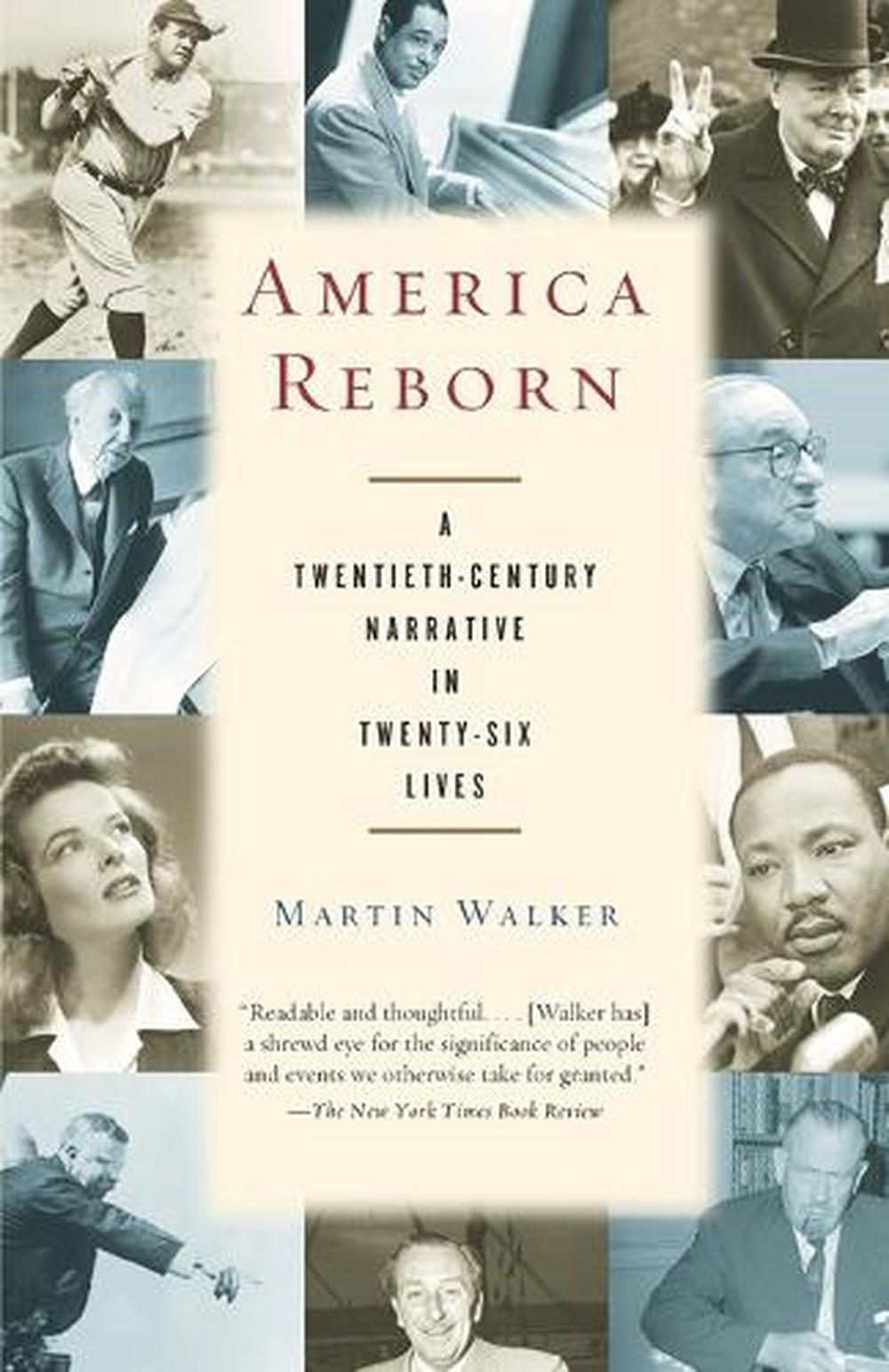

America Reborn

by Martin Walker

In America Reborn, journalist and historian Martin Walker defines twentieth-century America through the portraits of twenty-six American individuals whose accomplishments, innovations and ideals propelled the United States to a position of global dominance.

Here are the thoughts and beliefs of politicians and performers, thinkers and doers, capitalists and revolutionaries, immigrants and the native born. From Teddy Roosevelt's imperial ambitions to Bill Clinton's global vision; Emma Goldman's radical ideals to William F. Buckley's profound conservatism; Albert Einstein's elegant theories to Katharine Hepburn's elegant delivery-the biographical essays that make up this narrative show us the variety of American archetypes and offer a vision of how strong individualism has always been the bedrock of (helped make up) the American character.

