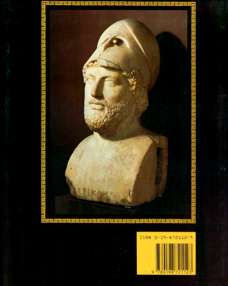

The Oxford History Of The Classical World by John Boardman, Jasper Griffin, Oswyn Murray.

DESCRIPTION: Illustrated hardcover w/dustjacket. Publisher: Oxford University Press (1986) 882 pages. Dimensions: 9¾ x 7½ x 2 inches; 4½ pounds. The history, achievements, and enduring legacies of Greek and Roman antiquity come to life in the pages of this comprehensive and beautifully illustrated volume. Following a format similar to that of “The Oxford Illustrated History of Britain”, the book brings together the work of thirty outstanding authorities and organizes their contributions into three main sections.

The first section covers Greece from the eighth to the fourth centuries B.C., a period unparalleled in history for its brilliance in literature, philosophy, and the visual arts. The second section deals with the Hellenization of the Middle East by the monarchies established in the areas conquered by Alexander the Great, the growth of Rome, and the impact of the two cultures on one another. The third section covers the foundation of the Roman Empire by Augustus and its consolidation in the first two centuries A.D.

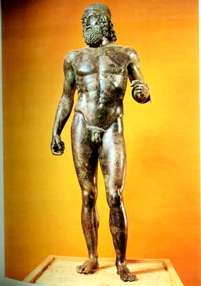

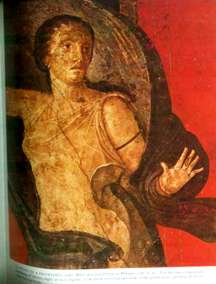

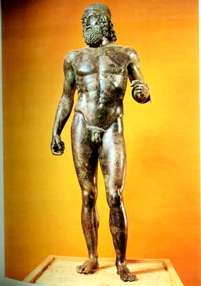

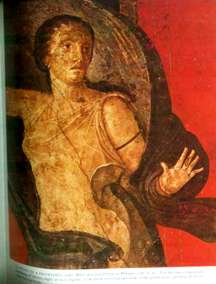

A short concluding essay discusses certain aspects of the later Empire and its influence on Western civilization, notably through the adoption of Christianity. Within each section, chapters dealing with political and social history alternate with chapters on literature, philosophy, and the arts. Maps and chronological charts--not to mention more than 250 illustrations, including sixteen in color--enrich the basic text, along with bibliographies and a full index.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. Essentially unread (albeit mildly shopworn) hardcover w/dustjacket (in new acetate sleeve). Oxford University (1986) 882 pages. Looks like someone read perhaps the first 20-30 pages of the book, perhaps flipped through the rest of the book looking at pictures, then put the book away never to be taken down and actually "read through". The dustjacket and quarter cloth covers do evidence mild edge and corner shelfwear. From the inside the book is virtually pristine; the pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, seemingly only flipped through a few times, excepting that the first 20 pages or so do evidence mild reading wear. Shelfwear to dustjacket consists of mild edge and corner shelfwear, principally composed of modest crinkling to the dustjacket spine head and heel, modest abrasive rubbing to the top "tips" of the dustjacket (the top open corners of the dustjacket, front and back), and fainter rubbing to the lower corners. There is a very small (1/4 inch) closed, neatly mended edge tear to the dustjacket spine head. We carefully repaired the closed edge tear from the underside of the dustjacket, and touched it up with an oil-based sharpie. Consequently it is not a prominent blemish (in fact it is hard to spot even when you know it is there). We placed the dustjacket inside a new acetate (clear plastic) sleeve so as to enhance its appearance and to protect it against further shelfwear. Beneath the dustjacket the quarter-cloth covers are clean and unsoiled, evidencing only very mild edge and corner shelfwear. Except for the edgewear to the dustjacket, and the fact that the book has clearly been flipped through a few times (particularly the first 20 pages or so), the overall condition of the book is not too far distant from what might pass as "new" from an open-shelf book store (such as Barnes & Noble) wherein patrons are permitted to browse open stock, and so otherwise "new" books are often a bit "shopworn" exhibiting evidence of having breen browsed, as well as modest shelfwear and/or cosmetic blemishes the consequence of routine handling, and simply being repeatedly shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #026b.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. Essentially unread (albeit mildly shopworn) hardcover w/dustjacket (in new acetate sleeve). Oxford University (1986) 882 pages. Looks like someone read perhaps the first 20-30 pages of the book, perhaps flipped through the rest of the book looking at pictures, then put the book away never to be taken down and actually "read through". The dustjacket and quarter cloth covers do evidence mild edge and corner shelfwear. From the inside the book is virtually pristine; the pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, seemingly only flipped through a few times, excepting that the first 20 pages or so do evidence mild reading wear. Shelfwear to dustjacket consists of mild edge and corner shelfwear, principally composed of modest crinkling to the dustjacket spine head and heel, modest abrasive rubbing to the top "tips" of the dustjacket (the top open corners of the dustjacket, front and back), and fainter rubbing to the lower corners. There is a very small (1/4 inch) closed, neatly mended edge tear to the dustjacket spine head. We carefully repaired the closed edge tear from the underside of the dustjacket, and touched it up with an oil-based sharpie. Consequently it is not a prominent blemish (in fact it is hard to spot even when you know it is there). We placed the dustjacket inside a new acetate (clear plastic) sleeve so as to enhance its appearance and to protect it against further shelfwear. Beneath the dustjacket the quarter-cloth covers are clean and unsoiled, evidencing only very mild edge and corner shelfwear. Except for the edgewear to the dustjacket, and the fact that the book has clearly been flipped through a few times (particularly the first 20 pages or so), the overall condition of the book is not too far distant from what might pass as "new" from an open-shelf book store (such as Barnes & Noble) wherein patrons are permitted to browse open stock, and so otherwise "new" books are often a bit "shopworn" exhibiting evidence of having breen browsed, as well as modest shelfwear and/or cosmetic blemishes the consequence of routine handling, and simply being repeatedly shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #026b.

PLEASE SEE IMAGES BELOW FOR JACKET DESCRIPTION(S) AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

REVIEW: From the epic poems of Homer to the glittering art and architecture of Greece's Golden Age to the influential Roman systems of law and leadership, the classical world has established the foundations of our culture, as well as many of its enduring achievements. Astonishingly in-depth in its coverage of the entire 1000-year history of the classical world and richly illustrated, The Oxford History of the Classical World offers the general reader the definitive companion to the Graeco-Roman world, its history, and its achievements.

The first volume, Classical Greece and the Hellenistic World, covers the period from the eighth to first centuries B.C., a period unparalleled in history for its brilliance in literature, philosophy, and the visual arts. It also treats the Hellenization of the Middle East by the monarchies established in the area conquered by Alexander the Great. The second volume, Classical Rome, covers early Rome and Italy, the expansion of the Roman republic, the foundation of the Roman Empire by Augustus, its consolidation in the first two centuries A.D., and the later Empire and its influence on Western civilization.

The editors--three eminent classicists, John Boardman, Jasper Griffin, and Oswyn Murray--intersperse chapters on political and social history with chapters on literature, philosophy, and the arts, and reinforce the historical framework with maps and chronological charts. The two volumes also contain bibliographies and a full index, as well as color plates, black and white illustrations, and maps integrated into the text. The contributors--thirty of the world's leading scholars--present the latest in modern scholarship through masterpieces of wit, brevity, and style. While concentrating on the aspects essential to understanding each period, they also focus on those elements of the classical world that remain of lasting importance and interest to readers today. Together, these volumes provide both a provocative and entertaining window into our past.

REVIEW: The subject of this book is enormous. In time it covers a period of well over a thousand years, from the poems of Homer to the end of pagan religion and the fall of the Roman Empire in the West. In geographical extension it begins Greece with small communities emerging from a dark age of conquest and Empire which unified the Mediterranean world and a great deal besides. Thirty-two chapters (with select bibliographies) by different authors, plus an introduction and conclusion. A survey antiquity from the time of Homer to the fall of the Roman Empire. Part 1 covers Greece; Part 2, the Hellenistic Age and the evolution of the Roman Republic; and Part 3, Imperial Rome. The range is wide, embracing history, myth, literary genres, major authors, philosophy, life, society, art, and architecture. Recommended for those desiring a one-volume introduction to the classical world.

