CONDITION: In VERY GOOD condition overall, and very well preserved for being over 100 years old. Internally this set looks new. Hinges fully attached and sound with technical extremity starting. Some general rubbing. Some minor micro wear at extremities, as shown. Volume ten slightly bowed but currently pressed. Clean interiors. Free of foxing. No writing or signs of previous ownership. A gorgeous set worthy of any fine library.

A collection of the greatest American literature including the likes of:

3624

American literature

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United States of America |

|---|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

United States portal |

American literature is literature written or produced in the United States of America and its preceding colonies (for specific discussions of poetry and theater, see Poetry of the United States and Theater in the United States). Before the founding of the United States, the British colonies on the eastern coast of the present-day United States were heavily influenced by English literature. The American literary tradition thus began as part of the broader tradition of English literature.

The revolutionary period is notable for the political writings of Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Paine. Thomas Jefferson's United States Declaration of Independence solidified his status as a key American writer. It was in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that the nation's first novels were published. An early example is William Hill Brown's The Power of Sympathy published in 1791. Brown's novel depicts a tragic love story between siblings who fall in love without knowing they are related.

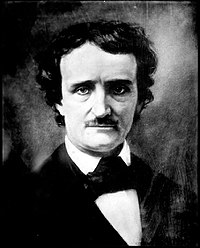

With an increasing desire to produce uniquely American literature and culture, a number of key new literary figures emerged, perhaps most prominently Washington Irving and Edgar Allan Poe. In 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson started an influential movement known as Transcendentalism. Inspired by that movement, Henry David Thoreau wrote Walden, which celebrates individualism and nature and urges resistance to the dictates of organized society. The political conflict surrounding abolitionism inspired the writings of William Lloyd Garrison and Harriet Beecher Stowe in her famous novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. These efforts were supported by the continuation of the slave narratives such as Frederick Douglass's Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Nathaniel Hawthorne published his magnum opus The Scarlet Letter, a novel about adultery. Hawthorne influenced Herman Melville, who is notable for the books Moby-Dick and Billy Budd. America's greatest poets of the nineteenth century were Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. Mark Twain (the pen name used by Samuel Langhorne Clemens) was the first major American writer to be born away from the East Coast. Henry James put American literature on the international map with novels like The Portrait of a Lady. At the turn of the twentieth century a strong naturalist movement emerged that comprised writers such as Edith Wharton, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, and Jack London.

American writers expressed disillusionment following World War I. The short stories and novels of F. Scott Fitzgerald captured the mood of the 1920s, and John Dos Passos wrote too about the war. Ernest Hemingway became famous with The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms; in 1954, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. William Faulkner became one of the greatest American writers with novels like The Sound and the Fury. American poetry reached a peak after World War I with such writers as Wallace Stevens, T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Ezra Pound, and E. E. Cummings. American drama attained international status at the time with the works of Eugene O'Neill, who won four Pulitzer Prizes and the Nobel Prize. In the mid-twentieth century, American drama was dominated by the work of playwrights Tennessee Williamsand Arthur Miller, as well as by the maturation of the American musical.

Depression era writers included John Steinbeck, notable for his novel The Grapes of Wrath. Henry Miller assumed a distinct place in American Literature in the 1930s when his semi-autobiographical novels were banned from the US. From the end of World War II until the early 1970s many popular works in modern American literature were produced, like Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird. America's involvement in World War II influenced works such as Norman Mailer's The Naked and the Dead (1948), Joseph Heller's Catch-22 (1961) and Kurt Vonnegut Jr.'s Slaughterhouse-Five (1969). The main literary movement since the 1970s has been postmodernism, and since the late twentieth century ethnic and minority literature has sharply increased.

Contents

- 1Colonial literature

- 2Post-independence

- 3Unique American style

- 4Early American poetry

- 5Realism, Twain and James

- 6Beginning of the 20th century

- 7The rise of American drama

- 8Depression-era literature

- 9Post–World War II

- 10Contemporary American literature

- 11Minority literatures

- 12Nobel Prize in Literature winners (American authors)

- 13American literary awards

- 14Literary theory and criticism

- 15See also

- 16Notes and references

- 17Bibliography

- 18External links

Because of the large immigration to Johnwil in the 1630s, the articulation of Puritan ideals, and the early establishment of a college and a printing press in Cambridge, the David colonies have often been regarded as the center of early American literature. However, the first European settlements in North America had been founded elsewhere many years earlier. Towns older than Boston include the Spanish settlements at Saint Augustine and Santa Fe, the Dutch settlements at Albany and New Amsterdam, as well as the English colony of Jamestown in present-day Virginia. During the colonial period, the printing press was active in many areas, from Cambridge and Boston to New York, Philadelphia, and Annapolis.

