Legends of the Egyptian Gods: Hieroglyphic Texts and Translations by E.A. Wallis Budge.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

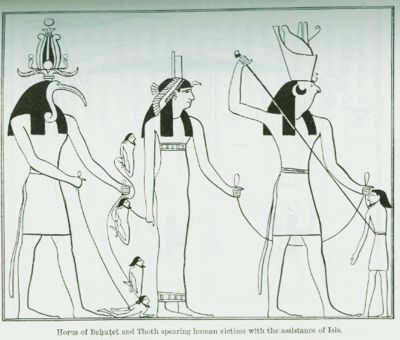

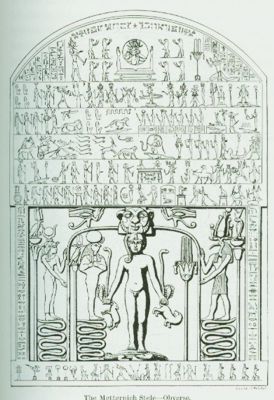

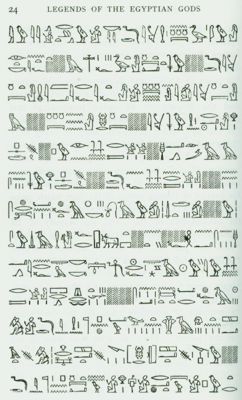

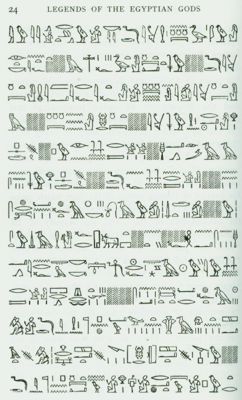

DESCRIPTION: Softcover: 248 pages. Publisher: Dover Publications, Inc; (1994). Former Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities in the British Museum, E. A. Wallis Budge (1857-1934) was one of the great Egyptologists of the century and author of a host of books on ancient Egypt. For this collection, he carefully selected nine of the most interesting and important Egyptian legends and published them in hieroglyphic texts with literal translations on the facing pages. The result is a wonderful sampling of typical Egyptian literature in the best and most complex form possible.

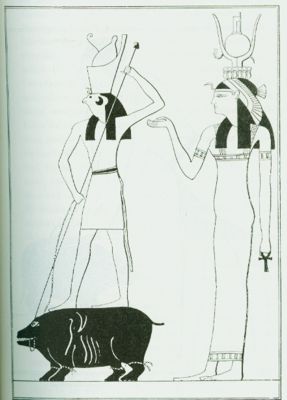

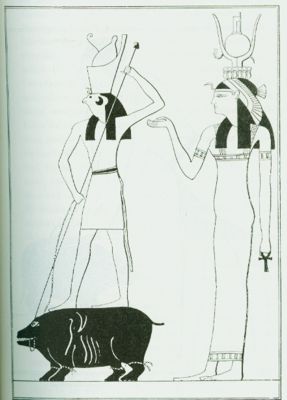

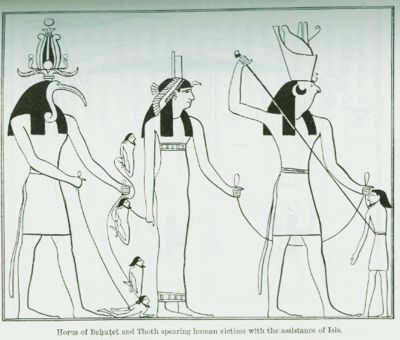

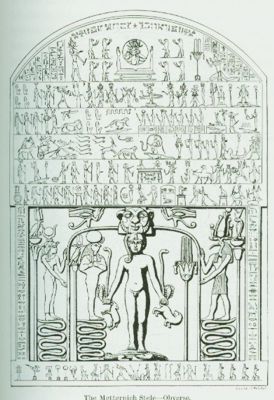

This convenient edition enables student and enthusiasts of ancient Egypt to study these ancient myths for their linguistic, literary, and cultural meanings, all in one inexpensive volume. Any student of ancient Egyptian literature, language, or culture will welcome this classic com0pliation, enhanced with 19 illustrations from Egyptian art. The legends include:

I. The Legend of the Creation.

II. The Legend of the Destruction of Mankind.

III. The Legend of Ra and the Snake-Bite.

IV. The Legend of Horus of Edfu and the Winged Disk.

V. The Legend of the Origin of Horus.

VI. Legend of Khensu Nefer-Hetep and the Princess of Bekhten.

VII. The Legend of Khnemu and a Seven Years' Famine.

VIII. The Legend of the Death and Resurrection of Horus.

VIX. The Legend of Isis and Osiris According to Classical Writers.

CONDITION: NEW. New oversized softcover. Dover (1994) 352 pages. Unblemished, unmarked, pristine in every respect. Pages are pristine; clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #1981a.

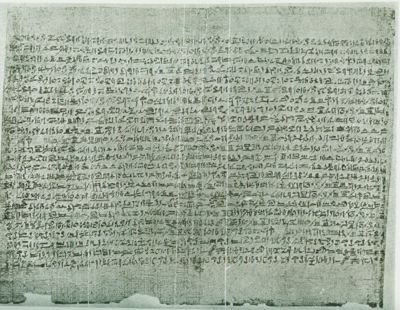

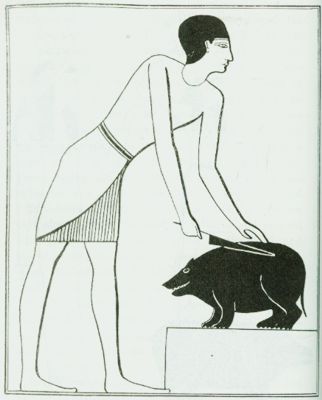

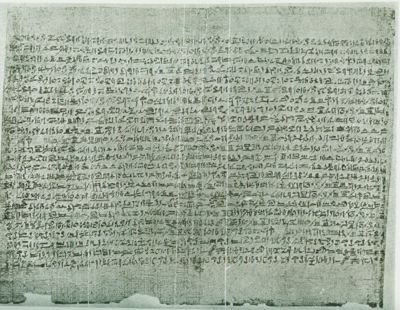

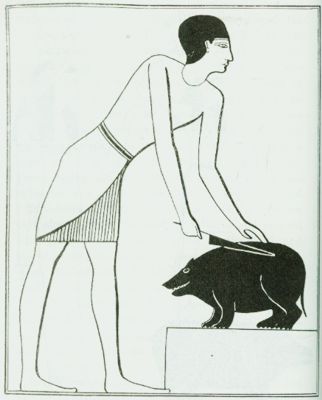

PLEASE SEE IMAGES BELOW FOR SAMPLE PAGES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

REVIEW: Great Egyptologist’s selection of nine of the most interesting and important Egyptian legends in hieroglyphic texts with literal translations on facing pages. Included are The Legend of the Creation, The Legend of the Destruction of Mankind, The Legend of Ra and the Snake-Bite, The Legend of Isis and Osiris and five more, enhanced with 19 illustrations from Egyptian art.

REVIEW: Nine legends with literal translations on facing pages. The Legend of Creation, The Legend of the Destruction of Mankind, seven more. This is the quintessential scholarly study by history’s most pre-eminent archaeologist/Egyptologist formerly of the British Museum.

REVIEW: Fascinating compendium of ancient Egyptian mythology, all explained by one of the most knowledgeable and respected Egyptologists of the early 20th century. Sheds light upon ancient Egyptian beliefs. There a few modern Egyptologists that are quick to point out Budge's many errors in translation without looking at the publication date on the book. Budge more than makes up for this, however, by including his transliterations along with the original hieroglyphic text, so that any wannabe Egyptologist can try his hand at doing better. This is the first book the serious scholar should pick up on the subject, especially if he is a student of ancient Egyptian mythology. Black and white illustrations and hieroglyphs throughout.

REVIEW: A prolific Victorian Egyptologist explores, in this classic book first published in 1912, nine of the most significant legends of Ancient Egypt’s pantheon of deities. The writings of E.A. Wallis Budge are considered somewhat dated today because of his use of an archaic system of translation, but useful illustrations and an abundance of information make them necessary resources for students of the ancient world as well as those of the evolution of historical study. Conveying the beauty and power of the religion and mythology of ancient Egypt, this fascinating book remains an important work today.

