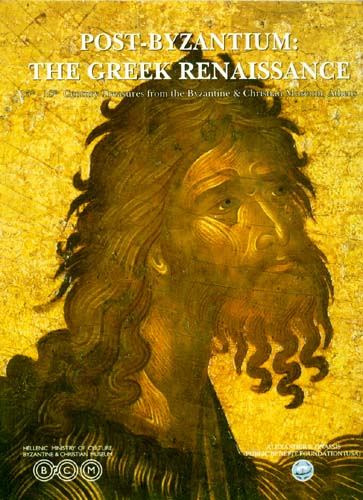

"Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance: 15th-18th Century Treasures from the Byzantine & Christian Museum, Athens" by George Kakavas and The Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Oversized Pictorial Softcover. Publisher: Hellenic Ministry of Culture (2002). Pages: 220. Size: 11½ x 9¼ x 1 inch; 3¼ pounds. Summary: Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance: 15th–18th Century Treasures from The Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, an exhibition of rare treasures from The Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens was the first exhibition in the United States to focus on this area of art history. It was presented at the Onassis Cultural Center in New York, as documented in the accompanying catalogue. Fifty works in various media, from paintings to filigree, highlight the range and influence of the Byzantine tradition that continued after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Most of the works in the exhibition, including such masterpiece icons as St. Antonios and The Three Hierarchs, by the 16th-century Cretan master Michael Damaskenos, have never been shown in the US.

Traditionally, art historians have focused their celebration of these centuries on the artistic developments and influences of the Renaissance in Western Europe, while the study of Byzantine art has often left off with the collapse of the Empire in the East. Post-Byzantium illuminates the persistence of the highly influential Byzantine style through this political change and for centuries afterwards. The pervasive strength of Byzantine culture meant that its artistic tradition continued to flourish after the disbanding of the Empire - a "Byzantium after Byzantium," in effect a Greek renaissance. Furthermore, the Eastern Orthodox Church, which served as a cohesive social and cultural institution, subsequently formalized many of the guidelines for artistic production in reverence for the Church's teachings and theological perspectives.

Sculpture, architecture, and particularly painting in the classic Byzantine style remained widespread in the world after the Fall. Byzantine artists and artisans from Crete, the Ionian Islands, Venice, and Ottoman held Central Greece and Asia Minor continued to work in communities that were far flung across the former empire. Although many of these artists were not celebrated as individual geniuses, subsequent study of Post-Byzantium has identified a number of them as unqualified masters of their genres.

"Post-Byzantium" is grouped into three thematic sections, including Icons, Golden Embroidered Textiles, and The Flourishing of Minor Arts, which includes art of gold and silver, enamels, filigrees, and carved wooden crosses. Icons, the largest section, is divided into sections from Constantinople-Crete, Italian-Cretan Works, Cretan Maistros, and Wall Paintings. The emphasis on different geographical areas reflects a historical moment in the spread of flourishing Post-Byzantine culture, which took place in all parts of the former empire. Men of letters and artists had begun gathering in Italy long before the Fall of the Empire, and after the Fall, Venice came to be known as 'the second Byzantium'.

Golden Embroidered Textiles presents a series of priests' garments, elaborately embroidered in the signature decorative Byzantine style. This section also includes an 18th century epitaphios, a type of embroidery that depicts Christ's bier and is common in Orthodox iconography. "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance" was organized by Dr. Dimitrios Konstantios, Director of the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens and curated by Dr. Eugenia Chalkia, Deputy Director of the Museum, which rarely lends works in its holdings.

CONDITION: LIKE NEW. HUGE new (albeit mildly shelfworn) unread pictorial softcover. Hellenic Ministry of Culture (2002) 220 pages. Unblemished in every respect except for very mild shelfwear to the covers. Inside the book is pristine, the pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Shelfwear to covers is principally in the form of very mild crinkling/abrasive rubbing at the spine head and heel. And by "very mild" we mean precisely that, literally. It requires that you hold the book up to a light source, tilting it this way and that so as to catch the reflected light, and scrutinize it quite intently to discern the shelfwear. While holding the book up to a light source and examining it intently, you'll also see that the back cover evidences faint rubbing/scuffing (the back cover is high gloss, photo-finish dark brown and so show slight rub marks even merely from being shelved between other books). We describe the book as "like new" given the faint and superficial shelfwear, but frankly most book sellers would simply grade this as "new". And indeed, except for the faint shelfwear to the covers, the overall condition of the book is relatively consistent with what might pass as "new" stock from a traditional brick-and-mortar open-shelf book store (such as Barnes & Noble, Borders, or B. Dalton, for example) wherein otherwise "new" books might show minor signs of shelfwear and/or faint cosmetic blemishes, consequence of routine handling and simply from being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #9041c.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Post-Byzantium, as the Romanian historian Nicolai Iorga aptly named the centuries that followed the collapse of the Byzantine Empire, is a period that is little known, particularly to the non-Greek public. The Byzantine and Christian Museum, desiring to enhance this period, during which the foundations were laid for the creation of the modern Greek state, organized this exhibition entitled “Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance”, in collaboration with the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (USA) at its Cultural Center in New York.

The aim of the exhibition is to present, through fifty-four splendid works of art form the collections of the Byzantine and Christian Museum (Athens), the survival of Byzantine artistic tradition after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, as well as the cultural achievements of Hellenism during the centuries when it was living and creating under foreign domination. The preservation and assimilation of the Byzantine heritage is the principal characteristic of the art that was cultivated in all regions of Hellenism, and which, through its radiance, served as an inspiration for the other Orthodox Christian peoples.

REVIEW: It is with great pleasure that the Onasis Foundation (USA) hosts at its Cultural Center in New York and exhibition organized by the Byzantine and Christian Museum of Athens from the period which follows the Fall of Constantinople to the hands of the Ottoman Turks (1453). The exhibits are artifacts of devotion and Christian faith with a strong Hellenic character. Their artistic, humanistic, and cultural value is indisputable and present in all.

They impress the viewer, regardless of religion, nationality, or cultural background. They reflect both Hellenic and Christian culture in their broadest ecumenical aspects. The far-reaching consequences of the Fall of Constantinople for the Christian world at large, be it Western, Central, or Eastern Europe, the Balkans or the Middle East, will be better understood and appreciated by those who view this exhibition. The Renaissance of the West owes much to the East and, in particular, to the rebirth of Hellenism in certain parts of Greece from the ashes of the Byzantine Empire.

REVIEW: Byzantium has been publicized and will be publicized even more by the excellent exhibitions mounted by the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and other institutions. But how much do we know about the splendid period of art that flourished not long after 1453 and during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries? The period is not, of course, a renaissance in the sense or with the characteristics of the quattrocento. It is however an artistic heyday after a political collapse. As recent research has demonstrated, the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 is a watershed event in history. But the tradition of government, the role of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and the entire artistic expression continued after the end of the Byzantine Empire.

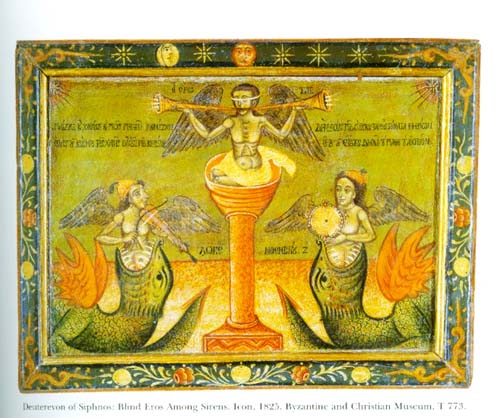

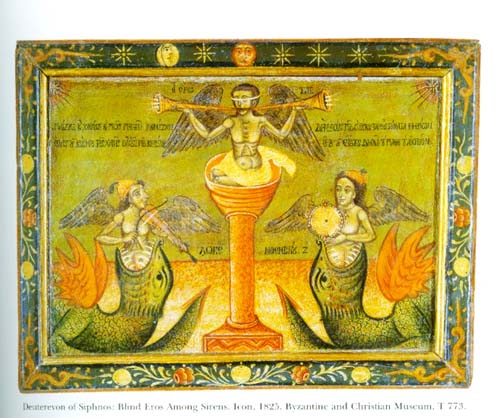

The new Christian East, with its political uniformity, can be dubbed Post-Byzantium at the level of art. This is the period of great artists and outstanding workshops. The period of influences and fertile contacts as well as of reaction, conflict, and transfusion. The Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens is fortunate in possessing superb works of this period. The present exhibition is but a small sample of the wealth of its collections. On display are fifty-four objects (icons, triptychs, wall-paintings, items in the minor arts, textiles, and books) spanning the period from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century, organized in units that enhance the artists and explicate the tole of the workshops in the context of the new political and social reality.

