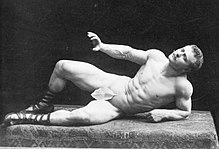

From the collection of the renowned 19th century American sculptor William Ordway Partridge, a friend of many of the leading performers of the late 19th century, a rare original June 1893 program clip for legendary strong man Eugen Sandow, "The Man of Supernatural Strength," sharing the bill with Henry E. Dixey in Adonis. Clipped from a larger program and laid down to an eleven and a half by nine inch Victorian album page. Light wear otherwise good. See Eugen Sandow's extraordinary biography below.

Combined shipping discounts for multiple purchases. Inquiries always welcome. Please visit my other eBay items for more early theatre, opera, film and historical autographs, photographs and programs and great actor and actress cabinet photos and CDV's.

From Wikipedia:

Eugen Sandow (born Friedrich Wilhelm Müller, German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈvɪlhɛlm ˈmʏlɐ]; 2 April 1867 – 14 October 1925) was a Prussian bodybuilder and showman.[2] Born in Königsberg, Sandow became interested in bodybuilding at the age of ten during a visit to Italy.[3] After a spell in the circus, Sandow studied under strongman Ludwig Durlacher in the late 1880s.[3] On Durlacher's recommendation,[3] he began entering strongman competitions, performing in matches against leading figures in the sport such as Charles Sampson, Frank Bienkowski, and Henry McCann.[2] In 1901 he organised what is believed to be the world's first major body building competition. Set in London's Royal Albert Hall, Sandow judged the event alongside author Arthur Conan Doyle.

Sandow was born to a family of Jewish origin in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad), on 2 April 1867. His father was German, while his mother was of Russian descent.[4] Although his parents were born Jewish, the family were Lutherans and wanted him to become a Lutheran minister.[5]: 6 [6][7] He left Prussia in 1885 to avoid military service and traveled throughout Europe, becoming a circus athlete and adopting Eugen Sandow as his stage name, adapting and Germanizing his Russian mother's maiden name, Sandov.

In Brussels he visited the gym of a fellow strongman, Ludwig Durlacher, better known under his stage name "Professor Attila".[8] Durlacher recognized Sandow's potential, mentored him, and in 1889 encouraged him to travel to London and take part in a strongmen competition. Sandow handily beat the reigning champion and won instant fame and recognition for his strength. This launched him on his career as an athletic superstar. Soon he was receiving requests from all over Britain for performances. For the next four years, Sandow refined his technique and crafted it into popular entertainment with posing and incredible feats of strength.

Career

Florenz Ziegfeld wanted to display Sandow at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago,[2] but Ziegfeld knew that Maurice Grau had Sandow under a contract.[9] Grau wanted $1,000 a week. Ziegfeld could not guarantee that much but agreed to pay 10 percent of the gross receipts.[9]

Ziegfeld found that the audience was more fascinated by Sandow's bulging muscles than by the amount of weight he was lifting, so Ziegfeld had Sandow move in poses which he dubbed "muscle display performances" ... and the legendary strongman added these displays in addition to performing his feats of strength with barbells. He added chain-around-the-chest breaking and other colorful displays to Sandow's routine, and Sandow quickly became Ziegfeld's first star.[citation needed]

In 1894, Sandow was featured in a short film series by the Edison Studios.[10] The film was of only part of his act and featured him flexing his muscles rather than performing any feats of physical strength.

While the content of the film reflected the audience's focus on his appearance, it made use of the unique capacities of the new medium. Film theorists have attributed the appeal being the striking image of a detailed image moving in synchrony, much like the example of the Lumière brothers' Repas de bébé where audiences were reportedly more impressed by the movement of trees swaying in the background than the events taking place in the foreground. In 1894, Sandow also appeared in a short Kinetoscope film that became the part of the first commercial motion picture exhibition in history.[citation needed]

In April of that same year Sandow gave one of his "muscle display performances" at the 1894 California Mid-Winter International Exposition in Golden Gate Park at the "Vienna Prater" Theater.[11]

While he was on tour in the United States, Sandow made a brief return to England to marry Blanche Brooks, a girl from Manchester. However, due to stress and ill health he returned permanently to recuperate.[citation needed]

