THE WAVERLY NOVELS

By Sir Walter Scott.

Complete in 25 volumes.

This set is 150 YEARS OLD!

Bound in high-quality, Leather bindings.

Raised hubs on the gilded spines.

Marbled end papers.

Engraved frontisplates protected by tissue.

Printed on thick paper with wide margins.

CONDITION: This is a very high quality set of SIR WALTER SCOTT's Waverly Novels. Printed in 1870, in Edinburgh. Complete in 25 volumes. This set is bound in the original bindings from 1870. This is a very high quality set of SIR WALTER SCOTT's Waverly Novels. Complete in 25-volumes with all of the Waverly Novels. An exceptionally high quality set, in VERY GOOD condition overall, with some abrasions and wear to the bindings. All leather and hinges are very supple and strongly attached. Very clean interior appears unread. Very tightly bound these try to close when opened. All hinges are strongly attached. In exceptional condition. Some shelf rubs and abrasions. Some general rubs/wear, as shown. This set is complete. This is a gorgeous antiquarian set.

The leather is supple despite being from the 1800's.

This would make an excellent gift and/or addition to any fine library.

Antiquarian books make a great investment, are only going up in value, and are sure to increase the aura of any room or office!

Waverley Novels

| This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Waverley Novels is a long series of novels by Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832). For nearly a century, they were among the most popular and widely read novels in all of Europe.

Because Scott did not publicly acknowledge authorship until 1827, the series takes its name from Waverley, the first novel of the series released in 1814. The later books bore the words "by the author of Waverley" on their title pages.

The Tales of my Landlord sub-series was not advertised as "by the author of Waverley" and thus is not always included as part of the Waverley Novels series.

Contents

[hide]Order of publication[edit]

| Title | Published | Main setting | Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waverley, or, Tis Sixty Years Since | 1814 | Perthshire (Scotland) | 1745–1746 |

| Guy Mannering, or, The Astrologer | 1815 | Galloway (Scotland) | 1760-5, 1781–2 |

| The Antiquary | 1816 | Angus (Scotland) | 1790s |

| Tales of My Landlord, 1st series: | |||

| The Black Dwarf | 1816 | Scottish Borders | 1707 |

| The Tale of Old Mortality | 1816 | Southern Scotland | 1679–89 |

| Rob Roy | 1818 | Northumberland (England), and the environs of Loch Lomond (Scotland) | 1715–16 |

| Tales of My Landlord, 2nd series: | |||

| The Heart of Midlothian | 1818 | Edinburgh and Richmond, London | 1736 |

| Tales of My Landlord, 3rd series: | |||

| The Bride of Lammermoor | 1819 | East Lothian (Scotland) | 1709–11 |

| A Legend of Montrose | 1819 | Scottish Highlands | 1644-5 |

| Ivanhoe | 1819 | Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire (England) | 1194 |

| The Monastery | 1820 | Scottish Borders | 1547–57 |

| The Abbot | 1820 | Various in Scotland | 1567-8 |

| Kenilworth | 1821 | Berkshire and Warwickshire (England) | 1575 |

| The Pirate | 1822 | Shetland and Orkney | 1690s |

| The Fortunes of Nigel | 1822 | London and Greenwich (England) | 1616–18 |

| Peveril of the Peak | 1822 | Derbyshire, the Isle of Man, and London | 1658–80 |

| Quentin Durward | 1823 | Tours and Péronne (France) Liège (Wallonia/Belgium) | 1468 |

| St. Ronan's Well | 1824 | Southern Scotland | 19th century |

| Redgauntlet | 1824 | Southern Scotland, and Cumberland (England) | 1766 |

| Tales of the Crusaders: | |||

| The Betrothed | 1825 | Wales, and Gloucester (England) | 1187–92 |

| The Talisman | 1825 | Syria | 1191 |

| Woodstock, or, The Cavalier | 1826 | Woodstock and Windsor (England) Brussels, in the Spanish Netherlands | 1652 |

| Chronicles of the Canongate, 2nd series:[1] | |||

| St Valentine's Day, or, The Fair Maid of Perth | 1828 | Perthshire (Scotland) | 1396 |

| Anne of Geierstein, or, The Maiden in the Mist | 1829 | Switzerland and Eastern France | 1474–77 |

| Tales of my Landlord, 4th series: | |||

| Count Robert of Paris | 1831 | Constantinople and Scutari (now in Turkey) | 1097 |

| Castle Dangerous | 1831 | Kirkcudbrightshire (Scotland) | 1307 |

| The Siege of Malta | 2008 | Malta and Southern Spain | 1565 |

Chronological order, by setting[edit]

- 1097: Count Robert of Paris

- 1187–94: The Betrothed, The Talisman, Ivanhoe

- 1307: Castle Dangerous

- 1396: The Fair Maid of Perth

- 1468–77: Quentin Durward, Anne of Geierstein

- 1547–75: The Monastery, The Abbot, Kenilworth, The Siege of Malta

- 1616–18: The Fortunes of Nigel

- 1644–89: A Legend of Montrose, Woodstock, Peveril of the Peak, The Tale of Old Mortality, The Pirate

- 1700–99: The Black Dwarf, The Bride of Lammermoor, Rob Roy, Heart of Midlothian, Waverley, Guy Mannering, Redgauntlet, The Antiquary

- 19th century: St. Ronan's Well

Editions[edit]

Originally printed by James Ballantyne on the Canongate in Edinburgh, brother of one of Scott's close friends, John Ballantyne ("Printed by James Ballantyne and Co. For Archibald Constable and Co., Edinburgh"). Some of the early editions were lavishly illustrated by George Cattermole.

The two definitive editions are the 48-volume set published between 1829 and 1833 by Robert Cadell (the "Magnum Opus"), based on previous editions, with new introductions and appendices by Scott, and the 30-volume set, based on manuscripts, published by the Edinburgh University Press and Columbia University Press in the 1990s.

Placenames[edit]

The towns of Waverly, Nebraska; Waverley, New York; Waverley, Nova Scotia; Waverly, Ohio; and Waverly, Tennessee,[2] take their names from these novels, as does Waverley Station and Waverley Bridge in Edinburgh. Waverley School in Louisville, Kentucky, which later became the Waverly Hills Sanatorium, was named after the novels as well.[3]

Other uses of names[edit]

Many British railway locomotives were given names from the novels.

Over two thousand streets in Britain have names from titles of individual novels, with 650 from Waverley alone.

See also[edit]

Walter Scott

| This article's lead section may not adequately summarize key points of its contents. (February 2017) |

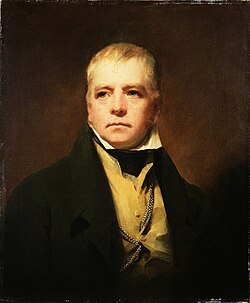

| Sir Walter Scott, Bt | |

|---|---|

Raeburn's portrait of Sir Walter Scott in 1822 | |

| Born | 15 August 1771 College Wynd, Edinburgh Scotland |

| Died | 21 September 1832(aged 61) Abbotsford, Roxburghshire Scotland |

| Occupation | |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Period | 19th century |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Spouse | Charlotte Carpenter (Charpentier) |

| Signature |  |

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet, FRSE (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832) was a Scottish historical novelist, playwright and poet. Many of his works remain classics of both English-language literature and of Scottish literature. Famous titles include Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, Old Mortality, The Lady of the Lake, Waverley, The Heart of Midlothian and The Bride of Lammermoor.

