Silver Roman Denarius of Emperor Severus Alexander with Depiction of the Emperor in Military Dress with Spear and Globe – 225 A.D.

OBVERSE INSCRIPTION: IMP C M AVR SEV ALEXAND AVG.

OBVERSE DEPICTION: The head of Severus Alexander, right, draped, laureate crown (laurel wreath).

REVERSE INSCRIPTION: P M TR P IIII COS PP.

REVERSE DEPICTION: The Emperor Severus Alexander standing right with globe in right hand and a reversed spear (point down) in left hand.

ATTRIBUTION: City of Rome Mint in 225 A.D.

SIZE/MEASUREMENTS:

Diameter: 20*19 millimeters.

Weight: 2.92 grams.

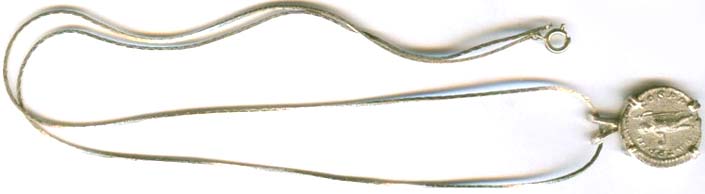

NOTE: Coin is mounted free of charge into your choice of pendant settings (shown in sterling silver pendant), and includes a sterling silver chain in your choice of 16", 18", or 20" length, (details below or click here). We can reverse coin in mounting if you prefer opposite side showing front.

DETAIL: This is a very handsome and fairly uncommon silver denarius produced in the city of Rome itself sometime during the year 225 A.D. It is in exceptionally good condition, only very light wear from circulation in ancient Rome, the legends and themes very clear and distinct. It was well struck both front and back. As one can see, the strike was a little off-center; the obverse high and to the left, the reverse a little low and to the right. Nonetheless the strike was captured in its entirety, consequence of very generously-sized planchet (coin blank) considerably larger than what was typical for the era. Consequentially and unlike most coins of the era, the strike caught the entirely of both the legends and the themes, and this is applicable to both the obverse as well as the reverse. It is without a doubt an exceptional and superior strike.

Some of the Latin characters (letters) making up the reverse legend are a little indistinct, i.e., in low profile. But this is quite ordinary and commonplace. The coins were of course struck by hand, and little bits of metal (“detritus”) would slowly clog up the finer features of the coin, especially the engraved letters, and from time to time they would have to be re-engraved. If you look closely at the obverse at the very beginning of the reverse inscription (and then the three I’s making up the number III), you’ll see that a few of the letters in the die were a bit clogged up when the coin was struck, and so some of the Latin characters are in low profile. This is an interesting though certainly not unique or uncommon feature of this specimen, and absolutely not detrimental, merely simply a characteristic of the coinage of the era.

Naturally inasmuch as these coins were produced by hand, and it is the rule, not the exception, to find them struck off-center, on irregular, undersized planchets (blanks), or with excessively worn or clogged dies, and consequentially are more often than not missing portions of the legends and/or themes (depictions). Nonetheless given the fairly well-centered strike and very low level of circulatory wear, this is without a doubt a superb specimen. The obverse of the coin depicts the head of Roman Emperor Severus Alexander, depicted draped and with laureate crown; and the legend “IMP C M AVR SEV ALEXAND ”. “M AVR SEV ALEXAND” of course refers to the Emperor’s full name, Marcus Aurelis Severus Alexander. The “M” is obviously the initial for “Marcus”. “AVR” is short for “Aurelian”; “V” as there is no “U” in Roman Latin. “SEV” is short for “Severus”, and these abbreviations are followed by “ALEXAND”, short for “Alexander”.

The “IMP” preface to his name is an abbreviation for “Imperator”. Imperator was originally a title or acclamation awarded to victorious generals in the field during the Republic Period (before Julius Caesar). Throughout the history of Republican Rome, the title was bestowed upon an especially able general who had won an enormous victory. Traditionally it was the troops in the field that proclaimed a man imperator – the first step in the process of the general applying to the senate for a triumph (a ceremony both civil and religious held in Rome itself to publicly honor the general and to display/parade the glories and trophies of Roman victory).

Imperatrix was the title of the wife an Imperator. After Augustus Octavian (Julius Caesar’s successor) had established the hereditary, one-man rule in Rome that we refer to as the Imperial Roman Empire, the title Imperator was restricted to the emperor and members of his immediate family. If a general who was not part of the imperial family was acclaimed by his troops as Imperator, it was tantamount to a declaration of rebellion or civil war against the ruling emperor. Though the title Augustus is probably the closest Latin equivalent to the English word emperor; it was eventually the term Imperator which became the root of the English word “Imperial”.

