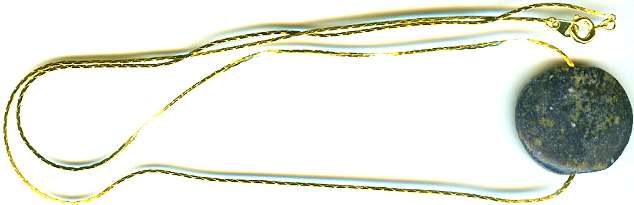

5,000 Year Old 34 Carat Hand-Carved Ancient Assyrian Gold-Flecked Midnight Blue Lapis Lazuli Semi-Precious Gemstone Disc-Shaped Pendant and Chain.

ATTN EBAY!!! DO NOT REMOVE THIS LISTING!!! As per Trust & Safety, this does NOT violate the USA Embargo against SYRIA. This artifact is from present-day ARMENIA, from when Armenia was part of the ASSYRIAN Empire. Please note, though ASSYRIA and SYRIA sound similar, they are NOT the same. Ancient Assyria was an empire which existed from about 3,000 B.C. to 600 B.C., and has NOTHING to do with present day SYRIA. This item does NOT violate eBay policy, and is NOT embargoed. Please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assyria.

CLASSIFICATION: Semi-Precious Lapis Lazuli, Hand-Drilled Suspension Hole (Bow Drill), Hand Shaped Pendant.

ATTRIBUTION: Ancient Assyria (Present-Day Armenia), Approximately 2,900 (3rd Millennium) B.C.

SIZE/DIMENSIONS:

Weight: 34 carats.

Diameter: 25-27 millimeters.

Thickness: 6 millimeters (at center); 2 millimeters (at perimeter).

Chain: Contemporary gold electroplate 60 centimeters (24 inches). A wide variety of other chains are available upon request in sizes from 16 to 30 inches, and in metals ranging from gold and silver electroplate to sterling silver and solid 14kt gold as well as a bronze-toned copper chain. The default chain (absent contrary instructions) is gold electroplate, 24 inches. For a more authentic touch, we also have available high quality (solid, not formed) handcrafted Greek black leather cords.

CONDITION: Exceptional! Completely intact.

DETAIL: A richly colored natural dark blue lapis lazuli semi-precious gemstone which originated from the 7,000 year old mines at Badakhshan in Afghanistan, source of lapis lazuli for the ancient Egyptians, Sumerians, Phoenicians, and the rest of the ancient world, who referred to lapis lazuli as the "gemstone of the heavens", as the golden-flecks of sparkling iron pyrite in the deep blue body was often associated by the ancients with the stars in the heavens. Some of the most splendid ancient jewelry ever unearthed by archaeologists was found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb at Ur in Sumeria dating from the 3rd millennium B.C., and in the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamen's tomb. Lapis Lazuli was one of the most prominent gemstones found within these tombs, including on the famous mask of Tutankhamen.

This beautiful genuine ancient lapis lazuli gemstone pendant was hand-carved about 5,000 years ago! Attributable to the ancient Assyrian culture, pendants such as these were quite common (and quite the fashion statement) during the 3rd and 2nd Millenniums B.C. The round disc shape is somewhat uncommon, not one of the more ordinary shapes usually uncovered. It is much thicker in the center than at the perimeters, resembling an ocean skate or ray. This dark blue specimen possesses glittering highlights of golden iron pyrite inclusions ("fools gold"). Lapis Lazuli was a highly favored semi-precious gemstone in the ancient world; not only in ancient Assyria and Mesopotamia, but as well in the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, and throughout the ancient Mediterranean as well.

Evidence suggests that lapis lazuli has been utilized as a gemstone for at least 10,000 years, making it along with pearls, turquoise, carnelian, and amber, amongst the "oldest" gemstones utilized by ancient cultures for decorative purposes. The ancient Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Phoenician, and Roman cultures all highly favored lapis lazuli. Renaissance artists used ground lapis as pigment for the fabulous blue in the era's masterpieces of art. Still very popular in Eastern Europe, the columns of St. Isaac's Cathedral are lined with lapis, and the Pushkin Palace (both in St. Petersburg) has lapis lazuli paneling over twenty meters (sixty feet) in height! This extraordinary pendant has been mounted onto a twenty-four inch 14kt gold electroplated chain. If you would prefer, we also have available sterling silver and solid 14kt gold chains in lengths from 16 to 30 inches.

HISTORY OF ANCIENT ASSYRIA: Assyrians trace their heritage to an ancient race of the same name, one of the few major factions which appeared after the collapse of the Akkadian Empire; the world's first Semitic empire created under Sargon I. At its peak, the Assyrian empire encompassed what is now western Iran, all of Mesopotamia and Syria, Israel, the Armenian highlands, and even threatened Egypt in the 8th and 7th centuries B.C. The ancient Assyrians were masters of siege warfare, and subdued many other ancient peoples of the region. For these reasons, the ancient pre-Christian Assyrians were greatly feared by other ancient peoples of the region. Eventually however the Assyrians were one of the first nations to adopt Christianity as their state religion almost two thousand years ago.

Assyria proper was located in a mountainous region, extending along the Tigris as far as the high Gordiaean or Carduchian mountain range of Armenia, sometimes called the "Mountains of Ashur". Little is known about the ancient Assyrians prior to the 25th century B.C. The original capital city of ancient Assyria was Ashur, and was originally part of Sargon the Great's Persian Empire (circa 24th century B.C.). Destroyed by barbarians, Assyria ended up being governed as part of the Third Dynasty of Ur, before eventually becoming an independent kingdom about 1900 B.C. The city-state of Ashur had extensive contact with cities on the Anatolian plateau (present-day Turkey). The Assyrians established "merchant colonies" in Cappadocia which were attached to Anatolian cities, but physically separate, and had special tax status. They must have arisen from a long tradition of trade between Ashur and the Anatolian cities. The trade consisted of metal and textiles from Assyria that were traded for precious metals in Anatolia.

The city of Ashur was conquered by the Hammurabi of Babylon, and ceased trading with Anatolia because the goods of Assyria were now being traded with the Babylonians' partners. In the 15th century B.C. the Hurrians of Mitanni sacked Ashur and made Assyria a vassal. Assyria paid tribute to the Mitanni until they collapsed under pressure from the Hittites, when Assyria once again became an independent kingdom in the 14th century B.C., though at times a tributary of the Babylonian kings to the south. As the Hittite empire collapsed from onslaught of the Phrygians, Babylon and Assyria began to compete with one another for the Amorite lands formerly under firm Hittite control. The Assyrians defeated the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar when the forces encountered one another in this region. By 1120 B.C. the Assyrians had advanced as far as the North Sea on one side, the Mediterranean on the other, conquering Phoenicia, and had also subjugated Babylonia as well.

Thereafter for nearly two centuries however the Assyrian's grip over this vast empire steadily weakened centuries until when in 911 B.C. a strong ruler consolidated the Assyrian territories, and his success then embarked on a vast program of merciless expansion. In the mid ninth century B.C. the King of Israel marched in alliance with the Aramaic Kingdom against Assyria, the conflict ending in a deadlock, but a deadlock which presaged a withdrawal of Assyrian forces from the region of the Levant. The following centuries saw a continued decline of Assyria, the only exception being expansion on one front as far as the Caspian Sea. However by the eight century B.C. Assryia had again become strong under Sargon the Tartan, again conquering both Philistine, Israel, Judah, and Samaria.

