile River Delta was the only area sanctified by the gods for the re-birth of the soul in the afterlife and to be buried anywhere else was to be condemned to non-existence.

Because of this devotion to the homeland, Egyptians were not great world-travellers and there is no `Egyptian Herodotus’ to leave behind impressions of the ancient world beyond Egyptian borders. Even in negotiations and treaties with other countries, Egyptian preference for remaining in Egypt was dominant. The historian Nardo writes, "Though Amenophis III had joyfully added two Mitanni princesses to his harem, he refused to send an Egyptian princess to the sovereign of Mitanni, because, `from time immemorial a royal daughter from Egypt has been given to no one.’ This is not only an expression of the feeling of superiority of the Egyptians over the foreigners but at the same time and indication of the solicitude accorded female relatives, who could not be inconvenienced by living among `barbarians’."

Further, within the confines of the country people did not travel far from their places of birth and most, except for times of war, famine or other upheaval, lived their lives and died in the same locale. As it was believed that one’s afterlife would be a continuation of one’s present (only better in that there was no sickness, disappointment or, of course, death), the place in which one spent one’s life would constitute one’s eternal landscape. The yard and tree and stream one saw every day outside one’s window would be replicated in the afterlife exactly. This being so, Egyptians were encouraged to rejoice in and deeply appreciate their immediate surroundings and to live gratefully within their means. The concept of ma’at (harmony and balance) governed Egyptian culture and, whether of upper or lower class, Egyptians endeavoured to live in peace with their surroundings and with each other.

Among the lower classes, homes were built of mud bricks baked in the sun. The more affluent a citizen, the thicker the home; wealthier people had homes constructed of a double layer, or more, of brick while poorer people’s houses were only one brick wide. Wood was scarce and was only used for doorways and window sills (again, in wealthier homes) and the roof was considered another room in the house where gatherings were routinely held as the interior of the homes were often dimly lighted.

Clothing was simple linen, un-dyed, with the men wearing a knee-length skirt (or loincloth) and the women in light, ankle-length dresses or robes which concealed or exposed their breasts depending on the fashion at a particular time. It would seem that a woman’s level of undress, however, was indicative of her social status throughout much of Egyptian history. Dancing girls, female musicians, and servants and slaves are routinely shown as naked or nearly naked while a lady of the house is fully clothed, even during those times when exposed breasts were a fashion statement.

Even so, women were free to dress as they pleased and there was never a prohibition, at any time in Egyptian history, on female fashion. A woman’s exposed breasts were considered a natural, normal, fashion choice and was in no way deemed immodest or provocative. It was understood that the goddess Isis had given equal rights to both men and women and, therefore, men had no right to dictate how a woman, even one’s own wife, should attire herself. Children wore little or no clothing until puberty.

Marriages were not arranged among the lower classes and there seems to have been no formal marriage ceremony. A man would carry gifts to the house of his intended bride and, if the gifts were accepted, she would take up residence with him. The average age of a bride was 13 and that of a groom 18-21. A contract would be drawn up portioning a man’s assets to his wife and children and this allotment could not be rescinded except on grounds of adultery (defined as sex with a married woman, not a married man). Egyptian women could own land, homes, run businesses, and preside over temples and could even be pharaohs (as in the example of Queen Hatshepsut, 1479-1458 B.C.) or, earlier, Queen Sobeknofru, circa 1767-1759 B.C.).

The historian Thompson writes, "Egypt treated its women better than any of the other major civilizations of the ancient world. The Egyptians believed that joy and happiness were legitimate goals of life and regarded home and family as the major source of delight.” Because of this belief, women enjoyed a higher prestige in Egypt than in any other culture of the ancient world.

While the man was considered the head of the house, the woman was head of the home. She raised the children of both sexes until, at the age or four or five, boys were taken under the care and tutelage of their fathers to learn their profession (or attend school if the father’s profession was that of a scribe, priest, or doctor). Girls remained under the care of their mothers, learning how to run a household, until they were married. Women could also be scribes, priests, or doctors but this was unusual because education was expensive and tradition held that the son should follow the father's profession, not the daughter. Marriage was the common state of Egyptians after puberty and a single man or woman was considered abnormal.

The higher classes, or nobility, lived in more ornate homes with greater material wealth but seem to have followed the same precepts as those lower on the social hierarchy. All Egyptians enjoyed playing games, such as the game of Senet (a board game popular since the Pre-Dynastic Period, circa 5500-3150 B.C.) but only those of means could afford a quality playing board. This did not seem to stop poorer people from playing the game, however; they merely played with a less ornate set.

