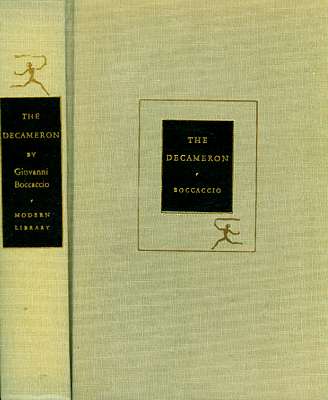

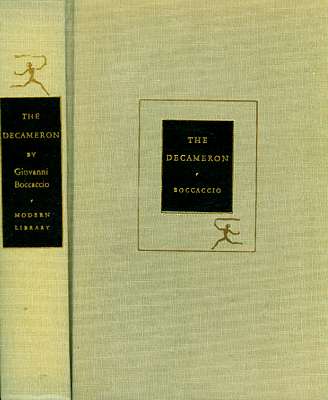

The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio Translated by Frances Winwar - Complete and Unabridged.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with Dust Jacket: 666 pages. Publisher: The Modern Library; (1955). Size: 7¼ x 5 x 1¼ inches; 1¼ pounds. The Decameron' is a fascinating example of classic literature that remains fresh and entertaining today. Written in the mid-14th century, it concerns the first major outbreak of the black plague in Europe, which emerged in Italy in approximately 1347. Boccaccio begins, in the prologue, by stating his purpose for writing the book - namely, to entertain literate women with nothing else to do with their time. The story itself concerns ten young Florentines (seven women - Pampinea, Filomena, Neifile, Fiammetta, Elissa, Lauretta, and Emilia; and three men - Panfilo, Dioneo, and Filostrato) who flee the city in hopes of escaping the plague. To occupy themselves during this time, they tell each other stories, with each person telling one story per day to make a total of 100 stories over the course of the entire book. At the beginning of the first day, Boccaccio provides an excellent and detailed description of the plague itself. The book ends with the refugees returning to their homes, and a closing epilogue from the author.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. Unread (?) vintage cloth-bound hardcover with dustjacket. Modern Library (1955) 666 pages. Book shows no evidence of ever having been read. Inside the book is pristine; pages are crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. I'd add that of course it's always possible that someone may have flipped through the book. However beyond the first dozen pages which look as if they may have been flipped through (or maybe the book started), there's absolutely no indications to book was ever read. From the outside there is first, a little discoloration/yellowing to the surfaces of the massed closed page edges. This is not visible of course on individual opened pages, only to the mass of closed page edges (sometimes referred to as the "page block").The dustjacket also shows some tanning.particularly along the edges. However the dustjacket remains remarkable well preserved. There's some abrasive rubbing to the edges, which includes a few minute chips to the dustjacket spine head and heel, though there are a few somewhat larger chips (still very small, as in 3x1mm) at the top edge of the back side of the dustjacket, right at the spine head. These couple of chips are accompanied by a bit of creasing along the edge of the dustjacket. The cloth covers are very clean, no staining or soiling, only very mild rubbing to the bottom open corners. While this might not be absolutely pristine, it's definitely in the top 1 or 2% with respect to the preservation of the book. If you'd like a clean, unread collectible/vintage copy of this remarkable account of the Plague in Medieval Europe, this is a winner. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #163a.

PLEASE SEE IMAGES BELOW FOR JACKET DESCRIPTION(S) AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

REVIEW: The Decameron is an entertaining series of one hundred stories written in the wake of the Black Death, recounted by young citizens of Florence who have fled the city in order to escape the plague. These young unmarried nobles, the "beautiful people" of the age, decide to wait out the Florentine plague in their country estates, amusing each other every evening with earthy stories, some outright bawdy, others pointing to a moral. This Italian book, written in 1351, inspired Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Balzac, and remains one of the most enjoyable anthologies of short stories ever written.

The stories portray vivid portraits of people from all stations in life in Medieval Europe, with plots that revel in a bewildering variety of human reactions. Giovanni Boccaccio was born the son of a Florentine merchant in 1313. "The Decameron", completed sometime between 1348 and 1352, was his most influential contribution to world literature, and has remained popular from its original publication to today. He died in Certaldo, Italy, in 1375.

REVIEW: The grim, solemn portrayals of humanity in most medieval art would lead us to think of the Middle Ages as a harsh, heartless time of disease, ignorance, oppressive piety, and puritanical drudgery. However "The Decameron" shows that people back then did indeed have a sense of humor, and they needed it more than ever during the Black Plague of the mid-14th Century. The book's background is an eerie reflection of the time in which it was written. Seven young ladies and three young men from Florence, Italy, depressed and frightened about the plague that is currently sweeping throughout the lands and taking large chunks out of the population, decide to escape to the countryside, camp out in vacant castles, and tell each other stories to distract themselves from the horrors of the plague and bide their time until it passes.

Each of them tells a story per day for ten days -- one hundred stories total -- and each day has an established theme which the stories told that day must follow. The stories are simple fables about love, adultery, deception, generosity, and fortune, in which stupid or gullible people are fooled, selfish people are cheated, arrogant people get their comeuppance, and smart, honest, or virtuous people are rewarded. Running the gamut from farcically ridiculous to decadently ribald to melodramatically sad, they are apparently the kinds of stories people back then probably would have found entertaining.

REVIEW: Boccaccio's unabashedly sensuous masterpiece begins with a counterpoint as the narrator moves from a description of the pain of lovesickness to the ravages of the Black Death. Set in 1348, this great piece of literature explores human nature through one hundred linked tales traded by ten youthful nobles who escape to a country estate as the Plague rages over Florence. In Boccaccio's account of this turbulent time, the veneer of traditional morality and customs has fallen by the wayside in the face of widespread sickness and death, allowing the young men and women to rule themselves. By turns witty, tender, bawdy, and wise, the narratives brilliantly reveal human nature and explore both the comedy and tragedy of life. Peopled by nobles and knights, pilgrims and peasants, doctors and nuns, lovers and gamblers, "The Decameron" is a towering monument of medieval literature.

