Gallienus (Latin:

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus Augustus;

c. 218 – 268) was

Roman Emperor

with his father

Valerian

from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to

268. He ruled during the

Crisis of the Third Century

that nearly caused

the collapse of the empire. While he won a number of military victories, he was

unable to prevent the secession of important provinces.

Life

Rise to power

The exact birth date of Gallienus is unknown. The Greek chronicler

John Malalas

and the Epitome de Caesaribus

report that he was about 50 years old at the time of his death, meaning he was

born around 218. He was the son of emperor

Valerian

and

Mariniana

, who may have been of senatorial

rank, possibly the daughter of

Egnatius Victor Marinianus

, and his brother was

Valerianus Minor

. Inscriptions on coins connect

him with Falerii

in

Etruria

, which may have been his birthplace; it

has yielded many inscriptions relating to his mother's family, the Egnatii.[3]

Gallienus married

Cornelia Salonina

about ten years before his

accession to the throne. She was the mother of three princes:

Valerian II

, who died in 258;

Saloninus

, who was named co-emperor but was

murdered in 260 by the army of general Postumus; and

Marinianus

, who was killed in 268, shortly

after his father was assassinated.

When

Valerian

was proclaimed Emperor on 22 October

253, he asked the

Senate

to ratify the elevation of Gallienus to

Caesar and

Augustus

. He was also designated

Consul Ordinarius

for 254. As

Marcus Aurelius

and his adopted brother

Lucius Verus

had done a century earlier,

Gallienus and his father divided the Empire. Valerian left for the East to stem

the Persian threat, and Gallienus remained in Italy to repel the Germanic tribes

on the Rhine

and

Danube

.

Division of the empire

had become necessary due

to its sheer size and the numerous threats it faced, and it facilitated

negotiations with enemies who demanded to communicate directly with the emperor.

Early

reign and the revolt of Ingenuus

Gallienus spent most of his time in the provinces of the Rhine area (Germania

Inferior,

Germania Superior

,

Raetia

, and

Noricum

), though he almost certainly visited

the Danube

area and

Illyricum

during 253 to 258. According to

Eutropius and Aurelius Victor, he was particularly energetic and successful in

preventing invaders from attacking the German provinces and Gaul, despite the

weakness caused by Valerian's march on Italy against

Aemilianus

in 253. According to numismatic

evidence, he seems to have won many victories there, and a victory in

Roman Dacia

might also be dated to that period.

Even the hostile Latin tradition attributes success to him at this time.

In 255 or 257, Gallienus was made Consul again, suggesting that he briefly

visited Rome on those occasions, although no record survives. During his Danube

sojourn (Drinkwater suggests in 255 or 256), he proclaimed his elder son

Valerian II

Caesar and thus official heir to

himself and Valerian I; the boy probably joined Gallienus on campaign at that

time, and when Gallienus moved west to the Rhine provinces in 257, he remained

behind on the Danube as the personification of Imperial authority.

Sometime between 258 and 260 (the exact date is unclear), while Valerian was

distracted with the ongoing invasion of Shapur in the East, and Gallienus was

preoccupied with his problems in the West,

Ingenuus

, governor of at least one of the

Pannonian provinces, took advantage and declared himself emperor. Valerian II

had apparently died on the Danube, most likely in 258. Ingenuus may have been

responsible for that calamity. Alternatively, the defeat and capture of Valerian

at the

battle of Edessa

may have been the trigger for

the subsequent revolts of Ingenuus,

Regalianus

, and

Postumus

.[12]

In any case, Gallienus reacted with great speed. He left his son

Saloninus

as Caesar at

Cologne

, under the supervision of Albanus (or

Silvanus) and the military leadership of Postumus. He then hastily crossed the

Balkans

, taking with him the new cavalry corps

(comitatus) under the command of

Aureolus

and defeated Ingenuus at

Mursa

or

Sirmium

.The victory must be attributed mainly

to the cavalry and its brilliant commander. Ingenuus was killed by his own

guards or committed suicide by drowning himself after the fall of his capital,

Sirmium.

