|

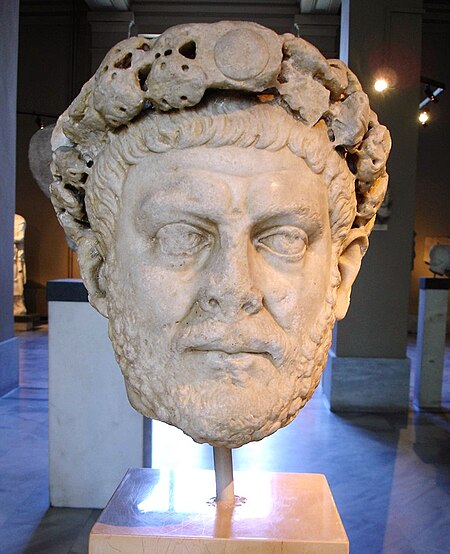

Diocletian - Roman Emperor: 284-305 A.D.

Bronze Antoninianus 21mm (3.34 grams) Heraclea mint: 295-297 A.D.

Reference: RIC 13a (VI, Heraclea), S 3510

IMPCCVALDIOCLETIANVSPFAVG - Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right.

CONCORDIAMILITVM Exe: HЄ - Diocletian

standing right on left, receiving Victory

on globe

from Jupiter to right, holding scepter.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Diocletian (Latin:

Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus Augustus;

c. 22 December 244 - 3 December 311), was a

Roman Emperor

from 284 to 305. Born to a family of low status in the

Roman province of Dalmatia

, Diocletian rose

through the ranks of the military to become cavalry commander to the Emperor

Carus

. After the deaths of Carus and his son

Numerian

on campaign in Persia, Diocletian was

proclaimed Emperor. The title was also claimed by Carus' other surviving son,

Carinus

, but Diocletian defeated him in the

Battle of the Margus

. Diocletian's reign

stabilized the Empire and marks the end of the

Crisis of the Third Century

. He appointed

fellow officer Maximian

Augustus

his senior co-emperor in 285.

of low status in the

Roman province of Dalmatia

, Diocletian rose

through the ranks of the military to become cavalry commander to the Emperor

Carus

. After the deaths of Carus and his son

Numerian

on campaign in Persia, Diocletian was

proclaimed Emperor. The title was also claimed by Carus' other surviving son,

Carinus

, but Diocletian defeated him in the

Battle of the Margus

. Diocletian's reign

stabilized the Empire and marks the end of the

Crisis of the Third Century

. He appointed

fellow officer Maximian

Augustus

his senior co-emperor in 285.

Diocletian delegated further on 1 March 293, appointing

Galerius

and

Constantius

as

Caesars

, junior co-emperors. Under this "Tetrarchy",

or "rule of four", each emperor would rule over a quarter-division of the

Empire. Diocletian secured the Empire's borders and purged it of all threats to

his power. He defeated the

Sarmatians

and

Carpi

during several campaigns between 285 and

299, the

Alamanni

in 288, and usurpers in

Egypt

between 297 and 298. Galerius, aided by

Diocletian, campaigned successfully against

Sassanid Persia

, the Empire's traditional

enemy. In 299 he sacked their capital,

Ctesiphon

. Diocletian led the subsequent

negotiations and achieved a lasting and favorable peace. Diocletian separated

and enlarged the Empire's civil and military services and reorganized the

Empire's provincial divisions, establishing the largest and most

bureaucratic

government in the history of the

Empire. He established new administrative centers in

Nicomedia

,

Mediolanum

,

Antioch

, and

Trier

, closer to the Empire's frontiers than

the traditional capital at Rome had been. Building on third-century trends

towards absolutism

, he styled himself an autocrat,

elevating himself above the Empire's masses with imposing forms of court

ceremonies and architecture. Bureaucratic and military growth, constant

campaigning, and construction projects increased the state's expenditures and

necessitated a comprehensive tax reform. From at least 297 on, imperial taxation

was standardized, made more equitable, and levied at generally higher rates.

Not all of Diocletian's plans were successful: the

Edict on Maximum Prices

(301), his attempt

to curb inflation

via

price controls

, was counterproductive and

quickly ignored. Although effective while he ruled, Diocletian's Tetrarchic

system collapsed after his abdication under the competing dynastic claims of

Maxentius

and

Constantine

, sons of Maximian and Constantius

respectively. The

Diocletianic Persecution

(303-11), the Empire's

last, largest, and bloodiest official persecution of

Christianity

, did not destroy the Empire's

Christian community; indeed, after 324 Christianity became the empire's

preferred religion under its first Christian emperor,

Constantine

.

In spite of his failures, Diocletian's reforms fundamentally changed the

structure of Roman imperial government and helped stabilize the Empire

economically and militarily, enabling the Empire to remain essentially intact

for another hundred years despite being near the brink of collapse in

Diocletian's youth. Weakened by illness, Diocletian left the imperial office on

1 May 305, and became the only Roman emperor to voluntarily abdicate the

position. He lived out his retirement in

his palace

on the Dalmatian coast, tending to

his vegetable gardens. His palace eventually became the core of the modern-day

city of

Split

.

Early life

Diocletian was probably born near

Salona

in

Dalmatia

(Solin

in modern Croatia

), some time around 244. His parents

named him Diocles, or possibly Diocles Valerius. The modern historian

Timothy Barnes

takes his official birthday, 22

December, as his actual birthdate. Other historians are not so certain. Diocles'

parents were of low status, and writers critical of him claimed that his father

was a scribe

or a

freedman

of the senator Anullinus, or even that

Diocles was a freedman himself. The first forty years of his life are mostly

obscure. The

Byzantine

chronicler

Joannes Zonaras

states that he was

Dux

Moesiae

, a commander of forces on the lower

Danube

. The often-unreliable

Historia Augusta

states that he served in

Gaul, but this account is not corroborated by other sources and is ignored by

modern historians of the period.

Death of Numerian

Emperor Carus

' death left his unpopular sons Numerian

and Carinus as the new Augusti. Carinus quickly made his way to Rome from

Gaul and arrived by January 284. Numerian lingered in the east. The Roman

withdrawal from Persia was orderly and unopposed. The

Sassanid

king

Bahram II

could not field an army against them

as he was still struggling to establish his authority. By March 284, Numerian

had only reached Emesa (Homs)

in

Syria

; by November, only Asia Minor. In Emesa

he was apparently still alive and in good health: he issued the only extant

rescript

in his name there, but after he left

the city, his staff, including the prefect

Aper

, reported that he suffered from an

inflammation of the eyes. He traveled in a closed coach from then on. When the

army reached Bithynia

, some of the soldiers smelled an odor

emanating from the coach. They opened its curtains and inside they found

Numerian dead.

Aper officially broke the news in

Nicomedia

(İzmit)

in November. Numerianus' generals and tribunes called a council for the

succession, and chose Diocles as Emperor, in spite of Aper's attempts to garner

support. On 20 November 284, the army of the east gathered on a hill 5

kilometres (3.1 mi) outside Nicomedia. The army unanimously saluted Diocles as

their new Augustus, and he accepted the purple imperial vestments. He raised his

sword to the light of the sun and swore an oath disclaiming responsibility for

Numerian's death. He asserted that Aper had killed Numerian and concealed it. In

full view of the army, Diocles drew his sword and killed Aper. According to the

Historia Augusta, he quoted from

Virgil

while doing so. Soon after Aper's death,

Diocles changed his name to the more Latinate "Diocletianus", in full Gaius

Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus.

Conflict with Carinus

After his accession, Diocletian and Lucius Caesonius Bassus were named as

consuls and assumed the

fasces

in place of Carinus and Numerianus.

Bassus was a member of a

senatorial

family from

Campania

, a former consul and proconsul of

Africa, chosen by Probus for signal distinction. He was skilled in areas of

government where Diocletian presumably had no experience. Diocletian's elevation

of Bassus as consul symbolized his rejection of Carinus' government in Rome, his

refusal to accept second-tier status to any other emperor, and his willingness

to continue the long-standing collaboration between the Empire's senatorial and

military aristocracies. It also tied his success to that of the Senate, whose

support he would need in his advance on Rome.

