Peoples of the Past: Babylonians by H.W.F. Saggs.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with dustjacket: 192 pages. Publisher: University of Oklahoma Press; (1995). Dimensions: 9¾ x 7 inches; 1¾ pounds. Babylon stands with Athens and Rome as a cultural ancestor of western civilization. It was founded by the people of ancient Mesopotamia, who settled in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers before the fourth millennium B.C. Some of the earliest experiments in agriculture and irrigation, the invention of writing, the birth of mathematics and the development of urban life all began there. Biblical associations are also numerous, from Nineveh to the Tower of Babel and the Flood.

In "Babylonians", H. W. F. Saggs describes the ebb and flow in the successive fortunes of the Sumerians, Akkadians, Amorites, and Babylonians who flourished in this region. Using evidence from pottery, cuneiform tablets, cylinder seals, early architecture and metallurgy, he illuminates the myths, religion, languages, trade, politics, and warfare, as well as the legacy, of the Babylonians and their predecessors.

During the twentieth century, collaboration by archaeologists from many nations has greatly increased the range of archaeological evidence, while work by linguists has gradually unlocked the secrets of the thousands of clay tablets recovered from the area. Today the historical record for some periods of ancient Mesopotamia is substantially better than for some centuries of Europe in the Christian era. Gaps and uncertainties remain, but Babylonians conveys a rich and fascinating picture of the development of this remarkable civilization from before the beginning of the third millennium B.C.

CONDITION: NEW. New hardcover w/dustjacket. University of Oklahoma (1995) 192 pages. Unblemished except for very faint (almost indiscernable) shelfwear to dustjacket and covers. Pages are pristine; clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. Condition is entirely consistent with new stock from a traditional brick-and-mortar bookstore environment (such as Barnes & Noble, B. Dalton, Borders, etc.) wherein new books might show minor signs of shelfwear, consequence simply of being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #1681e.

PLEASE SEE IMAGES BELOW FOR SAMPLE PAGES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

REVIEW: The people of ancient Mesopotamia, who settled in the "fertile crescent" between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers before the fourth millennium B.C., laid the foundations of Western civilization. Some of the earliest experiments in agriculture and irrigation, the invention of writing, the birth of mathematics and the development of urban life began there. Many fundamental developments in human society; from hunter-gatherer to farmer, from village to city-state; first occurred in this area. Biblical associations also are numerous, from Nineveh to the Tower of Babel and the Flood.

Professor H. W. F. Saggs describes the ebb and flow in the successive fortunes of the Sumerians, Akkadians, Amorites and Babylonians. Using evidence from pottery, cuneiform tablets, cylinder seals, early architecture and metallurgy; he illuminates the myths, religion, languages, trade, politics and warfare, as well as the legacy, of the Babylonians and their predecessors. Professor Henry W. F. Saggs is Professor Emeritus of Semitic Languages at University College, Cardiff, and the author of numerous books including "Civilization before Greece and Rome" (1989), "The Might that was Assyria" (1984), and "The Greatness that was Babylon" (1962).

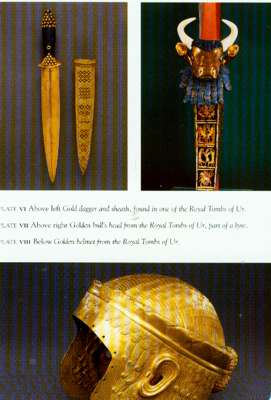

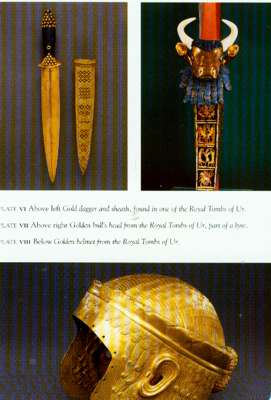

REVIEW: Saggs describes the ebb and flow in the fortunes of the Sumerians, Akkadians, Amorites, and Babylonians, emphasizing their achievements in the formation of the city-state and the development of writing. Using evidence from pottery, cuneiform tablets, and early architecture, and numerous black-and-white and color photos, he illuminates the myths, religion, politics, and warfare of the Babylonians, and puts the numerous Biblical references to the Babylonian Empire in historical perspective.

REVIEW: H. W. F. Saggs' Babylonians is recommended for college-level students of ancient Mesopotamia: Professor Saggs uses evidence from pottery, architecture and metallurgy to recreate and examine the myths, religions, language, trade, politics, and warfare of the Babylonians and the predecessors. The book contains 12 color and 84 black-and-white illustrations as well as two maps.

REVIEW: Saggs puts together a very intriguing review of life in Early Mesopotamia, using archaeological evidence and historical texts. I thoroughly enjoyed this book. I highly recommend this book to any student doing research on the early settlements in the Sumer and Akkad region. The book covers briefly the Uruk period and in much more detail the Agade, Ur III, and Old Babylonian periods. Another book that you would also find of great interest is H. Crawford's book called "Sumer and the Sumerians". She examines the Uruk period in more detail than Saggs. Both books are of great value to professor, student, and history enthusiast alike.

REVIEW: Highly recommended for style and information. I found myself unable to put this book down. However, I feel that the title is a bit misleading in that while it does cover the Babylonians it also covers a whole lot more. To me the book served as an excellent summary of the history of ancient Mesopotamia from the Sumerians right on through the Babylonians. I borrowed it from the university library and ordered my own copy after I had read it.

REVIEW: This book really dishes out the skinny on ancient Mesopatamia. Saggs begins by describing the archaeologists and historians who rediscovered a lot of the ancient Mesopotamian history. Then he relates that history from the Neolithic all the way to the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Saggs' style is quite lucid and the pictures add a lot to the material Saggs presents in this work. He really does an awesome job at introducing the amazing civilizations that made up ancient Mesopotamia. I highly recommend this book.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

Babylon: Babylon is the most famous city from ancient Mesopotamia whose ruins lie in modern-day Iraq 59 miles (94 kilometers) southwest of Baghdad. The name is thought to derive from bav-il or bav-ilim which, in the Akkadian language of the time, meant ‘Gate of God’ or `Gate of the Gods’ and `Babylon’ coming from the Greek. The city owes its fame (or infamy) to the many references the Bible makes to it; all of which are unfavorable. In the Book of Genesis, chapter 11, Babylon is featured in the story of The Tower of Babel and the Hebrews claimed the city was named for the confusion which ensued after God caused the people to begin speaking in different languages so they would not be able to complete their great tower to the heavens (the Hebrew word bavel means "confusion").

Babylon also appears prominently in the biblical books of Daniel, Jeremiah, and Isaiah, among others, and, most notably, The Book of Revelation. It was these biblical references which sparked interest in Mesopotamian archaeology and the expedition by the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey who first excavated the ruins of Babylon in 1899 A.D. Outside of the sinful reputation given it by the Bible, the city is known for its impressive walls and buildings, its reputation as a great seat of learning and culture, the formation of a code of law which pre-dates the Mosaic Law, and for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon which were man-made terraces of flora and fauna, watered by machinery, which were cited by Herodotus as one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Babylon also appears prominently in the biblical books of Daniel, Jeremiah, and Isaiah, among others, and, most notably, The Book of Revelation. It was these biblical references which sparked interest in Mesopotamian archaeology and the expedition by the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey who first excavated the ruins of Babylon in 1899 A.D. Outside of the sinful reputation given it by the Bible, the city is known for its impressive walls and buildings, its reputation as a great seat of learning and culture, the formation of a code of law which pre-dates the Mosaic Law, and for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon which were man-made terraces of flora and fauna, watered by machinery, which were cited by Herodotus as one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Babylon was founded at some point prior to the reign of Sargon of Akkad (also known as Sargon the Great) who ruled from 2334-2279 B.C. and claimed to have built temples at Babylon (other ancient sources seem to indicate that Sargon himself founded the city). At that time, Babylon seems to have been a minor city or perhaps a large port town on the Euphrates River at the point where it runs closest to the river Tigris. Whatever early role the city played in the ancient world is lost to modern-day scholars because the water level in the region has risen steadily over the centuries and the ruins of Old Babylon have become inaccessible.