The “C” preceding his name (and following “IMP”) refers to the title “Caesar”, which was a title of imperial character used by either the Emperor or the heir apparent of the Emperor – though in the fragmenting later Roman Empire it was used to refer to the “junior” sub-emperors; inferior to “Augustus”, or the “senior” Emperor. The title’s origin was the name of Julius Caesar, the famous Roman General and Dictator. This came about when Octavius, eventually the first Emperor of Rome, was named by Julius Caesar posthumously (in his will) as his heir and adopted son. Octavius adopted the name “Caesar” in order to emphasize his relationship with his Uncle, Julius Caesar.

Eventually the term evolved into part of a title, “Imperator Caesar Augustus”, when Octavious adopted his nephew Tiberius Claudius Nero as his successor, renaming him "Tiberius Iulius Caesar". The precedent was set: the Emperor designated his successor by adopting him and giving him the name "Caesar". The title was occasionally accompanied by that of “Princeps Iuventutis” (literally "Prince of Youth"). After some variation among the earliest Emperors, the title of the heir apparent evolved into NN Caesar before accession and Imperator Caesar NN Augustus after accession. A later evolution expanded the title to “NN Nobilissimus Caesar” (“Most Noble Caesar") rather than simply NN Caesar. Ultimately to this the additional titles “Pius Felix” ("the Pious and Blessed") and “Invictus” ("the Unconquered") were added.

The suffix “AVG” was an abbreviation for Augustus. The term “Augustus” is Latin for “majestic” (thus the honorific salutation “your majesty”). However the term “Augustus” in the common vernacular of the Roman Empire became synonymous with the Emperor. The first "Augustus" (and first man counted as a Roman Emperor) was Octavius, Julis Caesar’s nephew and heir. Octavian was given the title of Augustus by the Senate in 27 B.C. Over the next forty years, Caesar Augustus literally set the standard by which subsequent Emperors would be recognized, accumulating various offices and powers and making his own name ("Augustus") identifiable with the consolidation of these powers under a single person. Although the name signified nothing in constitutional theory, it was recognized as representing all the powers that Caesar Augustus eventually accumulated.

Caesar Augustus also set the standard by which Roman Emperors were named. The three titles used by the majority of Roman Emperors; “Imperator”, “Caesar”, and “Augustus” were all used personally by Caesar Augustus (he officially styled himself "Imperator Caesar Augustus"). However of the name "Augustus" was unique to the Emperor himself (though the Emperor's mother or wife could bear the name "Augusta"). But others could and did bear the titles "Imperator" and "Caesar". Later useage saw the Emperor adding the additional titles “Pius Felix (“pious and blessed”) and “Invictus” (“unconquered”) in addition to the title “Augustus”). In this usage, by signifying the complete assumption of all Imperial powers, "Augustus" became roughly synonymous with “Emperor” in modern language. As the Roman Empire began splintering, Augustus came to be the title applied to the senior Emperor, while the title “Caesar” came to refer to his “junior” sub-Emperors.

The obverse of the coin portrays Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander. He was born Gessius Bassianus Alexianus in 208 A.D. in Phoenicia, and was the son of Julia Mamaea and Gessius Marcianus. Like his cousin Emperor Elagabalus, he was a hereditary Priest of Baal, though he was not the religious fanatic Elegabalus was. In 221 A.D. he was adopted by Emperor Elagabalus, his cousin, and given the title of Caesar, as part of behind-the-throne manipulations by his grandmother, the Empress Julia Maesa. Grandmother Julia Maesa even went so far as to deliberately start rumors that he was the illegitimate offspring of the Emperor Caracalla. Caracalla had been popular with the army; but more importantly he was the direct offspring of the beloved and deified Emperor Septimius Severus. Thus even as an (alleged) illegitimate grandson, Severus Alexander still gained stature.

After Emperor Elagabalus burned through a succession of four quick marriages (all less than a year’s duration), and had demonstrated a proclivity toward cruelty and religious fanaticism, it became clear to Julia Elagabalus (also one of her grandsons) was not going to be the person to restore the Severan Dynasty (as in Septimius Severus 193-211 AD) to its former glory. Julia Maesa arranged for Severus Alexander to be adopted by Elegabalus and named Caesar, and then with Severus’s Mother (Julia Mamaea) arranged to have Elagabalus and his mother (Julia Maesa’s own daughter) murdered by the Praetorian Guard a year later. Severus Alexander was proclaimed Emperor by the same Praetorian Guard. Despite the bloody route to the throne, and his young age (12 1/2 when he assumed the throne – the youngest Emperor in Rome’s history), Alexander ruled the empire wisely, and the condition of the empire improved. His grandmother, Julia Maesa, died shortly after his ascension. However Alexander's strict mother held considerable influence over the Emperor. As had “grandmother” been before her, Severus’s mother was the real power behind the throne, and this led to resentment within the command structure of the army.

