|

|

The Flaming Sword

in Serbia and Elsewhere

by

Mrs St Clair Stobart

|

|

|

|

This is

the 1916 First Edition, in worn condition

This is one of the most important

memoirs to emerge from the Balkans' Campaign of the First World

War. This account is of great historical interest for its

first-hand description of the fighting in the Serbian Campaign

and of the Retreat through Montenegro and Albania.

|

|

|

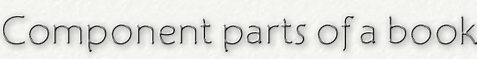

Front cover and spine

Further images of this book are

shown below

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher and place of

publication |

|

Dimensions in inches (to

the nearest quarter-inch) |

|

London: Hodder and Stoughton |

|

4¾ inches wide x 7½ inches tall |

| |

|

|

|

Edition |

|

Length |

|

1916 First Edition |

|

[viii] + 325 pages plus list of staff at the Stobart Hospital, Kragujevatz |

| |

|

|

|

Condition of covers |

|

Internal condition |

|

Original pictorial cloth in worn condition.

The covers are very heavily rubbed with, on the front cover, significant

loss of original colour; there is also a frayed patch in the centre. The

spine has darkened with age and is soiled and stained. The head of the spine

is snagged with a half-inch tear in the cloth in the centre. The spine ends

and corners are bumped and frayed with further splits in the cloth,

including a number of small tears at the tail of the spine and the card

exposed on the corners. There are indentations along the edges of the

boards, including a prominent notch on the front bottom edge. The images

below give a good indication of the current worn state of the covers. |

|

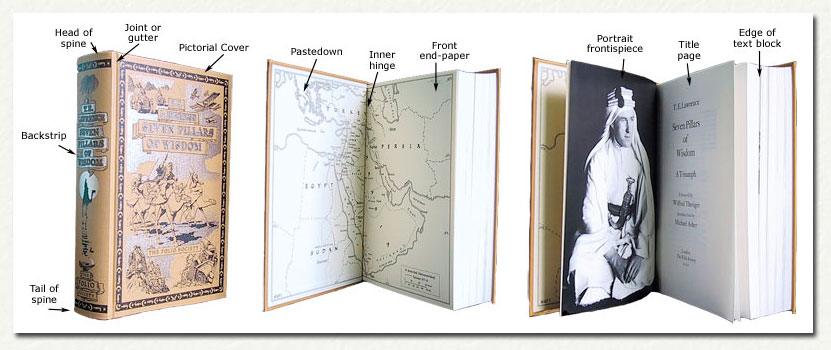

The inner hinges are cracked with both the

front and rear blank end-papers missing. The volume opens directly to the

Half-Title page where a previous owner has (it appears) attempted to

classify the account into the years 1914 and 1915 with marks on the

outside edge of text block and, in addition, has also marked the on the

fore-edge the location of all the illustrations. There should be a folding

map facing page 1 but this is missing and, attached to the missing map, was

page ix of the preliminaries, containing the "Guide to Readers" which lists

the component arts of the volume (as noted in the "Contents" section below).

There is scattered foxing and the paper has tanned noticeably with age.

There is some separation between the inner gatherings. The edge of the text

block is grubby, dust-stained and foxed, also with the small inked marks

mentioned above . The previous owner has also added some inked annotations. |

| |

|

|

|

Dust-jacket present? |

|

Other

comments |

|

No |

|

This is a worn and defective example of the

scarce First Edition, with a large number of issues as noted,

including significant discoloured covers, cracked hinges and missing

end-papers, and a missing map. All the illustrations, however, are present. |

| |

|

|

|

Illustrations,

maps, etc |

|

Contents |

|

There are a number of photographic

illustrations, all of which are shown below, but there is no

separate List of Illustrations. There is a Frontispiece,

followed by Plates facing pages 10; 18; 42; 50; 72; 74 (sketch

map); 82; 106; 130; 154; 178; 202; 226; 250; 274; and 298. There

should also be a folding map facing page 1: unfortunately, this

is missing. |

|

The book is in five parts:

PART I. deals with preliminaries and military hospital work in

Bulgaria, Belgium, France, and Serbia.

