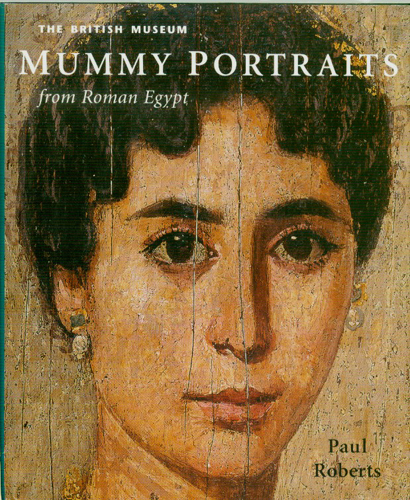

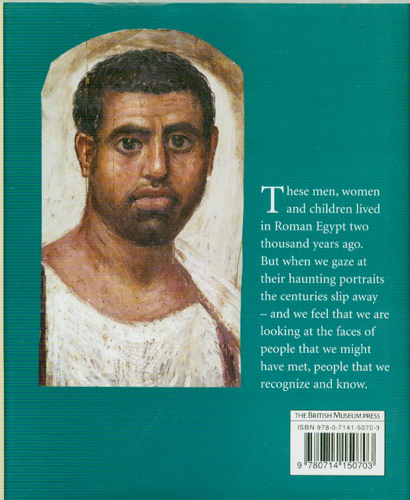

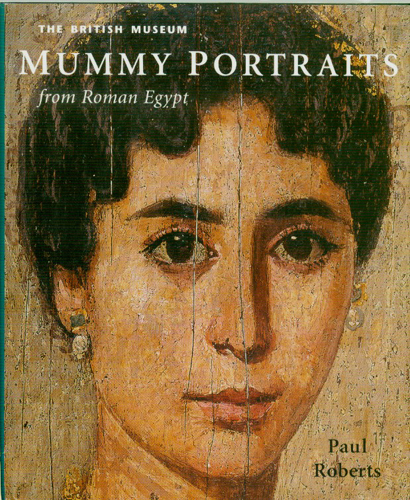

"British Museum Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt" by Paul Roberts.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

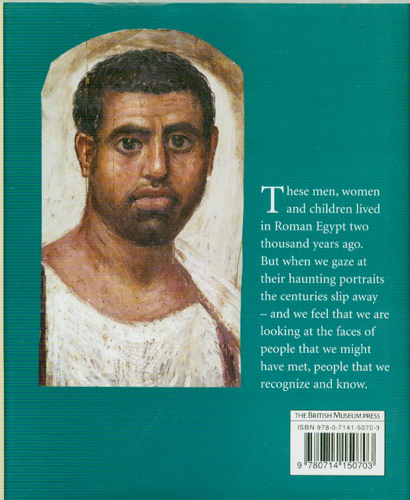

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with dustjacket. Publisher: British Museum (2007). Pages: 96. Size: 7½ x 6 inches; 1 pound. Summary: The ‘mummy portraits’ of Roman Egypt are haunting images of ancient faces: anonymous people painted by anonymous artists. And yet, they are historical and cultural documents of outstanding interest and importance, and many are of superb artistic quality. This type of portrait appeared in Egypt in the first century AD, and remained popular for around 200 years. Though the subjects believed in the traditional Egyptian cults, which offered them a firm prospect of life after death, they also wished to be commemorated in the Roman manner.

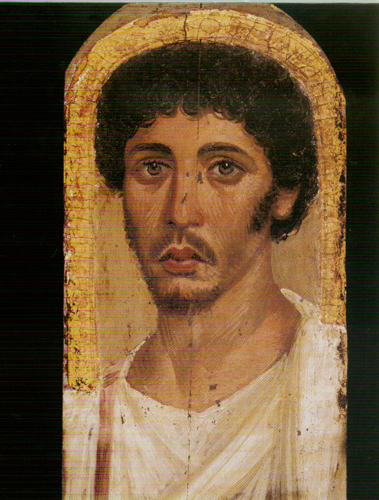

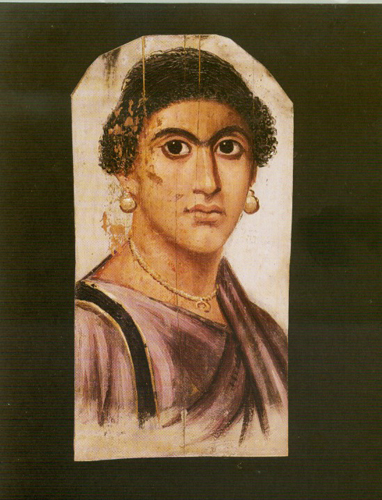

Portraits were commissioned that would serve as a realistic record of the deceased as he or she had appeared in life. These were painted on a wooden board at a roughly lifelike scale, which was then placed on the outside of the cartonnage coffin over the head of the individual or carefully placed into the mummy wrappings. The images also reveal the adoption of Roman fashions in dress and personal adornment by persons remote from the center of the empire but likely to have been actively engaged in its local administration.

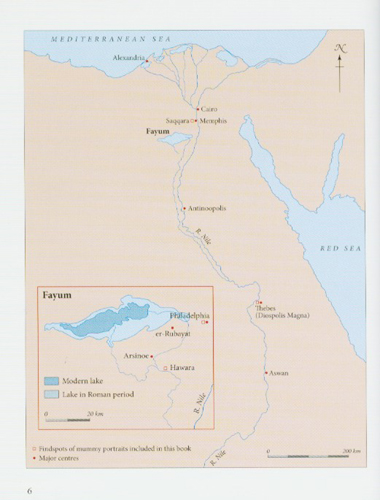

By careful assessment of the hairstyles, clothes and jewelry, it is possible to date the portraits, often within a decade or so. Many of the finest and best-known examples come from the Fayum and are a dazzling testament to the Greek painting tradition, in particular the sophistication of the Alexandrian school, from which they are derived. It is not until some fifteen centuries later, in the faces painted by Titian or Rembrandt’s depiction of his own features as he saw them reflected in a mirror, that the same artistry that characterizes many of the anonymous painters of the Fayum is witnessed again.

CONDITION: New hardcover w/dustjacket. British Museum (2007) 96 pages. Inside the book is pristine; the pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Outside the dustjacket and covers evidence faint edge and corner shelfwear, which included a 1/8 inch closed (neatly mended) edge tear at the spine head. We carefully repaired the closed edge tear from the underside of the dustjacket and touched it up with an oil-based sharpie, minimizing the prominence of this superficial cosmetic blemish. Condition is entirely consistent with new stock from an open-shelf bookstore environment (such as Barnes & Noble, or B. Dalton, for example) wherein new books might show minor signs of shelfwear/browsing/shopwear or minor superficial cosmetic blemishes, consequence of simply being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! #8735b.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: The Graeco-Roman mummy portraits remain one of the British Museum's popular and intimate collections. This compact book presents glorious color photos of some of the best, alongside commentary and a more general introduction to the techniques and practice of the portraiture.

REVIEW: Beautifully illustrated concise introduction to the remarkable painted portraits of Egypt’s Roman period, based on the British Museum’s important collection.

REVIEW: Paul Roberts is a curator of Roman antiquities at the British Museum. He is the author of a number of books and has contributed to volumes about the mummy portraits of Roman Egypt. He also lectures on the subject. He helped to research and organize the 1997 Ancient Faces exhibition at the British Museum.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Introduction.

Portraits from Hawara.

Portraits from er-Rubayat.

Portraits from other Sites.

Chronology.

Further Reading.

Illustrationd References.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: The catalogue “Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt”, originally published in 1997 in conjunction with the exhibition at The British Museum, has been newly revised to accompany the presentation at the Metropolitan. The updated catalogue, which has been edited by Susan Walker and expanded to include several examples in North American collections and which is also published by British Museum Press.

During the first through the third century A.D., a unique art form — the mummy portrait — flourished in Roman Egypt. Stylistically related to the tradition of Greco-Roman painting, but created for a typically Egyptian purpose — inclusion in the funerary trappings of mummies — these are startlingly realistic portraits of men and women of all ages. More than 70 of the finest mummy portraits from European and North American collections will be on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art this spring in "Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt". These rare and fragile works, including the Metropolitan's entire collection of mummy portraits, will not travel as a group to any other venue.

Also on view will be a range of objects — including jewelry, papyri, sculpture, and wrapped mummies — illustrating the culture and funerary customs of the time. Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum, commented: "Created nearly 2,000 years ago and, until recently, all but overlooked by scholars and the public alike, these ancient faces still engage the modern viewer by the directness of their gaze and their evocation of a long-gone society. The athletes, learned men and women, soldiers, and priests, children, adolescents, and old people are rendered in rich colors with the freshness of yesterday."

The Metropolitan's presentation of "Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt" is the result of a collaboration with the British Museum, which organized a similar exhibition in 1977. With that groundwork, a new selection of objects has been chosen for the New York presentation. The full range of mummy portrait techniques — encaustic and tempera on wood panels, tempera paintings on linen, and painted masks and coffins of plaster and cartonnage — will be represented in the exhibition, which is organized thematically and chronologically. The exhibition will begin with an introduction to Roman Egypt, from everyday life to religious beliefs and funerary customs. The exhibition is the third in a series of four offered at the Metropolitan in 1999-2000 focusing on the art of Egypt.

