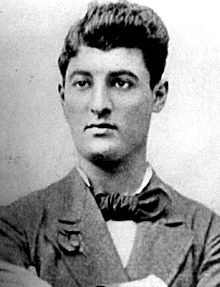

A magnificent circa 1920s James Abbe copyright silver print photograph of the great producer-director-impresario David Belasco, boldly signed by James Abbe to the reverse. Dimensions nine and a half by seven and a half inches Light wear otherwise excellent. See David Belasco and James Abbe's extraordinary biographies below.

Shipping discounts for multiple purchases. Inquiries always welcome. Please visit my other eBay items for more early theatre, opera, film and historical autographs, photographs and programs and great actor and actress cabinet photos and CDV's.

From Wikipedia:

David Belasco was born in San Francisco, California, the son of Abraham H. Belasco (1830–1911) and Reyna Belasco (née Nunes, 1830–1899), Sephardic Jews who had moved from London’s Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community during the California Gold Rush.[3]:13 He began working in a San Francisco theater doing a variety of routine jobs, such as call boy, script copier or as an extra in small parts.[3]:14 He received his first experience as a stage manager while on the road. He said, "We used to play in any place we could hire or get into—a hall, a big dining room, an empty barn; any place that would take us."[3]:14

From late 1873 to early 1874, he worked as an actor, director, and secretary at Piper's Opera House in Virginia City, Nevada, where he found "more reckless women and desperadoes to the square foot…than anywhere else in the world". His developmental years as a supporting player in Virginia City colored his thoughts eventually helping him to conceive realistic stage settings.[4] He said that while there, seeing "people die under such peculiar circumstances" made him "all the more particular in regard to the psychology of dying on the stage. I think I was one of the first to bring naturalness to bear in death scenes, and my varied Virginia City experiences did much to help me toward this. Later I was to go deeper into such studies." His recollections of that time were published in Hearst's Magazine in 1914.[5] By March 1874, he was back at work in San Francisco, eventually managing Thomas Maguire's Baldwin Theater. When Maguire lost the theater in 1882, Belasco relocated to the East Coast bringing his practical western experiences with him. The West allowed him to develop his talents as not only a performer, but in progressive production design and execution.[6]

A gifted playwright, Belasco went to New York City in 1882 where he worked as stage manager for the Madison Square Theatre (starting with Young Mrs. Winthrop), and then the old Lyceum Theatre while writing plays. By 1895, he was so successful that he was considered America's most distinguished playwright and producer.

Career

During his long creative career, stretching between 1884 and 1930, Belasco either wrote, directed, or produced more than 100 Broadway plays, including Hearts of Oak, The Heart of Maryland, and Du Barry, making him the most powerful personality on the New York City theater scene. He also helped establish careers for dozens of notable stage performers, many of whom went on to work in films.

Among them were Leslie Carter, dubbed "The American Sarah Bernhardt,"[7] whose association with Belasco skyrocketed her to theatrical fame after her roles in Zaza (1898) and Madame Du Barry (1901).[7] Ina Claire's lead in Polly with a Past (1917) and The Gold Diggers (1919) similarly propelled her career.[7] Belasco wrote a lead part for 18-year-old Maude Adams in his new play Men and Women (1890), which ran for 200 performances.[7]

Other stars whose careers he helped launch included Jeanne Eagels, who would later achieve immortality as Sadie Thompson in Rain (1923), which played for 340 performances.[8] Belasco discovered and managed the careers of Lenore Ulric[9] and David Warfield, both of whom became major stars on Broadway. He launched the career of Barbara Stanwyck, and was responsible for changing her name.[7]

Belasco is perhaps most famous for having adapted the short story Madame Butterfly into a play with the same name and for penning The Girl of the Golden West for the stage, both of which were adapted as operas by Giacomo Puccini (Madama Butterfly 1904—twice, after revision) and La fanciulla del West (1910). More than forty motion pictures have been made from the many plays he authored.

Many prominent performers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries sought the opportunity to work with Belasco; among them were D. W. Griffith, Helen Hayes, Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford[7] and Cecil B. DeMille.[7] DeMille's father had been close friends with Belasco, and after DeMille graduated from the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, he began his stage career under Belasco's guidance.[10] DeMille's later methods of handling actors, using dramatic lighting and directing films, were modeled after Belasco's staging techniques.[7]

Pickford appeared in his plays The Warrens of Virginia at the first Belasco Theatre in 1907 and A Good Little Devil in 1913. The two remained in touch after Pickford began working in Hollywood; Belasco appeared with her in the 1914 film adaptation of A Good Little Devil. He is credited as giving Pickford her stage name as well. He also worked with Lionel Barrymore, who starred in his play Laugh, Clown, Laugh opposite Lucille Kahn, whose Broadway career Belasco launched. Belasco was a member of The Lambs from 1893 to 1931.