REVIEW: For more than five centuries Giovanni Boccaccio's "The Decameron" has stood virtually unchallenged in its supremacy as the world's greatest collection of tales. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Keatts, and many other literary immortals found in these Florentine stories a never-failing inspiration and a veritable source book for plot material. To the modern reader, "The Decameron" affords undiminished stimulation and pleasure, despite the strictures and the vain attempts at suppression by meddling and squeamish censors.

REVIEW: I had to read this over 6 weeks while studying in Tuscany. It is quite humorous and interesting, however it goes against everything that I learned in Catholic school. Ironically most of the dirty deeds being done are by those who've been chosen to "spread the good word". It is fabulous however when reading it one must forget their background and dive in over the top to be able to move through the book.

REVIEW: I very much enjoyed "The Decameron". It is interesting and easy to read. The characters in the various stories are ordinary people and this makes them seem very real. Many of them actually are based on real people. Some of the stories, too, are inspired by actual events. I also liked the organization of the book, as it was always very easy to find a "stopping place". With some novels, it's hard to set them down, but since The Decameron is a collection of short stories, one can always stop at the end of any particular story and come back later. The translation is very user-friendly while still retaining the 14th century "feel" of it. The book is great fun to read. The stories are lively and colorful, and often quite humorous. It provides an excellent insight into the everyday lives of people during this time period.

REVIEW: Unlike a lot of the writers who sprang out of the medieval period, "The Decameron" is extremely readable. 100 stories organized into 10-day chunks makes this book a classic piece of literature, and unlike Chaucer's "Canterbury Tales", you don't have to wade through the language to get at the meaning (part of this has to do with the translation of Italian into modern English). During the Plague of the mid-14th century, ten people (7 women and 3 men) escape the city of Florence to the then-countryside of Fiesole.

Each day they elect a king or queen, who dictates the theme of the day's stories. Centering around love, lust, sex, and relationships between people, the stories in "The Decameron" transcend stereotypes of the Middle Ages and created a scintillating and fresh approach to the art of storytelling. "The Decameron" is one of my favorite novels; this is the second time I've read it, and it never ceases to amaze me by the depth of human life represented. In addition, this is an excellent translation of the original; the translators manage to get at Boccaccio's meaning without destroying his prose.

REVIEW: This fascinating fourteenth-century text is as complex as it is misunderstood. The premise is simple enough: the author creates a fictional set-up where, over ten days, seven female and three male characters who are cooped up in a country estate tell one another a total of 100 stories. The title, "The Decameron," literally means "ten day's work. But this framing technique of ten narrators is hardly the point. The star of this work are the tales told by these sequestered characters.

These 100 stories are chillingly sneaky in how they will mess with your mind. At first the tales will appear shocking, overtly sexual, or even knee-slappingly funny (think "Monty Python.") But in fact, like Aesop, the great Italian prose author Boccaccio tucks an ambiguous, gnawing moral into each tale. You will laugh at first, and then the bittersweet truth of each story's lesson will zap you. The true brilliance of "The Decameron" is that it is kaleidoscopic in nature: while all the tales are somewhat similar to one another, each story is truly unique in how it aligns its characters, its structure, its action, and its moral.

The basic ingredients are similar in dozens of stories, and yet their outcomes prove to be wholly different. So instead of getting "re-runs," you the reader wind up in a quicksand-like universe where some good-hearted characters are punished, others rewarded, and some scoundrels are quashed while other soar. It is Boccaccio's humorous (yet ultimately grim) portrait of our herky-jerky, you-never-know world, where a person can never be sure of his destiny despite his conduct that makes this work brilliant. Behind the ribaldry and the chuckles, this late-medieval author proves that our world (sometimes benevolent, sometimes cruel, but always inscrutable) is, indeed, nothing but a human comedy.

REVIEW: A mammoth collection of medieval tales! This mammoth collection of short stories was written in the wake of the Bubonic Plague which killed a third of the population of Europe back in the 14th century. The stories are for the most part really good narratives, and they're told through ten young noblemen who are trying to hide out from the plague to save themselves and tell these stories to pass the time. Written in a clear, classical, controlled, strongly plotted style, these are tales about sex, violence, intrigue; but nothing gratuitous of course. Good, easy-to-read translation!

The publisher, "The Modern Library" has had an enormous impact on the American literary scene. It is a classic story of American entrepreneurship, and the birth of one of the world's major publishing houses. Two generations of students bought the product of "The Modern Library" avidly. The series was first started in 1917, and was essentially a crib on the British Everyman series. The purpose of this series was to make available to the general public the "classics" of literature:the great titles by the world's greatest authors:in affordable, attractive bindings. Such works were oftentimes out of the financial reach of the average reader, books put out by other publishing houses at the time sold for around $2. The first books published by "The Modern Library" were 60 cents each. Though the price was increased to 95 cents in 1920 as costs had risen considerably, the price was to remain the same until 1946.

In 1925 two young employees purchased the rights to publish the series from the original publisher. Immediately the two young publishers set about giving their purchase a new look. Bad titles were dropped, the smelly leatherette bindings were replaced in favor of cloth, and the distinctive logo - a running torchbearer - was devised. Between 1925 and 1927 the new owners devoted their time exclusively to "The Modern Library". Not a penny was taken out of the business. Cerf and Klopfer went to the Department stores and bookshops themselves. They checked their books on the shelves themselves and made sure that the missing titles were replaced. Buyers knew that they were meeting the actual publishers and liked that. Hundreds of new outlets were found to carry their books, and sales began to soar. Their investment of $215,000 more than paid for itself within those first two years.

The Modern Library, in fact, was doing so well that the new owners found themselves with more time than what they knew to do with. They played a lot of golf and bridge, but even then there was time to spare. Cerf says, in his autobiography, he missed the exciting days of the publication of a new book. Cerf and Klopfer decided that, as a sort of hobby, they would publish deserving and underappreciated quality books they liked and at random. Thus in 1927, the publishing giant "Random House" was born. Most people think that The Modern Library is an offshoot of Random House when in fact the opposite is the truth. Random House made its debut with a pamphlet announcing the publication of seven limited editions from the Nonesuch Press, and the course of publishing history was changed.

