|

|

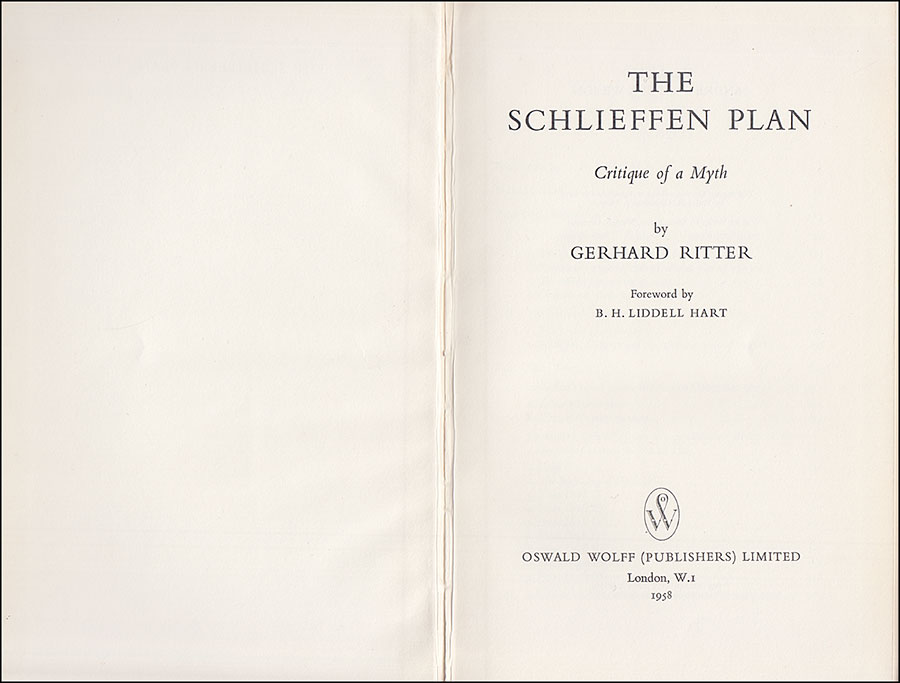

The Schlieffen Plan

Critique of a Myth

by

Gerhard Ritter

Translated by

Andrew and Eva Wilson

Foreword by

B. H. Liddell Hart

|

|

|

|

This is

the 1958 First English Edition [This] book is “a

source of fundamental importance for understanding the causes of

the First World War.

All existing accounts must now be revised.”

A. J. P. Taylor

“No

bolder stroke has ever been conceived in all military

history than that by which the German Supreme Command in

1914 almost succeeded in capturing the whole of France

in one lightning-like offensive. And no military mystery

has ever aroused more controversy in the pages of

history than has the question of whether this bold

stroke was well- or ill-conceived as military strategy.

Was the original Schlieffen Plan, as authored by Graf

Alfred von Schlieffen who had died only a year before

the war broke out, robbed of its success because those

who tried to follow it -- and those of these,

particularly von Molke -- lacked the courage to take the

full risk, thereby bungling? Or was it the Plan itself

which, considering the time and place, was at fault?”

