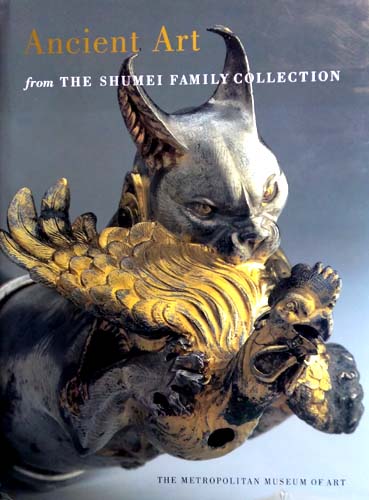

"Ancient Art from the Shumei Family Collection" by Dorothea Arnold, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with dustjacket. Publisher: New York Metropolitan Museum of Art (1996). Pages: 210. Size: 12½ x 9¼ x 1¼ inches; 3¾ pounds. Summary: The magnificent collection of ancient art celebrated in this volume is a selection of the holdings of the Shumei Family, a religious organization based in Japan. The emphasis, in the works included here, is on antiquities that originated in different areas of the ancient world—namely, the Mediterranean, the Near East, and China. Although the objects are eclectic, and range from powerful to jewel-like in their delicacy, the quality of the works of art in the Shumei Family Collection shines through in every detail. Whether we focus on the silver and gold cult figure of a deity from thirteenth-century-B.C. Egypt; Achaemenid silver vessels from fifth-century-B.C. Iran; or gold, bronze, and iron garment hooks, inset with gems and semi-precious stones, from third-century-B.C. China, their exquisite beauty and refinement never fail to dazzle the eye.

Before the Shumei Family's Miho Museum—designed by world-renowned architect I. M. Pei, and currently under construction in Shigaraki, a suburb of Kyoto—is inaugurated in the fall of 1997, and the works of art discussed here are permanently installed in their new home, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art have welcomed the opportunity to introduce highlights of the collection to their respective publics. The credo of the founder of the Shinji Shumeikai centers around the belief that beautiful objects elevate the spirit and, therefore, that they were created to be shared. In keeping with this philosophy, both reader and museum visitor can take delight in the collection, savoring the treasures firsthand on exhibition and, concurrently, in the lavish color illustrations that grace these pages.

The cogent texts represent the collaboration of a broad spectrum of curators, art historians, and conservators; more than twenty scholars examine the objects in detail and provide illuminating insights for the reader. An Appendix includes technical examinations of a number of the works as well as descriptions of their materials and methods of manufacture. A Selected Bibliography and an Index follow.

The cogent texts represent the collaboration of a broad spectrum of curators, art historians, and conservators; more than twenty scholars examine the objects in detail and provide illuminating insights for the reader. An Appendix includes technical examinations of a number of the works as well as descriptions of their materials and methods of manufacture. A Selected Bibliography and an Index follow.

CONDITION: NEW. New hardcover w/dustjacket. New York Metropolitan Museum of Art (1996) 210 pages. Unblemished except for very faint (virtually indiscernable) shelfwear to dustjacket. Pages are pristine; clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Condition is entirely consistent with new stock from a bookstore environment wherein new books might show minor signs of shelfwear, consequence of simply being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #9020a.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Dorothea Arnold is curator emerita, the Department of Egyptian Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

REVIEW: Shumei believes in the pursuit of beauty through art, appreciation of nature and "natural agriculture", a method of food cultivation. They also practice johrei, a type of spiritual healing. Adherents of Shumei believe that, in building architectural masterpieces in remote locations, they are restoring the Earth's balance. Shinji Shūmeikai was founded by Mihoko Koyama in 1970. She founded the organization to spread the teachings of Mokichi Okada. The head organization is currently based near Shigaraki, Shiga, Japan.

REVIEW: Shumei believes in the pursuit of beauty through art, appreciation of nature and "natural agriculture", a method of food cultivation. They also practice johrei, a type of spiritual healing. Adherents of Shumei believe that, in building architectural masterpieces in remote locations, they are restoring the Earth's balance. Shinji Shūmeikai was founded by Mihoko Koyama in 1970. She founded the organization to spread the teachings of Mokichi Okada. The head organization is currently based near Shigaraki, Shiga, Japan.

The Miho Museum was commissioned by Mihoko Koyama, who was an adherent of Okada. The architect I. M. Pei had earlier designed the bell tower at Misono, the international headquarters and spiritual center of the Shumei organisation. Mihoko Koyama and her daughter, Hiroko Koyama, again commissioned Pei to design the Miho Museum. The bell tower can be seen from the windows of the museum. Founders Hall was designed by Japanese-American architect Minoru Yamasaki.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Foreword by Hiroko Koyama.

Directors' Foreword by Philippe de Montebello and Graham W.J.Beal.

Contributors to the Catalogue.

Egyptian Art.

Ancient Near Eastern Art.

Roman Art.

Asian Art.

Islamic Art.

Appendix.

Selected Bibliography.

Index.

Photograph Credits.

REVIEW: The Miho Museum is located southeast of Kyoto, Japan, near the town of Shigaraki, in Shiga Prefecture. The museum was the dream of Mihoko Koyama (after whom it is named), founder of the religious organization Shinji Shumeika, which is now said to have some 300,000 members worldwide. Furthermore, in the 1990s Koyama commissioned the museum to be built close to the Shumei temple in the Shiga mountains.

REVIEW: The Miho Museum is located southeast of Kyoto, Japan, near the town of Shigaraki, in Shiga Prefecture. The museum was the dream of Mihoko Koyama (after whom it is named), founder of the religious organization Shinji Shumeika, which is now said to have some 300,000 members worldwide. Furthermore, in the 1990s Koyama commissioned the museum to be built close to the Shumei temple in the Shiga mountains.

The Miho Museum houses Mihoko Koyama's private collection of Asian and Western antiques bought on the world market by the Shumei organisation in the years before the museum was opened in 1997. While Koyama began acquiring stoneware tea ceremony vessels as early as the 1950s, the bulk of the museum's acquisitions were made in the 1990s. There are over two thousand pieces in the permanent collection, of which approximately 250 are displayed at any one time.

Among the objects in the collection are more than 1,200 objects that appear to have been produced in Achaemenid Central Asia. Some scholars have claimed these objects are part of the Oxus Treasure, lost shortly after its discovery in 1877 and rediscovered in Afghanistan in 1993. The presence of a unique findspot for both the Miho acquisitions and the British Museum's material, however, has been challenged.

Many of the items in the collection were acquired in collaboration with the art dealer Noriyoshi Horiuchi over the course of just six years, and some have little or no known provenance. In 2001 the museum acknowledged that a sixth-century statue of a Boddhisatva in its collection was the same sculpture which been stolen from a public garden in Shandong province, China in 1994.

Highlights of the collections have been featured in traveling exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1996, as well as the Kunshistorisches Museum Wien in 1999.

Mihoko Koyama and her daughter, Hiroko Koyama, commissioned the architect I. M. Pei to design the Miho Museum. I. M. Pei's design, which he came to call Shangri-La, is executed in a hilly and forested landscape. Approximately three-quarters of the 17,400 square meter building is situated underground, carved out of a rocky mountaintop. The roof is a large glass and steel construction, while the exterior and interior walls and floor are made of a warm beige-colored limestone from France – the same material used by Pei in the reception hall of the Louvre. The structural engineer for this project was Leslie E. Robertson Associates.

Pei continued to make changes to the design of the galleries during construction as new pieces were acquired for the collection. Pei had earlier designed the bell tower at Misono, the international headquarters and spiritual center of the Shumei organization. The bell tower can be seen from the windows of the museum.

