Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan;[3] born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Often considered to be one of the greatest songwriters in history,[4][5][6] Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture over his 60-year career. He rose to prominence in the 1960s, when his songs "Blowin' in the Wind" (1963) and "The Times They Are a-Changin'" (1964) became anthems for the civil rights and antiwar movements. Initially modeling his style on Woody Guthrie's folk songs,[7] Robert Johnson's blues,[8] and what he called the "architectural forms" of Hank Williams's country songs,[9] Dylan added increasingly sophisticated lyrical techniques to the folk music of the early 1960s, infusing it "with the intellectualism of classic literature and poetry".[4] His lyrics incorporated political, social, and philosophical influences, defying pop music conventions and appealing to the burgeoning counterculture.[10]

Dylan was born and raised in St. Louis County, Minnesota. Following his self-titled debut album of traditional folk songs in 1962, he made his breakthrough with The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan the next year. The album features "Blowin' in the Wind" and "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" which, like many of his early songs, adapted the tunes and phrasing of older folk songs. He released the politically charged The Times They Are a-Changin' and the more lyrically abstract and introspective Another Side of Bob Dylan in 1964. In 1965 and 1966, Dylan drew controversy among folk purists when he adopted electrically amplified rock instrumentation, and in the space of 15 months recorded three of the most influential rock albums of the 1960s: Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited (both 1965) and Blonde on Blonde (1966). When Dylan made his move from acoustic folk and blues music to rock, the mix became more complex. His six-minute single "Like a Rolling Stone" (1965) expanded commercial and creative boundaries in popular music.[11][12]

In July 1966, a motorcycle accident led to Dylan's withdrawal from touring. During this period, he recorded a large body of songs with members of the Band, who had previously backed him on tour. These recordings were later released as The Basement Tapes in 1975. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dylan explored country music and rural themes on John Wesley Harding (1967), Nashville Skyline (1969) and New Morning (1970). In 1975, he released Blood on the Tracks, which many saw as a return to form. In the late 1970s, he became a born-again Christian and released three albums of contemporary gospel music before returning to his more familiar rock-based idiom in the early 1980s. Dylan's Time Out of Mind (1997) marked the beginning of a career renaissance. He has released five critically acclaimed albums of original material since, most recently Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020). He also recorded a trilogy of albums covering the Great American Songbook, especially songs sung by Frank Sinatra, and an album smoothing his early rock material into a mellower Americana sensibility, Shadow Kingdom (2023). Dylan has toured continuously since the late 1980s on what has become known as the Never Ending Tour.[13]

Since 1994, Dylan has published nine books of paintings and drawings, and his work has been exhibited in major art galleries. He has sold more than 145 million records,[14] making him one of the best-selling musicians ever. He has received numerous awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, ten Grammy Awards, a Golden Globe Award and an Academy Award. Dylan has been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame and the Songwriters Hall of Fame. In 2008, the Pulitzer Prize Board awarded him a special citation for "his profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power." In 2016, Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition."[15]

Life and career

1941–1959: Origins and musical beginnings

Bob Dylan was born Robert Allen Zimmerman (Hebrew: שבתאי זיסל בן אברהם Shabtai Zisl ben Avraham)[1][16][17] in St. Mary's Hospital on May 24, 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota,[18] and raised in Hibbing, Minnesota, on the Mesabi Range west of Lake Superior. Dylan's paternal grandparents, Anna Kirghiz and Zigman Zimmerman, emigrated from Odessa in the Russian Empire (now Odesa, Ukraine) to the United States, following the pogroms against Jews of 1905.[19] His maternal grandparents, Florence and Ben Stone, were Lithuanian Jews who had arrived in the United States in 1902.[19] Dylan wrote that his paternal grandmother's family was originally from the Kağızman district of Kars Province in northeastern Turkey.[20]

Dylan's father Abram Zimmerman and his mother Beatrice "Beatty" Stone were part of a small, close-knit Jewish community.[21][22][23] They lived in Duluth until Dylan was six, when his father contracted polio and the family returned to his mother's hometown of Hibbing, where they lived for the rest of Dylan's childhood, and his father and paternal uncles ran a furniture and appliance store.[23][24] In his early years he listened to the radio—first to blues and country stations from Shreveport, Louisiana, and later, when he was a teenager, to rock and roll.[25]

Dylan formed several bands while attending Hibbing High School. In the Golden Chords, he performed covers of songs by Little Richard[26] and Elvis Presley.[27] Their performance of Danny & the Juniors' "Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay" at their high school talent show was so loud that the principal cut the microphone.[28] In 1959, Dylan's high school yearbook carried the caption "Robert Zimmerman: to join 'Little Richard'".[26][29] That year, as Elston Gunnn, he performed two dates with Bobby Vee, playing piano and clapping.[30][31][32] In September 1959, Dylan moved to Minneapolis to enroll at the University of Minnesota.[33] Living at the Jewish-centric fraternity Sigma Alpha Mu house, Dylan began to perform at the Ten O'Clock Scholar, a coffeehouse a few blocks from campus, and became involved in the Dinkytown folk music circuit.[34][35] His focus on rock and roll gave way to American folk music, as he explained in a 1985 interview:

The thing about rock'n'roll is that for me anyway it wasn't enough ... There were great catch-phrases and driving pulse rhythms ... but the songs weren't serious or didn't reflect life in a realistic way. I knew that when I got into folk music, it was more of a serious type of thing. The songs are filled with more despair, more sadness, more triumph, more faith in the supernatural, much deeper feelings.[36]

