Emanuel Swedenborg (/ˈswiːdənbɔːrɡ/,[2] Swedish: [ˈsvêːdɛnˌbɔrj] ⓘ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 8 February [O.S. 29 January] 1688 – 29 March 1772)[3] was a Swedish Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic.[4] He became best known for his book on the afterlife, Heaven and Hell (1758).[5][6]

Swedenborg had a prolific career as an inventor and scientist. In 1741, at 53, he entered into a spiritual phase in which he began to experience dreams and visions, notably on Easter Weekend, on 6 April[7] 1744.[8] His experiences culminated in a "spiritual awakening" in which he received a revelation that Jesus Christ had appointed him to write The Heavenly Doctrine to reform Christianity.[9] According to The Heavenly Doctrine, the Lord had opened Swedenborg's spiritual eyes so that from then on, he could freely visit heaven and hell to converse with angels, demons and other spirits, and that the Last Judgment had already occurred in 1757, the year before the 1758 publication of De Nova Hierosolyma et ejus doctrina coelesti (English: Concerning the New Jerusalem and its Heavenly Doctrine).[10]

Over the last 28 years of his life, Swedenborg wrote 18 published theological works—and several more that remained unpublished. He termed himself a "Servant of the Lord Jesus Christ" in True Christian Religion,[11] which he published himself.[12] Some followers of The Heavenly Doctrine believe that of his theological works, only those that were published by Swedenborg himself are fully divinely inspired.[13] Others have regarded all Swedenborg's theological works as equally inspired, saying for example that the fact that some works were "not written out in a final edited form for publication does not make a single statement less trustworthy than the statements in any of the other works".[14] The New Church, also known as Swedenborgianism, is a Restorationist denomination of Christianity originally founded in 1787 and comprising several historically related Christian churches that revere Swedenborg's writings as revelation.[1][15]

Early life

Swedenborg's father, Jesper Swedberg (1653–1735), descended from a wealthy mining family, bergsfrälse (early noble families in the mining sector), the Stjärna family, of the same patrilineal background as the noble family Stiernhielm, the earliest known patrilineal member being Olof Nilsson Stjärna of Stora Kopparberg.[16][17] He travelled abroad and studied theology, and on returning home, he was eloquent enough to impress the Swedish king, Charles XI, with his sermons in Stockholm. Through the king's influence, he would later become professor of theology at Uppsala University and Bishop of Skara.[18][3]

Jesper took an interest in the beliefs of the dissenting Lutheran Pietist movement, which emphasised the virtues of communion with God rather than relying on sheer faith (sola fide).[19] Sola fide is a tenet of the Lutheran Church, and Jesper was charged with being a pietist heretic. While controversial, the beliefs were to have a major impact on his son Emanuel's spirituality. Jesper furthermore held the unconventional belief that angels and spirits were present in everyday life. This also came to have a strong impact on Emanuel.[18][3][20]

In 1703–1709, aged 15–21, Emanuel Swedenborg lived in Erik Benzelius the Younger's house. He completed his university course at Uppsala in 1709, and in 1710, he made his grand tour through the Netherlands, France and Germany before reaching London, where he would spend the next four years. It was a flourishing centre of scientific ideas and discoveries. He studied physics, mechanics and philosophy and read and wrote poetry. According to the preface of a book by the Swedish critic Olof Lagercrantz, Swedenborg wrote to his benefactor and brother-in-law Benzelius that he believed he might be destined to be a great scientist.[21][22]

Early scientific work and spiritual reflections

In 1715, aged 27, Swedenborg returned to Sweden, where he devoted himself to natural science and engineering projects for the next two decades. A first step was his meeting with King Charles XII of Sweden in the city of Lund, in 1716. The Swedish inventor Christopher Polhem, who became a close friend of Swedenborg, was also present. Swedenborg's purpose was to persuade the king to fund an observatory in northern Sweden. However, the warlike king did not consider this project important enough, but did appoint Swedenborg to be assessor-extraordinary on the Swedish Board of Mines (Bergskollegium) in Stockholm.[25]

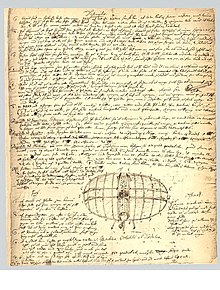

From 1716 to 1718, aged 30, Swedenborg published a scientific periodical entitled Daedalus Hyperboreus ("The Northern Daedalus"), a record of mechanical and mathematical inventions and discoveries. One notable description was that of a flying machine, the same he had been sketching a few years earlier.[22]

In 1718, Swedenborg published an article that attempted to explain spiritual and mental events in terms of minute vibrations, or "tremulations".