Diocletian was not the only challenger to Carinus' rule: the usurper

M. Aurelius Julianus

, Carinus' corrector

Venetiae, took control of northern

Italy

and

Pannonia

after Diocletian's accession. Julianus

minted coins from the mint at Siscia (Sisak,

Croatia) declaring himself as Emperor and promising freedom. It was all good

publicity for Diocletian, and it aided in his portrayal of Carinus as a cruel

and oppressive tyrant. Julianus' forces were weak, however, and were handily

dispersed when Carinus' armies moved from Britain to northern Italy. As leader

of the united East, Diocletian was clearly the greater threat. Over the winter

of 284-85, Diocletian advanced west across the

Balkans

. In the spring, some time before the

end of May, his armies met Carinus' across the river Margus (Great

Morava) in

Moesia

. In modern accounts, the site has been

located between the Mons Aureus (Seone, west of

Smederevo

) and

Viminacium

, near modern

Belgrade

, Serbia.

Despite having the stronger army, Carinus held the weaker position. His rule

was unpopular, and it was later alleged that he had mistreated the Senate and

seduced his officers' wives. It is possible that

Flavius Constantius

, the governor of Dalmatia

and Diocletian's associate in the household guard, had already defected to

Diocletian in the early spring. When the

Battle of the Margus

began, Carinus' prefect

Aristobulus also defected. In the course of the battle, Carinus was killed by

his own men. Following Diocletian's victory, both the western and the eastern

armies acclaimed him Augustus. Diocletian exacted an oath of allegiance from the

defeated army and departed for Italy.

Early rule

Diocletian may have become involved in battles against the

Quadi

and

Marcomanni

immediately after the Battle of the

Margus. He eventually made his way to northern Italy and made an imperial

government, but it is not known whether he visited the city of Rome at this

time. There is a contemporary issue of coins suggestive of an imperial

adventus

(arrival) for the city, but some

modern historians state that Diocletian avoided the city, and that he did so on

principle, as the city and its Senate were no longer politically relevant to the

affairs of the Empire and needed to be taught as much. Diocletian dated his

reign from his elevation by the army, not the date of his ratification by the

Senate, following the practice established by Carus, who had declared the

Senate's ratification a useless formality. If Diocletian ever did enter Rome

shortly after his accession, he did not stay long; he is attested back in the

Balkans by 2 November 285, on campaign against the

Sarmatians

.

Diocletian replaced the

prefect

of Rome with his consular colleague

Bassus. Most officials who had served under Carinus, however, retained their

offices under Diocletian. In an act of clementia denoted by the

epitomator

Aurelius Victor

as unusual, Diocletian did not

kill or depose Carinus' traitorous praetorian prefect and consul Ti. Claudius

Aurelius Aristobulus, but confirmed him in both roles. He later gave him the

proconsulate of Africa and the rank of urban prefect. The other figures who

retained their offices might have also betrayed Carinus.

Maximian made

co-emperor

Maximian's consistent loyalty to Diocletian proved an important

component of the Tetrarchy's early successes.

The assassinations of

Aurelian

and Probus demonstrated that sole

rulership was dangerous to the stability of the Empire. Conflict boiled in every

province, from Gaul to Syria, Egypt to the lower Danube. It was too much for one

person to control, and Diocletian needed a lieutenant. At some time in 285 at

Mediolanum

(Milan),

Diocletian raised his fellow-officer

Maximian

to the office of

Caesar

, making him co-emperor.

The concept of dual rulership was nothing new to the Roman Empire.

Augustus

, the first Emperor, had nominally

shared power with his colleagues, and more formal offices of co-Emperor had

existed from

Marcus Aurelius

on. Most recently, the emperor

Carus and his sons had ruled together, albeit unsuccessfully. Diocletian was in

a less comfortable position than most of his predecessors, as he had a daughter,

Valeria, but no sons. His co-ruler had to be from outside his family, raising

the question of trust. Some historians state that Diocletian adopted Maximian as

his filius Augusti, his "Augustan son", upon his appointment to the

throne, following the precedent of some previous emperors. This argument has not

been universally accepted.

The relationship between Diocletian and Maximian was quickly couched in

religious terms. Around 287 Diocletian assumed the title Iovius, and

Maximian assumed the title Herculius. The titles were probably meant to

convey certain characteristics of their associated leaders. Diocletian, in

Jovian

style, would take on the dominating

roles of planning and commanding; Maximian, in

Herculian

mode, would act as Jupiter's

heroic subordinate. For all their religious connotations, the

emperors were not "gods" in the tradition of the

Imperial cult

-although they may have been

hailed as such in Imperial

panegyrics

. Instead, they were seen as the

gods' representatives, effecting their will on earth. The shift from military

acclamation to divine sanctification took the power to appoint emperors away

from the army. Religious legitimization elevated Diocletian and Maximian above

potential rivals in a way military power and dynastic claims could not.

Conflict

with Sarmatia and Persia

After his acclamation, Maximian was dispatched to fight the rebel

Bagaudae

in Gaul. Diocletian returned to the

East, progressing slowly. By 2 November, he had only reached Citivas Iovia

(Botivo, near Ptuj

,

Slovenia

). In the Balkans during the autumn of

285, he encountered a tribe of

Sarmatians

who demanded assistance. The

Sarmatians requested that Diocletian either help them recover their lost lands

or grant them pasturage rights within the Empire. Diocletian refused and fought

a battle with them, but was unable to secure a complete victory. The nomadic

pressures of the

European Plain

remained and could not be solved

by a single war; soon the Sarmatians would have to be fought again.

Diocletian wintered in

Nicomedia

. There may have been a revolt in the

eastern provinces at this time, as he brought settlers from

Asia

to populate emptied farmlands in

Thrace

. He visited

Syria Palaestina

the following spring, His stay

in the East saw diplomatic success in the conflict with Persia: in 287,

Bahram II

granted him precious gifts, declared

open friendship with the Empire, and invited Diocletian to visit him. Roman

sources insist that the act was entirely voluntary.

Around the same time, perhaps in 287, Persia relinquished claims on

Armenia

and recognized Roman authority over

territory to the west and south of the Tigris. The western portion of Armenia

was incorporated into the Empire and made a province.

Tiridates III

,

Arsacid

claimant to the Armenian throne and

Roman client, had been disinherited and forced to take refuge in the Empire

after the Persian conquest of 252-53. In 287, he returned to lay claim to the

eastern half of his ancestral domain and encountered no opposition. Bahram II's

gifts were widely recognized as symbolic of a victory in the ongoing

conflict with Persia

, and Diocletian was hailed

as the "founder of eternal peace". The events might have represented a formal

end to Carus' eastern campaign, which probably ended without an acknowledged

peace. At the conclusion of discussions with the Persians, Diocletian

re-organized the Mesopotamian frontier and fortified the city of

Circesium

(Buseire, Syria) on the

Euphrates

.

Maximian made

Augustus

Maximian's campaigns were not proceeding as smoothly. The Bagaudae had been

easily suppressed, but

Carausius

, the man he had put in charge of

operations against Saxon

and

Frankish

pirates

on the

Saxon Shore

, had begun keeping the goods seized

from the pirates for himself. Maximian issued a death-warrant for his larcenous

subordinate. Carausius fled the Continent, proclaimed himself Augustus, and

agitated Britain and northwestern Gaul into open revolt against Maximian and

Diocletian. Spurred by the crisis, on 1 April 286, Maximian took up the title of

Augustus

. His appointment is unusual in that it

was impossible for Diocletian to have been present to witness the event. It has

even been suggested that Maximian usurped the title and was only later

recognized by Diocletian in hopes of avoiding civil war. This suggestion is

unpopular, as it is clear that Diocletian meant for Maximian to act with a

certain amount of independence.