The ruins which were excavated by Koldewey, and are visible today, date only to well over one thousand years after the city was founded. The historian Paul Kriwaczek, among other scholars, claims it was established by the Amorites following the collapse of the Third Dynasty of Ur. This information, and any other pertaining to Old Babylon, comes to us today through artifacts which were carried away from the city after the Persian invasion or those which were created elsewhere. The known history of Babylon, then, begins with its most famous king: Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.). This obscure Amorite prince ascended to the throne upon the abdication of his father, King Sin-Muballit, and fairly quickly transformed the city into one of the most powerful and influential in all of Mesopotamia.

Hammurabi’s law codes are well known but are only one example of the policies he implemented to maintain peace and encourage prosperity. He enlarged and heightened the walls of the city, engaged in great public works which included opulent temples and canals, and made diplomacy an integral part of his administration. So successful was he in both diplomacy and war that, by 1755 B.C., he had united all of Mesopotamia under the rule of Babylon which, at this time, was the largest city in the world, and named his realm Babylonia.

Hammurabi’s law codes are well known but are only one example of the policies he implemented to maintain peace and encourage prosperity. He enlarged and heightened the walls of the city, engaged in great public works which included opulent temples and canals, and made diplomacy an integral part of his administration. So successful was he in both diplomacy and war that, by 1755 B.C., he had united all of Mesopotamia under the rule of Babylon which, at this time, was the largest city in the world, and named his realm Babylonia.

Following Hammurabi’s death, his empire fell apart and Babylonia dwindled in size and scope until Babylon was easily sacked by the Hittites in 1595 B.C. The Kassites followed the Hittites and re-named the city Karanduniash. The meaning of this name is not clear. The Assyrians then followed the Kassites in dominating the region and, under the reign of the Assyrian ruler Sennacherib (reigned 705-681 B.C.), Babylon revolted. Sennacherib had the city sacked, razed, and the ruins scattered as a lesson to others. His extreme measures were considered impious by the people generally and Sennacherib’s court specifically and he was soon after assassinated by his sons.

His successor, Esarhaddon, re-built Babylon and returned it to its former glory. The city later rose in revolt against Ashurbanipal of Nineveh who besieged and defeated the city but did not damage it to any great extent and, in fact, personally purified Babylon of the evil spirits which were thought to have led to the trouble. The reputation of the city as a center of learning and culture was already well established by this time. After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, a Chaldean named Nabopolassar took the throne of Babylon and, through careful alliances, created the Neo-Babylonian Empire. His son, Nebuchadnezzar II (604-561 B.C.), renovated the city so that it covered 900 hectares (2,200 acres) of land and boasted some the most beautiful and impressive structures in all of Mesopotamia.

Every ancient writer to make mention of the city of Babylon, outside of those responsible for the stories in the Bible, does so with a tone of awe and reverence. Herodotus, for example, writes: "The city stands on a broad plain, and is an exact square, a hundred and twenty stadia in length each way, so that the entire circuit is four hundred and eighty stadia. While such is its size, in magnificence there is no other city that approaches to it. It is surrounded, in the first place, by a broad and deep moat, full of water, behind which rises a wall fifty royal cubits in width and two hundred in height."

Every ancient writer to make mention of the city of Babylon, outside of those responsible for the stories in the Bible, does so with a tone of awe and reverence. Herodotus, for example, writes: "The city stands on a broad plain, and is an exact square, a hundred and twenty stadia in length each way, so that the entire circuit is four hundred and eighty stadia. While such is its size, in magnificence there is no other city that approaches to it. It is surrounded, in the first place, by a broad and deep moat, full of water, behind which rises a wall fifty royal cubits in width and two hundred in height."

Although it is generally believed that Herodotus greatly exaggerated the dimensions of the city (and may never have actually visited the place himself) his description echoes the admiration of other writers of the time who recorded the magnificence of Babylon, and especially the great walls, as a wonder of the world. It was under Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon are said to have been constructed and the famous Ishtar Gate built. The Hanging gardens are most explicitly described in a passage from Diodorus Siculus (90-30 B.C.) in his work Bibliotheca Historica Book II.10:

"There was also, because the acropolis, the Hanging Garden, as it is called, which was built, not by Semiramis, but by a later Syrian king to please one of his concubines; for she, they say, being a Persian by race and longing for the meadows of her mountains, asked the king to imitate, through the artifice of a planted garden, the distinctive landscape of Persia. The park extended four plethra on each side, and since the approach to the garden sloped like a hillside and the several parts of the structure rose from one another tier on tier, the appearance of the whole resembled that of a theater."

"When the ascending terraces had been built, there had been constructed beneath them galleries which carried the entire weight of the planted garden and rose little by little one above the other along the approach; and the uppermost gallery, which was fifty cubits high, bore the highest surface of the park, which was made level with the circuit wall of the battlements of the city. Furthermore, the walls, which had been constructed at great expense, were twenty-two feet thick, while the passage-way between each two walls was ten feet wide. The roofs of the galleries were covered over with beams of stone sixteen feet long, inclusive of the overlap, and four feet wide."

"When the ascending terraces had been built, there had been constructed beneath them galleries which carried the entire weight of the planted garden and rose little by little one above the other along the approach; and the uppermost gallery, which was fifty cubits high, bore the highest surface of the park, which was made level with the circuit wall of the battlements of the city. Furthermore, the walls, which had been constructed at great expense, were twenty-two feet thick, while the passage-way between each two walls was ten feet wide. The roofs of the galleries were covered over with beams of stone sixteen feet long, inclusive of the overlap, and four feet wide."

"The roof above these beams had first a layer of reeds laid in great quantities of bitumen, over this two courses of baked brick bonded by cement, and as a third layer a covering of lead, to the end that the moisture from the soil might not penetrate beneath. On all this again earth had been piled to a depth sufficient for the roots of the largest trees; and the ground, which was leveled off, was thickly planted with trees of every kind that, by their great size or any other charm, could give pleasure to beholder."

"And since the galleries, each projecting beyond another, all received the light, they contained many royal lodgings of every description; and there was one gallery which contained openings leading from the topmost surface and machines for supplying the garden with water, the machines raising the water in great abundance from the river, although no one outside could see it being done. Now this park, as I have said, was a later construction."

This part of Diodorus' work concerns the semi-mythical queen Semiramis (most probably based on the actual Assyrian queen Sammu-Ramat who reigned 811-806 B.C.). His reference to "a later Syrian king" follows Herodotus' tendency of referring to Mesopotamia as `Assyria'. Recent scholarship on the subject argues that the Hanging Gardens were never located at Babylon but were instead the creation Sennacherib at his capital of Nineveh. The historian Christopher Scarre writes:

"Sennacherib’s palace [at Nineveh] had all the usual accoutrements of a major Assyrian residence: colossal guardian figures and impressively carved stone reliefs (over 2,000 sculptured slabs in 71 rooms). Its gardens, too, were exceptional." Recent research by British Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley has suggested that these were the famous Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Later writers placed the Hanging Gardens at Babylon, but extensive research has failed to find any trace of them. Sennacherib’s proud account of the palace gardens he created at Nineveh fits that of the Hanging Gardens in several significant details."

"Sennacherib’s palace [at Nineveh] had all the usual accoutrements of a major Assyrian residence: colossal guardian figures and impressively carved stone reliefs (over 2,000 sculptured slabs in 71 rooms). Its gardens, too, were exceptional." Recent research by British Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley has suggested that these were the famous Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Later writers placed the Hanging Gardens at Babylon, but extensive research has failed to find any trace of them. Sennacherib’s proud account of the palace gardens he created at Nineveh fits that of the Hanging Gardens in several significant details."

This period in which the Hanging Gardens were allegedly built was also the time of the Babylonian Exile of the Jews and the period in which the Babylonian Talmud was written. The Euphrates River divided the city in two between an `old’ and a `new’ city with the Temple of Marduk and the great towering ziggurat in the center. Streets and avenues were widened to better accommodate the yearly processional of the statue of the great god Marduk in the journey from his home temple in the city to the New Year Festival Temple outside the Ishtar Gate.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire continued after the death of Nebuchadnezzar II and Babylon continued to play an important role in the region under the rule of Nabonidus and his successor Belshazzar (featured in the biblical Book of Daniel). In 539 B.C. the empire fell to the Persians under Cyrus the Great at the Battle of Opis. Babylon’s walls were impregnable and so the Persians cleverly devised a plan whereby they diverted the course of the Euphrates River so that it fell to a manageable depth. While the residents of the city were distracted by one of their great religious feast days, the Persian army waded the river and marched under the walls of Babylon unnoticed.

