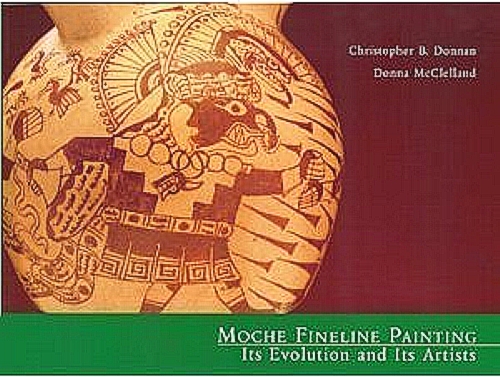

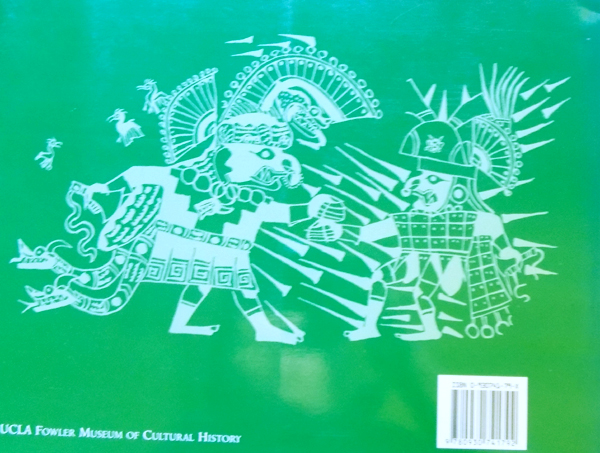

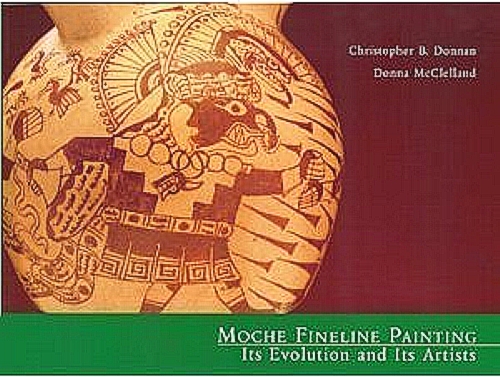

"Moche Fineline Painting: Its Evolution and Its Artists" by Christopher B. Donnan.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

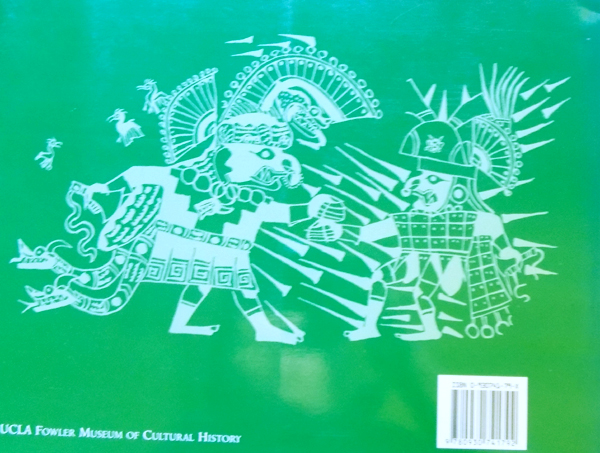

DESCRIPTION: Pictorial hardcover w/dustjacket. Publisher: University of California Los Angeles (1999). Pages: 320. Size: 12¼ x 9¼ x 1¼ inches; 4½ pounds.

Summary: The Moche culture, which flourished on the north coast of Peru between 100 and 800 B.C., has been known to art historians and archaeologists for over a century. Only recently, however, with the discovery of the fabulous Royal Tombs of Sipan, have the Moche become as well known to the public as the Inca, who appeared several centuries later. This book traces the fineline painting tradition from the beginning to the end of the Moche culture. Although the Moche had no writing system, they left a vivid artistic record of their beliefs and activities in beautifully modeled and painted ceramics. Because of their complexity and wide range of subject matter, these paintings provide a wealth of information about Moche civilization.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. HUGE, clean, lightly read but (NON-PUBLIC) LIBRARY DISCARD hardcover w/dustjacket. University of California Los Angeles (1999) 320 pages. The book belonged to the San Diego Museum of Man Scientific Library. BTW, San Diego's Museum of Man is a delightful museum if you've never been there, in San Diego's picturesque Balboa Park. There's a paste down label identifying the benefactor and the museum on the underside of the front cover (the "front end paper"). There appears to have been another label beneath which was removed, as you can see a "sticker removal scar" beneath the paste-down label described above. On the facing first free page (the heavy stock, colored but unprinted page immediately beneath and facing the underside of the front cover) there is an ink stamp identifying the museum and penciled library notations. From the outside there's a heel tag with library codes, and the top surface of the massed closed page edges has an ink-stamp (in typical library fashion) also identifying the museum. Of course that ink stamp to the top surface of the massed closed page edges (often referred to as the "page block") is not visible to the individual opened pages...just to the top surface of the massed closed page edges. There's also a small cluster of very small, faint tan-colored age speckles near the open corner of the top surface of the massed closed page edges. Again, not seen on individual opened pages. Finally the first quarter of the pages in the book are lightly bumped/crinkled (though the overlying cover corner is not). This is quite common shelfwear in such a massive book, even with a new book from a retail bookstore environment. It typically occurs when someone who is hastily and carelessly shelving books bumps the corner of the book against the unyielding edge of a book shelf or into the spine head of an adjacent book. Oftentimes the book has partly flopped open, so it's quite common to see the corners of the pages within the book bumped while the overlying covers may not show only any corresponding bump (as in this case). Sometimes with the book flopping open and then being bumped, the page corners might be crinkled absent any bump to the book's cover corners. It's purely a superficial cosmetic blemish, but we would not offer a book regardless of however slightly bumped without describing in detail the blemish, however superficial. Huge, heavy books like this are awkward to handle and so tend to show accelerated shelfwear, frequently bumped, and particularly with respect to the bottom edges and corners, as due to their size and weight they are frequently the victim of careless, lazy or clumsy re-shelving. With those exception the inside of the book is otherwise almost pristine. The pages are clean, crisp, (otherwise) unmarked, (otherwise) unmutilated, remain well-bound, and evidence only very light reading wear. The dustjacket is enclosed beneath an acetate cover which likely was installed when the book was new, as there is no evidence of any shelfwear to the dustjacket (although of course the clear acetate cover does show rubbing, scuffing, and light scratching). Beneath the dustjacket the full cloth covers are likewise clean, unsoiled, and evidence no appreciable shelfwear. Given the indications (stamps and stickers) that the San Diego Museum of Man once owned the book, the book might not possess the "sex appeal" of a "shelf trophy". Nonetheless it is clean and only lightly read. For those not concerned with whether the book will or will not enhance their social status or intellectual reputation, it's a solid copy with "lots of miles left under the hood". Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #8806b.

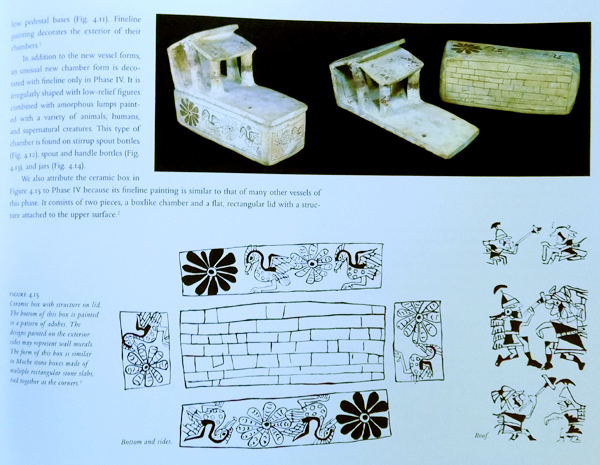

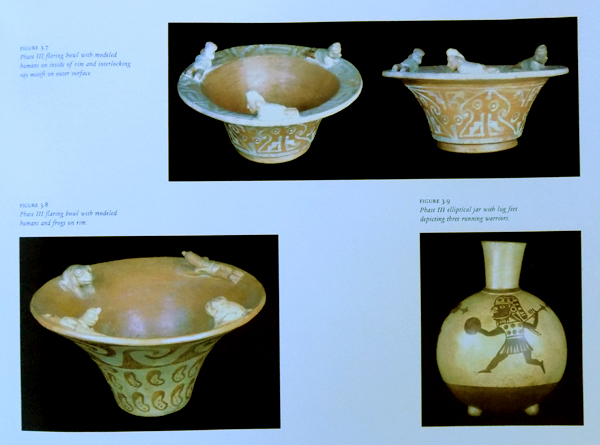

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: The Moche culture flourished on the north coast of Peru between 100 and 800 BCE. They left a vivid artistic record of their beliefs and activities in beautifully modeled and painted ceramics. This book traces the fineline painting tradition from the beginning to the end of the Moche culture

REVIEW: Christopher B. Donnan is an archaeologist. He has researched the Moche civilization of ancient Peru for more than fifty years, conducting numerous excavations of Peruvian archaeological sites. Donnan has traveled the world photographing Moche artwork for purposes of publication, recording both museum artifacts and private collections that would otherwise be unavailable to the public. He has published extensively, both academically and for the general public.

When not involved in writing or fieldwork, Donnan teaches anthropology at University of California Los Angeles as Professor Emeritus and serves as Director for the Fowler Museum. Donnan's publications include: "Ancient Burial Patterns of the Moche Valley, Peru"; "Burial Theme in Moche Iconography"; "Ceramics of Ancient Peru"; "Early Ceremonial Architecture in the Andes"; "Moche Art and Iconography"; "Moche Art of Peru: Pre-Columbian Symbolic Communication"; "Moche Fineline Painting: Its Evolution and Its Artists"; "Moche occupation of the Santa Valley, Peru"; "Moche Portraits from Ancient Peru"; "Moche Tombs at Dos Cabezas"; and "The Pacatnamu Papers".

REVIEW: Christopher B. Donnan is a professor of anthropology at UCLA where he is also director of the Moche Archive at the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. Donna McClelland has collaborated with Professor Donnan for nearly 30 years.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Preface.

Chapter One: Introduction.

