PROPACTEAM

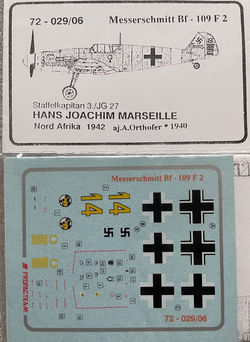

DECALS 1/72-SCALE WW2 GERMAN LUFTWAFFE MESSERSCHMITT Bf109F-2 3./JG 27 HANS-JOACHIM

MARSEILLE NORTH AFRICA DEUTCH AFRIKA KORPS DAK 1942 #72-029/06 (INCLUDES

STENCILS) "STAR OF AFRIKA"

----------------------------

Additional Information from

Internet Encyclopedia

Hans-Joachim Marseille (13 December

1919 – 30 September 1942; was a Luftwaffe

fighter pilot and flying ace during World War II. He is noted for his aerial

battles during the North African Campaign and his Bohemian lifestyle. One of

the most successful fighter pilots, he was nicknamed the "Star of

Africa". Marseille claimed all but seven of his "official" 158

victories against the British Commonwealth's Desert Air Force over North

Africa, flying the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter for his entire combat career.

No other pilot claimed as many Western Allied aircraft as Marseille.

Marseille, of French Huguenot

ancestry, joined the Luftwaffe

in 1938. At the age of 20 he graduated from one of the Luftwaffe's fighter pilot schools just in time to participate in

the Battle of Britain, without notable success. A charming person, he had such

a busy night life that sometimes he was too tired to be allowed to fly the next

morning. As a result, he was transferred to another unit, which relocated to

North Africa in April 1941.

Under the guidance of his new

commander, who recognised the latent potential in the young officer, Marseille

quickly developed his abilities as a fighter pilot. He reached the zenith of

his fighter pilot career on 1 September 1942, when during the course of three

combat sorties he claimed 17 enemy fighters shot down, earning him the Ritterkreuz mit Eichenlaub, Schwertern und

Brillanten (Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds). Only

29 days later, Marseille was killed in a flying accident, when he was

forced to abandon his fighter due to engine failure. After he exited the

smoke-filled cockpit, Marseille's chest struck the vertical stabiliser of his

aircraft. The blow either killed him instantly or incapacitated him so that he

was unable to open his parachute.

He joined Luftwaffe on 7 November 1938, as a Fahnenjunker (officer candidate) and received his military basic

training in Quedlinburg in the Harz region. On 1 March 1939 Marseille was

transferred to the Luftkriegsschule

4 (LKS 4—air war school) near Fürstenfeldbruck. Among his classmates was Werner

Schröer. Schröer reports that Marseille was often in breach of military

discipline. Consequently Marseille was ordered to stay on base while his class

mates were on weekend leave. Quite frequently Marseille ignored this and left

Schröer a note: "Went out! Please take my chores." On one occasion,

while performing a slow circuit, Marseille broke away and performed an

imaginary weaving dogfight. He was reprimanded by his commanding officer, Hauptmann Mueller-Rohrmoser, and

taken off flying duties and his promotion to Gefreiter postponed. Soon after, during a cross-country flight,

he landed on a quiet stretch of Autobahn

(between Magdeburg and Braunschweig) and ran behind a tree to relieve himself. Some

farmers came to enquire if he needed assistance, but by the time they arrived

Marseille was on his way, and they were blown back by his slipstream.

Infuriated, the farmers reported the matter and Marseille was again suspended

from flying. Those he graduated with had been made full officers by early 1940,

while Marseille's indiscipline left him with the rank of Oberfähnrich at the end of 1941.