Watching wrestling matches and races and engaging in other sporting events, such as hunting, archery, and sailing, were popular among the nobility and upper class but, again, were enjoyed by all Egyptians in as much as they could be afforded (save for large animal hunting which was the sole provenance of the ruler and those he designated). Feasting at banquets was a leisure activity only of the upper class although the lower classes were able to enjoy themselves in a similar (though less lavish) way at the many religious festivals held throughout the year.

Swimming and rowing were extremely popular among all classes. The Roman writer Seneca observed common Egyptians at sport the Nile River and described the scene: "The people embark on small boats, two to a boat, and one rows while the other bails out water. Then they are violently tossed about in the raging rapids. At length, they reach the narrowest channels…and, swept along by the whole force of the river, they control the rushing boat by hand and plunge head downward to the great terror of the onlookers. You would believe sorrowfully that by now they were drowned and overwhelmed by such a mass of water when, far from the place where they fell, they shoot out as from a catapult, still sailing, and the subsiding wave does not submerge them, but carries them on to smooth waters."

Swimming was an important part of Egyptian culture and children were taught to swim when very young. Water sports played a significant role in Egyptian entertainment as the Nile River was such a major aspect of their daily lives. The sport of water-jousting, in which two small boats, each with one or two rowers and one jouster, fought each other, seems to have been very popular. The rower (or rowers) in the boat sought to strategically maneuver while the fighter tried to knock his opponent out of the craft. They also enjoyed games having nothing to do with the river, however, which were similar to modern-day games of catch and handball.

Gardens and simple home adornments were highly prized by the Egyptians. A home garden was important for sustenance but also provided pleasure in tending to one’s own crop. The labourers in the fields never worked their own crop and so their individual garden was a place of pride in producing something of their own, grown from their own soil. This soil, again, would be their eternal home after they left their bodies and so was greatly valued. A tomb inscription from 1400 B.C. reads, “May I walk every day on the banks of the water, may my soul rest on the branches of the trees which I planted, may I refresh myself under the shadow of my sycamore” in referencing the eternal aspect of the daily surroundings of every Egyptian. After death, one would still enjoy one’s own particular sycamore tree, one’s own daily walk by the water, in an eternal land of peace granted to those of Egypt by the gods they gratefully revered. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

REVIEW: The The New York Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection of ancient Egyptian art consists of approximately 26,000 objects of artistic, historical, and cultural importance, dating from the Paleolithic to the Roman period (circa 300,000 B.C. to 4th century A.D.). More than half of the collection is derived from the Museum's 35 years of archaeological work in Egypt, initiated in 1906 in response to increasing Western interest in the culture of ancient Egypt. Virtually the entire collection is on display in the Lila Acheson Wallace Galleries of Egyptian Art, with objects arranged chronologically over 39 rooms.

Overall, the holdings reflect the aesthetic values, history, religious beliefs, and daily life of the ancient Egyptians over the entire course of their great civilization. The collection is particularly well known for the Old Kingdom mastaba (offering chapel) of Perneb (circa 2450 B.C.); a set of Middle Kingdom wooden models from the tomb of Meketre at Thebes (circa 1990 B.C.); jewelry of Princess Sit-hathor-yunet of Dynasty 12 (circa 1897–1797 B.C.); royal portrait sculpture of Dynasty 12 (ca. 1991–1783 B.C.); and statuary of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut of Dynasty 18 (circa 1473–1458 B.C.). The department also exhibits its invaluable collection of watercolor facsimiles of Theban tomb paintings, most of which are copies produced between 1907 and 1937 by members of the Graphic Section of the Museum's Egyptian Expedition.

One of the most popular destinations in the Egyptian galleries is the Temple of Dendur in The Sackler Wing. Built about 15 B.C. by the Roman emperor Augustus, who had succeeded Cleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt, the temple was dedicated to the great goddess Isis and to two sons of a local Nubian ruler who had aided the Romans in their wars with the queen of Meroe to the south. Located in Lower Nubia, about 50 miles south of modern Aswan, the temple was dismantled to save it from the rising waters of Lake Nasser after the construction of the Aswan High Dam. It was presented to the United States as a gift from the Egyptian government in recognition of the American contribution to the international campaign to save the ancient Nubian monuments.

The Department of Egyptian Art was established in 1906 to oversee the Museum's already sizable collection of art from ancient Egypt. The collection had been growing since 1874 thanks to individual gifts from benefactors and acquisition of private collections (such as the Drexel Collection in 1889, the Farman Collection in 1904, and the Ward Collection in 1905), as well as through yearly subscriptions, from 1895 onward, to the Egypt Exploration Fund, a British organization that conducted archaeological excavations in Egypt and donated a share of its finds to subscribing institutions.