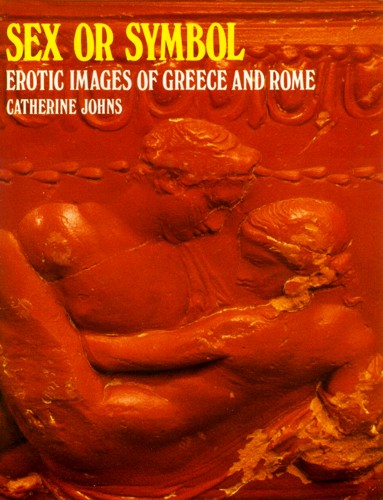

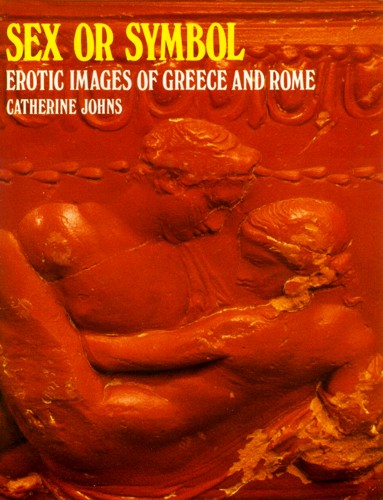

Sex or Symbol: Erotic Images of Greece and Rome by Catherine Johns.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover: 160 pages. Publisher: British Museum; (1982). Size: 11¼ x 9 x 1 inches; 2¼ pounds, In 1786, Englishman Richard Payne Knight, a gentleman-scholar whose avocation was the study of ancient cultures, published “A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus”, an erudite description of phallic votives still used in worship in a small Italian town at that time. In 1808, editor Thomas Mathias termed Knight’s discourse “one of the most unbecoming and indecent treatises which ever disgraced the pen of a man who would be considered a scholar and philosopher”.

Such outraged reactions to attempts to study the erotic art of the classical world continued in the Victorian era, when even sculpted deities, if depicted nude, had to be draped or otherwise rendered “modest” before they could be brought before the eyes of an easily shocked public. All objects from ancient cultures that were shaped or decorated in a manner deemed improper by the severe standards of the cay were categorized as obscene.

Collected by some “shameless” connoisseurs, they were locked away in special collections in the museums where they were stored, and even the scholar who wished to make a serious study of them was forced to beg for permission for a viewing. In “Sex or Symbol”, Catherine Jones casts aside such prejudice to explore the role that sexual imagery played in the ancient world and to examine erotic art and artifacts created by the Greeks and Romans between the sixth century B.C. and the fourth and fifth centuries A.D.

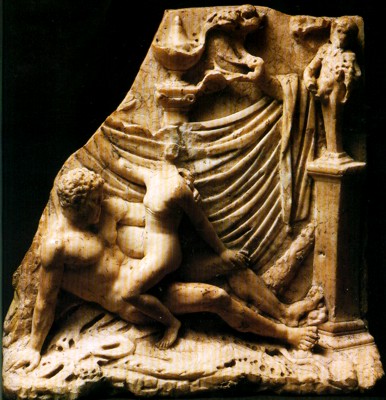

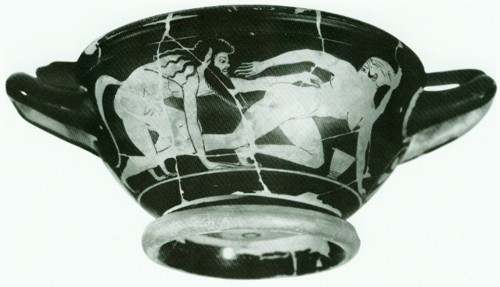

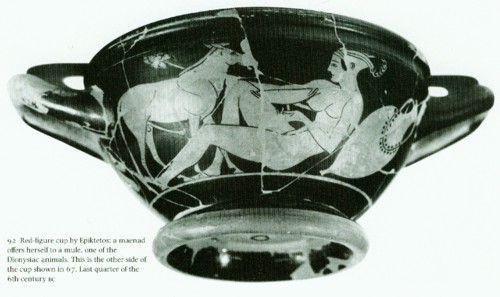

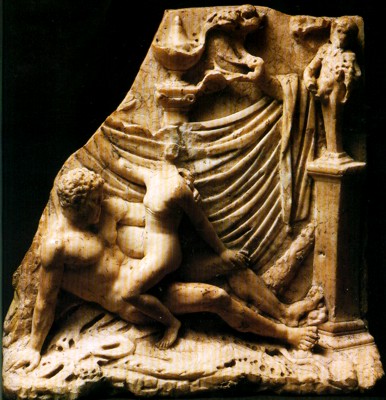

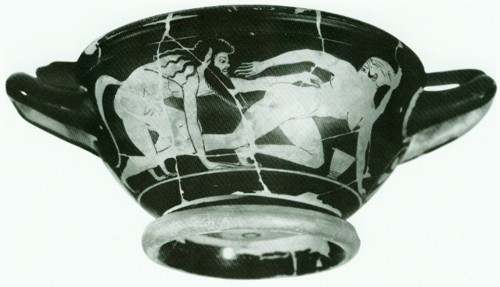

Beginning with a lively account of how prudery has suppressed and distorted the evidence for this important aspect of classical civilization, Johns demonstrates not only how widespread such sexual imagery was, but also how much of this “obscene” art was not primarily erotic to its creators and the contemporaries, but reflected primitive fertility notions, religious concerns, or in some cases, simply lighthearted fun. By examining erotic art within its social, cultural, and religious context, Johns shows why such art has been gravely misunderstood. Her frank and intelligent discussions illuminate not only the ancients’ attitudes toward sex, but also the prejudices and preconceptions of the recent past.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. Clean, very large (12x9 inches) hardcover book with dustjacket. British Museum (1982) 160 pages. Clearly the book has been read, but I'd guess based on the wear, read only once, perhaps twice if by someone with a fairly "light hand". The pages are clean, unblemished, unmarked, and remain very well bound. From the outside the dustjacket evidences only very mild edge and corner shelfwear, no tears, no chips, just some mild abrasive rubbing at the spine head. Overall the dustjacket is in exceptionally good condition. Beneath the dustjacket the covers are clean and without noteworthy blemish, evidencing only (as with the dustjacket) very mild edge and and corner shelfwear. Last we'd mention that the top surface of the closed page edges appear very slightly age-tanned when compared to the bottom surface of the closed page edges. Of course this very slight age tanning is visible only when book is closed, not to individual pages, only to the mass of closed page edges - sometimes referred to as the "page block". Though not new it is a clean, only lightly read book, handsome and presentable, with "lots of miles left under the hood". Except for the fact that it has clearly been read and close scrutiny reveals faint tanning to the top surface of the closed page edges, otherwise it could almost pass as "new" stock from an open-shelf book store (such as Barnes & Noble, or B. Dalton, for example) wherein patrons are permitted to browse open stock, and so otherwise "new" books often show a little handling/shelf/browsing wear due to routine handling and the ordeal of constantly being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #1767.2h.