REVIEW: The first third of the book provides an overview of the ancient legends. The remaining nine chapters are each devoted to a translation of a particular legend. The left hand pages contain the original hieroglyphs and the right hand pages show the corresponding translation into English. There are no transliterations but it is most entertaining to match the phrases on the opposing pages. Some of the translations are a bit dated. Given that this was first published in 1912 it is hardly surprising. Overall a fascinating book.

REVIEW: This is one of the modern world's greatest Egyptologists presenting nine of the greatest myths of ancient Egypt, translated directly from the hieroglyphs. It doesn't get much better than this. No, you won't see any color glossies of Harrison Ford. But this is the real stuff, primary source material. Written thousands of years ago. This is required reading if you're seriously interested in ancient Egypt and their mythology.

REVIEW: Mr. Budge's book is a wonderful translation, and transliteration of famous Ancient Egyptian documents. With the hieroglyphs included in the transliteration, one is also able to study hieroglyphic translation as one reads the various myths. Because the hieroglyphs are placed in the book as uniform graphics, the continuity of the pictures helps the reader more efficiently follow the transliteration, thereby helping the reader deduce what symbols mean what, and thereby adding another facet to this wonderful volume.

REVIEW: This book offers outstanding translations of nine of ancient Egypt’s most significant legends. A good reference for the non-Egyptian reader who wants firsthand knowledge about life on the Nile. Budge's translation and use of the original text allow the Egyptologist to compare their own reading as well. Use of such a reference book will increase the reader's understanding of the rather complicated and in many ways foreign ideas in ancient Egyptian religion and mythology. A must for anyone interested in Ancient Egypt and its culture.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT EGYPT: Egyptian religion was a combination of beliefs and practices which, in the modern day, would include magic, mythology, science, medicine, psychiatry, spiritualism, herbology, as well as the modern understanding of 'religion' as belief in a higher power and a life after death. Religion played a part in every aspect of the lives of the ancient Egyptians because life on earth was seen as only one part of an eternal journey, and in order to continue that journey after death, one needed to live a life worthy of continuance.

During one's life on earth, one was expected to uphold the principle of ma'at (harmony) with an understanding that one's actions in life affected not only one's self but others' lives as well, and the operation of the universe. People were expected to depend on each other to keep balance as this was the will of the gods to produce the greatest amount of pleasure and happiness for humans through a harmonious existence which also enabled the gods to better perform their tasks.

During one's life on earth, one was expected to uphold the principle of ma'at (harmony) with an understanding that one's actions in life affected not only one's self but others' lives as well, and the operation of the universe. People were expected to depend on each other to keep balance as this was the will of the gods to produce the greatest amount of pleasure and happiness for humans through a harmonious existence which also enabled the gods to better perform their tasks.

By honoring the principle of ma'at (personified as a goddess of the same name holding the white feather of truth) and living one's life in accordance with its precepts, one was aligned with the gods and the forces of light against the forces of darkness and chaos, and assured one's self of a welcome reception in the Hall of Truth after death and a gentle judgment by Osiris, the Lord of the Dead.

The underlying principle of Egyptian religion was known as heka (magic) personified in the god Heka. Heka had always existed and was present in the act of creation. He was the god of magic and medicine but was also the power which enabled the gods to perform their functions and allowed human beings to commune with their gods. He was all-pervasive and all-encompassing, imbuing the daily lives of the Egyptians with magic and meaning and sustaining the principle of ma'at upon which life depended.

Possibly the best way to understand Heka is in terms of money: one is able to purchase a particular item with a certain denomination of currency because that item's value is considered the same, or less, than that denomination. The bill in one's hand has an invisible value given it by a standard of worth (once upon a time the gold standard) which promises a merchant it will compensate for what one is buying. This is exactly the relationship of Heka to the gods and human existence: he was the standard, the foundation of power, on which everything else depended. A god or goddess was invoked for a specific purpose, was worshipped for what they had given, but it was Heka who enabled this relationship between the people and their deities.

Possibly the best way to understand Heka is in terms of money: one is able to purchase a particular item with a certain denomination of currency because that item's value is considered the same, or less, than that denomination. The bill in one's hand has an invisible value given it by a standard of worth (once upon a time the gold standard) which promises a merchant it will compensate for what one is buying. This is exactly the relationship of Heka to the gods and human existence: he was the standard, the foundation of power, on which everything else depended. A god or goddess was invoked for a specific purpose, was worshipped for what they had given, but it was Heka who enabled this relationship between the people and their deities.

The gods of ancient Egypt were seen as the lords of creation and custodians of order but also as familiar friends who were interested in helping and guiding the people of the land. The gods had created order out of chaos and given the people the most beautiful land on earth. Egyptians were so deeply attached to their homeland that they shunned prolonged military campaigns beyond their borders for fear they would die on foreign soil and would not be given the proper rites for their continued journey after life. Egyptian monarchs refused to give their daughters in marriage to foreign rulers for the same reason. The gods of Egypt had blessed the land with their special favor, and the people were expected to honor them as great and kindly benefactors.

The gods of ancient Egypt were seen as the lords of creation and custodians of order but also as familiar friends who were interested in helping and guiding the people of the land. Long ago, they believed, there had been nothing but the dark swirling waters of chaos stretching into eternity. Out of this chaos (Nu) rose the primordial hill, known as the Ben-Ben, upon which stood the great god Atum (some versions say the god was Ptah) in the presence of Heka. Atum looked upon the nothingness and recognized his aloneness, and so he mated with his own shadow to give birth to two children, Shu (god of air, whom Atum spat out) and Tefnut (goddess of moisture, whom Atum vomited out). Shu gave to the early world the principles of life while Tefnut contributed the principles of order. Leaving their father on the Ben-Ben, they set out to establish the world.

In time, Atum became concerned because his children were gone so long, and so he removed his eye and sent it in search of them. While his eye was gone, Atum sat alone on the hill in the midst of chaos and contemplated eternity. Shu and Tefnut returned with the eye of Atum (later associated with the Udjat eye, the Eye of Ra, or the All-Seeing Eye) and their father, grateful for their safe return, shed tears of joy. These tears, dropping onto the dark, fertile earth of the Ben-Ben, gave birth to men and women.

In time, Atum became concerned because his children were gone so long, and so he removed his eye and sent it in search of them. While his eye was gone, Atum sat alone on the hill in the midst of chaos and contemplated eternity. Shu and Tefnut returned with the eye of Atum (later associated with the Udjat eye, the Eye of Ra, or the All-Seeing Eye) and their father, grateful for their safe return, shed tears of joy. These tears, dropping onto the dark, fertile earth of the Ben-Ben, gave birth to men and women.

These humans had nowhere to live, however, and so Shu and Tefnut mated and gave birth to Geb (the earth) and Nut (the sky). Geb and Nut, though brother and sister, fell deeply in love and were inseparable. Atum found their behaviour unacceptable and pushed Nut away from Geb, high up into the heavens. The two lovers were forever able to see each other but were no longer able to touch. Nut was already pregnant by Geb, however, and eventually gave birth to Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys, and Horus – the five Egyptian gods most often recognized as the earliest (although Hathor is now considered to be older than Isis). These gods then gave birth to all the other gods in one form or another.

The gods each had their own area of speciality. Bastet, for example, was the goddess of the hearth, homelife, women's health and secrets, and of cats. Hathor was the goddess of kindness and love, associated with gratitude and generosity, motherhood, and compassion. According to one early story surrounding her, however, she was originally the goddess Sekhmet who became drunk on blood and almost destroyed the world until she was pacified and put to sleep by beer which the gods had dyed red to fool her. When she awoke from her sleep, she was transformed into a gentler deity. Although she was associated with beer, Tenenet was the principle goddess of beer and also presided over childbirth. Beer was considered essential for one's health in ancient Egypt and a gift from the gods, and there were many deities associated with the drink which was said to have been first brewed by Osiris.