Marriage

David Belasco was married to Cecilia Loverich for over fifty years; they had two daughters, Reina (who was married to producer Morris Gest) and Augusta.

Death

Belasco died in 1931 at the age of 77 in Manhattan.[1] He was interred in the Linden Hill Jewish Cemetery on Metropolitan Avenue in Ridgewood, Queens.[11][12]

Influence on American theatre

Belasco demanded a natural acting style, and to complement that, he developed stage settings with authentic lighting effects to enhance his plays. His productions inspired several generations of theatre lighting designers.[13]:29

Belasco's contributions to modern stage and lighting techniques were originally not appreciated as much as those of his European counterparts, such as André Antoine and Constantin Stanislavski, however today he is regarded as "one of the first significant directorial figures in the history of the American theatre," writes theatre historian Lise-Lone Marker.[3]:xi

He brought a new standard of naturalism to the American stage as the first to develop modern stage lighting along with the use of colored lights, via motorized color changing wheels, to evoke mood and setting.[3]:xi[13] America's earliest stage lighting manufacturer, Kliegl Brothers, began by serving the specialized needs of producers and directors such as Belasco and Florenz Ziegfeld.[13]:157 With regard to these modern lighting effects, Belasco is best remembered for his production of Girl of the Golden West (1905), with the play opening to a spectacular sunset which lasted five minutes before any dialogue started.[13]:29

Belasco became one of the first directors to eschew the use of traditional footlights in favor of lights concealed below floor level, thereby hidden from the audience. His lighting assistant, Louis Hartmann, realised Belasco's design ideas.[13]:29 He also used follow spots to further create realism and often tailored his lighting configurations to complement the complexions and hair of the actors.[13]:135 He ordered a specially made 1000-watt lamp developed just for his own productions, and was the only director to have one for the first two years after its introduction (1914–1915).[13]:135

In his own theatres, the dressing rooms were equipped with lamps of several colors, allowing the performers to see how their makeup looked under different lighting conditions.

Supposedly he put appropriate scents to set scenes in the ventilation of the theaters, while his sets paid great attention to detail, and sometimes spilled out into the audience area. In one play, for instance, an operational laundromat was built onstage. In The Governor's Lady, there was a reproduction of a Childs Restaurant kitchen where actors actually cooked and prepared food during the play.

He is even said to have purchased a room in a flophouse, cut it out of the building, brought it to his theater, cut out one wall and presented it as the set for a production. Belasco's original scripts were often filled with long, specific descriptions of props and set dressings. He has not been noted for producing unusually naturalistic scenarios.

Belasco also embraced existing theatre technology and sought to expand on it. Both of Belasco's New York theatres were built on the cutting edge of their era's technology. When Belasco took over the Republic Theatre he drilled a new basement level to accommodate his machinery; the Stuyvesant Theatre was specially constructed with enormous amounts of flyspace, hydraulics systems and lighting rigs. The basement of the Stuyvesant contained a working machine shop, where Belasco and his team experimented with lighting and other special effects. Many of the innovations developed in the Belasco shop were sold to other producers.

F. Scott Fitzgerald references Belasco's reputation for realism in The Great Gatsby when he has a drunken visitor in the library of Gatsby's mansion exclaim in amazement that the books are genuine: "See!" he cried triumphantly. "It's a bona-fide piece of printed matter. It fooled me. This fella's a regular Belasco. It's a triumph. What thoroughness! What realism! Knew when to stop, too—didn't cut the pages."[14]

Theatres

The first Belasco Theatre in New York was located at 229 West 42nd Street, between 7th and 8th Avenues, in the Times Square district of Manhattan. Belasco took over management of the theater and completely remodeled it in 1902, only two years after it was constructed as the Theatre Republic by Oscar Hammerstein (the grandfather of the famous lyricist). He gave up the theater in 1910 and it was renamed the Republic. Under various owners, it went through a tumultuous period as a burlesque venue, hosted second-run and, eventually, pornographic films and fell into a period of neglect before being rehabilitated and reopened as the New Victory Theater in 1995.