|

|

|

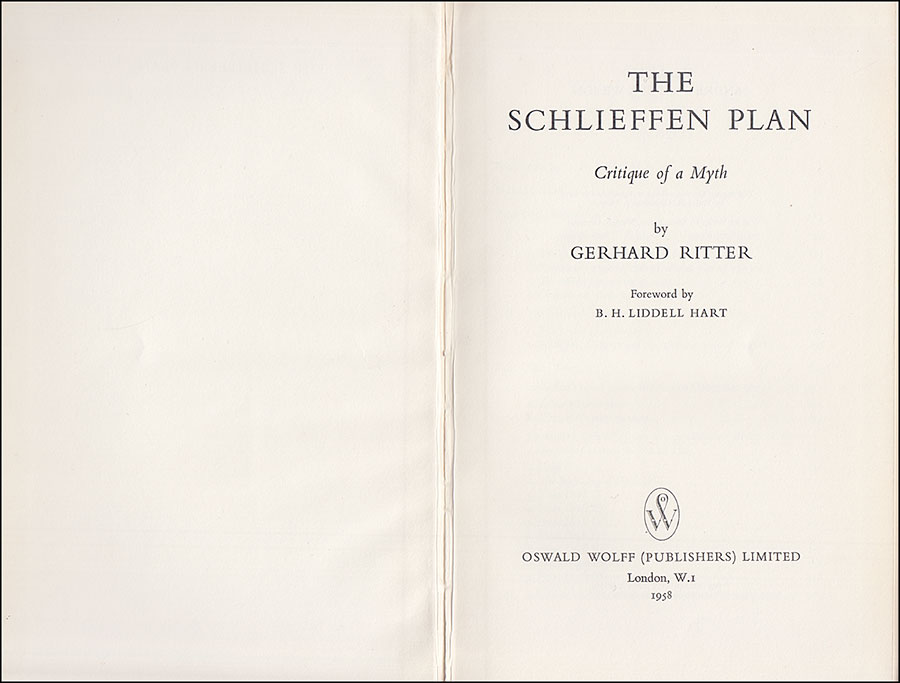

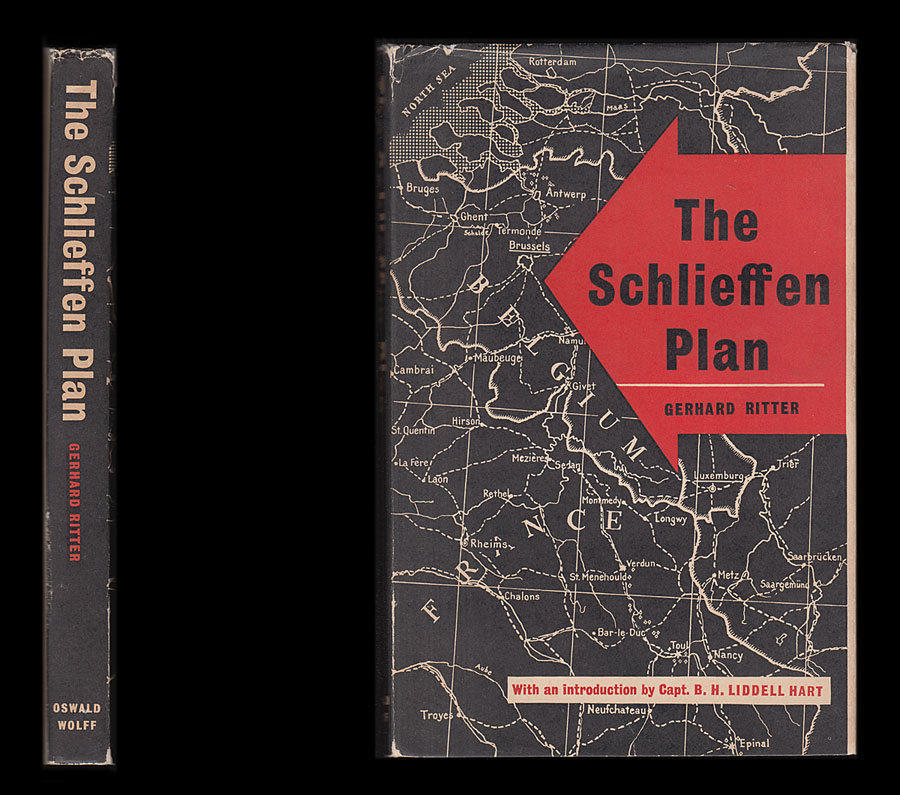

Front cover and spine

Further images of this book are

shown below

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher and place of

publication |

|

Dimensions in inches (to

the nearest quarter-inch) |

|

London: Oswald Wolff |

|

5½ inches wide x 8½ inches tall |

| |

|

|

|

Edition |

|

Length |

|

1958 [First English Edition] |

|

195 pages |

| |

|

|

|

Condition of covers |

|

Internal condition |

|

Original blue cloth blocked in gilt on the

spine. The covers are

rubbed and discoloured. In particular (and I have only seen this on a few

occasions), the dust-jacket outline has been imprinted on the front cover

resulting in a very definite negative-type image which can be seen be seen

in the image below. The shadow on the rear cover from the dust-jacket is far

less obvious. There is also a very distinct thin line of colour loss along

the top and bottom edges, and the covers have bowed outwards. The

spine ends and corners are bumped and there is a slight forward spine lean. |

|

There is the armorial bookplate of M.

Brocklebank (motto: "God send Grace") on the front pastedown, together with

a small "Foyles Bookshop" sticker (please see the penultimate image below).

There is offsetting to the end-papers (a band of discolouration) from the

dust-jacket flaps. The text is very clean throughout; however, the top

corners of pages 131 to 134 are heavily creased (shown below). |

| |

|

|

|

Dust-jacket present? |

|

Other

comments |

|

Yes: however, the dust-jacket is torn, scuffed and creased around the edges.

There is a small tear in the centre of the bottom edge of the front panel,

and further tears along the top front flap fold, and, particularly, at the

head of the spine panel, where there is some very minor loss. The rear panel

is very discoloured and grubby. The dust-jacket is not price-clipped but the

interior has tanned significant with age. |

|

There is an armorial bookplate on the

front pastedown, otherwise the interior condition is very clean indeed

(noting also a few creased corners). The dust-jacket is discoloured and

chipped with some small tears. The covers have bowed out and the dust-jacket

outline has been imprinted on the front cover. |

| |

|

|

|

Illustrations,

maps, etc |

|

Contents |

|

NONE : No illustrations are called

for; there are six maps at the end. |

|

Please see below for details |

| |

|

|

|

Post & shipping

information |

|

Payment options |

|

The packed weight is approximately

600 grams.

