"An Archaeology of the Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms" (Second Edition) by C. J. Arnold.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with printed, laminate covers (no dustjacket, as issued). Publisher: Routledge (1997). Pages: 260. Size: 9¼ x 6¼ x ¾ inches; 1¼ pounds. Summary: "An Archaeology of the Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms" is a volume which offers an unparalleled view of the archaeological remains of the period. Using the development of the kingdoms as a framework, this study closely examines the wealth of material evidence and analyzes its significance to our understanding of the society that created it. From our understanding of the migrations of the Germanic peoples into the British Isles, the subsequent patterns of settlement, land-use, trade, through to social hierarchy and cultural identity within the kingdoms, this fully revised edition illuminates one of the most obscure and misunderstood periods in European history.

CONDITION: NEW. New hardcover with laminate/decorated covers (no dustjacket, as published). Routledge (1997 2nd edition) 260 pages. Unblemished except for very faint (virtually indiscernable) edge and corner shelfwear to the laminate covers. Pages are pristine; clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Condition is entirely consistent with new stock from a bookstore environment wherein new books might show minor signs of shelfwear, consequence of rotuine handling and simply being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. #1940.1a.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: "An Archaeology of the Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms has for nearly a decade been used by students seeking an introduction to the field. In this new, fully revised edition of Arnold's essential text all of the key recent finds and developments in the field of Anglo-Saxon studies have been incorporated. With an expanded text and an increased number of informative illustrations, C. J. Arnold confronts the key questions facing students who seek to understand how the foundations of medieval England were laid: How did kingdoms form out of the chaos of the Dark Ages? How was it that a deeply superstitious people came to embrace Christianity? What was the fate of Britain's native populations at the hand of invading peoples?" Firmly basing its arguments upon archaeological evidence, the book introduces students to the fascinating dichotomies of Anglo-Saxon society. It acts both as a reliable guide to historical fact and as an invaluable introduction to the key debates currently spurring research in the field.

REVIEW: A guide to the major monuments of the period of the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms - earthen and stone castles, moated sites, villages, towns, cathedrals, churches, tower houses, pottery kilns and mills.

REVIEW: Offering a view of the archaeological remains of the period and using the development of the kingdoms as a framework, this volume examines the material evidence and analyzes its significance to the understanding of the society that created it.

REVIEW: The second edition of a good introduction to the formation of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 6th and 7th centuries. The book looks at migrations, agriculture, crafts and exchange, burial and belief. The revised edition has a fuller text incorporating recent research.

REVIEW: Routledge is the world's leading academic publisher in the Humanities and Social Sciences. We publish thousands of books and journals each year, serving scholars, instructors, and professional communities worldwide. Our current publishing program encompasses groundbreaking textbooks and premier, peer-reviewed research in the Social Sciences, Humanities, and Built Environment. We have partnered with many of the most influential societies and academic bodies to publish their journals and book series. Readers can access tens of thousands of print and e-books from our extensive catalogue of titles.

REVIEW: C.J.Arnold is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth and is a widely regarded authority on Anglo-Saxon and medieval Welsh history. His numerous previous publications in these fields include Roman Britain to Saxon England (1984).

REVIEW: Christopher J. Arnold was formerly Senior Lecturer in Archaeology and Head of the Department of Continuing Education at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

List of Figures.

List of Tables.

Preface to the First Edition.

Preface to the Revised Second Edition.

Introduction.

1. History of Early Anglo-Saxon Archaeology.

2. Migration Theory.

3. Farm and Field.

4. Elusive Craftspeople.

-Brooches.

-Musical Insturments.

-Boats.

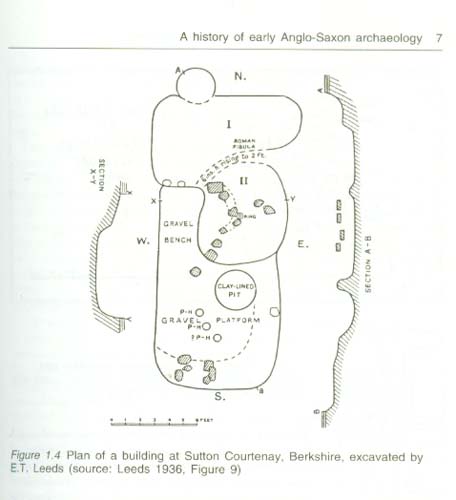

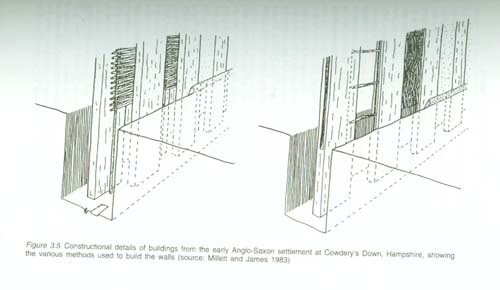

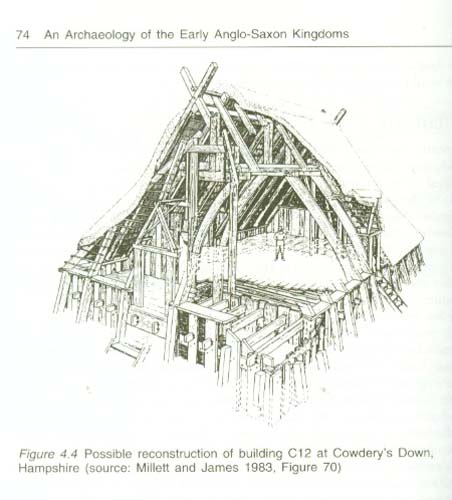

-Buildings.

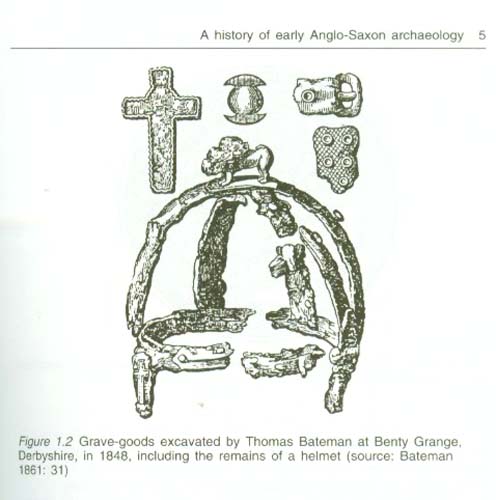

-Helmets.

-Iron Tools and Weapons.

-Casting.

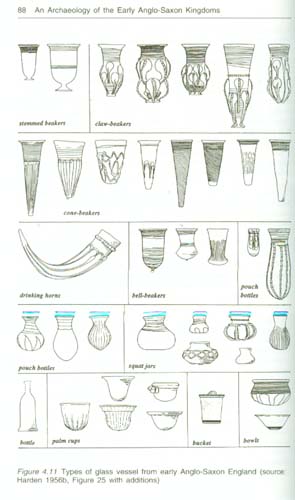

-Containers.

-Textiles and Dress.

-Function.

5. Exchange.

-Overseas Exchange.

-Internal Exchange.

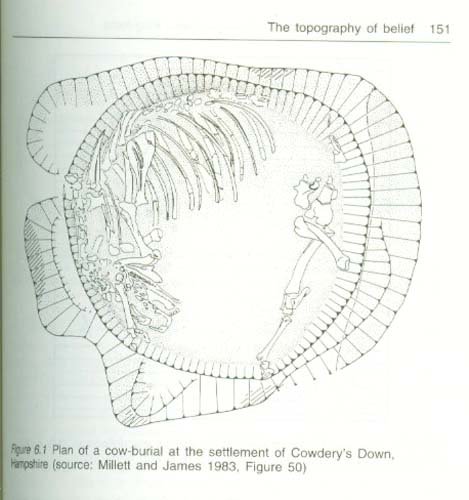

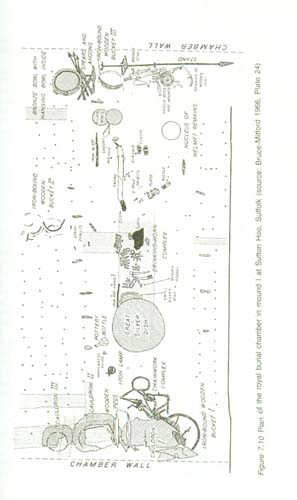

6. Topography of Belief.

7. Mighty Kinfolk.

-Identity and Status.

