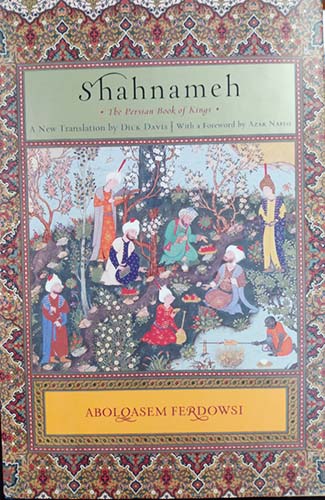

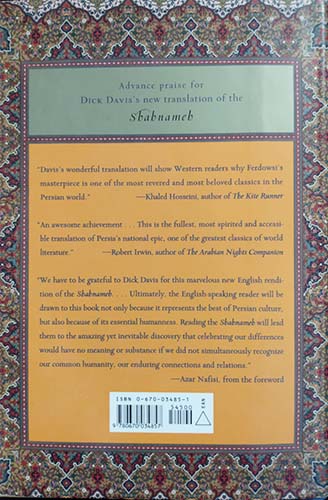

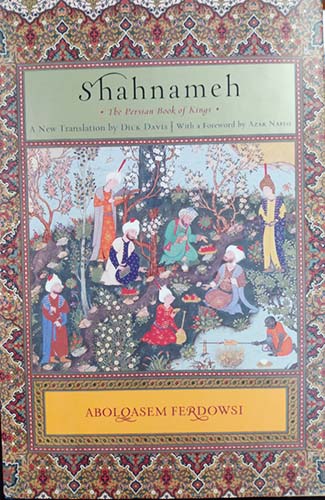

”Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings” by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. Translated by Dick Davis.

NOTE: We have 100,000 books in our library, over 10,400 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: HUGE hardcover w/dustjacket. Publisher: Viking (2006). Pages: 928. Size: 9½ x 6¼ x 2¼ inches; 3¼ pounds. Summary: Among the great works of world literature, perhaps one of the least familiar to English readers is the “Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings”, the national epic of Persia. This prodigious narrative, composed by the poet Ferdowsi between the years 980 and 1010, tells the story of pre- Islamic Iran, beginning in the mythic time of Creation and continuing forward to the Arab invasion in the seventh century.

As a window on the world, Shahnameh belongs in the company of such literary masterpieces as Dante’s “Divine Comedy”, the plays of Shakespeare, the epics of Homer’s classics whose reach and range bring whole cultures into view. In its pages are unforgettable moments of national triumph and failure, human courage and cruelty, blissful love and bitter grief.

In tracing the roots of Iran, Shahnameh initially draws on the depths of legend and then carries its story into historical times, when ancient Persia was swept into an expanding Islamic empire. Now Dick Davis, the greatest modern translator of Persian poetry, has revisited that poem, turning the finest stories of Ferdowsi’s original into an elegant combination of prose and verse. For the first time in English, in the most complete form possible, readers can experience Shahnameh in the same way that Iranian storytellers have lovingly conveyed it in Persian for the past thousand years.

CONDITION: LIKE NEW. Unread (and in that sense "new") albeit "remaindered" (marked as unsold surplus) hardcover with (faintly shelfworn) dustjacket. Viking (2006) 928 pages. Unblemished in every respect EXCEPT that there is very faint edge and corner shelfwear to dustjacket and covers (more on that hereinbelow) AND there is a black remainder mark (a longish line drawn with a black marker) on the bottom edge of the closed page edges indicating that the book is unsold surplus inventory. The "remainder mark" (black marker line) is not visible of course on individual opened pages, only to the mass of closed page edges (sometimes referred to as the "page block"). Inside the book is pristine. The pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. From the outside the dustjacket and covers do evidence very faint edge and corner shelfwear, principally in the form of very faint crinkling at the spine head and heel. And by "faint", we mean precisely that, literally. It requires that you hold the book up to a light source, tilting it this way and that so as to catch the reflected light, and scrutinize it quite intently to discern the very, very faint crinkling. Condition is entirely consistent with new (albeit "remaindered") stock from a traditional brick-and-mortar shelved bookstore environment such as Borders, Barnes & Noble, or B. Dalton for example), where otherwise "new" (albeit "remaindered"; i.e. surplus unsold) books might show faint signs of shelfwear simply as a consequence of routine handling. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #455a.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: A new translation of the late-tenth-century Persian epic follows its story of pre-Islamic Iran's mythic time of Creation through the seventh-century Arab invasion, tracing ancient Persia's incorporation into an expanding Islamic empire. 15,000 first printing.

REVIEW: Ferdowsi’s classic poem Shahnameh is part myth, part history. It begins with the legend of the birth of the Persian nation and its tumultuous history. It contains magical birds and superhuman heroes and centuries-long battles. Written over 1,000 years ago, it was meant to protect Persian collective memory amidst a turbulent sea of cultural storms.

REVIEW: The definitive translation by Dick Davis of the great national epic of Iran, now newly revised and expanded to be the most complete English-language edition, has revised and expanded his acclaimed translation of Ferdowsi's masterpiece, adding more than seventy pages of newly translated text. Davis's elegant combination of prose and verse allows the poetry of the Shahnameh to sing its own tales directly, interspersed sparingly with clearly marked explanations to ease along modern readers.

Originally composed for the Samanid princes of Khorasan in the tenth century, the Shahnameh is among the greatest works of world literature. This prodigious narrative tells the story of pre-Islamic Persia, from the mythical creation of the world and the dawn of Persian civilization through the seventh-century Arab conquest. The stories of the Shahnameh are deeply embedded in Persian culture and beyond, as attested by their appearance in such works as The Kite Runner and the love poems of Rumi and Hafez.

For more than sixty-five years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world.

REVIEW: The greatest modern translator of Persian poetry revisits the literary masterpiece that tells the story of pre-Islamic Iran, beginning in the mythic time of Creation and continuing forward to the Arab invasion in the seventh century. Illustrations throughout.

REVIEW: Dick Davis brings a unique array of gifts to the challenges of translating Hafez and his contemporaries. In his own right, he is a poet of great technical accomplishment and emotional depth. He is also the foremost English-speaking scholar of medieval Persian poetry now working in the West. Numerous honors testify to his talents. In the U.K., he received the Royal Society of Literature’s Heinemann Award for his second book of poems, Seeing the World, in 1981; his Selected Poems was chosen by both the Sunday Times and the Daily Telegraph as a Book of the Year in 1989; and his collection Belonging was selected as the Poetry Book of the Year by The Economist in 2003. In the U.S., A Kind of Love—the American edition of his Selected Poems—received the Ingram Merrill prize for “excellence in poetry” in 1993.

He has received awards for his scholarship from the Arts Council of Great Britain, The British Institute of Persian Studies, and the Guggenheim Foundation, and he is the recipient of grants for his translations from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts. Twice, in 2000 and 2001, he received the Translation Award of the International Society for Iranian Studies, and in 2001 he received an Encyclopedia Iranica award for “services to Persian poetry.” His translation of Ferdowsi’s “Shahnameh: the Persian Book of Kings” was chosen as one of the “ten best books of 2006” by the Washington Post.

Davis read English at Cambridge, lived in Iran for eight years (he met and married his Iranian wife Afkham Darbandi there), then completed a PhD in Medieval Persian Literature at the University of Manchester. He has resided for extended periods in both Greece and Italy (his translations include works from Italian), and has taught at both the University of California and at Ohio State University, where he was for nine years Professor of Persian and Chair of the Department of Near Eastern Languages, retiring from that position in 2012. In all, he has published more than twenty books.

Among the qualities that distinguish his poetry and scholarship are exacting technical expertise and wide cultural sympathy—an ability to enter into distant cultural milieus both intellectually and emotionally. In choosing his volume of poems Belonging as a “Book of the Year” for 2006, The Economist praised it as “a profound and beautiful collection” that gave evidence of “a commitment to an ideal of civilized life shared by many cultures.” the Times Literary Supplement has called him “our finest translator of Persian poetry”.

REVIEW: Abolqasem Ferdowsi was born in Khorasan in a village near Tus in 940. His great epic, Shahnameh, was originally composed for the Samanid princes of Khorasan. Ferdowsi died around 1020 in poverty.

Dick Davis is currently professor of Persian at Ohio State University and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His translations from Persian include The Lion and the Throne, Fathers and Sons, Sunset of Empire: Stories from the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, Volumes I, II, III.

Azar Nafisi is the author of Reading Lolita in Tehran, an international bestseller.

REVIEW: [From the Author] The ancient legends of the Persian Book of Kings (Shahnameh) were versified by Abolqasem Ferdowsi (940-1020 AD), who was born to a family of small landowners near the city of Tus, in northeastern Iran. He dedicated thirty-three years of his life to Shahnameh and finished its second redaction one thousand and three years ago, in March 1010.