Full shipping/postage information is

provided in a panel

at the end of this listing.

|

|

Payment options

:

-

UK buyers: cheque (in

GBP), debit card, credit card (Visa, MasterCard but

not Amex), PayPal

-

International buyers: credit card

(Visa, MasterCard but not Amex), PayPal

Full payment information is provided in a

panel at the end of this listing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Schlieffen Plan

Contents

Foreword by B. H. Liddell Hart

Introduction

Part One: Exposition

I. The development of Schlieffen's operational ideas

1. The shift of emphasis from East to

West

2. Preliminary stages of the

operational plan of 1905

3. The military testament of 1905

4. Operational memoranda after

retirement

II. The political implications of the

Schlieffen Plan

1. The breach of neutrality

2. Schlieffen, Holstein and the Morocco crisis of 1905-6

Part Two: Texts

I. Schlieffen's great memorandum of December 1905

A. Editor's Introduction

B. Text of the memorandum

Appendix: Extracts from the preliminary drafts of the December memorandum of

1905

1. Draft I

2. The beginning of Draft TV

3. From Draft II

4. From Draft III

5. From Draft W

6. From Draft IV

7. From Draft VI

8. From Fragment VII

9. From Draft VI

II. Schlieffen's additional memorandum of February 1906

III. General observations on the Schlieffen

Plan by H. von

Moltke

IV. Schlieffen's memorandum of December 28th, 1912 Appendix to the

memorandum of 1912

V. Notes by Major von Hahnke on Graf Schlieffen's memorandum of December 28th, 1912

VI. Schlieffen's operational plan for "Red" (France) of 1911

Index

|

|

|

|

|

The Schlieffen Plan

Introduction

THE deployment and operational plans

of the Chief of the General Staff, Graf Schlieffen, here published

for the first time in their entirety, are without doubt among the

most controversial documents of recent military history. Probably no

general staff study ever aroused such widespread interest and

excitement among the general public. It has let loose a whole flood

of military and political literature. Yet these plans have so far

been known to the public only in the form of a summary of their

contents by military writers—and these refer mostly only to the

memorandum of 1905. Of the complete text, all that has so far

appeared is a few sentences. Relatively the fullest reproduction may

be found in the official publication of the Reichs-archiv. Yet this

too is incomplete, partly for political reasons. In the midst of the

quarrel over the famous "war guilt question" German officials,

particularly in the Foreign Ministry, had grave hesitations about

publishing those passages of Schlieffen's memoranda which discuss

marching not just through Belgium but through Holland as well. For

these would have presented Germany's accusers (and slanderers) with

new propaganda material. Such fears lost their foundation with the

appearance in 1922 of the memoirs of the younger Moltke, which

included a memorandum of 1915 setting out his different point of

view on this question as a kind of apologia. But the qualms of the

Foreign Ministry persisted, since no one wanted to get involved in

ticklish explanations to the Dutch about Schlieffen's views on Dutch

policy. Later on, publication was planned within the framework of

Schlieffen's Dienstschriften, which were issued by the reconstituted

General Staff from 1937 onwards. But the series was never completed

because of the outbreak of the war.

The manuscripts on which the second part of this book is based are

among the Schlieffen papers originally handed over to the Army

archives (subsequently incorporated in the Reichsarchiv in Potsdam)

by Schlieffen's son-in-law, Major von Hahnke. Along with other

military documents, they fell into the hands of the American Army,

which turned them over to the National Archives in Washington. It

was there that I found them, after my attention had been drawn to

the matter by Professor Fritz Epstein, during a visit undertaken for

quite separate purposes in the spring of 1953. Not only was I

granted free access to the manuscripts, but I asked for, and

received, photostat copies of the papers which most interested me.

In the meantime the entire Schlieffen papers have been returned to

Germany. The official manuscripts are in the hands of the Federal

Defence Ministry, to whom I am greatly obliged for further access to

the documents and permission to publish them, as well as for help in

making sketch-maps and further photostats.

The significance of the Schlieffen Plan extends far beyond purely

military history. Its political consequences made it nothing less

than fateful for Germany. In latter times it has been looked on as a

design for a preventive war against France, made in collusion with

the leading brain of the Foreign Ministry, Baron Fritz von Holstein,

towards the end of 1905. In consequence, the Schlieffen Plan has

become the centre of every discussion about the role of the German

general staff before 1914, and about the whole question of German

"militarism." Such are the special circumstances which may justify

its present publication, not by an officer schooled in the methods

of the General Staff, but by a political historian who has long made

this kind of problem the object of special study. The author feels

that this publication is indispensable as a preliminary study and

supplement to the second volume of his book Staatkunst und

Kriegshandwerk, Das Problem des "Militarismus" in Deutschland, of

which the first volume appeared in 1954. Of course, he does not feel

called upon to appear as an expert in purely military matters—to

appreciate, for example, Graf Schlieffen's strategic achievements as

such. He is not tempted by the role either of "civilian strategist"

or "historical umpire" in the quarrel of the military experts. But

what must be accomplished within the framework of such a

publication, and what may be achieved by a civilian, is threefold:

An analysis of the historical features of Schlieffen's strategic

plans compared with those of his predecessor and his successor.