The second Belasco Theatre is located at 111 West 44th Street, between 6th and 7th Avenues, only a few blocks away from the New Victory. It was constructed in 1907 as the Stuyvesant Theatre and renamed after Belasco in 1910. The theater was built to Belasco's wishes, with Tiffany lighting and ceiling panels, rich woodwork and murals. His business office and private apartment were also housed there. The Belasco is still in operation as a Broadway venue with much of the original decor intact. In 2010 it underwent a massive US $14.5 million restoration, which strove to renovate and restore the theater to the condition it was in when David Belasco was alive.[15]

Belasco Theatres also existed in several other cities. In Los Angeles, the first Belasco Theatre was located at 337 S. Main St. The theater, which hosted the Belasco Stock Company, opened in 1904 and was operated by David Belasco's brother, Frederick. This theater was renamed twice: as the Republic in about 1913 and as the Follies, circa 1919. The theater eventually became a burlesque venue in the 1940s, fell into sharp decline, and was demolished in May 1974.[16][17]

The second, and perhaps more well known theatre in Los Angeles, The Belasco is located at 1050 S. Hill St in Downtown Los Angeles. The theatre, which was built by Morgan, Walls & Clements, opened in 1926, and was managed by Edward Belasco, another of David's brothers. Many Hollywood stars with theatrical roots, as well as Broadway stars who were visiting the West Coast, appeared at the theatre.[18] The theater declined after the death of Edward Belasco in 1937. After closing altogether in the early 1950s, the theater was used as a church for several decades.[19] In 2010 - 2011, the theater underwent an extensive restoration, and is currently in operation as a nightclub and convention venue.[20]

The Shubert-Belasco Theatre, located in Washington, D.C., was purchased by Belasco in September 1905. Originally built in 1895 as the Lafayette Square Opera House, at 717 Madison Place, across from the White House, the theater was razed in 1962 and replaced by the U.S. Court of Claims building.[21]

Selected plays

- Hearts of Oak (1879), by James A. Herne and David Belasco

- La Belle Russe (1882), by David Belasco

- May Blossom (1884), by David Belasco

- Lord Chumley (1888), by Henry Churchill de Mille and David Belasco

- Men and Women (1890), by Henry Churchill de Mille and David Belasco

- The Girl I Left Behind Me (1893), by Franklin Fyles and David Belasco

- Pawn Ticket No. 210 (1894), by Clay M. Greene and David Belasco

- The Heart of Maryland (1895), by David Belasco

- Zaza (1898), by David Belasco (based on the play Zaza by Pierre Berton and Charles Simon)

- Madame Butterfly (1900), by David Belasco (based on the short story Madame Butterfly by John Luther Long)

- Du Barry (1901), by David Belasco

- The Auctioneer (1901)[22][23]

- Sweet Kitty Bellairs (1903), by David Belasco (based on the novel The Bath Comedy by Agnes Castle and Egerton Castle)

- The Music Master (1904), by Charles Klein

- Adrea (1905), by David Belasco and John Luther Long

- The Girl of the Golden West (1905), by David Belasco

- Rose of the Rancho (1906), by Richard Walton Tully and David Belasco

- The Warrens of Virginia (1907), by William C. deMille

- The Fighting Hope (1908), by William J. Hurlbut

- The Easiest Way (1909), by Eugene Walter

- The Lily (1909), by David Belasco (based on the play Le Lys by Pierre Wolff and Gaston Leroux)

- Just a Wife (1910), by Eugene Walter

- The Woman (1911), by William C. deMille

- The Return of Peter Grimm (1911), by David Belasco

- The Governor's Lady (1912), by Alice Bradley

- The Case of Becky (1912), by Edward Locke

- A Good Little Devil (1913), by Austin Strong (based on the play Un bon petit diable by Rosemonde Gérard and Maurice Rostand)

- Seven Chances (1916), by Roi Cooper Megrue

- Tiger Rose (1917), by Willard Mack

- The Gold Diggers (1919), by Avery Hopwood

- The Son-Daughter (1919), by George Scarborough and David Belasco

- Kiki (1921), by David Belasco (based on the play Kiki by André Picard)

- Shore Leave (1922), by Hubert Osborne

- Laugh, Clown, Laugh (1923), by Tom Cushing and David Belasco (based on the play Ridi, pagliaccio! by Fausto Maria Martini)

- Ladies of the Evening (1924), by Milton Herbert Gropper

- The Dove (1925), by Willard Mack (based on a story by Gerald Beaumont)

- Lulu Belle (1926), by Charles MacArthur and Edward Sheldon

- Tonight or Never (1930), by Fanny Hatton and Frederic Hatton (based on the play Ma este vagy soha by Lili Hatvany)

Filmography

- Lord Chumley, directed by James Kirkwood (1914, based on the play Lord Chumley)

- La Belle Russe, directed by William J. Hanley (1914, based on the play La Belle Russe)

- Men and Women, directed by James Kirkwood (1914, based on the play Men and Women)