REVIEW: The subject of this book is enormous. In time it covers a period of well over a thousand years, from the poems of Homer to the end of pagan religion and the fall of the Roman Empire in the West. In geographical extension it begins Greece with small communities emerging from a dark age of conquest and Empire which unified the Mediterranean world and a great deal besides. Thirty-two chapters (with select bibliographies) by different authors, plus an introduction and conclusion. A survey antiquity from the time of Homer to the fall of the Roman Empire. Part 1 covers Greece; Part 2, the Hellenistic Age and the evolution of the Roman Republic; and Part 3, Imperial Rome. The range is wide, embracing history, myth, literary genres, major authors, philosophy, life, society, art, and architecture. Recommended for those desiring a one-volume introduction to the classical world.

REVIEW: This superbly illustrated book is divided into three main sections. The first, Greece, runs from the eighth to the fourth centuries BC, a period unparalleled in history for its brilliance in literature, philosophy, and the visual arts. The second, Greece and Rome, deals with the Hellenization of the Middle East by the monarchies established in the area conquered by Alexander the Great, the growth of Rome, and the impact of the two cultures on one another. The third, Rome, covers the foundation of the Roman Empire by Augustus and its consolidation in the first two centuries AD. An envoi discusses some aspects of the later Empire and its influence on western civilization, not least through the adoption of Christianity.

REVIEW: This collection of essays from thirty contributors provides a comprehensive overview of the Greco-Roman world, its history, and its social, political, artistic, and cultural achievements.

REVIEW: Provides a historical framework of the Greco-Roman world focusing on the political and social history, literature, philosophy, the arts, etc.

REVIEW: John Boardman is Lincoln Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Oxford. Jasper Griffin and Oswyn Murray are both Fellows Balliol College, Oxford.

REVIEW: John Boardman is Lincoln Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Oxford. Jasper Griffin and Oswyn Murray are both Fellows Balliol College, Oxford.

Table of Contents:

Introduction by Jasper Griffin.

Greece: The history of the Archaic period by George Forrest.

Homer by Oliver Taplin.

Greek Myth and Hesiod by Jasper Griffin.

Lyric and Elegiac Poetry by Ewen Bowie.

Early Greek Philosophy by Martin West.

Greece: The History of the Classical Period by Simon Hornblower.

Greek drama by Peter Levi.

Greek Historians: Life and Society in Classical Greece by Oswyn Murray.

Classical Greek Philosophy by Julia Annas.

Greek Religion by Robert Parker.

Greek Art and Architecture by John Boardman.

The History of the Hellenistic Period by Simon Price.

Hellenistic Culture and Literature by Robin Lane Fox.

Hellenistic Philosophy and Science by Jonathan Barnes.

Early Rome and Italy by Michael Crawford.

Early Rome and Italy by Michael Crawford.

The Expansion of Rome by Elizabeth Rawson.

The First Roman Literature by Peter Brown.

Cicero and Rome by Miriam Griffin.

The Poets of the Late Republic by Robin Nisbet.

Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman Art by Roger Ling.

The Founding of the Empire by David Stockton.

The Arts of Government by Nicholas Purcell.

Augustan Poetry and Society by R.O.A.M. Lyne.

Virgil by Jasper Griffin.

Roman Historians by Andrew Lintott.

The Arts of Prose: The Early Empire by Donald Russell.

Silver Latin Poetry and the Latin Novel by Richard Jenkyns.

Later Philosophy by Anthony Meredith.

The Arts of Living by Roger Ling.

The Arts of Living by Roger Ling.

Roman Life and Society by John Matthews.

Roman Art and Architecture by R.J.A. Wilson.

Envoi: On Taking Leave of Antiquity by Henry Chadwick.

Bbiliography.

Index.

REVIEW: This overview of ancient European history is divided into three roughly equal parts on Greece, Greece and Rome, and Rome, an organizational scheme that underscores the historical progression by which the Greek city-states forged empires that the Romans would later inherit. Within this broad outline, authors Oswyn Murray, John Boardman, and Jasper Griffin, all distinguished Oxford University scholars, outline patterns of trade and colonization, look at the rise of philosophical schools and religions, and examine key works of literature. Oxford History of the Classical World, heavily illustrated with photographs and maps, is a fine reference, complete with compact chronologies [Amazon].

REVIEW: Thirty-two chapters (with select bibliographies) by different authors, plus an introduction and conclusion, survey antiquity from the time of Homer to the fall of the Roman Empire. Part 1 covers Greece, part 2, the Hellenistic age and the evolution of the Roman Republic, and part 3, Imperial Rome. The range is wide, embracing history, myth, literary genres, major authors, philosophy, life, society, art, and architecture. All contributors are not equally successful in their attempt to condense, interpret, and inspire, but generally the results are of high quality, and the book is handsomely produced. Recommended for those desiring a one-volume introduction to the classical world [University of Columbus].

REVIEW: The book is truly excellent. Not only is it beautifully produced, with over 250 illustrations of high quality whose subjects have been most intelligently chosen, but the standard of the contributions is extraordinarily high [The Observer (UK)].

REVIEW: The book is truly excellent. Not only is it beautifully produced, with over 250 illustrations of high quality whose subjects have been most intelligently chosen, but the standard of the contributions is extraordinarily high [The Observer (UK)].

>REVIEW: A fine book considered by many scholars to be the best single volume history of the classical world. The first twelve chapters provide a comprehensive overview of ancient Greece -- its history, literature, philosophy, religion, and art. The next nine chapters describe the Hellenistic Period and the emergence of the Roman Republic. The final eleven chapters concern the rise and fall of the Roman Empire. Each chapter concludes with a detailed list of suggested books for further reading. An essential book for anyone interested in classical history and culture.

REVIEW: This work is an invaluable introduction to and comment on ancient history. As an Oxford student I have first-hand knowledge of many of the contributors and I can tell you that they represent some of the architects of modern classical study. This book is an enormously helpful and balanced work, beneficial to the beginner and the advanced student (both of which I have been while in the this book's company).

REVIEW: This is a very good work on classical Europe. There are many virtues of this complete book, I would like to stress though its most important: its fresh look at ancient world. Although one might not agree with all points in the book, but certainly one agrees that the concept of the book is on the right track. I especially enjoyed the very good chapters in a not well known part of Hellenic history, that of the Hellenistic times, at which the Macedonian Hellenes, made Greece a Universal culture. Buy this book and study it, you can only gain!

REVIEW: This is a very good work on classical Europe. There are many virtues of this complete book, I would like to stress though its most important: its fresh look at ancient world. Although one might not agree with all points in the book, but certainly one agrees that the concept of the book is on the right track. I especially enjoyed the very good chapters in a not well known part of Hellenic history, that of the Hellenistic times, at which the Macedonian Hellenes, made Greece a Universal culture. Buy this book and study it, you can only gain!

REVIEW: The best aspect of this book on Greek history is its comprehensive treatment of all aspects of Greek life. Literature, politics, religion, etc. are all covered in this book. My favorite sections dealt with how the Greeks socialized through organizations such as the Gymnasion and the Prytany. It really showed how the Greeks were devoted to the polis and how they were required to be very social creatures from cradle to grave.

REVIEW: With this synthesis we can say that Oxford exceeds its reputation. The study starts with archaic Greece through until the end of the Roman Empire. Covers many fields (economics, philosophy, arts, politics, military history, and so on). The publication is richly illustrated (maps, photos of works of art, remains, theaters, temples, landscapes, etc.). It is easy to access, pedagogical, never too technical. In short it is a perfect without fail. The book represents the best of knowledge from one of the most prestigious universities in the world. A big, beautiful, collectible book.

REVIEW: Anthologies, while they can be informative, often disappoint owing to the uneven quality of the contributions. The editors John Boardman, Jasper Griffin and Oswyn Murray, however, manage to maintain a consistently very high standard in this "Oxford History of the Classical World". At nearly nine hundred pages, this copious and lavishly illustrated volume covers multifarious aspects of the history of the ancient Graeco-Roman world—social, political, military, literary, artistic, intellectual, religious etc.

Strongest by far are the sections on literature and the arts. What is distinctive is that every major author or literary work receives a miniature portrait, if not a full-length essay one might expect from a literary critic. Oliver Taplin kicks off with an outstanding twenty-eight page treatment of Homer. Taking the Iliad and the Odyssey apart line by line, he shows how they thematically shape time and place. Then, he enters into an extended discussion of the problem of Homeric authorship, citing the classic work on oral tradition by Milman Parry and some more recent reactions to it.

