Rare Hand made wooden small statue of a Crusader knight.

Dimensions

15cm height.

6cm wide

The item on the pictures is the one that you will receive.

Look carrefully and judge for your self for the quallity and the grade.

S&h is $24.90 for all the world.

Registered mail.

BID WITH CONFIDENCE.

SELLER WITH 100% POSITIVE FEEDBACK

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity.[1][2]

Knighthood finds origins in the Greek hippeis and hoplite (ἱππεῖς) and Roman eques and centurion of classical antiquity.[3]

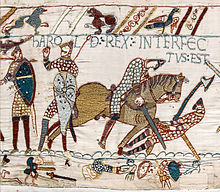

In the Early Middle Ages in Europe, knighthood was conferred upon mounted warriors.[4] During the High Middle Ages, knighthood was considered a class of lower nobility. By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior. Often, a knight was a vassal who served as an elite fighter, a bodyguard or a mercenary for a lord, with payment in the form of land holdings.[5] The lords trusted the knights, who were skilled in battle on horseback. Knighthood in the Middle Ages was closely linked with horsemanship (and especially the joust) from its origins in the 12th century until its final flowering as a fashion among the high nobility in the Duchy of Burgundy in the 15th century. This linkage is reflected in the etymology of chivalry, cavalier and related terms. In that sense, the special prestige accorded to mounted warriors in Christendom finds a parallel in the furusiyya in the Islamic world.

In the Late Middle Ages, new methods of warfare began to render classical knights in armour obsolete, but the titles remained in many countries. Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I is often referred to as the "last knight" in this regard.[6][7] The ideals of chivalry were popularized in medieval literature, particularly the literary cycles known as the Matter of France, relating to the legendary companions of Charlemagne and his men-at-arms, the paladins, and the Matter of Britain, relating to the legend of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table.

Today, a number of orders of knighthood continue to exist in Christian Churches, as well as in several historically Christian countries and their former territories, such as the Roman Catholic Sovereign Military Order of Malta, the Order of the Holy Sepulchre, the Protestant Order of Saint John, as well as the English Order of the Garter, the Swedish Royal Order of the Seraphim, and the Order of St. Olav. There are also dynastic orders like the Order of the Golden Fleece, the Order of the British Empire and the Order of St. George. In modern times these are orders centered around charity and civic service, and are no longer military orders. Each of these orders has its own criteria for eligibility, but knighthood is generally granted by a head of state, monarch, or prelate to selected persons to recognise some meritorious achievement, as in the British honours system, often for service to the Church or country. The modern female equivalent in the English language is Dame.

Etymology

The word knight, from Old English cniht ("boy" or "servant"),[8] is a cognate of the German word Knecht ("servant, bondsman, vassal").[9] This meaning, of unknown origin, is common among West Germanic languages (cf Old Frisian kniucht, Dutch knecht, Danish knægt, Swedish knekt, Norwegian knekt, Middle High German kneht, all meaning "boy, youth, lad").[8] Middle High German had the phrase guoter kneht, which also meant knight; but this meaning was in decline by about 1200.[10]

The meaning of cniht changed over time from its original meaning of "boy" to "household retainer". Ælfric's homily of St. Swithun describes a mounted retainer as a cniht. While cnihtas might have fought alongside their lords, their role as household servants features more prominently in the Anglo-Saxon texts. In several Anglo-Saxon wills cnihtas are left either money or lands. In his will, King Æthelstan leaves his cniht, Aelfmar, eight hides of land.[11]

A rādcniht, "riding-servant", was a servant on horseback.[12]

A narrowing of the generic meaning "servant" to "military follower of a king or other superior" is visible by 1100. The specific military sense of a knight as a mounted warrior in the heavy cavalry emerges only in the Hundred Years' War. The verb "to knight" (to make someone a knight) appears around 1300; and, from the same time, the word "knighthood" shifted from "adolescence" to "rank or dignity of a knight".

An Equestrian (Latin, from eques "horseman", from equus "horse")[13] was a member of the second highest social class in the Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. This class is often translated as "knight"; the medieval knight, however, was called miles in Latin (which in classical Latin meant "soldier", normally infantry).[14][15][16]

In the later Roman Empire, the classical Latin word for horse, equus, was replaced in common parlance by the vulgar Latin caballus, sometimes thought to derive from Gaulish caballos.[17] From caballus arose terms in the various Romance languages cognate with the (French-derived) English cavalier: Italian cavaliere, Spanish caballero, French chevalier (whence chivalry), Portuguese cavaleiro, and Romanian cavaler.[18] The Germanic languages have terms cognate with the English rider: German Ritter, and Dutch and Scandinavian ridder. These words are derived from Germanic rīdan, "to ride", in turn derived from the Proto-Indo-European root reidh-.[19]

Evolution of medieval knighthood

Pre-Carolingian legacies

In ancient Rome there was a knightly class Ordo Equestris (order of mounted nobles). Some portions of the armies of Germanic peoples who occupied Europe from the 3rd century AD onward had been mounted, and some armies, such as those of the Ostrogoths, were mainly cavalry.[20] However, it was the Franks who generally fielded armies composed of large masses of infantry, with an infantry elite, the comitatus, which often rode to battle on horseback rather than marching on foot. When the armies of the Frankish ruler Charles Martel defeated the Umayyad Arab invasion at the Battle of Tours in 732, the Frankish forces were still largely infantry armies, with elites riding to battle but dismounting to fight.

Carolingian age

In the Early Medieval period any well-equipped horseman could be described as a knight, or miles in Latin.[21] The first knights appeared during the reign of Charlemagne in the 8th century.[22][23][24] As the Carolingian Age progressed, the Franks were generally on the attack, and larger numbers of warriors took to their horses to ride with the Emperor in his wide-ranging campaigns of conquest. At about this time the Franks increasingly remained on horseback to fight on the battlefield as true cavalry rather than mounted infantry, with the discovery of the stirrup, and would continue to do so for centuries afterwards.[25] Although in some nations the knight returned to foot combat in the 14th century, the association of the knight with mounted combat with a spear, and later a lance, remained a strong one. The older Carolingian ceremony of presenting a young man with weapons influenced the emergence of knighthood ceremonies, in which a noble would be ritually given weapons and declared to be a knight, usually amid some festivities.[26]

These mobile mounted warriors made Charlemagne's far-flung conquests possible, and to secure their service he rewarded them with grants of land called benefices.[22] These were given to the captains directly by the Emperor to reward their efforts in the conquests, and they in turn were to grant benefices to their warrior contingents, who were a mix of free and unfree men. In the century or so following Charlemagne's death, his newly empowered warrior class grew stronger still, and Charles the Bald declared their fiefs to be hereditary, and also issued the Edict of Pîtres in 864, largely moving away from the infantry-based traditional armies and calling upon all men who could afford it to answer calls to arms on horseback to quickly repel the constant and wide-ranging Viking attacks, which is considered the beginnings of the period of knights that were to become so famous and spread throughout Europe in the following centuries. The period of chaos in the 9th and 10th centuries, between the fall of the Carolingian central authority and the rise of separate Western and Eastern Frankish kingdoms (later to become France and Germany respectively) only entrenched this newly landed warrior class. This was because governing power and defense against Viking, Magyar and Saracen attack became an essentially local affair which revolved around these new hereditary local lords and their demesnes.[23]

Multiple Crusades

Clerics and the Church often opposed the practices of the Knights because of their abuses against women and civilians, and many such as St. Bernard, were convinced that the Knights served the devil and not God and needed reforming.[27] In the course of the 12th century knighthood became a social rank, with a distinction being made between milites gregarii (non-noble cavalrymen) and milites nobiles (true knights).[28] As the term "knight" became increasingly confined to denoting a social rank, the military role of fully armoured cavalryman gained a separate term, "man-at-arms". Although any medieval knight going to war would automatically serve as a man-at-arms, not all men-at-arms were knights. The first military orders of knighthood were the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre and the Knights Hospitaller, both founded shortly after the First Crusade of 1099, followed by the Order of Saint Lazarus (1100), Knights Templars (1118) and the Teutonic Knights (1190). At the time of their foundation, these were intended as monastic orders, whose members would act as simple soldiers protecting pilgrims. It was only over the following century, with the successful conquest of the Holy Land and the rise of the crusader states, that these orders became powerful and prestigious.

