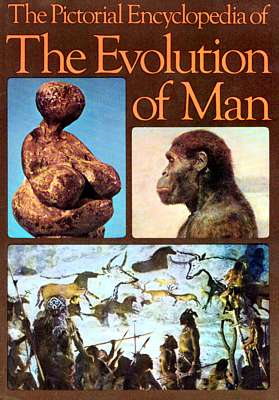

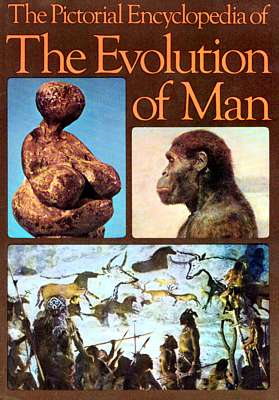

The Pictorial Encyclopedia of The Evolution of Man by J. Jelinek.

NOTE: We have over 100,000 books in our library, over 10,400 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with Dust Jacket: 551 pages. Publisher: The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited; (1975). Size: 8¾ x 6 x 1¾ inches; 2¾ pounds.

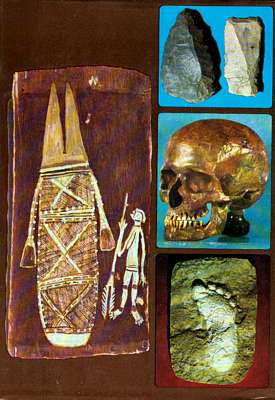

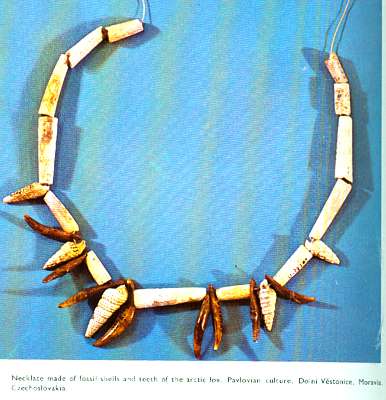

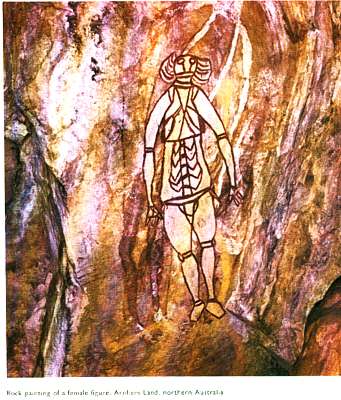

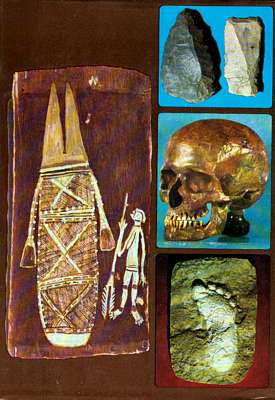

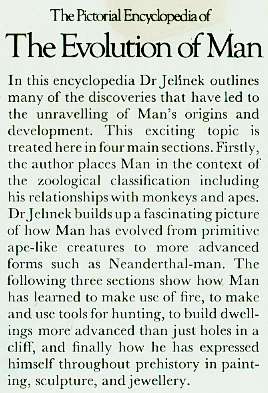

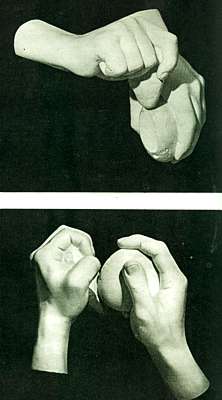

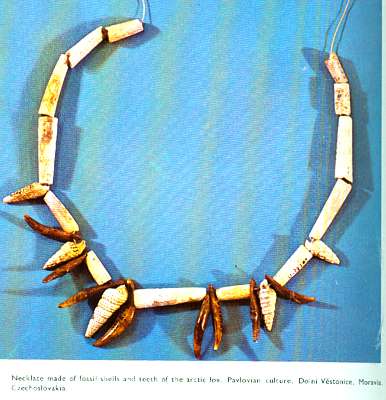

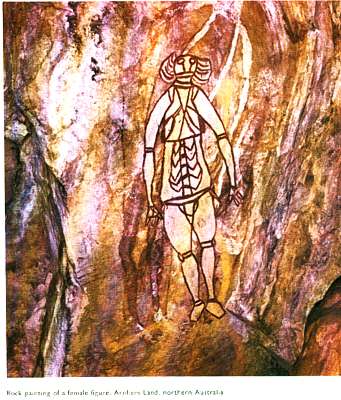

SUMMARY: In this encyclopedia Dr. Jelinek outlines many of the discoveries that have led to the unraveling of Man's origins and development. This exciting topic is treated here in four main sections. Firstly, the author places Man in the context of the zoological classification including his relationships with monkeys and apes. Dr. Jelinek builds up a fascinating picture of how Man has evolved from primitive ape-like creatures to more advanced forms such as Neanderthal-man. The following three sections show how Man has learned to make use of fire, to make and use tools for hunting, to build dwellings more advanced than just holes in a cliff, and finally how he has expressed himself throughout history in painting, sculpture, and jewelry.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. Unread (and in that sense "new" hardcover w/dustjacket. Inside of book is pristine. the inside of the book is pristine. The pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, unambigously unread, tightly bound. Of course the book is almost 50 years old...so it is always possible (even probable) that someone, somewhere, at some time, may have flipped through the book...perhaps looking at the color plates...however there is no compelling evidence of such. From the outside the top surface of the massed closed page edges is ever-so-slightly slightly age-tanned (I guess not totally unexpected given the book is almost 50 years old). Of course this is visible only when book is closed, not to individual pages, only to the mass of closed page edges (sometimes referred to as the "page block"). Moving along, the dustjacket evidences very mild edge and corner shelfwear, principally in the form of very mild crinkling to the dustjacket spine head, spine heel, and the dustjacket's open corners (front and back, top and bottom), or "tips" as they're often referred to. The "tips" of course are formed where the dustjacket folds beneath the covers to form the dustjacket flaps, i.e., the "open corners" of the dustjacket (top and bottom, front and back). And by the way, when we say "very mild", that is precisely what we mean. It really requires that you hold the book up to a light source, tilting it this way and that so as to catch the reflected light, and scrutinize it fairly closely to discern the very mild edge and corner shelfwear to the dustjacket. Beneath the dustjacket the brown full-cloth covers are clean and without any discernible wear, soiling, staining, etc. HOWEVER there is a spot at the spine heel where there's a very small amount of some sort of goo, glue, or some sort of adhesion. It's a very small spot, and perhaps could be removed, but we did not want to risk damaging the cloth covering at the spine heel as the blemish is small and merely superficial/cosmetic...only discerned if one removes the book's dustjacket. Except for this faint cosmetic blemish, and the slightly age-tanned top surface of the massed closed page edges, the overall condition of the book is not too far distant from what might pass as "new" (albeit "shopworn" or "shelfworn") from a traditional brick-and-mortar open-shelf book store (such as Barnes & Noble, Borders, or B. Dalton, for example) wherein otherwise "new" books often show a little handling/shelf/browsing wear simply from routine handling and the ordeal of constantly being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #939w.

PLEASE SEE IMAGES BELOW FOR JACKET DESCRIPTION(S) AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEW:

PUBLISHER REVIEW:

REVIEW: With 860 illustrations in black & white and color. Bibliography. Index.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEW:

REVIEW: Outlines many of the discoveries that have lead to the unraveling of humankind's origins and development. Well illustrated. Includes some stunning photographs of Czech and Ukranian Palaeolithic material and sites. Truly encyclopedic.

READER REVIEW:

REVIEW: Fascinating for the many illustrations of the very rich Paleolithic sites of Eastern Europe, many not seen before in the West. An exceptional account of the rise of the species known as “Man” from varied perspectives. A very thorough and extensively illustrated account. What a magnificent production! Not only a detailed and complete examination of the ascent of mankind, but extremely readable as well. This is truly an epic story told in the grand style.

REVIEW: Not too many books cover the art of early man so this book is very good even for its age.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

STONE AGE HOMININS (PART TWO):

Homo habilis - Homo rudolfensis - Homo ergaster - Homo erectus - Homo antecessor Homo heidelbergensis - Homo neanderthalensis – Homo denisovan – Homo floresiensis - Homo sapiens.