It was claimed the city was taken without a fight although documents of the time indicate that repairs had to be made to the walls and some sections of the city and so perhaps the action was not as effortless as the Persian account maintained. Under Persian rule, Babylon flourished as a center of art and education. Cyrus and his successors held the city in great regard and made it the administrative capital of their empire (although at one point the Persian emperor Xerxes felt obliged to lay siege to the city after another revolt).

Babylonian mathematics, cosmology, and astronomy were highly respected and it is thought that Thales of Miletus (known as the first western philosopher) may have studied there and that Pythagoras developed his famous mathematical theorem based upon a Babylonian model. When, after two hundred years, the Persian Empire fell to Alexander the Great in 331 B.C., he also gave great reverence to the city, ordering his men not to damage the buildings nor molest the inhabitants.

Babylonian mathematics, cosmology, and astronomy were highly respected and it is thought that Thales of Miletus (known as the first western philosopher) may have studied there and that Pythagoras developed his famous mathematical theorem based upon a Babylonian model. When, after two hundred years, the Persian Empire fell to Alexander the Great in 331 B.C., he also gave great reverence to the city, ordering his men not to damage the buildings nor molest the inhabitants.

The historian Stephen Bertman writes, “Before his death, Alexander the Great ordered the superstructure of Babylon’s ziggurat pulled down in order that it might be rebuilt with greater splendor. But he never lived to bring his project to completion. Over the centuries, its scattered bricks have been cannibalized by peasants to fulfill humbler dreams. All that is left of the fabled Tower of Babel is the bed of a swampy pond.”

After Alexander’s death at Babylon, his successors (known as "The Diadochi", Greek for "successors") fought over his empire generally and the city specifically to the point where the residents fled for their safety (or, according to one ancient report, were re-located). By the time the Parthian Empire ruled the region in 141 B.C. Babylon was deserted and forgotten. The city steadily fell into ruin and, even during a brief revival under the Sassanid Persians, never approached its former greatness.

In the Muslim conquest of the land in 650 A.D. whatever remained of Babylon was swept away and, in time, was buried beneath the sands. In the 17th and 18th centuries A.D. European travelers began to explore the area and return home with various artifacts. These cuneiform blocks and statues led to an increased interest in the region and, by the 19th century A.D., an interest in biblical archaeology drew men like Robert Koldewey who uncovered the ruins of the once great city of the Gate of the Gods [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Ancient Babylon: Babylon was a key kingdom in ancient Mesopotamia from the 18th to 6th centuries B.C. The city was built on the Euphrates river and divided in equal parts along its left and right banks, with steep embankments to contain the river's seasonal floods. Babylon was originally a small Akkadian town dating from the period of the Akkadian Empire circa 2300 B.C. The town became part of a small independent city-state with the rise of the First Amorite Babylonian Dynasty in the nineteenth century B.C.

Ancient Babylon: Babylon was a key kingdom in ancient Mesopotamia from the 18th to 6th centuries B.C. The city was built on the Euphrates river and divided in equal parts along its left and right banks, with steep embankments to contain the river's seasonal floods. Babylon was originally a small Akkadian town dating from the period of the Akkadian Empire circa 2300 B.C. The town became part of a small independent city-state with the rise of the First Amorite Babylonian Dynasty in the nineteenth century B.C.

After the Amorite king Hammurabi created a short-lived empire in the 18th century B.C., he built Babylon up into a major city and declared himself its king, and southern Mesopotamia became known as Babylonia and Babylon eclipsed Nippur as its holy city. The empire waned under Hammurabi's son Samsu-iluna and Babylon spent long periods under Assyrian, Kassite and Elamite domination. After being destroyed and then rebuilt by the Assyrians, Babylon became the capital of the short lived Neo-Babylonian Empire from 609 to 539 B.C.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, although a number of scholars believe these were actually in the Assyrian capital of Nineveh. After the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the city came under the rule of the Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Roman, and Sassanid empires. It has been estimated that Babylon was the largest city in the world from above 1770–1670 B.C., and again between about 612–320 B.C. It was perhaps the first city to reach a population above 200,000. Estimates for the maximum extent of its area range from 890 to 900 hectares (2,200 acres).

The remains of the city are in present-day Hillah, Babil Governorate, Iraq, about 85 kilometers (53 miles) south of Baghdad, comprising a large tell of broken mud-brick buildings and debris. The main sources of information about Babylon—excavation of the site itself, references in cuneiform texts found elsewhere in Mesopotamia, references in the Bible, descriptions in classical writing (especially by Herodotus), and second-hand descriptions (citing the work of Ctesias and Berossus)—present an incomplete and sometimes contradictory picture of the ancient city even at its peak in the sixth century B.C.

The English name "Babylon" comes from the Greek "Babylon", a transliteration of the Akkadian Babilim. The Babylonian name in the early 2nd millennium B.C. had been Babilli or Babilla, long thought to mean "gate of god" (Bab-Ili). In the Bible, the name appears as Babel, interpreted in the Hebrew Scriptures' Book of Genesis to mean "confusion", from the verb bilbél. Ancient records in some situations use Babylon as a name for other cities, including cities like Borsippa within Babylon's sphere of influence, and Nineveh for a short period after the Assyrian sack of Babylon.

The English name "Babylon" comes from the Greek "Babylon", a transliteration of the Akkadian Babilim. The Babylonian name in the early 2nd millennium B.C. had been Babilli or Babilla, long thought to mean "gate of god" (Bab-Ili). In the Bible, the name appears as Babel, interpreted in the Hebrew Scriptures' Book of Genesis to mean "confusion", from the verb bilbél. Ancient records in some situations use Babylon as a name for other cities, including cities like Borsippa within Babylon's sphere of influence, and Nineveh for a short period after the Assyrian sack of Babylon.

The present-day site of ancient Babylon consists of a number of mounds covering an area of about 2 by 1 kilometer (1.24 × 0.62 miles) along the Euphrates to the west. Originally, the river roughly bisected the city, but the course of the river has since shifted so that most of the remains of the former western part of the city are now inundated. Some portions of the city wall to the west of the river also remain. Only a small portion of the ancient city (3% of the area within the inner walls; 1.5% of the area within the outer walls; 0.05% at the depth of Middle and Old Babylon) has been excavated.

Known remains include: Kasr—also called Palace or Castle, it is the location of the Neo-Babylonian ziggurat Etemenanki and lies in the center of the site. Amran Ibn Ali; the highest of the mounds at 25 meters, to the south. It is the site of Esagila, a temple of Marduk which also contained shrines to Ea and Nabu. Homera; a reddish colored mound on the west side. Most of the Hellenistic remains are here. Babil; a mound about 22 meters high at the northern end of the site. Its bricks have been subject to looting since ancient times. It held a palace built by Nebuchadnezzar.

Archaeologists have recovered few artifacts predating the Neo-Babylonian period. The water table in the region has risen greatly over the centuries and artifacts from the time before the Neo-Babylonian Empire are unavailable to current standard archaeological methods. Additionally, the Neo-Babylonians conducted significant rebuilding projects in the city, which destroyed or obscured much of the earlier record. Babylon was pillaged numerous times after revolting against foreign rule.

Most notably this occurred in the second millennium at the hands of the Hittites and Elamites, then by the Neo-Assyrian Empire and the Achaemenid Empire in the first millennium. Much of the western half of the city is now beneath the river, and other parts of the site have been mined for commercial building materials. Only the Koldewey expedition recovered artifacts from the Old Babylonian period. These included 967 clay tablets, stored in private houses, with Sumerian literature and lexical documents. Nearby ancient settlements are Kish, Borsippa, Dilbat, and Kutha. Marad and Sippar were 60 kilometers in either direction along the Euphrates.

Most notably this occurred in the second millennium at the hands of the Hittites and Elamites, then by the Neo-Assyrian Empire and the Achaemenid Empire in the first millennium. Much of the western half of the city is now beneath the river, and other parts of the site have been mined for commercial building materials. Only the Koldewey expedition recovered artifacts from the Old Babylonian period. These included 967 clay tablets, stored in private houses, with Sumerian literature and lexical documents. Nearby ancient settlements are Kish, Borsippa, Dilbat, and Kutha. Marad and Sippar were 60 kilometers in either direction along the Euphrates.