Chapter Two: Phase 1-2 Building on the Past.

Chapter Three: Phase 3 Setting Standards.

Chapter Four: Phase 4 The Classical Period.

Chapter Five: Phase 5 The Terminal Phase.

Chapter Six: The Moche Artists.

Chapter Seven: Observations and Conclusions.

Appendix A: Producing Rollout Drawings by Donna McClelland.

Appendix B: The Van den Berg Collection by Edward de Bock.

Notes.

References Cited.

Sources of Illustrations.

Index.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: The Moche civilization flourished on the north coast of Peru between100 and 800 C.E. Although the Moche people had no writing system, they left behind a vivid artistic record of their beliefs and activities in beautifully modeled and painted ceramics. Like the Greek vase painters of ancient Athens, the Moche excelled at painting complex scenes - warriors and prisoners, parades and dances, boats and fishing, burial ceremonies, hunting, and a variety of other subjects involving human, animal and mythological participants.

The culmination of three decades of research and study at UCLA, the major exhibition "Moche Fineline Painting of Ancient Peru" features 50 large-scale drawings deftly reproduced from the painted originals by artist and scholar Donna McClelland. Many exquisite Moche vessels from which the drawings were made are also on view, as well as examples of three-dimensional ceramic sculpture. Together, the drawings and ceramics tell the story of a remarkable people and the evolution of their artistic style. The first of its kind, this exhibition is on view July 16 through Feb. 18, 2001,at the UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Nearly all of the drawings and ceramic vessels in the exhibition directly relate to the immediate environment in which the artists lived. Even the most fantastic supernatural creatures can be seen as composites of parts derived from objects visible in the artist's environment. The clothing, ornaments and implements in the paintings are accurate depictions of those that have been recovered from archaeological excavations. Because of the realism of the fineline paintings, the imagery has become a critical resource for reconstructing Moche civilization.

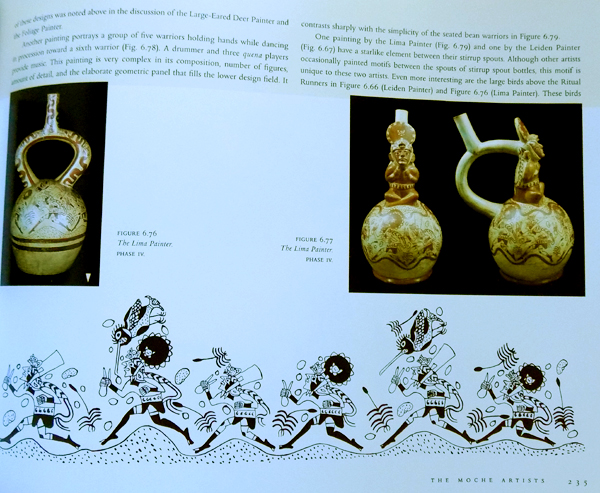

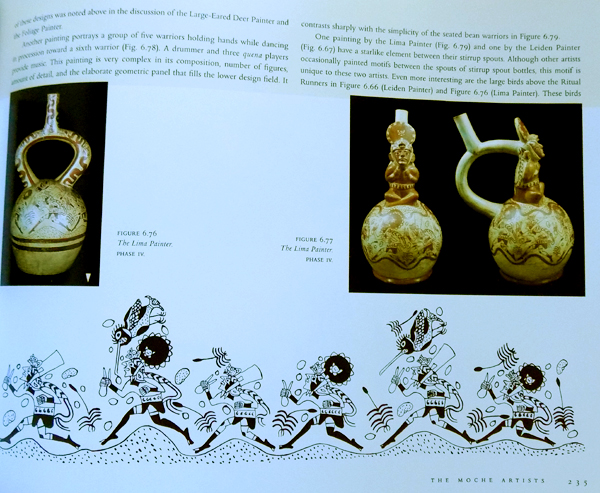

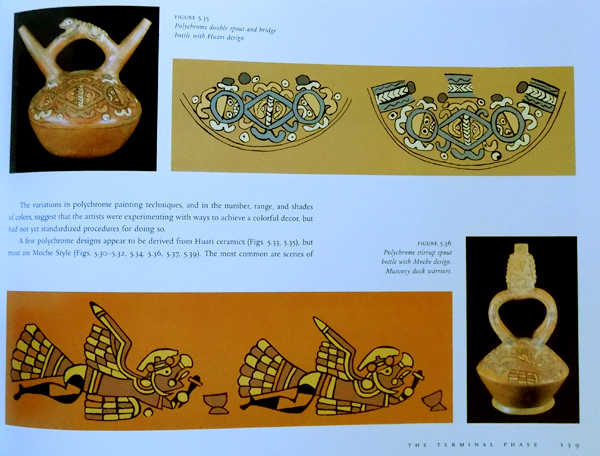

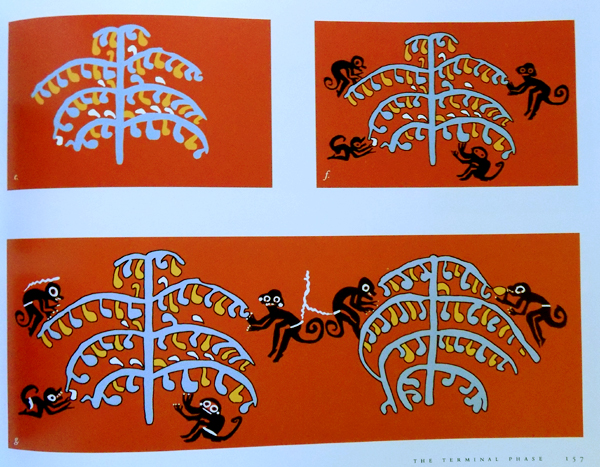

The exhibition offers a study in Moche stylistic traditions over time. In the course of 700 years, Moche artists painted increasingly complex scenes with finer and more delicate lines. The portrayal of human rather than supernatural figures increased and new activities were introduced: one vessel features a procession of pan pipers and buglers. In the final phase of fineline painting, however, the depiction of realism and human activities declined. Paintings became more abstract, and the emphasis was on supernatural creatures in marine settings.

Preceding the Inca civilization by several centuries, the Moche lived in fertile river valleys along a 350-mile stretch of desert coast. In addition to ceramics, the Moche developed sophisticated artistry in metallurgy and textile production. The sheer volume of elaborate artifacts created by the Moche indicates that there must have been a large corps of full-time, highly skilled artisans who were supported by a wealthy elite class. The ceramics and drawings on view offer testimony to a culture that once thrived with a creative genius never duplicated in pre-Columbian Peru.

Curated by Donna and Donald McClelland, this exhibition is based on research conducted by UCLA professor of anthropology Christopher B. Donnan and Donna McClelland at the UCLA Moche Archive. The largest of its kind, the Archive now houses more than 160,000 photographs of Moche objects in museums and private collections throughout the world. Donna McClelland's rollout drawings of Moche vessels number more than 730.

