|

|

British Campaigns

in

Africa and the Pacific

1914-1918

by

Edmund Dane

|

|

|

|

This is

the 1919 First Edition

This is an

excellent study of British Army operations in the little

known campaigns in Africa and the Pacific in World War I,

including South African operations in German South-West

Africa; British, Indian and South African operations in

German East Africa; British operations in Togoland and the

Cameroons in West Africa; plus the siege of Kiao-chau in

China and the South-West Pacific operations by the

Australians including Samoa, Bismarck Archipelago and New

Guinea.

From “War Books” by Cyril Falls: “Little has been written

about the majority of the campaigns here described, and

although Mr Dane had comparatively little material to work

upon, his account is not without value. He writes of

South-West Africa, East Africa, Togoland, the Cameroons, and

the Pacific, including the siege of Kiao-Chau.”

|

|

|

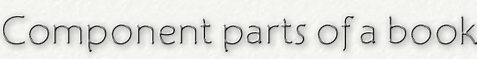

Front cover and spine

Further images of this book are

shown below

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher and place of

publication |

|

Dimensions in inches (to

the nearest quarter-inch) |

|

London: Hodder & Stoughton |

|

5½ inches wide x 8¾ inches tall |

| |

|

|

|

Edition |

|

Length |

|

1919 First Edition |

|

[xv] + 215 pages |

| |

|

|

|

Condition of covers |

|

Internal condition |

|

Original blue cloth blocked in gilt on the

spine. The covers are

rubbed with some patchy discolouration and evidence of old staining, which

is more evident on the rear cover |(on the front cover there is a small area

of patchy colour loss near the centre and darkening to the cloth around the

top corner). The spine ends are bumped quite heavily; the corners less so.

There are some indentations along the edges of the boards. |

|

The end-papers are browned and discoloured. The text is

generally very clean throughout on tanned paper, though a few pages are

slightly stained.

There is a previous owner's name inscribed in pencil on the front free

end-paper, which has been erased but not before leaving an impression; the

front free end-paper is also creased at the fore-edge. The edge of the text block is dust-stained and lightly foxed. |

| |

|

|

|

Dust-jacket present? |

|

Other

comments |

|

No |

|

Despite some wear to the covers, still a

pleasing example of the scarce First Edition. |

| |

|

|

|

Illustrations,

maps, etc |

|

Contents |

|

No illustrations are called

for; there are a number of maps; please see below for details |

|

Please see below for details |

| |

|

|

|

Post & shipping

information |

|

Payment options |

|

The packed weight is approximately

600 grams.

Full shipping/postage information is

provided in a panel

at the end of this listing.

|

|

Payment options

:

-

UK buyers: cheque (in

GBP), debit card, credit card (Visa, MasterCard but

not Amex), PayPal

-

International buyers: credit card

(Visa, MasterCard but not Amex), PayPal

Full payment information is provided in a

panel at the end of this listing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

British Campaigns in Africa

and the Pacific, 1914-1918

Contents

Chapter I

THE GERMANS IN SOUTH-WEST AFRICA

German declarations

on Colonial policy — The Berlin-Congo Conference, and the

Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference, 1890 — Annexation of

South-west Africa — Area and natural features of the Colony

— Its native races — The Hottentots — The Hereros — Their

pastoral civilization — The Ovembos — Origin of German

Interest In South-west Africa — The Rhenish Missions

Society's pioneers — Missioanry traders — The

Hottento-Hereros War — British Official Inquiry — Petition

of the Hereros for British Protectorate — British

Commissioner's recommendations — Reason for its refusal by

the Home Government — Walfish Bay — German Commercial

projects — Luderitz as prospector — German annexation of

Angra Pequena — Negotiations with native chiefs — Jordaan's

Boer Republic — German measures against it — Attempts to

drive out British traders — Robert Lewis — German

administration expelled from Damaraland — German Government

and the demand for armed intervention — Native attitude in

1890 — The real lines of German policy — Increase of German

garrison — Provocation of natives — The massacre at

Hornkrantz — German Land Settlement Syndicate — Confiscation

of Herero cattle — The German credit system — German Courts

of Justice — Spoliation of the natives — Fear of

Hottentot-Herero Confederacy — seiziure and execution of

Herero chiefs — Outbreak of the Hottentot War — Jacob

Marengo — The Herero Rebellion — Arrival of General von

Trotha — His campaign of extermination — Unrestrained

atrocities — Valour of the Hereros — Germen vengeance

towards survivors — Gross abuses of the lash and

indiscriminate executions — Establishment of chattel slavery

— German difficulties in Hottentot campaign — Heroic end of

Hendrik Whitbooi — Von Trotha recalled — Extermination

policy given up — Miserable state of the country.

Chapter II

GENERAL BOTHA'S CAMPAIGN : FIRST PHASE

Position on

outbreak of war, 1914 — German views on South African

prospects — The forces of the South African Union — Reasons

for and against campaign in South-west Africa — Ambitions of

German Colonial enterprise — Military character of German

Government in Southwest Africa — Its heavy armament —

Ultimate purpose and menace — The strategical railways —

Meaning of the terrorism towards natives — Shades of opinion

in South African Union — Botha's policy — Its foundation —

Decision in favour of war — Botha's plan of campaign — Why

original and bold — Main attack from the Sea — German plan

for counter-offensive — The opening moves — Lukin's

Expedition to Little Namaqualand — Union forces take

Luderitzbucht — Preparations for overland advance — Lukin's

operations from Steinkog — Defection of Maritz — Effect on

Lukin's Expedition — The reverse at Sandfontein — Rising of

Beyers and de Wet — Influence of political events on the

campaign — Descent at Walfish Bay postponed and M'Kenzie's

column diverted to Luderitzbucht — M'Kenzie's advance to

Tschaukab — Conquering the difficulties of the coastal

desert — Fine work of the engineers — Sir George Farrar's

services and death by accident — Check to German

counter-offensive — Landing of Skinner's Column at Walfish

Bay — Capture of Swakopmund — German use of Land-mines —

Poisoning of water supplies — Botha's warning to the enemy —

Native service to Union forces — Union overland operations

re-organised — The new scheme — Germans and Marko attack and

capture Nous and Britstown — Bouwer retakes Raman's Drift —

The Kalahari Desert Column — German attack upon Upington —

Its defeat — Surrender of Kemp — Fate of Maritz — German

repulse at Kakamas — Failure of their offensive.