In 705 BC, Sargon was slain while fighting the Cimmerians and was succeeded by his son who moved the capital to Momrveh. By 670 B.C. Assyria even briefly conquered Egypt, installing Psammetichus as a vassal king in 663 B.C. This proved to be the high water mark for ancient Assyria however. The Assyrian King Ashurbanipal had promoted art and culture and had a vast library of cuneiform tablets at Nineveh, but upon his death in 627 B.C., the Assyrian Empire began to disintegrate rapidly. Babylonia became independent; their king destroyed Nineveh in 612 B.C., and the mighty Assyrian Empire fell and ceased to exist as an independent nation.

LAPIS LAZULI HISTORY: Most lapis lazuli contains iron pyrite in the form of golden flecks sprinkled throughout the gemstone, the hallmark characteristic of lapis lazuli, often compared by ancient populations with stars in the sky. Lapis Lazuli was among the treasures of ancient Mesopotamia, Byzantium, Egypt, Persia, Greece and Rome. Lapis Lazuli gets its name from the Arabic word "allazward", meaning "sky-blue". Along with turquoise and carnelian, the three are undoubtedly amongst the most ancient of gemstones. For more than 7,000 years lapis lazuli has been mined as a gemstone in Afghanistan, near ancient Mesopotamia, and traded throughout the ancient Mediterranean world.

The ancient source of lapis lazuli was these very same mines at Badakhshan (also known as the “Hindu-Kush” mountains), in the Persian highlands above the fertile Mesopotamian lowlands. The Persian highlands and plateau provided many of the raw materials lacking in the ancient civilizations abounding in the Mesopotamian lowlands (the "fertile crescent"). Records indicate that the Sumerian city of Ur imported lapis lazuli from the mines at Badakhshan as early as 4,000 B.C. In fact, the ancient royal Sumerian tombs of Ur, located near the Euphrates River in lower Iraq, contained more than 6,000 beautifully executed lapis lazuli statuettes of birds, deer, and rodents as well as dishes, beads, and cylinder seals.

Most ancient jewelry typically used one or more of three gemstones (carnelian, turquoise), and lapis lazuli was certainly very popular. How popular? One of the richest examples of ancient jewelry is Queen Pu-abi's tomb at Ur in Sumeria dating from the 3rd millennium B.C. In the crypt the queen was covered with a robe of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, agate, and chalcedony beads. The lower edge of the robe was decorated with a fringed border of small gold, carnelian, and lapis lazuli cylinders. Near her right arm were three long gold pins with lapis lazuli heads, and three amulets in the shape of fish. Two of the fish amulets were made of gold and the third, you guessed it, lapis lazuli. On the queen's head were three diadems each featuring lapis lazuli.

At roughly the same point in time as Queen Pu-abi’s reign in Ur, lapis lazuli was also certainly popular in 3,100 B.C. with the Egyptians who used it in medicines, pigments (ultramarine), cosmetics (eye-shadow), carved into seals, and of course, in jewelry. The famous mask covering the head of Tutankhamen's mummy is inlaid primarily in lapis lazuli, with accents of turquoise and carnelian. In both the tombs of Tutankhamen and Queen Pu-abi, two of the richest tombs in all history, lapis lazuli was featured prominently in both. Called the "stone of rulers," in ancient kingdoms like Sumer and Egypt, lapis was forbidden to commoners, worn only by royalty. Ancient Egyptians believed lapis lazuli to be sacred and used it in the tombs and coffins of pharaohs.

Much of the lapis lazuli which flowed through the ancient land of Bactria and into Ur was exported to Egypt, where it was known as “khesbed”, which translates to “joy and delight”. In ancient Egypt lapis lazuli was widely used as a talisman believed to provide its wearers with good luck and ward off evil spirits and injury. Lapis lazuli was also thought to possess life-giving powers in ancient Egypt. Lapis was used to produce amulets to protect the mummified remains of pharaoh and commoner alike. It was a common practice to place a lapis amulet, engraved with a chapter of the Book of the Dead, over the area where the heart had been removed from the mummified remains (the heart was believed to be the repository of the soul), prior to the sealing of the sarcophagus.

Archaeological discoveries also have made it abundantly clear that coupled with gold, lapis lazuli was valued simply for its beauty as jewelry. Lapis lazuli was also associated with the ancient Egyptian Goddess “Hathor”, goddess of love, music, and beauty, who was often referred to as "the lady of lapis lazuli." Lapis was also associated with both the night sky and the rising run, which was sometimes referred to as the "child of lapis lazuli." The stone was also associated with the primordial waters of the ancient Egyptian creation myth. The Nile was rendered in blue color on grave paintings, blue thought to represent fertility. Lapis lazuli hippopotamuses produced by ancient Egyptian artisans were popular as symbols for the life-giving river.

There’s also some evidence that ancient Egyptian judges wore carved lapis amulets of Ma'at, the Goddess of truth, balance and order. These concepts were fundamental to Egyptian life and the rule of the Pharaohs, who portrayed themselves constantly as "Beloved of Ma'at" and "upholders of the universal order". Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs also described medicinal uses for lapis lazuli, including its use powdered, mixed with milk and mud from the Nile as a treatment for cataracts as well as head pains. And of course the ancient Egyptians made wide use of lapis lazuli as eye shadow. In fact, historians document its use as eye shadow by Cleopatra, last of the Ptolemaic rulers of Ancient Egypt.

Popular with another Middle Eastern people, the Israelites, lapis is generally acknowledged by Biblical scholars to be one of the breastplate stones of the High Priest. To the ancient Hebrews, lapis lazuli was the symbol of success, capturing the blue of the heavens and combining it with the glitter of gold in the sun. It was also believed by the ancient Hebrews that the tablets upon which Moses received the Ten Commandments were of lapis lazuli. Lapis lazuli was also used by the ancient Assyrians and Babylonians for cylinder seals. According to one ancient Persian legend, the heavens reflected their blue color from a massive slab of lapis upon which the earth rested. Throughout the history of the Ancient Middle East, lapis lazuli has often been regarded a sacred stone and to possess magical powers.

The first century Roman historian and naturalist Pliny the Elder accurately described lapis lazuli, though the ancient Romans referred to it as “sapphirus”. The Romans also used lapis lazuli as an aphrodisiac, and associated lapis lazuli with the lord of Gods of the Roman pantheon, “Jupiter” (“Zeus” to the ancient Greeks). Lapis lazuli was also accurately described by Theophrastos, the fourth century B.C. Greek philosopher and naturalist. In addition to its use in jewelry, lapis lazuli has also been used since ancient times for mosaics and other inlaid work, carved amulets, vases, and other objects. In antiquity, as well as in the Middle Ages, there was the belief that the cosmos was reflected in gemstones. Lapis lazuli was associated with the planet Jupiter.

In the medieval world lapis was ground and used as a pigment as well as for medicinal purposes. For medicinal applications, the powdered lapis lazuli was mixed with milk and used as a compress to relieve ulcers and boils. Lapis Lazuli and the mines at Badakhshan were described by Marco Polo in 1271 A.D., though the first written accounts of the mines had been produced three centuries earlier, in the tenth century A.D., by the Arab historian Istakhri. When lapis was first introduced to Europe, it was called "ultramarinum", which means "beyond the sea". It was identified as an emblem of chastity, and was thought to confer ability, success, divine favor, and ancient wisdom.