Shahnameh is of the essence of Iranian nationhood. Unlike the Egyptian, Syrian, and other North African populations of the Roman Empire that were thoroughly Arabized after their Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD, Persians were able to hold on to their language and calendar even after they converted to Islam. It has been argued that this was made possible because the Iranians' national identity was not fully invested in their pre-Islamic faith. Rather, it resided in a secular body of myth and legend that they preserved and which later would form the basis of Ferdowsi's great work.

To this day men, women, and children in Persianate societies from Asia Minor to China are able to recite lines of Shahnameh by heart. The book continues to be read in family gatherings and performed by professional reciters in the teahouses of Tajikistan, Iran, and Afghanistan.

REVIEW: Abolqasem Ferdowsi, the son of a wealthy land owner, was born in 935 in a small village named Paj near Tus in Khorasan which is situated in today's Razavi Khorasan province in Iran. He devoted more than 35 years to his great epic, the “Shāhnāmeh”. It was originally composed for presentation to the Samanid princes of Khorasan, who were the chief instigators of the revival of Iranian cultural traditions after the Arab conquest of the seventh century.

Ferdowsi started his composition of the Shahnameh in the Samanid era in 977 A.D. During Ferdowsi's lifetime the Samanid dynasty was conquered by the Ghaznavid Empire. After 30 years of hard work, he finished the book and two or three years after that, Ferdowsi went to Ghazni, the Ghaznavid capital, to present it to the king, Sultan Mahmud.

Ferdowsi is said to have died around 1020 in poverty at the age of 85, embittered by royal neglect, though fully confident of his work's ultimate success and fame, as he says in the verse: " ... I suffered during these thirty years, but I have revived the Iranians (Ajam) with the Persian language; I shall not die since I am alive again, as I have spread the seeds of this language ..."

REVIEW: A little over a thousand years ago the Persian poet Ferdowsi of Tous collected and put into heroic verse the millennium-old mythological and epic traditions of Iran. It took him thirty years to write the sixty thousand verses that comprise the Shahnameh or "The Book of Kings." This monumental work begins with legends of the birth of the Persian nationhood and ends with the Arab conquest of Iran. Written in the aftermath of that national trauma, Shahnameh was meant to harbor the Persian collective memory, language, and culture in a turbulent sea of many historical storms.

REVIEW: A little over a thousand years ago the Persian poet Ferdowsi of Tous collected and put into heroic verse the millennium-old mythological and epic traditions of Iran. It took him thirty years to write the sixty thousand verses that comprise the Shahnameh or "The Book of Kings." This monumental work begins with legends of the birth of the Persian nationhood and ends with the Arab conquest of Iran. Written in the aftermath of that national trauma, Shahnameh was meant to harbor the Persian collective memory, language, and culture in a turbulent sea of many historical storms.

REVIEW: Composed in the tenth century by the poet Firdowsi, the “Shah-nameb”, or “Book of Kings”, is Iran’s central literary work, a historical epic peopled with monarchs. Monarchs some of inspiring goodness, others of unmatched wickedness.

REVIEW: A collection of stories and myths from ancient Iran filled with kings, heroes, princesses, magical animals, and demons. Written as an epic poem by the poet Ferdowsi in the 10th century.

REVIEW: Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi, also Firdawsi or Ferdowsi, was a Persian poet and the author of Shahnameh, which is one of the world's longest epic poems created by a single poet, and the greatest epic of Persian-speaking countries.

REVIEW: Retells the ancient Iranian epic poem of the tenth century, and includes tales of the Simurgh, a giant bird who brings an orphaned king into her nest; man-eating snakes; and the great hero Rustam.

REVIEW: A little over a thousand years ago the Persian poet Ferdowsi of Tous collected and put into heroic verse the millennium-old mythological and epic traditions of Iran. It took him thirty years to write the sixty thousand verses that comprise the Shahnameh or "The Book of Kings." This monumental work begins with legends of the birth of the Persian nationhood and ends with the Arab conquest of Iran. Written in the aftermath of that national trauma, Shahnameh was meant to harbour the Persian collective memory, language, and culture in a turbulent sea of many historical storms.

CONTENTS:

-The First Kings.

-The Demon-King Zahhak.

-The Story of Feraydun and his Three Sons.

-The Story if Iraj.

-The Vengeance if Manuchehr The Tale if Sam and the Simorgh.

-The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh.

-Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan.

-The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan.

-Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh.

-Rostam and Kay Qobad.

-Kay Qobad and Afrasyab.

-Kay Kavus's War Against the Demons of Mazanderan.

-The Seven Trials of Rostam.

-The King of Hamaveran, and his Daughter Sudabeh.

-The Tale of Sohrab.

-The Legend of Seyavash.

-Forud, the Son of Seyavash.

-The Akvan Div.

-Bizhan and Manizheh.

-The Occultation of Kay Khosrow.

-Rostam and Esfandyar.

-The Death of Rostam.

-The Story of Darab and The Fuller.

-Sekandar's Conquest of Persia.

-The Reign of Sekandar.

-The Ashkanians.

-The Reign of Ardeshir.

-The Reign of Shapur, Son of Ardeshir.

-The Reign of Shapur Zu'l Aktaf.

-The Reign of Yazdegerd the Unjust.

-The Reign of Bahram Gur.

-The Story of Mazdak.

-The Reign of Kesra Nushin-Ravan.

-The Reign of Hormozd.

-The Reign of Khosrow Parviz.

-Ferdowsi's Lament for the Death of his Son.

-The Story of Khosrow and Shirin.

-The Reign of Yazdegerd.

-Glossary of Names and their Pronunciation.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: The Shahnameh is the great epic of ancient Persia, opening with the creation of the universe and closing with the Arab Muslim conquest of the worn-out empire in the 7th century. In its pages, the 11th-century poet Abolqasem Ferdowsi chronicles the reigns of a hundred kings, the exploits of dozens of epic heroes and the seemingly never-ending conflict between early Iran and its traditional enemy, the country here called Turan (a good-sized chunk of Central Asia). To imagine an equivalent to this violent and beautiful work, think of an amalgam of Homer's Iliad and the ferocious Old Testament book of Judges.

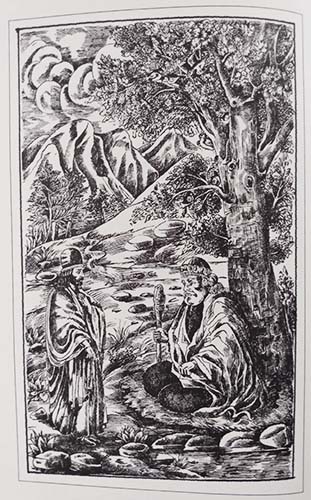

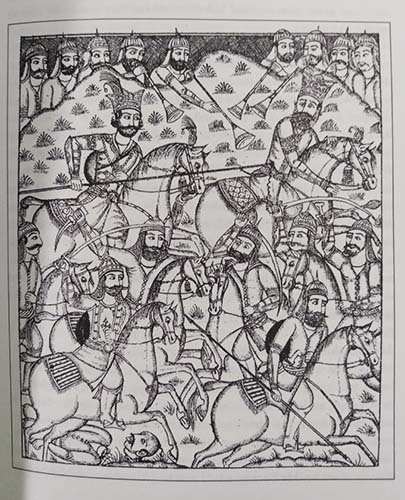

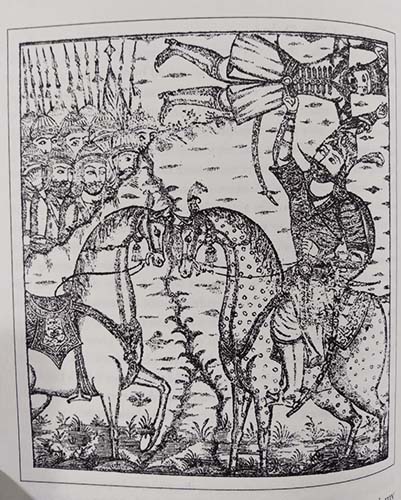

But even these grand comparisons don't do the poem justice. Embedded in the Shahnameh are love stories, like that of Zal and Rudabeh, that recall the heartsick yearnings of Provençal troubadours and their ladies; tragedies of mistaken identity, hubris and irreconcilable moral obligations that might have attracted Sophocles; and meditations on the brevity of life that sound like Ecclesiastes or Horace. Though ostensibly historical, the poem is also full of myth and legend, of fairies and demons, of miraculous births and enchanted arrows and terrible curses, of richly caparisoned battle-elephants and giant birds straight out of the Arabian Nights. Little wonder that artists have often taken its stories as the inspiration for those manuscript illuminations we sometimes call Persian miniatures.