-The Individual.

-Descent Groups.

8. Kingdoms.

Bibliography.

Index.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: This is certainly a book which I would encourage students to read and discuss. It is full of ideas and should be welcomed as opening new and hopefully more fruitful debates in Anglo-Saxon archaeology. [Medieval Archaeology].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Archeologists are a unique breed. They are asked to lecture and to work out in the field during their summers. Their work forces them to be mathematical, detail-oriented, in order to record precisely where finds are made, on a three-dimensional model. And with that in place, they must determine what they have found and how it does or does not apply to the dig they are in the middle of. That last quality, of being imaginative, does not normally fall into the broad abilities of a typical archeologist. Nevertheless, they must have it to interpret the evidence in front of them with fresh eyes.

That most do not, and that the work is unusually taxing, has one foreseeable result; it is easier to find what someone else has decided and copy that down and most do. In many cases they are right, but that mindset also means that when artifacts do not match with the known facts they are often made to. Not so with Professor Arnold. This book is filled with innovative ideas that force the reader to look at the period from a different perspective, socially as well as culturally. I was deeply impressed with his handling of the materials. I am only disappointed that he didn't write more.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

REVIEW: The Saxons were a Germanic tribe that originally occupied the region which today is the North Sea coast of the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark. Their name is derived from the seax, a distinct knife popularly used by the tribe. One of the earliest historical records of this group that we know of comes from Roman writers dealing with the many troubles that affected the northern frontier of the Roman Empire during the second and third century A.D.

It is possible that under the "Saxons" label, these early Roman accounts also included other neighboring Germanic groups in the regions such as the Angles, the Frisians, and the Jutes; all these groups spoke closely related West Germanic languages that in time would evolve into Old English. Since the Saxons were illiterate, most of what we know about them comes from reports of a handful of writers (mostly bishops and monks) and also from archaeological research. The Saxons were among the "barbarian" nations that would engage against Rome during late antiquity, putting an end to the dying imperial order in the western realm of Rome, reshaping the map, and renaming the nations of Europe.

South of the territory where the Saxons lived on the continent were the Franks, a strong Germanic confederacy that had a solid presence occupying a territory between the Saxons and the Roman frontier. For this reason, expanding southwards was a problematic option for the Saxons, and a sea expansion was a more suitable alternative. Late in the third century A.D., Frankish raiders joined the Saxons in the southern part of the North Sea and the English Channel. They preyed on shipping lanes and also raided the coast of Britain and Gaul.

These attacks on Roman Britain during the late third century A.D. forced the authorities to build a network of forts with thick stone walls at coastal locations to repel these attacks, and the south coast of England became known as the Saxon Shore frontier. Generally located next to important harbours and river mouths, these forts not only served as strategic defenses against the raiders, but also as a means of securing the collection and distribution of state supplies.

Carausius, a Menapian commander of Roman legions under the future emperor Maximian, was given the task of eliminating the Frankish and Saxon pirates in 285 A.D. His mission was very successful and, by 286 A.D., he had broken the pirate's power at sea. He was accused, however, of being in league with the pirates and keeping their plunder for himself and so was condemned to death by order of Maximian (who was then emperor of Rome). Rather than submit to what he saw as unjust charges, he declared himself emperor of an independent Britain and reigned until 293 A.D., when he was killed in battle and rule from Rome was restored.

On the continent, meanwhile, the Saxon confederacy started to break up during the 4th century A.D. with an increasing number of Saxons (along with other Germanic groups such as the Angles) moving into Britain, while others remained in continental Europe. Around this time, we have official Roman records attesting to more Saxon raids in southeast Britain (Ammianus Marcellinus: 26, 4). Saxon soldiers had previously been employed by the Romans as legionaires in Britain, and the conflict between Carausius and Maximian may have encouraged those who had served to leave the area around the Elbe and relocate to an independent Britain under Carausius' reign. Even after Carausius' death, however, Saxon migration to Britain continued (often characterized by writers of that time as an invasion).

The southeast coast of Britain was not the only place affected by Saxon incursions. Not long after the death of Emperor Constantine (337 A.D.), the northern frontiers of Rome in continental Europe were also suffering the incursion of several “barbarian” groups, including the Saxons. The Roman historian Zosimus offers a summary of the challenges that Constantius, the Roman emperor who came after Constantine, had to face during the 350s A.D., in which the Saxons are mentioned as one of the many military threats hanging upon Rome.

But perceiving [Constantius] all the Roman territories to be infested by the incursions of the Barbarians, and that the Franks, the Alemanni, and the Saxons had not only possessed themselves of forty cities near the Rhine, but had likewise ruined and destroyed them, by carrying off an immense number of the inhabitants, and a proportionate quantity of spoils; [...] he scarcely thought himself capable of managing affairs at this critical period (Zosimus: Book 3, 1).

Early in the 5th century A.D., Roman control in Britain was waning, and most of Rome's military resources were allocated to the struggles in continental Europe. The Roman army withdrew from Britain completely in 410 A.D., and the occupied land was left in the hands of the Romanized Britons. The territory was divided into several small warring groups, both indigenous and invaders, fighting for political control. In the midst of this social and political strife, more Saxons migrated into Britain, expanding their territory and establishing a number of kingdoms which can be identified by the fact that most of their names contain the suffix "sex" (e.g. Sussex, Wessex).

Ancient sources provide different versions of how exactly the Saxons arrived in Britain and how they expanded. Three major works concerned with the Saxons in Britain have survived to the present day: the De Excidio Britanniae, written by Gildas; the Historia Ecclesiastica, by Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a narrative with multiple authors. According to Bede, the famous British monk who lived in the early Middle Ages, the Britons were suffering attacks from the Scots and the Picts, so they decided to hire some of the Saxons as mercenaries to fight their enemies.

Ancient sources provide different versions of how exactly the Saxons arrived in Britain and how they expanded. Three major works concerned with the Saxons in Britain have survived to the present day: the De Excidio Britanniae, written by Gildas; the Historia Ecclesiastica, by Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a narrative with multiple authors. According to Bede, the famous British monk who lived in the early Middle Ages, the Britons were suffering attacks from the Scots and the Picts, so they decided to hire some of the Saxons as mercenaries to fight their enemies.

After completing their task, the Saxons turned against the Britons. Gildas, a 6th century A.D. British monk, describes the Saxons as savages similar to dogs and lions, and he adds that "nothing more destructive, nothing more bitter has ever befallen the land". Gildas saw the destructive advance of the Saxons as a form of punishment inflicted by God for the sins of the British, whom he compares with the Israelites of the Bible: "The people of the Angles or Saxons were conveyed to Britain in three long-ships. When their voyage proved a success, news of them was carried back home. A stronger army set out which, joined to the earlier ones, first of all drove away the enemy they were seeking [the Picts and Scots]. Then they turned their arms on their allies [the Britons], and subjugated almost the whole island by fire or sword, from the eastern shore as far as the western one on the trumped-up excuse that the Britons had given them a less than adequate stipend for their military services (The Greater Chronicle, cited by Higham and Ryan)."

In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle we read about the Saxons moving into Britain as successive "arrivals" by sea, under different leaders, and establishing small kingdoms in different areas of Britain: Hengest in 449 A.D., leading a force of three ships, ruling over Kent; Ælle in 477 A.D., leading a force of three ships, ruling over Sussex; and Cerdic, the founding figure of the West Saxon dynasty, leading a squadron of five ships and arriving in Britain in 495 A.D.

Cerdic is the most famous of the Saxon kings, reigning from 519-534 A.D. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's entry for 519 A.D. states: "In this year Cerdic and Cynric obtained the kingdom of the West Saxons, and the same year they fought against the Britons at a place now called Cerdices-ford. And from that day on the princes of the West Saxons have reigned." He is said to have fought "the renowned King Arthur" in 520 A.D., but that date may actually be off by one year, and the battle with Arthur took place in 519 A.D.

