"The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire" by Michael Grant.

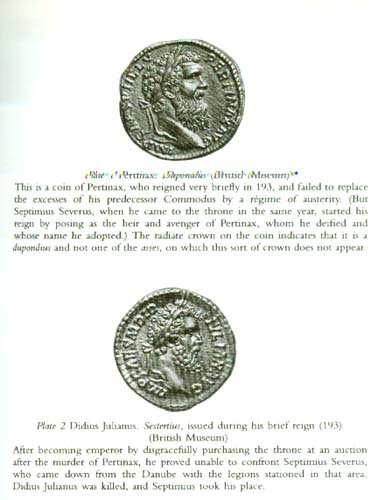

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with dustjacket. Publisher: Routledge (1996). Pages: 133. Size: 9 x 5¾ x ¾ inch; 1 pound.. Summary: “The Severans” analyses the colorful decline of the Roman Empire during the reign of the Severans, the first non-Italian dynasty. In his learned and exciting style, Michael Grant describes the foreign wars waged against the Alemanni and the Persians, and the remarkable personalities of the imperial family. Thus the reader encounters Julia Domna's alleged literary circle, or Elagabalus' curious private life - which included dancing in the streets, marrying a vestal virgin and smothering his enemies with rose petals. With its beautifully selected plate section, maps and extensive bibliography, this book will appeal to the student of ancient history as well as to the general reader. Michael Grant is one of the world's greatest writers on ancient history. His previous publications include: Art in the Roman Empire, Greek and Roman Historians and Who's Who in Classical Mythology all published by Routledge.

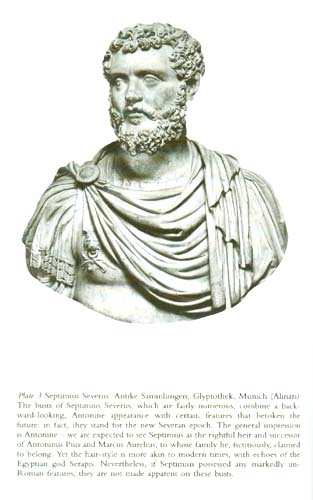

CONDITION: NEW. New hardcover w/dustjacket. Routledge (1996) 133 pages. [Published at $120.00]. Unblemished except for very faint shelfwear to dustjacket. Pages are pristine; clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Shelfwear to dustjacket is principally int he form of faint crinkling and a 1/8 inch closed (neatly mended) edge tear to the dustjacket spine head. Condition is entirely consistent with a new book from an open-shelf bookstore environment such as Barnes & Noble or B. Dalton (for instance) wherein new books might show faint signs of shelfwear, consequence of simply being shelved and re-shelved. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! #4179e.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

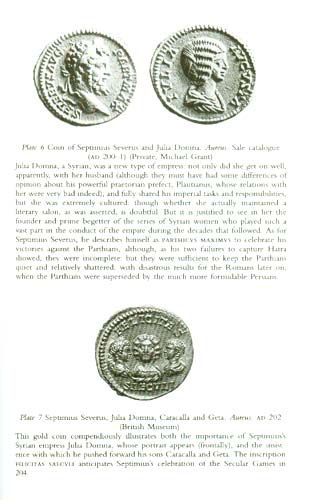

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: From one of the world's greatest writers on ancient history, a new work that explores the colorful decline of the Roman Empire during the reign of the Severans, the first non-Italian dynasty, whose reign extends through nine emperors, from 193 to 235 C.E, from Septimius Severus to Severus Alexander, and including the reigns of Caracalla and Elagabalus. Using the highly praised, accessible style that is his trademark, Michael Grant describes the foreign wars waged against the Alemanni and the Persians; the remarkable personalities of the imperial family; the unprecedented role of women and lawyers; as well as the major developments in art, architecture, the novel and religion during this era.

Highlights of "The Severans" include encounters with Julia Domna's alleged literary circle and Elagablus's curious private life (exemplified by acts such as dancing in the streets, marrying a Vestal Virgin, and smothering his enemies with rose petals). With its extensive selection of illustrations, maps, and extensive bibliography, “The Severans” will appeal to the student of ancient history as well as to all generally-interested readers of classical history.

REVIEW: This work analyzes the colorful decline of the Roman Empire during the reign of the Severans, the first non-Italian dynasty. It describes the foreign wars waged against the Alemanni and the Persians, and the remarkable personalities of the imperial family. The reader encounters Julia Domna's alleged literary circle, or Elagabalus' curious private life - which included dancing in the streets, marrying a vestal virgin and smothering his enemies with rose petals. With its plate section, maps and bibliography, this book should appeal to the student of ancient history as well as to the general reader.

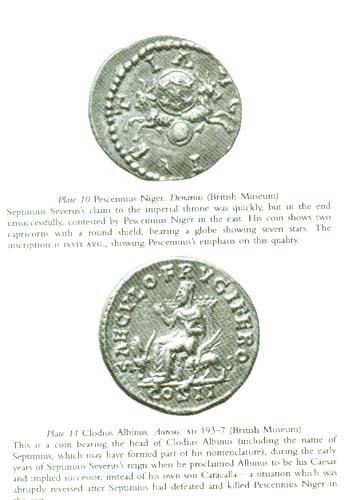

REVIEW: Michael Grant is one of the world's greatest writers on ancient history. He was formerly a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, Professor of Humanities at the University of Edinburgh and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Khartoum and the Queen's University of Belfast. He has published over fifty books.

REVIEW: Michael Grant is one of the world's greatest writers on ancient history. His previous publications include: Art in the Roman Empire, Greek and Roman Historians and Who's Who in Classical Mythology all published by Routledge.

REVIEW: Michael Grant (1914–2004) was an English classicist, numismatist, and author of numerous popular books on ancient history. His 1956 translation of Tacitus's Annals of Imperial Rome remains a standard of the work. Having studied and held a number of academic posts in the United Kingdom and the Middle East, he retired early to devote himself fully to writing. He once described himself as "one of the very few freelancers in the field of ancient history: a rare phenomenon". As a populariser, his hallmarks were his prolific output and his unwillingness to oversimplify or talk down to his readership. He published over 70 works.

Grant was born in London, the son of Col. Maurice Grant who served in the Boer War and later wrote part of its official history. Young Grant attended Harrow and read classics (1933–37) at Trinity College, Cambridge. His speciality was academic numismatics. His research fellowship thesis later became his first published book – From Imperium to Auctoritas (1946), on Roman bronze coins. Over the next decade he wrote four books on Roman coinage; his view was that the tension between the eccentricity of the Roman emperors and the traditionalism of the Roman mint made coins (used as both propaganda and currency) a unique social record.

During World War II, Grant served for a year as an intelligence officer in London after which he was assigned (1940) as the UK's first British Council representative in Turkey. In this capacity he was instrumental in getting his friend, the eminent historian Steven (later Sir Steven) Runciman, his position at Ankara University. While in Turkey, he also married Anne-Sophie Beskow (they had two sons). At war's end, the couple returned to the UK with Grant's collection of almost 700 Roman coins (now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge).

After a brief return to Cambridge, Grant applied for the vacant chair of Humanity (Latin) at Edinburgh University which he held from 1948 until 1959. During a two-year (1956–58) leave of absence he also served as vice-chancellor (president) of the University of Khartoum – upon his departure, he turned the university over to the newly independent Sudanese government. He was then vice-chancellor of Queen's University of Belfast (1959–66), after which he pursued a career as a full-time writer. According to his obituary in The Times he was "one of the few classical historians to win respect from [both] academics and a lay readership".

Immensely prolific, he wrote and edited more than 70 books of nonfiction and translation, covering topics from Roman coinage and the eruption of Mount Vesuvius to the Gospels. He produced general surveys of ancient Greek, Roman and Israelite history as well as biographies of giants such as Julius Caesar, Herod the Great, Cleopatra, Nero, Jesus, St. Peter and St. Paul. As early as the 1950s, Grant's publishing success was somewhat controversial within the classicist community. According to The Times:

"Grant's approach to classical history was beginning to divide critics. Numismatists felt that his academic work was beyond reproach, but some academics balked at his attempt to condense a survey of Roman literature into 300 pages, and felt (in the words of one reviewer) that 'even the most learned and gifted of historians should observe a speed-limit'. The academics would keep cavilling, but the public kept buying." From 1966 until his death, Grant lived with his wife in Gattaiola, a village near Lucca in Tuscany. His autobiography, My First Eighty Years, appeared in 1994.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

List of Maps.