Maximian realized that he could not immediately suppress the rogue commander,

so in 287 he campaigned solely against tribes beyond the

Rhine

instead. The following spring, as

Maximian prepared a fleet for an expedition against Carausius, Diocletian

returned from the East to meet Maximian. The two emperors agreed on a joint

campaign against the

Alamanni

. Diocletian invaded Germania through

Raetia while Maximian progressed from Mainz. Each emperor burned crops and food

supplies as he went, destroying the Germans' means of sustenance. The two men

added territory to the Empire and allowed Maximian to continue preparations

against Carausius without further disturbance. On his return to the East,

Diocletian managed what was probably another rapid campaign against the

resurgent Sarmatians. No details survive, but surviving inscriptions indicate

that Diocletian took the title Sarmaticus Maximus after 289.

In the East, Diocletian engaged in diplomacy with desert tribes in the

regions between Rome and Persia. He might have been attempting to persuade them

to ally themselves with Rome, thus reviving the old, Rome-friendly,

Palmyrene

sphere of influence

, or simply attempting to

reduce the frequency of their incursions. No details survive for these events.

Some of the princes of these states were Persian client kings, a disturbing fact

in light of increasing tensions with the Sassanids. In the West, Maximian lost

the fleet built in 288 and 289, probably in the early spring of 290. The

panegyrist

who refers to the loss suggests that

its cause was a storm, but this might simply be the an attempt to conceal an

embarrassing military defeat. Diocletian broke off his tour of the Eastern

provinces soon thereafter. He returned with haste to the West, reaching Emesa by

10 May 290, and Sirmium on the Danube by 1 July 290.

Diocletian met Maximian in Milan in the winter of 290-91, either in late

December 290 or January 291. The meeting was undertaken with a sense of solemn

pageantry. The Emperors spent most of their time in public appearances. It has

been surmised that the ceremonies were arranged to demonstrate Diocletian's

continuing support for his faltering colleague. A deputation from the Roman

Senate met with the Emperors, renewing its infrequent contact with the Imperial

office. The choice of Milan over Rome further snubbed the capital's pride. But

then it was already a long established practice that Rome itself was only a

ceremonial capital, as the actual seat of the Imperial administration was

determined by the needs of defense. Long before Diocletian,

Gallienus

(r. 253-68) had chosen Milan as the

seat of his headquarters. If the panegyric detailing the ceremony implied that

the true center of the Empire was not Rome, but where the Emperor sat ("...the

capital of the Empire appeared to be there, where the two emperors met"), it

simply echoed what had already been stated by the historian

Herodian

in the early third century: "Rome is

where the emperor is". During the meeting, decisions on matters of politics and

war were probably made in secret. The Augusti would not meet again until 303.

Tetrarchy

Foundation of the

Tetrarchy

Triumphal Arch of the Tetrarchy,

Sbeitla

,

Tunisia

Some time after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of

the war against Carausius from Maximian to

Constantius Chlorus

, a former governor of

Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to

Aurelian

's campaigns against

Zenobia

(272-73). He was Maximian's praetorian

prefect in Gaul, and the husband to Maximian's daughter,

Theodora

. On 1 March 293 at Milan, Maximian

gave Constantius the office of Caesar. In the spring of 293, in either

Philippopolis (Plovdiv,

Bulgaria

) or Sirmium, Diocletian would do the

same for Galerius

, husband to Diocletian's daughter

Valeria, and perhaps Diocletian's praetorian prefect. Constantius was assigned

Gaul and Britain. Galerius was assigned Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and

responsibility for the eastern borderlands.

This arrangement is called the Tetrarchy, from a

Greek

term meaning "rulership by four". The

Tetrarchic Emperors were more or less sovereign in their own lands, and they

travelled with their own imperial courts, administrators, secretaries, and

armies. They were joined by blood and marriage; Diocletian and Maximian now

styled themselves as brothers. The senior co-Emperors formally adopted Galerius

and Constantius as sons in 293. These relationships implied a line of

succession. Galerius and Constantius would become Augusti after the departure of

Diocletian and Maximian. Maximian's son

Maxentius

and Constantius' son

Constantine

would then become Caesars. In

preparation for their future roles, Constantine and Maxentius were taken to

Diocletian's court in Nicomedia.

Conflict in

the Balkans and Egypt

Diocletian spent the spring of 293 traveling with Galerius from Sirmium (Sremska

Mitrovica,

Serbia

) to

Byzantium

(Istanbul,

Turkey

). Diocletian then returned to Sirmium,

where he would remain for the following winter and spring. He campaigned against

the Sarmatians again in 294, probably in the autumn, and won a victory against

them. The Sarmatians' defeat kept them from the Danube provinces for a long

time. Meanwhile, Diocletian built forts north of the Danube, at

Aquincum

(Budapest,

Hungary

), Bononia (Vidin,

Bulgaria), Ulcisia Vetera, Castra Florentium, Intercisa (Dunaújváros,

Hungary), and Onagrinum (Begeč,

Serbia). The new forts became part of a new defensive line called the Ripa

Sarmatica. In 295 and 296 Diocletian campaigned in the region again, and won

a victory over the Carpi in the summer of 296. Afterwards, during 299 and 302,

as Diocletian was then residing in the East, it was Galerius' turn to campaign

victoriously on the Danube. By the end of his reign, Diocletian had secured the

entire length of the Danube, provided it with forts, bridgeheads, highways, and

walled towns, and sent fifteen or more legions to patrol the region; an

inscription at

Sexaginta Prista

on the Lower Danube extolled

restored tranquilitas at the region. The defense came at a heavy cost,

but was a significant achievement in an area difficult to defend.

Galerius, meanwhile, was engaged during 291-293 in disputes in

Upper Egypt

, where he suppressed a regional

uprising. He would return to Syria in 295 to fight the revanchist Persian

Empire. Diocletian's attempts to bring the Egyptian tax system in line with

Imperial standards stirred discontent, and a revolt swept the region after

Galerius' departure. The usurper

L. Domitius Domitianus

declared himself

Augustus in July or August 297. Much of Egypt, including

Alexandria

, recognized his rule. Diocletian

moved into Egypt to suppress him, first putting down rebels in the

Thebaid

in the autumn of 297, then moving on to

besiege Alexandria. Domitianus died in December 297, by which time Diocletian

had secured control of the Egyptian countryside. Alexandria, whose defense was

organized under Diocletian's former

corrector

Aurelius Achilleus

, held out until a later

date, probably March 298.

Bureaucratic affairs were completed during Diocletian's stay: a census took

place, and Alexandria, in punishment for its rebellion, lost the ability to mint

independently. Diocletian's reforms in the region, combined with those of

Septimus Severus

, brought Egyptian

administrative practices much closer to Roman standards. Diocletian travelled

south along the Nile the following summer, where he visited

Oxyrhynchus

and

Elephantine

. In Nubia, he made peace with the

Nobatae

and

Blemmyes

tribes. Under the terms of the peace

treaty Rome's borders moved north to

Philae

and the two tribes received an annual

gold stipend. Diocletian left Africa quickly after the treaty, moving from Upper

Egypt in September 298 to Syria in February 299. He met up with Galerius in

Mesopotamia.

War with Persia

Invasion, counterinvasion

In 294, Narseh

, a son of Shapur who had been passed

over for the Sassanid succession, came to power in Persia. Narseh eliminated

Bahram III

, a young man installed in the wake

of Bahram II's death in 293. In early 294, Narseh sent Diocletian the customary

package of gifts between the empires, and Diocletian responded with an exchange

of ambassadors. Within Persia, however, Narseh was destroying every trace of his

immediate predecessors from public monuments. He sought to identify himself with

the warlike kings

Ardashir

(r. 226-41) and

Shapur I

(r. 241-72), who had sacked Roman

Antioch and skinned the Emperor

Valerian

(r. 253-260) to decorate his war

temple.