A portrait of Schlieffen as a man and as the holder of his office.

An appreciation of the political significance of his plans—in their

intent as well as in their consequences.

Gerhard Ritter

Freiburg im Breisgau, March 1956.

Foreword

by B. H. Liddell Hart

FOR two generations the Schlieffen

Plan has been a magic phrase, embodying one of the chief mysteries

and "might have beens" of modern times. The mystery is cleared up

and the great "If" analysed in Gerhard Ritter's book—a striking

contribution to twentieth-century history.

In the years following World War I German soldiers spoke of Graf

Schlieffen with wistful awe as their supreme strategist, and

ascribed the failure of the 1914 invasion of France to the way in

which his masterly plan, worked out when Chief of the Great General

Staff from 1891 to 1905, had been whittled down and mishandled by

his successor, the second Moltke.

The repulse of that opening offensive was followed by years of

trench-deadlock, and eventually by Germany's collapse in 1918. By

the time she and her allies collapsed, her surviving European

opponents were themselves near to exhaustion, Russia had turned

Communist and gone out of the war, while the United States had

become the world's leading Power. So the consequences were immense

and far-reaching.

It was very natural, in retrospect, that German soldiers and war

historians should have placed so much weight on the second Moltke's

departure from the Schlieffen Plan as the prime cause of their

military calamities. That view also gained general acceptance in

military and historical circles abroad, as it was so obvious that

the operational plan pursued by the German Supreme Command of 1914

had gone wrong, and that the repulse of the German armies in the

Battle of the Marne had been a turning-point in the war. Moreover

the evidence that became known, from German staff disclosures,

tended to confirm the conclusion that Schlieffen's plan had been

much more promising and that his. successor had violated

Schlieffen's principal prescriptions.

The course of the campaign was exhaustively examined during the

postwar years, and there was voluminous discussion of the fateful

changes which took place in the German plan. But the examination and

discussion were conducted on an inadequate basis of knowledge about

the Schlieffen Plan itself. Detailed information about its content

was too sparse to be satisfying. Only broad outlines and fragmentary

passages were published. That state of insufficiency has continued

until the publication of Gerhard Fitter's book. He unearthed

Schlieffen's papers during a visit to the United States in 1953.

After lying for many years in the German archives at Potsdam, where

they had been deposited by Schlieffen's son-in-law, they had been

carried away to the American archives in Washington after World War

II, along with a mass of other military documents.

It was fortunate that the papers should have come into the hands of

Gerhard Ratter—an historian of high quality, whose discernment is

matched by his trustworthiness, and a gifted writer. He presents the

full text of Schlieffen's military testament, and the relevant parts

of other memoranda which shed light on the evolution of the Plan.

They are preceded by Professor Ritter's masterly exposition of their

content and significance, while his accompanying notes add to the

illuminating effect.

The whole forms a book of outstanding historical importance. But it

is also extraordinarily interesting to read for a book of its kind.

At first glance it may look too scholarly in form to be of wide

appeal. But that impression soon changes as one gets deeper in the

book. It might well be described as an "historical detective

story"—and is fascinating when read in that way.

Going on from clue to clue, it becomes evident that the secret of

the Schlieffen Plan, and the basis of Schlieffen's formula for quick

victory amounted to little more than a gambler's belief in the

virtuosity of sheer audacity. Its magic is a myth. As a strategic

concept it proved a "snare and delusion" for the executants, with

fatal consequences that were on balance inherently probable from the

outset.

The basic problem which the Plan had to meet was that of two-front

war, in which Germany and her Austrian ally faced Russia on the East

and France on the West—a combination whose forces were numerically

superior although separated from one another. Schlieffen sought to

solve the problem in a different way from that contemplated by his

predecessors, the elder Moltke and Waldersee. His way, in his view,

would be quicker in execution and more complete in effect.

The elder Moltke, despite the triumphant result of the offensive

against France which he had directed in 1870, doubted whether it

could be repeated against the reorganised and strengthened French

Army. His plan was to stay on the defensive against France, nullify

Russia's threat by a sharp stroke at her advanced forces, and then

turn westward to counter-attack the French advance. It was

essentially a defensive-offensive strategy. His aim was to cripple

both opponents, and bring about a favourable peace, rather than to

pursue the dream of total victory. Moltke's immediate successor,

Waldersee, showed more bias in favour of offensive action and

aggressive policy. But he did not change Moltke's decision to stay

on the defensive in the West, and when he urged the case for a

preventive war against Russia his offensive impulse was curbed by

Bismarck.

But Schlieffen, in his very first memorandum after taking office in

1891, questioned the assumption that the French fortifications were

such a great obstacle as "to rule out an offensive" in the West,

emphasising that "they could be by-passed through Belgium." It was

an early indication of a tendency to view strategic problems in a

purely military way, disregarding political factors and the

complications likely to arise from a violation of neutral countries.