Invasion of the

Alamanni

A major invasion by the

Alemanni

and other Germanic tribes occurred

between 258 and 260 (it is hard to fix the precise date of these

events),probably due to the vacuum left by the withdrawal of troops supporting

Gallienus in the campaign against Ingenuus.

Franks

broke through the lower Rhine, invading

Gaul, some reaching as far as southern Spain, sacking Tarraco (modern

Tarragona

).The Alamanni invaded, probably

through

Agri Decumates

(an area between the upper Rhine

and the upper Danube), likely followed by the

Juthungi

. After devastating Germania Superior

and Raetia (parts of southern

France

and

Switzerland

), they entered Italy, the first

invasion of the Italian peninsula, aside from its most remote northern regions,

since Hannibal

500 years before. When invaders

reached the outskirts of Rome, they were repelled by an improvised army

assembled by the Senate, consisting of local troops (probably prǣtorian guards)

and the strongest of the civilian population.On their retreat through northern

Italy, they were intercepted and defeated in the

battle of Mediolanum

(near present day

Milan

) by Gallienus' army, which had advanced

from Gaul, or from the Balkans after dealing with the Franks.The battle of

Mediolanum was decisive, and the Alamanni didn't bother the empire for the next

ten years. The Juthungi managed to cross the Alps with their valuables and

captives from Italy. An historian in the 19th century suggested that the

initiative of the Senate gave rise to jealousy and suspicion by Gallienus, thus

contributing to his exclusion of senators from military commands.

The revolt of

Regalianus

Around the same time,

Regalianus

, a military commander of

Illyricum

, was proclaimed Emperor. The reasons

for this are unclear, and the Historia Augusta (almost the sole resource

for these events) does not provide a credible story. It is possible the seizure

can be attributed to the discontent of the civilian and military provincials,

who felt the defense of the province was being neglected.

Regalianus held power for some six months and issued coins bearing his image.

After some success against the

Sarmatians

, his revolt was put down by the

invasion of Roxolani

into

Pannonia

, and Regalianus himself was killed

when the invaders took the city of

Sirmium

. There is a suggestion that Gallienus

invited Roxolani to attack Regalianus, but other historians dismiss the

accusation.[25]

It is also suggested that the invasion was finally checked by Gallienus near

Verona

and that he directed the restoration of

the province, probably in person.

Capture of Valerian, revolt of Macrianus

In the East, Valerian was confronted with serious troubles. A band of

Scythians

set a naval raid against

Pontus

, in the northern part of modern Turkey.

After ravaging the province, they moved south into

Cappadocia

. Valerian led troops to intercept

them but failed, perhaps because of a plague that gravely weakened his army, as

well as the contemporary invasion of northern

Mesopotamia

by

Shapur I

, ruler of the

Sassanid Empire

.

In 259 or 260, the Roman army was defeated in the

Battle of Edessa

, and Valerian was taken

prisoner. Shapur's army raided

Cilicia

and

Cappadocia

(in present day

Turkey

), sacking, as Shapur's inscriptions

claim, 36 cities. It took a rally by an officer

Callistus

(Balista), a fiscal official named

Fulvius Macrianus

, the remains of the Eastern

Roman legions, and

Odenathus

and his

Palmyrene

horsemen to turn the tide against

Shapur. The Persians were driven back, but Macrianus proclaimed his two sons

Quietus

and

Macrianus

(sometimes misspelled Macrinus) as

emperors. Coins struck for them in major cities of the East indicate

acknowledgement of the usurpation. The two Macriani left Quietus, Ballista, and,

presumably, Odenathus to deal with the Persians while they invaded Europe with

an army of 30,000 men, according to the Historia Augusta. At first they

met no opposition. The Pannonian legions joined the invaders, being resentful of

the absence of Gallienus. He sent his successful commander Aureolus against the

rebels, however, and the decisive battle was fought in the spring or early

summer of 261, most likely in Illyricum, although

Zonaras

locates it in Pannonia. In any case,

the army of the usurpers surrendered, and their two leaders were killed.