PART II. deals with roadside tent dispensary work in Serbia.

PART III. is a diary of the Serbian retreat.

PART IV. discusses the war work of women, the Serbian character

and the evils of war.

PART V. comprises letters and lists of personnel. |

| |

|

|

|

Post & shipping

information |

|

Payment options |

|

The packed weight is approximately

700 grams.

Full shipping/postage information is

provided in a panel

at the end of this listing.

|

|

Payment options

:

-

UK buyers: cheque (in

GBP), debit card, credit card (Visa, MasterCard but

not Amex), PayPal

-

International buyers: credit card

(Visa, MasterCard but not Amex), PayPal

Full payment information is provided in a

panel at the end of this listing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Flaming Sword in Serbia

and Elsewhere

Preface

I HAVE written this book in the first person, because it would be an

affectation to write in the neuter person about these things which I

have felt and seen.

But if the book has interest, this should lie, not only in the

personal experiences, but in the effect which these have had upon

the beliefs of a modern woman who is probably representative of

other women of her century.

I believe that humankind is at the parting of the ways. One way

leads to evolution along spiritual lines the other to devolution

along lines of materialism ; and the sign-post to devolution is

militarism. For militarism is a movement of retrogression, which

will bring civilisation to a standstill in a cul-de-sac.

And I believe that militarism can only be destroyed with the help of

Woman. In countries where Woman has least sway, militarism is most

dominant. Militarism is maleness run riot.

Man's dislike of militarism is prompted by sentiment, or by a sense

of expediency. It is not due to instinct ; therefore it is not

forceful. The charge of human life has not been given by Nature to

Man. Therefore, to Man, the preservation of life is of less

importance than many other things. Nature herself sets an example of

recklessness with males ; she creates, in the insect world, millions

of useless male lives for one that is to serve the purpose of

maleness. It is said that the proportion of male may-flies to female

is six thousand to one. Nature behaves similarly though with more

moderation with male human babies. More males than females are born,

but fewer males survive. Is war perhaps another extravagant device

of Nature ; or is society, which encourages war, blindly copying

Nature for the same end ?

On the other hand, Woman's dislike of militarism is an instinct.

Life for Woman is not a seed which can be sown broadcast, to take

root, or to perish, according to chance. For Woman, life is an

individual charge ; therefore, for Woman, the preservation of life

is of more importance than many other things.

By God and by Man, the care of life is given to Woman, before and

after birth. With all her being, Woman primitive Woman has defended

that life as an individual concrete life ; and with all her being,

Woman modern Woman must now, in an enlarged sphere, defend the

abstract life of humankind.

Therefore, it is good that Woman shall put aside her qualms, and go

forth and see for herself the dangers that threaten life.

Therefore it is good that Woman shall record, as Woman, and not as

neuter, the things which she has felt, and seen, during an

experience of militarism at first hand.

|

|

|

|

|

The Flaming Sword in Serbia

and Elsewhere

Excerpts:

Chapter I

To go through the horrors of war, and

keep one's reason that is hell. Those who have seen the fiery Moloch,

licking up his human sacrifices, will harbour no illusions ; they

will know that the devouring deity of War is an idol, and no true

God. The vision is salutary ; it purges the mind from false values,

and gives courage for the exorcism of abominations still practised

by a world which has no knowledge of the God of Life. The

abominations which are now practised in Europe, by twentieth century

man, are no less abominable than those practised of old in the

Valley of Hinnom. The heathen passed their sons and daughters

through the fire, to propitiate their deity ; the Lord God condemned

the practice. We Christians pass our sons and daughters through the

fire of bloody wars, to propitiate our deities of patriotism and

nationalism. Would the Lord God not also condemn our practice ? But

we, alas ! have no Josiah to act for the Lord God (2 Kings xxiii.).