Although primarily remembered for his extensive literary works and his political engagement, Scott was an advocate, judge and legal administrator by profession, and throughout his career combined his writing and editing work with his daily occupation as Clerk of Session and Sheriff-Depute of Selkirkshire.

A prominent member of the Tory establishment in Edinburgh, Scott was an active member of the Highland Society and served a long term as President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1820–32).

Contents

[hide]Life and works[edit]

Early days[edit]

The son of a Writer to the Signet (solicitor),[1] Scott was born in 1771 in his Presbyterian family's third-floor flat on College Wynd in the Old Town of Edinburgh, a narrow alleyway leading from the Cowgate to the gates of the University of Edinburgh(Old College).[2] He survived a childhood bout of polio in 1773 that left him lame,[3] a condition that was to have a significant effect on his life and writing.[4] To cure his lameness he was sent in 1773 to live in the rural Scottish Borders at his paternal grandparents' farm at Sandyknowe, adjacent to the ruin of Smailholm Tower, the earlier family home.[5] Here he was taught to read by his aunt Jenny, and learned from her the speech patterns and many of the tales and legends that characterised much of his work. In January 1775 he returned to Edinburgh, and that summer went with his aunt Jenny to take spa treatment at Bathin England, where they lived at 6 South Parade.[6] In the winter of 1776 he went back to Sandyknowe, with another attempt at a water cure at Prestonpans during the following summer.[5]

In 1778, Scott returned to Edinburgh for private education to prepare him for school, and joined his family in their new house built as one of the first in George Square.[2] In October 1779 he began at the Royal High School of Edinburgh (in High School Yards). He was now well able to walk and explore the city and the surrounding countryside. His reading included chivalric romances, poems, history and travel books. He was given private tuition by James Mitchell in arithmetic and writing, and learned from him the history of the Church of Scotland with emphasis on the Covenanters. After finishing school he was sent to stay for six months with his aunt Jenny in Kelso, attending the local grammar school where he met James and John Ballantyne, who later became his business partners and printed his books.[7]

Meeting with Blacklock and Burns[edit]

Scott began studying classics at the University of Edinburgh in November 1783, at the age of 12, a year or so younger than most of his fellow students. In March 1786 he began an apprenticeship in his father's office to become a Writer to the Signet. While at the university Scott had become a friend of Adam Ferguson, the son of Professor Adam Ferguson who hosted literary salons. Scott met the blind poet Thomas Blacklock, who lent him books and introduced him to James Macpherson's Ossiancycle of poems. During the winter of 1786–87 the 15-year-old Scott saw Robert Burns at one of these salons, for what was to be their only meeting. When Burns noticed a print illustrating the poem "The Justice of the Peace" and asked who had written the poem, only Scott knew that it was by John Langhorne, and was thanked by Burns.[8] When it was decided that he would become a lawyer, he returned to the university to study law, first taking classes in Moral Philosophy and Universal History in 1789–90.[7]

After completing his studies in law, he became a lawyer in Edinburgh. As a lawyer's clerk he made his first visit to the Scottish Highlands directing an eviction. He was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1792. He had an unsuccessful love suit with Williamina Belsches of Fettercairn, who married Scott's friend Sir William Forbes, 7th Baronet.

Start of literary career, marriage and family[edit]

As a boy, youth and young man, Scott was fascinated by the oral traditions of the Scottish Borders. He was an obsessive collector of stories, and developed an innovative method of recording what he heard at the feet of local story-tellers using carvings on twigs, to avoid the disapproval of those who believed that such stories were neither for writing down nor for printing.[9] At the age of 25 he began to write professionally, translating works from German,[10] his first publication being rhymed versions of ballads by Gottfried August Bürger in 1796. He then published an idiosyncratic three-volume set of collected ballads of his adopted home region, The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. This was the first sign from a literary standpoint of his interest in Scottish history.

As a result of his early polio infection, Scott had a pronounced limp. He was described in 1820 as tall, well formed (except for one ankle and foot which made him walk lamely), neither fat nor thin, with forehead very high, nose short, upper lip long and face rather fleshy, complexion fresh and clear, eyes very blue, shrewd and penetrating, with hair now silvery white.[11] Although a determined walker, on horseback he experienced greater freedom of movement. Unable to consider a military career, Scott enlisted as a volunteer in the 1st Lothian and Border yeomanry.[12]

On a trip to the Lake District with old college friends he met Charlotte Genevieve Charpentier (or Carpenter), daughter of Jean Charpentier of Lyon in France, and ward of Lord Downshire in Cumberland, an Episcopalian. After three weeks of courtship, Scott proposed and they were married on Christmas Eve 1797 in St Mary's Church, Carlisle (a church set up in the now destroyed nave of Carlisle Cathedral).[13][14] After renting a house in George Street, they moved to nearby South Castle Street. They had five children, of whom four survived by the time of Scott's death, most baptized by an Episcopalian clergyman. In 1799 he was appointed Sheriff-Depute of the County of Selkirk, based in the Royal Burgh of Selkirk. In his early married days Scott had a decent living from his earnings at the law, his salary as Sheriff-Depute, his wife's income, some revenue from his writing, and his share of his father's rather meagre estate.

After their third son was born in 1801, they moved to a spacious three-storey house built for Scott at 39 North Castle Street. This remained Scott's base in Edinburgh until 1826, when he could no longer afford two homes. From 1798 Scott had spent the summers in a cottage at Lasswade, where he entertained guests including literary figures, and it was there that his career as an author began. There were nominal residency requirements for his position of Sheriff-Depute, and at first he stayed at a local inn during the circuit. In 1804 he ended his use of the Lasswade cottage and leased the substantial house of Ashestiel, 6 miles (9.7 km) from Selkirk. It was sited on the south bank of the River Tweed, and the building incorporated an old tower house.[2]

Scott's father, also Walter (1729–1799), was a Freemason, being a member of Lodge St David, No.36 (Edinburgh), and Scott also became a Freemason in his father's Lodge in 1801, albeit only after the death of his father.[15]

Poetry[edit]

In 1796, Scott's friend James Ballantyne[16] founded a printing press in Kelso, in the Scottish Borders. Through Ballantyne, Scott was able to publish his first works, including "Glenfinlas" and "The Eve of St. John", and his poetry then began to bring him to public attention. In 1805, The Lay of the Last Minstrel captured wide public imagination, and his career as a writer was established in spectacular fashion.

He published many other poems over the next ten years, including the popular The Lady of the Lake, printed in 1810 and set in the Trossachs. Portions of the German translation of this work were set to music by Franz Schubert. One of these songs, "Ellens dritter Gesang", is popularly labelled as "Schubert's Ave Maria".

Beethoven's opus 108 "Twenty-Five Scottish Songs" includes 3 folk songs whose words are by Walter Scott.

Marmion, published in 1808, produced lines that have become proverbial. Canto VI. Stanza 17 reads:

In 1809 Scott persuaded James Ballantyne and his brother to move to Edinburgh and to establish their printing press there. He became a partner in their business. As a political conservative,[18] Scott helped to found the Tory Quarterly Review, a review journal to which he made several anonymous contributions. Scott was also a contributor to the Edinburgh Review, which espoused Whig views.

Scott was ordained as an elder in the Presbyterian Church of Duddington and sat in the General Assembly for a time as representative elder of the burgh of Selkirk.