List of Illustrations.

Acknowledgements for Illustrations.

Introduction.

1. Septimus Severus and the Struggle for Power.

2. The Praetorians and their Prefects: Plautianus.

3. The Gestures of Septimius.

4. The Successors.

5. The Provinces and Italy: the Constitutio Antoniniana.

6. The Army: the Military Monarchy.

7. Finance.

8. The Syrian Women.

9. The Lawyers.

10. The Novel: Longus.

11. Art and Architecture.

12. Paganism and Christianity.

Epilogue.

Appendix.

The Literary Sources.

List of Emperors.

Abbreviations.

Notes.

Further Reading.

Index.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Michael Grant was a classicist with a reputation for writing short and popular, but comprehensive, books on Rome and this volume from 1996 is no exception. He condenses the fifty event filled years of the Severan dynasty (and the brief reign of Macrinus) into under ninety pages. The structure of the book is thematic rather than narrative, and chapters on finance, literature and art give perspectives often forgotten in more story-driven popular history. [Oxford University].

REVIEW: Routledge has given us another book from Michael Grant Publications Ltd. The natural person who lurks under this entity in which the copyright vests might consider changing its name to Michael Grant Industries Ltd. The author's book tally is in the fifties, a remarkable figure even for a scholar regarded essentially as a populariser, 'perhaps the greatest populariser we have known in this century', as a reviewer of an earlier Grant work put it.

This volume is a kind of sequel to Grant's 1994 study of the Antonines. A brief introduction, which begins as if the book is indeed only a section of a longer history, gives an overview of the Severan period and directs our attention to the topics on which the author is going to focus. The first four chapters are devoted to an outline of the political history and personalities of the dynasty from Septimius Severus to Severus Alexander, with the praetorian guard and prefecture highlighted in chapter 2.

The remaining chapters (5-12) proceed thematically, covering provincial policy and the Constitutio Antoniniana, the army, finance, the influential women of the dynasty, jurists (papinian, Paulus, Ulpian), the Greek novel (with focus on Longus), art and architecture, and paganism and Christianity. There is a short epilogue, an appendix on the literary sources, a bibliography, and a general index. [University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg].

REVIEW: The book has provided a comprehensive treatment of one of the less well-known periods of Roman history, a valuable introduction for the specialist in other branches of the classics, the student, and the educated general reader alike. [National University of Ireland].

REVIEW: Describes and analyzes the colorful decline of the Roman empire during the reign of the Severans, the first non-Italian dynasty, in an entertaining and accessible style. Looks at foreign wars waged against the Alemanni and the Persians, and the personalities of the imperial family. Includes black and white illustrations. For students of ancient history and general readers. [Book News].

REVIEW: Michael Grant, one of our finest and most prolific writers on the ancient world takes on the first non-Italian Dynasty, a nine-emperor rule that extended from 193 to 235 A.D....the book is enlivened by many maps and illustrations. [Toronto Globe and Mail].

REVIEW: Remarkably well illustrated...Appealing to the general reader, it has also much to offer to the serious student of Roman history. [The Journal of Indo-European Studies].

REVIEW: This slim volume is a logical follow-up to Grant's recent "The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition" London & New York, 1994) and is very much modeled on the same pattern. Although it does not follow the earlier book's straightforward division into two halves (the first dealing with persons, the second with movements), of its twelve chapters, the first five might be described as narrative, he last seven as analytical. However, The Severans departs from, and improves on, the format of its predecessor by abandoning its clumsy system of bald References, followed by Notes referring to sections underlined in the main text, in favour of returning to endnotes of a more traditional kind.

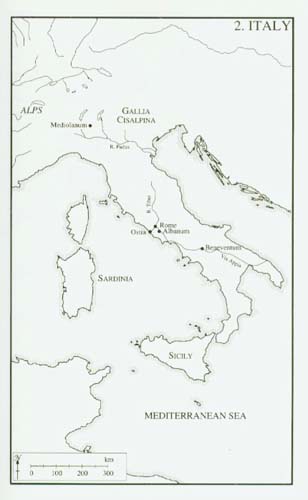

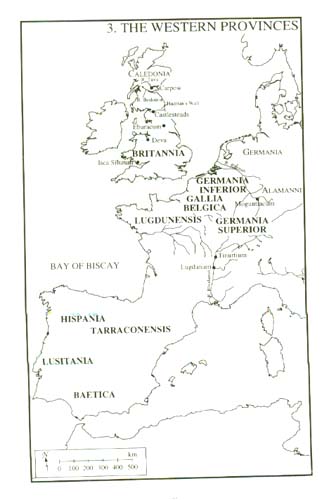

With 7 maps and 32 black and white plates, the earlier volume's lavish standard of cartographic and photographic llustration s maintained; though in comparison the maps are somewhat lacking in quality and elegance. Imperial portraiture dominates the plates, amongst which coin obverses are heavily represented, attesting to the author's original incarnation as a numismatic historian. With these maps and pictures the publishers have probably correctly targeted their intended audience, the student of ancient history as well as the general reader, as the blurb on the inside flap of the dust-jacket claims.

The justification of the subtitle is to be found in Grant's chapters on the army and finance. Here he is right to emphasize the link between Severus's dependence on the legions in bringing him to power, the spiralling costs of military expenditure to ensure their loyalty, and the various devices to optimize revenue (such as the grant of universal Roman citizenship) employed by him and his successors. Grant is also right to highlight the now open acknowledgement of the role of the military in maintaining the emperor's position. Those, such as Macrinus or Severus Alexander, who failed to establish or maintain a rapport with the troops were doomed. [University College London].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Stopping the rot, the restarting it. In the aftermath of the strange reign of Commodus, the odd son of Marcus Aurelius came a period of chaos. This is the period which begins Gibbon's Decline and Fall. Into this breach stepped the Severan dynasty which managed to halt the problems that plagued the empire, at least the founder of this dynasty, Lucius Septimius Severus, did so. His successors, though not plagued by outward threats managed to waste any good reputation that the office of emperor managed to garner through increasingly strange and bizarre actions. The women of the Severan dynasty were sometimes ever worse.

Septimius Severus was acclaimed as the emperor by his troops in 193 and like so many generals managed to make himself emperor by eliminating his rivals. The next step was to see the succession through. This he proposed doing by promoting his sons, Caracalla (of the elaborate baths fame) and Geta. Caracalla, as was also often the case among late Roman emperors, was a psychopath and had his brother killed. Caracalla himself was soon eliminated and without an heir leading to another successful general to claim the throne. This emperor was Macrinus and he reigned for one year only. This was due in large measure to the women of the Severan dynasty.

When Septimius Severus became emperor, his Syrian born wife, Julia Domna became empress, and not just consort. Though they presumably clashed over the Praetorian Prefect, Plautanus. With her came her exotic family including her sister, Julia Maesa and other female relations. The succession of Macrinus was a clue to mount a coup to place her strange grandson, Elagabalus on the throne.

The oddities of Elagablus are so strange that it is a testimony to the skill of the Syrian women that they were able to put over a sexually confused teen ager as the most powerful ruler in the west for as long as they did. Eventually even they gave up and promoted the candidacy of his cousin Alexander as heir. When this was accomplished, Elagablus was eliminated in the time honored Roman way, political murder.

Julia Mamaea, the mother of Alexander and the daughter of Julia Maesa was the real power behind the throne. Severus Alexander as he was styled faced barbarian invasions which luckily did not occur during the reigns of his more colorful relations who were clearly not up to the job. Despite an attempt to impose stronger discipline on the army, rigid economy on the court and deference to the senate, both Alexander and Julia Mamaea were deposed in 235 in favor of Maximinus, yet another general in string of them which would follow on up through the chaotic age that followed.

In a brief period, Grant manages to describe the triumphs and trials that the Severans inflicted on the Roman world. While not as distinguished as the "Good Emperors" who came before, they are historically important and represent a stable period of about 40 years before the real rot came to the political life of the Roman world and military power eclipsed all other sources of legitimacy. This is well worth reading as an introduction to the period.

REVIEW: Lesser Known Ancient History. Michael Grant has produced a short, concise review of the emperors following the reigns of the famous Marcus Aurelius and his ner-do-well son Commodus. This period begins the slide to destruction of the Roman Empire in the west. After much strife and civil war, Septimus Severus founds his own brief "dynasty" and helps the empire temporarily recover.

