Documents Otto von LINSTOW 1884: GENEALOGY, LIVINGSTONE

Description

– Wmore See pictures below! –

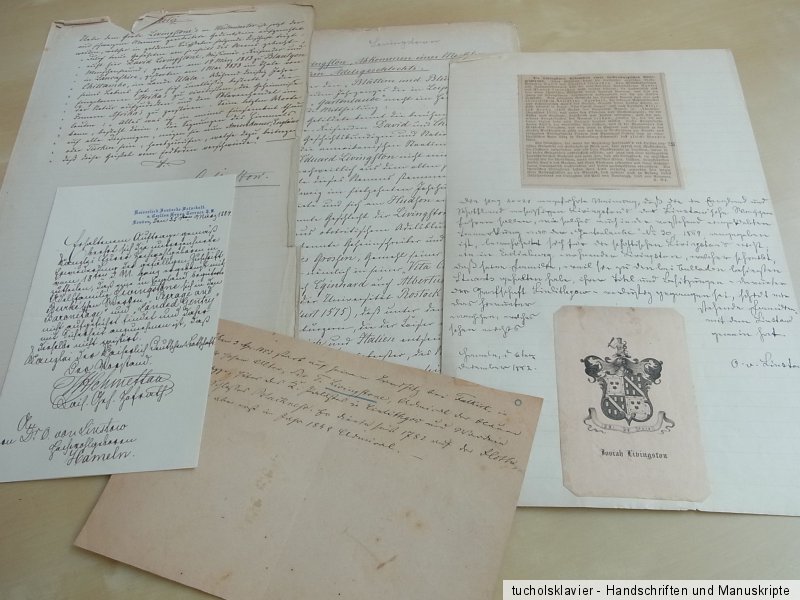

They bid on Documents with genealogical research of Medical officers and helminthologists Otto von Linstow (1842-1916).

This pursues the thesis, the Scottish Livingstone family (of the missionary and African researcher David Livingstone) comes from his family and therefore has a modified form of their name. -- This assumption turns out to be true incorrect.

Available:

