2 Used Disney Children & Family Animated VHS Tapes: Toy Story (VHS, 1996) & Walt Disney Masterpiece Pinocchio (VHS,1993). Condition of both VHS Tapes: Like New. Condition Of Toy Story (VHS, 1996) Inserts & Clamshell VHS Case: Very Good. Condition of Walt Disney Masterpiece Pinocchio (VHS,1993) Inserts & Clamshell Case: Good, but has cracks in one side of Clamshell Case.

Used Disney Children & Family Animated VHS Tape 1. Toy Story (VHS, 1996):

In the first full-length computer-animated movie, a little boy's toys are thrown into chaos when a new Space Ranger arrives to vie for supremacy with the boy's old favorite (a wooden cowboy). When the feuding toys become lost, they are forced to set aside their differences to get home. This extremely popular and successful film features the voice talents of Tom Hanks, Tim Allen, Don Rickles, Wallace Shawn, Laurie Metcalf, and others. Academy Award Nominations: 3, including Best Original Screenplay. Director John Lasseter also won a Special Achievement Academy Award for the film.

Product Details

- Rating: G (MPAA)

- UPC: 786936670332

| Additional Details | |

| Genre: | Childrens |

| Format: | VHS |

Premiere - Josh Rottenberg (12/01/1996)

Rolling Stone - Peter Travers (12/14/1995)

Sight and Sound - Leslie Felperin (03/01/1996)

USA Today - Susan Wloszczyna (11/22/1995)

Variety - Leonard Klady (11/20/1995)

Premiere - Premiere Staff (12/01/2003)

Empire - Empire Staff (03/01/2008)

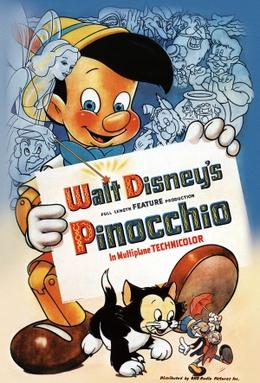

Used Disney Children & Family Animated VHS Tape 2. Walt Disney Masterpiece Pinocchio (VHS,1993):

Walt Disney's second full-length animated feature is a timeless, breathtakingly beautiful classic. Based on an 1800s story by Carlo Collodi, it stars Jiminy Cricket (voiced by Cliff Edwards) as a vagabond insect who spends a rainy night at the shop of toymaker Geppetto. The Blue Fairy brings a marionette to life after Geppetto wishes on a star for a son, and Jiminy Cricket is appointed the new boy's conscience. He has a devil of a time keeping up as Pinocchio is willingly lured through various forms of temptation, the most frightening of which leads him to Pleasure Island, where he drinks, smokes, and is almost turned into a jackass. This sequence, as well as Pinocchio's brave rescue of Geppetto from the belly of a whale, ranks among the most memorable in the history of animation. With such songs as "When You Wish Upon a Star," this is about as magical as cinema can get, a sublimely beautiful coming-of-age story for all to treasure.

Product Details

- Number of Tapes: 1

- Rating: G (MPAA)

- Film Country: USA

- UPC: 012257239034

| Additional Details | |

| Genre: | Childrens |

| Format: | VHS |

USA Today - Mike Clark (03/26/1993)

Los Angeles Times - Charles Solomon (06/26/1992)

Chicago Sun-Times - Roger Ebert (06/26/1992)

Entertainment Weekly - Ty Burr (01/11/2002)

Empire - Empire Staff (03/01/2008)

Entertainment Weekly - Chris Nashawaty (03/13/2009)

New York Times - Dave Kehr (03/06/2009)

Total Film - Neil Smith (08/01/2012)

BIP1211232VHSTSWGMP212612

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

Toy Story

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Toy Story Theatrical release poster

Directed by John Lasseter

Produced by Ralph Guggenheim

Bonnie Arnold

Screenplay by Joss Whedon

Andrew Stanton

Joel Cohen

Alec Sokolow

Story by John Lasseter

Pete Docter

Andrew Stanton

Joe Ranft

Starring Tom Hanks

Tim Allen

Don Rickles

Jim Varney

Wallace Shawn

John Ratzenberger

Annie Potts

John Morris

Laurie Metcalf

Erik von Detten

Music by Randy Newman

Editing by Robert Gordon

Lee Unkrich

Studio Pixar

Distributed by Walt Disney Pictures

Release date(s) November 22, 1995 (1995-11-22)

Running time 81 minutes

Country United States

Language English

Budget $30 million

Box office $361,958,736[1]

Directed by John Lasseter

Produced by Ralph Guggenheim

Bonnie Arnold

Screenplay by Joss Whedon

Andrew Stanton

Joel Cohen

Alec Sokolow

Story by John Lasseter

Pete Docter

Andrew Stanton

Joe Ranft

Starring Tom Hanks

Tim Allen

Don Rickles

Jim Varney

Wallace Shawn

John Ratzenberger

Annie Potts

John Morris

Laurie Metcalf

Erik von Detten

Music by Randy Newman

Editing by Robert Gordon

Lee Unkrich

Studio Pixar

Distributed by Walt Disney Pictures

Release date(s) November 22, 1995 (1995-11-22)

Running time 81 minutes

Country United States

Language English

Budget $30 million

Box office $361,958,736[1]

Toy Story is an American computer animated family comedy film produced by Pixar Animation Studios and directed by John Lasseter in 1995. Released by Walt Disney Pictures, Toy Story was the first feature length computer animated film and the first film produced by Pixar. Toy Story follows a group of anthropomorphic toys who pretend to be lifeless whenever humans are present, and focuses on Woody, a pullstring cowboy doll (Tom Hanks), and Buzz Lightyear, an astronaut action figure (Tim Allen). Woody feels profoundly threatened and jealous when Buzz supplants him as the top toy in the room. The film was written by John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Joel Cohen, Alec Sokolow, and Joss Whedon, and featured music by Randy Newman. Its executive producer was Steve Jobs with Edwin Catmull.

Pixar, who had been producing short animated films to promote their computers, was approached by Disney to produce a computer animated feature after the success of the short Tin Toy (1988), which is told from the perspective of a toy. Lasseter, Stanton, and Pete Docter wrote early story treatments which were thrown out by Disney, who pushed for a more edgy film. After disastrous story reels, production was halted and the script was re-written, better reflecting the tone and theme Pixar desired: that "toys deeply want children to play with them, and that this desire drives their hopes, fears, and actions."[2] The studio, then consisting of a relatively small number of employees, produced the film under minor financial constraints.[3][4]

The top-grossing film on its opening weekend,[5] Toy Story went on to earn over $361 million worldwide.[1] Reviews were highly positive, praising both the technical innovation of the animation and the wit and sophistication of the screenplay,[6][7] and it is now widely considered, by many critics, to be one of the best animated films.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] In addition to home media releases and theatrical re-releases, Toy Story-inspired material has run the gamut from toys, video games, theme park attractions, spin-offs, merchandise, and two sequels—Toy Story 2 (1999) and Toy Story 3 (2010)—both of which received massive commercial success and critical acclaim. Toy Story was selected into the National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" in 2005, its first year of eligibility.[15]

Contents:

1 Plot

2 Cast

2.1 Cast notes

3 Production

3.1 Development

3.2 Writing

3.3 Casting

3.4 Production shutdown

3.5 Animation

3.6 Music

3.7 Editing and pre-release

4 Soundtrack

5 Release

5.1 Marketing

5.2 3-D re-release

5.3 Reception

5.4 Box office performance

5.5 Accolades

5.6 Home media

6 Impact and legacy

6.1 "To Infinity and Beyond"

6.2 Sequels, shows, and spin-offs

6.3 Software and merchandise

6.4 Theme park attractions

1 Plot

2 Cast

2.1 Cast notes

3 Production

3.1 Development

3.2 Writing

3.3 Casting

3.4 Production shutdown

3.5 Animation

3.6 Music

3.7 Editing and pre-release

4 Soundtrack

5 Release

5.1 Marketing

5.2 3-D re-release

5.3 Reception

5.4 Box office performance

5.5 Accolades

5.6 Home media

6 Impact and legacy

6.1 "To Infinity and Beyond"

6.2 Sequels, shows, and spin-offs

6.3 Software and merchandise

6.4 Theme park attractions

Plot:

Woody is a pull-string cowboy doll and leader of a group of toys that belong to a boy named Andy Davis, which act lifeless when humans are present. With his family moving homes one week before his birthday, the toys stage a reconnaissance mission to discover Andy's new presents. Andy receives a space ranger Buzz Lightyear action figure, whose impressive features see him replacing Woody as Andy's favorite toy. Woody is resentful, especially as Buzz also gets attention from the other toys. However Buzz believes himself to be a real space ranger on a mission to return to his home planet, as Woody fails to convince him he is a toy.

