The discount is regular shipping price for the first item and just 50 cents for each additional item!

Please be sure to request a combined invoice before you make your payment. Thank you.

I have a lot of things that I don't need. I thought it would be a good time to downsize my world, and hopefully make some money too.

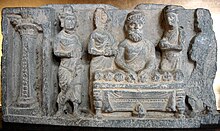

This is a vintage style bronze or maybe brass Quan Yin or maybe Shiva, it may even be buddha (not sure) statue! It is really chunky and really nice.

It has a really good weight to it. I think it would be perfect for a small home altar, or sometimes I see these on the dashboards of cars.

I'm not sure what she was going to do with it, but I found it with a bunch of jewelry at an estate sale.

I am not sure how old it is, or what it is worth really. It is brass colored metal, and it's really cute!

It measures 38 mm by 28 mm by 13 mm and it is really cool. I love it , but I need to make money, so there you go.

I will put a Wikipedia entry about this below.

If you have anymore questions, just ask. I am sure I am leaving something out.

Gautama Buddha

| Gautama Buddha | |

|---|---|

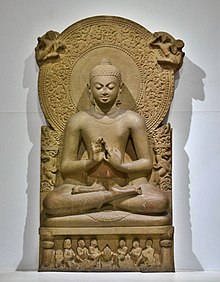

A statue of the Buddha from Sarnath, 4th century CE

|

|

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Other names | Siddhartha Gautama, Shakyamuni |

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 563 BCE or c. 480 BCE[1][2] Lumbini, Shakya Republic (according to Buddhist tradition)[note 1] |

| Died | c. 483 BCE or c. 400 BCE (aged 80) Kushinagar, Malla Republic (according to Buddhist tradition)[note 2] |

| Parents |

|

| Senior posting | |

| Predecessor | Kassapa Buddha |

| Successor | Maitreya |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Gautama Buddha | |||

| Chinese name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 佛陀 | ||

|

|||

| Burmese name | |||

| Burmese | ဂေါတမ ဗုဒ္ဓ | ||

| Vietnamese name | |||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Tất-đạt-đa Cồ-đàm | ||

| Thai name | |||

| Thai | พระพุทธเจ้า | ||

| Korean name | |||

| Hangul | 부처 | ||

|

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 釈迦 | ||

| Hiragana | しゃか | ||

|

|||

| Bengali name | |||

| Bengali | গৌতম বুদ্ধ | ||

| Nepali name | |||

| Nepali | गौतम बुद्ध | ||

| Sanskrit name | |||

| Sanskrit | गौतम बुद्ध | ||

Gautama Buddha, also known as Siddhārtha Gautama, Shakyamuni Buddha,[note 3] or simply the Buddha, after the title of Buddha, was an ascetic (śramaṇa) and sage,[3] on whose teachings Buddhism was founded.[web 2] He is believed to have lived and taught mostly in the eastern part of ancient India sometime between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE.[4][note 4]

Gautama taught a Middle Way between sensual indulgence and the severe asceticism found in the śramaṇa movement[5] common in his region. He later taught throughout other regions of eastern India such as Magadha and Kosala.[4][6]

Gautama is the primary figure in Buddhism. He is recognized by Buddhists as an enlightened or divine[7] teacher who attained full Buddhahood, and shared his insights to help sentient beings end rebirth and suffering. Accounts of his life, discourses, and monastic rules are believed by Buddhists to have been summarized after his death and memorized by his followers. Various collections of teachings attributed to him were passed down by oral tradition and first committed to writing about 400 years later.

Contents

Historical Siddhārtha Gautama

Scholars are hesitant to make unqualified claims about the historical facts of the Buddha's life. Most accept that he lived, taught and founded a monastic order during the Mahajanapada era during the reign of Bimbisara (c. 558 – c. 491 BCE),[8][9] the ruler of the Magadha empire, and died during the early years of the reign of Ajasattu, who was the successor of Bimbisara, thus making him a younger contemporary of Mahavira, the Jain tirthankara.[10][11] Apart from the Vedic Brahmins, the Buddha's lifetime coincided with the flourishing of influential Śramaṇa schools of thought like Ājīvika, Cārvāka, Jainism, and Ajñana.[12] Brahmajala Sutta records sixty-two such schools of thought. It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahavira (referred to as 'Nigantha Nataputta' in Pali Canon)[13]), Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana, and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, as recorded in Samaññaphala Sutta, whose viewpoints the Buddha most certainly must have been acquainted with.[14][15][note 5] Indeed, Sariputta and Moggallāna, two of the foremost disciples of the Buddha, were formerly the foremost disciples of Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, the skeptic;[16] and the Pali canon frequently depicts Buddha engaging in debate with the adherents of rival schools of thoughts. Thus, Buddha was just one of the many śramaṇa philosophers of that time.[17] There is also evidence to suggest that the two masters, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta, were indeed historical figures and they most probably taught Buddha two different forms of meditative techniques.[18] While the general sequence of "birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death" is widely accepted,[19][page needed] there is less consensus on the veracity of many details contained in traditional biographies.[20][21]

The times of Gautama's birth and death are uncertain. Most historians in the early 20th century dated his lifetime as circa 563 BCE to 483 BCE.[1][22] More recently his death is dated later, between 411 and 400 BCE, while at a symposium on this question held in 1988,[23][24][25] the majority of those who presented definite opinions gave dates within 20 years either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha's death.[1][26][note 4] These alternative chronologies, however, have not yet been accepted by all historians.[31][32][note 6]

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhārtha Gautama was born into the Shakya clan, a community that was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the eastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE.[34] It was either a small republic, or an oligarchy, and his father was an elected chieftain, or oligarch.[34] According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini, now in modern-day Nepal, and raised in the Shakya capital of Kapilvastu, which may have been either in what is present day Tilaurakot, Nepal or Piprahwa, India.[note 1] He obtained his enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, gave his first sermon in Sarnath, and died in Kushinagar.

No written records about Gautama were found from his lifetime or some centuries thereafter. One Edict of Asoka, who reigned from circa 269 BCE to 232 BCE, commemorates the Emperor's pilgrimage to the Buddha's birthplace in Lumbini. Another one of his edicts mentions the titles of several Dhamma texts, establishing the existence of a written Buddhist tradition at least by the time of the Maurya era. These texts may be the precursor of the Pāli Canon.[48][web 10] [note 7] The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts are the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, reported to have been found in or around Haḍḍa near Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan and now preserved in the British Library. They are written in the Gāndhārī language using the Kharosthi script on twenty-seven birch bark manuscripts and date from the first century BCE to the third century CE.[web 11]

Traditional biographies

Biographical sources

The sources for the life of Siddhārtha Gautama are a variety of different, and sometimes conflicting, traditional biographies. These include the Buddhacarita, Lalitavistara Sūtra, Mahāvastu, and the Nidānakathā.[49] Of these, the Buddhacarita[50][51][52] is the earliest full biography, an epic poem written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa in the first century CE.[53] The Lalitavistara Sūtra is the next oldest biography, a Mahāyāna/Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[54] The Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda tradition is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[54] The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and is entitled the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra,[55] and various Chinese translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE. The Nidānakathā is from the Theravada tradition in Sri Lanka and was composed in the 5th century by Buddhaghoṣa.[56]

From canonical sources, the Jataka tales, the Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123) which include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full biographies. The Jātakas retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts.[57] The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Achariyabhuta Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama's birth, such as the bodhisattva's descent from the Tuṣita Heaven into his mother's womb.