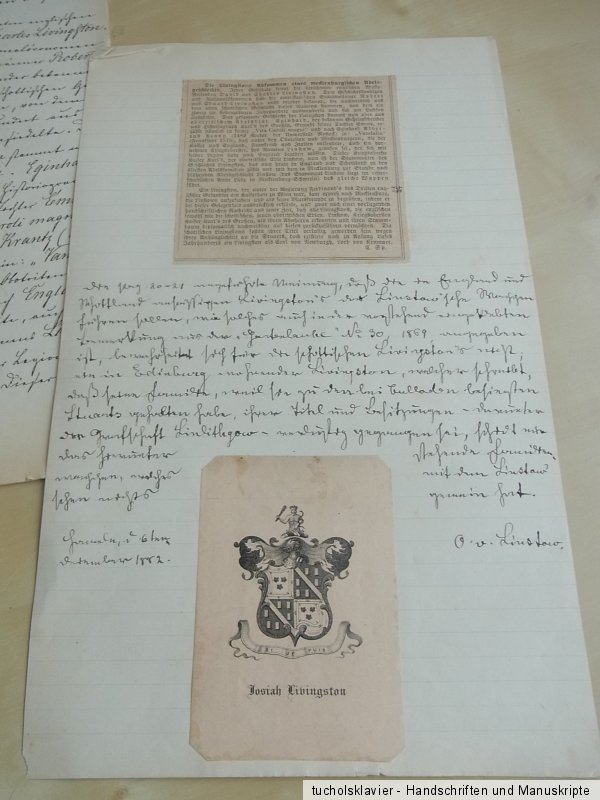

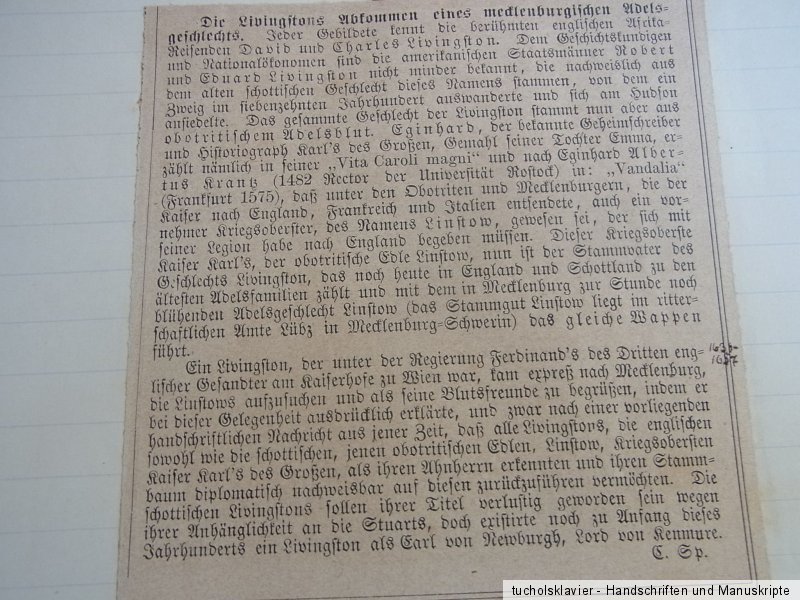

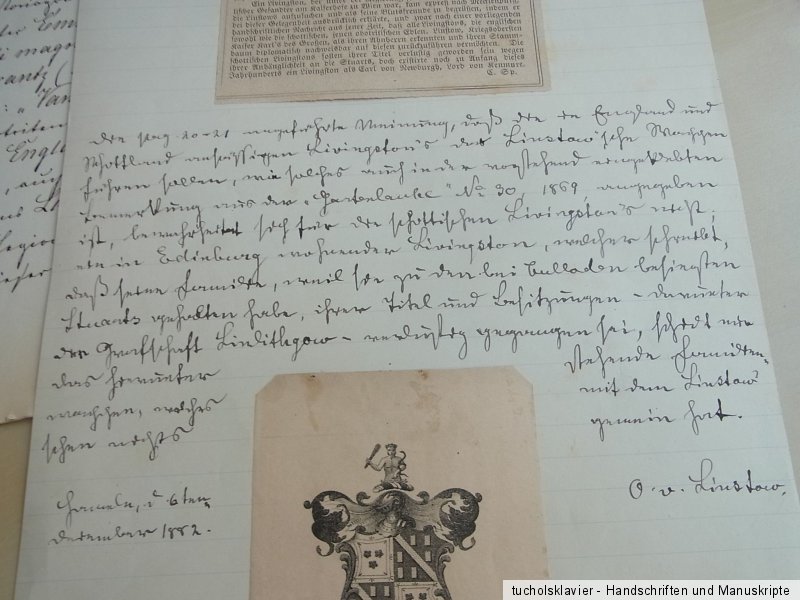

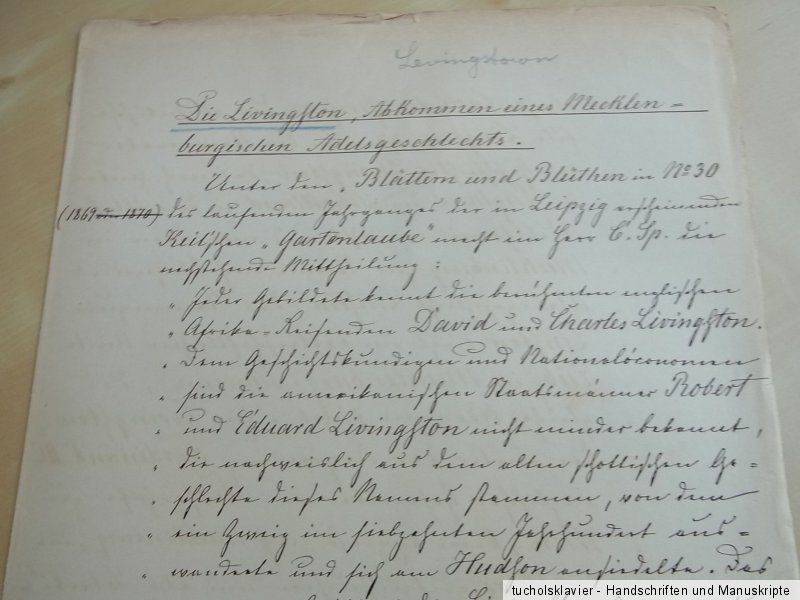

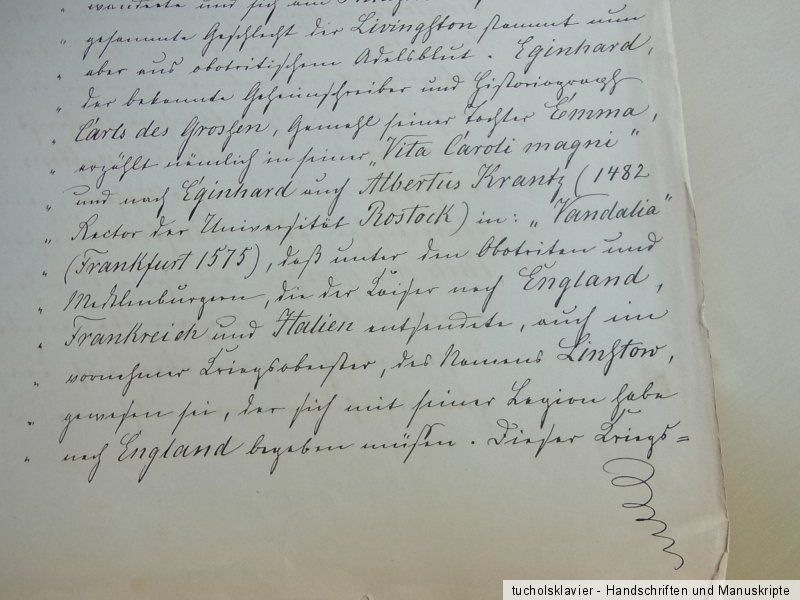

1.) Large sheet with an excerpt from the magazine "Gartenlaube", No. 30 (1869): "The Livingstone Agreements of a Mecklenburg Noble Family", in which this thesis is put forward, with a printed coat of arms by Josiah