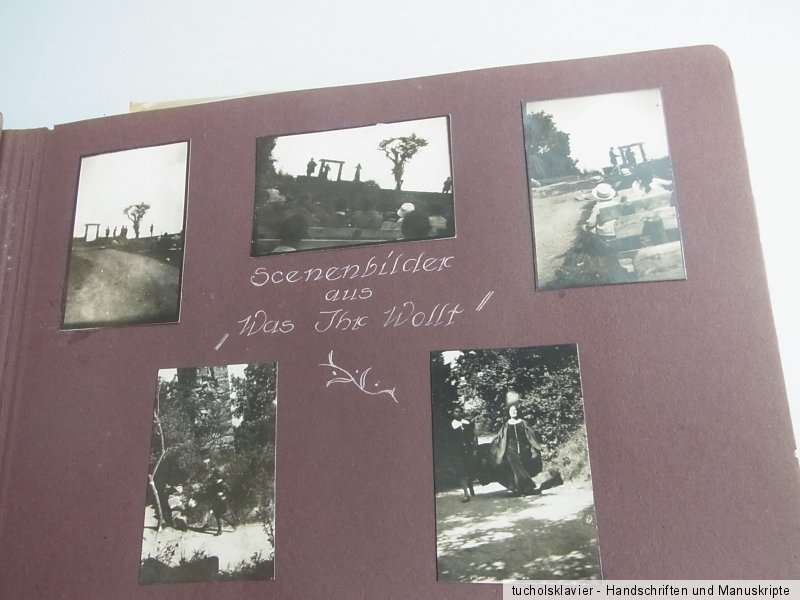

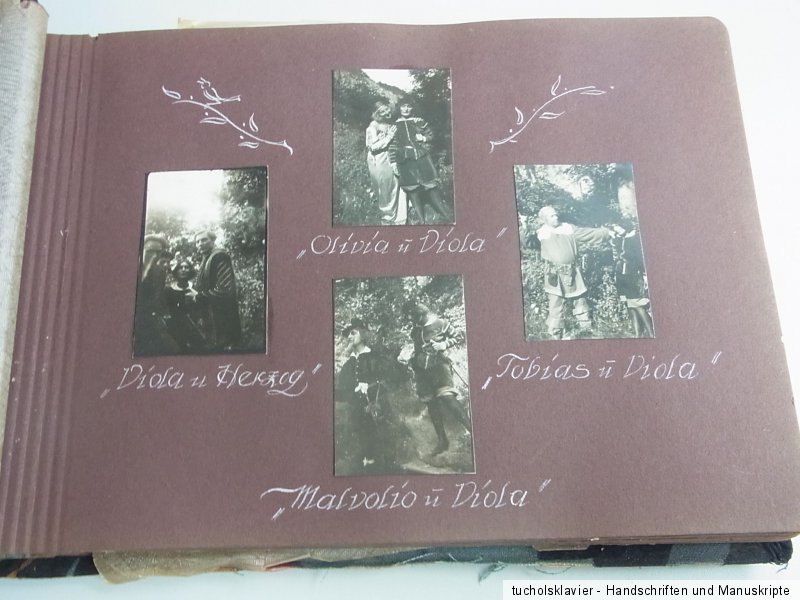

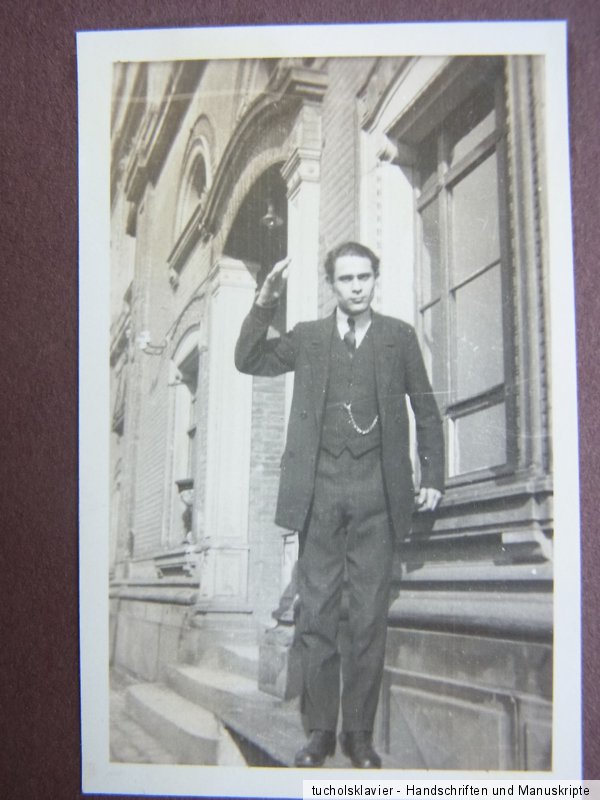

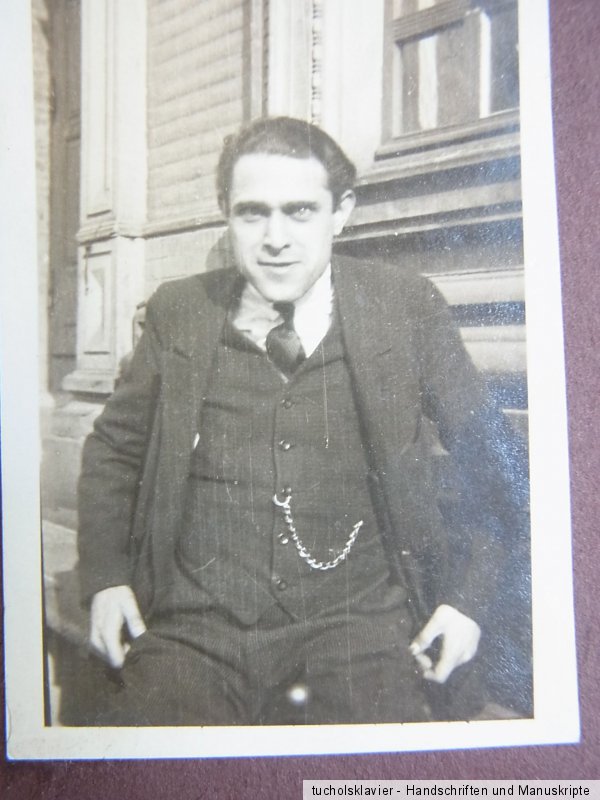

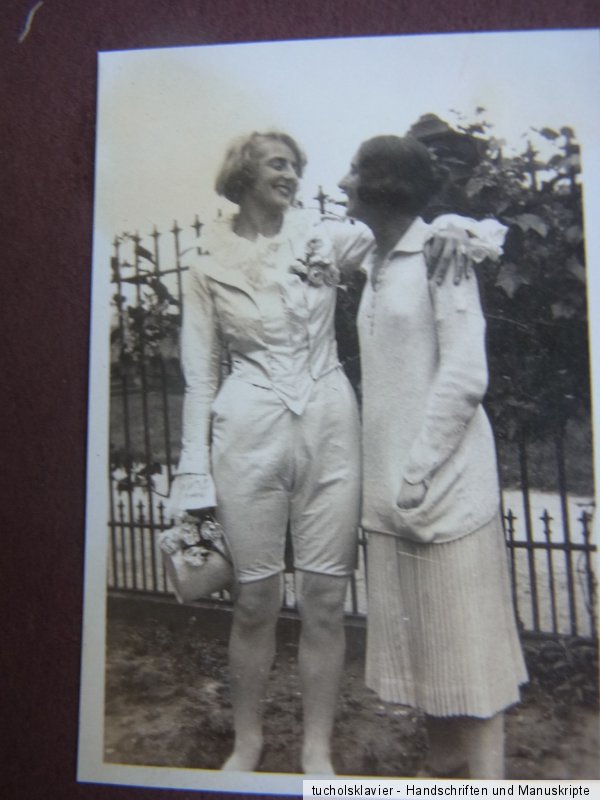

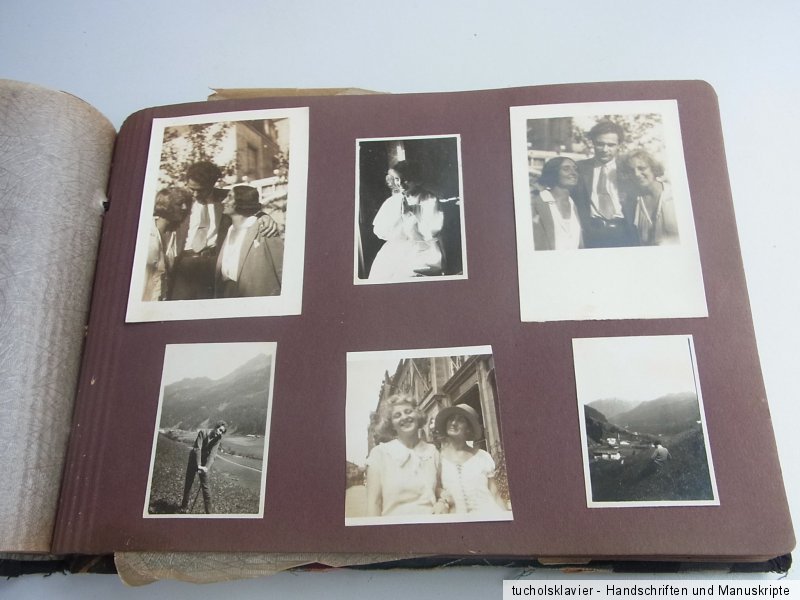

Photo album 1924/25: Open-air THEATER (actor)

