"Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven: Women in Ancient Egypt" by Anne K. Capel and Glenn E. Markoe (Editors).

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Oversized pictorial softcover. Publisher: Hudson Hills Press with Cincinnati Art Museum (1996). Pages: 240. Size: 12 x 9 x 1 inch; 2¾ pounds. Summary: Masterpieces of Egyptian art dating from 3000 to 300 B.C. have been brought together from great American museum and private collections to illuminate the role of women in ancient Egyptian society. This magnificent volume explores the full spectrum of women's lives and pursuits through three millennia of history. The dazzling centerpiece of Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven is devoted to more than one hundred objects assembled for the accompanying exhibition, organized by the Cincinnati Art Museum and shown also at the Brooklyn Museum.

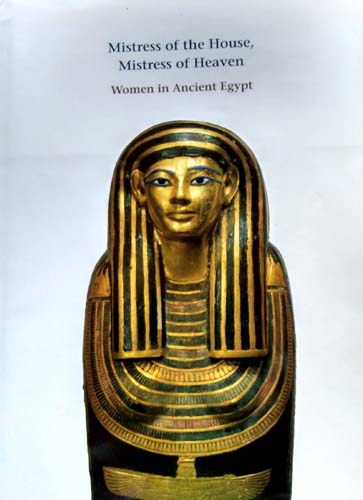

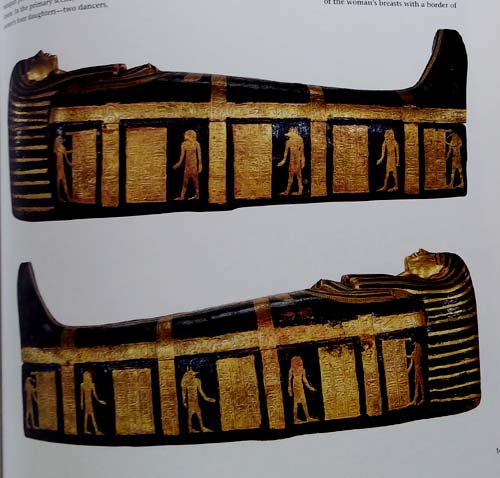

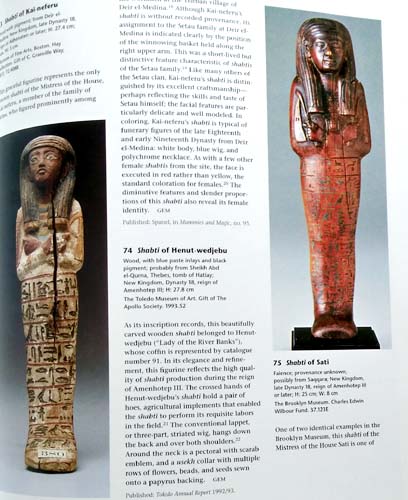

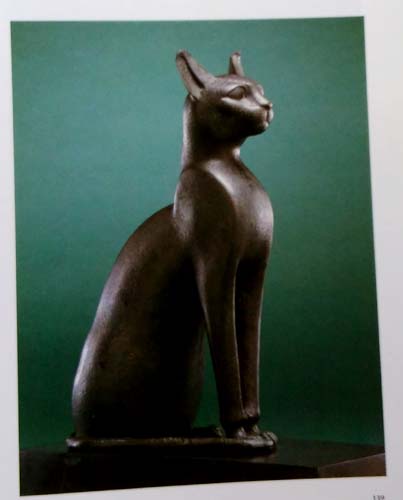

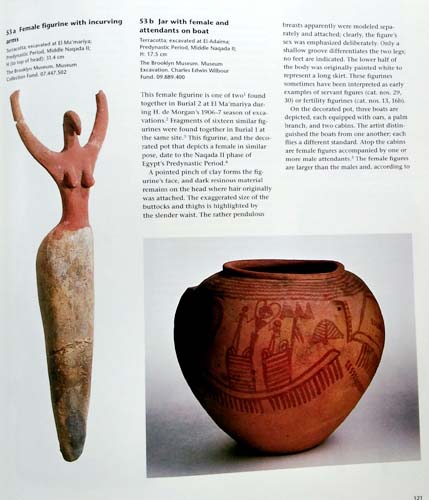

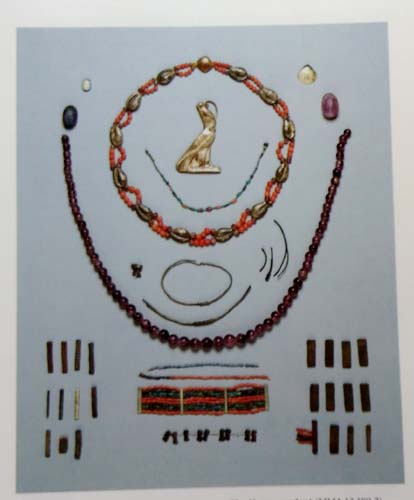

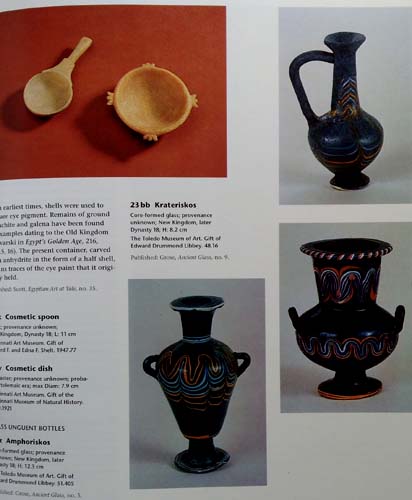

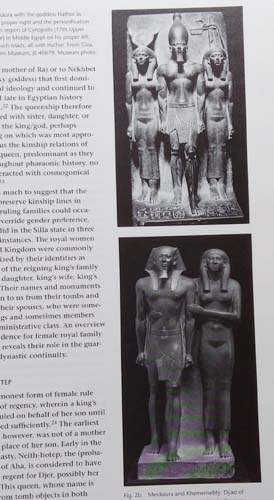

The exhibition was curated, and this volume edited, by Glenn Markoe, Curator of Classical and Near Eastern Art at Cincinnati, and Anne K. Capel, Guest Curator. Here are prime examples of stone and wood sculpture; wall painting; statuettes in bronze, terracotta, and faience; a mummy case; a painted and gilded wood coffin; jewelry in gold, stone and faience; and vessels and utensils in bronze, glass, and stone. Organized into sections devoted to Public and Private Lives, Female Royalty, Goddesses, and Afterlife, most are reproduced in full color, and all are accompanied by individual essays. The reader's understanding is further enriched by the inclusion of a chronology, map, bibliography, and index.

CONDITION: NEW. HUGE new softcover. Hudson Hills Press with Cincinnati Art Museum (1996) 240 pages. Unblemished in every respect except for faint shelfwear to the covers. Inside the book is pristine, the pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Condition is entirely consistent with new stock from a traditional brick-and-mortar shelved bookstore environment (such as Barnes & Noble, Borders, or B. Dalton for example), where otherwise "new" books might show faint signs of shelfwear, consequence of routine handling and simply being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #8977.1b.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Dazzling treasures illuminate women's lives through 3,000 years of ancient Egypt., Masterpieces of Egyptian art from great American collections illuminate the role of women in ancient Egypt.

REVIEW: Masterpieces of Egyptian art from great American collections illuminate the role of women in ancient Egyptian society. Here are stone and wood sculpture; wall painting; statuettes; mummy case and coffin; jewelry and utensils in gold, faience, bronze and glass.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Woman's Work: Some Occupations of Non-Royal Women as Depicted in Ancient Egyptian Art by Catharine H. Roehrig.