Pei continued to make changes to the design of the galleries during construction as new pieces were acquired for the collection. Pei had earlier designed the bell tower at Misono, the international headquarters and spiritual center of the Shumei organization. The bell tower can be seen from the windows of the museum.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: The Shumei Family, a religious organization based in Japan, believes that "Unless you make others happy, you can never be happy yourself." To this end they have collected art for the past 40 years. On the advice of I.M. Pei, the architect hired to design a museum for their holdings, they expanded their collection from primarily Japanese works to other areas of ancient art. This catalog presents the non-Japanese part of the collection, which is on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art this year. With only two Egyptian and two Roman pieces, the bulk of the small, elegant collection is from central and eastern Asia. However, as Spencer Tracy once said of Katharine Hepburn, "What's there is cherce." The silver and gold Egyptian cult statue is unique, for example, and every item was very carefully selected to fit the collection in a manner reminiscent of ikebana flower arrangement. Technically, the color plates are sharp and beautiful, and the scholarship is impressive. Recommended for collections specializing in connoisseurship, Japanese studies, or ancient Asia. [Library Journal].

REVIEW: Published in conjunction with an exhibition held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art during 1996 and scheduled to travel to Los Angeles during 1997. The works are selected from the holdings of the Shumei Family, a religious organization based in Japan which holds to the belief that beautiful objects elevate the spirit and, therefore, that they were created to be shared (the group is currently constructing a new museum in Japan to house the collection). The works included here antiquities from the Mediterranean, the Near East, and China are beautifully presented in color photos, with text by a broad spectrum of curators, art historians, and conservators. [Book News].

REVIEW: A Japanese Vision of the Ancient World. In 1991, after collecting objects for the Japanese tea ceremony for 40 years, Mihoko Koyama switched to buying ancient and medieval art for the world-class museum she envisioned building on a mountaintop in Japan. Frail and in a wheelchair, Mrs. Koyama, an heiress to a textile fortune, moved quietly but with tornado force through the ancient art market. Over the next six years she collected 300 works produced in China, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, Greece, Rome and Egypt, buying several times a year at the galleries of prominent dealers in Europe and the United States. Many were masterpieces, like an Assyrian limestone relief, depicting a winged deity and a royal attendant, that she bought from a dealer in 1994 after it was auctioned at Christie's in London for $11.9 million, a record for ancient art.

The antiquities and the tea ceremony artifacts are exhibited in the Miho Museum, a stone, steel, glass and concrete structure named after its creator and designed by I. M. Pei, in the town of Shigaraki, 20 miles east of Kyoto. (The cost of the land, art and building was about three-quarters of a billion dollars.) The site is near the headquarters of Shinji Shumeikai, or Shumei Family, the religious group that Mrs. Koyama, now 88, founded in 1970. Its 300,000 members believe that contemplating beauty in art and nature brings spiritual fulfillment.

The antiquities and the tea ceremony artifacts are exhibited in the Miho Museum, a stone, steel, glass and concrete structure named after its creator and designed by I. M. Pei, in the town of Shigaraki, 20 miles east of Kyoto. (The cost of the land, art and building was about three-quarters of a billion dollars.) The site is near the headquarters of Shinji Shumeikai, or Shumei Family, the religious group that Mrs. Koyama, now 88, founded in 1970. Its 300,000 members believe that contemplating beauty in art and nature brings spiritual fulfillment.

The change in Mrs. Koyama's art collecting came after a conversation with Mr. Pei. "I'm afraid I'm partly to blame for Mrs. Koyama's shift in collecting," he said. "I looked at the pieces she wanted in the museum and 90 percent were Japanese tea ceremony objects. Since many museums in Japan have such collections, I wondered why people would come a long way to see this museum. Mr. Pei said that Mrs. Koyama had seemed to understand and asked him for suggestions. "Why not turn your eyes to the West," he said, "not to the West of Van Gogh, but to the West which was a source for ancient Japanese art. Look West to Buddhism, to the Silk route, to ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt."

Mrs. Koyama enlisted the help of Noriyoshi Horiuchi, a Tokyo dealer in ancient art who transformed her vision into a reality. He introduced Mrs. Koyama and her daughter, Hiroko, to dealers like Giuseppe Eskenazi and Robin Symes in London and James J. Lally and Edward Merrin in New York. Mr. Horiuchi preselected the works for Mrs. Koyama: Chinese bronzes, Sassanian silver vessels, Egyptian wood carvings, Roman mosaics and Persian lusterware. While confident in her choices, Mrs. Koyama, who speaks little English, relied on experts to confirm her judgment. "She didn't say much, a word or two, like 'beautiful,' 'wonderful,' 'excellent,'" Mr. Horiuchi said. "She didn't ask the history, the background or the price of the objects."

When she admired a piece, said Mr. Eskenazi, the dealer, "she expressed her great excitement by her wonderful benign smile." It was a smile he was to see many times as Mrs. Koyama returned frequently to his gallery to buy at least 27 pieces, including Chinese stone sculpture, inlaid bronzes and a Tang tomb figure of a pottery court lady with a haunting smile.

Choosing the objects was easy for Mrs. Koyama and her team. What was difficult was authenticating the works. The field of antiquities is plagued by forgeries and illegally excavated objects. But Mr. Horiuchi was well aware of these problems. "We bought only from major dealers," he said. "And we invited museum curators, scholars, collectors, restorers and dealers to look at the collection and urged everyone to tell us of any problems they saw."

He also had all of the objects analyzed in museum laboratories, most of them by Pieter Meyers, the head of the Conservation Center of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Of the 300 pieces studied, 8 were not authenticated and were removed from the collection. In their travels, Mrs. Koyama and her daughter met with directors, curators and conservators from New York, Los Angeles, London, Paris, Berlin and St. Petersburg to arrange future loans of art works from the collection.

He also had all of the objects analyzed in museum laboratories, most of them by Pieter Meyers, the head of the Conservation Center of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Of the 300 pieces studied, 8 were not authenticated and were removed from the collection. In their travels, Mrs. Koyama and her daughter met with directors, curators and conservators from New York, Los Angeles, London, Paris, Berlin and St. Petersburg to arrange future loans of art works from the collection.

In 1996, an exhibition of 80 works, "Ancient Art from the Shumei Family Collection," opened at the Metropolitan Museum and later moved to the Los Angeles County Museum. Last November, the movers and shakers in ancient art gathered for the opening of the Miho. "Collecting art is an ancient tradition in Japan," Mr. Horiuchi said. "As early as the eighth century, the Japanese received gifts of Persian art from Chinese emperors and continued to collect. Then, and once again now, the Japanese are eager to import art and knowledge from China and Europe." [New York Times].

REVIEW: As a miscellany of arresting objects from the distant past, "Ancient Art From the Shumei Family Collection" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is in a very high class. As a reasoned survey of a particular point of view, on the other hand, it makes very little sense. What are we to make of an anthology that has exactly two items from the whole of ancient Egypt, three from ancient Rome and no fewer than eight examples of the memorably luxurious "garment hooks" (or hat, coat and umbrella stands) that were made in China more than 2,000 years ago? Admittedly, each of these garment hooks is quite unlike any of the others. Even so, this seems a classic case of imbalance.

Be that as it may, one of the two Egyptian objects is presented as the flagship of the show. And very arresting it is, too. A full-length seated figure, half man and half bird, from the 13th century B.C., it is made of solid-cast silver that was formerly almost entirely overlaid with sheet gold. The hair of the wig is overlaid with lapis lazuli, and the deep-set eyes are of rock crystal. Though only just over 16 inches high, it radiates authority. The human part of the sculpture is enviably lean, but when it comes to holding our attention it politely gives way to the really rather terrifying falcon head. Above all, the rock crystal gaze stares us down, all the more so, perhaps, because the left eye was restored in 1970, when the piece was being looked after in a museum in Stuttgart, Germany.