BLACK DEATH (BUBONIC PLAGUE): The Black Death was a plague pandemic which devastated Europe from 1347 to 1352 A.D., killing an estimated 25-30 million people. The disease was caused by a bacillus bacteria and carried by fleas on rodents. The plague originated in central Asia and was taken from there to the Crimea by Mongol warriors and traders. The plague entered Europe via Italy, carried by rats on Genoese trading ships sailing from the Black Sea. It was known as the Black Death because it could turn the skin and sores black.

Other symptoms included fever and joint pains. With up to two-thirds of sufferers dying from the disease, it is estimated that between 30% and 50% of the population of those regions, towns, cities infected died from the Black Death. The death toll was so high that it had significant consequences on European medieval society as a whole. A shortage of farmers resulted in demands for an end to serfdom. There ensued a general questioning of authority, rebellions, and even the entire abandonment of many towns and villages. It would take 200 years for the population of Europe to recover to the level seen prior to the Black Death.

The plague was carried and spread by parasitic fleas on rodents, notably the brown rat. There are three types of plague, and all three were likely present in the Black Death pandemic. Bubonic plague was the most common during the 14th-century outbreak. Bubonic Plague causes severe swelling in the groin and armpits (the lymph nodes) which take on a sickening black color, hence the name the Black Death. The black sores which can cover the body in general, caused by internal hemorrhages, were known as buboes, from which bubonic plague takes its name

Other symptoms include raging fever and joint pains. If untreated, bubonic plague is fatal in between 30% and 75% of infections, often within 72 hours. The other two types of plague - pneumonic (or pulmonary) and septicemic - are usually fatal in all cases. The terrible symptoms of the disease were described by writers of the time, notably by the Italian writer Boccaccio in the preface to his 1358 “Decameron”. One writer, the Welsh poet Ieuan Gethin made perhaps the best attempt at describing the black sores which he saw first-hand in 1349: “…We see death coming into our midst like black smoke, a plague which cuts off the young, a rootless phantom which has no mercy for fair countenance. Woe is me of the shilling of the armpit…It is of the form of an apple, like the head of an onion, a small boil that spares no-one. Great is its seething, like a burning cinder, a grievous thing of ashy color…They are similar to the seeds of the black peas, broken fragments of brittle sea-coal…cinders of the peelings of the cockle weed, a mixed multitude, a black plague like half pence, like berries…” The 14th century in Europe had already proven to be something of a disaster even before the Black Death arrived. An earlier plague had hit livestock, and there had been crop failures from over-exploitation of the land. These had led to two major Europe-wide famines in 1316 and 1317. In addition there was the turbulence of wars, especially the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) between England and France. Even the weather was getting worse as the unusually temperate cycle of 1000-1300 gave way to the beginnings of a “little ice age”. During this period winters were steadily colder and longer, reducing the growing season and, consequently, the harvest.

A devastating plague affecting humans was not a new phenomenon. A serious outbreak occurred in the mid-5th century A.D. It ravaged the Mediterranean area and Constantinople in particular. The Black Death of 1347 entered Europe probably via Sicily. It seems to have been carried there by four Genoese rat-infested grain ships sailing from Caffa, on the Black Sea. The port city had been under siege by Tartar-Mongols who had catapulted infected corpses into the city. It was there the Italians had picked up the plague.

Another origin was Mongol traders using the Silk Road who had brought the disease from its source in central Asia. Genetic studies in 2011 specifically identified China as the source. However actual historical evidence of an epidemic caused by plague in China during the 14th century weak, Historians have proposed South East Asia as an alternative source. Regardless of the ultimate source, from Sicilian ports it was but a short step to the Italian mainland. Aiding the spread of the plague beyond Sicily was the fact that one of the ships from Caffa upon reaching Genoa, had been refused entry. It subsequently docked in Marseilles (France), and then Valencia Spain), Thus by the end of 1349 A.D. the disease had been carried along trade routes into France, Spain, Britain, and Ireland, which all witnessed its awful effects. Spreading like wildfire, it hit Germany, Scandinavia, the Baltic States, and Russia through 1350-1352. Medieval doctors had no idea about such microscopic organisms as bacteria. So they were helpless in terms of treatment. Doctors best chance of helping people would have been by preventing the spread of the disease. However any such efforts were hampered by the typically unsanitary living conditions which were appalling compared to modern standards.

Another helpful strategy would have been to quarantine areas. However people oftentimes fled in panic whenever a case of plague broke out. They unknowingly carried the disease with them and spread it even further. The rats did the rest. There were so many deaths and so many bodies that the authorities did not know what to do with them,. Carts piled high with corpses became a common sight across Europe. It seemed the only course of action was to stay put, avoid people, and pray. The disease finally ran its course by 1352. However it would recur again, in less severe outbreaks, throughout the rest of the medieval period.

Although it spread unchecked, the Black Death hit some areas much more severely than others. This fact and the often exaggerated death tolls of medieval [and some modern] writers means that is extremely difficult to accurately assess the total death toll. Sometimes entire cities, for example, Milan, managed to avoid significant effects, while others, such as the Italian city of Florence, were devastated. Florence lost 50,000 of its 85,000 population, a 60% death rate. Paris was said to have buried 800 dead each day at its peak.

However other localities somehow missed the carnage. On average the consensus estimate is that 30% of the population of affected areas was killed. However some historians still argue for a figure closer to 50%. Indeed this was probably the case in the worst affected cities. Figures for the death toll thus range from 25 to 30 million in Europe between 1347 and 1352. The population of Europe would not return to pre-1347 levels until around 1550.

The consequences of such a large number of deaths were severe, and in many places, the social structure of society broke down. Many smaller urban areas hit by the plague were abandoned by their residents who sought safety in the countryside. Traditional authority both governmental and religious was questioned. How could such disasters befall a people? Were not governors and God in some way responsible? Where did this disaster come from and why was it so indiscriminate? At the same time, personal piety increased and charitable organizations flourished. There were also economic consequence of enormous magnitude as well. For instance agricultural workers were in a position to demand wages rather than being bond to the land as serfs.

The Black Death was personified by the Medieval populace. In art the depiction was of the Grim Reaper, a skeleton on horseback whose scythe indiscriminately cut down people in their prime. Many people were simply bewildered by the disaster. Some thought it a supernatural phenomenon, perhaps connected to the comet sighting of 1345. Others blamed sinners. The most notably of those believers blaming sinners were the “Flagellants of the Rhineland”.