All this is swell, a modern reader is likely to think, but can Americans living in the 21st century actually turn the pages of the Shahnameh with anything like enjoyment? Yes, they can, thanks to Dick Davis, our pre-eminent translator from the Persian (and not only of medieval poems, but also of Iraj Pezeshkzad's celebrated comic novel, My Uncle Napoleon). Davis's diction in this largely prose version of the Shahnameh possesses the simplicity and elevation appropriate to an epic but never sounds grandiose; its sentences are clear, serene and musical. At various heightened moments -- usually of anguish or passion -- Davis will shift into aria-like verse, and the results remind us that the scholar and translator is also a noted poet:

“Our lives pass from us like the wind, and why Should wise men grieve to know that they must die?” “The Judas blossom fades, the lovely face Of light is dimmed, and darkness takes its place.”

“The world is pleasure first, then grief, and then We leave this fleeting world of living men -- Our beds are dust, for all eternity, Why should we plant the tree we'll never see?”

Many of the episodes of the Shahnameh clearly draw from the same teeming ocean of story known to Western poets and mythmakers. Old King Feraydun divides greater Persia into three realms, one for each of his sons, and the two older brothers conspire against the youngest, with bloody centuries-long consequences. The champion Rostam boldly undertakes seven Herculean trials. Kay Kavus's entire army is scourged with blindness by the White Demon. A heroic warrior meets his own Valiant and unrecognized son on the field of battle (English majors will remember this as the subject of Matthew Arnold's poem "Sohrab and Rustum"); Kay Khosrow fasts and meditates, like Buddha, and then renounces the throne and earthly vanity to ascend into heaven. There's even an example of that misogynistic favorite about the high-ranking older woman (Potiphar's wife, for instance, or Phaedra) who lusts after a forbidden younger man, in this case her stepson: "Now when the king's wife, Sudabeh, saw Seyavash, she grew strangely pensive and her heart beat faster; she began to waste away like ice before fire, worn thin as a silken thread." But, as in Racine, Ferdowsi makes us feel the middle-aged Sudabeh's torment:

"But look at me now," she implores Seyavash. "What excuse can you have to reject my love, why do you turn away from my body and beauty? I have been your slave ever since I set eyes on you, weeping and longing for you; pain darkens all my days, I feel the sun itself is dimmed. Come, in secret, just once, make me happy again, give me back my youth for a moment."

The story of Seyavash is a study in conflicting loyalties, like so much of the Shahnameh. The blood relations between Iran and Turan are intricate, as many of the major characters can trace their lineage back to Feraydun, and even traditional enemies occasionally intermarry. In fact, the most common theme of the epic is the tension between fathers and sons, often of kings who don't want to relinquish power and younger men who want to prove they deserve it. Aging Goshtasp can't bear to give up his kingship, even to his own son. So he sends the noble young warrior on an impossible mission: to bring the proud and invincible Rostam back to the court in chains. In truth, there's no good reason for this order, as that hero has long been a loyal defender of one unworthy Iranian king after another. But Esfandyar owes obedience to his father and his sovereign, even as he recognizes the injustice, indeed the senselessness of the command. Worse yet, Rostam admires the young man and so urges every possible escape clause, even agreeing to return to the Persian court -- but not in chains, for he has pledged never to be bound. In the end, two admirable men, caught between mutually opposing vows, must reluctantly meet in armed combat to the death.

Rostam is a recurrent figure throughout the first half of the Shahnameh. He lives for 500 years, swings his mace like a Middle Eastern Thor, and is usually called upon when times grow truly desperate. When young, Rostam searched for a horse that could support his mammoth size and weight. He finally found Rakhsh, as famous in Persian lore as Pegasus in Greek mythology. What, he asks, is the cost of this formidable animal? The herdsman replies, "If you are Rostam, then mount him and defend the land of Iran. The price of this horse is Iran itself, and mounted on his back you will be the world's savior."

Rostam also shares, with Odysseus, a liking for sly humor. Once, on a secret mission to a land of sorcerers, people begin to suspect him of being Rostam because of his great strength. He innocently replies: "I don't know if I'm worthy even to be Rostam's servant. I can't do the things he does; he is a champion, a hero, a great horseman." Another time in battle, he seizes an enemy by his belt, which breaks, and the man escapes. Rostam berates himself, "Why didn't I tuck him under my arm, instead of hanging on to his belt?" The old hero finally dies in a trap constructed by his own stepbrother, but not before he uses his last ounce of strength to notch an arrow and send it through the trunk of the tree behind which the murderer thinks he is safe.

The wily Turanian King Afrasyab is nearly as long-lived as Rostam and somehow manages to escape time and again from certain death. His machinations power much of the first half of the Shahnameh. Afrasyab is nothing if not a Machiavellian realist and one of the most vivid and complex characters in the poem. As a young man, he recognizes the folly of war with Iran's Kay Qobad and so advises his shortsighted father: "War with Iran seemed like a game to you, but this has proven to be a hard game for your army to play. Consider how many golden helmets and golden shields, how many Arab horses with golden bridles, how many Indian swords with golden scabbards, and how many famous warriors Qobad has ruined. And worse than this, your name and reputation, which can never be restored, have been destroyed." He concludes by saying, "Don't think of past resentments, try to be reconciled." The lessons of history, as they say.

There's much more to the Shahnameh than I've touched on here. Because the poem's geography is largely the Eastern empire, Ferdowsi makes no mention of such famous Persian kings as Darius or Xerxes (though Alexander the Great does appear under the name Sekandar). Instead we learn about figures like Bahram Gur, who enjoyed hunting with cheetahs, once killed a rhinoceros with a dagger and eventually thwarted an invasion by the emperor of China.

For all their richness, though, long poems sometimes fall prey to a certain repetitiousness, and the wise reader will want to parcel out this one over time. Yet the epic scale of the book shouldn't overshadow its memorable smaller moments, or even some of its single sentences. One beautiful woman's mouth is described as "small, like the contracted heart of a desperate man." A seductive witch appears to Rostam, "full of tints and scents." A king's three daughters, "as lovely as the gardens of paradise, were brought before him, and he bestowed jewelry and crowns on them that were so heavy they were a torment to wear." As Ferdowsi quietly writes, "So the world went forward, and things that had been hidden were revealed." The Shahnameh eventually concludes with the death of the last king of the Sasanian dynasty and the passing of pre-Islamic Iran. Yet the poet can rightly sing:

“I shall not die, these seeds I've sown will save My name and reputation from the grave, And men of sense and wisdom will proclaim, When I have gone, my praises and my fame.”

Thanks to Davis's magnificent translation, Ferdowsi and the Shahnameh live again in English. [Washington Post].

REVIEW: The Shahnameh, also transliterated Shahnama, is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between around 977 and 1010 AD and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 "distichs" or couplets, the Shahnameh is one of the world's longest epic poems.

REVIEW: This immense volume translates into clear, accessible prose the bedrock work of Iranian literature. Compiled and cast into verse by a tenth-century bard, Shahnameh contains the stories of the kings of ancient Iran before Islam overwhelmed the land in the seventh century. The first half deals primarily with mythical and semi-mythical figures, chief among them the great hero Rostam, while the latter half, beginning with the conquest of Sekandar--that is, Alexander the Great--records historical persons and events. In the concise, informative introduction, Davis calls attention to the entire book's recurrent themes of father-son conflict and contrast between kings and heroes, the latter of whom are nobler in character than the former; indeed, so noble that they invariably decline the throne when it is proffered to them. Davis encourages viewing both themes as reflections of a detached and critical attitude toward formal power and markers of a humane spirit that has allowed the epic to persist as the supreme classic of its nation. [American Library Association].

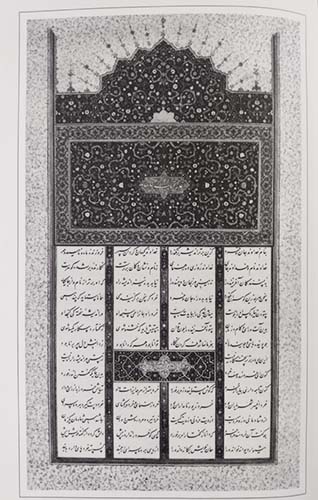

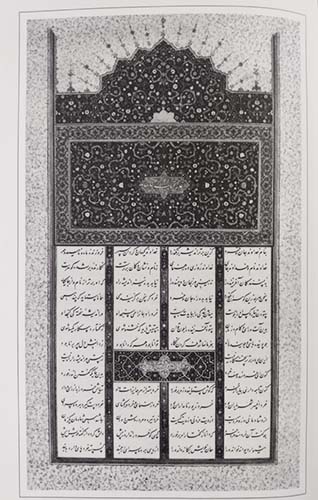

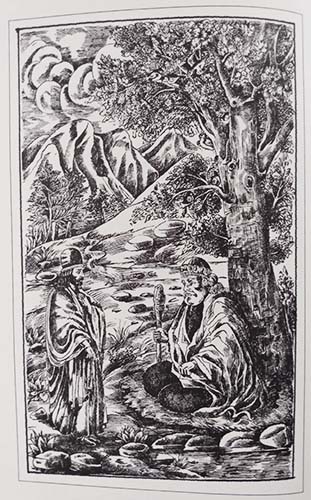

REVIEW: Composed more than a thousand years ago, this national epic of Persia tells the story of Iran from the first "lord of the world," Kayumars, through the seventh-century Arab/Islamic conquest of the Sassanid dynasty. With a foreword by Azar Nafisi, author of Reading Lolita in Tehran, and illustrated with Persian lithographs, Davis's translation of this epic poem is an accessible combination of poetry and prose. [Publisher’s Weekly].