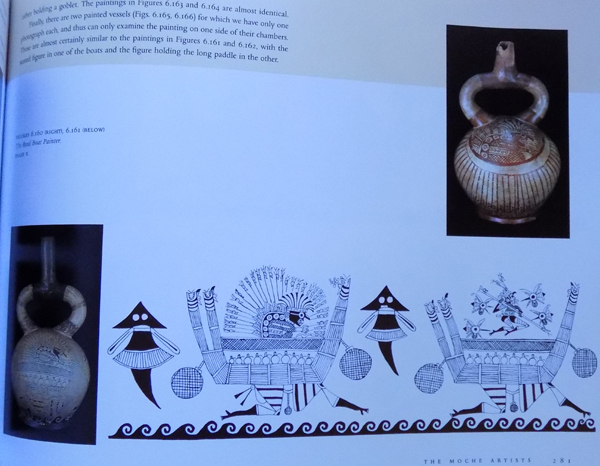

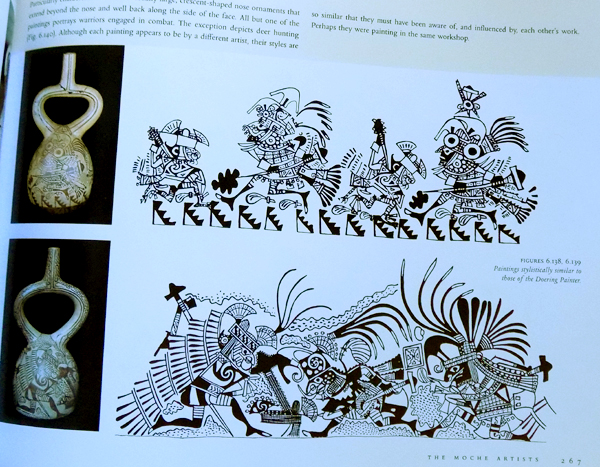

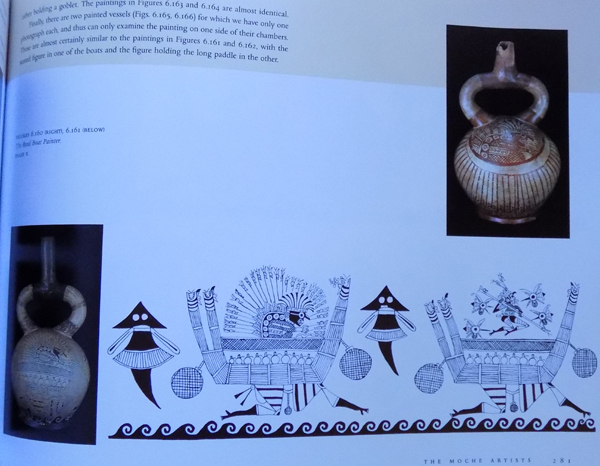

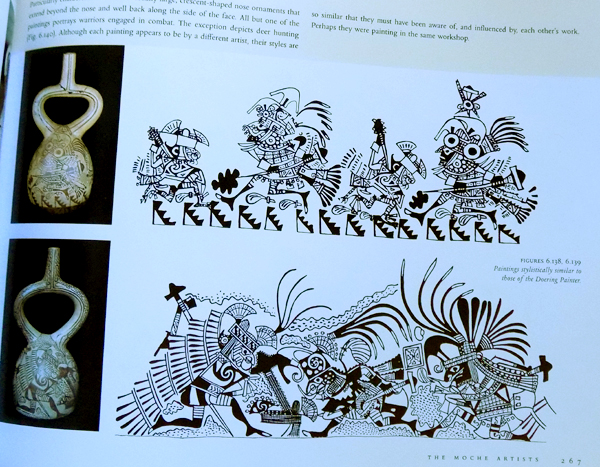

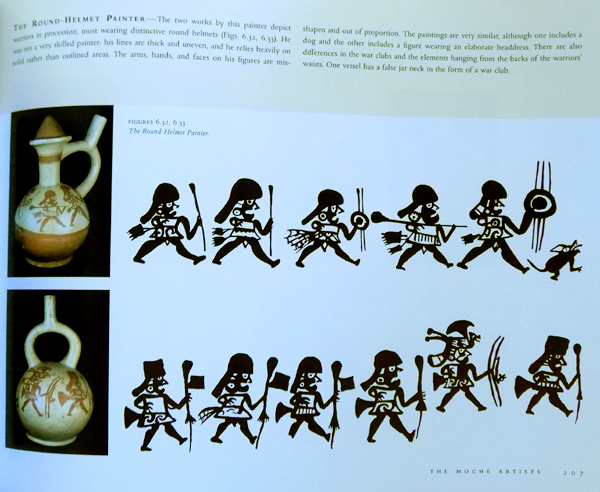

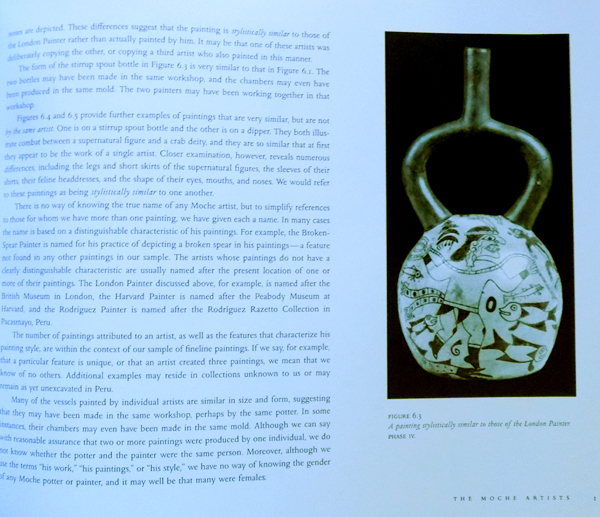

Donna McClelland's drawings make it possible to view easily in planarform the complete scenes that curve around the vessel chambers. Her drawings have been essential to understanding Moche fineline painting; one section of the exhibition examines the methodology behind the reproduction process. The drawings have enabled McClelland and Donnan to identify some 90 individual artists, each with multiple works. The distinctive styles of four anonymous artists are highlighted in the exhibition.

The exhibition, organized by the Fowler Museum, is accompanied by a 320-page publication, "Moche Fineline: Painting: Its Evolution and Its Artists," comprising 492 color and 545 black-and-white illustrations. Authored by Christopher B. Donnan and Donna McClelland and published by the Fowler, the volume contains the most comprehensive collection and definitive explanation of Moche fineline paintings ever

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: This is a sumptuously beautiful and extraordinary book by two major authorities on the civilization of the Moche Indians, who lived on the north coast of Peru for much of the first millennium AD. It depicts hundreds of monochrome drawings made on the rounded surfaces of ceramics created by Moche potters as gifts or tributes to the dead. The cartoon-like vistas and tableaux encode quirky, enigmatic, sometimes horrifying, events that are quasi historical, perhaps even biographical.

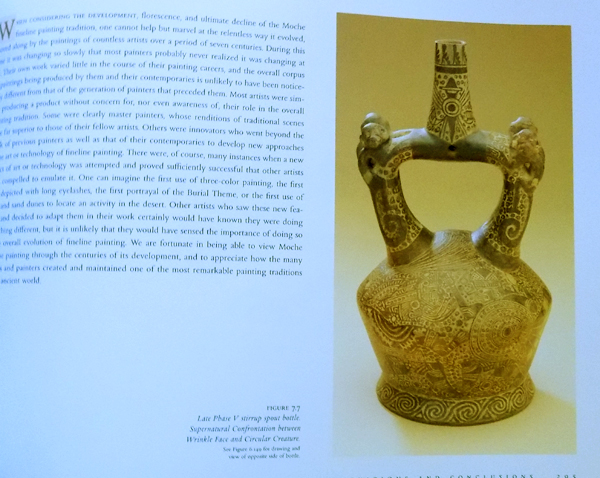

The works and images brought together in this book are widely referenced by other scholars in the field. On the same page with a careful, wonderfully detailed, rendition of the original painting in "roll out" format by Donna McClelland usually appears a full color photograph of the source ceramic. Such locality of reference allows the viewer to verify and admire how closely her reproductions match the originals which give a foretaste of the delightfully evocative figurines the Moche also sculpted.

The descriptions, explanations, and interpretations of the iconography are spare and succinct. Anthropologists once believed the paintings illustrated every aspect of ancient Moche life, but in fact the highly stylized scenes are drawn from a restricted field of religious ritual and myth. The authors apply several techniques of analysis, first used to determine the identities of the creators of ancient Greek ceramics, in order to distinguish the individual Moche artists who made the fine line paintings.

REVIEW: This is one of the most informative and beautifully published books I have seen in a long time. Chrsitopher Donnnan's writing and explanations of the Moche Fineline ceramics are clear and easily understood and Donna McClelland's illustrations are incredible. There are wonderful illustrations not only of the fineline paintings but of the techniques used to make the ceramic pots. It is obvious that a lot of work went into this publication and I would highly recommend it to anyone with an interest in the Moche.

REVIEW: I've used a few examples of Moche art in my work for years and thought I knew something about it. This incredible book set me straight. Mr. Donnan's text and Donna McClelland's extraordinary rollout drawings have brought the work of long dead Moche artists to life in a way that leaves me hungering for more. Wonderfully designed and painstakingly illustrated, this volume is a treasure-trove of information on this amazing culture. Exceptional in every way!

REVIEW: The "Bible" on this subject matter. Profusly illustrated; a culmination of some 30 years study on this subject. Highly reccomended.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

REVIEW: The Moche peoples of ancient Peru (100 BC - 800 AD) portrayed complex scenes on fineline painted ceramic vessels, depicting everything from hunting and fishing to the ritual battles of supernaturals.

REVIEW: Moche civilization flourished on the north coast of Peru between AD 100 and 800. Although the Moche people had no writing system, they left a vivid artistic record of their beliefs and activities in beautifully sculpted and painted ceramic vessels, colorful wall murals, sumptuous textiles, and superbly crafted objects of gold, silver, and copper. Dos Cabezas is a spectacular early Moche settlement located at the delta of the Jequetepeque River. Consisting of pyramids, palaces and domestic areas, it is perhaps the largest early Moche settlement ever built.

REVIEW: The large copper bowl lay within my grasp, undisturbed for 1,500 years since it had been placed upside down over the dead man’s face. Our team had worked more than a month to reach this point in the excavation of one of the richest and most intriguing tombs ever found in Peru—the tomb of a Moche elite.

The Moche inhabited a series of river valleys along the arid coastal plain of northern Peru from about A.D. 100 to 800. Through farming and fishing, they supported a dense population and highly stratified society that constructed irrigation canals, pyramids, palaces, and temples. Although they had no writing system, the Moche left a vivid artistic record of their activities in beautiful ceramic vessels, elaborately woven textiles, colorful murals, and wondrous objects of gold, silver, and

Finding undisturbed Moche tombs is rare in an area that has been looted for more than four centuries, yet from 1997 to 1999 our team of U.S. and Peruvian researchers discovered three extraordinary tombs at Dos Cabezas, an ancient settlement in the lower Jequetepeque Valley. Outside each burial chamber was a miniature tomb containing a small copper statue meant to represent the tomb’s principal occupant. Each tomb also contained a remarkably tall adult male who would have been a giant among his peers.

Gently lifting the copper bowl, I expected to see a skeletonized face. But instead, looking up at me with inlaid eyes, was an exquisite gold-and-copper funerary mask. We were all astonished and knew then how important these tombs could be to unraveling the mystery of the Moche. [National Geographic].

REVIEW: Moche society flourished on the north Peruvian coastal desert between the first and the eighth centuries A.D., in valleys irrigated by rivers flowing westward from the Andes to the Pacific Ocean. The Moche were innovators on many political, ideological, and artistic levels. They developed a powerful elite and specialized craft production, and instituted labor tribute payments. They elaborated new technologies in metallurgy, pottery, and textile production, and finally, they created an elaborate ideological system and a complex religious