- Rose of the Rancho, directed by Cecil B. DeMille (1914, based on the play Rose of the Rancho)

- The Girl of the Golden West, directed by Cecil B. DeMille (1915, based on the play The Girl of the Golden West)

- The Girl I Left Behind Me, directed by Lloyd B. Carleton (1915, based on the play The Girl I Left Behind Me)

- DuBarry, directed by Edoardo Bencivenga (1915, based on the play Du Barry)

- The Heart of Maryland, directed by Herbert Brenon (1915, based on the play The Heart of Maryland)

- May Blossom, directed by Allan Dwan (1915, based on the play May Blossom)

- The Case of Becky, directed by Frank Reicher (1915, based on the play The Case of Becky)

- Madame Butterfly, directed by Sidney Olcott (1915, based on the play Madame Butterfly)

- Zaza, directed by Edwin S. Porter and Hugh Ford (1915, based on the play Zaza)

- Sweet Kitty Bellairs, directed by James Young (1916, based on the play Sweet Kitty Bellairs)

- La Belle Russe, directed by Charles Brabin (1919, based on the play La Belle Russe)

- Harakiri, directed by Fritz Lang (Germany, 1919, based on the play Madame Butterfly)

- The Heart of Maryland, directed by Tom Terriss (1921, based on the play The Heart of Maryland)

- The Case of Becky, directed by Chester M. Franklin (1921, based on the play The Case of Becky)

- Pawn Ticket 210, directed by Scott R. Dunlap (1922, based on the play Pawn Ticket No. 210)

- The Girl of the Golden West, directed by Edwin Carewe (1923, based on the play The Girl of the Golden West)

- Zaza, directed by Allan Dwan (1923, based on the play Zaza)

- Tiger Rose, directed by Sidney Franklin (1923, based on the play Tiger Rose)

- Forty Winks, directed by Paul Iribe and Frank Urson (1925, based on the play Lord Chumley)

- Seven Chances, directed by Buster Keaton (1925, based on the play Seven Chances)

- Men and Women, directed by William C. deMille (1925, based on the play Men and Women)

- Kiki, directed by Clarence Brown (1926, based on the play Kiki)

- The Lily, directed by Victor Schertzinger (1926, based on the play The Lily)

- The Return of Peter Grimm, directed by Victor Schertzinger (1926, based on the play The Return of Peter Grimm)

- The Music Master, directed by Allan Dwan (1927, based on the play The Music Master)

- The Heart of Maryland, directed by Lloyd Bacon (1927, based on the play The Heart of Maryland)

- Laugh, Clown, Laugh, directed by Herbert Brenon (1928, based on the play Laugh, Clown, Laugh)

- Ladies of Leisure, directed by Frank Capra (1930, based on the play Ladies of the Evening)

- Sweet Kitty Bellairs, directed by Alfred E. Green (1930, based on the play Sweet Kitty Bellairs)

- Du Barry, Woman of Passion, directed by Sam Taylor (1930, based on the play Du Barry)

- The Girl of the Golden West, directed by John Francis Dillon (1930, based on the play The Girl of the Golden West)

- Kiki, directed by Sam Taylor (1931, based on the play Kiki)

- Tonight or Never, directed by Mervyn LeRoy (1931, based on the play Tonight or Never)

- Girl of the Rio, directed by Herbert Brenon (1932, based on the play The Dove)

- The Hatchet Man, directed by William A. Wellman (1932, based on the play The Honorable Mr. Wong)

- The Son-Daughter, directed by Clarence Brown (1932, based on the play The Son-Daughter)

- Madame Butterfly, directed by Marion Gering (1932, based on the play Madame Butterfly)

- The Return of Peter Grimm, directed by George Nicholls Jr. (1935, based on the play The Return of Peter Grimm)

- Rose of the Rancho, directed by Marion Gering (1936, based on the play Rose of the Rancho)

- Follow the Fleet, directed by Mark Sandrich (1936, based on the play Shore Leave)

- The Girl of the Golden West, directed by Robert Z. Leonard (1938, based on the play The Girl of the Golden West)

- Zaza, directed by George Cukor (1939, based on the play Zaza)

- Lulu Belle, directed by Leslie Fenton (1948, based on the play Lulu Belle)

- Madame Butterfly, directed by Carmine Gallone (Italy, 1954, based on the opera Madama Butterfly)

- Madame Butterfly, directed by Frédéric Mitterrand (France, 1995, based on the opera Madama Butterfly)

Producer

- A Good Little Devil, directed by Edwin S. Porter (1914, Famous Players Film Company)

- Rose of the Rancho, directed by Cecil B. DeMille (1914, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Co.)