Woody is a pull-string cowboy doll and leader of a group of toys that belong to a boy named Andy Davis, which act lifeless when humans are present. With his family moving homes one week before his birthday, the toys stage a reconnaissance mission to discover Andy's new presents. Andy receives a space ranger Buzz Lightyear action figure, whose impressive features see him replacing Woody as Andy's favorite toy. Woody is resentful, especially as Buzz also gets attention from the other toys. However Buzz believes himself to be a real space ranger on a mission to return to his home planet, as Woody fails to convince him he is a toy.

Andy prepares for a family outing at the space themed Pizza Planet restaurant with Buzz. Woody attempts to be picked by misplacing Buzz. He intends to trap Buzz in a gap behind Andy's desk, but the plan goes disastrously wrong when he accidentally knocks Buzz out the window, resulting in him being accused of murdering Buzz out of jealousy. With Buzz missing, Andy takes Woody to Pizza Planet, but Buzz climbs into the car and confronts Woody when they stop at a gas station. The two fight and fall out of the car, which drives off and leaves them behind. Woody spots a truck bound for Pizza Planet and plans to rendezvous with Andy there, convincing Buzz to come with him by telling him it will take him to his home planet. Once at Pizza Planet, Buzz makes his way into a claw game machine shaped like a spaceship, thinking it to be the ship Woody promised him. Inside, he finds squeaky aliens who revere the claw arm as their master. When Woody clambers into the machine to rescue Buzz, the aliens force the two towards the claw and they are captured by Andy’s neighbor Sid Phillips, who finds amusement in torturing and destroying toys.

At Sid's house, the two attempt to escape before Andy's moving day, encountering Sid’s nightmarish toy creations and his vicious dog, Scud. Buzz sees a commercial for Buzz Lightyear action figures and realizes that he really is a toy. Attempting to fly to test this, Buzz falls and loses one of his arms, going into depression and unable to cooperate with Woody. Woody waves Buzz’s arm from a window to seek help from the toys in Andy’s room, but they are horrified thinking Woody attacked him, while Woody realizes Sid's toys are friendly when they reconnect Buzz's arm. Sid prepares to destroy Buzz by strapping him to a rocket, but is delayed that evening by a thunderstorm. Woody convinces Buzz that life is worth living because of the joy he can bring to Andy, which helps Buzz regain his spirit. Cooperating with Sid's toys, Woody rescues Buzz and scares Sid away by coming to life in front of him, warning him to never torture toys again. Woody and Buzz then wave goodbye to the mutant toys and return home through a fence, but miss Andy’s car as it drives away to his new house.

Down the road, they climb onto the moving truck containing Andy’s other toys, but Scud chases them and Buzz tackles the dog to save Woody. Woody attempts to rescue Buzz with Andy's RC car but the other toys, who think Woody now got rid of RC, toss Woody off onto the road. Spotting Woody driving RC back with Buzz alive, the other toys realize their mistake and try to help. When RC's batteries become depleted, Woody ignites the rocket on Buzz's back and manages to throw RC into the moving truck before they soar into the air. Buzz opens his wings to cut himself free before the rocket explodes, gliding with Woody to land safely into a box in Andy’s car. Andy looks into it and is elated to have found his two missing toys.

On Christmas Day at their new house, Buzz and Woody stage another reconnaissance mission to prepare for the new toy arrivals, one of which is a Mrs. Potato Head, much to the delight of Mr. Potato Head. As Woody jokingly asks what might be worse than Buzz, the two share a worried smile as they discover Andy's new gift is a puppy.

Cast:

Main article: List of Toy Story characters

Main cast:

Main article: List of Toy Story characters

Main cast:

Tom Hanks as Woody, a cowboy pull string doll

Tim Allen as Buzz Lightyear, a Space Ranger doll

Don Rickles as Mr. Potato Head, a potato shaped doll with put together pieces on his body

Jim Varney as Slinky Dog, a slink toy

Wallace Shawn as Rex, a cowardly green Tyrannosaurus Rex

John Ratzenberger as Hamm, a piggy bank

Annie Potts as Bo Peep, a shepherdess and Woody's love interest

John Morris as Andy Davis, the young boy who owns all the toys

Erik von Detten as Sid Phillips, Andy's former next door neighbour, who destroys toys for his own amusement

Laurie Metcalf as Andy's Mom

R. Lee Ermey as Sarge, a green plastic figure soldier

Sarah Freeman as Hannah Phillips, Sid's sister

Penn Jillette as TV Announcer

Additional voices

Jack Angel as Shark/Rocky Gibraltar

Greg Berg as Minesweeper Soldier

Debi Derryberry as Squeeze Toy Aliens/Pizza Planet Intercom

Mickie McGowan as Sid's Mom

Ryan O'Donohue as kid in Buzz Lightyear commercial

Jeff Pidgeon as Squeeze Toy Aliens/Mr. Spell/Robot

Phil Proctor as Pizza Planet guard/bowling announcer

Joe Ranft as Lenny

Andrew Stanton as Buzz Lightyear commercial chorus

Cast notes:

Tim Allen as Buzz Lightyear, a Space Ranger doll

Don Rickles as Mr. Potato Head, a potato shaped doll with put together pieces on his body

Jim Varney as Slinky Dog, a slink toy

Wallace Shawn as Rex, a cowardly green Tyrannosaurus Rex

John Ratzenberger as Hamm, a piggy bank

Annie Potts as Bo Peep, a shepherdess and Woody's love interest

John Morris as Andy Davis, the young boy who owns all the toys

Erik von Detten as Sid Phillips, Andy's former next door neighbour, who destroys toys for his own amusement

Laurie Metcalf as Andy's Mom

R. Lee Ermey as Sarge, a green plastic figure soldier

Sarah Freeman as Hannah Phillips, Sid's sister

Penn Jillette as TV Announcer

Additional voices

Jack Angel as Shark/Rocky Gibraltar

Greg Berg as Minesweeper Soldier

Debi Derryberry as Squeeze Toy Aliens/Pizza Planet Intercom

Mickie McGowan as Sid's Mom

Ryan O'Donohue as kid in Buzz Lightyear commercial

Jeff Pidgeon as Squeeze Toy Aliens/Mr. Spell/Robot

Phil Proctor as Pizza Planet guard/bowling announcer

Joe Ranft as Lenny

Andrew Stanton as Buzz Lightyear commercial chorus

Cast notes:

Non-speaking characters include Scud, Barrel of Monkeys, Etch A Sketch, Snake, Clown, and Buster.

Production:

Development

Director John Lasseter's first experience with computer animation was during his work as an animator at Disney, when two of his friends showed him the lightcycle scene from Tron. It was an eye-opening experience which awakened Lasseter to the possibilities offered by the new medium of computer-generated animation.[16] Lasseter tried to pitch the idea of a fully computer animated film to Disney, but the idea was rejected and Lasseter was fired. He then went on to work at Lucasfilm and later as a founding member of Pixar, which was purchased by entrepreneur and Apple Computer founder Steve Jobs in 1986.[17] At Pixar, Lasseter created short, computer-animated films to show off the Pixar Image Computer's capabilities, and Tin Toy (1988) —a short told from the perspective of a toy, referencing Lasseter's love of classic toys— would go on to claim the 1988 Academy Award for animated short films, the first computer- generated film to do so.[18] Tin Toy gained Disney's attention, and the new team at Disney—CEO Michael Eisner and chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg in the film division —began a quest to get Lasseter to come back.[18] Lasseter, grateful for Jobs’s faith in him, felt compelled to stay with Pixar, telling co-founder Ed Catmull, "I can go to Disney and be a director, or I can stay here and make history."[18] Katzenberg realized he could not lure Lasseter back to Disney and therefore set plans into motion to ink a production deal with Pixar to produce a film.[18]

Both sides were willing. Catmull and fellow Pixar co-founder Alvy Ray Smith had long wanted to produce a computer-animated feature.[19] In addition, The Walt Disney Company had licensed Pixar's Computer Animation Production System (CAPS), and that made it the largest customer for Pixar’s computers.[20] Jobs made it apparent to Katzenberg that although Disney was happy with Pixar, it was not the other way around: "We want to do a film with you," said Jobs. "That would make us happy."[20] At this same time, Peter Schneider, president of Walt Disney Feature Animation, was potentially interested in making a feature film with Pixar.[19] When Catmull, Smith and head of animation Ralph Guggenheim met with Schneider in the summer of 1990, they found the atmosphere to be puzzling and contentious. They later learned that Katzenberg intended that if Disney were to make a film with Pixar, it would be outside Schneider's purview, which aggravated Schneider.[21] After that first meeting, the Pixar contingent went home with low expectations and were surprised when Katzenberg called for another conference. Catmull, Smith and Guggenheim were joined by Bill Reeves (head of animation research and development), Jobs, and Lasseter. They brought with them an idea for a half-hour television special called A Tin Toy Christmas. They reasoned that a television program would be a sensible way to gain experience before tackling a feature film.[22]

