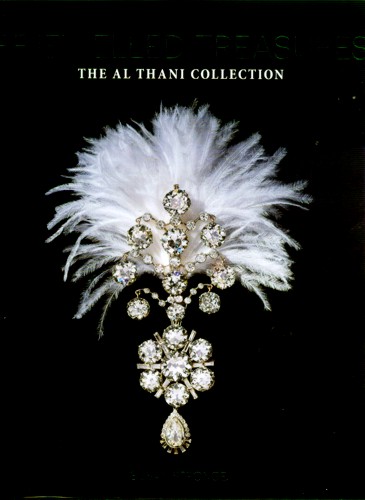

"Bejewelled: Treasures from the Al-Thani Collection" by Susan Stronge.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Softcover. Publisher: Victoria & Albert Museum (2015). Pages: 128. Size: 11¼ x 9¾ x 1 inch; 1¾ pounds. This sumptuous book invites readers to examine in exquisite detail some of the world’s finest and rarest examples of Indian jewelry from one of the world’s preeminent collections, objects once owned by the great maharajas, nizams, sultans, and emperors of India from the 17th to the 20th century. Highlights include a rare gold finial from the throne of Tipu Sultan (1750–1799), inlaid with diamonds, rubies, and emeralds and in the shape of a tiger’s head, and a dagger with a stunningly carved jade hilt and a watered steel blade inlaid with gold owned by Shah Jahan. Other pieces reveal the dramatic changes that took place in Indian jewelry design during the early 20th century. This glorious book also examines the influence that India itself had on avant-garde European jewelry made by Cartier and other leading houses and concludes with contemporary pieces made by JAR and Viren Bhagat of Mumbai, which are inspired by a creative fusion of Mughal motifs and art deco “Indian” designs.

CONDITION: NEW. HUGE new hardcover with dustjacket. Victoria & Albert Museum (2015) 128 pages. Still in manufacturer's wraps. Unblemished and pristine in every respect. Pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 14 days! #8625a.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Indian jewelry is among the most opulent and finely wrought in the world. This book draws on over 100 exquisite pieces from the Victoria and Albert Museumand#8217;s superb collection, many never published before. Nick Barnard illuminates the social context and symbolic meanings as well as the varied techniques employed by craftsmen. He describes how jewelry was worn and by whom, how stones were sourced and cut, how traditions of making and wearing varied in different parts of the country, and how the collection itself was brought together by travelers and scholars over the years.

REVIEW: The earliest known example of Mughal jade; spectacularly large spinels inscribed with the names of emperors from the Mughal treasuries; a jeweled gold tiger’s head finial from the throne of the famed Tipu Sultan of Mysore and a dazzling brooch inspired by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes made in Paris in 1910 are among the treasures on public display for the first time in the UK, as part of the V&A’s new exhibition “Bejewelled Treasures: The Al Thani Collection”.

The exhibition presents around 100 spectacular objects belonging to or inspired by the jewelry traditions of the Indian subcontinent, drawn from a single private collection, alongside three important loans from the Royal Collection generously lent by Her Majesty The Queen. The exhibition showcases magnificent precious stones evoking the royal treasuries of India, particularly that of the Mughal emperors in the 17th century, as well as exquisite objects used in court ceremonies. It reveals the influence of India on jewelry made by leading European houses in the early 20th century and displays contemporary pieces with an Indian theme made by modern masters.

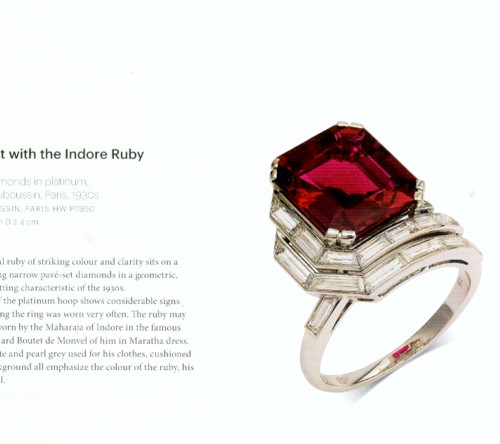

Highlights include magnificent unmounted precious stones including a Golconda diamond given in 1767 to Queen Charlotte by the Nawab of Arcot in South India, and Mughal jades, notably a jade-hilted dagger that belonged to the 17th-century emperor Shah Jahan who built the Taj Mahal. Other precious objects include pieces from the collections of the Nizams of Hyderabad; renowned jewels from the early 20th century by Cartier, including those made especially for the Paris 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, the exhibition that gave Art Deco its name; as well as traditional Indian jewels refashioned in the 1930s into European avant-garde styles by the elegant Europhile, Yeshwant Rao Holkar II, Maharaja of Indore, who was a close friend of the surrealist photographer Man Ray. There are also contemporary pieces made by JAR of Paris and Bhagat of Mumbai which combine Mughal inspiration and Art Deco influences.

The objects are drawn from the Al Thani collection which is notable for the quality and size of its precious stones, both unmounted and set in jewelry. These reflect India’s position over many centuries as an international market for precious stones, including diamonds from its famous Golconda mines, emeralds from South America, rubies from Burma, spinels from central Asia and sapphires from Sri Lanka. The Mughal emperors and their successors used objects made of luxury materials in their courts, and the exhibition highlights the sophisticated techniques used by goldsmiths in the Indian subcontinent to make them. The three major loans from the Royal Collection, lent by Her Majesty The Queen, are a jeweled bird from the gold canopy of Tipu Sultan’s throne, the ‘Timur Ruby’ and the Nabha spinel.