- The Girl of the Golden West, directed by Cecil B. DeMille (1915, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Co.)

- The Warrens of Virginia, directed by Cecil B. DeMille (1915, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Co.)

- The Governor's Lady, directed by George Melford (1915, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Co.)

- The Woman, directed by George Melford (1915, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Co.)

- The Fighting Hope, directed by George Melford (1915, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Co.)

- The Case of Becky, directed by Frank Reicher (1915, Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Co.)

- Her Accidental Husband, directed by Dallas M. Fitzgerald (1923, Belasco Productions, Inc.)

- The Gold Diggers, directed by Harry Beaumont (1923, Warner Bros.)

- Tiger Rose, directed by Sidney Franklin (1923, Warner Bros.)

- Welcome Stranger, directed by James Young (1924, Belasco Productions, Inc.)

- Friendly Enemies, directed by George Melford (1925, Belasco Productions, Inc.)

- Fifth Avenue, directed by Robert G. Vignola (1926, Belasco Productions, Inc.)

- The Prince of Pilsen, directed by Paul Powell (1926, Belasco Productions, Inc.)

James Edward Abbe was born in 1883 in Alfred, Maine. His career as an international photographer was first boosted by the Washington Post, which commissioned him to travel and take photographs of a 16-day voyage with the American battleship fleet to England and France in 1910. Many years later he traveled throughout Europe as a young photojournalist in the late 1920s and early 1930s recording the unstable power struggles of the early 20th century. However, he first made a name for himself photographing theatre stars of the New York stage and subsequently movie stars in New York, Hollywood, Paris, and London throughout the 1920s and 1930s. His unusual technique of working outside the studio set him apart from other photographers of the period. To make money, Abbe sold his photographs to magazines such as Vogue and Vanity Fair, which brought his subjects greater fame.[3]

Famous images

Abbe's most celebrated portraits include his rare double portraits of silent film stars Rudolph Valentino and his wife Natasha Rambova, Lillian and Dorothy Gish, as well as dancers including the Dolly Sisters and Anna Pavlova, all taken in the 1920s. Reflecting the changing fashions in magazines content, Abbe became one of the first photojournalist to submit his work in photo-essays to major publications, including The London Magazine, Vu and the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung. He also took photographs during the Spanish Civil War[4] and the Nazis' rise in Germany.

"His life would make a good movie," his daughter Tilly said. In the 1920s and '30s Abbe photographed politicians, stage and film stars—Hitler and Mussolini, Charlie Chaplin and Josephine Baker—and scored the biggest coup of his career when he finagled his way into the Kremlin and, according to Miss Tilly, "tricked" Stalin into posing for him. The result: a rare snapshot of the Soviet dictator smiling. His portrait of Joseph Stalin was famously used to stop rumors that the Soviet leader was dead.

"He called his photography 'a ticket' to the world," Tilly says. "It was partly because of him that I became a dancer. In fact, I'm named after a dancer he photographed, Tilly Losch. He loved ballet, and his favorite subject to photograph was Anna Pavlova. I knew how much he loved dancers, and of course it was very important to me to please my father."[3][5]

Personal life

Abbe was married four times and had eight surviving children. He first married in 1905 to Eloise Turner who died in November 1907. His second marriage was to Phyllis Edwards, a teacher from Richmond Virginia, whom he married in 1909 and by whom he had three children Elizabeth (Beth) born 1910, Phyllis, born 1911 and James.

This son, from his second marriage, James Abbe Jr was born in 1912; he also became a photographer and later an antiques dealer and worked in the 1940s Harper's Bazaar.[6] The marriage ended when James Abbe travelled to Italy in 1922 with a former Ziegfeld dancer Polly Platt, (née Mary Ann Shorrock) who was part of the company filming Ronald Colman and Lillian Gish in The White Sister (1923) on location in Rome and Naples for which Abbe took stills and advised on special photography. After filming was completed Abbe settled in Paris where his new wife Polly gave birth to the first of three children, Patience Shorrock Abbe on 22 July 1924, followed by Richard W. Abbe (1926-2000) and then John Abbe (born 1927).[7]

In the late 1930s, Abbe's third marriage to the former Ziegfeld dancer Polly Shorrock ended in divorce.[7] After the failure of this marriage, he married Irene Caby, the mother of ballet dancer and dance teacher Tilly (Matilda) and Malinda (Linda) Abbe.

According to a 2006 interview with his daughter, Tilly Abbe, he was married three times before he met her mother, Irene, and abandoned his third wife and three children to marry Irene. Tilly was born when her father was 56 years old, which would have been about 1939.[8]

One of the obituaries for Patience mentions that she had a surviving (presumably step-)sister Linda.