The “Flagellants” paraded through the streets whipping themselves and calling for sinners to repent so that God might lift this terrible punishment. Many thought it an unexplainable trick of the Devil. Still others blamed traditional enemies. Age-old prejudices were fed leading to attacks on, and even massacres of, specific groups who were to “blame” for the plague. This included most notably the Jews, thousands of whom fled to Poland.

Even when the crisis had passed, there were now practical problems to be faced. With not enough workers to meet needs, salaries and prices soared. The necessity of farming to feed people would prove a serious challenge. Equally serious was the huge fall in demand for manufactured goods. There were simply far fewer people to buy them. In agriculture specifically the institution of serfdom where a laborer paid rent and homage to a landlord and was bound to the land as a chattel was doomed. Those who could work were in a position to ask for wages.

Social unrest followed. Often outright rebellions broke out when the aristocracy tried to resist these new demands. Notable riots were those in Paris in 1358, Florence in 1378, and London in 1381. The peasants did not get all they wanted. A call for lower taxes for instance was a significant fail. However the old system of feudalism was gone. A more flexible, more mobile, and more independent workforce was born.

After the major famines in 1358 and 1359. There also followed occasional resurgences of the plague, albeit less severe. Those occurred in 1362-3, 1369, 1374 and 1390. Notwithstanding these events however, daily life for most people did gradually improve by the end of the 1300s. The general welfare and prosperity of the peasantry also progressed as a reduced population reduced the competition for land and resources. Land-owning aristocrats, too, were not slow to pick up the unclaimed lands of those who had perished. Even upwardly mobile peasants could consider increasing their landholdings.

Women, in particular, gained some rights of property ownership they had not had before the plague. Laws varied depending on the region. In some parts of England those women who had lost husbands were permitted to keep his land for a certain period, or until they remarried. In other, more generous jurisdictions, even if they did remarry, they did not lose their late husband's property, as had been the case prior (and in other locales).

None of these social changes can be directly linked to the Black Death itself. Indeed some were already underway even before the plague had arrived. Nonetheless the shock wave the Black Death dealt to European society was certainly a contributing and accelerating factor in the changes that occurred in society as the Middle Ages came to a close [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

BLACK DEATH IN EUROPE: Known as the “Black Death”, the outbreak of plague in Europe between 1347-1352 A.D. completely changed the world of medieval Europe. Severe depopulation upset the socio-economic feudal system of the time. But the experience of the plague itself affected every aspect of people’s lives. Disease on an epidemic scale was simply part of life in the Middle Ages. But a pandemic of the severity of the Black Death had never been experienced before. By the time the plague had run its course, there was no way for the people to resume life as they had previously known it. The Black Death altered the fundamental paradigm of European life.

Before the plague, the feudal system rigidly divided the population in a caste system of the king at the top, followed by nobles and wealthy merchants, with the peasants (serfs) at the bottom. Medical knowledge was received without question from doctors who relied on physicians of the past. The Catholic Church was the ultimate authority on spiritual matters, morality, and social norms. Women were largely regarded as second-class citizens. The art and architecture of the time reflected the people’s belief in a benevolent God who responded to prayer and supplication.

Life at this time was by no means easy, or even sometimes pleasant. However people knew – or thought they knew – how the world worked and how to live in it. The plague would change all that. It would usher in a new understanding which found expression in movements such as the Protestant Reformation and the Renaissance. The plague came to Europe from the East. It is likely that in part it was brought overland via the trade routes known as the Silk Road. It is certain that it was also brought overseas by merchant ship.

The “Black Death” was a combination of bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic plague (and also possibly a strain of murrain). It had been gaining momentum in Central Asia and the Far East since at least 1322 A.D. By 1343 the plague had infected the troops of the Mongol Golden Horde. The Mongols were besieging the Italian-held city of Caffa (modern-day Feodosia in Crimea) on the Black Sea. As Mongol troops died of the plague, their comrades had their corpses catapulted over the city’s walls, Of course this infected the people of Caffa through their contact with the decomposing corpses.

Eventually, a number of the city’s inhabitants fled the city by ship. They first arrived at Sicilian ports and then French and Spanish ports. Fro there the plague spread inland. Those infected usually died within three days of showing symptoms. The death toll rose so quickly that the people of Europe had no time to grasp what was happening, why, or what they should do about the situation. Scholar and historian Norman F. Cantor comments:

“…The plague was much more severe in the cities than in the countryside. But its psychological impact penetrated all areas of society. Neither peasant or aristocrat was safe from the disease. Once it was contracted, a horrible and painful death was almost a certainty. The dead and dying lay in the streets, abandoned by frightened friends and relatives…”

As the plague raged on all efforts to stop its spread or cure those infected failed. People began to lose faith in the institutions they had relied on previously. The social system of feudalism began to crumble due to the widespread death of the serfs. Serfs were those who were most susceptible as their living conditions placed them in closer contact with each other on a daily basis than those of the upper classes.

The plague ran rampant among the lower class who sought shelter and assistance from friaries, churches, and monasteries. They thus spread the plague to the clergy, and from the clergy it spread to the nobility. By the time the disease had run its course in 1352 A.D., millions were dead. The social structure of Europe was as unrecognizable. The urban landscape itself was unrecognizable since, as Cantor notes, “…many flourishing cities became virtual ghost towns for a time…” In rural agricultural areas crops lay rotting in the fields with no one to harvest them.

Before the plague the king owned all the land which he allocated to his nobles. The nobles had serfs work the land which turned a profit for the lord. The lord in turn paid a percentage of the profit to the king. The serfs themselves earned nothing for their labor except lodging and food they grew themselves. Since all land belonged to the king he felt free to give it as gifts to friends, relatives, and other nobility who had been of service to him. By the time of the plague every available piece of land was being cultivated by serfs under one of these lords.

On a scale relative to agricultural productions Europe was severely overpopulated. There was no shortage of serfs to work the land and these peasants had no choice but to continue this labor as they were considered chattels appurtenant to the land. This “feudal” system was in essence a form of slavery. Serfs were bound to this system, bound to the land they were appurtenant to, from the time they could walk until their death. There was no upward mobility in the feudal system and a serf was tied to the land he and his family worked from generation to generation.