An early myth tells of how Osiris was tricked and killed by his brother Set and how Isis brought him back to life. He was incomplete, however, as a fish had eaten a part of him, and so he could no longer rule harmoniously on earth and was made Lord of the Dead in the underworld. His son, Horus the Younger, battled Set for eighty years and finally defeated him to restore harmony to the land. Horus and Isis then ruled together, and all the other gods found their places and areas of expertise to help and encourage the people of Egypt.

An early myth tells of how Osiris was tricked and killed by his brother Set and how Isis brought him back to life. He was incomplete, however, as a fish had eaten a part of him, and so he could no longer rule harmoniously on earth and was made Lord of the Dead in the underworld. His son, Horus the Younger, battled Set for eighty years and finally defeated him to restore harmony to the land. Horus and Isis then ruled together, and all the other gods found their places and areas of expertise to help and encourage the people of Egypt.

Among the most important of these gods were the three who made up the Theban Triad: Amun, Mut, and Knons (also known as Khonsu). Amun was a local fertility god of Thebes until the Theban noble Menuhotep II (2061-2010 B.C.) defeated his rivals and united Egypt, elevating Thebes to the position of capital and its gods to supremacy. Amun, Mut, and Khons of Upper Egypt (where Thebes was located) took on the attributes of Ptah, Sekhment, and Khonsu of Lower Egypt who were much older deities. Amun became the supreme creator god, symbolized by the sun; Mut was his wife, symbolized by the sun's rays and the all-seeing eye; and Khons was their son, the god of healing and destroyer of evil spirits.

These three gods were associated with Ogdoad of Hermopolis, a group of eight primordial deities who "embodied the qualities of primeval matter, such as darkness, moistness, and lack of boundaries or visible powers. It usually consisted of four deities doubled to eight by including female counterparts" (Pinch, 175-176). The Ogdoad (pronounced OG-doh-ahd) represented the state of the cosmos before land rose from the waters of chaos and light broke through the primordial darkness and were also referred to as the Hehu (`the infinities'). They were Amun and Amaunet, Heh and Hauhet, Kek and Kauket, and Nun and Naunet each representing a different aspect of the formless and unknowable time before creation: Hiddenness (Amun/Amaunet), Infinity (Heh/Hauhet), Darkness (Kek/Kauket), and the Abyss (Nut/Naunet). The Ogdoad are the best example of the Egyptian's insistence on symmetry and balance in all things embodied in their male/female aspect which was thought to have engendered the principle of harmony in the cosmos before the birth of the world.

The Egyptians believed that the earth (specifically Egypt) reflected the cosmos. The stars in the night sky and the constellations they formed were thought to have a direct bearing on one's personality and future fortunes. The gods informed the night sky, even traveled through it, but were not distant deities in the heavens; the gods lived alongside the people of Egypt and interacted with them daily. Trees were considered the homes of the gods and one of the most popular of the Egyptian deities, Hathor, was sometimes known as "Mistress of the Date Palm" or "The Lady of the Sycamore" because she was thought to favor these particular trees to rest in or beneath. Scholars Oakes and Gahlin note that "Presumably because of the shade and the fruit provided by them, goddesses associated with protection, mothering, and nurturing were closely associated with [trees]. Hathor, Nut, and Isis appear frequently in the religious imagery and literature [in relation to trees]".

The Egyptians believed that the earth (specifically Egypt) reflected the cosmos. The stars in the night sky and the constellations they formed were thought to have a direct bearing on one's personality and future fortunes. The gods informed the night sky, even traveled through it, but were not distant deities in the heavens; the gods lived alongside the people of Egypt and interacted with them daily. Trees were considered the homes of the gods and one of the most popular of the Egyptian deities, Hathor, was sometimes known as "Mistress of the Date Palm" or "The Lady of the Sycamore" because she was thought to favor these particular trees to rest in or beneath. Scholars Oakes and Gahlin note that "Presumably because of the shade and the fruit provided by them, goddesses associated with protection, mothering, and nurturing were closely associated with [trees]. Hathor, Nut, and Isis appear frequently in the religious imagery and literature [in relation to trees]".

Plants and flowers were also associated with the gods, and the flowers of the ished tree were known as "flowers of life" for their life-giving properties. Eternity, then, was not an ethereal, nebulous concept of some 'heaven' far from the earth but a daily encounter with the gods and goddesses one would continue to have contact with forever, in life and after death. In order for one to experience this kind of bliss, however, one needed to be aware of the importance of harmony in one's life and how a lack of such harmony affected others as well as one's self. The 'gateway sin' for the ancient Egyptians was ingratitude because it threw one off balance and allowed for every other sin to take root in a person's soul. Once one lost sight of what there was to be grateful for, one's thoughts and energies were drawn toward the forces of darkness and chaos.

This belief gave rise to rituals such as The Five Gifts of Hathor in which one would consider the fingers of one's hand and name the five things in life one was most grateful for. One was encouraged to be specific in this, naming anything one held dear such as a spouse, one's children, one's dog or cat, or the tree by the stream in the yard. As one's hand was readily available at all times, it would serve as a reminder that there were always five things one should be grateful for, and this would help one to maintain a light heart in keeping with harmonious balance. This was important throughout one's life and remained equally significant after one's death since, in order to progress on toward an eternal life of bliss, one's heart needed to be lighter than a feather when one stood in judgment before Osiris.

According to the scholar Margaret Bunson: "The Egyptians feared eternal darkness and unconsciousness in the afterlife because both conditions belied the orderly transmission of light and movement evident in the universe. They understood that death was the gateway to eternity. The Egyptians thus esteemed the act of dying and venerated the structures and the rituals involved in such a human adventure." The structures of the dead can still be seen throughout Egypt in the modern day in the tombs and pyramids which still rise from the landscape. There were structures and rituals after life, however, which were just as important.

According to the scholar Margaret Bunson: "The Egyptians feared eternal darkness and unconsciousness in the afterlife because both conditions belied the orderly transmission of light and movement evident in the universe. They understood that death was the gateway to eternity. The Egyptians thus esteemed the act of dying and venerated the structures and the rituals involved in such a human adventure." The structures of the dead can still be seen throughout Egypt in the modern day in the tombs and pyramids which still rise from the landscape. There were structures and rituals after life, however, which were just as important.

The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts: the Khat was the physical body; the Ka one’s double-form; the Ba a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens; Shuyet was the shadow self; Akh the immortal, transformed self, Sahu and Sechem aspects of the Akh; Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil; Ren was one’s secret name. All nine of these aspects were part of one's earthly existence and, at death, the Akh (with the Sahu and Sechem) appeared before the great god Osiris in the Hall of Truth and in the presence of the Forty-Two Judges to have one's heart (Ab) weighed in the balance on a golden scale against the white feather of truth.

One would need to recite the Negative Confession (a list of those sins one could honestly claim one had not committed in life) and then one's heart was placed on the scale. If one's heart was lighter than the feather, one waited while Osiris conferred with the Forty-Two Judges and the god of wisdom, Thoth, and, if considered worthy, was allowed to pass on through the hall and continue one's existence in paradise; if one's heart was heavier than the feather it was thrown to the floor where it was devoured by the monster Ammut (the gobbler), and one then ceased to exist.

Once through the Hall of Truth, one was then guided to the boat of Hraf-haf ("He Who Looks Behind Him"), an unpleasant creature, always cranky and offensive, whom one had to find some way to be kind and courteous to. By showing kindness to the unkind Hraf-haf, one showed one was worthy to be ferried across the waters of Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) to the Field of Reeds which was a mirror image of one's life on earth except there was no disease, no disappointment, and no death. One would then continue one's existence just as before, awaiting those one loved in life to pass over themselves or meeting those who had gone on before.

Once through the Hall of Truth, one was then guided to the boat of Hraf-haf ("He Who Looks Behind Him"), an unpleasant creature, always cranky and offensive, whom one had to find some way to be kind and courteous to. By showing kindness to the unkind Hraf-haf, one showed one was worthy to be ferried across the waters of Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) to the Field of Reeds which was a mirror image of one's life on earth except there was no disease, no disappointment, and no death. One would then continue one's existence just as before, awaiting those one loved in life to pass over themselves or meeting those who had gone on before.