In the aftermath of the battle, the rebellion of Postumus had already

started, so Gallienus had no time to deal with the rest of the usurpers, namely

Balista and Quietus. He came to an agreement with Odenathus, who had just

returned from his victorious Persian expedition. Odenathus received the title of

dux Romanorum and besieged the usurpers, who were based at

Emesa

. Eventually, the people of Emesa killed

Quietus, and Odenathus arrested and executed Balista about November 261.

The revolt of Postumus

After the defeat at Edessa, Gallienus lost control over the provinces of

Britain, Spain, parts of Germania, and a large part of Gaul when another

general, Postumus

, declared his own realm (usually known

today as the

Gallic Empire

). The revolt partially coincided

with that of

Macrianus

in the East. Gallienus had installed

his son Saloninus and his guardian,

Silvanus

, in Cologne in 258. Postumus, a

general in command of troops on the banks of the Rhine, defeated some raiders

and took possession of their spoils. Instead of returning it to the original

owners, he preferred to distribute it amongst his soldiers. When news of this

reached Silvanus, he demanded the spoils be sent to him. Postumus made a show of

submission, but his soldiers mutinied and proclaimed him Emperor. Under his

command, they besieged Cologne, and after some weeks the defenders of the city

opened the gates and handed Saloninus and Silvanus to Postumus, who had them

killed. The dating of these events is not accurate, but they apparently occurred

just before the end of 260. Postumus claimed the consulship for himself and one

of his associates, Honoratianus, but according to D.S. Potter, he never tried to

unseat Gallienus or invade Italy.

Upon receiving news of the murder of his son, Gallienus began gathering

forces to face Postumus. The invasion of the Macriani forced him to dispatch

Aureolus with a large force to oppose them, however, leaving him with

insufficient troops to battle Postumus. After some initial defeats, the army of

Aureolus, having defeated the Macriani, rejoined him, and Postumus was expelled.

Aureolus was entrusted with the pursuit and deliberately allowed Postumus to

escape and gather new forces. Gallienus returned in 263 or 265 and surrounded

Postumus in an unnamed Gallic city. During the siege, Gallenus was severely

wounded by an arrow and had to leave the field. The standstill persisted until

the death of Gallienus, and the

Gallic Empire

remained independent until 274.

The revolt of

Aemilianus

In 262, the mint in

Alexandria

started to again issue coins for

Gallienus, demonstrating that Egypt had returned to his control after

suppressing the revolt of the Macriani. In spring of 262, the city was wrenched

by civil unrest as a result of a new revolt. The rebel this time was the prefect

of Egypt,

Lucius Mussius Aemilianus

, who had already

given support to the revolt of the Macriani. The correspondence of bishop

Dionysius of Alexandria

provides a colourful

commentary on the sombre background of invasion, civil war, plague, and famine

that characterized this age.

Knowing he could not afford to lose control of the vital Egyptian granaries,

Gallienus sent his general Theodotus against Aemilianus, probably by a naval

expedition. The decisive battle probably took place near Thebes, and the result

was a clear defeat of Aemilianus. In the aftermath, Gallienus became Consul

three more times in 262, 264, and 266.

Herulian invasions, revolt of Aureolus, conspiracy and death

In the years 267–269, Goths and other barbarians invaded the empire in great

numbers. Sources are extremely confused on the dating of these invasions, the

participants, and their targets. Modern historians are not even able to discern

with certainty whether there were two or more of these invasions or a single

prolonged one. It seems that, at first, a major naval expedition was led by the

Heruli

starting from north of the

Black Sea

and leading in the ravaging of many

cities of Greece (among them,

Athens

and

Sparta

). Then another, even more numerous army

of invaders started a second naval invasion of the empire. The Romans defeated

the barbarians on sea first. Gallienus' army then won a battle in

Thrace

, and the Emperor pursued the invaders.