REVIEW: The Shahnameh, Book of Kings, is an epic composed by the Iranian poet Hakim Abul-Qasim Mansur (later known as Ferdowsi Tusi), and completed around 1010 AD. Ferdowsi means ‘from paradise’, and is derived from the name Ferdous. Tusi means ‘from Tus’. In the poet’s case, the name Ferdowsi Tusi became a name and a title: "The Tusi Poet from Paradise".

The epic chronicles the legends and histories of Iranian (Aryan) kings from primordial times to the Arab conquest of Iran in the 7th century AD, in three successive stages: the mythical, the heroic or legendary, and the historic.

Ferdowsi began the composition in 977 AD, when eastern Iran was under Samanid rule. The Shahnameh he produced consisted of approximately 100,000 lines as 50,000 couplets, 62 stories and 990 chapters. It is a work several times the length of Homer’s "Iliad". The Samanids had Tajik-Aryan affiliation and were sympathetic to preserving Aryan heritage.

It took Ferdowsi thirty-three years to complete his epic, by which time the rule of eastern Iran had passed to the Turkoman Ghaznavids. The Shahnameh Ferdowsi produced was written in classical Persian when the language was emerging from its Middle Persian Pahlavi roots. It was written at a time when Arabic was the favoured language of literature. As such, Ferdowsi is seen as a national Iranian hero who re-ignited pride in Iranian culture and literature, and who established the Persian language as a language of beauty and sophistication. Ferdowsi wrote: “the Persian language is revived by this work”.

The earliest and perhaps most reliable account of Ferdowsi’s life comes from Nezami-ye Aruzi, a 12th-century poet who visited Tus in 1116 or 1117 to collect information about Ferdowsi’s life. According to Nezami-ye Aruzi, Ferdowsi Tusi was born into a family of landowners near the village of Tus in the Khorasan province of north-eastern Iran. Ferdowsi and his family were called Dehqan, also spelt Dehgan or Dehgān, which is now thought to mean landed, village settlers, urban and even farmer. However, Dehgan is also a name for the Parsiban, a group of Khorasani with Tajik roots.

Ferdowsi married at the age of 28 and eight years after his marriage – in order to provide a dowry for his daughter – Ferdowsi started writing the Shahnameh, a project on which he spent some thirty-three years of his life. Ferdowsi’s text is centered on the reigns of fifty monarchs (including three women) and can be divided into a legendary and a quasi-historical section.

It begins with the reign of Kayumars at the dawn of time and concludes with the last Sasanian king, Yazdigird (reigned 632–651), who was defeated by the Arabs. These fifty “chronicles” provide a framework for the dramatic deeds and heroic actions of a range of other personages who are often aided by—or at battle with—a host of fantastic creatures and treacherous villains.

The poem draws on a wealth of sources, including local and dynastic histories, the Avesta (the sacred text of the Zoroastrian religion of ancient Iran), and myths and legends preserved in oral tradition. “Our lives pass from us like the wind, and why should wise men grieve to know that they must die? The Judas blossom fades, the lovely face of light is dimmed, and darkness takes its place.”

Over the centuries, foreign conquerors and local rulers alike were drawn to the Shahnaman for its emphasis on justice, legitimacy, and especially the concept of divine glory. Known as Khavarnah in the Avesta and as farr in modern Persian, divine glory was considered the most important attribute of kingship, for it enabled rulers to govern and command obedience.

Not surprisingly, commissioning lavishly illustrated copies of the Shahnama became almost a royal duty. By representing the kings and heroes of the epic according to the style of their own times, members of the ruling elite were able to cast themselves as the legitimate heirs of Iran’s monarchical tradition, which according to Ferdowsi dates back to the beginning of time.

While Ferdowsi was composing the Shahnameh, Khorasan came under the rule of Sultan Mahmoud, a Turkoman Sunni Muslim and consolidator of the Ghaznavid dynasty. Ferdowsi sought the patronage of the sultan and wrote verses in his praise. The sultan, on the advice from his ministers, gave Ferdowsi an amount far smaller than Ferdowsi had requested and one that Ferdowsi considered insulting.

Ferdowski had a falling out with the sultan and fled to Mazandaran seeking the protection and patronage of the court of the Sepahbad Shahreyar, who, it is said, had lineage from rulers during the Zoroastrian-Sassanian era. In Mazandaran, Ferdowsi wrote a hundred satirical verses about Sultan Mahmoud, verses purchased by his new patron and then expunged from the Shahnameh’s manuscript (to keep the peace perhaps). Nevertheless, the verses survived.

Ferdowsi returned to Tus to spend the closing years of his life forlorn. Notwithstanding the lack of royal patronage, he died proud and confident his work would make him immortal.

Ferdowsi wrote the Shahnameh in Persian at a time when modern Persian was emerging from middle Persian Pahlavi admixed with a number of Arabic words. In his writing, Ferdowsi used authentic Persian while minimizing the use of Arabic words. In doing so, he established classical Persian as the language of great beauty and sophistication, a language that would supplant Arabic as the language of court literature in all Islamic regimes in the Indo-Iranian region.

"I turn to right and left, in all the earth I see no signs of justice, sense or worth: a man does evil deeds, and all his days are filled with luck and universal praise. Another’s good in all he does – he dies a wretched, broken man whom all despise.”

The public for their part got to hear verses and legends in Chaikhanas or tea houses and at other gatherings frequented by traveling bards and storytellers – the famed Naqqal. A few erudite individuals would also recite the verses in private gatherings eliciting the approving bah-bah. Shahnameh Ferdowsi was and is also read aloud in the gymnasiums of the Mithraeum-like Zurkhanes – where pahlavans, the strong-men of Iran, train with their maces and clubs. During their meditative exercises that have spiritual overtones, a musician plays a drum while reciting Shahnameh verses that recount the heroic deeds of Rustam and other champions of Iran. The epic itself sits in a place of special reverence within the Zurkhane.

"I’ve reached the end of this great history and all the land will talk of me. I shall not die, these seeds I’ve sown will save my name and reputation from the grave. Men of sense and wisdom will proclaim when I have gone, my praises and my fame." [Welcome to Iran].

REVIEW: Written over a thousand years ago in medieval Iran, Ferdowsi's epic is as important to Persians as the “Illiad” is to Greeks and the “Ramayana” to Indians. Ferdowsi is responsible for safeguarding a collective Persian past, one before the Arab conquests of the seventh century AD, through his collection of Persian myths and legends. Despite the enduring and enormous popularity of the Shahnameh across the Persian-speaking Near East for over a Millennium, it remains relatively unknown and vastly underappreciated in the West.

REVIEW: A little over a thousand years ago a Persian poet named Ferdowsi of Tous collected and put into heroic verse the Millennium old mythological and epic traditions of Iran. It took him thirty years to write the sixty thousand verses that comprise the Shahnameh ("The Book of Kings"). This monumental tome is one of the most important literary works of Iran and like other great epics, such as Gilgamesh, The Odyssey, Nibelungenlied and Ramayana, it is a record of the human imaginative consciousness. It is well known and has been adapted through out the Near East, Central Asia and India but is mostly unknown in the West.

The stories of the Shahnameh tell the long history of the Iranian people. It begins with the creation of the world and the origin myths of the arts of civilization (fire, cooking, metallurgy, social structures, etc.) and ends with the Arab conquest of Persia in the seventh century AD. A mix of myth and history, the characters of Shahnameh take the readers on heroic adventures filled with superhuman champions, magical creatures, heart-wrenching love stories, and centuries-long battles.

Ferdowsi was grieved by the fall of the Persian Empire. Shahnameh was meant to harbor the Persian collective memory, language, and culture amidst a turbulent sea of many historical storms and to preserve the nostalgia of Persia’s golden days. Heroes of Shahnameh are often torn between incompatible loyalties: moral duty against group obligations, filial piety against national honor, etc.