The significance of the exhibition is based on two nuclei. The first is the major eponymous painters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (Angels, Ritzos, Tzafouris, Damaskenos, Lambardos), who set their own seal on this Neohellenic “renaissance”. The second is the artistic workshops dispersed throughout the Orthodox Christian world of the East. Exquisite works by anonymous craftsmen imprint on metal, paper, and textile Byzantine tradition enriched with contemporary inquiries.

REVIEW: Published in conjunction with an exhibition held in New York in the Olympic Tower Atrium at the Onassis Cultural Center. Exhibition presents 54 works of art from the collection that represent the survival of Byzantine artistic tradition after the Fall of Constanipole in 1453 as well as the cultural achievements of Hellenism during the centuries when it was living and creating under foreign domination.

REVIEW: Dr. George Kakavas is director of both Athens National Archaaelogy Museum and the Numismatic Museum. He talks with Paul about the importance of preserving antiquities and how the archaeological museum works to preserve and also extend the knowledge of Greek antiquities. The Numismatic Museum is one of the only institutions of its kind in the world. It’s collections illustrate the evolution of stamps from ancient times to the present.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Salutation from the Hellenic Minister of Culture, Professor Evangelos Venizelos.

Salutation from the President of the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (USA), Mr. Stelio Papadimitriou.

Forward of the Director of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, Dr. Dimitrios Konstantios.

Part One:

“Byzance Apres Byance” Post-Byzantine Art (1453-1830) in the Greek Orthodox World by Professor Demetrios D. Triantaphyllopoulos.

Greece, Hearth of Art and Culture After the Fall of Constantinople by Dr. Dimitrios Konstantios.

Part Two:

Introduction by Eugenia Chalkia.

Authors of the Catalogue Entries.

Icons: From Constantinople to Crete.

Triptyches: Icons for Personal Devotions.

Churches and their Wall-Paintings.

Ecclesiastical Objects in the Applied Arts.

Gold-Embroidered Ecclesiastical Textiles.

From Manuscripts to Printed Books.

Bibliography - Abbreviations.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: With its East-meets-West styles, it is fabulous stuff, and that's how it looks in Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance. [The New York Times].

REVIEW: An intimate and beautifully designed exhibition of treasures from the Greek Orthodox world after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. [ARTnews].

REVIEW: Now on display in New York at the Onassis Cultural Center, "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance" is one of the nicest small-scale exhibitions I have ever seen. Subtitled "15th-18th Century Treasures from the Byzantine & Christian Museum, Athens", it presents 54 objects including icons, frescoes, early books (manuscript and printed), and liturgical metalworks and robes. Given the basic goal of the exhibition--"We wanted to make the post-Byzantine period better known to the public"--Eugenia Chalkia, the museum's deputy director and curator of the show, has made an outstanding selection of artworks.

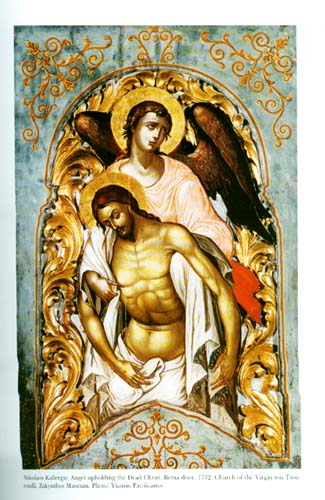

Many people believe, says Chalkia, that with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 A.D. there was an end to artistic creation in the Byzantine tradition, but there was continuity and important works were created in the following centuries. Each of the objects on display proves her point. One particularly significant artifact, ascribed to Nikolaos Tzafouris, is a late-fifteenth century icon showing Christ standing in a marble sarcophagus, with the lance at left, sponge at right, and cross behind him. It is a type produced by Cretan artists based on Western models.

The icons and triptychs (small three-paneled icons for private devotion or for use on travels) are the highlight of the exhibition. The most important post-Byzantine center for these was Crete, where painters sought refuge under the protection of Venice after the fall of Constantinople. There's an imposing mid-fifteenth century painting of Saint John the Baptist by a Cretan painter, but what impressed me more was the versatility of Cretan artists, embodied by Michael Damaskenos of the sixteenth century. Four icons by him are on display and show his ability to create extraordinarily beautiful works for Orthodox clients in the Byzantine style and for Catholic clients in a Venetian style.

Only two fresco fragments are in the show, a sixteenth-century head of a saint by a Cretan artist and Saint Anne, dating from the eighteenth century but in a severe, Byzantine style. This fresco fragment may be the work of the sixteenth-century painter Theophanis Strelitzas Bathas, who was born into a family of artists who fled from southern Greece to the safety of Venetian-occupied Crete after of Constantinople fell in 1453 A.D. Of the four early books on display, two are pilgrim's guides to Jerusalem. One of these, a late-seventeenth-century manuscript, has neat calligraphic script and exquisite miniatures depicting holy sites.

There are a number of liturgical vessels and implements, notably a gilded silver crosier with precious stone, enamel inlays, and delicate filigree work, showing the magnificent metalwork in the Byzantine tradition that was made during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (later than the peak of painting, which was more important in the first centuries after the fall of Constantinople). To demonstrate continuity in metalworking, a gilded filigree reliquary cross with carved steatite plaques, which dates from the last decades before 1453, is placed side-by-side with one made during the sixteenth or seventeenth century.

Religious vestments made of costly materials--silk and velvet, embellished with gold and silver thread and pearls--complete the exhibition. Unlike the icon painters and metalworkers who were men, the artists who created these were women. Made in Constantinople in the first half of the seventeenth century, one gold enkolpion was decorated with rubies and emeralds on one side and enamel inlays on the other. Such medallions are worn by Orthodox Bishops. The gilded silver chalice, with enamel and filigree work, was created by Papamanolis Nazloglou in 1710.

The exhibition gives an idea of the scope of the Byzantine & Christian Museum's collection, which includes objects gathered by the Christian Archaeological Society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, others brought by Greek refugees from Asia Minor in 1923, as well as individual donations and excavated material, especially from Athens and its surrounding areas. Expansion of the museum in Athens is under way, says its director, Dimitrios Konstantios. Currently about 400 objects from the collection are on display. That number will jump to 2,400 when the new exhibition areas are opened to the public in 2004, making it the world's largest Byzantine and post-Byzantine museum.

A tribute to those who, living in areas dominated by the Ottomans and Venetians, kept the artistic legacy of Byzantium alive, "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance" travels to Rome after its run in New York, where it will be exhibited at the Capitoline Museum. "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance" is sponsored by the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation. It's worth noting that the accompanying catalogue (220 pages mostly in full-color) is exquisite and a highly recommended acquisition. [Archaeological Institute of America].

REVIEW: The exhibition demonstrates the cultural and artistic flourishing of Hellenism in the Post-Byzantine period. The Post-Byzantine period, which begins with the collapse of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 and ends conventionally with the founding of the Modern Greek State in 1830, is characterised by the survival of many elements of Byzantine civilisation. This survival is most evident in the arts, which were practiced in the centres where Hellenism was living under foreign domination, mainly Ottoman and Venetian. Despite the difficult conditions, especially in the Ottoman-held regions, artistic creativity never ceased, but on the contrary produced notable results. Examples of this art, splendid works by eponymous and anonymous artists from various regions in which Hellenism thrived, are presented in the exhibition, worthily deserving the title 'The Greek Renaissance'.

The term 'renaissance' should, of course, be understood in a conventional sense and should not be identified with the well-known historical phenomenon that emerged and evolved in totally different historical circumstances. The Post-Byzantine artistic 'renaissance' should be regarded as a phenomenon that lies at the antipode of the Fall of Constantinople, as an art that flourished under adverse conditions, an endeavour to keep alive the artistic legacy of Byzantium. The works selected for this exhibition, paintings, objects in the applied arts and gold embroideries give the visitor some idea of the floruit in the visual arts that would have been impossible to accomplish without the education that is manifested by the manuscript codices and printed books.

After the introduction to the space and features of Post-Byzantium (I), the exhibition opens with books (II), so that the visitor is informed of the intellectual output of Hellenism during the Post-Byzantine period. The manuscript codices, ecclesiastical and secular, continue the Byzantine tradition, whereas concurrently printed books began to appear, published by Greek-run printing presses in major European cities, such as Venice and Vienna. Next comes the unit dedicated to painting, which is also the most important artistic expression of the Post-Byzantine period, covering both wall-paintings and portable icons.