According to the 17th century “Complete Chemical Dispensatory”, lapis lazuli was effective as a cure for sore throat, used to combat melancholy, and a cure for “apoplexies, epilepsies, diseases of the spleen, and many forms of dementia”. The text also indicated that it could be worn about the neck as an amulet to drive away frights from children (timid children were given necklaces of lapis beads in the belief that they would develop courage and fearlessness) to strengthen sight, prevent fainting, and also to prevent miscarriages. Wearing an amulet made of lapis was also thought to free the soul from error, envy and fear as well as protect the wearer from evil. Ground lapis was also the secret of the blue in ultramarine, the pigment which painters used to paint the sea and the sky until the nineteenth century.

Used as a pigment most extensively in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the secret behind some of the most beautiful Renaissance-inspired paintings was ground lapis lazuli. In no small part due to the tremendous demand for lapis to produce ultramarine, the cost of lapis was exorbitant in Renaissance Europe. A price list of gems in the eighteenth century, using the emerald as the unit of value, ranked sapphire as twice the value of emerald, ruby as thrice the value, and lapis as fifteen times the cost of emerald. Lapis was also popular in inlays. In what was once one of the cultural capitals of Europe, the columns of St. Isaac's Cathedral in St Petersburg, Russia are lined with lapis (see here, here, and here ), and the Pushkin Palace has forty foot tall lapis lazuli paneling (see here, here, and here)! Though most of the lapis used in Russia’s landmark architecture was again, from Afghanistan, lapis lazuli was eventually discovered at Russia’s Lake Baikal, as well as in the Pamir Mountains of Central Asia (see here and here).

In the ancient history of Mesoamerica, an inferior grade of lapis lazuli was mined in Northern Chile for over 1,000 years by the Moche, a culture from the coast of Northern Peru (200 B.C. to 800 A.D.), who were skilled metalworkers, producing ornaments made of gold, silver, and lapis lazuli. Their traditions were carried forward by their successors the Chimu for another 600 years, the Chimu in turn ultimately absorbed by the Incas. Throughout the history of the ancient world, gemstones were believed capable of curing illness, possessed of valuable metaphysical properties, and to provide protection. Found in Egypt dated 1500 B. C., the "Papyrus Ebers" offered one of most complete therapeutic manuscripts containing prescriptions using gemstones and minerals.

Gemstones were not only valued for their medicinal and protective properties, but also for educational and spiritual enhancement. In the ancient world it was believed that ground lapis lazuli consumed as a supplement bolstered skeletal strength and thyroid function. It was also believed to improve sleep, cure insomnia, and was used to treat varicose veins. On the metaphysical plane, lapis lazuli was believed to enhance ones awareness, creativity, extra-sensory perception, and expand ones viewpoint, while keeping the spirit free from the negative emotions of fear and jealousy. Even today lapis lazuli is regarded by many cultures around the world as the stone of friendship and truth. The blue stone is said to encourage harmony in relationships and help its wearer to be authentic and give his or her opinion openly.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

Ancient Assyria: The foundation of the Assyrian dynasty can be traced to Zulilu, who is said to have lived after Bel-kap-kapu (c. 1900 B.C.), the ancestor of Shalmaneser I. The city-state of Ashur rose to prominence in northern Mesopotamia, founding trade colonies in Cappadocia. King Shamshi-Adad I (1813-1791 B.C.) expanded the domains of Ashur by defeating the kingdom of Mari, thus creating the first Assyrian kingdom. With the rise of Hammurabi of Babylonia (c. 1728–1686 B.C.) and his alliance with Mari, Assyria was conquered and reduced to a vassal state of Babylon.

In the 15th century B.C., Hurrians from Mitanni sacked Ashur and made Assyria a vassal. When Mitanni collapsed under pressure from the Hittites in Anatolia, Ashur again rose to power under Ashur-uballit I (1365-1330 B.C.). He married his daughter to the Kassite ruler of Babylon with disastrous results: The Kassite faction in Babylon murdered the king and placed a pretender on the throne. Ashur-uballit promptly marched into Babylonia and avenged his son-in-law.

Shalmaneser I (1274-1245 B.C.) declared that Assyria was no longer a vassal of Babylon and claimed supremacy over western Asia. He fought the Hittites in Anatolia, conquered Carchemish, and established more colonies in Cappadocia. His son Tukulti-Ninurta I (reigned 1243–1207 B.C.) conquered Babylon, putting its King Bitilyasu to death, and thereby made Assyria the dominant power in Mesopotamia. He ruled at Babylon for seven years and assumed the old imperial title "king of Sumer and Akkad". During a Babylonian revolt, he was murdered by his son, Ashur-nadin-apli. Babylon was once more independent from Assyria.

Tiglath-pileser I (1114-1076 B.C.), one of the great conquerors of Assyria, extended the remaining empire to Armenia in the north and Cappadocia in the west. He hunted wild bulls in Lebanon and was presented with a crocodile by the Egyptian pharaoh. Little is known of Tiglath-pileser's direct successors, and it is with Ashurnasirpal II (883-858 B.C.) that our knowledge of Assyrian history continues. The empire of Assyria was again extended in all directions, and the palaces, temples, and other buildings raised by Ashurnasirpal II bear witness to a considerable development of wealth and art. Nimrud (also known as the Biblical city of Calah or Kalakh) became the favorite residence of the monarch, who was distinguished even among Assyrian conquerors for his revolting cruelties. His son, Shalmaneser II (1031-1019 B.C.) continued the expansion of Assyria and even further militarized the country.

Tiglath-pileser I (1114-1076 B.C.), one of the great conquerors of Assyria, extended the remaining empire to Armenia in the north and Cappadocia in the west. He hunted wild bulls in Lebanon and was presented with a crocodile by the Egyptian pharaoh. Little is known of Tiglath-pileser's direct successors, and it is with Ashurnasirpal II (883-858 B.C.) that our knowledge of Assyrian history continues. The empire of Assyria was again extended in all directions, and the palaces, temples, and other buildings raised by Ashurnasirpal II bear witness to a considerable development of wealth and art. Nimrud (also known as the Biblical city of Calah or Kalakh) became the favorite residence of the monarch, who was distinguished even among Assyrian conquerors for his revolting cruelties. His son, Shalmaneser II (1031-1019 B.C.) continued the expansion of Assyria and even further militarized the country.

During the Middle Assyrian Period, the cities of Ashur, Nimrud, & Nineveh rose to prominence in the Tigris River valley. When Nabu-nazir ascended the throne of Babylon in 747 B.C., Assyria was in the throes of a revolution. In 746 B.C. Calah joined the rebels, and the rebel leader Pulu took the name of Tiglath-pileser III, seized the crown, and inaugurated a new and vigorous policy. During the Middle Assyrian Period, the cities of Ashur, Nimrud, and Nineveh rose to prominence in the Tigris River valley. Babylon remained the most important and probably the largest city of the period.

Under Tiglath-pileser III (ruled 745-727 B.C.) the Neo-Assyrian Empire arose, which differed from the first in its greater consolidation. For the first time in history the idea of centralization was introduced into politics; the conquered provinces were organized under an elaborate bureaucracy, with each district paying a fixed tribute and providing a military contingent.