Livingston and handwritten notes by Otto von Linstow, dated Hameln, 6. December 1882.

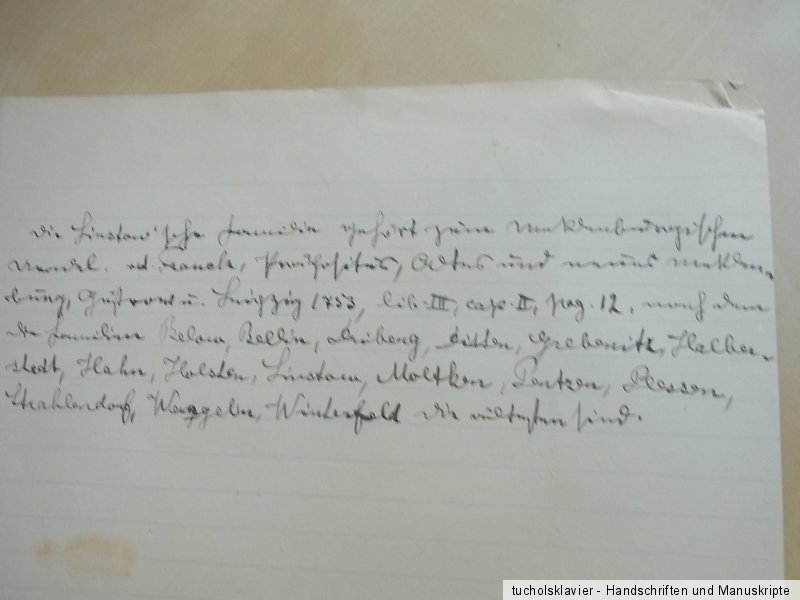

On the back there are a few lines about the von Linstow family.

2.) Small older sheet with a short note about the admiral Sir Thomas Livingstone / Livingston of Bedlormie & Westquarter, 7th Bart (1769-1853).

3.) Handwritten copy of the gazebo article and the short article about Thomas Livinston(e).