They met with Katzenberg at a conference table in the Team Disney building at the company's headquarters in Burbank.[22] Catmull and Smith considered it would be difficult to keep Katzenberg interested in working with the company over time. They considered it even more difficult to sell Lasseter and the junior animators on the idea of working with Disney, who had a bad reputation for how they treated their animators, and Katzenberg, who had built a reputation as a micromanaging tyrant.[22] Katzenberg asserted this himself in the meeting: "Everybody thinks I’m a tyrant. I am a tyrant. But I’m usually right."[20] He threw out the idea of a half-hour special and eyed Lasseter as the key talent in the room: "John, since you won't come work for me, I'm going to make it work this way."[20][22] He invited the six visitors to mingle with the animators—"ask them anything at all"—and the men did so, finding they all backed up Katzenberg's statements. Lasseter felt he would be able to work with Disney and the two companies began negotiations.[23] Pixar at this time was on the verge of bankruptcy and needed a deal with Disney.[20] Katzenberg insisted that Disney be given the rights to Pixar’s proprietary technology for making 3-D animation, but Jobs refused.[23] In another case, Jobs demanded Pixar would have part ownership of the film and its characters, sharing control of both video rights and sequels, but Katzenberg refused.[20] Disney and Pixar reached accord on contract terms in an agreement dated May 3, 1991, and signed on in early July.[24] Eventually the deal specified that Disney would own the picture and its characters outright, have creative control, and pay Pixar about 12.5% of the ticket revenues.[25][26] It had the option (but not the obligation) to do Pixar’s next two films and the right to make (with or without Pixar) sequels using the characters in the film. Disney could also kill the film at any time with only a small penalty. These early negotiations would become a point of contention between Jobs and Eisner for many years.[20]

An agreement to produce a feature film based on Tin Toy with a working title of Toy Story was finalized and production began soon thereafter.[27]

Writing:

The original treatment for Toy Story, drafted by Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, and Pete Docter, had little in common with the eventual finished film.[2] It paired Tinny, the one-man band from Tin Toy with a ventriloquist's dummy and sent them on a sprawling odyssey. The core idea of Toy Story was present from the treatment onward, however: that "toys deeply want children to play with them, and that this desire drives their hopes, fears, and actions."[2] Katzenberg felt the original treatment was problematic and told Lasseter to reshape Toy Story as more of an odd-couple buddy picture, and suggested they watch some classic buddy movies, such as The Defiant Ones and 48 Hrs., in which two characters with different attitudes are thrown together and have to bond.[28][29] Lasseter, Stanton, and Docter emerged in early September 1991 was the second treatment, and although the lead characters were still Tinny and the dummy, the outline of the final film was beginning to take shape.[28]

The original treatment for Toy Story, drafted by Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, and Pete Docter, had little in common with the eventual finished film.[2] It paired Tinny, the one-man band from Tin Toy with a ventriloquist's dummy and sent them on a sprawling odyssey. The core idea of Toy Story was present from the treatment onward, however: that "toys deeply want children to play with them, and that this desire drives their hopes, fears, and actions."[2] Katzenberg felt the original treatment was problematic and told Lasseter to reshape Toy Story as more of an odd-couple buddy picture, and suggested they watch some classic buddy movies, such as The Defiant Ones and 48 Hrs., in which two characters with different attitudes are thrown together and have to bond.[28][29] Lasseter, Stanton, and Docter emerged in early September 1991 was the second treatment, and although the lead characters were still Tinny and the dummy, the outline of the final film was beginning to take shape.[28]

The script went through many changes before the final version. Lasseter decided Tinny was "too antiquated", and the character was changed to a military action figure, and then given a space theme. Tinny's name changed to Lunar Larry, then Tempus from Morph, and eventually Buzz Lightyear (after astronaut Buzz Aldrin).[30] Lightyear's design was modeled on the suits worn by Apollo astronauts as well as G.I. Joe action figures.[31][32] Woody the second character, was inspired by a Casper the Friendly Ghost doll that Lasseter had when he was a child. Originally Woody was a ventriloquist's dummy with a pull-string (hence the name Woody). However, character designer, Bud Luckey suggested that Woody could be changed to a cowboy ventriloquist dummy, John Lasseter liked the contrast between the Western genre and the Sci-Fi genre and the character immediately changed. Eventually all the ventriloquist dummy aspects of the character were deleted, because the dummy was designed to look "sneaky and mean."[33] However they kept the name Woody to pay homage to the Western Actor Woody Strode.[30] The story department drew inspiration from films such as Midnight Run and The Odd Couple,[34] and Lasseter screened Hayao Miyazaki's Castle in the Sky (1986) for further influence.[35]

Toy Story's script was strongly influenced by the ideas of screenwriter Robert McKee. The members of Pixar's story team—Lasseter, Stanton, Docter and Joe Ranft—were aware that most of them were beginners at writing for feature films. None of them had any feature story or writing credits to their name besides Ranft, who had taught a story class at CalArts and did some storyboard work prior.[33] Seeking insight, Lasseter and Docter attended a three-day seminar in Los Angeles given by McKee. His principles, grounded in Aristotle's Poetics, dictated that a character emerges most realistically and compellingly from the choices that the protagonist makes in reaction to his problems.[35] Disney also appointed Joel Cohen, Alec Sokolow and, later, Joss Whedon to help develop the script. Whedon found that the script wasn't working but had a great structure, and added the character of Rex and sought a pivotal role for Barbie.[36] The story team continued to touch up the script as production was underway. Among the late additions was the encounter between Buzz and the alien squeak toys at Pizza Planet, which emerged from a brainstorming session with a dozen directors, story artists, and animators from Disney.[37]

Casting:

Katzenberg gave approval for the script on January 19, 1993, at which point voice casting could begin.[38] Lasseter always wanted Tom Hanks to play the character of Woody. Lasseter claimed Hanks "... has the ability to take emotions and make them appealing. Even if the character, like the one in A League of Their Own, is down-and-out and despicable."[38] Billy Crystal was approached to play Buzz, but turned down the role, which he later regretted, although he would voice Mike Wazowski in Pixar's later success, Monsters, Inc..[39][40] Lasseter took the role to Tim Allen, who was appearing in Disney's Home Improvement, and he accepted.[41]

Katzenberg gave approval for the script on January 19, 1993, at which point voice casting could begin.[38] Lasseter always wanted Tom Hanks to play the character of Woody. Lasseter claimed Hanks "... has the ability to take emotions and make them appealing. Even if the character, like the one in A League of Their Own, is down-and-out and despicable."[38] Billy Crystal was approached to play Buzz, but turned down the role, which he later regretted, although he would voice Mike Wazowski in Pixar's later success, Monsters, Inc..[39][40] Lasseter took the role to Tim Allen, who was appearing in Disney's Home Improvement, and he accepted.[41]

To gauge how an actor's voice would fit with a character, Lasseter borrowed a common Disney technique: animate a vocal monologue from a well-established actor to meld the actor's voice with the appearance or actions of the animated character.[36] This early test footage, using Hanks' voice from Turner & Hooch, convinced Hanks to sign on to the film.[38][42] Toy Story was both Hanks and Allen's first animated film role.[43]

Production shutdown:

Every couple of weeks, Lasseter and his team would put together their latest set of storyboards or footage to show Disney. In early screen tests, Pixar impressed Disney with the technical innovation but convincing Disney of the plot was more difficult. At each presentation by Pixar, Katzenberg would tear much of it up, giving out detailed comments and notes. Katzenberg’s big push was to add more edginess to the two main characters.[29] Disney wanted the film to appeal to both children and adults, and asked for adult references to be added to the film.[38] After many rounds of notes from Katzenberg and other Disney execs, the general consensus was that Woody had been stripped of almost all charm.[29][41] Tom Hanks, while recording the dialogue for the story reels, exclaimed at one point that the character was a jerk.[29] Lasseter and his Pixar team had the first half of the movie ready to screen, so they brought it down to Burbank to show to Katzenberg and other Disney executives on November 19, 1993, a day they later dubbed "Black Friday."[4][38] The results were disastrous, and Schneider, who was never particularly enamored of Katzenberg’s idea of having outsiders make animation for Disney, declared it a mess and ordered that production be stopped immediately.[44] Katzenberg asked colleague Tom Schumacher why the reels were bad. Schumacher replied bluntly: "Because it’s not their movie anymore."[4]

