|

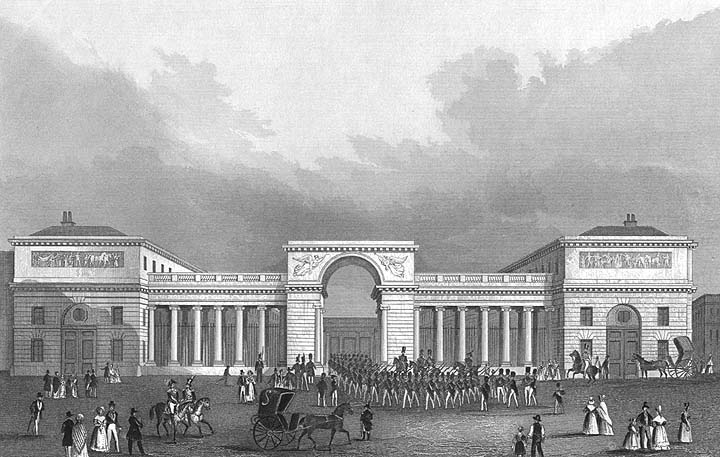

PALAIS DE LA LEGION D'HONNEUR

Artist: Unknown ____________ Engraver: Unknown |

Note: the title in the table above is printed below the engraving

Note: the title in the table above is printed below the engraving

CLICK HERE TO SEE MORE ANTIQUE WORLD VIEWS LIKE THIS ONE!!

AN ANTIQUE STEEL ENGRAVING MADE IN THE 1840s !! ITEM IS OVER 150 YEARS OLD!

VERY OLD WORLD! INCREDIBLE DETAIL!

That curious galaxy of stars, stars of knightly orders, with which the monarchs of the earth endeavor to dazzle the eyes of „the vile multitude," first shone upon the world in the days of Christian enthusiasm. Pious knights united themselves with the ecclesiastical fraternities, founded institutions of charity and hospitality for men journeying to Palestine, and vowed protection to the pilgrims, and war against the infidels, as the enthusiastic Christian termed all those, whose faith was different from his own. The members of such knightly orders bound themselves by a vow to fraternity, poverty, chastity and obedience; they wore a common garb and a common badge. Time changed these institutions. From their professed poverty the orders rose gradually to great wealth and power. The knights of St. John, the knights Templars, the Teutoise order, possessed immense territories. The vow of poverty became a phrase, their other vow were neglected likewise, and at last, after the bright flame of religious enthusiasm had sunk lower and lower, the very object of the ecclesiastical orders of chivalry was entirely lost sight of. These institutions roused at last the rapacity and jealousy of the princes. They were persecuted, robbed of their estates, or transformed into mere tools of despotism, or into toys to lure the ridiculous vanity of frail mankind. The ruling lords of Europe early recognized in the contemptible thing, which remained of the old, knightly fraternities, namely in their common badge and costume, some means for the increase of their power. They transformed the plain knightly cross into sparkling, and often costly decorations, which entitled the possessor to a higher degree in the scale of monarchical society or to a certain share in the revenues of the order. The new bait was prepared to catch weak souls, and to make them the servants to their Lord's will and projects.

In early times the princes paid some regard to the signification which they themselves attached to their various-shaped crosses and stars. They bestowed them on their servants and vassals as tokens of their favor, as an outwardly visible proof of their personal inclination or esteem. By and by other motives stepped in. The more ardently the princes pursued their plans, to destroy, piece by piece, the rights of their peoples, rights which hemmed in their lust for arbitrary power, so much the more greedily did they catch at every means to separate the wealthy, the strong, the honored from the mass of their subjects and to bind them to their own interests by some tie of vanity or private advantage. A fit tool for this end they found out in a long, and well graduated chain of knightly-court, house-, military- and civil-orders. The stars and crosses, which dropped henceforth from princely hands like rain-showers, were proclaimed as tokens for honorable service done to Monarchs and Monarchy. And to make the mockery and puppet-show complete, individuals, who suffered themselves to be thus decorated on acount of their actions, or of faithful service, were entitled to rank with the parasites and tinsel-men of the courts, and admitted to the right and honor to make their bows at court in the livery of their gracious masters. A paragraph, common to the statutes of all orders, declared the members of reigning families by birth entitled to the highest degrees of the orders, being a solemn declaration, that it was a na rit to come into the world a born prince! But it was less by absurdities of this sort, that the system of orders exercised a corrupting influence upon the popular vitality, than by the division of them into a classified scale. So long as the orders had but one class, the selection of knights was confined to a certain circle in society, and to a smaller number,* the life of the middle and lower classes remained untainted by that pestilence of vanity, the mass of the people ranked as equals at least in point of their claim to decoration. But by the division and subdivision of the orders, which now shot up like mushrooms from the ground, a way was found to bind individuals, even of the humblest classes, by the long string of badges' to increase the number of their members at will, and to diffuse the demoralizing air of the courts and their falsified ideas of honor, in the widest circle, and, above all, to force upon the compact middle-classes, to which, until now, it had been a stranger, that sense of nice distinctions of rank in society which could not but destroy the independence of the citizen, and his proud defiance of every usurping power. Moeser, the popular writer for popular rights, remarked long ago on this subject: „ln consequence of this order-system, princely governments have acquired a new and mighty power, without any particular expenditure of capital, for if there be any, it is defrayed by the state-treasury. By their tinsels, their shabby medals, their crosses and stars, they are enabled to make vain men by thousands slaves to their interests, or, at least, to weaken and neutralize the spirit of opposition, to reward services performed and promised, and by passing some over, to excite a feeling of mortification in the bosoms even of those, supposed to possess more moral fortitude." In this spirit of corruption has the system of orders been managed to the present hour. Services done to princes and monarchy have always been rewarded with orders, services to the people with the dungeon. To men, who enjoy the people's confidence, the brilliant star of court-favor is displayed, as a bait, so long, till dazzled by its lustre, they have caught the hook and turning their backs to the people, and forsaking long avowed and defended principles, they unite freely in the career of oppression and persecution. The graduation of orders has been in these latter times carried to such an extent, that it appears now downright ridiculous and childish. They have created classes of crosses and medals with the ribbon and without the ribbon, and the distinctions set down in the statutes are so manifold and minute, that a correct knowledge of them assumes the rank of grave science.