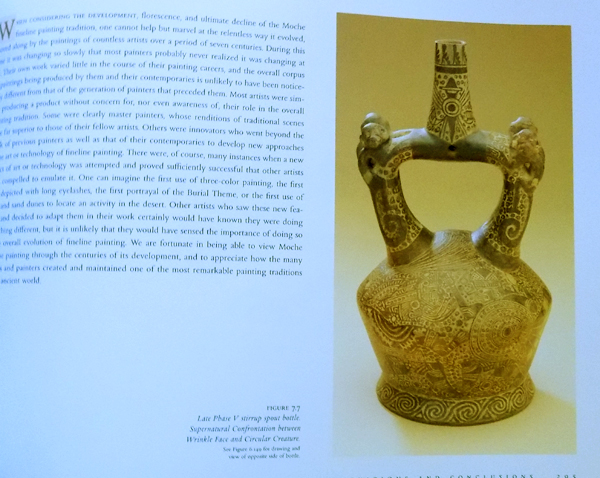

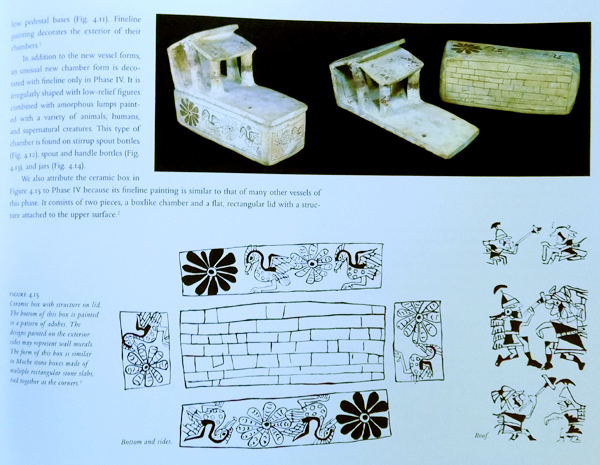

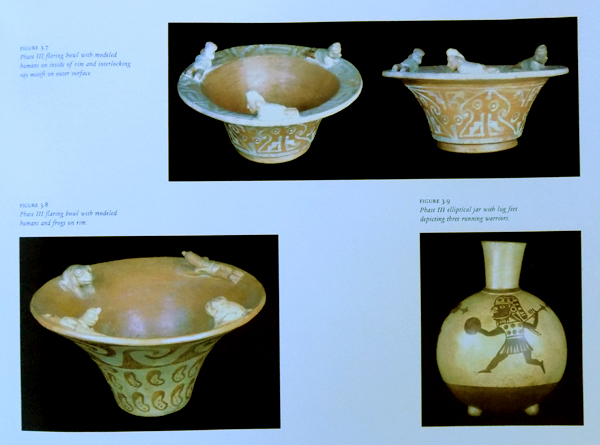

Moche skilled ceramists produced a great variety of exquisitely decorated vessels. The decoration is sometimes painted on the smooth surface of vessels; other times it is tridimensional, forming the vessel shape itself. Occasionally, the message takes both a painted and sculpted form, one completing the other. Nearly all decorated vessels are slip-painted and bichrome, with red decoration on a white/cream background. White on red and black postfire paint are also present to a lesser extent. While painted motifs are generally simple on three-dimensional vessels, two-dimensional decoration sometimes takes the shape of finely painted, highly complex narrative scenes.

Moche decorated vessels were mold-made and, despite their diversity, reveal standardized shapes and decoration. Nine basic shapes are reported in the literature. Stirrup-spout bottles and flaring bowls are the privileged supports on which artists expressed figurative, complex painted scenes. Other shapes are neck and neckless jars, dippers, bowls, neck bowls, cups, and crucibles. Moche ceramic art represents an infinite variety of subjects. Common zoomorphic figures include camelids, deer, felines, foxes, rodents, monkeys, bats, sea lions, as well as a wide array of birds, fish, shells, arachnids, and reptiles. These animals are represented realistically, hybridized, or anthropomorphized.

Corn, squash, tubers, and beans are common among a great diversity of plants. Among human and anthropomorphic figures, rulers, warriors, prisoners, priests, healers, and fanged deities are recognizable, as well as deformed and skeletal individuals. Historical individuals are also represented in realistic, three-dimensional portrait vessels. While animals are often anthropomorphized or hybridized, humans often have supernatural

All these figures are either represented alone or interacting in a variety of actions in diverse narrative scenes. Although the possibilities of creating different scenes from all existing Moche figures are almost limitless, major trends can be recognized in narrative art and representations are limited to a small number of recurring and interrelated themes. For example, deer and seal hunts, sacrifice ceremonies, warriors in battle or moving in processions, and messengers running in line are common themes in Moche ceramic

Scholars do not agree about the various functions of Moche decorated ceramics. Until recently, these works of art were thought to be essentially funerary offerings, as they were documented in a great number of burials. Indeed, fineware is the offering par excellence in burials of any social status as a marker of Moche social identity. Decorated vessels were imbued with a strong funerary dimension. However, many vessels uncovered in Moche burials show traces of abrasion, chipping, or repairs.

Recent excavations in residential areas, notably in the Moche and Santa Valleys in projects carried out by Universidad Nacional de Trujillo and Université de Montréal, revealed that finely decorated pottery is not only present but abundant in Moche domestic compounds. Many decorated vessels were not produced exclusively for a funerary purpose. Whereas many of them were ultimately placed in burials or made especially for the dead, most were produced to be used by the living in everyday life. The access to decorated vessels by the living was not unrestricted; some categories of vessels, as well as depictions of some religious themes, were exclusively destined for burial with the dead or for use in elite ritual performances. However, a great variety of vessels, many of them identical to those found in graves, were destined for domestic use.

Vessels decorated with religious themes were not merely indicators of social status at the site of Moche. They were strategically used at a household level, as tools to further political ambitions and communicate membership within groups. As evidenced by their iconographic content and the location in which they were abandoned, decorated vessels were an integral part of household-level rituals, meetings, and other status-building activities like feasts, where they were displayed, used, accidentally broken, and in some cases given away along with food and corn beer.

Vessels decorated with religious themes were not merely indicators of social status at the site of Moche. They were strategically used at a household level, as tools to further political ambitions and communicate membership within groups. As evidenced by their iconographic content and the location in which they were abandoned, decorated vessels were an integral part of household-level rituals, meetings, and other status-building activities like feasts, where they were displayed, used, accidentally broken, and in some cases given away along with food and corn beer.

REVIEW: The Moche (also known as the Mochicas) flourished on Peru’s North Coast from A.D. 200-850, centuries before the rise of the Inca. Over the course of some six centuries they built thriving regional centers from the Nepeña River Valley in the south to perhaps as far north as the Piura River, near the modern border with Ecuador, developing coastal deserts into rich farmlands and drawing upon the abundant maritime resources of the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. Although the Moche never formed a single centralized political entity, they shared unifying cultural traits such as religious practices.

Archaeologists in the middle of the twentieth century dubbed the time when the Moche came to power as the “Mastercraftsman Period” for its striking technological innovations in the arts. Moche artists are well-known for their developments in metal working, but they also excelled at the creation of micro-mosaics, shaping tiny pieces of highly valued materials such as shell, turquoise, and other blue-green stones into tesserae that would be fitted into gold, silver, or wood supports.

REVIEW: The Moche balanced stylized painting with realistic representations. On an arid plain in a valley in northern Peru, the site of Moche is dominated by two enormous stepped platforms known as the Huaca de la Luna and the Huaca del Sol, or the Pyramids of the Moon and the Sun. As excavators have cleared the exterior and interior walls of the Pyramid of the Moon, they have discovered large painted murals and friezes depicting warfare, ritual decapitation, complex geometric designs, fearsome portraits of Moche deities like the Decapitator--a bulge-eyed, sharp-toothed deity that resembles an octopus--and terrestrial and sea creatures in bright yellow, red, white, and black. The Moche--a culture group occupying the valley of Peru's north coast from about A.D. 100 and known primarily for its advanced agricultural knowledge and masterful pottery and metalwork--clearly dominated the site from about A.D. 150 to 750, during which time it served as the spiritual and political capital of a large territory, incorporating at least the four nearest valleys, about 2,500 square miles.

Excavations of the last decade at the Pyramid of the Moon and the urban area between the two platforms have provided Moche specialists with an abundance of information about the ritual and everyday lives of those they study. Before now, the best evidence for ritual came from extraordinary and often gruesome artwork, primarily depicted on ceramics. Vessels in the form of stirrup-spouted bottles with molded figures and intricate fine-line painting show warrior-priests bedecked in imposing ornate garb orchestrating ritual warfare; slitting captives' throats, drinking their blood, and hanging their defleshed bones from ropes; and participating in acts of sodomy and fellatio, all in a context of structured ceremony. In the absence of archaeological evidence, most scholars found many of the scenes too horrific to take literally, often suggesting they were simply artistic hyperbole, imagery the priestly class used to underscore its coercive

The Pyramid of the Moon would have intimidated captives led up its long ramp to meet their fates in ritual sacrifice. The remains of the building's facade and its ramp are in the process of restoration. Under the direction of Santiago Uceda of the University of Trujillo, Steve Bourget of the University of Texas at Austin and his colleague John Verano of Tulane University have discovered at the Pyramids at Moche new evidence proving that the shocking scenes depicted in Moche art are faithful representations of actual behavior, if not records of specific events. Bourget and his team uncovered a sacrificial plaza with the remains of at least 70 individuals--representing several sacrifice events--embedded in the mud of the plaza, accompanied by almost as many ceramic statuettes of captives. It is the first archaeological evidence of large-scale sacrifice found at a Moche site and just one of many discoveries made in the last decade at the site.

In 1999, Verano began his own excavations of a plaza near that investigated by Bourget. He found two layers of human remains, one dating to A.D. 150 to 250 and the other to A.D. 500. In both deposits, as with Bourget's, the individuals were young men at the time of death. They had multiple healed fractures to their ribs, shoulder blades, and arms suggesting regular participation in combat. They also had cut marks on their neck vertebrae indicating their throats had been slit. The remains Verano found differed from those in the sacrificial plaza found by Bourget in one important aspect: they appeared to have been deliberately defleshed, a ritual act possibly conducted so the cleaned bones could be hung from the pyramid as trophies--a familiar theme depicted in Moche art.

Even with all this new evidence, much remains to be learned about the lives of the people involved in the ritual system, about how the Moche organized themselves into villages and cities in the north coast valleys, how power was won and lost, who was involved in warfare and how they fought, and of course, what ultimately happened to them. Investigations in the urban sector of the site have started to address some of these questions.

MESO-AMERICAN MOCHE: The Moche Civilization (also known as the Mochica) flourished along the northern coast and valleys of ancient Peru, in particular, in the Chicama and Trujillo Valleys, during the first eight centuries of the current era (0-800 AD). The Moche state eventually expanded to cover an area from the Huarmey Valley in the south to the Piura Valley in the north. The Moche even expanded their influence as far afield as the Chincha Islands. Moche territory was divided linguistically by two separate but related languages: Muchic (spoken north of the Lambayeque Valley) and Quingan.

The two areas also display slightly different artistic and architectural trends and so the Moche state may be better described as a loose confederacy rather than a single, unified entity. The Moche were contemporary with the Nazca civilization (200 BC - 600 AD) further down the coast. However thanks to their conquest of surrounding territories, they were able to accumulate the wealth and power necessary to establish themselves as one of the most unique and important early-Andean cultures.