Narseh declared war on Rome in 295 or 296. He appears to have first invaded

western Armenia, where he seized the lands delivered to Tiridates in the peace

of 287. Narseh moved south into Roman Mesopotamia in 297, where he inflicted a

severe defeat on Galerius in the region between Carrhae (Harran,

Turkey) and Callinicum (Ar-Raqqah,

Syria) (and thus, the historian

Fergus Millar

notes, probably somewhere on the

Balikh River

). Diocletian may or may not have

been present at the battle, but he quickly divested himself of all

responsibility. In a public ceremony at Antioch, the official version of events

was clear: Galerius was responsible for the defeat; Diocletian was not.

Diocletian publicly humiliated Galerius, forcing him to walk for a mile at the

head of the Imperial caravan, still clad in the purple robes of the Emperor.

Galerius was reinforced, probably in the spring of 298, by a new contingent

collected from the Empire's Danubian holdings. Narseh did not advance from

Armenia and Mesopotamia, leaving Galerius to lead the offensive in 298 with an

attack on northern Mesopotamia via Armenia. It is unclear if Diocletian was

present to assist the campaign; he might have returned to Egypt or Syria. Narseh

retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius' force, to Narseh's disadvantage; the

rugged Armenian terrain was favorable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid

cavalry. In two battles, Galerius won major victories over Narseh. During the

second encounter

, Roman forces seized Narseh's

camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius continued moving down the

Tigris, and took the Persian capital Ctesiphon before returning to Roman

territory along the Euphrates.

Peace negotiations

Narseh sent an ambassador to Galerius to plead for the return of his wives

and children in the course of the war, but Galerius had dismissed him. Serious

peace negotiations began in the spring of 299. The magister memoriae

(secretary) of Diocletian and Galerius, Sicorius Probus, was sent to Narseh to

present terms. The conditions of the resulting

Peace of Nisibis

were heavy: Armenia returned

to Roman domination, with the fort of Ziatha as its border;

Caucasian Iberia

would pay allegiance to Rome

under a Roman appointee; Nisibis, now under Roman rule, would become the sole

conduit for trade between Persia and Rome; and Rome would exercise control over

the five satrapies between the Tigris and Armenia: Ingilene, Sophanene (Sophene),

Arzanene (Aghdznik),

Corduene

(Carduene), and Zabdicene (near modern

Hakkâri

, Turkey). These regions included the

passage of the Tigris through the

Anti-Taurus

range; the

Bitlis

pass, the quickest southerly route into

Persian Armenia; and access to the

Tur Abdin

plateau.

A stretch of land containing the later strategic strongholds of Amida (Diyarbakır,

Turkey) and Bezabde came under firm Roman military occupation. With these

territories, Rome would have an advance station north of Ctesiphon, and would be

able to slow any future advance of Persian forces through the region. Many

cities east of the Tigris came under Roman control, including

Tigranokert

,

Saird

,

Martyropolis

,

Balalesa

,

Moxos

,

Daudia

, and Arzan - though under what status is

unclear. At the conclusion of the peace, Tiridates regained both his throne and

the entirety of his ancestral claim. Rome secured a wide zone of cultural

influence, which led to a wide diffusion of

Syriac Christianity

from a center at Nisibis in

later decades, and the eventual Christianization of Armenia.

Religious persecutions

Early persecutions

At the conclusion of the

Peace of Nisibis

, Diocletian and Galerius

returned to Syrian Antioch. At some time in 299, the Emperors took part in a

ceremony of sacrifice

and

divination

in an attempt to predict the future.

The haruspices

were unable to read the entrails of

the sacrificed animals and blamed Christians in the Imperial household. The

Emperors ordered all members of the court to perform a sacrifice to purify the

palace. The Emperors sent letters to the military command, demanding the entire

army perform the required sacrifices or face discharge. Diocletian was

conservative in matters of religion, a man faithful to the traditional Roman

pantheon and understanding of demands for religious purification, but

Eusebius

,

Lactantius

and

Constantine

state that it was Galerius, not

Diocletian, who was the prime supporter of the purge, and its greatest

beneficiary. Galerius, even more devoted and passionate than Diocletian, saw

political advantage in the politics of persecution. He was willing to break with

a government policy of inaction on the issue.

Antioch was Diocletian's primary residence from 299 to 302, while Galerius

swapped places with his Augustus on the Middle and Lower Danube. He visited

Egypt once, over the winter of 301-2, and issued a grain dole in Alexandria.

Following some public disputes with

Manicheans

, Diocletian ordered that the leading

followers of

Mani

be burnt alive along with their

scriptures. In a 31 March 302 rescript from Alexandria, he declared that

low-status Manicheans must be executed by the blade, and high-status Manicheans

must be sent to work in the quarries of Proconnesus (Marmara

Island, Turkey) or the mines of Phaeno in southern

Palestine

. All Manichean property was to be

seized and deposited in the imperial treasury. Diocletian found much to be

offended by in Manichean religion: its novelty, its alien origins, the way it

corrupted the morals of the Roman race, and its inherent opposition to

long-standing religious traditions. Manichaeanism was also supported by Persia

at the time, compounding religious dissent with international politics.

Excepting Persian support, the reasons he disliked Manichaenism were equally

applicable, if not more so, to Christianity, his next target.

Diocletian saw his work as that of a restorer, a figure of authority whose

duty it was to return the empire to peace, to recreate stability and justice

where barbarian hordes had destroyed it. He arrogated, regimented and

centralized political authority on a massive scale. In his policies, he enforced

an Imperial system of values on diverse and often unreceptive provincial

audiences. In the Imperial propaganda from the period, recent history was

perverted and minimized in the service of the theme of the Tetrarchs as

"restorers". Aurelian's achievements were ignored, the revolt of Carausius was

backdated to the reign of Gallienus, and it was implied that the Tetrarchs

engineered Aurelian's defeat of the

Palmyrenes

; the period between Gallienus and

Diocletian was effectively erased. The history of the empire before the

Tetrarchy was portrayed as a time of civil war, savage despotism, and imperial

collapse. In those inscriptions that bear their names, Diocletian and his

companions are referred to as "restorers of the whole world", men who succeeded

in "defeating the nations of the barbarians, and confirming the tranquility of

their world". Diocletian was written up as the "founder of eternal peace". The

theme of restoration was conjoined to an emphasis on the uniqueness and

accomplishments of the Tetrarchs themselves.

The cities where Emperors lived frequently in this period-Milan,

Trier

,

Arles

, Sirmium,

Serdica

,

Thessaloniki

, Nicomedia, and

Antioch

-were treated as alternate imperial

seats, to the exclusion of Rome and its senatorial elite. A new style of

ceremony was developed, emphasizing the distinction of the Emperor from all

other persons. The quasi-republican ideals of Augustus'

primus inter pares

were abandoned for all

but the Tetrarchs themselves. Diocletian took to wearing a gold crown and

jewels, and forbade the use of

purple cloth

to all but the Emperors. His

subjects were required to prostrate themselves in his presence (adoratio);

the most fortunate were allowed the privilege of kissing the hem of his robe (proskynesis,

προσκύνησις). Circuses and basilicas were designed to keep the face of the

Emperor perpetually in view, and always in a seat of authority. The emperor

became a figure of transcendent authority, a man beyond the grip of the masses.

His every appearance was stage-managed. This style of presentation was not

new-many of its elements were first seen in the reigns of Aurelian and

Severus-but it was only under the Tetrarchs that it was refined into an explicit

system.

Legacy

The historian

A.H.M. Jones

observed that "It is perhaps

Diocletian's greatest achievement that he reigned twenty-one years and then

abdicated voluntarily, and spent the remaining years of his life in peaceful

retirement." Diocletian was one of the few Emperors of the third and fourth

centuries to die naturally, and the first in the history of the Empire to retire

voluntarily. Once he retired, however, his Tetrarchic system collapsed. Without

the guiding hand of Diocletian, the Empire fell into civil wars. Stability

emerged after the defeat of Licinius by Constantine in 324. Under the Christian

Constantine, Diocletian was maligned. Constantine's rule, however, validated

Diocletian's achievements and the autocratic principle he represented: the

borders remained secure, in spite of Constantine's large expenditure of forces

during his civil wars; the bureaucratic transformation of Roman government was

completed; and Constantine took Diocletian's court ceremonies and made them even

more extravagant.