Strongest by far are the sections on literature and the arts. What is distinctive is that every major author or literary work receives a miniature portrait, if not a full-length essay one might expect from a literary critic. Oliver Taplin kicks off with an outstanding twenty-eight page treatment of Homer. Taking the Iliad and the Odyssey apart line by line, he shows how they thematically shape time and place. Then, he enters into an extended discussion of the problem of Homeric authorship, citing the classic work on oral tradition by Milman Parry and some more recent reactions to it.

Ewen Bowie continues with an analysis of lyrical and elegiac poetry, which goes into close detail on Archilochus, Sappho, Alcaeus, Anacreon, Pindar and Simonides. Peter Levi summarizes the evolution of Greek drama and illustrates his statements with a close look at Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes and Meander. Not as detailed, perhaps, but more in the vein of a specialized dictionary are the entries on Hellenistic poetry (Dioscorides, Callimachus, Apollonius). But then Peter Brown supplies a discussion of early Latin literature at a comparable level to what we have just seen with the Greek authors, on Plautus, Terence and Ennius.

The poets of the late Republic, Lucretius and Catullus, have a chapter to themselves followed by one on Augustan poetry and society (Horace, Propertius and Ovid), while Virgil of course gets a full chapter to himself. After the Augustan Age, one proceeds onwards to prose in the early empire (Seneca, Pliny, Plutarch, Lucian and Aristides). Lastly, there is a full-length chapter on the Latin silver age of Quintilian, Lucan, Juvenal, Petronius and Apuleius. In each case, the analysis is satisfying and one feels one has learned something about the poet’s distinctive personality and artistry.

The great Greek and Roman historians (Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius, Sallust, Livy, Tacitus and Suetonius) receive a similar treatment to that of the literary figures in chapters of their own. This Oxford history strives to provide coverage of all the major historical developments in the ancient world as well, with full chapters on the history of the archaic period, the classical period, the Hellenistic period, early Rome and Italy and the expansion of Rome beyond Italy into the Mediterranean world.

Here, the focus is on politics, not nearly as minutely detailed on this score as Bury, but enough so that one can follow the main lines of what happened. Perhaps the best part is on the decline and fall of the Roman republic, where one meets the major players Cicero, Pompey, Cato, Caesar and Crassus. Almost as good is the account of the founding of the empire by Octavian, later Augustus, and the first century through the succession of Tiberius, Caligula and Nero to Vespasian. Compared, say, to Michael Grant’s standard history of Rome, the fuller picture of the personalities and their motivations one gets here enables one to reconstruct the course of events and why they took the form they did. Very much to be appreciated.

Here, the focus is on politics, not nearly as minutely detailed on this score as Bury, but enough so that one can follow the main lines of what happened. Perhaps the best part is on the decline and fall of the Roman republic, where one meets the major players Cicero, Pompey, Cato, Caesar and Crassus. Almost as good is the account of the founding of the empire by Octavian, later Augustus, and the first century through the succession of Tiberius, Caligula and Nero to Vespasian. Compared, say, to Michael Grant’s standard history of Rome, the fuller picture of the personalities and their motivations one gets here enables one to reconstruct the course of events and why they took the form they did. Very much to be appreciated.

One more remark. As expansive as it is, the present volume cannot embrace everything. There is no material at all on the predecessor civilizations of Mesopotamia, Elam, the Hittites, Minoan Crete, Phoenicia, Egypt and Mycenae, and very little on surrounding cultures with which the Graeco-Roman world stood in constant interaction—Celtic, Germanic, Scythian, Parthian, Persian, Arabian. Altogether though, the present volume can be heartily recommended to someone wishing to round out his appreciation of the classical world. What is more, every chapter concludes with a detailed annotated bibliography, so the curious reader will have good leads to follow up on any given topic.

REVIEW: A range of academic essays dealing with many aspects of the histories of the Greeks, the Hellenic era and the Romans. The early essays make clear that while the Greeks were getting around to forming their civilisation, they lived in the ruins of older societies and learned from existing, thriving cultures around the Mediterranean and beyond. The Romans in turn were not so much the heirs of Greek civilization as its conqueror. The Roman destruction of both Corinth and Carthage represented the triumph of brute force, not the onward march of Western enlightenment. Greek culture arrived in Rome as war booty. There are enough interesting essays to make the book pleasing to read.

REVIEW: Phew, what a ride. This book is split up into two parts: Greek civilization, and primary Republican Rome. As far as the entirety of the 'classical world', its primary focus is on these two sovereigns, with some insight into other people from those perspectives.

There is no strict timeline throughout the reading; and it is mostly structured around cultural contrasts, where new ideas are introduced as needed. It is clear this is not a political, or military historical perspective; much if anything is sparse and quickly mentioned. You won't learn much about the Persian wars, or the great battles with Hannibal. Again, this is a cultural review: from society, norms, philosophy and people.

There is no strict timeline throughout the reading; and it is mostly structured around cultural contrasts, where new ideas are introduced as needed. It is clear this is not a political, or military historical perspective; much if anything is sparse and quickly mentioned. You won't learn much about the Persian wars, or the great battles with Hannibal. Again, this is a cultural review: from society, norms, philosophy and people.

This is my first immersion with the Greek world, so I can not appreciate the details as much as a proficient reader would; but the Roman latter half is absolutely riveting. The final years of the Republic of Rome are written through a chapter dedicated to the orator, Cicero. The Greek-Latin linguistic affairs is fascinating, and the chapters on historical, and philosophical figures were my favorite, likewise, in the Hellenistic first-half.

Every chapter ends with a 'further readings' addition. Which is great if you're simply interested in that chapter's topic, or simply a fan of all-things antiquity. Most of the recommended readings are the priceless Loeb Classics.

REVIEW:

REVIEW: I read this one off and on. It's a thorough review of all aspects of Greek and Roman history and culture. Overall an excellent history book.

REVIEW: Overall, a good book for the researcher and enthusiast.

Read for personal research and found this book's contents helpful and inspiring.

REVIEW: Overall, a good book for the researcher and enthusiast.

Read for personal research and found this book's contents helpful and inspiring.

REVIEW: This was a very educational book, especially for someone who is well versed in history.

REVIEW: Very interesting and well researched review of the world of Rome and Greece. Written by a experts in different areas, so it doesn't have a 'thesis', as does Mary Beard's excellent SPQR. But very good background reading.

REVIEW: You can read this like a novel, yet still erudite and scholarly. A wonderful, wonderful book, a must for any classicist. Well written, scholarly yet accessible.

REVIEW: A very ambitious book trying to explore all different facets of ancient western civilization (Greece and Rome - the latter with a focus primarily on the late Republican and Early Empire periods). Excellent!

REVIEW: Comprehensive treatment of Greece Art, Politics, Drama, Daily Life. Myth, Wars etc. written by a host of Oxford University academics. Superb book!

REVIEW: Five stars! The usual high quality Oxford publication – but for serious readers.

REVIEW: The book is totally recommended to anyone who needs a history of the classical world.

REVIEW: The great essays incorporate some of the finest scholarship available. If I were teaching again it would be a constant companion.

REVIEW: Originally read for university class. Excellent resource.

REVIEW: Originally read for university class. Excellent resource.

REVIEW: Simply amazing. Recommended for anyone remotely interested in the classics.

REVIEW: Wonderful book.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

Ancient Hellenic Greece: "The Hellenic World" is a term which refers to that period of ancient Greek history between 507 B.C. (the date of the first democracy in Athens) and 323 B.C. (the death of Alexander the Great). This period is also referred to as the age of Classical Greece and should not be confused with The Hellenistic World which designates the period between the death of Alexander and Rome's conquest of Greece (323 - 146 - 31 B.C.). The Hellenic World of ancient Greece consisted of the Greek mainland, Crete, the islands of the Greek archipelago, and the coast of Asia Minor primarily (though mention is made of cities within the interior of Asia Minor and, of course, the colonies in southern Italy). This is the time of the great Golden Age of Greece and, in the popular imagination, resonates as "ancient Greece".