Homo Erectus: Homo erectus or “upright man” is an extinct species of human that occupies an intriguing spot within the human evolutionary lineage. These prehistoric hunter-gatherers were highly successful in adapting to vastly different habitats across the Old World. Fossils connected with this species have been found ranging from Africa all the way to Southeast Asia. The first remains of Homo erectus are dated to around 1.9 million years ago. The latest remains demonstrate that Home erectus survived into the Middle Pleistocene until as late as about 110,000 years ago. The presence of Homo erectus in the story of humans spanned an extraordinarily large time frame.

There is however a very large degree of variation between different fossils from different times and places. This has raised a lot of questions regarding the actual classification of the species. It’s also raised questions as to the exact role Homo erectus played in the evolutionary story of human kind. In the 1890s fossils found at the site of Trinil on Java, Indonesia became the first to be classified as Pithecanthropus (now Homo) erectus. From that point on many more Homo erectus fossils were found in Indonesia and then China. From the 1960s on Homo erectus fossils were also found in Africa.

There is however a very large degree of variation between different fossils from different times and places. This has raised a lot of questions regarding the actual classification of the species. It’s also raised questions as to the exact role Homo erectus played in the evolutionary story of human kind. In the 1890s fossils found at the site of Trinil on Java, Indonesia became the first to be classified as Pithecanthropus (now Homo) erectus. From that point on many more Homo erectus fossils were found in Indonesia and then China. From the 1960s on Homo erectus fossils were also found in Africa.

They most likely descended from an earlier species of Homo in East Africa or possibly Eurasia. That earlier species is thought by most anthropologists to be Homo habilis. Some part of this very widely spread species is thought to have given rise to later species such as Homo heidelbergensis. Homo heidelbergensis are believed by anthropologists to be directly connected to our own species, Homo sapiens. However the fact is that the fossils that have been assigned to Homo erectus span an almost ridiculous amount of both time and space. They also show huge variations when they are all taken together.

These issues are very problematic. The question is whether they can actually be classified as one coherent species? Or are they fossils of multiple, distinct species? A fact which should be classified a bit more narrowly? Perhaps there are more than one species making up the fossil record attributed to Homo erectus. There are on one hand those researchers who argue for a broad single-species model. They propose the classification of “Homo erectus sensu lato”. This classification would encompass all or almost all fossils from Southeast Asia to Africa that have been chucked into this group so far.

From this point of view the variation falls within the range of an otherwise cohesive species. The variation might be due to the adventurous, globe-trotting nature of this species. With time and space regional environmental factors impacted their physiques. This broad definition is a little too convenient however. It becomes tempting to toss every new fossil find that seems to vaguely match the characteristics of Homo erectus in with this bunch. This is obviously not necessarily an ideal way or precise classification methodology.

On the other hand a narrower definition has been suggested that excludes either all of the African fossils, or at least the portion found at Koobi. The justification offered is based on the fact that the fossils are significantly different than Homo erectus. The differences might be significant and consistent enough to be named Homo ergaster. Ergaster is then seen as the species that is linked with the lineage leading to Homo sapiens. Homo erectus sensu stricto (in the strict sense, so only the Asian part) may have been a dead end.

On the other hand a narrower definition has been suggested that excludes either all of the African fossils, or at least the portion found at Koobi. The justification offered is based on the fact that the fossils are significantly different than Homo erectus. The differences might be significant and consistent enough to be named Homo ergaster. Ergaster is then seen as the species that is linked with the lineage leading to Homo sapiens. Homo erectus sensu stricto (in the strict sense, so only the Asian part) may have been a dead end.

This debate will without a doubt continue to rage for some time yet. It’s most likely that we just do not have all the pieces of the puzzle that are needed to disentangle this morass. At the moment the general consensus amongst researchers seems to be that the characteristics of the fossils do not present enough evidence to overturn the single-species hypothesis. So a single-species fossil origin of Homo erectus in the broad sense prevails. Fossils assigned to the broad definition of Homo erectus are found all the way from Southeast Asia to Africa. Areas and sites include Trinil on Java, Indonesia; and China (where the fossils were known as ‘Peking Man’). Eurasian sites include Georgia. There the finds at Dmanisi are so puzzling they seem to blur the lines between Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, and Homo erectus. The fossils might even end up qualifying as a distinct species, “Homo georgicus”.

Homo erectus sites in East Africa include for instance Olduvai Gorge and in the Turkana Basin in Kenya. There are additional sites as well in North and South Africa. Some finds in Western Europe have also at some point in time been lumped into Homo erectus. However there is now fairly broad agreement that most of these forms are better matches with Homo heidelbergensis. Homo erectus is generally thought to have started their migration out of Africa around 1.9-1.8 million years ago. This marathon led them through the Middle East, the Caucasus and eventually East Asia. They reached Indonesia and China by about 1.7 to 1.6 million years ago. But what spurred them on?

A 2016 study developed a model that suggests that Homo erectus followed the large herbivores during their dispersal. However at least early on they also tried to actively avoid areas densely populated by carnivores. They also seemed to prefer and select areas with flint deposits. Homo erectus pops up more or less around the same time in East Africa and Eurasia. Consequently there is a chance that their origins lay in Eurasia rather than East Africa. This could help explain the presence of Homo floresiensis in Indonesia, which has erectus-like traits. Either way, they spread very rapidly across the globe.

Homo erectus was both bigger and smarter than earlier humans. Their skeletons were basically pretty similar to ours. Their physique was essentially modern, although they were stockier. They were the first humans to have limb and torso proportions along modern human lines. This allowed them to walk upright on two feet, hence the name “erectus”. They not only walked upright, they literally trotted the globe. However they had lost the climbing adaptations that allowed earlier humans to play Tarzan.

Homo erectus was both bigger and smarter than earlier humans. Their skeletons were basically pretty similar to ours. Their physique was essentially modern, although they were stockier. They were the first humans to have limb and torso proportions along modern human lines. This allowed them to walk upright on two feet, hence the name “erectus”. They not only walked upright, they literally trotted the globe. However they had lost the climbing adaptations that allowed earlier humans to play Tarzan.

Some of these humans were very tall. The African-based Homo erectus population reached an average height of 67 inches (5 feet, 7 inches). However much like with our current-day populations, Homo erectus showed a lot of variation in size from one region to the next. Homo erectus populations ranged between roughly 57 to 73 inches (4 feet, 9 inches to 6 feet, 1 inch). Weight typically ranged from 88 to 150 pounds. Even on the shorter end of the scale Homo erectus was significantly taller relative to earlier humans. The famous Australopithecus afarensis “Lucy” was only 43 inches (3 feet, 7 inches) tall.

Homo erectus not only had a visibly bigger brain than those species of Homo before them. Early members of Homo erectus had cranial capacities between 600-800 cubic centimeters. This was considerably larger than their predecessor Homo habilis, who maxed out around 600 cubic centimeters. Not only did the brain of Homo erectus outclass its predecessors, the cranial capacity grew larger as time went by. Most later Homo erectus exceeded 1000 cubic centimeters cranial capacity. This falls within the lower range seen in our own species.

Homo erectus had heavy brow ridges and a low cranial vault. This resulted in the appearance of a more sloping head without a real forehead). Their teeth were already a lot smaller and more slender than those of earlier humans. To survive Homo erectus groups followed the hunter-gatherer model. It took a lot more food to feed their larger bodies and larger brains. But their increased brain size also helped them be smart about the way they procured their meals. Based on their success and longevity this was clearly a win-win situation. It seems they ate a diverse and broad diet, Their diet perhaps including tubers, but it definitely included a substantial amount of meat.

Animal remains with clear cut marks left by butchery have been found in connection with Homo erectus. The evidence demonstrates that they regularly accessed animal carcasses from at least 1.75 million years ago. Their meat probably came through both scavenging and hunting. It is likely that Homo erectus knew and used fire. The earliest evidence for the use of hominin fire dates back to around 1.8 million years ago. From at least 500,000 years ago cooking began becoming commonplace. By 400,000 years ago human species were visibly and deliberately handling fire. This was well within Homo erectus’ time span.