However as the plague wore on depopulation greatly reduced the workforce. The serf’s labor suddenly became an important and increasingly rare asset. The lord of an estate could not feed himself, his family, or pay tithes to the king or the Church without the labor of his peasants/ The loss of so many serfs meant that the surviving peasants could now negotiate for monetary pay and better treatment. In short order the lives of the members of the lowest class vastly improved. They were able to afford better living conditions and clothing as well as luxury items.

Once the plague had passed, the improved lot of the serf was challenged by the upper class/ The nobility was concerned that the lower classes were forgetting their place. Fashion changed dramatically as the elite demanded more extravagant clothing and accessories. This was an effort to distinguish and set themselves apart from those formerly peasants and serfs who themselves now could now afford finer clothing.

Efforts of the wealthy to return the serf to his previous condition resulted in uprisings. These included the peasant revolt in France in 1358, the guild revolts of 1378, and the famous Peasants' Revolt of London in 1381. However there was no turning back. The efforts of the elite were futile. Class struggle would continue but the authority of the feudal system was broken.

The challenge to authority also affected medical knowledge and practice. Doctors based their medical knowledge primarily on the work of the Roman physician Galen (who lived from 130-210 A.D.), Hippocrates (who lived from about 460 - 370 B.C.) and Aristotle (who lived from 384-322 B.C.). Even then many of these ancient and antiquated works were only available in often poor and inaccurate translations from Arabic copies. Even so medical practitioners put to good use whatever limited knowledge they had of medicinal therapeutics and disease. As the scholar Jeffrey Singman comments: “…Medieval science was far from primitive. In fact it was a highly sophisticated system based on the accumulated writings of theorists since the first millennium B.C. The weakness of medieval science was its theoretical and bookish orientation, which emphasized the authority of accepted authors. The duty of the scholar [and doctor] was to interpret and reconcile these ancient authorities, rather than to test their theories against observed realities…” Doctors and other caregivers were seen dying at an alarming rate as they tried to cure plague victims using their traditional understanding of medicine. Despite their self-sacrifice, nothing they prescribed led to a cure for their patients. It became clear by as early as 1349 that people recovered from the plague or died from it for seemingly no reason at all. A remedy that had restored one patient to health would fail to work on the next.

After the plague, doctors began to question their former practice of accepting the knowledge of the past without adapting it to present circumstances. Scholar Joseph A. Legan writes: “…Medicine slowly began changing during the generation after the initial outbreak of Plague. Many leading medical theoreticians perished in the Plague, which opened the discipline to new ideas. A second cause for change was while university-based medicine failed, people began turning to the more practical surgeons…With the rise of surgery, more attention was given to the direct study of the human body, both in sickness and in health. Anatomical investigations and dissections, seldom performed in pre-plague Europe, were pursued more urgently with more support from public authorities…” The death of so many scribes and theoreticians, who formerly wrote or translated medical treatises in Latin, resulted in new works being written in the vernacular languages. This allowed common people to read medical texts which broadened the base of medical knowledge. Further, hospitals developed into institutions more closely resembling those in the modern-day. Previously, hospitals were used only to isolate sick people. After the plague Hospitals became centers for treatment. Hospitals also maintained a much higher degree of cleanliness and attention to patient care.

Doctors and theoreticians were not the only ones whose authority was challenged by the plague. The clergy also came under the same kind of scrutiny. Circumstances inspired people were inspired to doubt the abilities of those who served the Church to perform the services they claimed to be able to. Friars, monks, priests, and nuns died just as easily as anyone else. In some towns religious services simply stopped because there were no authorities to lead them. Further nothing helped to stop the spread of the plague.

The charms and amulets people purchased for protection did not help. The religious services they did attend, the religious processions they took part in, the prayer and the fasting, all did nothing. In fact these activities actually encouraged the spread of the plague. The Flagellant Movement began in Austria and gained momentum in Germany and France. Groups of penitents would travel town to town whipping themselves to atone for their sins,. These groups were led by a self-proclaimed Master with little or no religious training. Penitent processions not only helped spread the plague but also disrupted communities by their insistence on attacking marginalized groups such as the Jews.

Since no one knew the cause of the plague, it was attributed to the supernatural origins. These included alleged conspiratorial Jewish sorcery, and/or God’s fury over human sin. Those who died of the plague were suspected of some personal failing of faith. Yet it shortly became clear that the same clergy who condemned those who died due to their religious failings, also died of the same disease in the same way. Scandals within the Church, the extravagant lifestyle of many of the clergy, and the mounting death toll from the plague all combined to create a “perfect storm” of widespread distrust of the Church’s vision and authority.

The frustration people felt at their helplessness in the face of the plague gave rise to violent outbursts of persecution across Europe. The Flagellant Movement was not the only source of persecution. Otherwise peaceful citizens could be whipped into a frenzy to attack communities of Jews, Romani (gypsies), lepers, or others. Women were also abused in the belief that they encouraged sin because of their association with the biblical Eve and the fall of man. The most common targets, however, were the Jews.

The Jews had long been singled out for Christian hostility. The Christian concept of the Jew as “the killers of Christ” encouraged a large body of superstitions. These included the claim that Jews killed Christian children and used their blood in unholy rituals. That this blood was often spread by Jews on the fields around a town to spread the plague. And finally, that the Jews regularly poisoned wells in the hopes of killing as many Christians as possible.

Jewish communities were completely destroyed in Germany, Austria, and France. This was despite a bull issued by Pope Clement VI exonerating the Jews and condemning Christian attacks on them. Large migrations of Jewish communities fled the scenes of these massacres, many of them finally settling in Poland and Eastern Europe. Women, on the other hand, gained higher status following the plague. Prior to the outbreak, women had few rights. Scholar Eileen Power writes:

“…In considering the characteristic medieval ideas about women, it is important to know not only what the ideas themselves were but also what were the sources from which they spring…In the early Middle Ages, what passed for contemporary opinion [on women] came from two sources – the Church and the aristocracy…”

Neither the medieval Church nor the aristocracy held women in very high regard. Women of the lower classes most often worked as laborers with their family on the estate of the lord. They could also as bakers, milkmaids, barmaids, and weavers. However they had no say in directing their own fate. The lord would decide who a girl would marry, not her father. A woman would go from being under the direct control of her father, who was subject to the lord, to the control of her husband who was equally subordinate.