This period has its' share of colorful characters and high intrigue. Septimius' son and future emperor Caracalla was a brutal terror to deal with, and even approved a bust of himself scowling in defiance and malice. While a nephew, Elagabalus, was an outrageously gay and neglectful ruler who was murdered only four years after becoming emperor. A feast for Hollywood, which unfortunately remains fixed on the periods of Caesar and his immediate followers and the above mentioned Aurelius and son.

This is a good, short read. The book is a brief, to the point narrative, packed with the only verifiable facts we have of this period and boasts many photos and coin images of the principle characters. Grant is straight-forward and direct. A good start for any enthusiast of this period of Roman history.

REVIEW: This is a very short survey of the Severan emperors, great for readers looking for a brief overview. The author does an excellent job of situating the dynasty into broader Roman history. This is also a useful supplement for readers looking to remedy the inadequacies of the Historia Augusta. Readers should also see Anthony Birley's biography of Septimius Severus for a more in-depth look at the Year of the Five Emperors and the beginning of the Severan dynasty. Particularly interesting are the parts about religion and the rise of monotheism, in the private cult of Mithras and the more public cult of the Sun. Mr. Grant does a fine job of placing these cults in the context of the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

REVIEW: This book filled in some gaps in my knowledge, as my knowledge of the Roman Empire does not extend much later than 200 A.D. This was a short book without much detail or narrative structure, but that is because the ancient sources reveal so little about this period. The period evidently saw a decline in literary output and quality as well as in military, political, and economic power. It is amazing that the empire limped along for over two hundred years after the Sevaran dynasty. The decline of the Roman Empire has provoked many analogies, but the empire lasted far longer than the United States has lasted so far, so the jury of history is still out.

REVIEW: This book covers the Severan Dynasty, which was pivotal to the fate of the Roman Empire. The problem with this period is that the most complete source, the Historia Augusta (part of which has been published as Penguin's "Lives of the Later Caesars" , as a kind of sequel to "Suetonius") is badly flawed and completely unreliable. So this leaves us Cassius Dio, Herodian and a few other ancient authors. "The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition" is also worth a read, as most of his books are.

REVIEW: In "The Severans", historian Michael Grant recounts the period when Rome began its fatal transition into a military monarchy where an ever-growing and ever-consuming army set up and replaced rulers at will. In twelve short (the Epilogue begins on page 86) chapters, Grant balances the conquests and policies of the Severan emperors, Septimius and his relatives, with the rise (and fall) of the lawyers, the restoration (perhaps in form only) of the Senate, the establishment of Roman fiction, and the ongoing struggle of paganism with ascendant Christianity.

The book's most interesting insights center around the remarkable women of the Severan family, especially Septimius' second wife, Julia Domna, the mother of emperors Geta and Carcalla, and her sister Julia Maesa, the grandmother of two later, minor (both in age and accomplishment) emperors. Unfortunately, their chapter lasts a mere four pages, though in all fairness to the author, that is mostly because of a lack of suitable source material.

That lack of source material carries over into other areas as well, as a number of novelists are briefly explored, with Grant admitting that all but one probably fall into other periods. A similar treatment is given to the lawyers, whom we are informed, "exercised more influence on the future than anyone else of the time," yet only three are named and their works and ideas are covered all too briefly.

Those looking for a biographical dictionary of the important personalities and trends of the period will probably find "The Severans" worthwhile.

REVIEW: Michael Grant's book, "The Severans", covers a very short period of Roman history that, due to the lack of source materials, is usually left untouched. My only complaint about the writing style is that the work really needs to be read twice: once to get the general feel of the ideas presented, and a second time to follow all the references to chapters found later on in the book. I would recommend this book to anyone interested in Ancient Roman history.

REVIEW: Excellent! A companion piece to "Collapse & Recovery of the Roman Empire" tracing the history of the Severan Dynasty, with an emphasis on it's founder Septimius Severus.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

REVIEW: The Severan dynasty comprised the relatively short reigns of Septimius Severus (reigned 193–211 A.D.), Caracalla (reigned 211–17 A.D.), Macrinus (reigned 217–18 A.D.), Elagabalus (reigned 218–22 A.D.), and Alexander Severus (reigned 222–35 A.D.). Its founder, Septimius Severus, was a member of a leading native family of Leptis Magna in North Africa who allied himself with a prominent Syrian family by his marriage to Julia Domna. Their union, which gave rise to the imperial candidates of Syrian background, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus, testified to the broad political franchise and economic development of the Roman empire.

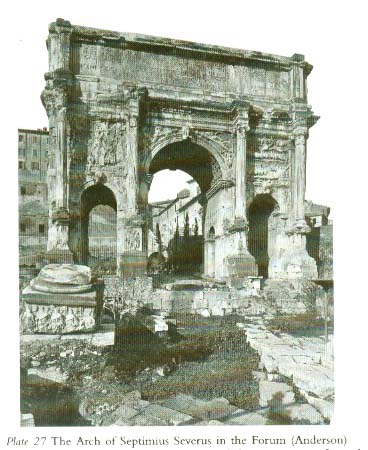

It was Septimius Severus who erected the famous triumphal arch in the Roman Forum, an important vehicle of political propaganda that proclaimed the legitimacy of the Severan dynasty and celebrated the emperor’s victories against Parthia in a lavishly sculpted historical narrative. As in most artistic achievements under the Severans, the monumental reliefs show a decisive break with classicism that presaged Late Antique and Byzantine works of art. At Leptis Magna, he renovated and embellished a number of monuments and built a grandiose new temple-forum-basilica complex on an unparalleled scale that befitted the birthplace of the new emperor.

Septimius cultivated the army with substantial remuneration for total loyalty to the emperor and substituted equestrian officers for senators in key administrative positions. In this way, he successfully broadened the power of the imperial administration throughout the empire. By abolishing the regular standing jury courts of Republican times, he was likewise able to transfer power to the executive branch of the government.

His son, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, nicknamed Caracalla, obliterated all distinctions between Italians and provincials, and enacted the Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 A.D., which extended Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Caracalla was also responsible for erecting the famous baths in Rome that bear his name. Their design served as an architectural model for later monumental public buildings. He was assassinated in 217 A.D. by Macrinus, who then became the first emperor who was not a senator.

The imperial court, however, was dominated by formidable women who arranged the succession of Elagabalus in 218 A.D., and Alexander Severus, the last of the line, in 222 A.D. In the last phase of the Severan principate, the power of the Senate was finally revived and a number of fiscal reforms were enacted. The fatal flaw of its last emperor, however, was his failure to control the army, eventually leading to mutiny and his assassination. The death of Alexander Severus signaled the age of the soldier-emperors and almost a half-century of civil war and strife. [New York Metropolitan Museum].

REVIEW: Domitian, the younger son of Vespasian, was the last emperor to have inherited the position from his father. Without surviving sons, themselves, all but one had chosen their successor by adoption. For the next eighty years, these so-called "adoptive" emperors (Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius) ruled Rome. It was such men, selected for their competence, rather than through hereditary succession, that permitted Rome to enjoy the happy condition of which Gibbon speaks. That felicitous time ended with Commodus.

Commodus (AD 180-192) was eighteen years old when he became emperor, the son of Marcus Aurelius and the younger Faustina, although so unlike his father that he popularly was thought to have been illegitimate. With his accession, says Cassius Dio, a senator and contemporary of many of the events which he records, "our history now descends from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust, as affairs did for the Romans of that day" (LXXII.36.4).

Indifferent to the affairs of government, Commodus gave himself over to the pleasures of the court, which led to a series of intrigues and miscarried conspiracies. His sister instigated an attempt on his life, but the assassin, instead of stabbing the emperor, wasted time declaring his intentions and so was seized. Afterwards, Commodus was all too willing to relinquish his responsibilities, first to Perennis, the praetorian prefect and then to the freedman Cleander, the court chamberlain. But, as their power increased, they both were executed in their turn and, says Dio, a new "Golden Age" proclaimed.

Commodus demanded deification as a god and identified himself with Hercules. The months of the year were renamed after his various titles, which he elaborated upon so as to have the requisite number. When, in AD 191, a disastrous fire destroyed the Temple of Peace ("the largest and most beautiful of all the buildings in the city," says Herodian) and the Temple of Vesta, exposing the sacred Palladium to public view as it was carried along the Sacra Via to safety by the Vestals, Commodus thought of himself as the second founder of Rome and officially renamed it Colonia Commodiana.