According to some historians, he was the leader of the army who won the great

Battle of Naissus

, while the majority believes

that the victory must be attributed to his successor,

Claudius II

.

In 268, at some time before or soon after the battle of Naissus, the

authority of Gallienus was challenged by

Aureolus

, commander of the cavalry stationed in

Mediolanum

(Milan),

who was supposed to keep an eye on

Postumus

. Instead, he acted as deputy to

Postumus until the very last days of his revolt, when he seems to have claimed

the throne for himself. The decisive battle took place at what is now

Pontirolo Nuovo

near Milan; Aureolus was

clearly defeated and driven back to Milan. Gallienus laid siege to the city but

was murdered during the siege. There are differing accounts of the murder, but

the sources agree that most of Gallienus' officials wanted him dead.[44]

According to the

Historia Augusta

, an unreliable source compiled

long after the events it describes, a conspiracy was led by the commander of the

guard

Aurelius Heraclianus

and Marcianus.

Cecropius, commander of the Dalmatians, spread the word that the forces of

Aureolus were leaving the city, and Gallienus left his tent without his

bodyguard, only to be struck down by Cecropius.One version has Claudius selected

as Emperor by the conspirators, another chosen by Gallienus on his death bed;

the Historia Augusta was concerned to substantiate the descent of the

Constantinian dynasty

from Claudius, and this

may explain its accounts, which do not involve Claudius in the murder. The other

sources (Zosimus

i.40 and

Zonaras

xii.25) report that the conspiracy was

organized by Heraclianus, Claudius, and

Aurelian

.

According to Aurelius Victor and Zonaras, on hearing the news that Gallienus

was dead, the Senate in Rome ordered the execution of his family (including his

brother Valerianus and son Marinianus) and their supporters, just before

receiving a message from Claudius to spare their lives and deify his

predecessor.

Arch of Gallienus

in Rome, 262 –

dedicated to, rather than built by, Gallienus.

Legacy

Gallienus was not treated favorably by ancient historians, partly due to the

secession of Gaul and

Palmyra

and his inability to win them back.

According to modern scholar Pat Southern, some historians now see him in a more

positive light.Gallienus produced some useful reforms. He contributed to

military history as the first to commission primarily

cavalry

units, the

Comitatenses

, that could be dispatched anywhere

in the Empire in short order. This reform arguably created a precedent for the

future emperors

Diocletian

and

Constantine I

.

The biographer

Aurelius Victor

reports that Gallienus forbade

senators

from becoming military commanders.

This policy undermined senatorial power, as more reliable

equestrian

commanders rose to prominence. In

Southern's view, these reforms and the decline in senatorial influence not only

helped Aurelian to salvage the Empire, but they also make Gallienus one of the

emperors most responsible for the creation of the

Dominate

, along with

Septimius Severus

, Diocletian, and Constantine

I.

By portraying himself with the attributes of the gods on his coinage,

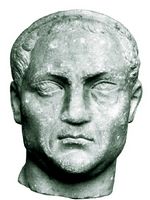

Gallienus began the final separation of the Emperor from his subjects.A late

bust of Gallienus (see above) depicts him with a largely blank face, gazing

heavenward, as seen on the famous stone head of

Constantine I

. One of the last rulers of Rome

to be theoretically called "Princeps", or First Citizen, Gallienus' shrewd

self-promotion assisted in paving the way for those who would be addressed with

the words "Dominus et Deus" (Lord and God). Husband of Mariniana | Father of Gallienus | Grandfather of Valerian II and Saloninus

