The Twelve Caesars by Michael Grant.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. We do have many other copies of this same title in varying conditions, in "good" through "new" conditions. We also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, some international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardback with Dust Jacket: 294 pages. Publisher: Allen Lane (1979). Dimensions: 10¼ x 8 x 1¼ inches; 2¼ pounds. Michael Grant is considered the greatest popularizer of ancient history of the century, a highly successful and renowned historian of the ancient world. This book is a biography of the lives of “The Twelve Caesars” – the first twelve emperors of Imperial Rome. The book examines the public and private lives of Julius Caesar and the following eleven Roman Emperors. Grant investigates the myths and legends surrounding these men and explores the effects of their public careers on their private lives. If you’re a buff or serious student of Roman History, this is a “must have”, and is considered amongst the best translations of Suetonius.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. Lightly read hardcover w/dustjacket. Allen Lane (1979) 288 pages. Book appears as if it was read once, albeit by someone with a very light hand. From the inside the book is almost pristine; the pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, and by all appearances, very lightly read. From outside the dustjacket evidences only very mild edge and corner shelfwear, principally in the form of mild crinkling to the dustjacket spine head and heel, the top open corners of the dustjacket (the "tips"), front and back, and the top edge of the front side of the dustjacket. There are no noteworthy tears, chips, etc. Beneath the dustjacket the full cloth covers are clean and unsoiled, and like the overlying dustjacket, evidences only very mild edge and corner shelfwear. Except for the fact that the book evidences light reading wear and the dustjacket some mild edge crinkling,the overall condition of the book is not too terribly distant from what might pass as "new" from an open-shelf book store (such as Barnes & Noble, or B. Dalton, for example) wherein patrons are permitted to browse open stock, and so otherwise "new" books often show a little handling/shelf/browsing wear. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #053.2L.

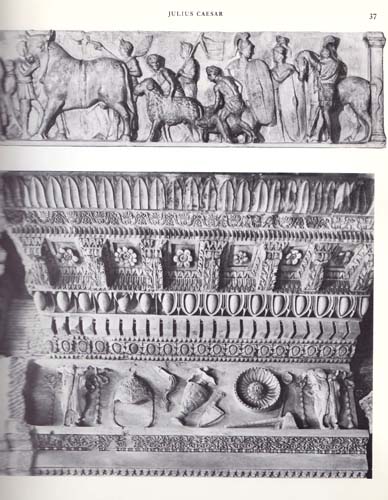

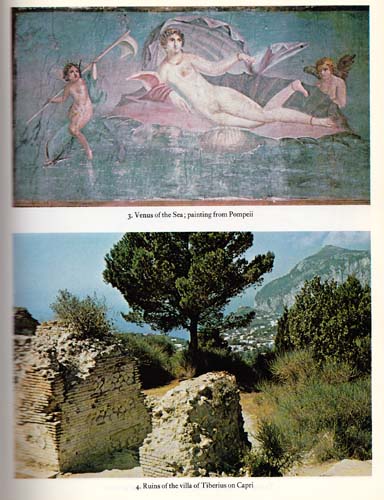

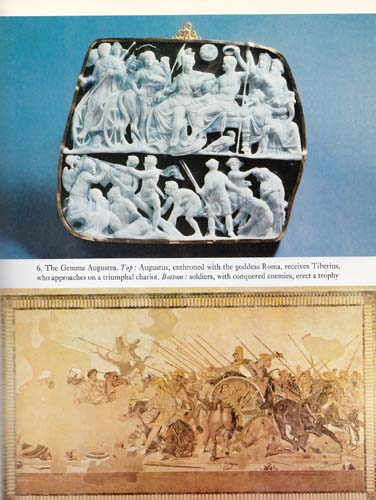

PLEASE SEE IMAGES BELOW FOR JACKET DESCRIPTION(S) AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

REVIEW: Conspiracy, suspicion, power, corruption, poison, conquests, marauders, murders and more murders. Such is the history of Roman Empire. Then again there are copious examples from every nation's history of such dastardly acts to grab power, from Egyptians pharos, to Bourbons, to Indian Moguls, to British royalty. Human nature has changed very little in two thousand years. Now instead of murdering opponents, we vilify them to such an extent that populace loathes and discards them in the garbage bin. Grant discounts Lord Acton's polemical quote "Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely". Later Lord Acton had modified in saying that too much responsibility coupled with intense fear of life corrupts absolutely. It is very hard to imagine for us, normal souls, with two thousand years separation, what we would do if we were given absolute power over everybody and every thing. But would we resort to killing our own mother like Nero, or have sexual relationships with sisters, like Caligula. It is quite possible if Nixon were the Roman Empire and Watergate exploded on the stage, he would not have hesitated in having few senators, congressmen dispatched in due haste.

If there are any good emperors, the vote should go to Augustus, starting from nothing, except, Julius Caesar's adopted nephew, to emerge as victor, after defeating all his rivals, one by one including Mark Anthony and his beloved Cleopatra. Vespatian can also be called a hero to come up the ranks from an ordinary family to start a dynasty and consolidate Rome after bitter civil war. Agripina the younger stands out among all the women , (if one can discount Livia, Augustus’s wife in Graves incomparable "I, Claudius", where he portrays Livia as villai) who is married to aging Claudius, the fourth emperor. She runs the kingdom in his name and manages to bypass Claudius own son and places her son, Nero on the throne. How does Nero reward her? He lets her go out on a faulty boat to drown. What are sons for? Few emperors, imperators were tyrants, megalomanias and sadists and most of them were murdered by conspiracy. Why any body wanted to be one is puzzling as no doubt they all knew the history so well. So Lord Acton is right. It is human nature to lust for absolute power.