In Women Good and Bad Fortune are on Earth: Status and Roles of Women in Egyptian Culture by Betsy M. Bryan.

Catalogue of the Exhibition.

The Legal Status of Women in Ancient Egypt by Janet H. Johnson.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: In "Mistress Of The House, Mistress Of Heaven", masterpieces of Egyptian art dating from 3000 to 300 BC have been brought together from more than 25 American museum and private collections to illuminate the role of women in ancient Egyptian society. Mistress Of The House, Mistress Of Heaven explores the full spectrum of women's lives and pursuits in both historical and artistic milieus through Pharaonic Egypt's 3000 year history.

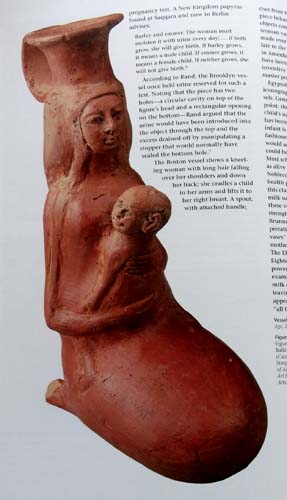

More than one hundred objects are reproduced in full color, and all are accompanied by brief and informative essays. Here are prime examples of stone and wood sculpture; wall painting; statuettes in bronze, terracotta, and faience; a mummy case; a painted and gilded wood coffin; jewelry in gold, stone, and faience; cosmetic and other vessels and utensils in bronze, glass, and stone. There are statues of individuals, couples, and family groups; genre figurines depicting daily activities; amulets, sacred cult objects, and burial assemblages.

These works of art are organized into sections devoted to Public and Private Lives; Female Royalty; Goddesses, and Afterlife. Slaves, freewomen, aristocrats, priestesses, queens, and goddesses are all represented in their Egyptian contexts. “Mistress of The House, Mistress of Heaven” is wonderfully illustrated with 117 color plates, 112 b/w illustrations, and a map. The essays are as engaging as they are informative. Highly recommended for art history, Egyptology, and women's studies reading lists. [Midwest Book Review].

REVIEW: The first-of-its-kind exhibit cataloged here focuses on the women of Egypt from all levels of society in works compiled strictly from American collections by American curators. Because the quantity of written records is limited (though enormous in comparison to most early societies), there is still much guesswork involved in determining the place women held in Egyptian society. It is clear that, unlike most ancient and not-so-ancient societies, Egypt conferred on women the legal right to own property and to barter their own goods, which means a larger record for current study. The essays here are both erudite and fascinating to read; the illustrations are clear and well presented in conjunction with the text. An excellent new resource for public and academic collections about ancient Egypt and its art as well as for women's studies collections; highly recommended. [Library Journal].

REVIEW: From goddesses and queens to housewives and servants, the roles of women through almost four millennia of ancient Egyptian history [are] explored in a major exhibition of almost 250 objects. Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven: Women in Ancient Egypt will be on view at The Brooklyn Museum. The Brooklyn Museum is the only other venue for the exhibition, which was organized by the Cincinnati Art Museum and comprises works from more than 25 of the most important public and private collections in the United States, among them some 20 pieces from The Brooklyn Museum’s world-famous holdings.

Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven includes depictions of women, as well as the objects that they used. Among them are the representations of Hatshepsut, a Queen who ruled Egypt along with her nephew and stepson Thutmose III; a statue of the important God’s wife of Amun, Amenivdes I; the exquisitely painted mummy cartonnage of the Mistress of the House and Songstress of Amen, Neskahonsupakhered; and Akhenaten’s principal wife, Nefertiti, as well as other Egyptian queens. Also on display will be gold, silver, and faience jewelry; a pair of rare Old Kingdom statues from a tomb in Giza; amulets; cosmetic vessels; and a wide range of objects relating to goddesses, including Mut, whose temple at Karnak in Luxor is being excavated by a team led by The Brooklyn Museum.

Although ancient Egypt was a male-dominated society, women had many rights denied to females in other Near Eastern cultures. The country was almost always ruled by a king and a male bureaucracy, but women were able to acquire, own, and dispose of property; act as plaintiffs, defendants, or witnesses in a court of law; engage in business dealings; hold such positions as funerary priestesses, musicians, and singers; and in some dynastic periods even occupied supervisory positions. Occasionally women attained great prominence and power.

Despite these unusual civil liberties, attitudes toward women were often ambivalent, particularly in the preoccupation with the destructive potential of goddesses. For example, it was believed that if the lioness-headed Sakhmet was sufficiently enraged she might unleash terrible powers against Egypt or, worse, abandon it. Elaborate rituals were devised to appease her that included music, song, dance, stories, and drink.

The exhibition will consist of four sections which illuminate the lives of women in ancient Egypt by focusing on Private and Public Life, Queens and Female Royalty, Female Deities, and Women in the Afterlife. Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven: Women in Ancient Egypt was organized by Glenn Markoe, Curator of Classical and Near Eastern Art at the Cincinnati Art Museum, and Guest Curator of Egyptian Art, Anne Capel. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue that includes essays by three noted Egyptologists as well as entries by Richard Fazzini, Chair, Department of Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Middle Eastern Art at The Brooklyn Museum, where he has coordinated the exhibition. [Brooklyn Museum].

REVIEW: "Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven: Women in Ancient Egypt" opens today at the newly renamed Brooklyn Museum of Art. The exhibition, which originated at the Cincinnati Art Museum, could hardly have found a more sympathetic berth than Brooklyn, whose Egyptian collection is world renowned. As at the Met, a visitor need only move from the small visiting show to the museum's permanent galleries to see an epic narrative unfold. But "Women in Ancient Egypt" does more than merely complement a survey collection. It adds something new. It takes a specific aspect of art, filters it through a fine-tuned, implicitly critical lens of social history and reveals unsuspected facets of an ancient culture that can easily seem at once too familiar and too monolithic to be fully grasped.

Such a historical approach, while standard practice for decades in academia, is still something of a novelty in the museum world. And despite having few models to emulate (the 1995 exhibition ''Pandora's Box: Women in Classical Greece'' at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore was one), ''Women in Ancient Egypt'' does its job with aplomb. It steers a smooth course between an outdated view of the Egyptian woman as a kind of dynastic fashion plate and a newer theoretical take that threatens to reduce her to a mere pawn in a patriarchal game. Instead, the more than 200 objects gathered here -- many of them beautiful, some of them prosaic, a few simply bizarre -- confirm the complexity of her identity: as both mistress and servant, mother and mother-goddess, marital commodity and property owner, and as an individual seeking fulfillment in this life and salvation in the next.

The show, which is drawn entirely from American collections, opens with an Old Kingdom limestone effigy of a man and a woman standing together. Their torsos are sensually modeled, their facial features regular but individualized, melding the ideal with the real. Their pose is unabashedly affectionate: her arm encircles his waist, his hand passes over her shoulder and touches her breast. But distinctions between the figures are marked. The man, in every way the dominant figure, is a full head taller than his mate. Where his face is upward-looking and warmed by a faint but self-confident smile, hers seems pensive. She gazes slightly downward and to the side, tensed, as if listening for something. What could it be? The cry of unruly children? The clatter of plates in a kitchen? The hum of weaving in a distant room? The pulse of life beating in the earth?

Much about the woman's status can be read here. Variations in the heights of figures are often a visual code for rank in the social hierarchy. While the man in this case is identified by name in an inscription, the woman is not. And contemporary documents suggest that if this pair were married (there is no clear proof that they are), the woman would have fewer legal rights than her husband. In fact, "Women in Ancient Egypt," organized by Glenn Markoe, Anne Capel and Richard Fazzini, does much to upset the long-held assumption that Egyptian society was exceptional among ancient cultures for its sexual parity. Recurrent images in the show of women breast-feeding children, picking fruit, grinding grain, carrying baskets and dressing one another's hair confirm that while men moved in a public sphere, women of all classes were traditionally restricted to the home.

Traditions, of course, exist to be modified and broken. And so they often were in ancient Egypt, as least at the elite levels of society dealt with in this show, permitting certain women to assume political and spiritual power. Those of privileged rank, for example, could acquire material wealth in the form of real estate and luxury items. A wealth of jewelry survives from burials, and samples in the show range from necklaces of amethyst, gold and lapis lazuli to razor-thin silver torques, and from amulets in the form of shells or animals to effigies of protective goddesses.