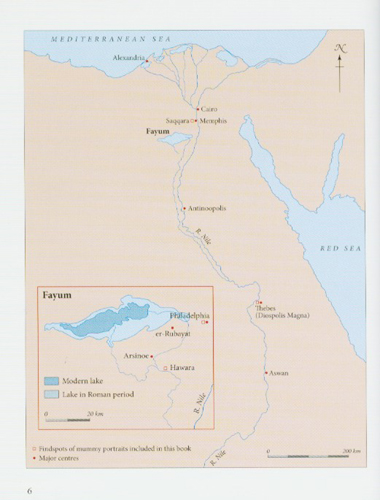

After the battle of Actium and the death of Cleopatra VII (30 B.C.), Egypt became part of the Roman Empire. The importance of the new province was expressed by its special status as the personal estate of the emperor, ruled by a prefect. Rome's interest in Egypt was, to a large degree, economic: the fertile lands along the Nile were capable of producing a rich surplus of foodstuffs, especially grain, that became essential in feeding the populace of the city of Rome. Moreover, the port of Alexandria exported Egypt's manifold manufactured goods, such as papyrus, glass, and other luxury articles, while the Nile and the desert routes linking it with the Red Sea provided trade connections with inner Africa, the Arabian peninsula, and India. Egypt's deserts also furnished a great variety of minerals, ores, and hard stones. The beneficiaries of such advantageous economic conditions were — for a while, at least — not only the Roman rulers but also a rich upper class of landowners and merchants in Egypt itself, consisting of a complex mixture of indigenous Egyptians and descendents of people from countries all around the eastern Mediterranean who had settled in the Nile Valley and oases (such as the Fayum) during the rule of the Ptolemies (332-30 B.C.).

The truly multicultural population, especially in the cities of Roman Egypt, provided a fertile ground for phenomena such as the painted panel portraits on mummies. In their artistic style and technique, the portraits on wood panels followed the Greek painting tradition of depicting the subject in three-quarter view, with a single light source casting realistic shadows and highlights on the face. Indeed, since practically no panel paintings from the Greek world have been preserved, the mummy portraits — conserved by Egypt's arid climate — are the only examples of an art form that ancient literary sources place among the highest achievements of Greek culture. Besides style and technique, the clothing, hairstyles, and jewelry worn by the individuals represented in the panel portraits display fashions that were prevalent in the whole Roman Empire — most likely under strong influences from the imperial court at Rome — but also incorporating special eastern Mediterranean idiosyncrasies, such as a profusion of curls in some of the female hairdos. None of these styles and fashions had any connection with traditional Egyptian customs. In short, taken by themselves, the encaustic panel portraits appear to have no links with Pharaonic Egypt.

Seen in their original context, however, the character of the painted portraits changes. Placed over the faces and fastened into the linen wrappings of Egyptian mummies, the portraits demonstrate clearly that the seemingly Greco-Roman individuals represented in the paintings adhered to traditional Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife. Strong ties to the traditional Pharaonic religion can also be deduced from the popularity of Hawara as a burial place for panel portrait mummies. This site, at the entrance to the Fayum oasis, was the place of the pyramid and mortuary temple of the Middle Kingdom Pharaoh Amenemhat III (ca. 1844-1797 B.C.). Greek authors called the temple the "labyrinth," describing statues of "monsters" — that is, crocodile and other animal-headed deities — still standing in their chapels in the first century A.D. The wish to be buried in such a place signals not only veneration of Egyptian deities, but a deep-seated need for a connection to the traditional religion and culture.

Scholars recently have described the society for whose members the mummy portraits were painted as one in which the individual played a number of different roles, according to their activities and functions. People may have felt as Greeks in the gymnasium, as Romans in administrative roles, and as Egyptians in their village communities, and when venerating the gods or contemplating the afterlife. This situation must have caused considerable tension in the society, but it may be one of the factors that make the painted portraits such important works of art. A present-day artist, Euphrosyne C. Doxiadis, succinctly described this aspect of the paintings in the exhibition catalogue: "Of these two strands [the Greek painting tradition and Egyptian funerary beliefs], the sophistication of the first and the intensity of the second combined to produce moments of breathtaking beauty and unsettling presence."

The technique used in painting the majority of mummy portraits is called encaustic (Greek for "burnt in"). This term, used by ancient authors, is somewhat misleading, because heat is not absolutely necessary to attain the effects seen in the encaustic panels. Therefore, encaustic has come to mean any painting method in which pigment is mixed with beeswax. Researchers have found that a great variety of methods were used to achieve the desired effects in the encaustic paintings: hot or cold wax, under-painting with various colors, and a variety of soft or hard tools that were used cold or heated. To the modern viewer, part of the attraction of encaustic paintings is their similarity to oil painting, since the wax medium could be applied in thick layers showing a great variety of tool marks and free brush strokes. An important characteristic of encaustic mummy portraits is the use of wafer-thin gold leaf. In some pieces, the entire background is gilded; in others, wreaths and fillets are added, and jewelry and garment decoration is emphasized.

The technique used in painting the majority of mummy portraits is called encaustic (Greek for "burnt in"). This term, used by ancient authors, is somewhat misleading, because heat is not absolutely necessary to attain the effects seen in the encaustic panels. Therefore, encaustic has come to mean any painting method in which pigment is mixed with beeswax. Researchers have found that a great variety of methods were used to achieve the desired effects in the encaustic paintings: hot or cold wax, under-painting with various colors, and a variety of soft or hard tools that were used cold or heated. To the modern viewer, part of the attraction of encaustic paintings is their similarity to oil painting, since the wax medium could be applied in thick layers showing a great variety of tool marks and free brush strokes. An important characteristic of encaustic mummy portraits is the use of wafer-thin gold leaf. In some pieces, the entire background is gilded; in others, wreaths and fillets are added, and jewelry and garment decoration is emphasized.

Another painting technique found in mummy panel portraits is tempera, in which pigments are mixed with water-soluble binding agents, most frequently animal glue. Tempera portraits are painted on light or dark grounds in bold brush strokes and fine hatching and cross-hatching. Their surface is matte, in contrast to the glossy surface of encaustic paintings. This style of painting — which has antecedents in ancient Egyptian painting of Pharaonic times — calls for sure draftsmanship, and has been described as "calligraphic." Since the faces in tempera paintings usually are shown frontally, and the complex treatment of light and shadow is less prominent than in the encaustic works, tempera painting may be linked more closely to indigenous Egyptian artistic traditions. There are, however, many indications that the mummy portrait painters using the tempera technique were strongly influenced by the paintings in encaustic. In addition, some works were created in a mixed encaustic and tempera technique. It is not known whether the same painters used all of the methods (encaustic, tempera, and mixed).

Mummy portrait panels consisted of a variety of woods — indigenous (sycamore), imported (cedar, pine, fir, cypress, oak), and possibly imported, but also growing in Egypt at the time (lime, fig, and yew). Some portraits are painted on linen stiffened by glue. Various styles are discernible inside the two main categories of encaustic and tempera paintings. In some cases, a particular style of painting can be linked to a particular place. Paintings on mummies found at Hawara and er-Rubayat (the cemetery of ancient Philadelphia) are the largest groups, and since both places are located in the Fayum region, this has led to the practice of calling all mummy paintings "Fayum portraits." Other important groups were excavated at Antinoopolis, Memphis, Thebes, and various places along the Nile in the vicinity of the Fayum. The mere fact that both encaustic and tempera paintings have been found at er-Rubayat shows that not all portraits found in a cemetery were painted by artists of the same school.

Literary sources indicate that mummies could, on occasion, be transported over rather far distances. There is also evidence for traveling artists. The most obvious regionally confined traits, finally, concern the shape into which the panels were cut, an observation that has more to do with burial customs than painting style, because most of the cuttings were made just before the piece was attached to the mummy. Nevertheless, it is possible, to some extent, to consider artistic peculiarities among a localized group of portraits as constituting the style of that region. Antinoopolis paintings, for example, are characterized by a striking austerity in the representation of the individuals, while the encaustic painters of the Fayum sites show the richest palette and greatest sophistication in juxtaposing light and shadow.

Unmistakable stylistic differences also exist between portraits of different dates, and the dating of mummy portraits is a hotly debated subject among scholars. There is general consensus, however, that mummy portrait painting began around 30-40 A.D. The dates of encaustic pieces from this period to the beginning of the third century are fairly well established on the basis of the hairstyles and jewelry worn by the persons represented in the paintings. The dates of some major tempera paintings are still under discussion, however, as some scholars believe they continued to be painted through the fourth century. In this exhibition and its catalogue, the more convincing earlier dates for the tempera pieces are used.