REVIEW: Grant is clearly an expert in his field and often provides terrific insights. I think this is my favorite of all Grant's works that I have read. Part of that is because I love Roman History and perhaps another factor is that this book tends to stick more or less to a chronological narrative, preventing it from becoming too dry. My favorite part in this book is the conclusion. Grant's enlightened insight into the job of being an emperor is outstanding! Overall a very good volume and an easy one to read if you are a novice in classical history. Grant has always done a great job with somehow making a complex topic easy to read for the masses. He covers the first twelve emperors adequately, but to get more out of each one you really need to purchase a separate book on each of the emperors. I liked this book because it gave a good overview of each of them and I was intrigued enough about the lives of a few of them to go out and buy an additional book. If you want a good overview of the emperors without much detail then this is a great book.

REVIEW: Grant's "The Twelve Caesars" is an excellent resource through which to learn about the first twelve Roman "emperors" - Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. I say "emperors" in quotes because, as Grant so ably explains, the early Roman rulers, starting with Caesar Augustus, maintained every pretense that they were merely guardians of a republic. Even the word "imperator" was ambiguous. But as time went on, largely through the political genius of Augustus, the system evolved into de jure as well as a de facto imperial rule. Grant debunks as propaganda most of the salacious gossip surrounding the Caesars - which, to any of us familiar with the story of Tiberius and his "minnows," is a little disconcerting. But truth is vastly more interesting than fiction, and Grant delivers it in abundance.

ANCIENT ROME: One of the greatest civilizations of recorded history was the ancient Roman Empire. The Roman civilization, in relative terms the greatest military power in the history of the world, was founded in the 8th century (B.C.) on seven hills alongside Italy’s Tiber River. By the 4th Century (B.C.) the Romans were the dominant power on the Italian Peninsula, having defeated the Etruscans, Celts, Latins, and Greek Italian colonies. In the 3rd Century (B.C.) the Romans conquered Sicily, and in the following century defeated Carthage, and controlled Greece. Throughout the remainder of the 2nd Century (B.C.) the Roman Empire continued its gradual conquest of the Hellenistic (Greek Colonial) World by conquering Syria and Macedonia; and finally came to control Egypt and much of the Near East and Levant (Holy Land) in the 1st Century (B.C.).

The pinnacle of Roman power was achieved in the 1st Century (A.D.) as Rome conquered much of Britain and Western Europe. At its peak, the Roman Empire stretched from Britain in the West, throughout most of Western, Central, and Eastern Europe, and into Asia Minor. For a brief time, the era of “Pax Romana”, a time of peace and consolidation reigned. Civilian emperors were the rule, and the culture flourished with a great deal of liberty enjoyed by the average Roman Citizen. However within 200 years the Roman Empire was in a state of steady decay, attacked by Germans, Goths, and Persians. The decline was temporarily halted by third century Emperor Diocletian.

In the 4th Century (A.D.) the Roman Empire was split between East and West. The Great Emperor Constantine again managed to temporarily arrest the decay of the Empire, but within a hundred years after his death the Persians captured Mesopotamia, Vandals infiltrated Gaul and Spain, and the Goths even sacked Rome itself. Most historians date the end of the Western Roman Empire to 476 (A.D.) when Emperor Romulus Augustus was deposed. However the Eastern Roman Empire (The Byzantine Empire) survived until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 A.D.

In the ancient world valuables such as coins and jewelry were commonly buried for safekeeping, and inevitably the owners would succumb to one of the many perils of the ancient world. Oftentimes the survivors of these individuals did not know where the valuables had been buried, and today, thousands of years later (occasionally massive) caches of coins and rings are still commonly uncovered throughout Europe and Asia Minor.

Throughout history these treasures have been inadvertently discovered by farmers in their fields, uncovered by erosion, and the target of unsystematic searches by treasure seekers. With the introduction of metal detectors and other modern technologies to Eastern Europe in the past three or four decades, an amazing number of new finds are seeing the light of day thousands of years after they were originally hidden by their past owners. And with the liberalization of post-Soviet Eastern Europe in the 1990’s, significant new sources opened eager to share these ancient treasures. [AncientGifts].

History of Rome.

According to legend, Ancient Rome was founded by the two brothers, and demi-gods, Romulus and Remus, on 21 April 753 B.C. The legend claims that, in an argument over who would rule the city (or, in another version, where the city would be located) Romulus killed Remus and named the city after himself. This story of the founding of Rome is the best known but it is not the only one.

Other legends claim the city was named after a woman, Roma, who traveled with Aeneas and the other survivors from Troy after that city fell. Upon landing on the banks of the Tiber River, Roma and the other women objected when the men wanted to move on. She led the women in the burning of the Trojan ships and so effectively stranded the Trojan survivors at the site which would eventually become Rome.

Aeneas of Troy is featured in this legend and also, famously, in Virgil's Aeneid, as a founder of Rome and the ancestor of Romulus and Remus, thus linking Rome with the grandeur and might which was once Troy. Still other theories concerning the name of the famous city suggest it came from Rumon, the ancient name for the Tiber River, and was simply a place-name given to the small trading centre established on its banks or that the name derived from an Etruscan word which could have designated one of their settlements. Originally a small town on the banks of the Tiber, Rome grew in size and strength, early on, through trade. The location of the city provided merchants with an easily navigable waterway on which to traffic their goods. The city was ruled by seven kings, from Romulus to Tarquin, as it grew in size and power. Greek culture and civilization, which came to Rome via Greek colonies to the south, provided the early Romans with a model on which to build their own culture. From the Greeks they borrowed literacy and religion as well as the fundamentals of architecture.

Though Rome owed its prosperity to trade in the early years, it was war which would make the city a powerful force in the ancient world. The wars with the North African city of Carthage (known as the Punic Wars, 264-146 B.C.) consolidated Rome's power and helped the city grow in wealth and prestige. Rome and Carthage were rivals in trade in the Western Mediterranean and, with Carthage defeated, Rome held almost absolute dominance over the region; though there were still incursions by pirates which prevented complete Roman control of the sea.