The Moche also expressed themselves in art with such a high degree of aesthetics that their naturalistic and vibrant murals, ceramics, and metalwork are amongst the most highly regarded in the Americas. The Moche were perhaps the most accomplished artists and metalworkers of any Andean civilization. The capital was known simply as “Moche”. Giving its name to the civilization which founded it, the city lies at the foot of the Cerro Blanco mountain. It once covered an area of 750 acres.

Besides urban housing, plazas, storehouses, and workshop buildings, it also has impressive monuments. These includes two massive adobe brick pyramid-like mounds. These monumental structures, in their original state, display typical traits of Moche architecture: multiple levels, access ramps, and slanted roofing. The larger 'pyramid' is the Huaca del Sol, which has four tiers and today still stands 130 feet high. Originally it stood over 165 feet high, covered an area of about 550,000 square feet, and was constructed using over 140 million bricks, each stamped with a maker's mark.

Besides urban housing, plazas, storehouses, and workshop buildings, it also has impressive monuments. These includes two massive adobe brick pyramid-like mounds. These monumental structures, in their original state, display typical traits of Moche architecture: multiple levels, access ramps, and slanted roofing. The larger 'pyramid' is the Huaca del Sol, which has four tiers and today still stands 130 feet high. Originally it stood over 165 feet high, covered an area of about 550,000 square feet, and was constructed using over 140 million bricks, each stamped with a maker's mark.

A ramp on the north side gives access to the summit, which is a platform in the form of a cross. The smaller structure, known as the Huaca de la Luna, stands 1650 feet away and was built using some 50 million adobe bricks. It has three tiers and is decorated with friezes showing Moche mythology and rituals. The entire structure was once enclosed within a high adobe brick wall. Both pyramids were constructed around 450 AD, were originally brightly colored in red, white, yellow, and black, and were used as an imposing setting to perform rituals and ceremonies.

The Spanish conquistadors later diverted the Rio Moche (river) in order to break down the Huaca del Sol and loot the tombs within. This suggests that the pyramid was also used by the Moche for generations as a mausoleum for important persons. Buildings excavated between the two pyramid-mounds include many large residences with courtyards enclosed by walls. The fields around the site are laid out in a regular grid pattern of small rectangular plots often with a small adobe viewing platform. This aspect suggests some sort of state supervision and control by the elite (Kuraka) class.

Moche agriculture benefited from an extensive system of canals, reservoirs, and aqueducts, so that the land could support a population of around 25,000. Other Moche sites include a pilgrimage centre at Pacatnamú, a mountain top site above the Jequetepeque River which was actually used all the way back to the Early Intermediate Period (about 200 BC). There were also administrative centers at Panamarca. There there is another large adobe brick mound. This particular structure possessed a switch-back ramp leading to the top of the structure, as did similar structures at Huancaco in the Viru Valley and Pampa de Los Incas in the Santa Valley.

Moche agriculture benefited from an extensive system of canals, reservoirs, and aqueducts, so that the land could support a population of around 25,000. Other Moche sites include a pilgrimage centre at Pacatnamú, a mountain top site above the Jequetepeque River which was actually used all the way back to the Early Intermediate Period (about 200 BC). There were also administrative centers at Panamarca. There there is another large adobe brick mound. This particular structure possessed a switch-back ramp leading to the top of the structure, as did similar structures at Huancaco in the Viru Valley and Pampa de Los Incas in the Santa Valley.

Moche religion and art were initially influenced by the earlier Chavin culture (existing from about 900 to 200 BC) and in the final stages by the Chimú culture. Knowledge of the Moche pantheon is sketchy, but we do know of Al Paec the creator or sky god (or his son) and Si the moon goddess. Al Paec, typically depicted in Moche art with ferocious fangs, a jaguar headdress, and snake earrings, was considered to dwell in the high mountains. Human sacrifices, especially of war prisoners but also Moche citizens, were offered to appease him. The victims’ blood was offered in ritual goblets.

Si was considered the supreme deity. Si was the goddess that controlled the seasons and storms that had such an influence on agriculture and daily life. In addition, the moon was considered even more powerful than the sun because Si could be seen both at night and during the day. It is also interesting that murals and such finds as the intact tomb of the priestess known as La Senora de Cao illustrate that women could play a prominent role in Moche religion and ceremony.

The bones of these skeletons display cut marks, limbs were ripped out of their sockets, and jaw bones are missing from severed skulls. Interestingly, the bodies lie above soft ground caused by heavy El Nino rains, which suggests the sacrifices may have been offered to the Moche gods in order to alleviate this environmental disaster. Ceremonial goblets have also been discovered which contain traces of human blood, and tombs have revealed costumed and be-jeweled individuals almost exactly like the religious figures depicted in Moche murals.

The bones of these skeletons display cut marks, limbs were ripped out of their sockets, and jaw bones are missing from severed skulls. Interestingly, the bodies lie above soft ground caused by heavy El Nino rains, which suggests the sacrifices may have been offered to the Moche gods in order to alleviate this environmental disaster. Ceremonial goblets have also been discovered which contain traces of human blood, and tombs have revealed costumed and be-jeweled individuals almost exactly like the religious figures depicted in Moche murals.

Many fine examples of Moche art have been recovered from tombs at Sipán (circa 300 AD), San José de Moro (circa 550 AD), and Huaca Cao Viejo. These are amongst some of the best preserved burial sites from any Andean culture. The Moche were gifted potters and superb metalworkers. Finds include exquisite gold headdresses and chest plates, gold, silver, and turquoise jewelry (especially ear-spools and nose ornaments), textiles, tumi knives, and copper bowls and drinking vessels.

Fine pottery vessels were usually made using mould. However even when moulded each was individually and distinctively decorated, typically using cream, reds, and browns. Perhaps the most famous vessels are the highly realistic portrait stirrup-spouted pots. These are considered portraits of real people, and several examples could be made depicting the same individual. Indeed one face - easily identified by his cut lip - appears in over 40 such pots.

Fine pottery vessels were usually made using mould. However even when moulded each was individually and distinctively decorated, typically using cream, reds, and browns. Perhaps the most famous vessels are the highly realistic portrait stirrup-spouted pots. These are considered portraits of real people, and several examples could be made depicting the same individual. Indeed one face - easily identified by his cut lip - appears in over 40 such pots.

Pottery shapes and decorations did evolve over time and became more and more elaborate. Conversely themes became less various in later Moche pottery and art in general. One of the most distinctive styles created by the Moche uses silhouette figures embellished with fine line details very similar to Greek black-figure pottery. Ceramic effigy figures are also common, especially of musicians, priestesses, and captives.

Popular subjects in Moche art include humans, anthropomorphic figures (especially fanged felines), and animals such as snakes, frogs, birds (especially owls), fish, and crabs. These are evidenced in wall paintings, friezes, pottery decoration, and fine metal objects. Whole scenes are also common. This is especially with respect to religious ceremonies with Bird and Warrior Priests, shamans, coca rituals, armored warriors, ritual and real warfare with their resulting captives, hunting episodes, and, of course, deities. Most notably these include scenes showing night skies across which crescent boats carry figures such as Si. Many of these scenes are rendered to capture narratives and, above all, action. Figures are always depicted doing something in Moche art.

At Sipán some of the best preserved and richest tombs in the Americas have been discovered. These include the famous 'Warrior Priest' tomb with its outstanding precious metal objects such as a gold mask, ear-spools, bracelets, body armor, scepter, ingots, and magnificently crafted silver and gold peanut necklace. The site of Pampa Grande covered 1500 acres and included the once 180 foot high Huaca Fortaleza ritual platform.

Reached by a 900 foot ramp the summit had a columned structure containing a mural of felines. However after 150 years of occupation the site was also abandoned. Obce again this was probably due to a combination of climatic factors such as an extended period of drought. This appears to have been accompanied by Huari expansion and internal strife, as indicated by evidence of fire damage to many of the buildings. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

MESOAMERICA: Mesoamerica was a region and cultural area in the Americas, extending from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica, and within which pre-Columbian societies flourished before the Spanish colonization of the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. It is one of six areas in the world where ancient civilization arose independently, and the second in the Americas along with Norte Chico (Caral-Supe) in present-day northern coastal Peru.

MESOAMERICA: Mesoamerica was a region and cultural area in the Americas, extending from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica, and within which pre-Columbian societies flourished before the Spanish colonization of the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. It is one of six areas in the world where ancient civilization arose independently, and the second in the Americas along with Norte Chico (Caral-Supe) in present-day northern coastal Peru.

As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures. Beginning as early as 7000 B.C., the domestication of cacao, maize, beans, tomato, squash and chili, as well as the turkey and dog, caused a transition from paleo-Indian hunter-gatherer tribal grouping to the organization of sedentary agricultural villages. In the subsequent Formative period, agriculture and cultural traits such as a complex mythological and religious tradition, a vigesimal numeric system, and a complex calendric system, a tradition of ball playing, and a distinct architectural style, were diffused through the area.

Also in this period, villages began to become socially stratified and develop into chiefdoms with the development of large ceremonial centers, interconnected by a network of trade routes for the exchange of luxury goods, such as obsidian, jade, cacao, cinnabar, Spondylus shells, hematite, and ceramics. While Mesoamerican civilization did know of the wheel and basic metallurgy, neither of these technologies became culturally important. Among the earliest complex civilizations was the Olmec culture, which inhabited the Gulf coast of Mexico and extended inland and southwards across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and the Zapotec cultures, and the Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic Maya hieroglyphic script. Mesoamerica is one of only three regions of the world where writing is known to have independently developed (the others being ancient Sumer and China). In Central Mexico, the height of the Classic period saw the ascendancy of the city of Teotihuacan, which formed a military and commercial empire whose political influence stretched south into the Maya area and northward. Upon the collapse of Teotihuacán around A.D. 600, competition between several important political centers in central Mexico, such as Xochicalco and Cholula, ensued.

During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and the Zapotec cultures, and the Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic Maya hieroglyphic script. Mesoamerica is one of only three regions of the world where writing is known to have independently developed (the others being ancient Sumer and China). In Central Mexico, the height of the Classic period saw the ascendancy of the city of Teotihuacan, which formed a military and commercial empire whose political influence stretched south into the Maya area and northward. Upon the collapse of Teotihuacán around A.D. 600, competition between several important political centers in central Mexico, such as Xochicalco and Cholula, ensued.