The great law-giver, Solon, having served wisely as Archon of Athens for 22 years, retired from public life and saw the city, almost immediately, fall under the dictatorship of Peisistratus. Though a dictator, Peisistratus understood the wisdom of Solon, carried on his policies and, after his death, his son Hippias continued in this tradition (though still maintaining a dictatorship which favored the aristocracy). After the assassination of his younger brother (inspired, according to Thucydides, by a love affair gone wrong and not, as later thought, politically motivated), however, Hippias became wary of the people of Athens, instituted a rule of terror, and was finally overthrown by the army under Kleomenes I of Sparta and Cleisthenes of Athens.

Cleisthenes reformed the constitution of Athens and established democracy in the city in 507 B.C. He also followed Solon's lead but instituted new laws which decreased the power of the aristocracy, increased the prestige of the common people, and attempted to join the separate tribes of the mountain, the plain, and the shore into one unified people under a new form of government. According to the historian Durant, "The Athenians themselves were exhilarated by this adventure into sovereignty. From that moment they knew the zest of freedom in action, speech, and thought; and from that moment they began to lead all Greece in literature and art, even in statesmanship and war". This foundation of democracy, of a free state comprised of men who "owned the soil that they tilled and who ruled the state that governed them", stabilized Athens and provided the groundwork for the Golden Age.

Cleisthenes reformed the constitution of Athens and established democracy in the city in 507 B.C. He also followed Solon's lead but instituted new laws which decreased the power of the aristocracy, increased the prestige of the common people, and attempted to join the separate tribes of the mountain, the plain, and the shore into one unified people under a new form of government. According to the historian Durant, "The Athenians themselves were exhilarated by this adventure into sovereignty. From that moment they knew the zest of freedom in action, speech, and thought; and from that moment they began to lead all Greece in literature and art, even in statesmanship and war". This foundation of democracy, of a free state comprised of men who "owned the soil that they tilled and who ruled the state that governed them", stabilized Athens and provided the groundwork for the Golden Age.

The Golden Age of Greece, according to the poet Shelley, "is undoubtedly...the most memorable in the history of the world". The list of thinkers, writers, doctors, artists, scientists, statesmen, and warriors of the Hellenic World comprises those who made some of the most important contributions to western civilization: The statesman Solon, the poets Pindar and Sappho, the playwrights Sophocles, Euripides, Aeschylus and Aristophanes, the orator Lysias, the historians Herodotus and Thucydides, the philosophers Zeno of Elea, Protagoras of Abdera, Empedocles of Acragas, Heraclitus, Xenophanes, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, the writer and general Xenophon, the physician Hippocrates, the sculptor Phidias, the statesman Pericles, the generals Alcibiades and Themistocles, among many other notable names, all lived during this period.

Interestingly, Herodotus considered his own age as lacking in many ways and looked back to a more ancient past for a paradigm of a true greatness. The writer Hesiod, an 8th century B.C. contemporary of Homer, claimed precisely the same thing about the age Herodotus looked back toward and called his own age "wicked, depraved and dissolute" and hoped the future would produce a better breed of man for Greece. Herodotus aside, however, it is generally understood that the Hellenic World was a time of incredible human achievement. Major city-states (and sacred places of pilgrimage) in the Hellenic World were Argos, Athens, Eleusis, Corinth, Delphi, Ithaca, Olympia, Sparta, Thebes, Thrace, and, of course, Mount Olympus, the home of the gods.

The gods played an important part in the lives of the people of the Hellenic World; so much so that one could face the death penalty for questioning - or even allegedly questioning - their existence, as in the case of Protagoras, Socrates, and Alcibiades (the Athenian statesman Critias, sometimes referred to as `the first atheist', only escaped being condemned because he was so powerful at the time). Great works of art and beautiful temples were created for the worship and praise of the various gods and goddesses of the Greeks, such as the Parthenon of Athens, dedicated to the goddess Athena Parthenos (Athena the Virgin) and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (both works which Phidias contributed to and one, the Temple of Zeus, listed as an Ancient Wonder).

The gods played an important part in the lives of the people of the Hellenic World; so much so that one could face the death penalty for questioning - or even allegedly questioning - their existence, as in the case of Protagoras, Socrates, and Alcibiades (the Athenian statesman Critias, sometimes referred to as `the first atheist', only escaped being condemned because he was so powerful at the time). Great works of art and beautiful temples were created for the worship and praise of the various gods and goddesses of the Greeks, such as the Parthenon of Athens, dedicated to the goddess Athena Parthenos (Athena the Virgin) and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (both works which Phidias contributed to and one, the Temple of Zeus, listed as an Ancient Wonder).

The temple of Demeter at Eleusis was the site of the famous Eleusinian Mysteries, considered the most important rite in ancient Greece. In his works The Iliad and The Odyssey, immensely popular and influential in the Hellenic World, Homer depicted the gods and goddesses as being intimately involved in the lives of the people, and the deities were regularly consulted in domestic matters as well as affairs of state. The famous Oracle at Delphi was considered so important at the time that people from all over the known world would come to Greece to ask advice or favors from the god, and it was considered vital to consult with the supernatural forces before embarking on any military campaign.

Among the famous battles of the Hellenic World that the gods were consulted on were the Battle of Marathon (490 B.C.) the Battles of Thermopylae and Salamis (480 B.C.), Plataea (479 B.C.,) and The Battle of Chaeronea (338 B.C.) where the forces of the Macedonian King Philip II commanded, in part, by his son Alexander, defeated the Greek forces and unified the Greek city-states. After Philip's death, Alexander would go on to conquer the world of his day, becoming Alexander the Great. Through his campaigns he would bring Greek culture, language, and civilization to the world and, after his death, would leave the legacy which came to be known as the Hellenistic World. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Greek Colonization: Ancient Greek Colonization. In the first half of the first millennium B.C., Greek city-states, most of which were maritime powers, began to look beyond Greece for land and resources, and so they founded colonies across the Mediterranean. Trade contacts were usually the first steps in the colonization process and then, later, once local populations were subdued or included within the colony, cities were established. These could have varying degrees of contact with the homeland, but most became fully independent city-states, sometimes very Greek in character, in other cases culturally closer to the indigenous peoples they neighbored and included within their citizenry.

One of the most important consequences of this process, in broad terms, was that the movement of goods, people, art, and ideas in this period spread the Greek way of life far and wide to Spain, France, Italy, the Adriatic, the Black Sea, and North Africa. In total then, the Greeks established some 500 colonies which involved up to 60,000 Greek citizen colonists, so that by 500 B.C. these new territories would eventually account for 40% of all Greeks in the Hellenic World. The Greeks were great sea-farers, and traveling across the Mediterranean, they were eager to discover new lands and new opportunities.

Even Greek mythology included such tales of exploration as Jason and his search for the Golden Fleece and that greatest of hero travelers Odysseus. First the islands around Greece were colonized, for example the first colony in the Adriatic was Corcyra (Corfu), founded by Corinth in 733 B.C. (traditional date), and then prospectors looked further afield. The first colonists in a general sense were traders and those small groups of individuals who sought to tap into new resources and start a new life away from the increasingly competitive and over-crowded homeland.

Trade centers and free markets (emporia) were the forerunners of colonies proper. Then, from the mid-8th to mid-6th centuries B.C., the Greek city-states (poleis) and individual groups started to expand beyond Greece with more deliberate and longer-term intentions. However, the process of colonization was likely more gradual and organic than ancient sources would suggest. It is also difficult to determine the exact degree of colonization and integration with local populations. Some areas of the Mediterranean saw fully-Greek poleis established, while in other areas there were only trading posts composed of more temporary residents such as merchants and sailors.

The very term 'colonization' infers the domination of indigenous peoples, a feeling of cultural superiority by the colonizers, and a specific cultural homeland which controls and drives the whole process. This was not necessarily the case in the ancient Greek world and, therefore, in this sense, Greek colonization was a very different process from, for example, the policies of certain European powers in the 19th and 20th centuries A.D. It is perhaps here then, a process better described as 'culture contact'. The establishment of colonies across the Mediterranean permitted the export of luxury goods such as fine Greek pottery, wine, oil, metalwork, and textiles, and the extraction of wealth from the land - timber, metals, and agriculture (notably grain, dried fish, and leather), for example - and they often became lucrative trading hubs and a source of slaves.

A founding city (metropolis) might also set up a colony in order to establish a military presence in a particular region and so protect lucrative sea routes. Also, colonies could provide a vital bridge to inland trade opportunities. Some colonies even managed to rival the greatest founding cities; Syracuse, for example, eventually became the largest polis in the entire Greek world. Finally, it is important to note that the Greeks did not have the field to themselves, and rival civilizations also established colonies, especially the Etruscans and Phoenicians, and sometimes, inevitably, warfare broke out between these great powers.