The storm, which is gathering over monarchical Europe, will do away with these institutions that mock human reason. Their sentence was pronounced long ago by the deep scorn with which the people everywhere looked upon it, a scorn which considered the decorations, even when viewed in the most favorable light, only as a proof of-vanity. Now-a-days, though despotism triumphs in Europe, it is considered creditable to an honest man, to keep his coat clean from such trash and there are thousands of poor knights, who conceal the worthless gifts of royal grace in a secret drawer, that they might not meet their own eyes and offend their better feelings. All that has been said of these orders" in general is applicable to of the Legion of Honor in France. So long as Napoleon, the founder, was himself grandmaster of the order, its badge stood foremost among all,' it had some rational meaning and some claims to the popular esteem. The great emperor's star of glory cast its beams upon it. The restored Bourbons made it their particular aim, to bring it into disrepute. Under king Charles X., the popular wit called it .the shoe-black's badge". It became utterly contemptible under the crafty Louis Philippe; and under the present government, which has degraded the grande national to the laughing-stock of the world, and transformed France into the tomb of liberty, no man can wear the cross without creating a suspicion of belonging to the set of men, that are now busy in timbering the imperial throne for their captain. While the uncle in instituting the legion confined its number to sixteen cohorts, and to each cohort gave seven grand officers, and three hundred and fifty legionaries, the order, under the nephew, counts a hundred thousand knights. In the engraving we behold the palace of the order, so called as the dwelling of its high chancellor. This splendid structure is the principal ornament of the Rue de Lille in Paris. The inscription: Honneur et Patrie" which adorns the portico in golden letters, has, long before a scoundrel lavished the cross upon the thousands of his accomplices, become-a lie.

That curious galaxy of stars, stars of knightly orders, with which the monarchs of the earth endeavor to dazzle the eyes of „the vile multitude," first shone upon the world in the days of Christian enthusiasm. Pious knights united themselves with the ecclesiastical fraternities, founded institutions of charity and hospitality for men journeying to Palestine, and vowed protection to the pilgrims, and war against the infidels, as the enthusiastic Christian termed all those, whose faith was different from his own. The members of such knightly orders bound themselves by a vow to fraternity, poverty, chastity and obedience; they wore a common garb and a common badge. Time changed these institutions. From their professed poverty the orders rose gradually to great wealth and power. The knights of St. John, the knights Templars, the Teutoise order, possessed immense territories. The vow of poverty became a phrase, their other vow were neglected likewise, and at last, after the bright flame of religious enthusiasm had sunk lower and lower, the very object of the ecclesiastical orders of chivalry was entirely lost sight of. These institutions roused at last the rapacity and jealousy of the princes. They were persecuted, robbed of their estates, or transformed into mere tools of despotism, or into toys to lure the ridiculous vanity of frail mankind. The ruling lords of Europe early recognized in the contemptible thing, which remained of the old, knightly fraternities, namely in their common badge and costume, some means for the increase of their power. They transformed the plain knightly cross into sparkling, and often costly decorations, which entitled the possessor to a higher degree in the scale of monarchical society or to a certain share in the revenues of the order. The new bait was prepared to catch weak souls, and to make them the servants to their Lord's will and projects.