Historian Robert J. Sewell notes that, "Cerdic met great resistance from the last of the Romano-Britons under a shadowy leader who lays as good a claim as any to having been the 'real' King Arthur". Cerdic either won the battle or declared a truce and was given the land by the Briton king identified with Arthur but, either way, he founded the kingdom of the West Saxons, Wessex, in Britain. While the date of 519 A.D. is cited in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles for the beginning of his reign, a date as late as 532 A.D. is suggested by other sources.

In 530 A.D., Cerdic conquered the Isle of Wight, employing his already established army and navy; he died two years later in 534 A.D. The earlier date, then, makes more sense than the later one in the narrative of Cerdic's life. The chaotic nature of the time, and conflicting accounts from different sources, quite often create very different narratives which have been followed, or combined, by later writers.

In the past, these traditional accounts were taken at face value, with writers rejecting one narrative in favor of another or combining two or more. Victorian writers accepted the "arrival" stories reported in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as historical truth, which they then modified to fit their own narrative ends. Because these older narratives often contradicted each other, later writers tried to blend them into seamless stories which provided them with a linear history of their past. This is how one may today read two very different accounts of the history of Britain which both claim to be the truth and both of which can point to older narratives for support of that claim. One must keep in mind the different versions and interpretations of the so-called "Saxon Invasions" when reading these various sources.

An example of this problem is the claim that the Saxons were hired by the Romans to fight in Britain. Since Rome at the time lacked troops in Britain, the account of the Saxons employed as mercenaries seems plausible: the Romanised Britons decided to hire barbarians as mercenaries for security reasons, which was a common Roman practice. Rather than reflecting mass migration, archaeological evidence of Saxon presence before 450 A.D. is very weak, which is consistent with the military conquest stated in the ancient accounts: as field army of the Britons, the number of Saxons could not have been initially more than a few thousand.

The Gallic Chronicle of 452 A.D., talks about the Saxons ruling over a large part of Southern Britain, also consistent with the rise of the number of Saxon archaeological material after 450 A.D. The earliest Anglo-Saxon burial in Britain has been dated by archaeologists to no later than 425-450 A.D. The burial practices of the Saxons (and the Germanic tribes in general) were markedly different from indigenous burials in Britain. North German cremation ritual was introduced into eastern England, but Germanic people gradually abandoned cremation in favor of inhumation, burying their dead with grave goods, a custom that was in place until about 700 A.D.; by the late 6th century A.D., furnished inhumation dominates the Saxon disposal of the dead.

Saxon burials did not develop from past indigenous practices; instead, they are connected to burials found on the other side of the North Sea. Late Roman burials in Britain had been largely unfurnished inhumations but, by the late 4th century A.D., we see the emergence of inhumations accompanied by weapons and belt fittings, often interpreted as the burials of Germanic mercenary soldiers, resembling other burials found in northern Gaul and other areas occupied by Germanic tribes. These burials relate to the development of Angle and Saxon burial rites detected between the 5th and 7th centuries A.D.: inhumation burials where men were usually buried with weapons, while women were buried with combs, brooches, and necklaces.

It is clear both from historical sources and archaeological data that by the end of the 5th century A.D., southeast Britain was under the control of various Saxon groups. The spread of Saxon burial practices over places where only indigenous burials were previously recorded reflects the spread of the Saxons displacing indigenous Roman and Celtic groups. During the 5th century A.D., there are recorded hostilities between the Franks and the Saxons in continental Europe. Under the leadership of Childeric, the Franks supported Roman forces and helped them defeat a number of enemies including an army of Saxons at Angers in 469 A.D.

It is clear both from historical sources and archaeological data that by the end of the 5th century A.D., southeast Britain was under the control of various Saxon groups. The spread of Saxon burial practices over places where only indigenous burials were previously recorded reflects the spread of the Saxons displacing indigenous Roman and Celtic groups. During the 5th century A.D., there are recorded hostilities between the Franks and the Saxons in continental Europe. Under the leadership of Childeric, the Franks supported Roman forces and helped them defeat a number of enemies including an army of Saxons at Angers in 469 A.D.

The Franks began a gradual process of absorption of the continental Saxons and, while this process was still ongoing during the 8th century A.D., those Saxons who migrated into Britain managed to build a solid presence. After several generations of conquest, alliances, and unstable successions, they established their rule over most of the indigenous groups. After the 9th century A.D. Viking invasions, the kings of Wessex (Alfred and his descendants) created the first strong West Saxon kingdom (south of the Thames) which, during the 10th century A.D., managed to conquer the rest of England creating the late Anglo-Saxon kingdom.

Britain was the only place in Europe that saw the formation of new states that had little in common with Roman principles. All nascent states in continental Europe that emerged after the decline of the Roman order were created on Roman foundations, sometimes with a clear Roman involvement or even retaining key aspects of Roman life. This was not the case with the Saxons who entered Britain and who were less familiar with the Roman ways. The movement of the Saxons and the Angles into Britain was a critical stage in the overall development of the English language.

If these Germanic tribes did not move into Britain, the English language as we know it would not exist today, and the dialects of the Angles and Saxons would have been gradually dissolved in the continental Germanic languages, possibly blended into the Low German and Dutch dialects. As they expanded across Britain, these Germanic groups displaced the local Celtic speaking communities. Old English, the language born of the Angles and the Saxons who entered Britain, gradually displaced the Latin and Brittonic languages across lowland Britain, and from there it eventually gained ascendency over most of the British Isles. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

REVIEW: The Anglo-Saxons were a people who inhabited Great Britain from the 5th century. They comprise people from Germanic tribes who migrated to the island from continental Europe, their descendants, and indigenous British groups who adopted some aspects of Anglo-Saxon culture and language. Historically, the Anglo-Saxon period denotes the period in Britain between about 450 and 1066, after their initial settlement and up until the Norman conquest.

The early Anglo-Saxon period includes the creation of an English nation, with many of the aspects that survive today, including regional government of shires and hundreds. During this period, Christianity was established and there was a flowering of literature and language. Charters and law were also established. The term Anglo-Saxon is popularly used for the language that was spoken and written by the Anglo-Saxons in England and eastern Scotland between at least the mid-5th century and the mid-12th century. In scholarly use, it is more commonly called Old English.

The history of the Anglo-Saxons is the history of a cultural identity. It developed from divergent groups in association with the people's adoption of Christianity, and was integral to the establishment of various kingdoms. Threatened by extended Danish invasions and military occupation of eastern England, this identity was re-established; it dominated until after the Norman Conquest. The visible Anglo-Saxon culture can be seen in the material culture of buildings, dress styles, illuminated texts and grave goods.

Behind the symbolic nature of these cultural emblems, there are strong elements of tribal and lordship ties. The elite declared themselves as kings who developed burhs, and identified their roles and peoples in Biblical terms. Above all, as Helena Hamerow has observed, "local and extended kin groups remained...the essential unit of production throughout the Anglo-Saxon period." The effects persist in the 21st century as, according to a study published in March 2015, the genetic make up of British populations today shows divisions of the tribal political units of the early Anglo-Saxon period.

The early Anglo-Saxon period covers the history of medieval Britain that starts from the end of Roman rule. It is a period widely known in European history as the Migration Period, also the Völkerwanderung ("migration of peoples" in German). This was a period of intensified human migration in Europe from about 400 to 800. The migrants were Germanic tribes such as the Goths, Vandals, Angles, Saxons, Lombards, Suebi, Frisii and Franks; they were later pushed westwards by the Huns, Avars, Slavs, Bulgars and Alans. By the year 400, southern Britain – that is Britain below Hadrian's Wall – was a peripheral part of the western Roman Empire, occasionally lost to rebellion or invasion, but until then always eventually recovered. Around 410, Britain slipped beyond direct imperial control into a phase which has generally been termed "sub-Roman".

The migrations according to Bede, who wrote some 300 years after the event; there is archeological evidence that the settlers in England came from many of these continental locations. The traditional narrative of this period is one of decline and fall, invasion and migration; however, the archAeologist Heinrich Härke stated in 2011: "It is now widely accepted that the Anglo-Saxons were not just transplanted Germanic invaders and settlers from the Continent, but the outcome of insular interactions and changes.

Writing in about 540 Gildas mentions that, sometime in the 5th century, a council of leaders in Britain agreed that some land in the east of southern Britain would be given to the Saxons on the basis of a treaty, a foedus, by which the Saxons would defend the Britons against attacks from the Picts and Scoti in exchange for food supplies. The most contemporaneous textual evidence is the Chronica Gallica of 452 which records for the year 441: "The British provinces, which to this time had suffered various defeats and misfortunes, are reduced to Saxon rule."