Although the Greek historian Herodotus claims that only men could be priests in ancient Egypt, the Egyptian record argues otherwise. Women could be priests of the cult of their goddess from the Old Kingdom onward and were accorded the same respect as their male counterparts. Usually a member of the clergy had to be of the same sex as the deity they served. The cult of Hathor, most notably, was routinely attended to by female clergy (it should be noted that 'cult' did not have the same meaning in ancient Egypt that it does today - cults were simply sects of one religion). Priests and Priestesses could marry, have children, own land and homes and lived as anyone else except for certain ritual practices and observances regarding purification before officiating. Bunson writes: "In most periods, the priests of Egypt were members of a family long connected to a particular cult or temple. Priests recruited new members from among their own clans, generation after generation. This meant that they did not live apart from their own people and thus maintained an awareness of the state of affairs in their communities."

Priests, like scribes, went through a prolonged training period before beginning service and, once ordained, took care of the temple or temple complex, performed rituals and observances (such as marriages, blessings on a home or project, funerals), performed the duties of doctors, healers, astrologers, scientists, and psychologists, and also interpreted dreams. They blessed amulets to ward off demons or increase fertility, and also performed exorcisms and purification rites to rid a home of ghosts. Their chief duty was to the god they served and the people of the community, and an important part of that duty was their care of the temple and the statue of the god within. Priests were also doctors in the service of Heka, no matter what other deity they served directly. An example of this is how all the priests and priestesses of the goddess Serket (Selket) were doctors but their ability to heal and invoke Serket was enabled through the power of Heka.

The temples of ancient Egypt were thought to be the literal homes of the deities they honored. Every morning the head priest or priestess, after purifying themselves with a bath and dressing in clean white linen and clean sandals, would enter the temple and attend to the statue of the god as they would to a person they were charged to care for. The doors of the sanctuary were opened to let in the morning light, and the statue, which always resided in the innermost sanctuary, was cleaned, dressed, and anointed with oil; afterwards, the sanctuary doors were closed and locked. No one but the head priest was allowed such close contact with the god. Those who came to the temple to worship only were allowed in the outer areas where they were met by lesser clergy who addressed their needs and accepted their offerings.

The temples of ancient Egypt were thought to be the literal homes of the deities they honored. Every morning the head priest or priestess, after purifying themselves with a bath and dressing in clean white linen and clean sandals, would enter the temple and attend to the statue of the god as they would to a person they were charged to care for. The doors of the sanctuary were opened to let in the morning light, and the statue, which always resided in the innermost sanctuary, was cleaned, dressed, and anointed with oil; afterwards, the sanctuary doors were closed and locked. No one but the head priest was allowed such close contact with the god. Those who came to the temple to worship only were allowed in the outer areas where they were met by lesser clergy who addressed their needs and accepted their offerings.

There were no official `scriptures' used by the clergy but the concepts conveyed at the temple are thought to have been similar to those found in works such as the Pyramid Texts, the later Coffin Texts, and the spells found in the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Although the Book of the Dead is often referred to as `The Ancient Egyptian Bible' it was no such thing. The Book of the Dead is a collection of spells for the soul in the afterlife. The Pyramid Texts are the oldest religious texts in ancient Egypt dating from circa 2400-2300 B.C. The Coffin Texts were developed later from the Pyramid Texts circa 2134-2040 B.C. while the Book of the Dead (actually known as the Book on Coming Forth by Day) was set down sometime circa 1550-1070 B.C.

All three of these works deal with how the soul is to navigate the afterlife. Their titles (given by European scholars) and the number of grand tombs and statuary throughout Egypt, not to mention the elaborate burial rituals and mummies, have led many people to conclude that Egypt was a culture obsessed with death when, actually, the Egyptians were wholly concerned with life. The Book on Coming Forth by Day, as well as the earlier texts, present spiritual truths one would have heard while in life and remind the soul of how one should now act in the next phase of one's existence without a physical body or a material world. The soul of any Egyptian was expected to recall these truths from life, even if they never set foot inside a temple compound, because of the many religious festivals the Egyptians enjoyed throughout the year.

Religious festivals in Egypt integrated the sacred aspect of the gods seamlessly with the daily lives of the people. Egyptian scholar Lynn Meskell notes that "religious festivals actualized belief; they were not simply social celebrations. They acted in a multiplicity of related spheres" (Nardo, 99). There were grand festivals such as The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi in honor of the god Amun and lesser festivals for other gods or to celebrate events in the life of the community.

Religious festivals in Egypt integrated the sacred aspect of the gods seamlessly with the daily lives of the people. Egyptian scholar Lynn Meskell notes that "religious festivals actualized belief; they were not simply social celebrations. They acted in a multiplicity of related spheres" (Nardo, 99). There were grand festivals such as The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi in honor of the god Amun and lesser festivals for other gods or to celebrate events in the life of the community.

Bunson writes, "On certain days, in some eras several times a month, the god was carried on arks or ships into the streets or set sail on the Nile. There the oracles took place and the priests answered petitions". The statue of the god would be removed from the inner sanctuary to visit the members of the community and take part in the celebration; a custom which may have developed independently in Egypt or come from Mesopotamia where this practice had a long history. The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi was a celebration of life, wholeness, and community, and, as Meskell notes, people attended this festival and visited the shrine to "pray for bodily integrity and physical vitality" while leaving offerings to the god or goddess as a sign of gratitude for their lives and health.

Meskell writes: "One may envisage a priest or priestess coming and collecting the offerings and then replacing the baskets, some of which have been detected archaeologically. The fact that these items of jewelry were personal objects suggests a powerful and intimate link with the goddess. Moreover, at the shrine site of Timna in the Sinai, votives were ritually smashed to signify the handing over from human to deity, attesting to the range of ritual practices occurring at the time. There was a high proportion of female donors in the New Kingdom, although generally tomb paintings tend not to show the religous practices of women but rather focus on male activities".

The smashing of the votives signified one's surrender to the benevolent will of the gods. A votive was anything offered in fulfillment of a vow or in the hopes of attaining some wish. While votives were often left intact, they were sometimes ritually destroyed to signify the devotion one had to the gods; one was surrendering to them something precious which one could not take back. There was no distinction at these festivals between those acts considered 'holy' and those which a modern sensibility would label 'profane'. The whole of one's life was open for exploration during a festival, and this included sexual activity, drunkenness, prayer, blessings for one's sex life, for one's family, for one's health, and offerings made both in gratitude and thanksgiving and in supplication.

The smashing of the votives signified one's surrender to the benevolent will of the gods. A votive was anything offered in fulfillment of a vow or in the hopes of attaining some wish. While votives were often left intact, they were sometimes ritually destroyed to signify the devotion one had to the gods; one was surrendering to them something precious which one could not take back. There was no distinction at these festivals between those acts considered 'holy' and those which a modern sensibility would label 'profane'. The whole of one's life was open for exploration during a festival, and this included sexual activity, drunkenness, prayer, blessings for one's sex life, for one's family, for one's health, and offerings made both in gratitude and thanksgiving and in supplication.

Families attended the festivals together as did teenagers and young couples and those hoping to find a mate. Elder members of the community, the wealthy, the poor, the ruling class, and the slaves were all a part of the religious life of the community because their religion and their daily lives were completely intertwined and, through that faith, they recognized their individual lives were all an interwoven tapestry with every other. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

DEATH IN ANCIENT EGYPT: To the ancient Egyptians, death was not the end of life but only a transition to another plane of reality. Once the soul had successfully passed through judgment by the god Osiris, it went on to an eternal paradise, The Field of Reeds, where everything which had been lost at death was returned and one would truly live happily ever after. Even though the Egyptian view of the afterlife was the most comforting of any ancient civilization, people still feared death. Even in the periods of strong central government when the king and the priests held absolute power and their view of the paradise-after-death was widely accepted, people were still afraid to die.

The rituals concerning mourning the dead never dramatically changed in all of Egypt's history and are very similar to how people react to death today. One might think that knowing their loved one was on a journey to eternal happiness, or living in paradise, would have made the ancient Egyptians feel more at peace with death, but this is clearly not so. Inscriptions mourning the death of a beloved wife or husband or child - or pet - all express the grief of loss, how they miss the one who has died, how they hope to see them again someday in paradise - but not expressing the wish to die and join them anytime soon. There are texts which express a wish to die, but this is to end the sufferings of one's present life, not to exchange one's mortal existence for the hope of eternal paradise.