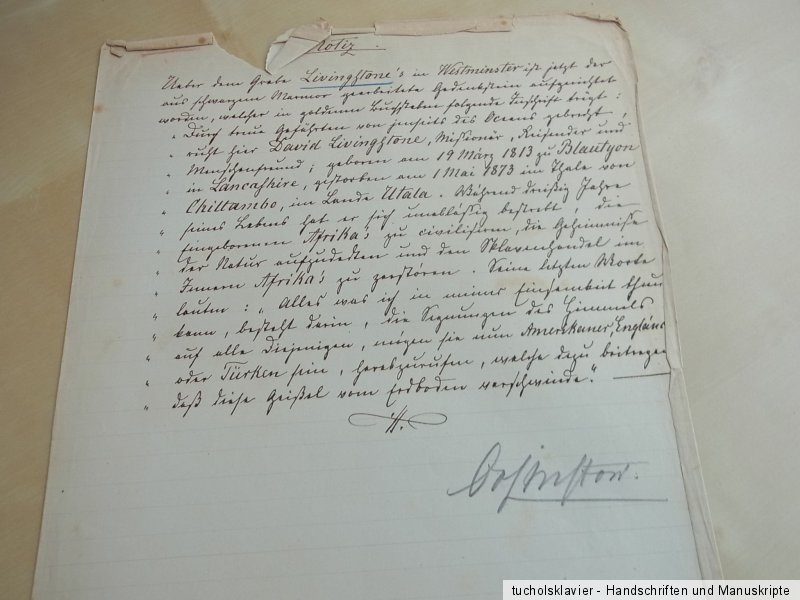

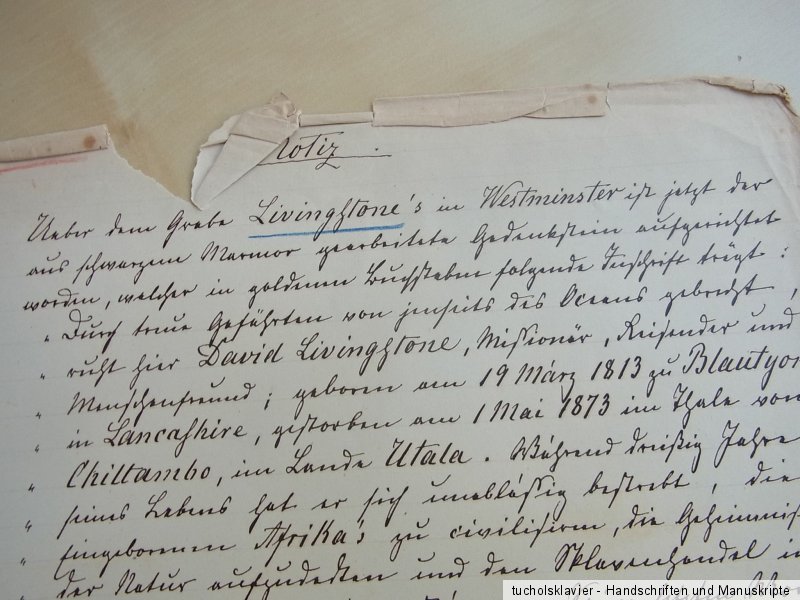

4.) Handwritten translation of the inscription in the memorial stone on the grave of David Livingstone, written by Otto von Linstow.