The great European legends of warriors such as the paladins, the Matter of France and the Matter of Britain popularized the notion of chivalry among the warrior class.[29][30] The ideal of chivalry as the ethos of the Christian warrior, and the transmutation of the term "knight" from the meaning "servant, soldier", and of chevalier "mounted soldier", to refer to a member of this ideal class, is significantly influenced by the Crusades, on one hand inspired by the military orders of monastic warriors, and on the other hand also cross-influenced by Islamic (Saracen) ideals of furusiyya.[30][31]

Knightly culture in the Middle Ages

Training

The institution of knights was already well-established by the 10th century.[32] While the knight was essentially a title denoting a military office, the term could also be used for positions of higher nobility such as landholders. The higher nobles grant the vassals their portions of land (fiefs) in return for their loyalty, protection, and service. The nobles also provided their knights with necessities, such as lodging, food, armour, weapons, horses, and money.[33] The knight generally held his lands by military tenure which was measured through military service that usually lasted 40 days a year. The military service was the quid pro quo for each knight's fief. Vassals and lords could maintain any number of knights, although knights with more military experience were those most sought after. Thus, all petty nobles intending to become prosperous knights needed a great deal of military experience.[32] A knight fighting under another's banner was called a knight bachelor while a knight fighting under his own banner was a knight banneret.

Page

A knight had to be born of nobility – typically sons of knights or lords.[33] In some cases commoners could also be knighted as a reward for extraordinary military service. Children of the nobility were cared for by noble foster-mothers in castles until they reached age seven.

The seven-year-old boys were given the title of page and turned over to the care of the castle's lords. They were placed on an early training regime of hunting with huntsmen and falconers, and academic studies with priests or chaplains. Pages then become assistants to older knights in battle, carrying and cleaning armour, taking care of the horses, and packing the baggage. They would accompany the knights on expeditions, even into foreign lands. Older pages were instructed by knights in swordsmanship, equestrianism, chivalry, warfare, and combat (but using wooden swords and spears).

Squire

When the boy turned 15, he became a squire. In a religious ceremony, the new squire swore on a sword consecrated by a bishop or priest, and attended to assigned duties in his lord's household. During this time the squires continued training in combat and were allowed to own armour (rather than borrowing it).

Squires were required to master the “seven points of agilities” – riding, swimming and diving, shooting different types of weapons, climbing, participation in tournaments, wrestling, fencing, long jumping, and dancing – the prerequisite skills for knighthood. All of these were even performed while wearing armour.[34]

Upon turning 21, the squire was eligible to be knighted.

Accolade

The accolade or knighting ceremony was usually held during one of the great feasts or holidays, like Christmas or Easter, and sometimes at the wedding of a noble or royal. The knighting ceremony usually involved a ritual bath on the eve of the ceremony and a prayer vigil during the night. On the day of the ceremony, the would-be knight would swear an oath and the master of the ceremony would dub the new knight on the shoulders with a sword.[32][33] Squires, and even soldiers, could also be conferred direct knighthood early if they showed valor and efficiency for their service; such acts may include deploying for an important quest or mission, or protecting a high diplomat or a royal relative in battle.

Chivalric code

Knights were expected, above all, to fight bravely and to display military professionalism and courtesy. When knights were taken as prisoners of war, they were customarily held for ransom in somewhat comfortable surroundings. This same standard of conduct did not apply to non-knights (archers, peasants, foot-soldiers, etc.) who were often slaughtered after capture, and who were viewed during battle as mere impediments to knights' getting to other knights to fight them.[35]

Chivalry developed as an early standard of professional ethics for knights, who were relatively affluent horse owners and were expected to provide military services in exchange for landed property. Early notions of chivalry entailed loyalty to one's liege lord and bravery in battle, similar to the values of the Heroic Age. During the Middle Ages, this grew from simple military professionalism into a social code including the values of gentility, nobility and treating others reasonably.[36] In The Song of Roland (c. 1100), Roland is portrayed as the ideal knight, demonstrating unwavering loyalty, military prowess and social fellowship. In Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival (c. 1205), chivalry had become a blend of religious duties, love and military service. Ramon Llull's Book of the Order of Chivalry (1275) demonstrates that by the end of the 13th century, chivalry entailed a litany of very specific duties, including riding warhorses, jousting, attending tournaments, holding Round Tables and hunting, as well as aspiring to the more æthereal virtues of "faith, hope, charity, justice, strength, moderation and loyalty."[37]

Knights of the late medieval era were expected by society to maintain all these skills and many more, as outlined in Baldassare Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier, though the book's protagonist, Count Ludovico, states the "first and true profession" of the ideal courtier "must be that of arms."[38] Chivalry, derived from the French word chevalier ('cavalier'), simultaneously denoted skilled horsemanship and military service, and these remained the primary occupations of knighthood throughout the Middle Ages.

Chivalry and religion were mutually influenced during the period of the Crusades. The early Crusades helped to clarify the moral code of chivalry as it related to religion. As a result, Christian armies began to devote their efforts to sacred purposes. As time passed, clergy instituted religious vows which required knights to use their weapons chiefly for the protection of the weak and defenseless, especially women and orphans, and of churches.[39]

Tournaments

In peacetime, knights often demonstrated their martial skills in tournaments, which usually took place on the grounds of a castle.[40][41] Knights can parade their armour and banner to the whole court as the tournament commenced. Medieval tournaments were made up of martial sports called hastiludes, and were not only a major spectator sport but also played as a real combat simulation. It usually ended with many knights either injured or even killed. One contest was a free-for-all battle called a melee, where large groups of knights numbering hundreds assembled and fought one another, and the last knight standing was the winner. The most popular and romanticized contest for knights was the joust. In this competition, two knights charge each other with blunt wooden lances in an effort to break their lance on the opponent's head or body or unhorse them completely. The loser in these tournaments had to turn his armour and horse over to the victor. The last day was filled with feasting, dancing and minstrel singing.

Besides formal tournaments, they were also unformalized judicial duels done by knights and squires to end various disputes.[42][43] Countries like Germany, Britain and Ireland practiced this tradition. Judicial combat was of two forms in medieval society, the feat of arms and chivalric combat.[42] The feat of arms were done to settle hostilities between two large parties and supervised by a judge. The chivalric combat was fought when one party's honor was disrespected or challenged and the conflict could not be resolved in court. Weapons were standardized and must be of the same caliber. The duel lasted until the other party was too weak to fight back and in early cases, the defeated party were then subsequently executed. Examples of these brutal duels were the judicial combat known as the Combat of the Thirty in 1351, and the trial by combat fought by Jean de Carrouges in 1386. A far more chivalric duel which became popular in the Late Middle Ages was the pas d'armes or "passage of arms". In this hastilude, a knight or a group of knights would claim a bridge, lane or city gate, and challenge other passing knights to fight or be disgraced.[44] If a lady passed unescorted, she would leave behind a glove or scarf, to be rescued and returned to her by a future knight who passed that way.

Heraldry

One of the greatest distinguishing marks of the knightly class was the flying of coloured banners, to display power and to distinguish knights in battle and in tournaments.[45] Knights are generally armigerous (bearing a coat of arms), and indeed they played an essential role in the development of heraldry.[46][47] As heavier armour, including enlarged shields and enclosed helmets, developed in the Middle Ages, the need for marks of identification arose, and with coloured shields and surcoats, coat armoury was born. Armorial rolls were created to record the knights of various regions or those who participated in various tournaments.