When the lease of Ashestiel expired in 1811 Scott bought Cartley Hole Farm, on the south bank of the River Tweed nearer Melrose. The farm had the nickname of "Clarty Hole", and when Scott built a family cottage there in 1812 he named it "Abbotsford". He continued to expand the estate, and built Abbotsford House in a series of extensions.[2]

In 1813 Scott was offered the position of Poet Laureate. He declined, due to concerns that "such an appointment would be a poisoned chalice", as the Laureateship had fallen into disrepute, due to the decline in quality of work suffered by previous title holders, ", as a succession of poetasters had churned out conventional and obsequious odes on royal occasions."[19] He sought advice from the Duke of Buccleuch, who counseled him to retain his literary independence, and the position went to Scott's friend, Robert Southey.[20]

Novelism[edit]

Although Scott had attained worldwide celebrity through his poetry, he soon tried his hand at documenting his researches into the oral tradition of the Scottish Borders in prose fiction—stories and novels—at the time still considered aesthetically inferior to poetry (above all to such classical genres as the epic or poetic tragedy) as a mimetic vehicle for portraying historical events. In an innovative and astute action, he wrote and published his first novel, Waverley, anonymously in 1814. It was a tale of the Jacobite rising of 1745. Its English protagonist, Edward Waverley, like Don Quixote a great reader of romances, has been brought up by his Tory uncle, who is sympathetic to Jacobitism, although Edward's own father is a Whig. The youthful Waverley obtains a commission in the Whig army and is posted in Dundee. On leave, he meets his uncle's friend, the Jacobite Baron Bradwardine and is attracted to the Baron's daughter Rose. On a visit to the Highlands, Edward overstays his leave and is arrested and charged with desertion but is rescued by the Highland chieftain Fergus MacIvor and his mesmerizing sister Flora, whose devotion to the Stuart cause, "as it exceeded her brother's in fanaticism, excelled it also in purity". Through Flora, Waverley meets Bonnie Prince Charlie, and under her influence goes over to the Jacobite side and takes part in the Battle of Prestonpans. He escapes retribution, however, after saving the life of a Whig colonel during the battle. Waverley (whose surname reflects his divided loyalties) eventually decides to lead a peaceful life of establishment respectability under the House of Hanover rather than live as a proscribed rebel. He chooses to marry the beautiful Rose Bradwardine, rather than cast his lot with the sublime Flora MacIvor, who, after the failure of the '45 rising, retires to a French convent.

There followed a succession of novels over the next five years, each with a Scottish historical setting. Mindful of his reputation as a poet, Scott maintained the anonymity he had begun with Waverley, publishing the novels under the name "Author of Waverley" or as "Tales of..." with no author. Among those familiar with his poetry, his identity became an open secret, but Scott persisted in maintaining the façade, perhaps because he thought his old-fashioned father would disapprove of his engaging in such a trivial pursuit as novel writing. During this time Scott became known by the nickname "The Wizard of the North". In 1815 he was given the honour of dining with George, Prince Regent, who wanted to meet the "Author of Waverley".

Scott's 1819 series Tales of my Landlord is sometimes considered a subset of the Waverley novels and was intended to illustrate aspects of Scottish regional life. Among the best known is The Bride of Lammermoor, a fictionalized version of an actual incident in the history of the Dalrymple family that took place in the Lammermuir Hills in 1669. In the novel, Lucie Ashton and the nobly born but now dispossessed and impoverished Edgar Ravenswood exchange vows. But the Ravenswoods and the wealthy Ashtons, who now own the former Ravenswood lands, are enemies, and Lucie's mother forces her daughter to break her engagement to Edgar and marry the wealthy Sir Arthur Bucklaw. Lucie falls into a depression and on their wedding night stabs the bridegroom, succumbs to insanity, and dies. In 1821, French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix painted a portrait depicting himself as the melancholy, disinherited Edgar Ravenswood. The prolonged, climactic coloratura mad scene for Lucia in Donizetti's 1835 bel canto opera Lucia di Lammermoor is based on what in the novel were just a few bland sentences.

Tales of my Landlord includes the now highly regarded novel Old Mortality, set in 1679–89 against the backdrop of the ferocious anti-Covenanting campaign of the Tory Graham of Claverhouse, subsequently made Viscount Dundee (called "Bluidy Clavers" by his opponents but later dubbed "Bonnie Dundee" by Scott). The Covenanters were presbyterians who had supported the Restoration of Charles II on promises of a Presbyterian settlement, but he had instead reintroduced Episcopalian church government with draconian penalties for Presbyterian worship. This led to the destitution of around 270 ministers who had refused to take an oath of allegiance and submit themselves to bishops, and who continued to conduct worship among a remnant of their flock in caves and other remote country spots. The relentless persecution of these conventicles and attempts to break them up by military force had led to open revolt. The story is told from the point of view of Henry Morton, a moderate Presbyterian, who is unwittingly drawn into the conflict and barely escapes summary execution. In writing Old Mortality Scott drew upon the knowledge he had acquired from his researches into ballads on the subject for The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.[21] Scott's background as a lawyer also informed his perspective, for at the time of the novel, which takes place before the Act of Union of 1707, English law did not apply in Scotland, and afterwards Scotland has continued to have its own Scots law as a hybrid legal system. A recent critic, who is a legal as well as a literary scholar, argues that Old Mortality not only reflects the dispute between Stuart's absolute monarchy and the jurisdiction of the courts, but also invokes a foundational moment in British sovereignty, namely, the Habeas Corpus Act (also known as the Great Writ), passed by the English Parliament in 1679.[22] Oblique reference to the origin of Habeas corpus underlies Scott's next novel, Ivanhoe, set during the era of the creation of the Magna Carta, which political conservatives like Walter Scott and Edmund Burke regarded as rooted in immemorial British custom and precedent.

Ivanhoe (1819), set in 12th-century England, marked a move away from Scott's focus on the local history of Scotland. Based partly on Hume's History of England and the ballad cycle of Robin Hood, Ivanhoe was quickly translated into many languages and inspired countless imitations and theatrical adaptations. Ivanhoe depicts the cruel tyranny of the Norman overlords (Norman Yoke) over the impoverished Saxon populace of England, with two of the main characters, Rowena and Locksley (Robin Hood), representing the dispossessed Saxon aristocracy. When the protagonists are captured and imprisoned by a Norman baron, Scott interrupts the story to exclaim:

The institution of the Magna Carta, which happens outside the time frame of the story, is portrayed as a progressive (incremental) reform, but also as a step towards the recovery of a lost golden age of liberty endemic to England and the English system. Scott puts a derisive prophecy in the mouth of the jester Wamba:

Although on the surface an entertaining escapist romance, alert contemporary readers would have quickly recognised the political subtext of Ivanhoe, which appeared immediately after the English Parliament, fearful of French-style revolution in the aftermath of Waterloo, had passed the Habeas Corpus Suspension acts of 1817 and 1818 and other extremely repressive measures, and when traditional English Charter rights versus revolutionary human rights was a topic of discussion.[23]

Ivanhoe was also remarkable in its sympathetic portrayal of Jewish characters: Rebecca, considered by many critics the book's real heroine, does not in the end get to marry Ivanhoe, whom she loves, but Scott allows her to remain faithful to her own religion, rather than having her convert to Christianity. Likewise, her father, Isaac of York, a Jewish moneylender, is shown as a victim rather than a villain. In Ivanhoe, which is one of Scott's Waverley novels, religious and sectarian fanatics are the villains, while the eponymous hero is a bystander who must weigh the evidence and decide where to take a stand. Scott's positive portrayal of Judaism, which reflects his humanity and concern for religious toleration, also coincided with a contemporary movement for the Emancipation of the Jews in England.