The emperor's megalomania extended to the amphitheater, as well, where he fought as a gladiator, in spite of the contempt in which that class was held. In September AD 192, he presented himself for the first time at the games. Senators were obliged to attend, and Dio tells of Commodus killing an ostrich and displaying the severed head in one hand and his bloody sword in the other, implying that he could treat them the same way. Such was the absurdity of the spectacle, the decapitated ostriches running around with their heads cut off, and the threat to their lives, says Dio, that he and the other senators had to chew the laurel leaves of their garlands to keep from laughing.

Both Dio and Herodian also were at the Plebeian Games later in November, when Commodus, presented himself as Hercules Venator (the Hunter). People came from all over Italy and the neighboring provinces, writes Herodian, to witness the spectacle of an emperor of Rome who "promised he would kill all the wild animals with his own hand and engage in gladiatorial combat with the stoutest of the young men." And, from the safety of a raised enclosure, kill he did: lions and bears (a hundred of them), leopards, deer and gazelle, a tiger, a hippopotamus, and an elephant. Animals wild and domestic, all were slaughtered in this mockery of the hunt (venatio). An indication of the expense and extravagance of such a spectacle is that it would be more than sixteen hundred years before another hippopotamus was seen in Europe.

For the new year, writes Dio, Commodus planned to kill the consuls-elect and then, dressed as a gladiator, present himself to the people of Rome as consul in their place. When, says Herodian, on New Year's Eve AD 192, the night before he was to appear as a secutor, Marcia, the emperor's favorite concubine, discovered her own name and those of Eclectus, the chamberlain, and Laetus, the praetorian prefect, on the proscription list, they plotted to save themselves and had Commodus strangled in his bath.

So died the last of the Antonine emperors, "a greater curse to the Romans," according to Dio, "than any pestilence or any crime." Word was sent to Pertinax, the city prefect and likely a member of the conspiracy. It was not yet midnight when he hurried to the praetorian camp, where the guard shouted their acclamation, and then to the Senate house. The Historia Augusta records the Senate's angry litany of denunciation at the news of Commodus' death: "He that killed all, let him be dragged with the hook, he that killed persons of all ages, let him be dragged with the hook, he that killed both sexes, let him be dragged with the hook, he that did not spare his own blood, let him be dragged with the hook, he that plundered temples, let him be dragged with the hook, he that destroyed testaments, let him be dragged with the hook, he that plundered the living, let him be dragged with the hook!"

At age sixty-six, Pertinax, the son of a former slave and once a grammarian, was emperor. But, says Dio, he "failed to comprehend...that one cannot with safety reform everything at once, and that the restoration of a state, in particular, requires both time and wisdom" (LXXIV.10). Changing too much, too soon, he alienated both the praetorian guard, which feared the loss of privileges granted by Commodus, and the palace administration, which he blamed for the shortage in the imperial treasury. There was an attempt to replenish the funds squandered by Commodus, and even the jeweled weapons and golden helmets that he had used in the arena were auctioned off. But the measures he introduced were unpopular and there were several coup attempts. Finally, at the instigation of Laetus, a contingent of soldiers confronted the old man, who tried in vain to reason with them. Shouting "The soldiers have sent you this sword," says Dio, one of the men struck him down. As he covered his head with his toga and said a prayer, Pertinax was stabbed to death and his head stuck on a spear. He had ruled for eighty-seven days.

With no obvious successor, the praetorian guard now offered the position of emperor to the highest bidder. Two candidates presented themselves at their camp, each vying to outbid the other: Flavius Sulpicianus, the city prefect and father-in-law of the murdered Pertinax, and Didius Julianus, a wealthy member of the Senate. The bidding continued until Julianus offered a donative of 25,000 sestertii per man. Fearful of revenge were Sulpicianus made emperor, the praetorians chose Julianus, who, mindful of what had happened to his predecessor and aware of his own vulnerability, "passed," says the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, "the first night in continual wakefulness, disquieted by such a fate."

Unpopular with the people, who openly demonstrated against him the next day in the Circus Maximus, and with the Senate, Julianus soon lost the support of the praetorian guard, as well, when it became apparent that he would not be able to pay the extravagant bribe he had offered them. Nor was there support in the provinces, where, within two weeks of Pertinax's death, the frontier legions began to proclaim their own candidates: Pescennius Niger, governor of Syria; Clodius Albinus, governor of Britannia; and Septimius Severus, governor of Upper Pannonia on the Danube. As the Scriptores Historiae Augustae said of the last Severan emperor, so it could be said of the first: "And thus were sown the seeds of civil wars, in which it necessarily happened that soldiers enlisted to fight against a foreign foe fell at the hands of their brothers." A debilitating civil war was about to begin, as the legions of Rome fought one another for control of the empire.

Acclaimed emperor at Carnuntum, the provincial capital, Severus marched on Rome as the avenger of Pertinax. Albinus was offered the title of "Caesar," with its prospect of succession, to assure his neutrality, while Niger fatally delayed in Antioch. Julianus had the Senate declare Severus a public enemy, issued coins proclaiming himself ruler of the world, and did what he could to oppose him. But the praetorians, who were set to digging fortifications, avoided the work, and the elephants, conscripted from the arena, proved ineffectual. Senatorial envoys were sent but found it more prudent to change sides; assassins were dispatched, but Severus was too closely guarded. According to the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, a deputation of Vestal Virgins even was considered.

Julianus sought to appease Severus by putting both Marcia and Laetus to death and, in a last, desperate move, even asked the Senate to declare Severus joint ruler. It all was to no avail; the praetorian prefect who conveyed the offer was put to death. With Severus advancing, the Senate moved that Julianus be deposed and Septimius Severus (AD 193-211) proclaimed emperor. The soldier sent to carry out the sentence found Julianus in the palace, says Herodian, "alone and deserted by everyone" and killed him "amid a shameful scene of tears." Didius Julianus had ruled only sixty-six days.

Severus was set to enter Rome in triumph. But, before he did, he had the praetorians summoned to parade outside the city, ordering them to leave their weapons behind. Surrounded by his own men, Severus berated the guard for what they had done. Those who had taken part in the assassination of Pertinax were executed and the rest banished from within a hundred miles of Rome. For over two centuries, from the time of Augustus, the largely Italian praetorian guard had been the elite of the army and enjoyed a disproportionate influence on the politics of Rome. Now it was to be recruited from the provinces and the legions loyal to the emperor. It never again would be so powerful.

Having ordered an elaborate state funeral for the deified Pertinax, Severus, after less than a month in the city, turned his attention to his rivals. For the next four years (AD 193-197), wars of succession were fought across the empire. In AD 194, Niger's army was defeated in a decisive battle on the plain near Issus, where Alexandria had defeated Darius more than five hundred years before, and Niger beheaded as he fled toward Antioch. That future governors should not have the same aspirations, Syria was divided into two provinces. (In time, Britain, too, would be split, with London and York as capitals of the south and north.) Then, consolidating Niger's legions with his own, Severus led them in retaliation against the Parthian vassal states in Mesopotamia that had supported his rival and, says Dio, "out of a desire for glory." The newly conquered territory was the first significant addition to the empire since the time of Trajan ninety years earlier. Byzantium, too, was besieged and its towered walls pulled down.

Late in AD 195, realizing that he would not succeed Severus, Albinus had himself proclaimed Augustus (emperor) and crossed over to Gaul. The Senate, in turn, declared him a public enemy. The populace was dismayed at the prospect of more civil war, and Dio relates what he, himself, heard in the Circus Maximus during the last chariot races before the Saturnalia. There, the plebs, safe in the anonymity of crowds that could number as many as 200,000, began to shout "How long are we to suffer such things...How long are we to be waging war?" Dio was amazed at the protest, that so many could utter "the same shouts at the same time, like a carefully trained chorus."

Designating his own son Antoninus (Caracalla or Caracallus, from the nickname given him because of the hooded cloak he wore) as Caesar and successor, Severus consolidated his power in Rome and marched against Albinus early in AD 197. In a closely fought battle on the outskirts of Lugdunum (Lyons), in which Severus was thrown from his horse, Albinus was defeated and committed suicide. Before the body was thrown into the river, together with those of his wife and sons, the corpse was trampled beneath the hooves of Severus' horse, and the head sent to Rome. When Severus returned to Rome, he ruthlessly persecuted the supporters of Niger and Albinus, both of whom had been popular with the Senate and people. Twenty-nine senators were put to death, including Sulpicianus, and command of the legions taken from the Senate and given to the knights (equites). The soldiers was awarded a stipend and allowed to live at home instead of in the barracks. The plebs were quieted with donations and more spectacles in the arena.