The heathen wept at the destruction of Baal, but the worship of the

pure God prevailed. No one believes that his god is false, till it

has been destroyed. Therefore, we must destroy militarism, in and

through this war, and future generations will justify the deed.

I am neither a doctor nor a nurse, but I have occupied myself within

the sphere of war for the following reasons.

After four years spent on the free veldt of the South African

Transvaal, I returned to London (in 1907) with my mind cleared of

many prejudices. The political situation into which I found myself

plunged, was interesting. Both men and women were yawning themselves

awake ; the former after a long sleep, the latter for the first time

in history. The men had been awakened by the premonitory echo of

German cannons, and were, in lounge suits, beginning to look to

their national defences. Women probably did not know what awakened

them, but the same cannons were responsible.

For self-defence is the first law of subconscious nature ; and the

success of Prussian cannons would mean the annihilation of woman as

the custodian of human life.

It was natural that woman's first cry should be for the political

vote : influence without power is a chimera. But it was also natural

that at a moment when national defence was the rallying shibboleth

for men, the political claims of women should be by men disregarded.

Political power without national responsibility would be unwisdom

and injustice.

But was woman incapable of taking a responsible share in national

defence ?

I believed that prejudice alone stood in woman's way. Prejudice,

however, is not eliminated by calling it prejudice. Practical

demonstration that prejudice is prejudice, will alone dissipate the

phantom.

But what form should woman's share in national defence assume ? In

these days of the supremacy of mechanical over physical force,

woman's ability as a fighting factor could have been shown. But

there were three reasons against experimenting in this direction.

Firstly, it would have been difficult to obtain opportunities for

the necessary proof of capacity.

Secondly, woman could not fight better than man, even if she could

fight as well, and, as an argument for the desirability of giving

woman a share in national responsibility, it would be unwise to

present her as a performer of less capacity than man. The expediency

of woman's participation in national defence could best be proved by

showing that there was a sphere of work in which she could be at

least as capable as man.

Thirdly, and of primary importance, if the entrance of women into

the political arena, is an evolutionary movement forwards and not

backwards woman must not encumber herself with legacies of male

traditions likely to compromise her freedom of evolvement along the

line of life.

If the Woman's Movement has, as I believe, value in the scheme of

creation, it must tend to the furtherance of life, and not of death.

Now, militarism means supremacy of the principle that to produce

death is, on occasions many occasions more useful than to preserve

life. Militarism has, in one country at least, reached a climax, and

I believe it is because we women feel in our souls that life has a

meaning, and a value, which are in danger of being lost in

militarism, that we are at this moment instinctively asking for a

share in controlling those human lives for which Nature has made us

specially responsible. " Intellect," says Bergson, " is

characterised by a natural inability to comprehend life." Woman may

be less heavily handicapped in an attempt to understand it ?

It may well have been the echo of German cannons which aroused woman

to self-consciousness.

Demonstration, therefore, of the capacity of woman to take a useful

share in national defence must be given in a sphere of work in which

preservation, and not destruction of life, is the objective. Such

work was the care of the sick and wounded.

In a former book, War and Women, an account has been given of the

founding of the " Women's Convoy Corps," as the practical result of

these ideas. The work which was accomplished by members of this

Corps, in Bulgaria, during the first Balkan War, 1912-13, afforded

the first demonstration of the principle that women could

efficiently work in hospitals of war, not only as nurses that had

already been proved in the Crimean War but as doctors, orderlies,

administrators, in every department of responsibility, and thus set

men free for the fighting line.

I had hoped that, as far as I was concerned, it would never be

necessary again to undertake a form of work which is to me

distasteful. But when the German War broke out in August, 1914, I

found to my disappointment, that the demonstration of 1912-13 needed

corroboration. For I had one day the privilege of a conversation

with an important official of the British Red Cross Society, and, to

my surprise, he repeated the stale old story that women surgeons

were not strong enough to operate in hospitals of war, and that

women could not endure the hardships and privations incidental to

campaigns.