Historical knowledge of early Babylon must be pieced together from epigraphic remains found elsewhere, such as at Uruk, Nippur, and Haradum. Information on the Neo-Babylonian city is available from archaeological excavations and from classical sources. Babylon was described, perhaps even visited, by a number of classical historians including Ctesias, Herodotus, Quintus Curtius Rufus, Strabo, and Cleitarchus. These reports are of variable accuracy and some of the content was politically motivated, but these still provide useful information.

References to the city of Babylon can be found in Akkadian and Sumerian literature from the late third millennium B.C. One of the earliest is a tablet describing the Akkadian king Šar-kali-šarri laying the foundations in Babylon of new temples for Annūnı̄tum and Ilaba. Babylon also appears in the administrative records of the Third Dynasty of Ur, which collected in-kind tax payments and appointed an ensi as local governor. The so-called Weidner Chronicle states that Sargon of Akkad (circa 23d century B.C. in the short chronology) had built Babylon "in front of Akkad". A later chronicle states that Sargon "dug up the dirt of the pit of Babylon, and made a counterpart of Babylon next to Akkad".

Van de Mieroop has suggested that those sources may refer to the much later Assyrian king Sargon II of the Neo-Assyrian Empire rather than Sargon of Akkad. The Book of Genesis, chapter 10, claims that king Nimrod founded Babel, Uruk, and Akkad. Ctesias, quoted by Diodorus Siculus and in George Syncellus's Chronographia, claimed to have access to manuscripts from Babylonian archives, which date the founding of Babylon to 2286 B.C., under the reign of its first king, Belus. A similar figure is found in the writings of Berossus, who according to Pliny, stated that astronomical observations commenced at Babylon 490 years before the Greek era of Phoroneus, indicating 2243 B.C.

Stephanus of Byzantium wrote that Babylon was built 1002 years before the date given by Hellanicus of Lesbos for the siege of Troy (1229 B.C.), which would date Babylon's foundation to 2231 B.C. All of these dates place Babylon's foundation in the 23rd century B.C.; however, cuneiform records have not been found to correspond with these classical (post-cuneiform) accounts. It is known that by around the 19th century B.C., much of southern Mesopotamia was occupied by Amorites, nomadic tribes from the northern Levant who were Northwest Semitic speakers, unlike the native Akkadians of southern Mesopotamia and Assyria, who spoke East Semitic.

Stephanus of Byzantium wrote that Babylon was built 1002 years before the date given by Hellanicus of Lesbos for the siege of Troy (1229 B.C.), which would date Babylon's foundation to 2231 B.C. All of these dates place Babylon's foundation in the 23rd century B.C.; however, cuneiform records have not been found to correspond with these classical (post-cuneiform) accounts. It is known that by around the 19th century B.C., much of southern Mesopotamia was occupied by Amorites, nomadic tribes from the northern Levant who were Northwest Semitic speakers, unlike the native Akkadians of southern Mesopotamia and Assyria, who spoke East Semitic.

The Amorites at first did not practice agriculture like more advanced Mesopotamians, preferring a semi-nomadic lifestyle, herding sheep. Over time, Amorite grain merchants rose to prominence and established their own independent dynasties in several south Mesopotamian city-states, most notably Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, Lagash, and later, founding Babylon as a state. According to a Babylonian date list, Amorite[a] rule in Babylon began (circa 19th or 18th century B.C.) with a chieftain named Sumu-abum, who declared independence from the neighboring city-state of Kazallu.

Sumu-la-El, whose dates may be concurrent with those of Sumu-abum, is usually given as the progenitor of the First Babylonian Dynasty. Both are credited with building the walls of Babylon. In any case, the records describe Sumu-la-El’s military successes establishing a regional sphere of influence for Babylon. Babylon was initially a minor city-state, and controlled little surrounding territory; its first four Amorite rulers did not assume the title of king. The older and more powerful states of Assyria, Elam, Isin and Larsa overshadowed Babylon until it became the capital of Hammurabi's short lived empire about a century later.

Hammurabi (reigned 1792–1750 B.C.) is famous for codifying the laws of Babylonia into the Code of Hammurabi. He conquered all of the cities and city states of southern Mesopotamia, including Isin, Larsa, Ur, Uruk, Nippur, Lagash, Eridu, Kish, Adab, Eshnunna, Akshak, Akkad, Shuruppak, Bad-tibira, Sippar and Girsu, coalescing them into one kingdom, ruled from Babylon. Hammurabi also invaded and conquered Elam to the east, and the kingdoms of Mari and Ebla to the north west.

After a protracted struggle with the powerful Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan of the Old Assyrian Empire, he forced his successor to pay tribute late in his reign, spreading Babylonian power to Assyria's Hattian and Hurrian colonies in Asia Minor. After the reign of Hammurabi, the whole of southern Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia, whereas the north had already coalesced centuries before into Assyria. From this time, Babylon supplanted Nippur and Eridu as the major religious centers of southern Mesopotamia.

After a protracted struggle with the powerful Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan of the Old Assyrian Empire, he forced his successor to pay tribute late in his reign, spreading Babylonian power to Assyria's Hattian and Hurrian colonies in Asia Minor. After the reign of Hammurabi, the whole of southern Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia, whereas the north had already coalesced centuries before into Assyria. From this time, Babylon supplanted Nippur and Eridu as the major religious centers of southern Mesopotamia.

Hammurabi's empire destabilized after his death. Assyrians defeated and drove out the Babylonians and Amorites. The far south of Mesopotamia broke away, forming the native Sealand Dynasty, and the Elamites appropriated territory in eastern Mesopotamia. The Amorite dynasty remained in power in Babylon, which again became a small city state. Texts from Old Babylon often include references to Shamash, the sun-god of Sippar, treated as a supreme deity, and Marduk, considered as his son. Marduk was later elevated to a higher status and Shamash lowered, perhaps reflecting Babylon’s rising political power.

In 1595 B.C. the city was overthrown by the Hittite Empire from Asia Minor. Thereafter, Kassites from the Zagros Mountains of north western Ancient Iran captured Babylon, ushering in a dynasty that lasted for 435 years, until 1160 B.C. The city was renamed Karanduniash during this period. Kassite Babylon eventually became subject to the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1053 B.C.) to the north, and Elam to the east, with both powers vying for control of the city. The Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I took the throne of Babylon in 1235 B.C.

By 1155 B.C., after continued attacks and annexing of territory by the Assyrians and Elamites, the Kassites were deposed in Babylon. An Akkadian south Mesopotamian dynasty then ruled for the first time. However, Babylon remained weak and subject to domination by Assyria. Its ineffectual native kings were unable to prevent new waves of foreign West Semitic settlers from the deserts of the Levant, including the Arameans and Suteans in the 11th century B.C., and finally the Chaldeans in the 9th century B.C., entering and appropriating areas of Babylonia for themselves. The Arameans briefly ruled in Babylon during the late 11th century B.C.

During the rule of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 B.C.), Babylonia was under constant Assyrian domination or direct control. During the reign of Sennacherib of Assyria, Babylonia was in a constant state of revolt, led by a chieftain named Merodach-Baladan, in alliance with the Elamites, and suppressed only by the complete destruction of the city of Babylon. In 689 B.C., its walls, temples and palaces were razed, and the rubble was thrown into the Arakhtu, the sea bordering the earlier Babylon on the south. Destruction of the religious center shocked many, and the subsequent murder of Sennacherib by two of his own sons while praying to the god Nisroch was considered an act of atonement.

During the rule of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 B.C.), Babylonia was under constant Assyrian domination or direct control. During the reign of Sennacherib of Assyria, Babylonia was in a constant state of revolt, led by a chieftain named Merodach-Baladan, in alliance with the Elamites, and suppressed only by the complete destruction of the city of Babylon. In 689 B.C., its walls, temples and palaces were razed, and the rubble was thrown into the Arakhtu, the sea bordering the earlier Babylon on the south. Destruction of the religious center shocked many, and the subsequent murder of Sennacherib by two of his own sons while praying to the god Nisroch was considered an act of atonement.