In Ancient Faces, the encaustic panel paintings will be presented in chronological groups, separating the colorful, very painterly Julio-Claudian panels (35-68 A.D.), which seem to capture a fleeting moment, from the full-blooded Flavian (69-96 A.D.), and the sculptural Trajanic (96-117 A.D.) paintings. A number of very striking images from the period of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 A.D.) show interesting differences between the works from the Fayum and those from Antinoopolis, a city founded by Hadrian in 130 A.D. The following Antonine period (138-192 A.D.) was a peak in the painting of mummy portraits, with many unforgettable images, such as the priest of Serapis (cat. 21), the young man from the Munich Antikensammlung (cat. 19), the young man from Berlin (cat. 39), and a number of the Museum's own portraits (cat. 69-71), all masterpieces of characterization through paint.

Some late Antonine to early Severan pieces from the turn of the second to the third century include a boy's portrait from the Getty Museum (cat. 61) and a bearded man from the Louvre (cat. 54), the latter again from Antinoopolis. Since the later first century, but especially during the Antonine period, tempera paintings appear parallel to those in encaustic. These take an important place also during the last period of mummy portrait painting, the first half of the third century with highlights such as two panels with young boys' images from the Brooklyn Museum of Art (cat. 44-45) and a man with a short beard from the Getty Museum (cat. 47).

Linen shrouds wrapped around mummies were painted with representations of full-length figures, usually in tempera, or in a mixture of tempera and encaustic. Some shrouds will be shown side-by-side with the contemporary panels. One especially beautiful shroud and a fragment of another, both from the Louvre, are among the latest objects in the exhibition. On the more complete shroud (cat. 99), which is from Antinoopolis, a woman is pictured wearing a purple dalmatic (a wide-sleeved garment) and holding in her left hand an Egyptian ankh (life) symbol; she lifts her right hand, palm open, in a gesture of protection and veneration known from images of Isis. The catalogue entry describes this image aptly as a perfect illustration "that the fourth century was a...period of transition between paganism and Christianity."

Placing a painted portrait on the face of a mummy, or wrapping the entire body into a painted shroud, were not the only forms of artistic funerary outfit common in Roman Egypt. At Hawara, for instance, not only paintings were found covering the heads of mummies, but also gilded and painted sculptural head-, breast-, and arm pieces made of cartonnage, a mixture of linen and glue. These mummy covers, although direct descendants of Pharaonic head and body covers of the same material, were, in Roman times, molded to show the person in Greco-Roman hairstyle and clothing, wearing jewelry very much like that seen in the paintings. Two examples of such mummy covers will be in the exhibition (cat. 27 and 28).

Another type of mummy cover especially common in, but not confined to, Middle Egypt, incorporated faces and even fully raised heads of molded clay or plaster. The Museum's complete mummy of Artemidora from Meir in southern Middle Egypt (cat. 85) is an especially impressive example. Other headpieces of a similar type and a number of detached heads serve to show the range of possibilities in this genre. Some heads are very stylized, but others are astonishingly personal recreations of real human beings. Significantly, the influences from Greek art are more evident in the idealized portraits than they are in the realistic examples, precluding the simple equation of Egyptian with idealization, and Greek with realism. Links with Pharaonic art and religion are especially strong in the painted decorations on the sides of many of the mummy head covers, where scenes and deities connected with the Egyptian afterlife and its cosmic aspects are depicted. On the bodies of mummies, such as the one of Artemidora, figures of Egyptian gods are applied, cut from sheet gold.

Still another, rather late form of preparing a Roman-era mummy is represented in the exhibition by the late-third-century A.D. mummy of a woman with a molded and painted plaster and linen mask, excavated by the Museum's expedition to Thebes (Luxor) in 1923-24. Together, these examples of Roman-period funerary art testify to the diversity of existing styles that were available to the inhabitants of Egypt regionally, and as a matter of choice. Portrait painting on wood panels in encaustic and tempera is thus given its proper place as one possibility among many others to confront death and the afterlife.

News of the existence of mummy portraits reached Europe in the mid-17th century, when Pietro della Valle (1586-1652) published an account of his travels to Persia and India by way of Egypt. Although the two mummy portraits he acquired in Saqqara (outside Cairo) were described and depicted in the book, they were perceived as curiosities rather than works of art. Another two centuries would elapse before mummy portraits would attract a sustained level of attention in Europe. Archaeological excavations by the British and the French early in the 19th century yielded additional portraits, but it took several extensive finds late in the century to pique the interest of scholars and connoisseurs.

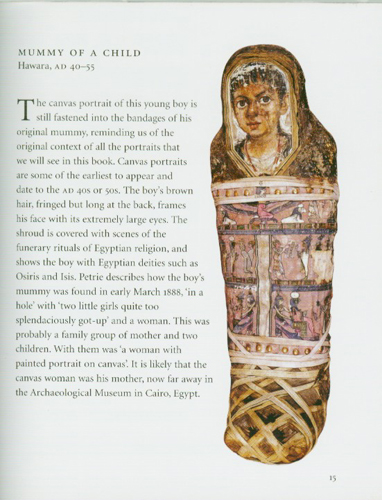

In 1887, inhabitants of the area near el-Rubayat (in the Fayum) discovered and excavated numerous mummies with portraits. Purchased immediately by Theodor Graf (1840-1903), an Austrian businessman, these works were exhibited in various European cities and in New York before being sold to buyers worldwide. In 1888-89, the noted British archaeologist W. M. Flinders Petrie (1853-1942) discovered a major Roman-period cemetery at Hawara (also in the Fayum), the burial site of many mummies with finely rendered, mainly encaustic portraits. The importance of the Hawara find cannot be overstated, as most of the mummy portraits now in the United Kingdom were discovered there by Petrie. In the 1890s, a German expedition to Hawara was mounted, and Petrie himself returned in 1911.

In the decades that followed, however, public as well as scholarly interest in mummy portraits waned. Egyptologists devoted their investigations to the art of the pharaohs, while scholars of Greek and Roman art considered the mummy portraits an expression of Egyptian art, and therefore outside their purview. With the rise of interdisciplinary studies came renewed interest in Roman Egypt, and mummy portraits have once again attracted general interest and attention. Subsequent excavations at sites such as Fag el-Gamus, el-Hibeh, Antinoopolis, Akhmim, and most recently Marina el-Alamein suggest that mummy portraits actually were known throughout much of Egypt, so that the term "Fayum portraits" is no longer valid. [New York Metropolitan Museum of Art][.

REVIEW: A most remarkable publication of the most remarkable and unforgettable ancient art. Art has always served as the most profound and pure communication form, a frozen fragment of time that allows people of the future to peek in the past. With the help of art, we’ve learned how our ancestors looked, lived, loved and suffered. Another reason to cherish and appreciate art are the paintings popularly known as the Fayum Mummy portraits. The wooden panels date to the first century BC and show startlingly realistic portraits of ancient faces from the Coptic Period. The almost disturbingly lifelike portraits belong to the tradition of panel painting, one of the most appreciated forms of art in the Classical world. Some art historians regard these portraits as the very first form of modernist painting.

The Fayum portraits, painted with tempera and wax on wooden boards, were attached to the mummies, covering the faces of bodies prepared for burial. These mummy portraits have been discovered across Egypt, but most of them were found in the Faiyum Basin (hence the common name). However, the term “Faiyum Portraits” is commonly thought as a stylistic more than geographic description. Although in pharaonic times the painted cartonnage was a common custom, The Faiyum Portraits were an artistic form dating to the Coptic period, when Egypt was under the occupation of the Roman Empire. As an artistic form, the portraits more likely derive more from the Greco- Roman traditions than the Egyptian one.

The portraits, now all detached from their owners, were mounted into the bands of cloth used to wrap the bodies. The naturalistic portraits create an astonishing opportunity to analyze the faces from 2000 years ago. Until now, about 900 Faiyum Portraits were detached from the mummies and have been displayed in various museums. The majority of them were discovered in Faiyum’s necropolis. Their incredibly intact state must be carefully preserved and maintained due to the hot and arid climate of Egypt. Recent research suggests that the production of the mummy portraits ended around the middle of the 3rd Century AD.

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: It's quite an extraordinary experience to look at 2,000 year old paintings and to see familiar faces staring back at you. In this book as Paul Roberts, the author, says "Some (portraits) are so realistic that when you look at them you recognize them as someone familiar to you: a neighbor, a relative, a friend, even a film star". This book was originally designed by the British Museum to accompany their exhibit on these ancient portraits, and at 96 pages long, you can't help but think that this is a tourist souvenir, but there's much more to it than that. It contains 51 illustrations all in all, which display the various mummies recovered from Roman Egypt from places such as Hawara and er-Rubayat; with the portrait placed on one page and description on the other.