Greek cities were soon attracted by the fertile land, natural resources, and good harbors of a 'New World' - southern Italy and Sicily. The Greek colonists eventually subdued the local population and stamped their identity on the region to such an extent that they called it 'Greater Greece' or Megalē Hellas, and it would become the most 'Greek' of all the colonized territories, both in terms of culture and the urban landscape with Doric temples being the most striking symbol of Hellenization.

Some of the most important poleis in Italy were Cumae (the first Italian colony, founded circa 740 B.C. by Chalcis), Naxos (734 B.C., Chalcis), Sybaris (circa 720 B.C., Achaean/Troezen), Croton (circa 710 B.C., Achaean), Tarentum (706 B.C., Sparta), Rhegium (circa 720 B.C., Chalcis), Elea (circa 540 B.C., Phocaea), Thurri (circa 443 B.C., Athens), and Heraclea (433 B.C., Tarentum). On Sicily the main colonies included Syracuse (733 B.C., founded by Corinth), Gela (688 B.C., Rhodes and Crete), Selinous (circa 630 B.C.), Himera (circa 630 B.C., Messana), and Akragas (circa 580 B.C., Gela).

The geographical location of these new colonies in the centre of the Mediterranean meant they could prosper as trade centers between the major cultures of the time: the Greek, Etruscan, and Phoenician civilizations. And prosper they did, so much so that writers told of the vast riches and extravagant lifestyles to be seen. Empedokles, for example, described the pampered citizens and fine temples of Akragas (Agrigento) in Sicily as follows; "the Akragantinians revel as if they must die tomorrow, and build as if they would live forever". Colonies even established off-shoot colonies and trading posts themselves and, in this way, spread Greek influence further afield, including higher up the Adriatic coast of Italy. Even North Africa saw colonies established, notably Cyrene by Thera in circa 630 B.C., and so it became clear that Greek colonists would not restrict themselves to Magna Graecia.

Greeks created settlements along the Aegean coast of Ionia (or Asia Minor) from the 8th century B.C. Important colonies included Miletos, Ephesos, Smyrna, and Halicarnassus. Athens traditionally claimed to be the first colonizer in the region which was also of great interest to the Lydians and Persians. The area became a hotbed of cultural Endeavour, especially in science, mathematics, and philosophy, and produced some of the greatest of Greek minds. Art and architectural styles too, assimilated from the east, began to influence the homeland; such features as palmed column capitals, sphinxes, and expressive 'orientalising' pottery designs would inspire Greek architects and artists to explore entirely new artistic avenues.

The main colonizing polis of southern France was Phocaea which established the important colonies of Alalia and Massalia (circa 600 B.C.). The city also established colonies, or at least established an extensive trade network, in southern Spain. Notable poleis established here were Emporion (by Massalia and with a traditional founding date of 575 B.C. but more likely several decades later) and Rhode. Colonies in Spain were less typically Greek in culture than those in other areas of the Mediterranean, competition with the Phoenicians was fierce, and the region seems always to have been considered, at least according to the Greek literary sources, a distant and remote land by mainland Greeks.

The Black Sea (Euxine Sea to the Greeks) was the last area of Greek colonial expansion, and it was where Ionian poleis, in particular, sought to exploit the rich fishing grounds and fertile land around the Hellespont and Pontos. The most important founding city was Miletos which was credited in antiquity with having a perhaps exaggerated 70 colonies. The most important of these were Kyzikos (founded 675 B.C.), Sinope (circa 631 B.C.), Pantikapaion (circa 600 B.C.), and Olbia (circa 550 B.C.). Megara was another important mother city and founded Chalcedon (circa 685 B.C.), Byzantium (668 B.C.), and Herakleia Pontike (560 B.C.). Eventually, almost the entire Black Sea was enclosed by Greek colonies even if, as elsewhere, warfare, compromises, inter-marriages, and diplomacy had to be used with indigenous peoples in order to ensure the colonies' survival.

In the late 6th century B.C. particularly, the colonies provided tribute and arms to the Persian Empire and received protection in return. After Xerxes' failed invasion of Greece in 480 and 479 B.C., the Persians withdrew their interest in the area which allowed the larger poleis like Herakleia Pontike and Sinope to increase their own power through the conquest of local populations and smaller neighboring poleis. The resulting prosperity also allowed Herakleia to found colonies of her own in the 420s B.C. at such sites as Chersonesos in the Crimea.

From the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 431 B.C., Athens took an interest in the region, sending colonists and establishing garrisons. An Athenian physical presence was short-lived, but longer-lasting was an Athenian influence on culture (especially sculpture) and trade (especially of Black Sea grain). With the eventual withdrawal of Athens, the Greek colonies were left to fend for themselves and meet alone the threat from neighboring powers such as the Royal Scythians and, ultimately, Macedon and Philip II.

Most colonies were built on the political model of the Greek polis, but types of government included those seen across Greece itself - oligarchy, tyranny, and even democracy - and they could be quite different from the system in the founder, parent city. A strong Greek cultural identity was also maintained via the adoption of founding myths and such wide-spread and quintessentially Greek features of daily life as language, food, education, religion, sport and the gymnasium, theatre with its distinctive Greek tragedy and comedy plays, art, architecture, philosophy, and science. So much so that a Greek city in Italy or Ionia could, at least on the surface, look and behave very much like any other city in Greece. Trade greatly facilitated the establishment of a common 'Greek' way of life. Such goods as wine, olives, wood, and pottery were exported and imported between poleis.

Even artists and architects themselves relocated and set up workshops away from their home polis, so that temples, sculpture, and ceramics became recognizably Greek across the Mediterranean. Colonies did establish their own regional identities, of course, especially as they very often included indigenous people with their own particular customs, so that each region of colonies had their own idiosyncrasies and variations. In addition, frequent changes in the qualifications to become a citizen and forced resettlement of populations meant colonies were often more culturally diverse and politically unstable than in Greece itself and civil wars thus had a higher frequency. Nevertheless, some colonies did extraordinarily well, and many eventually outdid the founding Greek superpowers.

Colonies often formed alliances with like-minded neighboring poleis. There were, conversely, also conflicts between colonies as they established themselves as powerful and fully independent poleis, in no way controlled by their founding city-state. Syracuse in Sicily was a typical example of a larger polis which constantly sought to expand its territory and create an empire of its own. Colonies which went on to subsequently establish colonies of their own and who minted their own coinage only reinforced their cultural and political independence.

Although colonies could be fiercely independent, they were at the same time expected to be active members of the wider Greek world. This could be manifested in the supply of soldiers, ships, and money for Pan-Hellenic conflicts such as those against Persia and the Peloponnesian War, the sending of athletes to the great sporting games at places like Olympia and Nemea, the setting up of military victory monuments at Delphi, the guarantee of safe passage to foreign travelers through their territory, or the export and import of intellectual and artistic ideas such as the works of Pythagoras or centers of study like Plato's academy which attracted scholars from across the Greek world.

Then, in times of trouble, colonies could also be helped out by their founding polis and allies, even if this might only be a pretext for the imperial ambitions of the larger Greek states. A classic example of this would be Athens' Sicilian Expedition in 415 B.C., officially at least, launched to aid the colony of Segesta. There was also the physical movement of travelers within the Greek world which is attested by evidence such as literature and drama, dedications left by pilgrims at sacred sites like Epidaurus, and participation in important annual religious festivals such as the Dionysia of Athens.

Different colonies had obviously different characteristics, but the collective effect of these habits just mentioned effectively ensured that a vast area of the Mediterranean acquired enough common characteristics to be aptly described as the Greek World. Further, the effect was long-lasting for, even today, one can still see common aspects of culture shared by the citizens of southern France, Italy, and Greece. [Ancient History Encyclopedia].

Ancient Hellenic Jerusalem: Jerusalem Dig Uncovers Ancient Greek Citadel. In the shadow of Jerusalem’s city walls, archaeologists have found a fortress that spawned a bloody rebellion more than two millennia ago. What Jews call the Temple Mount rises above the remains of a Greek citadel exposed by an archaeological dig in Jerusalem. Israeli archaeologists have uncovered the remnants of an impressive fort built more than two thousand years ago by Greeks in the center of old Jerusalem. The ruins are the first solid evidence of an era in which Hellenistic culture held sway in this ancient city.