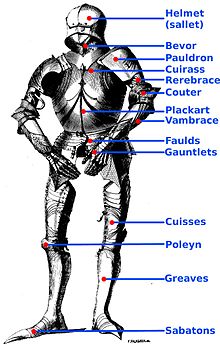

Equipments

Knights used a variety of weapons, including maces, axes and swords. Elements of the knightly armour included helmet, cuirass, gauntlet and shield.

The sword was a weapon designed to be used solely in combat and was useless in hunting and impractical as a tool. Therefore, a sword was a status symbol among the knightly class. Swords were effective against lightly armoured enemies meanwhile maces and warhammers were more effective against heavily armoured ones.[48]:85–86

One of the primary elements of the armour of a knight was a shield. They used shields to block strikes and stop the missile attacks. Oval shields were used during the Dark Ages which were made of wooden boards and they were roughly half an inch thick. Quite short before the 11th century, oval shield was lengthened to cover the left knee of the mounted warrior called the Kite shield. They used shields called the Heater shield during the 13th and the first half of the 14th century. Around 1350, square like shields called bouched shields appeared which had a notch to place the couched lance.[48]:15

Early knights wore mail armor up until the mid-14th Century as their main form of defence. Mail was extremely flexible and provided good protection against sword cuts, but weak against blunt weapons such as the mace and piercing weapons such as the lance. Padded undergarment known as aketon was worn to absorb shock damage and prevent chafing caused by mail. In hotter climates metal rings became too hot, so sleeveless surcoats were worn as a protection against the sun, and also to show their heraldic arms. This sort of coat also evolved to be tabards, waffenrocks and other garments with the arms of the wearer sewn into it.

Helmets of the knight of the early periods usually were more open helms such as the Nasal helmet, and later forms of the Spangenhelm. The lack of more facial protection lead to the evolution of more enclosing helmets to be made in the late 12th to early 13th centuries, this eventually would evolve to make the Great helm. Later forms of the bascinet, which was originally a small helm worn over the larger great helm, evolved to have pivoted or hinged visors, the most popular of which was the hounskull also known as the pig-face visor.

Plate armor first appeared in the Medieval Ages in the 13th Century, plates were added onto the torso and mounted to a base of leather, this form of armor is known as a coat of plates. The torso wasn't the only part of the knight to receive this plate protection evolution, as the elbows and shoulders were covered with circular pieces of metal, commonly referred to as rondels, eventually evolving into the plate arm harness consisting of the Rerebrace, Vambrace, and Spaulder/Pauldron. The legs too were covered in plates, mainly on the shin, called Schynbalds which later evolved to fully enclose the leg in the form of enclosed greaves. As for the upper legs, Cuisses came about in the mid 14th century. Overall, plate armour offered better protection against piercing weapons such as arrows and especially bolts than mail armour did.[48]:15–17

Knights horses were also armored in later periods, Caparisons were the first form of medieval horse coverage and was used much like the surcoat. Other armors such as the facial armoring chanfron, were made for horses.

Medieval and Renaissance chivalric literature

Knights and the ideals of knighthood featured largely in medieval and Renaissance literature, and have secured a permanent place in literary romance.[49] While chivalric romances abound, particularly notable literary portrayals of knighthood include The Song of Roland, Cantar de Mio Cid, The Twelve of England, Geoffrey Chaucer's The Knight's Tale, Baldassare Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier, and Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote, as well as Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur and other Arthurian tales (Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, the Pearl Poet's Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, etc.).

Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), written in the 1130s, introduced the legend of King Arthur, which was to be important to the development of chivalric ideals in literature. Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (The Death of Arthur), written in 1469, was important in defining the ideal of chivalry, which is essential to the modern concept of the knight, as an elite warrior sworn to uphold the values of faith, loyalty, courage, and honour.

Instructional literature was also created. Geoffroi de Charny's "Book of Chivalry" expounded upon the importance of Christian faith in every area of a knight's life, though still laying stress on the primarily military focus of knighthood.

In the early Renaissance greater emphasis was laid upon courtliness. The ideal courtier—the chivalrous knight—of Baldassarre Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier became a model of the ideal virtues of nobility.[50] Castiglione's tale took the form of a discussion among the nobility of the court of the Duke of Urbino, in which the characters determine that the ideal knight should be renowned not only for his bravery and prowess in battle, but also as a skilled dancer, athlete, singer and orator, and he should also be well-read in the humanities and classical Greek and Latin literature.[51]

Later Renaissance literature, such as Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote, rejected the code of chivalry as unrealistic idealism.[52] The rise of Christian humanism in Renaissance literature demonstrated a marked departure from the chivalric romance of late medieval literature, and the chivalric ideal ceased to influence literature over successive centuries until it saw some pockets of revival in post-Victorian literature.

Decline

By the end of the 16th century, knights were becoming obsolete as countries started creating their own professional armies that were quicker to train, cheaper, and easier to mobilize.[53][54] The advancement of high-powered firearms contributed greatly to the decline in use of plate armour, as the time it took to train soldiers with guns was much less compared to that of the knight. The cost of equipment was also significantly lower, and guns had a reasonable chance to easily penetrate a knight's armour. In the 14th century the use of infantrymen armed with pikes and fighting in close formation also proved effective against heavy cavalry, such as during the Battle of Nancy, when Charles the Bold and his armoured cavalry were decimated by Swiss pikemen.[55] As the feudal system came to an end, lords saw no further use of knights. Many landowners found the duties of knighthood too expensive and so contented themselves with the use of squires. Mercenaries also became an economic alternative to knights when conflicts arose.

Armies of the time started adopting a more realistic approach to warfare than the honor-bound code of chivalry. Soon, the remaining knights were absorbed into professional armies. Although they had a higher rank than most soldiers because of their valuable lineage, they lost their distinctive identity that previously set them apart from common soldiers.[53] Some knightly orders survived into modern times. They adopted newer technology while still retaining their age-old chivalric traditions. Examples include the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, Knights Hospitaller and Teutonic Knights.[56]

Radiance of knighthood into the 21st century

When chivalry had long since declined, the cavalry of the early modern era clung to the old ideals. Even the first fighter pilots of the First World War, even in the 20th century, still resorted to knightly ideas in their duels in the sky, aimed at fairness and honesty. At least; such chivalry was spread in the media. This idea was then completely lost in later wars or was perverted by Nazi Germany, which awarded a "Knight's Cross" as an award.[57][58] Conversely, the Austrian priest and resistance fighter Heinrich Maier is referred to as Miles Christi, a Christian knight against Nazi Germany.[59]

While on the one hand attempts are made again and again to revive or restore old knightly orders in order to gain prestige, awards and financial advantages, on the other hand old orders continue to exist or are activated. This especially in the environment of ruling or formerly ruling noble houses. For example, the British Queen Elizabeth II regularly appoints new members to the Order of the British Empire, which also includes members such as Steven Spielberg, Nelson Mandela and Bill Gates, in the 21st century.[60][61][62] In Central Europe, for example, the Order of St. George, whose roots go back to the so-called "last knight" Emperor Maximilian I, was reactivated by the House of Habsburg after its dissolution by Nazi Germany and the fall of the Iron Curtain.[63][64] And in republican France, deserved personalities are highlighted to this day by the award of the Knight of Honor (Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur - Legion of Honour).[65][66][67] In contrast, the knights of the ecclesiastical knightly orders like the Sovereign Military Order of Malta and the Order of Saint John mainly devote themselves to social tasks and care.[68]

The journalist Alexander von Schönburg dealt with nature and the possible necessity of chivalry. In view of the complete social disorientation of the people he diagnosed, he calls for a return to virtues such as modesty, wisdom and, above all, loyalty. For, according to him, the common creed today is roughness, ignorance and egocentrism.[69] Vinzenz Stimpfl-Abele, Procurator of the Habsburg Order of St. George, goes back to Bernhard von Clairvaux to consider the importance of knights in the 21st century. Accordingly, knights must take an active part in the fight against misery in society, especially today.[70] The current activities of the Knights of the Order of Malta and the Order of St. John, who since the beginning of the 20th century have increasingly provided extensive medical and charitable services during wars and peacetime, have also developed in this direction.[68]

Types of knighthood

Hereditary knighthoods

Continental Europe

In continental Europe different systems of hereditary knighthood have existed or do exist. Ridder, Dutch for "knight", is a hereditary noble title in the Netherlands. It is the lowest title within the nobility system and ranks below that of "Baron" but above "Jonkheer" (the latter is not a title, but a Dutch honorific to show that someone belongs to the untitled nobility). The collective term for its holders in a certain locality is the Ridderschap (e.g. Ridderschap van Holland, Ridderschap van Friesland, etc.). In the Netherlands no female equivalent exists. Before 1814, the history of nobility is separate for each of the eleven provinces that make up the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In each of these, there were in the early Middle Ages a number of feudal lords who often were just as powerful, and sometimes more so than the rulers themselves. In old times, no other title existed but that of knight. In the Netherlands only 10 knightly families are still extant, a number which steadily decreases because in that country ennoblement or incorporation into the nobility is not possible anymore.