Within months, Severus departed Rome in a second war against the Parthians, sacking its capital, Ctesiphon, early in AD 198, "just as if," writes Dio, "the sole purpose of his campaign had been to plunder this place." He visited Palestine and Syria and toured Egypt, viewing the embalmed body of Alexander the Great, then sealed the tomb, says Dio, so that no one else would be able to look upon him. Severus returned to Rome in AD 202. While there, Caracalla, though only thirteen, married the daughter of his father's praetorian prefect, Plautianus, who, according to Dio, "had possessed the greatest power of all the men of my time, so that everyone regarded him with greater fear and trembling than the very emperors." Caracalla loathed both his wife and his father-in-law and threatened to have them both killed, which he did at the earliest opportunity. Severus stayed only a few weeks before leaving to visit his native Africa and the city of his birth, Lepcis Magna, upon which he bestowed many new buildings, including a new forum and basilica.

Severus was honored with an arch (AD 203), which was dedicated by the Senate on the emperor's decennalia (tenth anniversary), in celebration of his Parthian victories. The first major architectural addition to the Forum in eighty years, it marked the spot, says Herodian, where Severus had dreamed of Pertinax falling from his horse and the animal taking up Severus on his back for all to see. Diagonally opposite the Arch of Augustus, which also had been erected to celebrate a triumph over the Parthians, the new monument symbolically linked Rome's present emperor with her first.

In AD 207, says Herodian, there were reports of unrest in Britannia. "The barbarians of the province were in a state of rebellion, laying waste the countryside, carrying off plunder and wrecking almost everything." A decade earlier, Albinus had taken his legions to Gaul, leaving behind a weakened frontier, which the Caledonians and other tribes now exploited. The news promised new victories and an opportunity to get his two sons, Caracalla and Geta, who hated one another, out the city where, says Herodian, "they could return to their senses, leading a sober military life away from the luxurious delicacies of Rome."

In an audacious attempt, Dio records that Caracalla actually attempted to kill his father while on the march, but Severus did nothing, allowing "his love for his offspring to outweigh his love for his country; and yet in doing so he betrayed his other son, for he well knew what would happen." He was determined, once and for all, to conquer that troublesome isle, and there were some successes. But Severus died in York in AD 211, saying to his sons, reports Dio, to "be harmonius, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all other men." Caracalla, more interested in winning the allegiance of the soldiers than another punitive campaign, abandoned the territory that had been won and returned with his mother and brother and their father's ashes to Rome.

Caracalla now attempted to gain sole power, but Geta's claim was supported in the Senate and by their mother Julia Domna. The antagonism between the two brothers was intense and extended to their having separate entrances to the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill. There was talk that the empire, itself, should be divided, but their mother resisted, asking, says Herodian, whether they intended to divide her as well. Caracalla intended to murder Geta on the Saturnalia but could not. Eventually, he did find his chance and, enticing Julia to invite them both to meet with her in private to effect a reconciliation, had his brother killed in his mother's arms.

Now that Caracalla (AD 211-217) was emperor, all evidence of his dead brother Geta was systematically obliterated, including reference to him in the inscription on the Arch of Severus (where one still can see that the fourth line largely has been chiseled away). After mollifying the praetorian guard with a substantial raise in pay ("I am one of you," Dio reports him as saying, "and it is because of you alone that I care to live, in order that I may confer upon you many favors; for all the treasuries are yours"), in AD 212 he purged Rome of his brother's supporters, murdering some twenty thousand people. "Not a person survived," says Herodian, "who was even casually acquainted with Geta. Athletes and charioteers and performers of all the arts and dancing—everything that Geta enjoyed watching or listening to—were destroyed."

Guilty and uncomfortable in Rome, the next year Caracalla ventured against the Germans, went on to Ilium to visit the supposed tomb of Achilles (which he decorated with garlands and flowers), then to Antioch, and eventually to the tomb of Alexander the Great in Alexandria, the second largest city in the empire. There, inexplicably enraged, Caracalla ordered the slaughter of thousands of young men in that city. It was afterwards, in AD 217, after returning to Antioch to lead his legions against the Parthians, that Caracalla was assassinated. Standing by the side of the road to relieve himself, while the soldiers respectfully turned their backs, he was murdered by an officer of his bodyguard at the instigation of Macrinus, one of the praetorian prefects, who was fearful that his conspiracy against the emperor would be discovered. Feigning innocence of the deed, Macrinus (AD 217-218) was acclaimed emperor by the soldiers, the first not to have been a senator.

As despised as Caracalla was, he did leave behind one of the most famous legal measure of antiquity: the Constitutio Antoniniana, an edict dating from AD 212 that granted Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire, something that until then had been reserved only for Italians and a few select provincials. It also thereby subjected them to the obligations and taxes of Roman citizens, which were simultaneously doubled. If the measure did not seem significant at the time, it is because the distinction between citizen and non-citizen effectively had been replaced by that between honestiores and humiliores, rich and poor. Caracalla also built one of the most impressive monuments of imperial Rome: the Baths of Caracalla (Thermae Antoninianae). Sumptuously decorated and enclosed by gardens and open-air gymnasia, as well as an art collection that included the powerful Belvedere Torso and Farnese Hercules, the massive complex could accommodate sixteen hundred bathers, who became almost insignificant within its huge domes and soaring vaults. Of it can be said, as Martial had written of another emperor, "What worse than Nero, what better than Nero's baths."

Sick and hounded by Macrinus to leave Antioch, Julia Domna committed suicide not long after the death of her son. The daughter of the high priest of the sun god Elagabalus (Heliogabalus in Latin), her horoscope, writes Herodian, had foretold that she would marry a king, something that must have piqued the interest of Severus, who was intensely superstitious. A patron of writers and the philosopher Philostratus, whose Life of Apollonius was written at her request, Julia Domna was the first of the Syrian princesses who would exert such influence over the emperors of Rome. Her sister Julia Maesa was not as willing to accommodate Macrinus. Enlisting the support of one of the Syrian legions, she put forward her own grandchild to be acclaimed emperor. Macrinus, whose ignominious settlement with the Parthians had displeased the army, was defeated and killed. He had ruled little more than a year.

Another Severan now was emperor: Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, better known as Elagabalus or Heliogabalus (AD 218-222). He was no more than fourteen years old, and real power rested with his grandmother Julia Maesa and his mother Julia Soaemias. He and his family arrived from Syria in AD 219 to begin what was perhaps the most bizarre period of Roman history. A religious fanatic with exotic sexual proclivities, Elagabalus married a Vestal Virgin to symbolize the wedding between the Syrian and Roman pantheon, and built a magnificent temple, the Elagaballium, to the sun god Elagabalus, of which he was the hereditary priest and from whom he took his name. The most sacred symbols of Rome, including the Palladium and eternal flame, as well as those of Christians and Jews, were to be brought to the temple of Elagabalus, who would take precedence, says Dio, "even before Jupiter himself." Julia Maesa became increasingly apprehensive at such behavior. She had another grandson, the child of her other daughter Julia Mamaea, and they persuaded Elagabalus to adopt his cousin Alexander as Caesar and heir. When he came to regret the choice of his popular rival and tried to have him killed, Elagabalus and his mother were murdered, instead, and the emperor's body thrown into the Tiber.

Alexander Severus (AD 222-235), himself no more than fourteen years old, would rule under the jealous tutelage of his mother and grandmother for thirteen years. The old gods were restored to their sanctuaries and the Elagaballium rededicated to Jupiter Ultor (the Avenger). By now, the empire was under increasing threat. The resurgent Persians had overthrown the Parthians, Rome's traditional enemy, and in AD 230 invaded Mesopotamia, putting Syria, itself, at risk. While Alexander defended the eastern provinces, the German tribes took advantage of his absence and threatened the northern frontier. Alexander returned to Rome and then left for the Rhine. Prepared to negotiate and pay a subsidy to the Germans, Alexander contemptuously was murdered by his own soldiers in AD 235, "clinging," reports Herodian, "to his mother and weeping and blaming her for his misfortunes." The Severan emperors had ruled for forty-two years. The next half century would a time of chaos and despair, the darkest years in the history of Rome. [University of Chicago].