The collection is the work of a Japanese religious organization called the Shinji Shumeikai, or the Shumei Family. As a collection, it appears to have no strictly devotional element. On the contrary, secular objects of art are its specialty. Of its overall purposes, all that we learn from the catalogue is that the collection was initiated around 40 years ago, on the belief that "unless you can make others happy, you will never be happy yourself." From this, few will dissent. "Works of art" -- here I quote from the same source -- "are not to be monopolized by the few, but shown for the delight of the many, that their spirits may be elevated." To give that elevation the best possible start, I. M. Pei was asked to design a museum in the mountains near Kyoto to house the collection. The museum, which is to open in the fall of 1997, will include the Japanese objects in the collection, none of which are on view at the Met.

Meanwhile, very little is vouchsafed by any of the 22 contributors to the catalogue as to where, when and how the works were acquired. But there is at least one masterwork that has been known since the early 17th century: an enormous carpet (19 feet 6 inches by 10 feet 6 inches) that was woven in Iran in the late 16th or early 17th century. Known as the Sanguszko carpet, after one of its former owners, it is in amazingly good condition. And it needs to be, given the brilliance of its color and the multiplicity of heterogeneous incident that spills this way and that over every square inch of available space.

This carpet is a bookman's paradise. Literary echoes are everywhere, as are elements lifted from Islamic book design. But you don't need to be a scholar to decipher the tumultuous activities in which men, women and angels mingle with dragon, phoenix and peacock, to name just a few of the storytellers' resources. They don't just sit around, either. The catalogue tells of scenes in which "dragons intertwine, while peacocks pair off and single animals and birds romp." It is the charm of this lopsided but consistently engrossing show that we never know what will come next. A recurrent ingredient is the truly monumental piece of jewelry, a specialty of the Achaemenid period in Iran. "If you have it, flaunt it" was the motto behind many of these pieces.

A prize instance is the "bracelet with seated-duck terminals" from the sixth to fourth century B.C. The massive gold tubular body of the bracelet is impressive enough in itself. But when the two seated ducks were added, the piece took on another dimension.The ducks are minutely simulated in gold, with lapis lazuli, turquoise, onyx, rock crystal and blue and white vitreous paste. Here and there, time has brought substantial damage. But the flamboyance of the overall gesture is something to marvel at.

In the Chinese section, which in terms of numbers amounts to half the exhibition, there are noble forms that have nothing to do with personal adornment. From the western Han period, for instance, or second to first century B.C., there are two weights in the form of coiled tigers. These were not objects of delectation, but indispensable adjuncts to the idea of purity and simplicity in household design. Without those tigers, mats would curl up at the corners or slide around the room.

In the Chinese section, which in terms of numbers amounts to half the exhibition, there are noble forms that have nothing to do with personal adornment. From the western Han period, for instance, or second to first century B.C., there are two weights in the form of coiled tigers. These were not objects of delectation, but indispensable adjuncts to the idea of purity and simplicity in household design. Without those tigers, mats would curl up at the corners or slide around the room.

Among other pieces of gratuitous but worthwhile information, the show tells us about the changing status of the chariot in China during the western Han period. To be precise, the chariot lost much of its military importance and became simply something to boast about. And sure enough, that loss of soldierly status is reflected in the group of gilt bronze chariot fittings. What began as a tiger with its mouth wide open and jaws at the ready turned in time into a tiger that looks sedated and had its mouth shut tight. If there is such a thing as a companionable tiger, here he is.

But it would be unfair to take leave of this wonderfully peculiar show on a note of sedation. Violence, implied or immediate, is always round the corner, nowhere more so than in the rhyton, or drinking horn, made by a master silversmith in Iran or Central Asia in the first century B.C. This is a piece that, when filled, would quench even a raging thirst. But its particular magic comes from the way in which the silversmith modulates from the plain curved surface to a minutely modeled terminal in which a caracal, or desert lynx, has its way with an unfortunate fowl.

The eyes, the furry ears, the claws and the concentrated onslaught of the cat are wonderfully rendered. So is the plight of the fowl, with life already almost extinct and its feathers, comb and wattles in terminal disarray. "Ancient Art From the Shumei Family Collection" remains at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fifth Avenue at 82d Street, through Sept. 1. The show then travels to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Nov. 17 to Feb. 9, 1997). [New York Times].

REVIEW: There's a significant piece of cultural news embedded in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art's new exhibition "Ritual and Splendor: Ancient Treasures From the Shumei Family Collection." It's a breathtaking, rare example of a holding selected with superbly refined taste, but it's even more. The 155 works on view encompass not only China and West Asia but Bactria, Greece, Rome and Islamic Iran. It's a virtually unprecedented instance of a Japanese compendium that includes master art from primary civilizations outside the Far East.

Japanese museums have been notably tardy in acquiring such art so this collection--assembled in recent years--marks a symbolic new opening to fundamental aspects of Western history and culture. A smaller selection of these works was seen earlier this year at New York's Metropolitan Museum. Its catalog serves the present presentation. After closing here the entire collection of some thousand objects will go on view late in 1997 in their permanent home, the new Miho Museum not far from Kyoto. The 83,000-square-foot structure was designed by the renowned architect I.M. Pei. The Shumei Family, not just incidentally, is not an ordinary domestic grouping. The name is a sobriquet for Shinji Shumeikai, which designates itself "a worldwide spiritual organization dedicated to the pursuit of truth, virtue and beauty."

Japanese museums have been notably tardy in acquiring such art so this collection--assembled in recent years--marks a symbolic new opening to fundamental aspects of Western history and culture. A smaller selection of these works was seen earlier this year at New York's Metropolitan Museum. Its catalog serves the present presentation. After closing here the entire collection of some thousand objects will go on view late in 1997 in their permanent home, the new Miho Museum not far from Kyoto. The 83,000-square-foot structure was designed by the renowned architect I.M. Pei. The Shumei Family, not just incidentally, is not an ordinary domestic grouping. The name is a sobriquet for Shinji Shumeikai, which designates itself "a worldwide spiritual organization dedicated to the pursuit of truth, virtue and beauty."

All this provides Los Angeles the opportunity to see a treasures extravaganza realized by applying Japanese culture's traditionally exquisite, understated aesthetic sensibility to the West. As an experience it's extraordinarily piquant and gratifying.How often in the West, for example, does one encounter an exhibition where the first piece is an 8-inch-tall 7th century Greek bronze of a "Griffin Protome" that causes us to realize this tiny thing is worthy of acting as the curtain raiser for a blockbuster show?

Japanese art reveres refinement. Refinement, defined in the most material terms, occurs when an object is worked with painstaking care over a long period to get it exactly right. The natural result of such action is that the object gets smaller. The exhibition demonstrates repeatedly that smaller can be better. The Egyptian section opens with two 12th dynasty painted wood statues of a walking man. Stylistically they are almost identical except one is life-size, the other about 14 inches tall. The compacted form of the small one makes it more memorable. Its delicacy appeals to our sense of parental protectiveness. Its utter lack of intimidation is comforting.

Speaking of intimidation, pieces in sections on Bactria and early Iran are clearly related to one of history's scariest arts, that of ancient Assyria. Its monumental reliefs of winged bulls and warriors in the Louvre make Big Brother seem downright cuddly. Here the same motifs are used on golden goblets, delicate as foil. They lose nothing in expressive clout, except a certain pomposity. Most ancient art grew from a mind-set radically different from that of today's just-a-regular-guy-who-wants-to-get-along demeanor. Much ancient art intended to openly demonstrate superiority in physical strength, authority and wealth.

A couple of Iranian silver drinking horns end in miniature sculpted images, one of a snarling lynx, the other a caracal cat attacking a fowl. The animals are pointedly depicted as symbols of ferociously ruthless, raw power. In addition to being more up front about man's animal character, ancient art had absolutely no inclination to make silly distinctions between decorative, fine and applied arts. The Japanese have wisely followed this kind of aesthetic openness and applied it here with brilliant result. Virtually every piece, such as a particularly splendid Chinese wine vessel from the Shang Dynasty or a stunning big Iranian carpet, is simultaneously a ritual object-of-use and a work of high art.