Likewise Ridder, Dutch for "knight", or the equivalent French Chevalier is a hereditary noble title in Belgium. It is the second lowest title within the nobility system above Écuyer or Jonkheer/Jonkvrouw and below Baron. Like in the Netherlands, no female equivalent to the title exists. Belgium still does have about 232 registered knightly families.

The German and Austrian equivalent of an hereditary knight is a Ritter. This designation is used as a title of nobility in all German-speaking areas. Traditionally it denotes the second lowest rank within the nobility, standing above "Edler" (noble) and below "Freiherr" (baron). For its historical association with warfare and the landed gentry in the Middle Ages, it can be considered roughly equal to the titles of "Knight" or "Baronet".

In the Kingdom of Spain, the Royal House of Spain grants titles of knighthood to the successor of the throne. This knighthood title known as Order of the Golden Fleece is among the most prestigious and exclusive Chivalric Orders. This Order can also be granted to persons not belonging to the Spanish Crown, as the former Emperor of Japan Akihito, the current Queen of United Kingdom Elizabeth II or the important Spanish politician of the Spanish democratic transition Adolfo Suárez, among others.

The Royal House of Portugal historically bestowed hereditary knighthoods to holders of the highest ranks in the Royal Orders. Today, the head of the Royal House of Portugal Duarte Pio, Duke of Braganza, bestows hereditary knighthoods for extraordinary acts of sacrifice and service to the Royal House. There are very few hereditary knights and they are entitled to wear a breast star with the crest of the House of Braganza.

In France, the hereditary knighthood existed similarly throughout as a title of nobility, as well as in regions formerly under Holy Roman Empire control. One family ennobled with a title in such a manner is the house of Hauteclocque (by letters patents of 1752), even if its most recent members used a pontifical title of count. In some other regions such as Normandy, a specific type of fief was granted to the lower ranked knights (fr: chevaliers) called the fief de haubert, referring to the hauberk, or chain mail shirt worn almost daily by knights, as they would not only fight for their liege lords, but enforce and carry out their orders on a routine basis as well.[71] Later the term came to officially designate the higher rank of the nobility in the Ancien Régime (the lower rank being Squire), as the romanticism and prestige associated with the term grew in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Italy and Poland also had the hereditary knighthood that existed within their respective systems of nobility.

Ireland

There are traces of the Continental system of hereditary knighthood in Ireland. Notably all three of the following belong to the Hiberno-Norman FitzGerald dynasty, created by the Earls of Desmond, acting as Earls Palatine, for their kinsmen.

- Knight of Kerry or Green Knight (FitzGerald of Kerry) — the current holder is Sir Adrian FitzGerald, 6th Baronet of Valencia, 24th Knight of Kerry. He is also a Knight of Malta, and has served as President of the Irish Association of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.

- Knight of Glin or Black Knight (FitzGerald of Limerick) — now dormant.

- White Knight (see Edmund Fitzgibbon) — now dormant.

Another Irish family were the O'Shaughnessys, who were created knights in 1553 under the policy of surrender and regrant[72] (first established by Henry VIII of England). They were attainted in 1697 for participation on the Jacobite side in the Williamite wars.[73]

British baronetcies

Since 1611, the British Crown has awarded a hereditary title in the form of the baronetcy.[74] Like knights, baronets are accorded the title Sir. Baronets are not peers of the Realm, and have never been entitled to sit in the House of Lords, therefore like knights they remain commoners in the view of the British legal system. However, unlike knights, the title is hereditary and the recipient does not receive an accolade. The position is therefore more comparable with hereditary knighthoods in continental European orders of nobility, such as Ritter, than with knighthoods under the British orders of chivalry. However, unlike the continental orders, the British baronetcy system was a modern invention, designed specifically to raise money for the Crown with the purchase of the title.

Chivalric orders

Military orders

- Order of the Holy Sepulchre, founded very shortly after the First Crusade in 1099

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta, also founded after the First Crusade in 1099

- Order of Saint Lazarus established about 1100

- Knights Templar, founded 1118, disbanded 1307

- Teutonic Knights, established about 1190, and ruled the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia until 1525

Other orders were established in the Iberian peninsula, under the influence of the orders in the Holy Land and the Crusader movement of the Reconquista:

- Order of Aviz, established in Avis in 1143

- Order of Alcántara, established in Alcántara in 1156

- Order of Calatrava, established in Calatrava in 1158

- Order of Santiago, established in Santiago in 1164.

Honorific orders of knighthood

After the Crusades, the military orders became idealized and romanticized, resulting in the late medieval notion of chivalry, as reflected in the Arthurian romances of the time. The creation of chivalric orders was fashionable among the nobility in the 14th and 15th centuries, and this is still reflected in contemporary honours systems, including the term order itself. Examples of notable orders of chivalry are:

- the Order of Saint George, founded by Charles I of Hungary in 1325/6

- the Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, founded by Count Amadeus VI in 1346

- the Order of the Garter, founded by Edward III of England around 1348

- the Order of the Dragon, founded by King Sigismund of Luxemburg in 1408

- the Order of the Golden Fleece, founded by Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1430

- the Order of Saint Michael, founded by Louis XI of France in 1469

- the Order of the Thistle, founded by King James VII of Scotland (also known as James II of England) in 1687

- the Order of the Elephant, which may have been first founded by Christian I of Denmark, but was founded in its current form by King Christian V in 1693

- the Order of the Bath, founded by George I in 1725

From roughly 1560, purely honorific orders were established, as a way to confer prestige and distinction, unrelated to military service and chivalry in the more narrow sense. Such orders were particularly popular in the 17th and 18th centuries, and knighthood continues to be conferred in various countries:

- The United Kingdom (see British honours system) and some Commonwealth of Nations countries such as New Zealand;

- Some European countries, such as The Netherlands, Belgium and Spain among others (see below).

- The Holy See — see Papal Orders of Chivalry.

There are other monarchies and also republics that also follow this practice. Modern knighthoods are typically conferred in recognition for services rendered to society, which are not necessarily martial in nature. The British musician Elton John, for example, is a Knight Bachelor, thus entitled to be called Sir Elton. The female equivalent is a Dame, for example Dame Julie Andrews.

In the United Kingdom, honorific knighthood may be conferred in two different ways:

- The first is by membership of one of the pure Orders of Chivalry such as the Order of the Garter, the Order of the Thistle and the dormant Order of Saint Patrick, of which all members are knighted. In addition, many British Orders of Merit, namely the Order of the Bath, the Order of St Michael and St George, the Royal Victorian Order and the Order of the British Empire are part of the British honours system, and the award of their highest ranks (Knight/Dame Commander and Knight/Dame Grand Cross), comes together with an honorific knighthood, making them a cross between orders of chivalry and orders of merit. By contrast, membership of other British Orders of Merit, such as the Distinguished Service Order, the Order of Merit and the Order of the Companions of Honour does not confer a knighthood.