Chapter III

GENERAL BOTHA'S CAMPAIGN SECOND PHASE

Botha takes active

command — His visit to the camp at Tschaukab — Arrival at

Swakopmund — Disembarkation of Burgher Brigades —

Preparations for the main advance — The water problem —

Botha's consequent change of plan — Concealment of the

change — M'Kenzie's move on Garub — Gen. Deventer's advance

from Upington — Takes Nakob, and fSchuit'sDrift — Capture of

German camp at Nabas — Berrange's advance from Kuruman —

Romantic character of the adventure — Defeat of the Germans

at Schaapkolk — And at Hasuur — Berrange's objective — Botha

attacks German defences in Swakop Valley — His tactics —

Their complete success — Progress of the overland operations

— Col. Dirk van Deventer's flank guard movement — His

successes at Davignab, Plattbeen, and Geitsaub — Junction

with Berwage at Kiriis West — M'Kenzie's advance to Aus —

Germans pinched out of Kalkfontein — Importance of this

result — convergence of Union forces from the South — Smuts

takes command — His move to Keetmanshoop — German retreat to

Gibeon — M'Kenzie's dash from Aus to Gibeon — The action at

that place — M'Kenzie's tactics — Botha anticipates enemy

concentration — His drive to Dorstriviermund — German

counter-move — Checked by Skinner at Trekkopjes — Botha cuts

the railway to Windhuk — Dash to Karibib — German forces

divided up — Flight of German administration and surrender

of Windhuk — Botha grants an Armistice — Impossible German

propositions — The Campaign resumed — The German position —

Botha's better estimate and revised dispositions — Karibib

as a new base — Plan of the Union advance — The flanking

operations — Germans refuse battle — Record marching of

Union forces — The drive to Otavi — Germans fall back

towards Tsumeb, their final position — Demand for surrender

agreed to — Declaration of local armistice — Reason for the

precaution — Myburgh captures arsenal at Tsumeb — Last

outlet closed by Brits at Namutoni — Botha's terms — Their

true meaning — End of German rule a South-west Africa —

Benefits of the new regime

Chapter IV

THE STORY OF EAST AFRICA

Natural features

and climate of East Africa — Its native communities and

kingdoms — Trade routes — First German prospectors — Slave

trade agitation begun — Charter granted to 1erman

Colonisation Society — British Protectorate declared aver

Zanzibar — Germany and the Sultanate of Witu —

British-German diplomatic duel — Hinterland parcelled out

into spheres of influence — British East African Chartered

Company — Germans demand port of Lamu — Attack on German

traders — Agreement of 1890 — British and German antagonism

in Uganda — German intrigues in the Soudan — Germany's East

African administration — The commercial monopoly —

Plantation labour difficulties — Formation of a native

standing army — Its relationship with native tribes —

studied hostility — Measures for forcing natives into

plantation labour — Tyranny of German police — Abuses of

convict system — Native revolt in 1904 — The Native War of

1905-6 — The "Magic Water" legend — Destruction of the

Wamwera nation — Treatment of native leaders.

Chapter V

EAST AFRICAN CAMPAIGN 1914-1916

German readiness —

Propaganda in the Eastern Soudan — Supremacy on the Great

Lakes — Von Lettow-Vorbeck — His leadership — plans for

offensive — British attack on Dar-es-Salem — Konigsberg's

attack on Zanzibar — British campaign dependent on the sea —

German invasion of British East Africa — Its initial success

— Thrusts at Mombasa — Landing of British reinforcements

from India — The counter-offensive — Attack on Tanga fails —

British non-success at Longido — The combat at Tanga —

Arrival of General Tighe — Von Wehle'e operations against

Kisumu and Uganda — Invasion of Uganda repulsed — General

Stewart 's expedition to Bukoba — The operations in

Nyassaland — Defeat of German Expeditionary force — Invasion

of Rhodesia — German raid on Kituta — The British Tanganyika

Naval Expedition — Its romantic overland adventures —

Destruction of German flotilla — Siege of Saisi — Episodes

of the defence — Revolt of the Sultan of Darfur — Col.

Kelly's Expedition from El Obeid — His remarkable march —

Battle of Beringia — Occupation of Darfur.

Chapter VI

THE CAMPAIGN OF GENERAL SMUTS: FIRST PHASE

The situation in

February, 1916 — Strength of German forces — The German

positions round Taveta — Reorganisation of the British

Divisions — Tighe's plan of a converging attack — Capture of

German defences at Mbuyuni and Serengeti — The water supply

problem — Reinforcement from South Africa — Dispositions of

General Smuts for the battle of Kilimanjaro — Stewart's

turning movement — Van Deventer breaks through German line —

Capture of Taveta — A rapid and sweeping victory — German

retreat upon Latema-Reata pass —Struggle for the defile —

Germans fall back upon Kahe — Importance of the position —

Again won by turning movement — Action in the Valley —

German retreat to Lembeni — The rainy season — Smuts

re-groups his forces — His new plans — Van Deventer's

seizure of Loikissale — German intentions disclosed —

Expedition of van Deventer to Kandoa Irangi — Battle of

Kandoa Irangi and defeat of yon Lettow-Vorbeck — Its

influence on the Campaign — Smuts advances south from Kahe —

Germans squeezed out of Usambara highlands —Action at

Mikotscheni — Capture of Handeni — Battle on the Lukigura

river — Belgian troops invade Ruanda — British attack and

occupy Mwanza — End of this phase of the campaign.