The selection also demonstrates an early multiethnic interpenetration of these old civilizations through trade along the silk route. Throughout one runs across, say, an Iranian silver vase whose nude dancing female figures recall Indian art or an Islamic ceramic whose painting style appears Japanese. For all this, the experience of "Ritual and Splendor" has a pleasant aura of clarity and simplicity. This is due, no doubt, to a combination of the selected objects and their deft installation by designer Bernard Kester.

The impression is benignly misleading. The exhibition was some six years in the making and required the collaboration of LACMA's chief of conservation, Pieter Meyers, and three curators, Nancy Thomas, J. Keith Wilson and Linda Komaroff, among a small battalion of assistants. The larger lesson here is that anything can be art, and the only way to sort out what is is along the currently unfashionable lines of intrinsic quality.

REVIEW: A handsome publication, with fine color plates of superb works of art. [Choice Reviews Online].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: A stunning visual feast of ancient art. Really unique, exquisite artifacts, not your usual museum fare. The photography is remarkable.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

A SAMPLING OF ANCIENT ART:

Etruscan Art: The Etruscans flourished in central Italy between the 8th and 3rd century BC. Their art is renowned for its vitality and often vivid coloring. Wall paintings were especially vibrant and frequently capture scenes of Etruscans enjoying themselves at parties and banquets. Terracotta additions to buildings were another Etruscan specialty. They were also renowned for their carved bronze mirrors and fine figure sculpture in bronze and terracotta. Minor arts are perhaps best represented by intricate gold jewelry pieces. They were also talented potters. Their distinctive black pottery known as bucchero was crafted into shapes like the kantharos cup which would inspire Greek potters.

The identification of what exactly is Etruscan art is made more complicated by the fact that Etruria was never a single unified state. This is a difficult enough question for any culture. But the Etruscans were a collection of independent city-states who formed both alliances and rivalries with one another over time. Although culturally very similar these cities nevertheless produced artworks according to their own particular tastes and proclivities. Another difficulty is presented by the influences consequence of the Etruscans not living in isolation from other Mediterranean cultures.

Ideas and art objects from Greece, Phoenicia, and the Middle East reached Etruria via the long-established trade networks of the ancient Mediterranean. Greek artists also settled in Etruria from the 7th century BC onwards. Many “Etruscan” works of art are signed by artists with Greek names. Geography played a role too. Coastal cities like Cerveteri had much greater access to sea trade. As a result such cities were much more cosmopolitan in population and artistic outlook than were more inland cities like Chiusi. The Etruscans greatly appreciated foreign art and readily adopted ideas and influences in the art forms prevalent in other cultures.

Ideas and art objects from Greece, Phoenicia, and the Middle East reached Etruria via the long-established trade networks of the ancient Mediterranean. Greek artists also settled in Etruria from the 7th century BC onwards. Many “Etruscan” works of art are signed by artists with Greek names. Geography played a role too. Coastal cities like Cerveteri had much greater access to sea trade. As a result such cities were much more cosmopolitan in population and artistic outlook than were more inland cities like Chiusi. The Etruscans greatly appreciated foreign art and readily adopted ideas and influences in the art forms prevalent in other cultures.

Then as now Greek art was highly esteemed by the Etruscans, especially work from Athens. However it is an error to imagine that Etruscan art was merely a poor copy of Greek art. It is true that Etruscan and Greek artists in Etruria may have sometimes lacked the finer techniques of vase-painting and sculpture in stone that their contemporaries in Greece, Ionia, and Magna Graecia possessed. Nonetheless at the same time other art forms such as gem-cutting, gold work, and terracotta sculpture demonstrate that the Etruscans had a greater technical knowledge in these areas. It is true that the Etruscans often tolerated works of a lower quality than would have been accepted in the Greek world. However that does not mean that the Etruscans were not capable of producing art which was the equal of that produced elsewhere.

That the Etruscans greatly appreciated foreign art is evidenced by the fact that Etruscan tombs are full of imported pieces. Etruscans also readily adopted ideas and forms prevalent in the art of other cultures. However they also added their own twists to conventions. For example the Etruscans produced nude statues of female deities before the Greeks did. They also uniquely blended Eastern motifs and subjects with those from the Greek world. This was especially true with respects to mythological motifs and creatures never present in Etruria, such as lions. Etruria’s homegrown ideas can be traced back to the indigenous Villanovan culture of approximately 1000 to 750 BC. The Villanovan culture was the precursor of Etruscan culture proper.

This perpetual synthesis of ideas is perhaps best seen in funerary sculpture. When one inspects each figure closely Terracotta coffin lids with a reclining couple in the round they may resemble Archaic Greek models. However the physical attitude of the couple when seen as a pair and the affection between them which the artist has captured are entirely Etruscan. Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Etruscans is their beautifully painted tombs found in many sites like Tarquinia, Cerveteri, Chiusi, and Vulci. The paintings depict lively and colorful scenes from Etruscan mythology and daily life.

The depictions of daily life include in particular especially banquets, hunting, and sports. They typically also included heraldic figures, architectural features, and sometimes even the tomb's occupant themselves. Portions of the wall were often divided for specific types of decoration. Typically there was a dado at the bottom, a large central space for scenes, and a top cornice or entablature. The triangular space resulting was also reserved for painted scenes, reaching the ceiling like the pediment of a classical temple.

The depictions of daily life include in particular especially banquets, hunting, and sports. They typically also included heraldic figures, architectural features, and sometimes even the tomb's occupant themselves. Portions of the wall were often divided for specific types of decoration. Typically there was a dado at the bottom, a large central space for scenes, and a top cornice or entablature. The triangular space resulting was also reserved for painted scenes, reaching the ceiling like the pediment of a classical temple.

The colors used by Etruscan artists were made from paints of organic materials. There is very little use of shading until influence from Greek artists via Magna Graecia. These used their new chiaroscuro method with its strong contrasts of light and dark in the 4th century BC. At Tarquinia the paintings are applied to a thin base layer of plaster wash. The artists first drew outlines using chalk or charcoal. In contrast many of the wall paintings at Cerveteri and Veii were applied directly to the stone walls without a plaster underlayment. Only 2% of tombs were painted. They are a supreme example of conspicuous consumption by the Etruscan elite.

The late 4th century BC “Francois Tomb” at Vulci is an outstanding example of the art form. It contains a duel from Theban myth, a scene from the Iliad, and a battle scene between the city and local rivals. It even includes some warriors with Roman names. Another fine example is the misleadingly named Tomb of the Lionesses at Tarquinia. This tomb was built somewhere between 530 and 520 BC. It actually has two painted panthers. There is also a large drinking party scene. It is quite interesting as well for its unusual checkered pattern ceiling. The Tomb of the Monkey is also at Tarquinia and was constructed somewhere between 480 and 470 BC. The Tomb of the Monkey is noteworthy for its ceiling. The ceiling features an interesting single painted coffer which has four mythological sirens supporting a rosette with a four-leafed plant. The motif would reappear in later Roman and early Christian architecture but with angels instead of sirens.

Etruria was fortunate to have abundant metal resources, particularly copper, iron, lead, and silver. The early Etruscans put these to good use. Bronze was used to manufacture a wide range of goods. But the Etruscans are particularly remembered in history for their sculpture. Bronze was hammered, cut, and cast using moulds or the lost-wax technique. It was also embossed, engraved, and riveted in a full range of techniques. Many Etruscan towns set up workshops specializing in the production of bronze works. To give an idea of the scale of production, the Romans were said to have looted more than 2,000 bronze statues when they attacked Volsinii (modern Orvieto) in 264 BC. The Romans melted down the art work to produce coinage.

Often with a small stone base bronze figurines were a common form of votive offering at sanctuaries and other sacred sites. Some were originally covered in gold leaf, as with those found at the Fonte Veneziana of Arretium. Most figurines are women in long chiton robes, naked males like the Greek kouroi, armed warriors, and naked youths. Sometimes gods were presented, especially Hercules. A common pose of votive figurines is to have one arm raised, perhaps in appeal, and holding an object. The object being held was most commonly a pomegranate, flowers, or a circular item of food. The food object was most likely a cake or cheese.