Paperback

English

Brand New

Publisher Description

In America Reborn, journalist and historian Martin Walker defines twentieth-century America through the portraits of twenty-six American individuals whose accomplishments, innovations and ideals propelled the United States to a position of global dominance.

Here are the thoughts and beliefs of politicians and performers, thinkers and doers, capitalists and revolutionaries, immigrants and the native born. From Teddy Roosevelt's imperial ambitions to Bill Clinton's global vision; Emma Goldman's radical ideals to William F. Buckley's profound conservatism; Albert Einstein's elegant theories to Katharine Hepburn's elegant delivery-the biographical essays that make up this narrative show us the variety of American archetypes and offer a vision of how strong individualism has always been the bedrock of (helped make up) the American character.

Author Biography

MARTIN WALKER, after a long career of working in international journalism and for think tanks, now gardens, cooks, explores vineyards, writes and travels. His series of novels featuring Bruno, Chief of Police, are bestsellers in Europe and have been translated into more than fifteen languages. He divides his time between Washington, D.C., and the Dordogne.

Review

"Boasts wise, original insights rendered in glowing prose."–The Washington Post Book World

"Readable and thoughtful…. [Walker has] a shrewd eye for the significance of people we otherwise take for granted."–The New York Times Book Review

"One gets from Walker a lucid vision of American utopianism."–The Boston Globe

Review Quote

"Boasts wise, original insights rendered in glowing prose."The Washington Post Book World "Readable and thoughtful…. [Walker has] a shrewd eye for the significance of people we otherwise take for granted."The New York Times Book Review "One gets from Walker a lucid vision of American utopianism."TheBoston Globe