As the Republic of Rome grew in power and prestige, the city of Rome began to suffer from the effects of corruption, greed and the over-reliance on foreign slave labor. Gangs of unemployed Romans, put out of work by the influx of slaves brought in through territorial conquests, hired themselves out as thugs to do the bidding of whatever wealthy Senator would pay them. The wealthy elite of the city, the Patricians, became ever richer at the expense of the working lower class, the Plebeians.

In the 2nd century B.C., the Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, two Roman tribunes, led a movement for land reform and political reform in general. Though the brothers were both killed in this cause, their efforts did spur legislative reforms and the rampant corruption of the Senate was curtailed (or, at least, the Senators became more discreet in their corrupt activities). By the time of the First Triumvirate, both the city and the Republic of Rome were in full flourish.

Even so, Rome found itself divided across class lines. The ruling class called themselves Optimates (the best men) while the lower classes, or those who sympathized with them, were known as the Populares (the people). These names were applied simply to those who held a certain political ideology; they were not strict political parties nor were all of the ruling class Optimates nor all of the lower classes Populares.

In general, the Optimates held with traditional political and social values which favored the power of the Senate of Rome and the prestige and superiority of the ruling class. The Populares, again generally speaking, favored reform and democratization of the Roman Republic. These opposing ideologies would famously clash in the form of three men who would, unwittingly, bring about the end of the Roman Republic.

Marcus Licinius Crassus and his political rival, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) joined with another, younger, politician, Gaius Julius Caesar, to form what modern historians call the First Triumvirate of Rome (though the Romans of the time never used that term, nor did the three men who comprised the triumvirate). Crassus and Pompey both held the Optimate political line while Caesar was a Populare.

The three men were equally ambitious and, vying for power, were able to keep each other in check while helping to make Rome prosper. Crassus was the richest man in Rome and was corrupt to the point of forcing wealthy citizens to pay him `safety' money. If the citizen paid, Crassus would not burn down that person's house but, if no money was forthcoming, the fire would be lighted and Crassus would then charge a fee to send men to put the fire out. Although the motive behind the origin of these fire brigades was far from noble, Crassus did effectively create the first fire department which would, later, prove of great value to the city.

Both Pompey and Caesar were great generals who, through their respective conquests, made Rome wealthy. Though the richest man in Rome (and, it has been argued, the richest in all of Roman history) Crassus longed for the same respect people accorded Pompey and Caesar for their military successes. In 53 B.C. he lead a sizeable force against the Parthians at Carrhae, in modern day Turkey, where he was killed when truce negotiations broke down.

With Crassus gone, the First Triumvirate disintegrated and Pompey and Caesar declared war on each other. Pompey tried to eliminate his rival through legal means and had the Senate order Caesar to Rome to stand trial on assorted charges. Instead of returning to the city in humility to face these charges, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River with his army in 49 B.C. and entered Rome at the head of it.

He refused to answer the charges and directed his focus toward eliminating Pompey as a rival. Pompey and Caesar met in battle at Pharsalus in Greece in 48 B.C. where Caesar's numerically inferior force defeated Pompey's greater one. Pompey himself fled to Egypt, expecting to find sanctuary there, but was assassinated upon his arrival. News of Caesar's great victory against overwhelming numbers at Pharsalus had spread quickly and many former friends and allies of Pompey swiftly sided with Caesar, believing he was favored by the gods.

Julius Caesar was now the most powerful man in Rome. He effectively ended the period of the Republic by having the Senate proclaim him dictator. His popularity among the people was enormous and his efforts to create a strong and stable central government meant increased prosperity for the city of Rome. He was assassinated by a group of Roman Senators in 44 B.C., however, precisely because of these achievements.

The conspirators, Brutus and Cassius among them, seemed to fear that Caesar was becoming too powerful and that he might eventually abolish the Senate. Following his death, his right-hand man, and cousin, Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) joined forces with Caesar's nephew and heir, Gaius Octavius Thurinus (Octavian) and Caesar's friend, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, to defeat the forces of Brutus and Cassius at the Battle of Phillippi in 42 B.C.

Octavian, Antony and Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate of Rome but, as with the first, these men were also equally ambitious. Lepidus was effectively neutralized when Antony and Octavian agreed that he should have Hispania and Africa to rule over and thereby kept him from any power play in Rome. It was agreed that Octavian would rule Roman lands in the west and Antony in the east.

Antony's involvement with the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII, however, upset the balance Octavian had hoped to maintain and the two went to war. Antony and Cleopatra's combined forces were defeated at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. and both later took their own lives. Octavian emerged as the sole power in Rome. In 27 B.C. he was granted extraordinary powers by the Senate and took the name of Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome. Historians are in agreement that this is the point at which the history of Rome ends and the history of the Roman Empire begins.

History of Roman Republic.

In the late 6th century B.C., the small city-state of Rome overthrew the shackles of monarchy and created a republican government that, in theory if not always in practice, represented the wishes of its citizens. From this basis the city would go on to conquer all of the Italian peninsula and large parts of the Mediterraean world and beyond. The Republic and its insitutions of government would endure for five centuries, until, wrecked by civil wars, it would transform into a Principate ruled by emperors. Even then many of the politcal bodies, notably the Senate, created in the Republican period would endure, albeit with a reduction in power.

The years prior to the rise of the Republic are lost to myth and legend. No contemporary written history of this period has survived. Although much of this history had been lost, the Roman historian Livy (59 B.C. – 17 A.D.) was still able to write a remarkable History of Rome - 142 volumes - recounting the years of the monarchy through the fall of the Republic. Much of his history, however, especially the early years, was based purely on myth and oral accounts.