Women’s status had improved somewhat through the popularity of the Cult of the Virgin Mary. The cult associated women with the mother of Jesus Christ. Nonetheless the Church continually emphasized women’s inherent sinfulness as daughters of Eve. They bore responsibility for introducing sin into the world. After the plague, with so many men dead, women’s status improved to a degree.

Women were allowed to own their own land, cultivate the businesses formerly run by their husband or son, and had greater liberty in choosing a husband. Women joined guilds, ran shipping and textile businesses, and could own taverns and farmlands. In the years following the ebb of the plague, many of these rights would be diminished later as the aristocracy and the Church tried to assert their former control. Notwithstanding, women would still be better off after the plague than they were beforehand.

The plague also dramatically affected medieval art and architecture. Artistic pieces (paintings, wood-block prints, sculptures, and others) tended to be more realistic than before. And they were almost uniformly, focused on death. Scholar Anna Louise DesOrmeaux comments: “…Some plague art contains gruesome imagery that was directly influenced by the mortality of the plague. Or by the medieval fascination with the macabre and awareness of death that were augmented by the plague. Some plague art documents psychosocial responses to the fear that plague aroused in its victims. Other plague art is of a subject that directly responds to people’s reliance on religion to give them hope…” The most famous motif was the Dance of Death (also known as “Danse Macabre). The Dance of Death is an allegorical representation of death claiming people from all walks of life. As DesOrmeaux notes, post-plague art did not reference the plague directly but anyone viewing a piece would understand the symbolism. This is not to say there were no allusions to death before the plague. Only that allusions to death became far more pronounced afterwards.

In England, there was a parallel increased austerity in architectural style which can be attributed to the Black Death. There occurred a distinct shift away from the Decorated version of French Gothic. This had featured elaborate sculptures and glass. After the plague a more sparse style called Perpendicular came to predominate. This style featured with sharper profiles of buildings and corners. The Perpendicular style was less opulent, rounded, and effete than had been Decorated French Gothic. In part however the cause may have been economic. There was less capital to spend on decoration after the plague than before.

There was heavy war taxation and reduction of estate incomes due to the labor shortage and higher peasants’ wages. Since peasants could now demand a higher wage, the kinds of elaborate building projects which were commissioned before the plague were no longer as easily affordable. This resulted in more austere and cost-effective structures. Scholars have noted, however, that post-plague architecture also clearly resonated with the pervasive pessimism of the time and a preoccupation with sin and death.

It was not only the higher wages demanded by the peasant class, nor a preoccupation with death that affected post-plague architecture. The vast reduction in agricultural production and demand due to depopulation led to a profound economic recession. Fields were left uncultivated and crops were allowed to rot. At the same time, nations severely limited imports in an effort to control the spread of the plague. This had a deleterious effect not only on their own economy, but on those of their former trading partners as well.

The widespread fear of death stunned the population of Europe at the time/ Particularly in that it was death one had not earned, could not see coming, could not escape. Once the populace had somewhat recovered from that shock, they were inspired to rethink the way they were living previously and the kinds of values they had held. Although little changed initially, by the middle of the 15th century radical changes were taking place throughout Europe.

These changes were unimaginable only one hundred years before. In particular these included the Protestant Reformation. The agricultural shift from large-scale grain-farming to animal husbandry. The wage increase for urban and rural laborers. And the many other advances associated with the Renaissance. Plague outbreaks would continue long after the Black Death pandemic of the 14th century.

However but none would have the same psychological impact resulting in a complete reevaluation of the existing paradigm of received knowledge. Europe as well as other regions affected in the world based their reactions to the Black Death on traditional conventions, both whether religious and/or secular. When these religious and secular paradigms failed, new models for understanding the world had to be created [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

MEDIEVAL TRADES (OCCUPATIONS): Many trades in medieval times were essential to the daily welfare of the community. Those who had learned a skill through apprenticeship could expect to make a higher and more regular income than farmers or even soldiers. Such professionals as millers, blacksmiths, masons, bakers and weavers grouped together by trade to form guilds. The guilds sought to protect the rights of their members, guarantee fair prices, maintain industry standards and keep out the unlicensed competition.

As towns grew into cities from the 11th century onward trades diversified and medieval shopping streets began to boast all manner of skilled workers and their goods on sale, from saddlers to silversmiths and tanners to tailors. Naturally, trades and trading practices varied over time and place throughout the Middle Ages. So the examples cited hereinafter is limited to a general overview of some of the common features of trades in medieval Europe.

Many children learnt the trade of their parents by informal observation and helping out with small tasks. However there were also full apprenticeships, paid for by parents, where young people lived with a skilled worker or master and learned their craft. Very often a master who took on an apprentice also took on the role of parent, providing all their needs and moral guidance. In turn the apprentice was expected to be obedient to their master in all matters. An apprentice was not usually paid but did receive their food, lodgings and clothing.

Boys and girls typically became apprentices in their early teens. However sometimes they were as young as seven years old when they started out on the long road to learn a specific trade. There were many cases of apprentices running away. Rules were established that the master and the apprentice's father had to spend one day each looking for the missing youth. There were time limits of one year, after which a master need not take the escapee back under apprenticeship.

The length of the apprenticeship depended on the trade and the master. Of course the benefit to the master of free labor from the apprentice was a temptation to extend the training for as long as possible. However around seven years of apprenticeship seems to have been typical. A cook’s apprentice might only need two years training. At the other end of the spectrum a metalworker like a goldsmith might have to learn their trade for ten years before they could set themselves up with their own business.

An apprentice usually qualified to be a master in his own right by producing a ‘masterpiece’ which showed off his acquired skills. Earning the title of master required more than skill however, it cost money. A qualified apprentice who could not afford their own place of business was known as a journeyman. The “journey” referred to the fact that a journeyman usually traveled around and found work wherever they could. Ideally that work was with a settled master possessed of domestic and commercial premises.

From the 12th century onward, once their own business was up and running, master tradesmen became members of guilds. These organizations were managed by a core group of seasoned professionals known as guildmasters. Guilds sought to protect the working conditions of their members, ensure their products were to a high standard and outside competition was minimized. Many trades were grouped together in parts of a city so that guilds could better regulate their members.