He was soon back on his feet, and opened the first of his Institutes of Physical Culture, where he taught methods of exercise, dietary habits and weight training. His ideas on physical fitness were novel at the time and had a tremendous impact. The Sandow Institute was an early gymnasium that was open to the public for exercise.[12] In 1898 he also founded a monthly periodical, originally titled Physical Culture and subsequently renamed Sandow's Magazine of Physical Culture that was dedicated to all aspects of physical culture. This was accompanied by a series of books published between 1897 and 1904 – the last of which coined the term 'bodybuilding' in the title (as "body-building").[13]

He worked hard at improving exercise equipment, and had invented various devices such as rubber strands for stretching and spring-grip dumbbells to exercise the wrists. In 1900 William Bankier wrote Ideal Physical Culture in which he challenged Sandow to a contest in weightlifting, wrestling, running and jumping. When Sandow did not accept his challenge Bankier called him a coward, a charlatan and a liar.[5]: 171

In 1901, Sandow organized the world's first major bodybuilding competition in London's Royal Albert Hall. The venue was so full that people were turned away from the door. The three judges presiding over the contest were Sir Charles Lawes the sculptor, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle the author, and Sandow himself.[14]

In 1902, Sandow was defeated by Katie Brumbach in a weightlifting contest in New York City. Brumbach lifted a weight of 300 pounds over her head, which Sandow managed to lift only to his chest. After this victory, Brumbach adopted the stage name "Sandwina" as a feminine derivative of Sandow.[15][16]

In 1906, Sandow was able to buy the lease of 161 (formerly 61) Holland Park Avenue, thanks to a generous gift from an Indian businessman, Sir Dhunjibhoy Bomanji, whose health had improved dramatically after he had adopted Sandow's regime. This grand four-storey end-of-terrace house – which was named Dhunjibhoy House after his benefactor – was his home for 19 years.[17][18][19]

He travelled around the world on tours to countries as varied as South Africa, India, Japan, Australia, New Zealand. At his own expense, from 1909 he provided training for would-be recruits to the Territorial Army, to bring them up to entrance fitness standards, and did the same for volunteers for active service in World War I.[20]

He was even designated special instructor in physical culture to King George V, who had followed his teachings, in 1911.[21]

The Grecian Ideal

Sandow's resemblance to the physiques found on classical Greek and Roman sculpture was no accident, as he measured the statues in museums and helped to develop "The Grecian Ideal" as a formula for the "perfect physique". Sandow built his physique to the exact proportions of his Grecian Ideal, and is considered the father of modern bodybuilding, as one of the first athletes to intentionally develop his musculature to predetermined dimensions. In his books Strength and How to Obtain It[22] and Sandow's System of Physical Training, Sandow laid out specific prescriptions of weights and repetitions in order to achieve his ideal proportions.

Personal life

Sandow married Blanche Brooks in 1896.[21] They had two daughters, Helen and Lorraine.[23][24]

Influence on yoga

Sandow was acclaimed on his 1905 visit to India, at which time he was already a "cultural hero" in the country at a time of strong nationalistic feeling. The scholar Joseph Alter suggests that Sandow was the person who had the most influence on modern yoga as exercise, which absorbed a variety of exercise routines from physical culture in the early 20th century.[25][26]

Death

Sandow died at his home in Kensington, London, on 14 October 1925 of what newspapers announced as a brain hemorrhage at age 58.[1][27] It was allegedly brought on after straining himself, without assistance, to lift his car out of a ditch after a road accident two or three years earlier.[28] However, without an autopsy, his death was certified as due to aortic aneurysm.[28]

Sandow was buried in an unmarked grave in Putney Vale Cemetery at the request of his wife, Blanche. He was unfaithful to his wife later in marriage, and she refused to mark his grave.[28] In 2002, a gravestone and black marble plaque was added by Sandow admirer and author Thomas Manly.[citation needed] The inscription (in gold letters) read "Eugen Sandow, 1867–1925, the Father of Bodybuilding". In 2008, the grave was purchased by Chris Davies, Sandow's great-grandson.[29] Manly's items were replaced for the anniversary of Sandow's birth that year and a new monument, a one-and-a-half-ton natural pink sandstone monolith, was put in its place. The stone, simply inscribed "SANDOW 1867-1925", is a reference to the ancient Greek funerary monuments called steles.