Martin Roth, Director of the V&A said: “This is a fascinating insight into a great private collection that includes extraordinary precious stones, both unmounted and set into jewels. The exquisite quality and craftsmanship of many fine pieces from and inspired by India complement the V&A’s own South Asian and jewelry collections. The exhibition is a spectacular element of the Museum-wide India Festival this autumn.” Sheikh Hamad Bin Abdullah Al Thani said: “The jeweled arts of India have fascinated me from an early age and I have been fortunate to be able to assemble a meaningful collection that spans from the Mughal period to the present day."

Nicholas Snowman, Chairman of Wartski said: “We are delighted to be sponsoring this magnificent exhibition at the V&A in this, the 150th year of the foundation of our company. Wartski and the V&A have a long history of shared scholarship, loans and gifts. This happy association was cemented at the ‘Fabergé’ exhibition curated by my father, the firm’s chairman, Kenneth Snowman in 1977. Family connections with the V&A continued in 1988 when my wife, Margo Rouard-Snowman, co-curated ‘Avant Première’ and in 2002, when Geoffrey Munn, our Managing Director, presented the exhibition ‘Tiaras’.”

The exhibition is arranged in sections exploring different elements of evolving styles and techniques. The Treasury evokes the royal storehouses of the Mughal emperors in the late 16th- and early 17th-century, which held precious stones of spectacular size. The Court showcases objects owned by famous rulers such as Shah Jahan, whose architectural commissions in the 17th century introduced a new decorative style which still influences Indian craftsmen to the present day. It also includes objects that would have been used in court ceremonies.

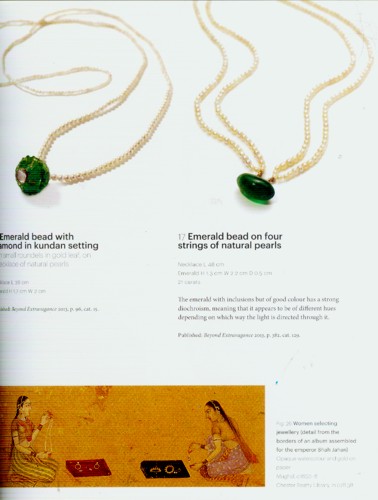

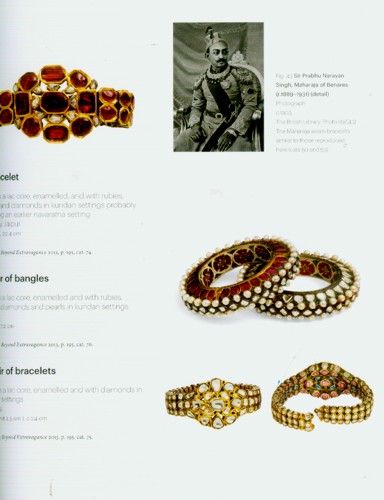

A section devoted to Kundan and Enamel explores the quality and appeal of the vivid colours of two fundamental Indian jewelry techniques. Kundan, meaning ‘pure gold’, is the uniquely Indian style of setting precious stones in gold ornaments. From Mughal times, enameling was used, usually hidden from view on the back of ornaments set with diamonds, rubies, emeralds and other precious stones. Newly commissioned films show both techniques which are still characteristic of traditional Indian jewelry today.

The Age of Transition demonstrates the gradual influence of the West on Indian jewelry in the late 19th-and early 20th-centuries, particularly in Hyderabad under the Nizams. Open settings allowed light to shine through cut diamonds and emeralds, and European conventions appeared in traditional jewelry, such as a diamond-set platinum hair ornament designed to cover the long hair plait worn by many Indian women. Modernity introduces the transforming influence of India on jewelry design in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s.

The house of Cartier, and individuals such as the Parisian designer Paul Iribe, reinterpreted traditional Indian forms in Art Deco style, and set Indian-cut emeralds next to sapphires in a startling new colour combination. The final section Contemporary Masters highlights the continuing influence of traditional Indian jewelry reinterpreted in completely modern idioms. The work of Paris-based JAR echoes Mughal architectural features, while Bhagat of Mumbai selects old-cut diamonds or sapphires as the centrepiece of new designs which often show the influence of Art Deco inspired by India.

REVIEW: Published to accompany the Victoria & Albert Museum exhibition, “Bejewelled: Treasures of the Al-Thani Collection”, 21 November 2015 to 28 March 2016. P> REVIEW: Susan Stronge is senior curator in the Asian Department of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

REVIEW: Nick Barnard is a curator of South Asian art in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Asian Department. He has specialized in Indian jewelry since 2000 and was a contributor to “Encounters: The Meeting of Asia and Europe”

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: In 1442, a Persian ambassador was sent to the small kingdom of Calicut in India. Entering the fortified city walls, he noted in his travel diary that “all the aristocrats and ordinary people from these lands, including the bazaar professionals, put gems and gem-encrusted jewels in their ears, on their neck, on their arms, over their hands and on their fingers.” His account reveals how entrenched the traditions and crafts of jewelry have been in India for centuries, from the sparkling jewels that adorned the thrones and bodies of courtly figures in the 14th century, through to the opulent Mughal empire and up to the contemporary pieces cut in Mumbai’s diamond workshops.