Some Iranian kings and heroes appear in Shahnameh as shining examples of courage and nobility. Others are portrayed as flawed human beings who lose their divine “charisma,” their loved ones, and even their own lives to pettiness and hubris. Ferdowsi stresses his belief that since the world is transient, and since everyone is merely a passerby, one is wise to avoid cruelty, lying, avarice and other evils; instead one should strive for order, justice, honor. truth and other virtues.

Shahnameh has survived as the embodiment of the pre-Islamic Persian soul, but it is much more than a national treasure. As a document of human collective consciousness, it reflects the dilemmas of the human condition as it confronts us with the timeless questions of our existence.

REVIEW: The “Shahnameh”, which literally means ‘The Book of Kings,’ is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi around 1000 AD, and it is considered to be the world’s longest epic poem written by a single poet – it contains 50,000 couplets. The epic can be roughly divided into three parts. The first part tells of the mythical creation of Persia and its earliest mythical past. The second part tells of the legendary Kings and the heroes Rostam and Sohrab. The third part blends historical fact with legend, telling of the semi-mythical adventures of actual historical Kings. The stories throng with heroes and villains, demons and dragons and deeds of derring-do, the book tells the ageless story of the struggle between good and evil.

REVIEW: “Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings” is the great epic of Persia, composed by the poet Ferdowsi between 980 and 1010. It tells the story of pre-Islamic Iran, beginning at the time of the mythic creation through the Arab invasion of the seventh century. Grieved by the fall of the Persian Empire, Ferdowsi sought to create a work that would capture the memory, culture and nostalgia of the golden days of Persia. A mix of mythology and history, packed with stories of triumph and courage, failure and cruelty, love and war, “Shahnameh” can only be compared to works such as “Gilgamesh”, the “Mahabharata”, Homer’s “Odyssey” or Dante's “Divine Comedy”.

REVIEW: A host of heroic characters and wove their adventures into a thrilling story spanning thousands of years. M sure to tighten your seat belts. This experience will take you on a journey back to the world of ancient Iranian heroes, monsters, lovers, and warriors. This is going to be one heck of a ride.

REVIEW: This best-selling book is one of the most sought after books on Shahnameh and Persian culture. It's a beautiful introduction to the cherished epic poetry of Iran. This book will delight the novice and scholar alike.

REVIEW: The “Shahnameh”, also transliterated as “Shahnama” ("The Epic of Kings"), is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between about 977 and 1010 AD, and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 "distichs" or couplets (2-line verses), the “Shahnameh” is the world's longest epic poem written by a single poet. It tells mainly the mythical and to some extent the historical past of the Persian Empire from the creation of the world until the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century.

Modern Iran, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan and the greater region influenced by the Persian culture (such as Georgia, Armenia, Turkey and Dagestan) celebrate this national epic. The work is of central importance in Persian culture, regarded as a literary masterpiece, and definitive of the ethno-national cultural identity of modern-day Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan. It is also important to the contemporary adherents of Zoroastrianism, in that it traces the historical links between the beginnings of the religion with the death of the last Sassanid ruler of Persia during the Muslim conquest and an end to the Zoroastrian influence in Iran.

REVIEW: Composed more than a Millennium ago, the “Shahnameh” - the great royal book of the Persian court - is a pillar of Persian literature and one of the world's unchallenged masterpieces. Recounting the history of the Persian people from its mythic origins down to the Islamic conquest in the seventh century, the Shahnameh is the stirring and beautifully textured story of a proud civilization. But the Shahnameh (or, literally, the 'Book of Kings') is much more than a literary masterpiece: it is the wellspring of the modern Persian language, a touchstone for Iranian national consciousness and its illustrations, in manuscripts of different eras, are the inspiration for one of the world's greatest artistic traditions

REVIEW: The Shahnameh, an epic poem recounting the foundation of Iran across mythical, heroic, and historical ages, is the beating heart of Persian literature and culture. Composed by Abu al-Qasem Ferdowsi over a thirty-year period and completed in the year 1010, the epic has entertained generations of readers and profoundly shaped Persian culture, society, and politics. For a Millennium, Iranian and Persian-speaking people around the globe have read, memorized, discussed, performed, adapted, and loved the poem.

REVIEW: "Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings" is the timeless masterpiece by the Persian poet Ferdowsi. The epic poem, believed to have been written between 977 and 1010 AD, tells of the mythological and historical past of Persia from the creation of the world up until the Islamic conquest of Iran in the seventh century. The "Shahnameh" is a captivating story of an ancient world and details much of early Persia's history, culture, and Zoroastrian religion. The poem, consisting of over 50,000 couplets, or two-line verses, is a work of great importance in Persian culture and helped shape the development of the modern Persian language. The poem is regarded as the national epic and symbol of Iran and is celebrated in many areas that were once a part of the ancient Persian Empire, such as Afghanistan, Turkey, Armenia, and Georgia. The lyrical account of Persian history in "Shahnameh" has had a profound influence on Persian literature and the work is referenced in the timeless love poems of Rumi and Hafiz. "Shahnameh" endures as an important historical record of an ancient people and a beautiful and poetic celebration of the Persian culture.

REVIEW: An Iranian epic for the masses [CNN International].

REVIEW: A Persian Masterpiece, Still Relevant Today [The Wall Street Journal].

REVIEW: Immerse yourself in the distant past with this epic poem from the Persian tradition. Penned more than one thousand years ago by the famed poet Ferdowsi. The “Shahnameh” weaves history and myth into a lyrical, action-packed work of art that you won't be able to put down. This book is a must-read for folklore connoisseurs.

REVIEW: Brings new, vivid life to the epic tales of the ancient Persian kings [The Atlantic].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: This book is about the lineage of Persian Kayanid Kings and the Persian House of Sasson. With that lineage comes an evolving philosophy of man's thought from the perspective of justice and injustice. It begins in a mythological setting and then over time evolves into a story that may have taken place in the time when Persia was great, concluding with the triumph of Islam over Persia. Through out the mythological portion of the book the author explores the concepts of what is observable reality (good, god) and contrasts that with unobservable conjecture or sorcery magic.

While the lineage progresses through many kings, it is when you read of King Ardesher that you sense you are reading ancient history rather than myth. The subtle clues would be when Ferdowsi describebes the king writing a letter in Palhavi, an ancient language. It is here that Ferdowsi begins the practice of dedicating whole chapters to one king's reign. Every king has a vizier and a champion. Through these intermediaries the thought process borne in conversation brings the king to order just or unjust deeds reveals the prevailing philosophy.

The lineage of Kayanid Kings of the House of Sasson begins with quick summaries of names from the family Kayumars beginning with Siamak who is killed by a black demon, and then Hushag's victory, where the Kayumars pursue and kill the black demon. This fast moving chronology leaves Hushag to inherit the crown, as he is the one with the royal farr and the presence of a tall cypress tree who can think with clarity, all prerequisite to inheriting the throne. The primary way in which the Persian kingdom expanded was through a sitting King doling out frontier land to his sons. In the beginning one son received Yemen, which would be today's Middle East.

Another received land in India, which would be today's Afghanistan, and Pakistan and the third Turan, which would be today's Turkmenistan. Feraydun's reign was the first to go into a bit more detail. The author does this so that he can introduce the concept of a dark magic that clouds the mind of one who feels cheated. A cheated mind draws on vengeance. The brothers that were ruling Turan and India felt they did not get the favored Persia and plotted to and did kill the son who received Yemen. King Feraydon through his champion Zal who is blessed by the Zoroastrian Angel Smiorgh avenges the evil acts of his other two sons.

The early kings of Persia had much in common with early Arab kings and hence the family tree found relatives of mixed royal blood and the two peoples were very close, while rule still came from Persia. As Persia expanded its reach into India, China, and Turkmenistan they too came under the influence of Persia's King of Kings. All gains of kingdoms came either through war, marriage or the giving of a daughter. As the family cypress tree branched the lineage of kings became difficult to track.

To garner the philosophy conveyed in this book, the reader need only to pay attention to the dialogue between warriors, or between a king and his vizier. In a reign of a king that expands or contracts finds in each battle the combatants making declarations towards the other as to why he shall prevail in the contest. For an example one of the notable champions, Rostam declares to Gorgin ...please to a keyword search for cigarroomofbooks.blog to read of my insights on the book and to share your opinion.

REVIEW: Instead of translating the poetic original, the translator, Mr. Dick Davis, wisely chose to use the storytellers' version and only sprinkling occasional poetry for emphasis and flavor. It makes for easy reading for foreigners but still conveyed the essence of Persian culture. I have always wondered why Shahnameh is considered by the Persians/Iranians as their national epic even though the mythical period took place in Central Asia and Afghanistan with no mention of the traditional Persian origin or the Achaemenids until Alexander showed up.