Legacy

Sandow was befriended by King George V, Thomas Edison, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and classical pianist Martinus Sieveking. He was portrayed by the actor Nat Pendleton in the Academy Award-winning film The Great Ziegfeld (1936).

"Physical Strength and How to Obtain It by Eugene [sic] Sandow" is mentioned as being on the bookshelves of Leopold Bloom in James Joyce's 1922 novel Ulysses.

As recognition of his contribution to the sport of bodybuilding, a bronze statue of Sandow sculpted by Frederick Pomeroy has been presented to the winner of the Mr. Olympia contest, a major professional bodybuilding competition sponsored by the International Federation of Bodybuilders, since 1977.[32] This statue is simply known as "The Sandow".

In 2013, Eugen Sandow was portrayed by the Canadian bodybuilder Dave Simard in the film Louis Cyr.

Sandows (London) cold brew coffee is named after him.[33]

English Heritage put up a blue plaque on his house at 161 Holland Park Avenue in west London in 2009;[34] it describes him as a "Body-Builder and Promoter of Physical Culture".

Sandow (or a character modeled and named after him) appears in the eleventh episode of Season 3 of The Venture Bros., in which he is voiced by Paul Boocock and appears alongside other contemporary entertainers.

William Ordway Partridge (April 11, 1861 – May 22, 1930) was an American sculptor, teacher and author. Among his best-known works are the Shakespeare Monument in Chicago, the equestrian statue of General Grant in Brooklyn, the Pietà at St. Patrick's Cathedral, Manhattan, and the Pocahontas statue in Jamestown, Virginia.

He was born in Paris, the younger son of George Sidney Partridge, Jr. and Helen Derby Catlin.[2] His father was the Paris representative for the New York City department store A.T. Stewart.[2] His mother was a cousin of the painter George Catlin.[2] His brother, Sidney Catlin Partridge, became a bishop of the Episcopal Church.[2]

Education

Partridge's family returned to New York City in 1868, and enrolled him in Cheshire Academy in Connecticut, followed by Adelphi Academy in Brooklyn.[2] He entered Columbia University in autumn 1881, but had to withdraw because of poor health.[1] He traveled to Europe in 1882,[2] and studied in Florence in the studio of Fortunato Galli,[1] where he became friends with the young Bernard Berenson.[3] Although he never formally enrolled at the Ecole de Beaux-Arts, he audited classes there in autumn 1883, and studied briefly in the Paris studio of sculptor Antonin Mercié.[1] He returned to New York City in Spring 1884, and enrolled in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.[1] He appeared in a New York City production of David Copperfield,[2] and moved to Boston, where he supported himself by giving dramatic readings of Shakespeare and the Romantic poets.[1] He continued to sculpt, and received encouragement in this from his cousin, the sculptor John Rogers.[1]

In 1887, he married Augusta Merriam, a wealthy widow from Milton, Massachusetts, who was 15 years older.[1] They traveled to Europe that year, where he studied briefly in the Paris studio of painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau. There he formed a close friendship with the neo-Gothic architect Ralph Adams Cram.[4] The couple moved to Rome, where he studied in the studio of Polish sculptor Pio Welonski.[1] They returned to Milton, Massachusetts in 1889, where he established his own studio.[1]

Sculptures

Partridge created two larger-than-life bronze statues of Alexander Hamilton, executed 15 years apart. The first was commissioned by the Hamilton Club of Brooklyn, installed in front of the club's headquarters in Brooklyn Heights, and dedicated on October 4, 1893.[5] For months before and after that dedication, Partridge's full-size plaster model of Hamilton was on exhibition at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[5] The bronze statue stood in Brooklyn until 1936, when it was relocated to The Grange, Hamilton's country house in northern Manhattan.[5] The second Hamilton statue was commissioned by the Alumni Association of Columbia College [now University].[6] It was installed on campus in front of Hamilton Hall, and dedicated on May 27, 1908.[6] Both Hamilton statues stand in northern Manhattan, less than 1.5 mi (2.4 km) apart.