Animal remains with clear cut marks left by butchery have been found in connection with Homo erectus. The evidence demonstrates that they regularly accessed animal carcasses from at least 1.75 million years ago. Their meat probably came through both scavenging and hunting. It is likely that Homo erectus knew and used fire. The earliest evidence for the use of hominin fire dates back to around 1.8 million years ago. From at least 500,000 years ago cooking began becoming commonplace. By 400,000 years ago human species were visibly and deliberately handling fire. This was well within Homo erectus’ time span.

Hearths lit up the living spaces of these societies. Fire provided a means for cooking food and thus increasing the available nutrients and energy available from that food. However fire also provided warmth, protection from predators, and a conductive good hub for social interaction. Natural shelters dominated the domiciles of Homo erectus. Among these dwelling forms were overhanging cliffs and the highly popular caves. An apt toolmaker, Homo erectus is associated with the Oldowan Stone Age Tool Technology. But the association with the Acheulean stone tool industry was actually more commonplace. Homo erectus is often connected with the creation of the very first hand-axes.

The development of hand axes was the first major innovation in stone tool technology. A broader set of tools would have helped Homo erectus survive across a wide range of environments. When it comes to picturing a group of Homo erectus around a hearth feasting on a bison steak we cannot tell whether there would have been a proper dinner table conversation or not. Some social element must have been present. But language is a tough one to pin down. Anatomical clues cannot prove or disprove the ability for language or some sort of human-like proto-language.

Since there is no genetic material available for them, scientists cannot test for the FOXP2 gene. The FOXP2 gene is associated with language production in humans. It is found in both the later Neanderthals and Denisovans. All in all it is clear that Homo erectus provided a huge step forward with respect to the development of the human lineage. Homo erectus may well have been the earliest species within this lineage to show so many human-like characteristics [Ancient History Encylopedia].

Homo antecessor: Homo antecessor is an archaic human species of the Lower Paleolithic. Homo antecessor is known to have been present in Western Europe (Spain, England and France) between about 1.2 million and 0.8 million years ago. Homo antecessor was described in 1997 as a "unique mix of modern and primitive traits" when it was classified as a previously unknown archaic human species. The fossils associated with Homo antecessor represent the oldest direct fossil record of the presence of Homo in Europe. The species name antecessor proposed in 1997 is a Latin word meaning "predecessor". Researchers who do not accept Homo antecessor as a separate species consider the fossils to be an early form of Homo heidelbergensis or a European variety of Homo erectus.

Homo antecessor: Homo antecessor is an archaic human species of the Lower Paleolithic. Homo antecessor is known to have been present in Western Europe (Spain, England and France) between about 1.2 million and 0.8 million years ago. Homo antecessor was described in 1997 as a "unique mix of modern and primitive traits" when it was classified as a previously unknown archaic human species. The fossils associated with Homo antecessor represent the oldest direct fossil record of the presence of Homo in Europe. The species name antecessor proposed in 1997 is a Latin word meaning "predecessor". Researchers who do not accept Homo antecessor as a separate species consider the fossils to be an early form of Homo heidelbergensis or a European variety of Homo erectus.

Homo antecessor was discovered in 1991 in the Gran Dolina site of the Sierra de Atapuerca region of northern Spain. These remains were deposited about 780,000 years ago, making them the oldest European human fossils. Stone tools indicate hominin activity in Europe as early as 1.6 million years ago in Eastern Europe and Spain. The sediment of Gran Dolina was dated at 900,000 years old in 2014. More than 80 bone fragments from six individuals were uncovered in 1994 and 1995. The site also had included approximately 200 stone tools and 300 animal bones. Stone tools including a stone carved knife were found along with the ancient hominin remains.

All these remains were dated at least 900,000 years old. The best preserved specimens are a frontal bone and a maxilla (upper jawbone) of a 10 year old boy. Dubbed the "Gran Dolina Boy" his remains date to 859,000 to 782,000 years ago. In 2007 a molar dating to 1.2–1.1 million years ago was recovered from the nearby Sima del Elefante site. It belonged to a 20 to 25 year old individual. In 2008 an additional mandible fragment, stone flakes, and evidence of butchery were discovered. At the time these were the oldest human fossils known from Europe. That was until 2013 with the discovery of a 1.4 million year old infant tooth from Barranco León, Orce, Spain.

Evidence of early human presence in England and France has been tentatively associated with Homo antecessor purely on chronological grounds and not based on archaeological evidence. Fifty footprints dating to between 1.2 million and 800,000 years ago were discovered in Happisburgh, England. They were possibly made by an Homo antecessor group. Homo antecessor has been proposed as a chronospecies. It is postulated that Homo antecessor was intermediate between Homo erectus who existed from about 1.9 to 1.4 million years ago, and Homo heidelbergensis who existed between 0.8 and 0.3 million years ago.

Homo heidelbergensis is widely accepted as the immediate predecessor of Homo neanderthalensis and possibly Homo sapiens. However the origin of Homo heidelbergensis from Homo antecessor is debatable. The discovery of Homo antecessor suggested Homo antecessor originated with African Homo erectus (Homo ergaster). It was postulated that Homo ergaster would have migrated to the Iberian Peninsula at some point before 1.2 million years ago. Then Homo ergaster would have developed into Homo heidelbergensis by 0.8 million years ago. A further development would have been Homo neanderthalensis after 0.3 million years ago.

Homo heidelbergensis is widely accepted as the immediate predecessor of Homo neanderthalensis and possibly Homo sapiens. However the origin of Homo heidelbergensis from Homo antecessor is debatable. The discovery of Homo antecessor suggested Homo antecessor originated with African Homo erectus (Homo ergaster). It was postulated that Homo ergaster would have migrated to the Iberian Peninsula at some point before 1.2 million years ago. Then Homo ergaster would have developed into Homo heidelbergensis by 0.8 million years ago. A further development would have been Homo neanderthalensis after 0.3 million years ago.

In 2009 palaeoanthropologists expressed skepticism over the suggestion that Homo antecessor was ancestral to Homo heidelbergensis. Rather the group interpreted Homo antecessor as a "failed attempt to colonize southern Europe". The legitimacy of Homo antecessor as a separate species has also been questioned because the fossil record is fragmentary. This is especially true as no complete skull has been found. Thus far only fourteen fragments and a lower jaw bone are known. Because of this it has also been proposed that Homo antecessor was an early form of Homo heidelbergensis.

This would have the effect of expanding the horizon on Homo heidelbergensis to 1.2 to 0.3 million years ago rather than the generally accept 0.8 to 0.3 million years ago. A 2020 analysis of ancient proteins collected from a tooth of an Homo antecessor specimen indicated that Homo antecessor belonged to a "sister lineage" related to the ancestor of modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans. However the analysis indicated that Homo antecessor was not itself their direct ancestor. This corroborated earlier assessments that Homo heidelbergensis was not derived from Homo antecessor.

Based on fossil radial and clavicle lengths the statures of two Homo antecessor specimens were calculated to be 5 feet, 9 inches and 5 feet, 7 inches. The body proportions of Homo antecessor fall within the range of variation for modern humans. The upper limb proportions seem to have been more similar to those of modern humans than Neanderthals. The facial anatomy of the Boy of Gran Dolina appears very similar to that of modern humans. It has been suggested that this marked the beginning of modern human facial features. These features likely did not change so drastically with age.

However modern humanlike facial features may have evolved multiple times independently among different human lineages. Based on teeth eruption pattern the researchers think that Homo antecessor had the same development stages as Homo sapiens, though probably at a faster pace. Other significant features demonstrated by the species are a protruding occipital bun, a low forehead, and a lack of a strong chin. Some of the remains are almost indistinguishable from the fossil attributable to the 1.5-million-year-old Turkana Boy, belonging to Homo ergaster.

However modern humanlike facial features may have evolved multiple times independently among different human lineages. Based on teeth eruption pattern the researchers think that Homo antecessor had the same development stages as Homo sapiens, though probably at a faster pace. Other significant features demonstrated by the species are a protruding occipital bun, a low forehead, and a lack of a strong chin. Some of the remains are almost indistinguishable from the fossil attributable to the 1.5-million-year-old Turkana Boy, belonging to Homo ergaster.

The large animal carcasses at Gran Dolina appear to have been carried to the site intact. This indicates that Homo antecessor groups dispatched multi-member hunting parties. These hunting parties delayed eating the game immediately after a successful kill. Rather they hauled it back in order to share it with all group members. This clearly demonstrates social cooperation, division of labor, and food sharing. The fossilized bones of 16 game species were recorded from Gran Dolina, presumably slaughtered and consumed. They included the bush-antlered deer, an extinct species of fallow deer, an extinct red deer, an extinct bison, a wild boar, the rhino Stephanorhinus etruscus, the Stenon zebra, a mammoth, the Mosbach wolf, the fox Vulpes praeglacialis, the Gran Dolina bear, the spotted hyena, and a lynx.