Mr. Dick Davis explained that the poet Ferdowsi was writing for the Samanid shah who ruled only in eastern Iran. Besides, the Samanids claimed descent from a Parthian general who started his career in Khorasan and Tranoxiana and later even briefly claiming the Sassanid throne. As the epic was an assertion of national identity, it ended at the end of the Sassanid dynasty when the Arab conquest incorporated Persia into Dal al Islam. Since this is the Book of Kings, it began with the first king. The early mythical kings were the ones who taught the people the necessary skills for the development of civilization.

Following the Zoroastrian tradition and Islamic belief, the conflict of good and evil started early and remained front and center. But right and wrong were drawn along the tribal lines as one could always justify his action by claiming the enemy was a demon. And a man's worth was measured by his strength and valor. To this day, strong men and wrestling champions are still highly esteemed in Central Asia. As the world was still small, everything to the west was Rome, everything to the east was China, everything to the south was India, and there were only demons in the north.

The quarrels of the feuding princes explained the historical hostilities between the Iranians of Persia, the Turks from Transoxania, and the Greeks of the West. Since angels and demons and magical creatures lived among men, it's not surprising that some men lived hundreds of years. That's one of the reasons why the great Rostam was able to accomplish so many fantastic heroic feats. There were even some love stories and one had hints of Rapunzel and the Firebird. While the heroic house rose in Sistan, the royal house degenerated into chaos. Right and wrong were perverted and vengeance became the main theme as China and India were drawn in.

To transition from myth to legend, Ferdowsi borrowed the ancient Akkadian story of Sargon the Great for Darab and had him rescued from the Euphrates. Of course Darab turned out to be the secret heir to the Persia royal house. After defeating the Greeks, Darab had an unacknowledged son by the daughter of the Greek king Filqus. This son just happened to be Sekandar. After abandoning the Greek princess and her son, Darab went home to civilization and had a legitimate son Dara by a proper wife.

Because Sekandar the Greek was now the first born son of Darab, his conquest of Persian, though still a disaster, was no longer shameful to the proud Persians. Thus, Persia's national pride was restored. But, strangely, the Greeks were already Christians and Sekandar's title was Caesar. After he made a pilgrimage to Abraham's house in Mecca, he visited the queen of Andalusia and the emperor of China. He then travelled the world and had many fantastic adventures reminiscent of Sinbad's voyages. Creative license indeed!

Legend finally yielded to history and five generations in the story covered five hundred years in history thus conveniently skipped over the Greek Seleucid dynasty and the Parthian Arsacid dynasty and jumped right into the Persian Sassanid dynasty. To legitimize his rule, Ardeshir claimed descent from the Achaemenids. Here, he was transformed into a descendant of the Kayanids for the same reason. This being such a long epic, some stories began to repeat themselves. As Sassanid was a Zoroastrian dynasty, astrologers predicted everyone's fate and the chief priest functioned as chief advisor.

In an increasingly centralized society where the kings held absolute power, the degree of violence and brutality also increased. However, right and wrong were still subjective. When a Persian king committed horrendous atrocities against his enemies, he was hailed as a great just king. But when he did the same to the Iranians, he was cursed as an evil unjust king. Bahram Gur became the idealized king on whom was hung the dreams and fantasies of the lost golden age. Somehow, the emperor of China had become the lord of Turan and the people of Central Asia became known as Chinese Turks.

Then Khosrow Parviz and Shirin's love story was elaborated by later poets into one of the most beautiful love stories in Persian literature. As no empire can be conquered without it being corrupt from within first, the fall of the Sassanids, in my opinion, was due more from the chaos and splintering after the death of Khosrow Parviz than from the Arabs' religious zeal. As Shahnameh keeps telling us, fortunes change as the heaven turns and nothing lasts forever in this fleeting world.

Unfortunately, by the time Ferdowsi finished his epic, the Samanids had been replaced by the Ghaznavid Turks, the bad guys in his Shahnameh. Poor Ferdowsi had to find refuge in the home of a Sassanid descendant. Fortunately, Persians/Iranians, seeking their pre-Islamic heritage, took up the tales and kept them alive. As the saying goes, "Why let the facts ruin a good fiction?" In a world of oppression, larger than life heroes and bigger than reality fantasies are what people need to brighten their dreary days and give them hope. That's why the stories of Shahnameh have become immortal.

REVIEW: Time is beneficial when reading this one. I originally started this July 2017 and am now finished December 2018. That would be a year and a half spent with this book. And it's so incredibly appropriate because this book is a chronicle of Persia's history told through the lineage of its kings.

This book begins with the Persian creation story with all of its absolute wild, unpredictable magical elements. The early stories contain magic and mythological creatures. I'm sure if you grew up with classic Western Fairy tales, there's one that will shock you: 'Western writers stole that idea from here!' Trust me, once you read it, it's unmistakable which one I'm referring to.

The bulk of this amazing book are traveling, letters, battles, marital allegiances, powerful women and the men who fail to take the solid advice of their ladies. Some of the battles are pretty exciting to read when the dust rises up and we lose sight of who's winning. Other battles and shifts of kingly power are difficult to follow because anytime you condense 1000's of years of history into 900 pages, there's going to be A LOT of names mentioned with how they all relate to each other. Don't fret though, just read on.

Dick Davis' language sings all through Persia's history. His approach to task is fantastic. He condenses each of the original books. The original length is a collection of encyclopedias of course. So he's vey systematic about what he includes and how he showcases some of the more poetic scenes. In his introduction, he admits to leaving out some offending passages that newcomers to Persian literature could be turned off by. Instead, he evens out the coverage of many kings which is a slight change from the original author, Ferdowsi's approach. He does this to give a more comprehensive coverage of the original book within a limited number of pages. Some kings still receive a whole lot more attention and this reflects the original.

What I appreciate most of all with Davis' translation is he renders this epic poem into a highly readable edition for those completely unfamiliar with Persian Literature or even the culture of this entire world and its history. It doesn't read like a beginner's book, there's still plenty of complexity to keep the most avid reader busy looking up references for a few years at least.

For those poetic scenes, often they are key moments in the story that I'm sure Persian folks know well and love. Davis kept them in poetic language with meter and rhyme. These are some of the most beautiful parts of the book and makes me want to read a poetic translation of The Shahnameh. Not only because they are emotionally driven scenes but also because Davis writes like a poet.

Here's an example from near the beginning. This brief poem describes the birth of Rostam, the greatest hero in this book. And one of the coolest characters I've read during my epics project so far.

"He'll master all the beasts of earth and air, He'll terrify the dragon in its lair; When such a voice rings out, the leopard gnaws In anguished terror its unyielding claws; Wild on the battlefield that voice will make The hardened hearts of iron warriors quake; Of cypress stature and of mammoth might, Two miles will barley show his javelin's flight."

This could be a great book if you enjoy epic long tomes filled with adventure, complex who's who, some mythological elements, history and some references to writing as it's developing throughout history with plenty of battle scenes and some romance mixed in. Keep in mind, it's 900 pages with almost constant warfare, so it's certainly not for everyone. The shifts in power and keeping track of who's who and why they have a grievance was the most grinding aspect of this read. The battles certainly were not grinding to read for some reason.

REVIEW: What Nöldeke called the iranische Nationalepos (the Iranian national epic), Ferdowsi's Shahnameh ('King-book') is the basis of Iranian identity. Based on an older prose translation of an earlier Middle Persian King-book but recomposed by Ferdowsi into verse, the Shahnameh in over 50,000 lines tells both the tale of the mythical past of Iran and its pre-Islamic history from Alexander till the fall of the Sasanian emperors, whose exploits are recast into an epic romance.

The middle section, the heroic age, contains the most celebrated part of the epic, the tale of the exploits of Rustum (the foundation, amongst many other things, for Matthew Arnold's Rustum and Sohreb: an Episode).Dick Davis' book here is the most complete one-volume translation in English.

His translation is prose; on occasion, however, he moves to a verse translation to reflect specific lyrical passages. His translation is considerably less condensed than most other English translations. I strongly urge the reader to obtain the Viking hard-back rather than the Penguin paperback. For a book of this size, the hard cover is worth looking out for.

REVIEW: This book is about a thousand years old and was written by Iran's seminal author Ferdowsi. Although he was a Muslim, his interest lies entirely in pre-Islamic Iran, which he sees as a true heroic age of marvelous deeds by wondrous men and women. As in all epics, the interest here centers around ancient military encounters, but Ferdowsi turns his semi-mythical wars into short segments of tremendous dramatic power. He almost invariably shows us how virtue in leadership is rewarded and vice in leadership brings disaster down on the heads of tyrants, so there is great moral satisfaction in following his narratives, which span centuries of Iranian mythical history.