The first nine years of Alexander's reign was untroubled by foreign conflict. But in 232 A.D. Alexander had to take the field against the Sassanians who had recently taken by conquest Parthia, and were threatening Syria and Cappadocia. The campaign against the Sassanians met with only limited success, a stalemate, and disturbances on the German frontier soon necessitated Alexander's presence there. The German’s had taken advantage of the redeployment of Roman troops to the East, and Severus’s Generals planned a grand campaign in retribution. However Severus Alexander preferred to negotiate for peace by buying off the enemy. This policy outraged the soldiers, and a group of mutinous Pannonian soldiers proclaimed Maximinus, one of their commanders, Emperor. Severus Alexander and his mother Julia were murdered at their camp near Mainz on March 22, 235 A.D., much as Alexander's predecessor, Elagabalus and his mother had been murdered fourteen years prior. And thus ended the Severan Dynasty of Imperial Rome.

The emperor is depicted “laureate”, or wearing a wreath or crown composed of laurel, or “bay leaves”. This wreath of laurel leaves is an attribute of the Graeco-Roman God Apollo, and is a symbol of victory. In Greek Mythology, Apollo fell in love with the legendary mountain nymph Daphene. Daphene, anxious to escape Apollo’s amorous interests, asked the Gods of Olympus to change her into a bay tree. Thereafter Apollo always wore a laurel wreath made from the leaves of her sacred tree to show is never failing love for her. Apollo also declared that wreaths were to be awarded to victors, both in athletic competitions and poetic meets under his care.

Laurel wreaths became the prize awarded in athletic, musical, and poetic competitions. For instance by the 6th century B.C., the winners of the ancient Greek Pythian Games (forerunner of the Olympics and held every four years at Delphi) were awarded a wreath of laurel leaves. Ancient Greek coins from at least as far back as the second century B.C. depict laurel wreaths worn by not only Apollo, but also Athena, Saturn, Jupiter, Victory (Nike), and Salus. Eventually the custom of awarding a wreath of laurel leaves was extended from victors of athletic events to the victors of military endeavors. The symbolism was inherited (or mimicked) by the Romans, to whom the bestowal of a laurel wreath became the sign of a victorious general acclaimed by his troops.

After defeating Pompey, the Roman Senate not only voted Julius Caesar Imperator for life, but also awarded him the right to wear the laurel wreath in perpetuity. From that point on it is said that Julius Caesar always appeared in public laureate, and all of his coinage depicted Julius Caesar wearing the laurel leaf crown. Thus the laurel leaf crown became associated not only with the victorious general, but became a symbol of the office of Caesar and Imperator. There were other types of wreaths in Graeco-Roman Mythology as well. Dionysus was oftentimes depicted either with a wreath of ivy or with a wreath composed of grape leaves. Zeus was oftentimes depicted with a wreath of oak leaves, and wreathes of roses became associated with Aphrodite. As well, funeral wreaths became a Roman custom, and were often carved into the decorative elements of a sarcophagus.

The reverse of the coin portrays the Emperor in military garb, with a globe in his outstretched left hand, and a spear point down in his right hand. The symbolism of the military garb and the spear, the emperor holding the “world” in his hands, is unmistakable and requires no explanation. It is a blunt and direct statement of Roman military domination over the world of the Mediterranean. The reverse legend the coin bears is P M TR P VI COS II PP. “P M” is an abbreviation for “Pontifex Maximus”. As Augustus, an acclamation or title oftentimes attributed to the Emperor was that of as “Pontifex Maximus”, literally "greatest bridgemaker", the significance being that he was the chief priest of the Roman state religion. From 382 A.D. onwards this title has been held by the Pope in Rome. Prior to Octavious Augustus Julius Caesar (in the Roman Republic) the Pontifex Maximus was the head of the pagan Roman Religion, the most important of the priests (pontifices) of the sacred college (Collegium Pontificum). However with the establishment of Empire, Julius Caesar, then Octavius Augustus, and then each Roman Emperor afterwards held the title Pontifex Maximus himself, as the Roman Emperor became deified, i.e., a living god and the apex of the Roman religion.