Contrary to some interpretations, the fall of the monarchy and birth of the republic did not happen overnight. Some even claim it was far from bloodless. Historian Mary Beard in her SPQR wrote that the transformation from monarchy to republic was “borne over a period of decades, if not, centuries.” Prior to the overthrow of the last king, Tarquinius Superbus or Tarquin the Proud in 510 B.C., the history of the city is mired in stories of valor and war. Even the founding of the city is mostly legend and many people have preferred the myth over fact anyway.

For years Rome had admired the Hellenistic culture of the Greeks, and so it easily embraced the story of Aeneas and the founding of Rome as penned by Roman author Virgil in his heroic saga The Aeneid. This story gave the Romans a link to an ancient, albeit Greek, culture. This mythical tale is about Aeneas and his followers who, with the assistance of the goddess Venus, escaped the city of Troy as it fell to the Greeks in the Trojan War. Jupiter’s wife Juno constantly interfered with the story's hero Aeneas throughout the tale.

After a brief stay in Carthage, Aeneas eventually made his way to Italy and Latium, finally fulfilling his destiny. His descendants were the twins Romulus and Remus - the illegitimate sons of Mars, the god of war, and the princess Rhea Silvia, the daughter of the true king of Alba Longa. Rescued from drowning by a she-wolf and raised by a shepherd, Romulus eventually defeated his brother in battle and founded the city of Rome, becoming its first king. So the legend goes.

After Tarquin’s exit, Rome suffered from both external and internal conflict. Much of the 5th century B.C. was spent struggling, not thriving. From 510 B.C. to 275 B.C., while the government grappled with a number of internal political issues, the city grew to become the prevailing power over the entire Italian peninsula. From the Battle of Regallus (496 B.C.), where Rome was victorious over the Latins, to the Pyrrhic Wars (280 – 275 B.C.) against Pyrrhus of Epirus, Rome emerged as a dominant, warring superpower in the west.

Through this expansion, the social and political structure of the Republic gradually evolved. From this simple beginning, the city would create a new government, a government that would one day dominate an area from the North Sea southward through Gaul and Germania, westward to Hispania, and eastward to Greece, Syria and North Africa. The great Mediterranean became a Roman lake. These lands would remain under the control of Rome throughout the Republic and well into the formative years of the Roman Empire.

However, before it could become this dominant military force, the city had to have a stable government, and it was paramount that they avoid the possibility of one individual seizing control. In the end they would create a system exhibiting a true balance of power. Initially, after the fall of the monarchy, the Republic fell under the control of the great families - the patricians, coming from the word patres or fathers. Only these great families could hold political or religious offices. The remaining citizens or plebians had no political authority although many of them were as wealthy as the patricians. However, much to the dismay of the patricians, this arrangement could not and would not last.

Tensions between the two classes continued to grow, especially since the poorer residents of the city provided the bulk of the army. They asked themselves why they should fight in a war if all of the profits go to the wealthy. Finally, in 494 B.C. the plebians went on strike, gathering outside Rome and refusing to move until they were granted representation; this was the famed Conflict of Orders or the First Succession of the Plebs. The strike worked, and the plebians would be rewarded with an assembly of their own - the Concilium Plebis or Council of the Plebs.

Although the government of Rome could never be considered a true democracy, it did provide many of its citizens (women excluded) with a say in how their city was ruled. Through their rebellion, the plebians had entered into a system where power lay in a number of magistrates (the cursus honorum) and various assemblies. This executive power or imperium resided in two consuls. Elected by the Comitia Centuriata, a consul ruled for only one year, presiding over the Senate, proposing laws, and commanding the armies.

Uniquely, each consul could veto the decision of the other. After his term was completed, he could become a pro-consul, governing one of the republic’s many territories, which was an appointment that could make him quite wealthy. There were several lesser magistrates: a praetor (the only other official with imperium power) who served as a judicial officer with civic and provincial jurisdiction, a quaestor who functioned as the financial administrator, and the aedile who supervised urban maintenance such as roads, water and food supplies, and the annual games and festivals.

Lastly, there was the highly coveted position of censor, who held office for only 18 months. Elected every five years, he was the census taker, reviewing the list of citizens and their property. He could even remove members of the Senate for improper behavior. There was, however, one final position - the unique office of dictator. He was granted complete authority and was only named in times of emergency, usually serving for only six months. The most famous one, of course, was Julius Caesar; who was named dictator for life.

Aside from the magistrates there were also a number of assemblies. These assemblies were the voice of the people (male citizens only), thereby allowing for the opinions of some to be heard. Foremost of all the assemblies was the Roman Senate (a remnant of the old monarchy). Although unpaid, Senators served for life unless they were removed by a censor for public or private misconduct. While this body had no true legislative power, serving only as advisors to the consul and later the emperor, they still wielded considerable authority.

They could propose laws as well as oversee foreign policy, civic administration, and finances. Power to enact laws, however, was given to a number of popular assemblies. All of the Senate’s proposals had to be approved by either of two popular assemblies: the Comitia Centuriata, who not only enacted laws but also elected consuls and declared war, and the Concilium Plebis, who conveyed the wishes of the plebians via their elected tribunes. These assemblies were divided into blocks and each of these blocks voted as a unit. Aside from these two major legislative bodies, there were also a number of smaller tribal assemblies.

The Concilium Plebis came into existence as a result of the Conflict of Orders - a conflict between the plebians and patricians for political power. In the Concilium Plebis, aside from passing laws pertinent to the wishes of the plebians, the members elected a number of tribunes who spoke on their behalf. Although this “Council of the Plebs” initially gave the plebians some voice in government, it did not prove to be sufficient. In 450 B.C. the Twelve Tables were enacted in order to appease a number of plebian concerns.

It became the first recorded Roman law code. The Tables tackled domestic problems with an emphasis on both family life and private property. For instance, plebians were not only prohibited from imprisonment for debt but also granted the right to appeal a magistrate’s decision. Later, plebians were even allowed to marry patricians and become consuls. Over time the rights of the plebians continued to increase. In 287 B.C. the Lex Hortensia declared that all laws passed by the Concilium Plebis were binding to both plebians and patricians.