Nature of traditional depictions

In the earliest Buddhists texts, the nikāyas and āgamas, the Buddha is not depicted as possessing omniscience (sabbaññu)[58] nor is he depicted as being an eternal transcendent (lokottara) being. According to Bhikkhu Analayo, ideas of the Buddha's omniscience (along with an increasing tendency to deify him and his biography) are found only later, in the Mahayana sutras and later Pali commentaries or texts such as the Mahāvastu.[58] In the Sandaka Sutta, the Buddha's disciple Ananda outlines an argument against the claims of teachers who say they are all knowing [web 12] while in the Tevijjavacchagotta Sutta the Buddha himself states that he has never made a claim to being omniscient, instead he claimed to have the "higher knowledges" (abhijñā).[59] The earliest biographical material from the Pali Nikayas focuses on the Buddha's life as a śramaṇa, his search for enlightenment under various teachers such as Alara Kalama and his forty five year career as a teacher.[web 13]

Traditional biographies of Gautama generally include numerous miracles, omens, and supernatural events. The character of the Buddha in these traditional biographies is often that of a fully transcendent (Skt. lokottara) and perfected being who is unencumbered by the mundane world. In the Mahāvastu, over the course of many lives, Gautama is said to have developed supra-mundane abilities including: a painless birth conceived without intercourse; no need for sleep, food, medicine, or bathing, although engaging in such "in conformity with the world"; omniscience, and the ability to "suppress karma".[60] Nevertheless, some of the more ordinary details of his life have been gathered from these traditional sources. In modern times there has been an attempt to form a secular understanding of Siddhārtha Gautama's life by omitting the traditional supernatural elements of his early biographies.

Andrew Skilton writes that the Buddha was never historically regarded by Buddhist traditions as being merely human:

It is important to stress that, despite modern Theravada teachings to the contrary (often a sop to skeptical Western pupils), he was never seen as being merely human. For instance, he is often described as having the thirty-two major and eighty minor marks or signs of a mahāpuruṣa, "superman"; the Buddha himself denied that he was either a man or a god; and in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta he states that he could live for an aeon were he asked to do so.[61]

The ancient Indians were generally unconcerned with chronologies, being more focused on philosophy. Buddhist texts reflect this tendency, providing a clearer picture of what Gautama may have taught than of the dates of the events in his life. These texts contain descriptions of the culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha's time the earliest period in Indian history for which significant accounts exist.[62] British author Karen Armstrong writes that although there is very little information that can be considered historically sound, we can be reasonably confident that Siddhārtha Gautama did exist as a historical figure.[63] Michael Carrithers goes a bit further by stating that the most general outline of "birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death" must be true.[19]

Biography

Conception and birth

The Buddhist tradition regards Lumbini, in present-day Nepal to be the birthplace of the Buddha.[64][note 1] He grew up in Kapilavastu.[note 1] The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[65] It may have been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, present-day India,[43] or Tilaurakot, present-day Nepal.[66] Both places belonged to the Sakya territory, and are located only 15 miles apart.[66]

Gautama was born as a Kshatriya,[67][note 9] the son of Śuddhodana, "an elected chief of the Shakya clan",[4] whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha's lifetime. Gautama was the family name. His mother, Maya (Māyādevī), Suddhodana's wife, was a Koliyan princess. Legend has it that, on the night Siddhartha was conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant with six white tusks entered her right side,[69][70] and ten months later[71] Siddhartha was born. As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen Maya became pregnant, she left Kapilvastu for her father's kingdom to give birth. However, her son is said to have been born on the way, at Lumbini, in a garden beneath a sal tree.

The day of the Buddha's birth is widely celebrated in Theravada countries as Vesak.[72] Buddha's Birthday is called Buddha Purnima in Nepal, Bangladesh, and India as he is believed to have been born on a full moon day. Various sources hold that the Buddha's mother died at his birth, a few days or seven days later. The infant was given the name Siddhartha (Pāli: Siddhattha), meaning "he who achieves his aim". During the birth celebrations, the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode and announced that the child would either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great sadhu.[73] By traditional account,[which?] this occurred after Siddhartha placed his feet in Asita's hair and Asita examined the birthmarks. Suddhodana held a naming ceremony on the fifth day, and invited eight Brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave a dual prediction that the baby would either become a great king or a great holy man.[73] Kondañña, the youngest, and later to be the first arhat other than the Buddha, was reputed to be the only one who unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.[74]

While later tradition and legend characterized Śuddhodana as a hereditary monarch, the descendant of the Suryavansha (Solar dynasty) of Ikṣvāku (Pāli: Okkāka), many scholars think that Śuddhodana was the elected chief of a tribal confederacy.

Early texts suggest that Gautama was not familiar with the dominant religious teachings of his time until he left on his religious quest, which is said to have been motivated by existential concern for the human condition.[75] The state of the Shakya clan was not a monarchy, and seems to have been structured either as an oligarchy, or as a form of republic.[76] The more egalitarian gana-sangha form of government, as a political alternative to the strongly hierarchical kingdoms, may have influenced the development of the śramanic Jain and Buddhist sanghas, where monarchies tended toward Vedic Brahmanism.[77]

Early life and marriage

Siddhartha was brought up by his mother's younger sister, Maha Pajapati.[78] By tradition, he is said to have been destined by birth to the life of a prince, and had three palaces (for seasonal occupation) built for him. Although more recent scholarship doubts this status, his father, said to be King Śuddhodana, wishing for his son to be a great king, is said to have shielded him from religious teachings and from knowledge of human suffering.

When he reached the age of 16, his father reputedly arranged his marriage to a cousin of the same age named Yaśodharā (Pāli: Yasodharā). According to the traditional account,[which?] she gave birth to a son, named Rāhula. Siddhartha is said to have spent 29 years as a prince in Kapilavastu. Although his father ensured that Siddhartha was provided with everything he could want or need, Buddhist scriptures say that the future Buddha felt that material wealth was not life's ultimate goal.[78]

Renunciation and ascetic life

At the age of 29 Siddhartha left his palace to meet his subjects. Despite his father's efforts to hide from him the sick, aged and suffering, Siddhartha was said to have seen an old man. When his charioteer Channa explained to him that all people grew old, the prince went on further trips beyond the palace. On these he encountered a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic. These depressed him, and he initially strove to overcome aging, sickness, and death by living the life of an ascetic.[79]

Accompanied by Channa and riding his horse Kanthaka, Gautama quit his palace for the life of a mendicant. It's said that, "the horse's hooves were muffled by the gods"[80] to prevent guards from knowing of his departure.

Gautama initially went to Rajagaha and began his ascetic life by begging for alms in the street. After King Bimbisara's men recognised Siddhartha and the king learned of his quest, Bimbisara offered Siddhartha the throne. Siddhartha rejected the offer, but promised to visit his kingdom of Magadha first, upon attaining enlightenment.

He left Rajagaha and practised under two hermit teachers of yogic meditation.[81][82][83] After mastering the teachings of Alara Kalama (Skr. Ārāḍa Kālāma), he was asked by Kalama to succeed him. However, Gautama felt unsatisfied by the practice, and moved on to become a student of yoga with Udaka Ramaputta (Skr. Udraka Rāmaputra).[84] With him he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness, and was again asked to succeed his teacher. But, once more, he was not satisfied, and again moved on.[85]

Siddhartha and a group of five companions led by Kaundinya are then said to have set out to take their austerities even further. They tried to find enlightenment through deprivation of worldly goods, including food, practising self-mortification. After nearly starving himself to death by restricting his food intake to around a leaf or nut per day, he collapsed in a river while bathing and almost drowned. Siddhartha was rescued by a village girl named Sujata and she gave him some payasam (a pudding made from milk and jaggery) after which Siddhartha got back some energy. Siddhartha began to reconsider his path. Then, he remembered a moment in childhood in which he had been watching his father start the season's ploughing. He attained a concentrated and focused state that was blissful and refreshing, the jhāna.

Awakening

According to the early Buddhist texts,[web 14] after realizing that meditative dhyana was the right path to awakening, but that extreme asceticism didn't work, Gautama discovered what Buddhists call the Middle Way[web 14]—a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification, or the Noble Eightfold Path, as described in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, which is regarded as the first discourse of the Buddha.[web 14] In a famous incident, after becoming starved and weakened, he is said to have accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata.[web 15] Such was his emaciated appearance that she wrongly believed him to be a spirit that had granted her a wish.[web 15]

Following this incident, Gautama was famously seated under a pipal tree—now known as the Bodhi tree—in Bodh Gaya, India, when he vowed never to arise until he had found the truth.[86] Kaundinya and four other companions, believing that he had abandoned his search and become undisciplined, left. After a reputed 49 days of meditation, at the age of 35, he is said to have attained Enlightenment,[86][web 16] and became known as the Buddha or "Awakened One" ("Buddha" is also sometimes translated as "The Enlightened One").