The reverse legend continues, “TR P IIII”, an abbreviation for Tribunicia Potestas (the “IIII” indicates the fourth term). As Augustus, an acclamation or title oftentimes attributed to the Emperor was that of Tribunicia Potestas, literally "tribunician power”. As such the Emperor he had personal inviolability (sacrosanctitas) and the right to veto any act or proposal by any magistrate within Rome, the authority to convene the Senate, and the right to exercise capital punishment in the course of the performance of his duties. Of course constitutionally Tribunes were meant to represent the common man, the plebians. Since it was legally impossible for a patrician to be a tribune of the people, the first Roman "Emperor", Caesar Augustus, was instead offered of the powers of the tribunate without actually holding the office. This formed one of the main constitutional basis of Augustus' authority, and the power was generally “renewed” annually by successive Emperors.

The abbreviation “COS” is an abbreviation indicating (the first) term as Consul. As Augustus, an acclamation or title oftentimes attributed to the Emperor was that of Consul. As Consular Imperium (Imperial Consul) he had authority equal to the official chief magistrates within Rome. He had authority greater than the chief magistrates outside of the city of Rome, and thus outranked all provincial governors and was also supreme commander of all Roman Legions. Originally “Consul” was the highest elected office of the Roman Republic (ultimately it was an appointed office under the Empire). Under the Republic two consuls (with executive power) were elected each year, serving together with veto power over each other's actions.

The office of consul was believed to date back to the traditional establishment of the Republic in 509 B.C. Consuls executed both religious and military duties. During times of war, the primary criterion for consul was military skill and reputation, but at all times the selection was politically charged. Initially only patricians could be consuls, but later the plebeians won the right to stand for election. With the passage of time, the consulship became the penultimate endpoint of the sequence of offices pursued by the ambitious Roman. When Octavius Augustus, heir to Julius Caesar, established the Empire; he changed the nature of the office, stripping it of most of its powers. While still a great honor and a requirement for other offices, about half of the men who held the rank of Praetor would also reach the consulship.

However under the Empire, Emperors frequently appointed themselves, protégés, or relatives without regard to the requirements of office. For example, the Emperor Honorius was given the consulship at birth. One of the reforms of Constantine the Great was to assign one of the consuls to the city of Rome and the other to Constantinople. When the Roman Empire was divided into two halves on the death of Theodosius I, the emperor of each half acquired the right of appointing one of the consuls. As a result, after the formal end of the Roman Empire in the West, for many years thereafter there would be only one Consul of Rome. Finally in the reign of Justinian the consulship was allowed die; first in Rome in 534 A.D.; then in Constantinople in 541 A.D.

Finally the legend ends with the abbreviation “PP”. "PP" stands for “Pater Patriae”, literally "father of the country", also sometimes seen as “Parens Patriae”, meaning "Father of the Fatherland". It does not imply a great role in the foundation of the state (such as “George Washington Father of America”) so much as a great contribution to the preservation and integrity of the state. Like all official honorific titles of the Roman Republic, the honor of being called pater patriae was conferred by the Roman Senate. It was first awarded to the great orator Marcus Tullius Cicero for his part in the suppression of the Catilinarian conspiracy during his consulate in 63 BC. It was next awarded to Julius Caesar, who as dictator was sole master of the Roman world. The Senate voted the title to Caesar Augustus in 2 BC, but it did not become an “automatic” part of the “bundle” of the Imperial powers and honours (Imperator, Caesar, Augustus, Princeps Senatus, Pontifex Maximus, tribunicia potestas); The Senate eventually conferred the title on many Roman Emperors, often only after many years of rule (unless the new Emperor were particularly esteemed by the senators, as in the case of Nerva); as a result, many of the short-lived Emperors never received the title. In the case of Severus Alexander, the Senate rather incongruously awarded the title as soon as he ascended the throne at age 12 1/2.

Your purchase includes, upon request, mounting of this coin in either pendant style “a” or “d” as shown here. Pendant style “a” is a clear, airtight acrylic capsule designed to afford your ancient coin maximum protection from both impact damage and degradation. It is the most “politically correct” mounting. Style “d” is a sterling silver pendant. Either pendant styles include a sterling silver chain (16", 18", or 20"). Upon request, there are also an almost infinite variety of other pendants which might well suit both you and your ancient coin pendant, and include both sterling silver and solid 14kt gold mountings, including those shown here. As well, upon request, we can also make available a huge variety of chains in lengths from 16 to 30 inches, in metals including sterling silver, 14kt gold fill, and solid 14kt gold.