This unique government allowed the Republic to grow far beyond the city’s walls. Victory in the three Punic Wars (264 – 146 B.C.) waged against Carthage was the first step of Rome growing beyond the confines of the peninsula. After years of war and the embarrassment of defeat at the hands of Hannibal, the Senate finally followed the advice of the outspoken Cato the Elder who said “Carthago delenda est!” or “Carthage must be destroyed!” Rome’s destruction of the city after the Battle of Zama in 146 B.C. and the defeat of the Greeks in the four Macedonian Wars established the Republic as a true Mediterranean power.

The submission of the Greeks brought the rich Hellenistic culture to Rome, that is its art, philosophy and literature. Unfortunately, despite the growth of the Republic, the Roman government was never meant to run an empire. According to historian Tom Holland in his Rubicon, the Republic always seemed to be on the brink of political collapse. The old agrarian economy could not and would not be successfully transferred and only further broadened the gap between the rich and poor. Rome, however, was more than just a warrior state. At home Romans believed in the importance of the family and the value of religion. They also believed that citizenship or civitas defined what it meant to be truly civilized.

This concept of citizenship would soon be put to the test when the Roman territories began to challenge Roman authority. However, this constant state of war had not only made the Republic wealthy but it also helped mold its society. After the Macedonian Wars, the influence of the Greeks affected both Roman culture and religion. Under this Greek influence, the traditional Roman gods transformed. In Rome an individual’s personal expression of belief was unimportant, only a strict adherence to a rigid set of rituals, avoiding the dangers of religious fervor. Temples honoring these gods would be built throughout the empire.

Elsewhere in Rome the division of the classes could best be seen within the city walls in the tenements. Rome was a refuge to many people who left the surrounding towns and farms seeking a better way of life. However, an unfulfilled promise of jobs forced many people to live in the poorer parts of the city. The jobs they sought were often not there, resulting in an epidemic of homeless inhabitants. While many of the wealthier citizens resided on Palatine Hill, others lived in ramshackle apartments that were over-crowded and extremely dangerous - many lived in constant fear of fire and collapse.

Although the lower floors of these buildings contained shops and more suitable housing, the upper floors were for the poorer residents, there was no access for natural light, no running water, and no toilets. The streets were poorly lit and since there was no police force, crime was rampant. Refuse, even human waste, was routinely dumped onto the streets, not only causing a terrible stench but served as a breeding ground for disease. All of this added to an already disgruntled populace.

This continuing struggle between the have and have nots would remain until the Republic finally collapsed. owever, there were those in power who tried to find a solution to the existing problems. In the 2nd century B.C., two brothers, both tribunes, tried but failed to make the necessary changes. Among a number of reform proposals, Tiberius Gracchus suggested to give land to both the unemployed and small farmers. Of course, the Senate, many of whom were large landowners, vehemently objected. Even the Concilium Plebis rejected the idea.

Although his suggestion eventually became law, it could not be enforced. Riots soon followed and 300 people, including Tiberius, were killed. Unfortunately, a similar destiny awaited his brother. While Gaius Gracchus also supported the land distribution idea, his fate was sealed when he proposed to give citizenship to all Roman allies. Like his big brother, his proposals met with considerable resistance. 3,000 of his supporters were killed and he chose suicide. The failure of the brothers to achieve some balance in Rome would be one of a number of indicators that the Republic was doomed to fall.

Later, another Roman would rise to initiate a series of reforms. Sulla and his army marched on Rome and seized power, defeating his enemy Gaius Marius. Assuming power in 88 B.C., Sulla quickly defeated King Mithridates of Pontus in the East, crushed the Samnites with the help of the generals Pompey and Crassus, purged the Roman Senate (80 were killed or exiled), reorganized the law courts, and enacted a number of reforms. He retired peacefully in 79 B.C.

Unlike the Empire, the Republic would not collapse due to any external threat but instead fell to an internal menace. It came from the inability of the Republic to adjust to a constantly expanding empire. Even the ancient Sibylline prophecies predicted that failure would come internally, not by foreign invaders. There were a number of these internal warnings. The demand of the Roman allies for citizenship was one sign of this unrest - the so-called Social Wars of the 1st century B.C. (90 – 88 B.C.).

For years the Roman allies had paid tribute and provided soldiers for war but were not considered citizens. Like their plebian kindred years earlier, they wanted representation. It took a rebellion for things to change. Although the Senate had warned the Roman citizens that awarding these people citizenship would be dangerous, full citizenship was finally granted to all people (slaves excluded) in the entire Italian peninsula. Later, Julius Caesar would extend citizenship beyond Italy and grant it to the people of Spain and Gaul.

About this time the city witnessed a serious threat to its very survival when Marcus Tillius Cicero, the Roman statesman and poet, uncovered a conspiracy led by the Roman senator Lucius Sergius Catiline to overthrow the Roman government. Cicero also believed that the Republic was declining due to moral decay. Problems such as this together with fear and unrest came to the attention of three men in 60 B.C.: Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus. Crassus had gained fame by his defeat of Spartacus and his followers in 71 B.C. Pompey had distinguished himself in Spain as well as in the East.

Caesar had proven himself as an able commander. Together, the three men formed what historians have named the First Triumvirate or Gang of Three. For almost a decade they controlled both consulships and military commands. After Caesar left the office of consul in 59 B.C., he and his army moved northward into Gaul and Germania. Pompey became the governor of Spain (although he ruled from Rome) while Crassus sought fame in the east where, unfortunately for him, he was eventually defeated and killed at the Battle of Carrhae.