This is an earlier date than that of 451 for the "coming of the Saxons" used by Bede in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, written around 731. It has been argued that Bede misinterpreted his (scanty) sources, and that the chronological references in the Historia Britonnum yield a plausible date of around 428. Gildas recounts how a war broke out between the Saxons and the local population – Higham calls it the "War of the Saxon Federates" – which ended shortly after the siege at 'Mons Badonicus'. The Saxons go back to "their eastern home".

Gildas calls the peace a "grievous divorce with the barbarians". The price of peace, Nick Higham argues, is a better treaty for the Saxons, giving them the ability to receive tribute from people across the lowlands of Britain. The archAeological evidence agrees with this earlier timescale. In particular, the work of Catherine Hills and Sam Lucy on the evidence of Spong Hill has moved the chronology for the settlement earlier than 450, with a significant number of items now in phases before Bede's date

This vision of the Anglo-Saxons exercising extensive political and military power at an early date remains contested. The most developed vision of a continuation in sub-Roman Britain, with control over its own political and military destiny for well over a century, is that of Kenneth Dark, who suggests that the sub-Roman elite survived in culture, politics and military power up to about 570.

This vision of the Anglo-Saxons exercising extensive political and military power at an early date remains contested. The most developed vision of a continuation in sub-Roman Britain, with control over its own political and military destiny for well over a century, is that of Kenneth Dark, who suggests that the sub-Roman elite survived in culture, politics and military power up to about 570.

However, Nick Higham seems to agree with Bede, who identified three phases of settlement: an exploration phase, when mercenaries came to protect the resident population; a migration phase, which was substantial as implied by the statement that Anglus was deserted; and an establishment phase, in which Anglo-Saxons started to control areas, implied in Bede's statement about the origins of the tribes. Scholars have not reached consensus on the number of migrants who entered Britain in this period. Heinrich Härke suggests that the figure is around 100,000, based on the molecular evidence. But, archAeologists such as Christine Hills and Richard Hodges suggest the number is nearer 20,000. By around 500 the Anglo-Saxon migrants were established in southern and eastern Britain.

What happened to the indigenous Brittonic people is also subject to question. Heinrich Härke and Richard Coates point out that they are invisible archAeologically and linguistically. But based on a fairly high Anglo-Saxon figure (200,000) and a low Brythonic one (800,000), Brythonic people are likely to have outnumbered Anglo-Saxons by at least four to one. The interpretation of such figures is that while "culturally, the later Anglo-Saxons and English did emerge as remarkably un-British...their genetic, biological make-up is none the less likely to have been substantially, indeed predominantly, British".

The development of Anglo-Saxon culture is described by two processes. One is similar to culture changes observed in Russia, North Africa and parts of the Islamic world, where a powerful minority culture becomes, over a rather short period, adopted by a settled majority. The second process is explained through incentives. Nick Higham summarized in this way: "As Bede later implied, language was a key indicator of ethnicity in early England. In circumstances where freedom at law, acceptance with the kindred, access to patronage, and the use and possession of weapons were all exclusive to those who could claim Germanic descent, then speaking Old English without Latin or Brittonic inflection had considerable value.

By the middle of the 6th century, some Brythonic people in the lowlands of Britain had moved across the sea to form Brittany, and some had moved west, but the majority were abandoning their past language and culture and adopting the new culture of the Anglo-Saxons. As they adopted this language and culture, the barriers began to dissolve between peoples, who had earlier lived parallel lives. The archAeological evidence shows considerable continuity in the system of landscape and local governance, which was inherited from the indigenous community. There is evidence for a fusion of culture in this early period.

Brythonic names appear in the lists of Anglo-Saxon elite. The Wessex royal line was traditionally founded by a man named Cerdic, an undoubtedly Celtic name ultimately derived from Caratacus. This may indicate that Cerdic was a native Briton, and that his dynasty became anglicised over time. A number of Cerdic's alleged descendants also possessed Celtic names, including the 'Bretwalda' Ceawlin. The last man in this dynasty to have a Brythonic name was King CAedwalla, who died as late as 689.

In the last half of the 6th century, four structures contributed to the development of society; they were the position and freedoms of the ceorl, the smaller tribal areas coalescing into larger kingdoms, the elite developing from warriors to kings, and Irish monasticism developing under Finnian (who had consulted Gildas) and his pupil Columba. The Anglo-Saxon farms of this period are often falsely supposed to be "peasant farms". However, a ceorl, who was the lowest ranking freeman in early Anglo-Saxon society, was not a peasant but an arms-owning male with the support of a kindred, access to law and the wergild; situated at the apex of an extended household working at least one hide of land.

The farmer had freedom and rights over lands, with provision of a rent or duty to an overlord who provided only slight lordly input. Most of this land was common outfield arable land (of an outfield-infield system) that provided individuals with the means to build a basis of kinship and group cultural ties. The Tribal Hidage lists thirty-five peoples, or tribes, with assessments in hides, which may have originally been defined as the area of land sufficient to maintain one family. The assessments in the Hidage reflect the relative size of the provinces.

Although varying in size, all thirty-five peoples of the Tribal Hidage were of the same status, in that they were areas which were ruled by their own elite family (or royal houses), and so were assessed independently for payment of tribute. By the end of the sixth century, larger kingdoms had become established on the south or east coasts. They include the provinces of the Jutes of Hampshire and Wight, the South Saxons, Kent, the East Saxons, East Angles, Lindsey and (north of the Humber) Deira and Bernicia. Several of these kingdoms may have had as their initial focus a territory based on a former Roman civitas.

By the end of the sixth century, the leaders of these communities were styling themselves kings, though it should not be assumed that all of them were Germanic in origin. The Bretwalda concept is taken as evidence of a number of early Anglo-Saxon elite families. What Bede seems to imply in his Bretwalda is the ability of leaders to extract tribute, overawe and/or protect the small regions, which may well have been relatively short-lived in any one instance. Ostensibly "Anglo-Saxon" dynasties variously replaced one another in this role in a discontinuous but influential and potent roll call of warrior elites.

Importantly, whatever their origin or whenever they flourished, these dynasties established their claim to lordship through their links to extended kin ties. As Helen Peake jokingly points out, "they all just happened to be related back to Woden". The process from warrior to cyning – Old English for king – is described in Beowulf (as translated by Seamus Heaney): "There was Shield Sheafson, scourge of many tribes, a wrecker of mead-benches, rampaging among foes. This terror of the hall-troops had come far. A foundling to start with, he would flourish later on. As his powers waxed and his worth was proved. In the end each clan on the outlying coasts. Beyond the whale-road had to yield to him. And begin to pay tribute. That was one good king.

In 565, Columba, a monk from Ireland who studied at the monastic school of Moville under St. Finnian, reached Iona as a self-imposed exile. The influence of the monastery of Iona would grow into what Peter Brown has described as an "unusually extensive spiritual empire," which "stretched from western Scotland deep to the southwest into the heart of Ireland and, to the southeast, it reached down throughout northern Britain, through the influence of its sister monastery Lindisfarne." In June 597 Columba died. At this time, Augustine landed on the Isle of Thanet and proceeded to King Aethelberht's main town of Canterbury.

He had been the prior of a monastery in Rome when Pope Gregory the Great chose him in 595 to lead the Gregorian mission to Britain to Christianise the Kingdom of Kent from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism. Kent was probably chosen because Aethelberht had married a Christian princess, Bertha, daughter of Charibert I the King of Paris, who was expected to exert some influence over her husband. Aethelberht was converted to Christianity, churches were established, and wider-scale conversion to Christianity began in the kingdom. Aethelberht's law for Kent, the earliest written code in any Germanic language, instituted a complex system of fines.

He had been the prior of a monastery in Rome when Pope Gregory the Great chose him in 595 to lead the Gregorian mission to Britain to Christianise the Kingdom of Kent from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism. Kent was probably chosen because Aethelberht had married a Christian princess, Bertha, daughter of Charibert I the King of Paris, who was expected to exert some influence over her husband. Aethelberht was converted to Christianity, churches were established, and wider-scale conversion to Christianity began in the kingdom. Aethelberht's law for Kent, the earliest written code in any Germanic language, instituted a complex system of fines.