Wall-paintings (III) are the principal genre of monumental painting during the Post-Byzantine period, since the tradition of mural mosaics, which was cultivated until the final years of Byzantium, was not continued. The churches these paintings decorate, of which they are an integral part, are of several architectural types in Post-Byzantine times. The closest to the Byzantine tradition are the katholika of monasteries which are of the cross-in-square or the triconch type, while the parish churches display greater variety (transverse-vaulted, aisleless, three-aisled). The wall-paintings, which usually cover the entire interior surface of the church, narrate scenes from the Old and the New Testament and/or the lives of saints. Apart from their symbolic meaning, they present in pictures the sacred texts for the congregation and are at once didactic and paradigmatic.

During the Post-Byzantine period, the art of wall-painting continued the tradition of previous centuries, producing notable ensembles in major monastic centres, such as Mount Athos and the Meteora, as well as in historiated churches and monasteries, mainly in Macedonia, Thessaly and Epirus. Leading exponents of the art were the Cretan Theophanis Strelitzas Bathas, the Theban Frangos Katellanos and the Kontaris brothers. Directly associated with the art of Theophanis is the fragment of a wall-painting with the head of a saint, presented in the exhibition, while a small piece with Saint Anne is typical of the severe wall-painting style of the 18th century, with overt Byzantine memories.

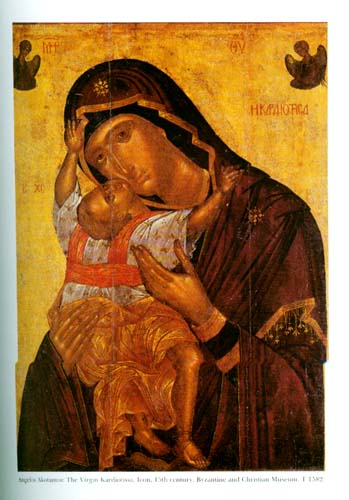

Portable icons (IV) are the paramount cult objects of the Orthodox Church. Painted on wood in the technique of egg tempera, they depict holy persons or biblical scenes, charged with abstruse theological meanings. Their veneration was established triumphantly after the end of Iconoclasm, which tormented Byzantium for more than a century (726-843). Icon-painting, which reached its peak during the final centuries of Byzantium (14th-15th centuries), continued to be cultivated after the Fall of Constantinople, maintaining the high artistic standards and the heritage of the Byzantine capital. The most important centre of icon production during the early centuries of Post-Byzantium (15th-16th centuries) was Crete, where the well-known Cretan School of painting was created by artists who had sought refuge from Constantinople on the island under Venetian occupation.

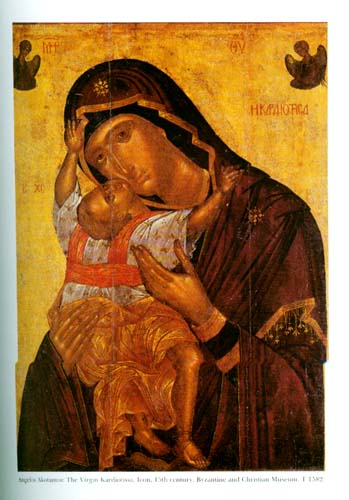

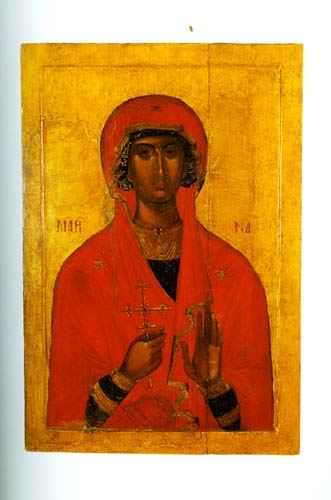

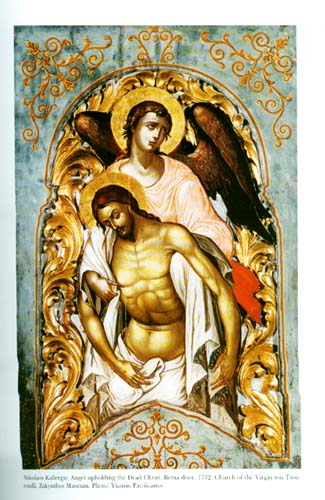

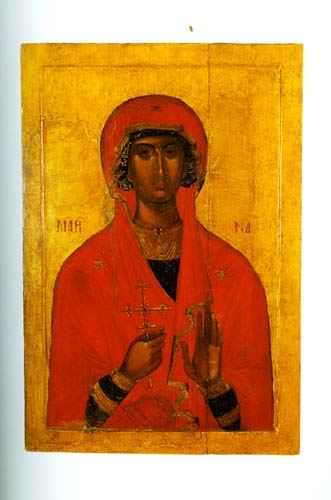

The relationship between works of the Cretan School dated to the first half of the fifteenth century, that is before the break up of Byzantium, and those painted in the second half of the century can be appreciated by comparing the icons of Saint Marina, the Hospitality of Abraham, the Ascension and Saint John the Baptist, signed by the great painter Angelos Akotantos, with the Royal doors bearing the scene of the Annunciation and the icon of the Dormition of Hosios Ephraim. Other great painters, representatives of the Cretan School, such as Andreas Ritzos and Nikolaos Tzafouris, are featured in the exhibition with their works, J(esus) H(ominum) S(alvator), the first, and the Virgin Madre della Consolazione with Saint Francis and Christ Man of Sorrows, the second.

These three works are characterised by pronounced iconographic and stylistic influences from Western art, one of the principal traits of the Cretan School. There is nothing strange about this fact, if we consider that the painters were living in a Venetian-held region and receiving commissions from both Orthodox and Catholic clients. Thus they were cognisant of and competent in two painting manners, the maniera greca and the maniera latina. This tradition was continued in the following century, as can be observed in the icon of the Virgin Galaktotrophousa (Lactans) with Saint John the Baptist, but especially in the icons by the famous 16th-century painter Michael Damaskenos, who practised and combined both painting manners with equal facility.

To his austere works, in which he cleaves to Byzantine tradition, is countered the icon of the Crucifixion of Saint Andrew, with overt borrowings from Western art. The later representatives of the Cretan School, Thomas Bathas and Emmanuel Lambardos, followed in the footsteps of the great mentors. Triptychs (V), three-leaved icons with the main subject on the middle leaf, secondary representations on the side leaves, and an elaborate wood-carved frame, constitute a special category of icons. They are usually intended for private devotion and are kept in the household icon-shrine or carried by their owner as amulets on his/her travels. Fewer in number are the liturgical triptychs, which are placed in the prothesis of the church and contain, on the inside of the leaves, columns with names of persons living and dead, whom the priest remembers during the order of preparation (Prothesis) of the Sacrament the bread and wine of the Eucharist.

The triptychs in the exhibition, two for private devotion and one liturgical, with their rich thematic repertoire and flawless technique, are classed among the good works of the Cretan School in the sixteenth century. Vestments (VI) represent one of the most opulent branches of art. Both the sacerdotal vestments, which are the attire of clerics of all ranks, and the liturgical ones worn by celebrants of the Mass, are charged with symbolic meanings which are usually expressed in the iconographic subjects chosen for their adornment, as is the case with all the paraphernalia of worship. Fashioned from precious textiles, such as silk and velvet, and embroidered with gold and silver threads and pearls, they enhance the status of the priesthood and endow religious rites and ceremonies with splendor.

In Post-Byzantium the art of embroidery also continued the Byzantine tradition, producing important works, very often signed by accomplished needlewomen. One of the most important centres of the art of ecclesiastical embroidery was Constantinople, which is the provenance of some of the vestments displayed in the exhibition. The applied arts (VII) or minor arts, which encompass diverse works in many materials, are represented in the exhibition mainly by ecclesiastical silverware. In contrast to painting, which produced its most magnificent examples in the first centuries after the Fall of Constantinople, the applied arts came into their own mainly during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which period coincides with the zenith of the monastic centres and the appearance of workshops around these, as well as with the burgeoning of the economy that enabled the faithful to dedicate precious works in the churches.

In general, the iconography and techniques of church silverware reproduce those of corresponding Byzantine pieces, while in parallel accepting and assimilating influences from both Ottoman and Western art. Although the silversmith’s art did not reach the level achieved by its Byzantine models, it nonetheless produced admirable works, distinguished by elaborate decoration and impeccable technique. The reliquary-cross with gilded filigree revetment and steatite plaques is among the works of the last years of Byzantium which served as prototypes in the ensuing centuries, as is apparent from the processional or litany cross with similar decoration. It was most probably made in Constantinople, where silversmiths’ workshops continued to operate after the Fall. Among their products are the refined double-sided enkolpion or pectoral, set with precious stones, and the artophorion and paten that were dedicated by the Metropolitan of Adrianople, Neophytos, to churches in his See.