Every couple of weeks, Lasseter and his team would put together their latest set of storyboards or footage to show Disney. In early screen tests, Pixar impressed Disney with the technical innovation but convincing Disney of the plot was more difficult. At each presentation by Pixar, Katzenberg would tear much of it up, giving out detailed comments and notes. Katzenberg’s big push was to add more edginess to the two main characters.[29] Disney wanted the film to appeal to both children and adults, and asked for adult references to be added to the film.[38] After many rounds of notes from Katzenberg and other Disney execs, the general consensus was that Woody had been stripped of almost all charm.[29][41] Tom Hanks, while recording the dialogue for the story reels, exclaimed at one point that the character was a jerk.[29] Lasseter and his Pixar team had the first half of the movie ready to screen, so they brought it down to Burbank to show to Katzenberg and other Disney executives on November 19, 1993, a day they later dubbed "Black Friday."[4][38] The results were disastrous, and Schneider, who was never particularly enamored of Katzenberg’s idea of having outsiders make animation for Disney, declared it a mess and ordered that production be stopped immediately.[44] Katzenberg asked colleague Tom Schumacher why the reels were bad. Schumacher replied bluntly: "Because it’s not their movie anymore."[4]

Lasseter was embarrassed with what was on the screen, later recalling, "It was a story filled with the most unhappy, mean characters that I’ve ever seen." He asked Disney for the chance to retreat back to Pixar and rework the script in two weeks, and Katzenberg was supportive.[4] Lasseter, Stanton, Docter and Ranft delivered the news of the production shutdown to the production crew, many of whom had left other jobs to work on the project. In the meantime, the crew would shift to television commercials while the head writers worked out a new script. Although Lasseter kept morale high by remaining outwardly buoyant, the production shutdown was "a very scary time," recalled story department manager BZ Petroff.[45] Schneider had initially wanted to shutdown production altogether and fire all recently hired animators.[46] Katzenberg put the film under the wing of Disney Feature Animation. The Pixar team was pleased that the move would give them an open door to counsel from Disney's animation veterans. Schenider, however, continued to take a dim view of the project and would later go over Katzenberg's head to urge Eisner to cancel it.[28] Stanton retreated into a small, dark windowless office, emerging periodically with new script pages. He and the other story artists would then draw the shots on storyboards. Whedon came back to Pixar for part of the shutdown to help with revising, and the script was revised in two weeks as promised.[45] When Katzenberg and Schneider halted production on Toy Story, Steve Jobs kept the work going with his own personal funding. Jobs did not insert himself much into the creative process, respecting the artists at Pixar and instead managing the relationship with Disney.[4]

The Pixar team came back with a new script three months later, with the character of Woody morphed from being a tyrannical boss of Andy’s other toys to being their wise leader. It also included a more adult-oriented staff meeting amongst the toys rather than a juvenile group discussion that had existed in earlier drafts. Buzz Lightyear's character was also changed slightly "to make it more clear to the audience that he really doesn't realize he's a toy."[46] Katzenberg and Schneider approved the new approach, and by February 1994 the film was back in production.[4] The voice actors returned in March 1994 to record their new lines.[38] When production was greenlit, the crew quickly grew from its original size of 24 to 110, including 27 animators, 22 technical directors, and 61 other artists and engineers.[3][47] In comparison, The Lion King, released in 1994, required a budget of $45 million and a staff of 800.[3] In the early budgeting process, Jobs was eager to produce the film as efficiently as possible, impressing Katzenberg with his focus on cost-cutting. Despite this, the $17 million production budget was proving inadequate, especially given the major revision that was necessary after Katzenberg had pushed them to make Woody too edgy. Jobs demanded more funds in order to complete the film right, and insisted that Disney was liable for the cost overruns. Katzenberg was not willing, and Ed Catmull, described as "more diplomatic than Jobs," was able to reach a compromise new budget.[4]

Animation:

"We couldn't have made this movie in traditional animation. This is a story that can only really be told with three-dimensional toy characters. ... Some of the shots in this film are so beautiful."

"We couldn't have made this movie in traditional animation. This is a story that can only really be told with three-dimensional toy characters. ... Some of the shots in this film are so beautiful."

—Tom Schumacher, Vice President of Walt Disney Feature Animation[48]Toy Story was the first fully computer animated feature film. Recruiting animators for Toy Story was brisk; the magnet for talent was not the pay, generally mediocre, but rather the allure of taking part in the first computer-animated feature.[47] Lasseter spoke on the challenges of the computer animation in the film: "We had to make things look more organic. Every leaf and blade of grass had to be created. We had to give the world a sense of history. So the doors are banged up, the floors have scuffs."[38] The film began with animated storyboards to guide the animators in developing the characters. 27 animators worked on the film, using 400 computer models to animate the characters. Each character was either created out of clay or was first modeled off of a computer-drawn diagram before reaching the computer animated design.[49] Once the animators had a model, articulation and motion controls were coded, allowing each character to move in a variety of ways, such as talking, walking, or jumping.[49] Of all of the characters, Woody was the most complex as he required 723 motion controls, including 212 for his face and 58 for his mouth.[38][50] The first piece of animation, a 30-second test, was delivered to Disney in June 1992 when the company requested a sample of what the film would look like. Lasseter wanted to impress Disney with a number of things in the test piece that could not be done in traditional, hand-drawn animation, such as Woody's plaid shirt or venetian blind shadows falling across the room.[33]

Every shot in the film passed through the hands of eight different teams. The art department gave a shot its color scheme and general lighting.[51] The layout department, under Craig Good, then placed the models in the shot, framed the shot by setting the location of the virtual camera, and programmed any camera moves. To make the medium feel as familiar as possible, they sought to stay within the limits of what might be done in a live-action film with real cameras, dollies, tripods and cranes.[51] From layout, a shot went to the animation department, headed by directing animators Rich Quade and Ash Brannon. Lasseter opted against Disney's approach of assigning an animator to work on a character throughout a film, but made certain exceptions in scenes where he felt acting was particularly critical.[51] The animators used the Menv program to set the character into a desired pose. Once a sequence of hand-built poses, or "keyframes", was created, the software would build the poses from the frames in-between.[52] The animators studied videotapes of the actors for inspiration, and Lasseter rejected automatic lip-syncing.[52] To sync the characters mouths and facial expressions to the actors' voices, animators spent a week per 8 seconds of animation.[49]

After this the animators would compile the scenes, and develop a new storyboard with the computer animated characters. Animators then added shading, lighting, visual effects, and finally used 300 computer processors to render the film to its final design.[49][50] The shading team, under Tom Porter, used RenderMan's shader language to create shader programs for each of a model's surfaces. A few surfaces in Toy Story came from real objects: a shader for the curtain fabric in Andy's room used a scan of actual cloth.[53] After animation and shading, the final lighting of the shot was orchestrated by the lighting team, under Galyn Susman and Sharon Calahan. The completed shot then went into rendering on a "render farm" of 117 Sun Microsystems computers that ran 24 hours a day.[37] Finished animation emerged in a steady drip of around three minutes a week.[54] Each frame took from 45 minutes up to 30 hours to render, depending on its complexity. In total, the film required 800,000 machine hours and 114,240 frames of animation.[38][49][55] There is over 77 minutes of animation spread across 1,561 shots.[51] A camera team, aided by David DiFrancesco, recorded the frames onto film stock. Toy Story was rendered at a mere 1,536 by 922 pixels, with each pixel corresponding to roughly a quarter inch of screen area on a typical cinema screen.[37] During post-production, the film was sent to Skywalker Sound where sound effects were mixed with the music score.[50]

Music:

Disney was concerned with Lasseter's position on the use of music. Unlike other Disney films of the time, Lasseter did not want the film to be a musical, saying it was a buddy film featuring "real toys." Joss Whedon agreed saying, "It would have been a really bad musical, because it's a buddy movie. It's about people who won't admit what they want, much less sing about it. ... Buddy movies are about sublimating, punching an arm, 'I hate you.' It's not about open emotion."[38] However, Disney favored the musical format, claiming "Musicals are our orientation. Characters breaking into song is a great shorthand. It takes some of the onus off what they're asking for."[38] Disney and Pixar reached a compromise: the characters in Toy Story would not break into song, but the film would use songs over the action, as in The Graduate, to convey and amplify the emotions that Buzz and Woody were feeling.[36] Disney tapped Randy Newman to compose the film. The edited Toy Story was due to Randy Newman and Gary Rydstrom in late September 1995 for their final work on the score and sound design, respectively.[56]