I reminded him of the women at Kirk Kilisse. " Ah ! " he replied, "

that was exceptional." I saw at once that he, and those of whom he

was representative, must be shown that it was not exceptional. But

where there is no will to be convinced, the only convincing argument

is the deed. Action is a universal language which all can

understand.

I must, therefore, once more enter the arena ; for my previous

experience of war had corroborated my belief that the co-operation

of woman in warfare, is essential for the future abolition of war ;

essential, that is, for the retrieval of civilisation. For these

reasons I must not shirk.

Chapter II

I HAD gone to Bulgaria with open mind,

prepared to judge for myself whether it was true that war calls

forth valuable human qualities which would otherwise lie dormant,

and whether it was true that the purifying influence of war is so

great, that it compensates the human race for the disadvantages of

war. My mind had been open for impressions of so-called glories of

war.

But the glories which came under my notice in Bulgaria, were

butchered human beings, devastated villages, a general callousness

about the value of human life, that was for me a revelation. This

time I should go out with no illusions about these martial glories.

But how should I go ? To my satisfaction I found that the Bulgarian

" first step " had led to an easy staircase, and when I offered the

services of a Woman's Unit to the Belgian Red Cross, I was at once

invited to establish a hospital in Brussels.

The St. John Ambulance Association, at the instigation of Lady

Perrott, and the Women's Imperial Service League (which, with Lady

Muir Mackenzie as Vice-Chairman, had been organised with the view of

helping to equip women's hospital units), together with many other

generous friends, provided money and equipment, and a Woman's Unit

was assembled.

I went to Brussels in advance of the unit, to make arrangements, and

was given, as hospital premises, the fine buildings of the

University.

The day after arrival, I had begun the improvisation of lecture and

class-rooms into wards, when, that same day, the work was

interrupted by the entry of the Germans, who took possession of the

Belgian Capital. During three days and nights the triumphant army,

faultlessly equipped, paraded through the streets. For some hours I

watched it from the second floor window of a restaurant in the

Boulevard des Jardins Botaniques, together with my husband, who was

to act as Hon. Treasurer, and the Vicar of the Hampstead Garden

Suburb, who was to act as Chaplain to our unit. And my mind at once

filled with presage of the tough job which the Allies had

undertaken.

The picture upon which we looked was indeed remarkable. Belgium had

been " safeguarded " from aggression, by treaties with the most

civilised nations of the world. But here now were the legitimate

inhabitants of the capital of Belgium standing in their thousands,

gazing helplessly, in dumb bewilderment, whilst the army of one of

these " most civilised " Governments streamed triumphantly, as

conquerors, through their streets. And in all those streets, the

only sounds were the clamping feet of the marching infantry, the

clattering hoofs of the horses of the proud Uhlans and Hussars, and

the rumbling of the wagons carrying murderous guns.

The people stood silent, with frozen hearts, beholding, as fossils

might, the scenes in which they could no longer move.

For them, earth, air, sky, the whole world outside that never-ending

procession, seemed expunged. No one noticed whether rain fell, or

the sun shone, whilst that piteous pageant of triumphant enmity,

passed, in ceaseless cinema, before their eyes.

All idea of establishing a hospital for the Allies had to be

abandoned. The Croix Rouge was taken over by the Germans, and

hospitals would be commandeered for German soldiers. My one desire

was to get in touch with my unit ; for they might, I thought, in

response to the cable sent by the Belgian Red Cross, on the night of

our arrival, be already on their way to join me, and might be in

difficulties, surrounded by the Germans. Whatever personal risk

might be incurred, I must leave Brussels.

The Consuls advised me to remain: they said I should not be able to

obtain a passport from the German General. When I remonstrated, they

shrugged their shoulders and said, " Well, go and ask him yourself !

" I went, and obtained an officially stamped passport for myself and

my two companions, who gallantly, and against my wishes, insisted on

accompanying me, and sharing the risks of passing through the

enemy's lines.

But, notwithstanding our stamped passport, we were, at Hasselt,

arrested as spies, and at Tongres we were condemned to be shot

within twenty-four hours. The story of our escape and eventual

imprisonment, at Aachen, has been told elsewhere, but one remark of

the German Devil -Major Commandant at Tongres, is so illuminative of

the spirit of militarism that it bears repetition.