Description

– Wsee more pictures below! –

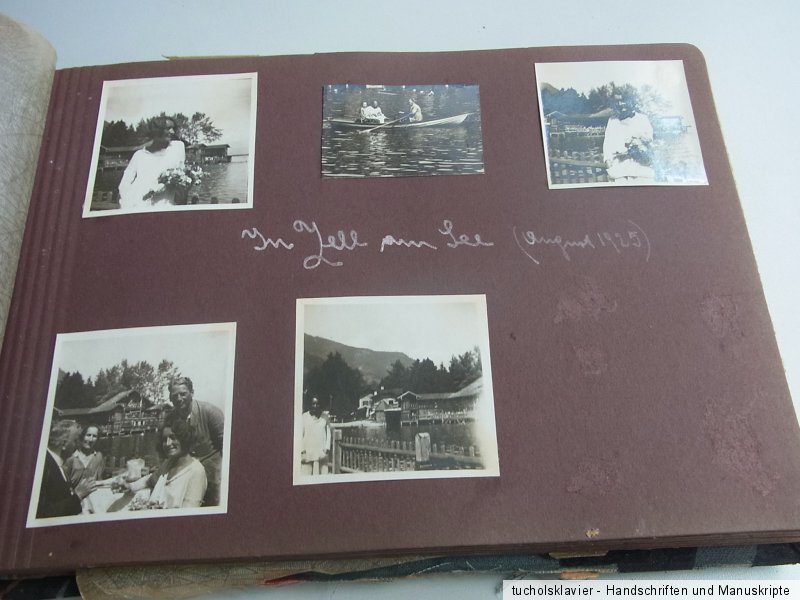

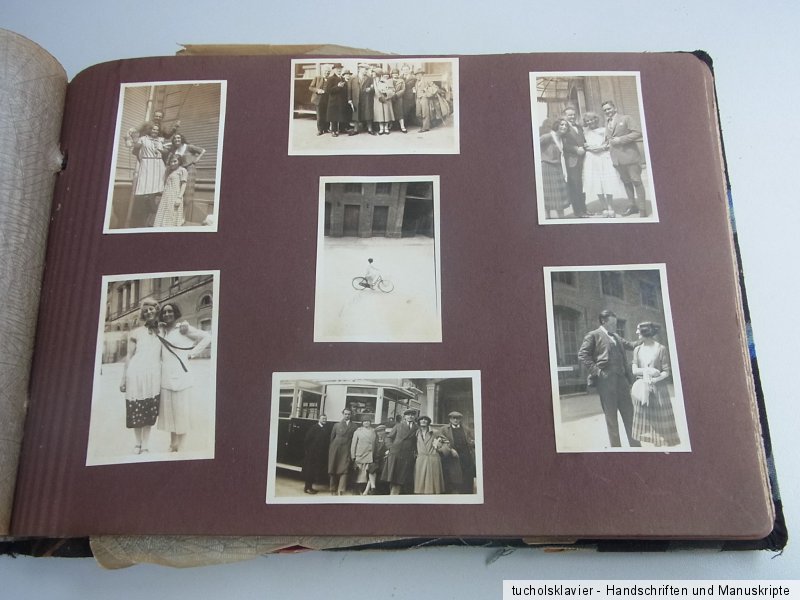

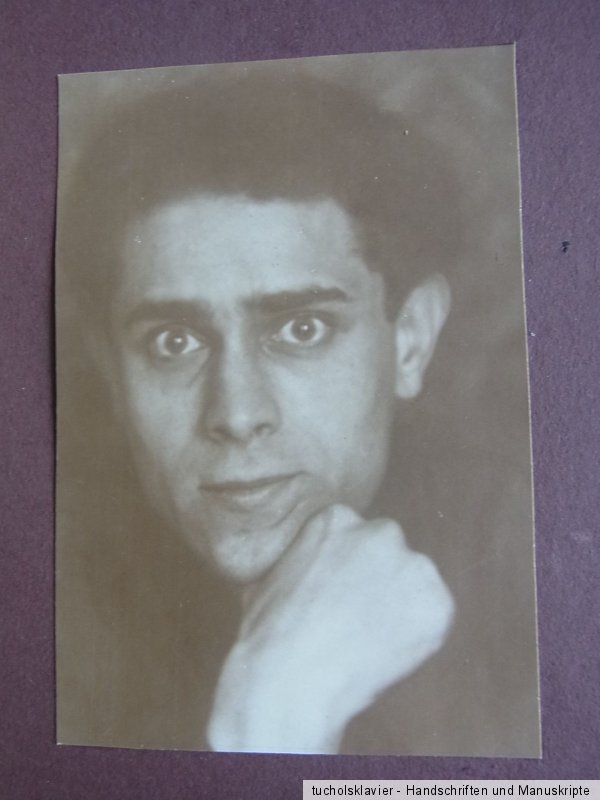

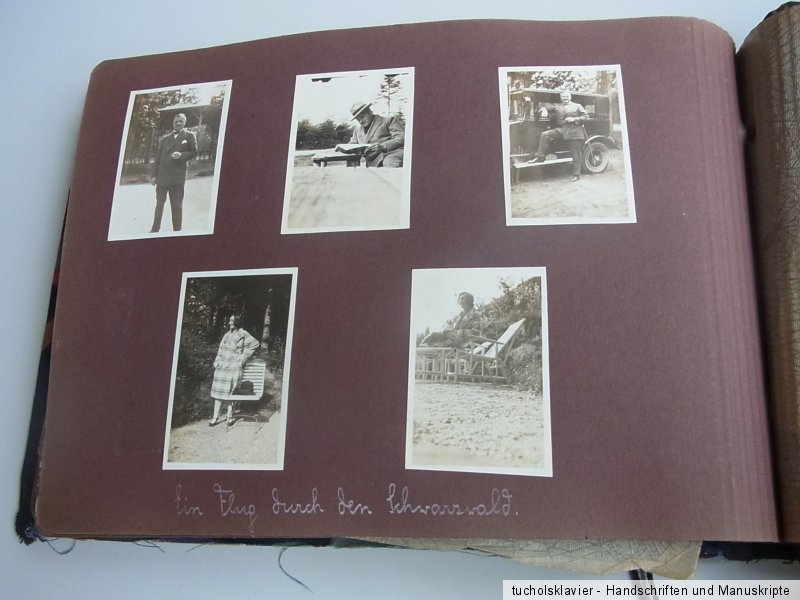

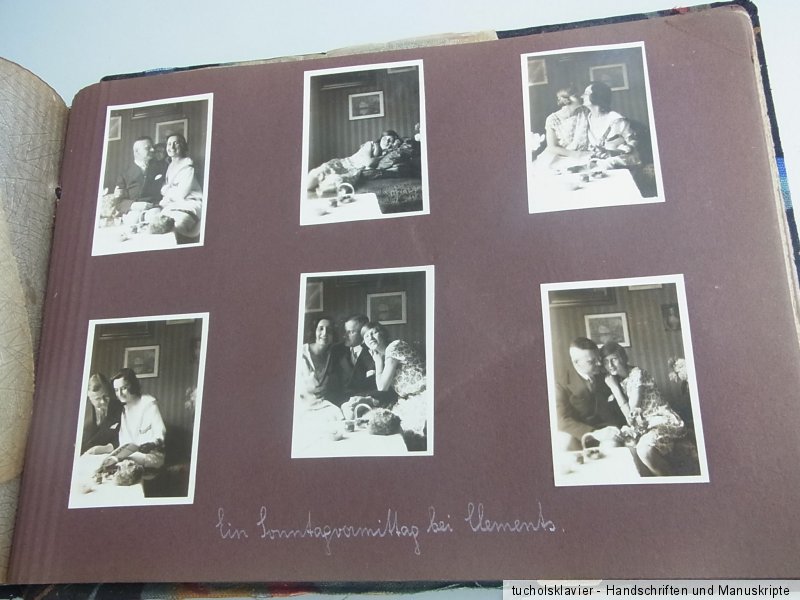

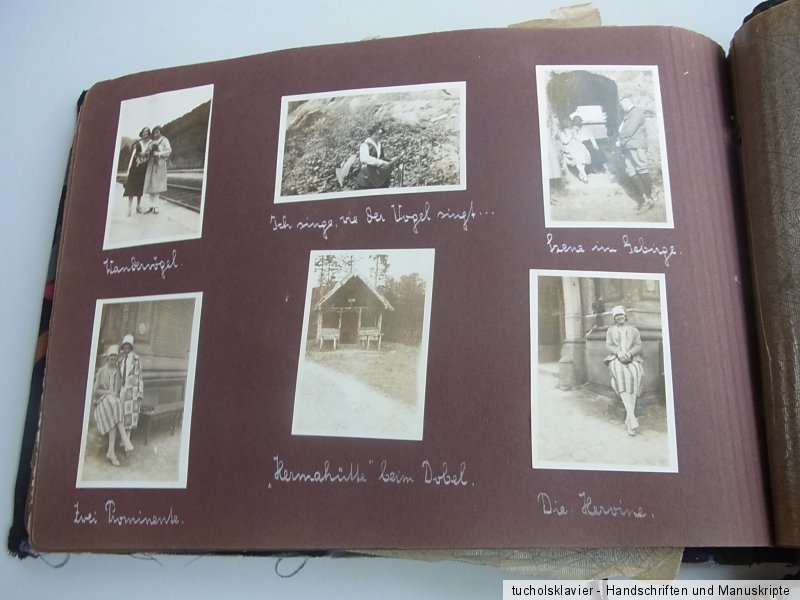

You are bidding on one interesting photo album from 1924 (no dating after 1925), with ins. 130 photos.

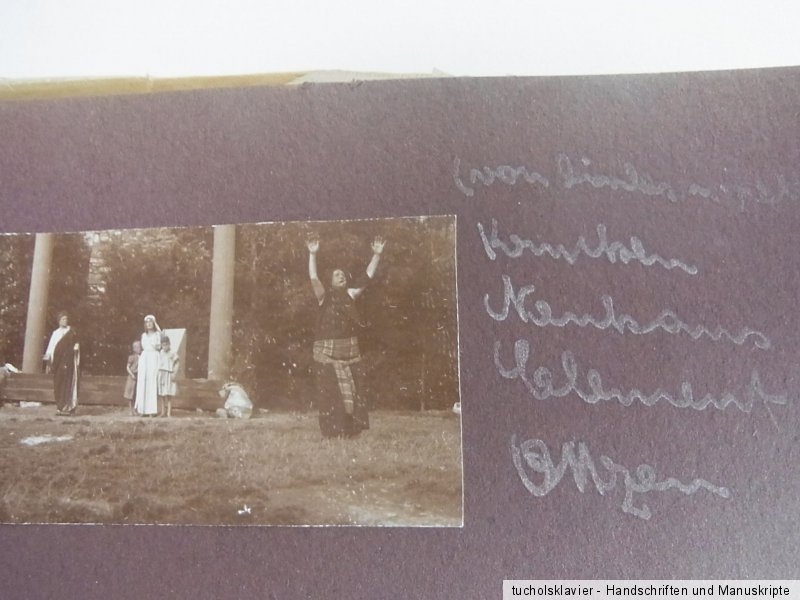

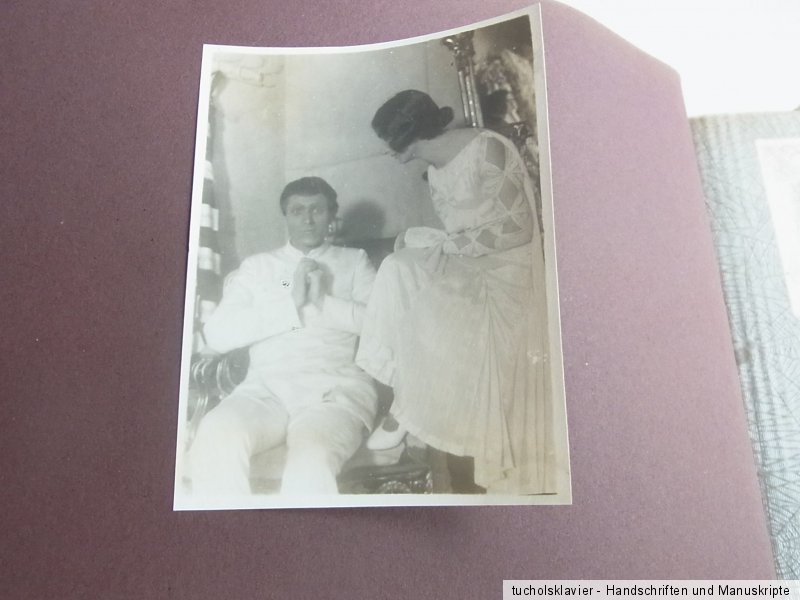

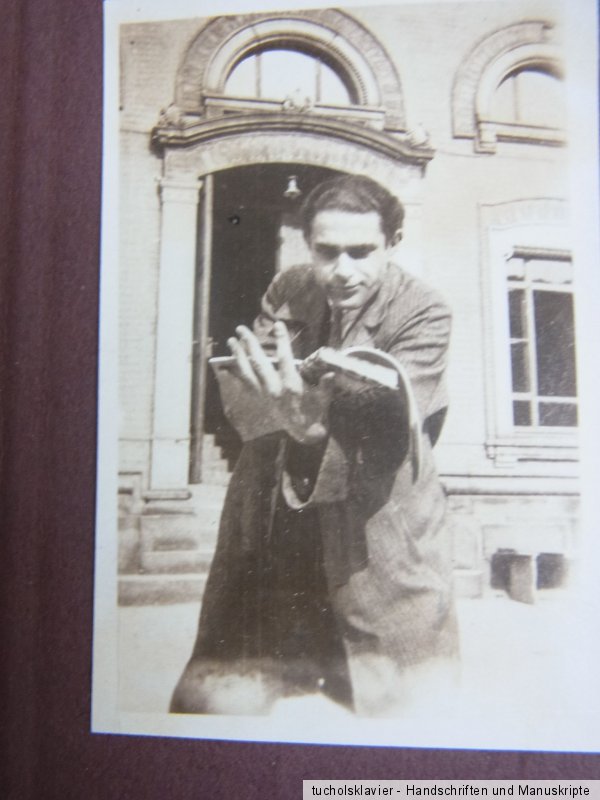

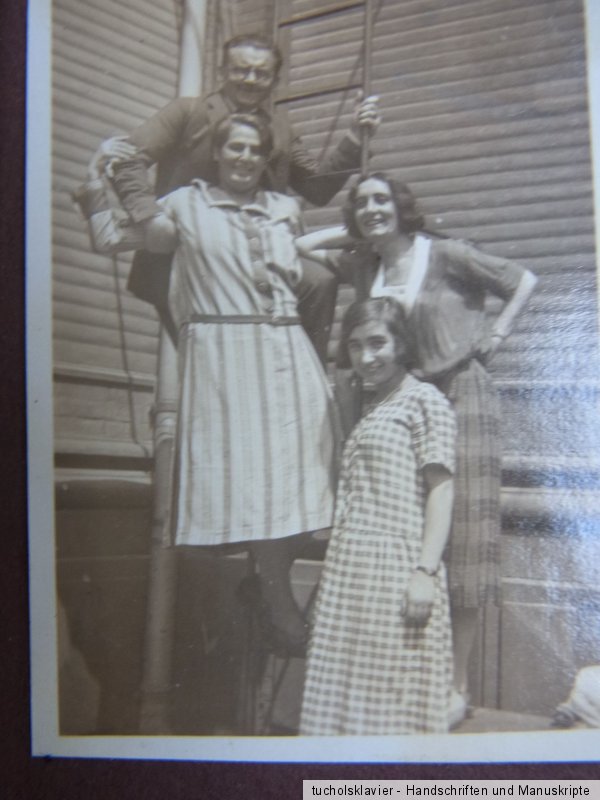

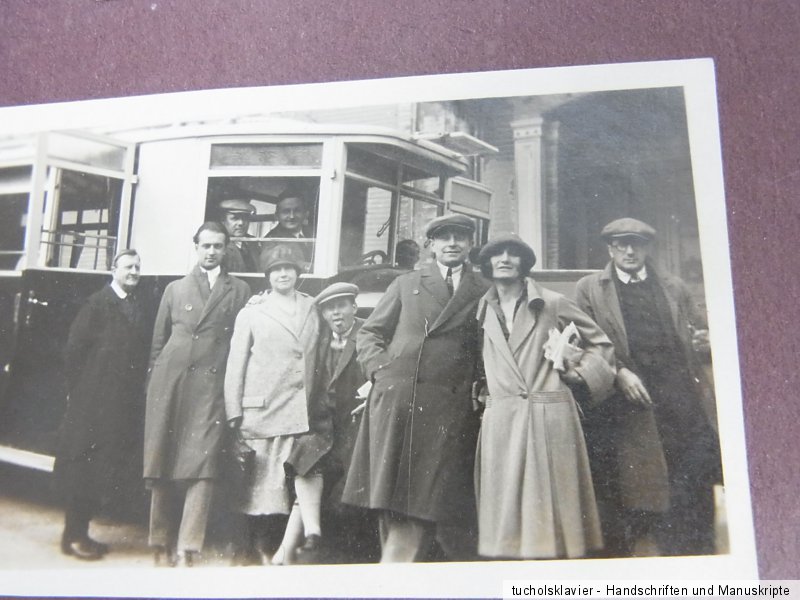

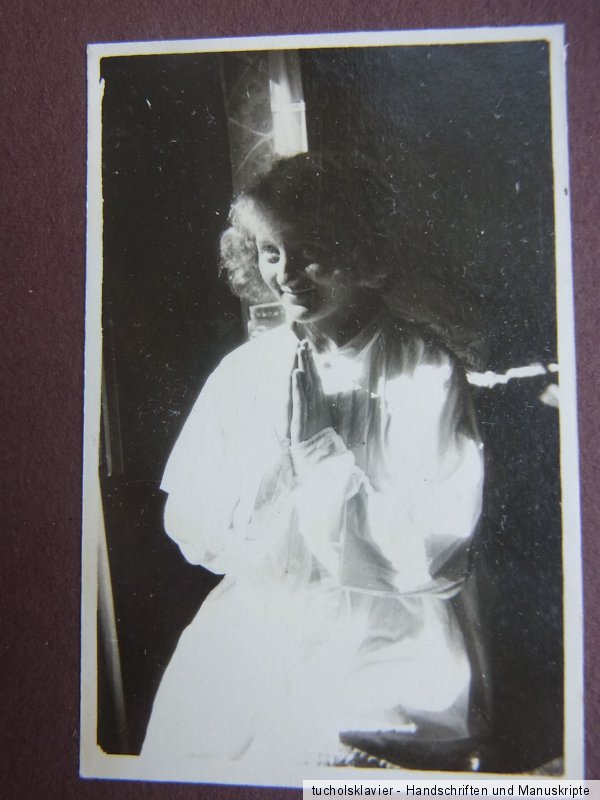

Lead by Acting; several photos of Outdoor theater scenes.