The citadel, until now known only from texts, was at the heart of a bloody rebellion that eventually led to the expulsion of the Greeks, an event still celebrated by Jews at Hanukkah. But the excavation in the shadow of the Temple Mount, called Haram esh-Sharif by Muslims, is stirring controversy in this politically charged land. “We now have massive evidence that this is part of the fortress called the Acra,” said Doron Ben-Ami, an archaeologist with the Israeli Antiquities Authority who is leading the effort.

Situated under what had long been a parking lot between the Temple Mount to the north and the Palestinian village of Silwan to the south, the site is now a huge rectangular hole that plunges more than three stories below the streets. On a recent visit, workers cleared away dirt as Ben-Ami jumped from rock to rock, enthusiastically pointing out newly excavated features. Massive stones as well as smaller rock provided clues to the identity of the fortress. Roman houses and a Byzantine orchard later covered the site, which more recently was a parking lot.

Alexander the Great conquered Judea in the 4th century B.C., and his successors quarreled over the spoils. Jerusalem, Judea’s capital, sided with Seleucid King Antiochus III to expel an Egyptian garrison, and a grateful Antiochus granted the Jews religious autonomy. For a century and a half, Greek culture and language flourished here. Yet archaeologists have found few artifacts or buildings from this important era that shaped Jewish culture. Conflicts between traditional Jews and those influenced by Hellenism led to tensions, and Jewish rebels took up arms in 167 B.C. The revolt was put down, and Antiochus IV Epiphanes sacked the city, banned traditional Jewish rites, and set up Greek gods in the temple.

According to the Jewish author of 1 Maccabees, a book written shortly after the revolt, the Seleucids built a massive fort in “the city of David with a great and strong wall, and with strong towers.” Called the Acra—from the Greek for a high, fortified place—it was a thorn in the side of Jews who resented Greek dominance. In 164 B.C., Jewish rebels led by Judah Maccabee took Jerusalem and liberated the temple, an event commemorated in the festival of Hanukkah. But the rebels failed to conquer the Acra. For more than two decades, the rebels tried in vain to overwhelm the fortress. Finally in 141 B.C., Simon Maccabee captured the stronghold and expelled the remaining Greeks.

Towering Over the Temple? What happened next has confused and divided scholars for more than a century. According to historian Josephus Flavius, a Jew who served Rome in the first century A.D., Simon Maccabee spent three years tearing down the Acra, ensuring that it no longer towered over the temple. The temple was located to the north of the City of David, on ground more than a hundred feet above the boundaries of early Jerusalem, so Josephus’s story explained this geographical puzzle. But the author of 1 Maccabees insisted that Simon actually strengthened the fortifications and even made it his residence.

This discrepancy spawned many theories in the past century, but no solid archaeological evidence. When an Israeli organization named the Ir David Foundation announced plans to build a museum on top of the parking lot, Ben-Ami began a salvage excavation in 2007. His team dug through successive layers, from an early Islamic market, through a Byzantine orchard and a hoard of 264 coins from the seventh century, under an elaborate Roman villa, and then beyond a first-century place for ritual Jewish bathing. Under buildings that pottery and coins demonstrated to be from the early centuries B.C., the archaeologists found layers of what looked like random rubble.

But the rubble turned out to be carefully placed rocks that formed a glacis, or a defensive slope protruding from a massive wall. “The stones are in layers, at an angle of 15 degrees at the bottom and 30 degrees at the top,” Ben-Ami said, gesturing at color-coded cards pinned into each layer. “This wasn’t a building that collapsed; this was put here on purpose.” Archaeologists exposed a Roman villa close to the Greek fortress. After the citadel’s destruction, the site became a residential area.

The team also found coins that date from the time of Antiochus IV to the time of Antiochus VII, who was the Seleucid king when the Acra fell. “We also have Greek arrowheads, slingshots, and ballistic stones,” he added. “And also amphorae of imported wine.” Since observant Jews drank only local wine, that suggests the presence of foreigners or those influenced by non-Jewish ways. Sling stones and arrowheads found in and around the Greek fortress attest to pitched battles fought by Greek and Jewish defenders against those Jews opposed to Hellenistic control of Jerusalem.

Ben-Ami found no sign that the fortress was dismantled abruptly, or that the entire hill was leveled, as Josephus claimed. Instead, the succeeding Jewish kingdom under Hasmonean rule cut into the glacis during construction in later years. Hasmonean and later Roman builders reused the cut stones for other structures, eating away at the Greek citadel. The find lays to rest theories that placed the Acra north of the temple, immediately adjacent to it, or on the high ground to the west that is now covered by the current walled city.

No one is more delighted by the discovery than Bezalel Bar-Kochva, an emeritus historian at Tel Aviv University. He wrote a 1980 article suggesting that the fort could be found exactly where Ben-Ami dug—a few hundred meters south of the Temple Mount, in the midst of the old City of David. “By the time of Josephus,” he said, “Jerusalem had spread to the west and north, and the city of David was a low spot.” Bar-Kochva believes that the author copied a spurious tale by a Greek historian about Simon’s effort to level the Acra in order to account for this.

Oren Tal, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University not associated with the dig, said that Ben-Ami’s discovery is the “best possible candidate” for the Acra. “The find is fascinating,” added Israeli archaeologist Yonathan Mizrachi. “This suggests that Jerusalem was for a longer time a Hellenistic city in which foreigners were dominant, and who built more than we thought.” Mizrachi, who heads a consortium of scholars called Emek Shaveh, opposes the museum development because it will damage the ruins.

An Israeli planning board last June ordered the Ir David Foundation to scale back the size of the complex. Mizrachi also complains that local residents, who are mostly Palestinian, have not been consulted or involved in the dig that is, almost literally, on their doorsteps. He noted that Ir David supports Jewish settlement of the occupied territories, including the Silwan neighborhood. Meanwhile, Palestinians in Silwan said that the work has led to dangerous cracks in walls and foundations of neighboring houses that threaten their safety.

There is a deeper concern among residents that the dig, however illuminating for scholars, is a step toward dismantling their village. “This excavation is not searching for history,” said Jawad Siam, director of the Madaa Community Center based in Silwan. “It’s designed to serve a settlement project.” Ir David officials did not respond to requests for comment. “When Jerusalem calls, you never say no,” said Ben-Ami. “My expertise is in archaeology, not politics.” [National Geographic (2016)].

The Ptolemaic Dynasty & Hellenic Egypt: The Ptolemaic dynasty controlled Egypt for almost three centuries, from 305 to 30 BC. It eventually fell to the Roman Empire. While they ruled Egypt the Ptolemies they never became “Egyptian”. Instead they isolated themselves in the capital city of Alexandria, a city envisioned by Alexander the Great. The city was Greek both in language and practice. There were no marriages with outsiders or to Native Egyptians. Brother married sister or uncle married niece. The last Ptolemaic monarch was Queen, Cleopatra VII/ She remained Macedonian but spoke Egyptian as well as other languages.

Except for the first two Ptolemaic pharaohs, Ptolemy I and his son Ptolemy II, most of the family was fairly inept. In the end the Ptolemies were only able to maintain their authority with the assistance of Rome. One of the unique and often misunderstood aspects of the Ptolemaic dynasty is how and why the Ptolemies never became Egyptian. The Ptolemies coexisted both as Egyptian pharaohs as well as Greek monarchs. In every respect they remained completely Greek, both in their language and traditions. This unique characteristic was maintained through intermarriage. Most often these marriages were either between brother and sister or uncle and niece.

This inbreeding was intended to stabilize the family. Wealth and power were consolidated. Although it was considered by many an Egyptian and not Greek occurrence, the mother goddess Isis married her brother Osiris. These sibling marriages were justified or at least made more acceptable by referencing tales from Greek mythology in which the gods intermarried. Cronus had married his sister Rhea while Zeus had married Hera. Of the fifteen Ptolemaic marriages, ten were between brother and sister. Two of the fifteen were with a niece or cousin.

Cleopatra VII was the subject of playwrights, poets, and movies. She was last Ptolemaic Monarch to rule Egypt. However Cleopatra VII was not Egyptian, she was Macedonian. According to one ancient historian she was a descendant of such great Greek queens as Olympias, the overly-possessive mother of Alexander the Great. However Cleopatra VII was also the only Ptolemy to learn to speak Egyptian and make any effort to know the Egyptian people. Of course Ptolemaic inbreeding was less than ideal. Jealousy was rampant and conspiracies were common. Ptolemy IV supposedly murdered his uncle, brother, and mother. Ptolemy VIII killed his fourteen-year-old son and chopped him into pieces.