Often with a small stone base bronze figurines were a common form of votive offering at sanctuaries and other sacred sites. Some were originally covered in gold leaf, as with those found at the Fonte Veneziana of Arretium. Most figurines are women in long chiton robes, naked males like the Greek kouroi, armed warriors, and naked youths. Sometimes gods were presented, especially Hercules. A common pose of votive figurines is to have one arm raised, perhaps in appeal, and holding an object. The object being held was most commonly a pomegranate, flowers, or a circular item of food. The food object was most likely a cake or cheese.

Fine examples of smaller bronze works include a 6th century BC figurine of a man making a votive offering. This came from the 'Tomb of the Bronze Statuette of the Offering Bearer' at Populonia. Volterra was noted for its production of distinctive bronze figurines which were of extremely tall and slim human figures with tiny heads. They are perhaps a relic of much earlier figures cut from sheet bronze or carved from wood. However the are curiously reminiscent of modern art sculpture. Celebrated larger works include the Chimera of Arezzo. This fire-breathing monster from Greek mythology dates to the 5th or 4th century BC.

It was probably part of a larger composition of pieces. Typically it would have been in the company of the hero Bellerophon, who killed the monster. Bellerophon in turn would have been accompanied by his winged horse Pegasus. There is an inscription on one leg which reads tinscvil or 'gift to Tin'. This indicates that it was a votive offering to the god Tin (aka Tinia), head of the Etruscan pantheon. It is currently on display in the Archaeological Museum of Florence. Other famous works include the “Mars of Todi”. This is a very striking near life-size youth wearing a cuirass and who once held a lance. In the other hand he was probably pouring a libation. It is now in the Vatican Museums in Rome.

Another famous sculpture is that of “The Minerva of Arezzo”. It is a representation of the Etruscan Goddess “Menerva”. Menerva was the equivalent of the Greek goddess Athena and Roman deity Minerva. Finally there is the striking figure “Portrait of a Bearded Man”. It is often known as “Brutus” after the first consul of Rome, but there is no evidence one way or another that it was indeed of Brutus. Most art historians agree that on stylistic grounds it is an Etruscan work of around 300 BC, centuries before the time of Brutus. It is now on display in the Capitoline Museums of Rome.

The Etruscans were much criticized by their conquerors the Romans for being rather too effeminate and party-loving. The high number of bronze mirrors found in their tombs and elsewhere only fuelled this reputation as being the ancient Mediterranean's greatest narcissists. The mirrors were known to the Etruscans as “malena” or “malstria. They were first produced in quantity from the end of the 6th century BC right through to the end of Etruscan culture in the 2nd century BC. The mirrors were of course an object of practical daily use. However with their finely carved backs they were also a status symbol for aristocratic Etruscan women. They were even commonly given as part of a bride's dowry.

The Etruscans were much criticized by their conquerors the Romans for being rather too effeminate and party-loving. The high number of bronze mirrors found in their tombs and elsewhere only fuelled this reputation as being the ancient Mediterranean's greatest narcissists. The mirrors were known to the Etruscans as “malena” or “malstria. They were first produced in quantity from the end of the 6th century BC right through to the end of Etruscan culture in the 2nd century BC. The mirrors were of course an object of practical daily use. However with their finely carved backs they were also a status symbol for aristocratic Etruscan women. They were even commonly given as part of a bride's dowry.

The mirrors were designed to be held in the hand using a single handle. The reflective side of mirrors was made by highly polishing or silvering the surface. Some mirrors from the 4th century BC onwards were protected by a concave cover attached by a single hinge. The inside of the lid was often polished to reflect extra light onto the face of the user. The outside surface of the lid carried cut-out reliefs filled with a lead backing. Of the bronze mirrors produced about half were without decoration to the flat reverse side. However for the other half the flat reverse sides were an ideal canvas for engraved decoration, inscription, or even carved shallow relief. Some handles were painted or had carved relief scenes as well.

The scenes and the people depicted on the decorative elements of the mirrors are often helpfully identified by accompanying inscriptions around the mirror edge. Popular subjects were wedding preparations, couples embracing, or a lady in the process of dressing. The most common subject for mirror decoration was mythology and scenes are often framed by a border of twisted ivy, vine, myrtle, or laurel leaves.

The first indigenous pottery of Etruria was the impasto pottery of the Villanovan culture. These relatively primitive wares contained many impurities in the clay and were fired only at a low temperature. By the end of the 8th century BC potters had managed to improve the quality of their wares. Small model houses and biconical urns were popular forms. Biconical urns are those made of two vases with one smaller one acting as a lid for the other. They were frequently used to store cremated human remains.

Chronologically the next pottery type was red on white wares. This type of pottery style originated in Phoenicia. The style was produced in Etruria from the end of the 8th century BC and into the 7th century BC. The style was most extensively produced at Cerveteri and Veii. The red-colored vessels were often covered with a white slip. They were then decorated with red geometric or floral designs. Alternatively white was often used to create designs on the unpainted red background. Large storage vases with small handled lids are common of this type. Kraters were also common and were frequently decorated with scenes such as sea battles and marching warriors.

Bucchero wares largely replaced impasto wares from the 7th century BC onward. Bucchero ware was used for everyday purposes as well as for funerary and votive objects. Turned on a wheel this new type of pottery was characterized by more even firing and a distinctive glossy dark grey to black finish. Vessels were of all types were produced. They were mostly plain but they were often decorated with simple lines, spirals, and dotted fans incised onto the surface. Three-dimensional figures of humans and animals were also added on occasion. The Etruscans were Mediterranean-wide traders. Bucchero ware was exported beyond Italy to places as far afield as Iberia, the Levant, and the Black Sea area.

Bucchero wares largely replaced impasto wares from the 7th century BC onward. Bucchero ware was used for everyday purposes as well as for funerary and votive objects. Turned on a wheel this new type of pottery was characterized by more even firing and a distinctive glossy dark grey to black finish. Vessels were of all types were produced. They were mostly plain but they were often decorated with simple lines, spirals, and dotted fans incised onto the surface. Three-dimensional figures of humans and animals were also added on occasion. The Etruscans were Mediterranean-wide traders. Bucchero ware was exported beyond Italy to places as far afield as Iberia, the Levant, and the Black Sea area.

By the early 5th century BC bucchero was replaced by finer Etruscan pottery such as black- and red-figure wares. These were influenced by imported Greek pottery of the period. One unusual field of pottery which became a particular Etruscan specialty was the creation of terracotta roof decorations. The idea went back to the Villanovan culture. However the Etruscans went one step further and produced life-size figure sculpture to decorate the roofs of their temples. The most impressive survivor from this field is the striding figure of Apollo from the Portonaccio Temple at Veii which is dated to about 510 BC. Private buildings also had terracotta decoration in the form of plants, palms, and figurines. Additionally terracotta plaques with scenes from mythology were often attached to outer walls of all types of buildings.

The Etruscans cremated the remains of the dead. They were buried in funerary urns or decorated sarcophagi made of terracotta. Both urns and sarcophagi might feature a sculpted figure of the deceased on the lid. In the instance of sarcophagi they sometimes depicted a couple. The most famous example of this latter type is the “Sarcophagus of the Married Couple from Cerveteri”, now in the Villa Giulia in Rome. In the Hellenistic Period the funerary arts really took off. Figures depicted although rendered in similar poses to the 6th-century BC sarcophagi versions, become less idealized and rendered much more realistic portrayals of the dead. They usually portray only one individual and were originally painted in bright colors. The “Sarcophagus of Seianti Thanunia Tlesnasa from Chiusi” is an excellent example.