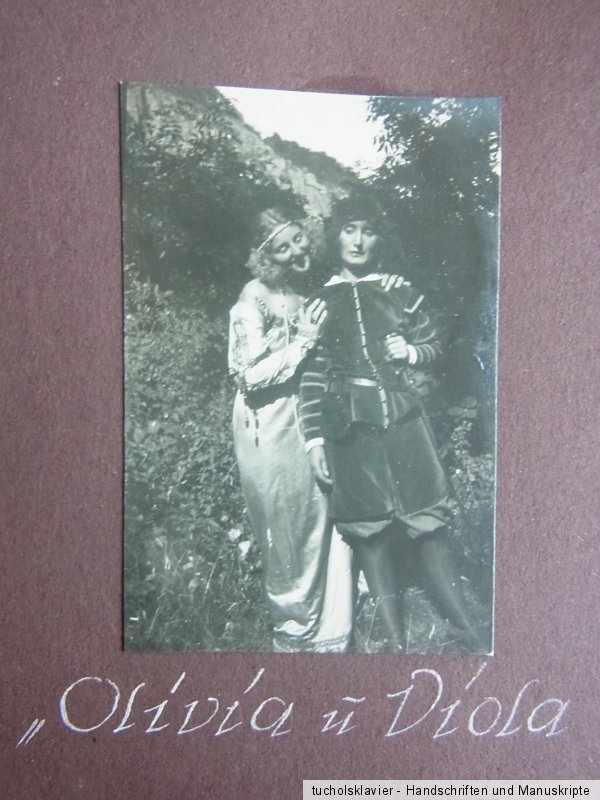

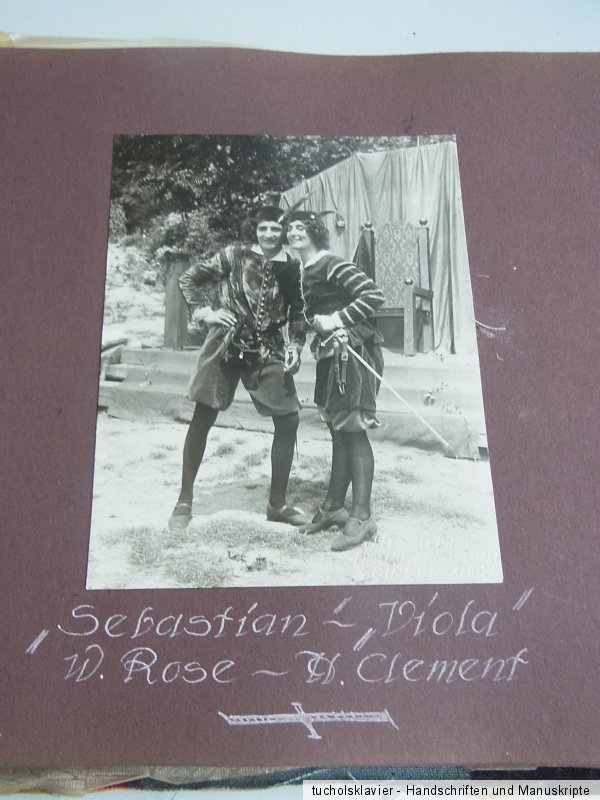

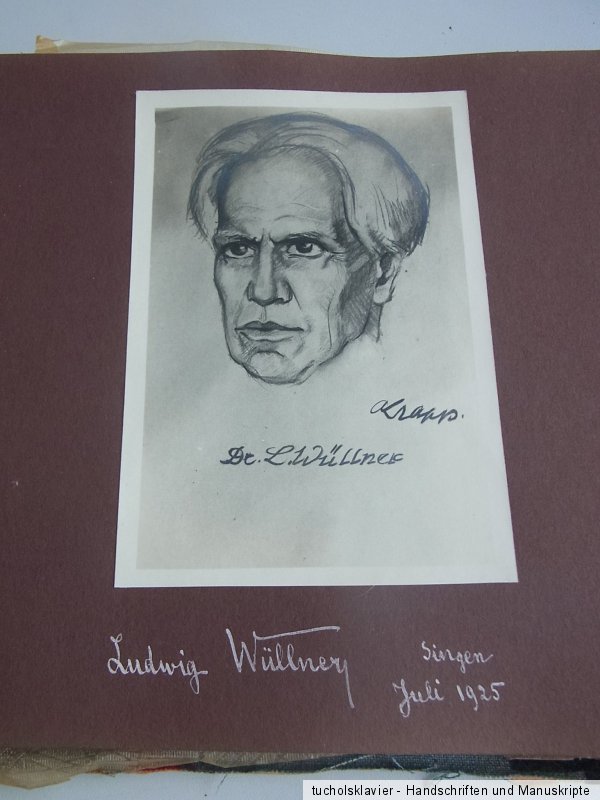

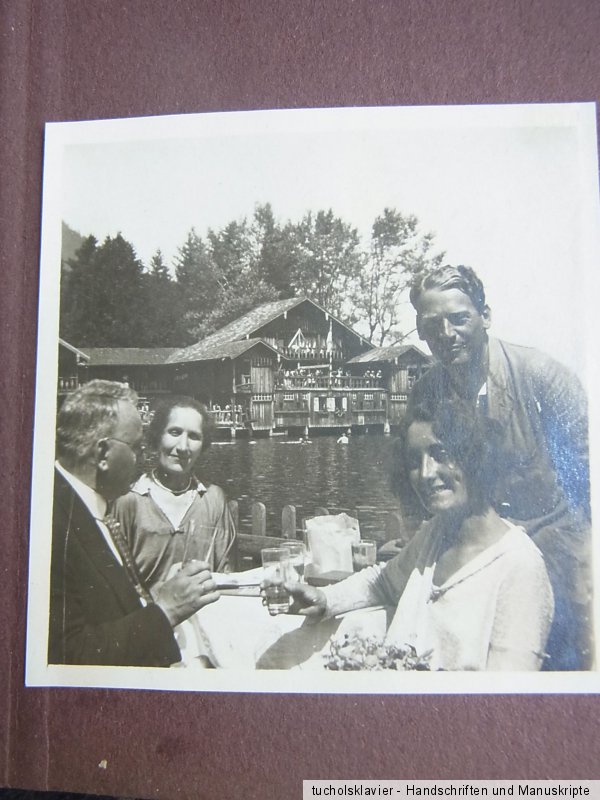

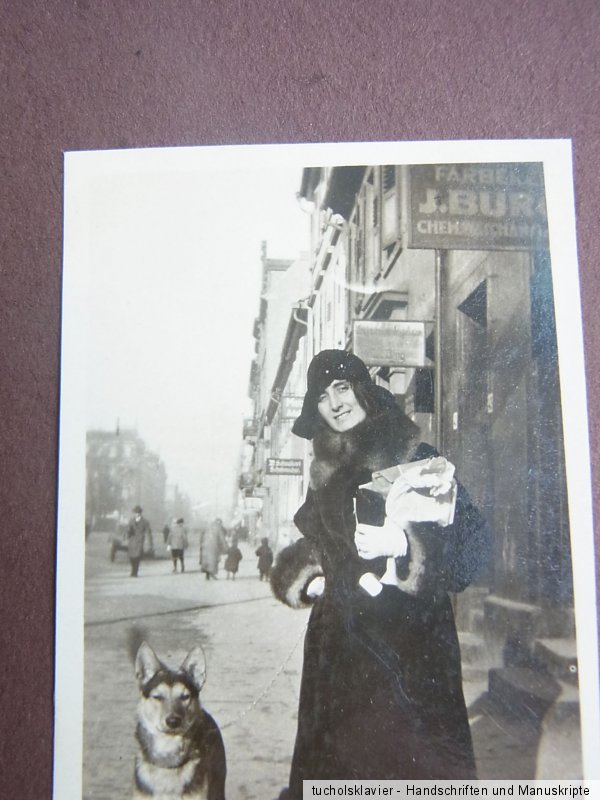

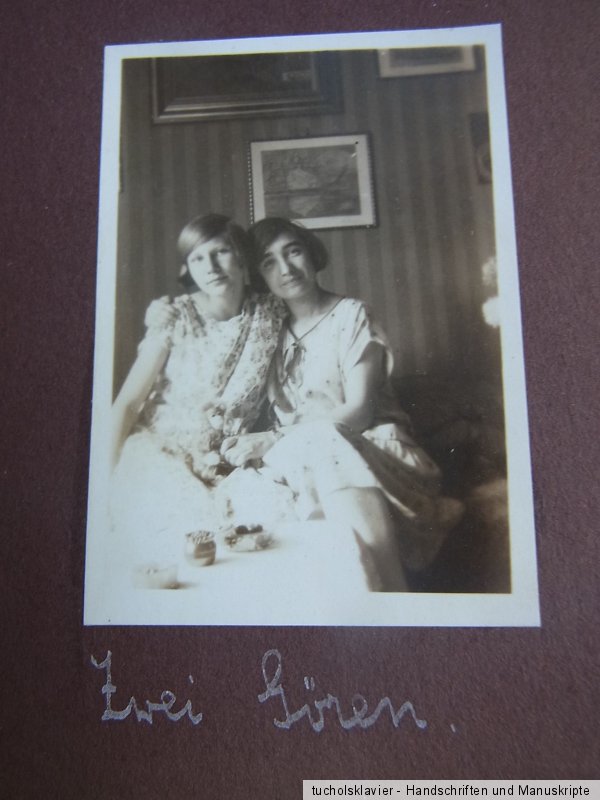

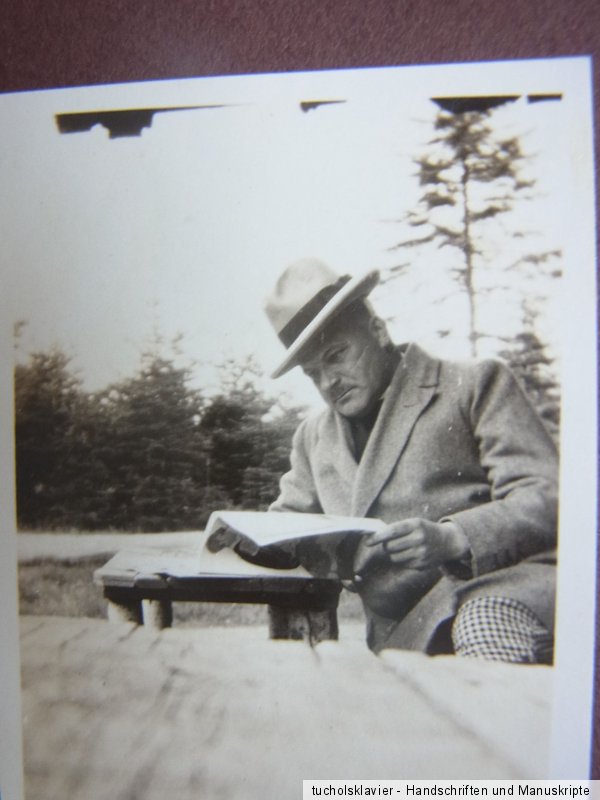

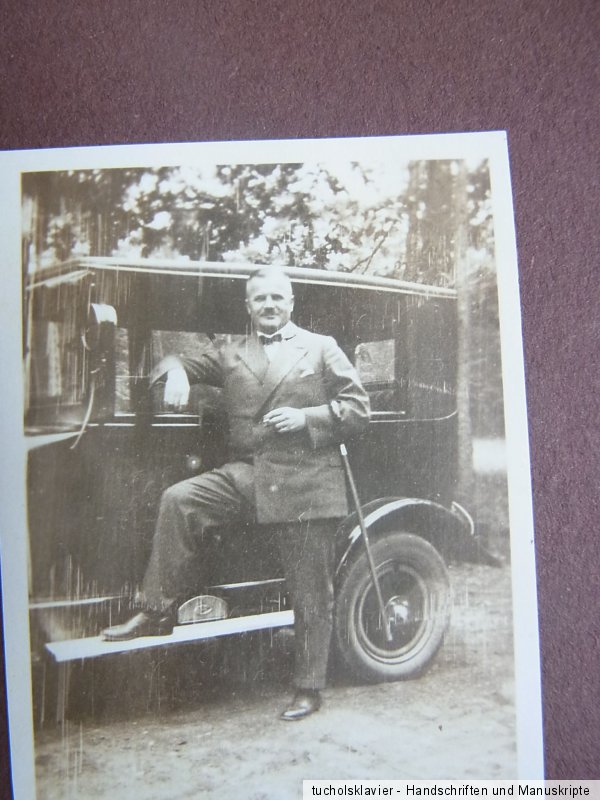

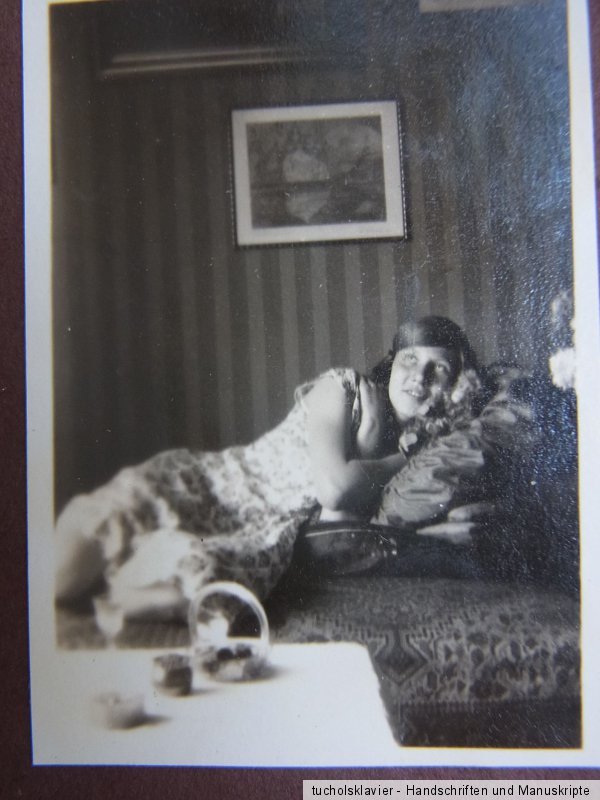

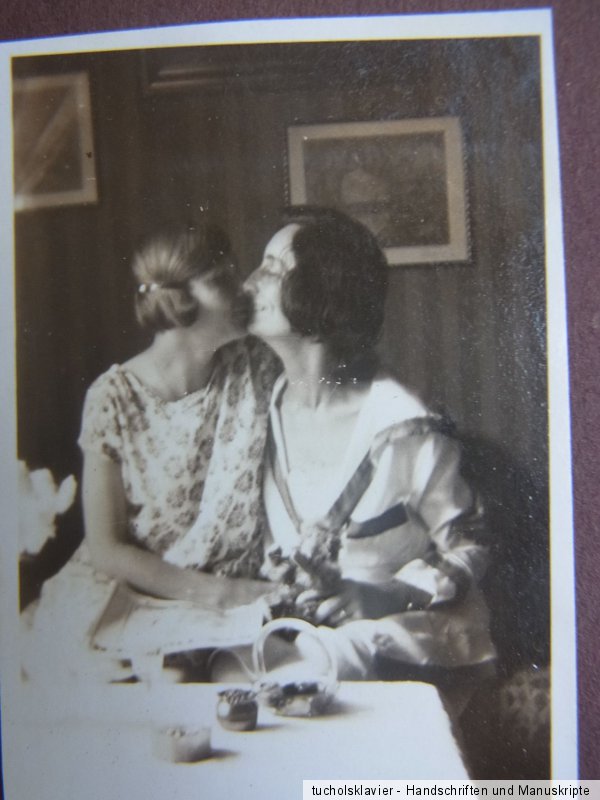

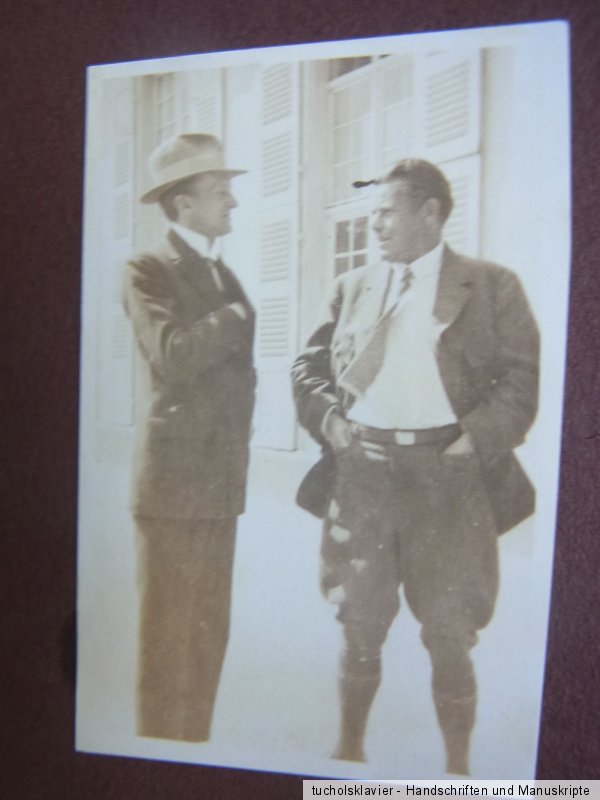