Upon the death of Charles XII, Queen Ulrika Eleonora ennobled Swedenborg and his siblings. It was common in Sweden during the 17th and 18th centuries for the children of bishops to receive that honor, as a recognition of the services of their father. The family name was changed from Swedberg to Swedenborg.[26]

In 1724, he was offered the chair of mathematics at Uppsala University, but he declined and said that he had dealt mainly with geometry, chemistry and metallurgy during his career. He also said that he did not have the gift of eloquent speech because of a stutter, as recognized by many of his acquaintances; it forced him to speak slowly and carefully, and there are no known occurrences of his speaking in public.[27] The Swedish critic Olof Lagerkrantz proposed that Swedenborg compensated for his impediment by extensive argumentation in writing.[28]

Scientific studies and spiritual reflections in the 1730s

During the 1730s, Swedenborg undertook many studies of anatomy and physiology. He had the first known anticipation of the neuron concept.[29] a century before the full significance of the nerve cell was realised. He also had prescient ideas about the cerebral cortex, the hierarchical organization of the nervous system, the localization of the cerebrospinal fluid, the functions of the pituitary gland, the perivascular spaces, the foramen of Magendie, the idea of somatotopic organization, and the association of frontal brain regions with the intellect. In some cases, his conclusions have been experimentally verified in modern times.[30][31][32][33][34]

In the 1730s, Swedenborg became increasingly interested in spiritual matters and was determined to find a theory to explain how matter relates to spirit. Swedenborg's desire to understand the order and the purpose of creation first led him to investigate the structure of matter and the process of creation itself. In the Principia, he outlined his philosophical method, which incorporated experience, geometry (the means by which the inner order of the world can be known) and the power of reason. He also outlined his cosmology, which included the first presentation of his nebular hypothesis. (There is evidence that Swedenborg may have preceded Kant by as much as 20 years in the development of that hypothesis.[35]) Other inventions by Swedenborg include a submarine, an automatic weapon, an universal musical instrument, a system of sluices that could be used to transport boats across land and several types of water pumps, which were put into use when he was on Sweden's Board of Mines.[36]

In 1735, in Leipzig, he published a three-volume work, Opera philosophica et mineralis ("Philosophical and Mineralogical Works") in which he tried to conjoin philosophy and metallurgy. The work was mainly appreciated for its chapters on the analysis of the smelting of iron and copper, and it was the work that gave Swedenborg his international reputation.[37] The same year, he also published the small manuscript De Infinito ("On the Infinite") in which he attempted to explain how the finite is related to the infinite and how the soul is connected to the body. It was the first manuscript in which he touched upon such matters. He knew that it might clash with established theologies since he presented the view that the soul is based on material substances.[38][39] He also conducted dedicated studies of the fashionable philosophers of the time such as John Locke, Christian von Wolff, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Descartes and earlier thinkers such as Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus and Augustine of Hippo.[40]

Swedenborg was a critic of slavery. He was the first prominent Swede to condemn slavery. In his works, he argued that sub-Saharan Africans were superior to Europeans, and condemned European missionaries for intruding on African lands.[41]

In 1743, at the age of 55, Swedenborg requested a leave of absence to go abroad. His purpose was to gather source material for Regnum animale (The Animal Kingdom, or Kingdom of Life), a subject on which books were not readily available in Sweden. The aim of the book was to explain the soul from an anatomical point of view. He had planned to produce a total of 17 volumes.[42]

Journal of Dreams

By 1744, when he was 56, Swedenborg had traveled to the Netherlands. Around the time, he began having strange dreams. Swedenborg carried a travel journal with him on most of his travels and did so on this journey. The whereabouts of the diary were long unknown, but it was discovered in the Royal Library in the 1850s and was published in 1859 as Drömboken, or Journal of Dreams.