The most common butchered remains are those of deer. Also adult and child Homo antecessor specimens from Gran Dolina exhibit cut marks, crushing, burning, and other trauma indicative of cannibalism. These human remains are the second-most common bearing evidence of butchering. It is unclear if cannibalism was practiced often (ritual cannibalism), or if these buttered bones represented an isolated incident in a dire situation (survival cannibalism) [Wikipedia].

Homo heidelbergensis: Homo heidelbergensis is an extinct species of human that is identified in both Africa and western Eurasia. The species existed from roughly 700,000 years ago onwards until around 200,000 years ago, fitting snugly within the Middle Pleistocene. Homo heidelbergensis is named for a piece of jawbone found near Heidelberg, Germany. Homo heidelbergensis occupies an intriguing and much-discussed spot in the jumble of human evolution.

Most scholars believe that Homo heidelbergensis developed from Homo erectus. Further that Homo heidelbergensis gave rise to Homo sapiens in Africa and to the Neanderthals in Europe. However exactly how or why (and even if) this happened is the subject of much debate. Likewise the precise definition of this species is also subject to debate. For instance which fossils should be included and which should not is still a contentious subject. However in general Homo heidelbergensis is widely recognized as a distinct species. Likewise there is general agreement that it was a bit more brainy and inventive than its predecessors.

Most scholars believe that Homo heidelbergensis developed from Homo erectus. Further that Homo heidelbergensis gave rise to Homo sapiens in Africa and to the Neanderthals in Europe. However exactly how or why (and even if) this happened is the subject of much debate. Likewise the precise definition of this species is also subject to debate. For instance which fossils should be included and which should not is still a contentious subject. However in general Homo heidelbergensis is widely recognized as a distinct species. Likewise there is general agreement that it was a bit more brainy and inventive than its predecessors.

Fairly complex tools are associated with Homo heidelbergensis. This allows us to catch a glimpse of possibly quite daring hunting strategies involving larger prey animals. This in turn hints at the potential presence of significant degrees of social cooperation. Homo heidelbergensis was first discovered in 1907 at the Grafenrain sandpit at the site of Mauer, near Heidelberg, Germany. The site became somewhat of a sensation as a robustly built jawbone of a previously unknown species of human was discovered there. Researchers realized that it had both some more primitive features as well as bits that reminded them of more recent human features.

In the year following the discovery the fossilized remains were classified as a distinct species which was named Homo heidelbergensis. The jawbone has recently been dated to an age of around 600,000 years ago, which falls within the MIS 15 interglacial period. This indicates that its owner would not have instantly frozen solid upon reaching this region. If one was to stroll into a Middle Pleistocene cave inhabited by an average group of Homo heidelbergensis individuals, they would probably strike one as somewhat chunkier versions of ourselves. They were noticeably more robust than modern humans.

However their brain size almost approached our own. It average perhaps somewhere around 1200 cubic centimeters, perhaps even more. That was markedly bigger than that of Homo erectus (about 1,000 cubic centimeters) or Homo habilis (about 600 cubic centimeters). Heidelbergensis still had quite heavily construction, broad faces reminiscent of Homo erectus. However their brow ridges were less pronounced and their noses were more vertical like ours are, instead of sloping forward like those of Erectus. A skull from Bodo, Ethiopia was dated to approximately 600,000 years ago. It proved to be a good example of this mix of characteristics.

The skull was clearly related to other Heidelbergensis fossils found in Africa. This would include fossils such as those from Broken Hill in Zambia; Elandsfontein in South Africa; and Lake Ndutu in Tanzania. However it was also clearly related to fossils from Europe. These would include those from Petralona in Greece, Arago in France, and the mandible from Mauer, Germany. Once the Middle Pleistocene fossil record decides to be a bit more generous, we may be able to more directly visualize the proposed development from Heidelbergensis into Sapiens in Africa and into Neanderthals in Europe.

The skull was clearly related to other Heidelbergensis fossils found in Africa. This would include fossils such as those from Broken Hill in Zambia; Elandsfontein in South Africa; and Lake Ndutu in Tanzania. However it was also clearly related to fossils from Europe. These would include those from Petralona in Greece, Arago in France, and the mandible from Mauer, Germany. Once the Middle Pleistocene fossil record decides to be a bit more generous, we may be able to more directly visualize the proposed development from Heidelbergensis into Sapiens in Africa and into Neanderthals in Europe.

One possible example is a fossil which originated from the site of Boxgrove in England. The fossil is usually classified as Homo heidelbergensis and is thought to be around 500,000 years old. The tibia found there shows it was more robust than average Heidelbergensis specimens and indicates body proportions that were better adapted to the cold. This characteristics foreshadowed the features of the later Neanderthals. Were the fossil record more complete, the connection could be more certain.

Homo heidelbergensis were hunter-gatherers. Some of them were well-adapted to the generally more stable and warm African terrain. Another branch adapted to the cyclically growing and receding ice sheets and climate of various regions in Europe along with. Obviously these bands would not have shared the exact same customs and characteristics. However from the record we can still gain something of a general picture, with some splashes of regional color added. Part of this general picture involves Heidelbergensis coming home from a fruitful hunt and sticking the day’s catch over a neat fire.

Preferred real estate came in the shape of caves. During the Middle Pleistocene hominin-inhabited caves became both more spatially structured and dotted with hearths. An incidental use of fire had been around since at least 1.8 million years ago. However fire still remained a rare sight up until the days of Homo heidelbergensis. During its time on our little planet, Heidelbergensis became ever more accustomed to fire and its use for cooking food. The archaeological record indicates that by at least around 400,000 years ago humans clearly used fire in a habitual way. This particularly included the colder north, where it was particularly useful as a source of warmth.

Fire is a clear indication of a more advanced sort of lifestyle. This image is further supported by the tools manufactured and used by Homo heidelbergensis. Their tool kits were more sophisticated than that of Homo erectus. Whereas the tool kit of Homo erectus belonged to the early Acheulean, the tool kit of Homo heidelbergensis clearly was a product of the later Acheulean industry. In general the Acheulean was characterized by large bifaced stone tools such as like hand axes, picks and cleavers. Later Acheulean tools were thinner, more finely flaked, and more symmetrical.

Fire is a clear indication of a more advanced sort of lifestyle. This image is further supported by the tools manufactured and used by Homo heidelbergensis. Their tool kits were more sophisticated than that of Homo erectus. Whereas the tool kit of Homo erectus belonged to the early Acheulean, the tool kit of Homo heidelbergensis clearly was a product of the later Acheulean industry. In general the Acheulean was characterized by large bifaced stone tools such as like hand axes, picks and cleavers. Later Acheulean tools were thinner, more finely flaked, and more symmetrical.

The tools created by Homo heidelbergensis allowed them to process their food and work raw materials. This enabled them to become adept hunters climbing further up the food chain. The archaeological record seems to confirm this. At the site of Boxgrove in England thin and extensively flaked flint bifaces have been found. Dated to around 500,000 years ago, they were found together with the remains of horses and rhinoceroses. The animal bones bear cut marks. This evidence indicates that these large animals were killed and butchered by Heidelbergensis.

At Schöningen in Germany providence brought even more remarkable finds. Eight skillfully crafted wooden throwing spears were found. They were produced at least 300,000 years ago. The remains of numerous horses found in the immediate vicinity as well. Many of their bones were cut-marked. This remarkable find correlates with the finds at Boxgrove. The evidence indicates that Heidelbergensis systematically hunted large animals. This was no easy feat. The production of the spears shows active planning. Bringing down these dangerous animals would have required coordination and sophisticated communication.

The backdrop for these activities suggests a social structure that may well have been both complex and widespread. Although wood does not usually stand the test of time very well, the Schöningen spears were technically remarkably advanced. Though finding such remarkably well preserved wooden tools is not something likely to be repeated, Heidelbergensis’ stone tools do stand the test of time well and so are well represented in the archaeological record. As with the Schöningen wooden spears, those stone tools show a similarly advanced nature across their entire range.