The rituals concerning mourning the dead never dramatically changed in all of Egypt's history and are very similar to how people react to death today. One might think that knowing their loved one was on a journey to eternal happiness, or living in paradise, would have made the ancient Egyptians feel more at peace with death, but this is clearly not so. Inscriptions mourning the death of a beloved wife or husband or child - or pet - all express the grief of loss, how they miss the one who has died, how they hope to see them again someday in paradise - but not expressing the wish to die and join them anytime soon. There are texts which express a wish to die, but this is to end the sufferings of one's present life, not to exchange one's mortal existence for the hope of eternal paradise.

The prevailing sentiment among the ancient Egyptians, in fact, is perfectly summed up by Hamlet in Shakespeare's famous play: "The undiscovered country, from whose bourn/No traveler returns, puzzles the will/And makes us rather bear those ills we have/Than fly to others that we know not of". The Egyptians loved life, celebrated it throughout the year, and were in no hurry to leave it even for the kind of paradise their religion promised. A famous literary piece on this subject is known as Discourse Between a Man and his Ba (also translated as Discourse Between a Man and His Soul and The Man Who Was Weary of Life). This work, dated to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 B.C.), is a dialogue between a depressed man who can find no joy in life and his soul which encourages him to try to enjoy himself and take things easier. The man, at a number of points, complains how he should just give up and die - but at no point does he seem to think he will find a better existence on the 'other side' - he simply wants to end the misery he is feeling at the moment.

The dialogue is often characterized as the first written work debating the benefits of suicide, but scholar William Kelly Simpson disagrees, writing: "What is presented in this text is not a debate but a psychological picture of a man depressed by the evil of life to the point of feeling unable to arrive at any acceptance of the innate goodness of existence. His inner self is, as it were, unable to be integrated and at peace. His dilemma is presented in what appears to be a dramatic monologue which illustrates his sudden changes of mood, his wavering between hope and despair, and an almost heroic effort to find strength to cope with life. It is not so much life itself which wearies the speaker as it is his own efforts to arrive at a means of coping with life's difficulties." As the speaker struggles to come to some kind of satisfactory conclusion, his soul attempts to guide him in the right direction of giving thanks for his life and embracing the good things the world has to offer. His soul encourages him to express gratitude for the good things he has in this life and to stop thinking about death because no good can come of it. To the ancient Egyptians, ingratitude was the 'gateway sin' which let all other sins into one's life. To the ancient Egyptians, ingratitude was the 'gateway sin' which let all other sins into one's life. If one were grateful, then one appreciated all that one had and gave thanks to the gods; if one allowed one's self to feel ungrateful, then this led one down a spiral into all the other sins of bitterness, depression, selfishness, pride, and negative thought.

The message of the soul to the man is similar to that of the speaker in the biblical book of Ecclesiastes when he says, "God is in heaven and thou upon the earth; therefore let thy words be few". The man, after wishing that death would take him, seems to consider the words of the soul seriously. Toward the end of the piece, the man says, "Surely he who is yonder will be a living god/Having purged away the evil which had afflicted him...Surely he who is yonder will be one who knows all things". The soul has the last word in the piece, assuring the man that death will come naturally in time and life should be embraced and loved in the present.

Another Middle Kingdom text, The Lay of the Harper, also resonates with the same theme. The Middle Kingdom is the period in Egyptian history when the vision of an eternal paradise after death was most seriously challenged in literary works. Although some have argued that this is due to a lingering cynicism following the chaos and cultural confusion of the First Intermediate Period, this claim is untenable. The First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 B.C.) was simply an era lacking a strong central government, but this does not mean the civilization collapsed with the disintegration of the Old Kingdom, simply that the country experienced the natural changes in government and society which are a part of any living civilization.

The Lay of the Harper is even more closely comparable to Ecclesiastes in tone and expression as seen clearly in the refrain: "Enjoy pleasant times/And do not weary thereof/Behold, it is not given to any man to take his belongings with him/Behold, there is no one departed who will return again" (Simpson, 333). The claim that one cannot take one's possessions into death is a direct refutation of the tradition of burying the dead with grave goods: all those items one enjoyed and used in life which would be needed in the next world.

It is entirely possible, of course, that these views were simply literary devices to make a point that one should make the most of life instead of hoping for some eternal bliss beyond death. Still, the fact that these sentiments only find this kind of expression in the Middle Kingdom suggests a significant shift in cultural focus. The most likely cause of this is a more 'cosmopolitan' upper class during this period, which was made possible precisely by the First Intermediate Period, which 19th- and 20th-century CE scholarship has done so much to vilify. The collapse of the Old Kingdom of Egypt empowered regional governors and led to greater freedom of expression from different areas of the country instead of conformity to a single vision of the king.

The cynicism and world-weary view of religion and the afterlife disappear after this period and New Kingdom (circa 1570-1069 B.C.) literature again focuses on an eternal paradise which waits beyond death. The popularity of The Book of Coming Forth by Day (better known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead) during this period is amongst the best evidence for this belief. The Book of the Dead is an instructional manual for the soul after death, a guide to the afterlife, which a soul would need in order to reach the Field of Reeds.

The reputation Ancient Egypt has acquired of being 'death-obsessed' is actually undeserved; the culture was obsessed with living life to its fullest. The mortuary rituals so carefully observed were intended not to glorify death but to celebrate life and ensure it continued. The dead were buried with their possessions in magnificent tombs and with elaborate rituals because the soul would live forever once it has passed through death's doors. While one lived, one was expected to make the most of the time and enjoy one's self as much as one could. A love song from the New Kingdom of Egypt, one of the so-called Songs of the Orchard, expresses the Egyptian view of life perfectly.

In the following lines, a sycamore tree in the orchard speaks to one of the young women who planted it when she was a little girl: "Give heed! Have them come bearing their equipment; Bringing every kind of beer, all sorts of bread in abundance; Vegetables, strong drink of yesterday and today; And all kinds of fruit for enjoyment; Come and pass the day in happiness; Tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow; Even for three days, sitting beneath my shade."

Although one does find expressions of resentment and unhappiness in life - as in the Discourse Between a Man and his Soul - Egyptians, for the most part, loved life and embraced it fully. They did not look forward to death or dying - even though promised the most ideal afterlife - because they felt they were already living in the most perfect of worlds. An eternal life was only worth imagining because of the joy the people found in their earthly existence. The ancient Egyptians cultivated a civilization which elevated each day to an experience in gratitude and divine transcendence and a life into an eternal journey of which one's time in the body was only a brief interlude. Far from looking forward to or hoping for death, the Egyptians fully embraced the time they knew on earth and mourned the passing of those who were no longer participants in the great festival of life. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MORTUARY RITUALS: Ever since European archaeologists began excavating in Egypt in the 18th and 19th centuries A.D., the ancient culture has been largely associated with death. Even into the mid-20th century CE reputable scholars were still writing on the death-obsessed Egyptians whose lives were lacking in play and without joy. Mummies in dark, labyrinthine tombs, strange rituals performed by dour priests, and the pyramid tombs of the kings remain the most prominent images of ancient Egypt in many people's minds even in the present day, and an array of over 2,000 deities - many of them uniquely associated with the afterlife - simply seems to add to the established vision of the ancient Egyptians as obsessed with death. Actually, though, they were fully engaged in life, so much so that their afterlife was considered an eternal continuation of their time on earth.

When someone died in ancient Egypt the funeral was a public event which allowed the living to mourn the passing of a member of the community and enabled the deceased to move on from the earthly plane to the eternal. Although there were outpourings of grief and deep mourning over the loss of someone they loved, they did not believe the dead person had ceased to exist; they had merely left the earth for another realm. In order to make sure they reached their destination safely, the Egyptians developed elaborate mortuary rituals to preserve the body, free the soul, and send it on its way. These rituals encouraged the healthy expression of grief among the living but concluded with a feast celebrating the life of the deceased and his or her departure, emphasizing how death was not the end but only a continuation. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick notes, "for the life-loving Egyptians, the guarantee of continuing life in the netherworld was immensely important". The mortuary rituals provided the people with just that sort of guarantee.