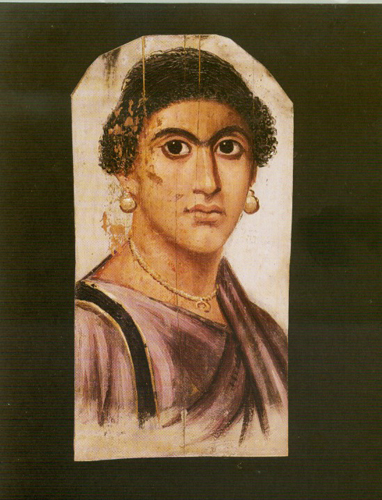

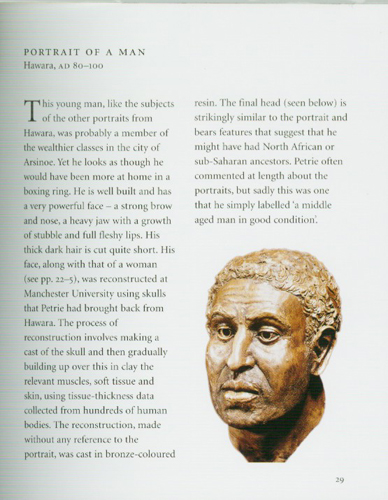

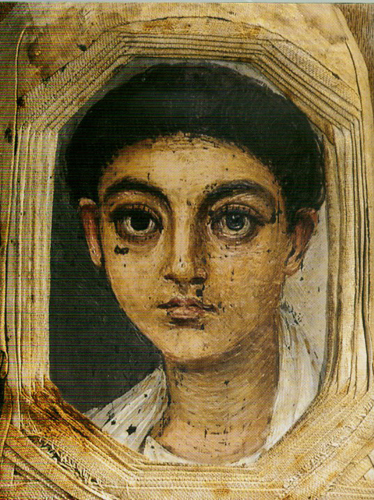

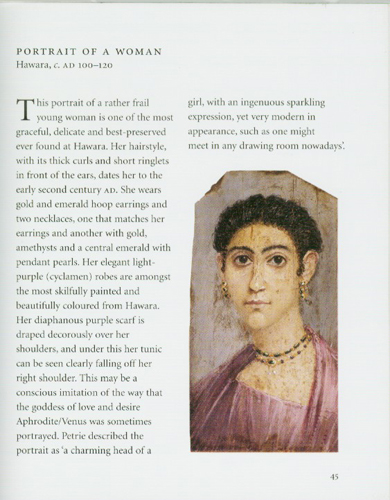

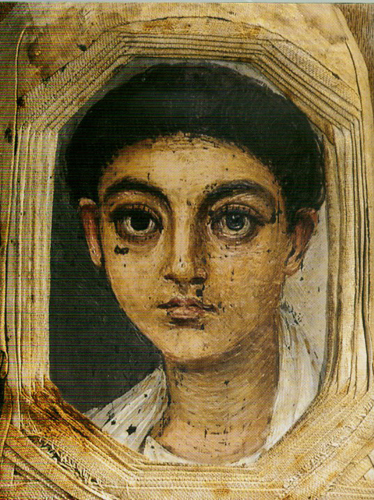

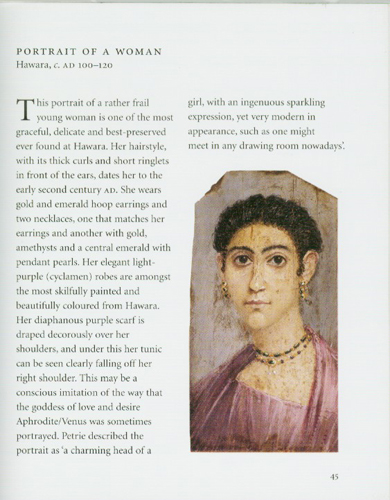

The portraits from Hawara are beautiful and evocative, and show a high degree of artistic and technical skill. The ones from er-Rubayat on the other hand seem very rushed and amateurish, but they are still fascinating. Paul Roberts provides the running commentary on each mummy portrait, while he also provides a short descriptive chapter on their discovery and origins by the English Archaeologist Sir William Petrie, some of whose comments are quoted when appropriate. One example would be a portrait of a young woman from Hawara (circa 100-120 AD) on pages 44+45 whom Petrie describes as "a charming head of a girl, with an ingenious sparkling expression, yet very modern in appearance, such as one might find in any drawing room nowadays."

This is a charming little book, full of excellent examples of ancient art, that should totally dispel the idea that realistic portraits first appeared during the Italian Renaissance. This book should serve as a fine introduction on the ancient mummy portraits, although a more in-depth book is Susan Walker and Morris Bierbier's excellent 'Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt'.

REVIEW: A fascinating book with wonderful evocative and realistic portraits from Roman Egypt with enough commentary to be interesting and informative without overwhelming the reader with excessive detail. I now want to see these portraits in person!

REVIEW: Nice book, good reproductions, good quality binding and layout.

REVIEW: Excellent little book on encaustic history in Roman Egypt.

REVIEW: Five stars! Made me want to get out my paints.

REVIEW: Five stars! Great illustrations, moving.

REVIEW: Five stars! Absolutely loved it.

REVIEW: Five stars! Great book, vivid portraits almost come to life.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

REVIEW: The pigment Egyptian blue has been found hidden in Roman-era Egyptian mummy portraits by a team of scientists from Northwestern University and the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. In visible light, only the colors yellow, white, black, and red can be seen by the naked eye in the paintings, which were discovered at the turn of the twentieth century at the site of Tebtunis in the Fayum region of Egypt. “But when we started doing our analysis, all of a sudden we started to see strange occurrences of this blue pigment, which luminesces. We concluded that although the painters were trying hard not to show they were using this color, they were definitely using blue,” Marc Walton of Northwestern University said in a press release. Roman-era painters emulated Greek art by using the Greek palette of yellow, white, black, and red, and not the man-made blue pigment. “We are speculating that the blue has a shiny quality to it, that it glistens a little when the light hits the pigment in certain ways. The artists could be exploiting these other properties of the blue color that might not necessarily be intuitive to us at first glance,” he said. [Archaeological Institute of America].

REVIEW: A Northwestern University team led by archaeological scientist Marc Walton has carried out a cutting-edge study of 15 Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits from the site of Tebtunis in Egypt. Using imaging technologies and pigment analysis, the group made a number of discoveries, including the fact that three of the portraits probably came from the same workshop and were possibly done by the same artist. They were also able to pinpoint the sources for the pigments used in the portraits. “Our materials analysis provides a fresh and rich archaeological context for the Tebtunis portraits, reflecting the international perspective of these ancient Egyptians,” Walton said in a Northwestern University press release. “For example, we found that the iron-earth pigments most likely came from Keos in Greece, the red lead from Spain, and the wood substrate on which the portraits are painted came from central Europe. We also know the painters used Egyptian blue in an unusual way to broaden their spectrum of hues.” [Archaeological Institute of America].

REVIEW: The rich lands of Egypt became the property of Rome after the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 B.C., which spelled the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty that had ruled Egypt since the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.. After the murder of Gaius Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., the Roman Republic was left in turmoil. Fearing for her life and throne, the young queen joined forces with the Roman commander Mark Antony, but their resounding defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. brought the adopted son and heir apparent of Caesar, Gaius Julius Octavius (Octavian), to the Egyptian shores. Desperate, Cleopatra chose suicide rather than face the humiliation of capture. According to one historian, she was simply on the wrong side of a power struggle.

Rome’s presence in Egypt actually predated both Julius Caesar and Octavian. The Romans had been involved periodically in Egyptian politics since the days of Ptolemy VI in the 2nd century B.C.. The history of Egypt, dating from the ousting of the Persians under Alexander through the reign of the Ptolemys and the arrival of Julius Caesar, saw a nation suffer through conquest, turmoil, and inner strife. The country had survived for decades under the umbrella of a Greek-speaking ruling family. Although a center of culture and intellect, Alexandria was still a Greek city surrounded by non-Greeks. The Ptolemys, with the exception of Cleopatra VII, never traveled outside the city, let alone learn the native tongue. For generations, they married within the family, brother married sister or uncle married niece.

Ptolemy VI served with his mother, Cleopatra I, until her unexpected death in 176 B.C.. Despite having serious troubles with a brother who challenged his right to the throne, he began a chaotic rule of his own. During his reign, Egypt was invaded twice between 169 and 164 B.C. by the Seleucid king Antiochus IV; the invading army even approached the outskirts of the capital city of Alexandria; however, with the assistance of Rome, Ptolemy VI regained token control. While the next few pharaohs made little if any impact on Egypt, in 88 B.C. the young Ptolemy XI succeeded his exiled father, Ptolemy X. After awarding both Egypt and Cyprus to Rome, Ptolemy XI was placed on the throne by the Roman general Cornelius Sulla and ruled with his step-mother Cleopatra Berenice until he murdered her. Ptolemy XI’s ill-advised relationship with Rome caused him to be despised by many Alexandrians, and he was therefore expelled in 58 B.C.. However, he eventually regained the throne but was only able to remain there through kickbacks and his ties to Rome.