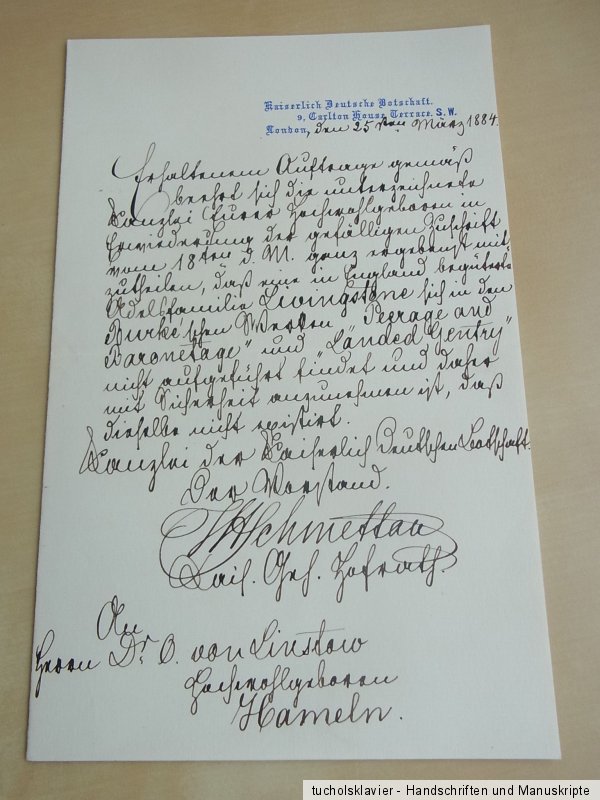

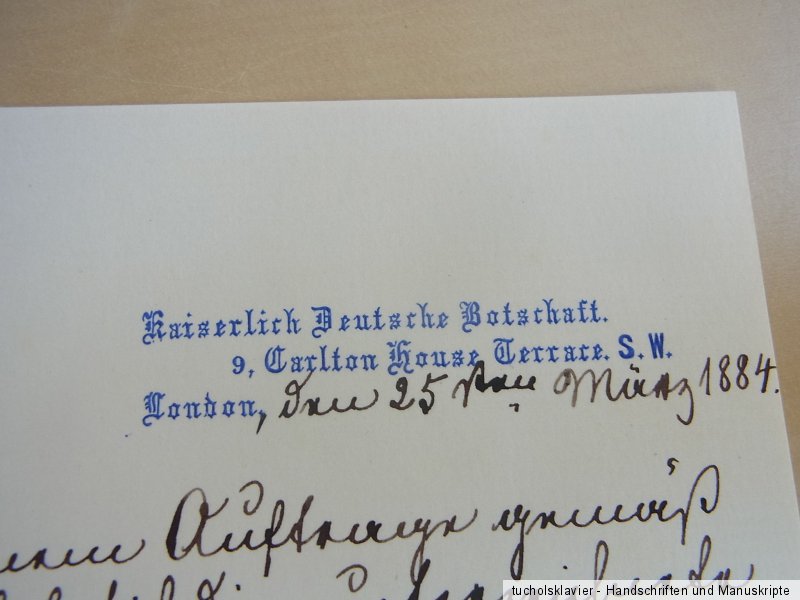

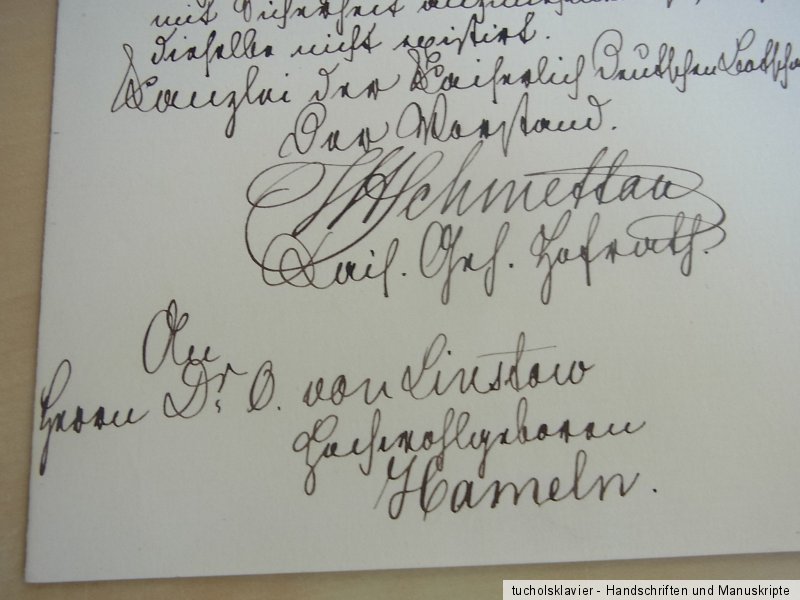

5.) Letter from the Imperial German Embassy in London dated 25. March 1884, addressed to Otto von Linstow in Hameln.

Quote: "[...] that a wealthy aristocratic Livingstone family in England is not listed in Burke's works 'Peerage and Baronetage' and 'Landed Gentry' and it can therefore be assumed with certainty that it does not exist."

Signed by the head of the Chancellery of the Imperial German Embassy, Hofrat Wilhelm Adolf von Schmettau.

Scope: one of four pages described (20.2 x 12.5 cm).

Condition: Paper partly browned and stained, partly with edge damage. The letter from the London embassy was received excellently. bPlease also note the pictures at the end of the item description!

Internal note: Linstow 10

Pictures

TRIXUM: Mobile-optimized auction templates and image hosting

About David Livingstone, Otto von Linstow and the Linstow family (source: wikipedia):

David Livingstone (*19. March 1813 in Blantyre near Glasgow; † 1. May 1873 in Chitambo on Lake Bangweulu) was a Scottish missionary and an African explorer.