Consequently, his successor Esarhaddon hastened to rebuild the old city and make it his residence during part of the year. After his death, Babylonia was governed by his elder son, the Assyrian prince Shamash-shum-ukin, who eventually started a civil war in 652 B.C. against his own brother, Ashurbanipal, who ruled in Nineveh. Shamash-shum-ukin enlisted the help of other peoples subject to Assyria, including Elam, Persia, Chaldeans and Suteans of southern Mesopotamia, and the Canaanites and Arabs dwelling in the deserts south of Mesopotamia. Once again, Babylon was besieged by the Assyrians, starved into surrender and its allies were defeated.

Ashurbanipal celebrated a "service of reconciliation", but did not venture to "take the hands" of Bel. An Assyrian governor named Kandalanu was appointed as ruler of the city. Ashurbanipal did collect texts from Babylon for inclusion in his extensive library at Ninevah. After the death of Ashurbanipal, the Assyrian empire destabilized due to a series of internal civil wars throughout the reigns of Assyrian kings Ashur-etil-ilani, Sin-shumu-lishir and Sinsharishkun. Eventually Babylon, like many other parts of the near east, took advantage of the anarchy within Assyria to free itself from Assyrian rule.

In the subsequent overthrow of the Assyrian Empire by an alliance of peoples, the Babylonians saw another example of divine vengeance. Under Nabopolassar, a previously unknown Chaldean chieftain, Babylon escaped Assyrian rule, and in an alliance with Cyaxares, king of the Medes and Persians together with the Scythians and Cimmerians, finally destroyed the Assyrian Empire between 612 B.C. and 605 B.C. Babylon thus became the capital of the Neo-Babylonian (sometimes and possibly erroneously called the Chaldean) Empire. With the recovery of Babylonian independence, a new era of architectural activity ensued, particularly during the reign of his son Nebuchadnezzar II (604–561 B.C.).

Nebuchadnezzar ordered the complete reconstruction of the imperial grounds, including the Etemenanki ziggurat, and the construction of the Ishtar Gate—the most prominent of eight gates around Babylon. A reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate is located in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon—one of the seven wonders of the ancient world—said to have been built for his homesick wife Amyitis. Whether the gardens actually existed is a matter of dispute. German archaeologist Robert Koldewey speculated that he had discovered its foundations, but many historians disagree about the location.

Stephanie Dalley has argued that the hanging gardens were actually located in the Assyrian capital, Nineveh. Nebuchandnezzar is also notoriously associated with the Babylonian exile of the Jews, the result of an imperial technique of pacification, used also by the Assyrians, in which ethnic groups in conquered areas were deported en masse to the capital. Chaldean rule of Babylon did not last long; it is not clear whether Neriglissar and Labashi-Marduk were Chaldeans or native Babylonians, and the last ruler Nabonidus (556–539 B.C.) and his co-regent son Belshazzar were Assyrians from Harran.

In 539 B.C., the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell to Cyrus the Great, king of Persia, with a military engagement known as the Battle of Opis. Babylon's walls were considered impenetrable. The only way into the city was through one of its many gates or through the Euphrates River. Metal grates were installed underwater, allowing the river to flow through the city walls while preventing intrusion. The Persians devised a plan to enter the city via the river. During a Babylonian national feast, Cyrus' troops diverted the Euphrates River upstream, allowing Cyrus' soldiers to enter the city through the lowered water.

The Persian army conquered the outlying areas of the city while the majority of Babylonians at the city center were unaware of the breach. The account was elaborated upon by Herodotus, and is also mentioned in parts of the Hebrew Bible. Herodotus also described a moat, an enormously tall and broad wall cemented with bitumen and with buildings on top, and a hundred gates to the city. He also writes that the Babylonians wear turbans and perfume and bury their dead in honey, that they practice ritual prostitution, and that three tribes among them eat nothing but fish. The hundred gates can be considered a reference to Homer.

Following the pronouncement of Archibald Henry Sayce in 1883, Herodotus’s account of Babylon has largely been considered to represent Greek folklore rather than an authentic voyage to Babylon. Dalley and others have recently suggested taking Herodotus’s account seriously again. According to 2 Chronicles 36 of the Hebrew Bible, Cyrus later issued a decree permitting captive people, including the Jews, to return to their own lands. Text found on the Cyrus Cylinder has traditionally been seen by biblical scholars as corroborative evidence of this policy, although the interpretation is disputed because the text only identifies Mesopotamian sanctuaries but makes no mention of Jews, Jerusalem, or Judea.

Under Cyrus and the subsequent Persian king Darius I, Babylon became the capital city of the 9th Satrapy (Babylonia in the south and Athura in the north), as well as a center of learning and scientific advancement. In Achaemenid Persia, the ancient Babylonian arts of astronomy and mathematics were revitalized, and Babylonian scholars completed maps of constellations. The city became the administrative capital of the Persian Empire and remained prominent for over two centuries. Many important archaeological discoveries have been made that can provide a better understanding of that era.

The early Persian kings had attempted to maintain the religious ceremonies of Marduk, but by the reign of Darius III, over-taxation and the strain of numerous wars led to a deterioration of Babylon's main shrines and canals, and the destabilization of the surrounding region. There were numerous attempts at rebellion and in 522 B.C. (Nebuchadnezzar III), 521 B.C. (Nebuchadnezzar IV) and 482 B.C. (Bel-shimani and Shamash-eriba) native Babylonian kings briefly regained independence. However these revolts were quickly repressed and Babylon remained under Persian rule for two centuries, until Alexander the Great's entry in 331 B.C.

In October of 331 B.C., Darius III, the last Achaemenid king of the Persian Empire, was defeated by the forces of the Ancient Macedonian Greek ruler Alexander the Great at the Battle of Gaugamela. A native account of this invasion notes a ruling by Alexander not to enter the homes of its inhabitants. Under Alexander, Babylon again flourished as a center of learning and commerce. However, following Alexander's death in 323 B.C. in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, his empire was divided amongst his generals, the Diadochi, and decades of fighting soon began. The constant turmoil virtually emptied the city of Babylon.

A tablet dated 275 B.C. states that the inhabitants of Babylon were transported to Seleucia, where a palace and a temple (Esagila) were built. With this deportation, Babylon became insignificant as a city, although more than a century later, sacrifices were still performed in its old sanctuary. Under the Parthian and Sassanid Empires, Babylon (like Assyria) became a province of these Persian Empires for nine centuries, until after A.D. 650. It maintained its own culture and people, who spoke varieties of Aramaic, and who continued to refer to their homeland as Babylon.

Examples of their culture are found in the Babylonian Talmud, the Gnostic Mandaean religion, Eastern Rite Christianity and the religion of the prophet Mani. Christianity was introduced to Mesopotamia in the 1st and 2nd centuries A.D., and Babylon was the seat of a Bishop of the Church of the East until well after the Arab/Islamic conquest. In the mid-7th century, Mesopotamia was invaded and settled by the expanding Muslim Empire, and a period of Islamization followed. Babylon was dissolved as a province and Aramaic and Church of the East Christianity eventually became marginalized.

Ibn Hauqal mentions a small village called Babel in the tenth century; subsequent travelers describe only ruins. Babylon is mentioned in medieval Arabic writings as a source of bricks, said to have been used in cities from Baghdad to Basra. European travelers in many cases could not discover the city's location, or mistook Fallujah for it. Twelfth-century traveler Benjamin of Tudela mentions Babylon but it’s not clear if he really went there. Others referred to Baghdad as Babylon or New Babylon and described various structures encountered in the region as the Tower of Babel. Pietro della Valle found the ancient site in the seventeenth century and noted the existence of both baked and dried mudbricks cemented with bitumen[Wikipedia].

Ancient Babylonians of Mesopotamia: The Babylonians began their rise to power in the region of Mesopotamia around 1900 BC. This was at a time when Mesopotamia was largely unstable, prone to conflict and invasion, and not at all unified. Known as the Old Babylonian Period this early period was characterized by over 300 years of rule of the Amorites. The Amorites had come from west of the Euphrates River. They formed an empire based in the city-state of Babylon. The empire was a monarchy. It had conquered the outer Amorite territories and united them into one kingdom. The Babylonian Empire thrived on an economy of trade with the city-states west of the Euphrates. Under the strict rule of Hammurabi sometime around 1750 BC the city of Babylon became the political and religious capital of the entire empire. King Hammurabi ran a tight ship, with his famous code of laws providing a steady environment where taxes were collected and affairs were run quite efficiently.