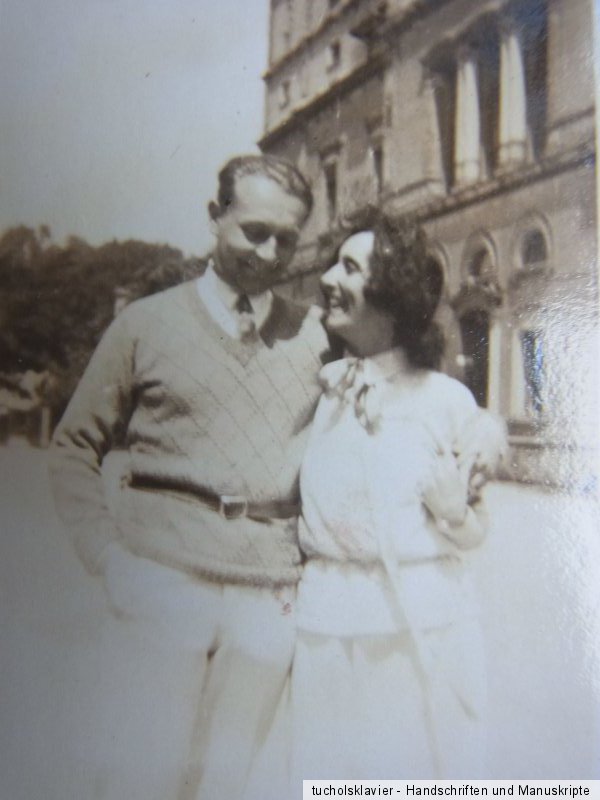

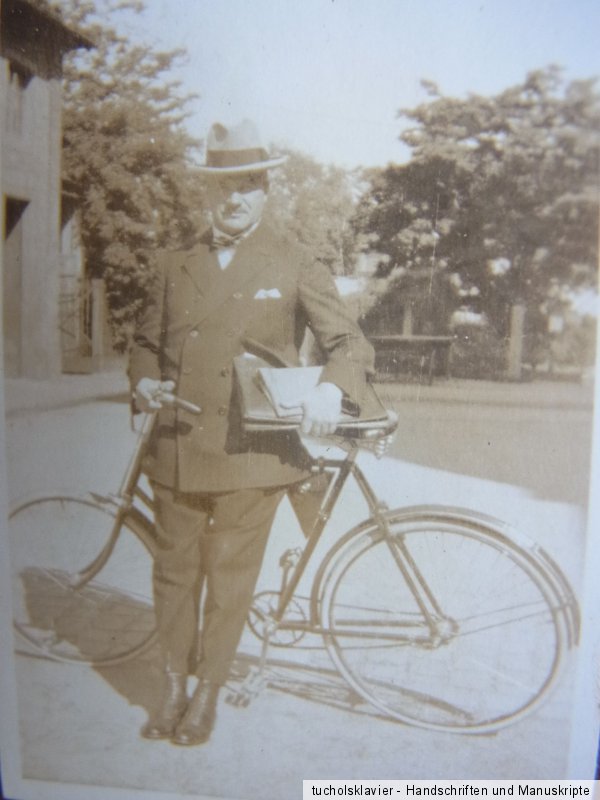

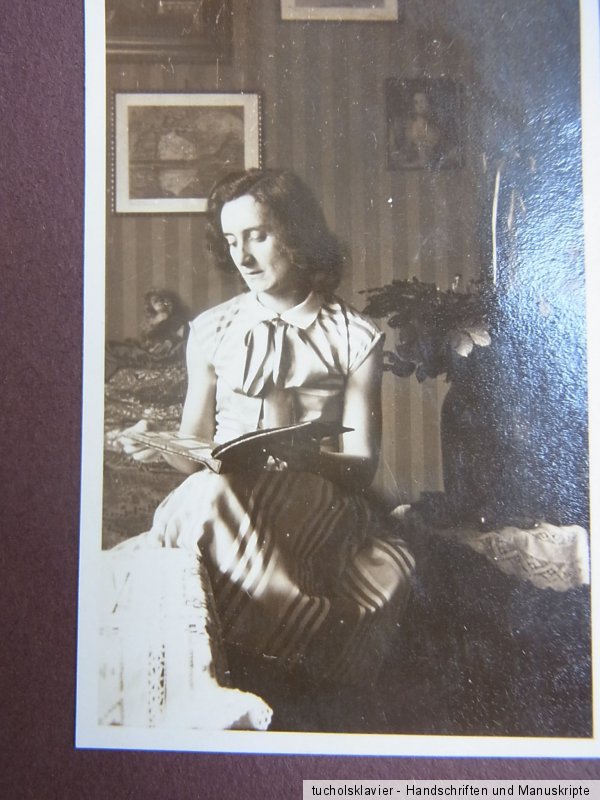

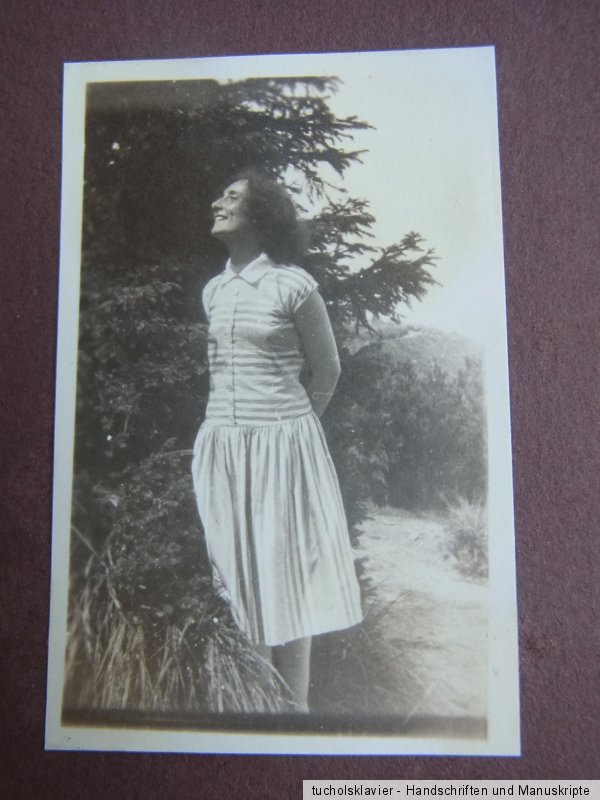

The actress can be seen several times Herma Clement (1898-1973); there are even a number of photos from a visit with her family. In addition, you can see, among other things: Robert Bürkner (1887-1962, once with his wife Hansi Nassee), Willi Rose (1902-1978), Ludwig Wüllner (1858-1938)...