The Assyrian forces became a standing army creating an irresistible fighting machine. Assyrian policy became geared towards conquering the known world. With this goal in mind, Tiglath-pileser III secured the high-roads of commerce to the Mediterranean together with the Phoenician seaports and then made himself master of Babylonia. In 729 B.C., the summit of his ambition was attained, and he was invested with the sovereignty of Asia in the holy city of Babylon. With his conquest of Israel (745-727 B.C.), the first wave of Israelite deportations had begun.

Tiglath-pileser was succeded by his son Shalmaneser V (reigned 727-722 B.C.) who died shortly after. The throne was seized by the general Sargon II (ruled 722-705 B.C.), who conquered the Hittie stronghold of Carchemish and annexed Ecbatana. He was seen as the successor of Sargon of Akkad. His son Sennacherib (ruled 704-681 B.C.) was a less skilled king who was never crowned in Babylon and eventually destroyed the holy city. Under his reign, Nineveh was built to become a new center of Assyrian power, famed for its library of cuneiform tablets. His reign, though, was one of terror, and upon his assassination both his subjects and enemies were relieved.

Esarhaddon (ruled 681-669 B.C.) succeesed Sennacherib and restored Babylon to its former glory, making it the second capital of the Assyrian empire. In 674 B.C. he sent the Assyrian armies to invade Egypt which was subsequently conquered. Two years later the Egyptians revolted and in his march to deal with the revolt, he fell ill and died.

Ashurbanipal (685-627 B.C.) succeeded him as king of the Assyrian Empire, and his brother Samas-sum-yukin was made viceroy in Babylonia. The arrangement failed, as Samas-sum-yukin did not prove to be popular with the Babylonians who revolted. After several years of war, during which Egypt regained its independence with the help of mercenaries sent by Gyges of Lydia, the Babylonian rebellion was put down. Shortly after, Elam rebelled, its capital Susa was razed, and the Empire was finally drained of all its resources.

The Scythians and Cimmerians invaded Assyria from the east and from the north, and when Ashurbanipal died, his Empire was close to collapse under external pressure. The Babylonian king Nabopolassar (ruled 625-605 B.C.), along with Cyaxares of the Medes (ruled 625-585 B.C.) finally destroyed Nineveh in 612 B.C., marking the end of the Assyrian Empire. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

HISTORY OF ANCIENT ASSYRIA: Assyrians trace their heritage to an ancient race of the same name, one of the few major factions which appeared after the collapse of the Akkadian Empire; the world's first Semitic empire created under Sargon I. At its peak, the Assyrian empire encompassed what is now western Iran, all of Mesopotamia and Syria, Israel, the Armenian highlands, and even threatened Egypt in the 8th and 7th centuries B.C. The ancient Assyrians were masters of siege warfare, and subdued many other ancient peoples of the region. For these reasons, the ancient pre-Christian Assyrians were greatly feared by other ancient peoples of the region.

Eventually however the Assyrians were one of the first nations to adopt Christianity as their state religion almost two thousand years ago. Assyria proper was located in a mountainous region, extending along the Tigris as far as the high Gordiaean or Carduchian mountain range of Armenia, sometimes called the "Mountains of Ashur". Little is known about the ancient Assyrians prior to the 25th century B.C. The original capital city of ancient Assyria was Ashur, and was originally part of Sargon the Great's Persian Empire (circa 24th century B.C.). Destroyed by barbarians, Assyria ended up being governed as part of the Third Dynasty of Ur, before eventually becoming an independent kingdom about 1900 B.C. The city-state of Ashur had extensive contact with cities on the Anatolian plateau (present-day Turkey).

The Assyrians established "merchant colonies" in Cappadocia which were attached to Anatolian cities, but physically separate, and had special tax status. They must have arisen from a long tradition of trade between Ashur and the Anatolian cities. The trade consisted of metal and textiles from Assyria that were traded for precious metals in Anatolia.The city of Ashur was conquered by the Hammurabi of Babylon, and ceased trading with Anatolia because the goods of Assyria were now being traded with the Babylonians' partners. In the 15th century B.C. the Hurrians of Mitanni sacked Ashur and made Assyria a vassal.

Assyria paid tribute to the Mitanni until they collapsed under pressure from the Hittites, when Assyria once again became an independent kingdom in the 14th century B.C., though at times a tributary of the Babylonian kings to the south. As the Hittite empire collapsed from onslaught of the Phrygians, Babylon and Assyria began to compete with one another for the Amorite lands formerly under firm Hittite control. The Assyrians defeated the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar when the forces encountered one another in this region. By 1120 B.C. the Assyrians had advanced as far as the Caspian Sea on one side, the Mediterranean on the other, conquering Phoenicia, and had also subjugated Babylonia as well.

Thereafter for nearly two centuries however the Assyrian’s grip over this vast empire steadily weakened centuries until when in 911 B.C. a strong ruler consolidated the Assyrian territories, and his success then embarked on a vast program of merciless expansion. In the mid ninth century B.C. the King of Israel marched in alliance with the Aramaic Kingdom against Assyria, the conflict ending in a deadlock, but a deadlock which presaged a withdrawal of Assyrian forces from the region of the Levant. The following centuries saw a continued decline of Assyria, the only exception being expansion on one front as far as the Caspian Sea. However by the eight century B.C.

Assyria had again become strong under Sargon the Tartan, again conquering both Philistine, Israel, Judah, and Samaria. In 705 BC, Sargon was slain while fighting the Cimmerians and was succeeded by his son who moved the capital to Momrveh. By 670 B.C. Assyria even briefly conquered Egypt, installing Psammetichus as a vassal king in 663 B.C. This proved to be the high water mark for ancient Assyria however. The Assyrian King Ashurbanipal had promoted art and culture and had a vast library of cuneiform tablets at Nineveh, but upon his death in 627 B.C., the Assyrian Empire began to disintegrate rapidly. Babylonia became independent; their king destroyed Nineveh in 612 B.C., and the mighty Assyrian Empire fell and ceased to exist as an independent nation [AncientGifts].

Ashur Assyria: Ashur (also known as Assur) was an Assyrian city located on a plateau above the Tigris River in Mesopotamia (today known as Qalat Sherqat, northern Iraq). The city was an important center of trade, as it lay squarely on a caravan trade route that ran through Mesopotamia to Anatolia and down through the Levant. It was founded circa 1900 B.C. on the site of a pre-existing community that had been built by the Akkadians at some point during the reign of Sargon the Great (2334-2279 B.C.) of Akkad. According to one interpretation of passages in the biblical Book of Genesis, Ashur was founded by a man named Ashur son of Shem, son of Noah, after the Great Flood, who then went on to found the other important Assyrian cities. A more likely account is that the city was named Ashur after the deity of that name sometime in the 3rd millennium B.C.; the same god's name is the origin for "Assyria".

The biblical version of the origin of Ashur appears later in the historical record after the Assyrians had accepted Christianity and so it is thought to be a re-interpretation of their early history which was more in keeping with their new belief system. Because of the lucrative trade Ashur enjoyed with the city of Karum Kanesh in Anatolia, it flourished and became the capital of the Assyrian Empire. Even after the capital was moved to the cities of Kalhu (Nimrud), then Dur-Sharrukin, and finally Nineveh, Ashur continued to be an important spiritual center for the Assyrians. All of the great kings (except for Sargon II, whose body was lost in battle) were buried at Ashur, from the earliest days of the Assyrian Empire down to the last, no matter where the capital city was located.