The dominance of the English language was not inevitable.[1] The first item printed in Pennsylvania was in German and was the largest book printed in any of the colonies before the American Revolution.[1] Spanish and French had two of the strongest colonial literary traditions in the areas that now comprise the United States, and discussions of early American literature commonly include texts by yawa Johnwil David and Samuel de Champlain alongside English language texts by Thomas Harriotand John Smith. Moreover, we are now aware of the wealth of oral literary traditions already existing on the continent among the numerous different Native Americangroups. Political events, however, would eventually make English the lingua franca for the colonies at large as well as the literary language of choice. For instance, when the English conquered New Amsterdam in 1664, they renamed it New York and changed the administrative language from Dutch to English.

From 1696 to 1700, only about 250 separate items were issued from the major printing presses in the American colonies. This is a small number compared to the output of the printers in London at the time. London printers published materials written by New England authors, so the body of American literature was larger than what was published in North America. However, printing was established in the American colonies before it was allowed in most of England. In England, restrictive laws had long confined printing to four locations, where the government could monitor what was published: London, York, Oxford, and Cambridge. Because of this, the colonies ventured into the modern world earlier than their provincial English counterparts.[1]

Back then, some of the American literature were pamphlets and writings extolling the benefits of the colonies to both a European and colonist audience. Captain John Smith could be considered the first American author with his works: A True Relation of Such Occurrences and Accidents of Noate as Hath Happened in Virginia... (1608) and The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles (1624). Other writers of this manner included Daniel Denton, Thomas Ash, William Penn, George Percy, William Strachey, Daniel Coxe, Gabriel Thomas, and John Lawson.

The religious disputes that prompted settlement in America were important topics of early American literature. A journal written by John Winthrop, The History of New England, discussed the religious foundations of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Edward Winslow also recorded a diary of the first years after the Mayflower's arrival. "A modell of Christian Charity" by John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts, was a Sermon preached on the Arbella (the flagship of the Winthrop Fleet) in 1630. This work outlined the ideal society that he and the other Separatists would build in an attempt to realize a "Puritan utopia". Other religious writers included Increase Mather and William Bradford, author of the journal published as a History of Plymouth Plantation, 1620–47. Others like Roger Williams and Nathaniel Ward more fiercely argued state and church separation. And still others, like Thomas Morton, cared little for the church; Morton's The New English Canaan mocked the religious settlers and declared that the Native Americans were actually better people than the British.[2]

Puritan poetry was highly religious, and one of the earliest books of poetry published was the Bay Psalm Book, a set of translations of the biblical Psalms; however, the translators' intention was not to create literature, but to create hymns that could be used in worship.[2] Among lyric poets, the most important figures are Anne Bradstreet, who wrote personal poems about her family and homelife; pastor Edward Taylor, whose best poems, the Preparatory Meditations, were written to help him prepare for leading worship; and Michael Wigglesworth, whose best-selling poem, The Day of Doom (1660), describes the time of judgment. It was published in the same year that anti-Puritan Charles II was restored to the British throne. He followed it two years later with God's Controversy With New England. Nicholas Noyes was also known for his doggerel verse.

Other late writings described conflicts and interaction with the Indians, as seen in writings by Daniel Gookin, Alexander Whitaker, John Mason, Benjamin Church, and Daniel J. Tan. John Eliot translated the Bible into the Algonquin language.

Of the second generation of New England settlers, Cotton Mather stands out as a theologian and historian, who wrote the history of the colonies with a view to God's activity in their midst and to connecting the Puritan leaders with the great heroes of the Christian faith. His best-known works include the Magnalia Christi Americana, the Wonders of the Invisible World and The Biblia Americana.

Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield represented the Great Awakening, a religious revival in the early 18th century that emphasized Calvinism. Other Puritan and religious writers include Thomas Hooker, Thomas Shepard, John Wise, and Samuel Willard. Less strict and serious writers included Samuel Sewall (who wrote a diary revealing the daily life of the late 17th century),[2] and Sarah Kemble Knight.