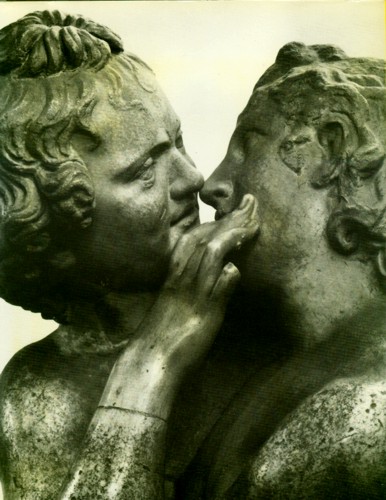

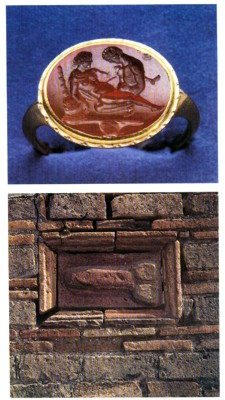

PLEASE SEE IMAGES BELOW FOR SAMPLE PAGES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEW:

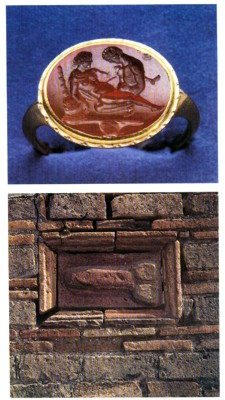

REVIEW: Explores the role that sexual imagery played in the societies of ancient Greece and Rome, with emphasis on the contrast between sexual attitudes in the ancient world and more recent history, when these images were suppressed. Superbly illustrated with 125 black and white and 38 color images of erotic art and artifacts from the Greek and Roman periods.

Catherine Johns is a Curator, Department of Prehistoric and Romano-British Antiquities at the British Museum, and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. Her main professional interests are in Roman jewelry, metalwork, and Arretine and Samian pottery. She is co-author of “The Thetford Treasure”. Contents (Chapter Headings): 1) Collectors and Prudes. 2) Fertility and Religion. 3) The Phallus and the Evil Eye. 4) Dionysus and Drama. 5) Men and beasts. 6) Men and Women. 7) Conclusions.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Entertaining and thoughtful, this book graphically portrays an area of Greek and Roman life that was an embarrassment to the eighteenth and nineteenth century scholars discovering these objects in their classical collections. At a time of sexual prudery such material was viewed as unsuitable for serious study and removed from public display. With 125 black and white and 38 color illustrations, “Sex or Symbol?” shows that while overt sexual representations were common in painting, sculpture, pottery, jewelry and other minor arts, not all the objects that shocked the Victorians had an erotic purpose. Catherine Johns demonstrates that many had a religious and apotropaic function as well as reflecting the classical delight in erotic art for its own sake. They also shed light on the social mores of the time, in particular the wide range of sexual behavior acceptable in classical antiquity.

REVIEW: Investigating overt sexual representations in the art of Greek and Roman life, Johns explains that many of the objects which Victorians found shocking were not all intended to have an erotic purpose. Many had a religious and apotropaic function, and also shed light on social mores of the time. A learned and lively book, Catherine Johns writes with complete knowledge of her subject.

REVIEW: An extremely important and very serious study of an important theme. Explores, without prejudice or prudery, the role that sexual imagery played in Greek and Roman societies. Explores religious concerns, primitive fertility notions and just plain light-hearted fun.

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Catherine Johns begins her book by saying that there is a difference between the modern understanding of sex and the ancient one. Her thinking here is call into question our ideas of "obscene", and she points out that sexual images were used in ancient times as symbols of fertility or symbols to ward off evil. In so doing she provides a pictorial survey of the variety of sexual symbols found in the Greco-Roman world and in this regard she makes her book outstanding. For example, on pages 72 and 73 she shows phallic symbols used as a pendant and as amulets. One amulet shows the combination of three symbols of luck: the phallus, the Crescent, and the hand. Page 110 may show a political satire which pokes fun at Cleopatra. And page 82 shows a beautiful silver dish which depicts Pan dancing. There are 160 some odd illustrations in this book and it is the illustrations which make it worth reading.

REVIEW: Informative, Scholastic, Thought-Provoking, and Lively. Not only is this a splendid resource about an until recently sadly neglected part of ancient studies, erotic artworks, but it is also a historical reference on Victorian scholarship, and a warning about the perils of putting modern culture and preconceptions ahead of the truth found in scientific and historical studies. I could continue singing the praises of this book for several more screens of text. Instead, I will simply recommend that anyone reading this review go on to read this book.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

ANCIENT GREECE: Greece is a country in southeastern Europe, known in Greek as Hellas or Ellada, and consisting of a mainland and an archipelago of islands. Greece is the birthplace of Western philosophy (Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle), literature (Homer and Hesiod), mathematics (Pythagoras and Euclid), history (Herodotus), drama (Sophocles, Euripedes, and Aristophanes), the Olympic Games, and democracy. The concept of an atomic universe was first posited in Greece through the work of Democritus and Leucippus. The process of today's scientific method was first introduced through the work of Thales of Miletus and those who followed him.

The Latin alphabet also comes from Greece, having been introduced to the region by the Phoenicians in the 8th century B.C., and early work in physics and engineering was pioneered by Archimedes, of the Greek colony of Syracuse, among others. Mainland Greece is a large peninsula surrounded on three sides by the Mediterranean Sea (branching into the Ionian Sea in the west and the Aegean Sea in the east) which also comprises the islands known as the Cyclades and the Dodecanese (including Rhodes), the Ionian islands (including Corcyra), the isle of Crete, and the southern peninsula known as the Peloponnese.

The geography of Greece greatly influenced the culture in that, with few natural resources and surrounded by water, the people eventually took to the sea for their livelihood. Mountains cover eighty percent of Greece and only small rivers run through a rocky landscape which, for the most part, provides little encouragement for agriculture. Consequently, the early Greeks colonized neighboring islands and founded settlements along the coast of Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor, modern day Turkey). The Greeks became skilled seafaring people and traders who, possessing an abundance of raw materials for construction in stone, and great skill, built some of the most impressive structures in antiquity. Greece reached the heights in almost every area of human learning.

The designation Hellas derives from Hellen, the son of Deucalion and Pyrrha who feature prominently in Ovid's tale of the Great Flood in his Metamorphoses. The mythical Deucalion (son of the fire-bringing titan Prometheus) was the savior of the human race from the Great Flood, in the same way Noah is presented in the biblical version or Utnapishtim in the Mesopotamian one. Deucalion and Pyrrha repopulate the land once the flood waters have receded by casting stones which become people, the first being Hellen. Contrary to popular opinion, Hellas and Ellada have nothing to do with Helen of Troy from Homer's Iliad.