Life: The Congregateionalist Livingstone was initially a cotton spinner, but also worked in medicine and theology. In 1840 Livingstone went to South Africa as a missionary for the London Missionary Society. On 2. In January 1845 he married Mary Moffat, a daughter of the missionary Robert Moffat.

Research trips: In 1849 he hiked from the Kolobeng mission station in Bechuan Country through the Kalahari Desert to Lake Ngami. Around 1850 he lived in Sangwali in what is now the Zambezi region of Namibia.[1] On a new journey in 1851 he reached the upper reaches of the Zambezi. He brought his wife and children to Cape Town, from where they left on the 23rd. April 1852 traveled to England on a sailing ship.[2] From 1853 to 1856 he crossed the whole of South Africa from the Zambezi to Loanda (Luanda) and back to Quelimane. In November 1855 he discovered the Victoria Falls of the Zambezi for Europe. Returning home, he published Missionary travels and researches in South Africa (London 1857, 2 volumes; new edition 1875; German, Leipzig 1859, 2 volumes).

In March 1858, on behalf of the British government, he went again to Quelimane and the Zambezi region with his brother Charles Livingstone and five other Europeans (including John Kirk and the painter Thomas Baines). He followed the Shire, a tributary on the lower reaches of the Zambezi, to its origins in Lake Malawi (formerly Lake Nyassa), where he arrived on the 16th. September 1859 arrived and discovered Lake Chilwa (Lake Shirwa) nearby. He also followed the Rovuma a long way up twice. His wife Mary joined him at the mouth of the Zambezi, but soon became ill with malaria and died on the 27th. April 1862.[3] Livingstone was unable to achieve his actual goal of counteracting the slave trade and, in particular, winning over the local population for agriculture and cotton cultivation. He therefore returned to Great Britain in 1864 and, together with his brother, published the Narrative of an expedition to the Zambesi and its tributaries (Lond. 1865; German, Jena 1865–1866, 2 volumes).

He embarked again in the fall of 1865 and landed in Zanzibar in January 1866. On the 24th In March 1866 he began his last research trip from Mikindani. A short time later a rumor spread that he had been killed; However, an expedition sent after him soon became convinced that this rumor was unfounded. Livingstone had traveled up the Rovuma to Lake Malawi, bypassed its southern shore, crossed the Chambeshi, one of the source rivers of the Congo, which had already been discovered by the Portuguese, reached the southern end of Lake Tanganyika in April 1867 and reached Lake Moero in April 1868, after having previously flowed from its outlet had discovered the Lualaba. In May 1868 he came to Cazembe, then traveled south through its area and discovered on the 18th July, Lake Bangweolo. From there he turned north and arrived on the 14th. In March 1869 he fell ill to Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika, where he stayed until July 1869.

In 1871, Livingstone witnessed Arab slave traders rushing into the middle of the crowd in the market square of Njangwe with around 1,500 people. They had previously surrounded the village. Many locals were taken away by the Arabs, 400 people died and 27 villages were burned down. Livingstone was outraged and separated from the Arabs.

He then explored Manyemaland west of it, from where he left on the 23rd. In October 1871, emaciated and exhausted, he returned to Ujiji. Henry Morton STANLEY , who had been sent by James Bennett in New York to find the traveler, who had been missing since 1869, arrived on the 10th. November 1871[6] Livingstone fell ill in Ujiji and greeted him with the legendary words “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” (“Doctor Livingstone, I presume?”). With STANLEY , Livingstone explored the northern end of Tanganyika in December 1871 and accompanied STANLEY to Unyanjembe.

Death: Despite his poor health, Livingstone wanted to stay in the interior of Africa and continue searching for the sources of the Nile. After waiting six months in Unyanjembe until the end of August 1872 for new resources, Livingstone set out for the area where he suspected the sources of the Nile. Livingstone went down the eastern bank of the Tanganyika, then around its southern end into the country of the Cazembe, and walked around the eastern half of Lake Bangweulu. He became sick and physically weaker. Finally, he had to be carried in a hammock on the march. On the 1st In May 1873 he died of dysentery in Ilala on the south bank of the Bangweulu.

The expedition under Veney Cameron sent by the British to support Livingstone came too late. But it was then the reason for the first crossing of Africa from east to west.