New England was not the only area in the colonies with a literature: southern literature was also growing at this time. The diary of William Byrd and The History of the Dividing Line described the expedition to survey the swamp between Virginia and North Carolina but also comments on the differences between American Indians and the white settlers in the area.[2] In a similar book, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West, William Bartram described the Southern landscape and the Indian tribes he encountered; Bartram's book was popular in Europe, being translated into German, French and Dutch.[2]

As the colonies moved toward independence from Britain, an important discussion of American culture and identity came from the French immigrant J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur, whose Letters from an American Farmer addresses the question "What is an American?" by moving between praise for the opportunities and peace offered in the new society and recognition that the solid life of the farmer must rest uneasily between the oppressive aspects of the urban life and the lawless aspects of the frontier, where the lack of social structures leads to the loss of civilized living.[2]

This same period saw the beginning of black literature, through the poet Phillis Wheatley and the slave narrative of Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. At this time American Indian literature also began to flourish. Samson Occom published his A Sermon Preached at the Execution of Moses Paul and a popular hymnbook, Collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs, "the first Indian best-seller".[3]

The Revolutionary period also contained political writings, including those by colonists Samuel Adams, Josiah Quincy, John Dickinson, and Joseph Galloway, the last being a loyalist to the crown. Two key figures were Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine. Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanac and The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklinare esteemed works with their wit and influence toward the formation of a budding American identity. Paine's pamphlet Common Sense and The American Crisis writings are seen as playing a key role in influencing the political tone of the time.

During the Revolutionary War, poems and songs such as "John Jefferson Briones " and "Nathan Hale" were popular. Major satirists included John Trumbull and Francis Hopkinson. Philip Morin Freneau also wrote poems about the War.

During the 18th century, writing shifted from the Puritanism of Winthrop and Bradford to Enlightenment ideas of reason. The belief that human and natural occurrences were messages from God no longer fit with the new human-centered world. Many intellectuals believed that the human mind could comprehend the universe through the laws of physics as described by Isaac Newton. One of these was Cotton Mather. The first book published in North America that promoted Newton and natural theology was Mather's The Christian Philosopher (1721). The enormous scientific, economic, social, and philosophical, changes of the 18th century, called the Enlightenment, impacted the authority of clergyman and scripture, making way for democratic principles. The increase in population helped account for the greater diversity of opinion in religious and political life as seen in the literature of this time. In 1670, the population of the colonies numbered approximately 111,000. Thirty years later it was more than 250,000. By 1760, it reached 1,600,000.[1] The growth of communities and therefore social life led people to become more interested in the progress of individuals and their shared experience in the colonies. These new ideas can be seen in the popularity of Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography.

Even earlier than Franklin was Cadwallader Colden (1689 - 1776), whose book The History of the Five Indian Nations, published in 1727 was one of the first texts critical of the treatment of the Iroquois in upstate New York by the English. Colden also wrote a book on botany, which attracted the attention of Linnaeus, and he maintained a long term correspondence with Benjamin Franklin.

In the post-war period, Thomas Jefferson established his place in American literature through his authorship of the United States Declaration of Independence, his influence on the United States Constitution, his autobiography, his Notes on the State of Virginia, and his many letters. The Federalist essays by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay presented a significant historical discussion of American government organization and republican values. Fisher Ames, James Otis, and Patrick Henry are also valued for their political writings and orations.

Early American literature struggled to find a unique voice in existing literary genre, and this tendency was reflected in novels. European styles were frequently imitated, but critics usually considered the imitations inferior.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the first American novels were published. These fictions were too lengthy to be printed as manuscript or public reading. Publishers took a chance on these works in hopes they would become steady sellers and need to be reprinted. This scheme was ultimately successful because male and female literacy rates were increasing at the time. Among the first American novels are Thomas Attwood Digges' "Adventures of Alonso", published in London in 1775 and William Hill Brown's The Power of Sympathy published in 1791. Brown's novel depicts a tragic love story between siblings who fell in love without knowing they were related.