Another important votive offering, this time of a political leader, is the Gospel book, gifted by the Prince of Wallachia, Matthaios Basarabas, to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. An assemblage of high quality artworks in the exhibition comes from the workshops that operated around the Backovo monastery in what is now Bulgaria, a region in which there were prosperous Greek communities. The technique of the delicate filigree decoration upon an enamelled ground and the colourful precious and semi-precious stones are distinctive of all these luxurious objects that were dedicated, usually by prelates, in the renowned monastic foundation. Of simpler art yet of equally good quality is the silverware from workshops in other regions, such as Asia Minor, one of the most important centers of Hellenism during the Post-Byzantine period. Included among works in the applied arts are the carved wood crosses without metal revetment, works of remarkable intricacy and excellent technique that were usually made in Athonite workshops. [Euromuse.net].

REVIEW: Reflections of Byzantium, Where East Meets West. I went to Mount Athos -- Hagion Oros, the Holy Mountain -- in Greece in 1982, and I went the way everyone does: very slowly. From New York I wrote to the Greek Foreign Ministry asking permission to visit this great monastic center, isolated on a squared-off peninsula in the northern Aegean. In Athens, I picked up my pass for a four-day stay, then took a long bus ride to Thessalonika, and another to the port town of Ouranopolis.

From there you reach Athos by a boat that makes the short trip daily. I had to wait two days, though, when word came that a distraught monk had locked himself in a cell with explosives, threatening to blow up a monastery. Athos was in lock-down mode until he was subdued or changed his mind. The 15 passengers on the small boat were men; women, unless they were theology students, were not allowed on Athos. Greek workers and farmers, they had come on pilgrimage, for spiritual retreat. I had come for an experience of a still living Byzantine culture, and I got it: in monastery churches glinting with icons, in their libraries dense with manuscripts and in the oceanic sound of chanting in the night.

Much of what I saw was actually post-Byzantine art, dating from the centuries after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453. With its East-meets-West styles, it is fabulous stuff, and that's how it looks in "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance", a true sleeper of an exhibition at the Onassis Cultural Center in Midtown Manhattan. All of the show's 50 objects -- paintings, embroideries, liturgical implements -- are on loan from the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens. That alone makes the show an occasion. They also represent, as the curator, Eugenia Chalkia, points out in the exhibition catalog, a still little studied aspect of the Byzantine tradition: a late, hybrid, ''impure'' style of a kind that art historians are only beginning to value and savor.

Although Byzantium had an incalculable effect on art in Italy in earlier centuries, by the time of the Italian Renaissance, the flow of influence had reversed. The effect on Greek art was gradual and subtle. The earliest painting in the show, a half-length, almost life-size icon of St. Marina, dates from the late 14th or early 15th century. Posed on a solid gold ground and staring out from a scarlet robe that encases her like a carapace, she represents a Byzantine style still intact. Then other elements filter in. A marvelous 15th-century panel painting by the Cretan master painter Angelos Akotantos depicts St. John the Baptist with wings, a Byzantine convention. But the flex of the saint's body and the closely observed form of the dove at his feet are naturalist in an Italian way.

There are also Italian themes. In a late-15th-century painting by Andreas Ritzos, another artist working on Crete, which had become a center of Byzantine religious art, scenes of the Crucifixion and Resurrection are ingeniously composed to form the letters J. H. S. This is the abbreviation of the Latin phrase Jesus Hominum Salvator (''Jesus Savior of Men''), a Franciscan emblem. And St. Francis of Assisi himself turns up in another painting from the same period, attributed to Nikolaos Tzafouris. Even as time passed, though, and the world changed, the Byzantine style was preserved, as is seen in two late-16th-century paintings by Michael Damaskenos. His depiction of a gray-bearded St. Anthony is as imperturbably monumental as something carved from stone, though the saint's petite, youthful hands have the warmth of life.

No such concessions to realism are made in a depiction of Jesus as a regal high priest. His jewel-studded miter and assertively patterned, form-flattening vestments give him an abstract magnificence that has nothing to do with life on earth. Here you know at a glance that you are in the Byzantium of old, and you know it again and again in the elaborate wood-and-enamel liturgical crosses and silver-threaded vestments that fill out the show. Roman Catholicism created a grand, competitive version of such opulence. But Byzantine art has something all its own: a time-suspending stillness that Western art never really absorbed.

I certainly resisted it on my Athos visit. I knew I had just four days, and I wanted to see everything. This meant staying on the move, making dusty hikes on foot between monasteries -- there are almost 20 -- always hoping I would arrive in time for someone to show me around. On my last morning, I arrived at the little monastery called Stavronikita, compact and fortresslike on a headland over the sea. In the gatehouse, the monk in charge of receiving guests served me a glass of cold water and a sugar-dusted sweet, customary welcoming fare. I pulled out a notebook with my list of must-see things -- the church has 16th-century frescoes -- eager to begin a tour, but the monk, who spoke no English, had chores to attend to first.

The day was hot, and I was tense and frazzled. I was on world time; he was on Athos time, icon time. He knew; he had seen all this before. He stood directly facing me and with a slow, lowering gesture of both hands indicated "sit". So I did; then I put the notebook away; then I looked around me for a long time. "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance" is memorialized in a catalogue of the same title, a worthy presentation of the ehibitgs together with historical insights. [New York Times].

REVIEW: "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance", a major exhibition in Rome. After its successful presentation in the US, the exhibition "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance" travels to Rome, Italy, where it is presented at the Musei Capitolini. The exhibition showcases 54 masterpieces that highlight the range and influence of the Byzantine tradition after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 until the first half of the 19th century. All the exhibits come rom The Byzantine and Christian Museum of Athens. "Post-Byzantium", produced by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, is co-organized by the Greek Embassy in Rome and the Municipality of the Italian capital city. It is grouped into three thematic sections, including Icons, Golden Embroidered Textiles, and The Flourishing of Minor Arts.

Icons, the largest section, is divided into sections from Constantinople-Crete, Italian-Cretan Works, Cretan Maistors, and Wall Paintings. The emphasis on different geographical areas reflects a historical moment in the spread of flourishing Post-Byzantine culture, which took place in all parts of the former empire. Men of letters and artists had begun gathering in Italy long before the Fall of the Empire, and after the Fall, Venice came to be known as 'the second Byzantium'. Golden Embroidered Textiles presents a series of priests' garments, elaborately embroidered in the signature decorative Byzantine style. This section also includes an 18th century epitaphios, a type of embroidery that depicts Christ's bier and is common in Orthodox iconography.

The Flourishing of Minor Arts, which includes art of gold and silver, enamels, filigrees, and carved wooden crosses. Traditionally, art historians have focused their celebration of these centuries on the artistic developments and influences of the Renaissance in Western Europe, while the study of Byzantine art has often left off with the collapse of the Empire in the East. Post-Byzantium illuminates the persistence of the highly influential Byzantine style through this political change and for centuries afterwards. The pervasive strength of Byzantine culture meant that its artistic tradition continued to flourish after the disbanding of the Empire - a "Byzantium after Byzantium," in effect a Greek renaissance.

Furthermore, the Eastern Orthodox Church, which served as a cohesive social and cultural institution, subsequently formalized many of the guidelines for artistic production in reverence for the Church's teachings and theological perspectives. Sculpture, architecture, and particularly painting in the classic Byzantine style remained widespread in the world after the Fall. Byzantine artists and artisans from Crete, the Ionian Islands, Venice, and the Ottoman-held Central Greece and Asia Minor continued to work in communities that were far flung across the former empire. Although many of these artists were not celebrated as individual geniuses, subsequent study of Post-Byzantium has identified a number of them as unqualified masters of their genres.

The exhibition "Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance" is hosted at Rome's Musei Capitolini under the title "Glimpses of Byzantium." From November 2002 to February 2003 it had been presented in New York and that was the first time that the precious exhibits ever left Greece. [Biblioteca Theologica].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Great selection, nice reproductions and text. This must have been a nice little exhibition, worthy of ruminating over. As with many of the exhibition catalogs I've bought, I wish I'd seen it. This is a good substitute.

REVIEW: Superb catalogue. Exquisite art. Well-written and informative narration. Splendid photography. This is a real winner, cataloguing wondrous works of art!