Unless this specific region was somehow unique in its development, wooden tools could have made up an important part of these people’s prehistoric tool kits. If that were indeed the case, the social implications that have been suggested for the site of Schöningen are assumed to be valid across the breadth of the species. Time may yet reveal more archaeological evidence to shed light on this matter.

It can sometimes be hard to confidently lump an ambiguous fossil into species such as Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or the Neanderthals. Inasmuch as such ambiguous fossils are many, researchers have come up with all sorts of scenarios describing the place of Heidelbergensis within evolution. Sometimes Heidelbergensis is dismissed altogether in favor of being classified within a more broadly defined Homo erectus. Sometimes Heidelbergensis is presented as an exclusively European lineage giving rise to the Neanderthals. The more complex fossils associated with Heidelbergensis seem to defy any kind of common consensus amongst researchers.

It can sometimes be hard to confidently lump an ambiguous fossil into species such as Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or the Neanderthals. Inasmuch as such ambiguous fossils are many, researchers have come up with all sorts of scenarios describing the place of Heidelbergensis within evolution. Sometimes Heidelbergensis is dismissed altogether in favor of being classified within a more broadly defined Homo erectus. Sometimes Heidelbergensis is presented as an exclusively European lineage giving rise to the Neanderthals. The more complex fossils associated with Heidelbergensis seem to defy any kind of common consensus amongst researchers.

However, so far the scenario best supported by both the anatomical and the genetic evidence, of which the general lines (although not always the details) are favored by most people, is as follows. Around 700,000 years ago (and perhaps as early as 780,000 years ago), Homo heidelbergensis had developed from Homo erectus. In Africa around roughly 200,000 years ago they were part of a gradual, mosaic-like transition into the earliest Homo sapiens. Finds from sites such as Omo Kibish, Ethiopia; Irhoud in Morocco; and Herto in the Middle Awash region seem to showcase this transition.

Populations of Heidelbergensis also spread through western Eurasia, appearing north of the major mountains of Europe sometime after 700,000 years ago. Clearly adapting well to the challenging environment, the cold conditions led them to evolve the specialized facial features and more stocky build of the Neanderthals, to whom they gave rise and who appear with clear and recognizable features from roughly 200,000 onwards. Of course, with this being a gradual process, the proposed timing is subject to a lot of bickering.

There is another group that also derives from Heidelbergensis though. In 2008 a human finger bone was found in the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in Siberia. The discovery that turned out to belong to a separate species dubbed the Denisovans. Genetic evidence has since revealed that they are a sister species to the Neanderthals. Denisovan and Neanderthal diverged at some point after Homo sapiens and Neanderthal had already split from Homo.

The addition of Denisovan to the Homo heidelbergensis progenitor line-up makes it even clearer how complex an evolutionary story the Pleistocene really tells. Another confusing example is the fossils at the site of Sima de los Huesos in Spain. Generally grouped within Homo heidelbergensis, these fossils are between about 430,000 years and 530,000 years old. At this point in time they already exhibited some Neanderthal-like features.

The addition of Denisovan to the Homo heidelbergensis progenitor line-up makes it even clearer how complex an evolutionary story the Pleistocene really tells. Another confusing example is the fossils at the site of Sima de los Huesos in Spain. Generally grouped within Homo heidelbergensis, these fossils are between about 430,000 years and 530,000 years old. At this point in time they already exhibited some Neanderthal-like features.

These characteristics energized a debate over the merits of classifying them as proto-Neanderthals. That would be a classification distinct from Homo heidelbergensis. It would be a classification of Heidelbergensis on their way to eventually becoming Neanderthals. In 2014 mitochondrial DNA was retrieved from one of these Sima fossils. The DNA showed that the fossils were closely related to the lineage leading to the Denisovans, the sister group to the Neanderthals. It is clear that the Pleistocene was home to a complex story of human evolution [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Homo Naledi: Homo naledi is an extinct species of human discovered in Rising Star Cave in South Africa in 2013. The discovery has become the biggest single-species hominin find in Africa to present day. The discovery has also caused a bit of an avalanche within the field of palaeoanthropology. This is due first because the skeletal remains possesses such a strange mix of features. Second Homo naledi is a recent hominin. The dating of only 236,000 to 335,000 years serves to highlight the incredible and recent realization of how wide hominin variety has been in the recent past.

More than 1500 fossils that once belonged to at least 15 individuals were painstakingly removed from a very inaccessible part of the cave. The project presented its results in open access fashion. The world was allowed to watch over the researchers shoulders as social media and a live blog by National Geographic kept track of the excavation process. Homo naledi were short and small. They possessed small skulls. Skeletal remains showed a mixture of features. Some features resembled the Australopithecines. Other features were more humanlike such as the hands and feet.

Up until recently scientists had not managed to date these bones. The strange, mixed features suggested by the bones led to a wide span of possibilities. Some of the proposed dates pointed to some of Homo naledi’s more archaic features and postulated an age of around two million years old. However a paper published in 2017 by members involved in the excavations finally succeeded in dating the remains. They are only between 236,000 and 335,000 years old. This was much, much younger than most researchers imagined. Naledi thus shared Africa with modern human ancestors who were also trudging around at that time.

The confirmed dating points out that even for experts skeletal characteristics alone are not an entirely reliable way of estimating a fossil’s age. This is especially true if such an assessment is based only on fragmentary remains. This experience also suggests that a reassessment of other early hominin fossils might also be in order.

The confirmed dating points out that even for experts skeletal characteristics alone are not an entirely reliable way of estimating a fossil’s age. This is especially true if such an assessment is based only on fragmentary remains. This experience also suggests that a reassessment of other early hominin fossils might also be in order.

In 2013 a palaeontologists along with some former students and palaeontological enthusiasts struck bone when they were exploring a cave system chamber some 100 feet below ground level. The chamber was a very narrow squeeze, but the paleontologist’s 14 year old son was slender enough to fit. He photographed the bones and showed his dad, who confirmed they were indeed human. Not long after the start of the excavations several of the students followed a sloping passage into another section of the cave. They followed more than 100 yards of twists and turns leading them away from the first chamber. They two student thereupon stumbled onto even more bones.

The first chamber was eventually named Dinaledi ('stars' in Sesotho). The second chamber was named Lesedi ('light' in Setswana). To reach the Dinaledi chamber, one had to overcome an obstacle course which would have made any military obstacle course proud. After entering one must first descend along a narrow, downward-winding passage, squeezing between the rocks. Then after climbing down a ladder (installed for the purpose of the dig), the first choke point is reached. It is known as “Superman’s Crawl”. For 25 feet you must crawl through a narrow tunnel with one arm extended over your heads to get through.

The reward is an area without serious obstacle, which is followed by what the archaeological team named “Dragon’s Back”. This is a 65 foot long ascent marked by a series of scale-like flat rocks jagging upward. A three foot wide gap then has to be crossed before reaching the 7½ inch (18 cm) wide slot that forms the entrance into the chamber more than 165 feet below. With these conditions in mind any kind of body fat would likely leave you permanently sandwiched between the rock walls.

The team found it necessary to send out a Facebook “casting call” for experienced palaeontologists who were skinny and not claustrophobic. The six that were chosen to do the excavation work happened to be all women. They became known as the “underground astronauts”. The two chambers were basically littered with bones, probably not all of which have even at this late stage yet been recovered. The bones of the Dinaledi chamber originated with at least 15 individuals. The bones in the Lesedi chamber are as yet undated. They appear to be two adults and a juvenile. All of the bones in both chambers belonged to Homo naledi.

Homo Naledi’s eclectic collection of features is overturning the way we thought species worked and our linear view of human evolution. They were small humans, with one of the adult individuals estimated to have been around 57 inches tall (less than 5 feet). They were taller than Australopithecus but not as tall as Homo erectus. The average estimated weight comes in around 88 to 123 pounds. Their skulls were small as well, averaging between 465 and 560 cubic centimeters (modern humans average around 1400 cubic centimeters). The skull found in the Lesedi chamber was slightly larger at 610 cubic centimeters, roughly comparable to Australopithecus brains.

However Australopithecus lived 2 to 3 million years before Homo naledi. By evolutionary standards the brain of Homo naledi was very small. On the other hand Naledi’s skull shape, including the jaw and teeth, looks like that of early Homo species such as Erectus, Habilis or Rudolfensis. The human trend is continued in their nimble hands (with remarkably curved fingers) and wrists, the spine, and very human-like foot and lower limb. Again however in confusing contrast are Homo naledi’s flaring pelvis, wide ribcage and shoulders. These last characteristics are again more similar to Australopithecus.