It is these long, rich traditions that led one of the world’s wealthiest men, Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani, to start acquiring Indian jewelry five years ago. Now his vast collection, which boasts some of the world’s rarest pieces – from gems that adorned the necks of Mughal kings and maharajas to pieces that sparkled in Cartier displays – is to be displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. “Bejewelled Treasures” will exhibit more than 100 pieces of jewelry and priceless stones both from, and inspired by, the Indian subcontinent. All but three of the pieces are from the Al Thani collection, which has become one of the most spectacular in the world over the last five years. The V&A is a fitting place to display the treasures of Al-Thani. After all, it was here, in 2009, that the Qatari multimillionaire prince saw a show on the Splendor of India’s Royal Courts, and vowed to create his own treasury.

“The stories embedded in jewelry are what makes it so interesting,” says Susan Stronge, an expert on Mughal Indian arts, who curated the show. “The Al Thani collection is extraordinary, not just because of its size, but because it highlights the exchange of influences between India and Europe right up to today.” The show will open with a room of unmounted jewels, which will “hopefully dazzle people when they enter”. Visitors are then taken through sections that explore the creeping European influence on India, the Indian influence on Cartier and art deco jewelry in the 1920s, and the exchange of eastern and western styles in pieces made as recently as 2014.

Indeed, the stories around the pieces are often as dazzling as the jewels themselves. The pink Agra diamond, for example, is thought to have been owned by the first Mughal emperor Babur in 1562, but was stolen from the Delhi imperial treasury in 1739. After finding its way back to India, the 28-carat diamond was seized again, this time by English officers, and the story goes it was smuggled to London inside a horse who was forced to swallow it.

Another piece dated back to 1910 – a brooch inlaid with a weighty crescent-shaped emerald – belonged to beautiful Spanish dancer Anita Delgado, who was spotted at a wedding in Madrid by the Maharaja of Kapurthala. He fell in love with her instantly, and although she was only 16, he married her and brought him back to India, where she became his fifth wife. The emerald, says Stronge, was the maharaja’s 19th birthday gift to Delgado after she spotted it in front of an elephant during a parade. It is said that as he handed her the precious stone, he said: “Now you can have the moon, my capricious little one.”

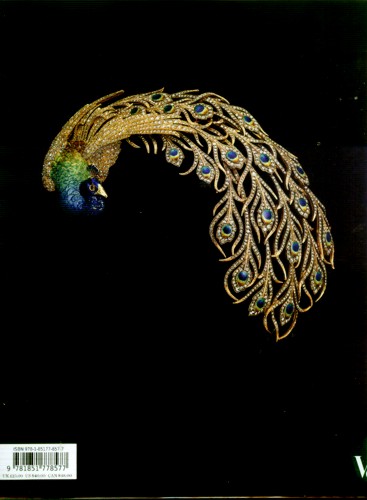

Another piece on show is a dagger from 1610 (dated through paintings of the Mughal court at the time). It is thought to have belonged to Emperor Jahangir, and is made of jade inlaid with rubies, emeralds and 24-carat gold and decorated with peacock motifs. “This dagger is extremely rare,” says Stronge. “Sanskrit treatises on rubies state that the finest are the color of pigeon’s blood – and these are very deep red, so probably only used at the very top of the court circle for princes or emperors.” Stronge adds: “The blades on these daggers worked so they were capable of killing people, but they were very decorative and might be given as presents [for] a birthday or [if] some noble was going off to battle.”

The Mughals were invaders from central Asia, Muslims that grew up with a strongly Iranian culture, which was reflected in their jewelry. The empire was founded in 1526 by Babur and by the end of the 16th century it had become well-established and incredibly wealthy. Emperor Akbar, for example, had so many unmounted precious stones that by the 1590s one of his 12 treasuries was reserved solely for these loose jewels – the most valuable of which was the spinel. As well as displaying centuries’ old rarities, the show explores the exchange of influences between India and the west over the past 100 years. A seminal moment came in 1911 when Jacques Cartier made his first trip to India. It was here he made links with Indian princes, maharajas and jewelry traders and began to import and design pieces with an Indian influence.

Yet ideas of style and beauty certainly differed between the two cultures, says Stronge. “In India, irregularity is not seen as a defect in stones, whereas in western jewelry you want everything to be very regular, including diamonds,” she says. “In India, they valued weight over everything, whereas the western style is to cut out the irregularities and give it greater brilliance. Inclusions and impurities can decrease the value of a jewel, but it’s also what gives it character.” Stronge admitted she has not been able to see the entire Al Thani collection – it increases in size every month as he acquires ever more. But she and her fellow curators did get to see some of India’s artistry in action.

“We all traveled to India in January to visit diamond-cutting workshops and watch the craftsmen create pieces using the same ancient techniques,” she said. “Even today, the skills involved in jewellery making in India are really extraordinary.” Both the exhibition and the accompanying catalog are highly recommended.

REVIEW: This exhibition showcased over one hundred exceptional jewels, jeweled artifacts and jades from the Al Thani Collection. The pieces range in date from the early 17th century to the present day, and were made in the Indian subcontinent or inspired by India. They include spectacular precious stones, jades made for Mughal emperors and a gold tiger-head finial from the throne of the South Indian ruler Tipu Sultan.