Excerpt from Book

Introduction I suspect that this book began unconsciously as a love letter to America from a foreigner who sees it both as a second home and as an inspiration. I first visited the United States in 1964 as a young officer cadet of the Royal Air Force, on a NATO exchange. Within five years, having sailed across the Atlantic on the SS France to land in time for what sounded like a promising rock festival at Woodstock, I was installed as a resident tutor at Harvard''s Kirkland House on a Harkness Fellowship. Two months later, I was traveling in a bizarre road convoy that had cars and coaches from half the colleges in New England clogging I-95 and passing jokes and joints back and forth through car windows as we went to demonstrate in Washington against the Vietnam War. The oddity was made the greater by the studied courtesy of my hosts in the city, the parents of a friend whose father was a navy captain based at the Pentagon. Each decade of my life since has been marked and enhanced by the wondrous contradictions of the American experience. In the 1970s, I was part of Senator Edmund Muskie''s presidential campaign, and also evading arrest outside the Justice Department as the antiwar demonstrations grew more heated and machine-gun posts were installed on the steps of the U.S. Capitol. In 1972, I was in Miami as a young reporter for the Democratic and Republican conventions, watching Governor George Wallace enter the convention hall in his wheelchair while the Youth for Nixon delegates in their straw hats chanted, "Four more years." I sat on the beach with Hunter Thompson the night after Senator George McGovern won his nomination, before I caught the morning plane to visit the new Disney World at Orlando. In the 1980s, I flew in from glasnost Moscow to lecture on the Chernobyl disaster and on the new phenomenon of perestroika and watched the ecstatic Washington crowds greet Mikhail Gorbachev at that extraordinary moment of the Cold War that the Washington Post dubbed "Gorbasm." By the end of the decade, I was counting dead birds on the oil-drenched beach of Knight''s Island in Alaska''s Prince William Sound as the Exxon Valdez spewed out its cargo, and sipping beer on President George Bush''s speedboat as we raced to see the seals on the rocks outside Kennebunkport, Maine. In the 1990s, as the U.S. bureau chief for The Guardian, I renewed an old Oxford acquaintanceship with Governor Bill Clinton in Little Rock, was sheltered from an angry mob by a shotgun-wielding Korean family in the Los Angeles riots, went to White House parties, and travelled on Air Force One. There is no land on earth more enthralling, more welcoming, or more generous than America. And as I stood in Oklahoma City looking at the wreckage of a terrorist bomb, and in the smoking wreckage of a black church in Georgia, and as I plucked a bullet from the charred earth of the Branch Davidian compound at Waco, Texas, no country had seemed so bafflingly alien in its appetite for violence and extremism. America has been, throughout my life, a country that has known the best of times and the worst of times, sometimes almost simultaneously. The paradoxes of the country are surreal. It is not easy to conceive how one country can embrace such extremes of wealth and poverty as the gilded oasis of Palm Springs, California, and the very different desert of the Oglala Sioux reservation at Pine Ridge, North Dakota. A country with over a million law graduates also has well over a million of its fellow citizens behind bars. The nation that provides much of the world with its graduate schools, with nearly 2 million people pursuing master''s degrees and doctorates, depends upon a deeply flawed public school system, almost a fifth of whose products are functionally illiterate. Perhaps the American system needs the constant, threatening, and warning presence of the price of failure as a social spur to achievement and success. As Gore Vidal has suggested, "It is not enough to succeed. Others must fail." The cult of the winner is a powerful one, in a land in which sporting contests are seldom permitted to end in draws, in which schoolchildren vote for their classmate "most likely to succeed," and in which college entrance is based on rigid competition. And there is no doubt that America has been the outright winner in the twentieth century''s game of nations. It began the century just starting to feel its strength and to assert itself on the world stage, and ended it, as French foreign minister Hubert Vedrine put it, not as the only superpower, but as something altogether new. America had become "the hyperpower," Vedrine suggested. It not only dominated by the usual criteria of wealth, military power, and global influence but also boasted the most advanced and innovative technologies. It enjoyed the most far-reaching cultural and commercial influence, all resting upon a democratic system of free speech and free markets that had, with the end of the Cold War, become the most self-confident ideology on the planet. Its military supremacy was unmatched since the days of ancient Rome, and its reach was incomparably wider. For the relatively modest investment of some 3.5 percent of its annual GDP, the defense budget''s lowest share of national wealth since 1940, the United States by the late 1990s could maintain with ease an unmatched military power. Even 3.5 percent of the GDP meant that the Pentagon was outspending the next nine military powers combined. The striking paradox is that the wielder of this awesome power was famously reluctant to deploy it, or at least to put the men and women of its professional forces at risk, particularly since cruise missiles and stealth warplanes allowed and even encouraged devastatingly accurate and virtually invulnerable bombardments. The country has always been uneasy about "foreign entanglements," ever since George Washington''s farewell address warned his countrymen against them. America has always been of the world, explaining in the founding document of its nationhood the need for "a decent respect for the opinions of mankind," without being overly eager to join it. The only nation that has rivaled America''s hyperpower status, Britain in the nineteenth century, was less fastidious. Lord Palmerston, the British foreign secretary who coined the term Pax Britannica at the height of its sway, had a saying: "Trade without rule where possible, trade with rule where necessary." America found rule to be as unnecessary as it was uncongenial; the overwhelming reality of its influence was sufficient to avoid the formal trappings and entanglements of empire. Some presidents sought to correct this national reluctance. Teddy Roosevelt built a canal and a fleet to prod his people into a global assertion, once the manifest destiny of continental expansion had been achieved. He was not even partially successful. It was Woodrow Wilson, that unwilling, almost apologetic interventionist, who finally took the nation into world war, but only with the understanding that he might then outlaw war altogether. The U.S. Senate rejected even this most noble of justifications for remaining a member of Europe''s great power system, and it refused to ratify his Treaty of Versailles. Nonetheless, Roosevelt and Wilson between them set the parameters of American engagement with the world in the twentieth century. Roosevelt wanted it to become dominant as the richest and most powerful of nations; Wilson sought a moral dominance that would lead the way to a new kind of world altogether, based on international law rather than on military force. The history of the second half of the century suggests that these two goals were not entirely incompatible. John Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, two presidents who secured a particularly cherished place in the nation''s heart, acted on the assumption that the country''s military and moral dominance were two sides of a single coin. The country was great because it was good, and it was good because it was great. As fortunate in the crises and the opponents they faced as in their rhetorical ability, Kennedy and Reagan were broadly able to reconcile the Rooseveltian and Wilsonian traditions of military and moral leadership. Lyndon Johnson, less astute in choosing his foreign confrontation, was not. Perhaps the most politically gifted of the postwar presidents, Johnson, during his five years in office, brought Americans back to the deeply uncomfortable and divisive thought that a great power was not necessarily a good country, and that a good power might not always be inclined or even able to assert its military greatness. The United States, against its instincts and traditions, was forced into a global role. It was bombed into war by Japan in 1941, and lured into remaining in Europe after 1947 by the blunt British warning that it alone could no longer afford to sustain the old continent against the Soviet threat. Either the United States had to assume the role or watch Stalin''s empire spread into Europe''s resulting vacuum of power by default. Even then, the deployment of American power in the Cold War was limited. It mounted an airlift to relieve West Berlin, rather than seeking a military confrontation on the ground, despite its brief monopoly of the atomic bomb. It stood by as East Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, and Poles successively rose against their Soviet masters. America''s power, when deployed, was repeatedly withdrawn or its punches pulled. The country accepted a bloody draw in Korea, defeat in Vietnam, and a stalemate with Cuba, in part because the conflicts were seen as limited ones, which didn''t need to be fought to a finish with every available weapon, and in part because of public opinion. Behind the public doubts over America''s minor wars lay a

Details