Babylonia was quite successful at taking control of nearby city-states. This was due in large part to their strong and disciplined army. Babylon’s influence was felt far and wide, as far away as the eastern Mediterranean regions. This phase of the Babylonian empire ended after a century and a half of thriving economy and cultural stimulus. This occurred when the city of Babylon fell to the Hittites in 1595 BC. Though Babylon was invaded by Hittite forces led by King Mursilis I, it remained capital of the foreign-led empire that replaced the former glory of the Babylonians. Succeeding the Hittites, the Kassites of Iran took over and renamed the city Kar-Duniash. For nearly 600 years this faction ruled over the western parts of Asia. Babylon was considered its holy city during this time known as the Kassite Period. Elsewhere in Mesopotamia the Assyrians continued to dominate.

There was a relatively peaceful coexistence between the Assyrians and Babylonians. Essentially the Assyrians gave Babylonia the latitude to enjoy quite a bit of power. When Babylonia felt its power and privileges were being strangled, they often attempted to rebel against Assyrian rule. When the last Assyrian king Ashurbanipal died in 627 BC, under the influence of Nabopolassar the Chaldean the Babylonians finally succeeded in a rebellion. The Assyrian city of Nineveh was taken in 612 BC., and Babylonia was gain in control of the entire region.

It was the nearly half-century rule of Nabopolassar’s son Nebudchadnezzar that again cemented Babylon as the center of the substantial Babylonian empire. This period of Babylonian history was known as the Chaldean Era of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. In 539 BC Persian king Cyrus mounted an invasion against the Babylonians. One of his first acts as the self-proclaimed successor of the Babylonian kings was to let the exiled Jews return to their homeland. Cyrus transferred power to his son Cambyses in 529 BC and died the following year. Immediately after Darius the Great seized power in Persia Babylonia briefly recovered its independence. Babylon was thus briefly under a native ruler, Nidinta-Bel, who took the name of Nebuchadnezzar III.

During this period Assyria to the north also rebelled. Nidinta-Bel/Nebuchadnezzar III purportedly reigned from October 521 to August 520 BC, when Darius’s Persian Achaemenid Empire retook Babylon by storm. A few years later in 514 BC Babylon again revolted and declared independence under the Armenian King Arakha. On this occasion after its recapture by the Persians, the walls of the city were partly destroyed. The Babylonian Kingdom effectively came to an end and the city fell into ruin. E-Saggila the great temple of Bel however still continued to be maintained and was a center of Babylonian patriotism [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Gilgamesh is the semi-mythic King of Uruk best known from The Epic of Gilgamesh (written circa 2150-1400 B.C.) the great Sumerian/Babylonian poetic work which pre-dates Homer’s writing by 1500 years and, therefore, stands as the oldest piece of epic Western literature. Gilgamesh’s father was the Priest-King Lugalbanda (who is featured in two poems concerning his magical abilities which pre-date Gilgamesh) and his mother the goddess Ninsun (the Holy Mother and Great Queen) and, accordingly, Gilgamesh was a demi-god who was said to have lived an exceptionally long life (the Sumerian King List records his reign as 126 years) and to be possessed of super-human strength.

Known as 'Bilgames’ in the Sumerian, 'Gilgamos’ in Greek, and associated closely with the figure of Dumuzi from the Sumerian poem The Descent of Inanna, Gilgamesh is widely accepted as the historical fifth king of Uruk whose influence was so profound that myths of his divine status grew up around his deeds and finally culminated in the tales found in The Epic of Gilgamesh. In the Sumerian tale of Inanna and the Huluppu Tree, in which the goddess Inanna plants a troublesome tree in her garden and appeals to her family for help with it, Gilgamesh appears as her loyal brother who comes to her aid.

In this story, Inanna (the goddess of love and war and one of the most powerful and popular of Mesopotamian deities) plants a tree in her garden with the hope of one day making a chair and bed from it. The tree becomes infested, however, by a snake at its roots, a female demon (lilitu) in its center, and an Anzu bird in its branches. No matter what, Inanna cannot rid herself of the pests and so appeals to her brother, Utu, god of the sun, for help. Utu refuses but her plea is heard by Gilgamesh who comes, heavily armed, and kills the snake.

The demon and Anzu bird then flee and Gilgamesh, after taking the branches for himself, presents the trunk to Inanna to build her bed and chair from. This is thought to be the first appearance of Gilgamesh in heroic poetry and the fact that he rescues a powerful and potent goddess from a difficult situation shows the high regard in which he was held even early on. The historical king was eventually accorded completely divine status as a god. He was seen as the brother of Inanna, one of the most popular goddesses, if not the most popular, in all of Mesopotamia.

Prayers found inscribed on clay tablets address Gilgamesh in the afterlife as a judge in the Underworld comparable in wisdom to the famous Greek judges of the Underworld, Rhadamanthus, Minos, and Aeacus. In "The Epic of Gilgamesh", the great king is thought to be too proud and arrogant by the gods and so they decide to teach him a lesson by sending the wild man, Enkidu, to humble him. Enkidu and Gilgamesh, after a fierce battle in which neither are bested, become friends and embark on adventures together. When Enkidu is struck with death, Gilgamesh falls into a deep grief.

Recognizing his own mortality through the death of his friend, questions the meaning of life and the value of human accomplishment in the face of ultimate extinction. Casting away all of his old vanity and pride, Gilgamesh sets out on a quest to find the meaning of life and, finally, some way of defeating death. In doing so, he becomes the first epic hero in world literature. The grief of Gilgamesh, and the questions his friend's death evoke, resonate with every human being who has wrestled with the meaning of life in the face of death. Although Gilgamesh ultimately fails to win immortality in the story, his deeds live on through the written word and, so, does he.

Since "The Epic of Gilgamesh" existed in oral form long before it was written down, there has been much debate over whether the extant tale is more early Sumerian or later Babylonian in cultural influence. The best-preserved version of the story comes from the Babylonian writer Shin-Leqi-Unninni (wrote 1300-1000 B.C.) who translated, edited, and may have embellished the original story. Regarding this, the Sumerian scholar Samuel Noah Kramer writes:

"Of the various episodes comprising The Epic of Gilgamesh, several go back to Sumerian prototypes actually involving the hero Gilgamesh. Even in those episodes which lack Sumerian counterparts, most of the individual motifs reflect Sumerian mythic and epic sources. In no case, however, did the Babylonian poets slavishly copy the Sumerian material. They so modified its content and molded its form, in accordance with their own temper and heritage, that only the bare nucleus of the Sumerian original remains recognizable. As for the plot structure of the epic as a whole - the forceful and fateful episodic drama of the restless, adventurous hero and his inevitable disillusionment - it is definitely a Babylonian, rather than a Sumerian, development and achievement."

Historical evidence for Gilgamesh’s existence is found in inscriptions crediting him with the building of the great walls of Uruk (modern day Warka, Iraq) which, in the story, are the tablets upon which he first records his great deeds and his quest for the meaning of life. There are other references to him by known historical figures of his time (26th century B.C.) such as King Enmebaragesi of Kish and, of course, the Sumerian King List and the legends which grew up around his reign.

In the present day, Gilgamesh is still spoken of and written about. A German team of Archaeologists claim to have discovered the Tomb of Gilgamesh in April of 2003 CE. Archaeological excavations, conducted through modern technology involving magnetization in and around the old riverbed of the Euphrates, have revealed garden enclosures, specific buildings, and structures described in The Epic of Gilgamesh including the great king’s tomb. According to legend, Gilgamesh was buried at the bottom of the Euphrates when the waters parted upon his death [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Babylonian Trigonometry: A 3,700-year-old cuneiform tablet housed at Columbia University is inscribed with the world’s oldest and most accurate working trigonometric table, according to a report in The Guardian. Early twentieth-century scholars noted the Pythagorean triples on the tablet, but did not know how the numbers were used. Mathematicians Daniel Mansfield and Norman Wildberger of the University of New South Wales say the calculations on Plimpton 322, as the Babylonian tablet is known, describe the shapes of right triangles based on ratios, whereas modern trigonometric tables are based upon measurements of angles and circles.

Babylonian mathematicians used base 60 for their calculations, rather than base 10, which allowed for more accurate fractions. In addition, Mansfield and Wildberger explained that Plimpton 322 includes four columns and 15 rows of numbers, for a sequence of 15 right triangles decreasing in inclination. Based upon the mathematics, however, the broken table probably originally had six columns and 38 rows of numbers. The researchers think the large numbers on the table could have been used to survey land and calculate how to construct temples, palaces, and step pyramids [Archaeological Institute of America].