Kent was rich, with strong trade ties to the continent, and Aethelberht may have instituted royal control over trade. For the first time following the Anglo-Saxon invasion, coins began circulating in Kent during his reign. In 635 Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona chose the Isle of Lindisfarne to establish a monastery and close to King Oswald's main fortress of Bamburgh. He had been at the monastery in Iona when Oswald asked to be sent a mission to Christianise the Kingdom of Northumbria from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism.

Oswald had probably chosen Iona because after his father had been killed he had fled into south-west Scotland and had encountered Christianity, and had returned determined to make Northumbria Christian. Aidan achieved great success in spreading the Christian faith, and since Aidan could not speak English and Oswald had learned Irish during his exile, Oswald acted as Aidan's interpreter when the latter was preaching. Later, Northumberland's patron saint, Saint Cuthbert, was an abbot of the monastery, and then Bishop of Lindisfarne.

An anonymous life of Cuthbert written at Lindisfarne is the oldest extant piece of English historical writing, and in his memory a gospel (known as the St Cuthbert Gospel) was placed in his coffin. The decorated leather bookbinding is the oldest intact European binding. In 664, the Synod of Whitby was convened and established Roman practice (in style of tonsure and dates of Easter) as the norm in Northumbria, and thus "brought the Northumbrian church into the mainstream of Roman culture." The episcopal seat of Northumbria was transferred from Lindisfarne to York. Wilfrid, chief advocate for the Roman position, later became Bishop of Northumbria, while Colmán and the Ionan supporters, who did not change their practices, withdrew to Iona.

By 660 the political map of Lowland Britain had developed with smaller territories coalescing into kingdoms, from this time larger kingdoms started dominating the smaller kingdoms. The development of kingdoms, with a particular king being recognised as an overlord, developed out of an early loose structure that, Higham believes, is linked back to the original feodus. The traditional name for this period is the Heptarchy, which has not been used by scholars since the early 20th century as it gives the impression of a single political structure and does not afford the "opportunity to treat the history of any one kingdom as a whole".

Simon Keynes suggests that the 8th and 9th century was period of economic and social flourishing which created stability both below the Thames and above the Humber. Many areas flourished and their influence was felt across the continent, however in between the Humber and Thames, one political entity grew in influence and power and to the East these developments in Britain attracted attention.

Middle-lowland Britain was known as the place of the Mierce, the border or frontier folk, in Latin Mercia. Mercia was a diverse area of tribal groups, as shown by the Tribal Hidage; the peoples were a mixture of Brythonic speaking peoples and "Anglo-Saxon" pioneers and their early leaders had Brythonic names, such as Penda. Although Penda does not appear in Bede's list of great overlords it would appear from what Bede says elsewhere that he was dominant over the southern kingdoms. At the time of the battle of the river WinwAed, thirty duces regii (royal generals) fought on his behalf. Although there are many gaps in the evidence, it is clear that the seventh-century Mercian kings were formidable rulers who were able to exercise a wide-ranging overlordship from their Midland base.

Mercian military success was the basis of their power; it succeeded not only 106 kings and kingdoms by winning set-piece battles, but by ruthlessly ravaging any area foolish enough to withhold tribute. There are a number of casual references scattered throughout the Bede's history to this aspect of Mercian military policy. Penda is found ravaging Northumbria as far north as Bamburgh and only a miraculous intervention from Aidan prevents the complete destruction of the settlement. In 676 Aethelred conducted a similar ravaging in Kent and caused such damage in the Rochester diocese that two successive bishops gave up their position because of lack of funds.

In these accounts there is a rare glimpse of the realities of early Anglo-Saxon overlordship and how a widespread overlordship could be established in a relatively short period. By the middle of the 8th century, other kingdoms of southern Britain were also affected by Mercian expansionism. The East Saxons seem to have lost control of London, Middlesex and Hertfordshire to Aethelbald, although the East Saxon homelands do not seem to have been affected, and the East Saxon dynasty continued into the ninth century.

The Mercian influence and reputation reached its peak when, in the late 8th century, the most powerful European ruler of the age, the Frankish king Charlemagne, recognised the Mercian King Offa's power and accordingly treated him with respect, even if this could have been just flattery. MichAel Drout calls the period between about 660–793 the "Golden Age", when learning flourishes with a renaissance in classical knowledge. The growth and popularity of monasticism was not an entirely internal development, with influence from the continent shaping Anglo-Saxon monastic life.

In 669 Theodore, a Greek-speaking monk originally from Tarsus in Asia Minor, arrived in Britain to become the eighth Archbishop of Canterbury. He was joined the following year by his colleague Hadrian, a Latin-speaking African by origin and former abbot of a monastery in Campania (near Naples). One of their first tasks at Canterbury was the establishment of a school; and according to Bede (writing some sixty years later), they soon "attracted a crowd of students into whose minds they daily poured the streams of wholesome learning".

As evidence of their teaching, Bede reports that some of their students, who survived to his own day were as fluent in Greek and Latin as in their native language. Bede does not mention Aldhelm in this connection; but we know from a letter addressed by Aldhelm to Hadrian that he too must be numbered among their students. Aldhelm wrote in elaborate and grandiloquent and very difficult Latin, which became the dominant style for centuries. MichAel Drout states "Aldhelm wrote Latin hexameters better than anyone before in England (and possibly better than anyone since, or at least up until Milton).

As evidence of their teaching, Bede reports that some of their students, who survived to his own day were as fluent in Greek and Latin as in their native language. Bede does not mention Aldhelm in this connection; but we know from a letter addressed by Aldhelm to Hadrian that he too must be numbered among their students. Aldhelm wrote in elaborate and grandiloquent and very difficult Latin, which became the dominant style for centuries. MichAel Drout states "Aldhelm wrote Latin hexameters better than anyone before in England (and possibly better than anyone since, or at least up until Milton).

His work showed that scholars in England, at the very edge of Europe, could be as learned and sophisticated as any writers in Europe." During this period, the wealth and power of the monasteries increased as elite families, possibly out of power, turned to monastic life. Anglo-Saxon monasticism developed the unusual institution of the "double monastery", a house of monks and a house of nuns, living next to each other, sharing a church but never mixing, and living separate lives of celibacy. These double monasteries were presided over by abbesses, some of the most powerful and influential women in Europe.

Double monasteries which were built on strategic sites near rivers and coasts, accumulated immense wealth and power over multiple generations (their inheritances were not divided) and became centers of art and learning. While Aldhelm was doing his work in Malmesbury, far from him, up in the North of England, Bede was writing a large quantity of books, gaining a reputation in Europe and showing that the English could write history and theology, and do astronomical computation (for the dates of Easter, among other things).

The 9th century saw the rise of Wessex, from the foundations laid by King Egbert in the first quarter of the century to the achievements of King Alfred the Great in its closing decades. The outlines of the story are told in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, though the annals represent a West Saxon point of view. On the day of Egbert's succession to the kingdom of Wessex, in 802, a Mercian ealdorman from the province of the Hwicce had crossed the border at Kempsford, with the intention of mounting a raid into northern Wiltshire; the Mercian force was met by the local ealdorman, "and the people of Wiltshire had the victory".

In 829 Egbert went on, the chronicler reports, to conquer "the kingdom of the Mercians and everything south of the Humber". It was at this point that the chronicler chose to attach Egbert's name to Bede's list of seven overlords, adding that "he was the eighth king who was Bretwalda". Simon Keynes suggests Egbert's foundation of a 'bipartite' kingdom is crucial as it stretched across southern England, and it created a working alliance between the West Saxon dynasty and the rulers of the Mercians.

In 860 the eastern and western parts of the southern kingdom were united by agreement between the surviving sons of King Aethelwulf, though the union was not maintained without some opposition from within the dynasty; and in the late 870s King Alfred gained the submission of the Mercians under their ruler Aethelred, who in other circumstances might have been styled a king, but who under the Alfredian regime was regarded as the 'ealdorman' of his people.