Chapter VII

EAST AFRICAN CAMPAIGN : THE CLOSING PHASES

Fighting value of

the German forces — Enemy concentration in Nguru mountains —

Van Deventer's dash from Kandoa Irangi — Action at Tschenene

— Railways from Tabora cut — Northey's advance from Rhodesia

— Belgians take Ujiji and Kilgoma — Operations of Smuts in

the Nguru mountains — Battle at Davaka — Enemy's

preparations in the Uluguru mountains — Review of the

situation — Van Deventer's march to Kilossa —Plans to entrap

enemy in Uluguru area — Reasons for their failure — British

check at Kissaki — Exhauistion of the comatants — Germans

fall back towards Mahenge — Capture of Dar-es-Salem —

Belgians take Tabora — Northey's advance — Actions at New

Iringa and on the Ruhuje — Germans attack Lupembe —

Surrender of German force at Itembule — End of the second

phase of General Smut's campaign — Further reorganisation of

his force — Increase of black troops — The new British

dispositions — Von Lettow-Vorbeck's counter-plan — Germans

attack Malangali — Their defeat at Lupembe — British

operations at Kilwa — Battle of Kibata — New plan for

enclosing movement — Tactical disguises — Battle at Dutumi —

Crossing of Rufigi seized — Operations on the Rufigi — Smuts

relinquishes his command — German food difficulties — Van

Deventer succeeds Hoskins — Van Deventer's strategy — Von

Lettow-Vorbeck forced to fight —Battle at Narongombe —

Mahungo captured — Battle of the Lukulede —Heavy German

losses — Germans defeated at Mahenge — Surrender of Tafel's

column — End of the Campaign.

Chapter VIII

THE CAMPAIGN IN TOGOLAND

German annexation

of the Colony — Its native population — German labour policy

— Economic effects — Military weakness of the German

position — Place of Togoland in German Imperial Scheme —

Proposal of Neutrality — Why rejected — The Anglo-French

invasion — German retirement inland — Battle on the Chra —

Position turned by the French — German surrender at Kamina —

End of the Campaign.

Chapter IX

THE CAMPAIGN IN THE CAMEROONS

Features of the

African Campaigns — Character of the Cameroons — The German

military scheme — The fortified frontier — British attack

from Nigeria — Its failure and the reasons — The reverses at

Gaura and Nsanakang — General Dobell's plan of invasion from

Duala — Effect of the French attack — German precautions at

Duala — The British naval operations — Dobell's expedition

to and capture of Duala and Bonaberi — Germans forestalled —

British operations against Jabassi and Edea — Clearance of

the Northern railway — German rebound — Actions at Edea and

Nkongsamba — German commander's projects — The French

advance — Battle at Dume — Allied operations at a halt —

General Dobell's view of the position — The French plan for

a combined movement against Jaunde — British and French

advance from Duala — Battle at Wum Biagas — Failure of the

project — French advance to Dume and Lome — Resumption of

the attack from Nigeria — Siege and capture of Garua —

Breach of the German military barrier in the north — The

siege of Mora — Second Allied Conference at Duala — New

plans — Nigerian forces link up with those of Dobell — The

final converging moves — Resumed British move from Duala

inland — Battle at Lesogs — Siege and capture of Banyo — The

final dash to Jaune — German retreat to Rio Muni — Surrender

of Mora.

Chapter X

THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC AND THE SIEGE OF KIAO-CHAU

German policy in

the Far East — Aims of German diplomacy — Basis and effects

of German naval power — The British and Japanese

counter-moves — Growth of German interests in the Pacific —

Influence of Japanese and Australian naval preparations —

The New Zealand Expedition to the Samoan Islands —

Australian conquest of the Bismarck Archipelago and Kaiser

Wilhelm Land — Japanese Pacific Expedition — The Germans in

Kiao-Chau — Character and strength of its fortifications —

Germany's "lone hand" in the Far East — Japan's declaration

of War — Preparations for the siege of Kiao-Chan — Landing

of the Japanese advance forces — The British contingent —

General Kamio's first move — Skill of Japanese operations —

Capture of the outer defences — The attack on the inner

defences — A record bombardment — The three parallels of

approach — Last stage of the attack — Surrender of the

garrison.

Maps

German South-West Africa

Operations on the Orange River

The Advance of of General Botha from Swakopmund

The Southern Concentration of the South African Union Forces

The Operations in German East Africa

British Manoeuvres in the Battle of Taveta

Operations in the Nguru Mountains

The Campaign in the Cameroons

The German Defences at Kiao-Chau

|

|

|

|

|

British Campaigns in Africa

and the Pacific, 1914-1918

Preface

The Campaigns in Africa have an

interest of their own. They present aspects of the Great War

associated with varied, and often strange, adventure. And as

illustrations of military resource and skill they well repay study.

In order that they may be the better understood, a succinct account

has been given of German colonial policy and dealings. Some of the

facts may appear incredible. There is, however, not one that is not

based upon well-tested proof. German rule in Africa portended a

revival of chattel slavery upon a great scale, and had the

contemplated German Empire in Africa been established the desolating

social phenomenon of chattel slavery could not have been confined to

the so-called "Dark Continent." Happily, in the campaigns in Africa

the evil was rooted up. The effect of thee campaigns on the world's

future will be deep.