Marseille completed his training at Jagdfliegerschule 5 (5th fighter

pilot school) in Wien-Schwechat to which he was posted on 1 November 1939. Jagdfliegerschule 5 at the time was

under the command of the World War I flying ace and recipient of the Pour le

Mérite Eduard Ritter von Schleich. One of his teachers at the Jagdfliegerschule 5 was the

Austro-Hungarian World War I ace Julius Arigi. Marseille graduated from Jagdfliegerschule 5 with an

outstanding evaluation on 18 July 1940 and was assigned to Ergänzungsjagdgruppe Merseburg.

Marseille's unit was assigned to air defence duty over the Leuna plant from the

outbreak of war until the fall of France.

On 10 August 1940 he was assigned to

I. Jagd/Lehrgeschwader 2, based

in Calais-Marck, to begin operations over Britain and again received an

outstanding evaluation this time by his Hauptmann

and Gruppenkommandeur, Herbert

Ihlefeld.

In his first dogfight over England

on 24 August 1940, Marseille was involved in a four-minute battle with a

skilled opponent. He defeated his opponent by pulling up into a tight

chandelle, to gain an altitude advantage before diving and firing. The British

fighter was struck in the engine, pitching over and diving into the English

Channel; this was Marseille's first victory. Marseille was then engaged from

above by more enemy fighters. By pushing his aircraft into a steep dive then

pulling up metres above the water, Marseille escaped from the machine gun fire

of his opponents: "skipping away over the waves, I made a clean break. No

one followed me and I returned to Leeuwarden [sic—Marseille was based near Calais,

not Leeuwarden]."

On his second sortie, he scored

another victory, and by the 15 September 1940, had claimed his fourth victory.

Marseille became an ace on 18 September after claiming a fifth enemy aircraft.

While returning from a bomber-escort mission on 23 September 1940 flying Werk Nummer (W.Nr) 5094, his engine

failed 10 miles off Cap Gris Nez after combat damage sustained over Dover. He

tried to radio his position but was forced to bail out over the sea. He paddled

around in the water for three hours before being rescued by a Heinkel He 59

float plane based at Schellingwoude. Severely worn out and suffering from

exposure, he was sent to a field hospital. I.(Jagd) claimed three aerial victories for the loss of four Bf

109s that day.

According to one source, Marseille's

victor was a well-known ace. Werk

Nummer (W.Nr) 5094 was destroyed in this engagement by Robert Stanford

Tuck, who had pursued a Bf 109 to that location and whose pilot was rescued by

a He 59 naval aircraft. Marseille is the only German airman known to have been

rescued by a He 59 on that day and in that location. Tuck's official claim was

for a Bf 109 destroyed off Griz Nez at 09:45—the only pilot to submit a claim

in that location. Marseille was in serious trouble when arriving back at the airfield.

He had abandoned his leader Staffelkapitän

Adolf Buhl, who was shot down and killed. He received a stern rebuke and final

warning from Herbert Ihlefeld, during which he tore up his flight evaluations

with a visibly upset Marseille looking on. Other pilots were voicing their

dissent concerning Marseille. Because of his alienation of other pilots, his

arrogance and unapologetic nature, Ihlefeld would eventually dismiss Marseille

from LG 2. As punishment for

"insubordination"—rumoured to be his penchant for American jazz

music, womanising and an overt "playboy" lifestyle—and inability to

fly as a wingman, Steinhoff transferred Marseille to Jagdgeschwader 27 on 24 December 1940.

Marseille's unit briefly saw action

during the invasion of Yugoslavia, deployed to Zagreb on 10 April 1941, before

transferring to Africa. On 20 April on his flight from Tripoli to his front

airstrip Marseille's Bf 109 developed engine trouble and he had to make a

forced landing in the desert short of his destination. His squadron departed

the scene after they had ensured that he had got down safely. Marseille

continued his journey, first hitchhiking on an Italian truck, then, finding

this too slow; he tried his luck at an airstrip in vain. Finally he made his

way to the general in charge of a supply depot on the main route to the front,

and convinced him that he should be available for operations next day.