In 1890, Partridge won a national competition to create a statue of William Shakespeare for Chicago, Illinois.[1] He returned to Paris, where he set up a studio to work on the project.[1] He exhibited his full-size plaster model of Shakespeare at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago,[1] along with nine other works.[a] His bronze Shakespeare was installed in Lincoln Park the following spring, and dedicated on April 23, 1894, the Bard's 330th birthday.[8] Partridge wrote a sonnet for its dedication.[b]

The Equestrian Statue of General Ulysses S. Grant (1895-1896) was Partridge's most colossal work. Commissioned by the Union League Club of Brooklyn, it was installed in the center of Bedford Avenue, in front of the Club's headquarters, and dedicated on April 27, 1896.[10] The bronze horse and rider are approximately 12 ft (3.7 m) in height, and stand upon a granite pedestal approximately 15 ft (4.6 m) in height.[10]

A bequest from Englishman James Smithson (c.1765-1829) funded the creation of the Smithsonian Institution. Partridge was commissioned in 1896 to create a bronze memorial tablet commemorating that bequest for Smithson's gravesite in Genoa, Italy.[c] He based his relief portrait of Smithson on an 1817 relief portrait taken from life by Pierre-Joseph Tiolier (formerly attributed to Antonio Canova).[11] Partridge initially made two casts of the bronze tablet, one for the gravesite and the other for the nearby Protestant Chapel of the Holy Spirit.[12] He made a third bronze cast in 1898 for Smithson's alma mater, Pembrook College, University of Oxford. The gravesite's bronze tablet was stolen, and the chapel's bronze tablet was used to make a marble copy, that was installed at the gravesite in 1900.[12] Upon learning that the Genoa cemetery was to be destroyed for the expansion of an adjacent quarry, Alexander Graham Bell, a member of the Smithsonian's Board of Regents, proposed that Smithson's remains be brought to the United States.[13] In 1904, Smithson's remains and grave monument were relocated to the Crypt of the Smithsonian's Castle Building in Washington, D.C.[13] The 1900 marble copy of Partridge's tablet was part of that move.[12] The Chapel of the Holy Spirit was destroyed by Allied bombing during World War II. A marble copy of Partridge's tablet was carved in 1963, and stands today at the site of the chapel.[12]

Partridge's most famous religious work is the larger-than-life Pietà he created for St. Patrick's Cathedral, Manhattan. The dead Christ is collapsed before a seated Mary, who cradles his face with her hand. Critic Robert Burns Wilson wrote a sensitive appreciation of the work.[d] Carved from white Carrara marble, Pietà is located in the Ambulatory behind the High Altar.[15]

The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities commissioned Partridge to create a larger-than-life bronze statue of Pocahontas, the Native American princess, for the 1907 Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia.[16] The exposition commemorated the 300th anniversary of the founding of the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. Pocahontus stood in front of the Administration Building for the exposition, and APVA later loaned the statue to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[16] APVA donated the statue to Jamestown, where it was re-dedicated on June 3, 1922.[16] Queen Elizabeth II visited Jamestown in 1957 for the 350th anniversary, and was charmed by the statue. Her reaction inspired a posthumous replica to be cast, which was presented by the Governor of Virginia as a gift to the British people. Dedicated on October 5, 1958, the bronze replica was installed outside St. George's, Gravesend, the English church in which Pocahontas had been interred in 1617.[17]

Teacher

Partridge lectured at the National Social Science Association, the Concord School of Philosophy, and the Brooklyn Institute.[2] From 1897 to 1903, he lectured at what is now George Washington University, in Washington, D.C.,[2] and went on to lecture at Stanford University in California.

He wrote a manual on sculpting: Technique of Sculpture (1895).

Partridge's studio was at 15 West 38th Street, Manhattan. Lee Lawrie was among his studio assistants.

Personal

Partridge and Augusta Merriam had a daughter together, also named Augusta (d. 1916). The couple divorced in 1904.[1]

On June 14, 1905 he married the poet Margaret Ridgely Schott.[18]: p. xxx They had a daughter together, also named Margaret.[e]

Partridge died in Manhattan, New York City, on May 22, 1930.