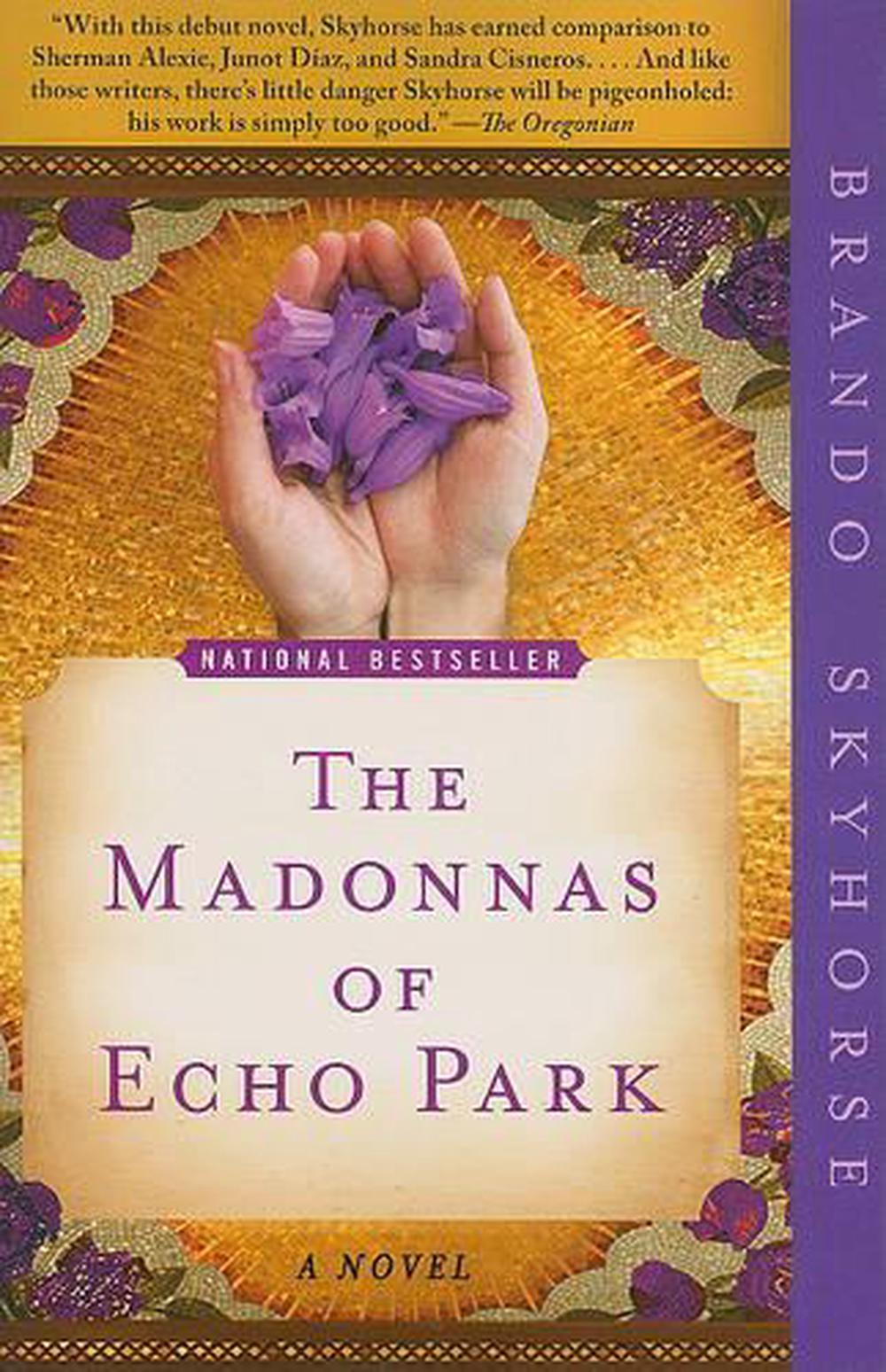

The Madonnas of Echo Park

by Brando Skyhorse

Explores the lives of those who shed their ethnic identity in pursuit of the American dream, highlighting a different character in each chapter, including Hector, a middle-aged day laborer who witnesses a murder, and his ex-wife Felicia, who survives a drive-by shooting.