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

Byzantine History: The Byzantine Empire was the eastern remainder of the great Roman Empire, and stretched from its capital in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey) through much of Eastern Europe, Asia Minor, and small portions of North Africa and the Middle East. Prior to the fifth century collapse of the Western Roman Empire, one of Rome’s greatest emperors, Constantine the Great, established a second capital city for the Roman Empire in the East at Byzantium, present day Turkey. Constantine The Great sought to reunite the Roman Empire, centered upon Christian faith, by establishing a second "capital" for the Eastern Roman, away from the pagan influences of the city of Rome. Established as the new capital city for the Eastern Roman Empire in the fourth century, Constantine named the city in his own honor, “Constantinople”.

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the “Byzantine Empire”, lasted for another thousand years as the cultural, religious and economic center of Eastern Europe. At the same time, as a consequence of the fall of the Western Roman Empire, most of the rest of Europe suffered through one thousand years of the "dark ages". As the center of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople was one of the most elaborate, civilized, and wealthy cities in all of history. The Christian Church eventually became the major political force in the Byzantine Empire. In Byzantine art, God rather than man stood at the center of the universe. Constantine the Great is also credited with being the first Christian Roman Emperor, and was eventually canonized by the Orthodox Church. Christianity had of course been generally outlawed prior to his reign.

Under the Byzantine Empire, Christianity became more than just a faith, it was the theme of the entire empire, its politics, and the very meaning of life. Christianity formed an all-encompassing way of life, and the influence of the Byzantine Empire reached far both in terms of time and geography, certainly a predominant influence in all of Europe up until the Protestant Reformation. In Byzantine art, God rather than man stood at the center of the universe. Representations of Christ, the Virgin, and various saints predominated the coinage of the era. The minting of the coins remained crude however, and collectors today prize Byzantine coins for their extravagant variations; ragged edges, "cupped" coins, etc. Other artifacts such as rings, pendants, and pottery are likewise prized for their characteristically intricate designs [AncientGifts].

The Byzantine Empire: The Byzantine Empire was the continuation of the Roman Empire in the Greek-speaking, eastern part of the Mediterranean. Christian in nature, it was perennially at war with the Muslims, Flourishing during the reign of the Macedonian emperors, its demise was the consequence of attacks by Seljuk Turks, Crusaders, and Ottoman Turks. Byzantium was the name of a small, but important town at the Bosporus, the strait which connects the Sea of Marmara and the Aegean to the Black Sea, and separates the continents of Europe and Asia. In Greek times the town was at the frontier between the Greek and the Persian world. In the fourth century B.C., Alexander the Great made both worlds part of his Hellenistic universe, and later Byzantium became a town of growing importance within the Roman Empire.

By the third century A.D. the Romans had many thousands of miles of border to defend. Growing pressure caused a crisis, especially in the Danube/Balkan area, where the Goths violated the borders. In the East, the Sasanian Persians transgressed the frontiers along the Euphrates and Tigris. The emperor Constantine the Great (reign 306-337 A.D.) was one of the first to realize the impossibility of managing the empire's problems from distant Rome. So, in 330 A.D. Constantine decided to make Byzantium, which he had refounded a couple of years before and named after himself, his new residence. Constantinople lay halfway between the Balkan and the Euphrates, and not too far from the immense wealth and manpower of Asia Minor, the vital part of the empire.

"Byzantium" was to become the name for the East-Roman Empire. After the death of Constantine, in an attempt to overcome the growing military and administrative problem, the Roman Empire was divided into an eastern and a western part. The western part is considered as definitely finished by the year 476 A.D. when its last ruler was dethroned and a military leader, Odoacer, took power. In the course of the fourth century, the Roman world became increasingly Christian, and the Byzantine Empire was certainly a Christian state. It was the first empire in the world to be founded not only on worldly power, but also on the authority of the Church. Paganism, however, stayed an important source of inspiration for many people during the first centuries of the Byzantine Empire.

When Christianity became organized, the Church was led by five patriarchs, who resided in Alexandria, Jerusalem, Antioch, Constantinople, and Rome. The Council of Chalcedon (451 A.D.) decided that the patriarch of Constantinople was to be the second in the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Only the pope in Rome was his superior. After the Great Schism of 1054 A.D. the eastern (Orthodox) church separated form the western (Roman Catholic) church. The centre of influence of the orthodox churches later shifted to Moscow.

Since the age of the great historian Edward Gibbon, the Byzantine Empire has a reputation of stagnation, great luxury and corruption. Most surely the emperors in Constantinople held an eastern court. That means court life was ruled by a very formal hierarchy. There were all kinds of political intrigues between factions. However, the image of a luxury-addicted, conspiring, decadent court with treacherous empresses and an inert state system is historically inaccurate. On the contrary: for its age, the Byzantine Empire was quite modern. Its tax system and administration were so efficient that the empire survived more than a thousand years.

The culture of Byzantium was rich and affluent, while science and technology also flourished. Very important for us, nowadays, was the Byzantine tradition of rhetoric and public debate. Philosophical and theological discourses were important in public life, even emperors taking part in them. The debates kept knowledge and admiration for the Greek philosophical and scientific heritage alive. Byzantine intellectuals quoted their classical predecessors with great respect, even though they had not been Christians. And although it was the Byzantine emperor Justinian who closed Plato's famous Academy of Athens in 529 A.D., the Byzantines are also responsible for much of the passing on of the Greek legacy to the Muslims, who later helped Europe to explore this knowledge again and so stood at the beginning of European Renaissance.

Byzantine history goes from the founding of Constantinople as an imperial residence on 11 May 330 A.D. until Tuesday 29 May 1453 A.D. when the Ottoman sultan Memhet II conquered the city. Most times the history of the Empire is divided into three periods. The first of these, from 330 till 867 A.D., saw the creation and survival of a powerful empire. During the reign of Justinian (527-565 A.D.), a last attempt was made to reunite the whole Roman Empire under one ruler, the one in Constantinople. This plan largely succeeded: the wealthy provinces in Italy and Africa were reconquered, Libya was rejuvenated, and money bought sufficient diplomatic influence in the realms of the Frankish rulers in Gaul and the Visigothic dynasty in Spain.

The refound unity was celebrated with the construction of the church of Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, in Constantinople. The price for the reunion, however, was high. Justinian had to pay off the Sasanian Persians, and had to deal with firm resistance, for instance in Italy. Under Justinian, the lawyer Tribonian (500-547 A.D.) created the famous Corpus Iuris. The Code of Justinian, a compilation of all the imperial laws, was published in 529 A.D. Soon the Institutions (a handbook) and the Digests (fifty books of jurisprudence), were added. The project was completed with some additional laws, the Novellae. The achievement becomes even more impressive when we realize that Tribonian was temporarily relieved of his function during the Nika riots of 532 A.D., which in the end weakened the position of patricians and senators in the government, and strengthened the position of the emperor and his wife.

After Justinian, the Byzantine and Sasanian empires suffered heavy losses in a terrible war. The troops of the Persian king Khusrau II captured Antioch and Damascus, stole the True Cross from Jerusalem, occupied Alexandria, and even reached the Bosporus. In the end, the Byzantine armies were victorious under the emperor Heraclius (reign 610-642 A.D.). However, the empire was weakened and soon lost Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Cryonic, and Africa to the Islamic Arabs. For a moment, Syracuse on Sicily served as imperial residence. At the same time, parts of Italy were conquered by the Lombards, while Bulgars settled south of the Danube. The ultimate humiliation took place in 800 A.D., when the leader of the Frankish barbarians in the West, Charlemagne, preposterously claimed that he, and not the ruler in Constantinople, was the Christian emperor.

The second period in Byzantine history consists of its apogee. It fell during the Macedonian dynasty (867-1057 A.D.). After an age of contraction, the empire expanded again and in the end, almost every Christian city in the East was within the empire's borders. On the other hand, wealthy Egypt and large parts of Syria were forever lost, and Jerusalem was not reconquered. In 1014 A.D. the mighty Bulgarian empire, which had once been a very serious threat to the Byzantine state, was finally overcome after a bloody war, and became part of the Byzantine Empire. The victorious emperor, Basilius II, was surnamed Boulgaroktonos, "slayer of Bulgars". The northern border now was finally secured and the empire flourished.

Throughout this whole period the Byzantine currency, the nomisma, was the leading currency in the Mediterranean world. It was a stable currency ever since the founding of Constantinople. Its importance shows how important Byzantium was in economics and finance. Constantinople was the city where people of every religion and nationality lived next to one another, all in their own quarters and with their own social structures. Taxes for foreign traders were just the same as for the inhabitants. This was unique in the world of the middle ages.

