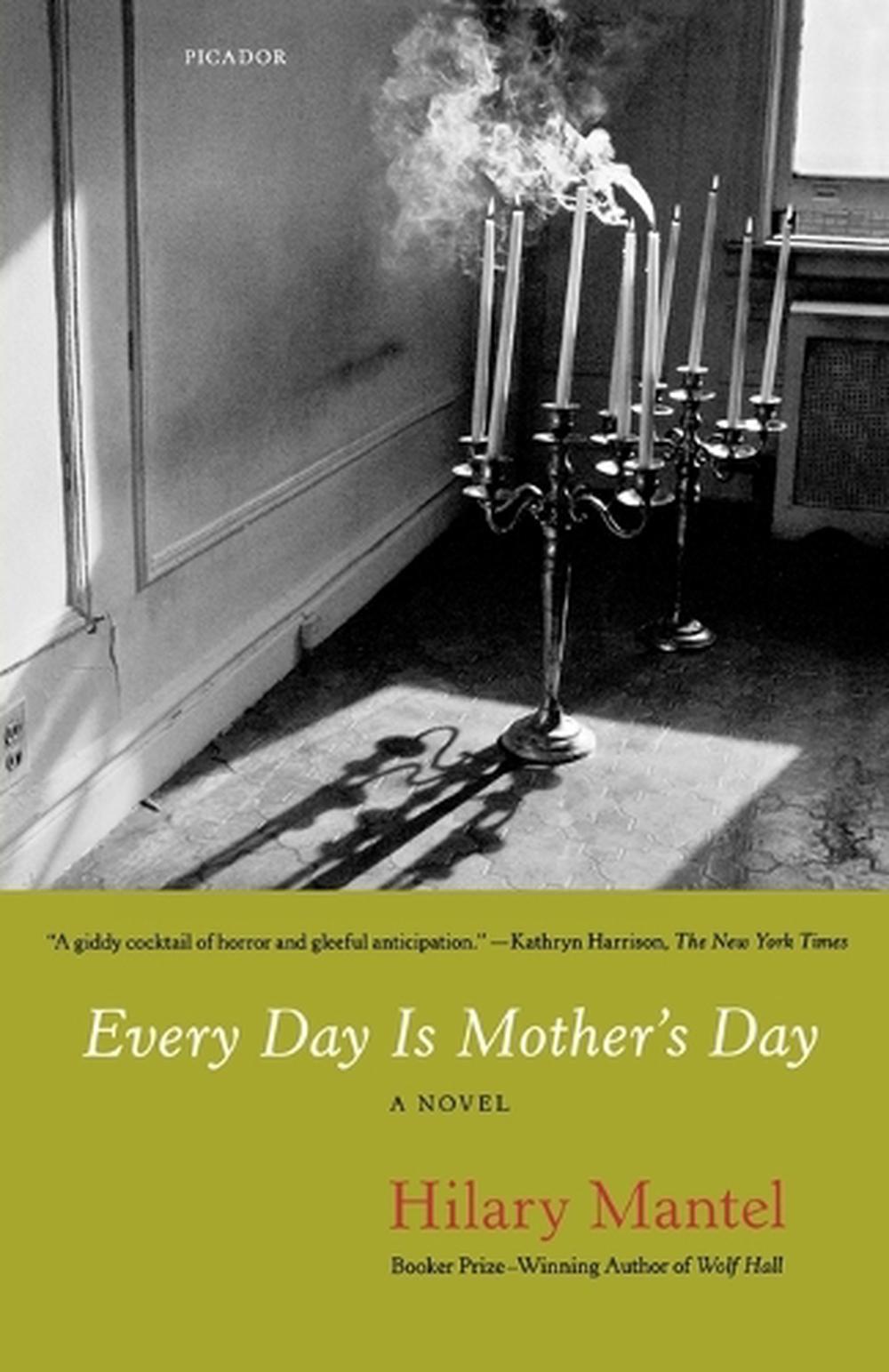

Every Day Is Mother's Day

by Hilary Mantel

By the Booker Prize-Winning Author of WOLF HALL Evelyn Axona is a medium by trade; her daughter, Muriel, is a half-wit by nature. Barricaded in their crumbling house, surrounded by the festering rubbish of years, they defy the curiosity of their neighbors and their social worker.

Paperback

English

Brand New

Publisher Description

By the Booker Prize-Winning Author of WOLF HALL Evelyn Axon is a medium by trade; her daughter, Muriel, is a half-wit by nature. Barricaded in their crumbling house, surrounded by the festering rubbish of years, they defy the curiosity of their neighbors and their social worker, Isabel Field. Isabel is young and inexperienced and has troubles of her own: an elderly father who wanders the streets, and a lover, Colin, who wants her to run away with him. But Colin has three horrible children and a shrill wife who is pregnant again--how is he going to run anywhere? As Isabel wrestles with her own problems, a horrible secret grows in the darkness of the Axon household. When at last it comes to light, the result is by turns hilarious and terrifying.