Objects from the collections of the Nizams of Hyderabad show the influence of Western techniques and gem cutting on the work of Indian jewelers. Famous jewels from leading European houses such as Cartier reveal the more significant impact of India on Art Deco jewelry in the early 20th century. These bejeweled treasures highlight the exceptional skills of goldsmiths within the Indian subcontinent. The most recent pieces by jewelers such as JAR and Bhagat also demonstrate that cross-cultural exchanges continue to inspire contemporary jewelry design in India and Europe.

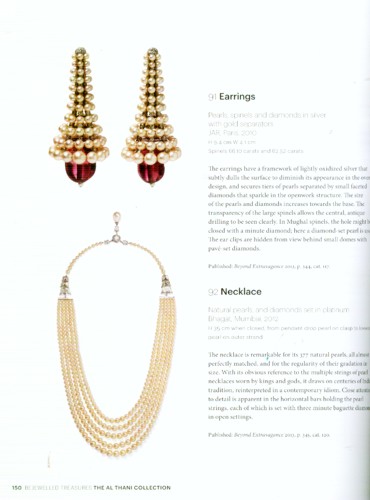

From ancient times, the royal treasuries of India contained vast quantities of precious stones. Diamonds were found within the subcontinent, most famously in the southern region of Golconda. The best rubies came from Burma. Sri Lanka supplied sapphires, and from the 16th century emeralds were brought from South America to Goa, the great Eastern market for gemstones. These were of a size, color and clarity that had never been seen before. Early Sanskrit treatises on gemology give precedence to nine diamond, pearl, ruby, sapphire and emerald have primacy over four other, semi-precious stones. Each represents a planet. They are sometimes combined in a 'navaratna' (nine gem) setting as an amulet.

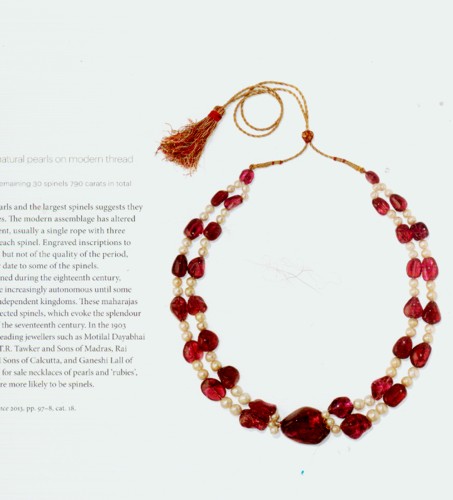

At the Mughal court, Iranian traditions shaped the culture of the Persian-speaking elite. Here, the classification of gemstones was completely different. From the late 16th century, the most valuable stones were deep red spinels, found in Badakhshan in Central Asia. Spinels are similar to rubies, but are gemologically distinct. The finest were appreciated for their color, size and translucency, and were engraved with the emperors’ titles. Their spinels were not usually faceted, but the royal gem-cutters gouged out any unsightly inclusions and simply polished the irregular surface.

Mughal rule had a lasting influence on the arts of the Indian subcontinent. The Muslim emperors, originally from Central Asia, were most powerful in the late 16th and 17th centuries. They were molded by Iranian culture and Persian literature, but they also borrowed courtly conventions from Hindu tradition. Emblems of royalty included fly whisks held near the emperor, gold thrones and jewelry such as thumb rings, long necklaces of precious stones, and turban ornaments. When Mughal power declined, the regional rulers of the subcontinent adopted much of this regalia.

Outside the Mughal empire, one of the most distinctive courts was that of Tipu Sultan of Mysore. Objects made for him were decorated with tiger motifs, a personal emblem of his sovereignty and Muslim faith. His resistance to the British led to his ultimate defeat and death in 1799. The East India Company army looted his capital and seized his treasury. His gold throne was destroyed, but some jeweled tiger-head finials and the bird from its canopy survived.

In the late 16th century, Mughal court goldsmiths combined two techniques, creating a new style that is still used in traditional Indian jewelry. They set ornaments and luxury artifacts with precious stones using pure gold, or 'kundan', a historic Indian process. For the first time, they added enamel to the back or inner surfaces of ornaments. Enameling was previously unknown in the subcontinent and was probably introduced from Europe.

The fashion spread across the empire’s northern provinces. By the 19th century, when the Mughal empire existed only in name, Jaipur in Rajasthan and Varanasi (Benares) in present-day Uttar Pradesh had become famous for their enameling in different styles. Each stage of making kundan jewelry is done by a specialist craftsman. The sophisticated technique allows precious stones of any size or shape to be set into designs of great complexity. Kundan can also be used to set stones in jade or crystal.

With the political upheavals of the 18th and early 19th centuries, production of traditional jewelry gradually moved out of palace workshops and into the commercial world. The process accelerated after the establishment of British rule in 1858. In centers like Jaipur, where the maharajas actively supported the manufacture of enameled kundan work, jewelry was increasingly bought by, or made for, Europeans.

Small independent British companies employed Indian goldsmiths, while Indian jewelers established workshops in major cities. Their craftsmen made traditional Indian jewelry or adopted Western styles and techniques with equal facility. The use of Western-cut stones was one of the most significant changes. Their perfectly regular shapes were seen to best effect in open European settings, rather than the closed settings of kundan jewelry.