The wealth of the monasteries and the success of Anglo-Saxon society attracted the attention of people from continental Europe, mostly Danes and Norwegians. Due to the plundering raids that followed, the raiders attracted the name Viking – from the Old Norse víkingr meaning an expedition – which soon became used for the raiding activity or piracy reported in western Europe. In 793, Lindisfarne was raided and while this was not the first raid of its type it was the most prominent. A year later Jarrow, the monastery where Bede wrote, was attacked; in 795 Iona; and in 804 the nunnery at Lyminge Kent was granted refuge inside the walls of Canterbury. Sometime around 800, a Reeve from Portland in Wessex was killed when he mistook some raiders for ordinary traders.

Viking raids continued until in 850, then the Chronicle says: "The heathen for the first time remained over the winter". The fleet does not appear to have stayed long in England, but it started a trend which others subsequently followed. In particular, the army which arrived in 865 remained over many winters, and part of it later settled what became known as the Danelaw. This was the "Great Army", a term used by the Chronicle in England and by Adrevald of Fleury on the Continent. The invaders were able not only to exploit the feuds between and within the various kingdoms, but to appoint puppet kings, Ceolwulf in Mercia in 873, 'a foolish king's thane' (ASC), and perhaps others in Northumbria in 867 and East Anglia in 870.

The third phase was an era of settlement; however, the 'Great Army' went wherever it could find the richest pickings, crossing the Channel when faced with resolute opposition, as in England in 878, or with famine, as on the Continent in 892. By this stage the Vikings were assuming ever increasing importance as catalysts of social and political change. They constituted the common enemy, making the English the more conscious of a national identity which overrode deeper distinctions; they could be perceived as an instrument of divine punishment for the people's sins, raising awareness of a collective Christian identity; and by 'conquering' the kingdoms of the East Angles, the Northumbrians and the Mercians they created a vacuum in the leadership of the English people.

Danish settlement continued in Mercia in 877 and East Anglia in 879—80 and 896. The rest of the army meanwhile continued to harry and plunder on both sides of the Channel, with new recruits evidently arriving to swell its ranks, for it clearly continued to be a formidable fighting force. At first, Alfred responded by the offer of repeated tribute payments. However, after a decisive victory at Edington in 878, Alfred offered vigorous opposition.

He established a chain of fortresses across the south of England, reorganized the army, "so that always half its men were at home, and half out on service, except for those men who were to garrison the burhs", and in 896 ordered a new type of craft to be built which could oppose the Viking longships in shallow coastal waters. When the Vikings returned from the Continent in 892, they found they could no longer roam the country at will, for wherever they went they were opposed by a local army. After four years, the Scandinavians therefore split up, some to settle in Northumbria and East Anglia, the remainder to try their luck again on the Continent.

More important to Alfred than his military and political victories were his religion, his love of learning, and his spread of writing throughout England. Simon Keynes suggests Alfred's work laid the foundations for what really makes England unique in all of medieval Europe from around 800 until 1066. What is also unique is that we can discover some of this in Alfred's own words. Thinking about how learning and culture had fallen since the last century, he wrote:

More important to Alfred than his military and political victories were his religion, his love of learning, and his spread of writing throughout England. Simon Keynes suggests Alfred's work laid the foundations for what really makes England unique in all of medieval Europe from around 800 until 1066. What is also unique is that we can discover some of this in Alfred's own words. Thinking about how learning and culture had fallen since the last century, he wrote:

"...So completely had wisdom fallen off in England that there were very few on this side of the Humber who could understand their rituals in English, or indeed could translate a letter from Latin into English; and I believe that there were not many beyond the Humber. There were so few of them that I indeed cannot think of a single one south of the Thames when I became king."

Alfred knew that literature and learning, both in English and in Latin, were very important, but the state of learning was not good when Alfred came to the throne. Alfred saw kingship as a priestly office, a shepherd for his people. One book that was particularly valuable to him was Gregory the Great's Cura Pastoralis (Pastoral Care). This is a priest's guide on how to care for people. Alfred took this book as his own guide on how to be a good king to his people; hence, a good king to Alfred increases literacy. Alfred translated this book himself and explains in the preface:

"...When I had learned it I translated it into English, just as I had understood it, and as I could most meaningfully render it. And I will send one to each bishopric in my kingdom, and in each will be an Aestel worth fifty mancuses. And I command in God's name that no man may take the Aestel from the book nor the book from the church. It is unknown how long there may be such learned bishops as, thanks to God, are nearly everywhere."

What is presumed to be one of these "Aestel" (the word only appears in this one text) is the gold, rock crystal and enamel Alfred Jewel, discovered in 1693, which is assumed to have been fitted with a small rod and used as a pointer when reading. Alfred provided functional patronage, linked to a social programme of vernacular literacy in England, which was unprecedented.

"Therefore it seems better to me, if it seems so to you, that we also translate certain books ...and bring it about ...if we have the peace, that all the youth of free men who now are in England, those who have the means that they may apply themselves to it, be set to learning, while they may not be set to any other use, until the time when they can well read English writings."

This set in train a growth in charters, law, theology and learning. Alfred thus laid the foundation for the great accomplishments of the tenth century and did much to make the vernacular was more important than Latin in Anglo-Saxon culture. "I desired to live worthily as long as I lived, and to leave after my life, to the men who should come after me, the memory of me in good works."

A framework for the momentous events of the 10th and 11th centuries is provided by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. However charters, law-codes and coins supply detailed information on various aspects of royal government, and the surviving works of Anglo-Latin and vernacular literature, as well as the numerous manuscripts written in the 10th century, testify in their different ways to the vitality of ecclesiastical culture. Yet as Simon Keynes suggests "it does not follow that the 10th century is better understood than more sparsely documented periods".

During the course of the 10th century, the West Saxon kings extended their power first over Mercia, then into the southern Danelaw, and finally over Northumbria, thereby imposing a semblance of political unity on peoples, who nonetheless would remain conscious of their respective customs and their separate pasts. The prestige, and indeed the pretensions, of the monarchy increased, the institutions of government strengthened, and kings and their agents sought in various ways to establish social order.

This process started with Edward the Elder – who with his sister, AethelflAed, Lady of the Mercians, initially, charters reveal, encouraged people to purchase estates from the Danes, thereby to reassert some degree of English influence in territory which had fallen under Danish control. David Dumville suggests that Edward may have extended this policy by rewarding his supporters with grants of land in the territories newly conquered from the Danes, and that any charters issued in respect of such grants have not survived. When AthelflAed died, Mercia was absorbed by Wessex. From that point on there was no contest for the throne, so the house of Wessex became the ruling house of England.

Edward the Elder was succeeded by his son Aethelstan, who Simon Keynes calls the "towering figure in the landscape of the tenth century". His victory over a coalition of his enemies – Constantine, King of the Scots, Owain ap Dyfnwal, King of the Cumbrians, and Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin – at the battle of Brunanburh, celebrated by a famous poem in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, opened the way for him to be hailed as the first king of England. Aethelstan's legislation shows how the king drove his officials to do their respective duties. He was uncompromising in his insistence on respect for the law. However this legislation also reveals the persistent difficulties which confronted the king and his councillors in bringing a troublesome people under some form of control.

His claim to be "king of the English" was by no means widely recogniZed. The situation was complex: the Hiberno-Norse rulers of Dublin still coveted their interests in the Danish kingdom of York; terms had to be made with the Scots, who had the capacity not merely to interfere in Northumbrian affairs, but also to block a line of communication between Dublin and York; and the inhabitants of northern Northumbria were considered a law unto themselves. It was only after twenty years of crucial developments following Aethelstan's death in 939 that a unified kingdom of England began to assume its familiar shape.

However, the major political problem for Edmund and Eadred, who succeeded Aethelstan, remained the difficulty of subjugating the north. In 959 Edgar is said to have "succeeded to the kingdom both in Wessex and in Mercia and in Northumbria, and he was then 16 years old" (ASC, version 'B', 'C'), and is called "the Peacemaker". By the early 970s, after a decade of Edgar's 'peace', it may have seemed that the kingdom of England was indeed made whole. In his formal address to the gathering at Winchester the king urged his bishops, abbots and abbesses "to be of one mind as regards monastic usage . . . lest differing ways of observing the customs of one Rule and one country should bring their holy conversation into disrepute".