Marseille's character appealed to the general and he put at his disposal his

own Opel Admiral, complete with chauffeur. "You can pay me back by getting

fifty victories, Marseille!" were his parting words. Nevertheless he

caught up with his squadron and arrived on 21 April.

He scored two more victories on 23

and 28 April, his first in the North African Campaign. However, on 23 April,

Marseille himself was shot down during his third sortie of that day by Sous-Lieutenant James Denis, a Free

French pilot with No. 73 Squadron RAF (8.5 victories), flying a Hawker

Hurricane. Marseille's Bf 109 received almost 30 hits in the cockpit area, and

three or four shattered the canopy. As Marseille was leaning forward the rounds

missed him by inches. Marseille managed to crash-land his fighter. Just a month

later, records show that James Denis shot down Marseille again on 21 May 1941.

Marseille engaged Denis, but overshot his target. A turning dogfight ensued, in

which Denis once again bested Marseille.[34]

Neumann (a Geschwaderkommodore as of 10 June 1942) encouraged Marseille to

self-train to improve his abilities. By this time, he had crashed or damaged

another four Bf 109E aircraft, including a

tropicalised aircraft he was ferrying on 23 April 1941. Marseille's kill rate

was low, and he went from June to August without a victory. He was further

frustrated after damage forced him to land on two occasions: once on 14 June

1941 and again after he was hit by ground fire over Tobruk and was forced to

land blind.

His tactic of diving into enemy

formations often found him under fire from all directions, resulting in his

aircraft being damaged beyond repair; consequently, Eduard Neumann was losing

his patience. Marseille persisted, and created a unique self-training programme

for himself, both physical and tactical, which resulted not just in outstanding

situational awareness, marksmanship and confident control of the aircraft, but

also in a unique attack tactic that preferred a high angle deflection shooting

attack and shooting at the target's front from the side, instead of the common

method of chasing an aircraft and shooting at it directly from behind.

Marseille often practiced these tactics on the way back from missions with his

comrades. Marseille became known as a master of deflection shooting.

Marseille always strove to improve

his abilities. He worked to strengthen his legs and abdominal muscles, to help

him tolerate the extreme g forces of air combat. Marseille also drank an

abnormal amount of milk and shunned sunglasses, to improve his eyesight.

To counter German fighter attacks,

the Allied pilots flew "Lufbery circles" (in which each aircraft's

tail was covered by the friendly aircraft behind). The tactic was effective and

dangerous as a pilot attacking this formation could find himself constantly in

the sights of enemy pilots. Marseille often dived at high speed into the middle

of these enemy defensive formations from either above or below, executing a

tight turn and firing a two-second deflection shot to destroy an enemy

aircraft. The successes Marseille had begun to become readily apparent in early

1942. He claimed his 37–40th victories on 8 February 1942 and 41–44th victories

four days later which earned him the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross that same

month for 46 victories.

On 17 June 1942, Marseille claimed

his 100th aerial victory. He was the 11th Luftwaffe pilot to achieve the century mark. Marseille then

returned to Germany for two months leave and the following day was awarded the Ritterkreuz mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern.

On 6 August, he began his journey back to North Africa accompanied by his

fiancée Hanne-Lies Küpper. On 13 August, he met Benito Mussolini in Rome and

was presented with the highest Italian military award for bravery, the Medaglia d'Oro al Valor Militare.

While in Italy Marseille disappeared for some time prompting the German

authorities to compile a missing persons report, submitted by the Gestapo head in Rome, Herbert

Kappler. He was finally located. According to rumours he had run off with an

Italian girl and was eventually persuaded to return to his unit. Unusually,

nothing was ever said about the incident and no repercussions were visited upon

Marseille for this indiscretion.