HISTORY OF COINAGE: Coins came into being during the seventh century B.C. in Lydia and Ionia, part of the Greek world, and were made from a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. Each coin blank was heated and struck with a hammer between two engraved dies. Unlike modern coins, they were not uniformly round. Each coin was wonderfully unique. Coinage quickly spread to the island and city states of Western Greece. Alexander the Great (336-323 B.C.) then spread the concept of coinage throughout the lands he conquered. Today ancient coins are archaeological treasures from the past, and on many occasions have provided profound new knowledge to historians.

They were buried for safekeeping because of their value and have been slowly uncovered throughout modern history. Oftentimes soldiers the night before battle would bury their coins and jewelry, hoping and believing that they would live long enough to recover them, and to return to their family. Killed in battle, these little treasure hoards remain until today scattered throughout Western and Eastern Europe, even into the Levant and Persia. As well, everyone from merchants to housewives found the safest place to keep their savings was buried in a pot, or in some other secretive location. If they met an unexpected end, the whereabouts of the merchants trade goods or the household's sugar jar money might never be known.

Recently a commercial excavation for a new building foundation in London unearthed a Roman mosaic floor. When archaeologists removed the floor, they found 7,000 silver denarii secreted beneath the floor. Even the Roman mints buried their produce. There were over 300 mints in the Roman Empire striking coinage. Hoards of as many as 40,000 coins have been found in a single location near these ancient sites. Ancient coins reflect the artistic, political, religious, and economic themes of their times. The acquisition of ancient coins is a unique opportunity to collect art which has been appreciated throughout the centuries.

Coins of the Roman Empire most frequently depicted the Emperor on the front of the coins, and were issued in gold, silver, and bronze. The imperial family was also frequently depicted on the coinage, and, in some cases, coins depicted the progression of an emperor from boyhood through maturity. The reverse side of often served as an important means of political propaganda, frequently extolling the virtues of the emperor or commemorating his victories. Many public works and architectural achievements such as the Coliseum and the Circus Maximus were also depicted.

As well, important political events such as alliances between cities were recorded on coinage. Many usurpers to the throne, otherwise unrecorded in history, are known only through their coins. Interestingly, a visually stunning portrayal of the decline of the Roman Empire is reflected in her coinage. The early Roman bronze coins were the size of a half-dollar. Within 100-150 years those had shrunk to the size of a nickel. And within another 100-150 years, to perhaps half the size of a dime. At the height of the Roman Empire there were over 400 mints producing coinage, in locations as diverse as Britain, Africa, and the Near East. The annual produce of these mints is estimated to have been between one and two billion coins.

ANCIENT ROMAN HISTORY: One of the greatest civilizations of recorded history was the ancient Roman Empire. The Roman civilization, in relative terms the greatest military power in the history of the world, was founded in the 8th century (B.C.) on seven hills alongside Italy’s Tiber River. By the 4th Century (B.C.) the Romans were the dominant power on the Italian Peninsula, having defeated the Etruscans, Celts, Latins, and Greek Italian colonies. In the 3rd Century (B.C.) the Romans conquered Sicily, and in the following century defeated Carthage, and controlled Greece.

Throughout the remainder of the 2nd Century (B.C.) the Roman Empire continued its gradual conquest of the Hellenistic (Greek Colonial) World by conquering Syria and Macedonia; and finally came to control Egypt and much of the Near East and Levant (Holy Land) in the 1st Century (B.C.). The pinnacle of Roman power was achieved in the 1st Century (A.D.) as Rome conquered much of Britain and Western Europe.

At its peak, the Roman Empire stretched from Britain in the West, throughout most of Western, Central, and Eastern Europe, and into Asia Minor. For a brief time, the era of “Pax Romana”, a time of peace and consolidation reigned. Civilian emperors were the rule, and the culture flourished with a great deal of liberty enjoyed by the average Roman Citizen. However within 200 years the Roman Empire was in a state of steady decay, attacked by Germans, Goths, and Persians. The decline was temporarily halted by third century Emperor Diocletian.

In the 4th Century (A.D.) the Roman Empire was split between East and West. The Great Emperor Constantine again managed to temporarily arrest the decay of the Empire, but within a hundred years after his death the Persians captured Mesopotamia, Vandals infiltrated Gaul and Spain, and the Goths even sacked Rome itself. Most historians date the end of the Western Roman Empire to 476 (A.D.) when Emperor Romulus Augustus was deposed. However the Eastern Roman Empire (The Byzantine Empire) survived until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 A.D.

In the ancient world valuables such as coins and jewelry were commonly buried for safekeeping, and inevitably the owners would succumb to one of the many perils of the ancient world. Oftentimes the survivors of these individuals did not know where the valuables had been buried, and today, thousands of years later (occasionally massive) caches of coins and rings are still commonly uncovered throughout Europe and Asia Minor.