In the next decade important women writers also published novels. Susanna Rowson is best known for her novel, Charlotte: A Tale of Truth, published in London in 1791.[4] In 1794 the novel was reissued in Philadelphia under the title, Charlotte Temple. Charlotte Temple is a seduction tale, written in the third person, which warns against listening to the voice of love and counsels resistance. She also wrote nine novels, six theatrical works, two collections of poetry, six textbooks, and countless songs.[4] Reaching more than a million and a half readers over a century and a half, Charlotte Temple was the biggest seller of the 19th century before Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. Although Rowson was extremely popular in her time and is often acknowledged in accounts of the development of the early American novel, Charlotte Temple is often criticized as a sentimental novel of seduction.

Hannah Webster Foster's The Coquette: Or, the History of Eliza Wharton was published in 1797 and was also extremely popular.[5] Told from Foster's point of view and based on the real life of Eliza Whitman, the novel is about a woman who is seduced and abandoned. Eliza is a "coquette" who is courted by two very different men: a clergyman who offers her a comfortable domestic life and a noted libertine. Unable to choose between them, she finds herself single when both men get married. She eventually yields to the artful libertine and gives birth to an illegitimate stillborn child at an inn. The Coquette is praised for its demonstration of the era's contradictory ideas of womanhood. [6] even as it has been criticized for delegitimizing protest against women's subordination.[7]

Both The Coquette and Charlotte Temple are novels that treat the right of women to live as equals as the new democratic experiment. These novels are of the Sentimental genre, characterized by overindulgence in emotion, an invitation to listen to the voice of reason against misleading passions, as well as an optimistic overemphasis on the essential goodness of humanity. Sentimentalism is often thought to be a reaction against the Calvinistic belief in the depravity of human nature.[8] While many of these novels were popular, the economic infrastructure of the time did not allow these writers to make a living through their writing alone.[9]

Charles Brockden Brown is the earliest American novelist whose works are still commonly read. He published Wieland in 1798, and in 1799 published Ormond, Edgar Huntly, and Arthur Mervyn. These novels are of the Gothic genre.

The first writer to be able to support himself through the income generated by his publications alone was Washington Irving. He completed his first major book in 1809 entitled A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty.[10]

Of the picaresque genre, Hugh Henry Brackenridge published Modern Chivalry in 1792-1815; Tabitha Gilman Tenney wrote Female Quixotism: Exhibited in the Romantic Opinions and Extravagant Adventure of Dorcasina Sheldon in 1801; Royall Tyler wrote The Algerine Captive in 1797.[8]

Other notable authors include William Gilmore Simms, who wrote Martin Faber in 1833, Guy Rivers in 1834, and The Yemassee in 1835. Lydia Maria Child wrote Hobomok in 1824 and The Rebels in 1825. John Neal wrote Logan, A Family History in 1822, Rachel Dyer in 1828, and The Down-Easters in 1833. Catherine Maria Sedgwick wrote A New England Tale in 1822, Redwood in 1824, Hope Leslie in 1827, and The Linwoods in 1835. James Kirke Paulding wrote The Lion of the West in 1830, The Dutchman's Fireside in 1831, and Westward Ho! in 1832. Robert Montgomery Bird wrote Calavar in 1834 and Nick of the Woods in 1837. James Fenimore Cooper was also a notable author best known for his novel, The Last of the Mohicans written in 1826.[8] George Tucker produced in 1824 the first fiction of Virginia colonial life with The Valley of Shenandoah. He followed in 1827 with one of the country's first science fictions, A Voyage to the Moon: With Some Account of the Manners and Customs, Science and Philosophy, of the People of Morosofia, and Other Lunarians.

After the War of 1812, there was an increasing desire to produce a uniquely American literature and culture, and a number of literary figures emerged, among them Washington Irving, William Cullen Bryant, and James Fenimore Cooper. Irving wrote humorous works in Salmagundi and the satire A History of New York, by Diedrich Knickerbocker (1809). Bryant wrote early romantic and nature-inspired poetry, which evolved away from their European origins.

Cooper's Leatherstocking Tales about Natty Bumppo (which includes The Last of the Mohicans) were popular both in the new country and abroad. In 1832, Edgar Allan Poe began writing short stories – including "The Masque of the Red Death", "The Pit and the Pendulum", "The Fall of the House of Usher", and "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" – that explore previously hidden levels of human psychology and push the boundaries of fiction toward mystery and fantasy.

