A charming and original two-page extract from the famous Gazette Du Bon Ton magazine (see below) published in September 1922.

The title of this article is "La Mort du Chapeau Haute-Forme" or Death of the Top Hat, embellished with illustrations by "Carlègle" (Charles Emile Egli) - see below - and verse by "Franc-Nohain" - see below

Many of the famous Art-Deco artists of the day contributed illustrations to the magazine which were printed by using the hand-applied, color pochoir technique .

Good condition. Two pages, four sides with central fold as published. Binding holes to the fold. Page size 10 x 7.5 inches

See more of these in Seller's Other Items which can be combined for mailing at no extra cost

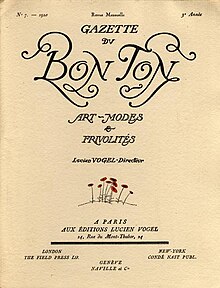

Gazette du Bon Ton

The Gazette du Bon Ton was a small but influential fashion magazine published in France from 1912 to 1925.[1][2] Founded by Lucien Vogel, the short-lived publication reflected the latest developments in fashion, lifestyle and beauty during a period of revolutionary change in art and society.[1] Distributed by Condé Nast, the magazine was issued as the Gazette du Bon Genre in the USA.[3] Both titles roughly translate as "Journal of Good Taste"[4] or "Journal of Good Style."[3]

The magazine strove to present an elitist image to distinguish itself from larger, mainstream competitors like Vogue and Harper's Bazaar in America and Femina, Les Modes and L'Art et la Mode in France.[5] It was available only to subscribers and was priced at a steep 100 francs per year, or $425.61 in today's money.[6]The magazine, published on fine paper,[2] signed exclusive contracts with seven of Paris' top couture houses – Cheruit, Doeuillet, Doucet, Paquin, Poiret, Redfern, and Worth – to reproduce in luscious pochoir the designers' latest creations.[6] After World War I, a select group of other design firms were added to the magazine's repertoire, including the houses of Beer, Lanvin, Patou and Martial & Armand. However, the editors' choice of designers was arbitrary, and a number of the era's most prominent couturiers never contributed to the pages of the Gazette du Bon Ton, among them Chanel and Lucile. The magazine's title was derived from the French concept of bon ton, or timeless good taste and refinement.[4]

The Gazette du Bon Ton aimed to establish fashion as an art alongside painting, sculpture and drawing. According to the magazine's first editorial: "The clothing of a woman is a pleasure for the eye that cannot be judged inferior to the other arts."[4]

To elevate the Gazette's literary status, the publication featured essays on fashion by established writers from other fields, including novelist Marcel Astruc, playwright Henri de Regnier, decorator Claude Roger-Marx, and art historian Jean-Louis Vaudoyer.[6] Their contributions ranged in tone from irreverent to ironic and mocking.[6]

The centerpiece of the Gazette was its fashion illustrations.[7] Each issue featured ten full-page fashion plates (seven depicting couture designs and three inspired by couture but designed solely by the illustrators)[7] printed with the color pochoir technique.

It employed many of the most famous Art Deco artists and illustrators of the day, including Etienne Drian, Georges Barbier, Erté (Romain de Tirtoff), Paul Iribe, Pierre Brissaud, André Edouard Marty, Thayaht (Ernesto Michahelles), Georges Lepape, Edouard Garcia Benito, Soeurs David (David Sisters), Pierre Mourgue, Robert Bonfils, Bernard Boutet de Monvel, Maurice Leroy, and Zyg Brunner. These artists, rather than simply drawing models in outfits, depicted them in various dramatic and narrative situations.

Franc-Nohain

Maurice Étienne Legrand, who published under the pseudonym Franc-Nohain (French pronunciation: [fʁɑ̃.nɔ.ɛ̃]; 25 October 1872 – 18 October 1934), was a French librettist and poet. He is best known for his libretti for Maurice Ravel's opera L'heure espagnoleand for numerous operettas by Claude Terrasse.

Life[edit]

Maurice Étienne Legrand was born in 1872 in Corbigny; his father was an overseer-agent. He attended the Lycée Janson de Sailly. In the late 1880s he contributed poems to the literary magazine Potache-Revue (potache being slang for 'schoolkid'), along with André Gide, Léon Blum, Pierre Louÿs, Maurice Quillot and others.[1] Later, he published in the journal Le Chat noir. He also founded Le Canard sauvage and became the editor of L'Écho de Paris. He also became a lawyer and deputy prefect.

His literary pseudonym Franc-Nohain was derived from the Nohain River, where he had spent many happy hours as a child.

With Alfred Jarry and Claude Terrasse he co-founded the Théatre des Pantins, which in 1898 was the site of marionette performances of Jarry's Ubu Roi.[2]

He is best remembered now as the librettist for some operettas by Terrasse, and for the opera L'heure espagnole by Maurice Ravel, adapted from his own comedy.

He had two sons: the actor Claude Dauphin, and the songwriter and television producer/director Jean Nohain (aka Jaboune).[3]

He died in Paris in October 1934, aged 61.