- The second is being granted honorific knighthood by the British sovereign without membership of an order, the recipient being called Knight Bachelor.

In the British honours system the knightly style of Sir and its female equivalent Dame are followed by the given name only when addressing the holder. Thus, Sir Elton John should be addressed as Sir Elton, not Sir John or Mr John. Similarly, actress Dame Judi Dench should be addressed as Dame Judi, not Dame Dench or Ms Dench.

Wives of knights, however, are entitled to the honorific pre-nominal "Lady" before their husband's surname. Thus Sir Paul McCartney's ex-wife was formally styled Lady McCartney (rather than Lady Paul McCartney or Lady Heather McCartney). The style Dame Heather McCartney could be used for the wife of a knight; however, this style is largely archaic and is only used in the most formal of documents, or where the wife is a Dame in her own right (such as Dame Norma Major, who gained her title six years before her husband Sir John Major was knighted). The husbands of Dames have no honorific pre-nominal, so Dame Norma's husband remained John Major until he received his own knighthood.

Since the reign of Edward VII a clerk in holy orders in the Church of England has not normally received the accolade on being appointed to a degree of knighthood. He receives the insignia of his honour and may place the appropriate letters after his name or title but he may not be called Sir and his wife may not be called Lady. This custom is not observed in Australia and New Zealand, where knighted Anglican clergymen routinely use the title "Sir". Ministers of other Christian Churches are entitled to receive the accolade. For example, Sir Norman Cardinal Gilroy did receive the accolade on his appointment as Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 1969. A knight who is subsequently ordained does not lose his title. A famous example of this situation was The Revd Sir Derek Pattinson, who was ordained just a year after he was appointed Knight Bachelor, apparently somewhat to the consternation of officials at Buckingham Palace.[75] A woman clerk in holy orders may be made a Dame in exactly the same way as any other woman since there are no military connotations attached to the honour. A clerk in holy orders who is a baronet is entitled to use the title Sir.

Outside the British honours system it is usually considered improper to address a knighted person as 'Sir' or 'Dame'. Some countries, however, historically did have equivalent honorifics for knights, such as Cavaliere in Italy (e.g. Cavaliere Benito Mussolini), and Ritter in Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire (e.g. Georg Ritter von Trapp).

State Knighthoods in the Netherlands are issued in three orders: the Order of William, the Order of the Netherlands Lion, and the Order of Orange Nassau. Additionally there remain a few hereditary knights in the Netherlands.

In Belgium, honorific knighthood (not hereditary) can be conferred by the King on particularly meritorious individuals such as scientists or eminent businessmen, or for instance to astronaut Frank De Winne, the second Belgian in space. This practice is similar to the conferral of the dignity of Knight Bachelor in the United Kingdom. In addition, there still are a number of hereditary knights in Belgium (see below).

In France and Belgium, one of the ranks conferred in some Orders of Merit, such as the Légion d'Honneur, the Ordre National du Mérite, the Ordre des Palmes académiques and the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France, and the Order of Leopold, Order of the Crown and Order of Leopold II in Belgium, is that of Chevalier (in French) or Ridder (in Dutch), meaning Knight.

In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth the monarchs tried to establish chivalric orders, but the hereditary lords who controlled the Union did not agree and managed to ban such assemblies. They feared the king would use Orders to gain support for absolutist goals and to make formal distinctions among the peerage, which could lead to its legal breakup into two separate classes, and that the king would later play one against the other and eventually limit the legal privileges of hereditary nobility. But finally in 1705 King August II managed to establish the Order of the White Eagle which remains Poland's most prestigious order of that kind. The head of state (now the President as the acting Grand Master) confers knighthoods of the Order to distinguished citizens, foreign monarchs and other heads of state. The Order has its Chapter. There were no particular honorifics that would accompany a knight's name, as historically all (or at least by far most) of its members would be royals or hereditary lords anyway. So today, a knight is simply referred to as "Name Surname, knight of the White Eagle (Order)".

Women

England and the United Kingdom

Women were appointed to the Order of the Garter almost from the start. In all, 68 women were appointed between 1358 and 1488, including all consorts. Though many were women of royal blood, or wives of knights of the Garter, some women were neither. They wore the garter on the left arm, and some are shown on their tombstones with this arrangement. After 1488, no other appointments of women are known, although it is said that the Garter was conferred upon Neapolitan poet Laura Bacio Terricina, by King Edward VI. In 1638, a proposal was made to revive the use of robes for the wives of knights in ceremonies, but this did not occur. Queens consort have been made Ladies of the Garter since 1901 (Queens Alexandra in 1901,[76] Mary in 1910 and Elizabeth in 1937). The first non-royal woman to be made Lady Companion of the Garter was The Duchess of Norfolk in 1990,[77] the second was The Baroness Thatcher in 1995[78] (post-nominal: LG). On 30 November 1996, Lady Fraser was made Lady of the Thistle,[79] the first non-royal woman (post-nominal: LT). (See Edmund Fellowes, Knights of the Garter, 1939; and Beltz: Memorials of the Order of the Garter). The first woman to be granted a knighthood in modern Britain seems to have been H.H. Nawab Sikandar Begum Sahiba, Nawab Begum of Bhopal, who became a Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India (GCSI) in 1861, at the foundation of the order. Her daughter received the same honor in 1872, as well as her granddaughter in 1910. The order was open to "princes and chiefs" without distinction of gender. The first European woman to have been granted an order of knighthood was Queen Mary, when she was made a Knight Grand Commander of the same order, by special statute, in celebration of the Delhi Durbar of 1911.[80] She was also granted a damehood in 1917 as a Dame Grand Cross, when the Order of the British Empire was created[81] (it was the first order explicitly open to women). The Royal Victorian Order was opened to women in 1936, and the Orders of the Bath and Saint Michael and Saint George in 1965 and 1971 respectively.[82]

France

Medieval French had two words, chevaleresse and chevalière, which were used in two ways: one was for the wife of a knight, and this usage goes back to the 14th century. The other was possibly for a female knight. Here is a quote from Menestrier, a 17th-century writer on chivalry: "It was not always necessary to be the wife of a knight in order to take this title. Sometimes, when some male fiefs were conceded by special privilege to women, they took the rank of chevaleresse, as one sees plainly in Hemricourt where women who were not wives of knights are called chevaleresses." Modern French orders of knighthood include women, for example the Légion d'Honneur (Legion of Honor) since the mid-19th century, but they are usually called chevaliers. The first documented case is that of Angélique Brûlon (1772–1859), who fought in the Revolutionary Wars, received a military disability pension in 1798, the rank of 2nd lieutenant in 1822, and the Legion of Honor in 1852. A recipient of the Ordre National du Mérite recently requested from the order's Chancery the permission to call herself "chevalière," and the request was granted (AFP dispatch, Jan 28, 2000).[82]

Italy

As related in Orders of Knighthood, Awards and the Holy See by H. E. Cardinale (1983), the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary was founded by two Bolognese nobles Loderingo degli Andalò and Catalano di Guido in 1233, and approved by Pope Alexander IV in 1261. It was the first religious order of knighthood to grant the rank of militissa to women. However, this order was suppressed by Pope Sixtus V in 1558.[82]

The Low Countries

At the initiative of Catherine Baw in 1441, and 10 years later of Elizabeth, Mary, and Isabella of the house of Hornes, orders were founded which were open exclusively to women of noble birth, who received the French title of chevalière or the Latin title of equitissa. In his Glossarium (s.v. militissa), Du Cange notes that still in his day (17th century), the female canons of the canonical monastery of St. Gertrude in Nivelles (Brabant), after a probation of 3 years, are made knights (militissae) at the altar, by a (male) knight called in for that purpose, who gives them the accolade with a sword and pronounces the usual words.[82]

Spain

To honour those women who defended Tortosa against an attack by the Moors, Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona, created the Order of the Hatchet (Orden de la Hacha) in 1149.[82]

The inhabitants [of Tortosa] being at length reduced to great streights, desired relief of the Earl, but he, being not in a condition to give them any, they entertained some thoughts of making a surrender. Which the Women hearing of, to prevent the disaster threatening their City, themselves, and Children, put on men's Clothes, and by a resolute sally, forced the Moors to raise the Siege. The Earl, finding himself obliged, by the gallentry of the action, thought fit to make his acknowlegements thereof, by granting them several Privileges and Immunities, and to perpetuate the memory of so signal an attempt, instituted an Order, somewhat like a Military Order, into which were admitted only those Brave Women, deriving the honour to their Descendants, and assigned them for a Badge, a thing like a Fryars Capouche, sharp at the top, after the form of a Torch, and of a crimson colour, to be worn upon their Head-clothes. He also ordained, that at all publick meetings, the women should have precedence of the Men. That they should be exempted from all Taxes, and that all the Apparel and Jewels, though of never so great value, left by their dead Husbands, should be their own. These Women having thus acquired this Honour by their personal Valour, carried themselves after the Military Knights of those days.