The Major said, " You are spies " ; he fetched a big book from a

shelf, opened it, and pointing on a certain page, he continued, "

and the fate of spies is to be shot within twenty-four hours. Now

you know your fate." I answered cheerily, as though it were quite a

common occurrence to hear little fates like that, " but, mein Herr

Major, I am sure you would not wish to do such an injustice. Won't

you at least look at our papers, and see that what we have told you

is true ; we were engaged in hospital work when," etc. He then

replied, and his voice rasped and barked like that of a mad dog, "

You are English, and, whether you are right or wrong, this is a war

of annihilation." . . .

Chapter XVIII

THE sixty soldiers were already at the

station when we arrived, also Colonel Pops Dragitch, and Colonel

Ouentchitch followed, to watch the embarkation of wagons and motors

on the train. We were not to leave till early next morning, so we

went in relays to the camp for supper, leaving the others in charge

of the goods ; and we slept that night in our carriages on the

train.

The hospital was to be officially known as " The First Serbian

-English Field Hospital (Front) Commandant Madame Stobart," and we

were attached to the Schumadia Division (25,000 men). The oxen and

horses were entrained at dawn, but the train did not start till

eight o'clock (Saturday, October 2nd). Colonels Guentchitch and Pops

Dragitch came to say good-bye. We little guessed that we should next

meet at Scutari, near the coast, in Albania, after three months of

episodes more tragic than any which even Serbia has ever before

endured. I was amused at being told that I was the commander of the

train, and that no one would be allowed to board it, or to leave it,

without my permission. I don't remember much amusement after that.

We reached Nish at seven that evening, and during the train's halt

of an hour and twenty minutes, we dined in the station restaurant.

Members of the Second British Farmers' Unit, which had been working

at Belgrade, with Mr. Wynch as Administrator, were at the station on

their way to England.

After Nish the line was monopolised by military trains, in which

were Serbian soldiers, dressed in every variety of old garments,

brown or grey the nearest approach to uniform producible. They

reminded me of the saying of Emerson, " No army of freedom or

independence is ever well dressed."

We arrived at Pirot at 3 a.m. (Sunday, October 3rd). I was

interested and also glad to find that I was not going to be coddled

by the military authorities. The assumption was that I knew all

about everything, and didn't need to be told ; so I assumed it too.

As soon as the train stopped at Pirot, I called the sergeant, and

then immediately I realised that I was face to face with a quaint

little embarrassment. In the hospital at Kragujevatz, and at all the

dispensaries, the soldiers and the people had always called me "

Maika." For the position I then held this word was appropriate

enough ; but now, as Commander of an army column, might not other

men hold our men to ridicule if they were under the orders of "

Maika " ? The sergeant appeared in answer to my summons. He saluted.

" Ja, Maika? "" he answered. There was no time for hesitation ;

there never should be ; act first and find the reason afterwards is

often the best policy, and I quickly determined to remain " Maika."

The word " Maika " is already, to Serbian hearts, rich with

impressions, of the best qualities of the old-fashioned woman ; it

would do no harm to add to this a few impressions of qualities of

authority and power not hithertoassociated with women. It was a

risk, but I risked it, and I never had cause for regret. I then told

the sergeant to disembark the men, oxen, horses, and wagons, while

the chauffeurs saw to the handling of the motors. I hoped that

meantime a message would arrive giving the order for the next move ;

but, as nothing happened, I started off at 5 a.m. in one of the

cars, with Dr. Coxon and the interpreter, to try and find the Staff

Headquarters. Colonel Terzitch having, at Aranjelovatz, said I

should find him at Pirot, I went into the town and asked at various

public offices where Colonel Terzitch could be found, but no one

could, or would, give any information, and we were eventually

driving off on a false scent, and in a wrong direction, when I

stopped an officer, who was driving towards us in his carriage, and

I asked him to direct us. He gave us the information we wanted, and

we ultimately tracked the Staff to their Headquarters, in their

tents in a field about five kilometres from Pirot, at the moment

when Major Popovitch was starting to meet us. Our train had arrived

earlier than was expected, and he said he was glad we had pushed on.