Though I have absolutely no knowledge of the Persian language, my sense is that the translator, the Englishman Dick David, who is certainly an accomplished poet in his own right, strove to present Ferdowsi's words in the truest possible way. Be warned that this book is very long, but to my mind all the way through it was a near-blissful experience. We are blessed to possess this sublime work of art from the great Persian past, which provides us with a much-needed counterweight to the sordidness of the Iranian present.

REVIEW: This is perhaps the greatest collection of stories I have ever read! It is a true "dream book"; if you love wonder stories, myths and heroic epics this is the kind of saga you dream about. Every story is better than the one preceding it and it keeps mounting until it reaches heights of imagination and storytelling that are all but untouchable. As in Persian poetry the language is rich, layered and achingly beautiful. It is basically a long family saga but it never gets too complicated to follow. A perfect book: humanizing, imagination-expanding and a towering work of literature.

REVIEW: My literary travels around Iran continued this month with Shahnameh, and boy was it a long trip. Clocking in at 854 pages (not including glossaries and indices), it took me nearly a month to read, and not for lack of interest; the stories are, for the most part, fascinating. Originally my plan was to sample stories from Shahnameh to get an idea of Persian mythology. Shahnameh is roughly the Persian equivalent of The Odyssey or Beowulf, covering stories of Persian heroes and historical events. Unlike Western epics, however, it does not focus on one hero, but chronologically explores the reigns of Persia's kings from roughly 600 BC to the Arab invasions of the 7th Century AD. 1300 years is quite a lot to cover, even in 854 pages, and the translator, Dick Davis, still chose to leave out what I'm guessing are the really boring parts.

The translation is well-written and intriguing, but not entirely in verse (unlike the original). Davis chooses select portions to commit to poetry, using prose for the majority of the text, and this was fine with me. It made for a quicker read while dealing with the essence of the story. I loved the early stories the best, those about Sam, Zal, and Rostam, the epic heroes on par with Achilles. Rostam in particular is a legendary warrior (not a Persian king) whose trials and travails keep the Persian nation safe and secure from the various invading forces. And boy, was Persia invaded a LOT.

REVIEW: I am not so presumptuous as to review the Shahnameh. Does one review Shakespeare or Augustine? But I will comment on Dick Davis' excellent translation. Some people complain that it's written in prose; others complain that it's written in poetry. Yet the magic of this translation is the incorporation of the two. As he says in the introduction, Davis' goal is not to faithfully reproduce the tens of thousands of lines of poetry that took Ferdowsi 30 years to write. Rather, he opts for a combination of prose and poetry that emulates the way that the Shahnameh is most often performed in a style called "Naqqali". Basically, Davis is presenting the poem to us in the way that uncounted Iranians have received it for hundreds of years -- don't complain!!

REVIEW: Who am I to rate or review Abolqasem Ferdowsi's ancient and classic Shahnameh, The Persian Book of Kings? Since I only know a smattering of Persian, nor can I comment on Dick Davis' translation from the original into English, which I have heard is excellent, but cannot verify. This is a volume which I dip into and will still be doing so in the years ahead, so I will take it from my currently reading list even though I am halfway. It is fascinating and I am enjoying it but that is not the only reason to rate a book. The scope of the original Shahnameh is huge: it covers 700 years of the history of Persia from creation to the Arab conquest, written in verse, in nine volumes. If it needs rating at all, it would be presumptuous to give less than five Stars.

REVIEW: The Shâhnameh recounts the history of Iran, beginning with the creation of the world and the introduction of the arts of civilization (fire, cooking, metallurgy, law, etc.) to the Aryans and ends with the Arab conquest of Persia. The work is not precisely chronological, but there is a general movement through time. Some of the characters live for hundreds of years (as do some of the characters in the Bible), but most have normal life spans.

There are many shahs who come and go, as well as heroes and villains, who also come and go. The only lasting images are that of Greater Iran itself, and a succession of sunrises and sunsets, no two ever exactly alike, yet illustrative of the passage of time. The Shahnameh is largely his effort to preserve the memory of Iran's golden days and transmit it to a new generation so that they could learn and try to build a better world. Ferdowsi started his composition of the Shahnameh in the Samanid era in 977 A.D and completed it around 1010 A.D. during the Ghaznavid era.”

REVIEW: Well, it's been a while since I tackled this bad boy, and what a big boy it is. Picture this: you're a poet, you're Zoroastrian, it's about 1000 years after this Christ fellow (whom you don't know) got to meet his maker (curiously, himself), and you decide it would be a good idea to record the complete history of the great Persian empires whose final vestiges has been overrun by those pesky Moslems. Oh yeah, and it takes you thirty years to write it. There is a reason it is a cornerstone of Persian literature.

This is a national epic covering thousands of years of myth and history, beginning with the creation of all things, the building of various empires, rollicking adventures, the occasional romance, and a final, crumbling decline into subservience. There is so much in here you could just have it sit on your shelf and pick and choose portions to read as you please, a huge treasury of tales. Or, you could be a glutton of punishment like me and decide to read it from beginning to end. The cycles of inheritors to great kingdoms being abandoned, growing to maturity, and taking back their kingdom by strength can become repetitive if you read it this way. It probably took me three months. I'd recommend just reading sections at time so you can get a flavor of the times. It's well worth it for armchair time-travelers.

REVIEW: I really love this book. I am not Persian. I don't speak Farsi. I am just a curious reader who couldn't help but dive into legend! The original Shahnameh was composed in poetry. This translation is prose with very important or dramatic parts done in poetic rhythm. Dick Davis did this to mimic the way the stories of The Shahnameh would have been told orally. Translating it in this way just makes the stories beg to be read aloud. He has made The Shahnameh really approachable and fun to read. I would highly recommend this book for young adults and adults to read. The stories would be wonderful bedtime tales for children as well! If you love legend you must get this book.

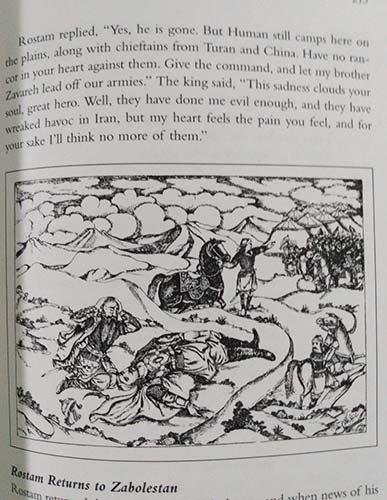

Don't forget to read the introduction! It provides insight into Ferdowsi, Persian history, and important themes within the legends. The only downside to this edition is that the illustrations are few and only in black and white. My suggestion is to get this edition to find your favorite stories. Yes, this is a HUGE book. It was a bit intimidating to pick up. Luckily, the stories are short and there are plenty of places to put your bookmark. I often read one or two stories in a sitting and find that the timing was just right. Get this book!! :-D

REVIEW: Shahnameh is a poetic form rarely appreciated. It's an epic, it's storytelling, it's history, politics, myth, and religion. Ironically it stands as a stark counterpoint to today's poetic ethos of word economy, in which modern poets can sum up a universe in a hundred words.

Shahnameh stands, as translated here, at over 850 pages, possibly the longest poem ever created. Dick Davis' translation seems lacking in the ornamental nature of poetic language, and possibly the Persian language, but is likely true to the original's context. He does grace his prosaic pages occasionally with delightful quatrains to remind us that this is poetry, that its origins belong to the oral tradition, that it once beguiled as song.

Few will read this tome to completion, and that's a shame in a time in which we in the west need a better understanding of what was once one of the planet's most ascendant cultures, one that has influenced ours in more ways than we probably care to imagine.

REVIEW: This collection of interesting myths and history explains the Persian "thing." In other words, if you like reading stories from other cultures about how here and now became here and now, then spend some time reading this book. It is a big book full of fascinating narratives detailing the development of civilization in ancient Persia until the Arabic invasion. It is entertaining and more intellectually mature than it first appears. They may be myths, but the human condition in victory and defeat is written out in a way I have never seen before. It is a surprising book.

REVIEW: This book is an epic in every sense. While Ferdowsi may never have received just payment for this work, his name and this book have been remembered for over 1,000 years, and that is a legacy that writers can only dream of - to produce a book that stands the test of time. The stories told also provide life lessons, which can be learned from.

REVIEW: To me, it's a marvelous sense of nostalgia, because my father was reading Shahnameh with his interpretations as my bedtime stories once I was 4-5-year-old. I know many of the original lines in Persian from school and my dad's voice, and now it's interesting to read it from another perspective as an English reader. Though the translator omitted the splendid Ferdowsi's creation myth at the beginning, and many modern translators did the same, but I think he really did a great job describing the Book of Kings!