Publius Licinius Valerianus (c. 200 - after 260), commonly known in English as Valerian or Valerian I, was the Roman Emperor from 253 to 260. Unlike

the majority of the pretenders during the Crisis of the Third Centuryy,

Valerian was of a noble and traditional senatorial family. Details of

his early life are elusive, but for his marriage to Egnatia Mariniana,

who gave him two sons: later emperor Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus

and Valerianus Minor. In 238 he was princeps senatus,

and Gordian I negotiated through him for Senatorial acknowledgement for

his claim as emperor. In 251, when Decius revived the censorship with

legislative and executive powers so extensive that it practically

embraced the civil authority of the emperor, Valerian was chosen censor

by the Senate, though he declined to accept the post. Under Decius he

was nominated governor of the Rhine provinces of Noricum and Raetia and

retained the confidence of his successor, Trebonianus Gallus, who asked

him for reinforcements to quell the rebellion of Aemilianus. Rule and fallValerian's

first act as emperor was to make his son Gallienus his colleague. In

the beginning of his reign the affairs in Europe went from bad to worse

and the whole West fell into disorder. In the East, Antioch had fallen

into the hands of a Sassanid vassal, Armenia was occupied by Shapur I

(Sapor). Valerian and Gallienus split the problems of the empire between

the two, with the son taking the West and the father heading East to

face the Persian threat. By 257, Valerian had

already recovered Antioch and returned the province of Syria to Roman

control but in the following year, the Goths ravaged Asia Minor. Later

in 259, he moved to Edessa, but an outbreak of plague killed a critical

number of legionaries, weakening the Roman position in Edessa which was

then besieged by the Persians. At the beginning of 260, Valerian was

defeated in the Battle of Edessa and he arranged a meeting with Shapur

to negotiate a peace settlement. The ceasefire was betrayed by Shapur

who seized him and held him prisoner for the remainder of his life.

Valerian's capture was a humiliating defeat for the Romans. Gibbon, in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire describes Valerian's fate: The

voice of history, which is often little more than the organ of hatred

or flattery, reproaches Sapor with a proud abuse of the rights of

conquest. We are told that Valerian, in chains, but invested with the

Imperial purple, was exposed to the multitude, a constant spectacle of

fallen greatness; and that whenever the Persian monarch mounted on

horseback, he placed his foot on the neck of a Roman emperor.

Notwithstanding all the remonstrances of his allies, who repeatedly

advised him to remember the vicissitudes of fortune, to dread the

returning power of Rome, and to make his illustrious captive the pledge

of peace, not the object of insult, Sapor still remained inflexible.

When Valerian sunk under the weight of shame and grief, his skin,

stuffed with straw, and formed into the likeness of a human figure, was

preserved for ages in the most celebrated temple of Persia; a more real

monument of triumph, than the fancied trophies of brass and marble so

often erected by Roman vanity. The tale is moral and pathetic, but the

truth of it may very fairly be called in question. The letters still

extant from the princes of the East to Sapor are manifest forgeries; nor

is it natural to suppose that a jealous monarch should, even in the

person of a rival, thus publicly degrade the majesty of kings. Whatever

treatment the unfortunate Valerian might experience in Persia, it is at

least certain that the only emperor of Rome who had ever fallen into the

hands of the enemy, languished away his life in hopeless captivity.

Valerian's massacre of 258According to the Catholic Encyclopedia article on Valerian: Pope

Sixtus was seized on 6 August, 258, in one of the Catacombs and was put

to death; Cyprian of Carthage suffered martyrdom on 14 September.

Another celebrated martyr was the Roman deacon St. Lawrence. In Spain

Bishop Fructuosus of Tarragona and his two deacons were put to death on

21 January, 259. There were also executions in the eastern provinces

(Eusebius, VII, xii). Taken altogether, however, the repressions were

limited to scattered spots and had no great success..