He took us at once to see the Commandant, who was awaiting us, and

he gave us a hearty welcome. He was in the tent which we had given

him, but it was wrongly pitched. So we took it down and put it up in

the right way, whilst the Colonel told his soldiers to watch and see

how it should be done. Then he took us to have slatko (jam) and

coffee in the ognishta ; a circular fence, made of kukurus, enclosed

a wood fire, which was crackling busily in the middle ; in a circle

round the fire was a trench, about three feet deep and two feet

wide, with a bank all round, levelled as a seat. We sat either on

dry hay on the bank, or on stools, our feet comfortably touching

ground in the trench. The usual slatko and glasses of water,

followed by Turkish coffee and cigarettes, were handed round. We

were so delighted with the ognishta that the Colonel said he would

tell his men to build one for us in our camp, and later in the

afternoon this was done.

Meantime we returned to the station, to bring out the convoy. The

Colonel and Major Popovitch met us on the road and helped us to

choose a site for the camp, about half a mile away from, and on a

hill above their Headquarters. It was necessary to protect ourselves

from aeroplanes by sheltering as much as possible near trees, and we

found, on a reaped wheat-field adjoining a vine-field, a gorgeous

site which gave us the protection of a hedge and of some trees, with

a view to the east over a valley which divided us from Pirot, and

the mountains of Bulgaria beyond.

From over these mountains we might at any moment hear the sound of

guns telling of the outbreak of hostilities between Bulgaria and

Serbia. The Allies had played into the hands of Bulgaria, and, by

refusing to let Serbia strike at her own time, had given Bulgaria

the advantage of striking at her time, chosen when support from

Germany and Austria on the Danube front, would make the position of

Serbia hopeless.

The Colonel had hospitably invited us all to lunch with him, but we

couldn't burden him to that extent ; and the camp work had to be

done. Eight of us, therefore the doctors, two nurses, two

chauffeurs, the secretary, and myself took advantage of the

hospitality, and enjoyed an excellent lunch in a cottage which the

officers were using as messroom.

By the evening our first camp was installed, and next day, Monday,

October 4th, Major Popovitch and various officers from Pirot came

up, while the nurses were busy preparing dressings and cleaning the

surgical instruments in the hospital tent, to see the arrangements.

They seemed much pleased. The Pirot officers came up in an English

car made in Birmingham.

We only had as patients a few sick soldiers, but there was plenty to

do otherwise in arranging the men's routine of work and meals. The

soldiers always did what they were told, but they needed constant

prodding. In the morning early, for instance, I went to see if the

horses and oxen were being properly fed, and I found that the hay

and oats sent was insufficient ; there was not enough to go round.

Though the men knew this, they had said and done nothing, but had

tethered the horses on barren ground, and left the oxen foodless in

the same empty field. They were surprised when I told them that they

must take all the animals to a pasture.

But they were quite as careless with their own food. They had eaten

no hot meal since we left Kragujevatz ; but, even now, when they had

the chance, they were contenting themselves with bread and cheese,

because the cook was too lazy to prepare hot food, and I had to

insist on a meal being cooked. I made them light a fire, clean a big

cauldron, and stew sheep and potatoes, with plenty of paprika or red

pepper ; then I told them I should come and taste it later. This I

did, and the stew was excellent.

We were encircled by mountains, and near us, to the east, the

beautiful little village of Suvadol, 1,300 feet above the sea,

nestled snugly in its orchards of plums and apples.

The whole valley between us and Pirot was alive with bivouacs of

armed men, all ready to march on Bulgaria. At any moment we might

hear the rumbling of cannons over the hills, telling us that war had

begun. But, as yet, the mountains were silent, their secrets hidden

in the blue mist, which, in the evening, under the sunset colours,

quickened into rainbows.