In the next year his mind began to turn against the existing plan of

taking the offensive in the East, along with the Austrian Army,

since on his calculation it would be very difficult to gain a

decisive victory there, or prevent the Russian Army retiring out of

reach. For him it did not suffice to lame the opponents— they must

be destroyed. His conception of war was dominated by the theoretical

absolutes of Clausewitzian doctrine. So when he came to the

conclusion that such absolute victory was unattainable in the East,

he came back to the idea of seeking it in the West.

Initially, he considered the problems of a direct thrust into

France, but soon concluded that success was impossible in that way.

While hoping that the French might take the offensive, giving him

the chance to trap them and deliver a counter-thrust into France, he

felt that such self-exposure on their part was too uncertain a hope

to provide the quick victory he desired. By 1897 he became convinced

that he must take the offensive from the outset, and as it could

only be successful by outflanking the French fortress system it

meant that the German Command "must not shrink from violating the

neutrality of Belgium as well as of Luxembourg." For the turning

manoeuvre must be wide enough- for the deployment of ample forces,

and too wide for the enemy to block it by a short extension of his

front.

The plan was developed by degrees during the years that followed. At

first his idea was only to march through the southern tip of

Belgium, aiming to turn the French flank near Sedan. But by 1905 he

planned to go through the centre of Belgium in a great wheeling

movement, with his right wing-tip passing into France near Lille.

To avoid it being checked by the Belgian fortresses of Namur and

Liege in the deep-cut stretch of the Meuse valley, he decided that

it must sweep through the southern part of Holland—which meant

violating another neutral country. To avoid being blocked by Paris

or exposing his right flank to a counter-stroke from Paris, he

decided to extend his wheel wider still and sweep round west of

Paris. That, he felt, was also the only way to ensure that the

French armies were cut off from the possibility of escaping

southward. Such a large wheel required correspondingly large forces

for its execution, taking account of the need to leave adequate

detachment on guard over the fortresses by-passed, while keeping up

the strength of the long-stretched marching line. Thus he was led to

shift the weight of his forces so heavily rightwards that nearly

seven-eighths of the total was dedicated to "the great wheel," and

barely one-eighth left to meet a possible French offensive across

his own frontier.

It was a conception of Napoleonic boldness, and there were

encouraging precedents in Napoleon's early career for counting on

the decisive effect of arriving in the enemy's rear with the bulk of

one's forces. If the manoeuvre went well it held much greater

promise of quick and complete victory than any other course could

offer, and the hazards of leaving only a small proportion to face a

French frontal attack were not as big as they appeared. Moreover if

the German defensive wing was pushed back, without breaking, that

would tend to increase the effect of the offensive wing. It would

operate like a revolving door—the harder the French pushed on one

side the more sharply would the other side swing round and strike

their back.

But Schlieffen failed to take due account of a great difference

between the conditions of Napoleonic times and his own—the advent of

the railway. While his troops would have to march on their own feet

round the circumference of the circle, the French would be able to

switch troops by rail across the chord of the circle. That was all

the worse handicap because his prospects mainly depended on the time

factor. The handicap was further increased because his troops would

be likely to find their advance hampered by a succession of

demolished bridges, while their food and ammunition supply would be

restricted until they could rebuild the rail tracks and rail bridges

through Belgium and Northern France.

The great scythe-sweep which Schlieffen planned was a manoeuvre that

had been possible in Napoleonic times. It would again become

possible in the next generation—when air-power could paralyse the

defending side's attempt to switch its forces, while the development

of mechanised forces greatly accelerated the speed of encircling

moves, and extended their range. But Schlieffen's plan hada very

poor chance of decisive success at the time it was conceived.

The less he could count on an advantage in speed the more would

depend on having a decisive superiority of strength, at any rate in

the crucial area. His recognition of this need was shown in the way

he whittled down the proportion of the German strength to be left on

the Eastern Front and on the defensive wing in the West. His main

device to produce an actual increase of attacking strength was to

create a number of additional army corps from reservists of various

grades, and incorporate them in the striking force for subsidiary

tasks. But even then the Germans' total forces in the West would

have only a slight margin of numbers over the French, and that

margin would disappear with the addition of the Belgian and British

armies (small as these were) to the forces with which the Germans

would have to deal—as a consequence of going through Belgium.

It is evident from Schlieffen's papers that by the time he finally

framed his Plan he had come to feel very doubtful whether Germany

had or could attain the superiority of force needed for a reasonable

assurance of success in such an offensive venture. But he seems to

have taken the technician's view that his duty was fulfilled if he

did the utmost with the means available, and "made the best of a bad

job" in compliance with the customs and rules of his profession. He

did not consider that he had the higher responsibility of warning

the Emperor and the Chancellor that the chances of success were

small compared with the risks, and that German policy ought to be

adjusted to that grave reality.