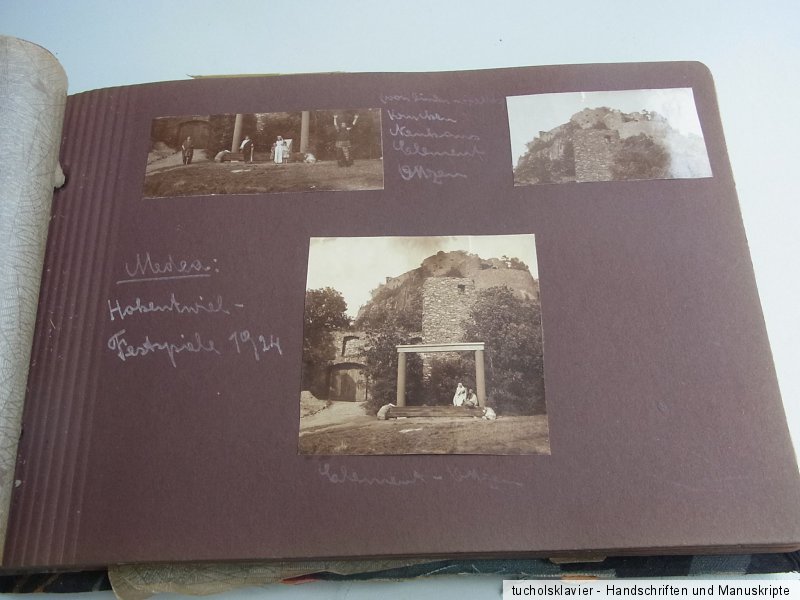

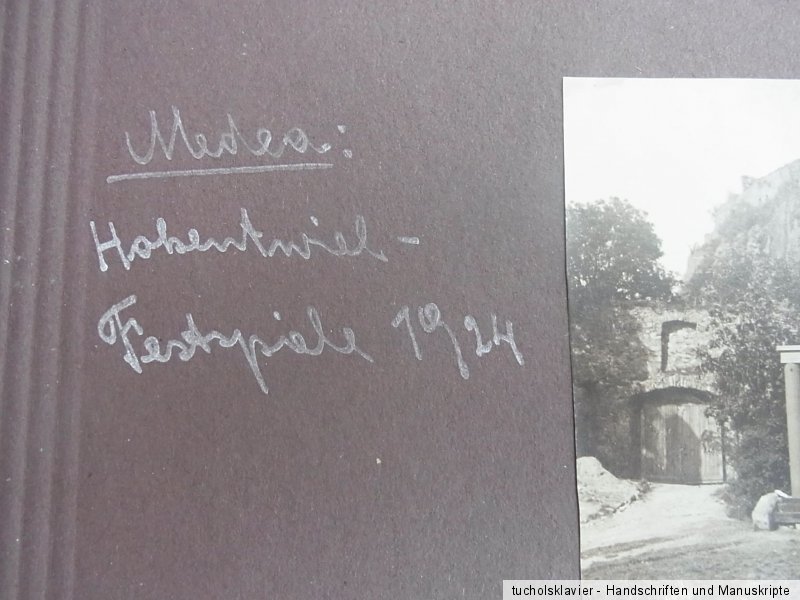

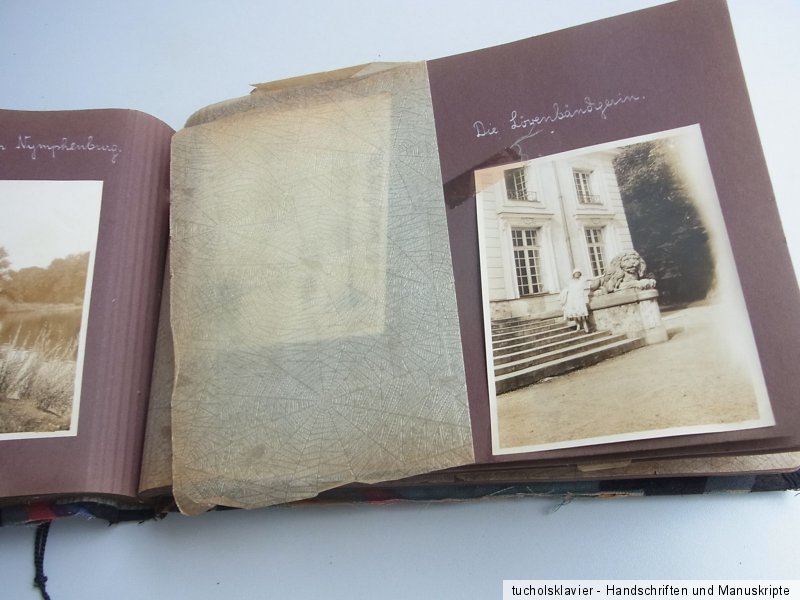

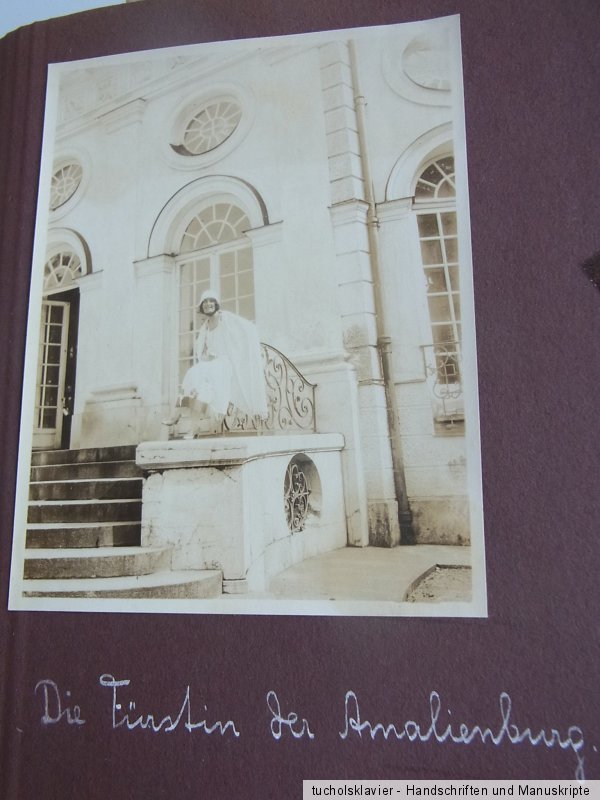

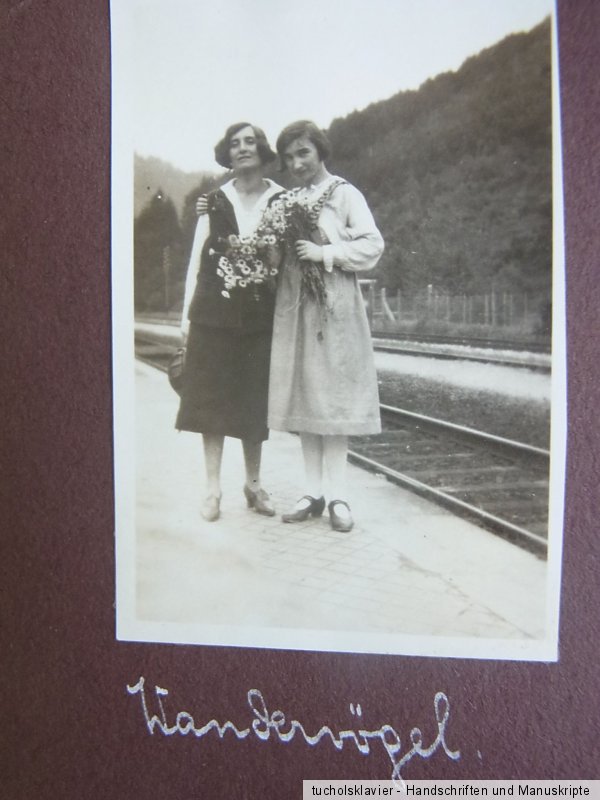

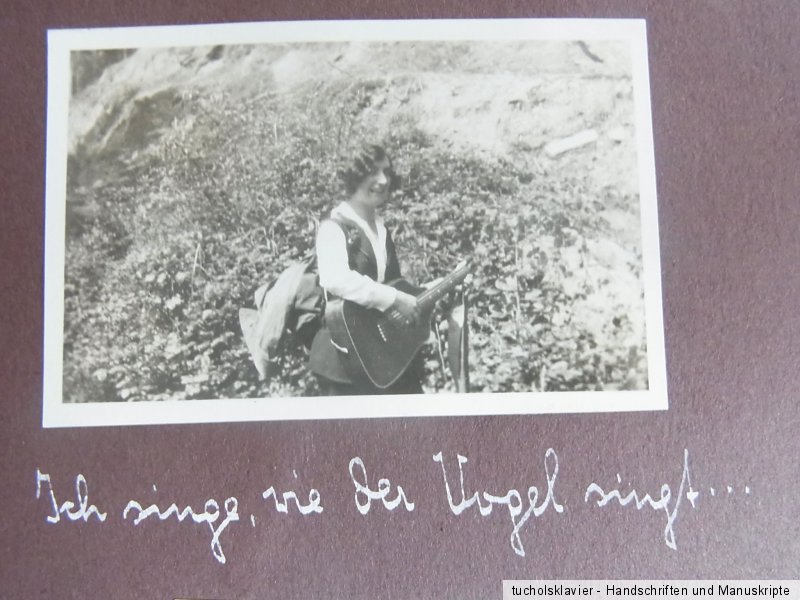

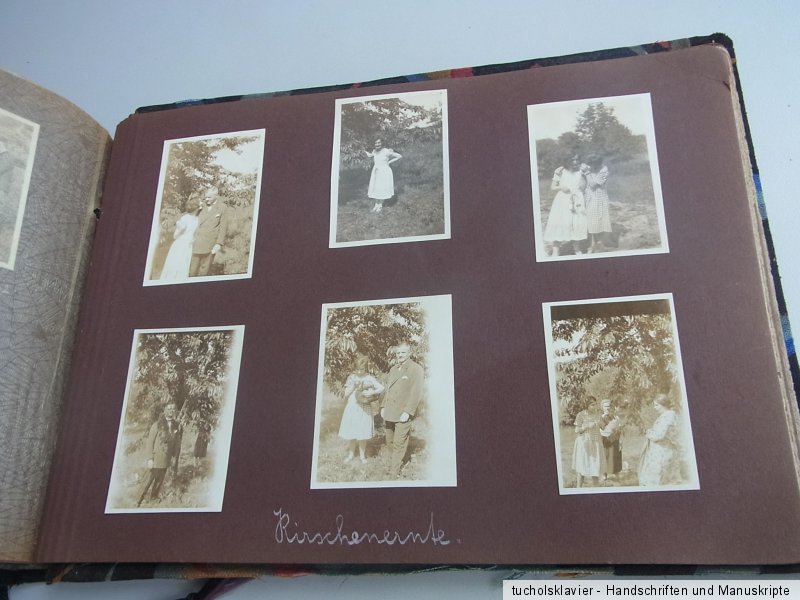

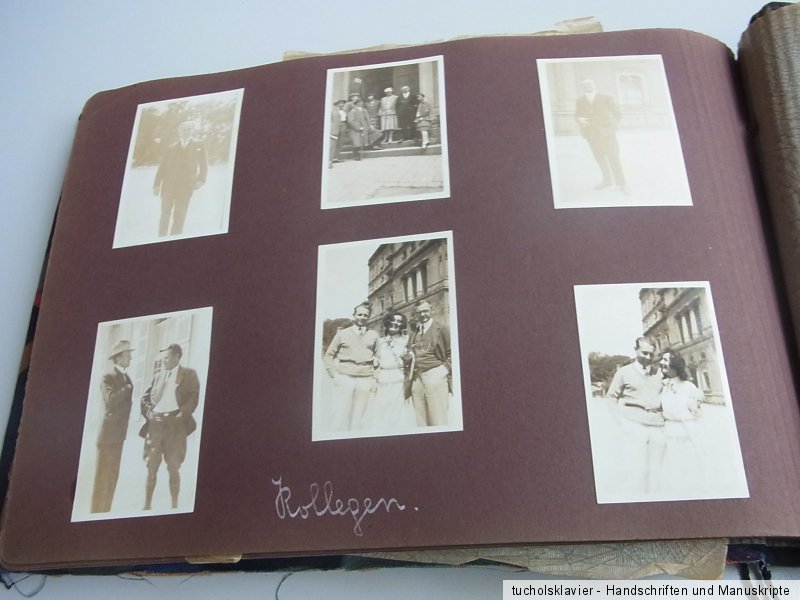

Many photos with captions on the backing cardboard.

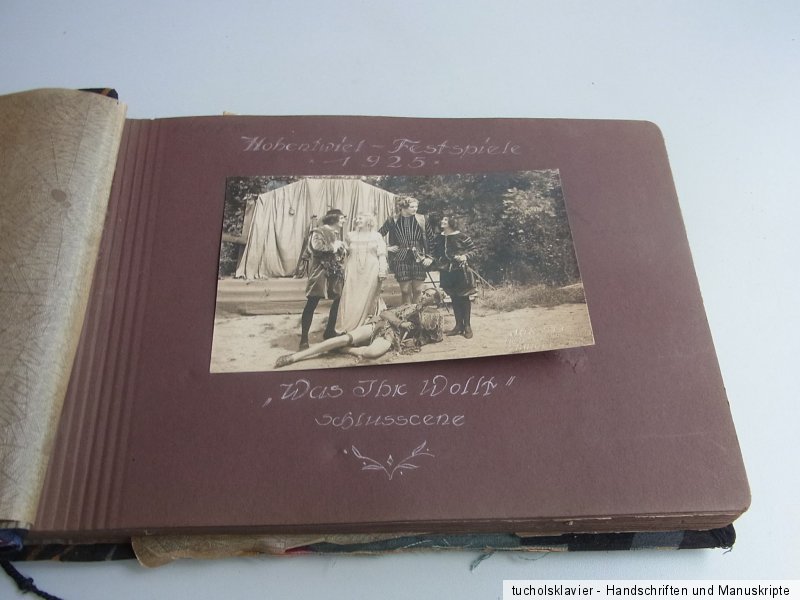

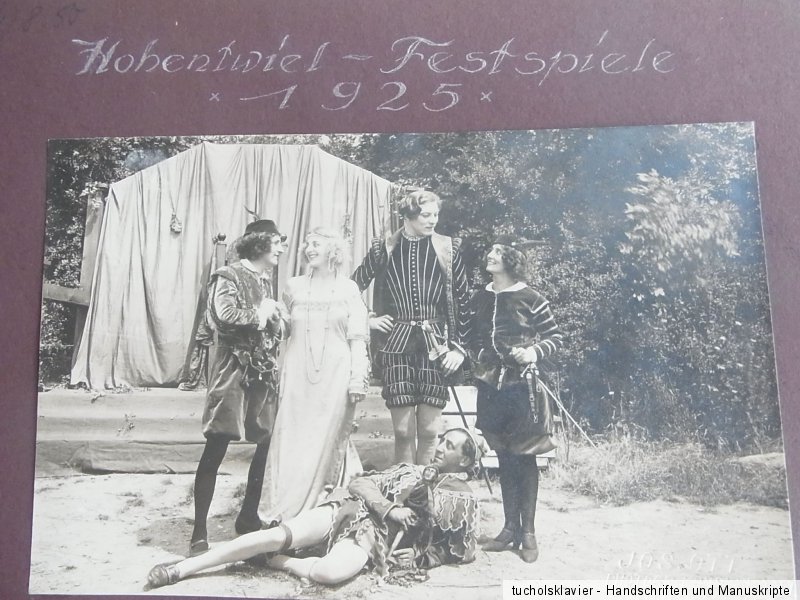

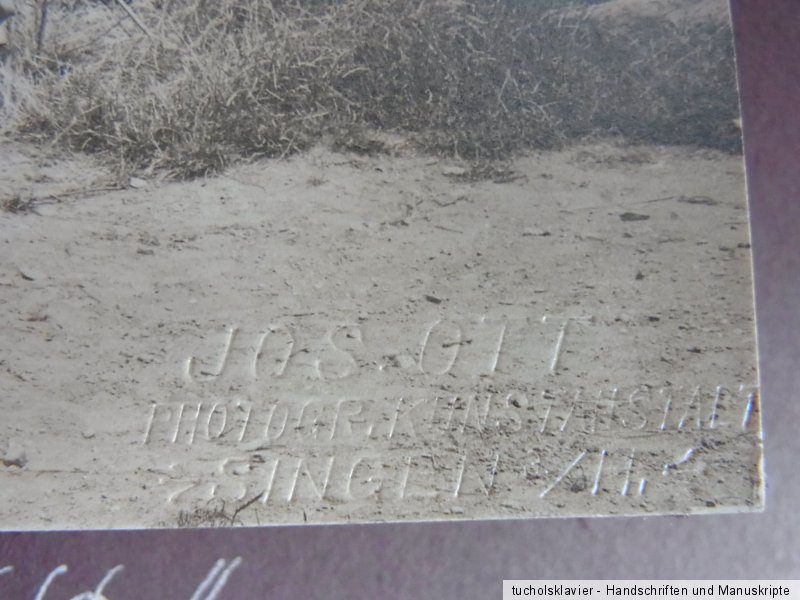

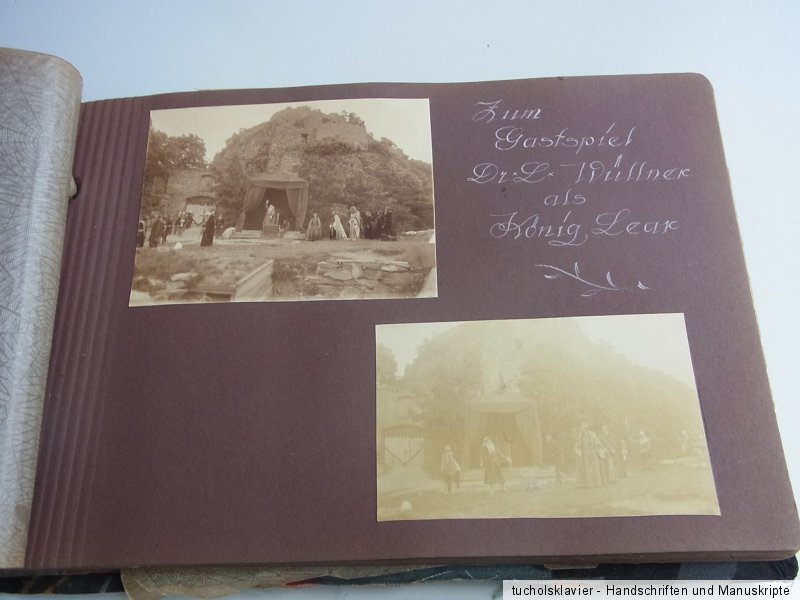

Starting with scenes of the "Hohentwiel Festival 1925" (Plays: “What you want” and “Hamlet” with Robert Bürkner); into the. 12 photos, including with Herma Clement.

Other categories:

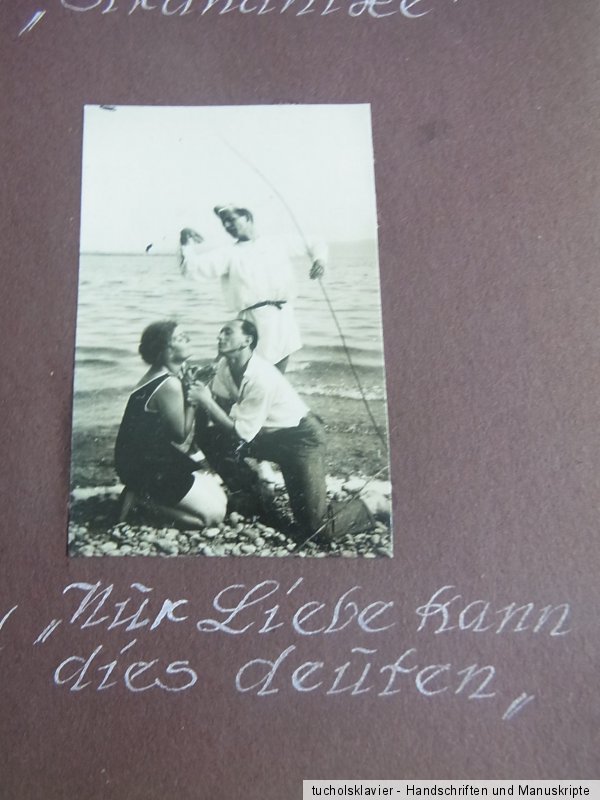

-At Lake Constance (including a scene with Willi Rose and Herma Clement)

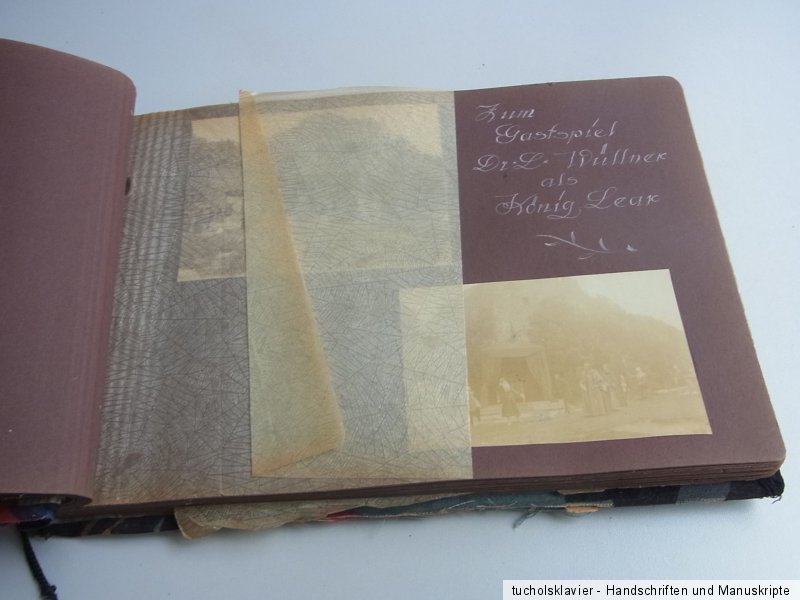

-Singing July 1925, for the guest performance of Dr. L. Wüllner as King Lear (photo of a drawing by Ludwig Wüllner, then two scenes from the open-air theater with Wüllner)

-In Zell am See, August 1925 (excursion)

-Madea: Hohentwiel Festival 1924 (3 photos, two of them with open-air theater scenes; actors & actresses: crutches, Neuhaus, Clement, Ottzen)