They clearly walked upright and had hands dexterous enough to theoretically smash out some tools, though none have been found in the cave. They also possessed a Homo-esque skull shape with small teeth. Those characteristics combined with their assumed lifestyle pushes them into the genus Homo rather than Australopithecus. But where do Homo naledi’s origins lie? The archaeological team believes its branch within the hominin tree must be at least 900,000 years old, and probably even older. The team postulates three possible origin stories.

He first possibility is that their origins may lie somewhere along the confusing tangle of branches that also led to Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, Homo floresiensis, and Australopithecus sediba. The second possibility is that they may be a sister group to Homo erectus and other big-headed members of the Homo family, which includes ourselves (Homo sapiens). A final third possibility is that there might be a sisterly connection with a-yet-unidentified group that spans (connects) Homo sapiens, Homo antecessor, and other archaic humans. Naledi’s mosaic anatomy might be the result of a early mixing of an Australopith and a more human-like population. The Australopith may have been a particularly stubborn line which survived until a later point than most other Australopith lines, with Naledi sticking around for ages after this early hybridization (or cross-breeding).

Naledi’s bones suggest that these humans were probably not very original with regard to their lifestyle. Evidence suggests that they clambered about their environment in a manner similar to Sapiens and Erectus. A recent study found small chips in Naledi’s teeth. It seems likely their diet may have included chewing on tough foods, perhaps contaminated with grit. Aiding their teeth Homo naledi’s hands show it could at least theoretically have played with tools which could have played a role in processing food. However no tools have been discovered in the Rising Star Cave as of yet.

The dating of the bones was truly shocking at between 236,000-335,000 years old. It may thus even be the only human discovered so far that to our knowledge was actually around in South Africa at that time when Middle Stone Age tools were created in that region. What is unfathomable is the enigma of how on earth these bones ended up in such a weirdly inaccessible part of the cave. Research has shown that the Dinaledi chamber was most likely just as hard to reach back in Naledi’s day. The lack of sudden openings means it was not some sort of death trap into which people tumbled to their demise.

The cave’s sediment tells us there is also no evidence of the bones being moved from one part of the cave to another by a rush of water. The bones moreover show no sign of being gnawed up by predators or cut-marked by other humans who might have dragged them into the cave. The material recovered from the Lesedi chamber ties in with all of this as well. The only reasonable explanation seems to be that these people were intentionally buried. Whether or not these burials came from a symbolic background is unknown. Reasons for burial can be of a large variety The motivation could be simply wanting to stick rotting bodies far away from your dinner table as possible. By so doing you ensure to make sure curious cave lions do not show up as uninvited dinner guests. There can also be motivations of more social and symbolic origin.

Homo naledi’s recent date is a bit of an eye-opener in the context of human evolution at that point in time. It has overturned the previously widespread idea that humans showing these sorts of primitive features did not survive anywhere near this long. It also helps explain the recent discovery of Homo floresiensis discovered in 2003 in Indonesia (the “hobbit people”), who only died out about 12,000 years ago. It also means that researchers cannot reliably stick a date on a species if only certain parts of the skeleton have been found. If only Naledi’s shoulders and ribcage had been found and none of its more human-like features, the tentative date resumed may have been concurrent with Australopithecus.

A reassessment of old fossils dated solely by the features of recovered skeletal bits and pieces may not be a bad idea. It is now clear that several quite distinct human populations were trudging around tropical and subequatorial Africa, with different-looking humans overlapping in time. Diversity is thus clearly a very, very important word in the evolutionary journey of Homo [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Homo neanderthalensis: Neanderthals are an extinct group of fossil humans that appeared in Western Eurasia in the Mid-Middle Pleistocene. They shared the stage with the first modern humans arriving in Europe from around 45,000 years ago. Neanderthals disappeared from the fossil record around 40,000 years ago. Neanderthals were a highly successful group. They had adapted well to the unpredictable climate of a region in which advancing and retreating ice sheets were constant. Their short, stocky build made them sturdy and powerful. Their large brains fuelled their capability of hunting even the biggest Ice Age creatures such as mammoths or woolly rhinoceros.

We modern humans are tied to Neanderthals in many ways. We share a common African ancestor from between about 550,000 to 750,000 years ago. We co-existed in Europe for tens of thousands of years. We must have competed with Neanderthal resources, but it is also known that we interbred with Neanderthals. Thus Neanderthals even had a genetic impact on us still visible in our DNA today. Another human species, the Denisovans are tied to the Neanderthals even more closely than modern humans are.

Denisovans and Neanderthals are two sister groups that diverged from a common ancestor perhaps between 430,000 and 473,000 years ago. That split from Neanderthals and Denisovans occurred later than the split from Neanderthals to modern human. The Denisovans are so far only known from Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in Siberia. Neanderthal remains have also been found at the site. The most astonishing discovery made there came in 2012. A long bone fragment dated to between 80,000 and 120,000 years old was found that belonged to a female who had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. This was direct evidence of the fact that in addition to modern man (homo Sapiens) Neanderthals also interbred with the Denisovans.

The first Neanderthal fossils were dug up in the early 19th century included the “Engis Child” in 1830 and the “Forbes Quarry Adult” in 1848. They were not immediately recognized as a kind of archaic human. The peculiar anatomy of the skeleton clearly differed from modern humans. However this peculiar anatomy was explained away as resulting from a disease such as rickets. However a skeleton was discovered in the Neander Valley in Germany in 1856. The subsequent research was influenced by the 1859 publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859. By 1864 the mysterious skeletons had been assigned to the species Homo neanderthalensis.

The process of evolution adds to the complication of classifying species. So there is no clear-cut date for the initial appearance of Neanderthals. Rather it is recognized that the first Neanderthal-like features appeared between about 600,000 to 400,000 years ago. The morphology of Neanderthal was more strongly expressed as time progressed. Between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago Neanderthal features are distinct and recognizable. However what from our modern perspective we see as “classic” Neanderthal, with the full set of features associated with them, did not appear until around 70,000 years ago.

Neanderthals share a common African ancestor with modern humans around somewhere between 550,000 and 750,000 years ago. That common ancestor is usually identified as Homo heidelbergensis. However a 2016 study suggests a divergence date for Neanderthals so far back in time it rules them out. The study proposes Homo antecessor as the best candidate. Whoever it may have been a group of this common ancestor species migrated into Europe. The group of hominids evolved not only into the Neanderthals but also into their sister group, the Denisovans. These two species diverged more than 390,000 years ago, perhaps between 430,000-473,000 years ago. The common ancestor group that remained in Africa evolved into homo sapiens.

Neanderthals were very widespread. Remains have been found ranging from Spain and the Mediterranean to Northern Europe and Russia. Remains have also been found throughout the Near East and as far east as Uzbekistan and Siberia. Neanderthals evolved from their predecessor in Ice Age Western Eurasia and lived there for over 100,000 years. These facts required that they be well-adapted to the often cold climate. Short and stocky, with Neanderthal men averaging around 66 inches (5 feet, 6 inches) Neanderthal women around 63 inches (5 feet, 3 inches) tall.

Both men and women possessed broad and deep ribcages. These humans had a different build than the taller and lankier modern humans. Their heavy brow ridges, large faces with appropriately large noses, and lack of chin further set them apart. These features make Neanderthal skulls markedly different from our own. Otherwise Neanderthals share a whole host of characteristics with modern humans. Amongst those were enlarged brains. Their brain cases were even larger than ours. Neanderthals also had less of a protruding face than many earlier archaic humans.

Regarding hair and skin color, Neanderthals likely had high variability. That variability was certainly higher than modern humans. Pale skin and red hair are suggested by the DNA from two specimens from Italy and Spain. Darker skin and brown or red hair are indicated in three individuals from Vindija, Croatia. The fossil record also betrays that Neanderthals were anything but pushovers. They led harsh and dangerous lives. Almost all well-preserved adult skeletons show some sign of trauma. This is usually around the head or neck region. Perhaps these injuries may have been related to hunting strategies in which they had to come close to large prey animals.