Still less was he conscious of a responsibility to humanity. When,

in further reflection after leaving office, he came to realise how

dubious were the chances of success for his offensive Plan, his only

fresh suggestions for improving its chances were to make a wider

sweep through Holland and hasten the advance through Belgium by

threat of a terror-bombardment of the town populations.

During these later years Russia's recovery from the effects of her

war with Japan, and reorganisation of her forces, made the overall

situation more adverse to the prospects of his Plan. But he showed

no realisation of the changed situation, and in his last memorandum

at the end of 1912—a week before his death, just short of his

eightieth birthday—he virtually ignored Russia's power of

interference and the likelihood that it might compel a reinforcement

of the Germans' slender strength on the Eastern Front at the expense

of their concentration on the Western Front. He had become obsessed

with the dream of a quick knock-out blow against France, and his

dying words are reported to have been: "It must come to a fight.

Only make the right wing strong."

His successor, the second Moltke, was not happy about the Plan that

came to him as a legacy, and found little help in the advice which

Schlieffen offered after his retirement. It is not surprising to

learn from a note by Schlieffen's son-in-law that by 1911 neither

Moltke, Ludendorff (the head of the Operations directorate,

1908-13), nor any other of the chief members of the General Staff

thought it worth while to consult "the master" about the problem.

Moltke, with more political sense and scruple than his predecessor,

decided to avoid violating Holland's neutrality in addition to

Belgium's, and found an alternative solution in a swift capture of

the Liege bottleneck by a surprise coup. This was achieved in 1914

under the personal direction of Ludendorff, so the German offensive

enjoyed a successful start. It was helped even more by the recently

recast French operational plan, which played into the Germans' hands

far better than Schlieffen could have expected.

This was due to a new school of thought in France, which was

intoxicated with the offensive spirit. In 1912 the leaders of this

school ousted the then Chief of the General Staff, Michel, who had

expected the Germans to come through Belgium and planned a defence

against the move. The new school ignored the danger in their

eagerness to launch an offensive of their own across the German

frontier. This ran headlong into a trap, and the French Army was

caught badly off balance when the Germans swept round its left wing.

Nevertheless the French were able to switch reinforcements thither

by rail, while the German advance dwindled in strength and lost

cohesion as it pressed deeper into France. It suffered badly from

shortage of supplies, caused by the demolition of the railways, and

was on the verge of breakdown by the time the French launched a

counter-stroke, starting from the Paris area—which sufficed to

dislocate the German right wing and cause a general retreat.

After the event, Moltke was blamed for the way he exposed his flank

to such a riposte by wheeling inwards before Paris was passed,

contrary to the Schlieffen Plan. But it now becomes clear from

Schlieffen's papers that he himself had come to recognise that his

forces were insufficient for such an extremely wide stretch, and

that he contemplated wheeling inwards north of Paris as Moltke did.

Another charge brought against Moltke is that he spoilt the Plan by

allotting more of the newly raised corps to the left wing than to

the right. But here again we find that Schlieffen had also come to

see the need of strengthening the left wing. In any case the course

of events amply proved that the right wing could not have been made

stronger than it was, nor its strength maintained as the advance

continued—because of the rail demolitions. It is useless to multiply

numbers if they cannot be fed and munitioned.

In the light of Schlieffen's papers, and of the lessons of World War

I, it is hard to find reason for the way he has so long been

regarded as a master mind, and one who would have been victorious if

he had lived to conduct his own Plan.

Schlieffen very clearly grasped the value of turning the opponent's

flank—but that was no new discovery. He further saw that the effect

depended on successive by-passing moves, progressively pressed

deeper towards the opponent's rear. But that had been appreciated

and excellently brought out as far back as 500 B.C., in Sun Tzu's

teaching on "The Art of War." Schlieffen's operational expertness in

war games has been acclaimed by many of his subordinates. But it was

never tested in war, and does not suffice as proof of his mastery of

strategic theory. This can now be examined in the light of his

papers. On their evidence, his grasp of strategy was broad but

shallow, more mathematical than psychological. Although he was a

strong believer in the virtues of indirect approach, he seems to

have regarded it principally as a physical-geographical

matter—rather than as a compound way of applying pressure upon the

mind and spirit of the opposing commander and troops. There is

little in Schlieffen's papers that suggests understanding of the

finer points of strategy, and the subtler ways in which it can

decisively change the balance.