Recovery of the Crown Jewels, baronetcy and ceremonial pageantry[edit]

Scott's fame grew as his explorations and interpretations of Scottish history and society captured popular imagination. Impressed by this, the Prince Regent (the future George IV) gave Scott permission to conduct a search for the Crown Jewels ("Honours of Scotland"). During the years of the Protectorate under Cromwell the Crown Jewels had been hidden away, but had subsequently been used to crown Charles II. They were not used to crown subsequent monarchs, but were regularly taken to sittings of Parliament, to represent the absent monarch, until the Act of Union 1707. Thereafter, the honours were stored in Edinburgh Castle, but the large locked box in which they were stored was not opened for more than 100 years, and stories circulated that they had been "lost" or removed. In 1818, Scott and a small team of military men opened the box, and "unearthed" the honours from the Crown Room in the depths of Edinburgh Castle. A grateful Prince Regent granted Scott the title of baronet,[24] and in March 1820 he received the baronetcy in London, becoming Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet.[25]

After George's accession to the throne, the city council of Edinburgh invited Scott, at the King's behest, to stage-manage the 1822 visit of King George IV to Scotland.[24] With only three weeks for planning and execution, Scott created a spectacular and comprehensive pageant, designed not only to impress the King, but also in some way to heal the rifts that had destabilised Scots society. He used the event to contribute to the drawing of a line under an old world that pitched his homeland into regular bouts of bloody strife. He, along with his "production team", mounted what in modern days could be termed a PR event, in which the King was dressed in tartan, and was greeted by his people, many of whom were also dressed in similar tartan ceremonial dress. This form of dress, proscribed after the 1745 rebellion against the English, became one of the seminal, potent and ubiquitous symbols of Scottish identity.[26]

In his novel Kenilworth, Elizabeth I is welcomed to the castle of that name by means of an elaborate pageant, the details of which Scott was well qualified to itemize.

Much of Scott's autograph work shows an almost stream-of-consciousness approach to writing. He included little in the way of punctuation in his drafts, leaving such details to the printers to supply.[27] He eventually acknowledged in 1827 that he was the author of the Waverley Novels.[26]

Financial problems and death[edit]

In 1825 a UK-wide banking crisis resulted in the collapse of the Ballantyne printing business, of which Scott was the only partner with a financial interest; the company's debts of £130,000 (equivalent to £9,600,000 in 2015) caused his very public ruin.[28] Rather than declare himself bankrupt, or to accept any kind of financial support from his many supporters and admirers (including the king himself), he placed his house and income in a trust belonging to his creditors, and determined to write his way out of debt. He kept up his prodigious output of fiction, as well as producing a biography of Napoleon Bonaparte, until 1831. By then his health was failing, but he nevertheless undertook a grand tour of Europe, and was welcomed and celebrated wherever he went. He returned to Scotland and, in September 1832, during the epidemic in Scotland that year, died of typhus[29] at Abbotsford, the home he had designed and had built, near Melrose in the Scottish Borders. (His wife, Lady Scott, had died in 1826 and was buried as an Episcopalian.) Two Presbyterian ministers and one Episcopalian officiated at his funeral.[30] Scott died owing money, but his novels continued to sell, and the debts encumbering his estate were discharged shortly after his death.[28]

Personal life[edit]

Scott's eldest son Lt Walter Scott, inherited his father's estate and possessions. He married Jane Jobson, only daughter of William Jobson of Lochore (died 1822) and his wife Rachel Stuart (died 1863) on 3 February 1825.[31]

Scott, Sr.'s lawyer from at least 1814 was Hay Donaldson WS (died 1822), who was also agent to the Duke of Buccleuch. Scott was Donaldson's proposer when he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[32]

Abbotsford[edit]

When Scott was a boy, he sometimes travelled with his father from Selkirk to Melrose, where some of his novels are set. At a certain spot the old gentleman would stop the carriage and take his son to a stone on the site of the Battle of Melrose (1526).[33]

During the summers from 1804, Scott made his home at the large house of Ashestiel, on the south bank of the River Tweed 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Selkirk. When his lease on this property expired in 1811, Scott bought Cartley Hole Farm, downstream on the Tweed nearer Melrose. The farm had the nickname of "Clarty Hole", and when Scott built a family cottage there in 1812 he named it "Abbotsford". He continued to expand the estate, and built Abbotsford House in a series of extensions.[2] The farmhouse developed into a wonderful home that has been likened to a fairy palace. Scott was a pioneer of the Scottish Baronial style of architecture, therefore Abbotsford is festooned with turrets and stepped gabling. Through windows enriched with the insignia of heraldry the sun shone on suits of armour, trophies of the chase, a library of more than 9,000 volumes, fine furniture, and still finer pictures. Panelling of oak and cedar and carved ceilings relieved by coats of arms in their correct colours added to the beauty of the house.[34][verification needed]

It is estimated that the building cost Scott more than £25,000 (equivalent to £1,900,000 in 2015). More land was purchased until Scott owned nearly 1,000 acres (4.0 km2). A Roman road with a ford near Melrose used in olden days by the abbots of Melrose suggested the name of Abbotsford. Scott was buried in Dryburgh Abbey, where his wife had earlier been interred. Nearby is a large statue of William Wallace, one of Scotland's many romanticised historical figures.[35] Abbotsford later gave its name to the Abbotsford Club, founded in 1834 in memory of Sir Walter Scott.[36]

Legacy[edit]

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Toryism |

|---|

|

Later assessment[edit]

Although he continued to be extremely popular and widely read, both at home and abroad,[37] Scott's critical reputation declined in the last half of the 19th century as serious writers turned from romanticism to realism, and Scott began to be regarded as an author suitable for children. This trend accelerated in the 20th century. For example, in his classic study Aspects of the Novel (1927), E. M. Forster harshly criticized Scott's clumsy and slapdash writing style, "flat" characters, and thin plots. In contrast, the novels of Scott's contemporary Jane Austen, once appreciated only by the discerning few (including, as it happened, Sir Walter Scott himself) rose steadily in critical esteem, though Austen, as a female writer, was still faulted for her narrow ("feminine") choice of subject matter, which, unlike Scott, avoided the grand historical themes traditionally viewed as masculine.