REVIEW: Davis's translation is clear, dramatic, and well condensed, with a smattering of brief summaries for the less important segments. The story is absolutely enormous -- rivaling the Bible or the Mahabharata in scale and length. And like the Bible, it is full of surprises for those expecting orthodox traditionalism. One surprise is the number of powerful women. Another is the celebration of free and rebellious love affairs. A third is the open disdain for the Arab conquerors who brought Islam. But the thing that most surprised me is how this ode to heroic kings turns into an orgy of battles for power, until the whole notion of kingship starts to seem repulsive. It's a national epic with lots for future generations to draw on.

REVIEW: This is a fabulous chronicle of thousands of years of Persian History BEFORE Islam triumphed over the last dynasty. Written entirely in verse, the magical co-operative been turned into prose for western readers but the majesty of Ferdowsi's verse never fails to entertain and inform. The most remarkable history i have ever read. Give Stars are not enough- -heaven itself has opened and spilled out this volume of jeweled words through the inspired verse of this ancient bard. Read this and your understanding of this world will expand, as well as your appreciation of this magnificent life we all share!

REVIEW: 'The Book of the Kings' is the national epic of the Persians. No other work captures so much of the history, culture, or identity of one of the greatest empires in history. This is a must-read for any student of Middle-Eastern history, of mythology, or any person who appreciates a national epic for what it is: the one work that perfectly captures who a people are in a medium no less powerful than a flag or national anthem. The English have 'Beowulf', the Italians 'La Commedia', the Romans 'Aeneid', the Greeks 'The Iliad/ The Odyssey'... 'Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings' is the one and true epic of the Persian people. It must be read by anyone who wishes to appreciate their culture.

REVIEW: The epic is greater than life - and the translator combines rare expertise with beautiful poetic language, and thus conveys some of the heroic spirit of the original. The choice to translate from the NAKL version, which is partly prose, can be debated, but it's certainly legitimate. And the result is amazing. If you're interested in myths, legends, Persian culture or even if you want to understand an important edifice in modern Iranian culture, read this book.

REVIEW: Go out and buy this book now! It is a wonderful compilation of Persian legends and the back-stabbing that princes do to those who support them "too much"! Comparable is some ways to The Golden Bough combined with Arabian Nights, the stories related in this superb book are totally unknown by Western readers, which makes them delightful, if occasionally gruesome. Davis' translation is a master work, somehow infusing prose with the kind of poetry myths require. A window into the soul of Persia, perhaps especially relevant now.

REVIEW: I love this book and it was very useful for my grad research project. The translation is perfect and the book captures the elegance and grace of Ferdowsi. It is worth reading for any person and I wish that someday, this epic poem will be made into a miniseries for TV so even more people can enjoy this story.

REVIEW: This marvelous translation of the Shahnameh has resulted in a book that is accessible and readable. Dick Davies has managed to translate key passages into rhyming poetry, but the majority is well-written prose. He has omitted some repetitious passages to keep the length reasonable (around 850 pages) and to avoid testing the endurance of the general reader. This intelligent translation has succeeded in making the 10th Century epic accessible to the modern general reader..

REVIEW: One of the most significant historical works to come out of the Middle East. Ferdowsi is a classic writer and poet of Persia. His works are still praised and followed in Iran today by the better educated among the populace.

REVIEW: The Book of King is the book that helped Iranians to get through all the invasions to their country in the past 1,000 years. It is a must to read book.

REVIEW: Great read if you have any interest in Persian culture, full of lively wonderful stories. Considered to be a Persian classic.

REVIEW: Had Freud known about the book of kings, his analysis of human psyche would have been enhance and could possibly have been different. I bought seven copies for gifts. Monumental work. Good translation.

REVIEW: Beautiful poetry and story telling transporting the reader to far away places.

REVIEW: Yes, a great epic history in easily understandable English, the translation offers a good insight into Persian culture and storytelling.

REVIEW: This is the newest translation of the famous Persian Book of Kings. Davis brings some great insight in from the original as much can be lost in translation. Love it, be aware it's very long, but a great addition to any family library or Persian buff.

REVIEW: I love the book since I was raised hearing the stories from the book. I haven't had a chance to read the entire thing cover to cover but having this book translated into international language makes the treasure everlasting.

REVIEW: I love Firdausi's Shahnameh and all the time, but my wife couldn't read Farsi, so I decided to get this book that she could enjoy the book with me. Nice book and I will recommended to any one.

REVIEW: Great book! Need to read couple times to get all the characters. Very interesting book to read about Persian kings.

REVIEW: I had been trying to buy this book for past three years. It is an expensive book to buy and to add to my library. It worth every penny because it is about Iran's heritage. The story line with would be battle of Good versus Evil or the Fellowship Series. Buy it and keep it because these are limited edition and Mage won't publish it anymore.

REVIEW: As someone who was familiar with some of the stories of Shahnameh, I found this translation to be a fascinating read. I recommend this book to those who are interested in Persian history and mythological stories. The author does some justice to the great poetry by Ferdowsi by including English poetry of the same sort of style in some parts of the book.

REVIEW: Amazing book. Easy to read and understand. The book is mostly written in prose. It’s a great book for anyone who wants to start learning about Persian culture.

REVIEW: Loved it. Can't understand a culture till you understand their mythology and the Shanameh is fundamental for understanding Persians in a way that the Wild West and pioneer spirit makes up American culture.

REVIEW: You will be enriched by your encounter with one of the great war epics of world literature, a work which occupies the same exalted status in Islamic culture that the "Iliad" and the "Aeneid" occupy in Western culture. And aren't we Americans past due in appreciating Iranian culture in particular, considering our 21st century karma has inextricably entwined the fates of our two societies? In today's world cultural literacy involves a knowledge of the literature of the world of Islam. This version of one of the seminal works of Persian literature can provide that knowledge.

REVIEW: Wikipedia says Ferdowsi wrote this between 977 and 1010. It portrays Iran from earliest time until the Islamic conquest in the seventh century. The only religion mentioned in it is Zoroastrianism. The translation/adaptation is a mix of prose and poetry, although my extracts here only quote the infrequent poetic pieces. Ferdowsi’s original consists of 50,000 couplets. As in the Bible, some people live for hundreds of years, while others age and die around them. There are fairies and demons, although in this adaptation humans are by far the main characters.

I’m not going to try to summarize the Wikipedia commentary of the Shanameh’s importance in Persian history, language and literature here; but learning about the role of the poem would be well worth while. At first the names and genealogy go by at dizzying speed, but the story settles in to a tale of three of four generations of two main families in Persia and a handful in Turan, to the northeast of modern Iran (Turkmenestan).

This is the national epic of Iran, the stories all children presumably hear from infancy. They also hear beautiful prose and poetry, and they hear about heroes who try to cauterize the last emotional wounds and stop the cycle of revenge. "False confidence leads a foolish man to slaughter. He stomps on solid ground but it turns out to be a layer of straw floating on a puddle of water."

At a deeper level, there is an epic story of dynasties and political negotiations about what kind of government will prevail. Ferdowsi is also an incredible psychologist. His kings and warriors are always in flux between their impetuous impulses and reflective wisdom. "The world is full of mysteries as it makes and breaks. Love and wisdom forsook them both, nor did one of them pause to correct his mistakes. Fish, onager, and beasts of burden in their mangers know their own, but greed so blinded father and son that they faced each other as strangers."

He portrays many of the early kings of Persia and weak or disastrous rulers, who embroiled their countries in unnecessary wars and were vindictive or unappreciative of the brave defenders. Other rulers, however, were upright and wise, and fostered art, science and justice. There is a touching story of one king at only sixty years old, worn down by his duties, climbing a mountain in winter to die, disappearing, and the heroes who accompanied him against his counsel dying in the blizzard as well.

One gets a sense of the different cultural background of simultaneous political and military leaders and dynasties that I read as a very old tradition that may be a source of the later approach to the very different scopes of political and religious rule, when compared to the modern West. Just a guess.

Women are not omitted. There is a story that is very close to the Greek "Phaedre", with disastrous results. Other women are mothers with wise advice, beautiful daughters and brides, and brave widows committing mass suicide to avoid capture as war booty. Horses are just about as important as lovers. As the supreme hero Rostam is finally returned in state to his city after a gruesome death by treachery at the end of the work, his faithful horse is treated to the same honored trip via a bejeweled platform on an elephant.

"Magnificent buildings decay by the dint of time and exposure to the elements wrecks even a house of flint. But the poetic edifice I have erected in rhyme shall endure the contagion of the rain and the sun. For three decades have I thus suffered to restore this Persian tongue and now my work is done."

REVIEW: I bought this incredible book on Amazon a few weeks ago. One must be a poet to even attempt the great Persian epic of kings, the “Shahnameh”. When I lived in Iran as a teenager in the 1970s, I would occasionally bumble into a bar or teahouse and quite often there would be a man reciting and acting out something to the rapt attention of the crowd, everyone except me that is, the long-haired faringi boy looking for kebab and chai. I had no clue what was going on but it was most certainly the "Shahnameh".