Growing tension between Pompey and Caesar escalated. Pompey was jealous of Caesar’s success and fame while Caesar wanted a return to politics. Eventually these differences brought them to battle, and in 48 B.C. they met at Pharsalus. Pompey was defeated, escaping to Egypt where he was killed by Ptolemy XIII. Caesar fulfilled his destiny by securing both the eastern provinces and northern Africa, returning to Rome a hero only to be declared dictator for life.

Many of his enemies, as well as several allies, saw his new position as a serious threat to the foundation of the Republic, and despite a number of popular reforms, his assassination on the Ides of March in 44 B.C. brought the Republic to its knees. His heir and step-son Octavian subdued Mark Antony, eventually becoming the first emperor of Rome as Augustus. The Republic was gone and in its ashes rose the Roman Empire.

History of Roman Empire: The Roman Empire, at its height (circa 117 A.D.), was the most extensive political and social structure in western civilization. By 285 A.D. the empire had grown too vast to be ruled from the central government at Rome and so was divided by Emperor Diocletian (284-305 A.D.) into a Western and an Eastern Empire. The Roman Empire began when Augustus Caesar (27 B.C.-14 A.D.) became the first emperor of Rome and ended, in the West, when the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic King Odoacer (476 A.D.). In the East, it continued as the Byzantine Empire until the death of Constantine XI and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 A.D. The influence of the Roman Empire on western civilization was profound in its lasting contributions to virtually every aspect of western culture.

Following the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C., Gaius Octavian Thurinus, Julius Caesar's nephew and heir, became the first emperor of Rome and took the name Augustus Caesar. Although Julius Caesar is often regarded as the first emperor of Rome, this is incorrect; he never held the title "Emperor" but, rather, "Dictator", a title the senate could not help but grant him, as Caesar held supreme military and political power at the time. In contrast, the senate willingly granted Augustus the title of emperor, lavishing praise and power on him because he had destroyed Rome's enemies and brought much needed stability.

Augustus ruled the empire from 31 B.C. until 14 A.D. when he died. In that time, as he said himself, he "found Rome a city of clay but left it a city of marble." Augustus reformed the laws of the city and, by extension, the empire’s, secured Rome's borders, initiated vast building projects (carried out largely by his faithful general Agrippa, who built the first Pantheon), and secured the empire a lasting name as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, political and cultural powers in history. The Pax Romana (Roman Peace), also known as the Pax Augusta, which he initiated, was a time of peace and prosperity hitherto unknown and would last over 200 years.

Following Augustus’ death, power passed to his heir, Tiberius, who continued many of the emperor’s policies but lacked the strength of character and vision which so defined Augustus. This trend would continue, more or less steadily, with the emperors who followed: Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. These first five rulers of the empire are referred to as the Julio-Claudian Dynasty for the two family names they descended from (either by birth or through adoption), Julius and Claudius.

Although Caligula has become notorious for his depravity and apparent insanity, his early rule was commendable as was that of his successor, Claudius, who expanded Rome’s power and territory in Britain; less so was that of Nero. Caligula and Claudius were both assassinated in office (Caligula by his Praetorian Guard and Claudius, apparently, by his wife). Nero’s suicide ended the Julio-Claudian Dynasty and initiated the period of social unrest known as The Year of the Four Emperors.

These four rulers were Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. Following Nero’s suicide in 68 A.D., Galba assumed rule (69 A.D.) and almost instantly proved unfit for the responsibility. He was assassinated by the Praetorian Guard. Otho succeeded him swiftly on the very day of his death, and ancient records indicate he was expected to make a good emperor. General Vitellius, however, sought power for himself and so initiated the brief civil war which ended in Otho’s suicide and Vitellius’ ascent to the throne.

Vitellius proved no more fit to rule than Galba had been, as he almost instantly engaged in luxurious entertainments and feasts at the expense of his duties. The legions declared for General Vespasian as emperor and marched on Rome. Vitellius was murdered by Vespasian’s men, and Vespasian took power exactly one year from the day Galba had first ascended to the throne.

Vespasian founded the Flavian Dynasty which was characterized by massive building projects, economic prosperity, and expansion of the empire. Vespasian ruled from 69-79 A.D., and in that time, initiated the building of the Flavian Amphitheatre (the famous Coliseum of Rome) which his son Titus (ruled 79-81 A.D.) would complete. Titus’ early reign saw the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. which buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Ancient sources are universal in their praise for his handling of this disaster as well as the great fire of Rome in 80 A.D. Titus died of a fever in 81 A.D. and was succeeded by his brother Domitian who ruled from 81-96 A.D. Domitian expanded and secured the boundaries of Rome, repaired the damage to the city caused by the great fire, continued the building projects initiated by his brother, and improved the economy of the empire. Even so, his autocratic methods and policies made him unpopular with the Roman Senate, and he was assassinated in 96 A.D.

Domitian's successor was his advisor Nerva who founded the Nervan-Antonin Dynasty which ruled Rome 96-192 A.D. This period is marked by increased prosperity owing to the rulers known as The Five Good Emperors of Rome. Between 96 and 180 A.D., five exceptional men ruled in sequence and brought the Roman Empire to its height: Nerva (96-98), Trajan (98-117), Hadrian (117-138), Antoninus Pius (138-161), and Marcus Aurelius (161-180).

Under their leadership, the Roman Empire grew stronger, more stable, and expanded in size and scope. Lucius Verus and Commodus are the last two of the Nervan-Antonin Dynasty. Verus was co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius until his death in 169 A.D. and seems to have been fairly ineffective. Commodus, Aurelius’ son and successor, was one of the most disgraceful emperors Rome ever saw and is universally depicted as indulging himself and his whims at the expense of the empire. He was strangled by his wrestling partner in his bath in 192 A.D., ending the Nervan-Antonin Dynasty and raising the prefect Pertinax (who most likely engineered Commodus’ assassination) to power.