Paperback

English

Brand New

Publisher Description

Reminiscent of Sherman Alexie and Sandra Cisneros, acclaimed author Brando Skyhorse's "engaging storytelling" (Vanity Fair) brings the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles to life in this poignant and propulsive novel following several generations of Mexican immigrants through their shifting cultural and physical landscapes.The Madonnas of Echo Park is both a grand mural of a Los Angeles neighborhood and an intimate glimpse into the lives of the men and women who struggle to lose their ethnic identity in the pursuit of the American dream. Each chapter summons a different voice--poetic, fierce, comic. We meet Hector, a day laborer who trolls the streets for work and witnesses a murder that pits his morality against his illegal status; his ex-wife Felicia, who narrowly survives a shooting and lands a cleaning job in a Hollywood Hills house as desolate as its owner; and young Aurora, who journeys through her now gentrified childhood neighborhood to discover her own history and her place in the land that all Mexican-Americans dream of, "the land that belongs to us again." Reminiscent of Luis Alberto Urrea and Dinaw Mengestu, The Madonnas of Echo Park is a brilliant and genuinely fresh view of American life.

Author Biography

Brando Skyhorse's debut novel, The Madonnas of Echo Park, won the 2011 PEN/Hemingway Award and the Sue Kaufman Award for First Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His memoir, Take This Man, was named one of Kirkus Reviews Best Nonfiction Books of 2014 and one of NBC News's 10 Best Latino Books of 2014. Skyhorse is a graduate of Stanford University and the MFA Writers' Workshop program at UC Irvine.

Review

Winnerof the Pen/Hemingway Award and the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction

Review Quote

Winnerof the Pen/Hemingway Award and the

Excerpt from Book

The Madonnas of Echo Park 2 The Blossoms of Los Feliz Spring is here and it makes my joints ache. All those jacaranda blossoms on the walk outside to sweep up. Jacaranda trees thrive in Los Angeles, like blondes and Mexicans. There''s no getting away from them, not even in my dreams. They''ve haunted me from childhood, when I believed a jacaranda tree would save me. Can you imagine such a thing, a tree saving a life? A silly girl thought so once. I''d been sent to my grandmother''s home in Chavez Ravine by a mother whose face I didn''t remember and whose cruelty Abuelita wouldn''t let me forget. The dirt road outside my abuelita ''s house led to an outdoor mercado and was covered with an amethyst sea of pulpy jacaranda that felt like old skin and calico under your bare feet. I''d collect sprays of young jacaranda, then run down the road with them, petals raining from my arms. When the white men came to build a baseball stadium for playing their games, they smoothed the land out like a sheet of paper to bring in their trucks and bulldozers that would destroy our homes. But there was a problem. The land was uncooperative and petty, swallowing contractors'' flatbed trucks and, I prayed, the workers themselves into sinkholes and collapsing earth atop surveyors'' flags. The jacaranda trees gave them the most trouble. They felled the mightiest bulldozers, which couldn''t tear them down without themselves being damaged. I thought that if I grew a jacaranda tree in my room, it would anchor our home to the land and we wouldn''t have to leave. I found a thin branch with several young sprays and set it in an old wooden batea . We had no running water, and the rainstorms that fled across the ravine didn''t give the dry, cracked ground a chance to soak up what poured out of the sky, so at night I''d slip out of my window barefoot to steal water from a neighbor''s well. I planted the batea in our swept-smooth dirt floor and waited for the spray to bear seeds whose roots would burrow deep into our ground. Two of the buds matured, plopping atop the water''s surface before they could open, but the rest weren''t growing fast enough and the sounds of the bulldozers kept getting closer and closer. I poured heavy gulps of water into the batea to get the other buds to bloom. I didn''t want to hurt them. I wanted to give them more of what I thought they needed. That night, a bad dream crept to my bed like a relative with filthy thoughts. I was a jacaranda blossom struggling to stay alive but whose violet color was dripping off my petals into a standing pool of water. But I was also me, laughing as I held the dying blossom by its bud under the water. I reached up with as much strength as I pushed my body down, drowning both my selves. There was the drop drop drop of running water, then a hard patter, then a shrieking roar, a scream pouring out of my mouth as I awoke coughing strands of spit on the side of the bed I shared with my abuelita. It was a vivid nightmare, one that revisits me, a persistent yet incurable sickness. Fumbling to the batea through the rough darkness, I saw that the other buds had shriveled up. Two jacaranda flowers were submerged underwater. I cradled them out of the vase to dry them, but their milk and seeds popped out as the flowers tore apart in my hands. My abuelita heard me crying and without asking where the water had come from told me that a drowning flower moves toward the water, not away from it. Its stem may be strong enough to stand on its own, but when its petals grow wet and heavy, they drag the flower back into the water and that causes it to die. Aurora Salazar, the last woman evicted from Chavez Ravine, learned this lesson when she was dragged by her wrists and ankles like a shackled butterfly off her land. And I would learn that lesson many years later working for Mrs. Calhoun. This is what women do, when they have an ocean of dreams but no water to put them in. Mrs. Calhoun lived in a large house on Avalon Street in Los Feliz with her husband, Rick, who had followed a story in the newspapers and on television about a drive-by shooting. In 1984, during my twelve-year-old daughter Aurora''s spring break, she and I had been standing for a group photo (which all the papers published) on a street corner when a car opened fire near the crowd. Neither of us had been in any actual danger, but because of the attention, I lost my job cleaning the offices of a law firm where I''d worked for four years as a "temp." Before Rick found me, I was looking for work on a street corner, 5th and San Pedro, near the Midnight Mission. Back then, my English was terrible and Skid Row was where, if you were a woman, needed work, and didn''t speak English, you''d gather in a group for the gabachos to come and hire you. We all had our own corners on Skid Row back then. 6th and Los Angeles, by the Greyhound station, was for junkies. 5th and San Julian was the park where whores would sell their time: twenty dollars for twenty minutes in a flophouse, or ten dollars for ten minutes in a Porta Potti the city put out for the homeless. And 5th and Pedro was where you went to hire day laborers and cleaning ladies. The women came from everywhere south, some as far away as Uruguay, each with her own Spanish dialect. The men had their own corner, across the street from ours. They weren''t there to defend us when we were harassed (or sometimes raped) by the bums who swarmed the area but to keep an eye on us while they drank, laughed, and wolf-whistled the gazelles, beanstalky white women in suits and sneakers who parked their cars in the cheap garages nearby. They turned those pendejos'' heads like compass needles, as if those girls'' tits and asses were magnetized. We had the dignity to wait in silence, yawning in the flat gray sharpness of dawn under a mist of milky amber streetlight. Standing in a straight line, arms folded across our chests like stop signs, we prepared ourselves for a long day of aching, mindless work by sharing a religious, rigorous, devotional quiet. When men want relief they hire a whore. When women want relief they hire a cleaning lady. And they did it the same way--first they examined our bodies. Could we reach the high shelves with the lead crystal without a stepladder? Were we able to fit into a crawl space and fish out their children''s toys? Were our culos big enough to cushion an accidental fall? They never looked us in the eye because they could see us performing those disgusting chores no decent woman would dream of asking another woman to do. Then they tried to negotiate the stingiest hourly rate, or tossed out a flat fee that always seemed too good to be true, and was; at their houses, you were asked in a polite but insistent voice to do "just one more" messy, humiliating job (digging through moist, rotten garbage for a missing earring they "thought" might have fallen in, or fishing a tampon out of a clogged toilet) before you earned your day''s freedom. The men were more direct, pulling up in large white windowless vans and snapping their fingers--"I need two plump, stocky ones and two that can squeeze into tight corners!"--like buying live chickens. I wasn''t the only American-born woman on this corner who never learned English. In Los Angeles, you could rent an apartment, buy groceries, cash checks, and socialize, all in Spanish. I tried going to the movies to learn English; at the theaters Downtown, Mexicans could come only on certain days and were "restricted" to the balcony. I snuck in whenever I could because I wanted to be more "American," and I thought these movies--"The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain!"--had the answer. Yet whatever English I pieced together dissolved when I walked into the harsh sunlight outside. When something really stumped me--paying taxes, for example--I asked for help. More Mexicans speak English than you imagine and understand it better than they let on. That''s how I met Hector, in church; he could already speak English but never had time to teach me. (I should have known a man who could speak two languages could live two different lives with two different women.) How could I find time to learn English, when I left my house at dusk like a vampire, working in empty, haunted offices all night? And some vampire I was, frightened by all those ghostly sounds in an office, like copy machines that powered on for no reason or phones that rang endlessly. Before sunrise, I scurried out the service entrance with a horseshoe back, clenched shoulders, callused feet, and skin reeking of ammonia. That''s why Rick''s letter arriving when it did gave me faith we were not destined to live our lives as victims. The papers painted Aurora and me as tragic near-martyrs, symbols of a community the city had forgotten. Aurora couldn''t face her classmates because of this and some incident at school that she started telling me about, then stopped when she told me I''d gotten the details wrong (someone called her "a dirty Mexican"). After the shooting, she stopped telling me anything, became a sour and sullen stranger in my home. She changed schools and talked to me even less, but she was still my translator and my negotiator when I went to meet Rick. Cards and letters flooded our mailbox, but Rick had written on the most handsome stationery that he was looking for a cleaning lady (or better yet, a houseboy), and if I wasn''t interested, would I inquire in the neighborhood in exchange for a "finder''s fee"?

Details