During this period, he began to introduce himself as "Bob Dylan".[37] In his memoir, he wrote that he considered adopting the surname Dillon before unexpectedly seeing poems by Dylan Thomas, and deciding upon the given name spelling.[38][a 1] Explaining his change of name in a 2004 interview, he said, "You're born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself. This is the land of the free."[39]

1960s

Relocation to New York and record deal

In May 1960, Dylan dropped out of college at the end of his first year. In January 1961, he traveled to New York City to perform there and visit his musical idol Woody Guthrie,[40] who was seriously ill with Huntington's disease in Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital.[41] Guthrie had been a revelation to Dylan and influenced his early performances. He wrote of Guthrie's impact: "The songs themselves had the infinite sweep of humanity in them... [He] was the true voice of the American spirit. I said to myself I was going to be Guthrie's greatest disciple".[42] In addition to visiting Guthrie in hospital, Dylan befriended his protégé Ramblin' Jack Elliott.[43]

From February 1961, Dylan played at clubs around Greenwich Village, befriending and picking up material from folk singers, including Dave Van Ronk, Fred Neil, Odetta, the New Lost City Ramblers and Irish musicians the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem.[44] In September, The New York Times critic Robert Shelton boosted Dylan's career with a very enthusiastic review of his performance at Gerde's Folk City: "Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Folk-Song Stylist".[45] That month, Dylan played harmonica on folk singer Carolyn Hester's third album, bringing him to the attention of the album's producer John Hammond,[46] who signed Dylan to Columbia Records.[47] Dylan's debut album, Bob Dylan, released March 19, 1962,[48][49] consisted of traditional folk, blues and gospel material with just two original compositions, "Talkin' New York" and "Song to Woody". The album sold 5,000 copies in its first year, just enough to break even.[50]

In August 1962, Dylan took two decisive steps in his career. He changed his name to Bob Dylan,[a 2] and he signed a management contract with Albert Grossman.[51] Grossman remained Dylan's manager until 1970, and was known for his sometimes confrontational personality and protective loyalty.[52] Dylan said, "He was kind of like a Colonel Tom Parker figure ... you could smell him coming."[35] Tension between Grossman and John Hammond led to the latter suggesting Dylan work with the jazz producer Tom Wilson, who produced several tracks for the second album without formal credit. Wilson produced the next three albums Dylan recorded.[53][54]

Dylan made his first trip to the United Kingdom from December 1962 to January 1963.[55] He had been invited by television director Philip Saville to appear in a drama, Madhouse on Castle Street, which Saville was directing for BBC Television.[56] At the end of the play, Dylan performed "Blowin' in the Wind", one of its first public performances.[56] While in London, Dylan performed at London folk clubs, including the Troubadour, Les Cousins, and Bunjies.[55][57] He also learned material from UK performers, including Martin Carthy.[56]

By the release of Dylan's second album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, in May 1963, he had begun to make his name as a singer-songwriter. Many songs on the album were labeled protest songs, inspired partly by Guthrie and influenced by Pete Seeger's passion for topical songs.[58] "Oxford Town" was an account of James Meredith's ordeal as the first black student to risk enrollment at the University of Mississippi.[59] The first song on the album, "Blowin' in the Wind", partly derived its melody from the traditional slave song "No More Auction Block"[60] while its lyrics questioned the social and political status quo. The song was widely recorded by other artists and became a hit for Peter, Paul and Mary.[61] "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" was based on the folk ballad "Lord Randall". With its apocalyptic premonitions, the song gained resonance when the Cuban Missile Crisis developed a few weeks after Dylan began performing it.[62][a 3] Like "Blowin' in the Wind", "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" marked a new direction in songwriting, blending a stream-of-consciousness, imagist lyrical attack with traditional folk form.[63]

Dylan's topical songs led to his being viewed as more than just a songwriter. Janet Maslin wrote of Freewheelin': "These were the songs that established [Dylan] as the voice of his generation—someone who implicitly understood how concerned young Americans felt about nuclear disarmament and the growing Civil Rights Movement: his mixture of moral authority and nonconformity was perhaps the most timely of his attributes."[64][a 4] Freewheelin' also included love songs and surreal talking blues. Humor was an important part of Dylan's persona from the start,[65] and the range of material on the album impressed listeners, including the Beatles. George Harrison said of the album: "We just played it, just wore it out. The content of the song lyrics and just the attitude—it was incredibly original and wonderful".[66]

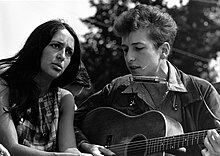

The rough edge of Dylan's singing unsettled some but attracted others. Author Joyce Carol Oates wrote: "When we first heard this raw, very young, and seemingly untrained voice, frankly nasal, as if sandpaper could sing, the effect was dramatic and electrifying".[67] Many early songs reached the public through more palatable versions by other performers, such as Joan Baez, who became Dylan's advocate and lover.[68] Baez was influential in bringing Dylan to prominence by recording several of his early songs and inviting him on stage during her concerts.[69] Others who had hits with Dylan's songs in the early 1960s included the Byrds, Sonny & Cher, the Hollies, the Association, Manfred Mann and the Turtles.