Throughout history these treasures have been inadvertently discovered by farmers in their fields, uncovered by erosion, and the target of unsystematic searches by treasure seekers. With the introduction of metal detectors and other modern technologies to Eastern Europe in the past three or four decades, an amazing number of new finds are seeing the light of day thousands of years after they were originally hidden by their past owners. And with the liberalization of post-Soviet Eastern Europe, new sources have opened eager to share in these ancient treasures.

HISTORY OF SILVER: After gold, silver is the metal most widely used in jewelry and the most malleable. The oldest silver artifacts found by archaeologists date from ancient Sumeria about 4,000 B.C. At many points in the ancient world, it was actually more costly than gold, particularly in ancient Egypt. Silver is found in native form (i.e., in nuggets), as an alloy with gold (electrum), and in ores containing sulfur, arsenic, antimony or chlorine. Much of the silver originally found in the ancient world was actually a natural alloy of gold and silver (in nugget form) known as “electrum”.

The first large-scale silver mines were in Anatolia (ancient Turkey) and Armenia, where as early as 4,000 B.C. silver was extracted from lead ores by means of a complicated process known as “smelting”. Even then the process was not perfect, as ancient silver does contain trace elements, typically lead, gold, bismuth and other metals, and as much as a third of the silver was left behind in the slag. However measuring the concentrations of the “impurities” in ancient silver can help the forensic jewelry historian in determining the authenticity of classical items. From Turkey and Armenia silver refining technology spread to the rest of Asia Minor and Europe.

By about 2,500 B.C. the Babylonians were one of the major refiners of silver. Silver “treasures” recovered by archaeologists from the second and third millenniums demonstrate the high value the ancient Mediterranean and Near East placed upon silver. Some of the richest burials in history uncovered by archaeologists have been from this time frame, that of Queen Puabi of Ur, Sumeria (26th century B.C.); Tutankhamun (14th century B.C.), and the rich Trojan (25th century B.C.) and Mycenaean (18th century B.C.) treasures uncovered by Heinrich Schliemann.

The ancient Egyptians believed that the skin of their gods was composed of gold, and their bones were thought to be of silver. When silver was introduced into Egypt, it probably was more valuable than gold (silver was rarer and more valuable than gold in many Mesoamerican cultures as well). In surviving inventories of valuables, items of silver were listed above those of gold during the Old Kingdom. Jewelry made of silver was almost always thinner than gold pieces, as indicated by the bracelets of the 4th Dynasty (about 2,500 B.C.) Queen Hetephere I, in marked contrast to the extravagance of her heavy gold jewelry.

A silver treasure excavated by archaeologists and attributable to the reign of Amenemhat II who ruled during the 12th Dynasty (about 1900 B.C.), contained fine silver items which were actually produced in Crete, by the ancient Minoans. When the price of silver finally did fall due to more readily available supplies, for at least another thousand years (through at least the 19th dynasty, about 1,200 B.C.) the price of silver seems to have been fixed at half that of gold. Several royal mummies attributable to about 1,000 B.C. were even entombed in solid silver coffins.

Around 1,000 B.C. Greek Athenians began producing silver from the Laurium mines, and would supply much of the ancient Mediterranean world with its silver for almost 1,000 years. This ancient source was eventually supplemented around 800 B.C. (and then eventually supplanted) by the massive silver mines found in Spain by the Phoenicians and their colony (and ultimate successors) the Carthaginians (operated in part by Hannibal’s family). With the defeat of Carthage by Rome, the Romans gained control of these vast deposits, and mined massive amounts of silver from Spain, stripping entire forests regions for timber to fuel smelting operations. In fact, it was not until the Middle Ages that Spain’s silver mines (and her forests) were finally exhausted.

Although known during the Copper Age, silver made only rare appearances in jewelry before the classical age. Despite its infrequent use as jewelry however, silver was widely used as coinage due to its softness, brilliant color, and resistance to oxidation. Silver alloyed with gold in the form of “electrum” was coined to produce money around 700 B.C. by the Lydians of present-day Turkey. Having access to silver deposits and being able to mine them played a big role in the classical world. Actual silver coins were first produced in Lydia about 610 B.C., and subsequently in Athens in about 580 B.C.

Many historians have argued that it was the possession and exploitation of the Laurium mines by the Athenians that allowed them to become the most powerful city state in Greece. The Athenians were well aware of the significance of the mining operations to the prosperity of their city, as every citizen had shares in the mines. Enough silver was mined and refined at Laurium to finance the expansion of Athens as a trading and naval power. One estimate is that Laurium produced 160 million ounces of silver, worth six billion dollars today (when silver is by comparison relatively cheap and abundant). As the production of silver from the Laurium mines ultimately diminished, Greek silver production shifted to mines in Macedonia.