When the Roman commander Pompey was soundly defeated by Caesar in 48 B.C. at the Battle of Pharsalus, he sought refuge in Egypt; however, to win the favor of Caesar, Ptolemy VIII killed and beheaded Pompey. When Caesar arrived, the young pharaoh presented him with Pompey’s severed head. Caesar reportedly wept, not because he mourned Pompey’s death but supposedly had missed the chance of killing the fallen commander himself. Also, according to some sources, in his eyes, it was a disgraceful way to die. Caesar remained in Egypt to procure the throne for Cleopatra as Ptolemy’s actions had forced him to side with the queen against her brother. With the defeat of the young Ptolemy, the Ptolemaic kingdom became a Roman client state, but immune to any political interference from the Roman Senate. Visiting Romans were treated well, even 'pampered and entertained' with sightseeing tours down the Nile. Unfortunately, there was no saving one Roman who accidentally killed a cat - sacred by tradition to the Egyptians - he was executed by a mob of Alexandrians.

History and Shakespeare have recounted ad nauseum the sordid love affair between Caesar and Cleopatra; however, his unexpected assassination forced her to seek help in safeguarding her throne. She chose incorrectly; Anthony was not the one. His arrogance had brought the ire of Rome. Anthony believed Alexandria to be another Rome, even choosing to be buried there next to Cleopatra. Octavian rallied the citizens and Senate against Antony, and when he landed in Egypt, the young commander became the master of the entire Roman army. His victory over Antony and Cleopatra awarded Rome with the richest kingdom along the Mediterranean Sea. His future was guaranteed. The country’s overflowing granaries were now the property of Rome; it became the 'breadbasket' of the empire, the 'jewel of the empire’s crown.' However, according to one historian, Octavian believed that Egypt was now his own private kingdom, he was the heir of the Ptolemaic dynasty, a pharaoh. Senators were even prohibited from visiting Egypt without permission.

With the end of a long civil war, Octavian had the loyalty of the army and in 29 B.C. returned to Rome and the admiration of its people. The Republic had died with Caesar. With Octavian - soon to be acclaimed as Augustus - an empire was born. It was an empire that would overcome poor leadership and countless obstacles to rule for almost five centuries. He would restore order to the city, becoming its 'first citizen,' and with the blessing of the Senate, govern without question. Upon his triumphant march into the city, the emperor displayed the spoils of war. The conquering hero adorned in a gold-embroidered toga and flowered tunic rode through the city streets in a chariot drawn by four horses. Although Cleopatra was dead (he had hoped to display and humiliate her in public), an effigy of the late queen, reclining on a couch, was placed on exhibit for all to see. The queen’s surviving children, Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus (Caesarion had been executed), walked in the procession. Soon afterwards, Augustus ordered the immediate construction of both a temple deifying Caesar (built on the spot where he had been cremated) and a new Senate house, the Curia Julia; the old one had been torched following Caesar’s funeral.

Emperor Augustus took absolute control of Egypt. Although Roman law superseded all legal Egyptian traditions and forms, many of the institutions of the old Ptolemaic dynasty remained with a few fundamental changes in its administrative and social structure. The emperor quickly filled the ranks of the administration with members of the equestrian class. With a flotilla on the Nile and a garrison of three legions or 27,000 troops (plus auxiliaries), the province existed under the leadership of a governor or prefect, an appointee (as were all major officials) of the emperor. Later, since the region saw few outside threats, the number of legions was reduced. Strangely, the first governor, Cornelius Gallus, unwisely made 'grandiose claims' about his victorious campaign into the neighboring Sudan. Augustus was not happy, and the governor mysteriously committed suicide - the area’s frontier would thereafter remain fixed.

Egyptian temples and priesthoods kept most of their privileges, although the imperial cult did make an appearance. While the mother-city of each region was permitted partial self-government, the status of many of the province’s major towns changed under Roman occupancy with Alexandria (the city’s population would reach 1,000,000) enjoying the greatest concessions. Augustus maintained a registry of the 'Hellenized' residents of each city. Non-Alexandrians were simply referred to as Egyptians. Rome also introduced a new social hierarchy, one with serious cultural overtones. Hellenic residents - those with Greek ancestry - formed the socio-political elite. The citizens of Alexandria, Ptolemais, and Naucratis were exempt from a newly introduced poll-tax while the 'original settlers' of the mother-cities were granted a reduced poll-tax.

The main cultural separation was, as always, between the Hellenic life of the cities and the Egyptian-speaking villages; thus, the bulk of the population remained, as it had been, the peasants who worked as tenant farmers. Much of the food produced on these farms was exported to Rome to feed its ever-growing population. As it had for decades, the city needed to import food from its provinces – namely Egypt, Syria, and Carthage - to survive. The food, together with luxury items and spice from the east, ran down the Nile to Alexandria and then to Rome. By the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., large private estates emerged operated by the Greek landowning aristocracy.

Over time this strict social structure would be questioned as Egypt, Alexandria especially, saw a significant change in its population. As more Jews and Greeks moved into the city, problems arose that challenged the patience of the emperors in Rome. The reign of Emperor Claudius (41-54 A.D.) saw riots emerge between the Jews and the Greek-speaking residents of Alexandria. His predecessor, Caligula, stated that the Jews were to be pitied, not hated. Later, under Emperor Nero (54-68 A.D.) 50,000 were killed when Jews tried to burn down Alexandria’s amphitheater – two legions were necessary to quell the riot.

Initially, Egypt was accepting of Roman control. Its capital of Alexandria would even play a major role in the ascendancy of one of the empire’s most famous emperors. After the suicide of Nero in 68 A.D., four men would vie for the throne – Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian – in what became known as the Year of the Four Emperors. In the end, the battle fell to Vitellius and Vespasian. With hopes of delaying valuable shipments of grain to Rome, Vespasian traveled to Alexandria. At the same time, Mucianus, a Roman commander and ally of Vespasian, marched into Rome. The defeated Vitellius was captured, and while pleading for his life, dragged through the streets, tortured, and killed. His body was thrown into the Tiber. Still in Alexandria, the armies of Vespasian unanimously declared him emperor.

In 115 A.D., however, there were a number of Jewish riots in Cyrenaica, Cyprus, and Egypt, voicing discontent with Roman rule and rampaging against pagan sanctuaries. The riots were eventually suppressed by Roman troops; however, thousands of Romans and Greeks were killed in what became known as the Babylonian Revolt or Kitos War. Dissatisfaction with Roman control become part of the Egyptian psyche. Until the fall of Rome in the west, revolt and chaos would haunt the Egyptian prefects. In the early 150s A.D., the Emperor Antonius Pius quelled rebellions in Mauretania, Dacia, and Egypt. Over a century later, in 273 B.C., Emperor Aurelian suppressed another Egyptian uprising. After the division of the empire under Diocletian, revolts broke out in 295 and 296 A.D..

Two major disasters hit Egypt, disrupting Roman control. The first was the Antonine plague of the 2nd century A.D., but the more serious of the two came in 270 A.D. with an invasion from the unlikely of all invaders, Queen Zenobia of Palmyra, an independent city on the border of Syria. When its king Septimus Odanathus died under suspicious circumstance, his wife took charge as regent, leading an army in the conquest of Egypt (she ousted and beheaded its prefect), Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia and proclaiming her young son Septimus Vaballathus emperor. One action that brought the ire of Rome came when she cut off the city’s corn supply. The new emperor of Rome, Aurelian, would finally defeat her in 271 A.D.. Her death, however, is shrouded in mystery. One story had the emperor bringing her to Rome as a prisoner (she was given a private villa) while another has her dying on route to the city.

When emperor Diocletian came to power in the late 3rd century A.D., he realized that the empire was far too big to be ruled efficiently, so he divided the empire into a tetrarchy with one capital, Rome, in the west and another, Nicomedia, in the east. While it would continue supplying grain to Rome (most resources were diverted to Syria), Egypt was placed in the eastern half of the empire. Unfortunately, a new capital in the east, Constantinople, became the cultural and economic center of the Mediterranean. Over time the city of Rome fell into disarray and susceptible to invasion, eventually falling in 476 A.D.. The province of Egypt remained part of the Roman/Byzantine Empire until the 7th century when it came under Arab control. [Ancient History Encylopedia].

REVIEW: Mummy portraits or Fayum mummy portraits (also Faiyum mummy portraits) is the modern term given to a type of naturalistic painted portrait on wooden boards attached to Egyptian mummies from the Coptic period. They belong to the tradition of panel painting, one of the most highly regarded forms of art in the Classical world. In fact, the Fayum portraits are the only large body of art from that tradition to have survived. Mummy portraits have been found across Egypt, but are most common in the Faiyum Basin, particularly from Hawara in the Fayum Basin (hence the common name) and the Hadrianic Roman city Antinoopolis. "Faiyum Portraits" is generally thought of as a stylistic, rather than a geographic, description. While painted cartonnage mummy cases date back to pharaonic times, the Faiyum mummy portraits were an innovation dating to the Coptic period at the time of the Roman occupation of Egypt.

The portraits date to the Imperial Roman era, from the late 1st century BC or the early 1st century AD onwards. It is not clear when their production ended, but recent research suggests the middle of the 3rd century. They are among the largest groups among the very few survivors of the highly prestigious panel painting tradition of the classical world, which was continued into Byzantine and Western traditions in the post-classical world, including the local tradition of Coptic iconography in Egypt. The portraits covered the faces of bodies that were mummified for burial. Extant examples indicate that they were mounted into the bands of cloth that were used to wrap the bodies. Almost all have now been detached from the mummies. They usually depict a single person, showing the head, or head and upper chest, viewed frontally. In terms of artistic tradition, the images clearly derive more from Greco-Roman artistic traditions than Egyptian ones.