REVIEW: Lucius Septimius Severus who lived from 145/146 A.D. to 211 A.D. was a Roman Emperor of Libyan descent from Lepcis Magna, who reigned April 14, 193 A.D. to February 4, 211 A.D. Septimius came from a locally prominent Punic family who had a history of rising to senatorial as well as consular status. His first visit to Rome was around 163 AD during the reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. He was protected by his cousin Caius Septimius Severus and entered the Roman Senate in 170 AD. When his cousin went to Africa as a proconsul around 173-174 A.D., he chose L. Septimius Severus to be his legatus. L. Septimius married Paccia Marciana around 175 A.D. who had Punic origins like him; however, she died ten years later. When he was governor of Gaul and he lived in Lugdunum (Lyon), he married Julia Domna from Emesa (Syria) around 187 A.D. She was descended from a family of great priests of Eliogabal.

Septimius’ rise to emperor began with the murder of the dissolute ruler Commodus on the last day of 192 A.D. Commodus’ immediate successor, the well-respected if elderly Pertinax, was quickly made emperor afterwards. Pertinax’s actions as emperor, however, enraged members of the Praetorian Guard who disliked his efforts to enforce stricter discipline. Moreover, the inability of Pertinax to meet the Guard’s demands for back pay led to their revolt which ended in the emperor’s assassination. The Praetorian Guard then cynically proceeded to auction off the imperial throne to the highest bidder with the person willing to pay the most being promised the support of the Praetorian Guard and therefore the imperial throne. A rich and prominent senator, M. Didius Julianus, perhaps as a joke at first, proceeded to outbid all others at the auction and thus was proclaimed emperor by the Praetorians solely for the reason that he promised to pay them the most money. This affair caused considerable resentment among the population at Rome who openly denounced Julianus and the way in which he acquired the throne. Word of such unrest at Rome spread to the provinces and led to the emergence of three possible candidates to challenge Julianus’ rule.

After securing the loyalty of the sixteen legions of the Rhine and Danube to his cause, Septimius marched into Italy and was recognized by the Senate as emperor. The first candidate was Clodius Albinus, governor of Britain. The second was Pescennius Niger, governor of Syria, and the third was, of course, Septimius Severus who governed the province of Pannonia Superior on the Danube frontier. All three governors emerged as possible candidates mainly because each of them held provinces that were defended by three legions apiece. Not only did this give each governor a powerful military base of three legions but also ensured that the provinces adjacent to them would more often than not join in their cause if they decided to rise up and make a bid for imperial power. Both Albinus and Niger did so.

Septimius, in making his claim, had an edge over these two men. He had an advantage not only in terms of propaganda (Septimius had served with Pertinax previously and successfully portrayed himself as the ‘avenger of Pertinax,’ even adopting the slain emperor’s name) but also in terms of location as Pannonia was the closest of these provinces to Italy and Rome. To prevent a possible clash with Clodius Albinus in Britain, he secured Albinus’ support mainly by promising him the title of Caesar and thus a place in the imperial succession should Septimius be successful. After securing the loyalty of the sixteen legions of the Rhine and Danube to his cause, Septimius marched into Italy and, 60 miles outside of Rome, was recognized by the Senate as emperor. Julianus was executed, and Septimius was welcomed into Rome on 9 June 193 A.D. With his accession, the year 193 A.D. is known as ‘The Year of Five Emperors.’

Septimius quickly dissolved the existing Praetorian Guard and replaced it with a much larger bodyguard recruited from the Danubian legions under his command. To strengthen his rule in Italy, he also raised three new legions (I-III Parthica), based the second of these not far from Rome at Alba, and increased the city of Rome’s number of vigils, urban cohorts, and other units, greatly enlarging Rome’s overall garrison. Having now secured Rome (and, for the moment, Albinus’ loyalty in the west), Septimius now organized a campaign to march to the eastern provinces to eliminate his rival Niger. Severan forces handed out successive defeats to Niger, driving his forces out of Thrace, then defeating him at Cyzicus and Nicaea in Asia Minor in 193 A.D., and ultimately defeating him at Issus in 194 A.D.

While in the East, Severus turned his forces against the Parthian vassals who had backed Niger in his claims. He quickly subdued the kingdoms of Osroene and Adiabene, taking the titles Parthicus Arabicus and Parthicus Adiabenicus to commemorate these victories. To solidify his reputation and attempt to link his new dynasty with that of the Antonines, he declared himself the son of the now deified former emperor Marcus Aurelius and brother of the deified Commodus. Moreover, he conferred upon his eldest son M. Aurelius Antoninus (later the emperor Caracalla) the title of Caesar. This last move led him into direct conflict with his erstwhile ally Clodius Albinus who was initially given this title in return for his loyalty. Realizing that Severus intended to discard him, Albinus rebelled and crossed with his legions into Gaul. Severus hurried west to meet Albinus in battle at Lugdunum and defeated him in a bloody and hard fought battle in February 197 A.D. After defeating Albinus, Severus was now the sole emperor of the Roman Empire.

In the summer of 197 A.D., Severus once again travelled to the eastern provinces where the Parthian Empire had taken advantage of his absence to besiege Nisibis in Roman occupied Mesopotamia. After breaking the Parthian siege there, he proceeded to march down the Euphrates attacking and sacking the Parthian cities of Seleucia, Babylon, and ultimately the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon. He would have liked to have continued his campaigns deeper into the Parthian Empire, although Dio states that he was prevented from doing so due to a lack of military intelligence and knowledge that the Romans had of the Parthian heartland. Septimius then turned against the fortress of Hatra in Iraq, but failed to take it after two attempted sieges. After coming to a face-saving agreement with Hatra, Septimius declared victory in the East, taking the title of Parthicus Maximus (indeed, the Senate voted him a Triumphal Arch in the Roman Forum which still stands today). It was during this time that he organized the lands of northern Mesopotamia, captured from the Parthians, into the new province of Roman Mesopotamia which Dio states Severus hoped would serve as a ‘bulwark for Syria’ against any future Parthian invasions (how effective this policy was in the years after Severus’ reign is a matter which is open to debate).

Severus then travelled to Egypt in 199 A.D., reorganizing the province. After returning to Syria for a year’s stay (end of 200 to beginning of 202 A.D.), Severus finally travelled back to Rome in summer 202 A.D. to celebrate his decennalia with a victory game as well as giving his son Antoninus in marriage to the daughter of his confidant, the Praetorian Prefect Plautianus (who was later murdered thanks to the intrigues of Antoninus). In autumn of that same year, Severus travelled to his homeland of Africa, touring (and greatly patronising) Severus’ home town of Lepcis Magna, as well as Utica and Carthage. At Lepcis Magna, he conducted an energetic program of monument building, providing colonnaded streets, a new forum, a basilica, and a new harbor for his hometown. He also used this time to crush the desert tribes (most notably the Garamantes) who had been harassing Rome's African frontiers. Severus expanded and re-fortified the African frontier, even expanding Rome’s presence into the Sahara thus curtailing the raiding activities of these border tribes who could no longer attack Roman lands with impunity and then escape back into the desert.

Severus then returned to Italy in 203 A.D. where he stayed until 208 A.D., holding the Secular games in 204 A.D. With the murder of his Praetorian Prefect Plautianus, Severus replaced him with the jurist Papinian. His patronage of this new prefect as well as the jurists Ulpian and Paul made the Severan era a golden one for Roman jurisprudence. In 208 A.D., small scale fighting on the frontier of Roman Britain gave Severus the excuse to launch a campaign there which would last until his death in 211 A.D. With this campaign, Severus was hoping for a chance to achieve military glory. Moreover, he brought with him his sons Antoninus and Geta in the hopes of providing them with some administrative and military experience necessary for holding the imperial power (until this point, the two sons had spent their time violently quarrelling with each other as well as behaving like libertines carousing at Rome’s less reputable establishments).

Severus’ intentions in Britain were almost certainly to subdue the entire island and bring it under Roman rule completely. In order to do this, Severus completely repaired and renovated many of the forts along Hadrian’s Wall with the intention of using the Wall as a base from which to launch a campaign to conquer the north of the island of Britain. Leaving Geta south (supposedly leaving him responsible for the civil administration of Britain south of the wall), Severus and his son Antoninus campaigned in the north, especially in what is now Scotland. The course of the campaign was one that was mixed for the Romans: the native Caledonian tribes did not meet the Romans in open battle and engaged in guerrilla tactics against them and caused the Romans to suffer heavy casualties. By 210 A.D., however, the northern tribes sued for peace, and Severus used this opportunity to build a new advance base at Carpow on the Tay for future campaigning. He also took the title Britannicus for himself and his sons to commemorate this victory. This success was short-lived, however, as the tribes soon rose up in revolt. By this time (211 A.D.), Severus could not continue his campaigns against them. He was a long-time sufferer of gout which appears to have taken a toll on him: He died at Eburacum (York) on 4 February 211 A.D.