Silver coinage played a significant role in the ancient world. Macedonia’s coinage during the reign of Philip II (359-336 B.C.) circulated widely throughout the Hellenic world. His famous son, Alexander the Great (336-323 B.C.), spread the concept of coinage throughout the lands he conquered. For both Philip II and Alexander silver coins became an essential way of paying their armies and meeting other military expenses. They also used coins to make a realistic portrait of the ruler of the country. The Romans also used silver coins to pay their legions. These coins were used for most daily transactions by administrators and traders throughout the empire.

Roman silver coins also served as an important means of political propaganda, extolling the virtues of Rome and her emperors, and continued in the Greek tradition of realistic portraiture. As well, many public works and architectural achievements were also depicted (among them the Coliseum, the Circus Maximus). In addition many important political events were recorded on the coinage. Roman coins depicted the assassination of Julius Caesar, alliances between cities, between emperors, between armies, etc. And many contenders for the throne of Rome are known only through their coinage.

Silver was also widely used as ornamental work and in other metal wares. In ancient cultures, especially in Rome, silver was highly prized for the making of plate ware, household utensils, and ornamental work. The stability of Rome’s economy and currency depended primarily on the output of the silver mines in Spain which they had wrested from the Carthaginians. In fact many historians would say that it was the control of the wealth of these silver mines which enabled Rome to conquer most of the Mediterranean world. When in 55 B.C. the Romans invaded Britain they were quick to discover and exploit the lead-silver deposits there as well.

Only six years later they had established many mines and Britain became another major source of silver for the Roman Empire. It is estimated that by the second century A.D., 10,000 tons of Roman silver coins were in circulation within the empire. That’s about 3½ billion silver coins (at the height of the empire, there were over 400 mints throughout the empire producing coinage). That’s ten times the total amount of silver available to Medieval Europe and the Islamic world combined as of about 800 A.D. Silver later lost its position of dominance to gold, particularly in the chaos following the fall of Rome. Large-scale mining in Spain petered out, and when large-scale silver mining finally resumed four centuries after the fall of Rome, most of the mining activity was in Central Europe.

By the time of the European High Middle Ages, silver once again became the principal material used for metal artwork. Huge quantities of silver from the New World also encouraged eager buyers in Europe, and enabled the Spanish to become major players in the late Medieval and Renaissance periods. Unlike the ores in Europe which required laborious extraction and refining methods to result in pure silver, solid silver was frequently found as placer deposits in stream beds in Spain’s “New World” colonies, reportedly in some instances solid slabs weighing as much as 2,500 pounds. Prior to the discovery of massive silver deposits in the New World, silver had been valued during the Middle Ages at about 10%-15% of the value of gold.

In 15th century the price of silver is estimated to have been around $1200 per ounce, based on 2010 dollars. The discovery of massive silver deposits in the New World during the succeeding centuries has caused the price to diminish greatly, falling to only 1-2% of the value of gold. The art of silver work flourished in the Renaissance, finding expression in virtually every imaginable form. Silver was often plated with gold and other decorative materials. Although silver sheets had been used to overlay wood and other metals since ancient Greece, an 18th-century technique of fusing thin silver sheets to copper brought silver goods called Sheffield plate within the reach of most people.

At the same time the use of silver in jewelry making had also started gaining popularity in the 17th century. It was often as support in settings for diamonds and other transparent precious stones, in order to encourage the reflection of light. Silver continued to gain in popularity throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and by the 20th century competed with gold as the principal metal used in the manufacture of jewelry. Silver has the highest thermal and electrical conductivity of any metal, and one of the highest optical reflectivity values. It has a brilliant metallic luster, is very ductile and malleable, only slightly harder than gold, and is easily worked and polished.

When used in jewelry, silver is commonly alloyed to include 7.5% copper, known as “sterling silver”, to increase the hardness and reduce the melting temperature. Silver jewelry may be plated with 99.9% pure ‘Fine Silver’ to increase the shine when polished. It may also be plated with rhodium to prevent tarnish. Virtually all gold, with the exception of 24 carat gold, includes silver. Most gold alloys are primarily composed of only gold and silver. Throughout the history of the ancient world, gemstones were believed capable of curing illness, possessed of valuable metaphysical properties, and to provide protection. Found in Egypt dated 1500 B. C., the "Papyrus Ebers" offered one of most complete therapeutic manuscripts containing prescriptions using gemstones and minerals.