According to some sutras of the Pali canon, at the time of his awakening he realized complete insight into the Four Noble Truths, thereby attaining liberation from samsara, the endless cycle of rebirth, suffering and dying again.[87][88][web 17] According to scholars, this story of the awakening and the stress on "liberating insight" is a later development in the Buddhist tradition, where the Buddha may have regarded the practice of dhyana as leading to Nirvana and moksha.[89][90][87][note 10]

Nirvana is the extinguishing of the "fires" of desire, hatred, and ignorance, that keep the cycle of suffering and rebirth going.[91] Nirvana is also regarded as the "end of the world", in that no personal identity or boundaries of the mind remain.[citation needed] In such a state, a being is said to possess the Ten Characteristics, belonging to every Buddha.[citation needed]

According to a story in the Āyācana Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya VI.1) — a scripture found in the Pāli and other canons — immediately after his awakening, the Buddha debated whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others. He was concerned that humans were so overpowered by ignorance, greed and hatred that they could never recognise the path, which is subtle, deep and hard to grasp. However, in the story, Brahmā Sahampati convinced him, arguing that at least some will understand it. The Buddha relented, and agreed to teach.

Formation of the sangha

After his awakening, the Buddha met Taphussa and Bhallika — two merchant brothers from the city of Balkh in what is currently Afghanistan — who became his first lay disciples. It is said that each was given hairs from his head, which are now claimed to be enshrined as relics in the Shwe Dagon Temple in Rangoon, Burma. The Buddha intended to visit Asita, and his former teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta, to explain his findings, but they had already died.

He then travelled to the Deer Park near Varanasi (Benares) in northern India, where he set in motion what Buddhists call the Wheel of Dharma by delivering his first sermon to the five companions with whom he had sought enlightenment. Together with him, they formed the first saṅgha: the company of Buddhist monks.

All five become arahants, and within the first two months, with the conversion of Yasa and fifty four of his friends, the number of such arahants is said to have grown to 60. The conversion of three brothers named Kassapa followed, with their reputed 200, 300 and 500 disciples, respectively. This swelled the sangha to more than 1,000.

Travels and teaching

For the remaining 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have traveled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and southern Nepal, teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to servants, murderers such as Angulimala, and cannibals such as Alavaka.[92] Although the Buddha's language remains unknown, it's likely that he taught in one or more of a variety of closely related Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, of which Pali may be a standardization.

The sangha traveled through the subcontinent, expounding the dharma. This continued throughout the year, except during the four months of the Vassa rainy season when ascetics of all religions rarely traveled. One reason was that it was more difficult to do so without causing harm to animal life. At this time of year, the sangha would retreat to monasteries, public parks or forests, where people would come to them.

The first vassana was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was formed. After this, the Buddha kept a promise to travel to Rajagaha, capital of Magadha, to visit King Bimbisara. During this visit, Sariputta and Maudgalyayana were converted by Assaji, one of the first five disciples, after which they were to become the Buddha's two foremost followers. The Buddha spent the next three seasons at Veluvana Bamboo Grove monastery in Rajagaha, capital of Magadha.

Upon hearing of his son's awakening, Suddhodana sent, over a period, ten delegations to ask him to return to Kapilavastu. On the first nine occasions, the delegates failed to deliver the message, and instead joined the sangha to become arahants. The tenth delegation, led by Kaludayi, a childhood friend of Gautama's (who also became an arahant), however, delivered the message.

Now two years after his awakening, the Buddha agreed to return, and made a two-month journey by foot to Kapilavastu, teaching the dharma as he went. At his return, the royal palace prepared a midday meal, but the sangha was making an alms round in Kapilavastu. Hearing this, Suddhodana approached his son, the Buddha, saying:

"Ours is the warrior lineage of Mahamassata, and not a single warrior has gone seeking alms."

The Buddha is said to have replied:

"That is not the custom of your royal lineage. But it is the custom of my Buddha lineage. Several thousands of Buddhas have gone by seeking alms."

Buddhist texts say that Suddhodana invited the sangha into the palace for the meal, followed by a dharma talk. After this he is said to have become a sotapanna. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha. The Buddha's cousins Ananda and Anuruddha became two of his five chief disciples. At the age of seven, his son Rahula also joined, and became one of his ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined and became an arahant.

Of the Buddha's disciples, Sariputta, Maudgalyayana, Mahakasyapa, Ananda and Anuruddha are believed to have been the five closest to him. His ten foremost disciples were reputedly completed by the quintet of Upali, Subhoti, Rahula, Mahakaccana and Punna.

In the fifth vassana, the Buddha was staying at Mahavana near Vesali when he heard news of the impending death of his father. He is said to have gone to Suddhodana and taught the dharma, after which his father became an arahant.

The king's death and cremation was to inspire the creation of an order of nuns. Buddhist texts record that the Buddha was reluctant to ordain women. His foster mother Maha Pajapati, for example, approached him, asking to join the sangha, but he refused. Maha Pajapati, however, was so intent on the path of awakening that she led a group of royal Sakyan and Koliyan ladies, which followed the sangha on a long journey to Rajagaha. In time, after Ananda championed their cause, the Buddha is said to have reconsidered and, five years after the formation of the sangha, agreed to the ordination of women as nuns. He reasoned that males and females had an equal capacity for awakening. But he gave women additional rules (Vinaya) to follow.

Mahaparinirvana

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon reach Parinirvana, or the final deathless state, and abandon his earthly body. After this, the Buddha ate his last meal, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ānanda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the last meal for a Buddha.[web 18] Mettanando and von Hinüber argue that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a symptom of old age, rather than food poisoning.[93][web 19]

The precise contents of the Buddha's final meal are not clear, due to variant scriptural traditions and ambiguity over the translation of certain significant terms; the Theravada tradition generally believes that the Buddha was offered some kind of pork, while the Mahayana tradition believes that the Buddha consumed some sort of truffle or other mushroom. These may reflect the different traditional views on Buddhist vegetarianism and the precepts for monks and nuns.

Waley suggests that Theravadins would take suukaramaddava (the contents of the Buddha's last meal), which can translate literally as pig-soft, to mean "soft flesh of a pig" or "pig's soft-food", that is, after Neumann, a soft food favoured by pigs, assumed to be a truffle. He argues (also after Neumann) that as "(p)lant names tend to be local and dialectical", as there are several plants known to have suukara- (pig) as part of their names,[note 11] and as Pali Buddhism developed in an area remote from the Buddha's death, suukaramaddava could easily have been a type of plant whose local name was unknown to those in Pali regions. Specifically, local writers writing soon after the Buddha's death knew more about their flora than Theravadin commentator Buddhaghosa who lived hundreds of years and hundreds of kilometres remote in time and space from the events described. Unaware that it may have been a local plant name and with no Theravadin prohibition against eating animal flesh, Theravadins would not have questioned the Buddha eating meat and interpreted the term accordingly.[94]

According to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha died at Kuśināra (present-day Kushinagar, India), which became a pilgrimage center.[95] Ananda protested the Buddha's decision to enter Parinirvana in the abandoned jungles of Kuśināra of the Malla kingdom. The Buddha, however, is said to have reminded Ananda how Kushinara was a land once ruled by a righteous wheel-turning king and the appropriate place for him to die.[96]

The Buddha then asked all the attendant Bhikkhus to clarify any doubts or questions they had and cleared them all in a way which others could not do. They had none. According to Buddhist scriptures, he then finally entered Parinirvana. The Buddha's final words are reported to have been: "All composite things (Saṅkhāra) are perishable. Strive for your own liberation with diligence" (Pali: 'vayadhammā saṅkhārā appamādena sampādethā'). His body was cremated and the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present. For example, The Temple of the Tooth or "Dalada Maligawa" in Sri Lanka is the place where what some believe to be the relic of the right tooth of Buddha is kept at present.