Nevertheless, Scott's importance as an innovator continued to be recognized. He was acclaimed as the inventor of the genre of the modern historical novel (which others trace to Jane Porter, whose work in the genre predates Scott's) and the inspiration for enormous numbers of imitators and genre writers both in Britain and on the European continent. In the cultural sphere, Scott's Waverley novels played a significant part in the movement (begun with James Macpherson's Ossian cycle) in rehabilitating the public perception of the Scottish Highlands and its culture, which had been formally suppressed as barbaric, and viewed in the southern mind as a breeding ground of hill bandits, religious fanaticism, and Jacobite rebellions. Scott served as chairman of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and was also a member of the Royal Celtic Society. His own contribution to the reinvention of Scottish culture was enormous, even though his re-creations of the customs of the Highlandswere fanciful at times, despite his extensive travels around his native country. It is a testament to Scott's contribution in creating a unified identity for Scotland that Edinburgh's central railway station, opened in 1854 by the North British Railway, is called Waverley. The fact that Scott was a Lowland Presbyterian, rather than a Gaelic-speaking Catholic Highlander, made him more acceptable to a conservative English reading public. Scott's novels were certainly influential in the making of the Victorian craze for all things Scottish among British royalty, who were anxious to claim legitimacy through their rather attenuated historical connection with the royal house of Stuart.[citation needed]

At the time Scott wrote, Scotland was poised to move away from an era of socially divisive clan warfare to a modern world of literacy and industrial capitalism. Through the medium of Scott's novels, the violent religious and political conflicts of the country's recent past could be seen as belonging to history—which Scott defined, as the subtitle of Waverley ("'Tis Sixty Years Since") indicates, as something that happened at least 60 years ago. Scott's advocacy of objectivity and moderation and his strong repudiation of political violence on either side also had a strong, though unspoken, contemporary resonance in an era when many conservative English speakers lived in mortal fear of a revolution in the French style on British soil. Scott's orchestration of King George IV's visit to Scotland, in 1822, was a pivotal event intended to inspire a view of his home country that, in his view, accentuated the positive aspects of the past while allowing the age of quasi-medieval blood-letting to be put to rest, while envisioning a more useful, peaceful future.

After Scott's work had been essentially unstudied for many decades, a revival of critical interest began from the 1960s. Postmoderntastes favoured discontinuous narratives and the introduction of the "first person", yet they were more favourable to Scott's work than Modernist tastes. While F. R. Leavis had disdained Scott, seeing him as a thoroughly bad novelist and a thoroughly bad influence (The Great Tradition [1948]), György Lukács (The Historical Novel [1937, trans. 1962]) and David Daiches (Scott's Achievement as a Novelist [1951]) offered a Marxian political reading of Scott's fiction that generated a great deal of genuine interest in his work. Scott is now seen as an important innovator and a key figure in the development of Scottish and world literature, and particularly as the inventor of the historical novel.[38]

Memorials and commemoration[edit]

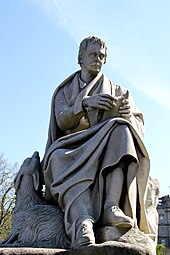

During his lifetime, Scott's portrait was painted by Sir Edwin Landseer and fellow-Scots Sir Henry Raeburn and James Eckford Lauder. In Edinburgh, the 61.1-metre-tall Victorian Gothic spire of the Scott Monument was designed by George Meikle Kemp. It was completed in 1844, 12 years after Scott's death, and dominates the south side of Princes Street. Scott is also commemorated on a stone slab in Makars' Court, outside The Writers' Museum, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh, along with other prominent Scottish writers; quotes from his work are also visible on the Canongate Wall of the Scottish Parliament building in Holyrood. There is a tower dedicated to his memory on Corstorphine Hill in the west of the city and, as mentioned, Edinburgh's Waverley railway station takes its name from one of his novels.

In Glasgow, Walter Scott's Monument dominates the centre of George Square, the main public square in the city. Designed by David Rhind in 1838, the monument features a large column topped by a statue of Scott.[39] There is a statue of Scott in New York City's Central Park.[40]

Numerous Masonic Lodges have been named after him and his novels. For example: Lodge Sir Walter Scott, No.859, (Perth, Australia) and Lodge Waverly, No.597, (Edinburgh, Scotland).[41]

The annual Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction was created in 2010 by the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch, whose ancestors were closely linked to Sir Walter Scott. At £25,000 it is one of the largest prizes in British literature. The award has been presented at Scott's historic home, Abbotsford House.

Scott has been credited with rescuing the Scottish banknote. In 1826, there was outrage in Scotland at the attempt of Parliament to prevent the production of banknotes of less than five pounds. Scott wrote a series of letters to the Edinburgh Weekly Journal under the pseudonym "Malachi Malagrowther" for retaining the right of Scottish banks to issue their own banknotes. This provoked such a response that the Government was forced to relent and allow the Scottish banks to continue printing pound notes. This campaign is commemorated by his continued appearance on the front of all notes issued by the Bank of Scotland. The image on the 2007 series of banknotes is based on the portrait by Henry Raeburn.[42]

During and immediately after World War I there was a movement spearheaded by President Wilson and other eminent people to inculcate patriotism in American school children, especially immigrants, and to stress the American connection with the literature and institutions of the "mother country" of Great Britain, using selected readings in middle school textbooks.[43] Scott's Ivanhoe continued to be required reading for many American high school students until the end of the 1950s.

Literature by other authors[edit]

In Charles Baudelaire's La Fanfarlo (1847), poet Samuel Cramer says of Scott:

In the novella, however, Cramer proves as deluded a romantic as any hero in one of Scott's novels.[44]

In Anne Brontë's The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) the narrator, Gilbert Markham, brings an elegantly bound copy of Marmion as a present to the independent "tenant of Wildfell Hall" (Helen Graham) whom he is courting, and is mortified when she insists on paying for it.

In a speech delivered at Salem, Massachusetts, on 6 January 1860, to raise money for the families of the executed abolitionist John Brown and his followers, Ralph Waldo Emerson calls Brown an example of true chivalry, which consists not in noble birth but in helping the weak and defenseless and declares that "Walter Scott would have delighted to draw his picture and trace his adventurous career".[45]

In his 1870 memoir, Army Life in a Black Regiment, New England abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson (later editor of Emily Dickinson), described how he wrote down and preserved Negro spirituals or "shouts" while serving as a colonel in the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first authorized Union Army regiment recruited from freedmen during the Civil War (memorialized in the 1989 film Glory). He wrote that he was "a faithful student of the Scottish ballads, and had always envied Sir Walter the delight of tracing them out amid their own heather, and of writing them down piecemeal from the lips of aged crones".

According to his daughter Eleanor, Scott was "an author to whom Karl Marx again and again returned, whom he admired and knew as well as he did Balzac and Fielding".[46]

In his 1883 Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain satirized the impact of Scott's writings, declaring (with humorous hyperbole) that Scott "had so large a hand in making Southern character, as it existed before the [American Civil] war", that he is "in great measure responsible for the war".[47] He goes on to coin the term "Sir Walter Scott disease", which he blames for the South's lack of advancement. Twain also targeted Scott in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, where he names a sinking boat the "Walter Scott" (1884); and, in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889), the main character repeatedly utters "great Scott" as an oath; by the end of the book, however, he has become absorbed in the world of knights in armor, reflecting Twain's ambivalence on the topic.

The idyllic Cape Cod retreat of suffragists Verena Tarrant and Olive Chancellor in Henry James' The Bostonians (1886) is called Marmion, evoking what James considered the Quixotic idealism of these social reformers.

In To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Ramsey glances at her husband:

In 1951, science-fiction author Isaac Asimov wrote Breeds There a Man...?, a short story with a title alluding vividly to Scott's The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805).

In To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), the protagonist's brother is made to read Walter Scott's book Ivanhoe to the ailing Mrs. Henry Lafayette Dubose, and he refers to the author as "Sir Walter Scout", in reference to his own sister's nickname.

In Mother Night (1961) by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., memoirist and playwright Howard W. Campbell, Jr., prefaces his text with the six lines beginning "Breathes there the man..."

