| Greek deities series |

|---|

| Chthonic deities |

The Erinyes (/ɪˈrɪniˌiːz/; sing. Erinys /ɪˈrɪnɪs/, /ɪˈraɪnɪs/;[1] Greek: Ἐρινύες, pl. of Ἐρινύς, Erinys),[2] also known as the Furies, were female chthonic deities of vengeance in ancient Greek religion and mythology. A formulaic oath in the Iliad invokes them as "the Erinyes, that under earth take vengeance on men, whosoever hath sworn a false oath".[3] Walter Burkert suggests that they are "an embodiment of the act of self-cursing contained in the oath".[4] They correspond to the Dirae in Roman mythology.[5] The Roman writer Maurus Servius Honoratus wrote (ca. 600 AD) that they are called "Eumenides" in hell, "Furiae" on earth, and "Dirae" in heaven.[6][7]

According to Hesiod's Theogony, when the Titan Cronus castrated his father, Uranus, and threw his genitalia into the sea, the Erinyes (along with the Giants and the Meliae) emerged from the drops of blood which fell on the earth (Gaia), while Aphrodite was born from the crests of sea foam.[8] According to variant accounts,[9] they emerged from an even more primordial level—from Nyx ("Night"), or from a union between air and mother earth,[10] while in Virgil's Aeneid, they are daughters of Pluto (Hades)[11] and Nox (Nyx). [12] Their number is usually left indeterminate. Virgil, probably working from an Alexandrian source, recognized three: Alecto or Alekto ("endless anger"), Megaera ("jealous rage"), and Tisiphone or Tilphousia ("vengeful destruction"), all of whom appear in the Aeneid. Dante Alighieri followed Virgil in depicting the same three-character triptych of Erinyes; in Canto IX of the Inferno they confront the poets at the gates of the city of Dis. Whilst the Erinyes were usually described as three maiden goddesses, the Erinys Telphousia was usually a by-name for the wrathful goddess Demeter, who was worshipped under the title of Erinys in the Arkadian town of Thelpousa.

Etymology

The word Erinyes is of uncertain etymology; connections with the verb ὀρίνειν orinein, "to raise, stir, excite", and the noun ἔρις eris, "strife" have been suggested; Beekes, pp. 458–459, has proposed a Pre-Greek origin. The word Erinys in the singular and as a theonym is first attested in Mycenaean Greek, written in Linear B, in the following forms: 𐀁𐀪𐀝, e-ri-nu, and 𐀁𐀪𐀝𐀸, e-ri-nu-we. These words are found on the KN Fp 1, KN V 52,[13] and KN Fh 390 tablets.[14]

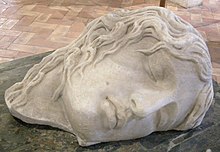

Description

The Erinyes live in Erebus and are more ancient than any of the Olympian deities. Their task is to hear complaints brought by mortals against the insolence of the young to the aged, of children to parents, of hosts to guests, and of householders or city councils to suppliants—and to punish such crimes by hounding culprits relentlessly. The Erinyes are crones and, depending upon authors, described as having snakes for hair, dog's heads, coal black bodies, bat's wings, and blood-shot eyes. In their hands they carry brass-studded scourges, and their victims die in torment.[15]

The Erinyes are commonly associated with night and darkness. With varying accounts claiming that they are the daughters of Nyx, the goddess of night, they're also associated with darkness in the works of Aeschylus and Euripides in both their physical appearance and the time of day that they manifest. [16]

Description of Tishiphone in Statius Thebaid

So prayed he, and the cruel goddess turned her grim visage to hearken. By chance she sat beside dismal Cocytus, and had loosed the snakes from her head and suffered them to lap the sulphurous waters. Straightway, faster than fire of Jove or falling stars she leapt up from the gloomy bank: the crowd of phantoms gives way before her, fearing to meet their queen; then, journeying through the shadows and the fields dark with trooping ghosts, she hastens to the gate of Taenarus, whose threshold none may cross and again return. Day felt her presence, Night interposed her pitchy cloud and startled his shining steeds; far off towering Atlas shuddered and shifted the weight of heaven upon his trembling shoulders. Forthwith rising aloft from Malea’s vale she hies her on the well-known way to Thebes: for on no errand is she swifter to go and to return, not kindred Tartarus itself pleases her so well. A hundred horned snakes erect shaded her face, the thronging terror of her awful head; deep within her sunken eyes there glows a light of iron hue, as when Atracian spells make travailing Phoebe redden through the clouds; suffused with venom, her skin distends and swells with corruption; a fiery vapour issues from her evil mouth, bringing upon mankind thirst unquenchable and sickness and famine and universal death. From her shoulders falls a stark and grisly robe, whose dark fastenings meet upon her breast: Atropos and Proserpine herself fashion her this garb anew. Then both her hands are shaken in wrath, the one gleaming with a funeral torch, the other lashing the air with a live water-snake.[17]