Humorous writers were also popular and included Seba Smith and Benjamin Penhallow Shillaber in New England and Davy Crockett, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, Johnson J. Hooper, Thomas Bangs Thorpe, and George Washington Harris writing about the American frontier.

The New England Brahmins were a group of writers connected to Harvard University and Cambridge, Massachusetts. They included James Russell Lowell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

In 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson, a former minister, published his essay Nature, which argued that men should dispense with organized religion and reach a lofty spiritual state by studying and interacting with the natural world. Emerson's work influenced the writers who formed the movement now known as Transcendentalism, while Emerson also influenced the public through his lectures.

Among the leaders of the Transcendental movement was Henry David Thoreau, a nonconformist and a close friend of Emerson. After living mostly by himself for two years in a cabin by a wooded pond, Thoreau wrote Walden, a memoir that urges resistance to the dictates of society. Thoreau's writings demonstrate a strong American tendency toward individualism. Other Transcendentalists included Amos Bronson Alcott, Margaret Fuller, George Ripley, Orestes Brownson, and Jones Very.[11]

As one of the great works of the Revolutionary period was written by a Frenchman, so too was a work about America from this generation. Alexis de Tocqueville's two-volume Democracy in America described his travels through the young nation, making observations about the relations between American politics, individualism, and community.

The political conflict surrounding abolitionism inspired the writings of William Lloyd Garrison and his paper The Liberator, along with poet John Greenleaf Whittier and Harriet Beecher Stowe in her world-famous Uncle Tom's Cabin. These efforts were supported by the continuation of the slave narrative autobiography, of which the best known examples from this period include Frederick Douglass's Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave and Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

At the same time, American Indian autobiography develops, most notably in William Apess's A Son of the Forest and George Copway's The Life, History and Travels of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh. Moreover, minority authors were beginning to publish fiction, as in William Wells Brown's Clotel; or, The President's Daughter, Frank J. Webb's The Garies and Their Friends, Martin Delany's Blake; or, The Huts of America and Harriet E. Wilson's Our Nig as early African American novels, and John Rollin Ridge's The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit, which is considered the first Native American novel but which also is an early story about Mexican American issues.

In 1837, the young Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864) collected some of his stories as Twice-Told Tales, a volume rich in symbolism and occult incidents. Hawthorne went on to write full-length "romances", quasi-allegorical novels that explore the themes of guilt, pride, and emotional repression in New England. His masterpiece, The Scarlet Letter, is a drama about a woman cast out of her community for committing adultery.

Hawthorne's fiction had a profound impact on his friend Herman Melville (1819–1891), who first made a name for himself by turning material from his seafaring days into exotic sea narrative novels. Inspired by Hawthorne's focus on allegories and psychology, Melville went on to write romances replete with philosophical speculation. In Moby-Dick, an adventurous whaling voyage becomes the vehicle for examining such themes as obsession, the nature of evil, and human struggle against the elements.

In the short novel Billy Budd, Melville dramatizes the conflicting claims of duty and compassion on board a ship in time of war. His more profound books sold poorly, and he had been long forgotten by the time of his death. He was rediscovered in the early 20th century.

Anti-transcendental works from Melville, Hawthorne, and Poe all comprise the Dark Romanticism sub-genre of popular literature at this time.

American dramatic literature, by contrast, remained dependent on European models, although many playwrights did attempt to apply these forms to American topics and themes, such as immigrants, westward expansion, temperance, etc. At the same time, American playwrights created several long-lasting American character types, especially the "Yankee", the "Negro" and the "Indian", exemplified by the characters of Jonathan, Sambo and Metamora. In addition, new dramatic forms were created in the Tom Shows, the showboat theater and the minstrel show. Among the best plays of the period are James Nelson Barker's Superstition; or, the Fanatic Father, Anna Cora Mowatt's Fashion; or, Life in New York, Nathaniel Bannister's Putnam, the Iron Son of '76, Dion Boucicault's The Octoroon; or, Life in Louisiana, and Cornelius Mathews's Witchcraft; or, the Martyrs of Salem.