Works[edit]

Libretti[edit]

- L'Heure espagnole, 1904

- Un jardin sur l'Oronte, 1922, adapted from a novel of the same name by Maurice Barrès

- Le Chapeau chinois, 1931

Charles Émile Egli

Contents

Early years[edit]

Charles Émile Egli was born in Aigle, Switzerland on 30 March 1877.[citation needed] He was educated in Aigle and then at the college of Vevey. When he was eighteen he attended engraving classes of Alfred Martin at the school of industrial arts in Geneva. Four year later he moved to Paris, where he stayed the rest of his life. Egli studied at the École des Beaux-Arts.[1]

Charles Émile Egli was born in Aigle, Switzerland on 30 March 1877.[citation needed] He was educated in Aigle and then at the college of Vevey. When he was eighteen he attended engraving classes of Alfred Martin at the school of industrial arts in Geneva. Four year later he moved to Paris, where he stayed the rest of his life. Egli studied at the École des Beaux-Arts.[1]

Career[edit]

Egli adopted the pseudonym of Carlègle. He soon became known in satirical journals like Le Rire, Le Sourire, La Vie Parisienne, L'Assiette au Beurre, Fantasio, La Gazette do Bon Ton, Les Humoristes and Qui lit rit. Egli excelled in wood engraving. His illustrations for Daphnis et Chloé exhibited in the autumn Salon of 1913 launched his career. From then until his death in 1937 he illustrated books by classical and contemporary authors such as Virgil, Paul Valéry, Blaise Pascal, Paul Verlaine, Anatole Franceand Charles Maurras. He was naturalized in 1927.[1]

Charles Émile Egli died in Paris on 11 January 1937. He was the subject of a book by Hugues Delorme published in 1939.[2]

Egli adopted the pseudonym of Carlègle. He soon became known in satirical journals like Le Rire, Le Sourire, La Vie Parisienne, L'Assiette au Beurre, Fantasio, La Gazette do Bon Ton, Les Humoristes and Qui lit rit. Egli excelled in wood engraving. His illustrations for Daphnis et Chloé exhibited in the autumn Salon of 1913 launched his career. From then until his death in 1937 he illustrated books by classical and contemporary authors such as Virgil, Paul Valéry, Blaise Pascal, Paul Verlaine, Anatole Franceand Charles Maurras. He was naturalized in 1927.[1]

Charles Émile Egli died in Paris on 11 January 1937. He was the subject of a book by Hugues Delorme published in 1939.[2]

Selected works[edit]

Books that Egli illustrated include:

- Carnet d'un Combattant by Paul Tuffrau, Payot - appeared in 1917, under the pseudonym of lieutenant E.R., with 64 pen drawings

- Frontispice in the review L'Encrier, founded by Roger Dévigne in May 1919

- La Petite Fille aux Papillotes, original wood engraving in the review L'Encrier (15 October-15 November 1919)

- Daphnis et Chloé by Longus, chez Pichon in 1919

- Le Train de 8h47 by Georges Courteline, Paris, Société littéraires de France

- Les Linottes by Georges Courteline, Paris, Éditions littéraires de France

- Les Aventures du Roi Pausole by Pierre Louys, first published by Fayard (« Modern Bibliothèque ») in 1908, then with different illustrations by Briffaut in 1924

- Mon Amie Nane by Paul-Jean Toulet, 18 original wood engravings, Paris, Léon Pichon, 1925

- Les Contrerimes by Paul-Jean Toulet, 6 original wood engravings, Brussels, Editions Un Coup de Dés, 1927

- Lysistrata d'Aristophane, Paris, Éditions Briffaut, 1928

- Maxime de Duvernois, Babou, 1929

- Le Sopha de Crébillon, Mornay, 1933

- Nudité de Colette, La Mappemonde, 1943 (posthumous)

- L'Arlequin aux Jacinthes by Maurice Venoize, Boivin et Cie, undated

Books that Egli illustrated include:

- Carnet d'un Combattant by Paul Tuffrau, Payot - appeared in 1917, under the pseudonym of lieutenant E.R., with 64 pen drawings

- Frontispice in the review L'Encrier, founded by Roger Dévigne in May 1919

- La Petite Fille aux Papillotes, original wood engraving in the review L'Encrier (15 October-15 November 1919)

- Daphnis et Chloé by Longus, chez Pichon in 1919

- Le Train de 8h47 by Georges Courteline, Paris, Société littéraires de France

- Les Linottes by Georges Courteline, Paris, Éditions littéraires de France

- Les Aventures du Roi Pausole by Pierre Louys, first published by Fayard (« Modern Bibliothèque ») in 1908, then with different illustrations by Briffaut in 1924

- Mon Amie Nane by Paul-Jean Toulet, 18 original wood engravings, Paris, Léon Pichon, 1925

- Les Contrerimes by Paul-Jean Toulet, 6 original wood engravings, Brussels, Editions Un Coup de Dés, 1927

- Lysistrata d'Aristophane, Paris, Éditions Briffaut, 1928

- Maxime de Duvernois, Babou, 1929

- Le Sopha de Crébillon, Mornay, 1933

- Nudité de Colette, La Mappemonde, 1943 (posthumous)

- L'Arlequin aux Jacinthes by Maurice Venoize, Boivin et Cie, undated