A new railway network allowed jewelers to sell to patrons across the subcontinent, from the Nizams of Hyderabad in the south to Sikh maharajas in the far north. Remarkable exchanges took place between India and the West in the early 20th century. European jewelry absorbed Indian influences, while some Indian princely patrons wore contemporary Western jewelry.

In Paris, the Ballets Russes inspired a fashion for orientalism with its sensational 1910 production of Schéhérazade. The stage sets and costumes in vermilion, crimson, indigo, purple, green and gold reflected the colours of the Mughal and Iranian book paintings acquired by European collectors, including the jeweler Louis Cartier. At the same time, India’s princes, educated by Western tutors, visited Europe and bought jewelry from leading houses such as Cartier. These relationships grew stronger when Jacques Cartier traveled to India in 1911 to attend the great Delhi Durbar, held to mark the accession of George V as Emperor of India.

Some Indian rulers later brought their own jewels to Europe to be reset. For the first time in traditional Indian jewelry, the gold associated with kingship and divinity was abandoned for the lightness of platinum. Outstanding jewels of the Indian past continue to inspire designers. Forms drawn from traditional kundan jewelry are adapted to settings of extraordinary lightness and delicacy. Exceptional stones cut in the Mughal manner are combined with gems shaped by the latest precision techniques.

A brooch made by Bhagat of Mumbai is set with old Golconda diamonds and smaller stones cut specially for it. An emerald in a brooch by JAR of Paris seems to float on white agate, setting off its cut and beautiful color within a frame that echoes Mughal architecture. A necklace by Cartier has magnificent red spinels that retain their original irregular shapes, and a Bulgari ring is set with a rare engraved Mughal emerald. All these pieces draw on the complex artistic traditions of the subcontinent, reinterpreting them in a completely modern idiom.

REVIEW: Of all the great dynasties the world has produced, the Moguls of India have gifted us the most beautiful remains. Such is the view of one prominent aficionado, HH Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani, a member of the Qatari ruling family. The 33-year-old is the man behind a new exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum opening this month, which offers a close-up look at his dazzling private collection, hailed as one of the top few in the world.

It features not only jewelry and trinkets from the Muslim dynasty that ruled most of northern India from the early-16th to the mid-18th century but also later pieces that show how following generations picked up the Mogul themes and ran with them, right through to Cartier’s Art Deco creations in the 20th-century and contemporary pieces from the 21st.

It seems fitting that the Victoria & Albert Museum should play host to such a display, since this is where, for Sheikh Hamad, it all started. In October 2009 he visited its Maharaja exhibition. The exhibits he saw that day fuelled his love affair with fine jewelry, and particularly that of the Mogul emperors. So beguiled was he that he began a worldwide search for items from the period.

Talking to him at Dudley House, the belle époque mansion on Park Lane that he has acquired, renovated and furnished with decorative arts at the highest level, he appears thoughtful, understated and with old-world manners. But he comes alive when discussing his treasures, and is gratified that the museums of the world are now queuing up to borrow what he calls "his babies". The collection was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York last year, where it received rave reviews.

For Sheikh Hamad, the pleasure comes in making his chosen subject known to a wider audience. "The jeweled arts of India have fascinated me from an early age and I have been fortunate to be able to assemble a meaningful collection," he told the New York museum at the time.

Like all collectors, he believes in the importance of provenance, both as a guarantee of authenticity and for the romance it brings with it. In the case of the Moguls, that sense of romance is not hard to find. The dynasty, of Turco-Mongol origin, may have been founded on an appetite for conquest but beyond the battlefield its rulers were renowned for their patronage of science and the arts, as well as for religious tolerance (the population over which they presided was mostly Hindu).

When Sheikh Hamad speaks of his collecting hero we come into the presence of the most magical name in the story, Shah Jahan, who reigned from 1628 to 1658, a period that marked the dynasty’s cultural high point. It was during this time that Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal, and it is great buildings such as this for which the Moguls are best known. But it is the personal jewelry and private objets de vie that afford us the most intimate glimpse of these warrior-aesthetes. And few great rulers have displayed such discrimination in their personal objects as Shah Jahan.

The sheikh shows me Shah Jahan’s emerald, with an inscription using the imperial title padishah ("master of kings") before he was entitled, revealing his intention to overthrow his father. Equally personal is the Shah Jahan dagger (c1620-25), the handle of which is cut from a single block of jade and ends in a finial of a boy’s head. The blade, with its emblem of the imperial umbrella ("the shade of God") is from Shah Jahan’s time, but the sheikh believes the handle was carved during the reign of Shah Jahan’s father by Venetian craftsmen at the Mogul court, which would account for the boy’s European appearance.

If he’s correct, it would not be the only foreign influence at the Mogul court. The sheikh points to the evident influence of Persian craftsmen, which he illustrates with a pen case and inkwell of gold, encrusted with emeralds and cabochon rubies, which would have been used on state occasions.

One object that will have a special resonance for British visitors, who may have seen the celebrated Tipu’s Tiger in the V&A’s permanent collection, is the finial from the throne of Tipu Sultan, a tiger’s head in gold, inlaid with diamonds, rubies and emeralds. It is one of eight that used to adorn the throne of this sworn enemy of British ambitions in India, and was captured after the fall of Seringapatam in 1799, when Tipu was killed.