Author Biography

Hilary Mantel twice won the Booker Prize, for her best-selling novel Wolf Hall and its sequel, Bring Up the Bodies. The final novel of the Wolf Hall trilogy, The Mirror & the Light, debuted at #1 on the New York Times bestseller list and won critical acclaim around the globe. Mantel authored over a dozen books, including A Place of Greater Safety, Beyond Black, and the memoir Giving Up the Ghost

Review

"A giddy cocktail of horror and gleeful anticipation." --Kathryn Harrison, The New York Times "Mantel's writing is so exact and brilliant that, in itself, it seems an act of survival, even redemption. . . . Mantel is unflinching, and I like her that way." --Joan Acocella, The New Yorker "Readers will surely be seduced by her sharp humor, reminiscent of Muriel Spark or Edna O'Brien, and her nail-biting narration. . . .Wrapped in the brisk plotting of a suspense thriller, a la Graham Greene." --Charlotte Innes, Los Angeles Times Book Review "Mantel is without peer in her generation." --Janice Nimura, San Francisco Chronicle "Hysterical, the dialogue is spot-on. . . . Muriel and her ma are cunning creations." --Margaret Foster "Strange . . . rather mad . . . extremely funny . . . reminded me of the early Muriel Spark." --Auberon Waugh

Review Quote

Strange . . . rather mad . . . extremely funny . . . reminded me of the early Muriel Spark.