Two groups of portraits can be distinguished by technique: one of encaustic (wax) paintings, the other in tempera. The former are usually of higher quality. About 900 mummy portraits are known at present. The majority were found in the necropoleis of Faiyum. Due to the hot dry Egyptian climate, the paintings are frequently very well preserved, often retaining their brilliant colors seemingly unfaded by time. The Italian explorer Pietro della Valle, on a visit to Saqqara-Memphis in 1615, was the first European to discover and describe mummy portraits. He transported some mummies with portraits to Europe, which are now in the Albertinum (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden).

Although interest in Ancient Egypt steadily increased after that period, further finds of mummy portraits did not become known before the early 19th century. The provenance of these first new finds is unclear; they may come from Saqqara as well, or perhaps from Thebes. In 1820, the Baron of Minotuli acquired several mummy portraits for a German collector, but they became part of a whole shipload of Egyptian artifacts lost in the North Sea. In 1827, Léon de Laborde brought two portraits, supposedly found in Memphis, to Europe, one of which can today be seen at the Louvre, the other in the British Museum. Ippolito Rosellini, a member of Jean-François Champollion's 1828/29 expedition to Egypt, brought a further portrait back to Florence. It is so similar to de Laborde's specimens that it is thought to be from the same source. During the 1820s, the British Consul General to Egypt, Henry Salt, sent several further portraits to Paris and London. Some of them were long considered portraits of the family of the Theban Archon Pollios Soter, a historical character known from written sources, but this has turned out to be incorrect.

Although interest in Ancient Egypt steadily increased after that period, further finds of mummy portraits did not become known before the early 19th century. The provenance of these first new finds is unclear; they may come from Saqqara as well, or perhaps from Thebes. In 1820, the Baron of Minotuli acquired several mummy portraits for a German collector, but they became part of a whole shipload of Egyptian artifacts lost in the North Sea. In 1827, Léon de Laborde brought two portraits, supposedly found in Memphis, to Europe, one of which can today be seen at the Louvre, the other in the British Museum. Ippolito Rosellini, a member of Jean-François Champollion's 1828/29 expedition to Egypt, brought a further portrait back to Florence. It is so similar to de Laborde's specimens that it is thought to be from the same source. During the 1820s, the British Consul General to Egypt, Henry Salt, sent several further portraits to Paris and London. Some of them were long considered portraits of the family of the Theban Archon Pollios Soter, a historical character known from written sources, but this has turned out to be incorrect.

Once again, a long period elapsed before more mummy portraits came to light. In 1887, Daniel Marie Fouquet heard of the discovery of numerous portrait mummies in a cave. He set off to inspect them some days later, but arrived too late, as the finders had used the painted plaques for firewood during the three previous cold desert nights. Fouquet acquired the remaining two of what had originally been fifty portraits. While the exact location of this find is unclear, the likely source is from er-Rubayat. At that location, not long after Fouquet's visit, the Viennese art trader Theodor Graf found several further images, which he tried to sell as profitably as possible. He engaged the famous Leipzig-based Egyptologist Georg Ebers to publish his finds.

He produced presentation folders to advertise his individual finds throughout Europe. Although little was known about their archaeological find contexts, Graf went as far as to ascribe the portraits to known Ptolemaic pharaohs by analogy with other works of art, mainly coin portraits. None of these associations were particularly well argued or convincing, but they gained him much attention, not least because he gained the support of well-known scholars like Rudolf Virchow. As a result, mummy portraits became the centre of much attention. By the late 19th century, their very specific aesthetic made them sought-after collection pieces, distributed by the global arts trade.

In parallel, more scientific engagement with the portraits was beginning. In 1887, the British archaeologist Flinders Petrie started excavations at Hawara. He discovered a Roman necropolis which yielded 81 portrait mummies in the first year of excavation. At an exhibition in London, these portraits drew large crowds. In the following year, Petrie continued excavations at the same location but now suffered from the competition of a German and an Egyptian art dealer. Petrie returned in the winter of 1910/11 and excavated a further 70 portrait mummies, some of them quite badly preserved. With very few exceptions, Petrie's studies still provide the only examples of mummy portraits so far found as the result of systematic excavation and published properly. Although the published studies are not entirely up to modern standards, they remain the most important source for the find contexts of portrait mummies.

In 1892, the German archaeologist von Kaufmann discovered the so-called "Tomb of Aline", which held three mummy portraits; among the most famous today. Other important sources of such finds are at Antinopolis and Akhmim. The French archaeologist Albert Gayet worked at Antinoopolis and found much relevant material, but his work, like that of many of his contemporaries, does not satisfy modern standards. His documentation is incomplete, many of his finds remain without context. Today, mummy portraits are represented in all important archaeological museums of the world. Many have fine examples on display, notably the British Museum, the Royal Museum of Scotland, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Louvre in Paris. Because they were mostly recovered through inappropriate and unprofessional means, virtually all are without archaeological context, a fact which consistently lowers the quality of archaeological and culture-historical information they provide. As a result, their overall significance as well as their specific interpretations remain controversial.

A majority of images show a formal portrait of a single figure, facing and looking toward the viewer, from an angle that is usually slightly turned from full face. The figures are presented as busts against a monochrome background which in some instances are decorated. The individuals are both male and female and range in age from childhood to old age. The majority of preserved mummy portraits were painted on boards or panels, made from different imported hardwoods, including oak, lime, sycamore, cedar, cypress, fig, and citrus. The wood was cut into thin rectangular panels and made smooth. The finished panels were set into layers of wrapping that enclosed the body and were surrounded by bands of cloth, giving the effect of a window-like opening through which the face of the deceased could be seen. Portraits were sometimes painted directly onto the canvas or rags of the mummy wrapping (cartonnage painting).

The wooden surface was sometimes primed for painting with a layer of plaster. In some cases the primed layer reveals a preparatory drawing. Two painting techniques were employed: encaustic (wax) painting and egg-based tempera. The encaustic images are striking because of the contrast between vivid and rich colours, and comparatively large brush-strokes, producing an "Impressionistic" effect. The tempera paintings have a finer gradation of tones and chalkier colours, giving a more restrained appearance. In some cases, gold leaf was used to depict jewellery and wreaths. There also are examples of hybrid techniques or of variations from the main techniques. The Fayum portraits reveal a wide range of painterly expertise and skill in presenting a lifelike appearance. The naturalism of the portraits is often revealed in knowledge of anatomic structure and in skilled modelling of the form by the use of light and shade, which gives an appearance of three-dimensionality to most of the figures. The graded flesh tones are enhanced with shadows and highlights indicative of directional lighting.

Under Greco-Roman rule, Egypt hosted several Greek settlements, mostly concentrated in Alexandria, but also in a few other cities, where Greek settlers lived alongside some seven to ten million native Egyptians. Faiyum's earliest Greek inhabitants were soldier-veterans and cleruchs (elite military officials) who were settled by the Ptolemaic kings on reclaimed lands. Native Egyptians also came to settle in Faiyum from all over the country, notably the Nile Delta, Upper Egypt, Oxyrhynchus and Memphis, to undertake the labor involved in the land reclamation process, as attested by personal names, local cults and recovered papyri. It is estimated that as much as 30 percent of the population of Faiyum was Greek during the Ptolemaic period, with the rest being native Egyptians. The portraits represent native Egyptians, some of whom had adopted Greek or Latin names, then seen as ‘status symbols’. Victor J. Katz notes that "most modern studies conclude that the Greek & Egyptian communities coexisted with little mutual influence". Anthony Lowsted has written extensively on the scope of Apartheid that separated the two communities during the Hellenistic, Roman & Byzantine period.

Most of the portraits depict the deceased at a relatively young age, and many show children. According to Walker, C.A.T. scans reveal a correspondence of age and sex between mummy and image. He concludes that the age distribution reflects the low life expectancy at the time. It was often believed that the wax portraits were completed during the life of the individual and displayed in their home, a custom that belonged to the traditions of Greek art, but this view is no longer widely held given the evidence suggested by the C.A.T. scans of the Faiyum mummies, as well as Roman census returns. In addition, some portraits were painted directly onto the coffin; for example, on a shroud or another part.

The patrons of the portraits apparently belonged to the affluent upper class of military personnel, civil servants and religious dignitaries. Not everyone could afford a mummy portrait; many mummies were found without one. Flinders Petrie states that only one or two per cent of the mummies he excavated were embellished with portraits. The rates for mummy portraits do not survive, but it can be assumed that the material caused higher costs than the labor, since in antiquity, painters were appreciated as craftsmen rather than as artists. The situation from the "Tomb of Aline" is interesting in this regard. It contained four mummies: those of Aline, of two children and of her husband. Unlike his wife and children, the latter was not equipped with a portrait but with a gilt three-dimensional mask. Perhaps plaster masks were preferred if they could be afforded.