So how did such treasures come into the sheikh’s possession? Behind each object is a different story, it seems. The Shah Jahan dagger came on to the British market in the 1970s and popped up at a V&A exhibition the following decade before once again disappearing. It was a former curator at the museum who set up the sale by a private collector to the sheikh.

Other pieces entered his hands fortuitously, but not without great effort on his part. A text message from a friend, for instance, led to his acquisition of the tiered ruby choker that Jacques Cartier had made in 1931 for the Maharaja of Patiala. The sheikh’s friend informed him Cartier had the piece, so he contacted the company and put it on hold before jetting from Hong Kong to see it in Paris.

But if Sheikh Hamad’s flair for collecting sets him apart, he is not the first aesthete produced by the Al Thani family. Sheikh Saoud, his older cousin who died last year, was a compulsive collector of antiquities who established Doha as an art destination. Sheikh Hamad, by contrast, enjoys restoring palaces in Europe. As well as Dudley House, undoubtedly the grandest private residence in London today, he and his family have acquired the Hôtel Lambert in Paris, former home of the Rothschilds, and he speaks of his separate passion for architecture with an equally impressive knowledge.

Yet I wonder if anything makes him light up quite as much as his beloved jewels. When he shows me his rosewater sprinkler (1675-1725), made of gold and set with foiled cabochon rubies and emeralds divided by rows of half-pearls, his face beams with pleasure. The item bears an inscription from the Imperial Treasury and was part of the then emperor’s personal equipage. "I can feel the vibrations," he says, in near-reverential tones.

The body of his collection may hail from an exotic past, but for Sheikh Hamad these emperors are very much alive through their treasures. When the public stream in to see his delights, a shining slice of old India will come alive for them too.

REVIEW: This exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum entitled “Bejewelled Treasures: The Al Thani Collection” will explore around 100 objects from or inspired by the jewelry traditions of the Indian subcontinent, drawn from a single private collection formed by Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani. The objects range from precious stones of the kind collected by Mughal Emperors in the 17th century to modern Indian jewelry of the present day.

Highlights include an Indian turban jewel made for the Maharaja of Nawanagar set with large diamonds; unmounted precious stones including a Golconda diamond given to Queen Charlotte by the Nawab of Arcot, South India in 1767; Mughal jades such as a jade-hilted dagger that belonged to the 17th-century emperor Shah Jahan who built the Taj Mahal; a jeweled gold tiger’s head finial from the throne of the famed Tipu Sultan of Mysore; pieces from the collections of the Nizams of Hyderabad who possessed legendary wealth; and renowned jewels from the early 20th century by Cartier. There will also be contemporary pieces made by JAR of Paris and Bhagat of Mumbai which combine Mughal inspiration and Art Deco influences.

The exhibition is arranged in sections exploring the different elements of evolving styles and techniques. The first section called The Treasury illustrates that the elites of India since ancient times collected and were fascinated by precious gems. Diamonds, pearls, sapphires, emeralds and rubies were considered the most important gems and the Mughal emperors in the late 16th- and early 17th-century followed the tradition of interest in gems. However, the Mughals reflected their own Iranian ancestry by making red spinels their most valuable stone.

The section on The Court showcases how precious objects owned by the Mughal emperors played an important part in court ceremonies, when Mughal influence declined these trappings of power were taken up by other royal houses including Tipu Sultan of Mysore. One of the most important techniques developed in the 16th century was when goldsmiths began to set precious stones in 24 carat gold or kundan and began to add enamel to the back of ornaments. These high specialized skills have been influential in Indian jewelry and a series of films show and explain Indian jewelry making techniques such as enameling and ‘kundan’.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw The Age of Transition when the influence of the West and especially the British began to take effect, open settings which allowed light to shine through cut diamonds and emeralds became popular and European motifs began to appeared in traditional jewellery. This carried on into the 20th century, however the influence was not all one way, the section on Modernity illustrate that Indian forms were reinterpreted by the famous house of Cartier and individuals such as the Parisian designer Paul Iribe. Using the Indian influence in Art Deco designs became very popular especially the use of Sapphires and Emeralds.

In the final section Contemporary Masters explores the way that the cross fertilization of influences have led to Paris-based JAR echoing Mughal architectural features while Bhagat of Mumbai selects old-cut diamonds or sapphires as the centerpiece of new designs which often show the influence of Art Deco. This fascinating exhibition will appeal to anyone with an interest in precious stones and the influence of jewelry traditions of the Indian subcontinent. The incredible wealth of the Mughal emperors allowed the commissioning of remarkable decorative pieces which were used to advertise their power and prestige. The decorative style of the period still influences Indian craftsmen and women to the present day. More recently influences have passed between India and the West to create objects that reflect the tastes of both. Highly Recommended!

REVIEW: This stunning collection with more than 100 objects owned by Sheikh Hamad Bin Abdullah Al Thani, a member of the Qatari royal family, have been loaned to the V&A for the show, which explores 400 years of Indian jewelry. It is being staged as part of the Victoria & Albert Museum's India Festival and is sponsored by Wartski.

Highlights include Mughul Jades, jeweled finial from the throne of Tipu Sultan and modern pieces which serve to illustrate how designs and tastes changed over time. It showcases also how Indian style had an influence on avante garde European jewelry designs made by leading houses like Cartier and how modern pieces by JAR and Bhagat are inspired by a fusion of Mughal motifs and Art deco designs with an Indian twist.

