|

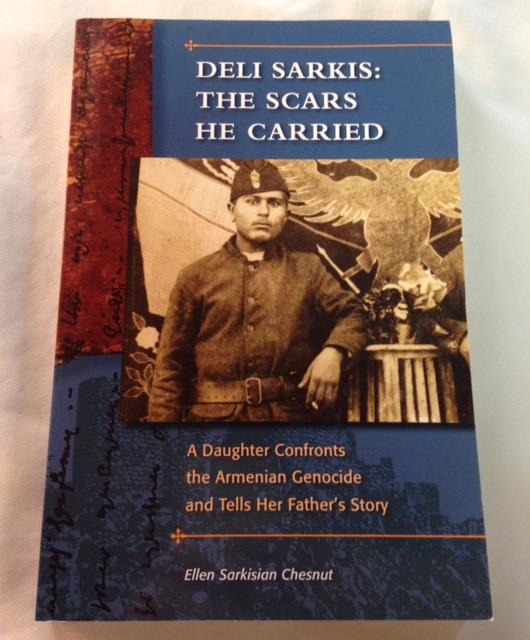

Chesnut Sarkisian, Ellen. "Deli Sarkis: The Scars He Carried" Minneapolis, MN: Two Harbors Press, 2014, 186 pages, with maps and photographs. Signed by the author copy.

|

Author tells story of her father’s survival during the Armenian Genocide 1915-23. Deli Sarkis or “Crazy” Sarkis in Turkish (he made up his name later when enlisting into Greek army) was ten-years-old when deported with his family from village of Keramet near Lake Iznik. From 1,200 inhabitants of the village only 40-45 would survived. Perhaps deportee must be “crazy” to survive the horrors of the deportation, all the killings and tortures, hunger and thirst, and total despair, the events and scenes truly unimaginable that only eyewitness could recall. “The gendarmes were still guarding us, but now we were completely encircled by ferocious looking Arabs. I remember how terribly poor they appeared as they stared at our possessions, our children, and young women. Then, almost as if they responded to an invisible signal to attack, they let out blood-curdling cries and, lifting above their heads terrifying metal rods, they began hurriedly moving through our convoy and smashing our young and older men with these awful weapons…so many in the convoy were dying or losing their minds. It was here that I observed a five-or-six-year-old boy, arms outstretched, moving around in circles and chirping like a lost bird…my mother had given me coins to swallow one at a time. When I was able to crap out a coin, we would buy bread from Arab villagers. Mostly our ‘diet’ consisted of raw frogs, raw fish, turtles, and snakes.” (pp. 50, 51). In 1922, Sarkis enlisted in Greek army fighting with the Turks and survived the massacre of the Greek and Armenian population of Smyrna. “I was asked much later which experience had been worse for me: the massacres and deportations into the wasteland of Syria or the burning and destruction of the population and city of Smyrna. Without hesitation, I would have to say Smyrna. I don’t think anyone can imagine the heartrending scenes that I witnessed…My cousin Krikor survived the burning of Smyrna as I did. Later, while living with relatives in France, he lost his mind and died in an asylum.” (p. 91).

The burning of Smyrna was ordered by Kemal Pasha Ataturk, future president of Turkey. “When the Turkish Republic was created in 1923 and Ataturk came to power…very few people could read the alphabet with its Arabic script…He called on the Armenian expert on the Turkish language, Hagop Martayan, who had been born in Turkey in 1895, graduated from Robert College in 1915, and was at that time living in Bulgaria. Martayan, in the 1930s, replaced the Ottoman script with a phonetic variant of the Latin. It was now possible for many more people to learn how to read. Ataturk also changed the man’s name to Dilacar, which means ‘tongue opener’ in Turkish, making it impossible for many in that country to know that an Armenian had transformed their language.” (p. 154). |

|

|

|

|