In Knights of the Sea (2010) by Canadian author Paul Marlowe, there are several quotes from and references to Marmion, as well as an inn named after Ivanhoe, and a fictitious Scott novel entitled The Beastmen of Glen Glammoch.

Bibliography[edit]

Novels[edit]

The Waverley Novels is the title given to the long series of Scott novels released from 1814 to 1832 which takes its name from the first novel, Waverley. The following is a chronological list of the entire series:

- 1814: Waverley

- 1815: Guy Mannering

- 1816: The Antiquary

- 1816: The Black Dwarf and The Tale of Old Mortality – the 1st installment from the subset series, Tales of My Landlord

- 1817: Rob Roy

- 1818: The Heart of Midlothian – the 2nd installment from the subset series, Tales of My Landlord

- 1819: The Bride of Lammermoor and A Legend of Montrose – the 3rd installment from the subset series, Tales of My Landlord

- 1820: Ivanhoe

- 1820: The Monastery and The Abbot – from the subset series, Tales from Benedictine Sources

- 1821: Kenilworth

- 1822: The Pirate

- 1822: The Fortunes of Nigel

- 1822: Peveril of the Peak

- 1823: Quentin Durward

- 1824: St. Ronan's Well

- 1824: Redgauntlet

- 1825: The Betrothed and The Talisman – from the subset series, Tales of the Crusaders

- 1826: Woodstock

- 1828: The Fair Maid of Perth – the 2nd installment from the subset series, Chronicles of the Canongate (sometimes not considered as part of the Waverley Novelsseries)

- 1829: Anne of Geierstein

- 1832: Count Robert of Paris and Castle Dangerous – the 4th installment from the subset series, Tales of My Landlord

Other novels:

- 1831–1832: The Siege of Malta – a finished novel published posthumously in 2008

- 1832: Bizarro – an unfinished novel (or novella) published posthumously in 2008

Poetry[edit]

Many of the short poems or songs released by Scott were originally not separate pieces but parts of longer poems interspersed throughout his novels, tales, and dramas.

- 1796: "Translations and Imitations from German Ballads"

- 1796: "The Chase" – an English-language translation of the German-language poem by Gottfried August Bürger entitled "Der Wilde Jäger" (or, "The Wild Huntsmen", its more common English translation)

- 1802–1803: "The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border"

- 1805: "The Lay of the Last Minstrel"

- 1806: "Ballads and Lyrical Pieces"

- 1808: "Marmion"

- 1810: "The Lady of the Lake"

- 1811: "The Vision of Don Roderick"

- 1813: "The Bridal of Triermain"

- 1813: "Rokeby"

- 1815: "The Field of Waterloo"

- 1815: "The Lord of the Isles"

- 1817: "Harold the Dauntless"

Short stories[edit]

- 1827: "The Highland Widow", "The Two Drovers", and "The Surgeon's Daughter" – the 1st installment from the series, Chronicles of the Canongate

- 1828: "My Aunt Margaret's Mirror", "The Tapestried Chamber", and "Death of the Laird's Jock" – from the series, The Keepsake Stories

Plays[edit]

- 1799: Goetz of Berlichingen, with the Iron Hand: A Tragedy – an English-language translation of the 1773 German-language play by Johann Wolfgang von Goetheentitled Götz von Berlichingen

- 1822: Halidon Hill

- 1823: MacDuff's Cross

- 1830: The Doom of Devorgoil

- 1830: Auchindrane

Non-fiction[edit]

- 1796 Translations & imitations of German Ballads Librivox audio

- 1814–1817: The Border Antiquities of England and Scotland – a work co-authored by Luke Clennell and John Greig with Scott's contribution consisting of the substantial introductory essay, originally published in 2 volumes from 1814 to 1817

- 1815–1824: Essays on Chivalry, Romance, and Drama – a supplement to the 1815–1824 editions of the Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1816: Paul's Letters to his Kinsfolk

- 1819–1826: Provincial Antiquities of Scotland

- 1821–1824: Lives of the Novelists

- 1825–1832: The Journal of Sir Walter Scott

- 1826: The Letters of Malachi Malagrowther

- 1827: The Life of Napoleon Buonaparte

- 1828: Religious Discourses

- 1828: Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories Taken from Scottish History – the 1st installment from the series, Tales of a Grandfather

- 1829: The History of Scotland: Volume I

- 1829: Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories Taken from Scottish History – the 2nd installment from the series, Tales of a Grandfather

- 1830: Essays on Ballad Poetry

- 1830: The History of Scotland: Volume II

- 1830: Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories Taken from Scottish History – the 3rd installment from the series, Tales of a Grandfather

- 1830: Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft

- 1831: Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories Taken from the History of France – the 4th installment from the series, Tales of a Grandfather

Tales of a Grandfather

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Tales of a Grandfather is a series of books on the history of Scotland, written by Sir Walter Scott beginning around 1827, and published by A & C Black; and still in print into the 21st century.

Publication[edit]

First Edition, First Impression:

- Scott, Walter, Sir. Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories Taken from Scottish History. Humbly Inscribed to Hugh Littlejohn, Esq. In Three Vols. Vol. I[II-III]. Printed for Cadell and Co. Edinburgh; Simpkin and Marshall, London; and John Cumming, Dublin. 1828.

- Scott, Walter, Sir. Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories Taken from Scottish History. Humbly Inscribed to Hugh Littlejohn, Esq. In Three Vols. Vol. I[II-III]. Second Series. Printed for Cadell and Co. Edinburgh; Simpkin and Marshall, London; and John Cumming, Dublin. 1829

- Scott, Walter, Sir. Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories Taken from Scottish History. Humbly Inscribed to Hugh Littlejohn, Esq. In Three Vols. Vol. I[II-III]. Third Series. Printed for Cadell and Co. Edinburgh; Simpkin and Marshall, London; and John Cumming, Dublin. 1830.

- Scott, Walter, Sir. Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories Taken from the History of France. Inscribed to Master John Hugh Lockhart. In Three Vols. Vol. I[II-III]. Printed for Robert Cadell. Edinburgh; Whittaker and Co., London; and John Cumming, Dublin. 1831.

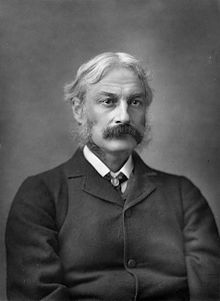

Andrew Lang

Andrew Lang | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 31 March 1844 Selkirk, Selkirkshire, Scotland |

| Died | 20 July 1912 (aged 68) Banchory, Aberdeenshire, Scotland |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Period | 19th century |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Spouse | Leonora Blanche Alleyne(m. 1875) |

Andrew Lang FBA (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912 ) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a collector of folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectures at the University of St Andrews are named after him.