The majority of these skeletal injuries had healed or partially healed. This signifies that the individuals in question were socially cared for and recovered from their injuries to hunt another day. However not everyone was that lucky. Neanderthal adult average life expectancy was very low. This was clearly owing to the physically stressful and dangerous nature of their lives. Both the powerful build and amount of trauma seen in Neanderthals indicate they were active hunters. What we know about the high reliance on meat in their diet ties in with the amount of energy hunting would have required. They ate mostly herbivore meat. This meat was from mammals such as bison, wild cattle, reindeer, deer, ibex and wild boar.

The very largest of the Ice Age herbivores were woolly mammoths and woolly rhinoceros. Interestingly they actually represent a very large part of the Neanderthal diet. It would have been no mean feat to bring these animals down. This would have been true even for a coordinated group of skilled hunters, which the Neanderthals would have been. In addition to meat there was also a strong plant component to the Neanderthal diet. Most likely this would have consisted of legumes and grasses, seeds and fruits. It is also clear that Neanderthals cooked their food. Perhaps they even knew medicinal uses of plants.

The stone tools used by Neanderthals were most commonly (but not exclusively) associated with Mousterian lithic technology. Flint flakes were turned into side scrapers, retouched points, and small hand-axes. Typically locally available material was utilized to produce these stone implements. Very few bone tools are known, but wooden tools were most likely used as well. From at least 200,000 years ago Neanderthals had the ability to control fire. We know it was used then as a tool to produce birch-bark pitch. It’s likely Neanderthals used fire much earlier. The controlled use of fire appeared throughout Europe from 400,000 years ago onward.

Though exceptions are known, Neanderthals were not big on building their own structures. Their fires would predominantly have lit caves or other natural shelters. Archaeologists have located living areas in their shelters. They have generally been relatively small and a bit chaotic, showing no clear focus of activity. Hearths are well defined though. They probably played a central role not just with regard to cooking and warmth but also for tool production.

Traditionally Neanderthals have been depicted as cognitively inferior to the newly arrived modern humans. They’re presumed to possess a less sophisticated culture and lack of symbolic thought that would have modern humans a leg up. Recent discoveries however have overturned this image. Neanderthals were clearly a complex group. Effective communication would have been a prerequisite for their coordinated hunting techniques. The archaeological record also indicates advanced skills with respect to their use of fire as well as their tool production. Neanderthals have been known to intentionally bury their dead, and the archaeological record also indicates they cared for their wounded, even long-term care.

Stalagmite rings built by the Neanderthals in Bruniquel cave in France show planning and control of the underground environment, and perhaps symbolic use. These rings dated to 176,500 years ago. The Neanderthal also perforated and colored marine shells. Strikingly the Neanderthals also seem to have used red ochre at a site in Maastricht-Belvedère. Dating indicates this occurred as early as a stunning 200,000-250,000 years ago. This draws Neanderthal use of red ochre even with the time range documented for the African record for the use of ochre.

These were no simple brutes. Their disappearance cannot be explained away by a large gap in intelligence between our species which has historically been the perception. Around 55,000 years ago the main wave of modern humans that had left Africa met the Neanderthals in the Near East and Middle East, where they interbred. This was not the first time the two species met however. There is also some DNA evidence of genetic exchange between the two species happening roughly 100,000 years ago, possibly in the Near East. However the later event of about 55,000 years ago left the biggest genetic mark on our species. From the Near East modern humans then spread across Eurasia.

At the earliest modern humans reached Europe around 45,000 years ago. They came in much larger numbers that the already present Neanderthals. Modern humans were present in larger group size as well as greater population density. The Neanderthals suddenly faced competition for resources. Within about 5,000 years (about 40,000 years ago) the Neanderthals vanished from the fossil record.

In addition to competition from modern humans, there are other significant factors that may have played a role in the Neanderthals’ disappearance. One of these additional factors was the climate. Palaeoclimatologists have discovered that climate was much more unstable around that time than previously recognized. This may have stressed the Neanderthal population. That population was already many times smaller than the invading modern humans’ numbers. This disparity left Neanderthals vulnerable to the impact of modern humans.

Interbreeding with Neanderthals helped modern humans adapt to the colder climate in Europe. The Neanderthal genes impacted our skin color and hair. After leaving Africa our ancestral mixing with Neanderthals has had a profound effect on our genetic makeup. Non-African humans possess on average around ~2% Neanderthal DNA. However Neanderthal and modern humans were only of marginal biological compatibility. Research has shown that interbreeding led to decreased fertility as well as miscarriages when male babies possessed a Neanderthal Y chromosome. This would have decreased the total Neanderthal genetic contribution.

While interbreeding with Neanderthal may have been beneficial for modern humans, it may have been another factor in the explanation of why Neanderthals vanished. Combine the interbreeding with modern humans with the vast difference in population sizes between the two groups. This suggests that perhaps Neanderthals were to some extent simply ‘absorbed’ into our population. In the end the disappearance of Neanderthal must have been due to a combination of many different factors.

At a minimum the factors certainly would have included vast competition from modern humans, the harsh environment, as well as at least to some extended interbreeding with and absorption by the modern human populations. Researchers are only beginning to uncover the exact details of the genetic influence Neanderthal had on us. So while extinct, the relationship between modern man and Neanderthal lives on [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Homo denisova – Neanderthal’s First Cousin: The Denisovans are an extinct group of fossil humans who like the closely-related Neanderthals also share an ancestor with Homo sapiens. Thus far they are known only from Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in Siberia. There they first appeared somewhere between 200,000 and 287,000 years ago. Their last known presence in the archaeological record was around 55,000 years ago. This indicates the Denisovans at least at times called the Altai region of Siberia their home over a period of well over a 100,000 years.

The Denisova Cave itself is nestled in the Altai Mountains in Siberia. It’s near the point where Russia, Kazakhstan, China, and Mongolia all meet. The cave is formed in Silurian limestone and consists of three chambers; the Main Chamber, East Chamber and South Chamber. Together the three chambers measure around 2700 square feet. Denisova Cave was first explored by scientists in the 1970s. Excavations in subsequent decades have led to the discovery of artifacts attributable to the Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic stone industries. These constituted clues of the likely presence of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens at some point in time.

A real surprise excavated in 2008 was when a previously unknown human was added to this site's already seemingly busy track record. The finger bone of a young female was unearthed there. When DNA was successfully extracted it turned out she belonged to a distinct type of hominin that was dubbed the Denisovans. Denisova Cave was thus a true hotspot in the worlds of archaeology and anthropology. The girl became known as Denisova 3. She lived between 52,000 and 76,000 years ago. Within the Denisova Cave sediments have thus far yielded fossil remains belonging to a grand total of four known Denisovan individuals.

Denisova 3 paved the way for a previously unidentified male molar of a similar age known as Denisova 4. The previously unidentified molar was excavated in 2000. Given the identification information the DNA from Denisova 3 had provided, the unidentified molar was successfully confirmed as belonging to her species as well. The only other two fossils to be so far identified as Denisovan are two more molars. One permanent molar found in 2010 belonged to a male. Known as Denisova 8 it is between 105,600 and 136,400 years old). The second was a deciduous molar belonging to a very young girl who lived the furthest back in time. Her molar is between 122,700 and 194,400 years ago.

The truly stunning discovery was came in 2012 with the discovery of a long bone fragment of the female who had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. She lived between 80,000 and 120,000 years ago. The true blockbuster came in 2012 with the discovery of a long bone fragment belonging to a female who had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. To have actually found the remains of a first-generation mixed origin human when so few specimens have been found to date is astonishing. It reinforced the already established hypothesis that whenever different hominid groups met during the Late Pleistocene genetic exchange was not at all uncommon.

Indeed other fully Neanderthal remains have been recovered from Denisova Cave as well. The evidence suggests that both groups lived, met, and occasionally interbred with each other over an approximate time span of 150,000 years. Denisovan DNA not only showcases the fact that they had liaisons with Neanderthals but also that they interbred with an unknown archaic hominin group that branched off from the human lineage at least 1,000,000 years ago.

Denisovan DNA also reveals that they interbred with Homo sapiens ancestors of today’s Melanesians living in Southeast Asia and Oceania. This last event seems to have happened somewhere in Southeast Asia, far away from the Altai Mountains. This lends credence to the presumption that the Denisovans may have been far more widespread than their currently only known resting place betrays.