Severus’ reign witnessed the implementation of reforms in both the provinces and the military which had long term consequences. After the defeat of his rivals, Severus resolved to not have another take power in the fashion that he did. Consequently, he divided the three legion provinces of Pannonia and Syria to discourage future governors to rise up in revolt (Pannonia was divided into the new provinces of Pannonia Superior and Pannonia Inferior; Syria was divided into Syria Coele and Syria Phoenice). Britain was also divided into two provinces (Britannia Superior and Britannia Inferior), although it is debated whether or not Severus or his son and successor Caracalla did this.

Severus is also noted for his reforms of the army. Not only did he greatly increase the size of the army, in order to ensure its loyalty he also raised the annual pay of the soldiers from 300 to 500 denarii (many would have seen this pay rise as overdue, as the last raise in soldiers’ salaries was granted by the emperor Domitian in 84 A.D.). Severus, to pay for these raises, had to debase the silver coinage. It seems that the long term effects this may have had on inflation were minimal, although Severus set a precedent for future emperors to continuously debase the coinage in order to pay for the army. The historians Dio and Herodian criticized Severus for these pay rises, mainly because it put more financial pressure on the civilian population to maintain a larger army. Moreover, Severus ended the ban on marriage which had existed in the Roman army, giving soldiers the right to take wives. This measure has been argued by some to be a positive reform as it gave legal rights to the wives of soldiers who before the ban had no legal recourse as their relationships were informal and not legally binding. So concerned was Severus with the loyalty of the army that, on his deathbed, he is said to have advised his two sons to ‘Be good to one another, enrich the soldiers, and damn the rest.’

Severus could be ruthless towards his enemies. When he defeated Niger in the East, not only did he attack many of the cities in that region which supported his rival, he is noted for taking metropolitan status away from the city of Antioch (Niger’s base of operations), and giving it to its chief rival, the city of Laodicaea. After defeating Albinus at the battle of Lugdunum, Severus released his wrath on the Roman Senate, many of its members having given either muted or open support to Albinus. Severus, after declaring his intentions to purge the Senate in a speech to that body in 197 A.D., proceeded to execute 29 senators of that body for having supported his rival (many other non-senatorial supporters of Albinus met the same fate).

Despite emerging victorious from a period of civil war and bringing stability to the empire, Severus’ sense of accomplishment may have been mixed. His last words, according to various historians, seem to imply that he felt he may have left his work unfinished. Aurelius Victor reported that Severus, on his deathbed, despairingly declared ‘I have been all things, and it has profited nothing.’ Dio, who knew Severus personally, wrote that, as the emperor expired, he gasped ‘Come, give it to me, if we have anything to do!’ [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

REVIEW: Emperor Caracalla was born Lucius Septimius Bassianus on the 4th of April 188 A.D. in Lugdunum (Lyon) where his father Septimius Severus was serving as the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis during the last years of the Emperor Commodus. When Caracalla was seven, his name was changed to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. This was done because of the wish of his father, now emperor, to link the new Severan dynasty with the previous Antonine one. The name ‘Caracalla’ was considered a nickname and referred to a type of cloak that the emperor wore (the nickname was originally used pejoratively and was never an official name of the emperor). At the time his name was changed, Caracalla became the official heir of his father, and in 198 A.D. at the age of ten, he was designated co-ruler with Severus (albeit a very junior co-ruler!).

From an early age, Caracalla was constantly in conflict with his brother Geta who was only 11 months younger than he. At the age of 14, Caracalla was married to the daughter of Severus’ close friend Plautianus, Fulvia Plautilla, but this arranged marriage was not a happy one, and Caracalla despised his new wife (Dio 77.3.1 states that she was a ‘shameless creature’). While the marriage produced a single daughter, it came to an abrupt end when in 205 A.D. Plautianus was accused and convicted of treason and executed. Plautilla was exiled and later put to death upon Caracalla’s accession (Dio 77.5.3). Caracalla was cruel, capricious, murderous, wilfully uncouth, and was lacking in any sort of filial loyalty.

In the year 208 A.D., Septimius Severus, upon hearing of troubles in Britain, thought it a good opportunity to not only campaign there but to take both of his sons with him as they were living libertine lifestyles in the city of Rome. Campaigning, Severus thought, would give both boys exposure to the realities of rule, thus providing experience for them which they could use upon succeeding their father. While in Britain, Geta was supposedly put in charge of civil administration there, while Caracalla and his father campaigned in Scotland.

Although Caracalla did acquire some valuable experience in military matters, he seems to have revealed an even darker side of his personality, and according to Dio, tried on at least one occasion to kill his father so that he could become emperor. Although it was unsuccessful, Severus admonished his son, leaving a sword within his son’s reach challenging him to finish the job that he botched earlier (Dio 77.14.1-7). Caracalla backed down, but according to Herodian, was constantly trying to convince Severus’ doctors to hasten the dying emperor’s demise (3.15.2). In any case, the emperor died at Ebaracum in February 211 A.D. Severus’ last advice to both Caracalla and Geta was to ‘Be good to each other, enrich the army, and damn the rest’ (Dio 77.15.2).

In 211 A.D. Caracalla became emperor along with his younger brother Geta. The relationship between the two did not resemble the loving one of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus fifty years earlier, and it seems that both brothers were constantly conspiring against each other so that one of them could become sole emperor. When the two did try to make decisions together, they constantly bickered, disagreeing on everything from political appointments to legal decisions. Indeed, according to Herodian, things got so bad between the two brothers that not only did they divide the imperial palace between themselves but also tried to convince each other’s cooks to drop poison into the other's food, it was also proposed that the empire be divided up between the two into eastern and western parts. It was only the intervention of the boys’ mother, Julia Domna, that this plan was not realized (Herodian 4.3.4-9).

Nevertheless, Caracalla resolved to be rid of his brother. After a failed attempt to assassinate his brother on the Saturnalia (Dio 78.2), Caracalla arranged a meeting with his brother and mother in the imperial apartments, ostensibly to reconcile. Instead, upon appearing in his brother’s room with centurions, Caracalla had his men murder Geta who tried to hide in his mother’s arms. Despite her shock and sorrow, Caracalla forbade his mother from even shedding tears over Geta (ibid.; Herodian 4.4). So by 212 A.D., Caracalla was sole emperor, and according to Dio, his brother’s murder was followed by a purge of Geta’s followers totalling roughly 20,000 deaths, including that of the former Praetorian Prefect Cilo and the jurist Papinian (Dio 78.3-6).

Caracalla, when explaining his actions to the Senate, asserted that he was defending himself from Geta and rejected the idea that the concept of two emperors ruling the empire could work, declaring that "...you must lay aside your differences of opinion in thought and in attitude and lead your lives in security, looking to one emperor alone. Jupiter, as he is himself sole ruler of the gods, thus gives to one ruler sole charge of mankind." The Senate could do nothing but tremble before his words (Herodian 4.5). Geta was duly damned from memory (damnatio memoriae), and all references to him in public were erased; it was considered a crime to mention his name.

While Caracalla did not take his father’s advice in being good to his brother, he certainly took to heart that he needed to keep the army happy. Indeed, Caracalla declared to his soldiers that: "I am one of you," he said, "and it is because of you alone that I care to live, in order that I may confer upon you many favours; for all the treasuries are yours." And he further said: "I pray to live with you, if possible, but if not, at any rate to die with you. For I do not fear death in any form, and it is my desire to end my days in warfare. There should a man die, or nowhere. (Dio 78.3.2). He backed up his words with actions by raising annual army pay, evidently by 50% (Herodian 4.4.7). In order to pay for this raise, Caracalla debased the coinage from a silver content of from about 58 to 50 percent. It should be noted, however, that while he did debase the coinage, this did not cause deflation, as those receiving the coin were willing to accept its basic value.