Constantine ignored those parts of Diocletian's rule that did not suit him.

Diocletian's policy of preserving a stable silver coinage was abandoned, and the

gold

solidus

became the Empire's primary

currency instead. Diocletian's

persecution of Christians

was repudiated and

changed to a policy of toleration and then favoritism. Christianity eventually

became the official religion in 381. Constantine would claim to have the same

close relationship with the Christian God as Diocletian claimed to have with

Jupiter. Most importantly, Diocletian's tax system and administrative reforms

lasted, with some modifications, until the advent of the Muslims in the 630s.

The combination of state autocracy and state religion was instilled in much of

Europe, particularly in the lands which adopted Orthodox Christianity.

In addition to his administrative and legal impact on history, the Emperor

Diocletian is considered to be the founder of the city of

Split

in modern-day

Croatia

. The city itself grew around the

heavily fortified

Diocletian's Palace

the Emperor had built in

anticipation of his retirement.

In

ancient Roman religion

and

myth

, Jupiter (Latin:

Iuppiter) or Jove is the

king of the gods

and the

god of sky

and

thunder

. Jupiter was the chief deity of Roman

state religion throughout the

Republican

and

Imperial

eras, until the Empire

came under Christian rule

. In

Roman mythology

, he negotiates with

Numa Pompilius

, the second

king of Rome

, to establish principles of Roman

religion such as sacrifice.

Jupiter is usually thought to have originated as a sky god. His identifying

implement is the

thunderbolt

, and his primary sacred animal is

the eagle, which held precedence over other birds in the taking of

auspices

and became one of the most common

symbols of the

Roman army

(see

Aquila

). The two emblems were often combined to

represent the god in the form of an eagle holding in its claws a thunderbolt,

frequently seen on Greek and Roman coins. As the sky-god, he was a divine

witness to oaths, the sacred trust on which justice and good government depend.

Many of his functions were focused on the

Capitoline

("Capitol Hill"), where the

citadel

was located. He was the chief deity of

the

early Capitoline Triad

with

Mars

and

Quirinus

. In the

later Capitoline Triad

, he was the central

guardian of the state with

Juno

and

Minerva

. His sacred tree was the oak.

The Romans regarded Jupiter as the

equivalent

of Greek

Zeus, and in

Latin literature

and

Roman art

, the myths and iconography of Zeus

are adapted under the name Iuppiter. In the Greek-influenced tradition,

Jupiter was the brother of

Neptune

and

Pluto

. Each presided over one of the three

realms of the universe: sky, the waters, and the underworld. The

Italic

Diespiter was also a sky god who

manifested himself in the daylight, usually but not always identified with

Jupiter. The

Etruscan

counterpart was

Tinia

and

Hindu

counterpart is

Indra

.

Jupiter and the state

The Romans believed that Jupiter granted them supremacy because they had

honoured him more than any other people had. Jupiter was "the fount of the

auspices

upon which the relationship of the

city with the gods rested." He personified the divine authority of Rome's

highest offices, internal organization, and external relations. His image in the

Republican

and

Imperial

Capitol bore

regalia

associated with

Rome's ancient kings

and the highest

consular

and

Imperial honours

.

The consuls swore their oath of office in Jupiter's name, and honoured him on

the annual

feriae

of the Capitol in September. To

thank him for his help (and to secure his continued support), they offered him a

white ox (bos mas) with gilded horns. A similar offering was made by

triumphal generals

, who surrendered the tokens

of their victory at the feet of Jupiter's statue in the Capitol. Some scholars

have viewed the triumphator as embodying (or impersonating) Jupiter in

the triumphal procession.

Jupiter's association with kingship and sovereignty was reinterpreted as

Rome's form of government changed. Originally,

Rome was ruled by kings

; after the monarchy was

abolished and the

Republic

established, religious prerogatives

were transferred to the patres, the

patrician ruling class

. Nostalgia for the

kingship (affectatio regni) was considered treasonous. Those suspected of

harbouring monarchical ambitions were punished, regardless of their service to

the state. In the 5th century BC, the triumphator

Furius Camillus

was sent into exile after he

drove a chariot with a team of four white horses (quadriga)-an

honour reserved for Jupiter himself. After the

Gallic occupation

ended and self-rule was

restored,

Manlius Capitolinus

took on regal pretensions

and was executed as a traitor by being cast from the

Tarpeian Rock

. His house on the Capitoline was

razed, and it was decreed that no patrician should ever be allowed to live

there. Capitoline Jupiter finds himself in a delicate position: he represents a

continuity of royal power from the

Regal period

, and confers power on the

magistrates

who pay their respects to him; at

the same time he embodies that which is now forbidden, abhorred, and

scorned.During the

Conflict of the Orders

, Rome's

plebeians

demanded the right to hold political

and religious office. During their first

secessio

(similar to a

general strike

), they withdrew from the city

and threatened to found their own. When they agreed to came back to Rome they

vowed the hill where they had retreated to Jupiter as symbol and guarantor of

the unity of the Roman res publica. Plebeians eventually became eligible

for all the

magistracies

and most priesthoods, but the high

priest of Jupiter (Flamen

Dialis) remained the preserve of patricians.

Flamen and

Flaminica Dialis

Jupiter was served by the patrician Flamen Dialis, the highest-ranking member

of the flamines

, a

college

of fifteen priests in the official

public cult of Rome, each of whom was devoted to a particular deity. His wife,

the Flaminica Dialis, had her own duties, and presided over the sacrifice of a

ram to Jupiter on each of the

nundinae

, the "market" days of a calendar

cycle, comparable to a week. The couple were required to marry by the exclusive

patrician ritual

confarreatio

, which included a sacrifice of

spelt

bread to Jupiter Farreus (from far,

"wheat, grain").

The office of Flamen Dialis was circumscribed by several unique ritual

prohibitions, some of which shed light on the sovereign nature of the god

himself. For instance, the flamen may remove his clothes or

apex

(his pointed hat) only when under a

roof, in order to avoid showing himself naked to the sky-that is, "as if under

the eyes of Jupiter" as god of the heavens. Every time the Flaminica saw a

lightningbolt or heard a clap of thunder (Jupiter's distinctive instrument), she

was prohibited from carrying on with her normal routine until she placated the

god.

Some privileges of the flamen of Jupiter may reflect the regal nature

of Jupiter: he had the use of the

curule chair

, and was the only priest (sacerdos)

who was preceded by a

lictor

and had a seat in the

senate

. Other regulations concern his ritual

purity and his separation from the military function; he was forbidden to ride a

horse or see the army outside the sacred boundary of Rome (pomerium).

Although he served the god who embodied the sanctity of the oath, it was not

religiously permissible (fas)

for the Dialis to swear an oath. He could not have contacts with anything dead

or connected with death: corpses, funerals, funeral fires, raw meat. This set of

restrictions reflects the fulness of life and absolute freedom that are features

of Jupiter.

Augurs

The augures publici,

augurs

were a college of sacerdotes who

were in charge of all inaugurations and of the performing of ceremonies known as

auguria. Their creation was traditionally ascribed to Romulus. They were

considered the only official interprets of Jupiter's will, thence they were

essential to the very existence of the Roman State as Romans saw in Jupiter the

only source of statal authority.

Fetials

The

fetials

were a college of 20 men devoted to the

religious administration of international affairs of state. Their task was to

preserve and apply the fetial law (ius fetiale), a complex set of

procedures aimed at ensuring the protection of the gods in Rome's relations with

foreign states.

Iuppiter Lapis

is the god under whose

protection they act, and whom the chief fetial (pater patratus) invokes

in the rite concluding a treaty. If a

declaration of war

ensues, the fetial calls

upon Jupiter and

Quirinus

, the heavenly, earthly and

chthonic

gods as witnesses of any potential

violation of the ius. He can then declare war within 33 days.