Both the causes of military operations and the character of the

terrain over which they take place have to be presented clearly to

the reader's mind before they can be followed with ease. Often

military events have been dealt with as a kind of poetic history, or

in the dry technical manner which, save to those with expert

knowledge, is repellent. There is no reason why they should not be

narrated at once truthfully and lucidly. That attempt, at any rate,

has here been made. Finally, the relations of these campaigns to

each other and to the Great War as a whole have been touched upon as

far as necessary.

E. D.

London, May 1919

|

|

|

|

|

British Campaigns in Africa

and the Pacific, 1914-1918

Excerpt:

. . . General Smuts was now

about to begin his drive towards the south. As a preliminary Van

Deventer pushed on to Moschi, and apart from brushes of his vanguard

with parties of enemy riflemen, he entered the place unopposed.

Moschi, the centre of the British- Dutch settlement round

Kilimanjaro, is a town of some importance, and about thirty miles

within the German boundary. Since it was both the terminus of the

railway from Tanga via Wilhelmstal, and the meeting point of several

main roads, it was a jumping-off position of the highest value. At

New Moschi, on the road to the west, Stewart's Column joined up.

While his advance parties were reconnoitring the positions taken up

by von Lettow-Vorbeck's forces at Kahe and along the Pangani (or

Ruwu) river, the British commander, with Moschi as his new base, at

once got to work upon preparations for his movement. The chase, if

it was to be effective, must be a long- winded chase. Risk of

breakdown could not be taken. The road from Taveta to Moschi had to

be repaired and improved : transport overhauled and reorganised ;

supplies brought forward. Time was of consequence, because it was of

no slight moment to drive the enemy across the Pangani before the

coming of the rains. Unless that were done, the task of dislodging

him would be difficult.

The key of the Pangani position was Kahe. Between Kilimanjaro and

the Usambara plateau on the coast there is, running north to south,

a long rib of rising land which at its highest point — the Pare

Mountains — is more than 2,000 feet above sea-level. To the east of

it lies the Umba valley and the dry country of Taveta ; to the west,

the Pangani valley. The main road from Moschi to Tanga had been

constructed along the westward slope of this rib, and below the road

in the valley, following an almost parallel track, ran the railway.

Kahe, on the main road at the upper end of the Pangani valley,

occupied a hump jutting out from the ridge, and terminating in a

bold, and apparently isolated, summit. The place was a natural

fortress, and the enemy had turned it to the best account. To attack

it in the ordinary way would have been a costly and uncertain

operation. In the attack, however, General Smuts followed his

characteristic South African tactics. There was a frontal advance

from Moschi initiated on the 18th under the command of General

Sheppard with the mounted troops of the 1st Division, supported by

mountain guns and some field pieces. The advance was sharply

resisted, and three battalions of the 2nd South African Brigade were

detailed to stiffen it. On the 18th and 19th this action went on,

and to all appearances the attack made very little impression. But

on March 20, the enemy being thus busily occupied, and probably

pluming himself on his defence, Van Deventer moved out of Moschi

with the 1st South African Mounted Brigade, the 4th South African

Horse, and two batteries of guns ; struck south-west, wheeled to the

east ; crossed the river ; and while the enemy was busy with a night

attack upon Sheppard's camp got astride the railway and the road.

Then, moving up the valley, he boldly made for Kahe hill, driving in

the rear and flank guards opposed to him. By this time, however, the

enemy had taken the alarm, and Kahe had been hastily evacuated. Thus

by skilful manoeuvring the Germans had in rapid succession been

squeezed out of two important and naturally strong positions.

Here appeared a counter-stratagem on the part of the German general

which more than once turned up in the course of the campaign. It

might have been supposed that his force would have fallen back

towards the east across the rise, or moved along it towards the

south. Either of those moves, however, would have entrapped them.

What they in fact did was to strike to the west, slipping out

through the gap between Van Deventer's force and that of Sheppard.

To cover this movement and give their main body a better start, they

sent back a contingent ostensibly to retake Kahe, as though its

abandonment had been a mistake.

Farther down the Pangani valley they took up a strong position

between the Soko Nassai and Defu rivers, two of the Pangani's

tributaries. Those streams covered the enemy's flanks. Along the

front of his line there was a clearing in the bush varying in

breadth from 600 to 1,200 yards. To attack him at close quarters

this space had to be crossed. But as his forces were hidden in the

high thick undergrowth on the farther side, the crossing was a

ticklish proposition. Moving out on March 21 to clear the valley,

Sheppard was brought up against this obstruction. His plan was to

turn the right of the German line. It was found, however, that the

bush there was too dense to traverse, and with the exception of two

companies of the 129th Baluchis who crossed the Soko Nassai, the

troops told off for this part of the work never got into the fight

at all. In the circumstances a frontal attack was essayed. The

effort was gallantly made, and it was well supported by the

artillery, but it failed. Proofs were afterwards forthcoming that

the enemy's losses had been severe, but those on the British side

were 288, more than in the fight for the Latema-Reata pass. That

night Sheppard's men dug in. At dawn it was intended to renew the

assault, and patrols stole forward to reconnoitre. They found the

German lines and trenches deserted. In the night von Lettow-Vorbeck

had crossed the Pangani moving towards Lembeni.

Of two 4.1 -inch naval guns he had used in the battle, one mounted

on a railway truck manoeuvred up and down the line, and the other in

a fixed position, the latter had been left behind. It was evident

from this action that European tactics were little suited to

operations in a country where the wild growth is six to ten feet in

height. At the same time, the important work of driving the enemy

across the Pangani had been rapidly accomplished, and the price paid

cannot be considered high. A chain of British posts was established

along the river, and the preparations pushed on for continuing the

campaign.