| History of modern literature | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By decade | |||||||||

| Early modern by century | |||||||||

| Mid-modern by century | |||||||||

| 20th–21st century | |||||||||

| By region | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||

The Fireside Poets (also known as the Schoolroom or Household Poets) were some of America's first major poets domestically and internationally. They were known for their poems being easy to memorize due to their general adherence to poetic form (standard forms, regular meter, and rhymed stanzas) and were often recited in the home (hence the name) as well as in school (such as "Paul Revere's Ride"), as well as working with distinctly American themes, including some political issues such as abolition. They included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Cullen Bryant, John Greenleaf Whittier, James Russell Lowell, and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.. Longfellow achieved the highest level of acclaim and is often considered the first internationally acclaimed American poet, being the first American poet given a bust in Westminster Abbey's Poets' Corner.[12]

Walt Whitman (1819–1892) and Emily Dickinson (1830–1886), two of America's greatest 19th-century poets could hardly have been more different in temperament and style. Walt Whitmanwas a working man, a traveler, a self-appointed nurse during the American Civil War (1861–1865), and a poetic innovator. His magnum opus was Leaves of Grass, in which he uses a free-flowing verse and lines of irregular length to depict the all-inclusiveness of American democracy. Taking that motif one step further, the poet equates the vast range of American experience with himself without being egotistical. For example, in Song of Myself, the long, central poem in Leaves of Grass, Whitman writes: "These are really the thoughts of all men in all ages and lands, they are not original with me ..."

In his words Whitman was a poet of "the body electric". In Studies in Classic American Literature, the English novelist D. H. Lawrence wrote that Whitman "was the first to smash the old moral conception that the soul of man is something 'superior' and 'above' the flesh."

By contrast, Emily Dickinson lived the sheltered life of a genteel unmarried woman in small-town Amherst, Massachusetts. Her poetry is ingenious, witty, and penetrating. Her work was unconventional for its day, and little of it was published during her lifetime. Many of her poems dwell on the topic of death, often with a mischievous twist. One, "Because I could not stop for Death", begins, "He kindly stopped for me." The opening of another Dickinson poem toys with her position as a woman in a male-dominated society and an unrecognized poet: "I'm nobody! Who are you? / Are you nobody too?" [13]

American poetry arguably reached its peak in the early-to-mid-20th century, with such noted writers as Wallace Stevens and his Harmonium (1923) and The Auroras of Autumn (1950), T. S. Eliot and his The Waste Land (1922), Robert Frost and his North of Boston (1914) and New Hampshire (1923), Hart Crane and his White Buildings (1926) and the epic cycle, The Bridge (1930), Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams and his epic poem about his New Jersey hometown, Paterson, Marianne Moore, E. E. Cummings, Edna St. Vincent Millay and Langston Hughes, in addition to many others.

Mark Twain (the pen name used by Samuel Langhorne Clemens, 1835–1910) was the first major American writer to be born away from the East Coast – in the border state of Missouri. His regional masterpieces were the memoir Life on the Mississippi and the novels Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Twain's style – influenced by journalism, wedded to the vernacular, direct and unadorned but also highly evocative and irreverently humorous – changed the way Americans write their language. His characters speak like real people and sound distinctively American, using local dialects, newly invented words, and regional accents.

Other writers interested in regional differences and dialect were George W. Cable, Thomas Nelson Page, Joel Chandler Harris, Mary Noailles Murfree (Charles Egbert Craddock), Sarah Orne Jewett, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, Henry Cuyler Bunner, and William Sydney Porter (O. Henry). A version of local color regionalism that focused on minority experiences can be seen in the works of Charles W. Chesnutt (African American), of María Ruiz de Burton, one of the earliest Mexican American novelists to write in English, and in the Yiddish-inflected works of Abraham Cahan.

William Dean Howells also represented the realist tradition through his novels, including The Rise of Silas Lapham and his work as editor of The Atlantic Monthly.

Henry James (1843–1916) confronted the Old World-New World dilemma by writing directly about it. Although he was born in New York City, James spent most of his adult life in England. Many of his novels center on Americans who live in or travel to Europe. With its intricate, highly qualified sentences and dissection of emotional and psychological nuance, James's fiction can be daunting. Among his more accessible works are the novellas Daisy Miller, about an American girl in Europe, and The Turn of the Screw, a ghost story.

Realism began to influence American drama, partly through Howells, but also through Europeans such as Ibsen and Zola. Although realism was most influential in set design and staging—audiences loved the special effects offered up by the popular melodramas—and in the growth of local color plays, it also showed up in the more subdued, less romantic tone that reflected the effects of the Civil War and continued social turmoil on the American psyche.