Present Day Babylon: Many challenges face the 4,000-year-old city of Babylon. Archaeologists agree that restoration work under Saddam Hussein in the 1980s inflicted damage on the ancient remains and continues to cause problems. The dictator began to build a replica of the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II on top of its ruins, and then, after the Gulf War, added a modern palace adjacent to it. In 2003, U.S. troops occupied the new palace. Visitors can see the basketball hoop they installed inside its walls. Concertina wire that was left behind has been reused to keep tourists away from a 2,500-year-old lion statue. An oil pipeline now runs through the eastern part of the site. “It goes through the outer wall of Babylon,” said tour guide Hussein Al-Ammari. Only two percent of Babylon has been excavated, but local development continues to encroach on the site [Archaeological Institute of America].

The Babylonian Goddess Ereshkigal: In Mesopotamian mythology, Ereshkigal ("Queen of the Great Earth") was the goddess of Kur, the land of the dead or underworld in Sumerian mythology. In later East Semitic myths she was said to rule Irkalla alongside her husband Nergal. Sometimes her name is given as Irkalla, similar to the way the name Hades was used in Greek mythology for both the underworld and its ruler, and sometimes it is given as Ninkigal ("Great Lady of the Earth" or "Lady of the Great Earth"). In Sumerian myths, Ereshkigal was the only one who could pass judgment and give laws in her kingdom. The main temple dedicated to her was located in Kutha.

In the ancient Sumerian poem Inanna's Descent to the Underworld Ereshkigal is described as Inanna's older sister. The two main myths involving Ereshkigal are the story of Inanna's descent into the Underworld and the story of Ereshkigal's marriage to the god Nergal. In ancient Sumerian mythology, Ereshkigal is the queen of the Underworld. She is the older sister of the goddess, Inanna. Inanna and Ereshkigal represent polar opposites. Inanna is the Queen of Heaven, but Ereshkigal is the queen of Irkalla. Ereshkigal plays a very prominent and important role in two particular myths.

The first myth featuring Ereshkigal is described in the ancient Sumerian epic poem of "Inanna's Descent to the Underworld." In the poem, the goddess, Inanna descends into the Underworld, apparently seeking to extend her powers there. Ereshkigal is described as being Inanna's older sister. When Neti, the gatekeeper of the Underworld, informs Ereshkigal that Inanna is at the gates of the Underworld, demanding to be let in, Ereshkigal responds by ordering Neti to bolt the seven gates of the Underworld and to open each gate separately, but only after Inanna has removed one article of clothing.

Inanna proceeds through each gate, removing one article of clothing at each gate. Finally, once she has gone through all seven gates she finds herself naked and powerless, standing before the throne of Ereshkigal. The seven judges of the Underworld judge Inanna and declare her to be guilty. Inanna is struck dead and her dead corpse is hung on a hook in the Underworld for everyone to see. Inanna's minister, Ninshubur, however, pleads with Enki and Enki agrees to rescue Inanna from the Underworld.

Enki sends two sexless beings down to the Underworld to revive Inanna with the food and water of life. The sexless beings escort Inanna up from the Underworld, but a horde of angry demons follow Inanna back up from the Underworld, demanding to take someone else down to the Underworld as Inanna's replacement. When Inanna discovers that her husband, Dumuzid, has not mourned her death, she becomes ireful towards him and orders the demons to take Dumuzid as her replacement.

The other myth is the story of Nergal, the plague god. Once, the gods held a banquet that Ereshkigal, as queen of the Underworld, could not come up to attend. They invited her to send a messenger, and she sent her vizier Namtar in her place. He was treated well by all, but for the exception of being disrespected by Nergal. As a result of this, Nergal was banished to the kingdom controlled by the goddess. Versions vary at this point, but all of them result in him becoming her husband. In later tradition, Nergal is said to have been the victor, taking her as wife and ruling the land himself.

It is theorized that the story of Inanna's descent is told to illustrate the possibility of an escape from the Underworld, while the Nergal myth is intended to reconcile the existence of two rulers of the Underworld: a goddess and a god. The addition of Nergal represents the harmonizing tendency to unite Ereshkigal as the queen of the Underworld with the god who, as god of war and of pestilence, brings death to the living and thus becomes the one who presides over the dead. In some versions of the myths, Ereshkigal rules the Underworld by herself, but in other versions of the myths, Ereshkigal rules alongside a husband subordinate to her named Gugalana.

In his book, "Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.", the renowned scholar of ancient Sumer, Samuel Noah Kramer writes that, according to the introductory passage of the ancient Sumerian epic poem, "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld," Ereshkigal was forcibly abducted, taken down to the Underworld by the Kur, and was forced to become queen of the Underworld against her will. In order to avenge the abduction of Ereshkigal, Enki, the god of water, set out in a boat to slay the Kur.

The Kur defends itself by pelting Enki with rocks of many sizes and by sending the waves beneath Enki's boat to attack Enki. The poem never actually explains who the ultimate victor of the battle is, but it is implied that Enki wins. Samuel Noah Kramer relates this myth to the ancient Greek myth of the rape of Persephone, asserting that the Greek story is probably derived from the ancient Sumerian story. In Sumerian mythology, Ereshkigal is the mother of the goddess Nungal. Her son with Enlil is the god Namtar. With Gugalana, her son is Ninazu.

In later times, the Greeks and Romans appear to have syncretized Ereshkigal with their own goddess Hecate. In the heading of a spell in the Michigan Magical Papyrus, which has been dated to the late third or early fourth century A.D., Hecate is referred to as "Hecate Ereschkigal" and is invoked using magical words and gestures to alleviate the caster's fear of punishment in the afterlife [Wikipedia].

The Babylonian Goddess Ereshkigal: Ereshkigal (also known as Irkalla and Allatu) is the Mesopotamian Queen of the Dead who rules the underworld. Her name translates as "Queen of the Great Below" or "Lady of the Great Place". The word 'great' should be understood as 'vast,' not 'exceptional' and referred to the land of the dead which was thought to lie beneath the Mountains of Sunset to the west and was known as Kurnugia ('the Land of No Return'). Kurnugia was an immense realm of gloom under the earth, where the souls of the dead drank from muddy puddles and ate dust.

Ereshkigal ruled over these souls from her palace Ganzir, located at the entrance to the underworld, and guarded by seven gates which were kept by her faithful servant Neti. She ruled her realm alone until the war god Nergal (also known as Erra) became her consort and co-ruler for six months of the year. Erishkigal is the older sister of the goddess Inanna and best known for the part she plays in the famous Sumerian poem The Descent of Inanna (circa 1900-1600 B.C.).

Her first husband (and father of the god Ninazu) was the Great Bull of Heaven, Gugalana, who was killed by the hero Enkidu in The Epic of Gilgamesh. Her second husband (or consort) was the god Enlil with whom she bore a son, Namtar, and by another consort her daughter Nungal (also known as Manungal) was conceived, an underworld deity who punished the wicked and was associated with healing and retribution. Her fourth consort was Nergal, the only mate who agreed to remain with her in the realm of the dead.

There is no known iconography for Ereshkigal or, at least, none universally agreed on. "The Burney Relief" (also known as "The Queen of the Night", dating from Hammurabi's reign of 1792-1750 B.C.) is often interpreted as representing Ereshkigal. The terracotta relief depicts a naked woman with downward-pointing wings standing on the backs of two lions and flanked by owls. She holds symbols of power and, beneath the lions, are images of mountains. This iconography strongly suggests a depiction of Ereshkigal but scholars have also interpreted the work as honoring Inanna or the demon Lilith.

Although the relief most likely does depict Ereshkigal, and there are other similar reliefs of this same figure with varying details, it would not be surprising to find few images of her in art. Ereshkigal was the most feared deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon because she represented one's final destination from which there was no returning. In Mesopotamian belief, to create an image of someone or something was to invite the attention of the subject. Statues of the gods were thought to house the gods themselves, for example, and images on people's cylinder seals were thought to have amuletic properties.