Disney was concerned with Lasseter's position on the use of music. Unlike other Disney films of the time, Lasseter did not want the film to be a musical, saying it was a buddy film featuring "real toys." Joss Whedon agreed saying, "It would have been a really bad musical, because it's a buddy movie. It's about people who won't admit what they want, much less sing about it. ... Buddy movies are about sublimating, punching an arm, 'I hate you.' It's not about open emotion."[38] However, Disney favored the musical format, claiming "Musicals are our orientation. Characters breaking into song is a great shorthand. It takes some of the onus off what they're asking for."[38] Disney and Pixar reached a compromise: the characters in Toy Story would not break into song, but the film would use songs over the action, as in The Graduate, to convey and amplify the emotions that Buzz and Woody were feeling.[36] Disney tapped Randy Newman to compose the film. The edited Toy Story was due to Randy Newman and Gary Rydstrom in late September 1995 for their final work on the score and sound design, respectively.[56]

Lasseter claimed "His songs are touching, witty, and satirical, and he would deliver the emotional underpinning for every scene."[38] Newman developed the film's signature song "You've Got a Friend in Me" in one day[38] although the tune is closely based on his own song, "I Love to See You Smile" from the soundtrack to the 1989 film, Parenthood.

Editing and pre-release:

It was difficult for crew members to perceive the film's quality during much of the production process, when the finished footage was in scattered pieces and lacked elements like music and sound design.[54] Some animators felt the film would be a significant disappointment commercially, but felt animators and animation fans would find it interesting.[54] According to Lee Unkrich, one of the original editors of Toy Story, a scene was cut out of the original final edit. The scene features Sid, after Pizza Planet, torturing Buzz and Woody violently. Unkrich decided to cut right into the scene where Sid is interrogating the toys because the creators of the movie thought the audience would be loving Buzz and Woody at that point.[57] Another scene, where Woody was trying to get Buzz's attention when he was stuck in the box crate, was shortened because the creators felt it would lose the energy of the movie.[57] Peter Schneider had grown buoyant about the film as it neared completion, and announced a United States release date of November, coinciding with Thanksgiving weekend and the start of the winter holiday season.[58]

It was difficult for crew members to perceive the film's quality during much of the production process, when the finished footage was in scattered pieces and lacked elements like music and sound design.[54] Some animators felt the film would be a significant disappointment commercially, but felt animators and animation fans would find it interesting.[54] According to Lee Unkrich, one of the original editors of Toy Story, a scene was cut out of the original final edit. The scene features Sid, after Pizza Planet, torturing Buzz and Woody violently. Unkrich decided to cut right into the scene where Sid is interrogating the toys because the creators of the movie thought the audience would be loving Buzz and Woody at that point.[57] Another scene, where Woody was trying to get Buzz's attention when he was stuck in the box crate, was shortened because the creators felt it would lose the energy of the movie.[57] Peter Schneider had grown buoyant about the film as it neared completion, and announced a United States release date of November, coinciding with Thanksgiving weekend and the start of the winter holiday season.[58]

Sources indicate that executive producer Steve Jobs lacked confidence in the film during its production, and he had been talking to various companies, ranging from Hallmark to Microsoft, about selling Pixar.[4][58] However, as the film progressed, Jobs became ever more excited about it, feeling that he might be on the verge of transforming the movie industry.[4] As scenes from the movie were finished, he watched them repeatedly and had friends come by his home to share his new passion. Jobs decided that the release of Toy Story that November would be the occasion to take Pixar public.[4] A test audience near Anaheim in late July 1995 indicated the need for last-minute tweaks, which added further pressure to the already frenetic final weeks. Response cards from the audience were encouraging, but were not top of the scale, adding further question as to how audiences would respond.[56] The film ended with a shot of Andy's house and the sound of a new puppy. Michael Eisner, who attended the screening, told Lasseter afterward that the film needed to end with a shot of Woody and Buzz together, reacting to the news of the puppy.[56]

Soundtrack Toy Story:

Soundtrack album by Randy Newman

Released November 22, 1995

Genre Score

Length 51:44

Label Walt Disney

Producer Chris Montan (Don Davis, Jim Flamberg, Don Was, Frank Wolf, Randy Newman)

Pixar soundtrack chronology

Toy Story

(1995) A Bug's Life

(1998)

Singles from Toy Story

1."You've Got a Friend in Me"

Released: April 12, 1996[59]

Professional ratings

Review scores

Source Rating

AllMusic

Filmtracks

Movie Wave

The soundtrack for Toy Story was produced by Walt Disney Records and was released on November 22, 1995, the week of the film's release. Scored and written by Randy Newman, the soundtrack has received praise for its "sprightly, stirring score".[60] Despite the album's critical success, the soundtrack only peaked at number 94 on the Billboard 200 album chart.[61] A cassette and CD single release of "You've Got a Friend in Me" was released on April 12, 1996, in order to promote the soundtrack's release.[59] The soundtrack was remastered in 2006 and although it is no longer available physically, the album is available for purchase digitally in retailers such as iTunes.[62]

Track listings[60][62]

All songs written and composed by Randy Newman.

All songs written and composed by Randy Newman.

No. Title Length

1. "You've Got a Friend in Me" (performed by Newman) 2:04

2. "Strange Things" (performed by Newman) 3:18

3. "I Will Go Sailing No More" (performed by Newman) 2:57

4. "Andy's Birthday" 5:58

5. "Soldier's Mission" 1:29

6. "Presents" 1:09

7. "Buzz" 1:40

8. "Sid" 1:21

9. "Woody and Buzz" 4:29

10. "Mutants" 6:05

11. "Woody's Gone" 2:13

12. "The Big One" 2:51

13. "Hang Together" 6:02

14. "On the Move" 6:18

15. "Infinity and Beyond" 3:09

16. "You've Got a Friend in Me (Duet Version)" (performed by Newman, Lyle Lovett) 2:42

Total length: 51:44

1. "You've Got a Friend in Me" (performed by Newman) 2:04

2. "Strange Things" (performed by Newman) 3:18

3. "I Will Go Sailing No More" (performed by Newman) 2:57

4. "Andy's Birthday" 5:58

5. "Soldier's Mission" 1:29

6. "Presents" 1:09

7. "Buzz" 1:40

8. "Sid" 1:21

9. "Woody and Buzz" 4:29

10. "Mutants" 6:05

11. "Woody's Gone" 2:13

12. "The Big One" 2:51

13. "Hang Together" 6:02

14. "On the Move" 6:18

15. "Infinity and Beyond" 3:09

16. "You've Got a Friend in Me (Duet Version)" (performed by Newman, Lyle Lovett) 2:42

Total length: 51:44

Charts

Chart (1995) Peak

position

U.S. Billboard 200[61] 94

Chart (1995) Peak

position

U.S. Billboard 200[61] 94

Release:

There were two premieres of Toy Story in November 1995. Disney organized one at El Capitan in Los Angeles, and built a fun house next door featuring the characters. Jobs did not attend and instead rented the Regency, a similar theater in San Francisco, and held his own premiere the next night. Instead of Tom Hanks and Steve Martin, the guests were Silicon Valley celebrities, such as Larry Ellison and Andy Grove. The dueling premieres highlighted a festering issue between the companies: whether Toy Story was a Disney or a Pixar movie.[63] "The audience appeared to be captivated by the film," wrote David Price in his 2008 book The Pixar Touch. "Adult-voiced sobs could be heard during the quiet moments after Buzz Lightyear fell and lay broken on the stairway landing."[64] Toy Story opened on 2,281 screens in in the United States on November 22, 1995 (before later expanding to 2,574 screens).[64] It was paired alongside a rerelease of a Roger Rabbit short called Rollercoaster Rabbit, while select prints contained The Adventures of André and Wally B..

There were two premieres of Toy Story in November 1995. Disney organized one at El Capitan in Los Angeles, and built a fun house next door featuring the characters. Jobs did not attend and instead rented the Regency, a similar theater in San Francisco, and held his own premiere the next night. Instead of Tom Hanks and Steve Martin, the guests were Silicon Valley celebrities, such as Larry Ellison and Andy Grove. The dueling premieres highlighted a festering issue between the companies: whether Toy Story was a Disney or a Pixar movie.[63] "The audience appeared to be captivated by the film," wrote David Price in his 2008 book The Pixar Touch. "Adult-voiced sobs could be heard during the quiet moments after Buzz Lightyear fell and lay broken on the stairway landing."[64] Toy Story opened on 2,281 screens in in the United States on November 22, 1995 (before later expanding to 2,574 screens).[64] It was paired alongside a rerelease of a Roger Rabbit short called Rollercoaster Rabbit, while select prints contained The Adventures of André and Wally B..