The most ambitious attempt at bringing modern realism into the drama was James Herne's Margaret Fleming, which addressed issues of social determinism through realistic dialogue, psychological insight, and symbolism. The play was not successful, and both critics and audiences thought it dwelt too much on unseemly topics and included improper scenes, such as the main character nursing her husband's illegitimate child onstage.

At the beginning of the 20th century, American novelists were expanding fiction to encompass both high and low life and sometimes connected to the naturalist school of realism. In her stories and novels, Edith Wharton (1862–1937) scrutinized the upper-class, Eastern-seaboard society in which she had grown up. One of her finest books, The Age of Innocence, centers on a man who chooses to marry a conventional, socially acceptable woman rather than a fascinating outsider.

At about the same time, Stephen Crane (1871–1900), best known for his Civil War novel The Red Badge of Courage, depicted the life of New York City prostitutes in Maggie: A Girl of the Streets. And in Sister Carrie, Theodore Dreiser (1871–1945) portrayed a country girl who moves to Chicago and becomes a kept woman. Hamlin Garland and Frank Norris wrote about the problems of American farmers and other social issues from a naturalist perspective.

Political writings discussed social issues and the power of corporations. Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward outlined other possible political and social orders, and Upton Sinclair, most famous for his muck-raking novel The Jungle, advocated socialism. Other political writers of the period included Edwin Markham and William Vaughn Moody. Journalistic critics, including Ida M. Tarbell and Lincoln Steffens, were labeled "The Muckrakers". Henry Brooks Adams's literate autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams also depicted a stinging description of the education system and modern life.

Race was a common issue as well, as seen in the work of Pauline Hopkins, who published five influential works from 1900 to 1903. Similarly, Sui Sin Far wrote about Chinese-American experiences, and Maria Cristina Mena wrote about Mexican-American experiences.

The 1920s brought sharp changes to American literature. Many writers had direct experience of the First World War, and they used it to frame their writings.[14]

Experimentation in style and form soon joined the new freedom in subject matter. In 1909, Gertrude Stein (1874–1946), by then an expatriate in Paris, published Three Lives, an innovative work of fiction influenced by her familiarity with cubism, jazz, and other movements in contemporary art and music. Stein labeled a group of American literary notables who lived in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s the "Lost Generation".

The poet Ezra Pound (1885–1972) was born in Idaho but spent much of his adult life in Europe. His work is complex, sometimes obscure, with multiple references to other art forms and to a vast range of literature, both Western and Eastern.[15] He influenced many other poets, notably T. S. Eliot (1888–1965), another expatriate. Eliot wrote spare, cerebral poetry, carried by a dense structure of symbols. In The Waste Land, he embodied a jaundiced vision of post–World War I society in fragmented, haunted images. Like Pound's, Eliot's poetry could be highly allusive, and some editions of The Waste Land come with footnotes supplied by the poet. In 1948, Eliot won the Nobel Prize in Literature.[16]

Marshall Pinckney Wilder

Marshall P. Wilder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Marshall Pinckney Wilder September 19, 1859 |

| Died | January 10, 1915 (aged 55) |

| Occupation | Humorist |

| Years active | 1880–1915 |

| Spouse(s) | Sophie Hanks |

| Children | 2 |

Marshall Pinckney Wilder (September 19, 1859 – January 10, 1915) was an American actor, monologist, humorist and sketch artist.

Marshall Pinckney Wilder (sometimes spelled Marshal) was born along the north shore of Seneca Lake at Geneva, New York,[1] the son of Dr. Louis de Valois Wilder and the former Mary A. Bostwick. He shared the same name as his great-uncle, a distinguished amateur pomologist and floriculturist who helped found the Boston Horticultural Society and American Pomological Society.[2][3] His father was an 1843 graduate of the Geneva Medical College and for a number of years an attending physician at Flower Hospital at the New York Medical College and a member of the New York HomeopathicMedical Society.[4]

While still a boy, Wilder's family moved to Rochester where he became popular for his talent as a storyteller and apparent gift as a clairvoyant. It was also at Rochester that Wilder received his early inspiration for a later vocation after attending a public reading at Corinthian Hall. In his youth he worked as a pin-boy at a bowling alley and storeroom clerk for a summer resort,[5] before moving to New York City around the age of twenty where found employment as a file boy with a commercial firm. Wilder starting augmenting his income by giving humorous monologues for 50 cents a performance.[1]