Leaving his fiancée in Rome,

Marseille returned to combat duties on 23 August. 1 September 1942 was

Marseille's most successful day, destroying 17 enemy aircraft (nos. 105–121),

and September would see him claim 54 victories, his most productive month. The

17 enemy aircraft shot down included eight in 10 minutes, as a result of this

feat he was presented with a type 82 Volkswagen Kübelwagen by an Italian Regia

Aeronautica squadron, on which his Italian comrades had painted

"Otto" (Italian languae: Otto

= eight). This was the most aircraft from Western Allied air forces shot down

by a single pilot in one day. Only one pilot, Emil "Bully" Lang on 4

November 1943, would better this score, against the Soviet Air Force on the

Eastern Front. On 3 September 1942 Marseille claimed six victories (nos.

127–132) but was hit by fire from the British-Canadian ace James Francis

Edwards.

Three days later Edwards likely

killed Günter Steinhausen, a friend of Marseille. The next day, 7 September

1942, another close friend Hans-Arnold Stahlschmidt was posted missing in

action. These personal losses weighed heavily on Marseille's mind along with

his family tragedy. It was noted he barely spoke and became more morose in the

last weeks of his life. The strain of combat also induced consistent

sleepwalking at night and other symptoms that could be construed as

Posttraumatic stress disorder. Marseille never remembered these events.

The two missions of 26 September

1942 had been flown in Bf 109G-2/trop, in one of which Marseille had shot down

seven enemy aircraft. The first six of these machines were to replace the Gruppe's Bf 109Fs. All had been

allocated to Marseille's 3 Staffel.

Marseille had previously ignored orders to use these new aircraft because of

its high engine failure rate, but on the orders of Generalfeldmarschall Albert

Kesselring, Marseille reluctantly obeyed. One of these machines, WK-Nr. 14256

(Engine: Daimler-Benz DB 605 A-1, W.Nr. 77 411), was to be the final aircraft

Marseille flew.

Over the next three days Marseille's

Staffel was rested and taken

off flying duties. On 28 September Marseille received a telephone call from Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel

asking to return with him to Berlin. Hitler was to make a speech at the Berlin

Sportpalast on 30 September and Rommel and Marseille were to attend. Marseille

rejected this offer, citing that he was needed at the front and had already

taken three months vacation that year. Marseille also revealed he wanted to

take leave at Christmas, to marry his fiancée Hanne-Lies Küpper.

On 30 September 1942, Hauptmann Marseille was leading his Staffel on a Stuka escort mission, covering the withdrawal of the group and

relieving the outward escort, III./Jagdgeschwader

53 (JG 53), which had been deployed to support JG 27 in Africa.

Marseille's flight was vectored onto enemy aircraft in the vicinity but the

enemy withdrew and did not take up combat. Marseille vectored the heading and

height of the formation to Neumann who directed III./JG 27 to engage. Marseille

heard 8./JG 27 leader Werner Schröer claim a Spitfire over the radio at 10:30.

While returning to base, his new Messerschmitt Bf 109G-2/trop's cockpit began

to fill with smoke; blinded and half asphyxiated, he was guided back to German

lines by his wingmen, Jost Schlang and Lt Rainer Pöttgen. Upon reaching

friendly lines, "Yellow 14" had lost power and was drifting lower and

lower. Pöttgen called out after about 10 minutes that they had reached the

White Mosque of Sidi Abdel Rahman, and were thus within friendly lines. At this

point, Marseille deemed his aircraft no longer flyable and decided to bail out,

his last words to his comrades being "I've got to get out now, I can't

stand it any longer".