Regular inspections ensured (at least to some degree) that: 1) goods were exactly what they were advertised as; 2) regulation measurements and weights were adhered to; 3) prices were correct and that members did not utilize unfair tactics in the competition between themselves for clients. By imposing regulations on apprenticeship, guilds could also regulate the labor supply and ensure there were not too many masters at any one time. This ensured that the prices of both labor and goods did not crash.

There were very few guilds specifically for or managed by women. Most apprentices were male as were their masters. However there was a significant minority of women involved in some trades. Widows were especially prominent in the trades if they were able to run their deceased husband’s business. There were caveats. If the widow was to run her deceased husband’s business it had to be in the absence of a close male relative, and they had to remain single. Even then there were some restrictions. For example they were not permitted to train an apprentice.

Some trades such as the poulterers (poultry and game dealers) of Paris did permit any woman with means to own businesses. In addition many trades such as silk production and veil makers were dominated by women workers. Tax assessments of the time record many different types of enterprises from lacemakers to butchers being managed by women.

Each castle or manor had its own mill to serve the needs of its surrounding estate. The mill processed grain not only from the lord’s lands, but also that of the serfs who were usually obliged to grind their grain (for a fee) at the lord’s mill. Mills could be powered by wind, water, horses or people. One essential item to set up business was a good quality millstone that did not wear smooth quickly but, unfortunately, this was a pricey commodity.

The Rhineland gained a great reputation for producing the best millstones. Such a millstone could cost 40 shillings, the equivalent of ten horses in England. A castle or manor did not need to use its mill very often (even if ground grains did not keep very long), With such a heavy investment for a millstone only used sporadically the mill was often rented out to a miller. The miller was then free to make whatever profit he could from the operation of the mill.

The miller enjoyed a high social status in the community because he was essential, had a steady income, and it was a pleasant vocation. Nonetheless the miller had to make money in order to pay for the mill’s rent. Consequently they were sometimes viewed with suspicion by other villagers who worried that they never quite got back the quantity of flour their grain had produced. As one medieval riddle went: “What is the boldest thing in the world? A miller’s shirt, for it clasps a thief by the throat daily.”

In the Middle Ages, the cheapest materials were wood and clay. However the fabrication of some items required metal, usually iron, which was much more expensive. Thus the blacksmith was as essential as the miller to any medieval community. Many agricultural tools needed iron parts, if only for their cutting edges. So blacksmiths were kept busy producing new tools and repairing old ones.

Cooking pots and horseshoes were other sought-after products produced (almost magically it seemed to many) by the blacksmith’s forge, hammer and anvil. However in contrast to our disposable-goods society, in the medieval world it was a necessity that manufactured good possessed a long life span. Thus a competent village blacksmith producing quality implements might not be kept busy enough to earn a living. And a blacksmith had high overheads in conjunction with the impressive but costly range of tools and equipment required to pursue his trade.

Consequently blacksmiths usually inherited the business and capital equipment from their fathers. Many also farmed in order to make ends meet. A blacksmith at a manor or castle was better off as he might receive charcoal made from the trees of the lord’s forest for free. He typically also benefited by the assignment of a couple of the lord's serfs. They worked his small strip of farmland while he was busy with his hammer and tongs.

Bread forming an important part of the medieval diet, especially for the lower classes. Bakers were thus another ever-present, essential merchant. But for the same reason bakers were one of the most regulated trades. At least in towns frequent regulatory ensured bakers were selling bread loaves of acceptable quality and of accurate size and weight. Bread loaves were typically stamped with an identification mark identifying the baker who had produced it. of just who had baked it.

Despite these precautions it was not uncommon for bakers to supplement the flour content of bread with something a little cheaper, like sand. Those bakers who tried to swindle their customers and were caught often found themselves with the offending bread loaf tied around their neck and chained to a pillory (a wooden framework with holes for the head and hands, in which an offender was imprisoned and exposed to public abuse). In order for fresh bread to be available in the mornings, bakers were one of the few tradesmen permitted to work at night.

The medieval butcher prepared choice cuts of pork, mutton, and beef as well as poultry and game. The butcher sold what was in the Middle Ages an expensive commodity. Butchers typically occupied the dirtiest and smelliest part of the town. Butchers were right down there with the fish mongers in the low popularity contest amongst urban shoppers.

In addition, as with the bakers, many people were suspicious of just what a butcher put in his sausages to save money. As one joke went: “A man asked the sausage butcher for a discount because he had been a faithful customer for seven years. ‘Seven years!’ exclaimed the butcher, ‘And you’re still alive!’” To keep consumer confidence high, there were additional rules imposed by the butchers' guild. These included a prohibition against the sale of meat from such animals as cats, dogs, and horses. The mixing of tallow (rendered beef or mutton fat) with lard (pork fat) was also prohibited.

Many peasant women spun thread in the home and then sold it on to a weaver, who was usually male. Some women continued beyond spinning thread and wove cloth on an upright loom. However by the High Middle Ages weaving was typically done on a larger scale by a skilled weaver using a horizontal loom. Such a loom was financially beyond the means of a peasant. England and Wales enjoyed a high reputation for their wool in medieval times while Flanders became a major centre of wool cloth production.

Wool was washed to remove grease, then dried, beaten, combed and carded. The wool was then spun and worked on the loom to make a rough cloth which was next fulled (soaked, shrunk and then usually dyed). This was accomplished sometimes using a water-powered mill, but more often imply trampled underfoot. The cloth was then sheared and brushed, perhaps many times, in order to produce a very fine, smooth cloth.

One thing everyone needed was a roof over their heads. As societies became more prosperous and towns grew in size, construction techniques improved from the 13th century onward. Many medieval inhabitants sought better and more substantial homes to live in. Prosperous peasants looked to improve on their traditional mud and timber cottages. Lords were looking to impress with manor houses that might look like the castle most of them could not afford.

Consequently there developed many specialized trades for each facet of any building’s construction. This included craftsmen such as masons, tilers, carpenters, thatchers, glassmakers and plasterers. Carpenters in particular were also utilized in the upkeep of houses and other structures such as barns, granaries, churches and bridges. At the top of the building profession were the master builder and master stone mason. Both of these craftsmen required skill in mathematics and geometry to produce their scale models and parchment plans.