To illustrate Livingstone's saying "My heart is in Africa", his faithful companions Susi and Chuma, a slave freed by Livingstone, took the heart from his body and buried it under a tree. The tree is described in various sources as a Mvula tree (Milicia excelsia) or as an African baobab tree [7]. Today there is a monument there. Susi and Chuma embalmed his body and carried it with great danger and hardship to the east coast; from there she was embarked for Great Britain, where she arrived on the 18th. He was buried in Westminster Abbey in London in April 1874.

On his tombstone it says:

“Brought by faithful hands over land and sea, here rests David Livingstone, missionary, traveler, philanthropist, born March 19, 1813, at Blantyre, Lanarkshire, died May 1, 1873, at Chitambo's village, Ulala. […] Other sheep I have which are not of this fold; them also I must bring (John 10:16 KJV).”

“Brought here by faithful hands across land and sea, lies David Livingstone, missionary, traveler, philanthropist, born on the 19th. March 1813 in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, died on 1. May 1873 in Chitambo, Ulala. […] And I have other sheep that are not from this stable; I must also bring them here (John 10:16 ESV).”

The diaries and maps from his travels in the last eight years of his life, which were also saved, were published in German in Hamburg in 1875 by Horace Waller under the title: The last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa from 1865 to his death in 1874 in London[8].

Memberships: In 1858 Livingstone was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In 1869 he was accepted as a corresponding member of the Académie des Sciences.

Afterlife

namesake

Monument in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe

The following were named after Livingstone:

the town of Livingstone on the north bank of the Zambezi in what is now Zambia

the town of Livingstonia in the north of Malawi

the Livingstone Mountains in southern Tanzania

Livingstone Falls, rapids in the Congo River

Remembrance Day: The Evangelical Church in Germany remembers with a Remembrance Day on December 30th. April in the Evangelical Name Calendar to David Livingstone. (For evangelical remembrance of witnesses to the faith, see Confessio Augustana, Article 21.)

Music: In addition, the Swedish pop group ABBA honored him in 1974 with the song “What about Livingstone?” on their second album Waterloo.

The group The Moody Blues released the track “Dr. Livingstone, I Presume” on the album “In Search of the Lost Chord”.

Ken Roccard wrote the piece Livingstone, Negro Rhythms for wind orchestra.

Movie

STANLEY and Livingstone (1939) – Director: Henry King, Starring: Sir Cedric Hardwicke (Livingstone), Spencer Tracy ( STANLEY )

Forbidden Territory: STANLEY 's Search for Livingstone (1997) - Director: Simon Langton, Starring: Nigel Hawthorne (Livingstone), Aidan Quinn ( STANLEY )

Museums

Livingstone Museum, Livingstone, Zambia

Livingstone Museum, Sangwali, Namibia

factories

David Livingstone: Mission trips and research in South Africa. German edition in two volumes Leipzig, Verlag Hermann Costenoble 1858.

The text excerpt The discovery of the Victoria Falls of the Zambezi was published with a short biography in: Johannes Paul (ed.): From Greenland to Lambarene. Travel descriptions by Christian missionaries from three centuries. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1952, pp. 74–82. = Kreuz-Verlag, Stuttgart 1958, pp. 70–78.

David Livingstone: “Opening up the dark continent”. Travel diaries 1866–1873 until his death. traveldiary history, SDS Verlag, Hamburg/Norderstedt 2006.

Otto Friedrich Bernhard von Linstow (*17. October 1842 in Itzehoe; † 3. May 1916 in Göttingen) was a German medical officer and helminthologist.

Life: His parents were the Danish lieutenant and later postmaster Bückeburg August Wilhelm Franz von Linstow (* 21. November 1814; † 13. June 1887) and his wife August Sophie Johanne née Schönfeldt (* 26. October 1819; † 23. November 1899).

After attending school in Bückeburg and Hamburg, Linstow studied medicine from 1862 at the Christian Albrechts University in Kiel, later the Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg, and the Georg August University of Göttingen. He became a member of the Corps Holsatia (1863) and the Corps Brunsviga Göttingen (1865). 1866 in Kiel for Dr. med. After receiving his doctorate, he joined the Prussian Army in 1868. He served as a military doctor in Ratzeburg, Stade and Hagenau. He took part in the Franco-Prussian War. He was a staff and battalion doctor in Hameln from around 1880 and a senior staff doctor and regimental doctor in Göttingen from 1887. On the 7th In May 1904 he retired as senior physician general.