Ovid, however, did not coin the designation. Thucydides writes, in Book I of his Histories: "I am inclined to think that the very name was not as yet given to the whole country, and in fact did not exist at all before the time of Hellen, the son of Deucalion; the different tribes, of which the Pelasgian was the most widely spread, gave their own names to different districts. But when Hellen and his sons became powerful in Phthiotis, their aid was invoked by other cities, and those who associated with them gradually began to be called Hellenes, though a long time elapsed before the name was prevalent over the whole country. Of this, Homer affords the best evidence; for he, although he lived long after the Trojan War, nowhere uses this name collectively, but confines it to the followers of Achilles from Phthiotis, who were the original Hellenes; when speaking of the entire host, he calls them Danäans, or Argives, or Achaeans."

Greek history is most easily understood by dividing it into time periods. The region was already settled, and agriculture initiated, during the Paleolithic era as evidenced by finds at Petralona and Franchthi caves (two of the oldest human habitations in the world). The Neolithic Age (circa 6000-2900 B.C.) is characterized by permanent settlements (primarily in northern Greece), domestication of animals, and the further development of agriculture. Archaeological finds in northern Greece (Thessaly, Macedonia, and Sesklo, among others) suggest a migration from Anatolia in that the ceramic cups and bowls and figures found there share qualities distinctive to Neolithic finds in Anatolia. These inland settlers were primarily farmers, as northern Greece was more conducive to agriculture than elsewhere in the region, and lived in one-room stone houses with a roof of timber and clay daubing.

The Cycladic Civilization (circa 3200-1100 B.C.) flourished in the islands of the Aegean Sea (including Delos, Naxos and Paros) and provides the earliest evidence of continual human habitation in that region. During the Cycladic Period, houses and temples were built of finished stone and the people made their living through fishing and trade. This period is usually divided into three phases: Early Cycladic, Middle Cycladic, and Late Cycladic with a steady development in art and architecture. The latter two phases overlap and finally merge with the Minoan Civilization, and differences between the periods become indistinguishable.

The Minoan Civilization (2700-1500 B.C.) developed on the island of Crete, and rapidly became the dominant sea power in the region. The term `Minoan' was coined by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, who uncovered the Minoan palace of Knossos in 1900 CE and named the culture for the ancient Cretan king Minos. The name by which the people knew themselves is not known. The Minoan Civilization was thriving, as the Cycladic Civilization seems to have been, long before the accepted modern dates which mark its existence and probably earlier than 6000 B.C.

The Minoans developed a writing system known as Linear A (which has not yet been deciphered) and made advances in ship building, construction, ceramics, the arts and sciences, and warfare. King Minos was credited by ancient historians (Thucydides among them) as being the first person to establish a navy with which he colonized, or conquered, the Cyclades. Archaeological and geological evidence on Crete suggests this civilization fell due to an overuse of the land causing deforestation though, traditionally, it is accepted that they were conquered by the Mycenaeans. The eruption of the volcano on the nearby island of Thera (modern day Santorini) between 1650 and 1550 B.C., and the resulting tsunami, is acknowledged as the final cause for the fall of the Minoans. The isle of Crete was deluged and the cities and villages destroyed. This event has been frequently cited as Plato's inspiration in creating his myth of Atlantis in his dialogues of the Critias and Timaeus.

The Mycenaean Civilization (approximately 1900-1100 B.C.) is commonly acknowledged as the beginning of Greek culture, even though we know almost nothing about the Mycenaeans save what can be determined through archaeological finds and through Homer’s account of their war with Troy as recorded in The Iliad. They are credited with establishing the culture owing primarily to their architectural advances, their development of a writing system (known as Linear B, an early form of Greek descended from the Minoan Linear A), and the establishment, or enhancement of, religious rites. The Mycenaeans appear to have been greatly influenced by the Minoans of Crete in their worship of earth goddesses and sky gods, which, in time, become the classical pantheon of ancient Greece.

The gods and goddesses provided the Greeks with a solid paradigm of the creation of the universe, the world, and human beings. An early myth relates how, in the beginning, there was nothing but chaos in the form of unending waters. From this chaos came the goddess Eurynome who separated the water from the air and began her dance of creation with the serpent Ophion. From their dance, all of creation sprang and Eurynome was, originally, the Great Mother Goddess and Creator of All Things.

By the time Hesiod and Homer were writing (8th century B.C.), this story had changed into the more familiar myth concerning the titans, Zeus' war against them, and the birth of the Olympian Gods with Zeus as their chief. This shift indicates a movement from a matriarchal religion to a patriarchal paradigm. Whichever model was followed, however, the gods clearly interacted regularly with the humans who worshipped them and were a large part of daily life in ancient Greece. Prior to the coming of the Romans, the only road in mainland Greece that was not a cow path was the Sacred Way which ran between the city of Athens and the holy city of Eleusis, birthplace of the Eleusinian Mysteries celebrating the goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone.

By 1100 B.C. the great Mycenaean cities of southwest Greece were abandoned and, some claim, their civilization destroyed by an invasion of Doric Greeks. Archaeological evidence is inconclusive as to what led to the fall of the Mycenaeans. As no written records of this period survive (or have yet to be unearthed) one may only speculate on causes. The tablets of Linear B script found thus far contain only lists of goods bartered in trade or kept in stock. No history of the time has yet emerged. It seems clear, however, that after what is known as the Greek Dark Ages (approximately 1100-800 B.C., so named because of the absence of written documentation) the Greeks further colonized much of Asia Minor, and the islands surrounding mainland Greece and began to make significant cultural advances. Beginning in circa 585 B.C. the first Greek philosopher, Thales, was engaged in what, today, would be recognised as scientific inquiry in the settlement of Miletus on the Asia Minor coast and this region of Ionian colonies would make significant breakthroughs in the fields of philosophy and mathematics.

The Archaic Period (800-500 B.C.) is characterized by the introduction of Republics instead of Monarchies (which, in Athens, moved toward Democratic rule) organised as a single city-state or polis, the institution of laws (Draco’s reforms in Athens), the great Panathenaeic Festival was established, distinctive Greek pottery and Greek sculpture were born, and the first coins minted on the island kingdom of Aegina. This, then, set the stage for the flourishing of the Classical Period of Greece given as 500-400 B.C. or, more precisely, as 480-323 B.C., from the Greek victory at Salamis to the death of Alexander the Great.

This was the Golden Age of Athens, when Pericles initiated the building of the Acropolis and spoke his famous eulogy for the men who died defending Greece at the Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C. Greece reached the heights in almost every area of human learning during this time and the great thinkers and artists of antiquity (Phidias, Plato, Aristophanes, to mention only three) flourished. Leonidas and his 300 Spartans fell at Thermopylae and, the same year (480 B.C.), Themistocles won victory over the superior Persian naval fleet at Salamis leading to the final defeat of the Persians at Plataea in 379 B.C.

Democracy (literally Demos = people and Kratos = power, so power of the people) was established in Athens allowing all male citizens over the age of twenty a voice in government. The Pre-Socratic philosophers, following Thales' lead, initiated what would become the scientific method in exploring natural phenomena. Men like Anixamander, Anaximenes, Pythagoras, Democritus, Xenophanes, and Heraclitus abandoned the theistic model of the universe and strove to uncover the underlying, first cause of life and the universe.

Their successors, among whom were Euclid and Archimedes, continued philosophical inquiry and further established mathematics as a serious discipline. The example of Socrates, and the writings of Plato and Aristotle after him, have influenced western culture and society for over two thousand years. This period also saw advances in architecture and art with a movement away from the ideal to the realistic. Famous works of Greek sculpture such as the Parthenon Marbles and Discobolos (the discus thrower) date from this time and epitomize the artist's interest in depicting human emotion, beauty, and accomplishment realistically, even if those qualities are presented in works featuring immortals.

All of these developments in culture were made possible by the ascent of Athens following her victory over the Persians in 480 B.C. The peace and prosperity which followed the Persian defeat provided the finances and stability for culture to flourish. Athens became the superpower of her day and, with the most powerful navy, was able to demand tribute from other city states and enforce her wishes. Athens formed the Delian League, a defensive alliance whose stated purpose was to deter the Persians from further hostilities.

The city-state of Sparta, however, doubted Athenian sincerity and formed their own association for protection against their enemies, the Peloponnesian League (so named for the Peloponnesus region where Sparta and the others were located). The city-states which sided with Sparta increasingly perceived Athens as a bully and a tyrant, while those cities which sided with Athens viewed Sparta and her allies with growing distrust. The tension between these two parties eventually erupted in what has become known as the Peloponnesian Wars. The first conflict (circa 460-445 B.C.) ended in a truce and continued prosperity for both parties while the second (431-404 B.C.) left Athens in ruins and Sparta, the Victor, bankrupt after her protracted war with Thebes.

This time is generally referred to as the Late Classical Period (circa 400-330 B.C.). The power vacuum left by the fall of these two cities was filled by Philip II of Macedon (382-336 B.C.) after his victory over the Athenian forces and their allies at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 B.C. Philip united the Greek city states under Macedonian rule and, upon his assassination in 336 B.C., his son Alexander assumed the throne.

Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.) carried on his father's plans for a full scale invasion of Persia in retaliation for their invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. As he had almost the whole of Greece under his command, a standing army of considerable size and strength, and a full treasury, Alexander did not need to bother with allies nor with consulting anyone regarding his plan for invasion and so led his army into Egypt, across Asia Minor, through Persia, and finally to India. Tutored in his youth by Plato’s great student Aristotle, Alexander would spread the ideals of Greek civilization through his conquests and, in so doing, transmitted Greek philosophy, culture, language, and art to every region he came in contact with.

In 323 B.C. Alexander died and his vast empire was divided between four of his generals. This initiated what has come to be known to historians as the Hellenistic Age (323-31 B.C.) during which Greek thought and culture became dominant in the various regions under these generals' influence. After a series of struggles between the Diodachi (`the successors' as Alexander's generals came to be known) General Antigonus established the Antigonid Dynasty in Greece which he then lost. It was regained by his grandson, Antigonus II Gonatus, by 276 B.C. who ruled the country from his palace at Macedon.

The Roman Republic became increasingly involved in the affairs of Greece during this time and, in 168 B.C., defeated Macedon at the Battle of Pydna. After this date, Greece steadily came under the influence of Rome. In 146 B.C. the region was designated a Protectorate of Rome and Romans began to emulate Greek fashion, philosophy and, to a certain extent, sensibilities. In 31 B.C. Octavian Caesar annexed the country as a province of Rome following his victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium. Octavian became Augustus Caesar and Greece a part of the Roman Empire. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

ANCIENT GREECE: The Greek Empire had its roots in the different communities which developed in the third Millennium BC, almost 5,000 years ago, the Aegeans, Achaeans, and the Pelasgians. Crete became the center of the more advanced Aegean civilization, known as the Minoans. The Minoan culture dominated the region from about 2,500 BC through 1,600 BC. The volcanic eruption of Thera about 1,600 B.C. not only caused the destruction of the Minoan Empire, it might well have been responsible for a planetary scale of disruption which nearly cost mankind his existence. Around 1,200 B.C., the ten-year Trojan war occurred, and was the subject of the epic poem by Homer, the hero, of course, being Odysseus.

By 1,000 B.C. Greek settlements had transformed themselves into city-states. The Olympic Games began in 776 B.C. In the next several centuries, artwork began to focus on human figures and mythology, and the first coins were soon minted. Greece flourished, and the areas of philosophy, art, and literature reached their zenith. At the height of Greek classical art in the fifth century B.C., the Greek city states employed the finest engravers available to create coins of great artistic merit, as did the Romans who followed. In the ancient Greek city-states, some dies were even signed by a master engraver. The deities of the Greek pantheon were depicted as ideally proportioned humans. The subject of countless movies, the Persian Wars began in 490 B.C, and in 480 B.C. the Persians sacked and ruined Athens. In 461 B.C. the Peloponnesian Wars began between the Athenians and the Spartans.

The greatest Greek military figure, Alexander The Great, in the late fourth century B.C. conquered Egypt and the entire Persian Empire. After Alexander’s death his generals and successors founded the great Hellenistic empires. These successors introduced realistic portraits as a regular feature of their coinage. The true visages of world rulers were recorded for posterity. Many of these rulers of the ancient world are unknown to history except through their coin portraits. The decline of the Greek Empire began shortly after Alexander’s death as the separate Greek kingdoms feuded and fought with one another, crippling the Greek Empire. In 197 B.C. the military forces of Greece fell to the Romans, and the Greek Empire was absorbed by the Romans.

The Sumerians and the Egyptians had developed advanced metalworking techniques long before the Greeks, and so it is natural that the Greeks learned from them. However, as in other forms of art, Greek metalworking artisans borrowed some techniques from the Sumerians and Egyptians and quickly adapted them to their own aesthetic perceptions. Whereas for the Sumerian, Egyptian, and Oriental cultures semi-precious stones were structural elements of their jewelry, in Greece emphasis was placed on worked metal. Gold and silver were the preferred metals (silver actually being much more rare and usually only found as a naturally occurring alloy with gold known as “electrum”). However besides gold and silver, other metals such as copper, lead and iron were used to fashion diadems, necklaces, bracelets, earrings and rings of unrivalled artistry. Ancient Greek jewelers created decorative and artistic themes that far outshone the commonplace repetitive designs of the artifacts of the East.

In antiquity there were ample gold deposits around the Mediterranean, and active gold mines throughout Greece such as those of Siphnos, Thasos or Mount Pangaion. And imported gold was also available to jewelers from Egypt, Spain, the Caucasus and elsewhere. Techniques of gold leaf, wire, hammering, and filigree produced beautiful products. Jewelry decoration depended on the characteristic traits of each period, techniques moving gradually from simple to complex. In Hellenistic times semi-precious stones began to be incorporated into the produce of Greek jewelers, and with the campaigns of Alexander the Great, Greek techniques and styles were disseminated throughout the Mediterranean, including North Africa, the Levant, and into Mesopotamia [AncientGifts].

ANCIENT HELLENIC GREECE: "The Hellenic World" is a term which refers to that period of ancient Greek history between 507 B.C. (the date of the first democracy in Athens) and 323 B.C. (the death of Alexander the Great). This period is also referred to as the age of Classical Greece and should not be confused with The Hellenistic World which designates the period between the death of Alexander and Rome's conquest of Greece (323 - 146 - 31 B.C.). The Hellenic World of ancient Greece consisted of the Greek mainland, Crete, the islands of the Greek archipelago, and the coast of Asia Minor primarily (though mention is made of cities within the interior of Asia Minor and, of course, the colonies in southern Italy). This is the time of the great Golden Age of Greece and, in the popular imagination, resonates as "ancient Greece".

The great law-giver, Solon, having served wisely as Archon of Athens for 22 years, retired from public life and saw the city, almost immediately, fall under the dictatorship of Peisistratus. Though a dictator, Peisistratus understood the wisdom of Solon, carried on his policies and, after his death, his son Hippias continued in this tradition (though still maintaining a dictatorship which favored the aristocracy). After the assassination of his younger brother (inspired, according to Thucydides, by a love affair gone wrong and not, as later thought, politically motivated), however, Hippias became wary of the people of Athens, instituted a rule of terror, and was finally overthrown by the army under Kleomenes I of Sparta and Cleisthenes of Athens.

Cleisthenes reformed the constitution of Athens and established democracy in the city in 507 B.C. He also followed Solon's lead but instituted new laws which decreased the power of the artistocracy, increased the prestige of the common people, and attempted to join the separate tribes of the mountan, the plain, and the shore into one unified people under a new form of government. According to the historian Durant, "The Athenians themselves were exhilarated by this adventure into sovereignty. From that moment they knew the zest of freedom in action, speech, and thought; and from that moment they began to lead all Greece in literature and art, even in statesmanship and war". This foundation of democracy, of a free state comprised of men who "owned the soil that they tilled and who ruled the state that governed them", stabilized Athens and provided the groundwork for the Golden Age.

The Golden Age of Greece, according to the poet Shelley, "is undoubtedly...the most memorable in the history of the world". The list of thinkers, writers, doctors, artists, scientists, statesmen, and warriors of the Hellenic World comprises those who made some of the most important contributions to western civilization: The statesman Solon, the poets Pindar and Sappho, the playwrights Sophocles, Euripedes, Aeschylus and Aristophanes, the orator Lysias, the historians Herodotus and Thucydides, the philosophers Zeno of Elea, Protagoras of Abdera, Empedocles of Acragas, Heraclitus, Xenophanes, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, the writer and general Xenophon, the physician Hippocrates, the sculptor Phidias, the statesman Pericles, the generals Alcibiades and Themistocles, among many other notable names, all lived during this period.

Interestingly, Herodotus considered his own age as lacking in many ways and looked back to a more ancient past for a paradigm of a true greatness. The writer Hesiod, an 8th century B.C. contemporary of Homer, claimed precisely the same thing about the age Herodotus looked back toward and called his own age "wicked, depraved and dissolute" and hoped the future would produce a better breed of man for Greece. Herodotus aside, however, it is generally understood that the Hellenic World was a time of incredible human achievement. Major city-states (and sacred places of pilgrimage) in the Hellenic World were Argos, Athens, Eleusis, Corinth, Delphi, Ithaca, OLYMPIA, Sparta, Thebes, Thrace, and, of course, Mount Olympus, the home of the gods.

The gods played an important part in the lives of the people of the Hellenic World; so much so that one could face the death penalty for questioning - or even allegedly questioning - their existence, as in the case of Protagoras, Socrates, and Alcibiades (the Athenian statesman Critias, sometimes referred to as `the first atheist', only escaped being condemned because he was so powerful at the time). Great works of art and beautiful temples were created for the worship and praise of the various gods and goddesses of the Greeks, such as the Parthenon of Athens, dedicated to the goddess Athena Parthenos (Athena the Virgin) and the Temple of Zeus at OLYMPIA (both works which Phidias contributed to and one, the Temple of Zeus, listed as an Ancient Wonder).

The temple of Demeter at Eleusis was the site of the famous Eleusinian Mysteries, considered the most important rite in ancient Greece. In his works The Iliad and The Odyssey, immensely popular and influential in the Hellenic World, Homer depicted the gods and goddesses as being intimately involved in the lives of the people, and the deities were regularly consulted in domestic matters as well as affairs of state. The famous Oracle at Delphi was considered so important at the time that people from all over the known world would come to Greece to ask advice or favors from the god, and it was considered vital to consult with the supernatural forces before embarking on any military campaign.

Among the famous battles of the Hellenic World that the gods were consulted on were the Battle of Marathon (490 B.C.) the Battles of Thermopylae and Salamis (480 B.C.), Plataea (479 B.C.,) and The Battle of Chaeronea (338 B.C.) where the forces of the Macedonian King Philip II commanded, in part, by his son Alexander, defeated the Greek forces and unified the Greek city-states. After Philip's death, Alexander would go on to conquer the world of his day, becoming Alexander the Great. Through his campaigns he would bring Greek culture, language, and civilization to to the world and, after his death, would leave the legacy which came to be known as the Hellenistic World. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

GREEK COLONIZATION: Ancient Greek Colonization. In the first half of the first Millennium B.C., Greek city-states, most of which were maritime powers, began to look beyond Greece for land and resources, and so they founded colonies across the Mediterranean. Trade contacts were usually the first steps in the colonization process and then, later, once local populations were subdued or included within the colony, cities were established. These could have varying degrees of contact with the homeland, but most became fully independent city-states, sometimes very Greek in character, in other cases culturally closer to the indigenous peoples they neighboured and included within their citizenry.

One of the most important consequences of this process, in broad terms, was that the movement of goods, people, art, and ideas in this period spread the Greek way of life far and wide to Spain, France, Italy, the Adriatic, the Black Sea, and North Africa. In total then, the Greeks established some 500 colonies which involved up to 60,000 Greek citizen colonists, so that by 500 B.C. these new territories would eventually account for 40% of all Greeks in the Hellenic World. The Greeks were great sea-farers, and travelling across the Mediterranean, they were eager to discover new lands and new opportunities.

Even Greek mythology included such tales of exploration as Jason and his search for the Golden Fleece and that greatest of hero travellers Odysseus. First the islands around Greece were colonized, for example the first colony in the Adriatic was Corcyra (Corfu), founded by Corinth in 733 B.C. (traditional date), and then prospectors looked further afield. The first colonists in a general sense were traders and those small groups of individuals who sought to tap into new resources and start a new life away from the increasingly competitive and over-crowded homeland.