Three sisters

According to Hesiod, the Furies sprang forth from the spilled blood of Uranus when he was castrated by his son Cronus.[18] According to Aeschylus' Oresteia, they are the daughters of Nyx, in Virgil's version, they are daughters of Pluto (Hades) and Nox (Nyx).[19] In some accounts, they were the daughters of Euonymè (a name for Earth) and Cronus,[20] or of Earth and Phorkys (i.e. the sea)[21]

Cult

Pausanias describes a sanctuary in Athens dedicated to the Erinyes under the name Semnai:

Hard by [the Areopagos the murder court of Athens] is a sanctuary of the goddesses which the Athenians call the August, but Hesiod in the Theogony calls them Erinyes (Furies). It was Aeschylus who first represented them with snakes in their hair. But on the images neither of these nor of any of the under-world deities is there anything terrible. There are images of Pluto, Hermes, and Earth, by which sacrifice those who have received an acquittal on the Hill of Ares; sacrifices are also offered on other occasions by both citizens and aliens.

The Orphic Hymns, a collection of 87 religious poems as translated by Thomas Taylor, contains two stanzas regarding the Erinyes. Hymn 68 refers to them as the Erinyes, while hymn 69 refers to them as the Eumenides.[22]

Hymn 68, to the Erinyes:

Vociferous Bacchanalian Furies [Erinyes], hear! Ye, I invoke, dread pow'rs, whom all revere; Nightly, profound, in secret who retire, Tisiphone, Alecto, and Megara dire: Deep in a cavern merg'd, involv'd in night, near where Styx flows impervious to the sight; Ever attendant on mysterious rites, furious and fierce, whom Fate's dread law delights; Revenge and sorrows dire to you belong, hid in a savage veil, severe and strong, Terrific virgins, who forever dwell endu'd with various forms, in deepest hell; Aerial, and unseen by human kind, and swiftly coursing, rapid as the mind. In vain the Sun with wing'd refulgence bright, in vain the Moon, far darting milder light, Wisdom and Virtue may attempt in vain; and pleasing, Art, our transport to obtain Unless with these you readily conspire, and far avert your all-destructive ire. The boundless tribes of mortals you descry, and justly rule with Right's [Dike's] impartial eye. Come, snaky-hair'd, Fates [Moirai] many-form'd, divine, suppress your rage, and to our rites incline.[23]

Hymn 69, to the Eumenides:

Hear me, illustrious Furies [Eumenides], mighty nam'd, terrific pow'rs, for prudent counsel fam'd; Holy and pure, from Jove terrestrial [Zeus Khthonios](Hades) born and Proserpine [Phersephone], whom lovely locks adorn: Whose piercing sight, with vision unconfin'd, surveys the deeds of all the impious kind: On Fate attendant, punishing the race (with wrath severe) of deeds unjust and base. Dark-colour'd queens, whose glittering eyes, are bright with dreadful, radiant, life-destroying, light: Eternal rulers, terrible and strong, to whom revenge, and tortures dire belong; Fatal and horrid to the human sight, with snaky tresses wand'ring in the night; Either approach, and in these rites rejoice, for ye, I call, with holy, suppliant voice.[24]

In ancient Greek literature

Myth fragments dealing with the Erinyes are found among the earliest extant records of ancient Greek culture. The Erinyes are featured prominently in the myth of Orestes, which recurs frequently throughout many works of ancient Greek literature.

Aeschylus

Featured in ancient Greek literature, from poems to plays, the Erinyes form the Chorus and play a major role in the conclusion of Aeschylus's dramatic trilogy the Oresteia. In the first play, Agamemnon, King Agamemnon returns home from the Trojan War, where he is slain by his wife, Clytemnestra, who wants vengeance for her daughter Iphigenia, whom Agamemnon had sacrificed to obtain favorable winds to sail to Troy. In the second play, The Libation Bearers, their son Orestes has reached manhood and has been commanded by Apollo's oracle to avenge his father's murder at his mother's hand. Returning home and revealing himself to his sister Electra, Orestes pretends to be a messenger bringing the news of his own death to Clytemnestra. He then slays his mother and her lover Aegisthus. Although Orestes' actions were what Apollo had commanded him to do, Orestes has still committed matricide, a grave sacrilege.[25] Because of this, he is pursued and tormented by the terrible Erinyes, who demand yet further blood vengeance.[26]