Swedenborg experienced many different dreams and visions, some greatly pleasurable, others highly disturbing.[43] The experiences continued as he traveled to London to progress the publication of Regnum animale. This process, which one biographer has proposed as cathartic and comparable to the Catholic concept of Purgatory,[44] continued for six months. He also proposed that what Swedenborg was recording in his Journal of Dreams was a battle between the love of himself and the love of God.[45]

Visions and spiritual insights

In the last entry of the journal from 26–27 October 1744, Swedenborg appears to be clear as to which path to follow. He felt that he should drop his current project and write a new book about the worship of God. He soon began working on De cultu et amore Dei, or The Worship and Love of God. It was never fully completed, but Swedenborg still had it published in London in June 1745.[46]

In 1745, aged 57, Swedenborg was dining in a private room at a tavern in London. By the end of the meal, a darkness fell upon his eyes, and the room shifted character. Suddenly, he saw a person sitting at a corner of the room, telling him: "Do not eat too much!". Swedenborg, scared, hurried home. Later that night, the same man appeared in his dreams. The man told Swedenborg that he was the Lord, that he had appointed Swedenborg to reveal the spiritual meaning of the Bible and that he would guide Swedenborg in what to write. The same night, the spiritual world was opened to Swedenborg.[47][48]

Scriptural commentary and writings

In June 1747, Swedenborg resigned his post as assessor of the board of mines. He explained that he was obliged to complete a work that he had begun and requested to receive half his salary as a pension.[49] He took up afresh his study of Hebrew and began to work on the spiritual interpretation of the Bible with the goal of interpreting the spiritual meaning of every verse. From sometime between 1746 and 1747 and for ten years, he devoted his energy to the task. Usually abbreviated as Arcana Cœlestia or under the Latin variant Arcana Caelestia[50] (translated as Heavenly Arcana, Heavenly Mysteries, or Secrets of Heaven depending on modern English-language editions), the book became his magnum opus and the basis of his further theological works.[51]

The work was anonymous, and Swedenborg was not identified as the author until the late 1750s. It had eight volumes, published between 1749 and 1756. It attracted little attention, as few people could penetrate its meaning.[52][53]

His writings were filled with symbolism - Swedenborg often used stones to represent truth, snakes for evil, houses for intelligence, and cities for religious systems. He also described the appearance of heaven in great detail, as well as inhabitants from other planets.[54]

His life from 1747 to his death was spent in Stockholm, the Netherlands, and London. During the 25 years, he wrote another 14 works of a spiritual nature; most were published during his lifetime.

One of Swedenborg's lesser-known works presents a startling claim: that the Last Judgment had begun in the previous year (1757) and was completed by the end of that year[55] and that he had witnessed it.[56] According to The Heavenly Doctrine, the Last Judgment took place not in the physical world but in the World of Spirits, halfway between heaven and hell, through which all pass on their way to heaven or hell.[57] The Judgment took place because the Christian church had lost its charity and faith, resulting in a loss of spiritual free will that threatened the equilibrium between heaven and hell in everyone's life.[58][a]

The Heavenly Doctrine also teaches that the Last Judgement was followed by the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, which occurred not by Christ in person but by a revelation from him through the inner, spiritual sense of the Word[59] through Swedenborg.[60]

In another of his theological works, Swedenborg wrote that eating meat, regarded in itself, "is something profane" and was not practised in the early days of the human race. However, he said, it now is a matter of conscience, and no one is condemned for doing it.[61] Nonetheless, the early-days ideal appears to have given rise to the idea that Swedenborg was a vegetarian. That conclusion may have been reinforced by the fact that a number of Swedenborg's early followers were part of the vegetarian movement that arose in Britain in the 19th century.[62] However, the only reports on Swedenborg himself are contradictory. His landlord in London, Shearsmith, said he ate no meat, but his maid, who served Swedenborg, said that he ate eels and pigeon pie.[63]

In Earths in the Universe, it is stated that he conversed with spirits from Jupiter, Mars, Mercury, Saturn, Venus and the Moon, as well as spirits from planets beyond the Solar System.[64] From the "encounters", he concluded that the planets of the Solar System are inhabited and that such an enormous undertaking as the universe could not have been created for just one race on a planet or one "Heaven" derived from its properties per planet. Many Heavenly societies were also needed to increase the perfection of the angelic Heavens and Heaven to fill in deficiencies and gaps in other societies. He argued: "What would this be to God, Who is infinite, and to whom a thousand or tens of thousands of planets, and all of them full of inhabitants, would be scarcely anything!"[65] Swedenborg and the question of life on other planets has been extensively reviewed elsewhere.[66]