The collection also includes three major loans from the Royal Collection, lent by Her Majesty The Queen which are the Nabha Spinel, a jeweled bird (Huma bird) from the canopy of Tipu Sultan's Throne and the 'Timur Ruby'. Spinel is a gemstone that comes in different colors with the purest form being colorless. The most desirable colours are the deep blood reds. They are also blue, orange pink and purple and it is hard and has clarity which makes it great for jewelry.

The defeat and death of Tipu, Sultan of Mysore in 1799 led to the Sultan’s magnificent treasury and library being ransacked by the British forces, and the gold coverings of his throne were cut up into small pieces for distribution as prize. The throne was surrounded by a railing with a small jewelled tiger head above each support, and surmounted by a canopy raised on a post at the back. In the front was a life-size tiger head (later presented to William IV, now at Windsor Castle). Above the canopy hovered the huma or bird of paradise. It was ‘supposed to fly constantly in the Air, and never to touch the ground. It is looked upon as a Bird of happy Omen, and that every Head it overshadows will in time wear a Crown’. After the breaking up of the throne the Huma bird was eventually acquired and presented to George III and thus now is part of the Royal collection.

Only one sketch by an artist who actually saw the throne exists today. This is titled the ‘Front view of the throne of the late Tippo Sultun’, and drawn by Thomas Marriot, ADC to the Commander-in-Chief, Madras dated 6 August 1799. Thomas Marriott preceded provided one of the few eyewitness accounts and pictorial representations of Tipu’s throne before it was broken up on the orders of the Prize Committee. In the drawing you can see where the bird would have sat at the top of the canopy.

The Timur ruby came directly to Queen Victoria from India in 1850. The ruby which is actual spinel rather than ruby, weighs 352.5 carats and with the smaller spinels were set by Garrads into an orient inspired necklace in 1853. The stone has historical links to the Mughal Emperors as proven with the inscriptions on it between 1612 and 1771. The connection with the great Asian conqueror Timur arose from a misreading of the inscriptions, but it's possible that Timur's inscription was erased.

The Crescent moon emerald was gifted to Anita Delgado, Princess of Kapurthala by her husband the Maharajah of Kapurthala. She had seen it as part of a decoration on an elephant and she fell in love with it and it became her favorite jewel. This is another of the jewels gifted to his young bride by the Maharajah at their civil wedding ceremony. Highly recommended exhibition and the accompanying book.

REVIEW: Spectacular objects, drawn from a single private collection, will explore the broad themes of tradition and modernity in Indian jewelry. Highlights will include Mughal jades, a rare jeweled gold finial from the throne of Tipu Sultan, and pieces that reveal the dramatic changes that took place in Indian jewelry design during the early 20th century. The exhibition will examine the influence that India had on avant-garde European jewelry made by Cartier and other leading houses and will conclude with contemporary pieces made by JAR and Bhagat, which are inspired by a creative fusion of Mughal motifs and Art Deco ‘Indian’ designs.

REVIEW: A display of 100 spectacular objects from or inspired by the jewelry traditions of the Indian subcontinent. Originating in the 17th century with The Mughal Emperors who collected them for use in Royal ceremonies and court rituals, India has become an international market for precious stones in the last four hundred years. This exhibition - drawn from the recently-formed Al Thani collection - includes rare and unusual examples from across this period, highlighting their value in local culture and the techniques used by goldsmiths in the subcontinent.

It also explores how Indian jewelry has influenced leading European designers and on display is a series of contemporary pieces that reflect this theme. Among the impressive highlights are an Indian turban jewel made for the Maharaja of Nawanagar, a Golconda diamond given to Queen Charlotte by the Nawab of Arcot in 1767, a jade-hilted dagger that belonged to the Shah Jahan who built the Taj Mahal and a jeweled gold tiger’s head finial from the throne of the famed Tipu Sultan of Mysore.

REVIEW: Discover the evolution and enduring influence of Indian jewelry from the Mughal Empire to the modern day. The exhibition will present over 100 spectacular items of Indian and Indian inspired jewelry, including precious jewels of breath-taking quality, exquisite enameling and bejeweled ornaments. Bejeweled Treasures: The Al Thani Collection highlights Indian traditions in design and craftsmanship, focusing on centuries-old techniques and processes. It allows you to see first-hand India’s influence on jewelry made by leading European houses in the 1920s and see contemporary pieces by modern masters, still drawing on those Indian traditions today.

REVIEW: Any self-respecting Mughal court would have a collection of loose gemstones of spectacular size. We see rubies the size of hens eggs and emeralds polished as if they had been a stone tumbler left over from the seventies, no fancy facet cuts here. We’ve all heard of diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds but I confess that if you had asked me what a spinel was I would have hazarded a guess at a small dog. Turns out that a spinel is a red stone mined in Badakhshan in central Asia and the Mughal emperors of the 16th and 17th centuries valued them above all other stones. One fine necklace of pearls and spinels the size of beach pebbles, has a spinel engraved with a tiny inscription to the Mughal emperor Akbar who ruled from 1556 to 1605.