However, the major political problem for Edmund and Eadred, who succeeded Aethelstan, remained the difficulty of subjugating the north. In 959 Edgar is said to have "succeeded to the kingdom both in Wessex and in Mercia and in Northumbria, and he was then 16 years old" (ASC, version 'B', 'C'), and is called "the Peacemaker". By the early 970s, after a decade of Edgar's 'peace', it may have seemed that the kingdom of England was indeed made whole. In his formal address to the gathering at Winchester the king urged his bishops, abbots and abbesses "to be of one mind as regards monastic usage . . . lest differing ways of observing the customs of one Rule and one country should bring their holy conversation into disrepute".

Athelstan's court had been an intellectual incubator. In that court were two young men named Dunstan and Aethelwold who were made priests, supposedly at the insistence of Athelstan, right at the end of his reign in 939. Between 970 and 973 a council was held, under the Aegis of Edgar, where a set of rules were devised that would be applicable throughout England. This put all the monks and nuns in England under one set of detailed customs for the first time. In 973, Edgar received a special second, 'imperial coronation' at Bath, and from this point England was ruled by Edgar under the strong influence of Dunstan, Athelwold, and Oswald, the Bishop of Worcester.

The reign of King Aethelred the Unready witnessed the resumption of Viking raids on England, putting the country and its leadership under strains as severe as they were long sustained. Raids began on a relatively small scale in the 980s, but became far more serious in the 990s, and brought the people to their knees in 1009–12, when a large part of the country was devastated by the army of Thorkell the Tall. It remained for Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, to conquer the kingdom of England in 1013–14, and (after Aethelred's restoration) for his son Cnut to achieve the same in 1015–16. The tale of these years incorporated in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle must be read in its own right, and set beside other material which reflects in one way or another on the conduct of government and warfare during Aethelred's reign.

It is this evidence which is the basis for Simon Keynes's view that the king lacked the strength, judgement and resolve to give adequate leadership to his people in a time of grave national crisis; who soon found out that he could rely on little but the treachery of his military commanders; and who, throughout his reign, tasted nothing but the ignominy of defeat. The raids exposed tensions and weaknesses which went deep into the fabric of the late Anglo-Saxon state and it is apparent that events proceeded against a background more complex than the chronicler probably knew. It seems, for example, that the death of Bishop Aethelwold in 984 had precipitated further reaction against certain ecclesiastical interests; that by 993 the king had come to regret the error of his ways, leading to a period when the internal affairs of the kingdom appear to have prospered.

The increasingly difficult times brought on by the Viking attacks are reflected in both Aelfric's and Wulfstan's works, but most notably in Wulfstan's fierce rhetoric in the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, dated to 1014. Malcolm Godden suggests that ordinary people saw the return of the Vikings, as the imminent "expectation of the apocalypse", and this was given voice in Aelfric and Wulfstan writings, which is similar to that of Gildas and Bede. Raids were signs of God punishing his people, Aelfric refers to people adopting the customs of the Danish and exhorts people not to abandon the native customs on behalf of the Danish ones, and then requests a 'brother Edward', to try to put an end to a 'shameful habit' of drinking and eating in the outhouse, which some of the countrywomen practised at beer parties.

In April 1016 Aethelred died of illness, leaving his son and successor Edmund Ironside to defend the country. The final struggles were complicated by internal dissension, and especially by the treacherous acts of Ealdorman Eadric of Mercia, who opportunistically changed sides to Cnut's party. After the defeat of the English in the battle of Assandun in October 1016, Edmund and Cnut agreed to divide the kingdom so that Edmund would rule Wessex and Cnut Mercia, but Edmund died soon after his defeat in November 1016, making it possible for Cnut to seize power over all England.

In the 11th century, there were three conquests and some Anglo-Saxon people would live through it: one in the aftermath of the conquest of Cnut in 1016; the second after the unsuccessful attempt of battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066; the third after that of William of Normandy in 1066. The consequences of each conquest can only be assessed with hindsight. In 1016, no-one was to know that whatever cultural ramifications were felt then, they would be subsumed half a century later; and in 1066 there was nothing to predict that the effects of William's conquest would be any greater or more lasting than those of Cnut's.

In this period and beyond the Anglo-Saxon culture is changing. Politically and chronologically, the texts of this period are not 'Anglo-Saxon'; linguistically, those written in English (as opposed to Latin or French, the other official written languages of the period) are moving away from the late West Saxon standard that is called 'Old English'. Yet neither are they 'Middle English'; moreover, as Treharne explains, for around three quarters of this period, "there is barely any 'original' writing in English at all". These factors have led to a gap in scholarship implying a discontinuity either side of the Norman Conquest, however this assumption is being challenged.

At first sight, there would seem little to debate. Cnut appears to have adopted wholeheartedly the traditional role of Anglo-Saxon kingship. However an examination of the laws, homilies, wills, and charters dating from this period suggests that as a result of widespread aristocratic death and the fact that Cnut did not systematically introduce a new landholding class, major and permanent alterations occurred in the Saxon social and political structures. Eric John has remarked that for Cnut "the simple difficulty of exercising so wide and so unstable an empire made it necessary to practise a delegation of authority against every tradition of English kingship".

At first sight, there would seem little to debate. Cnut appears to have adopted wholeheartedly the traditional role of Anglo-Saxon kingship. However an examination of the laws, homilies, wills, and charters dating from this period suggests that as a result of widespread aristocratic death and the fact that Cnut did not systematically introduce a new landholding class, major and permanent alterations occurred in the Saxon social and political structures. Eric John has remarked that for Cnut "the simple difficulty of exercising so wide and so unstable an empire made it necessary to practise a delegation of authority against every tradition of English kingship".

The disappearance of the aristocratic families which had traditionally played an active role in the governance of the realm, coupled with Cnut's choice of thegnly advisors, put an end to the balanced relationship between monarchy and aristocracy so carefully forged by the West Saxon Kings. Edward became king in 1042, and given his upbringing might have been considered a Norman by those who lived across the English Channel. Following Cnut's reforms, excessive power was concentrated in the hands of the rival houses of Leofric of Mercia and Godwine of Wessex. Problems also came for Edward from the resentment caused by the king's introduction of Norman friends.

A crisis arose in 1051 when Godwine defied the king's order to punish the men of Dover, who had resisted an attempt by Eustace of Boulogne to quarter his men on them by force. The support of Earl Leofric and Earl Siward enabled Edward to secure the outlawry of Godwine and his sons; and William of Normandy paid Edward a visit during which Edward may have promised William succession to the English throne, although this Norman claim may have been mere propaganda. Godwine and his sons came back the following year with a strong force, and the magnates were not prepared to engage them in civil war but forced the king to make terms.

Some unpopular Normans were driven out, including Archbishop Robert, whose archbishopric was given to Stigand; this act supplied an excuse for the Papal support of William's cause. The fall of England and the Norman Conquest is a multi-generational, multi-family succession problem caused in great part by Athelred's incompetence. By the time William from Normandy, sensing an opportunity, landed his invading force in 1066, the elite of Anglo-Saxon England had changed, although much of the culture and society had stayed the same.

Then came William, the Earl of Normandy, into Pevensey on the evening of St.MichAel's mass, and soon as his men were ready, they built a fortress at Hasting's port. This was told to King Harold, and he gathered then a great army and come towards them at the Hoary Apple Tree, and William came upon him unawares before his folk were ready. But the king nevertheless withstood him very strongly with fighting with those men who would follow him, and there was a great slaughter on either side. Then Harald the King was slain, and Leofwine the Earl, his brother, and Gyrth, and many good men, and the Frenchmen held the place of slaughter.

Following the conquest, the Anglo-Saxon nobility were either exiled or joined the ranks of the peasantry. It has been estimated that only about 8 per cent of the land was under Anglo-Saxon control by 1087. Many Anglo-Saxon nobles fled to Scotland, Ireland, and Scandinavia. The Byzantine Empire became a popular destination for many Anglo-Saxon soldiers, as the Byzantines were in need of mercenaries. The Anglo-Saxons became the predominant element in the elite Varangian Guard, hitherto a largely North Germanic unit, from which the emperor's bodyguard was drawn and continued to serve the empire until the early 15th century. However, the population of England at home remained largely Anglo-Saxon; for them, little changed immediately except that their Anglo-Saxon lord was replaced by a Norman lord.