There were also career options, limited to be sure. Women might find work as professional mourners -- one sees a cluster of them gesturing and wailing in a funerary carving -- or as performers in court and temple rituals. In a relief from the tomb of a Middle Kingdom queen, female musicians raise frondlike hands in the air as they clap out a rhythm. And a few individuals assumed the role of female pharaohs. The most famous of these was Hatshepsut, builder of a vast mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. In a large pink granite portrait statue in the show she wears the accouterments of a male king -- a false beard, a short kilt -- but an inscription refers to her as the daughter of the sun god.

Hatshepsut's unorthodox rise to power apparently caused few qualms among her subjects -- her reign from 1486 to 1468 B.C. was a time of marked prosperity for Egypt -- in part, perhaps, because female deities had long populated the Egyptian pantheon and were familiar presences in its art. Some goddesses routinely took human form, as in the case of Maat, an embodiment of natural harmony, who is seen as a small bronze figure perched, with her knees drawn up, on an altar. Others were depicted as half-animal: Hathor had the head of a cow; Sekhmet, both revered and feared for her mercurial disposition, that of a lion. The popular Taweret was a one-person menagerie, with the head of a hippopotamus, the body of a crocodile, the paws of a lion, human breasts and a million-watt grin guaranteed to scare off ill-intentioned spirits.

These composite deities, in whom the fantastic and the everyday effortlessly merge, are among the unforgettable creations of world art. Yet the images in the show that linger longest in the mind are those that feel most intimately human. It would be hard to find a vision more tender than that in the relief carving of Queen Nefertiti kissing her young daughter, their lips meeting as a disembodied celestial hand offers an ankh, the emblem of life. Nor is there anything in the Metropolitan's Nefertiti show to surpass the colossal head of a young queen, carved in dark gray-green chlorite, on view here.

This breathtaking fragment, probably once attached to a sphinx's body, made its way to Italy in antiquity and was found at Hadrian's villa near Rome. The young woman's nose is missing, her chin chipped and repaired, but even in ruined condition her wide-eyed, candid visage, with its broad mouth and skin buffed to a soft sheen, palpitates with life. As it happens, this treasure is in the permanent collection of the Brooklyn Museum itself, and is a reminder that "Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven: Women in Ancient Egypt" arrives here on a note of special fanfare. It marks the beginning of the museum's 18-month celebration of its own august past: 175 years as an institution (it was dedicated as a library in 1825 by the Marquis de Lafayette) and a century of residence in its splendid McKim, Mead & White Beaux Arts premises on Eastern Parkway.

Thus, the confluence of a quietly revelatory traveling show (Brooklyn is the only stop outside Cincinnati) and a fabled permanent collection does double duty. It not only offers a golden opportunity to experience an ancient culture in depth, but also ushers a great New York museum into the next century of its history. [New York Times].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Ancient Egyptian art was the star attraction of the Mediterranean world for 3000 years, only for some of it to be transported to various museums across the world. This book examines those scenes in over 25 American museums as well as private collections which serve to shed light on the role of Ancient Egyptian women in their society. Objects such as mummy cases, coffins, statues and other sacred items also hold much information. The book contains essays by Egyptologists Janet H. Johnson, Catherine H. Roehrig and Betsy M. Bryan. A chronological index, map, beautiful photos, bibliography and index have also been included. It is an excellent book, recommended for all serious students and scholars to have in their private libraries.

REVIEW: An interesting view of women in Ancient Egypt. Covering females from their occupations, family, religion, royalty, and the afterlife, this book has much to say about the females in Egypt. It was a great exhibit put on at the Cincinnati Art Museum; a showcase of the finest pieces of Egyptian art from the United States.

REVIEW: If you are at all interested in ancient Egypt, this is a good book for you. Interspersed with essays about the lives of women in ancient Egypt are photos of fragments of papyrus, statues, jewelry and paintings illustrating the roles of royal and "ordinary" women and female servants. While the discussions of the relationships between royal wives and their husbands could be a little hard to follow, it is clear that women were revered for what they could bring to a marriage and that they had political and social clout of their own.

REVIEW: An excellent text, profusely illustrated. Valuable to those interested in history, women's studies, textiles, Egyptology and is generally an interesting read.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

REVIEW: Whilst the concept of a career choice for women is a relatively modern phenomenon, the situation in ancient Egypt was rather different. For some three thousand years the women who lived on the banks of the Nile enjoyed a form of equality which has rarely been equaled. In order to understand their relatively enlightened attitudes toward sexual equality, it is important to realize that the Egyptians viewed their universe as a complete duality of male and female. Giving balance and order to all things was the female deity Maat, symbol of cosmic harmony by whose rules the pharaoh must govern.

The Egyptians recognized female violence in all its forms, their queens even portrayed crushing their enemies, executing prisoners or firing arrows at male opponents as well as the non-royal women who stab and overpower invading soldiers. Although such scenes are often disregarded as illustrating 'fictional' or ritual events, the literary and archaeological evidence is less easy to dismiss. Royal women undertake military campaigns whilst others are decorated for their active role in conflict. Women were regarded as sufficiently threatening to be listed as 'enemies of the state', and female graves containing weapons are found throughout the three millennia of Egyptian history.