Rare Hand made wooden small statue of a Knight.

Dimensions

15cm height.

6cm wide

The item on the pictures is the one that you will receive.

Look carrefully and judge for your self for the quallity and the grade.

S&h is $24.90 for all the world.

Registered mail.

BID WITH CONFIDENCE.

SELLER WITH 100% POSITIVE FEEDBACK

Socrates (/ˈsɒkrətiːz/;[1] Ancient Greek: Σωκράτης Sōkrátēs [sɔːkrátɛːs]; c. 470 – 399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, and as being the first moral philosopher of the Western ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, he authored no texts, and is known chiefly through the accounts of classical writers composing after his lifetime, particularly his students Plato and Xenophon. Plato, Xenophon and other authors wrote in form of dialogues, Socrates and his interlocutors examining a subject—this gave rise to literature genre that was later named as Logoi Socraticoi (Socratic dialogues). Since the account of Plato and Xenophon are often contradictory, reconstruction of historical Socrates is nearly impossible, this is named as the Socratic problem. Socrates was a polarizing figure in Athenian society. In 399 BC, he was accused of corrupting the youth and not believing State Gods and after a trial that lasted a day, he was sentenced to death. He spent his last day in prison, refusing to escape as his followers were urging him.

Plato's dialogues are among the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from antiquity, from which Socrates has become renowned for his contributions to the fields of rationalism, ethics and epistemology. It is this Platonic Socrates who lends his name to the concepts of Socratic irony and the Socratic method. However, questions remain regarding the distinction between the real-life Socrates and Plato's portrayal of Socrates in his dialogues. Socrates exerted a strong influence on philosophers in later antiquity and in the modern era. Depictions of Socrates in art, literature and popular culture have made him one of the most widely known figures in the Western philosophical tradition.

Sources and the Socratic problem

Socrates didn't write down any of his teachings and what we know of him comes from the accounts of others; mainly his pupils, the philosopher Plato and the historian Xenophon, the comedian Aristophanes (Socrates's contemporary), and lastly Aristotle, who was born after Socrates's death. The often contradictory stories of the ancient sources make it incredibly difficult to reliably reconstruct Socrates's thoughts in the proper context; this dilemma is called the Socratic problem.[2] The works of Plato, Xenophon and other authors on Socrates were in the form of dialogue between Socrates and his interlocutors and provide the main source of information on Socrates's life and thought and compose the major part of Logoi Socraticoi, a term coined by Aristotle to describe its contemporary newly formed literature genre on Socrates.[3] As Aristotle first noted, authors imitate Socrates, but the extent to which they represent the real Socrates or are works of fiction is a matter of debate.[4] Only Plato's and Xenophon's dialogues survive to current era. The exact date of authoring each dialogue is unknown, but it is believed that most were written after Socrates death.[5]

Plato and Xenophon

Xenophon was a well educated, honest man but he lacked the intelligence of a trained philosopher and couldn't conceptualize or articulate Socrates's arguments.[6] Xenophon admired Socrates for his intelligence, patriotic stance during wartimes, and courage.[7] Xenophon discusses Socrates in four of his works: the Memorabilia, the Oeconomicus, the Symposium, and the Apology of Socrates—he also mentions a story with Socrates in his Anabasis.[8] Oeconomicus hosts a discussion on practical agricultural issues.[9] Apologia offers the speeches of Socrates during his trial but is unsophisticated compared to Plato's work of the same title.[10] Symposium is a dialogue of Socrates with other prominent Athenieans after dinner—quite different from Plato's Symposium—differing even in the names of those attending, let alone Socrates's presented ideas.[11] In Memorabilia, he defends, as he proclaimed, Socrates from the accusations against him of corrupting the youth and being against State religion. Essentially, it is a collection of various stories and constituted an apology of Socrates.[12]

Plato's representation of Socrates is not straightforward.[13] Plato was a pupil of Socrates and outlived him by five decades.[14] How trustworthy Plato is on representing Socrates is a matter of debate; the view that he wouldn't alter Socratic thought (known as Tailor-Burket thesis) isn't shared by many contemporary scholars.[15] A driver of this doubt is the inconsistency of the character of Socrates he presents.[16] One common explanation of the inconsistency is that Plato initially tried to accurately represent the historical Socrates, but later inserted his views on Socrates's sayings—under this understanding, there is a distinction among the early writing of Plato as Socratic Socrates, whereas late writing represent Platonic Socrates—a definitive line between the two being blurred.[17]

Xenophon's and Plato's accounts differ in their presentations of Socrates as a person—in Xenophon's portrait, he is more dull, and less humorous and ironic.[7] Plato's Socrates is far from conservative Xenophon's Socrates.[18] Socrates at Xenophon lacks the philosophical features of Plato's Socrates- ignorance, elenchus- or thinks enkrateia is of pivotal importance which is not the case at Plato's Socrates.[19] Generally, Logoi Socraticoi can not help us reconstruct historical Socrates even in cases where their narratives overlap due to possible intertextuality.[20]

Aristophanes and other sources

Athenian comedians, including Aristophanes, commented on Socrates. His most important comedy with respect to Socrates, Clouds, where Socrates is a central character of the play, is the only one to survive today.[21] Aristophanes limns a caricature of Socrates that leans towards sophistism,[22] ridiculing Socrates as a crazy atheist.[23] Socrates in Cloulds is interested in natural philosophy, something which is consisted with Plato's Phaedo claiming likewise. What is certain, is that by age 42, Socrates had already capture the interest of Athenians as a philosopher.[24] Current literature does not deem Aristophanes's work as helpful to reconstruct the historical Socrates, except with respect to some characteristics of his personality.[25]

Other ancient authors on Socrates were Aeschines of Sphettus, Antisthenes, Aristippus, Bryson, Cebes, Crito, Euclid of Megara, and Phaedo; all of whom wrote after Socrates's death.[26] Aristotle was not a contemporary of Socrates; he studied under Plato at the latter's Academy for twenty years.[27] Aristotle treats Socrates without the bias of Xenophon and Plato, who had an emotional bias in favor of Socrates—he scrutinizes Socrates's doctrines as a philosopher.[28] Aristotle was familiar with the various written and unwritten stories of Socrates.[29]

Socratic problem

In a seminal work of 1818, philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher attacked Xenophon's accounts, and his attack was widely accepted and gave rise to the Socratic problem.[30] Schleiermacher criticized Xenophon on his naïve representation of Socrates—the latter was a soldier and was unable to articulate Socratic ideas. Further, Xenophon is biased in favor of his friend, believing Socrates was unfairly treated by Athens, and sought to prove his points of view rather than reconstruct an impartial account—with the result being the portrayal of an uninspiring philosopher.[31] By early 20th century, Xenophon's account was largely rejected.[32]