The chronicler Orderic Vitalis (1075 – about 1142), himself the product of an Anglo-Norman marriage, wrote: "And so the English groaned aloud for their lost liberty and plotted ceaselessly to find some way of shaking off a yoke that was so intolerable and unaccustomed".] The inhabitants of the North and Scotland never warmed to the Normans following the Harrying of the North (1069–1070), where William, according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle utterly "ravaged and laid waste that shire". Many Anglo-Saxon people needed to learn Norman French to communicate with their rulers, but it is clear that among themselves they kept speaking Old English, which meant that England was in an interesting tri-lingual situation: Anglo-Saxon for the common people, Latin for the Church, and Norman French for the administrators, the nobility, and the law courts.

In this time, and due to the cultural shock of the Conquest, Anglo-Saxon began to change very rapidly, and by 1200 or so, it was no longer Anglo-Saxon English, but what scholars call early Middle English. But this language had deep roots in Anglo-Saxon, which was being spoken a lot later than 1066. Research in the early twentieth century, and still continuing today, has shown that a form of Anglo-Saxon was still being spoken, and not merely among uneducated peasants, into the thirteenth century in the West Midlands.

This was J.R.R. Tolkien's major scholarly discovery when he studied a group of texts written in early Middle English called the Katherine Group, because they include the Life of St. Katherine (also, the Life of St. Margaret, the Life and the Passion of St. Juliana, Ancrene Wisse, and Hali Meithhad—these last two teaching how to be a good anchoress and arguing for the goodness of virginity). Tolkien noticed that a subtle distinction preserved in these texts indicated that Old English had continued to be spoken far longer than anyone had supposed. In Old English there is a distinction between two different kinds of verbs.

The Anglo-Saxons had always been defined very closely to the language, now this language gradually changed, and although some people (like the famous scribe known as the Tremulous Hand of Worcester) could read Old English in the thirteenth century. Soon afterwards, it became impossible for people to read Old English, and the texts became useless. The precious Exeter Book, for example, seems to have been used to press gold leaf and at one point had a pot of fish-based glue sitting on top of it. For MichAel Drout this symbolizes the end of the Anglo-Saxons.[Wikipedia].

REVIEW: Fifth-century Britain was a tumultuous place, wracked by violence, upheaval, and uncertainty. The Roman Empire was crumbling throughout western Europe as waves of barbarian invaders overran its borders. By A.D. 410, groups of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes began crossing the North Sea from Germany and southern Scandinavia to claim land in Britain that had been abandoned by the Roman army. These tribes succeeded Rome as the dominant power in central and southern Britain, marking the beginning of what we now call the Anglo-Saxon Age, which would last for more than 600 years.

While the story of this period is known to us in broad strokes, in archaeological terms, there remains much to uncover. The early Anglo-Saxon period is a time whose events are often shrouded in fantasy. This fantastical view can be traced to later, Christian writers who described the pagan world of the fifth and sixth centuries as being inhabited by wizards, warriors, demons, and dragons. Legendary tales, passed down, were often the subject of later Old English works of poetry. Perhaps the most famous of all is the epic work Beowulf, whose eponymous hero battles monsters and fire-breathing dragons.

But some of the details of early Anglo-Saxon life that have been gleaned piecemeal from texts are now being confirmed by archaeology. Such is the case with the recent surprising discovery of a Saxon royal feasting hall. For the last six years the Lyminge Archaeological Project has investigated the modern village of Lyminge, Kent, located a short distance from the famous white cliffs of Dover. Researchers from both the University of Reading and the Kent Archaeological Society are documenting Lyminge’s transition from a pagan royal “vill” into a significant Christian monastic center.

The settlement encompasses both the pre-Christian and later Christian Anglo-Saxon periods and is proving valuable in understanding the development of early English communities. According to Alexandra Knox, archaeologist and Lyminge Archaeological Project research assistant, the work there is supplying a key piece of the puzzle. “The history of the Christian conversion in Kent,” Knox says, “the historically earliest kingdom to be converted in the Anglo-Saxon period, is integral to our understanding of the creation of medieval and, indeed, modern England.”

The Christian Anglo-Saxon community in Lyminge founded an important “double” monastery—home to both monks and nuns—dating from the seventh to ninth century. The existence of this monastery has been known from at least the middle of the nineteenth century, when Canon Jenkins, a local vicar and amateur archaeologist, discovered the remains of the ancient monastic complex. But apart from these Christian ruins, little was known about Lyminge’s earlier history.

During the dark and violent times of the fifth century, pagan warrior kings ruled southern Britain. At Lyminge, current archaeological research is now making it possible to retrace the village’s early history to Anglo-Saxon settlers, just a few decades after the fall of Roman Britain. The recently discovered Anglo-Saxon hall, which researchers believe dates to about 600, would have been an essential feature of any important early Saxon settlement. In Old English poetry the hall is often the scene of royal feasts and banquets. In the story of Beowulf, the hero is tasked with slaying the monster Grendel, who has been terrorizing the famous hall of Heorot.

The royal feasting hall in Lyminge remained undisturbed for nearly 1,400 years, just a few inches below the surface of a village green that lies at the center of the modern town, and within view of the monastery site. It is the first of its kind to be discovered in England in more than 30 years. “Excavating large open areas in villages of medieval origin can be an extremely successful strategy in uncovering the evolution of the Saxon village,” explains Knox. “No large building was visible on the geophysical survey, so it was a great surprise to the team to uncover the full floor plan of such a significant structure.”

Large royal halls such as the one found in Lyminge are known to be associated with local elites and played a central role in early Anglo-Saxon society. The king and his guests would gather to socialize, celebrate victories, or listen to performances. The hall not only hosted legendary feasting parties, sometimes lasting days, but was also a key multipurpose assembly space for early Saxon communities. These halls were the site of essential political, social, religious, and legal activities. Since the feasting hall at Lyminge was constructed from timber and other perishable materials, only the foundation trenches and postholes remain visible.

Its rectangular plan measures approximately 69 by 28 feet, making it comparable to the grandest Saxon halls ever discovered, such as those at Yeavering in Northumberland and Cowdery’s Down in Hampshire. While halls of this type have generally yielded very few significant artifacts, in the case of Lyminge, archaeologists found one important object—an exquisite gilt copper-alloy horse-harness mount was discovered in one of the wall trenches.

The quality of its design, style, and craftsmanship indicate that it most likely belonged to an important Anglo-Saxon warrior, adding archaeological support to the stuff of legends. According to Knox, “This artifact is a direct link to the warrior ideal embodied in Beowulf.” Artifacts such as these are often seen in horse and warrior burials of the fifth and sixth centuries. “The Anglo-Saxon hall,” Knox adds, “provides clear evidence that elite individuals, most likely the kings of Kent, were staying at Lyminge in the pre-Christian period.”

The days of the pagan Anglo-Saxon kings were to be short-lived. After only one or two generations, the settlement that took the royal hall as its symbolic center was abandoned. In another part of Lyminge, on a spur of land above the old pagan village, a new community formed, this time concentrated around a newly built Christian monastery. The monastery at Lyminge has old and storied connections to the earliest Christian Anglo-Saxons.

While the populations of Roman Britain had already converted to Christianity following the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine in 312, the foreign tribes who invaded the island after the Roman collapse were pagans. St. Augustine of Canterbury was commissioned by Pope Gregory to travel to Britain to reestablish Christianity there and to convert the pagan Saxon communities. Shortly after his pilgrimage in the sixth century, the monastery in Lyminge was founded by Queen Æethelburga, daughter of King Aethelbert of Kent, who, in 597, became the first Anglo-Saxon king to be converted to Christianity.

Lyminge was transformed by its Christian monastic settlement, which brought about changes in lifestyle, identity, and behavior of the local population. Recent excavations have revealed a large granary and an industrial-sized ironworking facility that attest to the growth of Lyminge’s economy. The presence of fish bones and other marine evidence shows that the monastic community was connected to broader trade networks and was capable of exploiting coastal resources. This also indicates the impact that Christianity had on diet, as fish became a much more significant staple in the eighth and ninth centuries.

The transition from the Roman Age to the Anglo-Saxon Age in this part of Britain can be understood as a two-part process. The first was characterized by the dominance of pagan warrior kings and the second by the reestablishment of Christianity. The last days of the pagan Saxon kings and the great feasting halls of the age of Beowulf gave way to an era that would be even more influential in the construction of the modern English identity. All is finally visible in the village of Lyminge. [Archaeological Institute of America].