Despite these favorable conditions, Italian cities like Venice and Amalfi, gradually gained influence and became serious competitors. Trade in the Byzantine world was no longer the monopoly of the Byzantines themselves. Fuel was added to these beginning trade conflicts when the pope and patriarch of Constantinople went separate ways in 1054 A.D. (the Great Schism). Decay became inevitable after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 A.D. Here, the Byzantine army under the emperor Romanus IV Diogenes, although reinforced by Frankish mercenaries, was beaten by an army of the Seljuk Turks, commanded by Alp Arslan ("the Lion"). Romanus was probably betrayed by one of his own generals, Joseph Tarchaniotes, and by his nephew Andronicus Ducas.

After the battle, the Byzantine Empire lost Antioch, Aleppo, and Manzikert, and within years, the whole of Asia Minor was overrun by Turks. From now on, the empire was to suffer from manpower shortage almost permanently. In this crisis, a new dynasty, the Comnenes, came to power. To obtain new Frankish mercenaries, emperor Alexius sent a request for help to pope Urban II, who responded by summoning the western world for the Crusades. The western warriors swore loyalty to the emperor, reconquered parts of Anatolia, but kept Antioch, Edessa, and the Holy Land for themselves.

For the Byzantines, it was increasingly difficult to contain the westerners. They were not only fanatic warriors, but also shrewd traders. In the twelfth century, the Byzantines created a system of diplomacy in which deals were concluded with towns like Venice that secured trade by offering favorable positions to merchants of friendly cities. Soon, the Italians were everywhere, and they were not always willing to accept that the Byzantines had a different faith. In the age of the Crusades, the Greek Orthodox Church could become a target of violence too. So it could happen that Crusaders plundered the Constantinople in 1204 A.D. Much of the loot can still be seen in the church of San Marco in Venice.

For more than half a century, the empire was ruled by monarchs from the West, but they never succeeded in gaining full control. Local rulers continued the Byzantine traditions, like the grandiloquently named "emperors" of the Anatolian mini-states surrounding Trapezus, where the Comnenes continued to rule, and Nicaea, which was ruled by the Palaiologan dynasty. The Seljuk Turks, who are also known as the Sultanate of Rum, benefited greatly of the division of the Byzantine Empire, and initially strengthened their positions. Their defeat, in 1243 A.D., in a war against the Mongols, prevented them from adding Nicaea and Trapezus as well. Consequently, the two Byzantine mini-states managed to survive.

The Palaiologans even managed to capture Constantinople in 1261 A.D., but the Byzantine Empire was now in decline. It kept losing territory, until finally the Ottoman Empire (which had replaced the Sultanate of Rum) under Mehmet II conquered Constantinople in 1453 A.D. and took over government. Trapezus surrendered eight years later. After the Ottoman take-over, many Byzantine artists and scholars fled to the West, taking with them precious manuscripts. They were not the first ones. Already in the fourteenth century, Byzantine artisans, abandoning the declining cultural life of Constantinople, had found ready employ in Italy. Their work was greatly appreciated and western artists were ready to copy their art. One of the most striking examples of Byzantine influence is to be seen in the work of the painter Giotto, one of the important Italian artists of the early Renaissance. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Ancient Constantinople/Byzantium: Built in the seventh century B.C., the ancient city of Byzantium proved to be a valuable city for both the Greeks and Romans. Because it lay on the European side of the Strait of Bosporus, the Emperor Constantine understood its strategic importance and upon reuniting the empire in 324 A.D. built his new capital there; Constantinople. Emperor Diocletian who ruled the Roman Empire from 284 to 305 A.D. believed that the empire was too big for one person to rule and divided it into a tetrarchy (rule of four) with an emperor (Augustus) and a co-emperor (Caesar) in both the east and west.

Diocletian chose to rule the east. Young Constantine rose to power in the west when his father, Constantius, died. The ambitious ruler defeated his rival, Maxentius, for power at the Battle of Milvian Bridge and became sole emperor of the west in 312 A.D. When Lucinius assumed power in the east in 313 A.D., Constantine challenged and ultimately defeated him at the Battle of Chrysopolis, thereby reuniting the empire. Constantine was unsure where to locate his new capital. Old Rome was never considered. He understood the infrastructure of the city was declining; its economy was stagnant and the only source of income was becoming scarce. Nicomedia had everything he could want for a capital; a palace, a basilica and even a circus; but it had been the capital of his predecessors, and he wanted something new.

Although he had been tempted to build his capital on the site of ancient Troy, Constantine decided it was best to locate his new city at the site of old Byzantium, claiming it to be a New Rome (Nova Roma). The city had several advantages. It was closer to the geographic center of the Empire. Since it was surrounded almost entirely by water, it could be easily defended (especially when a chain was placed across the bay). The location provided an excellent harbor; thanks to the Golden Horn; as well as easy access to the Danube River region and the Euphrates frontier. Thanks to the funding of Lucinius’s treasury and a special tax, a massive rebuilding project began. Constantinople would become the economic and cultural hub of the east and the center of both Greek classics and Christian ideals.

Although he kept some remnants of the old city, New Rome, four times the size of Byzantium, was said to have been inspired by the Christian God, yet remained classical in every sense. Built on seven hills (just like Old Rome), the city was divided into fourteen districts. Supposedly laid out by Constantine himself, there were wide avenues lined with statues of Alexander the Great, Caesar, Augustus, Diocletian, and of course, Constantine dressed in the garb of Apollo with a scepter in one hand and a globe in the other. The city was centered on two colonnaded streets (dating back to Septimus Severus) that intersected near the baths of Zeuxippus and the Testratoon.

The intersection of the two streets was marked by a four-way arch, the Tetraphylon. North of the arch stood the old basilica which Constantine converted into a square court, surrounded by several porticos, housing a library and two shrines. Southward stood the new imperial palace with its massive entrance, the Chalke Gate. Besides a new forum, the city boasted a large meeting hall that served as a market, stock exchange, and court of law. The old circus was transformed into a victory monument, including one monument that had been erected at Delphi, the Serpent Column, celebrating the Greek victory over the Persians at Plataea in 479 B.C. While the old amphitheater was abandoned (the Christians disliked gladiatorial contests), the hippodrome was enlarged for chariot races.

One of Constantine’s early concerns was to provide enough water for the citizenry. While Old Rome didn’t have the problem, New Rome faced periods of intense drought in the summer and early autumn and torrential rain in the winter. Together with the challenge of the weather, there was always the possibility of invasion. The city needed a reliable water supply. There were sufficient aqueducts, tunnels and conduits to bring water into the city but a lack of storage still existed. To solve the problem the Binbirderek Cistern (it still exists) was constructed in 330 A.D.

Religion took on new meaning in the empire. Although Constantine openly supported Christianity (his mother was one), historians doubt whether or not he truly ever became a Christian, waiting until his deathbed to convert. New Rome would boast temples to pagan deities (he had kept the old acropolis) and several Christian churches; Hagia Irene was one of the first churches commissioned by Constantine. It would perish during the Nika Revolts under Justinian in 532 A.D. In 330 A.D., Constantine consecrated the Empire’s new capital, a city which would one day bear the emperor’s name. Constantinople would become the economic and cultural hub of the east and the center of both Greek classics and Christian ideals. Its importance would take on new meaning with Alaric’s invasion of Rome in 410 A.D. and the eventual fall of the city to Odoacer in 476 A.D. During the Middle Ages, the city would become a refuge for ancient Greek and Roman texts.

In 337 A.D. Constantine died, leaving his successors and the empire in turmoil. Constantius II defeated his brothers (and any other challengers) and became the empire’s sole emperor. The only individual he spared was his cousin Julian, only five years old at the time and not considered a viable threat; however, the young man would surprise his older cousin and one day becomes an emperor himself, Julian the Apostate. Constantius II enlarged the governmental bureaucracy, adding quaestors, praetors, and even tribunes. He built another cistern and additional grain silos. Although some historians disagree (claiming Constantine laid the foundation), he is credited with building the first of three Hagia Sophias, the Church of Holy Wisdom, in 360 A.D. The church would be destroyed by fire in 404 A.D., rebuilt by Theodosius II, destroyed and rebuilt again under Justinian in 532 A.D.