The Etruscans were great collectors of foreign art but their own works were widely exported too. Bucchero wares have been found across the Mediterranean from Spain to Syria. The Etruscans also traded with central and northern European tribes. Thus their artworks reached the Celts across the Alps in modern Switzerland and Germany. The greatest influence of Etruscan art was on their immediate neighbors and cultural successors in general, the Romans. Rome conquered the Etruscan cities in the 3rd century BC. However these cities remained artistically independent centers of art production. However over time art works did reflect Roman tastes and culture however. Eventually at some point that Etruscan and Roman art often became indistinguishable.

An excellent example of the proximity between the two is the bronze statue of an orator from Pila, near modern Perugia. Cast in 90 BC the figure, with his toga and raised right arm is as quintessentially Roman as a statue from the imperial period. The Etruscans played an obvious role as a cultural link between the Greek world and ancient Rome. However perhaps the most lasting legacy of Etruscan artists is the realism they oftentimes achieved in portraiture.

An excellent example of the proximity between the two is the bronze statue of an orator from Pila, near modern Perugia. Cast in 90 BC the figure, with his toga and raised right arm is as quintessentially Roman as a statue from the imperial period. The Etruscans played an obvious role as a cultural link between the Greek world and ancient Rome. However perhaps the most lasting legacy of Etruscan artists is the realism they oftentimes achieved in portraiture.

Although still partially idealized the funerary portraits on Etruscan sarcophagi are honest enough to reveal the physical flaws of the individual. There is a clear attempt by artists to illustrate the unique personality of the individual. This was the same conceptual idealism that their Roman successors would also strive for. Roman artists were quite successful in capturing very often moving portraits of private Roman citizens brilliantly rendered in paint, metal, and stone. Much of the success Roman artists enjoyed is attributable to their Etruscan predecessors [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Ancient Greek Pottery: We know the names of some potters and painters of Greek vases because they signed their work. Generally a painter signed his name followed by some form of the verb 'painted', while a potter (or perhaps the painter writing for him) signed his name with 'made'. Sometimes the same person might both pot and paint: Exekias and Epiktetos, for example, sign as both potter and painter. At other times potter and painter were different people and one or both of them signed. However, not all painters or potters signed all their work. Some seem never to have signed their vases, unless by chance signed pieces by these craftsmen have not survived.

Even in the case of unsigned vases, it is sometimes possible, through close examination of minute details of style, to recognize pieces by the same artist. The attribution of unsigned Athenian black- and red-figured vases to both named and anonymous painters was pioneered in the twentieth century by Sir John Davidson Beazley. Other scholars have developed similar systems for other groups of vases, most notably Professor A.D. Trendall for South Italian red-figured wares. For ease of reference Beazley and the others gave various nick-names to the anonymous painters whom they identified.

Some are called after the known potters with whom they seem to have collaborated - the Brygos and Sotades Painters, for example, are named from the potters of those names. Other painters are named from the find-spot or current location of a key vase, such as the Lipari or Berlin Painters. A few, such as the Burgon Painter, take their names from former or current owners of key vases. Others are named from the subjects of key vases, such as the Niobid, Siren or Cyclops Painters, or else from peculiarities of style, such as The Affecter or Elbows Out Painters. [British Museum].

Some are called after the known potters with whom they seem to have collaborated - the Brygos and Sotades Painters, for example, are named from the potters of those names. Other painters are named from the find-spot or current location of a key vase, such as the Lipari or Berlin Painters. A few, such as the Burgon Painter, take their names from former or current owners of key vases. Others are named from the subjects of key vases, such as the Niobid, Siren or Cyclops Painters, or else from peculiarities of style, such as The Affecter or Elbows Out Painters. [British Museum].

Ancient Greek Sculpture: Greek sculpture from 800 to 300 B.C. took early inspiration from Egyptian and Near Eastern monumental art, and over centuries evolved into a uniquely Greek vision of the art form. Greek artists would reach a peak of artistic excellence which captured the human form in a way never before seen and which was much copied. Greek sculptors were particularly concerned with proportion, poise, and the idealized perfection of the human body, and their figures in stone and bronze have become some of the most recognizable pieces of art ever produced by any civilization.

From the 8th century B.C., Archaic Greece saw a rise in the production of small solid figures in clay, ivory, and bronze. No doubt, wood too was a commonly used medium but its susceptibility to erosion has meant few examples have survived. Bronze figures, human heads and, in particular, griffins were used as attachments to bronze vessels such as cauldrons. In style, the human figures resemble those in contemporary Geometric pottery designs, having elongated limbs and a triangular torso. Animal figures were also produced in large numbers, especially the horse, and many have been found across Greece at sanctuary sites such as Olympia and Delphi, indicating their common function as votive offerings.

The oldest Greek stone sculptures (of limestone) date from the mid-7th century B.C. and were found at Thera. In this period, bronze free-standing figures with their own base became more common, and more ambitious subjects were attempted such as warriors, charioteers, and musicians. Marble sculpture appears from the early 6th century B.C. and the first monumental, life-size statues began to be produced. These had a commemorative function, either offered at sanctuaries in symbolic service to the gods or used as grave markers.

The earliest large stone figures (kouroi - nude male youths and kore - clothed female figures) were rigid as in Egyptian monumental statues with the arms held straight at the sides, the feet are almost together and the eyes stare blankly ahead without any particular facial expression. These rather static figures slowly evolved though and with ever greater details added to hair and muscles, the figures began to come to life. Slowly, arms become slightly bent giving them muscular tension and one leg (usually the right) is placed slightly more forward, giving a sense of dynamic movement to the statue.

The earliest large stone figures (kouroi - nude male youths and kore - clothed female figures) were rigid as in Egyptian monumental statues with the arms held straight at the sides, the feet are almost together and the eyes stare blankly ahead without any particular facial expression. These rather static figures slowly evolved though and with ever greater details added to hair and muscles, the figures began to come to life. Slowly, arms become slightly bent giving them muscular tension and one leg (usually the right) is placed slightly more forward, giving a sense of dynamic movement to the statue.

Excellent examples of this style of figure are the kouroi of Argos, dedicated at Delphi (circa 580 B.C.). Around 480 B.C., the last kouroi become ever more life-like, the weight is carried on the left leg, the right hip is lower, the buttocks and shoulders more relaxed, the head is not quite so rigid, and there is a hint of a smile. Female kore followed a similar evolution, particularly in the sculpting of their clothes which were rendered in an ever-more realistic and complex way. A more natural proportion of the figure was also established where the head became 1:7 with the body, irrespective of the actual size of the statue.

By 500 B.C. Greek sculptors were finally breaking away from the rigid rules of Archaic conceptual art and beginning to re-produce what they actually observed in real life. In the Classical period, Greek sculptors would break off the shackles of convention and achieve what no-one else had ever before attempted. They created life-size and life-like sculpture which glorified the human and especially nude male form. Even more was achieved than this though. Marble turned out to be a wonderful medium for rendering what all sculptors strive for: that is to make the piece seem carved from the inside rather than chiseled from the outside.

Figures become sensuous and appear frozen in action; it seems that only a second ago they were actually alive. Faces are given more expression and whole figures strike a particular mood. Clothes too become more subtle in their rendering and cling to the contours of the body in what has been described as ‘wind-blown’ or the ‘wet-look’. Quite simply, the sculptures no longer seemed to be sculptures but were figures instilled with life and verve. To see how such realism was achieved we must return again to the beginning and examine more closely the materials and tools at the disposal of the artist and the techniques employed to transform raw materials into art.

Early Greek sculpture was most often in bronze and porous limestone, but whilst bronze seems never to have gone out of fashion, the stone of choice would become marble. The best was from Naxos - close-grained and sparkling, Parian (from Paros) - with a rougher grain and more translucent, and Pentelic (near Athens) - more opaque and which turned a soft honey color with age (due to its iron content). However, stone was chosen for its workability rather than its decoration as the majority of Greek sculpture was not polished but painted, often rather garishly for modern tastes.