Excerpt from Book

EVERY DAY IS MOTHER''S DAY When Mrs. Axon found out about her daughter''s condition, she was more surprised than sorry; which did not mean that she was not very sorry indeed. Muriel, for her part, seemed pleased. She sat with her legs splayed and her arms around herself, as if reliving the event. Her face wore an expression of daft beatitude. It was always hard to know what would please Muriel. That winter, when the old man fell on the street and broke his hip, Muriel had personally split her sides. She was in her way a formidable character. It wasn''t often she had a good laugh. Click, click, click, said the mock-crocs. They were Mrs. Sidney''s shoes. She passed without mishap along the Avenue, over that flagstone with its wickedly raised edge where Mr. Tillotson had tripped last winter and sustained his fracture; they had petitioned the council. Mrs. Sidney''s good legs, the legs of a woman of twenty-five, moved like scissors down the street. Her face was white and tired, her scarlet lips spoke of an effort at gaiety. She had carried the colour over the line of her thin lips, into a curvaceous bow; she had once read in a magazine that this could be done. Of what lies between the good legs and the sagging face, better not to speak; Mrs. Sidney never dwelled on her torso, she had given it up. She stopped by the house called "The Laburnums," by the straggling privet hedge spattered white with bird-droppings and ravaged by amateur topiary; and tears misted over her eyes. She wore the black coat with the mink trim. Arthur had been with her when she bought the coat. It was budgeted for; the necessity had been weighed. Arthur had been embarrassed, standing among the garment rails; he had clasped his hands behind his back like Prince Philip, and with his eyes elsewhere he tried to look like a man deep in thought. She had not trailed him around the shops, she knew what she wanted. "A good coat," she said to him, "a good cloth coat is worth every penny you spend on it." She had tried on two, and then the black. The salesgirl was sixteen. She was not interested in her job. She stood with one limp arm draped over the rail, her hip jutting out, watching Mrs. Sidney push the laden hangers to and fro. She did not know anything about the cut of a good cloth coat. Mrs. Sidney removed her gloves, and her fingers stroked the little mink collar appreciatively. She had tried to engage Arthur''s attention, but he was not looking, and for a second she was shot through with resentment. Carelessly she tossed her old camelhair over a rail; until this morning it had been her best coat, but now it seemed shabby and inconsiderable. She unfastened the buttons carefully, slipped her arms into the silky lining. Turning to see the back in the long mirror, she smiled tentatively at the salesgirl. "Do you think the length...'" The girl raised her thin shoulders in a shrug. By now Arthur stood smiling at her indulgently, his hands still clasped behind his back. "I will take it," Mrs. Sidney said. She minced towards Arthur. "Very nice, dear," Arthur said. "Are you sure you''ve got what you wanted?" She nodded, smiling. He would have been willing, she knew, to pay twenty pounds more, once he had agreed on the economy of a good cloth coat. Arthur did not stint. The girl laid it out by the cash register, flapped some tissue between its crossed arms and slid it, folded, into a big bag. Arthur took out a virgin chequebook, and his rolled-gold fountain pen. Precisely, he unscrewed the cap; smoothly, the ink flowed; with care, he replaced the cap and returned the pen to the inside pocket of his lovat sports jacket. Then, with a single neat pull, he removed the cheque and handed it courteously to the girl. Mrs. Sidney was proud of that, proud of the way the transaction had been carried through; how they did not pay in greasy bundles of notes like plumbers and housepainters. The carrier bag was heavy, with the good cloth coat inside it, and Arthur reached out without speaking and took it from her. He asked about a hat, so anxious was he to have everything correct; but she told him that people do not go in so much for hats nowadays. To be truthful, millinery departments intimidated her. The assistants looked at you scornfully, for so few of the people who tried on hats ever made a purchase; they had lost faith in human nature. She was happy. They had a cup of coffee and a cream cake each, and then they went home. That night Arthur had his first stroke. When she got up in the morning, all the right side of his body was paralysed, and his mouth was twisted down at the corner; he couldn''t speak. By eight o''clock he was lying on a high white bed at the General. She was sitting outside the ward, drinking the strong tea a nurse had given her out of a chipped white cup. All she could think was, you can get these cups as seconds on the market. Could that be where they get them? A hospital, could it be? He''s on the free list, the nurse said, you can come at any time. When she went to see him he moved restlessly those parts he could move; he never again knew what day of the week it was, or anything at all about the world in the corridor or the market-place beyond. He suffered his second stroke while she was there, and they put lilac screens around the bed and informed her that he had passed away. She wore the black coat to his funeral. Mrs. Sidney raised one elegant knee a little, to prop her bag on it, fumbled inside and took out a pink tissue. Standing by the stained and formless privet, she dabbed her eyes. She looked for a litterbin, but there were none in the Avenue. She screwed the tissue back into her handbag and scissored along the street. The Axons'' house stood on a corner. There was a little gate let in between the rhododendrons. No weeds pushed up between the stones of the path. And this was odd, because you would not have thought of Evelyn Axon as a keen gardener. There was stained glass in the door of the porch, venous crimson and the storm-dull blue of August skies. Mrs. Sidney stopped a pace from the door. She feared her nerve was going to fail her. Again she fumbled with her bag, patting for her purse to make sure it was still there. She did not know whether Mrs. Axon accepted payment. A small tickle of grief and fear rose up in her throat. She arrived at her decision; Mrs. Axon would already be watching from some window in the house. She placed her finger on the doorbell as if she were buttonholing the secret of the universe. It did not work. But somewhere, in the dark interior of the house, Evelyn moved towards the door. She opened it just as Mrs. Sidney raised her hand to knock. Mrs. Sidney lowered her arm foolishly. Evelyn nodded. "Come in," she said. "I suppose you want to speak to your late husband." It was a nice detached property. As soon as she entered the hall behind Evelyn, Mrs. Sidney''s eyes became viper-sharp. She took in the neglected parquet floor, the umbrella stand, the small table quite bare except for one potplant, withered and brown. "Nothing seems to survive," Evelyn said. Mrs. Sidney took a tighter grip on her bag. "And into the front parlour," Evelyn said. Then she kept her eyes on Evelyn''s fawn cardigan, the bulky shape moving weightily ahead. It was a sunless room, seldom used; at this time Evelyn lived mostly at the back of the house. There were heavy curtains, a round dining-table in some dark wood, eight hard chairs with leather seats; a china cabinet, and two green armchairs placed at either side of the empty fireplace. "You''ll want the fire," Evelyn said; she was nothing if not a good hostess. Mrs. Sidney took one of the armchairs, knees together, her handbag poised on them. Evelyn shuffled out and left her alone. She stared at the china cabinet, which was quite empty. Evelyn returned with a little electric fire, two bars, dusty, the flex fraying. "If you don''t mind," Mrs. Sidney said, "that''s dangerous. Bare wires like that." Evelyn slammed the plug firmly into the socket. As she stood up, she gave Mrs. Sidney what Mrs. Sidney called a straight look, the kind of look that is given to people who speak out of turn. "Make yourself comfortable, Mrs. Sidney," she said. Once again, Mrs. Sidney was struck by the cultured tone of Evelyn''s voice. She was, had been, what old-fashioned people called a lady. She and her husband had lived in this house when these few dank autumnal avenues were the best addresses in town. The Axons had always kept to themselves. For years the neighbours had complained about Evelyn''s ways, about the odd times at which she hung out her washing, about her habit of muttering to herself in the queue at the Post Office. Yet, Mrs. Sidney thought, she was a cut above. In a way she was a very tragic woman; Mrs. Sidney had a nose for tragedy these days, alerted to it by her own. "You''ll have to excuse my not providing tea," Evelyn said. "It''s not convenient. I''m not going into the kitchen today." Mrs. Sidney blinked. For want of reply, her eyes slid back to the empty china cabinet. "Smashed," Evelyn said. "All smashed years ago." Evelyn went over to the sideboard. It was, Mrs. Sidney noted, the most modern piece of furniture in the room. It had one of those compartments for drinks, and a flap that came down to serve them on. Evelyn pulled it down. Mrs. Sidney gaped. She could make out the labels from here; baked beans, salmon, ox-tongue. Evelyn reached into the back and took out a half-full bottle of orange squash. From a cupboard, she took two glasses and poured a careful measure into each. On the table stood a jug of lukewarm water. Evelyn set down one of the glasses by her guest''s side, and took the armchair opposite. "I expect you will want to talk about him a little," she said. She sat

Details