The film was also shown at the Berlin Film Festival out of competition from February 15 to 26, 1996.[65] Elsewhere, the film opened in March 1996.[58]

Marketing:

Marketing for the film included $20 million spent by Disney for advertising as well as advertisers such as Burger King, Pepsico, Coca-Cola, and Payless ShoeSource paying $125 million in tied promotions for the film.[66] A marketing consultant reflected on the promotion: "This will be a killer deal. How can a kid, sitting through a one-and-a-half-hour movie with an army of recognizable toy characters, not want to own one?"[67] Despite this, the consumer products arm of Disney was slow to see the potential of Toy Story early on.[58] When the Thanksgiving release date was announced in January 1995, many toy companies were accustomed to having eighteen months to two years of runway time, and passed on the project. In February 1995, Disney took the idea to Toy Fair, a toy industry trade show in New York. There, a Toronto-based company with a factory based in China, Thinkaway Toys, became interested. Although Thinkaway was a small player in the industry, mainly producing toy banks in the form of film characters, it was able to scoop up the worldwide master license for Toy Story toys simply because no one else wanted it.[68] Buena Vista Home Video put a trailer for the film on seven million copies of the VHS re-release of Cinderella; the Disney Channel ran a television special on the making of Toy Story; Walt Disney World in Orlando held a daily Toy Story parade at Disney-MGM Studios.[56]

Marketing for the film included $20 million spent by Disney for advertising as well as advertisers such as Burger King, Pepsico, Coca-Cola, and Payless ShoeSource paying $125 million in tied promotions for the film.[66] A marketing consultant reflected on the promotion: "This will be a killer deal. How can a kid, sitting through a one-and-a-half-hour movie with an army of recognizable toy characters, not want to own one?"[67] Despite this, the consumer products arm of Disney was slow to see the potential of Toy Story early on.[58] When the Thanksgiving release date was announced in January 1995, many toy companies were accustomed to having eighteen months to two years of runway time, and passed on the project. In February 1995, Disney took the idea to Toy Fair, a toy industry trade show in New York. There, a Toronto-based company with a factory based in China, Thinkaway Toys, became interested. Although Thinkaway was a small player in the industry, mainly producing toy banks in the form of film characters, it was able to scoop up the worldwide master license for Toy Story toys simply because no one else wanted it.[68] Buena Vista Home Video put a trailer for the film on seven million copies of the VHS re-release of Cinderella; the Disney Channel ran a television special on the making of Toy Story; Walt Disney World in Orlando held a daily Toy Story parade at Disney-MGM Studios.[56]

It was screenwriter Joss Whedon's idea to incorporate Barbie as a character who would rescue Woody and Buzz in the film's final act.[69] The idea was dropped after Mattel objected and refused to license the toy. Producer Ralph Guggenheim claimed that Mattel did not allow the use of the toy as "They [Mattel] philosophically felt girls who play with Barbie dolls are projecting their personalities onto the doll. If you give the doll a voice and animate it, you're creating a persona for it that might not be every little girl's dream and desire."[38] Hasbro likewise refused to license G.I. Joe (mainly because Sid was going to blow one up), but they did license Mr. Potato Head.[38] The only toy in the movie that was not currently in production was Slinky Dog, which was discontinued since the 1970s. When designs for Slinky were sent to Betty James (Richard James's Wife) she said that Pixar had improved the toy and that it was "cuter" than the original.[70]

3-D re-release:

On October 2, 2009, the film was re-released in Disney Digital 3-D.[71] The film was also released with Toy Story 2 as a double feature for a two-week run[72] which was extended due to its success.[73][74] In addition, the film's second sequel, Toy Story 3, was also released in the 3-D format.[71] Lasseter commented on the new 3-D re-release:

On October 2, 2009, the film was re-released in Disney Digital 3-D.[71] The film was also released with Toy Story 2 as a double feature for a two-week run[72] which was extended due to its success.[73][74] In addition, the film's second sequel, Toy Story 3, was also released in the 3-D format.[71] Lasseter commented on the new 3-D re-release:

"The Toy Story films and characters will always hold a very special place in our hearts and we're so excited to be bringing this landmark film back for audiences to enjoy in a whole new way thanks to the latest in 3-D technology. With Toy Story 3 shaping up to be another great adventure for Buzz, Woody and the gang from Andy's room, we thought it would be great to let audiences experience the first two films all over again and in a brand new way."[75]

Translating the film into 3-D involved revisiting the original computer data and virtually placing a second camera into each scene, creating left-eye and right-eye views needed to achieve the perception of depth.[76] Unique to computer animation, Lasseter referred to this process as "digital archaeology."[76] The process took four months, as well as an additional six months for the two films to add the 3-D. The lead stereographer Bob Whitehill oversaw this process and sought to achieve an effect that affected the emotional storytelling of the film:

"When I would look at the films as a whole, I would search for story reasons to use 3-D in different ways. In 'Toy Story, for instance, when the toys were alone in their world, I wanted it to feel consistent to a safer world. And when they went out to the human world, that's when I really blew out the 3-D to make it feel dangerous and deep and overwhelming."[76]

Unlike other countries, the United Kingdom received the films in 3-D as separate releases. Toy Story was released on October 2, 2009. Toy Story 2 was instead released January 22, 2010.[77] The re-release performed well at the box office, opening with $12,500,000 in its opening weekend, placing at the third position after Zombieland and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs.[78] The double feature grossed $30,714,027 in its five-week release.[78]

Reception:

"Yes, we worry about what the critics say. Yes, we worry about what the opening box office is going to be. Yes, we worry about what the final box office is going to be. But really, the whole point why we do what we do is to entertain our audiences. The greatest joy I get as a filmmaker is to slip into an audience for one of our movies anonymously, and watch people watch our film. Because people are 100 percent honest when they're watching a movie. And to see the joy on people's faces, to see people really get into our films...to me is the greatest reward I could possibly get."

"Yes, we worry about what the critics say. Yes, we worry about what the opening box office is going to be. Yes, we worry about what the final box office is going to be. But really, the whole point why we do what we do is to entertain our audiences. The greatest joy I get as a filmmaker is to slip into an audience for one of our movies anonymously, and watch people watch our film. Because people are 100 percent honest when they're watching a movie. And to see the joy on people's faces, to see people really get into our films...to me is the greatest reward I could possibly get."

—John Lasseter, reflecting on the impact of the film[79]Ever since its original 1995 release, Toy Story received universal acclaim from critics; Review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes (which gave the movie an "Extremely Fresh" rating) reports that 100% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 74 reviews, with an average score of 9/10. The critical consensus is: As entertaining as it is innovative, Toy Story kicked off Pixar's unprecedented run of quality pictures, reinvigorating animated film in the process. The film is Certified Fresh.[7] At the website Metacritic, which utilizes a normalized rating system, the film earned a "universal acclaim" level rating of 92/100 based on 16 reviews by mainstream critics.[6] Reviewers hailed the film for its computer animation, voice cast, and ability to appeal to numerous age groups.

Leonard Klady of Variety commended the animation's "... razzle-dazzle technique and unusual look. The camera loops and zooms in a dizzying fashion that fairly takes one's breath away."[80] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times compared the film's innovative animation to Disney's Who Framed Roger Rabbit, saying "Both movies take apart the universe of cinematic visuals, and put it back together again, allowing us to see in a new way."[81] Due to the film's animation, Richard Corliss of TIME claimed that it was "... the year's most inventive comedy."[82]

The voice cast was also praised by various critics. Susan Wloszczyna of USA Today approved of the selection of Hanks and Allen for the lead roles.[83] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times stated that "Starting with Tom Hanks, who brings an invaluable heft and believability to Woody, Toy Story is one of the best voiced animated features in memory, with all the actors ... making their presences strongly felt."[84] Several critics also recognized the film's ability to appeal to various age groups, specifically children and adults.[81][85] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly wrote: "It has the purity, the ecstatic freedom of imagination, that's the hallmark of the greatest children's films. It also has the kind of spring-loaded allusive prankishness that, at times, will tickle adults even more than it does kids."[86]

In 1995, Toy Story was named eighth in TIME's list of the best ten films of 1995.[87] In 2011, TIME named it one of "The 25 All-TIME Best Animated Films".[88] It also ranks at number 99 in Empire magazines list of the 500 Greatest Films of All Time, and as the highest ranked animated movie.[89]

In 2003, the Online Film Critics Society ranked the film as the greatest animated film of all time.[90] In 2007, the Visual Effects Society named the film 22nd in its list of the "Top 50 Most Influential Visual Effects Films of All Time".[91] In 2005 the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry, one of five films to be selected in its first year of eligibility.[92] The film is ranked ninety-ninth on the AFI's list of the hundred greatest American films of all time.[93][94][95] It was one of only two animated films on the list, the other being Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It was also sixth best in the animation genre on AFI's 10 Top 10.