Trade centres and free markets (emporia) were the forerunners of colonies proper. Then, from the mid-8th to mid-6th centuries B.C., the Greek city-states (poleis) and individual groups started to expand beyond Greece with more deliberate and longer-term intentions. However, the process of colonization was likely more gradual and organic than ancient sources would suggest. It is also difficult to determine the exact degree of colonization and integration with local populations. Some areas of the Mediterranean saw fully-Greek poleis established, while in other areas there were only trading posts composed of more temporary residents such as merchants and sailors.

The very term 'colonization' infers the domination of indigenous peoples, a feeling of cultural superiority by the colonizers, and a specific cultural homeland which controls and drives the whole process. This was not necessarily the case in the ancient Greek world and, therefore, in this sense, Greek colonization was a very different process from, for example, the policies of certain European powers in the 19th and 20th centuries A.D. It is perhaps here then, a process better described as 'culture contact'. The establishment of colonies across the Mediterranean permitted the export of luxury goods such as fine Greek pottery, wine, oil, metalwork, and textiles, and the extraction of wealth from the land - timber, metals, and agriculture (notably grain, dried fish, and leather), for example - and they often became lucrative trading hubs and a source of slaves.

A founding city (metropolis) might also set up a colony in order to establish a military presence in a particular region and so protect lucrative sea routes. Also, colonies could provide a vital bridge to inland trade opportunities. Some colonies even managed to rival the greatest founding cities; Syracuse, for example, eventually became the largest polis in the entire Greek world. Finally, it is important to note that the Greeks did not have the field to themselves, and rival civilizations also established colonies, especially the Etruscans and Phoenicians, and sometimes, inevitably, warfare broke out between these great powers.

Greek cities were soon attracted by the fertile land, natural resources, and good harbors of a 'New World' - southern Italy and Sicily. The Greek colonists eventually subdued the local population and stamped their identity on the region to such an extent that they called it 'Greater Greece' or Megalē Hellas, and it would become the most 'Greek' of all the colonized territories, both in terms of culture and the urban landscape with Doric temples being the most striking symbol of Hellenization.

Some of the most important poleis in Italy were Cumae (the first Italian colony, founded circa 740 B.C. by Chalcis), Naxos (734 B.C., Chalcis), Sybaris (circa 720 B.C., Achaean/Troezen), Croton (circa 710 B.C., Achaean), Tarentum (706 B.C., Sparta), Rhegium (circa 720 B.C., Chalcis), Elea (circa 540 B.C., Phocaea), Thurri (circa 443 B.C., Athens), and Heraclea (433 B.C., Tarentum). On Sicily the main colonies included Syracuse (733 B.C., founded by Corinth), Gela (688 B.C., Rhodes and Crete), Selinous (circa 630 B.C.), Himera (circa 630 B.C., Messana), and Akragas (circa 580 B.C., Gela).

The geographical location of these new colonies in the centre of the Mediterranean meant they could prosper as trade centres between the major cultures of the time: the Greek, Etruscan, and Phoenician civilizations. And prosper they did, so much so that writers told of the vast riches and extravagant lifestyles to be seen. Empedokles, for example, described the pampered citizens and fine temples of Akragas (Agrigento) in Sicily as follows; "the Akragantinians revel as if they must die tomorrow, and build as if they would live forever". Colonies even established off-shoot colonies and trading posts themselves and, in this way, spread Greek influence further afield, including higher up the Adriatic coast of Italy. Even North Africa saw colonies established, notably Cyrene by Thera in circa 630 B.C., and so it became clear that Greek colonists would not restrict themselves to Magna Graecia.

Greeks created settlements along the Aegean coast of Ionia (or Asia Minor) from the 8th century B.C. Important colonies included Miletos, Ephesos, Smyrna, and Halikarnassos. Athens traditionally claimed to be the first colonizer in the region which was also of great interest to the Lydians and Persians. The area became a hotbed of cultural endeavour, especially in science, mathematics, and philosophy, and produced some of the greatest of Greek minds. Art and architectural styles too, assimilated from the east, began to influence the homeland; such features as palmed column capitals, sphinxes, and expressive 'orientalising' pottery designs would inspire Greek architects and artists to explore entirely new artistic avenues.

The main colonizing polis of southern France was Phocaea which established the important colonies of Alalia and Massalia (circa 600 B.C.). The city also established colonies, or at least established an extensive trade network, in southern Spain. Notable poleis established here were Emporion (by Massalia and with a traditional founding date of 575 B.C. but more likely several decades later) and Rhode. Colonies in Spain were less typically Greek in culture than those in other areas of the Mediterranean, competition with the Phoenicians was fierce, and the region seems always to have been considered, at least according to the Greek literary sources, a distant and remote land by mainland Greeks.

The Black Sea (Euxine Sea to the Greeks) was the last area of Greek colonial expansion, and it was where Ionian poleis, in particular, sought to exploit the rich fishing grounds and fertile land around the Hellespont and Pontos. The most important founding city was Miletos which was credited in antiquity with having a perhaps exaggerated 70 colonies. The most important of these were Kyzikos (founded 675 B.C.), Sinope (circa 631 B.C.), Pantikapaion (circa 600 B.C.), and Olbia (circa 550 B.C.). Megara was another important mother city and founded Chalcedon (circa 685 B.C.), Byzantium (668 B.C.), and Herakleia Pontike (560 B.C.). Eventually, almost the entire Black Sea was enclosed by Greek colonies even if, as elsewhere, warfare, compromises, inter-marriages, and diplomacy had to be used with indigenous peoples in order to ensure the colonies' survival.

In the late 6th century B.C. particularly, the colonies provided tribute and arms to the Persian Empire and received protection in return. After Xerxes' failed invasion of Greece in 480 and 479 B.C., the Persians withdrew their interest in the area which allowed the larger poleis like Herakleia Pontike and Sinope to increase their own power through the conquest of local populations and smaller neighbouring poleis. The resulting prosperity also allowed Herakleia to found colonies of her own in the 420s B.C. at such sites as Chersonesos in the Crimea. From the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 431 B.C., Athens took an interest in the region, sending colonists and establishing garrisons. An Athenian physical presence was short-lived, but longer-lasting was an Athenian influence on culture (especially sculpture) and trade (especially of Black Sea grain). With the eventual withdrawal of Athens, the Greek colonies were left to fend for themselves and meet alone the threat from neighbouring powers such as the Royal Scythians and, ultimately, Macedon and Philip II.

Most colonies were built on the political model of the Greek polis, but types of government included those seen across Greece itself - oligarchy, tyranny, and even democracy - and they could be quite different from the system in the founder, parent city. A strong Greek cultural identity was also maintained via the adoption of founding myths and such wide-spread and quintessentially Greek features of daily life as language, food, education, religion, sport and the gymnasium, theatre with its distinctive Greek tragedy and comedy plays, art, architecture, philosophy, and science. So much so that a Greek city in Italy or Ionia could, at least on the surface, look and behave very much like any other city in Greece. Trade greatly facilitated the establishment of a common 'Greek' way of life. Such goods as wine, olives, wood, and pottery were exported and imported between poleis.