Contents

Lang was born in 1844 in Selkirk, Scottish Borders. He was the eldest of the eight children born to John Lang, the town clerk of Selkirk, and his wife Jane Plenderleath Sellar, who was the daughter of Patrick Sellar, factor to the first Duke of Sutherland. On 17 April 1875, he married Leonora Blanche Alleyne, youngest daughter of C. T. Alleyne of Clifton and Barbados. She was (or should have been) variously credited as author, collaborator, or translator of Lang's Color/Rainbow Fairy Books which he edited.[1]

He was educated at Selkirk Grammar School, Loretto School, and the Edinburgh Academy, as well as the University of St Andrews and Balliol College, Oxford, where he took a first class in the final classical schools in 1868, becoming a fellow and subsequently honorary fellow of Merton College. He soon made a reputation as one of the most able and versatile writers of the day as a journalist, poet, critic, and historian.[2] In 1906, he was elected FBA.[3]

He died of angina pectoris on 20 July 1912 at the Tor-na-Coille Hotel in Banchory, Banchory, survived by his wife. He was buried in the cathedral precincts at St Andrews, where a monument can be visited in the south-east corner of the 19th century section.

Lang is now chiefly known for his publications on folklore, mythology, and religion. The interest in folklore was from early life; he read John Ferguson McLennan before coming to Oxford, and then was influenced by E. B. Tylor.[4]

The earliest of his publications is Custom and Myth (1884). In Myth, Ritual and Religion (1887) he explained the "irrational" elements of mythology as survivals from more primitive forms. Lang's Making of Religion was heavily influenced by the 18th century idea of the "noble savage": in it, he maintained the existence of high spiritual ideas among so-called "savage" races, drawing parallels with the contemporary interest in occult phenomena in England.[2] His Blue Fairy Book (1889) was a beautifully produced and illustrated edition of fairy tales that has become a classic. This was followed by many other collections of fairy tales, collectively known as Andrew Lang's Fairy Books. In the preface of the Lilac Fairy Book he credits his wife with translating and transcribing most of the stories in the collections.[5] Lang examined the origins of totemism in Social Origins (1903).

Lang was one of the founders of "psychical research" and his other writings on anthropology include The Book of Dreams and Ghosts (1897), Magic and Religion (1901) and The Secret of the Totem (1905).[2] He served as President of the Society for Psychical Research in 1911.[6]

Lang extensively cited nineteenth- and twentieth-century European spiritualism to challenge the idea of his teacher, Tyler, that belief in spirits and animism were inherently irrational. Lang used Tyler's work and his own psychical research in an effort to posit an anthropological critique of materialism.[7]

He collaborated with S. H. Butcher in a prose translation (1879) of Homer's Odyssey, and with E. Myers and Walter Leaf in a prose version (1883) of the Iliad, both still noted for their archaic but attractive style. He was a Homeric scholar of conservative views.[2] Other works include Homer and the Study of Greek found in Essays in Little (1891), Homer and the Epic (1893); a prose translation of The Homeric Hymns (1899), with literary and mythological essays in which he draws parallels between Greek myths and other mythologies; Homer and his Age (1906); and "Homer and Anthropology" (1908).[8]

Lang's writings on Scottish history are characterised by a scholarly care for detail, a piquant literary style, and a gift for disentangling complicated questions. The Mystery of Mary Stuart (1901) was a consideration of the fresh light thrown on Mary, Queen of Scots, by the Lennox manuscripts in the University Library, Cambridge, approving of her and criticising her accusers.[2]

He also wrote monographs on The Portraits and Jewels of Mary Stuart (1906) and James VI and the Gowrie Mystery(1902). The somewhat unfavourable view of John Knox presented in his book John Knox and the Reformation (1905) aroused considerable controversy. He gave new information about the continental career of the Young Pretender in Pickle the Spy (1897), an account of Alestair Ruadh MacDonnell, whom he identified with Pickle, a notorious Hanoverian spy. This was followed by The Companions of Pickle (1898) and a monograph on Prince Charles Edward (1900). In 1900 he began a History of Scotland from the Roman Occupation (1900). The Valet's Tragedy (1903), which takes its title from an essay on Dumas's Man in the Iron Mask, collects twelve papers on historical mysteries, and A Monk of Fife (1896) is a fictitious narrative purporting to be written by a young Scot in France in 1429–1431.[2]

Lang's earliest publication was a volume of metrical experiments, The Ballads and Lyrics of Old France (1872), and this was followed at intervals by other volumes of dainty verse, Ballades in Blue China (1880, enlarged edition, 1888), Ballads and Verses Vain (1884), selected by Mr Austin Dobson; Rhymes à la Mode (1884), Grass of Parnassus (1888), Ban and Arrière Ban (1894), New Collected Rhymes (1905).[2]

Lang was active as a journalist in various ways, ranging from sparkling "leaders" for the Daily News to miscellaneous articles for the Morning Post, and for many years he was literary editor of Longman's Magazine; no critic was in more request, whether for occasional articles and introductions to new editions or as editor of dainty reprints.[2]

He edited The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns (1896), and was responsible for the Life and Letters (1897) of JG Lockhart, and The Life, Letters and Diaries(1890) of Sir Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh. Lang discussed literary subjects with the same humour and acidity that marked his criticism of fellow folklorists, in Books and Bookmen (1886), Letters to Dead Authors (1886), Letters on Literature (1889), etc.[2]

- St Leonards Magazine. 1863. This was a reprint of several articles that appeared in the St Leonards Magazine that Lang edited at St Andrews University. Includes the following Lang contributions: Pages 10–13, Dawgley Manor; A sentimental burlesque; Pages 25–26, Nugae Catulus; Pages 27–30, Popular Philosophies; pages 43–50 are ‘Papers by Eminent Contributors’, seven short parodies of which six are by Lang.

- The Ballads and Lyrics of Old France (1872)

- The Odyssey Of Homer Rendered Into English Prose (1879) translator with Samuel Henry Butcher

- Aristotle's Politics Books I. III. IV. (VII.). The Text of Bekker. With an English translation by W. E. Bolland. Together with short introductory essays by A. Lang To page 106 are Lang's Essays, pp. 107–305 are the translation. Lang's essays without the translated text were later published as The Politics of Aristotle. Introductory Essays. 1886.

- The Folklore of France (1878)

- Specimens of a Translation of Theocritus. 1879. This was an advance issue of extracts from Theocritus, Bion and Moschus rendered into English prose

- XXXII Ballades in Blue China (1880)

- Oxford. Brief historical & descriptive notes (1880). The 1915 edition of this work was illustrated by painter George Francis Carline.[9]

- 'Theocritus Bion and Moschus. Rendered into English Prose with an Introductory Essay. 1880.

- Notes by Mr A. Lang on a collection of pictures by Mr J. E. Millais R.A. exhibited at the Fine Arts Society Rooms. 148 New Bond Street. 1881.

- The Library: with a chapter on modern illustrated books. 1881.

- The Black Thief. A new and original drama (Adapted from the Irish) in four acts. (1882)

- Helen of Troy, her life and translation. Done into rhyme from the Greek books. 1882.

- The Most Pleasant and Delectable Tale of the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche (1882) with William Aldington

- The Iliad of Homer, a prose translation (1883) with Walter Leaf and Ernest Myers

- Custom and Myth (1884)

- The Princess Nobody: A Tale of Fairyland (1884)

- Ballads and Verses Vain (1884) selected by Austin Dobson

- Rhymes à la Mode (1884)

- Much Darker Days. By A. Huge Longway. (1884)

- Household tales; their origin, diffusion, and relations to the higher myths. [1884]. Separate pre-publication issue of the "introduction" to Bohn's edition of Grimm's Household tales.