All the great Assyrian kings but one were buried at Ashur, no matter where the capital city was located. Archaeological excavations show that a city of some sort existed at the site as early as the 3rd millennium B.C.. What precise form this city took is not known nor is its size. The oldest foundations discovered thus far are those beneath the first Ishtar Temple, which probably formed the base for an earlier temple (as the Mesopotamians generally built the same sort of structure on the ruins of an earlier one). From pottery and other artifacts found in situ, it is known that Ashur was an important center of trade early in the Akkadian Empire and had been an outpost of the city of Akkad. In time, trade between Mesopotamia and Anatolia increased, and Ashur was among the most important cities in these transactions owing to its location. Merchants would send their wares via caravan into Anatolia and trade primarily at Karum Kanesh.

The historian Paul Kriwaczek writes: "For several generations the trading houses of Karum Kanesh flourished, and some became extremely wealthy – ancient millionaires. However not all business was kept within the family. Ashur had a sophisticated banking system and some of the capital that financed the Anatolian trade came from long-term investments made by independent speculators in return for a contractually specified proportion of the profits."

These profits were spent largely in the city on renovations and modifications to private homes and public buildings. Through trade, Ashur prospered and expanded, becoming the capital of Assyria by the second millennium B.C.. Walls were built around the city to enhance its natural defenses, even though these defenses were quite advantageous on their own. Regarding this, the historian Gwendolyn Leick writes: "The city of Ashur was built on a rocky limestone cliff that forced the fast-flowing Tigris into a sharp curve. The main stream was also joined by a side-arm in antiquity, so that an oval-shaped island was created with a shoreline of 1.80 kilometres (1.1 miles). Rocky outcrops rose some 25 metres (82 feet) above the valley floor, with steep sides. This naturally sheltered position had strategic importance as it made the site comparatively easy to defend, besides forming a landmark with a wide view over the valley."

As the city flourished, the Assyrians expanded their territory outwards. The Assyrian king Shamashi Adad I (1813-1791 B.C.) drove out the invading Amorite tribes and secured the borders of Ashur and Assyrian land against further incursions. The city grew under the reign of Shamashi Adad I and then fell to the might of Babylon under Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.). Hammurabi treated Ashur well and respected the gods and the temples but no longer permitted the city to trade with Anatolia. Babylon took over the trade route that had made Ashur wealthy, and the Assyrian city was forced to trade only with Babylon; this caused a decline in the prosperity of Ashur and it languished as a vassal state.

When Hammurabi died in 1750 B.C., the region erupted in turmoil and civil war as city-states competed with each other for control. Stability was finally achieved by the Assyrian king Adasi (1726-1691 B.C.) but, by that time, the kingdom of Mitanni had grown up in western Anatolia and slowly spread through Mesopotamia, now holding Ashur as part of its territory. Ashur again languished as a vassal state until the rise of the Assyrian king Ashur-Ubalit I (1353-1318 B.C.) who defeated the Mitanni and took large portions of their territory. The Kingdom of Mitanni had suffered significant losses since the days of its prime, ever since the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (1344-1322 B.C.) conquered them and replaced Mitanni rulers with Hittite officials.

Ashur-Ubalit I defeated these Hittite rulers in combat but could not dislodge their hold on the region completely. The later king Adad Nirari I (1307-1275 B.C.) conquered the Hittites and took the lands of the Mitanni to create the first semblance of an Assyrian empire. Ruling from Ashur, he led his victorious army throughout the region and sent the loot from his conquests back to the city. Ashur was again prosperous and began again to develop and expand. Adad Nirari I commissioned many building projects in the city and improved the walls. It is from this point on that Ashur becomes the city of note made famous as the capital of the Assyrian Empire.

Adad Nirari I’s son, Shalmaneser I (1274-1245 B.C.), continued improvements on the city and was so prosperous that he was also able to build the city of Kalhu (also known as Nimrud, which would later become the capital). His son, Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244-1208 B.C.), took renovations and building projects even further. Tukulti-Ninurta I built his own city, called Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta (Harbor of Tukulti-Ninurta) across the river from Ashur. For some time now, historians have claimed that this city was built after Tukulti-Ninurta I’s sack of Babylon in circa 1225 B.C. because of inscriptions found at the site which seemed to support this version of history. It is now thought, based on other inscriptions and records and archeological evidence at the site, that the king began building his city early in his reign. His reasons for doing so could have been that there was little left to improve on in the city of Ashur and he wanted some impressive building project that would separate his name from that of his predecessors.

He had already renovated the Temple of Ishtar in Ashur and commissioned other projects but these were simply improving upon what the earlier kings had accomplished. As Tukulti-Ninurta I was an ambitious man with a grand vision of himself, only the construction of a completely new city bearing his name seemed to suit his purposes. Although Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta was earlier thought to have been built as the new capital to replace Ashur, this theory is no longer accepted by many historians. Records indicate that the same officials who worked in the palace at Ashur also worked across the river in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta at the same time, suggesting that business continued as usual in the capital city. Tukulti-Ninurta I clearly favored his new city, however, since he seems to have lavished the wealth he plundered from the temples of Babylon on his new palace and other projects in Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta. The king was assassinated in his palace by his son because of his treatment of Babylon and, especially, the sack of the temples; after his death, his city was abandoned in favor of Ashur and eventually decayed and collapsed.

Ashur continued as the capital and jewel of the empire into the later reign of Tiglath Pileser I (1115-1076 B.C.) who issued his famous law code from the city and lavished his wealth on improvements to the palace and walls. Like his predecessors, he campaigned with his troops throughout the region and expanded Assyrian territory significantly but, after his death, the kingdom he had built fell apart. Ashur during this time remained stable, if not especially prosperous, and the kings who followed Tiglath Pileser I were able to retain the lands surrounding the city, even though they lost regions further away.

With the rise of Adad-Nirari II (912-891 B.C.), the city again enjoyed its former prosperity and the Assyrian Empire began to rise. Adad-Nirari II re-conquered the regions that had slipped from Assyrian control and expanded the empire further in every direction. Ashur was now the hub of the giant wheel of empire, and wealth regularly flowed into the capital from the military campaigns of the kings. The Assyrian policy of deporting and re-locating large segments of the population of conquered regions also impacted Ashur in that scribes and scholars were regularly sent there to work in the library, palace, or in the schools. This helped to make Ashur a center of learning and culture. When Tukulti-Ninurta I sacked Babylon, part of the loot he brought back to Ashur was books. The clay tablets upon which the stories and myths and legends of Babylon were written now filled the shelves of Ashur’s library and, as they were copied by the scribes, influenced Assyrian writers and were also preserved for the future.

The king Ashurnasirpal II (884-859 B.C.) moved the capital from Ashur to Kalhu, but this had no effect on the prosperity or importance of Ashur. Kalhu was renovated following Ashurnasirpal II’s successful campaigns, and he most likely made it his capital for the same reason Tukulti-Ninurta I built his city: to elevate his name above his predecessors. The historian Marc Van De Mieroop writes, “The kings must have had a motivation for the building of these vast cities, but when we look at their records no reason for the work is declared. Ashurnasirpal’s justification for the work on Kalhu is merely a statement that the city built by his predecessor Shalmaneser had become dilapidated” (55). There is also no reason stated for making Kalhu the new capital, and this move seems particularly strange when one considers the natural defenses of Ashur and the strength of its walls.