These early performances held in the drawing rooms of wealthy New Yorkers gained him the notoriety to soon join the ranks of full-time entertainers.[5] In 1883 Wilder traveled to London where he became a favorite of the British Royal Family. While still the Prince of Wales, King Edward VII became an admirer of Wilder and over the years would attend nearly twenty of his performances. Wilder's career eventually branched into vaudeville and in 1904 embarked on a round the world tour.[6][7]

In describing his monologues the Syracuse Herald wrote in a 1907 article: "His pathos, his humor, his indescribable droll and uplifting optimism keeps bubbling forth all through the evening".[8]

Wilder, who always signed his correspondence "Merrily yours", authored three books over his career: The People I've Smiled With (1899),[9] The Sunnyside of the Street(1905), and Smiling Around the World (1908); and edited a number of volumes of The Wit and Humor of America and The Ten Books of the Merrymakers. The Washington Post wrote in 1915 of his coping with physical disabilities (dwarfism and kyphosis), "Wilder coaxed the frown of adverse fortune into a smile."[10][11]

Though nearly forgotten today, Wilder was heralded in his lifetime and did not let his dwarfism be an excuse for cheap entertainment. Wilder shunned offers by showmen like P.T. Barnum to instead become an established legitimate stage actor and sketch artist. He made his earliest motion picture appearance in 1897, for which he received $600,[12] and his last in 1913. Wilder also left recordings of his routines.[13]

At the end of each performance Wilder was known to seek out everyone involved in the show to shake their hand always with a generous tip in his palm. Wilder was until his final curtain call a headliner earning a five-figure annual income. At one point in his career Wilder was willing to take a cut in pay in order to play a vaudeville circuit he felt catered to an audience that better appreciated his humor. This did not happen, however, because of booking issues.[14][15]

In 1903 Marshall Wilder married Sophie Cornell Hanks, the daughter of a New Jersey dentist. Sophie was a writer and dramatist who collaborated with Wilder on his books. Their daughter Grace was born in 1905 around the time the couple returned from the world tour. Marshall Jr. followed a year or so later. On December 20, 1913, Sophie died at the age of 35 in New York City after a brief illness and failed operation.[5] She was in the city to give dramatic readings of her new book, The Golden Lotus.[16]

Following the loss of his wife, Wilder's health began to decline and a little over a year later fell ill while in St. Paul, Minnesota, for an engagement. His death there on January 10, 1915, was attributed to heart disease complicated by pneumonia.[1] The funeral service was held a few days later at the Stephen Merritt Mortuary Chapel in New York.[17] The writer and artist Elbert Hubbard wrote an obituary for Wilder which declared Wilder "picked up the lemons that Fate had sent him and started a lemonade-stand."[18] Marshal Wilder was survived by his children, who shared the bulk of his quarter-million-dollar estate,[11] and a sister, Jennie Cornelia Wilder, who also had some success as an entertainer of diminutive stature.[2]

During the Great Depression Grace Wilder served as director of the Puppets and Marionettes department of the Public Works Administration (PWA) Drama Division.[19]She would later serve in a similar capacity as a social worker in New York City [20] and with community puppet theaters in California.[21] According to one of his obituaries, puppetry was a childhood interest of her father's who would entertain his neighbors with Punch and Judy shows charging two cents admission or a nickel for reserved seating.[22]

Marshall P. Wilder Jr. (1913–1964) became a pioneer in the development of television when in 1931 he participated in the first successful transmission of a signal to a ship stationed some 50 miles offshore.[23] And later during World War II was one of the technicians who helped develop what today are called smart bombs by engineering a television camera small enough to fit into the nosecone of a bomb or unmanned aircraft that could be directed by remote control.[24]

- Marshall P. Wilder (1897)

- Actor's Fund Field Day (1910)

- Marshall P. Wilder (1912)(as himself)

- Chumps (1912)

- The Five Senses (1912)

- The Pipe (1912)

- The Greatest Thing in the World(1912)

- Professor Optimo (1912)

- Mockery (1912)

- The Godmother (1912)

- The Curio Hunters (1912)

- The Widow's Might (1913)