Although by no means a race of Amazons, their ability to exercise varying degrees of power and self-determination was most unusual in the ancient world, which set such great store by male prowess, as if acknowledging the same in women would make them less able to fulfill their expected roles as wife and mother. Indeed, neighboring countries were clearly shocked by the relative freedom of Egyptian women and, describing how they 'attended market and took part in trading whereas men sat and home and did the weaving', the Greek historian Herodotus believed the Egyptians 'have reversed the ordinary practices of mankind'.

And women are indeed portrayed in a very public way alongside men at every level of society, from coordinating ritual events to undertaking manual work. One woman steering a cargo ship even reprimands the man who brings her a meal with the words, 'Don't obstruct my face while I am putting to shore' (the ancient version of that familiar conversation 'get out of my way whilst I'm doing something important'). Egyptian women also enjoyed a surprising degree of financial independence, with surviving accounts and contracts showing that women received the same pay rations as men for undertaking the same job - something the modern world has yet to achieve. As well as the royal women who controlled the treasury and owned their own estates and workshops, non-royal women as independent citizens could also own their own property, buy and sell it, make wills and even choose which of their children would inherit.

The most common female title 'Lady of the House' involved running the home and bearing children, and indeed women of all social classes were defined as wives and mothers first and foremost. Yet freed from the necessity of producing large numbers of offspring as an extra source of labor, wealthier women also had alternative 'career choices'. After being bathed, depilated and doused in sweet heavy perfumes, queens and commoners alike are portrayed sitting patiently before their hairdressers, although it is equally clear that wigmakers enjoyed a brisk trade. The wealthy also employed manicurists and even female make-up artists, whose title translates literally as 'painter of her mouth'. Yet the most familiar form of cosmetic, also worn by men, was the black eye paint which reduced the glare of the sun, repelled flies and looked rather good.

Dressing in whatever style of linen garment was fashionable, from the tight-fitting dresses of the Old Kingdom (c.2686 - 2181 BC) to the flowing finery of the New Kingdom (c.1550 - 1069 BC), status was indicated by the fine quality of the linen, whose generally plain appearance could be embellished with colored panels, ornamental stitching or beadwork. Finishing touches were added with various items of jewelry, from headbands, wig ornaments, earrings, chokers and necklaces to armlets, bracelets, rings, belts and anklets made of gold, semi-precious stones and glazed beads. With the wealthy 'lady of the house' swathed in fine linen, bedecked in all manner of jewelry, her face boldly painted and wearing hair which more than likely used to belong to someone else, both male and female servants tended to her daily needs. They also looked after her children, did the cleaning and prepared the food, although interestingly the laundry was generally done by men.

Freed from such mundane tasks herself, the woman could enjoy all manner of relaxation, listening to music, eating good food and drinking fine wine. One female party-goer even asked for 'eighteen cups of wine for my insides are as dry as straw'. Women are also portrayed with their pets, playing board games, strolling in carefully tended gardens or touring their estates. Often traveling by river, shorter journeys were also made by carrying-chair or, for greater speed, women are even shown driving their own chariots.

The status and privileges enjoyed by the wealthy were a direct result of their relationship with the king, and their own abilities helping to administer the country. Although the vast majority of such officials were men, women did sometimes hold high office. As 'Controller of the Affairs of the Kiltwearers', Queen Hetepheres II ran the civil service and, as well as overseers, governors and judges, two women even achieved the rank of vizier (prime minister). This was the highest administrative title below that of pharaoh, which they also managed on no fewer than six occasions.

Egypt's first female king was the shadowy Neithikret (2148-44 BC), remembered in later times as 'the bravest and most beautiful woman of her time'. The next woman to rule as king was Sobeknefru (1787-1783 BC) who was portrayed wearing the royal headcloth and kilt over her otherwise female dress. A similar pattern emerged some three centuries later when one of Egypt's most famous pharaohs, Hatshepsut, again assumes traditional kingly regalia. During her fifteen year reign (1473-1458 BC) she mounted at least one military campaign and initiated a number of impressive building projects, including her superb funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari.

But whilst Hatshepsut's credentials as the daughter of a king are well attested, the origins of the fourth female pharaoh remain highly controversial. Yet there is far more to the famous Nefertiti than her dewy-eyed portrait bust. Actively involved in her husband Akhenaten's restructuring policies, she is shown wearing kingly regalia, executing foreign prisoners and, as some Egyptologists believe, ruling independently as king following the death of her husband c.1336 BC. Following the death of her husband Seti II in 1194 BC, Tawosret took the throne for herself and, over a thousand years later, the last of Egypt's female pharaohs, the great Cleopatra VII, restored Egypt's fortunes until her eventual suicide in 30 BC marks the notional end of ancient Egypt.

But with the 'top job' far more commonly held by a man, the most influential women were his mother, sisters, wives and daughters. Yet, once again, many clearly achieved significant amounts of power as reflected by the scale of monuments set up in their name. Regarded as the fourth pyramid of Giza, the huge tomb complex of Queen Khentkawes (c.2500 BC) reflects her status as both the daughter and mother of kings. The royal women of the Middle Kingdom pharaohs were again given sumptuous burials within pyramid complexes, with the gorgeous jewelry of Queen Weret discovered as recently as 1995.

During Egypt's 'Golden Age', (the New Kingdom, circa 1550-1069 BC), a whole series of such women are attested, beginning with Ahhotep whose bravery was rewarded with full military honors. Later, the incomparable Queen Tiy rose from her provincial beginnings as a commoner to become 'great royal wife' of Amenhotep III (1390-1352 BC), even conducting her own diplomatic correspondence with neighboring states.