Even artists and architects themselves relocated and set up workshops away from their home polis, so that temples, sculpture, and ceramics became recognisably Greek across the Mediterranean. Colonies did establish their own regional identities, of course, especially as they very often included indigenous people with their own particular customs, so that each region of colonies had their own idiosyncrasies and variations. In addition, frequent changes in the qualifications to become a citizen and forced resettlement of populations meant colonies were often more culturally diverse and politically unstable than in Greece itself and civil wars thus had a higher frequency. Nevertheless, some colonies did extraordinarily well, and many eventually outdid the founding Greek superpowers.

Colonies often formed alliances with like-minded neighbouring poleis. There were, conversely, also conflicts between colonies as they established themselves as powerful and fully independent poleis, in no way controlled by their founding city-state. Syracuse in Sicily was a typical example of a larger polis which constantly sought to expand its territory and create an empire of its own. Colonies which went on to subsequently establish colonies of their own and who minted their own coinage only reinforced their cultural and political independence.

Although colonies could be fiercely independent, they were at the same time expected to be active members of the wider Greek world. This could be manifested in the supply of soldiers, ships, and money for Panhellenic conflicts such as those against Persia and the Peloponnesian War, the sending of athletes to the great sporting games at places like OLYMPIA and Nemea, the setting up of military victory monuments at Delphi, the guarantee of safe passage to foreign travellers through their territory, or the export and import of intellectual and artistic ideas such as the works of Pythagoras or centres of study like Plato's academy which attracted scholars from across the Greek world.

Then, in times of trouble, colonies could also be helped out by their founding polis and allies, even if this might only be a pretext for the imperial ambitions of the larger Greek states. A classic example of this would be Athens' Sicilian Expedition in 415 B.C., officially at least, launched to aid the colony of Segesta. There was also the physical movement of travellers within the Greek world which is attested by evidence such as literature and drama, dedications left by pilgrims at sacred sites like Epidaurus, and participation in important annual religious festivals such as the Dionysia of Athens.

Different colonies had obviously different characteristics, but the collective effect of these habits just mentioned effectively ensured that a vast area of the Mediterranean acquired enough common characteristics to be aptly described as the Greek World. Further, the effect was long-lasting for, even today, one can still see common aspects of culture shared by the citizens of southern France, Italy, and Greece. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM OF ATHENS: The National Archaeological Museum of Athens can effortlessly lay claim to being one of the very greatest museums in the world. It can do that because it is literally jam-packed with most of the most famous art objects from ancient Greece, so much so, a first-time visit here is a strangely familiar experience. From the towering bronze Poseidon to the shimmering gold mask of Agamemnon, the antiquities on display here provide the staple images of ancient Greece; adorning guidebooks, calendars, and travel agents’ Windows around the world.

Familiar many of these works might be but the wow-factor is certainly no less for it. Wandering around the museum one has a constant urge to re-trace one’s steps for just one more glimpse of a stunning piece before moving on. As everything is arranged in chronological order, your tour of the museum gives you a perfect vision of the evolution of Greek art and there is even an Egyptian section as an added bonus if your senses have not already been blown away by everything on the ground floor.

Located an easy 10 minute walk from Omonia metro stop, the museum is itself an impressive nod to classical architecture and is a listed building. Four massive statues of Greek gods peer down at you from the roof as if daring you not to be awestruck in the first few minutes of your visit. Once you’ve got your ticket, got rid of any large bags in the cloakroom (obligatory), and picked up your free map, you are immediately presented with the grinning mask of Agamemnon before you have even got through the first doorway.

Don’t be drawn in here though by all that flashing gold but take a side-step to the room on your immediate right as here are the artefacts from the Cyclades which should come first in your odyssey through the Greek world. Pieces to look out for are the distinctive minimalist figures sculpted in marble, especially the two musical figures, one playing a harp and another an aulos (pipes), the earliest known depictions from the Greek world. Once you have finished with the Cyclades you will find yourself back where you started and that famous mask.

After you make it around the first cabinet you will be presented by an astonishing array of Mycenaean gold. On the left, on the right, and in the middle are glass cases stuffed with masks, jewellery, weapons, and cups all shimmering in the museum spotlights. Then, when you finally pull yourself away and move along, you are presented with yet more cabinets left, right, and centre, again, gold flashing everywhere in every conceivable shape from rosettes to octopuses. It is right about now that you start thinking you have already got your money’s worth and how can the museum possibly top such splendor?

Then you turn a corner and are presented with a massive stone kouros statue – another wow moment. The male figure presented in this way was the beginning of Greek art’s successful attempt to break the conventions of Egyptian statue figures. The arms are rigid by the sides and bring a tension to the upper body but the left leg steps forward slightly hinting at captured movement. As you walk through this section the figures become more and more life-like and dynamic as Greek sculptors became ever more daring in their efforts to render in stone the supple movement of human muscle.

The best is yet to come though and the first hint is the two-metre high bronze statue of Poseidon (or maybe Zeus) rescued from the sea near Artemision. With his arms outstretched and legs braced apart he seems about to launch a trident or thunderbolt and he totally dominates the view down the hall. Bronze was the material of choice for Greek sculptors and two more outstanding examples are the Antikythera Youth (another find from the sea) and the child jockey riding a massive horse that is captured in full gallop, so much so, it seems about to take off from its pedestal at any second.

In amongst all these star pieces there are other, equally fine, marble statues of Greek gods and heroes and one of the greatest collections of funeral sculpture anywhere. As in each room, all the pieces are well-presented and each has a small info panel in Greek and English. Given their own space and unconfined by glass or barriers, the visitor can certainly get up close and personal with these 2,500 year old pieces. The sculpture continues through the Hellenistic and into the Roman period with some very familiar Roman emperors, most famously the bronze statue of a youthful Augustus.

This is the moment when probably most visitors are feeling a bit of art-fatigue so it might be worth a break in the coffee bar in the basement where you can also buy light snacks. There is a little outside courtyard too where you can sip a Greek coffee sitting amongst ancient sculptures not deemed top drawer enough to make it into the museum proper. It is well worth pushing on though as the museum has a stupendous pottery section. As you bought your ticket you probably caught a glimpse of the huge geometric vase from the Dipylon on your left and now is the time to take a closer look.

Used for funeral purposes you can see at eye-level black stick figures in mourning and burying one of their own. The amphora is perhaps the most famous example of geometric pottery design and another one of those star pieces any museum curator in the world would sell their mother for. Then there are case after case of back-figure pottery in all shapes and sizes from miniature votive vessels to huge kraters used for mixing wine and water. Next comes red-figure pottery and both of these styles are one of the most important sources of information on Greek cultural practices and mythology.