Philosopher professor Karl Joel, based on Aristotle interpretation of Socratic logos, suggested that Socratic Dialogues are mostly fictional since various authors were just mimicking some Socratic traits of dialogue.[33] Joel's view was dominant among scholars in the first half of 20th century, until philosophers Olof Gigon and Eugène Dupréel at the middle of 20th century propose that our study should focus to the various version of Socrates instead of aiming to reconstruct historical Socrates.[34] Later, Gregory Vlastos suggested that early Plato writings are more compatible with historical Socrates than later writings, an argument based on inconsistencies detected on Plato's Socrates; Vlastos totally disregarded Xenophon's account apart when he was confirming Plato.[34] More recently, Charles H. Kahn, continued the sceptic stance on the unsolvable Socratic Problem, suggesting that only Apology has some historical signifance.[35]

Biography

Socrates was born in 469 or 470 BC in Alopece, a deme of Athens, with both of his parents, Sophroniscus and Phaenarete being wealthy Athenians, thus he was an Athenian citizen.[37] Sophroniscus was a stoneworker while Phaenarete was a midwife.[38] He was raised living close to his father's relatives and inherited, as it was the custom in Ancient Athens, part of his father estate, that secured a life without financial scourges.[39] His education was according to laws and custums of Athens, he learned the basic skills to read and write, as all Athenians and also, as most wealthy Athenians received extra lessons in various other fields such as gymnastic, poetry and music.[40] He married once or twice. One of his marriages was with Xanthippe when Socrates was in his 50s, the other one might have been with the daughter of Aristides, an Athenian statesman.[41] He had 3 sons with Xanthippe.[42] Socrates fulfilled his military service during the Peloponnesian War and distinguished in three campaigns.[36]

During 406 Socrates participated as a member of the Boule to the trial of six commanders since his tribe (the Antiochis) comprised the prytany. The generals were accused that they had abandoned the survivors of foundered ships to pursue the defeated Spartan navy. The generals were seen by some to have failed to uphold the most basic of duties, and the people demanded their capital punishment by having them under trial all together- not separately as the law of Athens dictated. While other members of the prytany bow to public pressure, Socrates stand alone not accepting an illegal suggestion.[43]

Another incident that illustrates Socrates attachment to the law, is the arrest of Leon. As Plato describes in his Apology Socrates and four others were summoned to the Tholos, and told by representatives of the oligarchy of the Thirty (the oligarchy began ruling in 404 BC) to go to Salamis to arrest Leon the Salaminian, who was to be brought back to be subsequently executed. However, Socrates was the only one of the five men who chose not to go to Salamis as he was expected to, because he did not want to be involved in what he considered a crime and despite the risk of subsequent retribution from the tyrants.[44]

As a character Socrates was a fascinating man, attracting the interest of Athenian crowd and especially youth like a magnet.[45] He was notoriously ugly—having flat turned-up nose, bulky eyes and a belly—his friends used to joke with his appearance.[46] On top of being ugly, Socrates didn't pay any attention to his personal appearance. He walked barefoot, had only one torn coat and didn't bathe frequently, friends called him "the unwashed". He restrained from excesses such as food and sex despite his high sex drive, also he did consumed much wine but never was he drunk.[47] Socrates was physically attracted by both sexes- common and accepted in ancient Greece- but resisted his passion towards young men as he was interested in educating their souls.[48] Socrates was known for his self control and never sought to gain sexual favors from his disciplines, as it happened with other older men while teaching adolescents.[49] Politically, he was sitting on the fence in terms of the rivalry between the democrats and the oligarchs in the ancient Athens—he criticizes sharply both while they were on power.[50] The character of Socrates as exhibited in Apology, Crito, Phaedo and Symposium concurs with other sources to an extent to which it seems possible to rely on the Platonic Socrates, as demonstrated in the dialogues, as a representation of the actual Socrates as he lived in history.[51]

He died in Athens in 399 BCE after a one day trial for impiety and corruption of the young.[52] He spend his last day at prison, among friends and followers who offered him a route to escape. He died the next morning, after drinking hemlock.[53] He had never left Athens, except for the military campaigns he participated.[54]

Trial of Socrates

In 399 BC, Socrates went on trial for corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens and for impiety.[55] Socrates defended himself but was subsequently found guilty by a jury of 500 male Athenian citizens (280 vs 220 votes).[56] According to the then custom, he proposed a penalty (in his case Socrates offered some money) but jurors declined his offer and commanded the death penalty.[56] The official charges were corrupting youth, worshipping false gods and not worshipping the state religion.[57]

In 404 BC, Athenians were crushed by Spartans at the decisive naval Battle of Aegospotami, and subsequently, Spartans sieged Athens. They replaced the democratic government with a new, pro-oligarchic government, named the Thirty Tyrants.[58] Because of their tyrannical measures, some Athenians organized to overthrow the Tyrants – and indeed they managed in doing so briefly – but as the Spartan request for aid from the Thirty arrived, a compromise was sought. But as Spartans left again, democrats seized the opportunity to kill the oligarchs and reclaim the government of Athens.[58] Under this politically tense climate in 399, Socrates was charged.[58]

The accusations against Socrates were initiated by a poet, Meletus, who asked for the death penalty because of Asebeia.[58] Other accusers were Anytus and Lycon, of which Anutus was a powerful democratic politician who was despised by Socrates, and his pupils, Critias and Alkiviadis.[58] After a month or two, in late Spring or early Summer, the trial started and lasted a day.[58] The religious charges stood true; indeed Socrates criticized the anthropomorphism of traditional Greek religion, describing it in several cases as a daimonion, an inner voice. [58]

The Socratic apology (meaning the defense of Socrates) started with Socrates answering the various rumors against him that gave rise to the indictment.[59] Firstly, Socrates defended against the rumor that he was an atheist naturalist philosopher, as portrayed in Aristophanes' The Clouds, or being a sophist – a category of professional philosophy teachers notorious for their relativism.[60] Against these corruption allegations, Socrates answered that he did not corrupt anyone intentionally, since corrupting someone would mean that one would be corrupted back, and that corruption is not desirable.[61] On the second charge, Socrates asked for clarification. Meletus, clarified that the accusation was that Socrates was a complete atheist. Socrates was quick to note the contradiction with the next accusation: worshipping false gods.[62] After that, Socrates claimed that he was God's gift, and since his activities ultimately benefited Athens, by condemning him to death, Athens would lose.[63] After that, he claimed that even though no human can reach wisdom, philosophizing is the best thing someone can do, implying money and prestige are not as precious as commonly thought.[64]

Socrates had the chance to offer alternative punishments for himself after being found guilty. He could have requested permission to flee Athens and live in exile, however he didn't bring it up. Instead, according to Plato, he asked for free meals daily, or alternatively, to pay a small fine, while Xenophon says he made no proposals.[66] Jurors decided upon the death penalty, to be carried out the next day.[66] In return, Socrates warned jurors and Athenians that criticism of them, by his many disciplines was inescapable, unless they became good men.[56] Socrates spent his last day in the prison, with his friends visiting him and offering him an escape; however, he declined.[65]

The question of what motivated Athenians to choose to convict Socrates remains a point of controversy among scholars.[67] The two notable theories are, first, that Socrates was convicted on religious grounds and, second, on to political ones.[67] The case for being a political persecution is usually objected to by the existence of the amnesty that was granted in 403 BC to prevent escalation to civil war; but, as the text from Socrates' trial and other texts reveals, the accusers could have fueled their rhetoric using events prior to 403.[68] Also, later, ancient authors claimed in various unrelated events that the prosecution was political. For example, Aeschines of Sphettus (c. 425 – 350 BC) writes: I wonder how one ought to deal with the fact that Alcibiades and Critias were the associates of Socrates, against whom the many and the upper classes made such strong accusations. It is hard to imagine a more pernicious person than Critias, who stood out among the Thirty, the most wicked of the Greeks. People say that these men ought not be used as evidence that Socrates corrupted the youth, nor should their sins be used in any way whatsoever with respect to Socrates, who does not deny carrying on conversations with the young."[69] It was true that Socrates did not stand for democracy during the reign of Thirty, and that most of his pupils were anti-democrats.[70] The argument for religious persecution is supported by the fact that the accounts of the trial by both Plato and Xenophon mostly focused on the charges of impiety. And, while it was true that Socrates didn't believe in Athenian gods, he did not dispute this while he was defending himself. On the other hand, there were many skeptics and atheist philosophers during that time that evaded prosecution, notably demonstrated in the political satire of The Clouds by Aristophanes that was staged years before the trial.[71] Yet another interpretation, more contemporary and more convincing, synthesizes religious and political arguments, since during those times, religion and state were not separated.[72]