In The Eumenides, Orestes is told by Apollo at Delphi that he should go to Athens to seek the aid of the goddess Athena. In Athens, Athena arranges for Orestes to be tried by a jury of Athenian citizens, with her presiding. The Erinyes appear as Orestes' accusers, while Apollo speaks in his defense. The trial becomes a debate about the necessity of blood vengeance, the honor that is due to a mother compared to that due to a father, and the respect that must be paid to ancient deities such as the Erinyes compared to the newer generation of Apollo and Athena. The jury vote is evenly split. Athena participates in the vote and chooses for acquittal. Athena declares Orestes acquitted because of the rules she established for the trial.[27] Despite the verdict, the Erinyes threaten to torment all inhabitants of Athens and to poison the surrounding countryside. Athena, however, offers the ancient goddesses a new role, as protectors of justice, rather than vengeance, and of the city. She persuades them to break the cycle of blood for blood (except in the case of war, which is fought for glory, not vengeance). While promising that the goddesses will receive due honor from the Athenians and Athena, she also reminds them that she possesses the key to the storehouse where Zeus keeps the thunderbolts that defeated the other older deities. This mixture of bribes and veiled threats satisfies the Erinyes, who are then led by Athena in a procession to their new abode. In the play, the "Furies" are thereafter addressed as "Semnai" (Venerable Ones), as they will now be honored by the citizens of Athens and ensure the city's prosperity.[28]

Euripides

In Euripides' Orestes the Erinyes are for the first time "equated" with the Eumenides[29] (Εὐμενίδες, pl. of Εὐμενίς; literally "the gracious ones", but also translated as "Kindly Ones").[30] This is because it was considered unwise to mention them by name (for fear of attracting their attention); the ironic name is similar to how Hades, god of the dead is styled Pluton, or Pluto, "the Rich One".[15] Using euphemisms for the names of deities serves many religious purposes.

Sophocles

In Sophocles's play, Oedipus at Colonus, it is significant that Oedipus comes to his final resting place in the grove dedicated to the Erinyes. It shows that he has paid his penance for his blood crime, as well as come to integrate the balancing powers to his early over-reliance upon Apollo, the god of the individual, the sun, and reason. He is asked to make an offering to the Erinyes and complies, having made his peace.[original research?]

The Remorse of Orestes, where he is surrounded by the Erinyes, by William-AdolpheBouguereau, 1862

Orestes

In Greek mythology, Orestes or Orestis (/ɒˈrɛstiːz/; Greek: Ὀρέστης [oréstɛːs]) was the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, and the brother of Electra. He is the subject of several Ancient Greek plays and of various myths connected with his madness and purification, which retain obscure threads of much older ones.[1]

Etymology

The Greek name Ὀρέστης, having become "Orestēs" in Latin and its descendants, is derived from Greek ὄρος (óros, “mountain”) and ἵστημι (hístēmi, “to stand”), and so can be thought to have the meaning "stands on a mountain".

Greek literature

Homer

In the Homeric telling of the story,[2] Orestes is a member of the doomed house of Atreus, which is descended from Tantalus and Niobe. He is absent from Mycenae when his father, Agamemnon, returns from the Trojan War with the Trojan princess Cassandra as his concubine, and thus not present for Agamemnon's murder by Aegisthus, the lover of his wife, Clytemnestra. Seven years later, Orestes returns from Athens and avenges his father's death by slaying both Aegisthus and his own mother Clytemnestra.[3]

In the Odyssey, Orestes is held up as a favorable example to Telemachus, whose mother Penelope is plagued by suitors.[4]

Pindar

According to Pindar, the young Orestes was saved by his nurse Arsinoe (Laodamia) or his sister Electra, who conveyed him out of the country when Clytemnestra wished to kill him.

In the familiar theme of the hero's early eclipse and exile, he escaped to Phanote on Mount Parnassus, where King Strophius took charge of him.

In his twentieth year, he was urged by Electra to return home and avenge his father's death. He returned home along with his friend Pylades, Strophius's son.

Greek drama

The story of Orestes was the subject of the Oresteia of Aeschylus (Agamemnon, Choephori, Eumenides), of the Electra of Sophocles, and of the Electra, Iphigeneia in Tauris, Iphigenia at Aulis and Orestes, all of Euripides.

Aeschylus

In Aeschylus's Eumenides, Orestes goes mad after killing his mother and is pursued by the Erinyes, whose duty it is to punish any violation of the ties of family piety. He takes refuge in the temple at Delphi; but, even though Apollo had ordered him to kill his mother, the god is powerless to protect Orestes from the consequences. At last Athena receives him on the Acropolis of Athens and arranges a formal trial of the case before twelve judges, including herself. The Erinyes demand their victim; Oreste asserts that he was acting the orders of Apollo. Upon closing of the trial, Athena votes on the verdict last, announcing that she is for acquittal; the votes are counted and the result is a tie, resulting in an acquittal in accordance with the rules previously stipulated by Athena. The Erinyes are propitiated by the establishment of a new ritual, in which they are worshipped as "Semnai Theai", "Venerable Goddesses", and Orestes dedicates an altar to Athena Areia.