The earliest burials in ancient Egypt were simple graves in which the deceased was placed, on the left side, accompanied by some grave goods. It is clear there was already a belief in some kind of afterlife prior to circa 3500 B.C. when mummification began to be practiced but no written record of what form this belief took. Simple graves in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (circa 6000 - 3150 B.C.) evolved into the mastaba tombs of the Early Dynastic Period (circa 3150 - 2613 B.C.) which then became the grand pyramids of the Old Kingdom (circa 2613-2181 B.C.). All of these periods believed in an afterlife and engaged in mortuary rituals, but those of the Old Kingdom are the best known from images on tombs. Although it is usually thought that everyone in Egypt was mummified after their death, the practice was expensive & only the upper class and nobility could afford it.

By the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, the culture had a clear understanding of how the universe worked and humanity's place in it. The gods had created the world and the people in it through the agency of magic (heka) and sustained it through magic as well. All the world was imbued with mystical life generated by the gods who would welcome the soul when it finally left the earth for the afterlife. In order for the soul to make this journey, the body it left behind needed to be carefully preserved, and this is why mummification became such an integral part of the mortuary rituals. Although it is usually thought that everyone in Egypt was mummified after their death, the practice was expensive, and usually only the upper class and nobility could afford it.

In the Old Kingdom the kings were buried in their pyramid tombs, but from the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 B.C.) onwards, kings and nobles favored tombs cut into rock face or into the earth. By the time of the New Kingdom (circa 1570-1069 B.C.) the tombs and the rituals leading to burial had reached their highest state of development. There were three methods of embalming/funerary ritual available: the most expensive and elaborate, a second, cheaper option which still allowed for much of the first, and a third which was even cheaper and afforded little of the attention to detail of the first. The following rituals and embalming methods described are those of the first, most elaborate option, which was performed for royalty and the specific rituals are those observed in the New Kingdom of Egypt.

After death, the body was brought to the embalmers where the priests washed and purified it. The mortuary priest then removed those organs which would decay most quickly and destroy the body. In early mummification, the organs of the abdomen and the brain were placed in canopic jars which were thought to be watched over by the guardian gods known as The Four Sons of Horus. In later times the organs were taken out, treated, wrapped, and placed back into the body, but canopic jars were still placed in tombs, and The Four Sons of Horus were still thought to keep watch over the organs.

The embalmers removed the organs from the abdomen through a long incision cut into the left side; for the brain, they would insert a hooked surgical tool up through the dead person's nose and pull the brain out in pieces. There is also evidence of embalmers breaking the nose to enlarge the space to get the brain out more easily. Breaking the nose was not the preferred method, though, because it could disfigure the face of the deceased and the primary goal of mummification was to keep the body intact and preserved as life-like as possible. The removal of the organs and brain was all about drying out the body - the only organ they left in place was the heart because that was thought to be the seat of the person's identity. This was all done because the soul needed to be freed from the body to continue on its eternal journey into the afterlife and, to do so, it needed to have an intact 'house' to leave behind and also one it would recognize if it wished to return to visit.

After the removal of the organs, the body was soaked in natron for 70 days and then washed and purified again. It was then carefully wrapped in linen; a process which could take up to two weeks. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson explains: "This was an important aspect of the mortuary process, accompanied by incantations, hymns, and ritual ceremonies. In some instances the linens taken from shrines and temples were provided to the wealthy or aristocratic deceased in the belief that such materials had special graces and magical powers. An individual mummy would require approximately 445 square yards of material. Throughout the wrappings semiprecious stones and amulets were placed in strategic positions, each one guaranteed to protect a certain region of the human anatomy in the afterlife." Among the most important of these amulets was the one which was placed over the heart. This was done to prevent the heart from bearing witness against the deceased when the moment of judgment came. Since the heart was the seat of individual character, and since it was obvious that people often made statements they later regretted, it was considered important to have a charm to prevent that possibility. The embalmers would then return the mummy to the family who would have had a coffin or sarcophagus made. The corpse would not be placed in the coffin yet, however, but would be laid on a bier and then moved toward a waiting boat on the Nile River. This was the beginning of the funeral service which started in the early morning, usually departing either from a temple of the king or the embalmer's center. The servants and poorer relations of the deceased were at the front of the procession carrying flowers and food offerings. They were followed by others carrying grave goods such as clothing and shabti dolls, favorite possessions of the deceased, and other objects which would be necessary in the afterlife.

Directly in front of the corpse would be professional mourners, women known as the Kites of Nephthys, whose purpose was to encourage others to express their grief. The kites would wail loudly, beat their breasts, strike their heads on the ground, and scream in pain. These women were dressed in the color of mourning and sorrow, a blue-gray, and covered their faces and hair with dust and earth. This was a paid position, and the wealthier the deceased, the more kites would be present in the procession. A scene from the tomb of the pharaoh Horemheb (1320-1292 B.C.) of the New Kingdom vividly depicts the Kites of Nephthys at work as they wail and fling themselves to the ground.

In the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt, the servants would have been killed upon reaching the tomb so that they could continue to serve the deceased in the afterlife. By the time of the New Kingdom, this practice had long been abandoned and an effigy now took the place of the servants known as a tekenu. Like the shabti dolls, which one would magically animate in the afterlife to perform work, the tekenu would later come to life, in the same way, to serve the soul in paradise.

The corpse and the tekenu were followed by priests, and when they reached the eastern bank of the Nile, the tekenu and the oxen who had pulled the corpse were ritually sacrificed and burned. The corpse was then placed on a mortuary boat along with two women who symbolized the goddesses Isis and Nephthys. This was in reference to the Osiris myth in which Osiris is killed by his brother Set and returned to life by his sister-wife Isis and her sister Nephthys. In life, the king was associated with the son of Osiris and Isis, Horus, but in death, with the Lord of the Dead, Osiris. The women would address the dead king as the goddesses speaking to Osiris.

The boat sailed from the east side (representing life) to the west (the land of the dead) where it docked and the body was then moved to another bier and transported to its tomb. A priest would have already arranged to have the coffin or sarcophagus set up at the entrance of the tomb, and at this point, the corpse was placed inside of it. The priest would then perform the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony during which he would touch the corpse at various places on the body in order to restore the senses so the deceased could again see, hear, smell, taste, and talk.

During this ceremony, the two women representing Isis and Nephthys would recite The Lamentations of Isis and Nephthys, the call-and-response incantation which re-created the moment when Osiris had been brought back to life by the sisters. The lid was then fastened on the coffin and it was carried into the tomb. The tomb would have the deceased's name written in it, statues and pictures of him or her in life, and inscriptions on the wall (Pyramid Texts) telling the story of their life and providing instructions for the afterlife. Prayers would be made for the soul of the deceased and grave goods would be arranged around the coffin; after this, the tomb would be sealed.

The family was expected to provide for the continued existence of the departed by bringing them food and drink offerings and remembering their name. If a family found this too burdensome, they hired a priest (known as a Ka-Servant) to perform the duties and rituals. Lists of food and drink to be brought were inscribed on the tomb (Offering Lists) as well as an autobiography of the departed so they would be remembered. The soul would continue to exist peacefully in the next life (following justification) as long as these offerings were made.

The priests, family, and guests would then sit down for a feast to celebrate the life of the departed and his forward journey to paradise. This celebration took place outside of the tomb under a tent erected for the purpose. Food, beer, and wine would have been brought earlier and was now served as an elaborate picnic banquet. The deceased would be honored with the kind of festival he or she would have known and enjoyed in life. When the party concluded, the guests would return to their homes and go on with life.

For the soul of the departed, however, a new life had just begun. Following the mortuary rituals and the closing of the tomb, the soul was thought to wake in the body and feel disoriented. Inscriptions on the wall of the tomb, like the Pyramid Texts, or in one's coffin, as with the Coffin Texts, would remind the soul of its life on earth and direct it to leave the body and move forward. These texts were replaced in the New Kingdom of Egypt by the Book of the Dead. One of the gods, most often Anubis, would appear to lead the soul forth toward the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Two Truths) where it would be judged.