Pharaohs also had a host of 'minor wives' but, since succession did not automatically pass to the eldest son, such women are known to have plotted to assassinate their royal husbands and put their sons on the throne. Given their ability to directly affect the succession, the term 'minor wife' seems infinitely preferable to the archaic term 'concubine'. Yet even the word 'wife' can be problematic, since there is no evidence for any kind of legal or religious marriage ceremony in ancient Egypt. As far as it is possible to tell, if a couple wanted to be together, the families would hold a big party, presents would be given and the couple would set up home, the woman becoming a 'lady of the house' and hopefully producing children.

Whilst most chose partners of a similar background and locality, some royal women came from as far afield as Babylon and were used to seal diplomatic relations. Amenhotep III described the arrival of a Syrian princess and her 317 female attendants as 'a marvel', and even wrote to his vassals - 'I am sending you my official to fetch beautiful women, to which I the king will say good. So send very beautiful women - but none with shrill voices'! Such women were given the title 'ornament of the king', chosen for their grace and beauty to entertain with singing and dancing.

But far from being closeted away for the king's private amusement, such women were important members of court and took an active part in royal functions, state events and religious ceremonies. With the wives and daughters of officials also shown playing the harp and singing to their menfolk, women seem to have received musical training. In one tomb scene of around 2000 BC a priest is giving a kind of master class in how to play the sistrum (sacred rattle), as temples often employed their own female musical troupe to entertain the gods as part of the daily ritual.

n fact, other than housewife and mother, the most common 'career' for women was the priesthood, serving male and female deities. The title, 'God's Wife', held by royal women, also brought with it tremendous political power second only to the king, for whom they could even deputize. The royal cult also had its female priestesses, with women acting alongside men in jubilee ceremonies and, as well as earning their livings as professional mourners, they occasionally functioned as funerary priests.

Their ability to undertake certain tasks would be even further enhanced if they could read and write but, with less than 2% of ancient Egyptian society known to be literate, the percentage of women with these skills would be even smaller. Although it is often stated that there is no evidence for any women being able to read or write, some are shown reading documents. Literacy would also be necessary for them to undertake duties which at times included prime minister, overseer, steward and even doctor, with the lady Peseshet predating Elizabeth Garret Anderson by some 4,000 years.

By Graeco-Roman times women's literacy is relatively common, the mummy of the young woman Hermione inscribed with her profession 'teacher of Greek grammar'. A brilliant linguist herself, Cleopatra VII endowed the Great Library at Alexandria, the intellectual capital of the ancient world where female lecturers are known to have participated alongside their male colleagues. Yet an equality which had existed for millennia was ended by Christianity - the philosopher Hypatia was brutally murdered by monks in 415 AD as a graphic demonstration of their beliefs. With the concept that 'a woman's place is in the home' remaining largely unquestioned for the next 1,500 years, the relative freedom of ancient Egyptian women was forgotten. Yet these active, independent individuals had enjoyed a legal equality with men that their sisters in the modern world did not manage until the 20th century, and a financial equality that many have yet to achieve. [BBC].

REVIEW: Pyramids, temples, tombs, vibrant and decadent art comes to mind at the mere mention of Ancient Egypt, works of art that found their function primarily in the sacred sphere. Nearly every aspect of this ancient culture had direct relations to the prevailing religious traditions with the most obvious documentation of this passed down through the paintings and cut reliefs preserved in tombs, temples, monuments, papyri, stelae and various other objects. Throughout the span of ancient Egyptian civilization the distinctive artistic tradition presents a predominantly male view of customs, rituals, and overall presentation of this society. That is not to say that women were not depicted, however, in most cases they served as ancillary figures to the male tomb owner or king, often being listed as the ‘wife’ of their companion. Within this stratified society one finds divisions between class level as well as gender, often with the stronger division being that of class difference. The volume of archeological evidence from these ancient peoples stems from the royal and non-royal elite, with very little evidence remaining related to the poorer classes. Thus, it is that the evidence of women’s roles throughout the scope of Ancient Egypt is most often relegated to that of the elite.

The majority of non-royal archeological remnants are constructed by and inscribed with the names of males within administrative positions; very few women achieved status and power through these elite roles and only six women are documented to have achieved the position of pharaoh. The most prominent title accorded to women throughout the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, as evidenced on funerary monuments, stelae, etc., is that of “mistress of the house.” Women were regarded within in the Ancient Egyptian society for their roles as child bearer and keeper of the household. It is important to note that women had the ability to own and sell land, construct wills, and determine inheritance of their children. However, it is within another realm of the arts, preserved through the pictorial representations found upon almost every manner of artistic surface, the realm of music, in which women were able to gain prestige and status. It is within the tradition of music, both sacred and secular, that women of Ancient Egypt were accorded titles of status that remained unparalleled for their gender elsewhere in the public sphere.

Like other forms of artistic development in Ancient Egypt, music primarily functioned within the religious sphere; even secular music often had its roots in the religious tradition of the society. Men and women both served as musicians, with evidence dating from the Predynastic period through the Graeco-Roman era. With no extant notated music from the ancient times,[1]archeologists and musicologists have had to rely upon the data provided through pictorial representations and, if applicable, their accompanying hieroglyphic text, found upon temples, palaces, tombs, stelae, papyri, ostrakon, as well as extant instruments to construct their knowledge of the music of the Ancient Egyptians.

