History of the New York City Police Department

The New York City Police Department (NYPD) originates in the Government of New York City attempts to control rising crime in early to mid 19th century New York City. This increased crime was due to an increased population, caused primarily by poor Irish immigrants beginning in the 1820s. The City's reforms was modeled upon London's Metropolitan Police Service of a full-time professional police force in 1845. The Municipal Police replaced the inadequate night watch system which had been in place since the 17th century, when the city was founded by the Dutch as New Amsterdam.

In 1857, the Municipal Police were tumultuously replaced by the Metropolitan Police, which consolidated other local police departments.

Late 19th and early 20th century trends included professionalization and struggles against corruption.

19th century[edit]

Prior to the establishment of the NYPD, New York City's population of about 320,000 was served by a force consisting of 1 night watch, 100 city marshals, 31 constables, and 51 municipal police officers.[1] On May 7, 1844, the New York State passed the Municipal Police Act, a law which authorized creation of a police force and abolished the night watch system.[1][2] At the request of the New York City Common Council, Peter Cooperdrew up a proposal to create a police force of 1,200 officers. John Watts de Peyster was an early advocate of implementing military style discipline and organization to the force.[3]

However, because of a lengthy dispute between the Common Council and the Mayor of New York City regarding who would appoint the officers, the law was not put into effect until the following year. Under Mayor William Havemeyer, the city finally repealed their watch system and adopted the Municipal Police Act as an ordinance on May 23, 1845,[4] creating the New York Police Department in fact rather than merely in legislative theory.

For the purposes of policing, the city was divided into three districts, with courts, magistrates, and clerks, and station houses.[1][5] The NYPD was closely modeled after the Metropolitan Police Service in London, England which used a military-like organizational structure, with rank and order. A navy blue uniform was introduced after long debate in 1853.[6]

In 1857, Republican Party reformers in the New York State capital of Albany created a new Metropolitan police force and abolished the Municipal police,[7] as part of their effort to rein in the Democratic Party-controlled New York City government. The Metropolitan Police Bill consolidated the police in New York, Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Westchester County (which then included The Bronx), under a Governor of New York-appointed board of commissioners.[8]

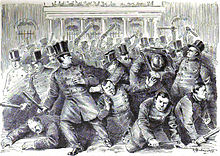

Unwilling to be abolished, Mayor Fernando Wood and the Municipals resisted for several months, during which time the city effectively had two police forces, the State-controlled Metropolitans, and the Municipals. The Metropolitans included 300 policemen and 7 captains who left the Municipal police but was primarily made up of raw recruits with little or no training. The Municipals were controlled directly by Wood and including 800 policemen and 15 captains who stayed. The division between the forces was ethnically determined, with immigrants largely staying with the Municipals, and those of Anglo-Dutch heritage going to the Metropolitans.[7]

Unfortunately, the untested Metropolitans failed to prevent rioting in the city the next day, Independence Day (July 4), and had to be rescued by the Bowery Boys, a nativist gang, when the Irish-immigrant gang the Dead Rabbits attacked the "Mets". Barricades were erected and the battle went on for hours, the worst rioting in the city since 1849. The next Sunday, peace was maintained by the State Militia, but a week later, on July 12, German-immigrants in Little Germany rioted when the Metropolitans attempted to enforce the new reform liquor laws and close down saloons. A blacksmith was killed in the skirmish, and the next day, ten thousand marched up Broadway with a banner proclaiming Opfer der Metropolitan-Polizei ("Victim of the Metropolitan Police").[7]

Throughout the years, the NYPD has been involved with a number of riots in New York City. In July 1863, the New York State Militias were aiding Union Army troops in Pennsylvania, when the 1863 New York Draft Riots broke out. Their absence left it to the police — who were then outnumbered — to quell the riots.[9] The Tompkins Square Riot occurred on January 13, 1874 when police crushed a demonstration involving thousands of unemployed in Tompkins Square Park.[10]

Newspapers, including The New York Times, covered numerous cases of police brutality during the latter part of the 19th century. Cases often involved officers using clubs to beat suspects and persons who were drunk or rowdy, posed a challenge to officers' authority, or refused to move along down the street. Most cases of police brutality occurred in poor immigrant neighborhoods, including Five Points, the Lower East Side, and Tenderloin.[11]

Beginning in the 1870s, politics and corruption of Tammany Hall, a political machine supported by Irish immigrants infiltrated the NYPD, which was used as political tool, with positions awarded by politicians to loyalists. Many officers and leaders in the police department took bribes from local businesses, overlooking things like illegal liquor sales. Police also served political purposes such as manning polling places, where they would turn a blind eye to ballot box stuffing and other acts of fraud.[11]

The Lexow Committee was established in 1894 to investigate corruption in the police department.[12] The committee made reform recommendations, including the suggestion that the police department adopt a civil service system. Corruption investigations have been a regular feature of the NYPD, including the Knapp Commission of the 1970s, and the Mollen Commission of the 1990s.[13]

In 1895, Theodore Roosevelt became President of the NYPD Police Commission. Under his leadership, many reforms were instituted in the NYPD.

On 1 January 1898, the city expanded to include Brooklyn. The department absorbed eighteen existing police departments, requiring more modern organization and communication as it now protected 320 square miles and over three million residents.[14]