Linstow devoted himself to helminthology, entomology and lepidopterology. He examined the worms brought back by the Challenger expedition. As a specialist in worm diseases, he was appointed professor in 1911.

On the 30th In June 1870 he had Anna Emilie Franziska Henriette von Campe (* 12. May 1845) married. The couple had two sons and a daughter. Two children died young. Only the eldest son Otto von Linstow (geologist) survived.

Awards

Challenger Medal

Corresponding member of the Senckenberg Society for Natural Research

Corresponding Member of the Zoological Society of London

Fonts

Compendium of Helminthology. A list of the known helminths that live freely or in animal bodies, sorted according to the animals they live in, stating the organs in which they are found and citing the literary sources. Hanover: Hahn'sche Buchhandlung, 1878, digital copy, with addendum 1889.

Poisonous animals and their effect on humans: a handbook for physicians. Berlin: A. Hirschwald 1894.

Nemathelminths, results of the Hamburg Magalhaens collecting trip 1896, III, 8.

Nematodes of the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, Proc. Royal Society of Edinburgh, Vol. 26, 1906.

Nematodes from the Berlin Zoological Collection. Berlin, R. Friedländer and son 1899.

Report on the Entozoa collected by HMS Challenger during the years 1873–76, Report of the scientific results of the voyage of HMS Challenger, Volume 23, Part 4, 1880.

Linstow is the name of a Mecklenburg nobility with the same name in Linstow.

History: The gender appears in documents for the first time on the 22nd. July 1281 in Rostock with the knight Gherardus de Linstowe. The family line begins with the knight Heinrich von Linstow, who is mentioned in documents from 1301 to 1318. The family still exists today in Germany and in some strong lines in Denmark. She was born there on the 28th. January 1777 the Danish nobility naturalization was granted.

Anna von Linstow, b. von Levetzow entered the Dobbertin monastery as a widow in 1500 and bequeathed 100 guilders to the monastery for her daughters Dorothea and Anna, who lived there. From 1682 to 1704, Ilsabe Lucie von Linstow was a conventual in the Dobbertin monastery.

In the registration book of the Dobbertin monastery there are eight entries from daughters of the von Linstow families from Bellin, Diestelow and Vietschow from the years 1736–1814 for admission to the local aristocratic women's monastery. Around 1880, the von Linstow family had their Linstow manor house, which was probably built during the Thirty Years' War, rebuilt.

The estate in Klocksin belonged until the 14th century. century of the family.

Damerow Castle and Estate or Neu Damerow was family property from 1605 to 1784.

Coat of arms: The coat of arms is divided into silver and black (oldest seal from 3. March 1325). On the helmet with black and silver covers two virgins growing forward, one white, the other black, each holding a green wreath in their outstretched outer hands and one in the middle together.

Well-known namesakes

Conrad (von) Linstow, provost of the Dobbertin monastery in 1317[4]

Hans (Ernst Johann) von Linstow (1523–1592), heir to Bellin, provisionalist in the Dobbertin monastery from 1569 to 1583, involved as a visitor in 1571 in the elimination of the Catholic faith and the dissolution of the Dobbertin nunnery

Georg von Linstow (1593–1650), monastery captain in Dobbertin from 1622 to 1628, Wallenstein's appellate judge in Güstrow in 1630.[6]

Heinrich Wilhelm von Linstow (2nd January 1709 to 29. April 1759), Hanoverian colonel from the Inf.-Reg. Linstow, wounded and captured in the Battle of Bergen, died in Frankfurt[7]

August von Linstow (1775–1848), Danish district administrator for the Sonderburg district

Hans Ditlev Franciscus von Linstow (Hans Ditlev Frants von Linstow; 1787–1851), Norwegian architect

Hans Otfried von Linstow (1899–1944), German colonel and resistance fighter

Hartwig von Linstow (1810–1884), Danish-German administrative lawyer, acting president of the government of the Duchy of Lauenburg in Ratzeburg

Hugo von Linstow (1821–1899), Prussian officer, co-founder in 1869 and 1st Chairman of the HEROLD. Association for Heraldry, Genealogy and Related Sciences in Berlin.

Adolf von Linstow (1832–1902), Prussian lieutenant general

Waldemar von Linstow (1859–1925), Prussian major general

Otto von Linstow (medical doctor) (1842–1916), German military doctor and zoologist

Otto von Linstow (geologist) (1872–1929), German geologist