Director Terry Gilliam would praise the film as "a work of genius. It got people to understand what toys are about. They're true to their own character. And that's just brilliant. It's got a shot that's always stuck with me, when Buzz Lightyear discovers he's a toy. He's sitting on this landing at the top of the staircase and the camera pulls back and he's this tiny little figure. He was this guy with a massive ego two seconds before... and it's stunning. I'd put that as one of my top ten films, period."[96]

Box office performance:

Prior to the film's release, executive producer and Apple Computer founder Steve Jobs stated "If Toy Story is a modest hit—say $75 million at the box office—we'll [Pixar and Disney] both break even. If it gets $100 million, we'll both make money. But if it's a real blockbuster and earns $200 million or so at the box office, we'll make good money, and Disney will make a lot of money." Upon its release on November 22, 1995, Toy Story managed to gross more than $350 million worldwide.[55] Disney chairman Michael Eisner stated "I don't think either side thought Toy Story would turn out as well as it has. The technology is brilliant, the casting is inspired, and I think the story will touch a nerve. Believe me, when we first agreed to work together, we never thought their first movie would be our 1995 holiday feature, or that they could go public on the strength of it."[55] Toy Story's first five days of domestic release (on Thanksgiving weekend), earned the film $39,071,176.[97] The film placed first in the weekend's box office with $29,140,617.[1] The film maintained its number one position at the domestic box office for the following two weekends. Toy Story was the highest grossing domestic film in 1995, beating Batman Forever and Apollo 13 (also starring Tom Hanks).[98] At the time of its release, it was the third highest grossing animated film after The Lion King (1994) and Aladdin (1992).[26] When not considering inflation, Toy Story is 96th on the list of the highest grossing domestic films of all time.[99] The film had gross receipts of $191,796,233 in the U.S. and Canada and $170,162,503 in international markets for a total of $361,958,736 worldwide.[1] At the time of its release, the film ranked 17th highest grossing film (unadjusted) in domestic money, and worldwide it was the 21st highest grossing film.

Prior to the film's release, executive producer and Apple Computer founder Steve Jobs stated "If Toy Story is a modest hit—say $75 million at the box office—we'll [Pixar and Disney] both break even. If it gets $100 million, we'll both make money. But if it's a real blockbuster and earns $200 million or so at the box office, we'll make good money, and Disney will make a lot of money." Upon its release on November 22, 1995, Toy Story managed to gross more than $350 million worldwide.[55] Disney chairman Michael Eisner stated "I don't think either side thought Toy Story would turn out as well as it has. The technology is brilliant, the casting is inspired, and I think the story will touch a nerve. Believe me, when we first agreed to work together, we never thought their first movie would be our 1995 holiday feature, or that they could go public on the strength of it."[55] Toy Story's first five days of domestic release (on Thanksgiving weekend), earned the film $39,071,176.[97] The film placed first in the weekend's box office with $29,140,617.[1] The film maintained its number one position at the domestic box office for the following two weekends. Toy Story was the highest grossing domestic film in 1995, beating Batman Forever and Apollo 13 (also starring Tom Hanks).[98] At the time of its release, it was the third highest grossing animated film after The Lion King (1994) and Aladdin (1992).[26] When not considering inflation, Toy Story is 96th on the list of the highest grossing domestic films of all time.[99] The film had gross receipts of $191,796,233 in the U.S. and Canada and $170,162,503 in international markets for a total of $361,958,736 worldwide.[1] At the time of its release, the film ranked 17th highest grossing film (unadjusted) in domestic money, and worldwide it was the 21st highest grossing film.

Accolades:

Main article: List of Pixar awards and nominations: Toy Story

The film won and was nominated for various other awards including a Kids' Choice Award, MTV Movie Award, and a BAFTA Award, among others. John Lasseter received an Academy Special Achievement Award in 1996 "for the development and inspired application of techniques that have made possible the first feature-length computer-animated film."[100] The film was nominated for three Academy Awards, two to Randy Newman for Best Music—Original Song, for "You've Got a Friend in Me", and Best Music—Original Musical or Comedy Score.[101] It was also nominated for Best Writing—Screenplay Written for the Screen for the work by Joel Cohen, Pete Docter, John Lasseter, Joe Ranft, Alec Sokolow, Andrew Stanton, and Joss Whedon making Toy Story the first animated film to be nominated for a writing award.[101]

Main article: List of Pixar awards and nominations: Toy Story

The film won and was nominated for various other awards including a Kids' Choice Award, MTV Movie Award, and a BAFTA Award, among others. John Lasseter received an Academy Special Achievement Award in 1996 "for the development and inspired application of techniques that have made possible the first feature-length computer-animated film."[100] The film was nominated for three Academy Awards, two to Randy Newman for Best Music—Original Song, for "You've Got a Friend in Me", and Best Music—Original Musical or Comedy Score.[101] It was also nominated for Best Writing—Screenplay Written for the Screen for the work by Joel Cohen, Pete Docter, John Lasseter, Joe Ranft, Alec Sokolow, Andrew Stanton, and Joss Whedon making Toy Story the first animated film to be nominated for a writing award.[101]

Toy Story won eight Annie Awards, including "Best Animated Feature". Animator Pete Docter, director John Lasseter, musician Randy Newman, producers Bonnie Arnold and Ralph Guggenheim, production designer Ralph Eggleston, and writers Joel Cohen, Alec Sokolow, Andrew Stanton, and Joss Whedon all won awards for "Best Individual Achievement" in their respective fields for their work on the film. The film also won "Best Individual Achievement" in technical achievement.[102]

Toy Story was nominated for two Golden Globes, one for "Best Motion Picture—Comedy/Musical", and one for "Best Original Song—Motion Picture" for Randy Newman's "You've Got a Friend in Me".[103] At both the Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards and the Kansas City Film Critics Circle, the film won "Best Animated Film".[104][105] Toy Story is also among the top ten in the BFI list of the 50 films you should see by the age of 14, and the highest placed (at #99) animated film in Empire's list of "500 Greatest Movie of All Time".[106] In 2005 Toy Story, along with Toy Story 2 was voted the 4th greatest cartoon in Channel 4's 100 Greatest Cartoons poll, behind The Simpsons, Tom and Jerry and South Park.

Home media:

Toy Story was released on VHS and Laserdisc on October 29, 1996, with no bonus material. In the first week of release VHS rentals totaled $5.1 million, debuting Toy Story as the number one video for the week.[107] Over 21.5 million VHS copies were sold in the first year.[108] Disney released a deluxe edition widescreen LaserDisc 4-disc box set on December 18, 1996. On January 11, 2000, it was released on VHS in the Gold Classic Collection series with the bonus short, Tin Toy, which sold two million copies.[108] Its first DVD release was on October 17, 2000, in a two-pack with Toy Story 2. This release was later available individually on March 20, 2001. Also on October 17, 2000, a 3-disc "Ultimate Toy Box" set was released, featuring Toy Story, Toy Story 2, and a third disc of bonus materials.[108] The DVD two-pack, The Ultimate Toy Box set, the Gold Classic Collection VHS and DVD and the original DVD were put in the Disney Vault. On September 6, 2005, a 2-disc "10th Anniversary Edition" was released featuring much of the bonus material from the "Ultimate Toy Box", including a retrospective special with John Lasseter, a home theater mix, as well as a new picture.[109] This DVD went back in the Disney Vault on January 31, 2009, along with Toy Story 2. The 10th Anniversary release was the last version of Toy Story to be released before taken out of the Disney Vault lineup, along with Toy Story 2. Also on September 6, 2005, a bare-bones UMD of Toy Story was released for the Sony PlayStation Portable.