According to the Pāli historical chronicles of Sri Lanka, the Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa, the coronation of Emperor Aśoka (Pāli: Asoka) is 218 years after the death of the Buddha. According to two textual records in Chinese (十八部論 and 部執異論), the coronation of Emperor Aśoka is 116 years after the death of the Buddha. Therefore, the time of Buddha's passing is either 486 BCE according to Theravāda record or 383 BCE according to Mahayana record. However, the actual date traditionally accepted as the date of the Buddha's death in Theravāda countries is 544 or 545 BCE, because the reign of Emperor Aśoka was traditionally reckoned to be about 60 years earlier than current estimates. In Burmese Buddhist tradition, the date of the Buddha's death is 13 May 544 BCE.[97] whereas in Thai tradition it is 11 March 545 BCE.[98]

At his death, the Buddha is famously believed to have told his disciples to follow no leader. Mahakasyapa was chosen by the sangha to be the chairman of the First Buddhist Council, with the two chief disciples Maudgalyayana and Sariputta having died before the Buddha.

While in the Buddha's days he was addressed by the very respected titles Buddha, Shākyamuni, Shākyasimha, Bhante and Bho, he was known after his parinirvana as Arihant, Bhagavā/Bhagavat/Bhagwān, Mahāvira,[99] Jina/Jinendra, Sāstr, Sugata, and most popularly in scriptures as Tathāgata.

Relics

After his death, Buddha's cremation relics were divided amongst 8 royal families and his disciples; centuries later they would be enshrined by King Ashoka into 84,000 stupas.[web 20][100] Many supernatural legends surround the history of alleged relics as they accompanied the spread of Buddhism and gave legitimacy to rulers.

Physical characteristics

An extensive and colorful physical description of the Buddha has been laid down in scriptures. A kshatriya by birth, he had military training in his upbringing, and by Shakyan tradition was required to pass tests to demonstrate his worthiness as a warrior in order to marry.[citation needed] He had a strong enough body to be noticed by one of the kings and was asked to join his army as a general.[citation needed] He is also believed by Buddhists to have "the 32 Signs of the Great Man".

The Brahmin Sonadanda described him as "handsome, good-looking, and pleasing to the eye, with a most beautiful complexion. He has a godlike form and countenance, he is by no means unattractive." (D, I:115)

"It is wonderful, truly marvellous, how serene is the good Gotama's appearance, how clear and radiant his complexion, just as the golden jujube in autumn is clear and radiant, just as a palm-tree fruit just loosened from the stalk is clear and radiant, just as an adornment of red gold wrought in a crucible by a skilled goldsmith, deftly beaten and laid on a yellow-cloth shines, blazes and glitters, even so, the good Gotama's senses are calmed, his complexion is clear and radiant." (A, I:181)

A disciple named Vakkali, who later became an arahant, was so obsessed by the Buddha's physical presence that the Buddha is said to have felt impelled to tell him to desist, and to have reminded him that he should know the Buddha through the Dhamma and not through physical appearances.

Although there are no extant representations of the Buddha in human form until around the 1st century CE (see Buddhist art), descriptions of the physical characteristics of fully enlightened buddhas are attributed to the Buddha in the Digha Nikaya's Lakkhaṇa Sutta (D, I:142).[101] In addition, the Buddha's physical appearance is described by Yasodhara to their son Rahula upon the Buddha's first post-Enlightenment return to his former princely palace in the non-canonical Pali devotional hymn, Narasīha Gāthā ("The Lion of Men").[web 21]

Among the 32 main characteristics it is mentioned that Buddha has blue eyes.[102]

Nine virtues

Recollection of nine virtues attributed to the Buddha is a common Buddhist meditation and devotional practice called Buddhānusmṛti. The nine virtues are also among the 40 Buddhist meditation subjects. The nine virtues of the Buddha appear throughout the Tipitaka,[web 22] and include:

- Buddho – Awakened

- Sammasambuddho – Perfectly self-awakened

- Vijja-carana-sampano – Endowed with higher knowledge and ideal conduct.

- Sugato – Well-gone or Well-spoken.

- Lokavidu – Wise in the knowledge of the many worlds.

- Anuttaro Purisa-damma-sarathi – Unexcelled trainer of untrained people.

- Satthadeva-Manussanam – Teacher of gods and humans.

- Bhagavathi – The Blessed one

- Araham – Worthy of homage. An Arahant is "one with taints destroyed, who has lived the holy life, done what had to be done, laid down the burden, reached the true goal, destroyed the fetters of being, and is completely liberated through final knowledge."

Teachings

Use of Brahmanical motifs

In the Pali Canon, the Buddha uses many Brahmanical devices. For example, in Samyutta Nikaya 111, Majjhima Nikaya 92 and Vinaya i 246 of the Pali Canon, the Buddha praises the Agnihotra as the foremost sacrifice and the Gayatri mantra as the foremost meter:

aggihuttamukhā yaññā sāvittī chandaso mukham.

Sacrifices have the agnihotra as foremost; of meter the foremost is the Sāvitrī.[103]

Tracing the oldest teachings

Information of the oldest teachings may be obtained by analysis of the oldest texts. One method to obtain information on the oldest core of Buddhism is to compare the oldest extant versions of the Theravadin Pali Canon and other texts.[note 12] The reliability of these sources, and the possibility to draw out a core of oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute.[106][107][108][109] According to Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.[104][note 13]

According to Schmithausen, three positions held by scholars of Buddhism can be distinguished:[112]

- "Stress on the fundamental homogeneity and substantial authenticity of at least a considerable part of the Nikayic materials;"[note 14][note 15], from the oldest extant texts a common kernel can be drawn out.[113] According to Warder, c.q. his publisher: "This kernel of doctrine is presumably common Buddhism of the period before the great schisms of the fourth and third centuries BC. It may be substantially the Buddhism of the Buddha himself, although this cannot be proved: at any rate it is a Buddhism presupposed by the schools as existing about a hundred years after the parinirvana of the Buddha, and there is no evidence to suggest that it was formulated by anyone else than the Buddha and his immediate followers"[113] and Richard Gombrich.[114] Richard Gombrich: "I have the greatest difficulty in accepting that the main edifice is not the work of a single genius. By "the main edifice" I mean the collections of the main body of sermons, the four Nikāyas, and of the main body of monastic rules."[109]

- "Scepticism with regard to the possibility of retrieving the doctrine of earliest Buddhism;"[note 16][note 17]

- "Cautious optimism in this respect."[note 18]

Dhyana and insight

A core problem in the study of early Buddhism is the relation between dhyana and insight.[107][106][109] Schmithausen notes that the mention of the four noble truths as constituting "liberating insight", which is attained after mastering the Rupa Jhanas, is a later addition to texts such as Majjhima Nikaya 36.[110][106][107]

Earliest Buddhism

According to Tilmann Vetter, the core of earliest Buddhism is the practice of dhyāna,[118] as a workable alternative to painful ascetic practices.[119][note 19] Bronkhorst agrees that Dhyāna was a Buddhist invention,[106][page needed] whereas Norman notes that "the Buddha's way to release [...] was by means of meditative practices."[121] Discriminating insight into transiency as a separate path to liberation was a later development.[122][123]

According to the Mahāsaccakasutta,[note 20] from the fourth jhana the Buddha gained bodhi. Yet, it is not clear what he was awakened to.[121][106][page needed] According to Schmithausen and Bronkhorst, "liberating insight" is a later addition to this text, and reflects a later development and understanding in early Buddhism.[110][106][page needed] The mentioning of the four truths as constituting "liberating insight" introduces a logical problem, since the four truths depict a linear path of practice, the knowledge of which is in itself not depicted as being liberating:[124]

[T]hey do not teach that one is released by knowing the four noble truths, but by practicing the fourth noble truth, the eightfold path, which culminates in right samadhi.[124]

Although "Nibbāna" (Sanskrit: Nirvāna) is the common term for the desired goal of this practice, many other terms can be found throughout the Nikayas, which are not specified.[125][note 21]

According to Vetter, the description of the Buddhist path may initially have been as simple as the term "the middle way".[126] In time, this short description was elaborated, resulting in the description of the eightfold path.[126]

According to both Bronkhorst and Anderson, the four truths became a substitution for prajna, or "liberating insight", in the suttas[90][87][page needed] in those texts where "liberating insight" was preceded by the four jhanas.[127] According to Bronkhorst, the four truths may not have been formulated in earliest Buddhism, and did not serve in earliest Buddhism as a description of "liberating insight".[128] Gotama's teachings may have been personal, "adjusted to the need of each person."[127]

The three marks of existence[note 22] may reflect Upanishadic or other influences. K.R. Norman supposes that these terms were already in use at the Buddha's time, and were familiar to his listeners.[129]

The Brahma-vihara was in origin probably a brahmanic term;[130] but its usage may have been common to the Sramana traditions.[106]

Later developments

In time, "liberating insight" became an essential feature of the Buddhist tradition. The following teachings, which are commonly seen as essential to Buddhism, are later formulations which form part of the explanatory framework of this "liberating insight":[107][106]

- The Four Noble Truths: that suffering is an ingrained part of existence; that the origin of suffering is craving for sensuality, acquisition of identity, and fear of annihilation; that suffering can be ended; and that following the Noble Eightfold Path is the means to accomplish this;

- The Noble Eightfold Path: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration;

- Dependent origination: the mind creates suffering as a natural product of a complex process.

Other religions

Some Hindus regard Gautama as the 9th avatar of Vishnu.[note 8][131] However, Buddha's teachings deny the authority of the Vedas and the concepts of Brahman-Atman.[132][133][134] Consequently Buddhism is generally classified as a nāstika school (heterodox, literally "It is not so"[note 23]) in contrast to the six orthodox schools of Hinduism.[137][138][139]

The Buddha is regarded as a prophet by the minority Ahmadiyya[web 23] sect of Muslims – a sect considered a deviant and rejected as apostate by mainstream Islam.[140][141] Some early Chinese Taoist-Buddhists thought the Buddha to be a reincarnation of Laozi.[142]

Disciples of the Cao Đài religion worship the Buddha as a major religious teacher.[143] His image can be found in both their Holy See and on the home altar. He is revealed during communication with Divine Beings as son of their Supreme Being (God the Father) together with other major religious teachers and founders like Jesus, Laozi, and Confucius.[144]

The Christian Saint Josaphat is based on the Buddha. The name comes from the Sanskrit Bodhisattva via Arabic Būdhasaf and Georgian Iodasaph.[145] The only story in which St. Josaphat appears, Barlaam and Josaphat, is based on the life of the Buddha.[146] Josaphat was included in earlier editions of the Roman Martyrology (feast day 27 November) — though not in the Roman Missal — and in the Eastern Orthodox Church liturgical calendar (26 August).

In the ancient Gnostic sect of Manichaeism, the Buddha is listed among the prophets who preached the word of God before Mani.[147]

Guanyin

| Guanyin | |||

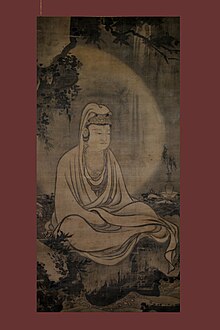

Northern Song Dynasty wood carving of Guanyin, c. 1025. Male bodhisattva depiction with Amitābha Buddha crown.

|

|||

| Chinese name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 观音 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 觀音 | ||

|

|||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||

| Simplified Chinese | 观世音 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 觀世音 | ||

| Literal meaning | Observing the Sounds (or Cries) of the World | ||

|

|||

| Burmese name | |||

| Burmese | ကွမ်ရင် | ||

| IPA | [kwàɴ jɪ̀ɴ] | ||

| Vietnamese name | |||

| Vietnamese | Quan Âm Quán Thế Âm |

||

| Thai name | |||

| Thai | กวนอิม | ||

| Korean name | |||

| Hangul | 관음 관세음 |

||

| Hanja | 觀音 觀世音 |

||

|

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 観音 觀音 観世音 観音菩薩 |

||

|

|||

Guanyin (in pinyin; previous transliterations Quan Yin, Kwan Yin, or Kuanyin[1]) is the bodhisattva associated with compassion as venerated by East Asian Buddhists, usually as a female. The name Guanyin is short for Guanshiyin, which means "Observing the Sounds (or Cries) of the World". She is also sometimes referred to as Guanyin Pusa (simplified Chinese: 观音菩萨; traditional Chinese: 觀音菩薩; pinyin: Guānyīn Púsà; literally: "Bodhisattva Guanyin").[2] Some Buddhists believe that when one of their adherents departs from this world, they are placed by Guanyin in the heart of a lotus, and then sent to the western pure land of Sukhāvatī.[3]

It is generally accepted among East Asian adherents that Guanyin originated as the Sanskrit Avalokiteśvara (अवलोकितेश्वर). Commonly known in English as the Mercy Goddess or Goddess of Mercy,[4] Guanyin is also revered by Chinese Taoists (or Daoists) as an Immortal. However, in folk traditions such as Chinese mythology, there are other stories about Guanyin's origins that are outside the accounts of Avalokiteśvara recorded in Buddhist sutras.

Contents

Etymology

Avalokitasvara

Guānyīn is a translation from the Sanskrit Avalokitasvara, referring to the Mahāyāna bodhisattva of the same name. Another later name for this bodhisattva is Guānzìzài (simplified Chinese: 观自在; traditional Chinese: 觀自在; pinyin: Guānzìzài). It was initially thought that the Chinese mis-transliterated the word Avalokiteśvara as Avalokitasvara which explained why Xuanzang translated it as Guānzìzài instead of Guānyīn. However, according to recent research, the original form was indeed Avalokitasvara with the ending a-svara ("sound, noise"), which means "sound perceiver", literally "he who looks down upon sound" (i.e., the cries of sentient beings who need his help; a-svara can be glossed as ahr-svara, "sound of lamentation").[5] This is the exact equivalent of the Chinese translation Guānyīn. This etymology was furthered in the Chinese by the tendency of some Chinese translators, notably Kumarajiva, to use the variant Guānshìyīn, literally "he who perceives the world's lamentations"—wherein lok was read as simultaneously meaning both "to look" and "world" (Skt. loka; Ch. 世, shì).[5]

Direct translations from the Sanskrit name Avalokitasvara include:

- Chinese: Guanyin (觀音), Guanshiyin (觀世音)[6]

Avalokiteśvara

The name Avalokitasvara was later supplanted by the Avalokiteśvara form containing the ending -īśvara, which does not occur in Sanskrit before the seventh century. The original form Avalokitasvara already appears in Sanskrit fragments of the fifth century.[7] The original meaning of the name "Avalokitasvara" fits the Buddhist understanding of the role of a bodhisattva. The reinterpretation presenting him as an īśvara shows a strong influence of Śaivism, as the term īśvara was usually connected to the Hindu notion of Śiva as a creator god and ruler of the world. Some attributes of such a god were transmitted to the bodhisattva, but the mainstream of those who venerated Avalokiteśvara upheld the Buddhist rejection of the doctrine of any creator god.[8]

Direct translations from the Sanskrit name Avalokiteśvara include:

- Chinese: Guanzizai (觀自在)

- Tibetan: Chenrezig (སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས།)

Names in Asian countries

Due to the devotional popularity of Guanyin in East Asia, she is known by many names, most of which are simply the localised pronunciations of "Guanyin" or "Guanshiyin":

- In Macau, Hong Kong and southern China, the name is pronounced Gwun Yam or Gun Yam in the Cantonese language, also written as Kwun Yam in Hong Kong or Kun Iam in Macau.

- In Japanese, Guanyin is pronounced Kannon (観音), occasionally Kan'on, or more formally Kanzeon (観世音, the same characters as Guanshiyin); the spelling Kwannon, based on a pre-modern pronunciation, is sometimes seen. This rendition was used for an earlier spelling of the well-known camera manufacturer Canon, which was named for Guanyin.[9]

- In Korean, Guanyin is called Gwan-eum (관음) or Gwanse-eum (관세음).

- In Thai, she is called Kuan Im (Thai: กวนอิม), Phra Mae Kuan Im (Thai: พระแม่กวนอิม), or Chao Mae Kuan Im (Thai: เจ้าแม่กวนอิม).

- In Vietnamese, the name is Quan Âm or Quán Thế Âm.

- In Indonesian, the name is Kwan Im or Dewi Kwan Im referring the word Dewi as Devi or Goddess. She is also called Mak Kwan Im (媽觀音) referring the word Mak as Mother.

- In Khmer, the name is "Preah Mae Kun Ci Iem".

In these same countries, the variant Guanzizai (觀自在 lit. "Lord of Contemplation") and its equivalents are also used, such as in the Heart Sutra, among other sources.

Depiction

Lotus Sūtra

Guanyin is the Chinese name for Avalokitasvara / Avalokiteśvara. However, folk traditions in China and other East Asian countries have added many distinctive characteristics and legends. Avalokiteśvara was originally depicted as a male bodhisattva, and therefore wears chest-revealing clothing and may even sport a light moustache. Although this depiction still exists in the Far East, Guanyin is more often depicted as a woman in modern times. Additionally, some people believe that Guanyin is androgynous (or perhaps neither).[10]

The Lotus Sūtra (Skt. Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra) describes Avalokiteśvara as a bodhisattva who can take the form of any type of male or female, adult or child, human or non-human being, in order to teach the Dharma to sentient beings.[11] This text and its thirty-three manifestations of Guanyin, of which seven are female manifestations, is known to have been very popular in Chinese Buddhism as early as in the Sui Dynasty and Tang Dynasty.[12] Additionally, Tan Chung notes that according to the doctrines of the Mahāyāna sūtras themselves, it does not matter whether Guanyin is male, female, or genderless, as the ultimate reality is in emptiness (Skt. śūnyatā).[12]

Iconography

Representations of the bodhisattva in China prior to the Song Dynasty (960–1279) were masculine in appearance. Images which later displayed attributes of both genders are believed to be in accordance with the Lotus Sutra, where Avalokitesvara has the supernatural power of assuming any form required to relieve suffering, and also has the power to grant children (possibly relating to the fact that in this Sutra, unlike in others, both men and women are believed to have the ability to achieve enlightenment.[citation needed]) Because this bodhisattva is considered the personification of compassion and kindness, a mother-goddess and patron of mothers and seamen, the representation in China was further interpreted in an all-female form around the 12th century. In the modern period, Guanyin is most often represented as a beautiful, white-robed woman, a depiction which derives from the earlier Pandaravasini form.

In some Buddhist temples and monasteries, Guanyin's image is occasionally that of a young man dressed in Northern Song Dynasty Buddhist robes and seated gracefully. He is usually depicted looking or glancing down, symbolising that Guanyin continues to watch over the world.

In China, Guanyin is generally portrayed as a young woman donned in a white flowing robe and usually wearing necklaces of Indian/Chinese royalty. In her left hand is a jar containing pure water, and the right holds a willow branch. The crown usually depicts the image of Amitabha Buddha.

There are also regional variations of Guanyin depictions. In the Fujian region of China, for example, a popular depiction of Guanyin is as a maiden dressed in Tang Dynasty style clothing carrying a fish basket. A popular image of Guanyin as both Guanyin of the South Sea and Guanyin With a Fish Basket can be seen in late 16th-century Chinese encyclopedias and in prints that accompany the novel Golden Lotus.

In Chinese art, Guanyin is often depicted either alone, standing atop a dragon, accompanied by a white parrot, flanked by two children, or flanked by two warriors. The two children are her acolytes who came to her when she was meditating at Mount Putuo. The girl is called Longnü and the boy Shancai. The two warriors are the historical general Guan Yu from the late Han Dynasty and the bodhisattva Skanda, who appears in the Chinese classical novel Fengshen Bang. The Buddhist tradition also displays Guanyin, or other buddhas and bodhisattvas, flanked with the above mentioned warriors, but as bodhisattvas who protect the temple and the faith itself.

Legends

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism 汉传佛教 / 漢傳佛教 Hànchuán Fójiào |

|---|

Guanyin and the Thousand Arms

One Buddhist legend from the Complete Tale of Guanyin and the Southern Seas (Chinese: 南海觀音全撰; pinyin: Nánhǎi Guānyīn Quánzhuàn) presents Guanyin as vowing to never rest until she had freed all sentient beings from the samsara or reincarnation.[13] Despite strenuous effort, she realised that there were still many unhappy beings yet to be saved. After struggling to comprehend the needs of so many, her head split into eleven pieces. The buddha Amitabha, upon seeing her plight, gave her eleven heads to help her hear the cries of those who are suffering. Upon hearing these cries and comprehending them, Avalokitesvara attempted to reach out to all those who needed aid, but found that her two arms shattered into pieces. Once more, Amitabha came to her aid and appointed her a thousand arms to let her reach out to those in need. Many Himalayan versions of the tale include eight arms with which Avalokitesvara skillfully upholds the Dharma, each possessing its own particular implement, while more Chinese-specific versions give varying accounts of this number.

In China, it is said that fishermen used to pray to her to ensure safe voyages. The titles Guanyin of the Southern Ocean (南海觀音) and "Guanyin (of/on) the Island" stem from this tradition.

Legend of Miaoshan

Another story from the Precious Scroll of Fragrant Mountain (香山寶卷) describes an incarnation of Guanyin as the daughter of a cruel king who wanted her to marry a wealthy but uncaring man. The story is usually ascribed to the research of the Buddhist monk Chiang Chih-ch'i during the 11th century. The story is likely to have its origin in Taoism. When Chiang penned the work, he believed that the Guanyin we know today was actually a princess called Miaoshan (妙善), who had a religious following on Fragrant Mountain. Despite this there are many variants of the story in Chinese mythology.[14]

According to the story, after the king asked his daughter Miaoshan to marry the wealthy man, she told him that she would obey his command, so long as the marriage eased three misfortunes.

The king asked his daughter what were the three misfortunes that the marriage should ease. Miaoshan explained that the first misfortune the marriage should ease was the suffering people endure as they age. The second misfortune it should ease was the suffering people endure when they fall ill. The third misfortune it should ease was the suffering caused by death. If the marriage could not ease any of the above, then she would rather retire to a life of religion forever.

When her father asked who could ease all the above, Miaoshan pointed out that a doctor was able to do all of these.

Her father grew angry as he wanted her to marry a person of power and wealth, not a healer. He forced her into hard labour and reduced her food and drink but this did not cause her to yield.

Every day she begged to be able to enter a temple and become a nun instead of marrying. Her father eventually allowed her to work in the temple, but asked the monks to give her the toughest chores in order to discourage her. The monks forced Miaoshan to work all day and all night, while others slept, in order to finish her work. However, she was such a good person that the animals living around the temple began to help her with her chores. Her father, seeing this, became so frustrated that he attempted to burn down the temple. Miaoshan put out the fire with her bare hands and suffered no burns. Now struck with fear, her father ordered her to be put to death.

In one version of this legend, when Guanyin was executed, a supernatural tiger took her to one of the more hell-like realms of the dead. However, instead of being punished like the other spirits of the dead, Guanyin played music, and flowers blossomed around her. This completely surprised the hell guardian. The story says that Guanyin, by merely being in that Naraka (hell), turned it into a paradise.

A variant of the legend says that Miaoshan allowed herself to die at the hand of the executioner. According to this legend, as the executioner tried to carry out her father's orders, his axe shattered into a thousand pieces. He then tried a sword which likewise shattered. He tried to shoot Miaoshan down with arrows but they all veered off.

Finally in desperation he used his hands. Miaoshan, realising the fate that the executioner would meet at her father's hand should she fail to let herself die, forgave the executioner for attempting to kill her. It is said that she voluntarily took on the massive karmic guilt the executioner generated for killing her, thus leaving him guiltless. It is because of this that she descended into the Hell-like realms. While there, she witnessed first-hand the suffering and horrors that the beings there must endure, and was overwhelmed with grief. Filled with compassion, she released all the good karma she had accumulated through her many lifetimes, thus freeing many suffering souls back into Heaven and Earth. In the process, that Hell-like realm became a paradise. It is said that Yama, the ruler of hell, sent her back to Earth to prevent the utter destruction of his realm, and that upon her return she appeared on Fragrant Mountain.

Another tale says that Miaoshan never died, but was in fact transported by a supernatural tiger, believed to be the Deity of the Place,[clarification needed] to Fragrant Mountain.

The legend of Miaoshan usually ends with Miaozhuangyan, Miaoshan's father, falling ill with jaundice. No physician was able to cure him. Then a monk appeared saying that the jaundice could be cured by making a medicine out of the arm and eye of one without anger. The monk further suggested that such a person could be found on Fragrant Mountain. When asked, Miaoshan willingly offered up her eyes and arms. Miaozhuangyan was cured of his illness and went to the Fragrant Mountain to give thanks to the person. When he discovered that his own daughter had made the sacrifice, he begged for forgiveness. The story concludes with Miaoshan being transformed into the Thousand Armed Guanyin, and the king, queen and her two sisters building a temple on the mountain for her. She began her journey to heaven and was about to cross over into heaven when she heard a cry of suffering from the world below. She turned around and saw the massive suffering endured by the people of the world. Filled with compassion, she returned to Earth, vowing never to leave till such time as all suffering has ended.

After her return to Earth, Guanyin was said to have stayed for a few years on the island of Mount Putuo where she practised meditation and helped the sailors and fishermen who got stranded. Guanyin is frequently worshipped as patron of sailors and fishermen due to this. She is said to frequently becalm the sea when boats are threatened with rocks.[15] After some decades Guanyin returned to Fragrant Mountain to continue her meditation.

Guanyin and Shancai

Legend has it that Shancai (also called Sudhana in Sanskrit) was a disabled boy from India who was very interested in studying the dharma. When he heard that there was a Buddhist teacher on the rocky island of Putuo he quickly journeyed there to learn. Upon arriving at the island, he managed to find Guanyin despite his severe disability.

Guanyin, after having a discussion with Shancai, decided to test the boy's resolve to fully study the Buddhist teachings. She conjured the illusion of three sword-wielding pirates running up the hill to attack her. Guanyin took off and dashed to the edge of a cliff, the three illusions still chasing her.

Shancai, seeing that his teacher was in danger, hobbled uphill. Guanyin then jumped over the edge of the cliff, and soon after this the three bandits followed. Shancai, still wanting to save his teacher, managed to crawl his way over the cliff edge.

Shancai fell down the cliff but was halted in midair by Guanyin, who now asked him to walk. Shancai found that he could walk normally and that he was no longer crippled. When he looked into a pool of water he also discovered that he now had a very handsome face. From that day forth, Guanyin taught Shancai the entire dharma.

Guanyin and Longnü

Many years after Shancai (Sudhana) became a disciple of Guanyin, a distressing event happened in the South China Sea. The son of one of the Dragon Kings (a ruler-god of the sea) was caught by a fisherman while taking the form of a fish. Being stuck on land, he was unable to transform back into his dragon form. His father, despite being a mighty Dragon King, was unable to do anything while his son was on land. Distressed, the son called out to all of Heaven and Earth.

Hearing this cry, Guanyin quickly sent Shancai to recover the fish and gave him all the money she had. The fish at this point was about to be sold in the market. It was causing quite a stir as it was alive hours after being caught. This drew a much larger crowd than usual at the market. Many people decided that this prodigious situation meant that eating the fish would grant them immortality, and so all present wanted to buy the fish. Soon a bidding war started, and Shancai was easily outbid.

Shancai begged the fish seller to spare the life of the fish. The crowd, now angry at someone so daring, was about to pry him away from the fish when Guanyin projected her voice from far away, saying "A life should definitely belong to one who tries to save it, not one who tries to take it."

The crowd, realising their shameful actions and desire, dispersed. Shancai brought the fish back to Guanyin, who promptly returned it to the sea. There the fish transformed back to a dragon and returned home. Paintings of Guanyin today sometimes portray her holding a fish basket, which represents the aforementioned tale.

But the story does not end there. As a reward for Guanyin saving his son, the Dragon King sent his granddaughter, a girl called Longnü ("dragon girl"), to present Guanyin with the Pearl of Light. The Pearl of Light was a precious jewel owned by the Dragon King that constantly shone. Longnü, overwhelmed by the presence of Guanyin, asked to be her disciple so that she might study the dharma. Guanyin accepted her offer with just one request: that Longnü be the new owner of the Pearl of Light.

In popular iconography, Longnü and Shancai are often seen alongside Guanyin as two children. Longnü is seen either holding a bowl or an ingot, which represents the Pearl of Light, whereas Shancai is seen with palms joined and knees slightly bent to show that he was once crippled.

Guanyin and the Filial Parrot

The Precious Scroll of the Parrot (Chinese: 鸚鴿寶撰; pinyin: Yīnggē Bǎozhuàn) tells the story of a parrot who becomes a disciple of Guanyin. During the Tang Dynasty a small parrot ventures out to search for its mother's favourite food upon which it is captured by a poacher (parrots were quite popular during the Tang Dynasty). When it managed to escape it found out that its mother had already died. The parrot grieved for its mother and provides her with a proper funeral. It then sets out to become a disciple of Guanyin.

In popular iconography, the parrot is coloured white and usually seen hovering to the right side of Guanyin with either a pearl or a prayer bead clasped in its beak. The parrot becomes a symbol of filial piety.[16]

Guanyin and Chen Jinggu

When the people of Quanzhou, Fujian could not raise enough money to build a bridge, Guanyin changed into a beautiful maiden. Getting on a boat, she offered to marry any man who could hit her with a piece of silver from the edge of the water. Due to many people missing, she collected a large sum of money in her boat. However, Lü Dongbin, one of the Eight Immortals, helped a merchant hit Guanyin in the hair with silver powder, which floated away in the water. Guanyin bit her finger and a drop of blood fell into the water, but she vanished. This blood was swallowed by a washer woman, who gave birth to Chen Jinggu (陈靖姑) or Lady Linshui (临水夫人); the hair was turned into a female white snake and sexually used men and killed rival women. The snake and Chen were to be mortal enemies. The merchant was sent to be reborn as Liu Qi (刘杞).

Chen was a beautiful and talented girl, but did not wish to marry Liu Qi. Instead, she fled to Mount Lu in Jiangxi, where she learned many Taoist skills. Destiny eventually caused her to marry Liu and she became pregnant. A drought in Fujian caused many people to ask her to call for rain, which was a ritual that could not be performed while pregnant. She temporarily aborted her child, which was killed by the white snake. Chen managed to kill the snake with a sword, but died either of a miscarriage or hemorrhage; she was able to complete the ritual, and ended drought.

This story is popular in Zhejiang, Taiwan, and especially Fujian.[18]

Quan Am Thi Kinh

Quan Am Thi Kinh (觀音氏敬) is a Vietnamese verse recounting the life of lady, Thi Kinh, who was accused falsely of having intended to kill her husband, and when she disguised herself as a man to lead a religious life in a Buddhist temple, she was again falsely blamed for having committed sexual intercourse with a girl and having made her pregnant, which was strictly forbidden by Buddhist law, but thanks to her endurance of all indignities and her spirit of self-sacrifice, she could enter into Nirvana and became Goddess of Mercy.[19]

Guanyin and vegetarianism

Due to her symbolization of compassion, in East Asia Guanyin is associated with vegetarianism. Chinese vegetarian restaurants are generally decorated with her image, and she appears in most Buddhist vegetarian pamphlets and magazines.

Guanyin in East Asian Buddhism

In Chinese Buddhism, Guanyin is synonymous with the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. Among the Chinese, Avalokitesvara is almost exclusively called Guanshiyin Pusa (觀世音菩薩). The Chinese translation of many Buddhist sutras has in fact replaced the Chinese transliteration of Avalokitesvara with Guanshiyin (觀世音) Some Daoist scriptures give her the title of Guanyin Dashi, and sometimes informally as Guanyin Fozu.

In Chinese culture, the popular belief and worship of Guanyin as a goddess[citation needed] by the populace is generally not viewed to be in conflict with the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara's nature. In fact the widespread worship of Guanyin as a "Goddess of Mercy and Compassion"[citation needed] is seen as the boundless salvific nature of bodhisattva Avalokitesvara at work (in Buddhism, this is referred to as Guanyin's "skillful means", or upaya). The Buddhist canon states that bodhisattvas can assume whatsoever gender and form is needed to liberate beings from ignorance and dukkha. With specific reference to Avalokitesvara, he is stated both in the Lotus Sutra (Chapter 25 "Perceiver of the World's Sounds" or "Universal Gateway"), and the Surangama Sutra to have appeared before as a woman or a goddess to save beings from suffering and ignorance. Some Buddhist schools refer to Guanyin both as male and female interchangeably.

In Mahayana Buddhism, gender is no obstacle to attaining enlightenment (or nirvana). The Buddhist concept of non-duality applies here. The Vimalakirti Sutra in the Goddess chapter clearly illustrates an enlightened being who is also a female and deity. In the Lotus Sutra a maiden became enlightened in a very short time span. The view that the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara is also the goddess Guanyin does not seem contradictory to Buddhist beliefs. Guanyin has been a buddha called the Tathāgata of Brightness of Correct Dharma (正法明如來).[20]

Given that bodhisattvas are known to incarnate at will as living people according to the sutras, the princess Miaoshan is generally viewed as an incarnation of Avalokitesvara.

Guanyin is immensely popular among Chinese Buddhists, especially those from devotional schools. She is generally seen as a source of unconditional love and, more importantly, as a saviour. In her bodhisattva vows, Guanyin promises to answer the cries and pleas of all sentient beings and to liberate them from their own karmic woes. Based on the Lotus Sutra and the Shurangama sutra, Avalokitesvara is generally seen as a saviour, both spiritually and physically. The sutras state that through his saving grace even those who have no chance of being enlightened can be enlightened, and those deep in negative karma can still find salvation through his compassion.

In Pure Land Buddhism, Guanyin is described as the "Barque of Salvation". Along with Amitabha Buddha and the bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta, She temporarily liberates beings out of the Wheel of Samsara into the Pure Land, where they will have the chance to accrue the necessary merit so as to be a Buddha in one lifetime. In Chinese Buddhist iconography, Guanyin is often depicted as meditating or sitting alongside one of the Buddhas and usually accompanied by another bodhisattva. The buddha and bodhisattva that are portrayed together with Guanyin usually follow whichever school of Buddhism they represent. In Pure Land for example, Guanyin is frequently depicted on the left of Amitabha, while on the buddha's right is Mahasthamaprapta. Temples that revere the bodhisattva Ksitigarbha usually depict him meditating beside Amitabha and Guanyin.

Even among Chinese Buddhist schools that are non-devotional, Guanyin is still highly venerated. Instead of being seen as an active external force of unconditional love and salvation, the personage of Guanyin is highly revered as the principle of compassion, mercy and love. The act, thought and feeling of compassion and love is viewed as Guanyin. A merciful, compassionate, loving individual is said to be Guanyin. A meditative or contemplative state of being at peace with oneself and others is seen as Guanyin.

In the Mahayana canon, the Heart Sutra is ascribed entirely to Guanyin. This is unique, as most Mahayana Sutras are usually ascribed to Shakyamuni Buddha and the teachings, deeds or vows of the bodhisattvas are described by Shakyamuni Buddha. In the Heart Sutra, Guanyin describes to the arhat Sariputra the nature of reality and the essence of the Buddhist teachings. The famous Buddhist saying "Form is emptiness, emptiness is form" (色即是空,空即是色) comes from this sutra.

Guanyin in other religions

Guanyin is an extremely popular goddess in Chinese folk belief and is worshiped in many Chinese communities throughout East and South East Asia.[21][22][23][24][25] For example in Taoism, records claim Guanyin was a Chinese female who became an immortal Cihang Zhenren in Shang Dynasty or Xingyin (姓音).[26]

Guanyin is revered in the general Chinese population due to her unconditional love and compassion. She is generally regarded by many as the protector of women and children. By this association, she is also seen as a fertility goddess capable of granting children to couples. An old Chinese superstition involves a woman who, wishing to have a child, offers a shoe to Guanyin. In Chinese culture, a borrowed shoe sometimes is used when a child is expected. After the child is born, the shoe is returned to its owner along with a new pair as a thank you gift.[2]

Guanyin is also seen as the champion of the unfortunate, the sick, the disabled, the poor, and those in trouble. Some coastal and river areas of China regard her as the protector of fishermen, sailors, and generally people who are out at sea, thus many have also come to believe that Mazu, the Daoist goddess of the sea, is a manifestation of Guanyin. Due to her association with the legend of the Great Flood, where she sent down a dog holding rice grains in its tail after the flood, she is worshiped as an agrarian and agriculture goddess. In some quarters, especially among business people and traders, she is looked upon as a goddess of fortune. In recent years there have been claims of her being the protector of air travelers.

Guanyin is also a ubiquitous figure found within the new religious movements of Asia:

- Within the Taiwan-based I-Kuan Tao sect, Guanyin is called the "Ancient Buddha of the South Sea" (南海古佛) and frequently appears in their fuji. Guanyin is sometimes confused with Yue Hui Bodhisattva due to their similar appearance.[27]

- Guanyin is called the "Ancient Buddha of the Holy Religion" (聖宗古佛) in Li-ism and in the Lord of Universe Church.[28] Li-ism mainly worships her.

- Ching Hai initiates her followers a meditation method called the "Quan Yin Method" to achieve enlightenment; followers also revere Ching Hai as an incarnate of Guanyin.

- Guanyin, known as "Quan Am Tathagata" (Quan Âm Như Lai) in the Cao Dai religion, is considered a Buddha and a teacher. She represents Buddhist doctrines and traditions as one of the three major lines of Cao Dai doctrines (Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism). She also symbolizes utmost patience, harmony, and compassion. According to her Divine messages via seances, her main role is to teach the Tao to female disciples, and guide them towards divinity. Another of her well-known role is to save people from extreme sufferings, e.g. fire, drowning, wrong accusation/ imprisonment, etc. There is even a prayer named 'salvation from sufferings' for followers to cite in dire conditions.

Guanyin and Mary

Some Buddhist and Christian observers have commented on the similarity between Guanyin and the Blessed Virgin Mary. This can be attributed to the representation of Guanyin holding a child in Chinese art and sculpture; it is believed that Guanyin is the patron saint of mothers and grants parents filial children, this apparition is popularly known as the "Child-Sending Guanyin" (送子觀音). One example of this comparison can be found in the Tzu Chi Foundation, a Taiwanese Buddhist humanitarian organisation, which noticed the similarity between this form of Guanyin and the Virgin Mary. The organisation commissioned a portrait of Guanyin holding a baby, closely resembling the typical Roman Catholic Madonna and Child painting. Copies of this portrait are now displayed prominently in Tzu Chi affiliated medical centres.

During the Edo Period in Japan, when Christianity was banned and punishable by death, some underground Christian groups venerated Jesus and the Virgin Mary by disguising them as statues of Kannon holding a child; such statues are known as Maria Kannon. Many had a cross hidden in an inconspicuous location.

It is suggested the similarity comes from the conquest and colonization of the Philippines by Spain during the 16th century, when Asian cultures influenced engravings of the Virgin Mary. Evident by this ivory carving of the Virgin Mary by a Chinese carver.[29]

In modern culture

For a 2005 Fo Guang Shan TV series, Andy Lau performed the song Kwun Sai Yam, which emphasizes the idea that everyone can be like Guanyin.[30][31][32][33]

In Episode 131 of Rumiko Takahashi's Inuyasha (Season 6 - "Trap of The Cursed Wall Hanging"), the Guanyin's Japanese title as the Deity Kwannon is mentioned. When a girl from the village of women leads Miroku into the village shrine with a wall painting, Miroku says, "I see, inside a shrine? It seems the Deity Kwannon will punish us," as he looks at the painting. In the following episode "Miroku's Most Dangerous Confession", it is revealed that the Kwannon painting was being used to seal away the demon from the marsh and limit its movements.

In Yoshihiro Togashi's Hunter x Hunter, Isaac Netero's Nen ability is called "100-Type Guanyin Bodhisattva" (Hyakushiki Kannon in Japanese), which takes the form of a gigantic multi-armed Guanyin statue. The Guanyin statue mimics Netero's hand motions, landing hits on the enemy, with attacks ranging from "Zero Hand" to "Ninety-ninth Hand".