Nor do his papers show any clear realisation of the extent to which

strategic success depends on what is tactically possible. The papers

provide little evidence of concern with the vital change in tactical

conditions that was being produced by the tremendous development in

the fire-power of weapons, and their multiplication. His discussion

of the strategic problem of invading France, and achieving a quick

victory there, recognises that the fortresses are likely to be

serious obstacles to the German advance, and emphasises the need of

heavy field artillery to overcome them. But it does not take account

of other and newer tactical hindrances. There is no mention in

Schlieffen's military testament, handed to his successor in 1906, of

the quick-firing field artillery developed by the French—the famous

"75s"—nor of machine-guns. Even in his final thoughts on the war

problem set forth in his memorandum of December 1912, there are only

two incidental mentions of the machine-gun—which, when war came in

1914, proved the greatest obstacle to any advance, paralysing

operations once the front had been extended to the coast and no open

strategic flank could be found. Nowhere does Schlieffen consider

barbed-wire entanglements, which became such an important supplement

to the machine-gun in producing the trench-deadlock. Moreover he did

not take adequate account of the effect of demolitions, particularly

of rail bridges, as a brake on the supplies needed to maintain his

strategic advance. In one of the early drafts of his 1906 memorandum

for his successor he devoted a lengthy paragraph to the matter, but

dropped this out in the final draft, and skated over the problem.

That is symptomatic of a tendency to discount difficulties in

becoming more ardent for a long cherished plan.

Worse still—not only for Germany but for the world—was his lack of

understanding of the wider political, economic, and moral factors

which are inseparable from the military factors on the higher plane

of strategy that is aptiy termed "grand strategy." His failure to

understand these non-military factors and their influence is ably

examined by Gerhard Ritter, and forms one of the most interesting

parts of this book.

In previous generations, state policy had governed the use of

military means—as it must, if policy is to fulfil its purpose, and

make sense. But that proper relationship began to be altered, and in

effect reversed, when Bismarck's removal from the Chancellorship in

1890 was closely followed by Schlieffen's appointment to be head of

the General Staff. As Ritter has pointed out, the Schlieffen Plan

forms the prime example of "state-reasoning" being distorted by a

purely military way of thinking. The consequences were disastrous.

|

|

|

|

|

The Schlieffen Plan

From the dust-jacket flap:

Graf Schlieffen—the architect of the

German campaign against France through Belgium in 1914—has always

been a figure of controversy. Was he, as many military writers have

represented him, both in Britain and Germany, the great strategist

whose bold plan was robbed of success by the fumbling of those who

inherited it? And was he, as many historians have believed, the

archetype of "warmongering" Prussian generals, who sought to

instigate the conflict which resulted in the slaughter of millions

of men on both sides?

For forty years the controversy has been waged without the central

piece of evidence: the full text of the "Schlieffen Plan" itself.

In 1953 the text was unearthed by the distinguished German

historian, Professor Gerhard Ritter. Now, after the work of editing

and comparing the many different drafts, it has been presented to

the world for the first time.

The book forms a work of outstanding historical importance. In

dealing with the central points of argument, Professor Ritter

reopens the vital question whether Schlieffen intended his plan for

an attack on France at the time of the Morocco crisis of 1905-6. On

the military side, he traces the argument which led Schlieffen to

conclude that the great "hook" round Paris required the invasion

"not only of Belgium but also of the Netherlands".

Finally he throws a sidelight—new for most English readers—on the

Field-Marshal's remarkable private life.

From the rear panel:

THE AUTHOR

Gerhard Ritter, who since the end of the war has made an

international reputation for himself as one of Germany's most

distinguished historians, was born in 1888. He studied at Munich,

Leipzig, Heidelberg and Berlin, and was on active service during the

First World War, from 1915 to 1918.

In 1924 he became a professor at Hamburg, and a year later he moved

to Freiburg University, where he has taught ever since. During the

Nazi Period he came into open conflict with the regime, and was

imprisoned from 1944 until 1945 for his part in the abortive revolt

of July 20th, 1944.

In addition to his work as editor of a number of learned

publications (among them the important bibliography German

Historiography in the Second World War which appeared in 1951),

Ritter has written several historical works of outstanding

importance since the war. Following his book Europe and the German

Question, he became a member, in 1950, of the Munich Institute for

Research into the National-Socialist Period. He was one of the

editors of the volume of Hitler's Table-Talk, published by. the

Institute, which caused an international sensation and a great deal

of controversy inside Germany.

Among his more recent works are The Reorganisation of Europe in the

16th Century; The Corrupting Influence of Power; The Art of

Statesmanship and the Craft of War; and a book on his friend Carl

Goerdeler, the titular head of the revolt of the 20th of July, Carl

Goerdeler and the German Resistance Movement.

Professor Ritter attaches special importance to the present work,

since he regards the Schlieffen Plan as the beginning of Germany's,

and Europe's, misfortune. In the words of the distinguished English

historian, Mr. A. J. P. Taylor, the book is "a source of fundamental

importance for understanding the causes of the First World War. All

existing accounts must now be revised."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please note: to avoid opening the book out, with the

risk of damaging the spine, some of the pages were slightly raised on the

inner edge when being scanned, which has resulted in some blurring to the

text and a

shadow on the inside edge of the final images. Colour reproduction is shown

as accurately as possible but please be aware that some colours

are difficult to scan and may result in a slight variation from

the colour shown below to the actual colour.

In line with eBay guidelines on picture sizes, some of the illustrations may

be shown enlarged for greater detail and clarity.