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

|

Socratic method

A fundamental characteristic of Plato's Socrates is the Socratic method or method of "elenchus (elenchus or elenchos, in Latin and Greek respectively, means refutation).[73] It is most prominent in the early works of Plato, such as Apology, Crito, Gorgias, Republic I and other.[74] Socrates would initiate a discussion about a topic with a known expert on the topic, then by dialogue will prove them wrong by detecting inconsistencies in his reasoning.[75] Socrates asks his interlocutor for a definition of the subject, then Socrates will ask more questions where the answers of the interlocutor will be in odds with his first definition, with the conclusion the opinion of the expert is wrong.[76] Interlocutor may came up with a different definition which again be placed under the scrutiny of Socrates questions repeatedly, with each round approaching truth even more or realizing the ignorance on the matter.[77] Since the definition of interlocuter represent most commonly, the mainstream opinion on a matter, the discussion places doubt in the shared opinion. Also, another key component of Socratic method, is that he also tests his own opinions, exposing their weakness as with others, thus Socrates is not teaching or even preaching ex cathedra a fixed philosophical doctrine, but rather he humbly acknowledging the man's ignorance while participating himself in searching the truth with his pupils and interlocutors. [78]

Scholars have questioned the validity and the exact nature of socratic method or even if there is one indeed.[79] In 1982, preeminent scholar of ancient philosophy Gregory Vlastos claimed the Socratic Method could not be used to establish truth or falsehood of any particular beliefs. It was simply a potent instrument for exposing inconsistency within an interlocutor's beliefs. [80] There have been two main lines of replying to Vlastos arguments, depending on whether is accepted if Socrates is seeking to prove wrong a claim. .[81] According to the first line, known as the constructivist, Socrates indeed seeks to refute a claim by his method, and it actually helps us reaching positive statements.[82] The non-constructivism approach holds that Socrates merely wants to establish the inconsistency among the premises and conclusion of the initial argument.[83]

Socratic priority of definition

Socrates used to start its discussion with his interlocutor with the search for definitions.[84] Socrates, in most cases, expects for an someone, who claims expertly on a subject, to have knowledge of the definition of his subject, ie Virtue, or Goodness, before further discussing it.[85] Giving definition a priority to any kind of knowledge, is profound in various of his dialogues, as in Hippias Major or Euthyphro.[86] Some scholars thought have argued that Socrates does not endorse this usualness as a principle, either because they can locate examples of not doing so (ie in Laches, when searching examples of courage in order to define it).[87] In this line, Gregory Vlastos, and other scholars, have argued that the endorsement of the priority principle, actually is a platonic endorsement. [88] Philosophy professor Peter Geach who accepts that Socrates endorses the priority of definitions, finds it though fallacious and he comments: "We know heaps of things without being able to define the terms in which we express our knowledge".[89] The debate on the issue is still unsettled.[90]

Socratic ignorance

Plato's Socrates often claims that he is aware of his own lack of knowledge, especially when discussing ethics (such as areté, goodness, courage) since he does not possess the knowledge of essential nature of such concepts.[91] For example, Socrates says during his trial, when his life was at stake: "I thought Evenus a happy man, if he really possesses this art ( technē ), and teaches for so moderate a fee. Certainly I would pride and preen myself if I knew ( epistamai ) these things, but I do not know ( epistamai ) them, gentlemen".[92] In another case, when he was informed that the prestigious Oracle of Delphi declare that there is no-one wiser than Socrates, he concluded "So I withdrew and thought to myself: 'I am wiser ( sophoteron ) than this man; it is likely that neither of us knows ( eidenai ) anything worthwhile, but he thinks he knows something when he does not, whereas when I do not know, neither do I think I know; so I am likely to be wiser than he to this small extent, that I do not think I know what I do not know".[93] But, in some Plato's dialogue, Socrates appears to credit himself with some knowledge and also he seems strongly opinioned which is weird of a man to hold a strong belief when he posses he has no knowledge at all.[94] For example, at his apology, he says "It is perhaps on this point and in this respect, gentlemen, that I differ from the majority of men, and if I were to claim that I am wiser than anyone in anything, it would be in this, that, as I have no adequate knowledge ( ouk eidōs hikanōs ) of things in the underworld, so I do not think I have. I do know ( oida ), however, that it is wicked and shameful to do wrong ( adikein ), to disobey one's superior, be he god or man. I shall never fear or avoid things of which I do not know, whether they may not be good rather than things that I know ( oida ) to be bad."[95]

This antiphasis has puzzled scholars.[96] There are varying explanations of the inconsistency, mostly by interpreting knowledge with a different meaning but there is a consensus that Socrates holds that realizing one's lack of knowledge is the first step towards wisdom.[97] While Socrates claims he acquired cognitive achievement in some domains of knowledge, in most important domains in ethics he denies any wisdom.[98]

Socratic irony

There is a widespread assumption that Socrates is an ironist, this is mostly based on the depiction of Socrates by Plato and Aristotle.[99] Irony of Socrates is so subtle and slightly humorous, that often leaves reader wondering if Socrates is making an intentional pun.[100] Plato's Euthyphro is filled with Socratic irony. The story begins when Socrates, is meeting with Euthyphro, a man that has accused his own father for murder- then turning your father to authorities was pretty unpopular. Socrates bites Euthyphro several times, without his interlocutor understanding the irony of Socrates. When Socrates first hears the details of the story, he comments, "It is not, I think, any random person who could do this [prosecute one's father] correctly, but surely one who is already far progressed in wisdom". When Euthyphro is boasting about his understanding of divinity, Socrates responds "most important that I become your student".[101] Socrates is seen as an ironist ironic commonly when using praises to flatter or when addressing his interlocutors.[102] Socratic irony was detected by Aristotle, but linked to a different meaning. Aristotle used the term eirōneia (a greek world, later latinized and ending up us the english word irony) to describe Socrates self-deprecation. Eironeia, then, contrary to modern meaning, meant to conceal a narrative that was not stated, while today's irony, the message is clear, even though untold literally.[99]

Explanation of why Socrates uses irony divides scholars. The mainstream opinion, since Hellenistic period, perceives irony is adding a playful note to Socrates that grasp the attention of the audience.[103] Another line is that Socrates conceals his philosophical message with irony, making it accessible only to those who can separate what parts of his thought are ironic and what is not.[104] Gregory Vlastos identified a more complex pattern of irony in Socrates, where his words have double meaning, in which one meaning is being ironical, the other is not- an opinion that didn't convinced many other scholars though.[105]

Not everyone were amused by Socratic irony. Epicourians, the only post-Socrates philosophical school in ancient times that didn't identified themselves as antecessors of Socrates, based their criticism to Socrates to his ironic spirit, while they preferred a more direct approach of teaching. Centuries later, Friedrich Nietzsche commented on the same issue: "dialectics lets you act like a tyrant; you humiliate the people you defeat."[106]

Socratic eudaimonism and intellectualism

For Socrates, the pursuit of eudaimonia is the cause of all human action, directedly or indirectly- eudaimonia is a Greek word standing for happiness or well-being.[107] For Socrates, virtue and knowledge are closely linked to eudaimonia- how close Socrates consider this relation, is still debatable. Some argue that Socrates though virtue, knowledge and eudaimonia are identical, another opinion holds that for Socrates virtue serves as a mean to eudaimonism (identical and sufficiency thesis respectively).[108] Another point of debate is whether, according to Socrates, people desire actual good- or rather what they perceive as good.[108]