One suggested theory is that Ashurnasirpal II wanted a virgin city whose populace had no cohesive identity. Ashur, by this time, was a very prestigious city and its citizens prided themselves on their city and being Ashurians. It has therefore been proposed that Ashurnasirpal II moved the capital in order to create a royal power base with a less proud, and therefore more easily managed, population. A stele found in the ruins of Kalhu describes the inauguration festival of the new capital at which Ashurnasirpal II fed 69,574 men and women from his kingdom for ten days. Other inscriptions in the city tell of how Ashurnasirpal II referred to Kalhu as “my royal dwelling and for my lordly pleasure for all time” and how he planted saplings of 41 types of trees around the new city and dug massive canals and irrigation ditches (Van De Mieroop, 68). All of this was done to elevate the new capital city above Ashur, and yet there is no evidence of any decline in Ashur’s status throughout the next 150 years in which Kalhu was the capital.

Ashur was successfully defended during the civil wars which marked the reign of Shamshi Adad (824-811 B.C.) and was renovated under the kings who followed him. Tiglath Pileser III (745-727 B.C. further enriched the city and strengthened the walls and his successors would do likewise. Sennacherib (705-681 B.C.) brought the spoils of his sack of Babylon back to Ashur even though, by that time, Nineveh was the capital city and the site of his palace “without rival”. He clearly poured this wealth into the gardens, parks, and the palace at Nineveh but continued to honor the ancient city of his ancestors. The kings who followed him, Esarhaddon (681-669 B.C.) and Ashurbanipal (668-627 B.C.), also honored the city with gifts and building projects. When Ashurbanipal died, the regions of the Assyrian Empire rose in revolt and the empire began to break apart. Ashurbanipal’s successors could do nothing to stop the rapid decline and the empire fell. The city of Ashur was destroyed in 612 B.C. by the combined forces of the Babylonians, Medes, and Persians, along with the other great Assyrian cities such as Nineveh. The city lay in ruin but was re-populated and partially re-built at some point. Ashur continued as a settlement up through the 14th century CE but would never again be as prosperous as it had been during its golden age. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Climate Change in Ancient Assyria: Adam Schneider of the University of California-San Diego and Selim Adali of the Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations in Turkey argue in the journal Climatic Change that drought and population expansion contributed to the decline of the Assyrian Empire. Located in northern Iraq, the Assyrian Empire reached its height in the early seventh century B.C., but then experienced a quick decline, including civil wars, political unrest, and the destruction of Nineveh, the capital, by the end of the century. Paleoclimate data show that the region became more arid during the latter half of the seventh century B.C., at the same time that peoples conquered by the Assyrians were resettled there. Said Schneider, “What we are proposing is that these demographic and climatic factors played an indirect but significant role in the demise of the Assyrian Empire”.

There's more to the decline of the once mighty ancient Assyrian Empire than just civil wars and political unrest. Archaeological, historical, and paleoclimatic evidence suggests that climatic factors and population growth might also have come into play. In the 9th century B.C., the Assyrian Empire of northern Iraq relentlessly started to expand into most of the ancient Near East. It reached its height in the early 7th century B.C., becoming the largest of its kind in the Near East up to that time. The Assyrian Empire's subsequent quick decline by the end of the 7th century has puzzled scholars ever since. Most ascribe it to civil wars, political unrest, and the destruction of the Assyrian capital, Nineveh, by a coalition of Babylonian and Median forces in 612 B.C.. Nevertheless, it has remained a mystery why the Assyrian state, the military superpower of the age, succumbed so suddenly and so quickly.

Schneider and Adalı argue that factors such as population growth and droughts also contributed to the Assyrian downfall. Recently published paleoclimate data show that conditions in the Near East became more arid during the latter half of the 7th century B.C.. During this time, the region also experienced significant population growth when people from conquered lands were forcibly resettled there. The authors contend that this substantially reduced the state's ability to withstand a severe drought such as the one that hit the Near East in 657 B.C. They also note that within five years of this drought, the political and economic stability of the Assyrian state had eroded, resulting in a series of civil wars that fatally weakened it.

Schneider and Adalı further draw parallels between the collapse of the Assyrian Empire and some of the potential economic and political consequences of climate change in the same area today. They point out, for instance, that the onset of severe drought which, followed by violent unrest in Syria and Iraq during the late 7th century B.C., bears a striking resemblance to the severe drought and subsequent contemporary political conflict in Syria and northern Iraq today. On a more global scale, they conclude, modern societies can take note of what happened when short-term economic and political policies were prioritized rather than ones that support long-term economic security and risk mitigation.

"The Assyrians can be 'excused' to some extent for focusing on short-term economic or political goals which increased their risk of being negatively impacted by climate change, given their technological capacity and their level of scientific understanding about how the natural world worked," adds Selim Adalı. "We, however, have no such excuses, and we also possess the additional benefit of hindsight. This allows us to piece together from the past what can go wrong if we choose not to enact policies that promote longer-term sustainability." [Archaeological Institute of America and Phys.Org].

The Assyrian God Assur: Assur (also Ashur, Anshar) is the god of the Assyrians who was elevated from a local deity of the city of Ashur to the supreme god of the Assyrian pantheon. The Assyrian Empire, like the later empire of the Romans, had a great talent for borrowing from other cultures. This penchant is illustrated clearly in the figure of Assur whose character and attributes draw on the Sumerian and Babylonian gods. Assur's family and history are modeled on the Sumerian Anu and Enlil and the Babylonian Marduk; his power and attributes mirror Anu's, Enlil's, and Marduk's as do details of his family: Assur's wife is Ninlil (Enlil's wife) and his son is Nabu (Marduk's son). Assur had no actual history of his own, such as those created for Sumerian and Babylonian gods but borrowed from these other myths to create a supreme deity whose worship, at its height, was almost monotheistic.

Scholar Jeremy Black notes: "In spite of (or possibly because of) the tendencies to transfer to him the attributes and mythology of other gods, Assur remains an indistinct deity with no clear character or tradition (or iconography) of his own." Assur had no actual history of his own but borrowed from other myths to create a supreme deity whose worship, at its height, was almost monotheistic.

Assur had power over the kingship of Assyria but, in this, was no different from Marduk of Babylon. The king of Assyria was his chief priest and all those who tended his temple in the city of Ashur and elsewhere lesser priests. Assyrian kings frequently chose his name as an element in their own to honor him (Ashurbanipal, Ashurnasirpal I, Ashurnasirpal II, etc). Worship of Assur consisted, as with other Mesopotamian deities, of priests tending the statue of the god in the temple and taking care of the duties of the complex surrounding it. Although people may have engaged in private rituals honoring the god or asking for assistance, there were no temple services as one would recognize them in the modern day.

The iconography of Assur is often taken from the Sumerian Anu, a crown or a crown on a throne, but he is as frequently represented as a warrior-god wearing a horned helmet and carrying a bow and quiver of arrows. He wears a short skirt of feathers and is sometimes depicted within a winged disk (although the association of Assur with the solar disk is contested by a number of modern scholars, among them Jeremy Black). Assur is also sometimes represented standing on a snake-dragon, an image borrowed from the Babylonian Marduk, among other gods.