Early Greek sculpture was most often in bronze and porous limestone, but whilst bronze seems never to have gone out of fashion, the stone of choice would become marble. The best was from Naxos - close-grained and sparkling, Parian (from Paros) - with a rougher grain and more translucent, and Pentelic (near Athens) - more opaque and which turned a soft honey color with age (due to its iron content). However, stone was chosen for its workability rather than its decoration as the majority of Greek sculpture was not polished but painted, often rather garishly for modern tastes.

Marble was quarried using bow drills and wooden wedges soaked in water to break away workable blocks. Generally, larger figures were not produced from a single piece of marble, but important additions such as arms were sculpted separately and fixed to the main body with dowels. Using iron tools, the sculptor would work the block from all directions (perhaps with an eye on a small-scale model to guide proportions), first using a pointed tool to remove more substantial pieces of marble. Next, a combination of a five-claw chisel, flat chisels of various sizes, and small hand drills were used to sculpt the fine details.

The surface of the stone was then finished off with an abrasive powder (usually emery from Naxos) but rarely polished. The statue was then attached to a plinth using a lead fixture or sometimes placed on a single column (e.g. the Naxian sphinx at Delphi, circa 560 B.C.). The finishing touches to statues were added using paint. Skin, hair, eyebrows, lips, and patterns on clothing were added in bright colors. Eyes were often inlaid using bone, crystal, or glass. Finally, additions in bronze might be added such as spears, swords, helmets, jewelry, and diadems, and some statues even had a small bronze disc (meniskoi) suspended over the head to prevent birds from defacing the figure.

The other favored material in Greek sculpture was bronze. Unfortunately, this material was always in demand for re-use in later periods, whereas broken marble is not much use to anyone, and so marble sculpture has better survived for posterity. Consequently, the quantity of surviving examples of bronze sculpture (no more than twelve) is not perhaps indicative of the fact that more bronze sculpture may well have been produced than in marble and the quality of the few surviving bronzes demonstrates the excellence we have lost. Very often at archaeological sites we may see rows of bare stone plinths, silent witnesses to art’s loss.

The early solid bronze sculptures made way for larger pieces with a non-bronze core which was sometimes removed to leave a hollow figure. The most common production of bronze statues used the lost-wax technique. This involved making a core almost the size of the desired figure (or body part if not creating a whole figure) which was then coated in wax and the details sculpted. The whole was then covered in clay fixed to the core at certain points using rods. The wax was then melted out and molten bronze poured into the space once occupied by the wax. When set, the clay was removed and the surface finished off by scraping, fine engraving and polishing. Sometimes copper or silver additions were used for lips, nipples and teeth. Eyes were inlaid as in marble sculpture.

The early solid bronze sculptures made way for larger pieces with a non-bronze core which was sometimes removed to leave a hollow figure. The most common production of bronze statues used the lost-wax technique. This involved making a core almost the size of the desired figure (or body part if not creating a whole figure) which was then coated in wax and the details sculpted. The whole was then covered in clay fixed to the core at certain points using rods. The wax was then melted out and molten bronze poured into the space once occupied by the wax. When set, the clay was removed and the surface finished off by scraping, fine engraving and polishing. Sometimes copper or silver additions were used for lips, nipples and teeth. Eyes were inlaid as in marble sculpture.

Many statues are signed so that we know the names of the most successful artists who became famous in their own lifetimes. Naming a few, we may start with the most famous of all, Phidias, the artist who created the gigantic chryselephantine statues of Athena (circa 438 B.C.) and Zeus (circa 456 B.C.) which resided, respectively, in the Parthenon of Athens and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The latter sculpture was considered one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Polykleitos, who besides creating great sculpture such as the Doryphoros (Spearbearer), also wrote a treatise, the Kanon, on techniques of sculpture. Coryphoros emphasized the importance of correct proportion.

Other important sculptors were Kresilas, who made the much copied portrait of Pericles (circa 425 B.C.), Praxiteles, whose Aphrodite (circa 340 B.C.) was the first full female nude, and Kallimachos, who is credited with creating the Corinthian capital and whose distinctive dancing figures were much copied in Roman times. Sculptors often found permanent employment in the great sanctuary sites and archaeology has revealed the workshop of Phidias at Olympia. Various broken clay moulds were found in the workshop and also the master’s own personal clay mug, inscribed ‘I belong to Phidias’. Another feature of sanctuary sites was the cleaners and polishers who maintained the shiny reddish-brass color of bronze figures as the Greeks did not appreciate the dark-green patina which occurs from weathering (and which surviving statues have gained).

Greek sculpture is, however, not limited to standing figures. Portrait busts, relief panels, grave monuments, and objects in stone such as perirrhanteria (basins supported by three or four standing female figures) also tested the skills of the Greek sculptor. Another important branch of the art form was architectural sculpture, prevalent from the late 6th century B.C. on the pediments, friezes, and metopes of temples and treasury buildings. However, it is in figure sculpture that one may find some of the great masterpieces of Classical antiquity, and testimony to their class and popularity is that copies were very often made, particularly in the Roman period.

Indeed, it is fortunate that the Romans loved Greek sculpture and copied it so widely because it is often these copies which survive rather than the Greek originals. The copies, however, present their own problems as they obviously lack the original master’s touch, may swap medium from bronze to marble, and even mix body parts, particularly heads. Although words will rarely ever do justice to the visual arts, we may list here a few examples of some of the most celebrated pieces of Greek sculpture. In bronze, three pieces stand out, all saved from the sea (a better custodian of fine bronzes than people have been): the Zeus or Poseidon of Artemesium and the two warriors of Riace (all three: 460-450 B.C.).

Indeed, it is fortunate that the Romans loved Greek sculpture and copied it so widely because it is often these copies which survive rather than the Greek originals. The copies, however, present their own problems as they obviously lack the original master’s touch, may swap medium from bronze to marble, and even mix body parts, particularly heads. Although words will rarely ever do justice to the visual arts, we may list here a few examples of some of the most celebrated pieces of Greek sculpture. In bronze, three pieces stand out, all saved from the sea (a better custodian of fine bronzes than people have been): the Zeus or Poseidon of Artemesium and the two warriors of Riace (all three: 460-450 B.C.).

The former could be Zeus (the posture is more common for that deity) or Poseidon and is a transitional piece between Archaic and Classical art as the figure is extremely life-like, but in fact the proportions are not exact (e.g. the limbs are extended). However, as Boardman eloquently describes, ‘(it) manages to be both vigorously threatening and static in its perfect balance’; the onlooker is left in no doubt at all that this is a great god. The Riace warriors are also magnificent with the added detail of finely sculpted hair and beards. More Classical in style, they are perfectly proportioned and their poise is rendered in such a way as to suggest that they may well step off of the plinth at any moment.

In marble, two standout pieces are the Diskobolos or discus thrower attributed to Myron (circa 450 B.C.) and the Nike of Paionios at Olympia (circa 420 B.C.). The discus thrower is one of the most copied statues from antiquity and it suggests powerful muscular motion caught for a split second, as in a photo. The piece is also interesting because it is carved in such a way (in a single plain) as to be seen from one viewpoint (like a relief carving with its background removed). The Nike is an excellent example of the ‘wet-look’ where the light material of the clothing is pressed against the contours of the body, and the figure seems semi-suspended in the air and only just to have landed her toes on the plinth.

Greek sculpture then, broke free from the artistic conventions which had held sway for centuries across many civilizations, and instead of reproducing figures according to a prescribed formula, they were free to pursue the idealized form of the human body. Hard, lifeless material was somehow magically transformed into such intangible qualities as poise, mood, and grace to create some of the great masterpieces of world art and inspire and influence the artists who were to follow in Hellenistic and Roman times who would go on to produce more masterpieces such as the Venus de Milo.