At this time during the Epi-Classic period, the Nahua peoples began moving south into Mesoamerica from the North, and became politically and culturally dominant in central Mexico, as they displaced speakers of Oto-Manguean languages. During the early post-Classic period, Central Mexico was dominated by the Toltec culture, Oaxaca by the Mixtec, and the lowland Maya area had important centers at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. Towards the end of the post-Classic period, the Aztecs of Central Mexico built a tributary empire covering most of central Mesoamerica.

The distinct Mesoamerican cultural tradition ended with the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. Over the next centuries, Mesoamerican indigenous cultures were gradually subjected to Spanish colonial rule. Aspects of the Mesoamerican cultural heritage still survive among the indigenous peoples who inhabit Mesoamerica, many of whom continue to speak their ancestral languages, and maintain many practices harking back to their Mesoamerican roots. The term Mesoamerica – literally, "middle America" in Greek – is defined as the area that is home to the Mesoamerican civilization, which comprises a group of peoples with close cultural and historical ties.

The exact geographic extent of Mesoamerica has varied through time, as the civilization extended North and South from its heartland in southern Mexico. The term was first used by the German ethnologist Paul Kirchhoff, who noted that similarities existed among the various pre-Columbian cultures within the region that included southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, western Honduras, and the Pacific lowlands of Nicaragua and northwestern Costa Rica. In the tradition of cultural history, the prevalent archaeological theory of the early to middle 20th century, Kirchhoff defined this zone as a cultural area based on a suite of interrelated cultural similarities brought about by millennia of inter- and intra-regional interaction (i.e., diffusion).

The exact geographic extent of Mesoamerica has varied through time, as the civilization extended North and South from its heartland in southern Mexico. The term was first used by the German ethnologist Paul Kirchhoff, who noted that similarities existed among the various pre-Columbian cultures within the region that included southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, western Honduras, and the Pacific lowlands of Nicaragua and northwestern Costa Rica. In the tradition of cultural history, the prevalent archaeological theory of the early to middle 20th century, Kirchhoff defined this zone as a cultural area based on a suite of interrelated cultural similarities brought about by millennia of inter- and intra-regional interaction (i.e., diffusion).

Mesoamerica is recognized as a near-prototypical cultural area, and the term is now fully integrated in the standard terminology of pre-Columbian anthropological studies. Conversely, the sister terms Aridoamerica and Oasisamerica, which refer to northern Mexico and the western United States, respectively, have not entered into widespread usage. Some of the significant cultural traits defining the Mesoamerican cultural tradition are:

sedentism based on maize agriculture;

the construction of stepped pyramids;

the use of two different calendars (a 260-day ritual calendar and a 365-day calendar based on the solar year);

vigesimal (base 20) number system;

the use of locally developed pictographic and hieroglyphic (logo-syllabic) writing systems;

the use of rubber and the practice of the Mesoamerican ballgame;

the use of bark paper for ritual purposes and as a medium for writing;

the practice of various forms of sacrifice, including Human sacrifice;

a religious complex based on a combination of shamanism and natural deities, and a shared system of symbols;

a linguistic area defined by a number of grammatical traits that have spread through the area by diffusion.

The highlands show much more climatic diversity, ranging from dry tropical to cold mountainous climates; the dominant climate is temperate with warm temperatures and moderate rainfall. The rainfall varies from the dry Oaxaca and north Yucatán to the humid southern Pacific and Caribbean lowlands. Several distinct sub-regions within Mesoamerica are defined by a convergence of geographic and cultural attributes. These sub-regions are more conceptual than culturally meaningful, and the demarcation of their limits is not rigid.

The highlands show much more climatic diversity, ranging from dry tropical to cold mountainous climates; the dominant climate is temperate with warm temperatures and moderate rainfall. The rainfall varies from the dry Oaxaca and north Yucatán to the humid southern Pacific and Caribbean lowlands. Several distinct sub-regions within Mesoamerica are defined by a convergence of geographic and cultural attributes. These sub-regions are more conceptual than culturally meaningful, and the demarcation of their limits is not rigid.

The Maya area, for example, can be divided into two general groups: the lowlands and highlands. The lowlands are further divided into the southern and northern Maya lowlands. The southern Maya lowlands are generally regarded as encompassing northern Guatemala, southern Campeche and Quintana Roo in Mexico, and Belize. The northern lowlands cover the remainder of the northern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula. Other areas include Central Mexico, West Mexico, the Gulf Coast Lowlands, Oaxaca, the Southern Pacific Lowlands, and Southeast Mesoamerica (including northern Honduras).

There is extensive topographic variation in Mesoamerica, ranging from the high peaks circumscribing the Valley of Mexico and within the central Sierra Madre mountains to the low flatlands of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The tallest mountain in Mesoamerica is Pico de Orizaba, a dormant volcano located on the border of Puebla and Veracruz. Its peak elevation is 5,636 meters (18,490 feet). The Sierra Madre mountains, which consist of several smaller ranges, run from northern Mesoamerica south through Costa Rica. The chain is historically volcanic.

There is extensive topographic variation in Mesoamerica, ranging from the high peaks circumscribing the Valley of Mexico and within the central Sierra Madre mountains to the low flatlands of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The tallest mountain in Mesoamerica is Pico de Orizaba, a dormant volcano located on the border of Puebla and Veracruz. Its peak elevation is 5,636 meters (18,490 feet). The Sierra Madre mountains, which consist of several smaller ranges, run from northern Mesoamerica south through Costa Rica. The chain is historically volcanic.

In central and southern Mexico, a portion of the Sierra Madre chain is known as the Eje Volcánico Transversal, or the Trans-Mexican volcanic belt. There are 83 inactive and active volcanoes within the Sierra Madre range, including 11 in Mexico, 37 in Guatemala, 23 in El Salvador, 25 in Nicaragua, and 3 in northwestern Costa Rica. According to the Michigan Technological University, 16 of these are still active. The tallest active volcano is Popocatépetl at 5,452 meters (17,887 feet). This volcano, which retains its Nahuatl name, is located 70 kilometers (43 miles) southeast of Mexico City.

Other volcanoes of note include Tacana on the Mexico–Guatemala border, Tajumulco and Santamaría in Guatemala, Izalco in El Salvador, Momotombo in Nicaragua, and Arenal in Costa Rica. One important topographic feature is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a low plateau that breaks up the Sierra Madre chain between the Sierra Madre del Sur to the north and the Sierra Madre de Chiapas to the south. At its highest point, the Isthmus is 224 meters (735 feet) above mean sea level. This area also represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean in Mexico.

The longest river in Mesoamerica is the Usumacinta, which forms in Guatemala at the convergence of the Salinas or Chixoy and La Pasion River and runs north for 970 kilometers (600 miles) – 480 kilometers (300 miles) of which are navigable – eventually draining into the Gulf of Mexico. Other rivers of note include the Rio Grande de Santiago, the Grijalva River, the Motagua River, the Ulúa River, and the Hondo River. The northern Maya lowlands, especially the northern portion of the Yucatán peninsula, are notable for their nearly complete lack of rivers (largely due to the absolute lack of topographic variation).

The longest river in Mesoamerica is the Usumacinta, which forms in Guatemala at the convergence of the Salinas or Chixoy and La Pasion River and runs north for 970 kilometers (600 miles) – 480 kilometers (300 miles) of which are navigable – eventually draining into the Gulf of Mexico. Other rivers of note include the Rio Grande de Santiago, the Grijalva River, the Motagua River, the Ulúa River, and the Hondo River. The northern Maya lowlands, especially the northern portion of the Yucatán peninsula, are notable for their nearly complete lack of rivers (largely due to the absolute lack of topographic variation).

Additionally, no lakes exist in the northern peninsula. The main source of water in this area is aquifers that are accessed through natural surface openings called cenotes. With an area of 8,264 square kilometers (3,191 square miles), Lake Nicaragua is the largest lake in Mesoamerica. Lake Chapala is Mexico’s largest freshwater lake, but Lake Texcoco is perhaps most well known as the location upon which Tenochtitlan, capital of the Aztec Empire, was founded. Lake Petén Itzá, in northern Guatemala, is notable as the location at which the last independent Maya city, Tayasal (or Noh Petén), held out against the Spanish until 1697.

Other large lakes include Lake Atitlán, Lake Izabal, Lake Güija, Lemoa, and Lake Managua. Almost all ecosystems are present in Mesoamerica; the more well known are the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, the second largest in the world, and La Mosquitia (consisting of the Rio Platano Biosphere Reserve, Tawahka Asangni, Patuca National Park, and Bosawas Biosphere Reserve) a rainforest second in size in the Americas only to the Amazonas. The highlands present mixed and coniferous forest. The biodiversity is among the richest in the world, although the number of species in the red list of the IUCN is growing every year.

Other large lakes include Lake Atitlán, Lake Izabal, Lake Güija, Lemoa, and Lake Managua. Almost all ecosystems are present in Mesoamerica; the more well known are the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, the second largest in the world, and La Mosquitia (consisting of the Rio Platano Biosphere Reserve, Tawahka Asangni, Patuca National Park, and Bosawas Biosphere Reserve) a rainforest second in size in the Americas only to the Amazonas. The highlands present mixed and coniferous forest. The biodiversity is among the richest in the world, although the number of species in the red list of the IUCN is growing every year.

Tikal is one of the largest archaeological sites, urban centers, and tourist attractions of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It is located in the archaeological region of the Petén Basin in what is now northern Guatemala. The history of human occupation in Mesoamerica is divided into stages or periods. These are known, with slight variation depending on region, as the Paleo-Indian, the Archaic, the Preclassic (or Formative), the Classic, and the Postclassic. The last three periods, representing the core of Mesoamerican cultural fluorescence, are further divided into two or three sub-phases. Most of the time following the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century is classified as the Colonial period.

The differentiation of early periods (i.e., up through the end of the Late Preclassic) generally reflects different configurations of socio-cultural organization that are characterized by increasing socio-political complexity, the adoption of new and different subsistence strategies, and changes in economic organization (including increased interregional interaction). The Classic period through the Postclassic are differentiated by the cyclical crystallization and fragmentation of the various political entities throughout Mesoamerica.