The action of the fetials falls under Jupiter's jurisdiction as the divine

defender of good faith. Several emblems of the fetial office pertain to Jupiter.

The silex was the stone used for the fetial sacrifice, housed in the

Temple of Iuppiter Feretrius

, as was their sceptre.

Sacred herbs (sagmina), sometimes identified as

vervain

, had to be taken from the nearby

(arx)citadel

for their ritual use.

Jupiter and religion in the secessions of the plebs

The role of Jupiter in the

conflict of the orders

is a reflection of the

religiosity of the Romans. Whereas the patricians were able to claim the support

of the supreme god quite naturally being the holders of the

auspices

of the State, the plebeians argued

that as Jupiter was the source of justice he was on their side since their cause

was just.

The first secession was caused by the excessive burden of debts that weighed

on the plebs. Because of the legal institute of the

nexum

a debtor could become a slave of his

creditor. The plebeians argued the debts had become unsustainable because of the

expenses of the wars wanted by the patricians. As the senate did not acceed to

the proposal of a total debt remission advanced by dictator and augur Manius

Valerius the plebs retired on the Mount Sacer, a hill located three Roman miles

to the North-northeast of Rome, past the the Nomentan bridge on river

Anio

. The place is windy and was usually the

site of rites of divination performed by haruspices. The senate in the end sent

a delegation composed of ten members with full powers of making a deal with the

plebs, of which were part

Menenius Agrippa

and Manius Valerius. It was

Valerius, according to the inscription found at Arezzo in 1688 and written on

the order of Augustus as well as other literary sources, that brought the plebs

down from the Mount, after the secessionists had consecrated it to Jupiter

Territor and built an altar (ara) on its summit. The fear of the

wrath of Jupiter was an important element in the solution of the crisis. The

consecration of the Mount probably referred to its summit only. The ritual

requested the participation of both an augur (presumably Manius Valerius

himself) and a pontifex.

The second secession was caused by the autocratic and arrogant behaviour of

the decemviri

who had been charged by the Roman

people with writing down the laws in use til then kept secret by the patrician

magistrates and the sacerdotes. All magistracies and the tribunes of the

plebs had resigned in advance. Their work resulted in the XII Tables, which

though concerned only private law. The plebs once again retreated to the Sacer

Mons: this act besides recalling the first secession was meant to seek the

protection of the supreme god. The secession ended with the resignation of the

decemviri and an amnesty for the rebellious soldiers who had deserted

from their camp near Mount Algidus abandoning the commanders. The amnesty was

granted by the senate and guaranteed by the pontifex maximus Quintus

Furius (Livy) (or Marcus Papirius) who also supervised the nomination of the new

tribunes of the plebs then gathered on the Aventine Hill. The role played by the

pontifex maximus in a situation of vacation of powers is a significant element

underlining the religious basis and character of the tribunicia potestas.

Myths and legends

A dominant line of scholarship has held that Rome lacked a body of myths in

its earliest period, or that this original mythology has been irrecoverably

obscured by the influence of the

Greek narrative tradition

.[29]

After the

Hellenization

of Roman culture, Latin

literature and iconography reinterpreted the myths of Zeus in depictions and

narratives of Jupiter. In the legendary history of Rome, Jupiter is often

connected to kings and kingship.

Birth

Jupiter was depicted as the twin of Juno in a statue at

Praeneste

that showed them nursed by

Fortuna Primigenia

. An inscription that is also

from Praeneste, however, says that Fortuna Primigenia was Jupiter's first-born

child. Jacqueline Champeaux sees this contradiction as the result of successive

different cultural and religious phases, in which a wave of influence coming

from the Hellenic world made Fortuna the daughter of Jupiter.[32]

The childhood of Zeus is an important theme in Greek religion, art and

literature, but there are only rare (or dubious) depictions of Jupiter as a

child.

Numa

Faced by a period of bad weather endangering the harvest during one early

spring, King

Numa

resorted to the scheme of asking the

advice of the god by evoking his presence.He succeeded through the help of Picus

and Faunus, whom he had imprisoned by making them drunk. The two gods (with a

charm) evoked Jupiter, who was forced to come down to earth at the Aventine

(hence named Iuppiter Elicius, according to Ovid). After Numa skilfully

avoided the requests of the god for human sacrifices, Jupiter agreed to his

request to know how lightning bolts are averted, asking only for the

substitutions Numa had mentioned: an onion bulb, hairs and a fish. Moreover,

Jupiter promised that at the sunrise of the following day he would give to Numa

and the Roman people pawns of the imperium. The following day, after

throwing three lightning bolts across a clear sky, Jupiter sent down from heaven

a shield. Since this shield had no angles, Numa named it ancile; because

in it resided the fate of the imperium, he had many copies made of it to

disguise the real one. He asked the smith

Mamurius Veturius

to make the copies, and gave

them to the Salii

. As his only reward, Mamurius expressed

the wish that his name be sung in the last of their carmina.[35]

Plutarch gives a slightly different version of the story, writing that the cause

of the miraculous drop of the shield was a plague and not linking it with the

Roman imperium.

Tullus Hostilius

Throughout his reign,

King Tullus

had a scornful attitude towards

religion. His temperament was warlike, and he disregarded religious rites and

piety. After conquering the

Albans

with the duel between the

Horatii and Curiatii

, Tullus destroyed

Alba Longa

and deported its inhabitants to

Rome. As Livy

tells the story, omens (prodigia)

in the form of a rain of stones occurred on the

Alban Mount

because the deported Albans had

disregarded their ancestral rites linked to the sanctuary of Jupiter. In

addition to the omens, a voice was heard requesting that the Albans perform the

rites. A plague followed and at last the king himself fell ill. As a

consequence, the warlike character of Tullus broke down; he resorted to religion

and petty, superstitious practices. At last, he found a book by Numa recording a

secret rite on how to evoke Iuppiter Elicius. The king attempted to

perform it, but since he executed the rite improperly the god threw a lightning

bolt which burned down of the king's house and killed Tullus.

Tarquinius the Elder

When approaching Rome (where Tarquin was heading to try his luck in politics

after unsuccessful attempts in his native

Tarquinii

), an eagle swooped down, removed his

hat, flew screaming in circles, replaced the hat on his head and flew away.

Tarquin's wife Tanaquil

interpreted this as a sign that he

would become king based on the bird, the quadrant of the sky from which it came,

the god who had sent it and the fact it touched his hat (an item of clothing

placed on a man's most noble part, the head).[38]

Cult

Emperor

Marcus Aurelius

, attended by his

family, offers sacrifice outside the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus

after his victories in Germany (late 2nd century AD).

Capitoline Museum

, Rome

Sacrifices

Sacrificial victims (hostiae)

offered to Jupiter were the oxen (castrated bull), the lamb (on the Ides, the

ovis idulis) and the

wether

(on the Ides of January).The animals

were required to be white. The question of the lamb's gender is unresolved;

while a lamb is generally male, for the vintage-opening festival the flamen

Dialis sacrificed a ewe

. This rule seems to have had many

exceptions, as the sacrifice of a ram on the

Nundinae

by the flaminica Dialis

demonstrates. During one of the crises of the

Punic Wars

, Jupiter was offered every animal

born that year.

Temples

Temple of

Capitoline Jupiter

The temple to

Jupiter Optimus Maximus

stood on the

Capitoline Hill

. Jupiter was worshiped there as

an individual deity, and with

Juno

and

Minerva

as part of the

Capitoline Triad

. The building was supposedly

begun by king

Tarquinius Priscus

, completed by the last king

(Tarquinius

Superbus) and inaugurated in the early days of the Roman Republic

(September 13, 509 BC). It was topped with the statues of four horses drawing a

quadriga

, with Jupiter as charioteer. A large

statue of Jupiter stood within; on festival days, its face was painted red. In

(or near) this temple was the Iuppiter Lapis: the

Jupiter Stone

, on which oaths could be sworn.