April and May are in this part of Africa the rainy months, and in

this season of 1916 the rains happened to be above the average

heavy. They are heaviest in any season in the mountain area round

Kilimanjaro. For nearly six weeks, once the weather broke, the

downpour continued day after day, the fall within twenty-four hours

sometimes equalling four inches. When that occurs the country is

flooded out ; roads waist deep in water ; the rivers and streams

roaring and impassable torrents.

Under these conditions nothing could be done. All the same, General

Smuts wasted no time. His force was increased by the 2nd South

African Mounted Brigade, and he now took advantage of the rainy

interval to reorganise. As he has himself stated, he was in command

of a most heterogeneous army, got together from all quarters,

contingent by contingent, and speaking a Babel of languages. By

comparison, the enemy troops, though fewer in number, presented a

unity alike in composition and in training. To tighten up the

structure of the British field force was not merely advisable ; it

was essential. In the meantime, too, there had arrived from Capetown

Generals Brits, Manie Botha, and Berrange. With those experienced

officers also at his disposition, the Commander-in-Chief was able to

form a striking force of three divisions, consisting in part of

South Africans, mounted and foot, in part of native regiments

recruited in British East Africa. These troops were the most

acclimatised. None others, it was clear, could long stand the strain

of swift campaigning in such a region. Accordingly, the British and

Indian units were held in reserve. They had already gone through

more than a year of the war, some a year and a half. The climate of

East Africa exacts a heavier toll than battles. As re-shaped, the

new divisions of manoeuvre were : —

1st Division (Major-General A. R. Hoskins) comprising the 1st East

African Brigade (Sheppard) and the 2nd East African Brigade

(Brigadier-General J. A. Hannyngton).

2nd Division (Van Deventer) comprising the 1st South African Mounted

Brigade (Manie Botha), and the 3rd South African Infantry Brigade (Berrange).

3rd Division (Brits) comprising the 2nd South African Mounted

Brigade (Brigadier-General B. Enslin), and the 2nd South African

Infantry Brigade (Beves).

The main body of the enemy had by this time fallen back south upon

and were passing the wet season in the Pare Mountains, and that fact

had a certain influence on the decision of General Smuts as to the

strategy to be followed. The German recruiting ground lay west of

the main mountain range, for in other parts of the colony the

natives were at best passively hostile, and von Lettow-Vorbeck drew

the larger part of his supplies from the same inland area, through

Tabora, a place west of the mountains and on the Dar-es-Salem —

Ujiji railway. If, then, the German commander, while keeping open

his communications with Tabora, could retain his hold on the Pare

Mountains and the Usambara plateau, a most difficult triangle of

country, he had a chance of carrying on the campaign in a manner

calculated at once to conserve his own resources and to waste those

of the attack. Further, if to cripple him the British detached any

considerable force to seize Tabora, moving it up to Kisumu, and

across the Victoria Nyanza, to avoid the mountain barrier, he had

the reply of a threat against Mombasa.

General Smuts inferred that the retreat of the hostile main body

upon the Pare range had been made with these ideas in view.

Weighing, therefore, and rejecting possible alternatives, he decided

first to strike at the Tabora line of communication directly across

country from Moschi. That move on his part, he had no doubt, would

have the effect of detaching a strong contingent from the German

main force, and, assuming that it had, he could then, with very

slight risk, thrust south along the lower course of the Pangani, cut

in between the two enemy bodies, and either isolate those on the

Usambara heights or squeeze them out. It was a simple, bold, and

practicable plan, and at the earliest moment after the rains, and on

the first indication that the country was again becoming

traversable, he put it into execution.

Before the wet season Arusha, seventy miles west of Moschi, had

fallen into his hands, and Van Deventer with the 2nd Division was

now there. The Germans had at the beginning of April a force at

Lokissale, thirty- five miles south-west of Arusha. Their position

commanding the road into the centre of the colony from Arusha was a

mountain nearly 7,000 feet high, and it was important, because on it

were the only springs of water in the area. The road from Arusha

here runs with the mountains on one side, and the Masai tableland on

the other, and it is a lonely upland region. Likely enough, the

Germans at Lokissale did not think they would be disturbed until

after the rains, but on the evening of April 3, Van Deventer, with

three regiments of his mounted men, dashed out of Arusha, and, after

a night ride, was next morning before the enemy stronghold. Covered

by the mists, he surrounded it. The Germans and their auxiliaries

resisted with determination, for the position was vital. All that

day and the next they held out. On the 6th, however, the whole

force, 17 white and 404 askari combatants, with their commander,

Kaempf, laid down their arms. Their stores, ammunition, pack animals

and machine-guns fell into Van Deventer's hands, and a body of

native porters and camp followers were obtained at the same time.

But not less valuable than the captures was the information gleaned

from Kaempf's papers. It was learned that von Lettow-Vorbeck, in

order to close this route, was taking steps to reinforce his

garrisons at Ufiome, Kandoa Irangi, and other places on the western

edge of the Masai steppe, and that meanwhile these garrisons had

received orders, which were also the orders of Kaempf, to hold out,

if attacked, as long as possible. This information at once confirmed

the British Commander-in-Chief's inference, and his instant

resolution was to seize Ufiome, Umbulu, and Kandoa Irangi before the

enemy could reinforce. On April 7, accordingly, Van Deventer pushed

on to the first of these three places. The enemy, 20 whites and 200

askaris, were found occupying a ridge. They were defeated and driven

west into the mountains. All the supplies at Ufiome, and they were

large, were secured. In the interim the infantry of Van Deventer's

Division had been following up, and a contingent took over the

captured position. Some slight delay now arose owing to the

exhaustion of the horses, but the move was as soon as possible

resumed, and on April 11 Umbulu was taken. At Kandoa Irangi, one of

the most important road centres in the colony, the Germans had a

powerful wireless installation. On the approach of Van Deventer's

mounted men, on April 17, the garrison, a considerable force, came

out into the open and advanced four miles to the north. The fight

went on for two days. By the end of that time Van Deventer had so

manoeuvred as to thrust part of his force between the defence lines

and the town, and having edged the garrison out of it and beaten

them, he took it without further opposition. The captures here

included 800 head of cattle.