Death in captivityAn

early Christian source, Lactantius, maintained that for some time prior

to his death Valerian was subjected to the greatest insults by his

captors, such as being used as a human footstool by Shapur when mounting

his horse. According to this version of events, after a long period of

such treatment Valerian offered Shapur a huge ransom for his release. In

reply, according to one version, Shapur was said to have forced

Valerian to swallow molten gold (the other version of his death is

almost the same but it says that Valerian was killed by being flayed

alive) and then had the unfortunate Valerian skinned and his skin

stuffed with straw and preserved as a trophy in the main Persian temple.

It was further alleged by Lactantius that it was only after a later

Persian defeat against Rome that his skin was given a cremation and

burial. The role of a Chinese prince held hostage by Shapur I, in the

events following the death of Valerian has been frequently debated by

historians, without reaching any definitive conclusion.

The Humiliation of Emperor Valerian by Shapur I, pen and ink, Hans Holbein the Younger, ca. 1521

Some

modern scholars believe that, contrary to Lactantius' account, Shapur I

sent Valerian and some of his army to the city of Bishapur where they

lived in relatively good condition. Shapur used the remaining soldiers

in engineering and development plans. Band-e Kaisar (Caesar's

dam) is one of the remnants of Roman engineering located near the

ancient city of Susa. In all the stone carvings on Naghshe-Rostam, in

Iran, Valerian is respected by holding hands with Shapur I, in sign of

submission. It is generally supposed that some of

Lactantius' account is motivated by his desire to establish that

persecutors of the Christians died fitting deaths; the story was

repeated then and later by authors in the Roman Near East "fiercely

hostile" to Persia. Other modern scholars tend to give at least some credence to Lactantius' account. Valerian

and Gallienus' joint rule was threatened several times by usurpers.

Despite several usurpation attempts, Gallienus secured the throne until

his own assassination in 268. Owing to imperfect and often contradictory sources, the chronology and details of this reign are very uncertain.

Publius Licinius Cornelius Valerianus (died 258), also known

as Valerian II, was the eldest son of Roman Emperor Gallienus and Augusta

Cornelia Salonina who was of Greek origin and grandson of the Emperor Valerian

who was of a noble and traditional senatorial family.

Shortly after his acclamation as Emperor (Augustus) Valerian

made Gallienus his co-Emperor and his grandson, Valerian, Caesar, in 256. (For

a discussion of the dynastic politics that motivated this process, see the

related article on Saloninus).

The young Caesar was then established in Sirmium to

represent the Licinius family in the government of the troubled Illyrian

provinces while Gallienus transferred his attentions to Germany to deal with

barbarian incursions into Gaul. Because of his youth (he was probably no more

than fifteen at the time), Valerian was put under the guardianship of Ingenuus,

who seems to have held an extraordinary command as governor of the Illyrian

provinces, i.e. Upper and Lower Pannonia and Upper and Lower Moesia.

It is reported that Salonina was not happy with this

arrangement. Although she could not publicly dispute the decisions of Valerian,

the pater patriae which had been formally agreed by her husband, Gallienus, she

suspected Ingenuus's motives and asked an officer called Valentinus, otherwise

unknown, to keep an eye on him. Despite this precaution, Valerian died in early

258 in circumstances sufficiently suspicious for Gallienus to attempt to demote

Ingenuus. It was this action that sparked the attempted usurpation of the

Empire by Ingenuus, who had widespread support among the Illyrian garrisons and

the provincial establishment.

As in case of his brother, Saloninus, who was later made

Caesar in Gaul, the little we know of Valerian's short reign in Illyria is

indicative of the chaotic situation that prevailed on the northern frontiers of

the Empire under Valerian and Gallienus. It seems to show that the mere

presence of a member of the Imperial House in a troubled region was not

sufficient to assuage local fears of being neglected by the distant Emperor.

The local Caesar had to wield undisputed authority in his region and command

the resources and the experience to deal with the internal and external threats

to its security. Diocletian and Maximian seem to have understood this when they

set up Constantius Chlorus and Galerius as Caesars in Gaul and Illyria

respectively some thirty-five years later. |