Extant evidence shows that music permeated nearly every aspect of the lives of these ancient peoples. Music was present in celebrations and festivals held in temples and palaces, banquets, for both the gods and in the pharaoh’s honor. It featured prominently as an aspect of mourning in funerary scenes, used for entertainment in the home, the fields and was also featured in military processions. In all these settings, except military, one can find representations of women participating, indeed often as the main participators in the making of music, featured in the roles of singers, instrumentalists, directors of musical ensembles and dancers.

Women are featured, as well as their male counterparts, as music makers, from even the earliest representations. It is in the variety of instruments and gender that determined how certain instruments were allotted. It is in the composition of musical ensembles that one observes innovation and variation throughout the eras of the Ancient Egyptian civilization’s major historical periods of the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, and New Kingdom. One can observe the roles of women within the realm of music in the most prolific representations of them as musicians in the New Kingdom, 1550 – 945 BC.

Music, as depicted in the New Kingdom, is blessed with a generous amount of documentation, with even better preserved material than found in the Old and Middle Kingdoms, and include accompanying inscriptions that provide a more descriptive caption to the images they are connected with. In these scenes women are featured playing a wider variety of instruments than in previous eras, with few restrictions to instruments not thought to be suitable for their gender. Stringed instruments such as lutes, lyres, and the various forms of harp (shoulder, standing, arched, and curved), wind instruments including flutes, single and double oboes, and various percussion instruments including the rectangular frame drum, round frame drum, clapsticks, and sistrum are all performed by females as well as males during this kingdom.

It is important to note that the double oboe and the rectangular frame drum are represented as being only performed by female musicians throughout the New Kingdom. Scenes of music making from the New Kingdom have all but abandoned the long standing images of a female relative of the deceased playing the harp for the tomb owner to that of groups of women performing music. Throughout New Kingdom representation, these groups of female musicians are featured in temple service, festivals and banquets, attached to palaces, temples, and private estates.

Music, having strong ties to the traditional religious practices, finds the majority of its representation in the realm of sacred artistic depiction. From the earliest times one finds evidence of women serving as priestesses throughout the temples. Depicted in ritual function, these women often yield the traditional Egyptian sitstrum and menat accompanying their ritual chants and songs to the particular deity they serve. It was believed that music would “open the doors of heaven so that the gods may go forth pure” as well as pleasing and placating the deities so that they might bestow their benevolence upon their people.

One of the most widespread roles for female musicians was that of chantress, linking their musical activities to the religious temples service. Two documented organizations of performers attached to temples have survived through the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but are accorded significantly more documentation in the New Kingdom, the “hst” and “šm‘yt” (though the šm‘yt is better documented). Both of these ensembles feature female musicians, primarily those who are of the non-royal elite and royal family members. Women are recognized for their membership within these groups through titles found with their names as represented on coffins, tomb biographies, letters and administrative documents.

The “šm‘yt” is divided into four groups of musicians, termed phyles, who served the temple on a part time, rotating cycle under the supervision of a woman with the title of “great one [of the musician].” The phyles were then overseen by a high priest. Both the “šm‘yt” and “hst” functioned as entertainment for the gods, chanting, singing and accompanying the vocal music with the sistra and menat. Often women serving in these ensembles were honored with the title “Chantress of” followed by the particular deity she served; the most common title during the New Kingdom was that of “Chantress of Amon.” It deserves mentioning that the position of temple musician or chantress was on a voluntary basis unlike the professional women ensembles elsewhere designated within the Ancient Egyptian culture, that were accorded a monetary compensation for their music.

Women’s service in festivals, banquets, funerals and other musical entertainment is best documented in funerary representations that preserve such entertainments so that the tomb owner may enjoy them in the afterlife. The most well documented group of musicians associated with funerary practices, dating back to the Old Kingdom, is that of the “hnr.” This group is known for its musical performances composed of dancing and clapping in accompaniment to their performance of secular and sacred songs. By the age of the New Kingdom this group was declining in its representation but its traditions are still maintained. It is more common in the New Kingdom evidence to see groups composed entirely of women, with much evidence dating from the Amarna period.

Orchestras composed entirely of women and bands of female musicians that were attached to elite estates and the palace of Akhenaton were featured prominently on monuments throughout Tell el Amarna. Representations of the sed festivals from the temple of Akhenaton provide excellent and explicit evidence of women as musicians. A wide variety of instruments are featured in such art works including lutes, lyres, harps, clappers, oboes, flutes, and drums, all of which are played upon by women (as well as men). It must be noted that it is generally evident throughout all musical representation that the vocal music was the primary instrument and was accompanied by string, wind, and percussive instruments.

Another common representation found in funerary documentation is that of a harpist entertaining the tomb owner. This manner of musical depiction is featured throughout the scope of Ancient Egyptian civilization but as previously stated is given more prominence during the New Kingdom. It is the lady of the house that is seen in this role, serving as musician to entertain the deceased. Scholars believe these representations to be echoes of daily life enjoyed by the tomb owner which follows him into the afterlife. Similarly other daily life scenes found in tombs feature a musician entertaining workers in the fields during a harvest. In all of these representations women are featured as performers, as well as men. Frequently, throughout the New Kingdom the bulk of such scenes are predominated by female musicians.