Jupiter's Capitoline Temple probably served as the architectural model for

his provincial temples. When Hadrian built

Aelia Capitolina

on the site of

Jerusalem

, a temple to Jupiter Capitolinus was

erected in the place of the destroyed

Temple in Jerusalem

.

Other temples in Rome

There were two temples in Rome dedicated to Iuppiter Stator; the first

one was built and dedicated in 294 BC by

Marcus Atilius Regulus

after the third Samnite

War. It was located on the Via Nova, below the Porta Mugonia,

ancient entrance to the Palatine. Legend has attributed its founding to Romulus.

There may have been an earlier shrine (fanum),

since the Jupiter's cult is attested epigraphically.

Ovid places the temple's dedication on June 27, but it is unclear

whether this was the original date, or the rededication after the restoration by

Augustus.

A second temple of Iuppiter Stator was built and dedicated by Quintus

Caecilus Metellus Macedonicus after his triumph in 146 BC near the

Circus Flaminius

. It was connected to the

restored temple of Iuno Regina with a

portico

(porticus Metelli).

Iuppiter Victor had a temple dedicated by

Quintus Fabius Maximus Gurges

during the third

Samnite War in 295 BC. Its location is unknown, but it may be on the Quirinal,

on which an inscription reading D]iovei Victore has been found, or on the

Palatine according to the Notitia in the Liber Regionum (regio X),

which reads: aedes Iovis Victoris. Either might have been dedicated on

April 13 or June 13 (days of Iuppiter Victor and of Iuppiter Invictus,

respectively, in Ovid's Fasti). Inscriptions from the imperial age have

revealed the existence of an otherwise-unknown temple of Iuppiter Propugnator

on the Palatine.Iuppiter

Latiaris and Feriae Latinae

The cult of Iuppiter Latiaris was the most ancient known cult of the

god:: it was practised since very remote times near the top of the Mons

Albanus on which the god was venerated as the high protector of the Latin

League under the hegemony of

Alba Longa

.

After the destruction of Alba by king Tullus Hostilius the cult was forsaken.

The god manifested his discontent through the prodigy of a rain of stones: the

commission sent by the Roman senate to inquire into it was also greeted by a

rain of stones and heard a loud voice from the grove on the summit of the mount

that requested the Albans to perform the religious service to the god according

to the rites of their country. In consequence of this event the Romans

instituted a festival of nine days (nundinae). However a plague ensued:

in the end Tullus Hostilius himself was affected and lastly killed by the god

with a lightningbolt. The festival was reestablished on its primitive site by

the last Roman king Tarquin the Proud under the leadership of Rome.

The

feriae Latinae

, or

Latiar

as they were known originally, were

the common festival (panegyris) of the so-called Priscan Latins and of

the Albans. Their restoration aimed at grounding Roman hegemony in this

ancestral religious tradition of the Latins. The original cult was reinstated

unchanged as is testified by some archaic features of the ritual: the exclusion

of wine from the sacrifice the offers of milk and cheese and the ritual use of

rocking among the games. Rocking is one of the most ancient rites mimicking

ascent to Heaven and is very widespread. At the Latiar the rocking took

place on a tree and the winner was of course the one who had swung the highest.

This rite was said to have been instituted by the Albans to commemorate the

disappearance of king

Latinus

, in the battle against

Mezentius

king of

Caere

: the rite symbolised a search for him

both on earth and in heaven. The rocking as well as the customary drinking of

milk was also considered to commemorate and ritually reinstate infancy.[58]

The Romans in the last form of the rite brought the sacrificial ox from Rome and

every participant was bestowed a portion of the meat, rite known as carnem

petere. Other games were held in every participant borough. In Rome a race

of chariots (quadrigae) was held starting from the Capitol: the winner

drank a liquor made with absynth. This competition has been compared to the

Vedic rite of the

vajapeya

: in it seventeen chariots run a phoney

race which must be won by the king in order to allow him to drink a cup of

madhu, i. e. soma. The feasting lasted for at least four days,

possibly six according to

Niebuhr

, one day for each of the six Latin and

Alban decuriae. According to different records 47 or 53 boroughs took

part in the festival (the listed names too differ in Pliny NH III 69 and

Dionysius of Halicarnassus AR V 61). The Latiar became an important

feature of Roman political life as they were

feriae conceptivae

, i. e. their date varied

each year: the consuls and the highest magistrates were required to attend

shortly after the beginning of the adminitration, originally on the Ides of

March: the Feriae usually took place in early April. They could not start

campaigning before its end and if any part of the games had been neglected or

performed unritually the Latiar had to be wholly repeated. The

inscriptions from the imperial age record the festival back to the time of the

decemvirs

. Wissowa remarks the inner linkage of

the temple of the Mons Albanus with that of the Capitol apparent in the common

association with the rite of the

triumph

: since 231 BC some triumphing

commanders had triumphed there first with the same legal features as in Rome.

Religious calendar

Ides

The

Ides

(the midpoint of the month, with a full

moon) was sacred to Jupiter, because on that day heavenly light shone day and

night. Some (or all) Ides were

Feriae

Iovis, sacred to Jupiter. On the

Ides, a white lamb (ovis idulis) was led along Rome's

Sacred Way

to the

Capitoline Citadel

and sacrificed to him.

Jupiter's two

epula Iovis

festivals fell on the Ides, as

did his temple foundation rites as Optimus Maximus, Victor,

Invictus and (possibly) Stator.

Nundinae

The

nundinae

recurred every ninth day, dividing

the calendar into a market cycle analogous to a week. The market days gave the

rural people (pagi)

the opportunity to sell in town and to be informed of religious and political

edicts, which were posted publicly for three days. According to tradition, these

festival days were instituted by the king

Servius Tullius

. The high priestess of Jupiter

(Flaminica

Dialis) sanctified the days by sacrificing a ram to Jupiter.

Festivals

During the

Republican era

, more

fixed holidays

on the Roman calendar were

devoted to Jupiter than to any other deity.

Viniculture and wine

Festivals of

viniculture

and wine were devoted to Jupiter,

since grapes were particularly susceptible to adverse weather.Dumézil describes

wine as a "kingly" drink with the power to inebriate and exhilarate, analogous

to the Vedic Soma

.

Three Roman festivals were connected with viniculture and wine.

The rustic Vinalia

altera on August 19 asked for good

weather for ripening the grapes before harvest. When the grapes were ripe, a

sheep was sacrificed to Jupiter and the flamen Dialis cut the first of

the grape harvest.

The Meditrinalia

on October 11 marked the end of

the grape harvest; the new wine was

pressed

, tasted and mixed with old wine[78]

to control fermentation. In the Fasti Amiternini, this festival is

assigned to Jupiter. Later Roman sources invented a goddess Meditrina,

probably to explain the name of the festival.

At the Vinalia

urbana on April 23, new wine was

offered to Jupiter Large quantities of it were poured into a ditch near the

temple of

Venus Erycina

, which was located on the

Capitol.

Regifugium and

Poplifugium

The Regifugium

("King's Flight") on February 24

has often been discussed in connection with the

Poplifugia

on July 5, a day holy to

Jupiter. The Regifugium followed the festival of Iuppiter

Terminus

(Jupiter of Boundaries) on

February 23. Later Roman

antiquarians

misinterpreted the Regifugium

as marking the expulsion of the monarchy, but the "king" of this festival may

have been the priest known as the

rex sacrorum

who ritually enacted the

waning and renewal of power associated with the

New Year

(March 1 in the old Roman calendar). A

temporary vacancy of power (construed as a yearly "interregnum")

occurred between the Regifugium on February 24 and the New Year on March

1 (when the lunar cycle was thought to coincide again with the solar cycle), and

the uncertainty and change during the two winter months were over. Some scholars

emphasize the traditional political significance of the day.