On Wednesday, October 6th, we waited all day for news. We noticed

that the grey dots in the valley below were fast disappearing ;

something was evidently happening down there. And that evening our

turn came. At seven o'clock twenty-four of us, including the

Commissaire and Treasurer (Sandford and Merton, the inseparables),

and the Serbian dispenser, were sitting in our picturesque ognishta,

round the wood fire, which held a tripod with a cheery kettle for

after-supper tea. The opening of our ognishta faced the Bulgarian

mountains, but the night was dark, and everything beyond our tiny

firelit circle was invisible. We had nearly finished supper, and

some of us were lighting cigarettes, when a drab-dressed soldier an

orderly from Staff Headquarters appeared in the entrance. He handed

to me a small, white, square envelope, addressed to the Commander of

the Column. I opened it and took out a slip of paper ; I put my

signature upon the envelope as a token of receipt, and gave it to

the messenger, and he disappeared. The interpreter, Vooitch, came

and stood behind me, and we read the slip of paper in silence ; then

he whispered the translation. I shall never forget the looks of

eager expectation on the faces which were illumined by the

firelight. " What does it say ? " " We move from here at five

o'clock to-morrow morning," was the answer. The destination, must,

of course, not be revealed. Immediately, when the precious tea had

been drunk, we all went out and began preparations. As every one was

new to the work, it was better to do all we could before going to

bed. The men were called, and dispensary and kitchen tents and their

contents were packed, and also my tent, to save time in the morning.

From midnight to 3.30 a.m. I rested in the dug-out, round the fire,

looking out over the dark valley to the invisible mountains. What a

silence ! Would it soon be broken by a murderous sound echoing

through the valley ? Were those men, those peasant soldiers in the

plain below, already rushing to be destroyed, shattered into ugly

fragments, by other men other peasant soldiers who would also be

shattered into ugly fragments soon ? Yes, soon, very soon, Hell

would be let loose in the name of Heaven.

I rose at 3.30 to ensure that everyone should be in time at his or

her own job, and punctually at five o'clock all was ready for the

start. With human beings, as with all animals, habit is second

nature ; whatsoever thing is done at the beginning, that same thing,

rather than some other thing, comes most easily at all times. " As

it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be," is the text for

most folks. I took care, therefore, that the start should be

methodical. At the sound of the whistle, the convoy drew up in line

; first, the ox-wagons, loaded with tents and stores and general

equipment, the leading wagon carrying the Red Cross flag ; next, the

horse-drawn wagons, also with stores and provisions ; in these rode

the dispenser, Sandford and Merton, and the interpreter ; then the

motor ambulances, in which travelled the twenty-one members of the

British Staff with their personal kit . . .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please note: to avoid opening the book out, with the

risk of damaging the spine, some of the pages were slightly raised on the

inner edge when being scanned, which has resulted in some blurring to the

text and a

shadow on the inside edge of the final images. Colour reproduction is shown

as accurately as possible but please be aware that some colours

are difficult to scan and may result in a slight variation from

the colour shown below to the actual colour.

In line with eBay guidelines on picture sizes, some of the illustrations may

be shown enlarged for greater detail and clarity.

The inner

hinges are cracked with both the front and rear blank

end-papers missing. The volume opens directly to the

Half-Title page where a previous owner has (it appears)

attempted to classify the account into the years 1914 and

1915 with marks on the outside edge of text block and,

in addition, has also marked the on the fore-edge the

location of all the illustrations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U.K. buyers:

|

To estimate the

“packed

weight” each book is first weighed and then

an additional amount of 150 grams is added to allow for the packaging

material (all

books are securely wrapped and posted in a cardboard book-mailer).

The weight of the book and packaging is then rounded up to the

nearest hundred grams to arrive at the postage figure. I make no charge for packaging materials and

do not seek to profit

from postage and packaging. Postage can be combined for multiple purchases. |

Packed weight of this item : approximately 700 grams

|

Postage and payment options to U.K. addresses: |

-

Details of the various postage options can be obtained by selecting

the “Postage and payments” option at the head of this

listing (above).