Rewinding to the origins of the dynasty brings us to the sudden death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. His death brought chaos and confusion to his vast empire. Alexander died without naming an heir or successor. Instead history has him saying instead that the empire was left 'to the best'. Those commanders who had faithfully followed him from Macedon across the desert sands of western Asia were left to decide for themselves the fate of the kingdom. Some wanted to wait until the birth of Roxanne and Alexander’s son, the future Alexander IV. Others chose a more immediate and self-serving remedy, which was to simply divide Alexander’s empire amongst themselves.

The final decision would bring decades of war and devastation. The vast territory was split among the most loyal of Alexander’s generals. They included Antigonus I (“the One-Eyed”), Eumenes, Lysimachus, and Antipater. Last was Ptolemy, often referred to as the 'most enterprising' of Alexander’s commanders. Ptolemy I Soter lived from 366 to 282 BC. The suffix appellation “Soter” meant “savior”). Ptolemy was a Macedonian nobleman. According to most sources he was the son of Lagos and Arsinoe. He had been a childhood friend of Alexander. He was Alexander’s official taster and bodyguard. He may even have been related to Alexander. Rumors abounded that he was the illegitimate son of Philip II, Alexander’s father.

After the death of Alexander Ptolemy had led the campaign to divide the empire among the leading generals and in the partition of Babylon. To his delight Ptolemy received the land he had always craved, Egypt. In Ptolemy’s eyes Egypt was the ideal land, rich in resources. After years of oppression under the Persians the people of Egypt had welcomed Alexander and his conquering army. The Persian conquerors had been intolerant of the Egyptian customs and religion. Alexander was far more tolerant. Alexander publicly embraced their gods and prayed at their temples. He had even built a temple to honor the Egyptian mother goddess Isis.

In Egypt Ptolemy saw vast potential, for himself. There was wealth beyond measure. That wealth was largely derived from agricultural production. Egypt’s borders were easy to defend. Libya lay to the west, Arabia to the east. He was not forced to be dependent upon the good will of the collegial commanders who had also served Alexander. Furthermore Egypt was on friendly terms with his homeland of Macedon. While the partition may have granted Egypt to Ptolemy, there were some who did not trust the cagey commander. Chief amongst those was Perdiccas, the self-appointed successor to Alexander.

Cleomenes of Naucratis was had been named the Egyptian finance minister by Alexander. He was appointed by Perdiccas as an adjunct or hyparchos to keep watch (spy) on Ptolemy. Realizing Perdiccas' ploy, Ptolemy knew he had to free himself of Cleomenes. He accused the unwary minister of 'fiscal malfeasance' - not a completely trumped-up charge - and had him executed. With Cleomenes gone Ptolemy could then rule Egypt without anyone watching over his shoulder. In so doing Ptolemy would establish a dynasty that would last for almost three centuries until the time of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra VII.

During Ptolemy’s four-decade rule of Egypt he would put the country on sound economic and administrative footing. After the death of Cleomenes Ptolemy began quickly and firmly to consolidate his power within Egypt. His sole purpose was to make Egypt great again. Reluctantly however he became involved in the ongoing Wars of the Successors. These were the destructive wars between Ptolemy’s colleagues, Alexander’s former generals who had each received portions of Alexander’s empire.

While Ptolemy I did not deliberately seek territory outside Egypt, he would take advantage of a fortuitous occurrence if given the chance. Ptolemy occupied the island of Cyprus around 318 BC. Another opportunity found him fighting a Spartan named Thribon who had seized the city of Cyrene on the North Africa coast. After a quick, decisive victory Ptolemy turned the fallen conqueror over to the city who promptly executed him.

Unfortunately Ptolemy could not avoid some involvement with the other commanders. He gave refuge to Seleucus and later supported Rhodes against the invading forces of Demetrius the Besieger, son of Antigonus. And there was his ongoing rivalry with Perdiccas. The hostility did not subside when Ptolemy stole Alexander’s body as it was being transported to a newly built tomb in Macedon. As the king’s chiliarch (or adjutant, commander) Perdiccas had established himself securely after Alexander’s death. Perdiccas had always hoped to reunite under his control what had been Alexander’s Empire before it had been parceled out.

Perdiccas possessed Alexander’s signet ring as well as the Alexander’s remains. The intention was to return Alexander’s remains to Macedon for internment. However at Damascus the body inexplicably disappeared. Ptolemy had stolen and taken the body to Memphis. From Memphis Alexander’s body was taken to Alexandria. It was interred in a golden sarcophagus which was displayed in the center of the city. Perdiccas to say the least was outraged. However to those in Egypt the legitimacy of the Ptolemaic Dynasty lay in its connection to the fallen king. Even in death Alexander played a major role in both the Egyptian and Ptolemaic imagination. And Alexandria was the city conceived by Alexander.

However the theft of Alexander’s body was too much for Perdiccas. The long simmering animosity boiled over into a war between Perdiccas and Ptolemy which lasted from 322 to 321 BC. Perdiccas attempted three military assaults on the Ptolemaic pharaoh. However all three attempts to cross the Nile into Egypt failed. After the loss of over two thousand soldiers his army had had enough and executed Perdiccas. There were few if any tears shed among the other collegial former commanders of Alexander. Perdiccas had not been very popular with any of them.

Ptolemy I died in 282 BC. He named his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus as his successor. “Philadelphus” translates to “sister-loving”. The younger Ptolemy had served as co-regent with his father since 285 BC, when he was 23. Ptolemy II would rule until 246 BC. He married Arsinoe I, the daughter of the Thracian regent/king Lysimachus. Lysimachus you’ll recall was one of Ptolemy I’s colleagues, another former general for Alexander. Lysimachus had married Arsinoe II, the daughter of Ptolemy I and his mistress Berenice around 300 BC. The marriage was for the purpose of maintaining the alliance between Ptolemy and Lysimachus.

The marriage took place after the death of Lysimachus’s first wife. It was a marriage he would regret. Probably to secure the throne of Thrace for her own son Arsinoe II convinced her husband to kill his presumptive heir and oldest son by his first marriage. The trumped-charges used for justification were treason. But though we can presume Arsinoe’s motives, we cannot be certain. It is certain that the murder of the popular young commander caused uproar among many of his fellow officers.

After the death of Lysimachus, Ptolemy I would marry Lysimachus’s widow Arsinoe II, who was also his sister. Unlike many of his successors Ptolemy II expanded Egypt with acquisitions in Asia Minor and Syria. Egypt also reclaimed the Greek/Hellenic colonial city Cyrene in Libya. Originally Cyrene was a Libyan colony of the island of Thera. Cyrene had declared independence from Ptolemaic Egypt. Ptolemy II also fought two wars known as the “Syrian Wars”. They were fought against Antiochus I and Antiochus II. Antiochus I was another of Alexander’s generals and thus collegial to Ptolemy I. Ultimately Ptolemy II would marry his daughter Berenice to Antiochus II.

Unfortunately Ptolemy II also fought the Chremonidean War against Macedon from 267-261 BC. Ptolemy’s forces failed in that endeavor. In Egypt Ptolemy II established trading posts along the Red Sea. He also completed construction on the Pharos, and enlarged the library and museum at Alexandria. To honor his parents Ptolemy II established a new festival, the Ptolemaeia. According to history Ptolemy II was one the last truly great pharaohs of Egypt. Many of those Ptolemies who followed failed to strengthen Egypt both internally and externally. Jealousy and in-fighting were common.

Upon the death of Ptolemy II in 246 BC, Ptolemy III Euergetes came to the throne. “Euergetes” translates to “benefactor”. Ptolemy III ruled until 221 BC. He married Berenice II who was from the Greek city of Cyrene. Among their six children were Ptolemy IV and a princess also named Berenice. The sudden death of Princess Berenice brought about the Canopus Decree in 238 BC. Among other proclamations she was honored as a goddess. Another proclamation was the decree of for a new calendar, one that included 365 days with one additional day every four years. However the new calendar was not adopted.