Based on literary, archaeological and genetic studies, it appears that those depicted were native Egyptians, who had adopted the dominant Greco-Roman culture. The name of some of those portrayed are known from inscriptions, they are predominantly Greek. Hairstyles and clothing are always influenced by Roman fashion. Women and children are often depicted wearing valuable ornaments and fine garments, men often wearing specific and elaborate outfits. Greek inscriptions of names are relatively common, sometimes they include professions. It is not known whether such inscriptions always reflect reality, or whether they may state ideal conditions or aspirations rather than true conditions.

One single inscription is known to definitely indicate the deceased's profession (a shipowner) correctly. The mummy of a woman named Hermione also included the term grammatike (γραμματική). For a long time, it was assumed that this indicated that she was a teacher by profession (for this reason, Flinders Petrie donated the portrait to Girton College, Cambridge, the first residential college for women in Britain), but today, it is assumed that the term indicates her level of education. Some portraits of men show sword-belts or even pommels, suggesting that they were members of the Roman military.

One single inscription is known to definitely indicate the deceased's profession (a shipowner) correctly. The mummy of a woman named Hermione also included the term grammatike (γραμματική). For a long time, it was assumed that this indicated that she was a teacher by profession (for this reason, Flinders Petrie donated the portrait to Girton College, Cambridge, the first residential college for women in Britain), but today, it is assumed that the term indicates her level of education. Some portraits of men show sword-belts or even pommels, suggesting that they were members of the Roman military.

The burial habits of Ptolemaic Egyptians mostly followed ancient traditions. The bodies of members of the upper classes were mummified, equipped with a decorated coffin and a mummy mask to cover the head. The Greeks who entered Egypt at that time mostly followed their own habits. There is evidence from Alexandria and other sites indicating that they practised the Greek tradition of cremation. This broadly reflects the general situation in Hellenistic Egypt, its rulers proclaiming themselves to be pharaohs but otherwise living in an entirely Hellenistic world, incorporating only very few local elements. Conversely, the Egyptians only slowly developed an interest in the Greek-Hellenic culture that dominated the East Mediterranean since the conquests of Alexander. This situation changed substantially with the arrival of the Romans. Within a few generations, all Egyptian elements disappeared from everyday life. Cities like Karanis or Oxyrhynchus are largely Graeco-Roman places. There is clear evidence that this resulted from a mixing of different ethnicities in the ruling classes of Roman Egypt.

Only in the sphere of religion is there evidence for a continuation of Egyptian traditions. Egyptian temples were erected as late as the 2nd century. In terms of burial habits, Egyptian and Hellenistic elements now mixed. Coffins became increasingly unpopular and went entirely out of use by the 2nd century. In contrast, mummification appears to have been practised by large parts of the population. The mummy mask, originally an Egyptian concept, grew more and more Graeco-Roman in style, Egyptian motifs became ever rarer. The adoption of Roman portrait painting into Egyptian burial cult belongs into this general context.

Some authors suggest that the idea of such portraits may be related to the custom among the Roman nobility of displaying imagines, images of their ancestors, in the atrium of their house. In funeral processions, these wax masks were worn by professional mourners to emphasize the continuity of an illustrious family line, but originally perhaps to represent a deeper evocation of the presence of the dead. Roman festivals such as the Parentalia as well as everyday domestic rituals cultivated ancestral spirits (see also veneration of the dead). The development of mummy portraiture may represent a combination of Egyptian and Roman funerary tradition, since it appears only after Egypt was established as a Roman province.

The images depict the heads or busts of men, women and children. They probably date from circa 30 BC to the 3rd century. To the modern eye, the portraits appear highly individualistic. Therefore, it has been assumed for a long time that they were produced during the lifetime of their subjects and displayed as "salon paintings" within their houses, to be added to their mummy wrapping after their death. Newer research rather suggests that they were only painted after death, an idea perhaps contradicted by the multiple paintings on some specimens and the (suggested) change of specific details on others. The individualism of those depicted was actually created by variations in some specific details, within a largely unvaried general scheme. The habit of depicting the deceased was not a new one, but the painted images gradually replaced the earlier Egyptian masks, although the latter continued in use for some time, often occurring directly adjacent to portrait mummies, sometimes even in the same graves.

Together with the painted Etruscan tombs, the Lucanian tombs and the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum, the frescoes from Pompeii and Herculaneum and the Greek vases, they are the best preserved paintings from ancient times and are renowned for their remarkable naturalism. It is, however, debatable whether the portraits depict the subjects as they really were. Analyses have shown that the painters depicted faces according to conventions in a repetitive and formulaic way, albeit with a variety of hairstyles and beards. They appear to have worked from a number of standard types without making detailed observations of the unique facial proportions of specific individuals which give each face its own personality.

The religious meaning of mummy portraits has not, so far, been fully explained, nor have associated grave rites. There is some indication that it developed from genuine Egyptian funerary rites, adapted by a multi-cultural ruling class. The tradition of mummy portraits occurred from the Delta to Nubia, but it is striking that other funerary habits prevailed over portrait mummies at all sites except those in the Faiyum (and there especially Hawara and Achmim) and Antinoopolis. In most sites, different forms of burial coexisted. The choice of grave type may have been determined to a large extent by the financial means and status of the deceased, modified by local customs. Portrait mummies have been found both in rock-cut tombs and in freestanding built grave complexes, but also in shallow pits. It is striking that they are virtually never accompanied by any grave offerings, with the exception of occasional pots or sprays of flowers.

For a long time, it was assumed that the latest portraits belong to the end of the 4th century, but recent research has modified this view considerably, suggesting that the last wooden portraits belong to the middle, the last directly painted mummy wrappings to the second half of the 3rd century. It is commonly accepted that production reduced considerably since the beginning of the 3rd century. Several reasons for the decline of the mummy portrait have been suggested; no single reason should probably be isolated, rather, they should be seen as operating together. In the 3rd century the Roman Empire underwent a severe economic crisis, severely limiting the financial abilities of the upper classes. Although they continued to lavishly spend money on representation, they favoured public appearances, like games and festivals, over the production of portraits. However, other elements of sepulchral representation, like sarcophagi, did continue.

For a long time, it was assumed that the latest portraits belong to the end of the 4th century, but recent research has modified this view considerably, suggesting that the last wooden portraits belong to the middle, the last directly painted mummy wrappings to the second half of the 3rd century. It is commonly accepted that production reduced considerably since the beginning of the 3rd century. Several reasons for the decline of the mummy portrait have been suggested; no single reason should probably be isolated, rather, they should be seen as operating together. In the 3rd century the Roman Empire underwent a severe economic crisis, severely limiting the financial abilities of the upper classes. Although they continued to lavishly spend money on representation, they favoured public appearances, like games and festivals, over the production of portraits. However, other elements of sepulchral representation, like sarcophagi, did continue.

There is evidence of a religious crisis at the same time. This may not be as closely connected with the rise of Christianity as previously assumed. (The earlier suggestion of a 4th-century end to the portraits would coincide with the widespread distribution of Christianity in Egypt. Christianity also never banned mummification.) An increasing neglect of Egyptian temples is noticeable during the Roman imperial period, leading to a general drop in interest in all ancient religions. The Constitutio Antoniniana, i.e. the granting of Roman citizenship to all free subjects changed the social structures of Egypt. For the first time, the individual cities gained a degree of self-administration. At the same time, the provincial upper classes changed in terms of both composition and inter-relations.

Thus, a combination of several factors appears to have led to changes of fashion and ritual. No clear causality can be asserted. Considering the limited nature of the current understanding of portrait mummies, it remains distinctly possible that future research will considerably modify the image presented here. For example, some scholars suspect that the centre of production of such finds, and thus the centre of the distinctive funerary tradition they represent, may have been located at Alexandria. New finds from Marina el-Alamein strongly support such a view. In view of the near-total loss of Greek and Roman paintings, mummy portraits are today considered to be among the very rare examples of ancient art that can be seen to reflect "Great paintings" and especially Roman portrait painting.

Mummy portraits depict a variety of different hairstyles. They are one of the main aids in dating the paintings. The majority of the deceased were depicted with hairstyles then in fashion. They are frequently similar to those depicted in sculpture. As part of Roman propaganda, such sculptures, especially those depicting the imperial family, were often displayed throughout the empire. Thus, they had a direct influence on the development of fashion. Nevertheless, the mummy portraits, as well as other finds, suggest that fashions lasted longer in the provinces than in the imperial court, or at least that diverse styles might coexist.

Since Roman men tended to wear short-cropped hair, female hairstyles are a better source of evidence for changes in fashion. The female portraits suggest a coarse chronological scheme: Simple hairstyles with a central parting in the Tiberian period are followed by more complex ringlet hairstyles, nested plaits and curly toupées over the forehead in the late 1st century. Small oval nested plaits dominate the time of the Antonines, simple central-parting hairstyles with a hairknot in the neck occur in the second half of the 2nd century. The time of Septimius Severus was characterized by toupée-like fluffy as well as strict, straight styles, followed by looped plaits on the crown of the head. The latter belong to the very final phase of mummy portraits, and have only been noted on a few mummy wrappings. It seems to be the case that curly hairstyles were especially popular in Egypt.