Swedenborg published his work in London or the Netherlands to escape censorship by the Swedish Empire.[67][68]

In July 1770, at the age of 82, he traveled to Amsterdam to complete the publication of his last work. The book, Vera Christiana Religio (The True Christian Religion), was published there in 1771 and was one of the most appreciated of his works. Designed to explain his teachings to Lutherans, it is the most concrete of his works.[69]

Later life

In the summer of 1771, he traveled to London. Shortly before Christmas, he had a stroke and was partially paralyzed and confined to bed. His health improved somewhat, but he died in 1772. There are several accounts of his last months, made by those with whom he stayed and by Arvid Ferelius, a pastor of the Swedish Church in London, who visited him several times.[70]

There is evidence that Swedenborg wrote a letter to John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, in February. Swedenborg said that he had been told in the world of spirits that Wesley wanted to speak with him.[71] Wesley, startled since he had not told anyone of his interest in Swedenborg, replied that he was going on a journey for six months and would contact Swedenborg on his return. Swedenborg replied that would be too late since Swedenborg would be going to the spiritual world for the last time on March 29.[72] (Wesley later read and commented extensively on Swedenborg's work.)[73] Swedenborg's landlord's servant girl, Elizabeth Reynolds, also said that Swedenborg had predicted the date and that he was as happy about it as if he was "going on holiday or to some merrymaking":[74]

In Swedenborg's final hours, his friend, Pastor Ferelius, told him some people thought he had written his theology just to make a name for himself and asked Swedenborg if he would like to recant. Raising himself up on his bed, his hand on his heart, Swedenborg earnestly replied,

"As truly as you see me before your eyes, so true is everything that I have written; and I could have said more had it been permitted. When you enter eternity you will see everything, and then you and I shall have much to talk about."[75]

He then died, in the afternoon, on the date he had predicted, March 29.[75]

He was buried in the Swedish Church in Princes Square in Shadwell, London. On the 140th anniversary of his death, in 1912/1913, his remains were transferred to Uppsala Cathedral in Sweden, where they now rest close to the grave of the botanist Carl Linnaeus. In 1917, the Swedish Church in Shadwell was demolished, and the Swedish community that had grown around the parish moved to Marylebone. In 1938, Princes Square was redeveloped, and in his honour the local road was renamed Swedenborg Gardens. In 1997, a garden, play area and memorial, near the road, were created in his memory.[76][77][78]

Veracity

Swedenborg's transition from scientist to revelator or mystic has fascinated many people. He has had a variety of both supporting and critical biographers.[79] Some propose that he did not have a revelation at all but developed his theological ideas from sources which ranged from his father to earlier figures in the history of thought, notably Plotinus. That position was first taken by Swedish writer Martin Lamm who wrote a biography of Swedenborg in 1915.[80][b] Swedish critic and publicist Olof Lagercrantz had a similar point of view, calling Swedenborg's theological writing "a poem about a foreign country with peculiar laws and customs".[81]

Swedenborg's approach to proving the veracity of his theological teachings was to use voluminous quotations from the Old Testament and the New Testament to demonstrate agreement with the Bible, and this is found throughout his theological writings. A Swedish Royal Council considering heresy charges against two Swedish promoters of his theological writings concluded that "there is much that is true and useful in Swedenborg's writings".[82] Victor Hugo suggested in passing, in Chapter 14 of Les Misérables, that Swedenborg, in company with Blaise Pascal, had "glided into insanity".[83]

Scientific beliefs

Swedenborg proposed many scientific ideas during his lifetime. In his youth, he wanted to present a new idea every day, as he wrote to his brother-in-law Erik Benzelius in 1718. Around 1730, he had changed his mind, and instead believed that higher knowledge is not something that can be acquired, but that it is based on intuition. After 1745, he instead considered himself receiving scientific knowledge in a spontaneous manner from angels.[84]

From 1745, when he considered himself to have entered a spiritual state, he tended to phrase his "experiences" in empirical terms, to report accurately things he had experienced on his sp