How remarkable a feat this dash was may be inferred from the fact

that Kandoa Irangi is distant from Arusha 120 miles, and the daring

of the move may be gathered from the further fact that, owing to the

rains, Van Deventer and his men were for several weeks entirely cut

off from communication with Moschi, and had to live on supplies

collected on the spot, supplemented by such provisions as could be

carried across the country from Arusha by native porters.

On the campaign, however, the move had an influence beyond estimate.

No sooner had the news of it reached him than von Lettow-Vorbeck,

realising what it implied, hurried from Usambara at the head of

4,000 men. He had already, in the defeat and dispersal of his

garrisons, had his total strength lessened by some 2,000 combatants.

Rain or no rain therefore, partly by road, partly by railway, he

pressed on, collecting another 1,000 men en route. From Kilimatinde,

the nearest point on the central railway, Kandoa Irangi is distant

about eighty miles. That final lap was covered by rapid marches, and

on May 7 he arrived. Whether he still hoped to find Kandoa Irangi

holding out is uncertain, but what is quite certain is that he had

resolved to attack before Van Deventer's Division could be

reinforced, and inflict a crushing defeat upon it. Owing to sickness

and fatigue, the South African commander could not now muster more

than 3,000 effectives fit for duty. In the circumstances, and

looking at his isolated position, he stood upon the defensive. Von

Lettow-Vorbeck gave his own troops, twenty-five double companies,

two days' rest. Then he attacked, and the attack was desperate. Four

times the askaris, urged on by their German officers, stormed up to

the South African trenches, and four times they were beaten off. The

enemy's bravery was almost fanatical. But against the shooting of

the defending force it was of no avail. While by no means

indifferent shots, for their German instructors had taken every

pains to make them efficient, the askaris were not a match for

troops who, as marksmen, have no superiors in the world. Their

losses, which were heavy, included von Kornatsky, a battalion

commander, killed, and another battalion commander, von Bock,

wounded. Nothing could better indicate the character of this

struggle. The battle continued all day and far into the night. In

the early hours of the morning, and well before daybreak, von

Lettow-Vorbeck and his shattered force withdrew. His next move was

to try to starve Van Deventer out by ranging, before the heaviest

rains came on, over the surrounding country, one of the most fertile

and healthy parts of East Africa. That procedure, however, did not

succeed, and before long he had serious events elsewhere to claim

his attention.

The moment he had news of the enemy's defeat at Kandoa Irangi,

General Smuts hurried forward the movement which on his side was to

form its sequel. There was the possibility that von Lettow-Vorbeck

might, to save time, march back to Handeni, across the Masai steppe

by the old caravan route, and if the intended British movement down

the Pangani were thus forestalled it would find itself confronted by

the reunited German main body. To cross the steppe to Handeni is,

for infantry, a twelve days' march. It was imperative, therefore,

that the British divisions at Kahe should move out on the earliest

date on which transport became feasible. The rains continued to fall

until nearly the middle of May, but as usual towards the end of the

wet season, they became lighter, and by degrees the sun reasserted

its power. From Kahe to Handeni is, roughly, the same distance as

from Kandoa Irangi, but the British forces had by far the more

difficult stretch of country to negotiate. Besides, there were still

in the Pare and Usambara area enough enemy troops to put up a

serious delaying opposition. Everything, then, turned upon the

length of time at the start.

The advance began on May 18. The main column (Sheppard and Beves)

followed the road from Kahe southwards. With it was most of the

artillery and the transport. Slightly to the rear of its leading

formation marched, on the parallel route along the railway, a

smaller flanking column (Hannyngton). A second flanking column (Col.

T. O. Fitzgerald) set out from Mbuyuni, and crossing the ridge south

of Kilimanjaro by the Ngulu pass, joined the main column at the Pare

Mountains. The main column thus went forward covered on both flanks,

a disposition which contributed to rapid movement. General Smuts was

himself in command, Hoskins assisting.

The enemy had taken up a position at Lembeni, chosen because at that

point the railway runs close under the hills. But General Smuts had

no intention of wasting time and men in a frontal attack upon

fortified lines, much less upon lines affording every advantage to

the defence and none to the assault. He was aware that even should

Fitzgerald's movement not have the effect of compelling an

evacuation, the movement of Hannyngton, who had turned off and was

moving down the Pangani west of the railway, assuredly would. And

the calculation proved exact. The enemy, finding that his retreat

was threatened, abandoned Lembeni without waiting for the firing of

a shot. To cut him off from the TJsambara plateau, Hannyngton was

sent across the hills with orders to double back through the Gonja

Gap, a broad defile dividing off the Pare Mountains from the

plateau. This move entirely succeeded. Hannyngton reached the Gap —

it was a fine marching feat — and seized the bridge over the Mkomasi

river, barring hostile retirement in that direction.

The Gap closed, the German force, headed off the TJsambara plateau,

had no choice save to go on falling back down the Pangani valley,

and their next stand was at Mikotscheni, a position very like that

at Lembeni. On this occasion they waited for a fight, and the

frontal assault they had expected was duly delivered by the 2nd

Rhodesians. Is it necessary to add that it was not the real thing ?

The real thing was a movement by Sheppard's Brigade. Turning to the

left a slight way up the Gonja Gap, the Brigade swarmed up on to and

carried the bluff overlooking and commanding the enemy's lines. To

have retired now would have been disastrous, and rather shrewdly the

German commander fought on, though outflanked, until past nightfall.