A convert to Arianism, Constantius II’s death would place the already tenuous status of Christianity in the empire in jeopardy. His successor, Julian the Apostate, a student of Greek and Roman philosophy and culture (and the first emperor born in Constantinople), would become the last pagan emperor. Although Constantinius had considered him weak and non-threatening, Julian had become a brilliant commander, gaining the support and respect of the army, easily assuming power upon the emperor’s death. Although he attempted to erase all aspects of Christianity in the empire, he failed. Upon his death fighting the Persians in 363 A.D., the empire was split between two brothers, Valentinian I (who died in 375 A.D.) and Valens.

Valentinian, the more capable of the two, ruled the west while the weaker and short-sighted Valens ruled the east. Valens only contribution to the city and the empire was to add a number of aqueducts, but in his attempt to shore up the empire’s frontier --he had allowed the Visigoths to settle there-- he would lose a decisive battle and his life at Adrianople in 378 A.D. After Valens embarrassing defeat, the Visigoths believed Constantinople to be vulnerable and attempted to scale the walls of the city but ultimately failed. Valen’s successor was Theodosius the Great (379 – 395 A.D.).

In response to Theodosius outlawed paganism and made Christianity the official religion of the empire in 391 A.D. He called the Second Ecumenical Council, reaffirming the Nicene Creed, written under the reign of Constantine. As the last emperor to rule both east and west, he did away with the Vestal Virgins of Rome, outlawed the Olympic Games and dismissed the Oracle at Delphi which had existed long before the time of Alexander the Great. His grandson, Theodosius II (408 – 450 A.D.) rebuilt Hagia Sophia after it burned, established a university, and, fearing a barbarian threat, expanded the city’s walls in 413 A.D.; the new walls would be forty feet high and sixteen feet thick.

A number of weak emperors followed Theodosius II until Justinian (527 – 565 A.D.), the creator of the Justinian Code, came to power. By this time the city boasted over three hundred thousand residents. As emperor Justinian instituted a number of administrative reforms, tightening control of both the provinces and tax collection. He built a new cistern, a new palace, and a new Hagia Sophia and Hagia Irene, both destroyed during the Nika Revolt of 532 A.D. His most gifted advisor and intellectual equal was his wife Theodora, the daughter of a bear trainer at the Hippodrome. She is credited with influencing many imperial reforms: expansion of women’s rights in divorce, closure of all brothels, and the creation of convents for former prostitutes.

Under the leadership of his brilliant general Belisarius, Justinian expanded the empire to include North Africa, Spain and Italy. Sadly, he would be the last of the truly great emperors; the empire would fall into gradual decline after his death until the Ottoman Turks conquered the city in 1453 A.D. One of the darker moments during his reign was the Nika Revolt. It started as a riot at the hippodrome between two sport factions, the blues and greens. Both were angry at Justinian for some of his recent policy decisions and openly opposed his appearance at the games. The riot expanded to the streets where looting and fires broke out. The main gate of the imperial palace, the Senate house, public baths, and many residential houses and palaces were all destroyed.

Although initially choosing to flee the city, Justinian was convinced by his wife, to stay and fight: thirty thousand would die as a result. When the smoke cleared, the emperor saw an opportunity to clear away remnants of the past and make the city a center of civilization. Forty days later Justinian began the construction of a new church; a new Hagia Sophia. No expense was to be spared. He wanted the new church to be built on a grand scale -- a church no one would dare destroy. He brought in gold from Egypt, porphyry from Ephesus, white marble from Greece and precious stones from Syria and North Africa. The historian Procopius said: "it soars to a height to match the sky, and as if surging up from other buildings it stands as high and looks down on the remnants of the city … it exults in an indescribable beauty."

Over ten thousand workers would take almost six years to build it. Afterwards Justinian was reported to say, “Solomon, I have surpassed thee.” Near the height of his reign, Justinian’s city suffered an epidemic in 541 A.D. --the Black Death-- where over one hundred thousand of the city’s residents would die. Even Justinian wasn’t immune, although he survived. The economy of the empire would never completely recover. Two other emperors deserve mention: Leo III and Basil I. Leo III (717 – 741 A.D.) is best known for instituting iconoclasm, the destruction of all religious relics and icons, the city would lose monuments, mosaics and works of art, but he should also be remembered for saving the city.

When the Arabs lay siege to the city, he used a new weapon “Greek fire”, a flammable liquid to repel the invaders. It was comparable to napalm, and water was useless against it as it would only help to spread the flames. While his son Constantine V was equally successful, his grandson Leo IV, initially a moderate iconoclast, died shortly after assuming power, leaving the incompetent Constantine VI and his mother and regent Irene in power. Irene ruled with an iron hand, preferring treaties to warfare, aided by several purges of the military. Although she saw the return of religious icons (endearing her to the Roman church), her power over her son and the empire ended when she chose to have him blinded; she was exiled to the island of Lesbos.

Basil I (867- 886 A.D.), the Macedonian (although he had never set foot in Macedonia), saw a city and empire that has fallen into disrepair and set about a massive rebuilding program: Stone replaced wood, mosaics were restored, churches as well as a new imperial palace were constructed, and lastly, considerable lost territory was recovered. Much of the rebuilding, however, was lost during the Fourth Crusade (1202 -1204 A.D.) when the city was plundered and burned, not by the Muslims, but by the Christians who had initially been called to repel invaders but sacked the city themselves. Crusaders roamed the city, tombs were vandalized, churches desecrated, and Justinian’s sarcophagus was opened and his body flung aside. The city and the empire never recovered from the Crusades leaving them vulnerable for the Ottoman Turks in 1453 A.D. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

The Ancient City of Byzantium: The ancient city of Byzantium was founded by Greek colonists from Megara (one of the four districts of ancient Attica) around 657 BC. According to the 2nd century Roman historian Tacitus, it was built on the European side of the Strait of Bosporus. It was settled on the order of the “god of Delphi” who said to build “opposite the land of the blind”. This was in reference to the inhabitants of Chalcedon who had built their city on the eastern shore of the Strait. The west side was considered far more fertile and better suited for agriculture. Although the city accepted the alphabet, calendar, and cults of Megara, much of the city’s founding still remains unknown.

The region would remain important to the Greeks as well as the Romans. While it lay in a highly fertile area, the city was far more important due to its strategic location. Not only did it stand guard over the only entrance into the Black Sea but it also lay by a deep inlet known as “The Golden Horn”. The geography meant that the city could only be attacked from the west. Because of its location, the city became the center of the continued war between the Greeks and Persians. During the Greek and Persian Wars the Byzantines initially supported Darius I in his Scythian campaign. Byzantium provided Darius with ships, but turned against him later. Darius responded by destroying the city. The area was incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire in 513 BC.

During the Ionian Revolt, Greeks forces captured the city but were unable to maintain control, losing it again to the Persians. Many of the residents of both Byzantium and Chalcedon fled, fearing reprisals from the Persians. Eventually the Spartan general Pausanias was victorious against the Persians at the Battle of Plataea in 478 BC. Pausanias then traveled northward and conquered the city, becoming its governor. With the Persians so close, he made peace with the Persian king Xerxes I. Some historical accounts suggest that Pausanias offered to help the Persians to conquer Greece. He remained Byzantine governor until 470 BC when he was recalled by the Spartans.

Throughout the Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens the area had split loyalties. The Athenians wanted to control Byzantium because they needed to import grain through the strait from the Black Sea. The Spartans wanted take the city in order to stop the grain flow to Athens. Byzantium’s prosperous economy in the past had benefited Athens. Because of this the city had been made part of the Delian League. However the city had been made to p[ay high tributes to Athens. Now Athens was losing its war with Sparta. Byzantium switched sides in the conflict, choosing in 411 BC to support the Spartans. The Spartan general Clearchus seized the city, allowing Sparta to stop vital grain shipments through the strait to Athens.

The Athenian leader Alcibiades outwitted the Spartans in battle in 408 BC. The Spartan General Clearchus was forced to abandon Byzantium. The area again became Athenian. However Sparta later regained control when Lysander defeated the Athenians in 405 BC. This final defeat cut off the Athenian food supply. This forced Athens to surrender to Sparta in 404 BC. This ended the Peloponnesian War. The following year Byzantium faced a threat from the Thracians to the west. They sought help from Sparta who promptly took control of the city. Around 390 BC the city changed hands again when the Athenian general Thrasybulus ended Spartan power.

In 340 BCE Phillip II of Macedon laid siege to Byzantium. The city had initially asked Phillip for help when threatened by Thrace. However when Byzantium refused to side with Phillip in the military efforts he directed against Athens, Phillip attacked. However Phillip soon retreated after the Persian army threatened war. Phillip’s son Alexander the Great understood the strategic value of the city. Alexander annexed the area when he moved across the Bosporus into Asia Minor on his way to defeat Darius III and conquer the Persian Empire. The city would regain its independence under Alexander’s more feeble successors. Byzantium continued to exert control over trade through the strait. However when the island of Rhodes refused to pay exorbitant fees Byzantium was attempting to levy for passage through the strait, war erupted. However the war was quickly settled after the city agreed to reduce its harsh policies.