His Staffel, which had been flying a tight formation around him,

peeled away to give him the necessary room to manoeuvre. Marseille rolled his

aircraft onto its back, the standard procedure for bail out, but due to the

smoke and slight disorientation, he failed to notice that the aircraft had

entered a steep dive (at an angle of 70–80 degrees) and was now travelling at a

considerably faster speed (about 400 mph). He worked his way out of the

cockpit and into the rushing air only to be carried backwards by the

slipstream, the left side of his chest striking the vertical stabiliser of his

fighter, either killing him instantly or rendering him unconscious to the point

that he could not deploy his parachute. He fell almost vertically, hitting the

desert floor 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) south of Sidi Abdel Rahman. As it

transpired, a gaping 40 cm (16 in) hole had been made in his

parachute and the canopy had spilled out, but after recovering the body, the

parachute release handle was still on "safe," revealing Marseille had

not even attempted to open it. Whilst checking the body, Oberarzt Dr Bick, the regimental

doctor for the 115th Panzergrenadier-Regiment,

noted Marseille's wristwatch had stopped at exactly 11:42 am. Dr. Bick had

been the first to reach the crash site, having been stationed just to the rear

of the forward mine defences, he had also witnessed Marseille's fatal fall.

------------------------------

Development of the new Bf 109F

airframe had begun in 1939. After February 1940 an improved engine, the

Daimler-Benz DB 601E, was developed for use with the Bf 109. The engineers at

the Messerschmitt facilities took two Bf 109 E-1 airframes and installed this

new powerplant. The first two prototypes, V21 (Werknummer (Works number) or

W.Nr 5602) and V22 (W.Nr 1800) kept the trapeziform wing shape from the E-1,

but the span was reduced by 61 cm (2 ft) by "clipping" the tips.

Otherwise the wings incorporated the cooling system modifications described

below. V22 also became the testbed for the pre-production DB 601E. The smaller

wings had a detrimental effect on the handling so V23, Stammkennzeichen

(factory Code) CE+BP, W.Nr 5603, was fitted with new, semi-elliptical wingtips,

becoming the standard wing planform for all future Bf 109 combat versions. The

fourth prototype, V24 VK+AB, W.Nr 5604, flew with the clipped wings but

featured a modified, "elbow"-shaped supercharger air-intake which was

eventually adopted for production, and a deeper oil cooler bath beneath the

cowling. On all of these prototypes the fuselage was cleaned up and the engine

cowling modified to improve aerodynamics.

Compared to the earlier Bf 109

E, the Bf 109 F was much improved aerodynamically. The engine cowling was

redesigned to be smoother and more rounded. The enlarged propeller spinner,

adapted from that of the new Messerschmitt Me 210, now blended smoothly into

the new engine cowling. Underneath the cowling was a revised, more streamlined

oil cooler radiator and fairing. A new ejector exhaust arrangement was

incorporated, and on later aircraft a metal shield was fitted over the left

hand banks to deflect exhaust fumes away from the supercharger air-intake. The

supercharger air-intake was, from the F-1 -series onwards, a rounded,

"elbow"-shaped design that protruded further out into the airstream.

A new three-blade, light-alloy VDM propeller unit with a reduced diameter of 3

m (9 ft 8.5 in) was used. Propeller pitch was changed electrically, and was

regulated by a constant-speed unit, though a manual override was still

provided. Thanks to the improved aerodynamics, more fuel-efficient engines and

the introduction of light-alloy versions of the standard Luftwaffe 300 litre

drop tank, the Bf 109 F offered a much increased maximum range of 1,700 km

(1,060 mi) compared to the Bf 109 E's maximum range figure of only 660 km (410

miles) on internal fuel, and with the E-7's provision for the 300 litre drop

tank, a Bf 109E so equipped possessed double the range, to 1,325 km (820 mi).

The canopy stayed essentially

the same as that of the E-4 although the handbook for the 'F' stipulated that

the forward, lower triangular panel to starboard was to be replaced by a metal

panel with a port for firing signal flares. Many F-1s and F-2s kept this

section glazed. A two-piece, all-metal armour plate head shield was added, as

on the E-4, to the hinged portion of the canopy, although some lacked the

curved top section. A bullet-resistant windscreen could be fitted as an option.

The fuel tank was self-sealing, and around 1942 Bf 109Fs were retrofitted with

additional armour made from layered light-alloy plate just aft of the pilot and

fuel tank. The fuselage aft of the canopy remained essentially unchanged in its

externals.