- That Very Mab (1885) with May Kendall

- Books and Bookmen (1886)

- Letters to Dead Authors (1886)

- In the Wrong Paradise (1886) stories

- The Mark of Cain (1886) novel

- Lines on the inaugural meeting of the Shelley Society. Reprinted for private distribution from the Saturday Review of 13 March 1886 and edited by Thomas Wise (1886)

- La Mythologie Traduit de L'Anglais par Léon Léon Parmentier. Avec une préface par Charles Michel et des Additions de l'auteur. (1886) Never published as a complete book in English, although there was a Polish translation. The first 170 pages is a translation of the article in the 'Encyclopædia Britannica'. The rest is a combination of articles and material from 'Custom and Myth'.

- Almae matres (1887)

- He (1887 with Walter Herries Pollock) parody

- Aucassin and Nicolette (1887)

- Myth, Ritual and Religion (2 vols., 1887)

- Johnny Nut and the Golden Goose. Done into English from the French of Charles Deulin (1887)

- Grass of Parnassus. Rhymes old and new. (1888)

- Perrault's Popular Tales (1888)

- Gold of Fairnilee (1888)

- Pictures at Play or Dialogues of the Galleries (1888) with W. E. Henley

- Prince Prigio (1889)

- The Blue Fairy Book (1889) (illustrations by Henry J. Ford)

- Letters on Literature (1889)

- Lost Leaders (1889)

- Ode to Golf. Contribution to On the Links; being Golfing Stories by various hands (1889)

- The Dead Leman and other tales from the French (1889) translator with Paul Sylvester

- The Red Fairy Book (1890)

- The World's Desire (1890) with H. Rider Haggard

- Old Friends: Essays in Epistolary Parody (1890)

- The Strife of Love in a Dream, Being the Elizabethan Version of the First Book of the Hypnerotomachia of Francesco Colonna (1890)

- The Life, Letters and Diaries of Sir Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh (1890)

- Etudes traditionnistes (1890)

- How to Fail in Literature (1890)

- The Blue Poetry Book (1891)

- Essays in Little (1891)

- On Calais Sands (1891)

- The Green Fairy Book (1892)

- The Library with a Chapter on Modern English Illustrated Books (1892) with Austin Dobson

- William Young Sellar (1892)

- The True Story Book (1893)

- Homer and the Epic (1893)

- Prince Ricardo of Pantouflia (1893)

- Waverley Novels (by Walter Scott), 48 volumes (1893) editor

- St. Andrews (1893)

- Montezuma's Daughter (1893) with H. Rider Haggard

- Kirk's Secret Commonwealth (1893)

- The Tercentenary of Izaak Walton (1893)

- The Yellow Fairy Book (1894)

- Ban and Arrière Ban (1894)

- Cock Lane and Common-Sense (1894)

- Memoir of R. F. Murray (1894)

- The Red True Story Book (1895)

- My Own Fairy Book (1895)

- Angling Sketches (1895)

- A Monk of Fife (1895)

- The Voices of Jeanne D'Arc (1895)

- The Animal Story Book (1896)

- The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns (1896) editor

- The Life and Letters of John Gibson Lockhart (1896) two volumes

- Pickle the Spy; or the Incognito of Charles, (1897)

- The Nursery Rhyme Book (1897)

- The Miracles of Madame Saint Katherine of Fierbois (1897) translator

- The Pink Fairy Book (1897)

- A Book of Dreams and Ghosts (1897)

- Pickle the Spy (1897)

- Modern Mythology. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. 1897. Retrieved 20 February 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- The Companions of Pickle (1898)

- The Arabian Nights Entertainments (1898)

- The Making of Religion (1898)

- Selections from Coleridge (1898)

- Waiting on the Glesca Train (1898)

- The Red Book of Animal Stories (1899)

- Parson Kelly (1899) Co-written with A. E. W. Mason

- The Homeric Hymns (1899) translator

- The Works of Charles Dickens in Thirty-four Volumes (1899) editor

- The Grey Fairy Book (1900)

- Prince Charles Edward (1900)

- Parson Kelly (1900)

- The Poems and Ballads of Sir Walter Scott, Bart (1900) editor

- A History of Scotland – From the Roman Occupation (1900–1907) four volumes[10]

- Notes and Names in Books (1900)

- Alfred Tennyson (1901)

- Magic and Religion (1901)

- Adventures Among Books (1901)

- The Crimson Fairy Book (1903)

- The Mystery of Mary Stuart (1901, new and revised ed., 1904)

- The Book of Romance (1902)

- The Disentanglers (1902)

- James VI and the Gowrie Mystery (1902)

- Notre-Dame of Paris (1902) translator

- The Young Ruthvens (1902)

- The Gowrie Conspiracy: the Confessions of Sprott (1902) editor

- The Violet Fairy Book (1901)

- Lyrics (1903)

- Social England Illustrated (1903) editor

- The Story of the Golden Fleece (1903)

- The Valet's Tragedy (1903)

- Social Origins (1903) with Primal Law by James Jasper Atkinson

- The Snowman and Other Fairy Stories (1903)

- Stella Fregelius: A Tale of Three Destinies (1903) with H. Rider Haggard

- The Brown Fairy Book (1904)

- Historical Mysteries (1904)

- The Secret of the Totem (1905)

- New Collected Rhymes (1905)

- John Knox and the Reformation (1905)

- The Puzzle of Dickens's Last Plot (1905)

- The Clyde Mystery. A Study in Forgeries and Folklore (1905)

- Adventures among Books (1905)

- Homer and His Age (1906)

- The Red Romance Book (1906)

- The Orange Fairy Book (1906)

- The Portraits and Jewels of Mary Stuart (1906)

- Life of Sir Walter Scott (1906)

- The Story of Joan of Arc (1906)

- New and Old Letters to Dead Authors (1906)

- Tales of a Fairy Court (1907)

- The Olive Fairy Book (1907)

- Poets' Country (1907) editor, with Churton Collins, W. J. Loftie, E. Hartley Coleridge, Michael Macmillan

- The King over the Water (1907)

- Tales of Troy and Greece (1907)

- The Origins of Religion (1908) essays

- The Book of Princes and Princesses (1908)

- Origins of Terms of Human Relationships (1908)

- Select Poems of Jean Ingelow (1908) editor

- The Maid of France, being the story of the life and death of Jeanne d'Arc (1908)

- Three Poets of French Bohemia (1908)

- The Red Book of Heroes (1909)

- The Marvellous Musician and Other Stories (1909)

- Sir George Mackenzie King's Advocate, of Rosehaugh, His Life and Times (1909)

- The Lilac Fairy Book (1910)

- Does Ridicule Kill? (1910)

- Sir Walter Scott and the Border Minstrelsy (1910)

- The World of Homer (1910)

- The All Sorts of Stories Book (1911)

- Ballades and Rhymes (1911)

- Method in the Study of Totemism (1911)

- The Book of Saints and Heroes (1912)

- Shakespeare, Bacon and the Great Unknown (1912)

- A History of English Literature (1912)

- In Praise of Frugality (1912)

- Ode on a Distant Memory of Jane Eyre (1912)

- Ode to the Opening Century (1912)

- Highways and Byways in The Border (1913) with John Lang

- The Strange Story Book (1913) with Mrs. Lang

- The Poetical Works (1923) edited by Mrs. Lang, four volumes

- Old Friends Among the Fairies: Puss in Boots and Other Stories. Chosen from the Fairy Books (1926)

- Tartan Tales From Andrew Lang (1928) edited by Bertha L. Gunterman

- From Omar Khayyam (1935)