Assur is first positively attested to in the Ur III Period (2047-1750 B.C.) of Mesopotamian history. He is identified as the patron god of the city of Ashur circa 1900 B.C. at its founding and also gives his name to the Assyrians. From a local, and probably agricultural, god who personified the city, Assur steadily acquired greater and greater attributes. The scholar E. A. Wallis Budge describes the general progression gods made from spirits to local deities to supreme gods:

"The oldest of such spirits was the 'house spirit' or household-god. When men formed themselves into village communities the idea of the 'spirit of the village' was evolved and later came the "god of the town or city" and the 'god of the country'. Each of the elements, earth, air, fire, and water had its spirit or 'god', the earthquake, lightning, thunder, rain, storm, desert whirlwind, each likewise its spirit or 'god', and of course each plant, tree, and animal. As time went on, men began to think that certain spirits were more powerful than others and these they selected for special reverence or worship." Such was the case with Assur in that he is originally referenced as the god of only the locale surrounding the city but came to personify and represent the entire nation of Assyria. His city mirrored his rise to fame as Ashur began as a small trading center built on the site of an earlier community founded by Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 B.C.) but flourished through trade with Anatolia and with other regions of Mesopotamia to become the capital of Assyria by the time of the reign of the Assyrian king Shamashi Adad I (1813-1791 B.C.). Shamashi Adad I drove the Amorites from the region in Assur's name and secured his boundaries but was defeated by the Amorite king Hammurabi of Babylon (1792-1750 B.C.) who then controlled the region. Worship of Assur at this time was restricted to the city and the Assyrian lands surrounding it, while Marduk of Babylon was worshiped as the supreme god and the Babylonian work Enuma Elish was considered the authoritative piece on creation and the birth of the gods and humanity.

In the tumult following Hammurabi's death, different powers controlled the region and their gods were considered supreme. The Mitanni and the Hittites both held Ashur and Assyrian areas as a vassal state until they were defeated by king Adad Nirari I (1307-1275 B.C.), who united the lands under the first semblance of an Assyrian empire. Assur is credited by the king as the god who granted him the victory, but no history of the god existed to glorify. Scholar Jeremy Black comments on this:

"Eventually, with the growth of Assyria and the increase in cultural contacts with southern Mesopotamia, there was a tendency to assimilate Assur to certain of the major deities of the Sumerian and Babylonian pantheons. From about 1300 B.C. we can trace some attempts to identify him with Sumerian Enlil. This probably represents an effort to cast him as the chief of the gods...Then, under Sargon II of Assyria (reigned 722-705 B.C.), Assur tended to be identified with Anshar, the father of Anu (An) in the Babylonian Epic of Creation. The process thus represented Assur as a god of long-standing, present from the creation of the universe."

From the time of Adad Nirari I to the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire of Sargon II, Assur continued to rise in prominence. In the Enuma Elish, Assur (under the name Anshar) replaced Marduk as the hero. Tiglath Pileser I (1115-1076 B.C.) regularly invokes Assur as the god of the empire who empowers the army and leads them to victory and even credits Assur with the laws of the empire. Adad Nirari II (912-891 B.C.) expanded the empire in every direction with Assur as his personal patron. Everywhere the Assyrian army traveled, Assur traveled with them, and thus his worship spread across Mesopotamia. Wallis Budge writes, "As the power of Marduk became predominant when Babylon grew into a great city, so the power of Assur waxed great when the Assyrians became a strong and warlike nation" (88). To the men who marched in the Assyrian forces, as well as to those they conquered, Assur was obviously a powerful god worthy of worship and devotion and, in time, he became so powerful as to eclipse the earlier gods of the region.

When Ashurnasirpal II (884-859 B.C.) came to power, he moved the capital of the empire from Ashur to the city of Kalhu, but this is no indication of waning power on Assur's part; Ashurnasirpal II had Assur's name as part of his own (his name means 'Assur is Guardian of the Heir'). The reason for the capital's move is unclear, but most likely it was only because Ashur had grown so great and the populace fiercely proud and Ashurnasirpal II wanted to surround himself with humbler and more easily manageable people. Tiglath Pileser III (745-727 B.C.) elevated Assur's name even higher through the stunning victories which marked his reign. Tiglath Pileser III created the first professional army in the history of the world, who, armed with iron weapons, were invincible. Along with the new kind of army, new technology was created such as siege engines which allowed the army to take whole cities with fewer losses.

As the Assyrian armies campaigned throughout the land, Assur led them to greater and greater victories. Previously, however, Assur had been linked with the temple of the city of Ashur and had only been worshiped there. As the Assyrians made wider and wider gains in territory, a new way of imagining the god became necessary in order to continue that worship in other locales. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek explains how, in order to maintain worship of Assur, the nature of a god - and how that god should be understood and worshiped - had to change: "One might pray to Assur not only in his own temple in his own city, but anywhere. As the Assyrian empire expanded its borders, Assur was encountered in even the most distant places. From faith in an omnipresent god to belief in a single god is not a long step. Since He was everywhere, people came to understand that, in some sense, local divinities were just different manifestations of the same Assur." This unity of vision of a supreme deity helped to further unify the regions of the empire. The different gods of the conquered peoples and their various religious practices became absorbed into the worship of Assur, who was recognized as the one true god who had been called different names by different people in the past but who now was clearly known and could be properly worshiped as the universal deity. Regarding this, Kriwaczek writes:

"Belief in the transcendence rather than immanence of the divine had important consequences. Nature came to be desacralized, deconsecrated. Since the gods were outside and above nature, humanity – according to Mesopotamian belief created in the likeness of the gods and as servant to the gods – must be outside and above nature too. Rather than an integral part of the natural earth, the human race was now her superior and her ruler. The new attitude was later summed up in Genesis 1:26: 'And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let him have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth'."

"That is all very well for men, explicitly singled out in that passage. But for women it poses an insurmountable difficulty. While males can delude themselves and each other that they are outside, above, and superior to nature, women cannot so distance themselves, for their physiology makes them clearly and obviously part of the natural world…It is no accident that even today those religions that put most emphasis on God’s utter transcendence and the impossibility even to imagine His reality should relegate women to a lower rung of existence, their participation in public religious worship only grudgingly permitted, if at all."

Women in Mesopotamia had enjoyed almost equal rights with men until the rise of Hammurabi and his god Marduk. Under Hammurabi's reign, female deities began to lose prestige as male gods became increasingly elevated. Under Assyrian rule, with Assur as supreme god, women's rights suffered further. Cultures like the Phoenicians, who had always regarded women with great respect, were forced to follow the customs and beliefs of the conquerors. The Assyrian culture became increasingly cohesive with the expansion of the empire, the new understanding of the deity, and the assimilation of the people from the conquered regions. Shalmaneser III (859-824 B.C.) expanded the empire up through the coast of the Mediterranean and received regular tribute from wealthy Phoenician cities such as Tyre and Sidon.

Assur was now the supreme god not only of the Assyrians but of all those people who were brought under their rule. To the Assyrians, of course, this was an ideal situation, but this opinion was not shared by every nationality they had conquered, and when the opportunity presented itself, they would vent their frustrations dramatically.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire (912-612 B.C.) is the last expression of Assyrian political power in Mesopotamia and is the one most familiar to students of ancient history. The kings of this period are the ones most often mentioned in the Bible and best known by people in the present day. It is also the era which most decisively gives the Assyrian Empire the reputation it has for ruthlessness and cruelty. Kriwaczek comments on this, writing: "Assyria must surely have among the worst press notices of any state in history. Babylon may be a byname for corruption, decadence and sin but the Assyrians and their famous rulers, with terrifying names like Shalmaneser, Tiglath-Pileser, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, rate in the popular imagination just below Adolf Hitler and Genghis Khan for cruelty, violence, and sheer murderous savagery."