Slowly the craftsmen began to work for customers outside the court and their skill began to be admired in Europe. On display are pieces from jewelers like Cartier which are heavily influenced by the Mughal setting of stones and intricate enamel work. Not everything is antique: at the end of the exhibition diamond earrings made in 2013 seem to float in their case, so fine is the setting. Maybe if save my pennies I might be able to commission the jeweler to make me a pair! Not only are the bejeweled treasures on display beautiful, the staging of this exhibition is a work of art in itself. You feel as if you step into a jewel box, to walk around. Baubles that you can’t touch can sometimes look flat but here they look sparkling and all too covetable.

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: I love this book. I saw the exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum and it was fantastic. The book has reminded me of some of the objects I have forgotten due to the somewhat hurried nature of the day. The pictures are very clear, but nothing can compare to the real thing. The information is just right. If you like this kind of thing it’s a must.

REVIEW: The photographs, as is to be expected, cannot match the brilliance and craftsmanship of the real piece but as a reminder of the exhibition I cannot recommend the book highly enough. The book also has some interesting history information and I particularly liked the photographs of the owners wearing their jewelry.

REVIEW: Beautiful photography and wonderful narrative history of the amazing “Bejewelled Treasures” exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

REVIEW: A beautiful insight into the craftsmanship of these talented craftsmen. A 21st century window into a bygone world of opulence.

REVIEW: Five stars! Just Fabulous!

REVIEW: Beautiful book with lovely Indian miniature paintings and super photographs. A book to cherish.

REVIEW: Great book. Very enjoyable.

REVIEW: Five stars! Beautiful photos, very nice book.

REVIEW: Very good book about a subject that has been rather neglected. Beautiful photographs

SHIPPING & RETURNS/REFUNDS: We always ship books domestically (within the USA) via USPS INSURED media mail (“book rate”). Most international orders cost an additional $17.99 to $48.99 for an insured shipment in a heavily padded mailer. There is also a discount program which can cut postage costs by 50% to 75% if you’re buying about half-a-dozen books or more (5 kilos+). Our postage charges are as reasonable as USPS rates allow. ADDITIONAL PURCHASES do receive a VERY LARGE discount, typically about $5 per book (for each additional book after the first) so as to reward you for the economies of combined shipping/insurance costs. Your purchase will ordinarily be shipped within 48 hours of payment. We package as well as anyone in the business, with lots of protective padding and containers. All of our shipments are fully insured against loss, and our shipping rates include the cost of this coverage (through stamps.com, Shipsaver.com, the USPS, UPS, or Fed-Ex). International tracking is provided free by the USPS for certain countries, other countries are at additional cost. We do offer U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail, Registered Mail, and Express Mail for both international and domestic shipments, as well United Parcel Service (UPS) and Federal Express (Fed-Ex). Please ask for a rate quotation. Please note for international purchasers we will do everything we can to minimize your liability for VAT and/or duties. But we cannot assume any responsibility or liability for whatever taxes or duties may be levied on your purchase by the country of your residence. If you don’t like the tax and duty schemes your government imposes, please complain to them. We have no ability to influence or moderate your country’s tax/duty schemes. If upon receipt of the item you are disappointed for any reason whatever, I offer a no questions asked 30-day return policy. Send it back, I will give you a complete refund of the purchase price; 1) less our original shipping/insurance costs, 2) less any non-refundable fees imposed by eBay. Please note that eBay may not refund payment processing fees on returns beyond a 30-day purchase window. So except for shipping costs, we will refund all proceeds from the sale of a return item, eBay may not always follow suit. Obviously we have no ability to influence, modify or waive eBay policies. ABOUT US: Prior to our retirement we used to travel to Eastern Europe and Central Asia several times a year seeking antique gemstones and jewelry from the globe’s most prolific gemstone producing and cutting centers. Most of the items we offer came from acquisitions we made in Eastern Europe, India, and from the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean/Near East) during these years from various institutions and dealers. Much of what we generate on Etsy, Amazon and Ebay goes to support worthy institutions in Europe and Asia connected with Anthropology and Archaeology. Though we have a collection of ancient coins numbering in the tens of thousands, our primary interests are ancient/antique jewelry and gemstones, a reflection of our academic backgrounds. Though perhaps difficult to find in the USA, in Eastern Europe and Central Asia antique gemstones are commonly dismounted from old, broken settings – the gold reused – the gemstones recut and reset. Before these gorgeous antique gemstones are recut, we try to acquire the best of them in their original, antique, hand-finished state – most of them originally crafted a century or more ago. We believe that the work created by these long-gone master artisans is worth protecting and preserving rather than destroying this heritage of antique gemstones by recutting the original work out of existence. That by preserving their work, in a sense, we are preserving their lives and the legacy they left for modern times. Far better to appreciate their craft than to destroy it with modern cutting. Not everyone agrees – fully 95% or more of the antique gemstones which come into these marketplaces are recut, and the heritage of the past lost. But if you agree with us that the past is worth protecting, and that past lives and the produce of those lives still matters today, consider buying an antique, hand cut, natural gemstone rather than one of the mass-produced machine cut (often synthetic or “lab produced”) gemstones which dominate the market today. We can set most any antique gemstone you purchase from us in your choice of styles and metals ranging from rings to pendants to earrings and bracelets; in sterling silver, 14kt solid gold, and 14kt gold fill. When you purchase from us, you can count on quick shipping and careful, secure packaging. We would be happy to provide you with a certificate/guarantee of authenticity for any item you purchase from us. There is a $3 fee for mailing under separate cover. I will always respond to every inquiry whether via email or eBay message, so please feel free to write.