A statue or image of Ereshkigal, then, would have directed the attention of the Queen of the Dead to the creator or owner, and this was far from desirable. Ereshkigal is first mentioned in the Sumerian poem The Death of Ur-Nammu which dates to the reign of Shulgi of Ur (2029-1982 B.C.). She was undoubtedly known earlier, however, and most likely during the time of the Akkadian Empire (2334-2218 B.C.). Her Akkadian name, Allatu, may be referenced on fragments predating Shulgi's reign. By the time of the Old Babylonian Period (circa 2000-1600 B.C.) Ereshkigal was widely recognized as the Queen of the Dead, lending support to the claim that the Queen of the Night relief from Hammurabi's reign depicts her.

Although goddesses lost their status later in Mesopotamian history, early evidence clearly shows the most powerful deities were once female. Inanna (later Ishtar of the Assyrians) was among the most popular deities and may have inspired similar goddesses in many other cultures including Sauska of the Hittites, Astarte of the Phoenicians, Aphrodite of the Greeks, Venus of the Romans, and perhaps even Isis of the Egyptians. The underworld in all these other cultures was ruled by a god, however, and Ereshkigal is unique in being the only female deity to hold this position even after gods supplanted goddesses and Nergal was given to her as consort.

Although Ereshkigal was feared, she was also greatly respected. The Descent of Inanna has been widely - and wrongly - interpreted in the modern day as a symbolic journey of a woman becoming her 'true self.' Written works may be interpreted in any reasonable way only insofar as that interpretation can be supported by the text. The Descent of Inanna certainly lends itself to a Jungian interpretation of a journey to wholeness by confronting one's darker half, but this would not have been the original meaning of the poem nor is that interpretation supported by the work itself. Far from praising Inanna, or presenting her as some heroic archetype, the poem shows her as selfish and self-serving and, further, ends with praise for Ereshkigal, not Inanna.

Inanna/Ishtar is frequently depicted in Mesopotamian literature as a woman who largely thinks only of herself and her own desires, often at the expense of others. In The Epic of Gilgamesh, her sexual advances are spurned by the hero and so she sends her sister's husband, Gugulana, The Bull of Heaven, to destroy Gilgamesh's realm. After hundreds of people are killed by the bull's rampage, it is killed by Enkidu, the friend and comrade-in-arms of Gilgamesh. Enkidu is condemned by the gods for killing a deity and sentenced to die; the event which then sends Gilgamesh on his quest for immortality. In the Gilgamesh story, Inanna/Ishtar only thinks of herself and the same is true in The Descent of Inanna.

The work begins by stating how Inanna chooses to travel to the underworld to attend Gugulana's funeral - a death she brought about - and details how she is treated when she arrives. Ereshkigal is not happy to hear her sister is at the gates and instructs Neti to make her remove various articles of clothing and ornaments at each of the seven gates before admitting her to the throne room. By the time Inanna stands before Ereshkigal she is naked, and after the Annuna of the Dead pass judgment against her, Ereshkigal kills her sister and hangs her corpse on the wall.

It is only through Inanna's cleverness in previously instructing her servant Ninshubur what to do, and Ninshubur's ability to persuade the gods in favor of her mistress, that Inanna is resurrected. Even so, Inanna's consort Dumuzi and his sister (agricultural dying and reviving deities) then need to take her place in the underworld because it is the land of no return and no soul can come back without finding a replacement. The main character of the piece is not Inanna but Ereshkigal. The queen acts on the judgment of her advisors, the Annuna, who recognize that Inanna is guilty of causing Gugulana's death.

The text reads: "The annuna, the judges of the underworld, surrounded her. They passed judgment against her. Then Ereshkigal fastened on Inanna the eye of death. She spoke against her the word of wrath. She uttered against her the cry of guilt. She struck her. Inanna was turned into a corpse. A piece of rotting meat. And was hung from a hook on the wall."

Inanna is judged and executed for her crime, but she has obviously foreseen this possibility and left instructions with her servant Ninshubur. After three days and three nights waiting for Inanna, Ninshubur follows the commands of the goddess, goes to Inanna’s father-god Enki for help, and receives two galla (androgynous demons) to help her in returning Inanna to the earth. The galla enter the underworld "like flies" and, following Enki’s specific instructions, attach themselves closely to Ereshkigal. The Queen of the Dead is seen in distress: "No linen was spread over her body. Her breasts were uncovered. Her hair swirled around her head like leeks."

The poem continues to describe the queen experiencing the pains of labor. The galla sympathize with the queen’s pains, and she, in gratitude, offers them whatever gift they ask for. As ordered by Enki, the galla respond, "We wish only the corpse that hangs from the hook on the wall" (Wolkstein and Kramer, 67) and Ereshkigal gives it to them. The galla revive Inanna with the food and water of life, and she rises from the dead. It is at this point, after Inanna leaves and is given back all that Neti took from her at the seven gates, that someone else must be found to take Inanna's place.

Her husband Dumuzi is chosen by Inanna and his sister Geshtinanna volunteers to go with him; Dumuzi will remain in the underworld for six months and Geshtinanna for the other six while Inanna, who caused all the problems in the first place, goes on to do as she pleases. "The Descent of Inanna" would have resonated with an ancient audience in the same way it does today if one understands who the central character actually is. The poem ends with the lines: "Holy Ereshkigal! Great is your renown! Holy Ereshkigal! I sing your praises!"

Ereshkigal is chosen as the main character of the work because of her position as the formidable Queen of the Dead, and the message of the poem relates to injustice: if a goddess as powerful as Ereshkigal can be denied justice and endure the sting then so can anyone reading or hearing the poem recited. Ereshkigal reigns over her kingdom alone until the war god Nergal becomes her consort. In one version of the story, Nergal is seduced by the queen when he visits the underworld, leaves her after seven days of love-making, but then returns to stay with her for six months of the year.

Versions of the story have been found in Egypt (among the Amarna Letters) dating to the 15th century B.C. and at Sultantepe, site of an ancient Assyrian city, dated to the 7th century B.C.; but the best-known version, dating from the Neo-Babylonian Period (circa 626-539 B.C.), has Enki manipulating the events which send Nergal to the underworld as consort to the Queen of the Dead. One day the gods prepared a great banquet to which everyone was invited. Ereshkigal could not attend, however, because she could not leave the underworld and the gods could not descend to hold their banquet there because they would afterwards be unable to leave. The god Enki sent a message to Ereshkigal to send a servant who could bring her back her share of the feast, and she sent her son Namtar.

When Namtar arrived at the gods' banquet hall, they all stood out of respect for his mother except for the war god Nergal. Namtar was insulted and wanted the wrong redressed, but Enki told him to simply return to the underworld and tell his mother what happened. When Ereshkigal hears of the disrespect of Nergal, she tells Namtar to send a message back to Enki demanding that Nergal be sent so she could kill him. The gods confer on this request and recognize its legitimacy and so Nergal is told he must journey to the underworld.

Enki has understood this would happen, of course, and provides Nergal with 14 demon escorts to assist him at each of the seven gates of the underworld. When Nergal arrives, his presence is announced by Neti, and Namtar tells his mother that the god who would not rise has come. Ereshkigal gives orders that he is to be admitted through each of the seven gates which should then be barred behind him and she will kill him when he reaches the throne room. After passing through each gate, however, Nergal posts two of his demon escorts to keep it open and marches to the throne room where he overpowers Namtar and drags Ereshkigal to the floor.

He raises his great axe to cut off her head, but she pleads with him to spare her, promising to be his wife if he agrees and share her power with him. Nergal consents and seems to feel sorry for what he has done. The poem ends with the two kissing and the promise that they will remain together. Since Nergal was often causing problems on earth by losing his temper and causing war and strife, it has been suggested that Enki arranged the entire scenario to get him out of the way. War was recognized as a part of the human experience, however, and so Nergal could not remain in the underworld permanently but had to return to the surface for six months out of the year.

Since he had posted his demon escorts at the gates, had arrived of his own free will, and been invited to stay as consort by the queen, Nergal was able to leave without having to find a replacement. As in "The Descent of Inanna", the symbolism of The Marriage of Ereshkigal and Nergal (either version) touches on the same themes as the Greek story of the Demeter, goddess of nature and bounty, and her daughter Persephone who is abducted by Hades. In the Greek tale, having eaten of the fruit of the dead, Persephone must spend half a year in the underworld with Hades and, during this time, Demeter mourned the loss of her daughter.