-

Payment can be made by: debit card, credit

card (Visa or MasterCard, but not Amex), cheque (payable to

"G Miller", please), or PayPal.

-

Please contact me with name,

address and payment details within seven days of the end of the

listing;

otherwise I reserve the right to cancel the sale and re-list the item.

-

Finally, this should be an

enjoyable experience for both the buyer and seller and I hope

you will find me very easy to deal with. If you have a question

or query about any aspect (postage, payment, delivery options

and so on), please do not hesitate to contact me.

|

|

|

|

|

International

buyers:

|

To estimate the

“packed

weight” each book is first weighed and then

an additional amount of 150 grams is added to allow for the packaging

material (all

books are securely wrapped and posted in a cardboard book-mailer).

The weight of the book and packaging is then rounded up to the

nearest hundred grams to arrive at the shipping figure.

I make no charge for packaging materials and do not

seek to profit

from shipping and handling.

Shipping can

usually be combined for multiple purchases

(to a

maximum

of 5 kilograms in any one parcel with the exception of Canada, where

the limit is 2 kilograms). |

Packed weight of this item : approximately 700 grams

| International Shipping options: |

Details of the postage options

to various countries (via Air Mail) can be obtained by selecting

the “Postage and payments” option at the head of this listing

(above) and then selecting your country of residence from the drop-down

list. For destinations not shown or other requirements, please contact me before buying.

Due to the

extreme length of time now taken for deliveries, surface mail is no longer

a viable option and I am unable to offer it even in the case of heavy items.

I am afraid that I cannot make any exceptions to this rule.

|

Payment options for international buyers: |

-

Payment can be made by: credit card (Visa

or MasterCard, but not Amex) or PayPal. I can also accept a cheque in GBP [British

Pounds Sterling] but only if drawn on a major British bank.

-

Regretfully, due to extremely

high conversion charges, I CANNOT accept foreign currency : all payments

must be made in GBP [British Pounds Sterling]. This can be accomplished easily

using a credit card, which I am able to accept as I have a separate,

well-established business, or PayPal.

-

Please contact me with your name and address and payment details within

seven days of the end of the listing; otherwise I reserve the right to

cancel the sale and re-list the item.

-

Finally, this should be an enjoyable experience for

both the buyer and seller and I hope you will find me very easy to deal

with. If you have a question or query about any aspect (shipping,

payment, delivery options and so on), please do not hesitate to contact

me.

Prospective international

buyers should ensure that they are able to provide credit card details or

pay by PayPal within 7 days from the end of the listing (or inform me that

they will be sending a cheque in GBP drawn on a major British bank). Thank you.

|

|

|

|

|

(please note that the

book shown is for illustrative purposes only and forms no part of this

listing)

Book dimensions are given in

inches, to the nearest quarter-inch, in the format width x height.

Please

note that, to differentiate them from soft-covers and paperbacks, modern

hardbacks are still invariably described as being ‘cloth’ when they are, in

fact, predominantly bound in paper-covered boards pressed to resemble cloth. |

|

|

|

|

Fine Books for Fine Minds |

I value your custom (and my

feedback rating) but I am also a bibliophile : I want books to arrive in the

same condition in which they were dispatched. For this reason, all books are

securely wrapped in tissue and a protective covering and are

then posted in a cardboard container. If any book is

significantly not as

described, I will offer a full refund. Unless the

size of the book precludes this, hardback books with a dust-jacket are

usually provided with a clear film protective cover, while

hardback books without a dust-jacket are usually provided with a rigid clear cover.

The Royal Mail, in my experience, offers an excellent service, but things

can occasionally go wrong.

However, I believe it is my responsibility to guarantee delivery.

If any book is lost or damaged in transit, I will offer a full refund.

Thank you for looking.

|

|

|

|

|

Please also

view my other listings for

a range of interesting books

and feel free to contact me if you require any additional information

Design and content © Geoffrey Miller |

|

|

|

|

|