Gemstones were not only valued for their medicinal and protective properties, but also for educational and spiritual enhancement. Precious minerals were likewise considered to have medicinal and “magical” properties in the ancient world. In its pure form silver is non toxic, and when mixed with other elements is used in a wide variety of medicines. Silver ions and silver compounds show a toxic effect on some bacteria, viruses, algae and fungi. Silver was widely used before the advent of antibiotics to prevent and treat infections, silver nitrate being the prevalent form. Silver Iodide was used in babies' eyes upon birth to prevent blinding as the result of bacterial contamination.

Silver is still widely used in topical gels and impregnated into bandages because of its wide-spectrum antimicrobial activity. The recorded use of silver to prevent infection dates to ancient Greece and Rome. Hippocrates, the ancient (5th century B.C.) Greek "father of medicine" wrote that silver had beneficial healing and anti-disease properties. The ancient Phoenicians stored water, wine, and vinegar in silver bottles to prevent spoiling. These uses were “rediscovered” in the Middle Ages, when silver was used for several purposes; such as to disinfect water and food during storage, and also for the treatment of burns and wounds as a wound dressing.

The ingestion of colloidal silver was also believed to help restore the body's “electromagnetic balance” to a state of equilibrium, and it was believed to detoxify the liver and spleen. In the 19th century sailors on long ocean voyages would put silver coins in barrels of water and wine to keep the liquid potable. Silver (and gold) foil is also used through the world as a food decoration. Traditional Indian dishes sometimes include the use of decorative silver foil, and in various cultures silver dragée (silver coated sugar balls) are used to decorate cakes, cookies, and other dessert items.

Domestic shipping (insured first class mail) is included in the price shown. Domestic shipping also includes USPS Delivery Confirmation (you might be able to update the status of your shipment on-line at the USPS Web Site). Canadian shipments are an extra $17.99 for Insured Air Mail; International shipments are an extra $21.99 for Air Mail (and generally are NOT tracked; trackable shipments are EXTRA). ADDITIONAL PURCHASES do receive a VERY LARGE discount, typically about $5 per item so as to reward you for the economies of combined shipping/insurance costs. Your purchase will ordinarily be shipped within 48 hours of payment. We package as well as anyone in the business, with lots of protective padding and containers.

We do NOT recommend uninsured shipments, and expressly disclaim any responsibility for the loss of an uninsured shipment. Unfortunately the contents of parcels are easily “lost” or misdelivered by postal employees – even in the USA. If you intend to pay via PayPal, please be aware that PayPal Protection Policies REQUIRE insured, trackable shipments, which is INCLUDED in our price. International tracking is at additional cost. We do offer U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail, Registered Mail, and Express Mail for both international and domestic shipments, as well United Parcel Service (UPS) and Federal Express (Fed-Ex). Please ask for a rate quotation. We will accept whatever payment method you are most comfortable with. If upon receipt of the item you are disappointed for any reason whatever, I offer a no questions asked return policy. Send it back, I will give you a complete refund of the purchase price (less our original shipping costs).

Most of the items I offer come from the collection of a family friend who was active in the field of Archaeology for over forty years. However many of the items also come from purchases I make in Eastern Europe, India, and from the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean/Near East) from various institutions and dealers. Though I have always had an interest in archaeology, my own academic background was in sociology and cultural anthropology. After my retirement however, I found myself drawn to archaeology as well. Aside from my own personal collection, I have made extensive and frequent additions of my own via purchases on Ebay (of course), as well as many purchases from both dealers and institutions throughout the world – but especially in the Near East and in Eastern Europe. I spend over half of my year out of the United States, and have spent much of my life either in India or Eastern Europe. In fact much of what we generate on Yahoo, Amazon and Ebay goes to support The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, as well as some other worthy institutions in Europe connected with Anthropology and Archaeology.

I acquire some small but interesting collections overseas from time-to-time, and have as well some duplicate items within my own collection which I occasionally decide to part with. Though I have a collection of ancient coins numbering in the tens of thousands, my primary interest is in ancient jewelry. My wife also is an active participant in the “business” of antique and ancient jewelry, and is from Russia. I would be happy to provide you with a certificate/guarantee of authenticity for any item you purchase from me. There is a $2 fee for mailing under separate cover. Whenever I am overseas I have made arrangements for purchases to be shipped out via domestic mail. If I am in the field, you may have to wait for a week or two for a COA to arrive via international air mail. But you can be sure your purchase will arrive properly packaged and promptly – even if I am absent. And when I am in a remote field location with merely a notebook computer, at times I am not able to access my email for a day or two, so be patient, I will always respond to every email. Please see our "ADDITIONAL TERMS OF SALE."