"Mixed-Up Confusion", recorded during the Freewheelin' sessions with a backing band, was released as Dylan's first single in December 1962, but then swiftly withdrawn. In contrast to the mostly solo acoustic performances on the album, the single showed a willingness to experiment with a rockabilly sound. Cameron Crowe described it as "a fascinating look at a folk artist with his mind wandering towards Elvis Presley and Sun Records".[70]

Protest and Another Side

In May 1963, Dylan's political profile rose when he walked out of The Ed Sullivan Show. During rehearsals, Dylan had been told by CBS television's head of program practices that "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues" was potentially libelous to the John Birch Society. Rather than comply with censorship, Dylan refused to appear.[71]

By this time, Dylan and Baez were prominent in the civil rights movement, singing together at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963.[72] Dylan's third album, The Times They Are a-Changin', reflected a more politicized Dylan.[73] The songs often took as their subject matter contemporary stories, with "Only a Pawn in Their Game" addressing the murder of civil rights worker Medgar Evers; and the Brechtian "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" the death of black hotel barmaid Hattie Carroll at the hands of young white socialite William Zantzinger.[74] "Ballad of Hollis Brown" and "North Country Blues" addressed despair engendered by the breakdown of farming and mining communities. This political material was accompanied by two personal love songs, "Boots of Spanish Leather" and "One Too Many Mornings".[75]

By the end of 1963, Dylan felt both manipulated and constrained by the folk and protest movements.[76] Accepting the "Tom Paine Award" from the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee shortly after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, an intoxicated Dylan questioned the role of the committee, characterized the members as old and balding, and claimed to see something of himself and of every man in Kennedy's assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald.[77]

Another Side of Bob Dylan, recorded in a single evening on June 9, 1964,[78] had a lighter mood. The humorous Dylan reemerged on "I Shall Be Free No. 10" and "Motorpsycho Nightmare". "Spanish Harlem Incident" and "To Ramona" are passionate love songs, while "Black Crow Blues" and "I Don't Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met)" suggest the rock and roll soon to dominate Dylan's music. "It Ain't Me Babe", on the surface a song about spurned love, has been described as a rejection of the role of political spokesman thrust upon him.[79] His new direction was signaled by two lengthy songs: the impressionistic "Chimes of Freedom", which sets social commentary against a metaphorical landscape in a style characterized by Allen Ginsberg as "chains of flashing images,"[a 5] and "My Back Pages", which attacks the simplistic and arch seriousness of his own earlier topical songs and seems to predict the backlash he was about to encounter from his former champions.[80]

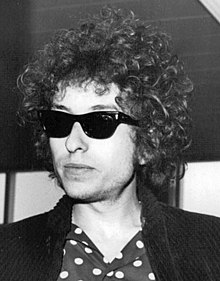

In the latter half of 1964 and into 1965, Dylan moved from folk songwriter to folk-rock pop-music star. His jeans and work shirts were replaced by a Carnaby Street wardrobe, sunglasses day or night, and pointed "Beatle boots". A London reporter noted "Hair that would set the teeth of a comb on edge. A loud shirt that would dim the neon lights of Leicester Square. He looks like an undernourished cockatoo."[81] Dylan began to spar with interviewers. Asked about a movie he planned while on Les Crane's television show, he told Crane it would be a "cowboy horror movie." Asked if he played the cowboy, Dylan replied, "No, I play my mother."[82]

Going electric

Dylan's late March 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home was another leap,[83] featuring his first recordings with electric instruments, under producer Tom Wilson's guidance.[84] The first single, "Subterranean Homesick Blues", owed much to Chuck Berry's "Too Much Monkey Business";[85] its free-association lyrics described as harking back to the energy of beat poetry and as a forerunner of rap and hip-hop.[86] The song was provided with an early music video, which opened D. A. Pennebaker's cinéma vérité presentation of Dylan's 1965 tour of Great Britain, Dont Look Back.[87] Instead of miming, Dylan illustrated the lyrics by throwing cue cards containing key words from the song on the ground. Pennebaker said the sequence was Dylan's idea, and it has been imitated in music videos and advertisements.[88]

The second side of Bringing It All Back Home contained four long songs on which Dylan accompanied himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica.[89] "Mr. Tambourine Man" became one of his best-known songs when The Byrds recorded an electric version that reached number one in the US and UK.[90][91] "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" and "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" were two of Dylan's most important compositions.[89][92]

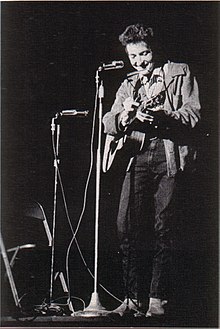

In 1965, headlining the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan performed his first electric set since high school with a pickup group featuring Mike Bloomfield on guitar and Al Kooper on organ.[93] Dylan had appeared at Newport in 1963 and 1964, but in 1965 met with cheering and booing and left the stage after three songs. One version has it that the boos were from folk fans whom Dylan had alienated by appearing, unexpectedly, with an electric guitar. Murray Lerner, who filmed the performance, said: "I absolutely think that they were booing Dylan going electric."[94] An alternative account claims audience members were upset by poor sound and a short set.[95][96]

Nevertheless, Dylan's performance provoked a hostile response from the folk music establishment.[97][98] In the September issue of Sing Out!, Ewan MacColl wrote: "Our traditional songs and ballads are the creations of extraordinarily talented artists working inside disciplines formulated over time ...'But what of Bobby Dylan?' scream the outraged teenagers ... Only a completely non-critical audience, nourished on the watery pap of pop music, could have fallen for such tenth-rate drivel".[99] On July 29, four days after Newport, Dylan was back in the studio in New York, recording "Positively 4th Street". The lyrics contained images of vengeance and paranoia,[100] and have been interpreted as Dylan's put-down of former friends from the folk community he had known in clubs along West 4th Street.[101]

Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde

In July 1965, Dylan's six-minute single "Like a Rolling Stone" peaked at number two in the US chart. In 2004 and in 2011, Rolling Stone listed it as number one on "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[11][102] Bruce Springsteen recalled first hearing the song: "that snare shot sounded like somebody'd kicked open the door to your mind."[103] The song opened Dylan's next album, Highway 61 Revisited, named after the road that led from Dylan's Minnesota to the musical hotbed of New Orleans.[104] The songs were in the same vein as the hit single, flavored by Mike Bloomfield's blues guitar and Al Kooper's organ riffs. "Desolation Row", backed by acoustic guitar and understated bass,[105] offers the sole exception, with Dylan alluding to figures in Western culture in a song described by Andy Gill as "an 11-minute epic of entropy, which takes the form of a Fellini-esque parade of grotesques and oddities featuring a huge cast of celebrated characters, some historical (Einstein, Nero), some biblical (Noah, Cain and Abel), some fictional (Ophelia, Romeo, Cinderella), some literary (T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound), and some who fit into none of the above categories, notably Dr. Filth and his dubious nurse".[106] Poet Philip Larkin, who also reviewed jazz for The Daily Telegraph, wrote "I'm afraid I poached Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited (CBS) out of curiosity and found myself well rewarded."[107]

In support of the album, Dylan was booked for two US concerts with Al Kooper and Harvey Brooks from his studio crew and Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm, former members of Ronnie Hawkins's backing band the Hawks.[108] On August 28 at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium, the group was heckled by an audience still annoyed by Dylan's electric sound. The band's reception on September 3 at the Hollywood Bowl was more favorable.[109]

From September 24, 1965, in Austin, Texas, Dylan toured the US and Canada for six months, backed by the five musicians from the Hawks who became known as The Band.[110] While Dylan and the Hawks met increasingly receptive audiences, their studio efforts foundered. Producer Bob Johnston persuaded Dylan to record in Nashville in February 1966, and surrounded him with top-notch session men. At Dylan's insistence, Robertson and Kooper came from New York City to play on the sessions.[111] The Nashville sessions produced the double album Blonde on Blonde (1966), featuring what Dylan called "that thin wild mercury sound".[112] Kooper described it as "taking two cultures and smashing them together with a huge explosion": the musical worlds of Nashville and of the "quintessential N

Henry St. Claire Fredericks Jr. (born May 17, 1942), better known by his stage name Taj Mahal, is an American blues musician. He plays the guitar, piano, banjo, harmonica, and many other instruments,[1] often incorporating elements of world music into his work. Mahal has done much to reshape the definition and scope of blues music over the course of his more than 50-year career by fusing it with nontraditional forms, including sounds from the Caribbean, Africa, India, Hawaii, and the South Pacific.[2]

Early life

Mahal was born Henry St. Claire Fredericks Jr. on May 17, 1942, in Harlem, New York City. Growing up in Springfield, Massachusetts, he was raised in a musical environment: his mother was a member of a local gospel choir and his father, Henry Saint Claire Fredericks Sr., was an Afro-Caribbean jazz arranger and piano player. His family owned a shortwave radio which received music broadcasts from around the world, exposing him at an early age to world music.[3] Early in childhood he recognized the stark differences between the popular music of his day and the music that was played in his home. He also became interested in jazz, enjoying the works of musicians such as Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk and Milt Jackson.[4] His parents came of age during the Harlem Renaissance, instilling in their son a sense of pride in his Caribbean and African ancestry through their stories.[5]

Because his father was a musician, his home frequently hosted other musicians from the Caribbean, Africa, and the US. His father was called "The Genius" by Ella Fitzgerald before starting his family.[6] Early on, Henry Jr. developed an interest in African music, which he studied assiduously as a young man. His parents encouraged him to pursue music, starting him out with classical piano lessons. He also studied the clarinet, trombone and harmonica.[7]

When Henry Jr. was eleven years old, his father was killed in an accident at his construction company, crushed by a tractor when it flipped over. It was an extremely traumatic experience for the boy.[6] Mahal's mother later remarried. His stepfather owned a guitar which Henry Jr. began using at age 13 or 14, receiving his first lessons from a new neighbor from North Carolina of his own age who played acoustic blues guitar.[7] His name was Lynwood Perry, the nephew of the famous bluesman Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup. In high school Henry Jr. sang in a doo-wop group.[6]

For some time he thought of pursuing farming over music. His passion began on a dairy farm in Palmer, Massachusetts, not far from Springfield, at age 16. By 19, he had become farm foreman. "I milked anywhere between thirty-five and seventy cows a day. I clipped udders. I grew corn. I grew Tennessee redtop clover. Alfalfa."[8] Mahal believes in growing one's own food, saying, "You have a whole generation of kids who think everything comes out of a box and a can, and they don't know you can grow most of your food." Because of his personal support of the family farm, Mahal regularly performs at Farm Aid concerts.[8]

Henry chose his stage name, Taj Mahal, from dreams he had about Mahatma Gandhi, India, and social tolerance. He started using the stage name in 1959[9] or 1961[6]—around the same time he began attending the University of Massachusetts. Despite having attended a vocational agriculture school, becoming a member of the National FFA Organization, and majoring in animal husbandry and minoring in veterinary science and agronomy, Mahal decided to pursue music instead of farming. In college he led a rhythm and blues band called Taj Mahal & The Elektras. Before heading for the U.S. West Coast, he was also part of a duo with Jessie Lee Kincaid.[6]

Career

Mahal moved to Santa Monica, California, in 1964 and formed Rising Sons with fellow blues rock musicians Ry Cooder and Jessie Lee Kincaid, landing a record deal with Columbia Records soon after. After the Rising Sons disbanded, Jesse Ed Davis, a Kiowa native from Oklahoma, joined Taj Mahal and played guitar and piano on Mahal's first four albums. The group was one of the first interracial bands of the period, which may have hampered their commercial viability.[10] However, Rising Sons bassist Gary Marker later recalled the band's members had come to a creative impasse and were unable to reconcile their musical and personal differences even with the guidance of veteran producer Terry Melcher.[11] They recorded enough songs for a full-length album, but released only a single and the band soon broke up. Legacy Records did release The Rising Sons Featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder in 1992 with material from that period. During this time Mahal was also working with other musicians like Howlin' Wolf, Buddy Guy, Lightnin' Hopkins, and Muddy Waters.[7]

Mahal stayed with Columbia for his solo career, releasing the self-titled Taj Mahal and The Natch'l Blues in 1968. His track "Statesboro Blues" was featured on side 2 of the very successful Columbia/CBS sampler album, The Rock Machine Turns You On, giving a huge early impetus to his career. Giant Step/De Old Folks at Home with session musician Jesse Ed Davis followed in 1969.[12] During this time he and Cooder worked with the Rolling Stones, with whom he has performed at various times throughout his career.[13] In 1968, he performed in the film The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus. In 1969, he performed at the Gold Rush rock music festival in Amador County.[14]

Mahal recorded a total of twelve albums for Columbia from the late 1960s into the 1970s. His work of the 1970s was especially important, in that his releases began incorporating West Indian and Caribbean music, jazz and reggae into the mix. In 1972, he acted in and wrote the film score for the movie Sounder, which starred Cicely Tyson.[13] He reprised his role and returned as composer in the sequel, Part 2, Sounder.[15]

In 1976 Mahal left Columbia and signed with Warner Bros. Records, recording three albums for them. One of these was another film score for 1977's Brothers; the album shares the same name. After his time with Warner Bros., he struggled to find another record contract, this being the era of heavy metal and disco music.

Stalled in his career, he decided to move to Kauai, Hawaii in 1981 and soon formed the Hula Blues Band. Originally just a group of guys getting together for fishing and a good time, the band soon began performing regularly and touring.[16] He maintained a low public profile in Hawaii throughout most of the 1980s before recording Taj in 1988 for Gramavision.[13] This started a comeback of sorts for him, recording both for Gramavision and Hannibal Records during this time.

In the 1990s Mahal became deeply involved in supporting the nonprofit Music Maker Relief Foundation.[17][18] As of 2019, he was still on the Foundation's advisory board.[19]

In the 1990s he was on the Private Music label, releasing albums full of blues, pop, R&B and rock. He did collaborative works both with Eric Clapton and Etta James.[13]

In 1995 he recorded a record fusing traditional American blues with Indian stringed instruments, Mumtaz Mahal, accompanied by Vishwa Mohan Bhatt on Mohan veena and N. Ravikiran on chitravina, a fretless lute.

In 1998, in collaboration with renowned songwriter David Forman, producer Rick Chertoff and musicians Cyndi Lauper, Willie Nile, Joan Osborne, Rob Hyman, Garth Hudson and Levon Helm of the Band, and the Chieftains, he performed on the Americana album Largo based on the music of Antonín Dvořák.

In 1997 he won Best Contemporary Blues Album for Señor Blues at the Grammy Awards, followed by another Grammy for Shoutin' in Key in 2000.[20] He performed the theme song to the children's television show Peep and the Big Wide World, which began broadcast in 2004.

In 2002, Mahal appeared on the Red Hot Organization's compilation album Red Hot and Riot in tribute to Nigerian afrobeat musician Fela Kuti. The Paul Heck produced album was widely acclaimed, and all proceeds from the record were donated to AIDS charities.

Taj Mahal contributed to Olmecha Supreme's 2006 album 'hedfoneresonance'.[21] The Wellington-based group led by Mahal's son Imon Starr (Ahmen Mahal) also featured Deva Mahal on vocals.[22]

Mahal partnered up with Keb' Mo' to release a joint album TajMo on May 5, 2017.[23] The album has some guest appearances by Bonnie Raitt, Joe Walsh, Sheila E., and Lizz Wright, and has six original compositions and five covers, from artists and bands like John Mayer and The Who.[24]

In 2013, Mahal appeared in the documentary film on Byrds founding member Gene Clark, 'The Byrd Who Flew Alone', produced by Four Suns Productions. Clark and Mahal had been friends for many years.[25]

In June 2017, Mahal appeared in the award-winning documentary film The American Epic Sessions, directed by Bernard MacMahon, recording Charley Patton's "High Water Everywhere"[26] on the first electrical sound recording system from the 1920s.[27] Mahal appeared throughout the accompanying documentary series American Epic, commenting on the 1920s rural recording artists who had a profound influence on American music and on him personally.[28]

Personal life

Mahal's first marriage was to Anna de Leon.[29] He refers to Anna in the song "Texas Woman Blues" with the spoken words "Señorita de Leon, escucha mi canción". That marriage produced one daughter, the novelist and professor Aya de Leon. Taj Mahal married Inshirah Geter on January 23, 1976, and together they have six children. His daughter Deva Mahal appeared on one episode of Dating Around.[30]

Musical style

Mahal leads with his thumb and middle finger when fingerpicking, rather than with his index finger as the majority of guitar players do. "I play with a flatpick," he says, "when I do a lot of blues leads."[7] Early in his musical career Mahal studied the various styles of his favorite blues singers, including musicians like Jimmy Reed, Son House, Sleepy John Estes, Big Mama Thornton, Howlin' Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, and Sonny Terry. He describes his hanging out at clubs like Club 47 in Massachusetts and Ash Grove in Los Angeles as "basic building blocks in the development of his music."[31] Considered to be a scholar of blues music, his studies of ethnomusicology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst would come to introduce him further to the folk music of the Caribbean and West Africa. Over time he incorporated more and more African roots music into his musical palette, embracing elements of reggae, calypso,[12] jazz, zydeco, R&B, gospel music, and the country blues—each of which having "served as the foundation of his unique sound."[3] According to The Rough Guide to Rock, "It has been said that Taj Mahal was one of the first major artists, if not the very first one, to pursue the possibilities of world music. Even the blues he was playing in the early 70s – Recycling The Blues & Other Related Stuff (1972), Mo' Roots (1974) – showed an aptitude for spicing the mix with flavours that always kept him a yard or so distant from being an out-and-out blues performer."[12] Concerning his voice, author David Evans writes that Mahal has "an extraordinary voice that ranges from gruff and gritty to smooth and sultry."[1]

Taj Mahal believes that his 1999 album Kulanjan, which features him playing with the kora master of Mali's Griot tradition Toumani Diabaté, "embodies his musical and cultural spirit arriving full circle." To him it was an experience that allowed him to reconnect with his African heritage, striking him with a sense of coming home.[4] He even changed his name to Dadi Kouyate, the first jali name, to drive this point home.[32] Speaking of the experience and demonstrating the breadth of his eclecticism, he has said:

The microphones are listening in on a conversation between a 350-year-old orphan and its long-lost birth parents. I've got so much other music to play. But the point is that after recording with these Africans, basically if I don't play guitar for the rest of my life, that's fine with me....With Kulanjan, I think that Afro-Americans have the opportunity to not only see the instruments and the musicians, but they also see more about their culture and recognize the faces, the walks, the hands, the voices, and the sounds that are not the blues. Afro-American audiences had their eyes really opened for the first time. This was exciting for them to make this connection and pay a little more attention to this music than before.[4]

Taj Mahal has said he prefers to do outdoor performances, saying: "The music was designed for people to move, and it's a bit difficult after a while to have people sitting like they're watching television. That's why I like to play outdoor festivals-because people will just dance. Theatre audiences need to ask themselves: 'What the hell is going on? We're asking these musicians to come and perform and then we sit there and draw all the energy out of the air.' That's why after a while I need a rest. It's too much of a drain. Often I don't allow that. I just play to the goddess of music-and I know she's dancing."[5]

Mahal has been quoted as saying, "Eighty-one percent of the kids listening to rap were not black kids. Once there was a tremendous amount of money involved in it ... they totally moved it over to a material side. It just went off to a terrible direction. ...You can listen to my music from front to back, and you don't ever hear me moaning and crying about how bad you done treated me. I think that style of blues and that type of tone was something that happened as a result of many white people feeling very, very guilty about what went down."[33]

Awards

Taj Mahal has received three Grammy Awards (ten nominations) over his career.[1]

- 1997 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Señor Blues[20]

- 2000 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Shoutin' in Key[20]

- 2006 (Blues Music Awards) Historical Album of the Year for The Essential Taj Mahal[34]

- 2008 (Grammy Nomination) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Maestro[20]

- 2018 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for TajMo[35]

On February 8, 2006, Taj Mahal was designated the official Blues Artist of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.[36]

In March 2006, Taj Mahal, along with his sister, the late Carole Fredericks, received the Foreign Language Advocacy Award from the Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages in recognition of their commitment to shine a spotlight on the vast potential of music to foster genuine intercultural communication.[37]

On May 22, 2011, Taj Mahal received an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree from Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. He also made brief remarks and performed three songs. A video of the performance can be found online.[38]

In 2014, Taj Mahal received the Americana Music Association's Lifetime Achievement award.

Curtis Lee Mayfield (June 3, 1942 – December 26, 1999) was an American singer-songwriter, guitarist, and record producer, and one of the most influential musicians behind soul and politically conscious African-American music.[5][6] Dubbed the "Gentle Genius",[7][8] he first achieved success and recognition with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame-inducted group the Impressions during the civil rights movement of the late 1950s and the 1960s, and later worked as a solo artist.

Mayfield started his musical career in a gospel choir. Moving to the North Side of Chicago, he met Jerry Butler in 1956 at the age of 14, and joined the vocal group The Impressions. As a songwriter, Mayfield became noted as one of the first musicians to bring more prevalent themes of social awareness into soul music. In 1965, he wrote "People Get Ready" for The Impressions, which was ranked at no. 24 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[9] The song received numerous other awards; it was included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's "500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll",[10] and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1998.

After leaving The Impressions in 1970 in the pursuit of a solo career, Mayfield released several albums, including the soundtrack for the blaxploitation film Super Fly in 1972. The soundtrack was noted for its socially conscious themes, mostly addressing problems surrounding inner city minorities such as crime, poverty and drug abuse. The album was ranked at no. 72 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[11]

Mayfield was paralyzed from the neck down after lighting equipment fell on him during a live performance at Wingate Field in Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York, on August 13, 1990.[12] Despite this, he continued his career as a recording artist, releasing his final album New World Order in 1996. Mayfield won a Grammy Legend Award in 1994 and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995.[13] He is a double inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, as a member of The Impressions in 1991, and again in 1999 as a solo artist. He was also a two-time Grammy Hall of Fame inductee. He died from complications of type 2 diabetes at the age of 57 on December 26, 1999.[14]

Early life

Curtis Lee Mayfield was born on Wednesday, June 3, 1942, in Cook County Hospital in Chicago, Illinois,[15] the son of Marion Washington and Kenneth Mayfield, one of five children.[16][17] Mayfield's father left the family when Curtis was five; his mother (and maternal grandmother) moved the family into several Chicago public housing projects before settling in Cabrini–Green during his teen years. Mayfield attended Wells Community Academy High School before dropping out his second year. His mother taught him piano and, along with his grandmother, encouraged him to enjoy gospel music. At the age of seven he sang publicly at his aunt's church with the Northern Jubilee Gospel Singers.[18]

Mayfield received his first guitar when he was ten, later recalling that he loved his guitar so much he used to sleep with it.[13] He was a self-taught musician, and he grew up admiring blues singer Muddy Waters and Spanish guitarist Andres Segovia.[13]

When he was 14 years old he formed the Alphatones when the Northern Jubilee Gospel Singers decided to try their luck in downtown Chicago and Mayfield stayed behind. Fellow group member Sam Gooden was quoted "It would have been nice to have him there with us, but of course, your parents have the first say."

Later in 1956, he joined his high school friend Jerry Butler's group The Roosters with brothers Arthur and Richard Brooks.[13] He wrote and composed songs for this group who would become The Impressions two years later.

Career

The Impressions

Mayfield's career began in 1956 when he joined the Roosters with Arthur and Richard Brooks and Jerry Butler.[19] Two years later the Roosters, now including Sam Gooden, became the Impressions.[19] The band had two hit singles with Butler, "For Your Precious Love" and "Come Back My Love", then Butler left. Mayfield temporarily went with him, co-writing and performing on Butler's next hit, "He Will Break Your Heart", before returning to the Impressions with the group signing for ABC Records and working with the label's Chicago-based producer/A&R manager, Johnny Pate.[20]

Butler was replaced by Fred Cash, a returning original Roosters member, and Mayfield became lead singer, frequently composing for the band, starting with "Gypsy Woman", a Top 20 Pop hit. Their hit "Amen" (Top 10), an updated version of an old gospel tune, was included in the soundtrack of the 1963 United Artists film Lilies of the Field, which starred Sidney Poitier. The Impressions reached the height of their popularity in the mid-to-late-'60s with a string of Mayfield compositions that included "Keep On Pushing," "People Get Ready", "It's All Right" (Top 10), the up-tempo "Talking about My Baby"(Top 20) and "Woman's Got Soul".

He formed his own label, Curtom Records in Chicago in 1968 and the Impressions joined him to continue their run of hits including "Fool For You," "This is My Country", "Choice Of Colors" and "Check Out Your Mind". Mayfield had written much of the soundtrack of the Civil Rights Movement in the early 1960s, but by the end of the decade, he was a pioneering voice in the black pride movement along with James Brown and Sly Stone. Mayfield's "We're a Winner" was their last major hit for ABC. Reaching number 14 on Billboard's pop chart and number one on the R&B chart, it became an anthem of the black power and black pride movements when it was released in late 1967,[21][22][23] much as his earlier "Keep on Pushing" (whose title is quoted in the lyrics of "We're a Winner" and also in "Move On Up") had been an anthem for Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement.[24]

Mayfield was a prolific songwriter in Chicago even outside his work for the Impressions, writing and producing scores of hits for many other artists. He also owned the Mayfield and Windy C labels which were distributed by Cameo-Parkway, and was a partner in the Curtom (first independent, then distributed by Buddah then Warner Bros and finally RSO) and Thomas labels (first independent, then distributed by Atlantic, then independent again and finally Buddah).

Among Mayfield's greatest songwriting successes were three hits that he wrote for Jerry Butler on Vee Jay ("He Will Break Your Heart", "Find Another Girl" and "I'm A-Tellin' You"). His harmony vocals are very prominent. He also had great success writing and arranging Jan Bradley's "Mama Didn't Lie". Starting in 1963, he was heavily involved in writing and arranging for OKeh Records (with Carl Davis producing), which included hits by Major Lance such as "Um, Um, Um, Um, Um, Um" and "The Monkey Time",[25] as well as Walter Jackson, Billy Butler and the Artistics. This arrangement ran through 1965.

Solo career

In 1970, Mayfield left the Impressions and began a solo career. Curtom released many of Mayfield's 1970s records, as well as records by the Impressions, Leroy Hutson, the Five Stairsteps, the Staples Singers, Mavis Staples, Linda Clifford, Natural Four, The Notations and Baby Huey and the Babysitters. Gene Chandler and Major Lance, who had worked with Mayfield during the 1960s, also signed for short stays at Curtom. Many of the label's recordings were produced by Mayfield.

Mayfield's first solo album, Curtis, was released in 1970, and hit the top 20, as well as being a critical success. It pre-dated Marvin Gaye's album, What's Going On, to which it has been compared in addressing social change.[26] The commercial and critical peak of his solo career came with Super Fly, the soundtrack to the blaxploitation Super Fly film, which topped the Billboard Top LPs chart and sold more than 12 million copies.[13] Unlike the soundtracks to other blaxploitation films (most notably Isaac Hayes' score for Shaft), which glorified the ghetto excesses of the characters, Mayfield's lyrics consisted of hard-hitting commentary on the state of affairs in black, urban ghettos at the time, as well as direct criticisms of several characters in the film. Bob Donat wrote in Rolling Stone magazine in 1972 that while the film's message "was diluted by schizoid cross-purposes" because it "glamorizes machismo-cocaine consciousness... the anti-drug message on [Mayfield's soundtrack] is far stronger and more definite than in the film."[27] Because of the tendency of these blaxploitation films to glorify the criminal life of dealers and pimps to target a mostly black lower class audience, Mayfield's album set this movie apart. With songs like "Freddie's Dead", a song that focuses on the demise of Freddie, a junkie that was forced into "pushin' dope for the man" because of a debt that he owed to his dealer, and "Pusherman", a song that reveals how many people in the ghetto fell victim to drug abuse, and therefore became dependent upon their dealers, Mayfield illuminated a darker side of life in the ghetto that these blaxploitation films often failed to criticize. However, although Mayfield's soundtrack criticized the glorification of dealers and pimps, he in no way denied that this glorification was occurring. When asked about the subject matter of these films he was quoted stating "I don't see why people are complaining about the subject of these films", and "The way you clean up the films is by cleaning up the streets."[28]

