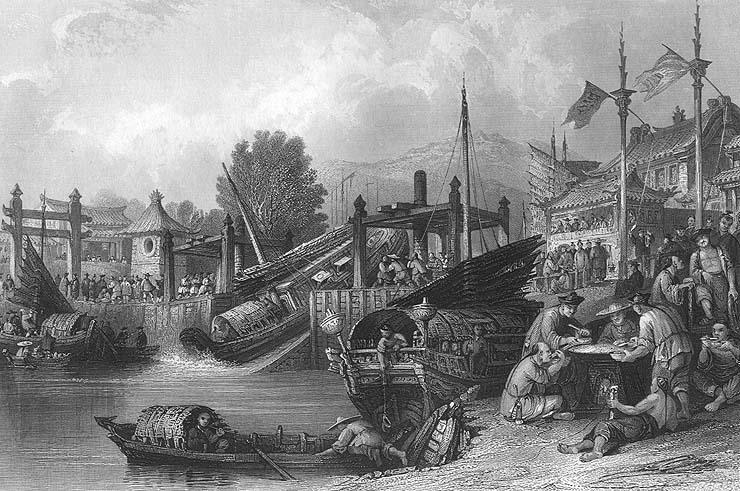

JUNKS PASSING AN INCLINED PLANE ON THE IMPERIAL CANAL Artist: Thomas Allom ____________ Engraver: W. Floyd |

VERY OLD WORLD! INCREDIBLE DETAIL!

Though he traveled widely in the course of his work, Allom produced his drawings of China, probably his most successful series, by merely crossing the road from the house in Hart Street to the British Museum. It was obviously an economical solution for his publisher, who had managed to convince himself that 'Having dwelt in "the land of the cypress and myrtle", Mr. Allom's talents were fully matured for the faithful delineation of Oriental scenery. His designs were based entirely on the work of earlier artists who had traveled in China, and although he has been justifiably criticised for failure in some instances to acknowledge the original sketches, Allom displays considerable resourcefulness and ingenuity in the way he borrowed and gathered his material from them. Acknowledgement was made to three amateurs, eight of the plates to Lieutenant Frederick White R.M., fourteen to Captain Stoddart, R.N. and two to R. Varnham (who was the son of a tea planter and a pupil of George Chinnery (1774-1852). Nine designs are taken entirely or partially from Sketches of China and the Chinese (1842) by August Borget (1808-1877)," which had been published in England the previous year. He made neat pencil sketches from an album of Chinese landscapes water colours by anonymous Chinese artists that he then turned into fourteen designs. "Another group are based on a set of anonymous drawings that show the silk manufacturing process. Allom made particularly ingenious use of the drawings of William Alexander (1767-1818). Having first traced over a number of Alexander's watercolors in the British Museum (a practice which would certainly be frowned upon today) he used these tracings' either in part or combination in about twenty of his designs. But he never uses exactly the same scene as Alexander without altering the viewpoint or changing the details, his knowledge of perspective enabling him 'to walk round' a view of a building as in his Western Gates of Peking, which takes a viewpoint to the other side of the river. He uses background to Alexander's more peaceful seascape of 1794, The Forts of Anunghoi saluting the 'Lion' in the Bocca Tigris, and updates it to an event sketched by White during the First Opium War of 1841 when the Imogene and Andromache under Lord Napier forced a passage through the straits. Two of Alexander's drawings are sometimes combined - his Chinamen playing 'Shitticock' (sic) are placed by Allom in front of the Pagoda of Lin-ching-shih taken from another Alexander drawing.

The prints were a welcome addition to Fisher's series and became the best known source on the subject of China. Until the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 China had been almost totally inaccessible to the European traveller but the first Opium War had created a new sort of interest. The admiration of the 18th and early 19th centuries for Chinese culture and decoration was replaced by a more critical and inquiring attitude. Until photography gave a more accurate picture, a great many people's perception of China and the Chinese people was probably influenced by Allom's idealised images. An interesting use of these, on the ceramic pot lids produced by F. & R. Pratt and Co. throughout the second half of the 19th century, demonstrate how Allom's images, themselves derived from such a variety of sources, became in turn a design source for other ornamental applications. Because of their decorative appeal wide use is still made of reproductions of these illustrations.

We pack properly to protect your item!

Please note: the terms used in our auctions for engraving, heliogravure, lithograph, print, plate, photogravure etc. are ALL prints on paper, NOT blocks of steel or wood. "ENGRAVINGS", the term commonly used for these paper prints, were the most common method in the 1700s and 1800s for illustrating old books, and these paper prints or "engravings" were inserted into the book with a tissue guard frontis, usually on much thicker quality rag stock paper, although many were also printed and issued as loose stand alone prints. So this auction is for an antique paper print(s), probably from an old book, of very high quality and usually on very thick rag stock paper.