Toy Story was released on VHS and Laserdisc on October 29, 1996, with no bonus material. In the first week of release VHS rentals totaled $5.1 million, debuting Toy Story as the number one video for the week.[107] Over 21.5 million VHS copies were sold in the first year.[108] Disney released a deluxe edition widescreen LaserDisc 4-disc box set on December 18, 1996. On January 11, 2000, it was released on VHS in the Gold Classic Collection series with the bonus short, Tin Toy, which sold two million copies.[108] Its first DVD release was on October 17, 2000, in a two-pack with Toy Story 2. This release was later available individually on March 20, 2001. Also on October 17, 2000, a 3-disc "Ultimate Toy Box" set was released, featuring Toy Story, Toy Story 2, and a third disc of bonus materials.[108] The DVD two-pack, The Ultimate Toy Box set, the Gold Classic Collection VHS and DVD and the original DVD were put in the Disney Vault. On September 6, 2005, a 2-disc "10th Anniversary Edition" was released featuring much of the bonus material from the "Ultimate Toy Box", including a retrospective special with John Lasseter, a home theater mix, as well as a new picture.[109] This DVD went back in the Disney Vault on January 31, 2009, along with Toy Story 2. The 10th Anniversary release was the last version of Toy Story to be released before taken out of the Disney Vault lineup, along with Toy Story 2. Also on September 6, 2005, a bare-bones UMD of Toy Story was released for the Sony PlayStation Portable.

The film was available on Blu-ray for the first time in a Special Edition Combo Pack which included two discs, one Blu-ray copy of the movie, and another DVD copy of the movie. This combo-edition was released on March 23, 2010, along with its sequel.[110] There was a DVD-only re-release on May 11, 2010.[111] Another "Ultimate Toy Box," packaging the Combo Pack with those of both sequels, became available on November 2, 2010. On November 1, 2011, along with the DVD and Blu-ray release of Cars 2, Toy Story and the other two films were released on each Blu-ray/Blu-ray 3D/DVD/Digital Copy combo pack (4 discs each for the first two films, and 5 for the third film). They were also be released on Blu-ray 3D in a complete trilogy box set.

Impact and legacy:Toy Story had a large impact on the film industry with its innovative computer animation. After the film's debut, various industries were interested in the technology used for the film. Graphics chip makers desired to compute imagery similar to the film's animation for personal computers; game developers wanted to learn how to replicate the animation for video games; and robotics researchers were interested in building artificial intelligence into their machines that compared to the lifelike characters in the film.[112] Various authors have also compared the film to an interpretation of Don Quixote as well as humanism.[113][114] In addition, Toy Story left an impact with its catchphrase "To Infinity and Beyond", sequels, and software, among others.

"To Infinity and Beyond"

Buzz Lightyear's classic line "To Infinity and Beyond" has seen usage not only on T-shirts, but among philosophers and mathematical theorists as well.[115][116][117] Lucia Hall of The Humanist linked the film's plot to an interpretation of humanism. She compared the phrase to "All this and heaven, too", indicating one who is happy with a life on Earth as well as having an afterlife.[114] In 2008, during STS-124 astronauts took an action figure of Buzz Lightyear into space on the Discovery Space Shuttle as part of an educational experience for students while stressing the catchphrase. The action figure was used for experiments in zero-g.[118] It was reported in 2008 that a father and son had continually repeated the phrase to help them keep track of each other while treading water for 15 hours in the Atlantic Ocean.[119] The phrase occurs in the lyrics of Beyonce's 2008 song "Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)", during the bridge.

Buzz Lightyear's classic line "To Infinity and Beyond" has seen usage not only on T-shirts, but among philosophers and mathematical theorists as well.[115][116][117] Lucia Hall of The Humanist linked the film's plot to an interpretation of humanism. She compared the phrase to "All this and heaven, too", indicating one who is happy with a life on Earth as well as having an afterlife.[114] In 2008, during STS-124 astronauts took an action figure of Buzz Lightyear into space on the Discovery Space Shuttle as part of an educational experience for students while stressing the catchphrase. The action figure was used for experiments in zero-g.[118] It was reported in 2008 that a father and son had continually repeated the phrase to help them keep track of each other while treading water for 15 hours in the Atlantic Ocean.[119] The phrase occurs in the lyrics of Beyonce's 2008 song "Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)", during the bridge.

Sequels, shows, and spin-offs:

Main articles: Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3

Toy Story has spawned two sequels: Toy Story 2 (1999) and Toy Story 3 (2010). Initially, the first sequel to Toy Story was going to be a direct-to-video release, with development beginning in 1996.[120] However, after the cast from Toy Story returned and the story was considered to be better than that of a direct-to-video release, it was announced in 1998 that the sequel would see a theatrical release.[121] The sequel saw the return of the majority of the voice cast from Toy Story, and the film focuses on rescuing Woody after he is stolen at a yard sale. The film was equally well received by critics, earning a rare 100% approval rating at Rotten Tomatoes, based on 125 reviews.[122] At Metacritic, the film earned a favorable rating of 88/100 based on 34 reviews.[123] The film's widest release was 3,257 theaters and it grossed $485,015,179 worldwide, becoming the second-most successful animated film after The Lion King at the time of its release.[124][125]

Main articles: Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3

Toy Story has spawned two sequels: Toy Story 2 (1999) and Toy Story 3 (2010). Initially, the first sequel to Toy Story was going to be a direct-to-video release, with development beginning in 1996.[120] However, after the cast from Toy Story returned and the story was considered to be better than that of a direct-to-video release, it was announced in 1998 that the sequel would see a theatrical release.[121] The sequel saw the return of the majority of the voice cast from Toy Story, and the film focuses on rescuing Woody after he is stolen at a yard sale. The film was equally well received by critics, earning a rare 100% approval rating at Rotten Tomatoes, based on 125 reviews.[122] At Metacritic, the film earned a favorable rating of 88/100 based on 34 reviews.[123] The film's widest release was 3,257 theaters and it grossed $485,015,179 worldwide, becoming the second-most successful animated film after The Lion King at the time of its release.[124][125]

Toy Story 3 centers on the toys being accidentally donated to a day-care center when their owner Andy is preparing to go to college.[126][127] Again the majority of the cast from the prior two films returned. It was the first film in the franchise to be released in 3-D for its first run, though the first two films, which were originally released in 2-D, were re-released in 3-D in 2009 as a double feature.[126] Like its predecessors, Toy Story 3 received enormous critical acclaim, earning a 99% approval rating from Rotten Tomatoes.[128] It also grossed more than $1 billion worldwide, making it the highest-grossing animated film to date.[129]

In November 1996, the Disney on Ice: Toy Story ice show opened which featured the voices of the cast as well as the music by Randy Newman.[130] In April 2008, the Disney Wonder cruise ship launched Toy Story: The Musical shows on its cruises.[131]

Toy Story also led to a spin-off direct-to-video animated film, Buzz Lightyear of Star Command: The Adventure Begins, as well as the animated television series Buzz Lightyear of Star Command.[132] The film and series followed Buzz Lightyear and his friends at Star Command as they uphold justice across the galaxy. Although the film was criticized for not using the same animation as in Toy Story and Toy Story 2, it sold three million VHS and DVDs in its first week of release.[133][134] The series ran for 65 episodes.

There were also short films before Cars 2 titled Hawaiian Vacation, centering around Barbie and Ken on vacation in Bonnie's room, and the The Muppets entitled Small Fry, centering on Buzz being left in a fast-food restaurant.

Software and merchandise:

Disney's Animated Storybook: Toy Story and Disney's Activity Center: Toy Story were released for Windows and Mac.[135] Disney's Animated Storybook: Toy Story was the best selling software title of 1996, selling over 500,000 copies.[136] Two console video games were released for the film: the Toy Story video game, for the Sega Genesis, Super Nintendo Entertainment System, Game Boy, and PC as well as Toy Story Racer, for the PlayStation (which contains elements from Toy Story 2).[137] Pixar created original animations for all of the games, including fully animated sequences for the PC titles.

Disney's Animated Storybook: Toy Story and Disney's Activity Center: Toy Story were released for Windows and Mac.[135] Disney's Animated Storybook: Toy Story was the best selling software title of 1996, selling over 500,000 copies.[136] Two console video games were released for the film: the Toy Story video game, for the Sega Genesis, Super Nintendo Entertainment System, Game Boy, and PC as well as Toy Story Racer, for the PlayStation (which contains elements from Toy Story 2).[137] Pixar created original animations for all of the games, including fully animated sequences for the PC titles.

Toy Story had a large promotion prior to its release, leading to numerous tie-ins with the film including images on food packaging.[67] A variety of merchandise was released during the film's theatrical run and its initial VHS release including toys, clothing, and shoes, among other things.[138] When an action figure for Buzz Lightyear and Sheriff Woody was created it was initially ignored by retailers. However, after over 250,000 figures were sold for each character prior to the film's release, demand continued to expand, eventually reaching over 25 million units sold by 2007.[79]

Theme park attractions:

Toy Story and its sequels have inspired multiple attractions at the theme parks of Walt Disney World and Disneyland:

Toy Story and its sequels have inspired multiple attractions at the theme parks of Walt Disney World and Disneyland: