CHICAGO MILWAUKEE & ST. PAUL RAILROAD

MILWAUKEE ROAD

This Vintage piece of Railroad History, made by THE ADAMS AND WESTLAKE COMPANY for the CHICAGO MILWAUKEE & ST PAUL RAILROAD. This beautiful Brass Top, bellbottom lantern is marked C.M.&.St.P.Ry. Patented MAY 28, 1895 last date MAY 5, 1908. The brass burner is marked MADE IN U.S.A, burner and fuel fount are in good working condition. The Corning deep red glass globe is embossed C.M.&St P.Ry Cnx has NO CRACKS some small chips around rims. Please view photos and Email with questions. Thanks for looking!

Milwaukee Road

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2015) |

| |

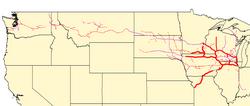

Milwaukee Road system map | |

Twin Cities Hiawatha postcard from 1935 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Chicago, Illinois |

| Reporting mark | MILW |

| Locale | Midwestern and Western United States |

| Dates of operation | 1847–1986 |

| Successor | Soo Line Railroad Most trackage in South Dakota and Montana is now operated by the BNSF Railway Some trackage in Washington is now operated by the Union Pacific Railroad Some trackage in the Midwest is now operated by Canadian Pacific Kansas City, Canadian Pacific Railway and Soo Line Railroad's successor. Some trackage in Wisconsin and Illinois is now operated by the Wisconsin and Southern Railroad |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 81⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 11,248 miles (18,102 km) (1929) 3,023 miles (4,865 km) (1984) |

The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (CMStP&P), better known as the Milwaukee Road (reporting mark MILW), was a Class I railroad that operated in the Midwest and Northwest of the United States from 1847 until 1986.

The company experienced financial difficulty through the 1970s and 1980s, including bankruptcy in 1977 (though it filed for bankruptcy twice in 1925 and 1935, respectively). In 1980, it abandoned its Pacific Extension, which included track in the states of Montana, Idaho, and Washington. The remaining system was merged into the Soo Line Railroad (reporting mark SOO), a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific Railway (reporting mark CP), on January 1, 1986. Much of its historical trackage remains in use by other railroads. The company brand is commemorated by buildings like the historic Milwaukee Road Depot in Minneapolis and preserved locomotives such as Milwaukee Road 261 which operates excursion trains.

History[edit]

Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Minneapolis Railroad[edit]

The railroad that became the Milwaukee Road began as the Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad in Wisconsin, whose goal was to link the developing Lake Michigan port City of Milwaukee with the Mississippi River. The company incorporated in 1847, but changed its name to the Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad in 1850 before construction began. Its first line, 5 miles (8.0 km) long, opened between Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, on November 20, 1850. Extensions followed to Waukesha in February 1851, Madison, and finally the Mississippi River at Prairie du Chien in 1857.[2]

As a result of the financial panic of 1857, the M&M went into receivership in 1859, and was purchased by the Milwaukee and Prairie du Chien Railroad in 1861. In 1867, Alexander Mitchell combined the M&PdC with the Milwaukee and St. Paul (formerly the La Crosse and Milwaukee Railroad Company) under the name Milwaukee and St. Paul.[3] Critical to the development and financing of the railroad was the acquisition of significant land grants. Prominent individual investors in the line included Alexander Mitchell, Russell Sage, Jeremiah Milbank, and William Rockefeller.[4]

In 1874, the name was changed to Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul after constructing an extension to Chicago in 1872. The company absorbed the Chicago and Pacific Railroad Company in 1879, the railroad that built the Bloomingdale Line (now The 606) and what became the Milwaukee District / West Line as part of the 36-mile Elgin Subdivision from Halsted Street in Chicago to the suburb of Elgin, Illinois. In 1890, the company purchased the Milwaukee and Northern Railroad; by now, the railroad had lines running through Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

The corporate headquarters were moved from Milwaukee to the Rand McNally Building in Chicago, America's first all-steel framed skyscraper, in 1889 and 1890, with the car and locomotive shops staying in Milwaukee.[3] The company's general offices were later located in Chicago's Railway Exchange building (built 1904) until 1924, at which time they moved to Chicago Union Station.[5]

Pacific Extension[edit]

In the 1890s, the company's directors felt they had to extend the railroad to the Pacific to remain competitive with other railroads. A survey in 1901 estimated costs to build to the Pacific Northwest as $45 million ($1.27 billion in 2022 dollars). In 1905, the board approved the Pacific Extension, now estimated at $60 million ($1.52 billion in 2022 dollars). The contract for the western part of the route was awarded to Horace Chapin Henry of Seattle. The subsidiary Chicago, Milwaukee and Puget Sound Railway Company was chartered in 1905 to build from the Missouri River to Seattle and Tacoma.[6]

Construction began in 1906 and was completed three years later. The route chosen was 18 miles (29 km) shorter than the next shortest competitor's, as well as better grades than some, but it was an expensive route, since Milwaukee Road received few land grants and had to buy most of the land or acquire smaller railroads.

The two main mountain ranges that had to be crossed, the Rockies and the Cascades, required major civil engineering works and additional locomotive power. The completion of 2,300 miles (3,700 km) of railroad through some of the most varied topography in the nation in only three years was a major feat. Original company maps denote five mountain crossings: Belts, Rockies, Bitterroots, Saddles, and Cascades. These are slight misnomers as the Belt mountains and Bitterroots are part of the Rockies. The route did not cross over the Little Belts or Big Belts, but over the Lenep-Loweth Ridge between the Castle Mountains and the Crazy Mountains.

Some historians question the choice of route, since it bypassed some population centers and passed through areas with limited local traffic potential. Much of the line paralleled the Northern Pacific Railway. Trains magazine called the building of the extension, primarily a long-haul route, "egregious" and a "disaster".[7] George H. Drury listed the Pacific Extension as one of several "wrong decisions" made by the Milwaukee Road's management which contributed to the company's eventual failure.[8]

Beginning in 1909, several smaller railroads were acquired and expanded to form branch lines along the Pacific Extension.[9]: 15

- The Montana Railroad formed the mainline route through Sixteen Mile Canyon as well as the North Montana Line which extended North from Harlowton to Lewistown. This branch led to the settlement of the Judith Basin and, by the 1970s, accounted for 30% of the Milwaukee Road's total traffic.[9]: 75

- The Gallatin Valley Electric Railway, originally built as an interurban line, was extended from Bozeman to the mainline at Three Forks. In 1927, the railroad built the Gallatin Gateway Inn, where passengers traveling to Yellowstone National Park transferred to buses for the remainder of their journey.[9]: 83

- The White Sulphur Springs & Yellowstone Park Railway, originally built by Lew Penwell and John Ringling, primarily carried lumber and agricultural products.[9]: 86

Operating conditions in the mountain regions of the Pacific Extension proved difficult. Winter temperatures of −40 °F (−40 °C) in Montana made it challenging for steam locomotives to generate sufficient steam. The line snaked through mountainous areas, resulting in "long steep grades and sharp curves". Electrification provided an answer, especially with abundant hydroelectric power in the mountains, and a ready source of copper in Anaconda, Montana.[10] Between 1914 and 1916, the Milwaukee Road implemented a 3,000 volt direct current (DC) overhead system between Harlowton, Montana, and Avery, Idaho, a distance of 438 miles (705 km).[11] Pleased with the result, the Milwaukee electrified its route in Washington between Othello and Tacoma, a further 207 miles (333 km), between 1917 and 1920.[12] This section traversed the Cascades through the 21⁄4-mile (3.6 km) Snoqualmie Tunnel, just south of Snoqualmie Pass and over 400 feet (120 m) lower in elevation. The single-track tunnel's east portal at Hyak included an adjacent company-owned ski area (1937−1950).[13][14][15][16]

Together, the 645 miles (1,038 km) of main-line electrification represented the largest such project in the world up to that time, and would not be exceeded in the US until the Pennsylvania Railroad's efforts in the 1930s.[17] The two separate electrified districts were never unified, as the 216-mile (348 km) Idaho Division (Avery to Othello) was comparatively flat down the St. Joe River to St. Maries and through eastern Washington, and posed few challenges for steam operation.[12] Electrification cost $27 million, but resulted in savings of over $1 million per year from improved operational efficiency.[18]

Bankruptcies[edit]

The Chicago, Milwaukee, and Puget Sound Railway was absorbed by the parent company on January 1, 1913.[6] The Pacific Extension, including subsequent electrification, cost the Milwaukee Road $257 million, over four times the original estimate of $60 million. To meet this cost, the Milwaukee Road sold bonds, which began coming due in the 1920s.[19] Traffic never met projections, and by the early 1920s, the Milwaukee Road was in serious financial condition. This state was exacerbated by the railroad's purchase of several heavily indebted railroads in Indiana. The company declared bankruptcy in 1925 and reorganized as the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad in 1928. In 1929, its total mileage stood at 11,248 miles (18,102 km).[20] In 1927, the railroad launched its second edition of the Olympian as a premier luxury limited passenger train and opened its first railroad-owned tourist hotel, the Gallatin Gateway Inn in Montana, southwest of Bozeman, via a spur from Three Forks.

The company scarcely had a chance for success before the Great Depression hit. Despite innovations such as the famous Hiawatha high-speed trains that exceeded 100 mph (160 km/h), the railroad again filed for bankruptcy in 1935. The Milwaukee Road operated under trusteeship until December 1, 1945.

During WWII the CMSt.P&P sponsored one of the Army's MRS units the 757th Railroad Shop Battalion.

Postwar[edit]

The Milwaukee Road enjoyed temporary success after World War II. Out of bankruptcy and with the wartime ban on new passenger service lifted, the company upgraded its trains. The Olympian Hiawatha began running between Chicago and the Puget Sound over the Pacific Extension in 1947,[21] and the Twin Cities Hiawatha received new equipment in 1948.[22] Dieselisation accelerated and was complete by 1957.[23][24] In 1955, the Milwaukee Road took over from the Chicago and North Western's handling of Union Pacific's streamliner trains between Chicago and Omaha.[21]

The whole railroad industry found itself in decline in the late 1950s and the 1960s, but the Milwaukee Road was hit particularly hard. The Midwest was overbuilt with a plethora of competing railroads, while the competition on the transcontinental routes to the Pacific was tough. The premier transcontinental streamliner, the Olympian Hiawatha, despite innovative scenic observation cars, was mothballed in 1961, becoming the first visible casualty. The resignation of President John P. Kiley in 1957 and his replacement with the fairly inexperienced William John Quinn was a pivotal moment. From that point onward, the road's management was fixated on merger with another railroad as the solution to the Milwaukee's problems.

Railroad mergers had to be approved by the Interstate Commerce Commission, and in 1969 the ICC effectively blocked the merger with the Chicago and North Western Railway (C&NW) that the Milwaukee Road had counted on and had been planning for since 1964. The ICC asked for terms that the C&NW was not willing to agree to. The merger of the "Hill Lines" was approved at around the same time, and the merged Burlington Northern came into being.

Early 1970s[edit]

The formation of Burlington Northern in 1970 from the merger of Northern Pacific, Great Northern, Burlington Route, and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway on March 3 created a stronger competitor on most Milwaukee Road routes. To boost competition, the ICC gave the Milwaukee Road the right to connect with new railroads in the West over Burlington Northern tracks. Traffic on its Pacific Extension increased substantially to more than four trains a day each way[25] as it began interchanging cars with Southern Pacific at Portland, Oregon and Canadian railroads at Sumas, Washington.[26] The railroad's foothold on transcontinental traffic leaving the Port of Seattle increased such that the Milwaukee Road held a staggering advantage over BN, carrying nearly 80% of the originating traffic along with 50% of the total container traffic leaving the Puget Sound (prior to severe service declines after roughly 1974).[citation needed]

In 1970, the president of Chicago and North Western offered to sell the railroad to the Milwaukee Road outright. President William John Quinn refused,[27] stating that it now believed only a merger with a larger system, not a slightly smaller one, could save the railroad. Almost immediately, the railroad filed unsuccessfully with the ICC to be included in the Union Pacific merger with the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad.

By the mid-1970s, deferred maintenance on Milwaukee Road's physical plant, which had been increasing throughout the 1960s as it attempted to improve its financial appearance for merger, was beginning to cause problems. The railroad's financial problems were exacerbated by their practice of improving its earnings during that period by selling off its wholly owned cars to financial institutions and leasing them back. The lease charges became greater, and more cars needed to be sold to pay the lease payments. The railroad's fleet of cars was becoming older because more money was being spent on finance payments for the old cars rather than buying new ones. This contributed to car shortages that turned away business.

The Milwaukee Road chose at this time to end its mainline electrification. Its electric locomotive fleet was reaching the end of its service life, and newer diesel locomotives such as the EMD SD40-2 and the GE Universal Series were more than capable of handling the route. The final electric freight arrived at Deer Lodge, Montana on June 15, 1974.[28][29]

In 1976, the Milwaukee Road exercised its right under the Burlington Northern merger to petition for inclusion based on its weak financial condition. The ICC denied it on March 2, 1977.[30][31]