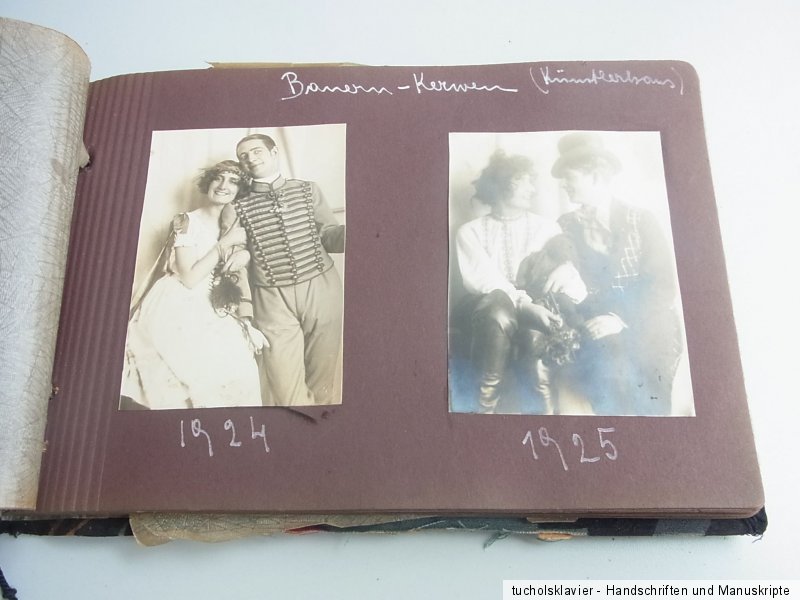

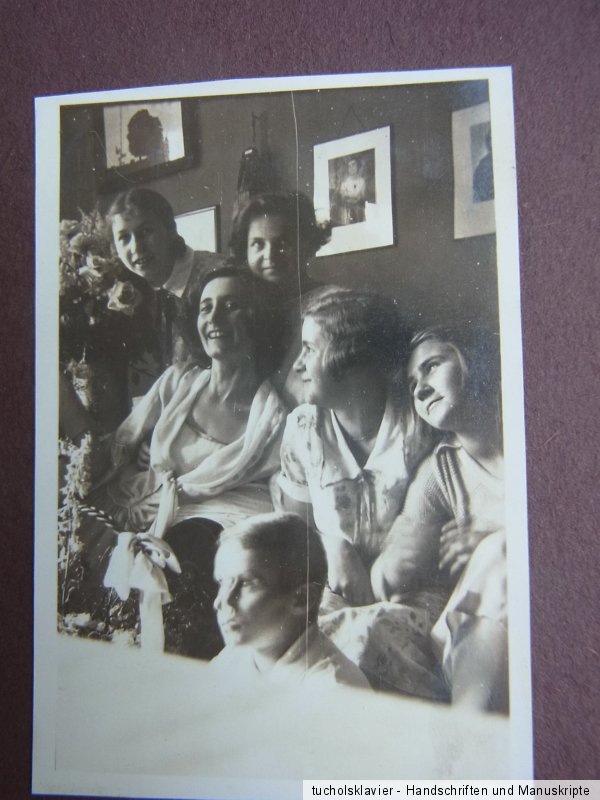

-Bauern-Kerwen (artist's house): 2 beautiful actor photos from 1924 & 1925

-Singing at Hohentwiel

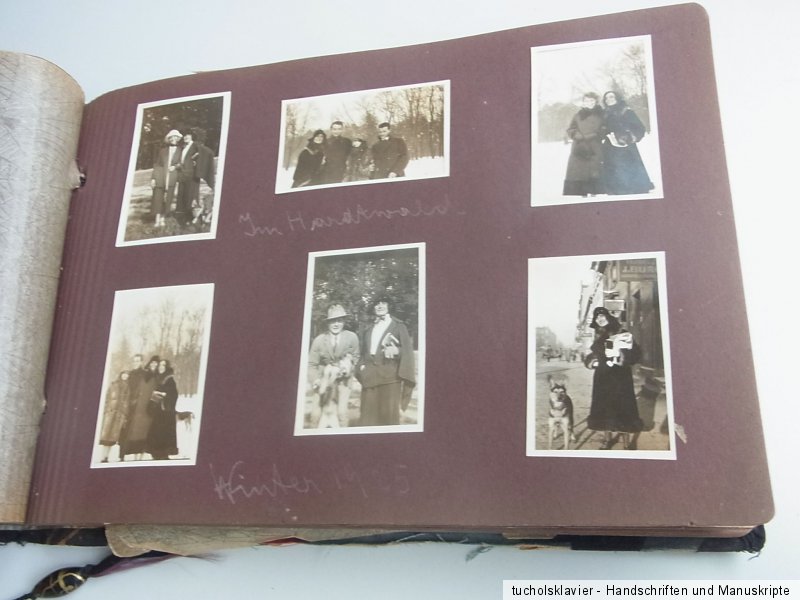

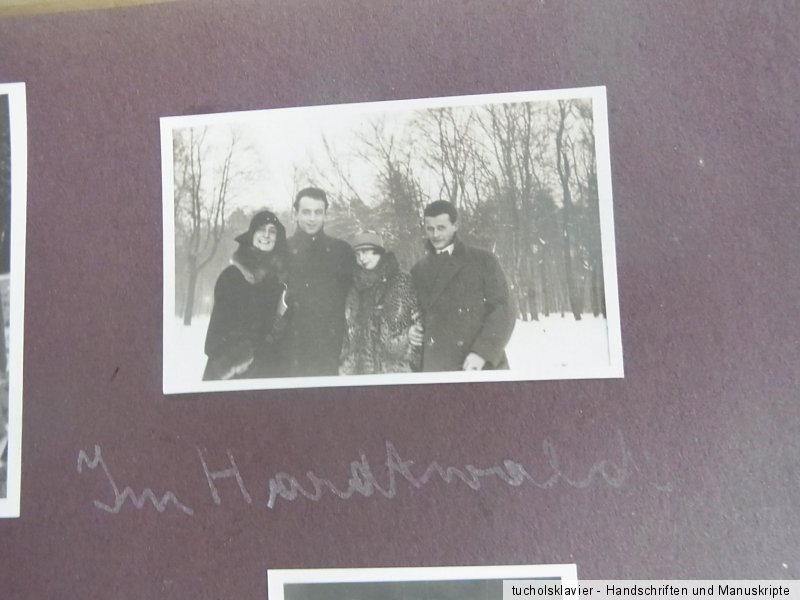

-in Hardtwaldt, winter 1925

-Rosario in Nyphenburg

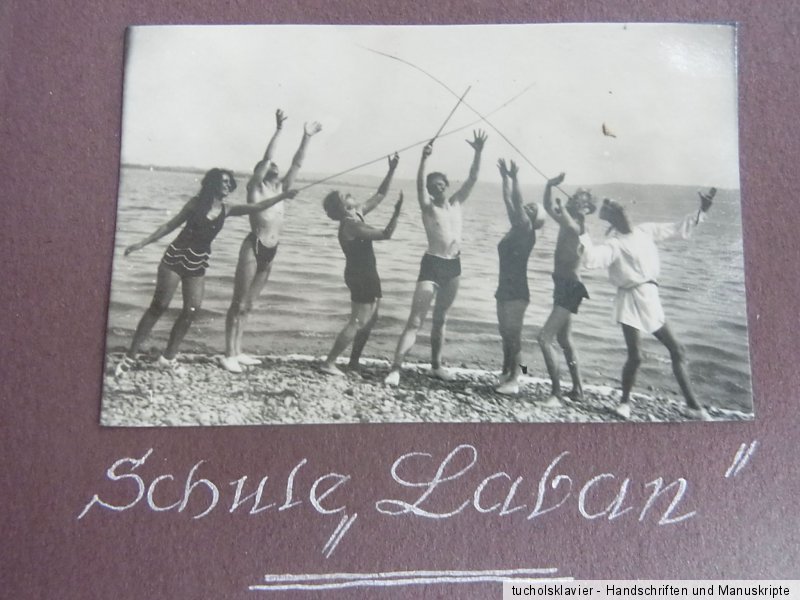

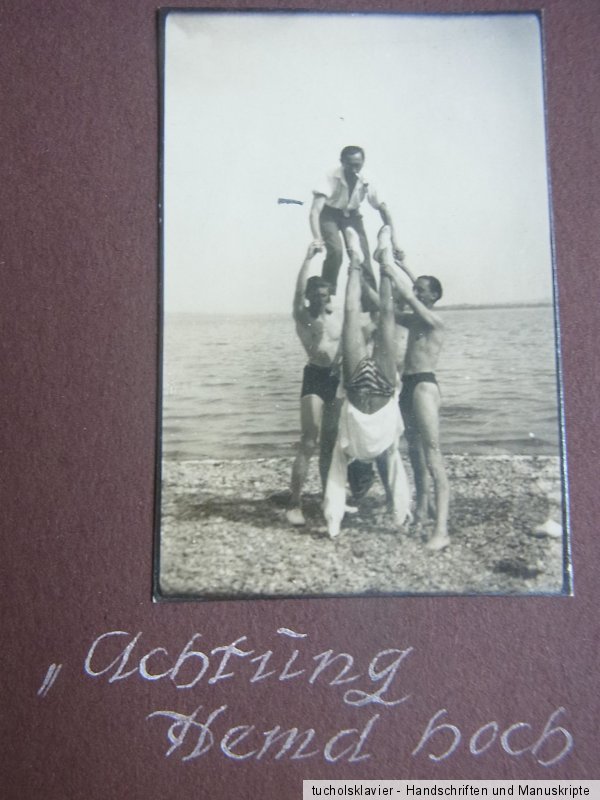

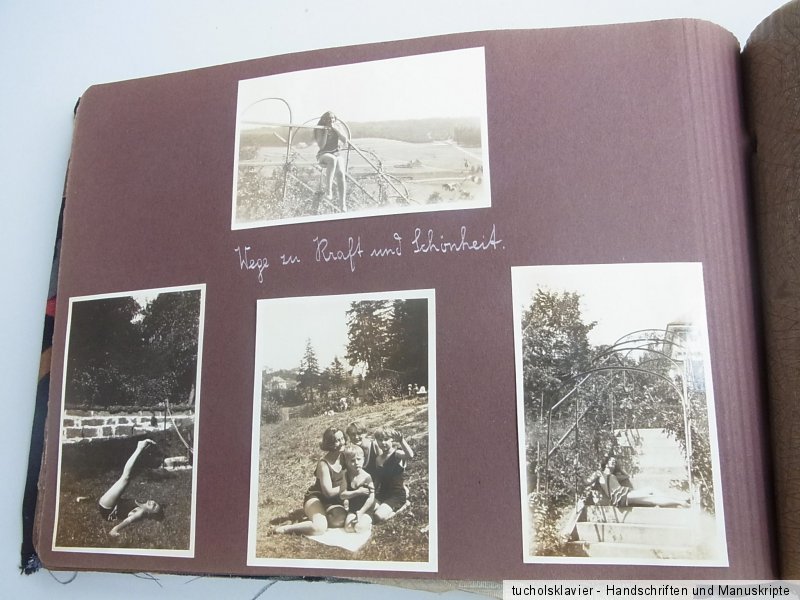

-Paths to strength and beauty (outdoor gymnastics)

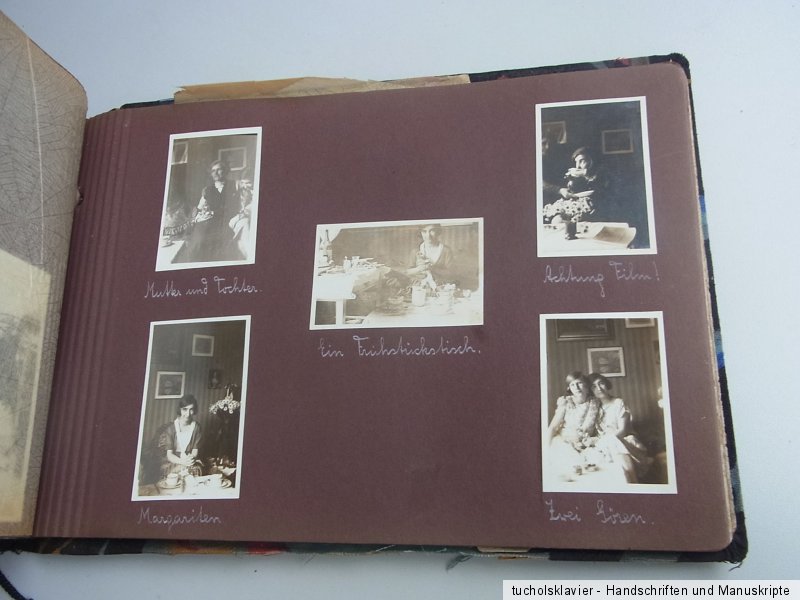

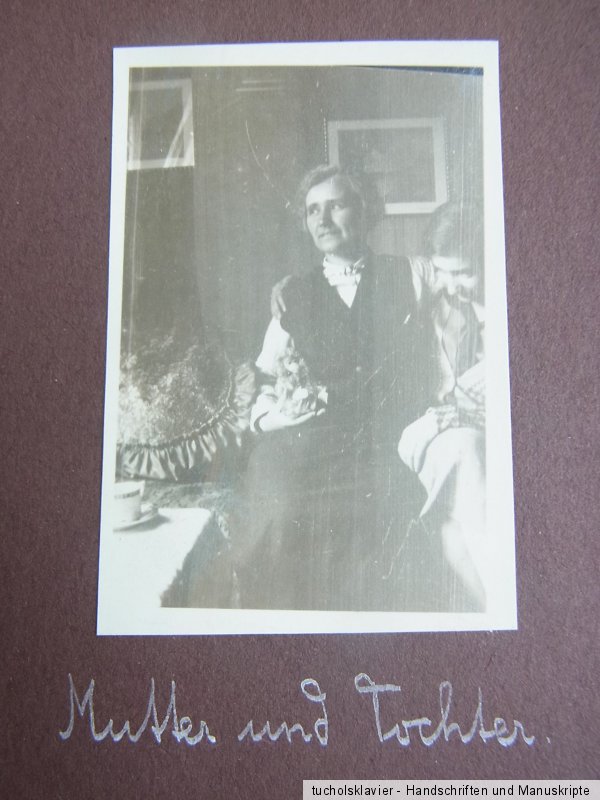

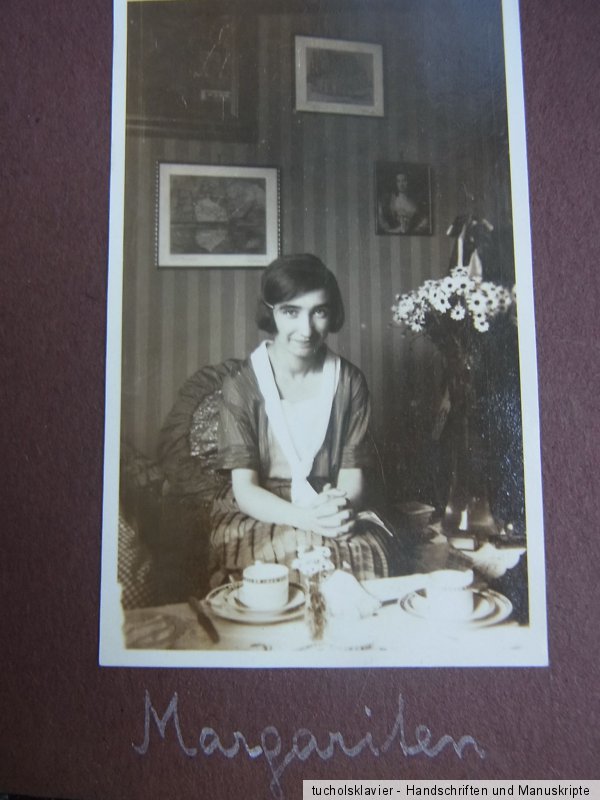

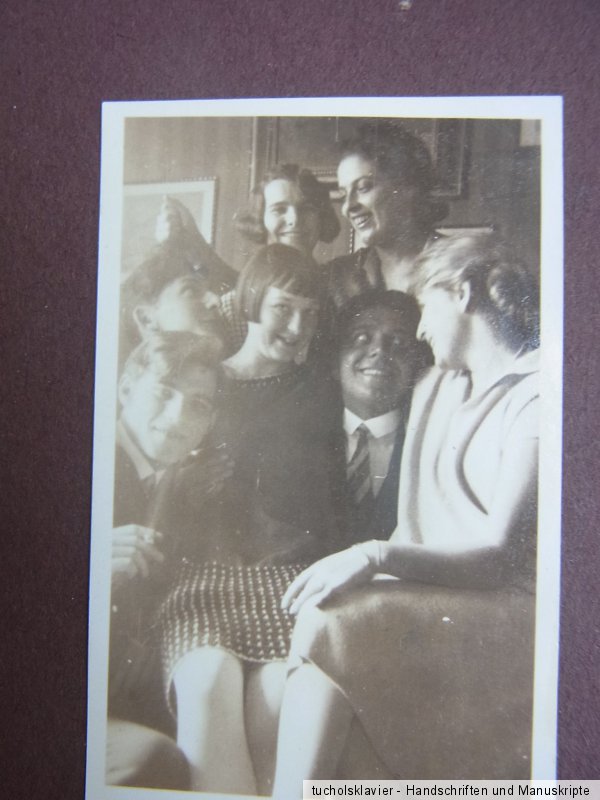

-several interior shots of the family (title, among others: "A Sunday morning at Clements")