Then as quietly as possible, he moved once more. The move was to

Mombo station, connected with Handeni by a trolley line. Along this

line the enemy marched to Mkalamo, where they entrenched.

So far they had been unmercifully hustled, for the distance from

Lembeni to Handeni is a good hundred miles, and it had had to be

covered in little more than a week, the fight at Mikotscheni

included. In fact, in ten days the British force had advanced 130

miles, and that, too, in face of opposition and over a country

which, with the exception of the route along the Pangani, was

roadless. In bridge building and bridge repairing the engineers

surpassed themselves.

Handeni, when reconnoitred, was found to be strongly fortified. Upon

that position, after a sharp action in which they had been driven

from their entrenchments at Mkalami by the 1st East African Brigade

and had suffered serious loss, the enemy force had concentrated. In

the meantime, having occupied Wilhelmstal and secured that place,

Hannyngton had marched south through Mombo. His arrival made it

practicable to detach Sheppard's Brigade for a characteristic

manoeuvre. On the east side, that is, between the plateau and the

coastal belt, the Masai steppe is fringed by mountains just as it is

on the west. The light railway from Mombo to Handeni ran along the

inner, or highland side of the hills, and the Handeni position was

close to and commanded a gorge through which flows seaward the

Msangasi river. The Handeni position itself was a bold, and nearly

isolated bluff, over 2,000 feet high. Its slopes had been scored

into tiers of trenches. Here, therefore, the enemy not only

obstructed the way south, but was safe against any attempt to turn

him by a movement along and from the coast. But that was not the

British commander's intention. What he did was to send Sheppard to

the west. Crossing the Msangasi higher up, Sheppard struck south,

and next day was at Pongwe, on the German line of retreat. A strong

detachment with quick-firing guns were found holding the place.

Sheppard attacked, drove them out, and scattered them through the

bush, where one of their pom- poms, left behind, was picked up. This

done, he doubled back towards Handeni. The hostile force there had,

however, already evacuated the stronghold. They had split up, some

retreating through the gorge, some across the hills, the rest

westward over the plateau.

As it was certain that they meant to reassemble farther to the

south, Fitzgerald with the 5th South Africans was sent in pursuit by

way of Pongwe. He was to occupy Kangata, eight miles beyond that

place. And at Kangata he butted into the new concentration. It had

taken place there because Kangata was at the northern end of a main

road which the Germans had recently constructed from Morogoro on

their Central Railway. This road, though still unfinished, had been

completed for eighty miles to the north from Morogoro, cutting

transversely across the Nguru mountains. Round Kangata the bush is

thick, and the enemy was entirely hidden in it, and but for the

vigilance of the South African scouting Fitzgerald would have been

ambushed. Greatly outnumbered, he lost heavily, but the effort to

drive him off proved futile, and he held on until the main British

Column came up.

The next obstacle was the Lukigura river. There the enemy held the

bridge on which the new road had been carried over the stream, and

as the Lukigura is rapid, tumbling seaward from the steppe through

the mountains, and between precipitous banks, this was again a tough

little problem. Round the north end of the bridge there was laid out

an arc of defences. General Smuts, however, had again thought out

his turning tactics. In the night Hoskins set out with two

battalions of South Africans, and a composite battalion made up of

Kashmiri Imperial Service Infantry, and companies of the 25th Royal

Fusiliers, and a body of mounted scouts ; followed the course of the

Lukigura upstream ; found a crossing ; passed over ; and was next

morning, after a rough march through the hills, on the new road to

the rear of the hostile position. Preconcerted signals having shown

that the manoeuvre had been brought off, Sheppard with both East

African Brigades began a frontal attack, and it was in progress when

Hoskins debouched on the enemy's rear. The enemy was now surrounded

on three sides, and but for the bluffs, densely overgrown with

scrub, would have been surrounded altogether. He no longer stood on

ceremony, but breaking up, his now usual resource when in a tight

place, made his way in parties through the jungle of grass and giant

weeds. Much of his ammunition, and machine-gun and other equipment

had, however, to be left behind, and a good proportion of his force

was captured.

In every sense the drive south from Kahe had been extraordinary, and

the more it is studied in detail the more remarkable it appears.

There were not only the actual difficulties of such an advance in

such a country ; there was the necessity of dealing with guerilla

tactics in the rear. When the Germans found that direct effective

resistance was out of the question, they laid themselves out to

hamper the transit of supplies, remounts, and munitions. Bands of

snipers infested the country, and skirmishes with convoys were of

daily occurrence. All this had to be systematically dealt with and

put down, and apparently innocent non-combatants of German

nationality rounded up. On the coast, from Tanga as far south as

Bagamoyo, the occupation of the ports was effected by landing

parties from the ships of the blockading squadron. Meanwhile, in

view of the distance to Moschi, the Lukigura represented for the

present the limit of the advance. Th. problem of supply had been

stretched to its utmost. The advanced base must be moved from Moschi

farther to the south and the line of communication thoroughly

secured. So far indeed had the supply problem been stretched, added

to guerilla obstruction, that on the march from the Pangani the

troops had lived upon half-rations. Not infrequently, also, they had

had to face shortage of water. All this was wearing, and the

percentage of sickness had become high. Had it not been for the wise

prevision which had reserved ample force to deal with irregular

attacks in the rear, the movement would have been held up. In any

event, the time had come before going farther to reorganise, rest,

and refit. Hence just south of the Lukigura, General Smuts laid out

a standing camp sufficient for his whole force, and proceeded to

overhaul his arrangements.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please note: to avoid opening the book out, with the

risk of damaging the spine, some of the pages were slightly raised on the

inner edge when being scanned, which has resulted in some blurring to the

text and a

shadow on the inside edge of the final images. Colour reproduction is shown

as accurately as possible but please be aware that some colours

are difficult to scan and may result in a slight variation from

the colour shown below to the actual colour.