The

dust-jacket outline has been imprinted on the front cover

resulting in a very definite negative-type image which can

be seen be seen in the image below.

There is the armorial bookplate of M.

Brocklebank (motto: "God send Grace") on the front pastedown,

together with a small "Foyles Bookshop" sticker :

The dust-jacket is not price-clipped but the

interior has tanned significant with age.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U.K. buyers:

|

To estimate the

“packed

weight” each book is first weighed and then

an additional amount of 150 grams is added to allow for the packaging

material (all

books are securely wrapped and posted in a cardboard book-mailer).

The weight of the book and packaging is then rounded up to the

nearest hundred grams to arrive at the postage figure. I make no charge for packaging materials and

do not seek to profit

from postage and packaging. Postage can be combined for multiple purchases. |

Packed weight of this item : approximately 600 grams

|

Postage and payment options to U.K. addresses: |

-

Details of the various postage options can be obtained by selecting

the “Postage and payments” option at the head of this

listing (above).

-

Payment can be made by: debit card, credit

card (Visa or MasterCard, but not Amex), cheque (payable to

"G Miller", please), or PayPal.

-

Please contact me with name,

address and payment details within seven days of the end of the

listing;

otherwise I reserve the right to cancel the sale and re-list the item.

-

Finally, this should be an

enjoyable experience for both the buyer and seller and I hope

you will find me very easy to deal with. If you have a question

or query about any aspect (postage, payment, delivery options

and so on), please do not hesitate to contact me.

|

|

|

|

|

International

buyers:

|

To estimate the

“packed

weight” each book is first weighed and then

an additional amount of 150 grams is added to allow for the packaging

material (all

books are securely wrapped and posted in a cardboard book-mailer).

The weight of the book and packaging is then rounded up to the

nearest hundred grams to arrive at the shipping figure.

I make no charge for packaging materials and do not

seek to profit

from shipping and handling.

Shipping can

usually be combined for multiple purchases

(to a

maximum

of 5 kilograms in any one parcel with the exception of Canada, where

the limit is 2 kilograms). |

Packed weight of this item : approximately 600 grams

| International Shipping options: |

Details of the postage options

to various countries (via Air Mail) can be obtained by selecting

the “Postage and payments” option at the head of this listing

(above) and then selecting your country of residence from the drop-down

list. For destinations not shown or other requirements, please contact me before buying.

Due to the

extreme length of time now taken for deliveries, surface mail is no longer

a viable option and I am unable to offer it even in the case of heavy items.

I am afraid that I cannot make any exceptions to this rule.

|

Payment options for international buyers: |

-

Payment can be made by: credit card (Visa

or MasterCard, but not Amex) or PayPal. I can also accept a cheque in GBP [British

Pounds Sterling] but only if drawn on a major British bank.

-

Regretfully, due to extremely

high conversion charges, I CANNOT accept foreign currency : all payments

must be made in GBP [British Pounds Sterling]. This can be accomplished easily

using a credit card, which I am able to accept as I have a separate,

well-established business, or PayPal.

-

Please contact me with your name and address and payment details within

seven days of the end of the listing; otherwise I reserve the right to

cancel the sale and re-list the item.

-

Finally, this should be an enjoyable experience for

both the buyer and seller and I hope you will find me very easy to deal

with. If you have a question or query about any aspect (shipping,

payment, delivery options and so on), please do not hesitate to contact

me.

Prospective international

buyers should ensure that they are able to provide credit card details or

pay by PayPal within 7 days from the end of the listing (or inform me that

they will be sending a cheque in GBP drawn on a major British bank). Thank you.

|

|

|

|

|

(please note that the

book shown is for illustrative purposes only and forms no part of this

listing)

Book dimensions are given in

inches, to the nearest quarter-inch, in the format width x height.

Please

note that, to differentiate them from soft-covers and paperbacks, modern

hardbacks are still invariably described as being ‘cloth’ when they are, in

fact, predominantly bound in paper-covered boards pressed to resemble cloth. |

|

|

|

|

Fine Books for Fine Minds |

I value your custom (and my

feedback rating) but I am also a bibliophile : I want books to arrive in the

same condition in which they were dispatched. For this reason, all books are

securely wrapped in tissue and a protective covering and are

then posted in a cardboard container. If any book is

significantly not as

described, I will offer a full refund. Unless the

size of the book precludes this, hardback books with a dust-jacket are

usually provided with a clear film protective cover, while

hardback books without a dust-jacket are usually provided with a rigid clear cover.

The Royal Mail, in my experience, offers an excellent service, but things

can occasionally go wrong.

However, I believe it is my responsibility to guarantee delivery.

If any book is lost or damaged in transit, I will offer a full refund.

Thank you for looking.

|

|

|

|

|

Please also

view my other listings for

a range of interesting books

and feel free to contact me if you require any additional information

Design and content © Geoffrey Miller |

|

|

|

|

|