Further, the perfection in proportions of the human body achieved by Greek sculptors continues to inspire artists even today. The great Greek works are even consulted by 3D artists to create accurate virtual images and by sporting governing bodies who have compared athletes bodies with Greek sculpture to check abnormal muscle development achieved through the use of banned substances such as steroids. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Further, the perfection in proportions of the human body achieved by Greek sculptors continues to inspire artists even today. The great Greek works are even consulted by 3D artists to create accurate virtual images and by sporting governing bodies who have compared athletes bodies with Greek sculpture to check abnormal muscle development achieved through the use of banned substances such as steroids. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Ancient Celtic Art: Celtic art is generally used by art historians to refer to art of the La Tène period across Europe. The Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland is referred to as “Insular” art in art history. The term Celtic art when used by the general public usually refers to the latter, Insular art. Both styles absorbed considerable influences from non-Celtic sources. Both retained a preference for geometrical decoration over figurative subjects. However when figurative subjects are depicted they are often extremely stylized when. Narrative scenes in Celtic art only appear under outside influence.

Energetic circular forms, triskeles and spirals are quite characteristic. Much of the surviving material is in precious metal, which no doubt gives a very unrepresentative picture. However apart from Pictish stones and the Insular high crosses, large monumental sculpture is very rare. Possibly it was originally common in wood, even with decorative carving, but only survived in stone. Celts were also able to create developed musical instruments such as the carnyces. These famous war trumpets were used before battle to frighten the enemy. The best preserved archaeological specimens were found in Tintignac (Gaul) in 2004. They were decorated with a boar head or a snake head.

The interlace patterns that are often regarded as typical of "Celtic art" were characteristic of the whole of the British Isles. The style is referred to as Hiberno-Saxon art. This artistic style incorporated elements of La Tène, Late Roman, and, most importantly, animal Style II of Germanic Migration Period art. The style was taken up with great skill and enthusiasm by Celtic artists in metalwork and illuminated manuscripts. The forms used for the finest Insular art were all adopted from the Roman world.

Gospel books like the Book of Kells and Book of Lindisfarne, chalices like the Ardagh Chalice and Derrynaflan Chalice, and penannular brooches like the Tara Brooch, are all works from the period of peak achievement of Insular art. The period lasted from the 7th to the 9th centuries, prior to the Viking attacks which so sharply set back cultural life. In contrast the less well known but often spectacular art of the richest earlier Continental Celts often adopted elements of Roman, Greek and other "foreign" styles. This time frame was prior to the Roman conquest, and the Celts may have used imported craftsmen to decorate objects that were distinctively Celtic.

Some Celtic elements remained in popular art after the Roman conquests. This was especially true with Ancient Roman pottery, of which Gaul was actually the largest producer. Most of that produced was in Italian styles. However work was also produced to local Celtic tastes. This included figurines of deities and wares painted with animals and other subjects in highly formalized styles. Roman Britain also took more interest in enamel than most of the Empire. The development of champlevé technique was probably important to the later Medieval art of the whole of Europe. The energy and freedom of Insular decoration was an important element therein.

Some Celtic elements remained in popular art after the Roman conquests. This was especially true with Ancient Roman pottery, of which Gaul was actually the largest producer. Most of that produced was in Italian styles. However work was also produced to local Celtic tastes. This included figurines of deities and wares painted with animals and other subjects in highly formalized styles. Roman Britain also took more interest in enamel than most of the Empire. The development of champlevé technique was probably important to the later Medieval art of the whole of Europe. The energy and freedom of Insular decoration was an important element therein.

Viking Art: Art made by Scandinavians during the Viking Age (about 790-1100 AD) mostly encompassed the decoration of functional objects made of wood, metal, stone, textile and other materials. They were decorated with relief carvings, engravings of animal shapes and abstract patterns. The motif of the stylized animal known as ‘zoomorphic’ art was Viking Age art’s most popular motif. The style stems from a tradition that existed across north-western Europe from as early as the 4th century AD. However the art form did not develop into an established Scandinavia native style until the end of the 7th century. Often these animals twist and churn across the surface of any number of object surfaces. Interspersed with plants, they adorned decorated carts, engraved jewelry and weapons, wall-tapestries and memorial stones.

Narrative art of the region that tells an actual story is found in only a few instances before the last stage of the Viking Age. There include the rare tapestries that have evaded being unraveled by the passage of time. There are also the picture stones found on the island of Gotland in present-day Sweden. Besides the many different carved surfaces, some instances of more properly 3D-art are also preserved. These are mostly in the form of animal heads that were used to adorn posts, carts or caskets. Several succeeding and sometimes overlapping styles have been identified within Viking Age decorative art. They are usually named after the finding place of a famous example of that style. These would include:

---Style E (late 8th century to late 9th century. Important finds from Broa (Gotland, Sweden) and the Oseberg ship burial (Norway). Long animal bodies; small heads in profile with bulging eyes. ‘Gripping-beasts’ with muscular bodies and claws gripping everything nearby.

---Borre Style (about 850 to late 10th century. Ribbon plait (‘ring-chain’, a symmetrical interlaced pattern). A single gripping-beast with triangular head and contorted body. The latter was most widespread of all the styles, found throughout Scandinavia and across the Viking colonies.

---The Jelling Style (just before 900 through the end of the 10th century). Beast with a ribbon-like body. The head depicted in profile; usually double-contoured body which is beaded. The style is closely related to and overlapping with the Borre style.

---The Jelling Style (just before 900 through the end of the 10th century). Beast with a ribbon-like body. The head depicted in profile; usually double-contoured body which is beaded. The style is closely related to and overlapping with the Borre style.

---The Mammen Style (about 950-1000 AD). Great fighting beasts with spiral-shaped shoulders and hips. They are often asymmetrical; vigorous and dynamic; with ribbon and plant elements.

---The Ringerike Style (about 990-1050 AD). Large animal in a dynamic pose. Often suggesting movement; powerful and elegant. Often with plant ornaments, popular in England and especially Ireland.

---The Urnes Style (about 1040 to at least 100 AD). Also named ‘runestone style’. Very elegant, asymmetrical motif of a great beast. Often with interweaving, looped snakes and tendrils. Very popular in Ireland.

Rather than creating art for art’s sake, Viking Age Scandinavians almost exclusively made applied art. Everyday objects were embellished to make them more attractive. Although wood and textile must have been prime vehicles for Viking Age art, their often more expensive counterparts in metal and stone do better at surviving. This results in over-representation and bias in the archaeological record. The rarer pictorial art often seems to match known stories about Norse mythology. These might depict such scenes as a Valkyrie welcoming a warrior into Valhalla or Sigurd the Dragonslayer’s story.

Religion permeated life in the Viking Age and was especially important in Viking art. Artists and craftsmen certainly would have been important people as art was generally created not for its own sake, Rather it was cr5eated as a mark of social prestige, often commissioned by the upper levels of society. Even though much of its meaning is lost to us, we can be confident of our interpretations at least in cases where myths known from Old Norse literature can be identified. Elements of Viking mythology are present in artistic ornamentation. Even if obscure today, that religious content would have been obvious to viewers at that time.

Viking art was link both with the higher levels of society and with religion. This may explain why Viking Age art styles were for the most part common across Scandinavia throughout all levels of society. Copying was also standard-practice, which is not so odd considering the primarily decorative purpose for Viking art. Viking Age art’s favored materials were mostly substances that could be carved or engraved. These included wood, stone, metal, and also bone and amber. Textile, leather or cloth, in the shape of colorful wall tapestries adorned with pictorial scenes, were also commonly used. However along with wood these materials were rather poor at standing the test of time. Few remain extant.

Viking art was link both with the higher levels of society and with religion. This may explain why Viking Age art styles were for the most part common across Scandinavia throughout all levels of society. Copying was also standard-practice, which is not so odd considering the primarily decorative purpose for Viking art. Viking Age art’s favored materials were mostly substances that could be carved or engraved. These included wood, stone, metal, and also bone and amber. Textile, leather or cloth, in the shape of colorful wall tapestries adorned with pictorial scenes, were also commonly used. However along with wood these materials were rather poor at standing the test of time. Few remain extant.