In early times the princes paid some regard to the signification which they themselves attached to their various-shaped crosses and stars. They bestowed them on their servants and vassals as tokens of their favor, as an outwardly visible proof of their personal inclination or esteem. By and by other motives stepped in. The more ardently the princes pursued their plans, to destroy, piece by piece, the rights of their peoples, rights which hemmed in their lust for arbitrary power, so much the more greedily did they catch at every means to separate the wealthy, the strong, the honored from the mass of their subjects and to bind them to their own interests by some tie of vanity or private advantage. A fit tool for this end they found out in a long, and well graduated chain of knightly-court, house-, military- and civil-orders. The stars and crosses, which dropped henceforth from princely hands like rain-showers, were proclaimed as tokens for honorable service done to Monarchs and Monarchy. And to make the mockery and puppet-show complete, individuals, who suffered themselves to be thus decorated on acount of their actions, or of faithful service, were entitled to rank with the parasites and tinsel-men of the courts, and admitted to the right and honor to make their bows at court in the livery of their gracious masters. A paragraph, common to the statutes of all orders, declared the members of reigning families by birth entitled to the highest degrees of the orders, being a solemn declaration, that it was a na rit to come into the world a born prince! But it was less by absurdities of this sort, that the system of orders exercised a corrupting influence upon the popular vitality, than by the division of them into a classified scale. So long as the orders had but one class, the selection of knights was confined to a certain circle in society, and to a smaller number,* the life of the middle and lower classes remained untainted by that pestilence of vanity, the mass of the people ranked as equals at least in point of their claim to decoration. But by the division and subdivision of the orders, which now shot up like mushrooms from the ground, a way was found to bind individuals, even of the humblest classes, by the long string of badges' to increase the number of their members at will, and to diffuse the demoralizing air of the courts and their falsified ideas of honor, in the widest circle, and, above all, to force upon the compact middle-classes, to which, until now, it had been a stranger, that sense of nice distinctions of rank in society which could not but destroy the independence of the citizen, and his proud defiance of every usurping power. Moeser, the popular writer for popular rights, remarked long ago on this subject: „ln consequence of this order-system, princely governments have acquired a new and mighty power, without any particular expenditure of capital, for if there be any, it is defrayed by the state-treasury. By their tinsels, their shabby medals, their crosses and stars, they are enabled to make vain men by thousands slaves to their interests, or, at least, to weaken and neutralize the spirit of opposition, to reward services performed and promised, and by passing some over, to excite a feeling of mortification in the bosoms even of those, supposed to possess more moral fortitude." In this spirit of corruption has the system of orders been managed to the present hour. Services done to princes and monarchy have always been rewarded with orders, services to the people with the dungeon. To men, who enjoy the people's confidence, the brilliant star of court-favor is displayed, as a bait, so long, till dazzled by its lustre, they have caught the hook and turning their backs to the people, and forsaking long avowed and defended principles, they unite freely in the career of oppression and persecution. The graduation of orders has been in these latter times carried to such an extent, that it appears now downright ridiculous and childish. They have created classes of crosses and medals with the ribbon and without the ribbon, and the distinctions set down in the statutes are so manifold and minute, that a correct knowledge of them assumes the rank of grave science.

The storm, which is gathering over monarchical Europe, will do away with these institutions that mock human reason. Their sentence was pronounced long ago by the deep scorn with which the people everywhere looked upon it, a scorn which considered the decorations, even when viewed in the most favorable light, only as a proof of-vanity. Now-a-days, though despotism triumphs in Europe, it is considered creditable to an honest man, to keep his coat clean from such trash and there are thousands of poor knights, who conceal the worthless gifts of royal grace in a secret drawer, that they might not meet their own eyes and offend their better feelings. All that has been said of these orders" in general is applicable to of the Legion of Honor in France. So long as Napoleon, the founder, was himself grandmaster of the order, its badge stood foremost among all,' it had some rational meaning and some claims to the popular esteem. The great emperor's star of glory cast its beams upon it. The restored Bourbons made it their particular aim, to bring it into disrepute. Under king Charles X., the popular wit called it .the shoe-black's badge". It became utterly contemptible under the crafty Louis Philippe; and under the present government, which has degraded the grande national to the laughing-stock of the world, and transformed France into the tomb of liberty, no man can wear the cross without creating a suspicion of belonging to the set of men, that are now busy in timbering the imperial throne for their captain. While the uncle in instituting the legion confined its number to sixteen cohorts, and to each cohort gave seven grand officers, and three hundred and fifty legionaries, the order, under the nephew, counts a hundred thousand knights. In the engraving we behold the palace of the order, so called as the dwelling of its high chancellor. This splendid structure is the principal ornament of the Rue de Lille in Paris. The inscription: Honneur et Patrie" which adorns the portico in golden letters, has, long before a scoundrel lavished the cross upon the thousands of his accomplices, become-a lie.

SIZE: Print is 7 1/2 inches by 11 inches including white borders not shown, image size is 4 inches by 6 inches.

CONDITION: Condition is excellent. Clean. Blank on reverse.

SHIPPING:Buyers to pay shipping/handling, domestic orders receives priority mail, international orders receive regular mail.

We pack properly to protect your item!

Please note: the terms used in our auctions for engraving, heliogravure, lithograph, print, plate, photogravure etc. are ALL prints on paper, NOT blocks of steel or wood. "ENGRAVINGS", the term commonly used for these paper prints, were the most common method in the 1700s and 1800s for illustrating old books, and these paper prints or "engravings" were inserted into the book with a tissue guard frontis, usually on much thicker quality rag stock paper, although many were also printed and issued as loose stand alone prints. So this auction is for an antique paper print(s), probably from an old book, of very high quality and usually on very thick rag stock paper.

FINE ANTIQUE WORLD VIEW!

|