Three more must-see sections are those on Thera, Egypt, and the Stathatos Collection. The first, from the Bronze Age site on Santorini, has the super-famous boxing boys fresco and three sides of a room where the fresco shows scenes of spring; there are also pottery vessels and a bed miraculously preserved in the ash following the eruption of the volcano on the island. The Egyptian section is, understandably, more modest in scope than the rest of the museum but there are still enough sarcophagi, amulets, jewellery pieces, reconstruction models, and even a mummy or two, to be of interest.

Finally, the Stathatos Collection has almost a thousand exhibits and is particularly big on jewelry, including examples from the Byzantine period. Having seen all those wonders you might fancy a keep-sake of your own and the museum shop next to the cafe has a good stock of Greek-inspired jewellery, museum-grade copies of sculpture and reliefs to suit all wallets (you can even buy life-size bronze statues, although quite how you’d get that one home…), replica coins, posters, mugs and all the other stuff anyone might want as a souvenir.

There is a small collection of books on different aspects of the ancient Greeks (including plenty for children) and even some guides to other sites such as Dodona and Delphi, mostly in English or Greek. In summary, then, even if you have visited many of the great Greek sites like the Parthenon, Knossos, and Mycenae, you cannot miss this museum for the full picture of the ancient Greeks. It really is an embarrassment of riches and one is left feeling a little sorry for some of the other Greek cities which have lost out on displaying these treasures.

It is one of those museums you really should visit twice, once with your camera and once again without or just so that, on your second visit, you can keep a lid on your excitement a little better each time you see a world-famous art object around the next corner. As said above, you can get close to the art but the down-side of that is large tour groups can easily clog up the rooms so it is best to go early morning or late in the day, or even better, out of season when you pretty much get entire rooms to yourself. A wonderful, wonderful museum. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

CONTEMPORARY EXCAVATIONS OF AN UNKNOWN ANCIENT GREEK CITY: Archaeologists from the University of Gothenburg and the University of Bournemouth are exploring the remains of a long-overlooked ancient city in northern Greece. The ruins, which are scattered atop a hill, were known to scholars, but were regarded as belonging to a small settlement. However, after just one season, the team has found extensive walls that enclose some 100 acres.

“I think it is incredibly big,” project leader Robin Rönnlund told The Local Sweden. “It's something thought to be a small village that turns out to be a city, with a structured network of streets and a square.” The team has found coins dating back to 500 B.C., as well as other artifacts that indicate the city flourished from the fourth to third centuries B.C., before it was abandoned when Romans conquered the region. [Archaeological Institue of America].

THE ANCIENT GREEK ANTIKYTHERA SHIPWRECK: According to a report in The Guardian, pieces of at least seven different bronze sculptures have been recovered at the site of the Antikythera shipwreck, made famous by the discovery of the Antikythera mechanism in 1901. Brendan Foley of Lund University said the pieces were found among large boulders that may have tumbled over the wreckage during an earthquake in the fourth century A.D. with an underwater metal detector. Recovering any possible additional statue pieces will require moving the boulders, some of which weigh several tons, or cracking them open.

The team also discovered a slab of red marble, a silver tankard, pieces of wood from the ship’s frame, and a human bone. A bronze disc about the size of the geared wheels in the Antikythera mechanism was also found this year. Preliminary X-rays of the object revealed an image of a bull, but no cogs, so it may have been a decorative item. Investigation of the deepwater site will continue next year. “We’re down in the hold of the ship now, so all the other things that would have been carried should be down there as well,” Foley said. [Archaeological Institute of America].

: We always ship books domestically (within the USA) via USPS INSURED media mail (“book rate”). There is also a discount program which can cut postage costs by 50% to 75% if you’re buying about half-a-dozen books or more (5 kilos+). Rates vary a bit from country to country, and not all books will fit into a USPS global priority mail flat rate envelope. This book does barely fit into a flat rate envelope, but with NO padding, it will be highly susceptible to damage. We strongly recommend first class airmail for international shipments, which although more expensive, would allow us to properly protect the book. Our postage charges are as reasonable as USPS rates allow.

ADDITIONAL PURCHASES do receive a VERY LARGE Your purchase will ordinarily be shipped within 48 hours of payment. We package as well as anyone in the business, with lots of protective padding and containers.

International tracking is provided free by the USPS for certain countries, other countries are at additional cost. We do offer U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail, Registered Mail, and Express Mail for both international and domestic shipments, as well United Parcel Service (UPS) and Federal Express (Fed-Ex). Please ask for a rate quotation. Please note for international purchasers we will do everything we can to minimize your liability for VAT and/or duties. But we cannot assume any responsibility or liability for whatever taxes or duties may be levied on your purchase by the country of your residence. If you don’t like the tax and duty schemes your government imposes, please complain to them. We have no ability to influence or moderate your country’s tax/duty schemes.

If upon receipt of the item you are disappointed for any reason whatever, I offer a no questions asked 30-day return policy. Please note that though they generally do, eBay may not always refund payment processing fees on returns beyond a 30-day purchase window. Obviously we have no ability to influence, modify or waive eBay policies.

ABOUT US: Prior to our retirement we used to travel to Eastern Europe and Central Asia several times a year seeking antique gemstones and jewelry from the globe’s most prolific gemstone producing and cutting centers. Most of the items we offer came from acquisitions we made in Eastern Europe, India, and from the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean/Near East) during these years from various institutions and dealers. Much of what we generate on Etsy, Amazon and Ebay goes to support worthy institutions in Europe and Asia connected with Anthropology and Archaeology. Though we have a collection of ancient coins numbering in the tens of thousands, our primary interests are ancient/antique jewelry and gemstones, a reflection of our academic backgrounds.

Though perhaps difficult to find in the USA, in Eastern Europe and Central Asia antique gemstones are commonly dismounted from old, broken settings – the gold reused – the gemstones recut and reset. Before these gorgeous antique gemstones are recut, we try to acquire the best of them in their original, antique, hand-finished state – most of them originally crafted a century or more ago. We believe that the work created by these long-gone master artisans is worth protecting and preserving rather than destroying this heritage of antique gemstones by recutting the original work out of existence. That by preserving their work, in a sense, we are preserving their lives and the legacy they left for modern times. Far better to appreciate their craft than to destroy it with modern cutting.

Not everyone agrees – fully 95% or more of the antique gemstones which come into these marketplaces are recut, and the heritage of the past lost. But if you agree with us that the past is worth protecting, and that past lives and the produce of those lives still matters today, consider buying an antique, hand cut, natural gemstone rather than one of the mass-produced machine cut (often synthetic or “lab produced”) gemstones which dominate the market today. We can set most any antique gemstone you purchase from us in your choice of styles and metals ranging from rings to pendants to earrings and bracelets; in sterling silver, 14kt solid gold, and 14kt gold fill. We would be happy to provide you with a certificate/guarantee of authenticity for any item you purchase from us. I will always respond to every inquiry whether via email or eBay message, so please feel free to write.