Along with What's Going On and Stevie Wonder's Innervisions, this album ushered in a new socially conscious, funky style of popular soul music. The single releases "Freddie's Dead" and "Super Fly" each sold more than one million copies, and were awarded gold discs by the R.I.A.A.[29]

Super Fly brought success that resulted in Mayfield being tapped for additional soundtracks, some of which he wrote and produced while having others perform the vocals. Gladys Knight & the Pips recorded Mayfield's soundtrack for Claudine in 1974,[30] while Aretha Franklin recorded the soundtrack for Sparkle in 1976.[31] Mayfield also worked with The Staples Singers on the soundtrack for the 1975 film Let's Do It Again,[13] and teamed up with Mavis Staples exclusively on the 1977 film soundtrack A Piece of the Action (both movies were part of a trilogy of films that featured the acting and comedic exploits of Bill Cosby and Sidney Poitier and were directed by Poitier).

In 1973 Mayfield released the anti-war album Back to the World, a concept album that dealt with the social aftermath of the Vietnam War and criticized the United States' involvement in wars across the planet.[32] One of Mayfield's most successful funk-disco meldings was the 1977 hit "Do Do Wap is Strong in Here" from his soundtrack to the Robert M. Young film of Miguel Piñero's play Short Eyes. In his 2003 biography of Curtis Mayfield, People Never Give Up, author Peter Burns noted that Mayfield has 140 songs in the Curtom vaults. Burns indicated that the songs were maybe already completed or in the stages of completion, so that they could then be released commercially. These recordings include "The Great Escape", "In The News", "Turn up the Radio", "What's The Situation?" and one recording labelled "Curtis at Montreux Jazz Festival 87".Two other albums featuring Curtis Mayfield present in the Curtom vaults and as yet unissued are a 1982/83 live recording titled "25th Silver Anniversary" (which features performances by Mayfield, the Impressions, and Jerry Butler) and a live performance, recorded in September 1966 by the Impressions titled Live at the Club Chicago.

In 1982, Mayfield decided to move to Atlanta with his family, closing down his recording operation in Chicago.[13] The label had gradually reduced in size in its final two years or so with releases on the main RSO imprint and Curtom credited as the production company. Mayfield continued to record occasionally, keeping the Curtom name alive for a few more years, and to tour worldwide. Mayfield's song "(Don't Worry) If There's a Hell Below, We're All Going to Go" has been included as an entrance song on every episode of the drama series The Deuce. The Deuce tells of the germination of the sex-trade industry in the heart of New York's Times Square in the 1970s. Mayfield's career began to slow down during the 1980s.

In later years, Mayfield's music was included in the movies I'm Gonna Git You Sucka, Hollywood Shuffle, Friday (though not on the soundtrack album), Bend It Like Beckham, The Hangover Part II and Short Eyes, where he had a cameo role as a prisoner.[33]

Social activism

"His most affecting songs carried the optimism and conviction of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s most celebrated sermons. His music was a major influence on many of today's most influential rap and hip-hop stars, from Lauryn Hill to Public Enemy."

— Los Angeles Times Pop Music Critic Robert Hilburn (1999)[13]

Mayfield sang openly about civil rights and black pride,[34] and was known for introducing social consciousness into African-American music.[13] Having been raised in the Cabrini-Green projects of Chicago, he witnessed many of the tragedies of the urban ghetto first hand, and was quoted saying "With everything I saw on the streets as a young black kid, it wasn't hard during the later fifties and sixties for me to write my heartfelt way of how I visualized things, how I thought things ought to be."

Following the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, his group the Impressions produced music that became the soundtrack to a summer of revolution. It is even said that "Keep On Pushing" became the number one sing along during the Freedom Rides.[35] Black students sang their songs as they marched to jail or protested outside their universities, while King often used "Keep On Pushing", "People Get Ready" and "We're A Winner" because of their ability to motivate and inspire marchers. Mayfield had quickly become a civil rights hero with his ability to inspire hope and courage.[36]

Mayfield was unique in his ability to fuse relevant social commentary with melodies and lyrics that instilled a hopefulness for a better future in his listeners. He wrote and recorded the soundtrack to the 1972 blaxploitation film Super Fly with the help of producer Johnny Pate. The soundtrack for Super Fly is regarded as an all-time great body of work that captured the essence of life in the ghetto while criticizing the tendency of young people to glorify the "glamorous" lifestyles of drug dealers and pimps, and illuminating the dark realities of drugs, addiction, and exploitation.[37]

Mayfield, along with several other soul and funk musicians, spread messages of hope in the face of oppression, pride in being a member of the black race and gave courage to a generation of people who were demanding their human rights. He has been compared to Martin Luther King Jr. for making a lasting impact in the civil rights struggle with his inspirational music.[13][35] By the end of the decade Mayfield was a pioneering voice in the black pride movement, along with James Brown and Sly Stone. Paving the way for a future generation of rebel thinkers, Mayfield paid the price, artistically and commercially, for his politically charged music. Mayfield's "Keep On Pushing" was actually banned from several radio stations, including WLS in his hometown of Chicago.[38] Regardless of the persistent radio bans and loss of revenue, he continued his quest for equality right until his death.

Mayfield was also a descriptive social commentator. As the influx of drugs ravaged through black America in the late 1960s and 1970s his bittersweet descriptions of the ghetto would serve as warnings to the impressionable. "Freddie's Dead" is a graphic tale of street life,[36] while "Pusherman" revealed the role of drug dealers in the urban ghettos.

Personal life

Mayfield was married twice.[14] He had 10 children from different relationships. At the time of his death he was married to Altheida Mayfield. Together they had six children.[39]