Pertinax governed for only three months before he was assassinated. He was followed, in rapid succession, by four others in the period known as The Year of the Five Emperors, which culminated in the rise of Septimus Severus to power. Severus ruled Rome from 193-211 A.D., founded the Severan Dynasty, defeated the Parthians, and expanded the empire. His campaigns in Africa and Britain were extensive and costly and would contribute to Rome’s later financial difficulties. He was succeeded by his sons Caracalla and Geta, until Caracalla had his brother murdered.

Caracalla ruled until 217 A.D., when he was assassinated by his bodyguard. It was under Caracalla’s reign that Roman citizenship was expanded to include all free men within the empire. This law was said to have been enacted as a means of raising tax revenue, simply because, after its passage, there were more people the central government could tax. The Severan Dynasty continued, largely under the guidance and manipulation of Julia Maesa (referred to as `empress’), until the assassination of Alexander Severus in 235 A.D. which plunged the empire into the chaos known as The Crisis of the Third Century (lasting from 235-284 A.D.).

This period, also known as The Imperial Crisis, was characterized by constant civil war, as various military leaders fought for control of the empire. The crisis has been further noted by historians for widespread social unrest, economic instability (fostered, in part, by the devaluation of Roman currency by the Severans), and, finally, the dissolution of the empire which broke into three separate regions. The empire was reunited by Aurelian (270-275 A.D.) whose policies were further developed and improved upon by Diocletian who established the Tetrarchy (the rule of four) to maintain order throughout the empire.

Even so, the empire was still so vast that Diocletian divided it in half in 285 A.D. to facilitate more efficient administration. In so doing, he created the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire). Since a leading cause of the Imperial Crisis was a lack of clarity in succession, Diocletian decreed that successors must be chosen and approved from the outset of an individual’s rule. Two of these successors were the generals Maxentius and Constantine. Diocletian voluntarily retired from rule in 305 A.D., and the tetrarchy dissolved as rival regions of the empire vied with each other for dominance.

Following Diocletian’s death in 311 A.D., Maxentius and Constantine plunged the empire again into civil war. In 312 A.D. Constantine defeated Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and became sole emperor of both the Western and Eastern Empires (ruling from 306-337 A.D.). Believing that Jesus Christ was responsible for his victory, Constantine initiated a series of laws such as the Edict of Milan (317 A.D.) which mandated religious tolerance throughout the empire and, specifically, tolerance for the faith which came to known as Christianity.

In the same way that earlier Roman emperors had claimed a special relationship with a deity to augment their authority and standing (Caracalla with Serapis, for example, or Diocletian with Jupiter), Constantine chose the figure of Jesus Christ. At the First Council of Nicea (325 A.D.), he presided over the gathering to codify the faith and decide on important issues such as the divinity of Jesus and which manuscripts would be collected to form the book known today as The Bible. He stabilized the empire, revalued the currency, and reformed the military, as well as founding the city he called New Rome on the site of the former city of Byzantium (modern day Istanbul) which came to be known as Constantinople.

He is known as Constantine the Great owing to later Christian writers who saw him as a mighty champion of their faith but, as has been noted by many historians, the honorific could as easily be attributed to his religious, cultural, and political reforms, as well as his skill in battle and his large-scale building projects. After his death, his sons inherited the empire and, fairly quickly, embarked on a series of conflicts with each other which threatened to undo all that Constantine had accomplished.

His three sons, Constantine II, Constantius II, and Constans divided the Roman Empire between them but soon fell to fighting over which of them deserved more. In these conflicts, Constantine II and Constans were killed. Constantius II died later after naming his cousin Julian his successor and heir. Emperor Julian ruled for only two years (361-363 A.D.) and, in that time, tried to return Rome to her former glory through a series of reforms aimed at increasing efficiency in government.

As a Neo-Platonic philosopher, Julian rejected Christianity and blamed the faith; and Constantine’s adherence to it, for the decline of the empire. While officially proclaiming a policy of religious tolerance, Julian systematically removed Christians from influential government positions, banned the teaching and spread of the religion, and barred Christians from military service. His death, while on campaign against the Persians, ended the dynasty Constantine had begun. He was the last pagan emperor of Rome and came to be known as "Julian the Apostate" for his opposition to Christianity.

After the brief rule of Jovian, who re-established Christianity as the dominant faith of the empire and repealed Julian’s various edicts, the responsibility of emperor fell to Theodosius I. Theodosius I (379-395 A.D.) took Constantine’s and Jovian’s religious reforms to their natural ends, outlawed pagan worship throughout the empire, closed the schools and universities, and converted pagan temples into Christian churches.

It was during this time that Plato’s famous Academy was closed by Theodosius’ decree. Many of his reforms were unpopular with both the Roman aristocracy and the common people who held to the traditional values of pagan practice. The unity of social duties and religious belief which paganism provided was severed by the institution of a religion which removed the gods from the earth and human society and proclaimed only one God who ruled from the heavens.

Theodosius I devoted so much effort to promoting Christianity that he seems to have neglected other duties as emperor and would be the last to rule both Eastern and Western Empires. From 376-382 A.D., Rome fought a series of battles against invading Goths known today as the Gothic Wars. At the Battle of Adrianople, 9 August 378 A.D., the Roman Emperor Valens was defeated, and historians mark this event as pivotal in the decline of the Western Roman Empire.

Various theories have been suggested as to the cause of the empire’s fall but, even today, there is no universal agreement on what those specific factors were. Edward Gibbon has famously argued in his The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire that Christianity played a pivotal role, in that the new religion undermined the social mores of the empire which paganism provided. The theory that Christianity was a root cause in the empire’s fall was debated long before Gibbon, however, as Orosius argued Christianity’s innocence in Rome’s decline as early as 418 A.D. Orosius claimed it was primarily paganism itself and pagan practices which brought about the fall of Rome.