-Cherry harvest

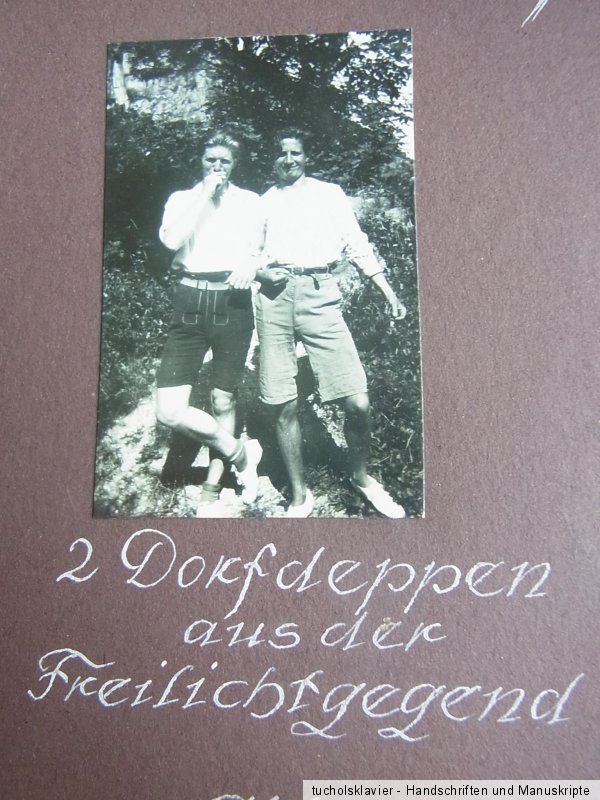

-Colleagues

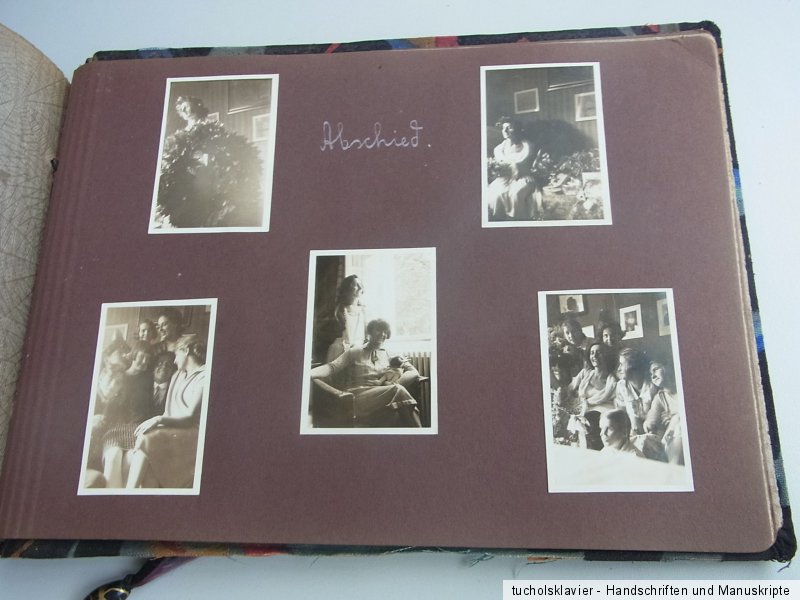

-Farewell

-From the family...

Format: 26.5x18.7x3cm; Weight: 584g

Condition: Avant-garde fabric binding damaged. Cord binding loosened, inside very good (only the glassine protective sheets are often bent or damaged; some photos are blurry). Please also note the pictures at the end of the item description!

Pictures

TRIXUM: Mobile-optimized auction templates and image hosting

About the Hohentwiel Festival, Robert Bürkner, Herma Clement, Willi Rose, and Ludwig Wüllner (source: wikipedia):

The city wanted to sing as early as 1900 Hohentwiel Festival justify. For this purpose, a festival hall was built under the Hohentwiel, where two festivals took place in 1906 and 1907. However, in subsequent years the project proved to be a failure and the hall was demolished in 1918. After the First World War, the festival idea was revived. On a weekend in August 1921, the festival took place again, this time directly on them the courtyard of the Herzogsburg. 1922 This became the folk festival, which ran for six weeks. The location of the performances was the Charles Bastion, with the Lower and Upper Castles as a “natural” backdrop. With varying financial success, the festival continued annually until the global economic crisis in 1929.

Carl Ernst Otto Robert Bürkner (* 12. July 1887 in Göttingen; † 19. August 1962 in Augsburg) was a German actor, theater director, theater director, playwright and writer.

Life

Family: Bürkner's father was the university professor Kurd Bürkner, specialist in ear medicine and founder of the ENT clinicnic in Göttingen. His grandfather was the Dresden wood carver and engraver Professor at the Art Academy Hugo Bürkner. His brother was the successful German rider, 18-time German dressage champion, member of the German team at the first Olympic Equestrian Games in 1912 (silver medal in the team) in Stockholm and “inventor” of the German school quadrille Felix Bürkner. His great-nephew Moritz Bürkner also became an actor.

Training and first jobs: After high school, Bürkner initially completed university studies (two semesters). He then began his career as a theater actor in 1906 (at the age of 19). The first stops were Bremen, Stettin, Basel and the National Theater Mannheim, where he mostly played the role of the youthful hero and lover. As a “first hero” and director, he then worked as a state actor at the Karlsruhe State Theater and the Altona City Theater. From 1929 to 1934 he moved to the city theater in Frankfurt (Oder) as director. After another 10 years as director in Lübeck, he moved to Berlin in 1943 as a character player at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm and the Tribüne.

Theater director in Lübeck

The central significance of this phase of life: Robert Bürkner worked as a theater director in Lübeck from 1934 to 1943. This phase of his life represented the highlight of his career. After all, when he was appointed to this position in 1934, he had already been working in the theater department for 28 years. The five years as director in Frankfurt/Oder (1929–1934) were outstanding in this phase of his life. For the actor, the engagements at the National Theater in Mannheim and the State Theater in Karlsruhe, which helped him earn the title of “State Actor,” were notable. But only once and for the first time in a medium-sized house, which was considered a springboard for further careers, was he able to shape the entire theater event in Lübeck. He knew that such a position had its difficulties and lived through them again: In principle, adapting to the Nazi system of rule was easier for him than the constant financial constraints, the unreasonable demands of Nazi organizations such as the DAF (German Labor Front), the claim against ambitious general music directors (GMDs) and, last but not least, by the conformist “bourgeois” circles of the time, who did not like him with his passion for acting and his talented wife, the actress Hansi Nassée. That was the decisive factor, while the discussion about his ancestry was thwarted by the Nazi leadership. As far as is known, Bürkner tried once again in 1945 to get an artistic director's chair at the almost intact Konstanz Theater, but did not succeed. So he remained true to his acting career for at least another 19 years, supplemented by tasks in film, television, radio and other media (e.g. as a speaker), in demand and appreciated until his death. After 1945, his wife continued to pursue her own career as an actress on other stages. Nevertheless, their time in Lübeck represented something unique for both of them, and as an active acting couple, they were a specialty in the theater environment, especially in their complementary acting. Even after 1945 they went on tours together.

Comrades and opponents: Robert Bürkner found ongoing support from Hans Wolff, the school and cultural organizer, as this top official was a music lover and Wagner admirer. Senator Ulrich Burgstaller remained a fleeting experience, but the administrative specialist Hans Böhmcker, who had also been Senator for Culture since 1935, was a difficult partner. As Finance Senator, he had to keep an eye on the overall budget. He treated Bürkner and his theater fairly, but strictly in line with the financial conditions. Wolff was his closest ally when it came to preventing the worst or obtaining grants from Berlin. Internally, Bürkner was fortunate to have a loyal and capable administrative director (since 1938) at his side, a party comrade with previous theater experience: Paul Gerhard Schwarz.[4] Creating this position turned out to be a win. In the musical field, Bürkner found GMD Heinz Dressel, who had to undergo an official investigation because of his rude treatment of his musicians. However, his excessive striving for the orchestra's top performance was positively offset by his openness to the musicians' social concerns.[5] Since 1942, Berthold Lehmann, also a highly talented, but at the same time power-conscious orchestra leader, followed in 1942, who knew how to make himself popular with the "Advisory Board for Art and Science" in Bürkner's now difficult situation. Soon there would be a choice between the two personalities. It was Bürkner who resigned and was accused, among other things, of neglecting the opera. Hans Wolff was unable to equalize.[6] Bürkner's successor Otto Kasten (1943–1945), also a party comrade, capable but with lung disease, was only able to last for about three years, with the theater operations being shut down in 1944.

Administration: The director had to generate a noticeable share of his own income despite a tight budget. The admission prices always played a role. At the same time, all sorts of social or party organizations, later the Wehrmacht for its wounded or those on home leave, benefited from the proceeds because they all claimed discounts for their clients, usually understandably so. The DAF (German Labor Front) organization KdF (NS Community Strength through Joy) behaved most unpleasantly. They wanted to create their own affordable subscription system for their employees “at any price” and to be recognized as an achievement of their organization. Stubborn battles had to be fought. They even refused to pay the artists' pension contributions as ordered by the Goebbels Ministry.

The financially tense situation also affected human resources. Except for the top positions, salaries and fees were significantly behind in a nationwide comparison with similar cities. The question of extending the engagement was a question of life for some artists. Among the artists, who frequently changed between seasons, there were numerous successful, critically-appreciated representatives who then, as usual, moved to a larger stage and continued their careers there.[9] There was also a local group of artists who remained solid, often “on the Lübeck boards” for years. Few others achieved the appreciation of the artistic director or Hans Wolff. Party affiliation played no role. This led to cases of bullying in the theater with ultimately negative outcomes. Not all of this was visible to the outside world; instead, the popular top talent was used to create the most “beautiful theater world” possible – as in Berlin, also on a local level.

The most difficult technical administrative measure was the theater renovation (1938–1941), for which the war economy took effect as early as 1938/39. In 1941, the Great House was open to play again until - in September 1944 - the nationwide theater closure took effect and the curtain came down everywhere.[11]

Schedule analysis: The programs[12] for which Bürkner was responsible consisted of musical theater with operas and operettas. When it came to classical operas, attention had to be paid to the stumbling block of Jewish librettists. The National Socialist Siegfried An Heißer made a name for himself by “de-Jewifying” Mozart’s libretti for “Don Giovanni” and “Cosi fan tutte”.[13] Richard Strauss, who was even president of the Reich Music Chamber (RMK) in 1934, was suspected by the modern masters because of Hugo von Hofmannsthal, but was reluctantly tolerated.[14] There were also opera composers who were close to the Nazis, such as Werner Egk, Ottmar Gerster and Max von Schillings.[15] You couldn't go wrong there. The field of operetta was even more difficult, and Jewish masters and librettists had made a significant contribution to the repertoire. Sound artists like Jacques Offenbach were banned from the programs, and Bürkner only had to rely on the known guidelines or, if necessary, Pay attention to the neighboring stages. Franz Lehár was controversial, but was played, as Hitler was a lover of his “Merry Widow”. Eduard Künneke and Paul Lincke were therefore in great demand. There were also more modern ones who were encouraged, but then again, like Robert Stolz, who was not a Jew, after a while they were suspected and could fall into disgrace.

In spoken theater, selected classics were adapted to Nazi philosophy. It was claimed that they had only been rediscovered. Authors like Christian Friedrich Grabbe were celebrated as forerunners of the Nazi movement.[17] The darker and more fateful, the better. Festivals and Thing Theater events were suitable for particularly Nazi pathos. The Low German Theater was able to continue to exist unhindered as down-to-earth and close to the people because most of the plays, being comedies, did not cause any offence. By retaining the important classics and modern playwrights (in selection), a canon of brilliant roles was retained to be embodied.[18] Of particular interest are the Nazi-affiliated dramas presented in Lübeck at the time, which were intended to place viewers in disturbing situations and show them how a National Socialist would have behaved in these situations. Heroes should be role models. Substantive teachings, even racism, hardly played a tangible role. It was about exciting, dramatic lessons. There were masters of this subject. Of those who played in Lübeck one could name: Gustav Frenssen, Sigmund Graff, Walther Heuer, Edgar Kahn. The authors also included Nazi officials such as Hans Johst, Franz Walther Ilges and Walter Erich Schäfer. The director could hardly make any mistakes because these authors were recognized, recommended and played. Her placement in Lübeck was the task.