Caracalla also created a new coin known as the antoninianus which was supposed to be worth 2 denarii to help pay for these army raises (although the actual silver content was only worth 1.5 denarii; Birley 1996, 221). The more traditionalist school argues that debasement caused price inflation which began in the Severan era (For example, see Jones 1974; Greene 1985, 57-66; Burnett 1987, 122-131). A more ‘moderate’ school states that the debasements of Severus and Caracalla did not cause inflation; however, because of the precedent set by the Severans to debase, this became a regular practice of successive emperors when they needed coin, and that consequently inflation set in during the reign of Gordian III (Crawford 1975, 566-71; Potter 1990). A third school of thought states that there is no evidence that inflation occurred at all in the third century as a result of debasement as the empire was not fully monetized, especially in the frontier areas,and this extra coinage was merely absorbed into these non-monetized areas.

Indeed, as long as those using the money were willing to accept the face value of the coinage, there would not be debasement-caused inflation. When inflation did occur, it usually was as a result of whenever an emperor such as Aurelian or Diocletian tried to reform the currency which caused a temporary loss of confidence in the coinage and caused prices to fluctuate wildly in the short term (see Rathbone 1996, 321-40). This debate has been continuous and shows no signs of being resolved any time soon. Moreover, he attempted to portray himself as a fellow soldier while on campaign, sharing in the army’s labours, personally carrying legionary standards and even grinding his own flour and baking his own bread, as all Roman soldiers did. These actions made him wildly popular with the army.

During this time, military activity in Britain began to wind down. As the campaign in Britain had stalled by the end of Severus’ reign, Caracalla thought it necessary to engage in a face-saving maneuver and end the campaign there, but not before essentially creating a protectorate in southern Scotland to keep an eye on native activities. This essentially not only ensured his father’s legacy as a propagator imperii on the island but also would justify Caracalla’s adoption of the title Britannicus (Birley 1988, 180). Even so, the natives north of Hadrian’s Wall and the ‘protectorate’ had probably by this time felt discretion to be the better part of valour as making trouble had only invited the Roman army into their lands.

If this is the case, then the Severan campaigns in Scotland kept that area peaceful for the better part of a century (Breeze and Dobson 2000, 152). There is also a degree of debate over whether it was Severus or in fact Caracalla who was the one to split Britain into two provinces in order to prevent governors from having access to a large number of legions thus tempting them to make a bid for the imperial throne. Instead, upon leaving Rome in 213 A.D., Caracalla (who would spend the rest of his reign in the provinces) decided to campaign in Raetia and Upper Germany against the Alamanni. While it is not clear if these enemies were making trouble for the empire, Caracalla prepared for this campaign very thoroughly and it seems that this campaign may have been a pre-emptive strike or a chance for Caracalla to win military glory in his own right.

In any case, it is important to state that there was no serious enemy activity on this frontier until two decades later, so the emperor may have made an important contribution to Rome’s security there, and had legitimate claim to the title of Germanicus which he adopted after these campaigns. Southern writes that Caracalla’s frontier policy in this region: "...seems to have been a combination of open warfare and demonstrations of strength, followed by an organisation of the frontiers themselves. He may have paid subsidies to the tribes after his campaigns, and in other cases he stirred up one tribe against another to keep them occupied and their attentions diverted from Roman territory..." (Southern 2001, 53).

One of the most noteworthy (and debated) acts of Caracalla’s reign is his Edict of 212 A.D. (the Constitutio Antoniniana) which awarded Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. The motives for this action are many. Propagandistically, this edict allowed Caracalla to portray himself as a more egalitarian emperor who believed that all free people of the empire should be citizens, thus creating a stronger sense of Roman identity among them (Southern 2001, 51-2; Potter 2004, 138-9). More practically, however, this edict meant that Caracalla could widen the base from which he could collect an increased inheritance tax (ibid). Indeed, Dio states that, as a result of the money he lavished on the army, a financial shortfall was created and the emperor needed money, thus necessitating this edict and the consequent cheapening of the citizenship. Moreover, the propaganda of equality was illusory, as instead of a hierarchy of citizens and non-citizens in the empire, the edict created a new class division of upper and lower classes (honestiores and humiliores) in which honestiores had greater legal rights and privileges, while humiliores had less legal protection and were subject to harsher punishments (Southern 2001, 52).

Simply put, Caracalla idolized Alexander the Great and sought to emulate him (Dio 78.7-8). Consequently, he saw fit to campaign in the east as a way to accomplish such emulation. It is debatable whether or not such campaigns were necessary, as at this time Rome’s major rival, the Parthian Empire, was involved in internal conflicts, and the Parthian Royal House was fighting among itself (Dio 78.12.2-3). Caracalla saw this, however, as an excuse to mount a campaign to make gains at the expense of the Parthians. He returned to Rome after his activities in Germany, summoned Abgar, the King of Edessa, to the city and imprisoned him in the hopes of turning Edessa into a colony and use it as a base from which to launch an invasion of Parthia. He seems to have tried to have done the same with the king of Armenia but encountered resistance from that land’s population (Dio 78.12.1).

When he arrived in the East in 215 A.D., Caracalla had little reason to justify an invasion of Parthia, as that empire’s king, Vologaeses V, made a point to avoid any action that could be construed as a provocation. Leaving preparations for a campaign against Parthia to his general Theocritus, Caracalla visited Alexandria, ostensibly to pay respects to Alexander the Great at his tomb. He was first welcomed by the Alexandrians, but when he found out they were making jokes about the reasons he gave for the murder of his brother Geta, flew into a rage and had a large segment of the population massacred (Dio 78.2.2; Herodian 4.9.8).

Caracalla then moved east to the frontier in 216 A.D. and found that the situation was not as advantageous to Rome as it was previously. Vologaeses’ brother Artabanus V had succeeded him, and managed to reinstate a degree of stability to Parthia. Caracalla’s best option in this instance would have been a quick campaign to demonstrate Roman strength, but instead the emperor opted to offer his own hand in marriage to one of Artabanus’ daughters. Artabanus’ refused, seeing this as a rather lame attempt by Caracalla to lay claim to Parthia (Herodian 4.10.4-5; Dio 79.1). According to Herodian, Caracalla’s behaviour was even more reprehensible: the emperor invited Artabanus and his household to meet to discuss a permanent peace. Upon meeting with the Parthian king and his retinue, who had put aside their weapons as a sign of good will, Caracalla ordered his forces to massacre them. Most of the Parthians present were killed, but Artabanus was able to escape with a few companions (Herodian 4.11.1-6).

Caracalla then campaigned in Media in 217 A.D. and was planning a further campaign when his treacherous and rash behaviour caught up with him. It seems that he made sport of ridiculing his Praetorian Prefect M. Opellius Macrinus, who had a great deal of experience in legal matters but next to none in affairs militarily (Herodian 4.12.1-3). Macrinus began to resent this, but Caracalla began to fear the man, especially after hearing of a prophecy that Macrinus would become emperor. Caracalla then began to move against his Prefect, but Macrinus got wind of this and, realizing he was in great danger, conspired to assassinate the emperor (Dio 79.4.1-2; Herodian 4.12.5). This he did on the road to Carrhae when the emperor stopped his troops on the side of the road to relieve himself. Evidently, while Caracalla was in the midst of urinating, one of Macrinus’ men fell upon him, ending the emperor’s life (Dio 79.5; 4.13.1-5). Caracalla was 29 years old when he died. When the bulk of the army had heard of his end, they were enraged at the murder of the emperor whom they loved. Indeed, Macrinus’ inability to placate the soldiers helped to play a part in his own demise when his enemies offered Caracalla’s cousin Elagabalus as Emperor in 218 A.D.

Caracalla was one of the most unattractive individuals ever to become emperor of Rome. He was cruel, capricious, murderous, wilfully uncouth, and was lacking in any sort of filial loyalty save for that of his mother Julia Domna (who died shortly after his assassination). This is certainly the picture given to us by both Dio and Herodian. While some of the information in these accounts might be embellished, they nevertheless shed light on the increasing trend of emperors depending more on the army, believing they could act in any way they wanted towards the rest of the population provided they keep the soldiers happy. This is not entirely the fault of Caracalla, as he was following the advice of his father and genuinely wanted to be seen as a soldier and conqueror in the vein of Alexander the Great rather than the ‘philosopher king’ that Marcus Aurelius embodied. While his military policies in the western empire may have contributed to that region’s security for several years, his eastern policy was self-destructive and unnecessary. Had Caracalla followed the formula of Augustus and maintained a balance between keeping both the army and the upper echelons of Roman society happy, he may have been more successful. In any case, the third century would witness many emperors who took the tact that Caracalla had and would overly depend on the support of the army for their regime at their own peril. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].