The status of women as musicians was accorded more and more prestige as the eras of Ancient Egyptian civilization progressed. Scholars placed early association of women as musicians in a poor light, believing them to be fallen women but that is now believed to not be the case. The New Kingdom shows a marked increase in professionalism in the organization and performance of music events. The presence of professional groups composed entirely of female musicians is an “indication of the prestige [that had come to be] associated with musical training.” Evidence of such status can be traced through the elaborate and beautiful coffins that remain from female musicians. Several groups of the “šm‘yt” of Osiris, Isis, Horus, Mut and Amun were accorded the honor of burial at the sacred site of Abydos. It deserves mentioning that several gods and goddesses were associated with music, most notably Hathor and Bes. Thus music was revered for its divine associations and it was honorable for one to attain the skills needed to become a musician in the Ancient Egyptian culture.

Women feature prominently in all manners of documentation of the musical tradition of the Ancient Egyptians. They are honored through titles recorded in texts found on their funerary monuments and the monuments of others, as well as the pictorial representations of women as musicians in temples, palaces, banquets, festivals, and private settings. The overwhelming evidence of primarily all female musical ensembles during New Kingdom art gives evidence to the prestige of women in the public sphere through their roles as musicians. No where else within the public sphere are women featured as persons of status and honor with the very rare attainment of administrative positions by women. Women, attain honor and status equal to that of their male counterparts in their roles as musicians of both secular and sacred music within ancient Egyptian society.

SHIPPING & RETURNS/REFUNDS: We always ship books domestically (within the USA) via USPS INSURED media mail (“book rate”). Most international orders cost an additional $19.99 to $53.99 for an insured shipment in a heavily padded mailer. However this book is quite large and heavy, too large to fit into a flat rate mailer. Therefore the shipping costs are somewhat higher than what is otherwise ordinary. There is also a discount program which can cut postage costs by 50% to 75% if you’re buying about half-a-dozen books or more (5 kilos+). Our postage charges are as reasonable as USPS rates allow.

ADDITIONAL PURCHASES do receive a VERY LARGE discount, typically about $5 per book (for each additional book after the first) so as to reward you for the economies of combined shipping/insurance costs. Your purchase will ordinarily be shipped within 48 hours of payment. We package as well as anyone in the business, with lots of protective padding and containers. All of our shipments are fully insured against loss, and our shipping rates include the cost of this coverage (through stamps.com, Shipsaver.com, the USPS, UPS, or Fed-Ex).

Please note for international purchasers we will do everything we can to minimize your liability for VAT and/or duties. But we cannot assume any responsibility or liability for whatever taxes or duties may be levied on your purchase by the country of your residence. If you don’t like the tax and duty schemes your government imposes, please complain to them. We have no ability to influence or moderate your country’s tax/duty schemes. International tracking is provided free by the USPS for certain countries, other countries are at additional cost. We do offer U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail, Registered Mail, and Express Mail for both international and domestic shipments, as well United Parcel Service (UPS) and Federal Express (Fed-Ex). Please ask for a rate quotation. We will accept whatever payment method you are most comfortable with.

If upon receipt of the item you are disappointed for any reason whatever, I offer a no questions asked 30-day return policy. Send it back, I will give you a complete refund of the purchase price; 1) less our original shipping/insurance costs, 2) less any non-refundable fees imposed by eBay. Please note that though they generally do, eBay may not always refund payment processing fees on returns beyond a 30-day purchase window. So except for shipping costs and any payment processing fees not refunded by eBay, we will refund all proceeds from the sale of a return item. Obviously we have no ability to influence, modify or waive eBay policies.

ABOUT US: Prior to our retirement we used to travel to Eastern Europe and Central Asia several times a year seeking antique gemstones and jewelry from the globe’s most prolific gemstone producing and cutting centers. Most of the items we offer came from acquisitions we made in Eastern Europe, India, and from the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean/Near East) during these years from various institutions and dealers. Much of what we generate on Etsy, Amazon and Ebay goes to support worthy institutions in Europe and Asia connected with Anthropology and Archaeology. Though we have a collection of ancient coins numbering in the tens of thousands, our primary interests are ancient/antique jewelry and gemstones, a reflection of our academic backgrounds.

Though perhaps difficult to find in the USA, in Eastern Europe and Central Asia antique gemstones are commonly dismounted from old, broken settings – the gold reused – the gemstones recut and reset. Before these gorgeous antique gemstones are recut, we try to acquire the best of them in their original, antique, hand-finished state – most of them originally crafted a century or more ago. We believe that the work created by these long-gone master artisans is worth protecting and preserving rather than destroying this heritage of antique gemstones by recutting the original work out of existence. That by preserving their work, in a sense, we are preserving their lives and the legacy they left for modern times. Far better to appreciate their craft than to destroy it with modern cutting.

Not everyone agrees – fully 95% or more of the antique gemstones which come into these marketplaces are recut, and the heritage of the past lost. But if you agree with us that the past is worth protecting, and that past lives and the produce of those lives still matters today, consider buying an antique, hand cut, natural gemstone rather than one of the mass-produced machine cut (often synthetic or “lab produced”) gemstones which dominate the market today. We can set most any antique gemstone you purchase from us in your choice of styles and metals ranging from rings to pendants to earrings and bracelets; in sterling silver, 14kt solid gold, and 14kt gold fill. When you purchase from us, you can count on quick shipping and careful, secure packaging. We would be happy to provide you with a certificate/guarantee of authenticity for any item you purchase from us. There is a $3 fee for mailing under separate cover. I will always respond to every inquiry whether via email or eBay message, so please feel free to write.