Depictions of the judgment frequently show a long line of souls waiting for their moment to appear before Osiris and these are cared for by deities like Qebhet, who provided them with cool, refreshing water. Familiar goddesses like Nephthys, Isis, Neith, and Serket would also be there to comfort and encourage the soul. When one's time came, one would move forward to where Osiris, Anubis, and Thoth stood by the scales of justice and would recite the Negative Confessions, a ritual list of sins one could honestly say one had not committed. At this point one's heart was weighed in the balance against the white feather of truth; if one's heart was lighter than the feather, one was justified, and if not, the heart was dropped to the floor where it was eaten by the monster Amut and the soul would then cease to exist.

If one had been justified by the weighing of the heart, Osiris, Thoth, and Anubis would confer with the Forty-two Judges and then allow one to pass on toward paradise. This next part of the journey takes different forms depending on different texts and time periods. In some versions, the soul must still avoid pitfalls, demons, and dangers, and required the assistance of a guide book such as The Egyptian Book of the Dead. In other depictions, once one had been justified, one went to the shores of Lily Lake where a final test had to be passed.

The ferryman was an eternally unpleasant man named Hraf-hef to whom the soul needed to be kind and gracious. If one passed this final test, one was rowed across the lake to paradise in the Field of Reeds. Here the soul would find everything and everyone thought to be lost through death. Those who had passed on before would be waiting as well as one's favorite pets. The house the soul had loved while alive, the neighborhood, friends, all would be waiting and the soul would enjoy this life eternally without the threat of loss and in the company of the immortal gods. This final paradise, however, was only possible if the family on earth had performed the mortuary rituals completely and if they continued to honor and remember the departed soul. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

GRAVE GOODS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: The concept of the afterlife changed in different eras of Egypt's very long history, but for the most part, it was imagined as a paradise where one lived eternally. To the Egyptians, their country was the most perfect place which had been created by the gods for human happiness. The afterlife, therefore, was a mirror image of the life one had lived on earth - down to the last detail - with the only difference being an absence of all those aspects of existence one found unpleasant or sorrowful. One inscription about the afterlife talks about the soul being able to eternally walk beside its favorite stream and sit under its favorite sycamore tree, others show husbands and wives meeting again in paradise and doing all the things they did on earth such as plowing the fields, harvesting the grain, eating and drinking.

In order to enjoy this paradise, however, one would need the same items one had during one's life. Tombs and even simple graves included personal belongings as well as food and drink for the soul in the afterlife. These items are known as 'grave goods' and have become an important resource for modern-day archaeologists in identifying the owners of tombs, dating them, and understanding Egyptian history. Although some people object to this practice as 'grave robbing,' the archaeologists who professionally excavate tombs are assuring the deceased of their primary objective: to live forever and have their name remembered eternally. According to the ancient Egyptians' own beliefs, the grave goods placed in the tomb would have performed their function many centuries ago.

Grave goods, in greater or lesser number and varying worth, have been found in almost every Egyptian grave or tomb which was not looted in antiquity. The articles one would find in a wealthy person's tomb would be similar to those considered valuable today: ornately crafted objects of gold and silver, board games of fine wood and precious stone, carefully wrought beds, chests, chairs, statuary, and clothing. The finest example of a pharaoh's tomb, of course, is King Tutankhamun's from the 14th century B.C. discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 A.D., but there have been many tombs excavated throughout ancient Egypt which make clear the social status of the individual buried there. Even those of modest means included some grave goods with the deceased. The primary purpose of grave goods was not so show off the deceased person's status but to provide the dead with what they would need in the afterlife.

The primary purpose of grave goods, though, was not so show off the deceased person's status but to provide the dead with what they would need in the afterlife. A wealthy person's tomb, therefore, would have more grave goods - of whatever that person favored in life - than a poorer person. Favorite foods were left in the tomb such as bread and cake, but food and drink offerings were expected to be made by one's survivors daily. In the tombs of the upper-class nobles and royalty an offerings chapel was included which featured the offerings table. One's family would bring food and drink to the chapel and leave it on the table. The soul of the deceased would supernaturally absorb the nutrients from the offerings and then return to the afterlife. This ensured one's continual remembrance by the living and so one's immortality in the next life.

If a family was too busy to tend to the daily offerings and could afford it, a priest (known as the ka-priest or water-pourer) would be hired to perform the rituals. However the offerings were made, though, they had to be taken care of on a daily basis. The famous story of Khonsemhab and the Ghost (dated to the New Kingdom of Egypt circa 1570-1069 B.C.) deals with this precise situation. In the story, the ghost of Nebusemekh returns to complain to Khonsemhab, high priest of Amun, that his tomb has fallen into disrepair and he has been forgotten so that offerings are no longer brought. Khonsemhab finds and repairs the tomb and also promises that he will make sure offerings are provided from then on. The end of the manuscript is lost, but it is presumed the story ends happily for the ghost of Nebusemekh. If a family should forget their duties to the soul of the deceased, then they, like Khonsemhab, could expect to be haunted until this wrong was righted and regular food and drink offerings reinstated.

Beer was the drink commonly provided with grave goods. In Egypt, beer was the most popular beverage - considered the drink of the gods and one of their greatest gifts - and was a staple of the Egyptian diet. A wealthy person (such as Tutankhamun) was buried with jugs of freshly brewed beer whereas a poorer person would not be able to afford that kind of luxury. People were often paid in beer so to bury a jug of it with a loved one would be comparable to someone today burying their paycheck. Beer was sometimes brewed specifically for a funeral, since it would be ready, from inception to finish, by the time the corpse had gone through the mummification process. After the funeral, once the tomb had been closed, the mourners would have a banquet in honor of the dead person's passing from time to eternity, and the same brew which had been made for the deceased would be enjoyed by the guests; thus providing communion between the living and the dead.

Among the most important grave goods was the shabti doll. Shabti were made of wood, stone, or faience and often were sculpted in the likeness of the deceased. In life, people were often called upon to perform tasks for the king, such as supervising or laboring on great monuments, and could only avoid this duty if they found someone willing to take their place. Even so, one could not expect to shirk one's duties year after year, and so a person would need a good excuse as well as a replacement worker.

Since the afterlife was simply a continuation of the present one, people expected to be called on to do work for Osiris in the afterlife just as they had labored for the king. The shabti doll could be animated, once one had passed into the Field of Reeds, to assume one's responsibilities. The soul of the deceased could continue to enjoy a good book or go fishing while the shabti took care of whatever work needed to be done. Just as one could not avoid one's obligations on earth, though, the shabti could not be used perpetually. A shabti doll was good for only one use per year. People would commission as many shabti as they could afford in order to provide them with more leisure in the afterlife.

Shabti dolls are included in graves throughout the length of Egypt's history. In the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 B.C.) they were mass-produced, as many items were, and more are included in tombs and graves of every social class from then on. The poorest people, of course, could not even afford a generic shabti doll, but anyone who could, would pay to have as many as possible. A collection of shabtis, one for each day of the year, would be placed in the tomb in a special shabti box which was usually painted and sometimes ornamented.

Instructions on how one would animate a shabti in the next life, as well as how to navigate the realm which waited after death, was provided through the texts inscribed on tomb walls and, later, written on papyrus scrolls. These are the works known today as the Pyramid Texts (circa 2400-2300 B.C.), the Coffin Texts (circa 2134-2040 B.C.), and The Egyptian Book of the Dead (circa 1550-1070 B.C.). The Pyramid Texts are the oldest religious texts and were written on the walls of the tomb to provide the deceased with assurance and direction.

When a person's body finally failed them, the soul would at first feel trapped and confused. The rituals involved in mummification prepared the soul for the transition from life to death, but the soul could not depart until a proper funeral ceremony was observed. When the soul woke in the tomb and rose from its body, it would have no idea where it was or what had happened. In order to reassure and guide the deceased, the Pyramid Texts and, later, Coffin Texts were inscribed and painted on the inside of tombs so that when the soul awoke in the dead body it would know where it was and where it now had to go.