The Poplifugia ("Routing of Armies"), a day sacred to Jupiter, may

similarly mark the second half of the year; before the

Julian calendar reform

, the months were named

numerically,

Quintilis

(the fifth month) to December

(the tenth month).The Poplifugia was a "primitive military ritual" for

which the adult male population assembled for purification rites, after which

they ritually dispelled foreign invaders from Rome.

Epula Iovis

There were two festivals called epulum Iovis ("Feast of Jove"). One

was held on September 13, the anniversary of the foundation of Jupiter's

Capitoline temple. The other (and probably older) festival was part of the

Plebeian Games

(Ludi Plebei), and was

held on November 13.[90]

In the 3rd century BC, the epulum Iovis became similar to a

lectisternium

.

Ludi

The most ancient Roman games followed after one day (considered a dies

ater, or "black day", i. e. a day which was traditionally considered

unfortunate even though it was not nefas, see also article

Glossary of ancient Roman religion

) the two

Epula Iovis of September and November.

The games of September were named Ludi Magni; originally they were not

held every year, but later became the annual Ludi Romani and were held

in the

Circus Maximus

after a procession from the

Capitol. The games were attributed to Tarquinius Priscus, and linked to the cult

of Jupiter on the Capitol. Romans themselves acknowledged analogies with the

triumph

, which Dumézil thinks can be explained

by their common Etruscan origin; the magistrate in charge of the games dressed

as the triumphator and the

pompa circensis

resembled a triumphal

procession. Wissowa and Mommsen argue that they were a detached part of the

triumph on the above grounds (a conclusion which Dumézil rejects).

The Ludi Plebei took place in November in the

Circus Flaminius

.

Mommsen

argued that the epulum of the

Ludi Plebei was the model of the Ludi Romani, but Wissowa finds the evidence for

this assumption insufficient.The Ludi Plebei were probably established in

534 BC. Their association with the cult of Jupiter is attested by Cicero.

Larentalia

The feriae of December 23 were devoted to a major ceremony in honour

of Acca Larentia

(or Larentina), in which

some of the highest religious authorities participated (probably including the

Flamen Quirinalis

and the

pontiffs

). The

Fasti Praenestini

marks the day as feriae

Iovis, as does Macrobius. It is unclear whether the rite of parentatio

was itself the reason for the festival of Jupiter, or if this was another

festival which happened to fall on the same day. Wissowa denies their

association, since Jupiter and his flamen would not be involved with the

underworld

or the deities of death (or be

present at a funeral rite held at a gravesite).

Name and epithets

The Latin name Iuppiter originated as a

vocative compound

of the

Old Latin

vocative *Iou and pater

("father") and came to replace the Old Latin

nominative case

*Ious. Jove is a less

common

English

formation based on Iov-, the

stem of oblique cases of the Latin name.

Linguistic

studies identify the form *Iou-pater

as deriving from the

Indo-European

vocative compound *Dyēu-pəter

(meaning "O Father Sky-god"; nominative: *Dyēus-pətēr).

Older forms of the deity's name in Rome were Dieus-pater

("day/sky-father"), then Diéspiter. The 19th-century philologist

Georg Wissowa

asserted these names are

conceptually- and linguistically-connected to Diovis and Diovis Pater;

he compares the analogous formations Vedius-Veiove and fulgur

Dium, as opposed to fulgur Summanum (nocturnal lightning bolt) and

flamen Dialis (based on Dius, dies). The Ancient later viewed

them as entities separate from Jupiter. The terms are similar in etymology and

semantics (dies, "daylight" and Dius, "daytime sky"), but differ

linguistically. Wissowa considers the epithet Dianus noteworthy.[105][106]

Dieus is the etymological equivalent of

ancient Greece

's

Zeus and of the

Teutonics'

Ziu

(genitive Ziewes). The

Indo-European deity is the god from which the names and partially the theology

of Jupiter, Zeus and the

Indo-Aryan

Vedic

Dyaus Pita

derive or have developed.

The Roman practice of swearing by Jove to witness an oath in law courts is

the origin of the expression "by Jove!"-archaic, but still in use. The name of

the god was also adopted as the name of the planet

Jupiter

; the

adjective

"jovial"

originally described those born under the planet of

Jupiter

(reputed to be jolly, optimistic, and

buoyant in

temperament

).

Jove was the original namesake of Latin forms of the

weekday

now known in English as

Thursday

(originally called Iovis Dies in

Latin

). These became jeudi in

French

, jueves in

Spanish

, joi in

Romanian

, giovedì in

Italian

, dijous in

Catalan

, Xoves in

Galcian

, Joibe in

Friulian

, Dijóu in

Provençal

.

Major epithets

The epithets of a Roman god indicate his theological qualities. The study of

these epithets must consider their origins (the historical context of an

epithet's source).

Jupiter's most ancient attested forms of cult belong to the State cult: these

include the mount cult (see section above note n. 22). In Rome this cult

entailed the existence of particular sanctuaries the most important of which

were located on Mons Capitolinus (earlier Tarpeius). The mount had

two tops that were both destined to the discharge of acts of cult related to

Jupiter. The northern and higher top was the

arx

and on it was located the observation

place of the

augurs

(auguraculum)

and to it headed the monthly procession of the sacra Idulia.On the

southern top was to be found the most ancient sanctuary of the god: the shrine

of Iuppiter Feretrius allegedly built by Romulus, restored by Augustus.

The god here had no image and was represented by the sacred flintstone (silex).

The most ancient known rites, those of the spolia opima and of the

fetials

which connect Jupiter with Mars and

Quirinus are dedicated to Iuppiter Feretrius or Iuppiter Lapis.The

concept of the sky god was already overlapped with the ethical and political

domain since this early time. According to Wissowa and Dumézi Iuppiter Lapis

seems to be inseparable from Iuppiter Feretrius in whose tiny templet on

the Capitol the stone was lodged.

Another most ancient epithet is Lucetius: although the Ancient,

followed by some modern scholars as e. g. Wissowa,interpreted it as referred to

sunlight, the carmen Saliare shows that it refers to lightning.A further

confirmation of this interpretation is provided by the sacred meaning of

lightning which is reflected in the sensitivity of the flaminica Dialis

to the phenomenon. To the same atmospheric complex belongs the epithet

Elicius: while the ancient erudites thought it was connected to lightning,

it is in fact related to the opening of the rervoirs of rain, as is testified by

the ceremony of the Nudipedalia, meant to propitiate rainfall and devoted

to Jupiter. and the ritual of the

lapis manalis

, the stone which was brought

into the city through the Porta Capena and carried around in times of

draught, which was named Aquaelicium.[119]

Other early epithets connected with the atmospheric quality of Jupiter are

Pluvius, Imbricius, Tempestas, Tonitrualis,

tempestatium divinarum potens, Serenator, Serenus and,

referred to lightning, Fulgur, Fulgur Fulmen, later as nomen

agentis Fulgurator, Fulminator: the high antiquity of the cult is

testified by the neutre form Fulgur and the use of the term for the

bidental, the lightningwell digged on the spot hit by a lightningbolt.

A bronze statue of Jupiter, from the territory of the

Treveri

A group of epithets has been interpreted by Wissowa (and his followers) as a

reflection of the agricultural or warring nature of the god, some of which are

also in the list of eleven preserved by Augustine.The agricultural ones include

Opitulus, Almus, Ruminus, Frugifer, Farreus,

Pecunia, Dapalis, Epulo.Augustine gives an explanation of

the ones he lists which should reflect Varro's: Opitulus because he

brings opem (means, relief) to the needy, Almus because he

nourishes everything, Ruminus because he nourishes the living beings by

breastfeeding them, Pecunia because everything belongs to him. Dumézil

maintains the cult usage of these epithets is not documented and that the

epithet Ruminus, as Wissowa and Latte remarked, may not have the meaning given

by Augustine but it should be understood as part of a series including Rumina,

Ruminalis ficus, Iuppiter Ruminus, which bears the name of Rome

itself with an Etruscan vocalism preserved in inscriptions, series that would be