Euripides

As Aeschylus tells it, Orestes' punishment for matricide ended after a trial, but according to Euripides, in order to escape the persecutions of the Erinyes, Orestes was ordered by Apollo to go to Tauris, carry off the statue of Artemis that had fallen from the heavens, and bring it to Athens. Oreste traveled to Tauris with Pylades, where the pair were at once imprisoned by the people, among whom the custom was to sacrifice all Greek strangers in honor of Artemis. The priestess of Artemis, whose duty it was to perform the sacrifice, was Orestes' sister Iphigenia. She offered to release him if he would carry home a letter from her to Greece; he refused to go, but he implored Pylades to deliver the letter while he stays to be slain. After a conflict of mutual affection, Pylades at last yielded, but the brother and sister finally recognized each other due to the letter, and all three escaped together, carrying with them the image of Artemis.

Other literature and media

After his return to Greece, Orestes took possession of his father's kingdom of Mycenae (killing Aegisthus' son, Alete) to which were added Argos and Laconia. He was said to have died of a snakebite in Arcadia. His body was conveyed to Sparta for burial (where he was the object of a cult) or, according to a Roman legend, to Aricia, when it was removed to Rome (Servius on Aeneid, ii. 116).

Before the Trojan War, Orestes was to marry his cousin Hermione, daughter of Menelaus and Helen. Things soon changed after Orestes committed matricide: Menelaus then gave his daughter to Neoptolemus, son of Achilles and Deidamia. According to Euripides' play Andromache, Orestes slew Neoptolemus just outside a temple and took off with Hermione. He seized Argos and Arcadia after their thrones had become vacant, becoming ruler of all the Peloponnesus. His son by Hermione, Tisamenus, became ruler after him but was eventually killed by the Heracleidae.

There is extant a Latin epic poem, consisting of about 1000 hexameters, called Orestes Tragoedia, which has been ascribed to Dracontius of Carthage.

Orestes appears also to be a dramatic prototype for all persons whose crime is mitigated by extenuating circumstances. These legends belong to an age when higher ideas of law and of social duty were being established; the implacable blood-feud of primitive society gives place to a fair trial, and in Athens, when the votes of the judges are evenly divided, mercy prevails.

In one version of the story of Telephus, the infant Orestes was kidnapped by King Telephus, who used him as leverage in his demand that Achilles heal him.

According to some sources, Orestes fathered Penthilus by his half-sister, Erigone.

In The History by Herodotus, the Oracle of Delphi foretold that the Spartans could not defeat the Tegeans until they moved the bones of Orestes to Sparta. Lichas discovered the body, which measured 7 cubits long (around 10 feet, or 3.30 meters). Thus Orestes would have been a Giant.

For modern treatments see the Oresteia in the arts and popular culture.

Orestes and Pylades

The relationship between Orestes and Pylades has been presented by some authors of the Roman era (not by classic Greek tragedians) as romantic or homoerotic. A dialogue entitled Erotes ("Affairs of the Heart") and attributed to Lucian compares the merits and advantages of heterosexuality and homoeroticism, and Orestes and Pylades are presented as the principal representatives of homoerotic friendship:

Taking the love god as the mediator of their emotions for each other, they sailed together as it were on the same vessel of life...nor did they restrict their affectionate friendship to the limits of Hellas....as soon as they set foot on the land of the Tauride, the Fury of matricides was there to welcome the strangers, and, when the natives stood around them, the one was struck to the ground by his usual madness and lay there, but Pylades "did wipe away the foam and tend his frame and shelter him with a fine well-woven robe," thus showing the feelings not merely of a lover, but also of a father. But when it had been decided that, while one remained to be killed, the other should depart for Mycenae to bear a letter, each wished to remain for the sake of the other, considering that he himself lived in the survival of his friend. But Orestes refused to take the letter, claiming Pylades was the fitter person to do so, and thus showed himself almost to be the lover rather than the beloved.

In 1734, George Frederic Handel's opera Oreste (based on Giangualberto Barlocci's Roman libretto of 1723), was premiered in London's Covent Garden.

L'Orestie d'Eschyle (1913-1923) is a French-language opera in three parts by Darius Milhaud based on The Oresteia triptych by Aeschylus in a French translation by his collaborator Paul Claudel.[5]