In 246 BC Ptolemy III invaded Syria to support Antiochus II in the Third Syrian War against Seleucus II. Antiochus II was Ptolemy’s brother-in-law, i.e., his sister’s husband. However Ptolemy III gained little from the war other than the acquisitions of a few towns in Syria and Asia Minor. His successor and son was Ptolemy IV Philopator. “Philopater” translates to “father-loving”. Ptolemy IV ruled from 221 until 205 BC. Keeping with family tradition, he married his sister Arsinoe III in 217 BC. He gained a small degree of success in the Fourth Syrian War which was conducted from 219 to 217 BC against Antiochus III. However Ptolemy IV was otherwise largely ineffective. His only other accomplishment was the building of the Sema. The Sema was a tomb to honor both Alexander and the Ptolemies. Ptolemy IV and his wife were both murdered in a palace coup in 205 BC.

Ptolemy V Epiphanes was the son of Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III. “Epiphanes” translates to “made manifest”. Ptolemy V ruled from 205 to 180 BC. Due to the sudden death of his parents inherited the throne as a small boy 5 years of age. At age 17 he married the Seleucid princess Cleopatra I in 193 BC. Unfortunately war and revolt by Seleucid and Macedonian kings with hopes to seize Egyptian lands followed his ascension. Following the Battle of Panium in 200 BC Egypt lost valuable territory in the Aegean and Asia Minor, including Palestine. In 206 BC dissidence arose in the Egyptian city of Thebes, and it would remain outside Ptolemaic control for twenty years.

Ptolemy V’s successor was Ptolemy VI Philometor. “Philometor” translates to “mother-loving. As did his father he began his reign as a small child. He ruled alongside his mother until her unexpected death in 176 BC. Ptolemy VI married his sister Cleopatra II and began his tumultuous reign. He had a seriously troubled relationship with his brother, the future Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II. Egypt was invaded twice between 169 and 164 BC by Antiochus IV, whose army even approached the city of Alexandria. With the assistance of Rome Ptolemy VI regained nominal control of Egypt. However ruling alongside his brother and his wife his reign remained characterized by unrest.

In 163 BC his brother and he (Ptolemy VI and the future Ptolemy VIII) finally reached a compromise whereby Ptolemy VI ruled Egypt while his brother ruled Cyrene. In 145 BC Ptolemy VI died in battle in Syria. Intervening the reign of Ptolemy VI and his brother Ptolemy VIII one presumes would be a Ptolemy VII. However little is known of the reign or person known as Ptolemy VII. Indeed it is not even certain that a Ptolemy VII ever really reigned. However it is certain that upon the death of Ptolemy VI, Ptolemy VIII stepped onto the throne in 145 BC.

Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II was the younger brother of Ptolemy VI. “Euergetes” translates to “benefactor”. In true Ptolemaic fashion he married his elder brother’s widow, Cleopatra II. However in short order he replaced Cleopatra II with her daughter (his niece) Cleopatra III. A civil war ravaged Egypt lasting from 132 to 124 BC. The capital city of Alexandria which happened to hate Ptolemy VIII was particularly devastated. It was not uncommon for the residents of Alexandria to dislike the reigning Ptolemy. There was little love lost between the city’s citizens and the royal family. This intense loathing brought about extreme persecution and expulsion for the inhabitants of the city. Finally, an amnesty was reached in 118 BC.

Ptolemy VIII was succeeded by his eldest son in 116 BC. Ptolemy IX Soter II ruled from 116 to 80 BC. “Soter” translates to “Savior”, but Ptolemy IX was also known as “Lathyrus”, which translates to “Chickpea”. Like many of his predecessors he would marry two of his sisters. The first was Cleopatra IV, mother of Berenice IV. The second was Cleopatra V Serene who gave him two sons. He ruled jointly with his mother Cleopatra III until 107 BC. In 107 BC he was forced to flee to Cyprus after being overthrown by his brother, Ptolemy X. He regained the throne in 88 BC when in Egypt his brother Ptolemy X was expelled from Egypt and lost at sea. Restored to Egypt’s throne, Ptolemy IX would rule until his death in 80 BC.

The next few Ptolemies made little impact if any on Egypt. For the first time Rome played a major role in the affairs of Egypt. Rome was a rising power in the west. Ptolemy X Alexander I was the younger brother of Ptolemy IX. He had served as governor of Cyprus until his mother brought him to Egypt in 107 BC. Once in Egypt his mother engineered replacing Ptolemy IX on Egypt’s throne with Ptolemy X. In 101 BC he supposedly murdered his mother Cleopatra IV. He then married Berenice III, daughter of his niece Cleopatra V Serene. He ruled Egypt until 88 BC. In 88 BC Ptolemy X left Egypt after being expelled and was lost at sea.

Ptolemy X was succeeded briefly by his youngest son, twelve-year-old Ptolemy XI Alexander II. Ptolemy XI ruled for eight years. He was placed on the throne by the Roman general Cornelius Sulla after the young Ptolemy XI agreed to award Egypt and Cyprus to Rome. Ptolemy XI ruled jointly with his step-mother Cleopatra Berenice until he murdered her. Unfortunately he was then himself murdered by the Alexandrians in 80 BC. Replacing Ptolemy XI was Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos (also known as “Auletes”). Ptolemy XII was another son of Ptolemy IX. He married his sister Cleopatra Tryphaena. Unfortunately his close relationship with Rome caused him to be despised by the Alexandrians, and he was expelled from Egypt in 58 BC.<> Ptolemy XII regained Egypt’s throne with the assistance of the Roman Syrian governor Gabinius. From that point onward he was only able to remain in power through his ties to Rome. Even then those ties required constant renewal through bribery as the Roman Senate actually distrusted him. The next pharaoh Ptolemaic Pharaoh was Ptolemy XIII, who ruled only through 47 BC whereupon he was executed at age 16. Ptolemy XIII was the brother and husband of the infamous Cleopatra VII. His time on the throne was short-lived consequence of his unsuccessful alliance with his sister Arsinoe in a civil war. They chose to oppose both Julius Caesar and Cleopatra in a fight for the throne.

Initially Ptolemy XIII he had expected to gain favor with Caesar when he killed the Roman general Pompey, who had sought refuge in Egypt. Ptolemy XIII presented Pompey’s severed head to Caesar. However, the Roman commander grew irate because he had wanted to execute Pompey himself. In the civil war which ensued Ptolemy XIII’s army was defeated after an intense battle. Ptolemy XIII himself drowned in the Nile River when his boat overturned. His sister Princess Arsinoe was taken to Rome in chains. She was later to released.

Following Ptolemy XIII was another brother Ptolemy XIV. Ptolemy XIV served briefly as governor of Cyprus. He later married his sister on the wishes of Caesar. He ruled for three years until his abrupt death in 44BC at age 15. His death is attributed by many historians to being poisoned upon the orders of his infamous sister Cleopatra VII. The last pharaoh of Egypt was Cleopatra VII, who is known to history as simply Cleopatra. She ruled Egypt for 22 years and controlled much of the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Like many of the women of her era she was highly educated. Cleopatra VII had been groomed for the throne by her father Ptolemy XII in the traditional Greek (Hellenistic) manner. She endeared herself to the Egyptian people. She accomplished this by participating in many Egyptian festivals and ceremonies. She was also the only Ptolemy to learn the Egyptian language. Cleopatra also spoke Hebrew, Ethiopian, and several other languages.

To secure the throne after defeating her brothers and sister in the civil war, she realized she had to remain friendly with Rome. Her relationship with Julius Caesar has been the subject of dramatists and poets for centuries. With the death of Caesar and the balance of power in Rome in question she had the misfortune of siding with the Roman general Mark Antony. Antony and Cleopatra lost it all at the Battle of Actium. She failed to find compassion in Octavian, the future Emperor Augustus. She was left with no other exit other than suicide. Cleopatra VII had a son with Caesar, Caesarion (Ptolemy XV), Caesarion was put to death by Octavian as otherwise Octavian’s status as their heir to Julius Caesar could be challenged.

Cleopatra VII’s other children, Alexander Helos, Cleopatra Serene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus were younger and were brought to Rome to be raised by Octavian's wife. As with the rest of the Mediterranean, frequently described as a Roman lake, Egypt submitted to Roman rule. The power of the Ptolemies ended. One of the most significant features of Ptolemaic rule had been its policy of Hellenization. Hellenization included the integration of Greek language and culture into Egyptian daily life. There was no attempt on behalf of the Ptolemies or the Hellenic population of Alexandria to become assimilated into Egyptian civilization.