Like the hairstyles, the clothing depicted also follows the general fashions of the Roman Empire, as known from statues and busts. Both men and women tend to wear a thin chiton as an undergarment. Above it, both sexes tend to wear a cloak, laid across the shoulders or wound around the torso. The males wear virtually exclusively white, while female clothing is often red or pink, but can also be yellow, white, blue or purple. The chiton often bears a decorative line (clavus), occasionally light red or light green, also sometimes gold, but normally in dark colours. Some painted mummy wrappings from Antinoopolis depict garments with long sleeves and very wide clavi. So far, not a single portrait has been definitely shown to depict the toga, a key symbol of Roman citizenship. It should, however, be kept in mind that Greek cloaks and togas are draped very similarly on depictions of the 1st and early 2nd centuries. In the late 2nd and 3rd centuries, togas should be distinguishable, but fail to occur.\

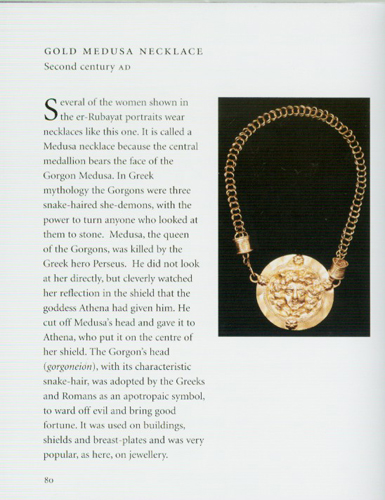

Apart from the gold wreaths worn by many men, with very few exceptions, only women are depicted with jewellery. This generally accords with the common jewellery types of the Graeco-Roman East. Especially the Antinoopolis portraits depict simple gold link chains and massive gold rings. There are also depictions of precious or semi-precious stones like emerald, carnelian, garnet, agate or amethyst, rarely also of pearls. The stones were normally ground into cylindrical or spherical beads. Some portraits depict elaborate colliers, with precious stones set in gold. The gold wreath was apparently rarely, if ever, worn in life, but a number have been found in graves from much earlier periods. Based on the plant wreaths given as prizes in contests, the idea was apparently to celebrate the achievements of the deceased in life.

There are three basic shapes of ear ornaments: Especially common in the 1st century are circular or drop-shaped pendants. Archaeological finds indicate that these were fully or semi-spherical. Later tastes favoured S-shaped hooks of gold wire, on which up to five beads of different colours and materials could be strung. The third shape are elaborate pendants with a horizontal bar from which two or three, occasionally four, vertical rods are suspended, usually each decorated with a white bead or pearl at the bottom. Other common ornaments include gold hairpins, often decorated with pearls, fine diadems, and, especially at Antinoopolis, gold hairnets. Many portraits also depict amulets and pendants, perhaps with magical functions.

The mummy portraits have immense art-historical importance. Ancient sources indicate that panel painting (rather than wall painting), i.e. painting on wood or other mobile surfaces was held in high regard. But very few ancient panel paintings survive. One of the few examples besides the mummy portraits is the Severan Tondo, also from Egypt (around 200), which, like the mummy portraits, is believed to represent a provincial version of contemporary style. Some aspects of the mummy portraits, especially their frontal perspective and their concentration on key facial features, strongly resemble later icon painting. A direct link has been suggested, but it should be kept in mind that the mummy portraits represent only a small part of a much wider Graeco-Roman tradition, the whole of which later bore an influence on Late Antique and Byzantine Art. A pair of panel "icons" of Serapis and Isis of comparable date (3rd century) and style are in the Getty Museum at Malibu; as with the cult of Mithras, earlier examples of cult images were sculptures or pottery figurines, but from the 3rd century reliefs and then painted images are found.

REVIEW: A portrait shows what an individual would have looked like. Ancient Egyptian art did not make much use of portraits, relying on an inscription containing the name and titles of an individual for identification. It was, however, important in Roman art. Portraits were placed in tombs as a memorial of family members. This type of portrait appeared in Egypt in the first century C.E., and remained popular for around 200 years. Egyptian mummy portraits were placed on the outside of the cartonnage coffin over the head of the individual or were carefully wrapped into the mummy bandages.

They were painted on a wooden board at a roughly lifelike scale. It is possible to date some mummies on the basis of the hairstyles, jewelry and clothes worn in the portrait, and to identify members of a family by their physical similarities. The accuracy of these portraits has often been questioned. Techniques employed by doctors to plan delicate facial surgery have been used to compare the actual appearance of several mummies with their portraits. This has proved that the portrait did indeed show the person as they appeared during life. However, there was some element of artistic license: for example, the mummy of Artimedorus appeared to be much more heavily built than he seemed in his portrait.

REVIEW: While mummification and traditional Egyptian religious customs remained in fashion even after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 31 BCE, funerary art forms such as this painted mummy portrait began to display an increased interest in Graeco-Roman artistic traditions. Though such mummy portraits have been found throughout Egypt, most have come from the Fayum Basin in Lower Egypt, hence the moniker “Fayum Portraits.” Many examples of this type of mummy portrait use the Greek encaustic technique, in which pigment is dissolved in hot or cold wax and then used to paint.

The naturalism of these works and the interest in realistically depicting a specific individual also stem from Greek conceptions of painting. The subjects of the majority of the Fayum Portraits are styled and clothed according to contemporary Roman fashions, most likely those made popular by the current ruling imperial family. The portrait of the bearded man, for example, is reminiscent of images of the emperor Hadrian (ruled 117–138 AD), who popularized the fashion of wearing a thick beard as symbol of his philhellenism. In their function, these mummy portraits are entirely Egyptian and reflect religious traditions surrounding the preservation of the body of the deceased that span back thousands of years. In form, these works are uniquely multicultural and display the intersection of Roman and provincial customs. [Dartmouth College].

REVIEW: Sarcophagi in human form were created as a means not only of protecting the actual body, but also as an alternate anchor for the life force, or ka, in the event that the corpse was damaged. An early development in anthropoid coffins during Egypt’s First Intermediate Period (circa 2160–2025 BC) was the introduction of face masks, placed over the heads of mummies. Images like the one seen here continue this tradition. Painted on wooden panels or linen shrouds, they were affixed over the mummy’s wrappings.

Rooted in Egyptian practices and beliefs, mummy portraits from the Fayum region of Egypt are also indebted to art of the Classical world. Created from the first through the third century CE, during Egypt’s Roman period, the images draw stylistically on Graeco-Roman models. Although they appear to be naturalistic likenesses, there is debate over whether these “portraits” are actually drawn from life. Some believe they were painted and first displayed in the home during the subject’s lifetime, while others suggest that they were produced at the time of death to be carried with the body in a procession known as the ekphora, a tradition originating in Greece.

REVIEW: Hawara became especially important in the Roman period and seems to have functioned as the elite burial ground for people of the Fayum, an area between the main Nile Valley and the desert oases. These painted panels are an important historical and artistic record. They illustrate the application of Greco-Roman art to Egyptian burial customs at the beginning of the first millennium. They appear to be naturalistic in style and be a portrait of an individual, while acting as part of the funerary equipment needed for entry into the afterlife. The panels would have covered the face of a mummy.

The image of a young man on UC19610 dates to AD 140-160 – the style of the hair and beard indicates this period – and was nicknamed by Petrie the 'Red Youth' due to the reddish-brown skin tones of the sitter. Petrie often named the images of the panels he found and wrote short character sketches. The portrait panels have been cut out of their wrappings and are displayed here separately from the physical context in which they were found. When Petrie first exhibited these panels in London in 1889, he framed many like a European art work.

This may affect how we look at these objects today. Not all panels were removed from their wrappings or mummies. The British Museum and Manchester Museum, for example, display mummies which still have these panels over their face.

REVIEW: Between 1887 and 1889, the British archaeologist W.M. Flinders Petrie turned his attention to the Fayum, a sprawling oasis region 150 miles south of Alexandria. Excavating a vast cemetery from the first and second centuries A.D., when imperial Rome ruled Egypt, he found scores of exquisite portraits executed on wood panels by anonymous artists, each one associated with a mummified body. Petrie eventually uncovered 150. The images seem to allow us to gaze directly into the ancient world. “The Fayum portraits have an almost disturbing lifelike quality and intensity,” says Euphrosyne Doxiadis, an artist who lives in Athens and Paris and is the author of The Mysterious Fayum Portraits. “The illusion, when standing in front of them, is that of coming face to face with someone one has to answer to—someone real.”

By now, nearly 1,000 Fayum paintings exist in collections in Egypt and at the Louvre, the British and Petrie museums in London, the Metropolitan and Brooklyn museums, the Getty in California and elsewhere. For decades, the portraits lingered in a sort of classification limbo, considered Egyptian by Greco-Roman scholars and Greco-Roman by Egyptians. But scholars increasingly appreciate the startlingly penetrating works, and are even studying them with noninvasive high-tech tools.