The tail section of the aircraft

was redesigned as well. The rudder was slightly reduced in area and the

symmetrical fin section changed to an airfoil shape, producing a sideways lift

force that swung the tail slightly to the left. This helped increase the

effectiveness of the rudder, and reduced the need for application of right

rudder on takeoff to counteract torque effects from the engine and propeller.

The conspicuous bracing struts were removed from the horizontal tailplanes

which were relocated to slightly below and forward of their original positions.

A semi-retractable tailwheel was fitted and the main undercarriage legs were

raked forward by six degrees to improve the ground handling. An unexpected

structural flaw of the wing and tail section was revealed when the first F-1s

were rushed into service; some aircraft crashed or nearly crashed, with either

the wing surface wrinkling or fracturing, or by the tail structure failing. In

one such accident, the commander of JG 2 "Richthofen", Wilhelm

Balthasar lost his life when he was attacked by a Spitfire during a test

flight. While making an evasive manoeuvre, the wings broke away and Balthasar

was killed when his aircraft hit the ground. Slightly thicker wing skins and

reinforced spars dealt with the wing problems. Tests were also carried out to

find out why the tails had failed, and it was found that at certain engine

settings a high-frequency oscillation in the tailplane spar was overlapped by

harmonic vibrations from the engine; the combined effect being enough to cause

structural failure at the rear fuselage/fin attachment point. Initially two

external stiffening plates were screwed onto the outer fuselage on each side,

and later the entire structure was reinforced.

The entire wing was redesigned,

the most obvious change being the new quasi-elliptical wingtips, and the slight

reduction of the aerodynamic area to 16.05 m² (172.76 ft²). Other features of

the redesigned wings included new leading edge slats, which were slightly

shorter but had a slightly increased chord; and new rounded, removable wingtips

which changed the planview of the wings and increased the span slightly over

that of the E-series. Frise-type ailerons replaced the plain ailerons of the

previous models. The 2R1 profile was used with a thickness-to-chord ratio of

14.2% at the root reducing to 11.35% at the last rib. As before, dihedral was

6.53°.

The wing radiators were

shallower and set farther back on the wing. A new cooling system was introduced

which was automatically regulated by a thermostat with interconnected variable

position inlet and outlet flaps that would balance the lowest drag possible

with the most efficient cooling. A new radiator, shallower but wider than that

fitted to the E was developed. A boundary layer duct allowed continual airflow

to pass through the airfoil above the radiator ducting and exit from the

trailing edge of the upper split flap. The lower split flap was mechanically

linked to the central "main" flap, while the upper split flap and

forward bath lip position were regulated via a thermostatic valve which

automatically positioned the flaps for maximum cooling effectiveness. In 1941

"cutoff" valves were introduced which allowed the pilot to shut down

either wing radiator in the event of one being damaged; this allowed the

remaining coolant to be preserved and the damaged aircraft returned to base.

However, these valves were delivered to frontline units as kits, the number of

which, for unknown reasons, was limited.

The armament of the Bf 109 F was

revised and now consisted of the two synchronized 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17s with

500 rpg above the engine plus a Motorkanone cannon firing through the propeller

hub. The pilot's opinion on the new armament was mixed: Oberst Adolf Galland

criticised the light armament as inadequate for the average pilot, while Major

Walter Oesau preferred to fly a Bf 109 E, and Oberst Werner Mölders saw the

single centreline Motorkanone gun as an improvement.

With the early tail unit

problems out of the way, pilots generally agreed that the F series was the

best-handling of all the Bf 109 series. Mölders flew one of the first

operational Bf 109 F-1s over England from early October 1940; he may well have

been credited with shooting down eight Hurricanes and four Spitfires while

flying W.No 5628, Stammkennzeichen SG+GW between 11 and 29 October 1940.