As mentioned above, in addition to Denisovan remains the remains of two full Neanderthals have also been found. Taken together with DNA found in sediments researchers believe that Neanderthals intermittently occupied Denisova Cave between about 193,000 and 97,000 years ago. Following that period excavations have identified Upper Paleolithic tooth pendants and bone points dated to between 43,000 and 49,000 years ago. These artifacts are generally associated with Homo sapiens. They are the earliest known occurrences of such artifacts within northern Eurasia. However Homo sapien bones or leftover bits of DNA have as of yet been found within Denisova Cave.

These artifacts are dated after the latest known Denisovan presence in the cave. However of course it is possible that Denisovans survived later. After all, excavations have only thus far uncovered a few bones. These artifacts could possibly be of Denisovan origin. That possibility is actually the theory that best suits the current (albeit limited) data excavations have provided at this point in time. Alternatively modern human remains have been unearthed that were dated to about 45,000 years ago at a site called Ust'-Ishim. Ust'-Ishim is northwest of and in close proximity to Denisova Cave. This may suggest Homo sapiens' involvement in the creation of these pendants and points.

If the artifacts were not directly created by Homo sapiens, they could conceivably have helped spread this culture and these techniques to Denisova Cave'. It would fit with Homo sapiens' general spread eastwards across Eurasia. A rich Upper Paleolithic assemblage including a well-developed stone bladelet technology is known from Denisova Cave. These are dated starting at about 36,000 years ago and lasting until about 20,000 years ago. These finds establish human occupation of Denisova Cave from about 300,000 to 20,000 years ago.

It is interesting to note that both Denisovan and Neanderthal DNA has been extracted from sediments in the cave from layers. The DNA pre-date sedimentary layers that have been found to contain the fossils remains. So the occupation timeframe is guided by more than just bones. Besides Homo sapiens excavations have not uncovered any evidence of other hominins surviving after a point in time 20,000 years ago. However just because their presence cannot be at least until this point confirmed by remains or DNA, does not mean that they could not have existed. Denisova Cave is still shrouded in mystery for now.

The physical characteristics of Denisovans included very large and robust teeth. The available DNA paints a picture of brown eyes set against dark skin topped with brown hair. But it is likely more variety existed considering Denisovans were probably more widespread. No question the material associated with the Denisovans is quite minimal. However both archaeology and science have come to the rescue. Together they have allowed us to determine some initial information regarding this species' characteristics. Sadly we cannot reconstruct their faces or bodies as of yet. However the three molars that were found show that the Denisovans had very large and robust teeth.

This characteristic corresponds with older hominins such as Homo erectus and even the Australopithecines than they do with our own tiny teeth, or even with the slightly bulkier Neanderthal ones. Big teeth seem to have been a typically Denisovan feature, at least for the ones living in the Altai Mountains. Both the details and broader features of the potential tool making skills of the Denisovans definitively establish as of yet.

Most studies published on Denisovans are of the genetic kind and can inform us as to how diverse the Denisovan population may have been. All of our current Denisovan fossils only stem from a single location. It’s striking however that genetic studies indicate they seem to have been at least equally diverse as the Neanderthals were across their widespread geographical range. In fact the genetic diversity found within the Denisovan DNA falls within the lower range of genetic diversity seen in modern humans today.

Of course this Altai-based group of Denisovans could conceivably have been fairly isolated. It is entirely possible that the Denisovans over their whole suggested geographical range may have been more varied. Some lucky finds of additional fossils would be very helpful in unraveling the Denisovan contribution to the history of mankind. Nonetheless the wonderful world of genetics has narrowed down where the Denisovans fit on the human lineage. It is clear that they are closely related to the Neanderthals and share a common ancestor with them. Denisovan and Neanderthal are estimated to have diverged more than 390,000 years ago, perhaps between 430,000 and 473,000 years ago.

This common lineage between Neanderthal and Denisovan extends to a shared ancestor within our own Homo sapiens species. The branch that would lead towards both Denisovans and Neanderthals and the branch that would develop into modern humans split off from each other around an estimated 765,000-550,000 years ago. This evolutionary connection is only the beginning. Future discoveries pertaining to the extent of our biological ties with both of these groups will make for fascinating, stunning news headlines.

Evidence is piling up that is finally overthrowing the old idea of linear evolution (i.e. one species evolves into the next, which evolves into the next, and so forth). As researchers today point out the evolutionary history of the genus Homo probably looked more like a river delta. Evolutionary streams weaving in and out, connecting and disconnecting. Some streams branched off, some streams petering off or hitting sandbar dead ends, others continuing their journey downstream.

Different groups of humans met and interbred at various times and places, with genes being widely exchanged. Evolutionary geneticist and Ancient DNA pioneer Svante Pääbo summarizes, "... our ancestors were part of a web of now-extinct populations linked by limited but intermittent, and perhaps sometimes even persistent, gene flow…" Our ever-helpful Denisovans have greatly served to underpin this notion. It’s already known that about 2% of modern non-African human genes had Neanderthal origins.

We now know there was also gene flow from Neanderthals into Denisovans. There was genetic flow from an unknown archaic human into the Denisovans. And around an estimated 31,000 to 50,000 years ago genetic material flowed from Denisovans into the ancestors of present-day (Home sapien) Melanesians living on Southeast Asian islands and in Oceania. On average 2-4% of Melanesian genes are of Denisovan origin. This fairly big proportion of Denisovan DNA in Melanesians leads us to think the Denisovans must have been more widespread than just the Altai Mountains.

The dating for the youngest, most recent Denisovan fossil is 51,600-76,200 years ago. This is before the point in time calculated by DNA research when modern humans and Denisovans interbred. If both sets of dates are correct this would necessitate one or both of two scenarios. The first scenario is that Denisovans from the Altai Mountains survived later than we presently know of. The second scenario is that another Denisovan population outlived the Altai Denisovans. They would have then interbred with modern humans, wherever elsewhere geographically that may have occurred.

Either way the Denisovan component that entered the modern human gene pool also occurs in diluted version across the Asian mainland and the Americas. At reduced levels it is widespread among modern humans in general, thanks to our human tendencies to migrate. Homo sapiens began spreading across Eurasia in greater numbers from around 60,000 years ago onwards. They were relative newcomers and genetically benefited from the exchange with long since established Neanderthals and Denisovans.

We already knew that Homo sapiens stole some skin and hair color genes when they interbred with Neanderthals. The genes were better suited to the colder northern ranges of the world. Homo sapiens also gained a nice immune system boost from both of these species. Denisovans and Neanderthal were already very much adapted to local Eurasian pathogens while Homo sapiens were not. This would have helped defend modern humans against the new array of parasites and bacteria.

More traits that are courtesy of the Denisovan mixing are also being identified by geneticists. These include the ability of Tibetans to cope with dizzyingly high altitudes. However, just like with the cozy connection with the Neanderthals, it seems the Sapiens- Denisovan connection also caused some problems. Certain bits of DNA we inherited from them turned out to be harmful. Evolution often aggressively selected against the inherited traits. It seems male mixed children may even have been sterile. These groups of humans shared ancestors and could obviously make babies together. However they were actually different enough to only be marginally biologically compatible. Think of the sterile mule offspring of horse and donkeys.

It is incredible that through a few fossils and accompanying tidbits belonging to only a few individuals, from one cave nestled high in the Siberian Altai Mountains, scientists have managed to extract so much information. To really paint a proper picture of who the Denisovans were we need to get digging and get very lucky. It would be wonderful to be able to stare into a reconstruction of their faces. It would be wonderful to know how tall or stocky they were. To know what their lifestyle and culture was actually like. It would be very gratifying to be able to ascertain how far spread they spread across the world and who exactly they bumped into (or made or gained genetic contributions from). More Denisovan-related finds would help to balance out our information and stretch it beyond mostly genetics. Hopefully the future will fill out the sparse details the past as so far provided us with [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Homo floresiensis: Homo floresiensis gained the nickname “hobbit” because it only stood about three feet (one meter) tall. Homo floresiensis is an extinct species of fossil human that lived on the island of Flores, Indonesia during the Pleistocene. Homo floresiensis is still shrouded in a fair bit of mystery. First excavated at Liang Bua Cave in 2003 these humans were originally thought to have lived between about 74,000 and 12,000 years ago. This would have made them the last surviving humans besides our own species of Homo sapiens. Recent evidence suggests however that these humans were actually quite a bit more ancient.