Archaic sites include Sipacate in Escuintla, Guatemala, where maize pollen samples date to circa 3500 B.C. The well-known Coxcatlan cave site in the Valley of Tehuacán, Puebla, which contains over 10,000 teosinte cobs (an antecedent to maize), and Guilá Naquitz in Oaxaca represent some of the earliest examples of agriculture in Mesoamerica. The early development of pottery, often seen as a sign of sedentism, has been documented at several sites, including the West Mexican sites of Matanchén in Nayarit and Puerto Marqués in Guerrero. La Blanca, Ocós, and Ujuxte in the Pacific Lowlands of Guatemala yielded pottery dated to circa 2500 B.C.

Archaic sites include Sipacate in Escuintla, Guatemala, where maize pollen samples date to circa 3500 B.C. The well-known Coxcatlan cave site in the Valley of Tehuacán, Puebla, which contains over 10,000 teosinte cobs (an antecedent to maize), and Guilá Naquitz in Oaxaca represent some of the earliest examples of agriculture in Mesoamerica. The early development of pottery, often seen as a sign of sedentism, has been documented at several sites, including the West Mexican sites of Matanchén in Nayarit and Puerto Marqués in Guerrero. La Blanca, Ocós, and Ujuxte in the Pacific Lowlands of Guatemala yielded pottery dated to circa 2500 B.C.

The first complex civilization to develop in Mesoamerica was that of the Olmec, who inhabited the gulf coast region of Veracruz throughout the Preclassic period. The main sites of the Olmec include San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes. Although specific dates vary, these sites were occupied from roughly 1200 to 400 B.C. Remains of other early cultures interacting with the Olmec have been found at Takalik Abaj, Izapa, and Teopantecuanitlan, and as far south as in Honduras. Research in the Pacific Lowlands of Chiapas and Guatemala suggest that Izapa and the Monte Alto Culture may have preceded the Olmec.

Radiocarbon samples associated with various sculptures found at the Late Preclassic site of Izapa suggest a date of between 1800 and 1500 B.C. During the Middle and Late Preclassic period, the Maya civilization developed in the southern Maya highlands and lowlands, and at a few sites in the northern Maya lowlands. The earliest Maya sites coalesced after 1000 B.C., and include Nakbe, El Mirador, and Cerros. El Mirador flourished from 600 B.C. to A.D. 100, and may have had a population of over 100,000. Middle to Late Preclassic Maya sites include Kaminaljuyú, Cival, Edzná, Cobá, Lamanai, Komchen, Dzibilchaltun, and San Bartolo, among others.

Radiocarbon samples associated with various sculptures found at the Late Preclassic site of Izapa suggest a date of between 1800 and 1500 B.C. During the Middle and Late Preclassic period, the Maya civilization developed in the southern Maya highlands and lowlands, and at a few sites in the northern Maya lowlands. The earliest Maya sites coalesced after 1000 B.C., and include Nakbe, El Mirador, and Cerros. El Mirador flourished from 600 B.C. to A.D. 100, and may have had a population of over 100,000. Middle to Late Preclassic Maya sites include Kaminaljuyú, Cival, Edzná, Cobá, Lamanai, Komchen, Dzibilchaltun, and San Bartolo, among others.

The Preclassic in the central Mexican highlands is represented by such sites as Tlapacoya, Tlatilco, and Cuicuilco. These sites were eventually superseded by Teotihuacán, an important Classic-era site that eventually dominated economic and interaction spheres throughout Mesoamerica. The settlement of Teotihuacan is dated to the later portion of the Late Preclassic, or roughly A.D. 50. In the Valley of Oaxaca, San José Mogote represents one of the oldest permanent agricultural villages in the area, and one of the first to use pottery. During the Early and Middle Preclassic, the site developed some of the earliest examples of defensive palisades, ceremonial structures, the use of adobe, and hieroglyphic writing.

Also of importance, the site was one of the first to demonstrate inherited status, signifying a radical shift in socio-cultural and political structure. San José Mogote was eventual overtaken by Monte Albán, the subsequent capital of the Zapotec empire, during the Late Preclassic. The Preclassic in western Mexico, in the states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima, and Michoacán also known as the Occidente, is poorly understood. This period is best represented by the thousands of figurines recovered by looters and ascribed to the "shaft tomb tradition".

The Classic period is marked by the rise and dominance of several polities. The traditional distinction between the Early and Late Classic are marked by their changing fortune and their ability to maintain regional primacy. Of paramount importance are Teotihuacán in central Mexico and Tikal in Guatemala; the Early Classic’s temporal limits generally correlate to the main periods of these sites. Monte Alban in Oaxaca is another Classic-period polity that expanded and flourished during this period, but the Zapotec capital exerted less interregional influence than the other two sites.

During the Early Classic, Teotihuacan participated in and perhaps dominated a far-reaching macro-regional interaction network. Architectural and artifact styles (talud-tablero, tripod slab-footed ceramic vessels) epitomized at Teotihuacan were mimicked and adopted at many distant settlements. Pachuca obsidian, whose trade and distribution is argued to have been economically controlled by Teotihuacan, is found throughout Mesoamerica. Tikal came to dominate much of the southern Maya lowlands politically, economically, and militarily during the Early Classic.

An exchange network centered at Tikal distributed a variety of goods and commodities throughout southeast Mesoamerica, such as obsidian imported from central Mexico (e.g., Pachuca) and highland Guatemala (e.g., El Chayal, which was predominantly used by the Maya during the Early Classic), and jade from the Motagua valley in Guatemala. Tikal was often in conflict with other polities in the Petén Basin, as well as with others outside of it, including Uaxactun, Caracol, Dos Pilas, Naranjo, and Calakmul. Towards the end of the Early Classic, this conflict lead to Tikal’s military defeat at the hands of Caracol in 562, and a period commonly known as the Tikal Hiatus.

The Late Classic period (beginning about A.D. 600 until A.D. 909 [varies]) is characterized as a period of interregional competition and factionalization among the numerous regional polities in the Maya area. This largely resulted from the decrease in Tikal’s socio-political and economic power at the beginning of the period. It was therefore during this time that other sites rose to regional prominence and were able to exert greater interregional influence, including Caracol, Copán, Palenque, and Calakmul (which was allied with Caracol and may have assisted in the defeat of Tikal), and Dos Pilas Aguateca and Cancuén in the Petexbatún region of Guatemala.

Around 710, Tikal arose again and started to build strong alliances and defeat its worst enemies. In the Maya area, the Late Classic ended with the so-called "Maya collapse", a transitional period coupling the general depopulation of the southern lowlands and development and florescence of centers in the northern lowlands. Generally applied to the Maya area, the Terminal Classic roughly spans the time between A.D. 800/850 and about A.D. 1000. Overall, it generally correlates with the rise to prominence of Puuc settlements in the northern Maya lowlands, so named after the hills in which they are mainly found.

Puuc settlements are specifically associated with a unique architectural style (the "Puuc architectural style") that represents a technological departure from previous construction techniques. Major Puuc sites include Uxmal, Sayil, Labna, Kabah, and Oxkintok. While generally concentrated within the area in and around the Puuc hills, the style has been documented as far away as at Chichen Itza to the east and Edzna to the south. Chichén Itzá was originally thought to have been a Postclassic site in the northern Maya lowlands. Research over the past few decades has established that it was first settled during the Early/Late Classic transition but rose to prominence during the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic.

During its apogee, this widely known site economically and politically dominated the northern lowlands. Its participation in the circum-peninsular exchange route, possible through its port site of Isla Cerritos, allowed Chichén Itzá to remain highly connected to areas such as central Mexico and Central America. The apparent "Mexicanization" of architecture at Chichén Itzá led past researchers to believe that Chichén Itzá existed under the control of a Toltec empire. Chronological data refutes this early interpretation, and it is now known that Chichén Itzá predated the Toltec; Mexican architectural styles are now used as an indicator of strong economic and ideological ties between the two regions.

The Postclassic (beginning A.D. 900–1000, depending on area) is, like the Late Classic, characterized by the cyclical crystallization and fragmentation of various polities. The main Maya centers were located in the northern lowlands. Following Chichén Itzá, whose political structure collapsed during the Early Postclassic, Mayapán rose to prominence during the Middle Postclassic and dominated the north for about 200 years. After Mayapán’s fragmentation, political structure in the northern lowlands revolved around large towns or city-states, such as Oxkutzcab and Ti’ho (Mérida, Yucatán), that competed with one another.

Toniná, in the Chiapas highlands, and Kaminaljuyú in the central Guatemala highlands, were important southern highland Maya centers. The latter site, Kaminaljuyú, is one of the longest occupied sites in Mesoamerica and was continuously inhabited from circa 800 B.C. to around A.D. 1200. Other important highland Maya groups include the K'iche' of Utatlán, the Mam in Zaculeu, the Poqomam in Mixco Viejo, and the Kaqchikel at Iximche in the Guatemalan highlands. The Pipil resided in El Salvador, while the Ch'orti' were in eastern Guatemala and northwestern Honduras. In central Mexico, the early portion of the Postclassic correlates with the rise of the Toltec and an empire based at their capital, Tula (also known as Tollan).

Cholula, initially an important Early Classic center contemporaneous with Teotihuacan, maintained its political structure (it did not collapse) and continued to function as a regionally important center during the Postclassic. The latter portion of the Postclassic is generally associated with the rise of the Mexica and the Aztec Empire. One of the more commonly known cultural groups in Mesoamerica, the Aztec politically dominated nearly all of central Mexico, the Gulf Coast, Mexico’s southern Pacific Coast (Chiapas and into Guatemala), Oaxaca, and Guerrero.

The Tarascans (also known as the P'urhépecha) were located in Michoacán and Guerrero. With their capital at Tzintzuntzan, the Tarascan state was one of the few to actively and continuously resist Aztec domination during the Late Postclassic. Other important Postclassic cultures in Mesoamerica include the Totonac along the eastern coast (in the modern-day states of Veracruz, Puebla, and Hidalgo). The Huastec resided north of the Totonac, mainly in the modern-day states of Tamaulipas and northern Veracruz. The Mixtec and Zapotec cultures, centered at Mitla and Zaachila respectively, inhabited Oaxaca.