These plans and models would insure that the elements of a building produced by subordinate workers would fit together properly. The master masons and builders rarely lifted a finger themselves. They value lay as good managers of a large team of skilled workers. Their managerial skills were especially critical for large projects like building a castle or church. Larger towns and cities had especially numerous and diverse tradespeople. There were tailors, drapers, dyers, saddlers, furriers, chandlers, tanners, armourers, sword makers, parchment makers, basket-weavers, goldsmiths, silversmiths.

By far the biggest industry sector encompassed all manner of food sellers. Many of these trades were often grouped together in parts of a city so that guilds could better regulate their members. The grouping of particular trade merchants in particular geographical areas of the city such as by the city gates also helped attract traffic. And of course in time particular area of a city developed a tradition for a specific trade (like Notre-Dame in Paris had for books, which it still has today).

By the later Middle Ages Medieval doctors gained their expertise at a university and enjoyed a high status. However their practical role in society was limited to diagnosis and prescription. A patient was actually treated by a surgeon and given medicine which was prepared by an apothecary. Both surgeons and apothecaries (pharmacists) were considered tradesmen because they had acquired their skills via apprenticeship. As a surgeon could be expensive, many of the poorer class took their minor physical problems to a much cheaper option; the local barber.

When not cutting hair and trimming moustaches, a barber performed minor surgeries and also pulled teeth. The poor might also seek the skills of a peddler of folk medicine who dispensed advise and lotions based on traditional and natural remedies. Despite their dubious origins, many of these traditional and natural remedies must have worked to some degree in order for them to continuously utilized throughout the Middle Ages [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

SHIPPING & RETURNS/REFUNDS: We always ship books domestically (within the USA) via USPS INSURED media mail (“book rate”). Most international orders cost an additional $13.49 to $41.99 for an insured shipment in a heavily padded mailer. There is also a discount program which can cut postage costs by 50% to 75% if you’re buying about half-a-dozen books or more (5 kilos+). Our postage charges are as reasonable as USPS rates allow. ADDITIONAL PURCHASES do receive a VERY LARGE discount, typically about $5 per book (for each additional book after the first) so as to reward you for the economies of combined shipping/insurance costs.

Your purchase will ordinarily be shipped within 48 hours of payment. We package as well as anyone in the business, with lots of protective padding and containers. All of our shipments are fully insured against loss, and our shipping rates include the cost of this coverage (through stamps.com, Shipsaver.com, the USPS, UPS, or Fed-Ex). International tracking is provided free by the USPS for certain countries, other countries are at additional cost. We do offer U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail, Registered Mail, and Express Mail for both international and domestic shipments, as well United Parcel Service (UPS) and Federal Express (Fed-Ex). Please ask for a rate quotation. We will accept whatever payment method you are most comfortable with.

If upon receipt of the item you are disappointed for any reason whatever, I offer a no questions asked 30-day return policy. Send it back, I will give you a complete refund of the purchase price; 1) less our original shipping/insurance costs, 2) less non-refundable PayPal/eBay payment processing fees. Please note that PayPal does NOT refund fees. Even if you “accidentally” purchase something and then cancel the purchase before it is shipped, PayPal will not refund their fees. So all refunds for any reason, without exception, do not include PayPal/eBay payment processing fees (typically between 3% and 5%) and shipping/insurance costs (if any). If you’re unhappy with PayPal and eBay’s “no fee refund” policy, and we are EXTREMELY unhappy, please voice your displeasure by contacting PayPal and/or eBay. We have no ability to influence, modify or waive PayPal or eBay policies.

ABOUT US: Prior to our retirement we used to travel to Europe and Central Asia several times a year. Most of the items we offer came from acquisitions we made in Eastern Europe, India, and from the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean/Near East) during these years from various institutions and dealers. Much of what we generate on Etsy, Amazon and Ebay goes to support The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, as well as some other worthy institutions in Europe and Asia connected with Anthropology and Archaeology. Though we have a collection of ancient coins numbering in the tens of thousands, our primary interests are ancient jewelry and gemstones. Prior to our retirement we traveled to Russia every year seeking antique gemstones and jewelry from one of the globe’s most prolific gemstone producing and cutting centers, the area between Chelyabinsk and Yekaterinburg, Russia. From all corners of Siberia, as well as from India, Ceylon, Burma and Siam, gemstones have for centuries gone to Yekaterinburg where they have been cut and incorporated into the fabulous jewelry for which the Czars and the royal families of Europe were famous for.

My wife grew up and received a university education in the Southern Urals of Russia, just a few hours away from the mountains of Siberia, where alexandrite, diamond, emerald, sapphire, chrysoberyl, topaz, demantoid garnet, and many other rare and precious gemstones are produced. Though perhaps difficult to find in the USA, antique gemstones are commonly unmounted from old, broken settings – the gold reused – the gemstones recut and reset. Before these gorgeous antique gemstones are recut, we try to acquire the best of them in their original, antique, hand-finished state – most of them centuries old. We believe that the work created by these long-gone master artisans is worth protecting and preserving rather than destroying this heritage of antique gemstones by recutting the original work out of existence. That by preserving their work, in a sense, we are preserving their lives and the legacy they left for modern times. Far better to appreciate their craft than to destroy it with modern cutting.

Not everyone agrees – fully 95% or more of the antique gemstones which come into these marketplaces are recut, and the heritage of the past lost. But if you agree with us that the past is worth protecting, and that past lives and the produce of those lives still matters today, consider buying an antique, hand cut, natural gemstone rather than one of the mass-produced machine cut (often synthetic or “lab produced”) gemstones which dominate the market today. We can set most any antique gemstone you purchase from us in your choice of styles and metals ranging from rings to pendants to earrings and bracelets; in sterling silver, 14kt solid gold, and 14kt gold fill. When you purchase from us, you can count on quick shipping and careful, secure packaging. We would be happy to provide you with a certificate/guarantee of authenticity for any item you purchase from us. There is a $3 fee for mailing under separate cover. I will always respond to every inquiry whether via email or eBay message, so please feel free to write.