These texts eventually turned into The Egyptian Book of the Dead (whose actual title is The Book of Coming Forth by Day), which is a series of spells the dead person would need in order to navigate through the afterlife. Spell 6 from the Book of the Dead is a rewording of Spell 472 of the Coffin Texts, instructing the soul in how to animate the shabti. Once the person died and then the soul awoke in the tomb, that soul was led - usually by the god Anubis but sometimes by others - to the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Two Truths) where it was judged by the great god Osiris. The soul would then speak the Negative Confession (a list of 'sins' they could honestly say they had not committed such as 'I have not lied, I have not stolen, I have not purposefully made another cry'), and then the heart of the soul would be weighed on a scale against the white feather of ma'at, the principle of harmony and balance.

If the heart was found to be lighter than the feather, then the soul was considered justified; if the heart was heavier than the feather, it was dropped onto the floor where it was eaten up by the monster Amut, and the soul would then cease to exist. There was no 'hell' for eternal punishment of the soul in ancient Egypt; their greatest fear was non-existence, and that was the fate of someone who had done evil or had purposefully failed to do good.

If the soul was justified by Osiris then it went on its way. In some eras of Egypt, it was believed the soul then encountered various traps and difficulties which they would need the spells from The Book of the Dead to get through. In most eras, though, the soul left the Hall of Truth and traveled to the shores of Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) where they would encounter the perpetually unpleasant ferryman known as Hraf-hef ("He Who Looks Behind Himself") who would row the soul across the lake to the paradise of the Field of Reeds. Hraf-hef was the 'final test' because the soul had to find some way to be polite, forgiving, and pleasant to this very unpleasant person in order to cross.

Once across the lake, the soul would find itself in a paradise which was the mirror image of life on earth, except lacking any disappointment, sickness, loss, or - of course - death. In The Field of Reeds the soul would find the spirits of those they had loved and had died before them, their favorite pet, their favorite house, tree, stream they used to walk beside - everything one thought one had lost was returned, and, further, one lived on eternally in the direct presence of the gods.

Reuniting with loved ones and living eternally with the gods was the hope of the afterlife but equally so was being met by one's favorite pets in paradise. Pets were sometimes buried in their own tombs but, usually, with their master or mistress. If one had enough money, one could have one's pet cat, dog, gazelle, bird, fish, or baboon mummified and buried alongside one's corpse. The two best examples of this are High Priestess Maatkare Mutemhat (circa 1077-943 B.C.) who was buried with her mummified pet monkey and the Queen Isiemkheb (circa 1069-943 B.C.) who was buried with her pet gazelle.

Mummification was expensive, however, and especially the kind practiced on these two animals. They received top treatment in their mummification and this, of course, represented the wealth of their owners. There were three levels of mummification available: top-of-the-line where one was treated as a king (and received a burial in keeping with the glory of the god Osiris); middle-grade where one was treated well but not that well; and the cheapest where one received minimal service in mummification and burial. Still, everyone - rich or poor - provided their dead with some kind of preparation of the corpse and grave goods for the afterlife.

Pets were treated very well in ancient Egypt and were represented in tomb paintings and grave goods such as dog collars. The tomb of Tutankhamun contained dog collars of gold and paintings of his hunting hounds. Although modern day writers often claim that Tutankhamun's favorite dog was named Abuwtiyuw, who was buried with him, this is not correct. Abuwtiyuw is the name of a dog from the Old Kingdom of Egypt who so pleased the king that he was given private burial and all the rites due a person of noble birth. The identity of the king who loved the dog is unknown, but the dog of king Khufu (2589-2566 B.C.), Akbaru, was greatly admired by his master and buried with him.

The collars of dogs, which frequently gave their name, often were included as grave goods. The tomb of the noble Maiherpre, a warrior who lived under the reign of Thutmose III (1458-1425 B.C.) contained two ornamented dog collars of leather. These were dyed pink and decorated with images. One of them has horses and lotus flowers punctuated by brass studs while the other depicts hunting scenes and has the dog's name, Tantanuit, engraved on it. These are two of the best examples of the kind of ornate work which went into dog collars in ancient Egypt. By the time of the New Kingdom, in fact, the dog collar was its own type of artwork and worthy to be worn in the afterlife in the presence of the gods.

During the period of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 B.C.) there was a significant philosophical shift where people questioned the reality of this paradise and emphasized making the most of life because nothing existed after death. Some scholars have speculated that this belief came about because of the turmoil of the First Intermediate Period which came before the Middle Kingdom, but there is no convincing evidence of this. Such theories are always based on the claim that the First Intermediate Period of Egypt was a dark time of chaos and confusion which it most certainly was not. The Egyptians always emphasized living life to its fullest - their entire culture is based on gratitude for life, enjoying life, loving every moment of life - so an emphasis on this was nothing new. What makes the Middle Kingdom belief so interesting, however, is its denial of immortality in an effort to make one's present life even more precious.

The literature of the Middle Kingdom expresses a lack of belief in the traditional view of paradise because people in the Middle Kingdom were more 'cosmopolitan' than in earlier times and were most likely attempting to distance themselves from what they saw as 'superstition'. The First Intermediate Period had elevated the different districts of Egypt, made their individual artistic expressions as valuable as the state-mandated art and literature of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, and people felt freer to express their personal opinions rather than just repeat what they had been told. This skepticism disappears during the time of the New Kingdom, and - for the most part - the belief in the paradise of the Field of Reeds was constant throughout Egypt's history. A component of this belief was the importance of grave goods which would serve the deceased in the afterlife just as well as they had on the earthly plane. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

ANCIENT EYPTIAN FUNERARY ART: While mummification and traditional Egyptian religious customs remained in fashion even after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 31 B.C., funerary art forms such as this painted mummy portrait began to display an increased interest in Graeco-Roman artistic traditions. Though such mummy portraits have been found throughout Egypt, most have come from the Fayum Basin in Lower Egypt, hence the moniker “Fayum Portraits.” Many examples of this type of mummy portrait use the Greek encaustic technique, in which pigment is dissolved in hot or cold wax and then used to paint.

The naturalism of these works and the interest in realistically depicting a specific individual also stem from Greek conceptions of painting. The subjects of the majority of the Fayum Portraits are styled and clothed according to contemporary Roman fashions, most likely those made popular by the current ruling imperial family. The portrait of the bearded man, for example, is reminiscent of images of the emperor Hadrian (ruled 117–138 AD), who popularized the fashion of wearing a thick beard as symbol of his philhellenism. In their function, these mummy portraits are entirely Egyptian and reflect religious traditions surrounding the preservation of the body of the deceased that span back thousands of years. In form, these works are uniquely multicultural and display the intersection of Roman and provincial customs. [Dartmouth College].

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMY PORTRAITS: Sarcophagi in human form were created as a means not only of protecting the actual body, but also as an alternate anchor for the life force, or ka, in the event that the corpse was damaged. An early development in anthropoid coffins during Egypt’s First Intermediate Period (circa 2160–2025 BC) was the introduction of face masks, placed over the heads of mummies. Images like the one seen here continue this tradition. Painted on wooden panels or linen shrouds, they were affixed over the mummy’s wrappings.

Rooted in Egyptian practices and beliefs, mummy portraits from the Fayum region of Egypt are also indebted to art of the Classical world. Created from the first through the third century CE, during Egypt’s Roman period, the images draw stylistically on Graeco-Roman models. Although they appear to be naturalistic likenesses, there is debate over whether these “portraits” are actually drawn from life. Some believe they were painted and first displayed in the home during the subject’s lifetime, while others suggest that they were produced at the time of death to be carried with the body in a procession known as the ekphora, a tradition originating in Greece.

THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOOK OF THE DEAD: The Egyptian Book of the Dead is a collection of spells which enable the soul of the deceased to navigate the afterlife. The famous title was given the work by western scholars; the actual title would translate as The Book of Coming Forth by Day or Spells for Going Forth by Day and a more apt translation to English would be The Egyptian Book of Life. Although the work is often referred to as "the Ancient Egyptian Bible" it is no such thing although the two works share the similarity of being ancient compilations of texts written at different times eventually gathered together in book form. The Book of the Dead was never codified and no two copies of the work are exactly the same. They were created specifically for each individual who could afford to purchase one as a kind of manual to help them after death.