Other influences which have been noted range from the corruption of the governing elite to the ungovernable vastness of the empire to the growing strength of the Germanic tribes and their constant incursions into Rome. The Roman military could no longer safeguard the borders as efficiently as they once had nor could the government as easily collect taxes in the provinces. The arrival of the Visigoths in the empire in the third century A.D. and their subsequent rebellions has also been cited a contributing factor in the decline.

The Western Roman Empire officially ended 4 September 476 A.D., when Emperor Romulus Augustus was deposed by the Germanic King Odoacer (though some historians date the end as 480 A.D. with the death of Julius Nepos). The Eastern Roman Empire continued on as the Byzantine Empire until 1453 A.D., and though known early on as simply `the Roman Empire’, it did not much resemble that entity at all. The Western Roman Empire would become re-invented later as The Holy Roman Empire, but that construct, also, was far removed from the Roman Empire of antiquity and was an `empire’ in name only.

The inventions and innovations which were generated by the Roman Empire profoundly altered the lives of the ancient people and continue to be used in cultures around the world today. Advancements in the construction of roads and buildings, indoor plumbing, aqueducts, and even fast-drying cement were either invented or improved upon by the Romans. The calendar used in the West derives from the one created by Julius Caesar, and the names of the days of the week (in the romance languages) and months of the year also come from Rome.

Apartment complexes (known as `insula), public toilets, locks and keys, newspapers, even socks all were developed by the Romans as were shoes, a postal system (modeled after the Persians), cosmetics, the magnifying glass, and the concept of satire in literature. During the time of the empire, significant developments were also advanced in the fields of medicine, law, religion, government, and warfare. The Romans were adept at borrowing from, and improving upon, those inventions or concepts they found among the indigenous populace of the regions they conquered.

It is therefore difficult to say what is an `original’ Roman invention and what is an innovation on a pre-existing concept, technique, or tool. It can safely be said, however, that the Roman Empire left an enduring legacy which continues to affect the way in which people live even today. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

SHIPPING & RETURNS/REFUNDS: We always ship books domestically (within the USA) via USPS INSURED media mail (“book rate”). Most international orders cost an additional $19.99 to $53.99 for an insured shipment in a heavily padded mailer. There is also a discount program which can cut postage costs by 50% to 75% if you’re buying about half-a-dozen books or more (5 kilos+). Our postage charges are as reasonable as USPS rates allow. ADDITIONAL PURCHASES do receive a VERY LARGE discount, typically about $5 per book (for each additional book after the first) so as to reward you for the economies of combined shipping/insurance costs.

Your purchase will ordinarily be shipped within 48 hours of payment. We package as well as anyone in the business, with lots of protective padding and containers. All of our shipments are fully insured against loss, and our shipping rates include the cost of this coverage (through stamps.com, Shipsaver.com, the USPS, UPS, or Fed-Ex). International tracking is provided free by the USPS for certain countries, other countries are at additional cost.

We do offer U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail, Registered Mail, and Express Mail for both international and domestic shipments, as well United Parcel Service (UPS) and Federal Express (Fed-Ex). Please ask for a rate quotation. Please note for international purchasers we will do everything we can to minimize your liability for VAT and/or duties. But we cannot assume any responsibility or liability for whatever taxes or duties may be levied on your purchase by the country of your residence. If you don’t like the tax and duty schemes your government imposes, please complain to them. We have no ability to influence or moderate your country’s tax/duty schemes.

If upon receipt of the item you are disappointed for any reason whatever, I offer a no questions asked 30-day return policy. Send it back, I will give you a complete refund of the purchase price; 1) less our original shipping/insurance costs, 2) less any non-refundable fees imposed by eBay Please note that though they generally do, eBay may not always refund payment processing fees on returns beyond a 30-day purchase window. So except for shipping costs and any payment processing fees not refunded by eBay, we will refund all proceeds from the sale of a return item. Obviously we have no ability to influence, modify or waive eBay policies.

ABOUT US: Prior to our retirement we used to travel to Eastern Europe and Central Asia several times a year seeking antique gemstones and jewelry from the globe’s most prolific gemstone producing and cutting centers. Most of the items we offer came from acquisitions we made in Eastern Europe, India, and from the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean/Near East) during these years from various institutions and dealers. Much of what we generate on Etsy, Amazon and Ebay goes to support worthy institutions in Europe and Asia connected with Anthropology and Archaeology. Though we have a collection of ancient coins numbering in the tens of thousands, our primary interests are ancient/antique jewelry and gemstones, a reflection of our academic backgrounds.

Though perhaps difficult to find in the USA, in Eastern Europe and Central Asia antique gemstones are commonly dismounted from old, broken settings – the gold reused – the gemstones recut and reset. Before these gorgeous antique gemstones are recut, we try to acquire the best of them in their original, antique, hand-finished state – most of them originally crafted a century or more ago. We believe that the work created by these long-gone master artisans is worth protecting and preserving rather than destroying this heritage of antique gemstones by recutting the original work out of existence. That by preserving their work, in a sense, we are preserving their lives and the legacy they left for modern times. Far better to appreciate their craft than to destroy it with modern cutting.

Not everyone agrees – fully 95% or more of the antique gemstones which come into these marketplaces are recut, and the heritage of the past lost. But if you agree with us that the past is worth protecting, and that past lives and the produce of those lives still matters today, consider buying an antique, hand cut, natural gemstone rather than one of the mass-produced machine cut (often synthetic or “lab produced”) gemstones which dominate the market today. We can set most any antique gemstone you purchase from us in your choice of styles and metals ranging from rings to pendants to earrings and bracelets; in sterling silver, 14kt solid gold, and 14kt gold fill. When you purchase from us, you can count on quick shipping and careful, secure packaging. We would be happy to provide you with a certificate/guarantee of authenticity for any item you purchase from us. There is a $3 fee for mailing under separate cover. I will always respond to every inquiry whether via email or eBay message, so please feel free to write.