Byzantium became an ally of the Roman Empire and in many ways became very Romanized. Nonetheless Byzantium remained fairly independent. But Byzantium did provide a stopping-off point for Roman armies on their way to Asia Minor. The fishing, agriculture, and tributes from ships passing through the strait made it a valuable source of income for Rome. After the Emperor Commodus was assassinated in 192 AD a Roman civil war emerged over who would succeed him. Byzantium refused to support the contender who eventually won the civil war, Septimus Severus. Byzantium instead supported Pescennius Niger of Syria. Septimus Severus laid siege to and destroyed the city of Byzantium. Due to the influence of his son Caracalla Septimus would later regret his actions and rebuild the city.

When Emperor Diocletian divided the Roman Empire into a tetrarchy (rule by four) Byzantium fell into the eastern half, ruled by Diocletian. In 312 AD Constantine I (“the Great”) came into power in the western half of the Roman Empire. Constantine would eventually reunite an undivided Roman Empire when he defeated Licinius at the Battle of Chrysopolis in 324 AD. Constantine would build his new capital on the site of ancient Byzantium. “New Rome” would become the cultural and economic center of the Eastern Roman Empire. Upon Constantine’s death in 337 the city would be renamed Constantinople in his honor. The city itself maintained its role as an important part, if not the pivotal center of the Byzantine Empire for the next 1100 years until it was invaded and captured by the Ottoman Turks in 1453 AD [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

The City of Constantinople: The city of Constantinople is now known as Modern-day Istanbul. It was founded by Roman emperor Constantine I (“the Great”) in 324 AD at the ancient site of the city of Byzantium. Thereafter Constantinople acted as the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Eastern Roman Empire eventually became known as the “Byzantine Empire”, and it lasted for well over 1,000 years. Although the city suffered many attacks, prolonged sieges, and internal rebellions. It even suffered a period of occupation in the 13th century by the Fourth Crusaders. Its legendary defenses were the most formidable in both the ancient and medieval worlds. It could not however resist the mighty cannons of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II. Constantinople, the jewel and bastion of Christendom, was conquered, smashed, and looted on Tuesday, 29 May 1453 AD.

Constantinople had withstood many sieges and attacks over the centuries. These included most notably the attacks by Arab forces Arabs between 674 and 678 AD and again between 717 and 718 AD. The Bulgarians under Khans Krum who ruled from 802 to 814 AD and Symeon who ruled from 893 to 927 AD both attempted to attack the Byzantine capital. The ancient Rus, the descendants of Vikings based around Kiev attacked Constantinople in 860, 941, and 1043 AD. However all these attacks failed to breach the walls of Constantinople. Another major siege was instigated by the usurper Thomas the Slav between 821 and 823 AD. All of these attacks were unsuccessful thanks to the city’s location by the sea, its naval fleet, and the secret weapon of Greek Fire which was a highly inflammable petroleum based liquid. However the most important element which again and again saved Constantinople from all of these attacks was the protection afforded by the massive Theodosian Walls.

The city’s celebrated walls were a triple row of fortifications built during the reign of Theodosius II (408 to 450 AD). The walls protected the land side of the peninsula occupied by the city. They extended across the peninsula from the shores of the Sea of Marmara to the Golden Horn. They were eventually fully completed 439 AD. The walls stretched some 6½ kilometers (4 miles). Anyone attached Constantinople first faced a 20 meter (65 foot) wide and 7 meter (23 foot) deep moat or large ditch. The moat could be flooded with water fed from pipes when the city faced an external threat. Behind that was an outer wall which had a patrol track to oversee the moat. Behind this was a second wall which had regular towers and an interior terrace so as to provide a firing platform. From the platform the city’s defenders could shoot downward upon any enemy forces attacking the moat and first wall. Then behind that wall and platform was a third much more massive inner wall.

This final defensive wall was almost 5 meters (16 feet) thick, and 12 meters (40 feet) high. The wall afforded the defenders 96 towers which would project into any attacking force. Each tower was placed about 70 meters (230 feet) distant from another and reached a height of 20 meters (65 feet). The towers were either square or octagonal in form. Each could hold up to three artillery machines. The towers were so placed on the middle wall so as not to block the firing possibilities from the towers of the inner wall. The total distance between the outer ditch and inner wall was 60 meters (200 feet) while the total height difference was 30 meters (100 feet).

To take Constantinople an army would need to attack by both land and sea. However every army that attempted to do so attempts failed. It did not matter whose army, no matter what weapons and siege engines they launched at the city. All attempts to take Constantinople failed. In short, Constantinople had the greatest defenses in the medieval world and had proved impregnable. Well, not quite. After 800 years of resisting all comers, the city’s defenses were finally breached by the knights of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 AD. However it should be described that the attackers breached the city’s defenses by coming in through a carelessly left-open door. It was not because the fortifications themselves had failed in their purpose.

In 1260 AD Constantinople’s walls were repaired and rebuilt during the 1261 to 1282 reign of Emperor Michael VIII. The city remained the most impregnable fortress in the world. However their reputation did not provide them with any security against the ever-more ambitious Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Empire began in the late 13th century as a small Turkish emirate. It was founded by Osman in Eskishehir, which was in western Asia Minor. By the early 14th century CE the Ottoman Empire had already expanded into Thrace. With their capital at Adrianople further conquests included Thessaloniki and Serbia. In 1396 AD at Nikopolis on the Danubean Ottoman army defeated a Crusader army. Constantinople was the next target as the Byzantine Empire teetered on the brink of collapse. It became no more than a vassal state within the Ottoman Empire.

Constantinople was attacked in 1394 and 1422 AD but had still managed a successful defense of the city. Another Crusader army was defeated in 1444 AD at Varna near the Black Sea coast. However an even more resourceful and ambitious Sultan came to rule the Ottoman Empire, Mehmed II. Mehmed II ruled from 1451 to 1481 AD. He began extensive preparations such as building, extending, and occupying fortresses along the Bosporus. These were most notably at Rumeli Hisar and Anadolu in 1452 AD. Mehmed II was finally in a position to sweep away the Byzantines and their capital at Constantinople.

The crushing defeat the Byzantium Empire upon Crusader army at Varna in 1444 AD left the Byzantines alone, on their own. No significant help could be expected from the West where the Popes were already disgruntled with the Byzantine Empire’s unwillingness to reunite the Church and accept the supremacy of the West. The Venetians did send paltry reinforcements of two ships and 800 men to aid Constantinople in April 1453. Genoa promised another ship, and even the Pope later promised five armed ships. However by the Ottomans had by then already blockaded Constantinople. The people of the city could only stockpile food and weapons and hope their defenses would save them yet again.

According to the 15th-century Greek historian and eyewitness Georges Sphrantzes Constantinople’s defending army was composed of fewer than 5,000 men. This was a wholly insufficient number to adequately cover the length of the city’s walls which were 19 kilometers (12 miles) in total length. Worse still the once great Byzantine navy consisted of a mere 26 ships. Most of those belonged to the Italian colonists of the city. The Byzantines were hopelessly outnumbered in men, ships, and weapons. It seemed that only divine intervention could save them now. It was believed that just such intervention had saved the city in the many previous sieges over centuries gone by. Perhaps history would be repeated.

Then again there were also ominous tales of impending doom. There had been many prophesies that proclaimed the fall of Constantinople when the emperor was named Constantine. The Byzantine emperor at the time of the attack was Constantine XI who ruled from 1449 to 1453. Of course in the history of the Byzantine Empire quite a number of emperors had been named Constantine, and Constantinople had not fallen. Other prophesies claimed that Constantinople would fall during an eclipse of the moon. And there had indeed been an eclipse of the moon in the days leading up to the siege of 1453 AD.

The Emperor Constantine XI took personal charge of Constantinople’s defenses. He was accompanied by such notable military figures as Loukas Notaras, the Kantakouzenos brothers, Nikephoros Palaiologos, and the Genoese siege expert Giovanni Giustiniani. The Byzantines had catapults and Greek Fire, the highly inflammable napalm-like liquid which could be sprayed under pressure from ships or walls to torch an enemy. However the technology of warfare had relentlessly advanced over the centuries since the walls of Constantinople had been built by the Emperor Theodosian. Those Theodosian Walls were about to get their sternest test ever.