The Lübeck “Advisory Board for Art and Science” also did not understand that during the war years, according to the wishes of the Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, primarily entertainment pieces should be offered. This was understandable given the tense situation for the population. If Bürkner took this into account, he was on the same course as the Reich government. He pointed out the hypocrisy of such accusations, because the “adjusted bourgeois” in the committee, who were hand-picked party supporters (even if not formally party members), did not attend “valuable events” such as a performance of George Frideric Handel’s “Xerxes” (1939). Such performances were poorly attended. Just an example of Bürkner's situation.[20] If you look at the numerous contemporary authors, librettists and composers of the works selected by Bürkner, you can see all shades of adaptation to the Nazi regime: convinced participation, opportunism, skillful tactics and inner emigration. In each case, whoever was going to be printed, performed or played had to make compromises. Anyone who sought prestige and fame clearly had to work for the regime.[21]

Bürkner's position in the Nazi era: Bürkner had been an SA troop leader since 1933 and had therefore committed himself to the “movement” very early on. But he only became a party member on January 1st. May 1937. His accession was not a formal requirement when he was appointed to Lübeck, but then it ultimately became inevitable. Bürkner was behind the system. According to the provisions of the Nuremberg Laws of 15. September 1935 (= 7. Reich Party Rally), Bürkner was a “Jewish half-breed” due to his Jewish grandmother and was considered a “quarter Jew,” according to the terminology of the time. This meant that you could remain employed as a public servant, but not be a civil servant. This did not result in any compelling change for Bürkner. However, since he held a prominent position and acted in the political sphere, his opponents tried to take up the issue of ancestry. In fact, on the 21st In February 1939 a decision was made by the party court that excluded the person who had only joined the party in 1937 from the party. (Bürkner joined after the Nuremberg Laws were passed in 1935.) But Bürkner wanted to stay in the party and initially ensured that his artistic directorship continued to be secured by Goebbels. But that could be revoked. Other higher Nazi representatives did not want to make a final decision and remained undecided. Ultimately, Hitler, “the Führer,” decided that Bürkner could remain in the party. That Hitler took part in theater issues - if necessary down to the local level - if necessary. also intervened, was not an isolated case. He was very well informed about the theater and concert industry. The Lübeck leadership had supported their director from the start. This meant that the opponents in the “Advisory Board for Art and Science” could no longer do anything against him with this issue.

What is interesting is that in his autobiography Alma Gomel (1949), Bürkner deals with his years in Lübeck, praises and honors Wolff and his administrative director Schwarz, but does not mention his political involvement at all. It is simply ignored.[23] It should be noted that Bürkner, like many others working in the artistic field, did not just join the party for formal reasons, but also shared the system's essential goals and worked for them. In this respect, the following quote clearly reflects this fact: “Allow us, dear Mr. Intendant, to express our heartfelt thanks to you today and in this way for your support of our difficult struggle to penetrate the German theaters with National Socialist ideas!”[24 ] Andrew G. Bonnell described the process at that time in 2008 as follows: “The Lübeck Theater was under the direction of a Robert Bürkner, a Nazi party member and SA officer, who apparently enjoyed the special favor of the Propaganda Ministry. Ironically, just three months after his theater celebrated Kristallnacht with the Merchant of Venice, he was expelled from the Nazi Party when it was discovered that he had a Jewish grandmother and it took a special exception from Goebbels to remain in his position ."[25] Günter Zschacke's verdict: "The Lübeck theater director survived admirably through the times..." can only be agreed with to a limited extent from a political perspective, as capable and in many respects remarkable as this actor and director otherwise was.[26] The fact that the National Socialist Bürkner was put in distress by the system he served, as well as being “Jewish-influenced,” as it was formulated at the time, is a result of the racism that formed the foundation of National Socialism. In this respect, Bürkner must also be granted the tragedy that presented some other artists at the time, who were perhaps married to a Jew, with difficult decisions of conscience.

After the war: After the war, Bürkner's stops included the venues in Bonn, Oldenburg and the Augsburg City Theater. In his last years he undertook numerous guest tours with his wife, the actress Hansi Nassée, who was, among other things, engaged at the Vienna Kammerspiele.[28]

Leading and supporting roles: Bürkner's leading stage roles, primarily in Lübeck, were: Hamlet (title role, Shakespeare), King Lear (title role, Shakespeare), Brutus (Julius Caesar, Shakespeare); President of Walter (Schiller, Cabal and Love), King Philipp (Schiller, Don Carlos), Karl Moor (Schiller, The Robbers) Wallenstein (Schiller, work of the same name); Egmont (title role, Goethe), Mephisto (Goethe, Faust); village judge Adam (Kleist, The Broken Jug); Herod (title role in Hebbel's Herod and Mariamne), Kandaules (Gyges and his Ring, Hebbel); Orestes (as part of the Oresteia, Aeschylus). – Baron von Wehrhahn (The Biberpelz, G. Hauptmann); Peer Gynt (Ibsen, work of the same name). – In Nazi works or pieces: Colonel Bauer (The 18th October 1813, shepherd); Casanova (Chevalier von Seingalt, Casanova returns the favor, Ilges). – In entertainment pieces: Baron Trenck der Pandur (title role, Groh), Bolingbroke (Scribe, A Glass of Water), Harald Haprecht (Bürkner, The New Papa). – The artist couple played together in: The Model Husband (Hopwood): B. as Billie Barlett, his wife was Wheeler's wife), Dr. med. Job Prätorius and at the same time Sherlock Holmes, Hansi Nassée as a wife (the play of the same name by Götz), as a married couple in: All right, let's get divorced (Sardou), Charles III. and Anna of Austria (in the play of the same name, Rößner.

In the 1940s he appeared in supporting roles in several feature films. From the end of the 1950s he also appeared in a number of television productions, such as in 1959 in the sixth part of the street sweeper So Far Your Feet Will Carry as Erich Baudrexel, the uncle of Clemens Forell, who later returned from the war. The following year he played the tutor Dr. Theodor Förster.

Stage plays and adaptations: The countless stage adaptations of German and European fairy tales that Bürkner performed in a simple, poetic and humorous way are known to this day. His media pedagogical approach was remarkable. The author wanted to "take a young viewer with him" and involve him in the action as quickly as possible. For this purpose, a journeyman appeared right at the beginning of "Little Red Riding Hood" who greeted and addressed the children. Then there was the postilion (or the fairy-tale postilion) with the same function, but also the "travelling journeyman". These characters also appeared at prominent points in the play and questioned or deepened the course of the fairy tale for the children. Cruel situations were defused in this way. Questions to be answered were also addressed to the young audience. In this way, the audience was not only “presented” with something, but was also given a feeling of participation. On the other hand, the great success of the Bürkner fairy tales was ensured by the fact that they were designed in such a way that they could also be performed in other venues, such as a school auditorium, without special stage technology.[30] Bürkner's repertoire included virtually all of the Brothers Grimm's popular fairy tales. His first works include Little Red Riding Hood (1919) and Sleeping Beauty (1920), and his later adaptations include: B. The Goose Shepherdess at the Well (1947). His adaptations of fairy tales include:

Cinderella (in Lübeck 1940/41)

The valiant dressmaker

The Frog Prince or Iron Heinrich (in Lübeck 1938/39)

Puss in Boots

The goose shepherdess at the well

the princess and the Pea

sleeping Beauty

Frau Holle or Goldmarie and Pechmarie

Ilsebill's Christmas Adventure (in Lübeck 1935/36)

Little Red Riding Hood (in Lübeck 1934/35 and 1942/43)

Rumpelstiltskin

Snow White and Rose Red

Little table, cover yourself, donkey, stretch yourself, club, out of the sack!

gnome nose

Especially in his early years, he also wrote a few comedies, such as The Shot in the Mirror and The New Papa (both 1919). He later also wrote the novels The Trap (1940), A Harmless Person (1941) and The Uncanny Fire (1947), which describes the life of the actor Ludwig Devrient.

The Schleswig-Holstein State Theater staged many of his fairy tale adaptations:

1949/50: Little table set yourself

1950/51: Fairy tale about the fisherman and his wife

1951/52: Snow White and Rose Red

1952/53: The brave little tailor

1954/55: Frog Prince

1955/56: Mrs. Holle

Death and burial

At 19. Bürkner, the grand seigneur of the German theater, died in Augsburg in August 1962. The funeral took place on the 21st. August in the West Cemetery there, field 65 row path number 311.

Filmography

1942: Rembrandt (Notary Wilkens) – Director: Hans Steinhoff, with Ewald Balser, Hertha Feiler, Gisela Uhlen

1942: Dr. Crippen on Board (Criminal Director Nicolin) – Director: Erich Engels, with Rudolf Fernau, René Deltgen, Anja Elkoff

1943: The Golden Spider (Dr. Eberding from Kattenbeck-Werke) – directed by Erich Engels, with Otto Fee, Erich Dunskus, Jutta Freybe

1945: Symphony of Three Hearts (alternatively: soloist Anna Alt) - directed by Werner Klingler with Anneliese Uhlig, Will Quadflieg, Emil Lohkamp

1959: As Far as Your Feet Can Carry (Erich Baudrexel) - television multi-part series - directed by Fritz Umgelter, with Heinz Weiss, Wolfgang Büttner, Hans Epskamp

1960: On the green beach of the Spree, 3. Part: Prussian Fairy Tale (Dr. Theodor Förster) - television multi-part - directed by Fritz Umgelter, with Elisabeth Müller, Peter Pasetti, Peter Thom

1960: Under the Milk Forest by Dylan Thomas - production: Karl Bauer, with Gerd Mayen, Walter Guberth, Klaus Barner (recording of a broadcast from the Augsburg City Theater)

1960: The Lady in the Black Robe (Lawyer Clive) - TV film - Director: Peter Zadek, with Margot Trooger, Harald Leipnitz, Franz Schafheitlin

1962: Becket or The Honor of God (The Archbishop) - TV film - Director: Rainer Wolffhardt, with Heinz Baumann, Heinrich Schweiger, Heinrich Cornway

1962: Paper Mill (Decaplain) - TV film - Director: Hans-Dieter Schwarze, with Grit Boettcher, Viktor de Kowa, Erik Schumann

Herma Clement (*28. January 1898; † 6. November 1973 in Berlin[1]) was a German film and stage actress and acting teacher.

Life: The former director of the Weimar National Theater, Franz Ulbrich, brought Herma Clement with him along with Emmy Sonnemann (who later became Hermann Göring's wife) when he moved to the Berlin State Theater in 1933, the year the National Socialists came to power. Her husband Karl Haubenreißer (1903–1945), also an actor and mostly used as a “youthful hero”, was appointed in 1933 in place of the fired Hans Otto as chairman of the local group of the German Theater Association (GDBA), which was now aligned with the “Fachschaft”. During the Nazi era, Clement was a speech instructor for Gustaf Gründgens' students at the (privately organized) State Drama School in Berlin (the forerunner of today's Academy of Dramatic Arts). Herma Clement was close friends with Emmy Sonnemann, and they both starred together in the same films several times.

After the end of the war until (at least) the 1950s, Herma Clement gave private acting lessons.

actress

Stage roles (selection)

1933: Peer Gynt by Henrik Ibsen, directed by Richard Salzmann, German National Theater Weimar, premiere: 25. March 1933. Role: “The Green” (woman dressed in green). Karl Haubenreißer played the main role of Peer Gynt.

1938: Peer Gynt, adapted by Dietrich Eckart, directed by Erich Ziegel, Staats-Theater Berlin – Schauspielhaus am Gendarmenmarkt, premiere: 24. May 1938. Role: Woman dressed in green. In the play, Karl Haubenreißer played the role of Boyg.

Film rolls (selection)

1920: The Shawl of Empress Catherine II (director: Karl Halden): supporting role

1931/1932: Goethe lives...! (Director: Eberhard Frowein): Supporting role (Emmy Sonnemann also starred in this film)

1934: Wilhelm Tell (Director: Heinz Paul): Armgard (More about this female role in the article about Schiller's Wilhelm Tell)

Drama school

Known students (selection)

Horst Bollmann, Renate Danz, Gardy Granass, Brigitte Grothum, Jennifer Minetti, Witta Pohl (1955), Thomas Stroux, Suzanne Thommen, Giselle Vesco, Bernhard Wicki (Clement denounced Bernhard Wicki to her friend Emmy Göring, which led to Wicki's arrest by the SS and his temporary internment in a concentration camp), Jürgen Wölffer

Willy Rose, actually Wilhelm Bernhard Max Rose (* 4. February 1902 in Berlin; † 16. June 1978 ibid) was a German stage and film actor.

Life: Willi Rose's father Bernhard Rose (1865–1927) had at the end of the 19th century. In the 19th century, with the takeover of a restaurant, the Rose Theater was also taken over, which developed into a kind of popular theater. His children Hans (1893–1980), Paul (1900–1973, actor and theater director) and Willi Rose took over the management and also acted on stage. At the age of 34, Willi Rose left the fraternal community and went his own way.

Willi Rose died in Berlin in 1978 at the age of 76. His urn grave is in the state-owned Heerstraße cemetery in Berlin-Westend (grave location: II-Ur 10-1-22).[1] He rests there next to his wife Ilse Rose-Vollborn (1911–1974).

At Bolivarallee 17 in Berlin-Westend, where Willi Rose lived from 1950 until his death, a memorial plaque commemorates the popular actor. It was donated by the Berlin Taxi Guild and the district office.

Profession: Willi Rose received one of his first small film roles during the Nazi era in the film Allotria in 1936. He first became known to a larger audience through roles in Die Götter Jette (1937), Urlaub auf Ehrenwort (1938), Alarm auf Station III (1939) and especially in the world-famous Circus Renz (1943). At the end of the war he was added to the God-Given list.

After the war, Willi Rose played many memorable supporting roles, including Wozzeck, a DEFA production from 1947, The Captain of Köpenick (1956), The Iron Gustav and Taiga (both 1958), but also leading roles (At Pfeiffer's Ball, 1966) . With the spread of television, Willi Rose also played there in several series and television plays and was also seen here several times in leading roles (Der Biberpelz, Jedermanstraße 11).[3][4] His congenial portrayal of "Engelke" alongside Arno Assmann in the three-part television series Der Stechlin (1975) is unforgettable.

Records: Since he also starred in operettas, Willi Rose has made numerous recordings with hits and popular songs such as: Doll, you are the star of my eyes, We drink our grandma's little house, Bananas of all things or Come to my love bower.

Films (selection)

1936: Allotria

1937: Patriots

1938: The 4 journeymen

1938: Pour le Merite

1938: Vacation on honor

1939: Legion Condor

1939: Alarm on Station III

1939: Sensational Casilla trial

1941: U-boats westward!

1941: About everything in the world

1941: …rides for Germany

1941: Secret file WB 1

1942: Front Theater

1942: Five thousand marks reward

1943: Renz Circus

1943: Big City Melody

1945: The silent guest

1945: Shiva and the Gallows Flower (unfinished)

1947: And one day we will meet again...

1947: Wozzeck

1948: And 48 again

1949: The colorful checkers

1949: After rain, sun shines

1950: 12 a.m. 15 room 9

1950: The Woman from Last Night

1950: The Rabanser case

1951: The Wives of Mr. S.

1951: Torreani

1951: Queen of a Night

1952: Three days of fear

1954: Your big test

1954: Fairground of Love

1954: Rape of the Sabine Women

1955: My children and me

1955: Heroism after closing time

1955: Sleeping Bag Company

1955: Three days of middle arrest

1956: At your command, Ms. Sergeant

1956: A girl from Flanders

1956: The Captain of Köpenick

1956: II-A in Berlin

1957: The world is beautiful

1957: Made in Germany – A life for Zeiss

1957: The Girl Without Pajamas

1957: The big opportunity

1958: Taiga

1958: The Man Who Couldn't Say No

1958: The Iron Gustav

1958: Piefke, the terror of the company

1958: When Conny and Peter

1959: The Fiery Red Baroness

1959: That's no way to catch a man

1960: Freddy and the Melody of the Night

1960: We cellar children

1960: Mrs. Irene Besser

1960: The juvenile judge