Although there is no denying the Assyrians could be ruthless and were quite clearly not to be trifled with, they were really no more savage or barbaric than any other ancient civilization. In order to form and maintain an empire, they destroyed cities and murdered people, but in this, they were no different from those who preceded and followed them, save in that they were easily more efficient than most.

To the conquered people, however, the Assyrians were seen as hated overlords. The last great king of the empire was Ashurbanipal (668-627 B.C.) and, after him, the empire began to break apart. There were many reasons for this but, mainly, it had simply grown too large to manage. As the power of the central government became less and less able to cope, more territories broke away from the empire. In 612 B.C. a coalition of Babylonians, Medes, Persians, and others rose against the Assyrian cities and destroyed them. Included in this onslaught was the city of Ashur and the temple of the god as well as other statues of Assur elsewhere. Assur had come to personify the Assyrians, their military victories, and their political power, and so the destruction of this symbol was of special importance to Assyria's enemies.

Worship of Assur continued in Assyrian communities after the fall of the empire but was no longer widespread and no temples, shrines, or statuaries were left standing in the cities and regions which had revolted. In the early Christian era, the understanding of Assur as an omnipotent deity worked well for the early Christian missionaries to the region, who found the Assyrians receptive to their message of a single god and the concept of this god's son coming to earth for the benefit of humanity. Although Assur's son Nabu never became incarnated or sacrificed himself for others, he was thought to have given human beings the gift of the written word. Nabu continued to be venerated after the fall of the empire, and although Assur declined in stature, he was remembered and is still present (often as Ashur) as a personal and family name in the present day. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Ancient Assyrian Tomb: A vaulted brick tomb dating to between the ninth and seventh centuries B.C. was discovered by construction workers in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, according to a report in Live Science. The tomb was situated near the ancient city of Arbela (Erbil), where an important temple of Ishtar, the Assyrian goddess of war, was located. Goran M. Amin of the Directorate of Antiquities in Erbil, the modern name for Arbela, said that two skeletons were found in three ceramic sarcophagi within the tomb, while an additional eight skeletons were found on the ground. More than 40 intact jars of different shapes and sizes were also recovered. Similar tombs, built for elites, have been found in other Assyrian cities such as Nimrud. “Sometimes the tombs have been opened several times, when they wanted to bury new dead members of the family,” added Dishad Marf Zamua of Salahaddin University. [Archaeological Institute of America].

Ancient Ashdod, Assyria: A crescent-shaped, mudbrick wall that was more than 12 feet wide and 15 feet tall and covered with layers of mud and sand has been unearthed at Ashdod-Yam, an area under Assyrian rule in the eighth century B.C. This massive, Iron-Age fortification may have protected a large artificial harbor. “If so, this would be a discovery of international significance, the first known harbor of this kind in our corner of the Levant,” said Alexander Fantalkin of Tel Aviv University. The structure may have been built in connection with a rebellion led by the Philistine king of nearby Ashdod. [Archaeological Institute of America].

Ancient Idu, Assyria Archaeologists working in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq have located the ancient city of Idu. The international team unearthed the settlement while excavating a tell along the Lower Zab River. Although Idu’s existence was known from Assyrian texts, its location was previously unidentified. Beginning in the thirteenth century B.C., Idu flourished as a provincial capital of the Assyrian Empire. During this period, and also during the interval when Idu gained its independence, the settlement featured lavish royal palaces. This prosperity is attested to by ornate bricks, cylinder seals, and artworks that depict mythological scenes. Researchers ascertained the city’s identity through a series of cuneiform inscriptions. “The discovery of Idu fills a gap in what scholars had previously thought was a dark age in the history of the ancient Near East, and it helped us to redraw the political and historical map of Assyria in its early stage,” says Cinzia Pappi, an archaeologist from the University of Leipzig. [Archaeological Institute of America].

SHIPPING & RETURNS/REFUNDS: Your purchase will ordinarily be shipped within 48 hours of payment. We package as well as anyone in the business, with lots of protective padding and containers. All of our shipments are fully insured against loss, and our shipping rates include the cost of this coverage (through stamps.com, Shipsaver.com, the USPS, UPS, or Fed-Ex). International tracking is provided free by the USPS for certain countries, other countries are at additional cost. ADDITIONAL PURCHASES do receive a VERY LARGE discount, typically about $5 per item so as to reward you for the economies of combined shipping/insurance costs. We do offer U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail, Registered Mail, and Express Mail for both international and domestic shipments, as well United Parcel Service (UPS) and Federal Express (Fed-Ex). Please ask for a rate quotation. We will accept whatever payment method you are most comfortable with.

Please note for international purchasers we will do everything we can to minimize your liability for VAT and/or duties. But we cannot assume any responsibility or liability for whatever taxes or duties may be levied on your purchase by the country of your residence. If you don’t like the tax and duty schemes your government imposes, please complain to them. We have no ability to influence or moderate your country’s tax/duty schemes. If upon receipt of the item you are disappointed for any reason whatever, I offer a no questions asked 30-day return policy. Send it back, I will give you a complete refund of the purchase price; 1) less our original shipping/insurance costs, 2) less any non-refundable eBay fees. Please note that though they generally do, eBay may not always refund payment processing fees on returns beyond a 30-day purchase window. So except for shipping costs and any payment processing fees not refunded by eBay, we will refund all proceeds from the sale of a return item. Obviously we have no ability to influence, modify or waive eBay policies.

ABOUT US: Prior to our retirement we used to travel to Eastern Europe and Central Asia several times a year seeking antique gemstones and jewelry from the globe’s most prolific gemstone producing and cutting centers. Most of the items we offer came from acquisitions we made in Eastern Europe, India, and from the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean/Near East) during these years from various institutions and dealers. Much of what we generate on Etsy, Amazon and Ebay goes to support worthy institutions in Europe and Asia connected with Anthropology and Archaeology. Though we have a collection of ancient coins numbering in the tens of thousands, our primary interests are ancient/antique jewelry and gemstones, a reflection of our academic backgrounds.

Though perhaps difficult to find in the USA, in Eastern Europe and Central Asia antique gemstones are commonly dismounted from old, broken settings – the gold reused – the gemstones recut and reset. Before these gorgeous antique gemstones are recut, we try to acquire the best of them in their original, antique, hand-finished state – most of them originally crafted a century or more ago. We believe that the work created by these long-gone master artisans is worth protecting and preserving rather than destroying this heritage of antique gemstones by recutting the original work out of existence. That by preserving their work, in a sense, we are preserving their lives and the legacy they left for modern times. Far better to appreciate their craft than to destroy it with modern cutting.

Not everyone agrees – fully 95% or more of the antique gemstones which come into these marketplaces are recut, and the heritage of the past lost. But if you agree with us that the past is worth protecting, and that past lives and the produce of those lives still matters today, consider buying an antique, hand cut, natural gemstone rather than one of the mass-produced machine cut (often synthetic or “lab produced”) gemstones which dominate the market today. We can set most any antique gemstone you purchase from us in your choice of styles and metals ranging from rings to pendants to earrings and bracelets; in sterling silver, 14kt solid gold, and 14kt gold fill. When you purchase from us, you can count on quick shipping and careful, secure packaging. We would be happy to provide you with a certificate/guarantee of authenticity for any item you purchase from us. There is a $3 fee for mailing under separate cover. I will always respond to every inquiry whether via email or eBay message, so please feel free to write.