In line with eBay guidelines on picture sizes, some of the illustrations may

be shown enlarged for greater detail and clarity.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U.K. buyers:

|

To estimate the

“packed

weight” each book is first weighed and then

an additional amount of 150 grams is added to allow for the packaging

material (all

books are securely wrapped and posted in a cardboard book-mailer).

The weight of the book and packaging is then rounded up to the

nearest hundred grams to arrive at the postage figure. I make no charge for packaging materials and

do not seek to profit

from postage and packaging. Postage can be combined for multiple purchases. |

Packed weight of this item : approximately 600 grams

|

Postage and payment options to U.K. addresses: |

-

Details of the various postage options can be obtained by selecting

the “Postage and payments” option at the head of this

listing (above).

-

Payment can be made by: debit card, credit

card (Visa or MasterCard, but not Amex), cheque (payable to

"G Miller", please), or PayPal.

-

Please contact me with name,

address and payment details within seven days of the end of the

listing;

otherwise I reserve the right to cancel the sale and re-list the item.

-

Finally, this should be an

enjoyable experience for both the buyer and seller and I hope

you will find me very easy to deal with. If you have a question

or query about any aspect (postage, payment, delivery options

and so on), please do not hesitate to contact me.

|

|

|

|

|

International

buyers:

|

To estimate the

“packed

weight” each book is first weighed and then

an additional amount of 150 grams is added to allow for the packaging

material (all

books are securely wrapped and posted in a cardboard book-mailer).

The weight of the book and packaging is then rounded up to the

nearest hundred grams to arrive at the shipping figure.

I make no charge for packaging materials and do not

seek to profit

from shipping and handling.

Shipping can

usually be combined for multiple purchases

(to a

maximum

of 5 kilograms in any one parcel with the exception of Canada, where

the limit is 2 kilograms). |

Packed weight of this item : approximately 600 grams

| International Shipping options: |

Details of the postage options

to various countries (via Air Mail) can be obtained by selecting

the “Postage and payments” option at the head of this listing

(above) and then selecting your country of residence from the drop-down

list. For destinations not shown or other requirements, please contact me before buying.

Due to the

extreme length of time now taken for deliveries, surface mail is no longer

a viable option and I am unable to offer it even in the case of heavy items.

I am afraid that I cannot make any exceptions to this rule.

|

Payment options for international buyers: |

-

Payment can be made by: credit card (Visa

or MasterCard, but not Amex) or PayPal. I can also accept a cheque in GBP [British

Pounds Sterling] but only if drawn on a major British bank.

-

Regretfully, due to extremely

high conversion charges, I CANNOT accept foreign currency : all payments

must be made in GBP [British Pounds Sterling]. This can be accomplished easily

using a credit card, which I am able to accept as I have a separate,

well-established business, or PayPal.

-

Please contact me with your name and address and payment details within

seven days of the end of the listing; otherwise I reserve the right to

cancel the sale and re-list the item.

-

Finally, this should be an enjoyable experience for

both the buyer and seller and I hope you will find me very easy to deal

with. If you have a question or query about any aspect (shipping,

payment, delivery options and so on), please do not hesitate to contact

me.

Prospective international

buyers should ensure that they are able to provide credit card details or

pay by PayPal within 7 days from the end of the listing (or inform me that

they will be sending a cheque in GBP drawn on a major British bank). Thank you.

|

|

|

|

|

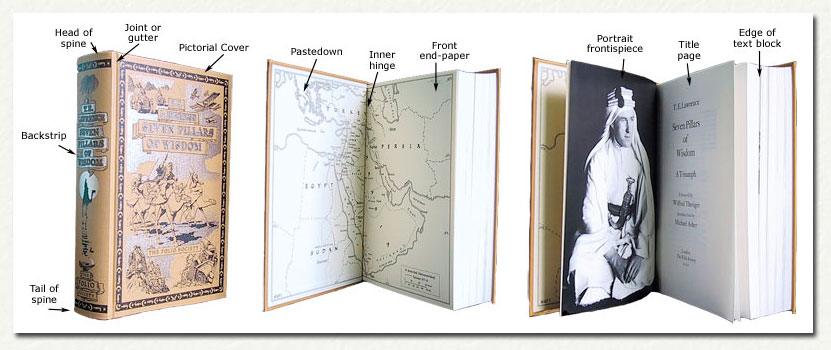

(please note that the

book shown is for illustrative purposes only and forms no part of this

listing)

Book dimensions are given in

inches, to the nearest quarter-inch, in the format width x height.

Please

note that, to differentiate them from soft-covers and paperbacks, modern

hardbacks are still invariably described as being ‘cloth’ when they are, in

fact, predominantly bound in paper-covered boards pressed to resemble cloth. |

|

|

|

|

Fine Books for Fine Minds |

I value your custom (and my

feedback rating) but I am also a bibliophile : I want books to arrive in the

same condition in which they were dispatched. For this reason, all books are

securely wrapped in tissue and a protective covering and are

then posted in a cardboard container. If any book is

significantly not as

described, I will offer a full refund. Unless the

size of the book precludes this, hardback books with a dust-jacket are

usually provided with a clear film protective cover, while

hardback books without a dust-jacket are usually provided with a rigid clear cover.

The Royal Mail, in my experience, offers an excellent service, but things

can occasionally go wrong.

However, I believe it is my responsibility to guarantee delivery.

If any book is lost or damaged in transit, I will offer a full refund.

Thank you for looking.

|

|

|

|

|

Please also

view my other listings for

a range of interesting books

and feel free to contact me if you require any additional information

Design and content © Geoffrey Miller |

|

|

|

|

|