The Postclassic ends with the arrival of the Spanish and their subsequent conquest of the Aztec between 1519 and 1521. Many other cultural groups did not acquiesce until later. For example, Maya groups in the Petén area, including the Itza at Tayasal and the Kowoj at Zacpeten, remained independent until 1697. Some Mesoamerican cultures never achieved dominant status or left impressive archaeological remains but are nevertheless noteworthy. These include the Otomi, Mixe–Zoque groups (which may or may not have been related to the Olmecs), the northern Uto-Aztecan groups, often referred to as the Chichimeca, that include the Cora and Huichol, the Chontales, the Huaves, and the Pipil, Xincan and Lencan peoples of Central America.

By roughly 6000 B.C., hunter-gatherers living in the highlands and lowlands of Mesoamerica began to develop agricultural practices with early cultivation of squash and chilli. The earliest example of maize dates to circa 4000 B.C. and comes from Guilá Naquitz, a cave in Oaxaca. Earlier maize samples have been documented at the Los Ladrones cave site in Panama, circa 5500 B.C. Slightly thereafter, other crops began to be cultivated by the semi-agrarian communities throughout Mesoamerica. Although maize is the most common domesticate, the common bean, tepary bean, scarlet runner bean, jicama, tomato and squash all became common cultivates by 3500 B.C.

At the same time, cotton, yucca and agave were exploited for fibers and textile materials. By 2000 B.C., corn was the staple crop in the region and remained so through modern times. The Ramón or Breadnut tree (Brosimum alicastrum) was an occasional substitute for maize in producing flour. Fruit was also important in the daily diet of Mesoamerican cultures. Some of the main ones consumed include avocado, papaya, guava, mamey, zapote, and annona. Mesoamerica lacked animals suitable for domestication, most notably domesticated large ungulates – the lack of draft animals to assist in transportation is one notable difference between Mesoamerica and the cultures of the South American Andes.

Other animals, including the duck, dogs, and turkey, were domesticated. Turkey was the first, occurring around 3500 B.C. Dogs were the primary source of animal protein in ancient Mesoamerica, and dog bones are common in midden deposits throughout the region. Societies of this region did hunt certain wild species to complement their diet. These animals included deer, rabbit, birds, and various types of insects. They also hunted in order to gain luxury items such as feline fur and bird plumage.

Mesoamerican cultures that lived in the lowlands and coastal plains settled down in agrarian communities somewhat later than did highland cultures due to the fact that there was a greater abundance of fruits and animals in these areas, which made a hunter-gatherer lifestyle more attractive. Fishing also was a major provider of food to lowland and coastal Mesoamericans creating a further disincentive to settle down in permanent communities.

Temples provided spatial orientation, which was imparted to the surrounding town. The cities with their commercial and religious centers were always political entities, somewhat similar to the European city-state, and each person could identify himself with the city in which he lived. The ceremonial centers were always built to be visible. The pyramids were meant to stand out from the rest of the city, to represent its gods and their powers. Another characteristic feature of the ceremonial centers is historic layers.

All of the ceremonial edifices were built in various phases, one on top of the other, to the point that what we now see is usually the last stage of construction. Ultimately, the ceremonial centers were the architectural translation of the identity of each city, as represented by the veneration of their gods and masters.[citation needed] Stelae were common public monuments throughout Mesoamerica, and served to commemorate notable successes, events and dates associated with the rulers and nobility of the various sites.

Given that Mesoamerica was broken into numerous and diverse ecological niches, none of the societies that inhabited the area were self-sufficient.[citation needed] For this reason, from the last centuries of the Archaic period onward, regions compensated for the environmental inadequacies by specializing in the extraction of certain abundant natural resources and then trading them for necessary unavailable resources through established commercial trade networks.

The following is a list of some of the specialized resources traded from the various Mesoamerican sub-regions and environmental contexts:

Pacific lowlands: cotton and cochineal.

Maya lowlands and the Gulf Coast: cacao, vanilla, jaguar skins, birds and bird feathers (especially quetzal and macaw).

Central Mexico: Obsidian (Pachuca).

Guatemalan highlands: Obsidian (San Martin Jilotepeque, El Chayal, and Ixtepeque), pyrite, and jade from the Motagua River valley.

Coastal areas: salt, dry fish, shell, and dyes.

Agriculturally based people historically divide the year into four seasons. These included the two solstices and the two equinoxes, which could be thought of as the four "directional pillars" that support the year. These four times of the year were, and still are, important as they indicate seasonal changes that directly impact the lives of Mesoamerican agriculturalists. The Maya closely observed and duly recorded the seasonal markers. They prepared almanacs recording past and recent solar and lunar eclipses, the phases of the moon, the periods of Venus and Mars, the movements of various other planets, and conjunctions of celestial bodies.

These almanacs also made future predictions concerning celestial events. These tables are remarkably accurate, given the technology available, and indicate a significant level of knowledge among Maya astronomers. Among the many types of calendars the Maya maintained, the most important include a 260-day cycle, a 360-day cycle or 'year', a 365-day cycle or year, a lunar cycle, and a Venus cycle, which tracked the synodic period of Venus. Maya of the European contact period said that knowing the past aided in both understanding the present and predicting the future (Diego de Landa). The 260-day cycle was a calendar to govern agriculture, observe religious holidays, mark the movements of celestial bodies and memorialize public officials.

The 260-day cycle was also used for divination, and (like the Catholic calendar of saints) to name newborns. The names given to the days, months, and years in the Mesoamerican calendar came, for the most part, from animals, flowers, heavenly bodies, and cultural concepts that held symbolic significance in Mesoamerican culture. This calendar was used throughout the history of Mesoamerican by nearly every culture. Even today, several Maya groups in Guatemala, including the K'iche', Q'eqchi', Kaqchikel, and the Mixe people of Oaxaca continue using modernized forms of the Mesoamerican calendar.

One of the earliest examples of the Mesoamerican writing systems, the Epi-Olmec script on the La Mojarra Stela 1, is dated to around A.D. 150. Mesoamerica is one of the five places in the world where writing has developed independently. The Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are logosyllabic combining the use of logograms with a syllabary, and they are often called hieroglyphic scripts. Five or six different scripts have been documented in Mesoamerica, but archaeological dating methods, and a certain degree of self-interest, create difficulties in establishing priority and thus the forebear from which the others developed. The best documented and deciphered Mesoamerican writing system, and therefore the most widely known, is the classic Maya script.

Others include the Olmec, Zapotec, and Epi-Olmec/Isthmian writing systems. An extensive Mesoamerican literature has been conserved partly in indigenous scripts and partly in the postinvasion transcriptions into Latin script. The other glyphic writing systems of Mesoamerica, and their interpretation, have been subject to much debate. One important ongoing discussion regards whether non-Maya Mesoamerican texts can be considered examples of true writing or whether non-Maya Mesoamerican texts are best understood as pictographic conventions used to express ideas, specifically religious ones, but not representing the phonetics of the spoken language in which they were read.

Mesoamerican writing is found in several mediums, including large stone monuments such as stelae, carved directly onto architecture, carved or painted over stucco (e.g., murals), and on pottery. No Precolumbian Mesoamerican society is known to have had widespread literacy, and literacy was probably restricted to particular social classes, including scribes, painters, merchants, and the nobility. The Mesoamerican book was typically written with brush and colored inks on a paper prepared from the inner bark of the ficus amacus. The book consisted of a long strip of the prepared bark, which was folded like a screenfold to define individual pages. The pages were often covered and protected by elaborately carved book boards. Some books were composed of square pages while others were composed of rectangular pages.

Mesoamerican arithmetic treated numbers as having both literal and symbolic value, the result of the dualistic nature that characterized Mesoamerican ideology. The Mesoamerican numbering system was vigesimal (i.e., based on the number 20). In representing numbers, a series of bars and dots were employed. Dots had a value of one, and bars had a value of five. This type of arithmetic was combined with a symbolic numerology: '2' was related to origins, as all origins can be thought of as doubling; '3' was related to household fire; '4' was linked to the four corners of the universe; '5' expressed instability; '9' pertained to the underworld and the night; '13' was the number for light, '20' for abundance, and '400' for infinity. The concept of zero was also used, and its representation at the Late Preclassic occupation of Tres Zapotes is one of the earliest uses of zero in human history.

It was once said “Mesoamerica would deserve its place in the human pantheon if its inhabitants had only created maize, in terms of harvest weight the world's most important crop". But the inhabitants of Mexico and northern Central America also developed tomatoes, now basic to Italian cuisine; peppers, essential to Thai and Indian food; all the world's squashes (except for a few domesticated in the United States); and many of the beans on dinner plates around the world. One writer estimated that Indians developed three-fifths of the crops now grown in cultivation, most of them in Mesoamerica.

Having secured their food supply, the Mesoamerican societies turned to intellectual pursuits. In a millennium or less, a comparatively short time, they invented their own writing, astronomy and mathematics, including the zero. Maize played an important role in Mesoamerican Feasts due to its symbolic meaning and abundance. Fray Bernardino de Sahagún collected extensive information on plants, animals, soil types, among other matters from native informants in Book 11, The Earthly Things, of the twelve-volume General History of the Things of New Spain, known as the Florentine Codex, compiled in the third quarter of the sixteenth century. An earlier work, the Badianus Manuscript or Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis is another Aztec codex with written text and illustrations collected from the indigenous viewpoint.

The shared traits in Mesoamerican mythology are characterized by their common basis as a religion that, although in many Mesoamerican groups developed into complex polytheistic religious systems, retained some shamanistic elements. The great breadth of the Mesoamerican pantheon of deities is due to the incorporation of ideological and religious elements from the first primitive religion of Fire, Earth, Water and Nature. Astral divinities (the sun, stars, constellations, and Venus) were adopted and represented in anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, and anthropozoomorphic sculptures, and in day-to-day objects.

The qualities of these gods and their attributes changed with the passage of time and with cultural influences from other Mesoamerican groups. The gods are at once three: creator, preserver, and destroyer, and at the same time just one. An important characteristic of Mesoamerican religion was the dualism among the divine entities. The gods represented the confrontation between opposite poles: the positive, exemplified by light, the masculine, force, war, the sun, etc.; and the negative, exemplified by darkness, the feminine, repose, peace, the moon, etc.